1. Introduction

In the last several years, modern power networks have experienced a marked increase in incorporating renewable power sources, such as wind and solar power plants. These renewable energy sources are widely favored for their numerous benefits, such as their low environmental impact and operational costs, making them suitable for sustainable energy generation. However, despite these advantages, integrating renewable energy sources into power grids has its challenges. One of the primary difficulties arises from the inherent volatility of these resources, which complicates the task of accurately forecasting their energy production [

1]. This uncertainty presents significant challenges for the planning and operating of renewable energy-integrated power systems, making it difficult to determine the availability of renewable energy units at any given time.

The variability introduced by renewable energy resources is not the sole source of uncertainty in power systems. Another critical factor contributing to uncertainty is the fluctuating price of electricity [

2]. With the deregulation of the electricity industry and the advent of competitive electricity markets, electricity prices have become increasingly volatile. Predicting these prices has become more complex as they are affected by numerous factors, including uncertainties in production costs, transmission and distribution expenses, market competition dynamics, production capacities, and fluctuations in load demand [

2]. Load demand, while generally more predictable than renewable energy production or electricity prices, also contributes to system variability. Load forecast errors can lead to deviations between actual and predicted load demand, further complicating the management and operation of power systems [

3].

To tackle the various sources of uncertainty, researchers have suggested multiple methodologies, with stochastic programming being one of the most commonly employed approaches [

4]. This technique involves generating multiple scenarios to represent the likely realizations of uncertain variables and then reducing the number of scenarios to make the optimization process computationally manageable. These refined scenarios are subsequently used to estimate the expected value of the objective function, facilitating more effective decision-making under uncertainty.

In the literature, various techniques have been devised to generate and reduce the number of scenarios. For scenario generation, sampling-based methods, like the Monte Carlo method [

4], are frequently employed due to their capability to simulate a diverse range of possibilities. To streamline the optimization process and manage computational demands, scenario reduction techniques, such as forward [

5] and backward reduction algorithms [

5], are applied. Over the past years, developments in artificial intelligence have introduced deep learning as a powerful tool for both scenario generation and reduction. By leveraging deep neural networks, these methods can learn sophisticated trends and distributions in the data, improving the accuracy of scenario analysis. In the domain of scenario generation, generative models have gained prominence. These include sophisticated algorithms like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

6], which excel at creating realistic scenarios by learning the underlying data distribution. Other methods, such as recursive techniques [

7], are also employed for scenario generation, offering complementary approaches that will be discussed in greater depth in subsequent sections.

For scenario reduction, no single method has emerged as universally preferred, as the field continues to explore diverse strategies. Deep learning approaches, like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

8], have proven their magnificent capability in identifying and preserving the most critical scenarios while discarding less relevant ones. These methods employ the ability of deep neural networks to evaluate and prioritize complex datasets, enabling efficient and meaningful scenario reduction.

In this article, we present a thorough review of deep learning methods applied to scenario generation and reduction within the context of power systems. This review offers the following key contributions:

Thorough Review and Categorization of Scenario Generation Methods: We extensively review deep learning approaches employed for scenario generation, addressing limitations in existing studies. For instance, while prior works such as [

9,

10,

11] have explored aspects of scenario generation, their coverage is too general. Some articles, such as [

10,

11], briefly mention GANs and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, but fail to discuss their recent advancements or other newly developed approaches. In contrast, other works, like [

9], focus specifically on GANs, leaving other techniques underexplored.

Comprehensive Analysis of Scenario Reduction Techniques: We deliver an in-depth examination and categorization of scenario reduction methods utilizing deep learning algorithms. Unlike scenario generation, the application of deep learning to scenario reduction has been largely overlooked in the existing review literature, leaving a critical gap that this article aims to address.

The forthcoming sections of this paper provide a detailed examination of the deep learning techniques used for scenario generation and reduction, emphasizing their strengths, limitations, and applications across various domains.

Section 2 focuses on the methodologies employed for scenario generation using deep learning techniques.

Section 3 delves into the deep learning approaches for scenario reduction, highlighting key developments and innovations.

Section 4 outlines the challenges associated with applying deep learning techniques to scenario analysis, offering insights into potential areas for future development and research.

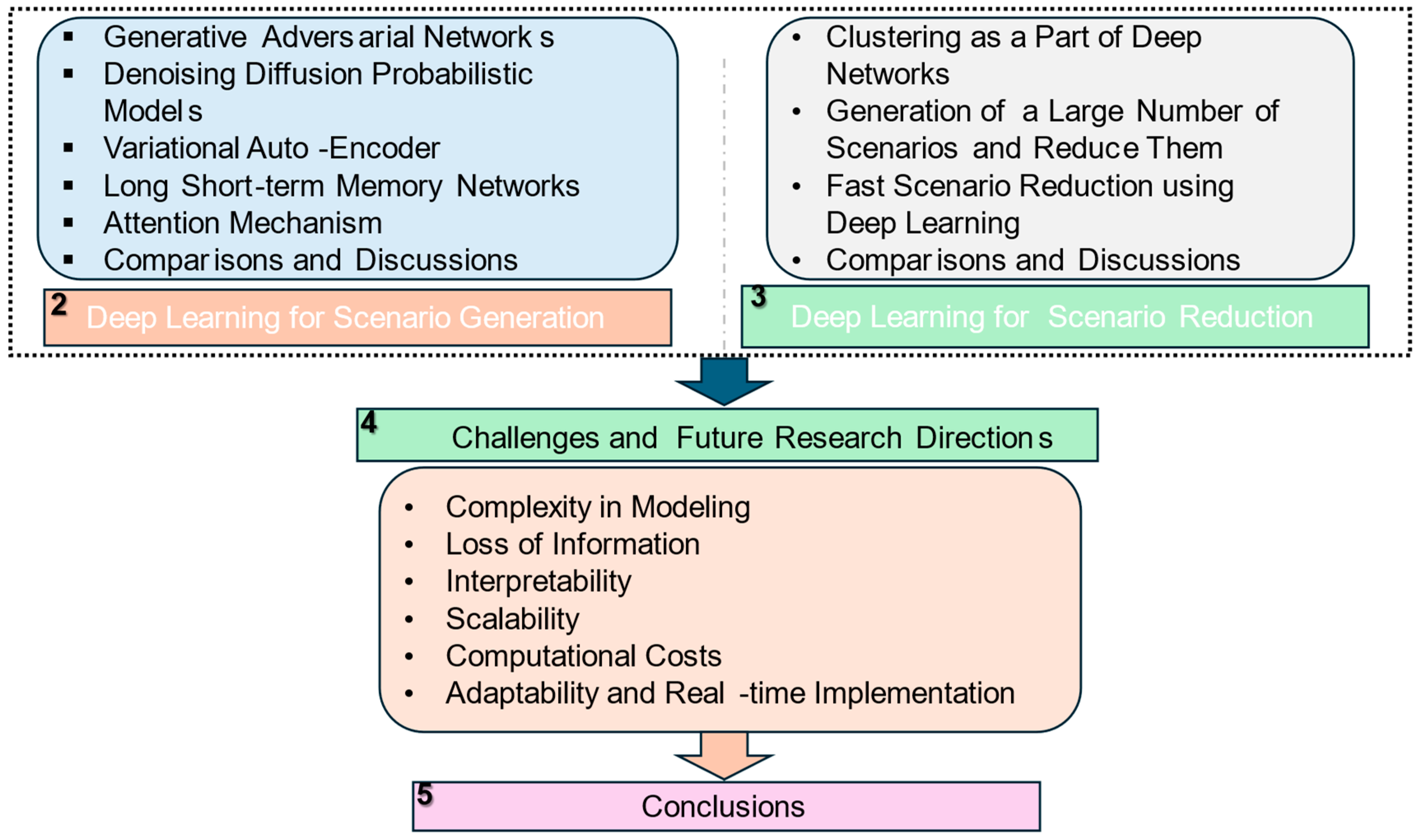

Section 5 provides conclusions. The flow diagram of

Figure 1 illustrates a more detailed organization of the next sections of the paper and outlines the topics covered in each section.

2. Deep Learning for Scenario Generation

Uncertainty modeling in renewable energy-integrated power systems using stochastic uncertainty modeling methods involves two fundamental steps: scenario generation and scenario reduction. In this process, uncertainties in weather conditions, load demand, and market dynamics are addressed by generating a wide range of potential scenarios using scenario-generation techniques. These scenarios are then refined and optimized through scenario reduction methods to identify the most relevant ones. Together, these steps provide a highly accurate representation of how uncertain parameters might unfold in the coming hours, enabling more effective optimization and decision making.

Over the past years, machine learning-based methods, particularly deep learning algorithms, have been introduced as powerful approaches for scenario generation. In contrast to conventional methods that depend on assumptions such as predefined probability distributions for uncertain variables, deep learning methods can model the sophisticated relationships inherent in the data. This capability allows them to generate scenarios that are not only more accurate but also more realistic.

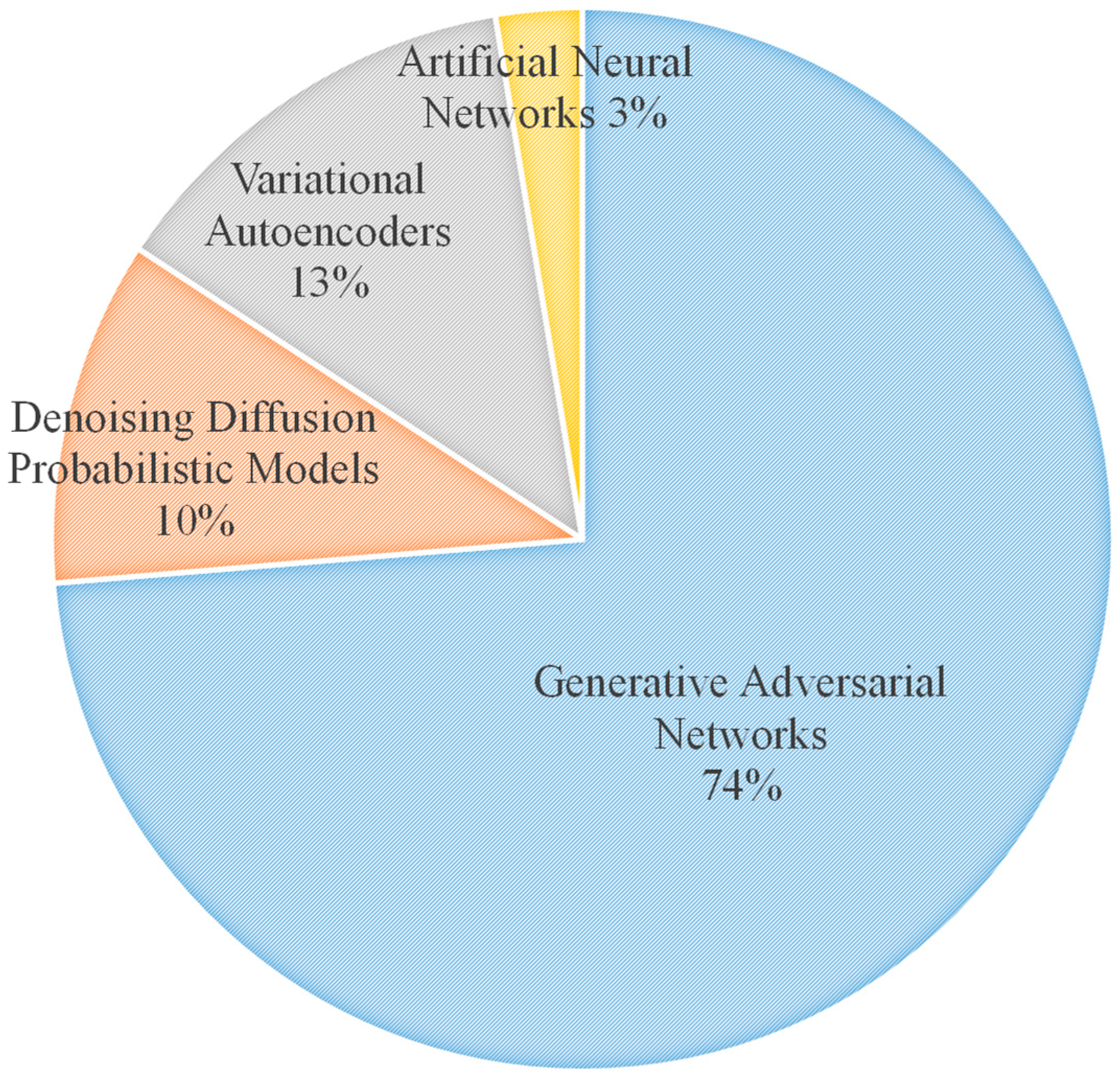

Significant advancements have been achieved in this area with the development of deep neural networks. Introducing models such as Diffusion Models and GANs has notably enhanced performance. By leveraging diverse architectures, such as attention mechanisms or recurrent networks, these methods can deliver robust and effective results across various data types and conditions. As shown in

Figure 1, in the following sections, we will first present GAN method, the most commonly used deep learning approach for scenario generation. Subsequently, we will explore other deep-learning methods employed in this domain.

2.1. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

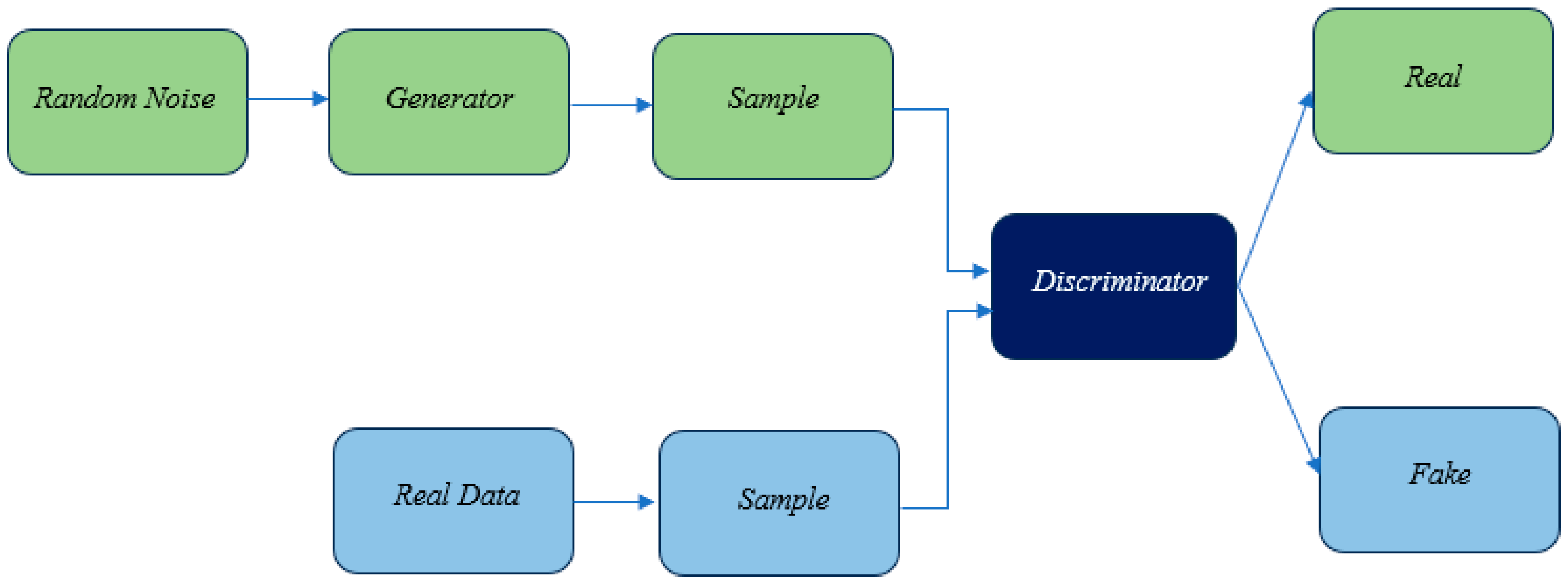

GANs are among the most popular deep learning models for generating data that closely resembles a given dataset. In recent years, GANs have emerged as one of the most effective approaches of generative modeling, offering a powerful framework for creating realistic data. A GAN is composed of two core elements: one is a generator (GE) and another one is a discriminator (DI). These two components engage in a competitive learning process to enhance each other’s performance [

12].

The generator begins by producing random noise, with its ultimate goal being to produce generated data indistinguishable from the real data. Contrarily, the discriminator’s function is to assess the originality of the data, differentiating between genuine real samples and the generator’s produced outputs. At the beginning of training, the discriminator easily recognizes the generator’s outputs as fake since they differ greatly from real data. However, as training progresses, the generator improves, producing data that increasingly are as same as real examples. This makes it more challenging for the discriminator to differentiate between genuine and fake data.

This adversarial interaction lies at the core of the GAN learning process. The generator strives to minimize the ability of discriminator to identify its outputs as fake, While the discriminator focuses on enhancing its ability to correctly identify real data versus generated data. Mathematically, this interaction is represented as a min-max optimization problem, expressed as follows:

where

P(

x) and

P(

z) are probability distribution functions of training data

x and fake data produced by generator

z, respectively. On the other hand,

DI(

x) and

DI(

GE(

z)) refer to the output of discriminator for genuine and generated samples, respectively. A representation of GAN structure is given in

Figure 2.

GANs have been extensively utilized for scenario generation across a wide range of fields. They have been employed to model load demand in [

13], electricity price in [

14], extreme outage prediction in [

15], renewable energy outputs in [

12,

16], and time aggregation in [

17]. Furthermore, researchers have made significant efforts in recent years to improve the basic architecture of GANs in order to overcome various limitations and improve performance.

Notable advancements in GAN technology, as outlined in

Table 1, have been employed to generate scenarios for renewable energies. These advancements have expanded the robustness of GANs, making them a power tool for generating realistic scenarios. By addressing key challenges such as instability, and conditional control, these innovations have greatly enhanced the performance of GANs to model a diverse range of real-world problems effectively.

2.2. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) are an advanced category of generative models that work through a two-stage procedure [

32]. At the first step, referred to as the forward diffusion process, Gaussian noise is incrementally added to a data sample, like an image, over a sequence of time steps. This introduction of noise transforms the initial clean data sample

x0 into a sequence of noisier versions, denoted as

x1,

x2, …,

xT. In the final step,

xT, the data is almost entirely reduced to pure Gaussian noise. This progression from structured data to noise is designed to be predictable, ensuring that the noisy intermediate states can later be reversed.

Each step in this forward process is governed by a Gaussian distribution

q, where the parameter

plays a critical role in controlling the amount of noise added at each time step:

The choice of ensures that the transformation occurs in a smooth and mathematically tractable manner, maintaining the integrity of the process while preparing the model for its primary task: learning the reverse diffusion process.

This forward diffusion establishes the foundation for the second phase, where the model learns to reverse the sequence step by step. By doing so, DDPMs reconstruct the original data from its noisy counterpart, ultimately allowing the creation of new, high-quality data samples in a coherent and structured way. The reverse process is managed by a neural network (

) predicting the variance (

) and mean (

) of the denoising process at each stage:

The model is optimized to reduce the discrepancy between the predicted denoised data and the real data, ensuring precise reversal of the diffusion process. Training typically entails optimizing a variational upper bound on the negative log-likelihood of the data, which is usually reduced to a mean squared error (MSE) loss, comparing the actual and predicted noises. After training, the model can produce new data by starting with random noise and using the learned reverse process iteratively, gradually transforming the noise into a structured output.

Since this method is relatively new, only a few papers have examined its application in scenario generation. Notably, this approach has been used to generate scenarios for PV power generation in [

33], wind power generation in [

34], and both PV and wind power generation in [

35]. Furthermore, in [

36], it has been extended to scenario generation for PV and wind power generation, as well as electrical, heating, and cooling load demands. Despite these promising examples, significant opportunities remain for future research to leverage this method or its modified variants to enhance results and address challenges in scenario generation across various domains.

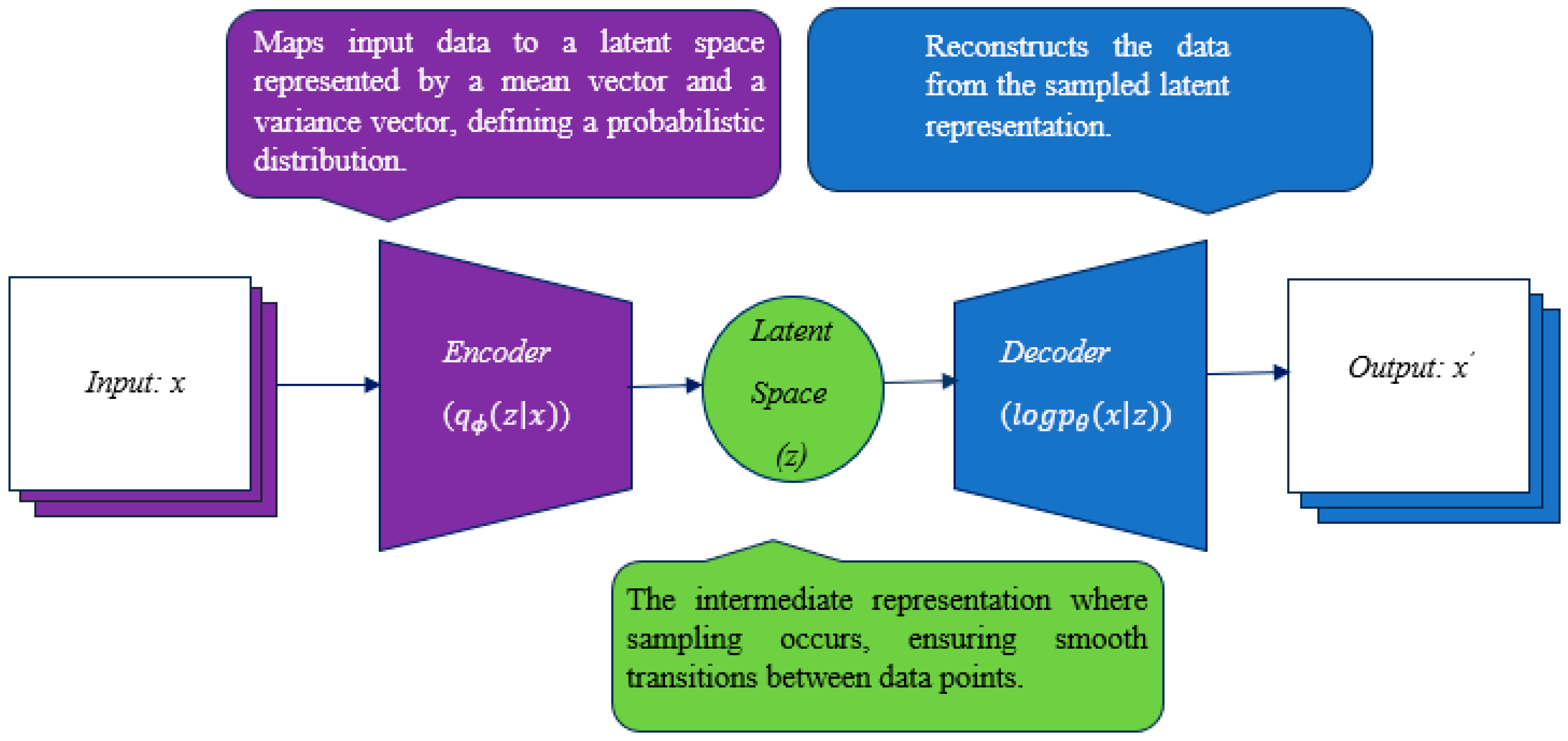

2.3. Variational Auto-Encoder

Variational autoencoders (VAEs) are a class of generative models that integrate deep learning techniques with probabilistic methods to create new data samples similar to an existing dataset [

37]. Unlike standard autoencoders, which compress and reconstruct data deterministically, VAEs use a probabilistic approach in which the data is first mapped into a latent space using an encoder that has a probability distribution function with a mean vector and a variance vector. The output data is then extracted from these sampled latent representations using a decoder. A demonstration of VAE structure is given in

Figure 3.

A two-part loss function is used to train the network as follows:

where

indicates the reconstruction loss. It measures how well the decoder, parameterized by

θ, reconstructs the input

xi, given the latent representation

zi. The term

represents the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the approximate posterior

, which is typically considered to be a simple Gaussian distribution, and the prior

. This term is used to make the probability distribution function of

resemble a Gaussian distribution, ensuring that the generated samples do not deviate significantly from the input data.

The number of studies utilizing VAEs for scenario generation remains relatively limited, primarily due to challenges in generating high-quality and realistic scenarios. In [

38], this network is employed for the scenario generation of load demand due to its lower uncertainty and the absence of a need for a highly robust framework. However, enhanced versions of these approaches have been proposed in recent studies to address VAE’s limitations. In [

39], the authors focus on improving the quality of scenario generation for wind power output using an Importance Weighted Autoencoder (IWAE). The IWAE enhances the standard VAE by using importance weighting, which improves the evidence lower bound (ELBO) estimation and allows the model to better approximate complex data distributions. A hybrid approach combining

Autoencoders (AE) and

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) is presented in [

40,

41] for scenario generation of energy demand and renewable energy, respectively. However, VAE has seen limited standalone use in recent years, largely due to the emergence of GAN networks. Instead, it is primarily utilized in combination with other architectures to enhance network structure or improve overall performance.

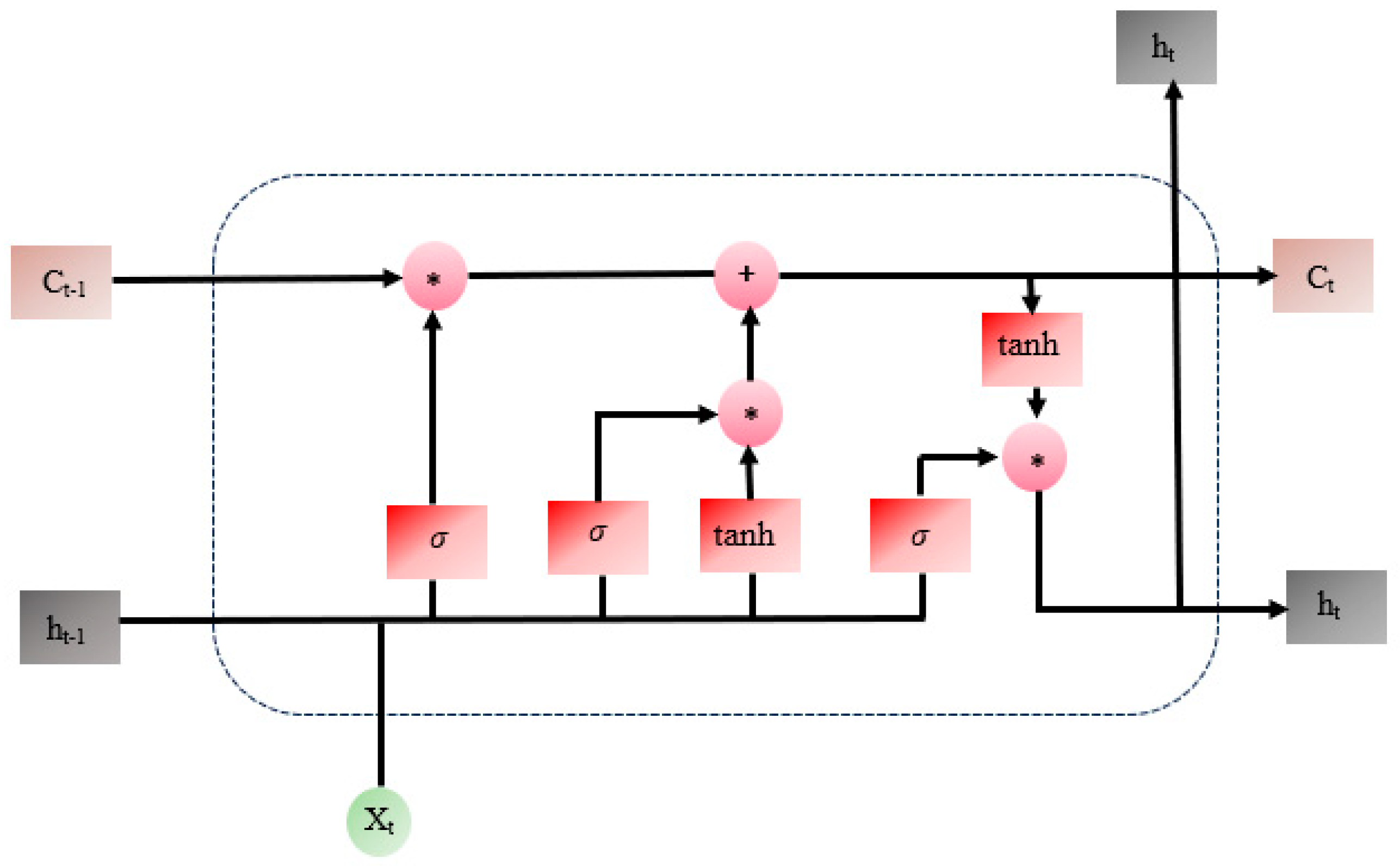

2.4. Long Short-Term Memory Networks

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks represent an enhanced form of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically engineered to adeptly learn and preserve long-term dependencies within sequential data. Unlike conventional RNNs, which falter in grasping extended dependencies because of the vanishing gradient issue during training, LSTMs overcome this limitation through a refined structure. This architecture enables the network to maintain critical information across prolonged sequences while filtering out extraneous details [

42].

An LSTM cell consists of multiple gates and components that control the flow and retention of information. A detailed description of all states and gates within this mechanism is provided in

Table 2 below:

Using the given values, the following two equations are used to define the process of updating the output values of cell state (

) and hidden state (

) at each time step:

These mechanisms enable LSTM networks to dynamically determine which information to retain, discard, or output at each time step, enabling them to adeptly identify and model both short-term patterns and long-term dependencies within sequential data. The structure of an LSTM network is illustrated in

Figure 4. LSTMs are frequently integrated into the architectures of other neural networks to enhance their performance [

17]. This widespread integration is primarily attributed to LSTM’s ability to extract meaningful temporal and spatial features from complex data and reconstruct time-series data by modeling both long- and short-term dependencies. For instance, as shown in [

43,

44,

45], and [

46], LSTMs have been incorporated into the frameworks of sequence GANs, VAEs, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), respectively, to improve their scenario generation capabilities. This hybrid usage highlights the versatility of LSTM networks in strengthening more complex models, enabling the generation of realistic and representative scenarios.

2.5. Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanisms are a class of techniques in machine learning designed to dynamically focus computational resources on the most relevant parts of input data when generating outputs or making predictions. Inspired by how humans selectively concentrate on specific stimuli while ignoring others, attention mechanisms allow models to enhance their interpretability and efficiency by assigning varying levels of importance (weights) to different parts of the input. Three types of attention mechanism are presented as follows [

47]:

Self-Attention (Scaled Dot-Product Attention): This mechanism computes the significance of each element in an input sequence relative to every other element within the same sequence. It excels at capturing long-range dependencies and intricate relationships in sequential or structured data. Widely adopted in Transformer models, self-attention has been a cornerstone in advancing fields like natural language processing and image analysis.

Cross-Attention: This mechanism aligns elements from one input (e.g., a query) with another input (e.g., context), as seen in encoder-decoder architectures where the decoder focuses on specific parts of the encoded sequence during generation.

Multi-Head Attention: This approach divides inputs into multiple attention heads, allowing each to detect and represent unique elements of input relationships before merging them into a richer representation.

Recently, attention mechanisms have been increasingly integrated into GANs to enhance their performance in scenario generation tasks. In [

48], the Informer-Time-Series GAN merges the principles of TimeGANs with self-attention mechanisms, resulting in a hybrid model optimized for time-series data generation. By leveraging attention, the model focuses on critical time steps, effectively capturing long-range dependencies while maintaining computational efficiency. Similarly, in [

49], an Attention-Based Conditional GAN incorporates attention layers within conditional GANs to better capture short-term patterns in data. These attention layers dynamically prioritize the most influential features, facilitating the generation of more realistic and context-aware conditional scenarios. In [

50], an HiLo (high frequency and low frequency) Attention layer has been used to model the low and high-frequency characteristics of the input data and use them as an input to the final attention layer. This structure is used in the Discriminator part of a GAN to produce more realistic scenarios. A transformer is introduced in the structure of the generator of GAN to capture the temporal features of wind and solar power generations [

51]. By using this structure, it can produce better short-term scenarios than some other popular scenario generation methods like Latin Hypercube Sampling approach. Since GANs have gained more attention than other generative deep networks, attention-based models have primarily been applied to these architectures. However, given the strong capability of attention mechanisms in capturing complex data characteristics, they are likely to be adopted in other deep generative networks soon.

2.6. Comparisons and Discussions

Deep learning methodologies—such as GANs, LSTMs integrated within GANs, VAEs, attention-based generative models, and diffusion models—have been increasingly applied to scenario generation in power systems and renewable energy contexts, owing to their capacity to process complex and high-dimensional training data. GANs are particularly effective at capturing intricate data distributions, enabling the generation of realistic and diverse scenarios for stochastic processes such as wind and solar energy outputs. Integrating LSTMs into GANs enhances their ability to model temporal dependencies, making them particularly well-suited for sequential data generation tasks such as hourly energy demand profiles and renewable energy forecasts. VAEs, on the other hand, provide a probabilistic framework for learning latent representations, which can be leveraged to generate scenarios with controlled variability and uncertainty. Attention-based generative models improve scenario quality by focusing on critical data features, ensuring the generation of scenarios with accurate representations of spatial and temporal correlations. Diffusion models, an emerging technique, refine noisy data through iterative denoising processes, offering robust solutions for generating scenarios in systems with high uncertainty and variability, such as renewable energy-integrated grids. However, GANs and their variants—such as LSTM-integrated GANs and attention-based GANs—have been employed more than other methods, as shown in

Figure 5. The reason for this is that GANs have provided better results than VAEs and are also easier to implement than Diffusion Models.

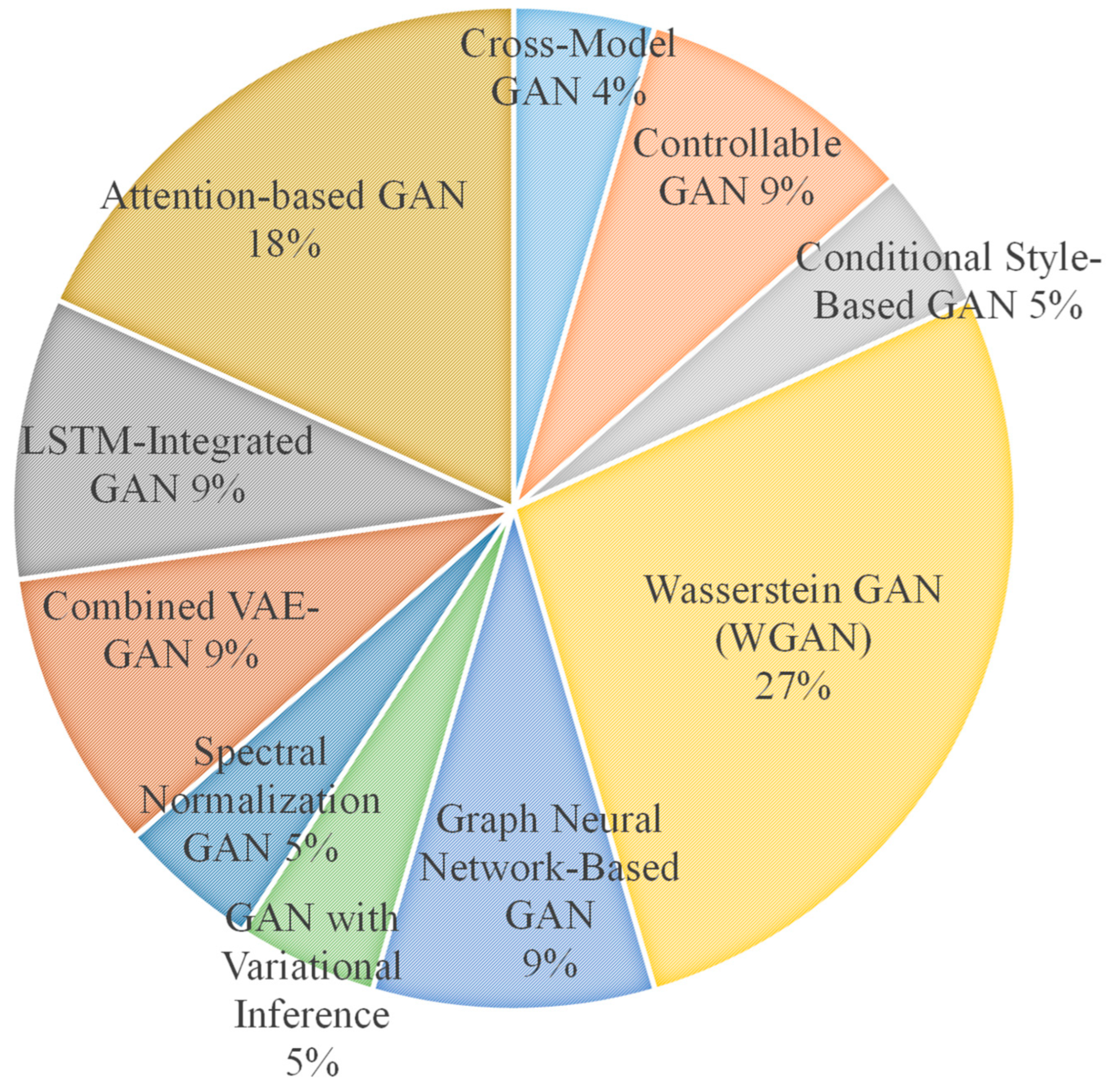

Figure 6 presents another graph comparing the various modifications of GANs. As shown, Wasserstein GANs and attention-based GANs are the most widely used GAN variants. This is primarily due to the ability of Wasserstein GANs to stabilize the training process and mitigate mode collapse, while attention-based GANs excel at capturing intricate details within the training data.

Compared to traditional scenario generation techniques, such as Monte Carlo simulation, deep learning methods offer several key advantages. First, they can efficiently generate diverse scenarios once trained, reducing the computational burden associated with repeated simulations. Second, deep learning methods inherently handle high-dimensional and nonlinear relationships in data, capturing correlations that may be overlooked in traditional techniques reliant on predefined probability distributions. Additionally, they are data-driven, learning directly from historical patterns rather than requiring prior assumptions, which allows them to adapt to complex and evolving system behaviors more effectively. This capability is particularly beneficial in renewable energy systems, where variability and uncertainty are pronounced.

3. Deep Learning for Scenario Reduction

Scenario reduction is a vital technique in data-driven decision-making processes today. It involves simplifying a large set of scenarios into a manageable subset while retaining essential information. As the interaction between transmission and distribution grids in power systems continues to grow, the importance of scenario reduction has become even more pronounced. In the context of deep learning, scenario reduction is increasingly integrated into neural network architectures in three different ways, which are discussed in the following subsections 3.1-3.3.

3.1. Clustering as a Part of Deep Networks for Scenario Reduction

This method integrates clustering techniques into deep learning architectures to reduce scenarios in large-scale datasets. Its performance can be summarized as below:

Embedding the Input Data: The deep network acquires a low-dimensional representation, or embedding, from high-dimensional input data. For example, an encoder within an autoencoder framework might be employed to transform the data into a concise latent space [

52].

Clustering in Latent Space: Once the data is embedded, a clustering approach like k-means is applied to the latent space. The clustering step identifies representative scenarios by grouping similar data points together.

Loss Function for Joint Optimization: To improve scenario reduction performance, a custom loss function is used that incorporates clustering objectives, which is a combination of a reconstruction loss (

), ensuring that the reduced scenarios can still approximate the original data, and clustering loss (

), encouraging tight clusters and well-separated cluster centers (e.g.,

k-means loss or pairwise distance loss):

where

is a weighting parameter.

Scenario Selection: After training, cluster centroids or representative points from each cluster are chosen as the reduced set of scenarios.

The only difference in the implementation of this method lies in the structure of the encoders and decoders, which can be either fully connected neural networks, as in [

52], or convolutional neural networks, as in [

53].

3.2. Generate a Large Number of Scenarios and Reduce Them

This method involves generating many scenarios upfront and then applying a separate reduction technique:

Scenario Generation: A large dataset of scenarios is generated using generative models like GANs or VAEs [

54].

Scenario Reduction: After generating the scenarios, apply a scenario reduction method like

k-Means [

16,

54], or variance-based continuation criterion [

46] to minimize the dataset size while preserving its diversity and representativeness.

3.3. Fast Scenario Reduction Using Deep Learning

This method leverages deep learning to transform and reduce scenarios rapidly. The fast scenario reduction using deep learning has three steps. These steps are given below [

55]:

Transform scenario data into a 2D image-like format.

Use a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) to process the “images.”

Output a reduced set of scenarios, represented as a smaller “image.”

The training of the DCNN involves comparing its outputs to those of a heuristic search-based scenario reduction method, using binary cross-entropy loss. The approach has been validated on a dataset simulating solar power generation and shows substantial speed improvements without compromising the quality of the reduced scenarios [

55]. This advancement makes the method particularly suitable for real-time applications in power system optimization.

3.4. Comparison and Discussion

Deep learning methodologies have shown great potential for scenario reduction, effectively tackling critical challenges in power systems and renewable energy applications. For example, integrating clustering techniques into deep neural networks provides a powerful framework for reducing scenarios in large-scale datasets. By using encoders to transform complex, high-dimensional data into a compact latent space, algorithms like k-means can pinpoint representative scenarios, preserving both the variety and fidelity of the original dataset. This technique is particularly valuable in power systems, where it can streamline renewable generation profiles or load predictions, paving the way for more efficient optimization and planning workflows. Another effective approach involves generating a large number of scenarios upfront and applying machine learning-driven reduction techniques. While similar to traditional methods, this approach offers a distinct advantage in terms of speed, streamlining the reduction process without sacrificing representativeness. Additionally, fast scenario reduction using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) has gained recognition as a standout option for real-time problems. By transforming scenario data into a two-dimensional image-like format and processing it using CNNs, this method allows for rapid scenario reduction while maintaining high quality. Optimizing with binary cross-entropy loss and comparing CNN outputs to traditional heuristic-based methods makes it a scalable and efficient alternative for handling renewable energy datasets, like solar generation profiles or wind power curves, for short-term operational planning where speed and accuracy are critical.

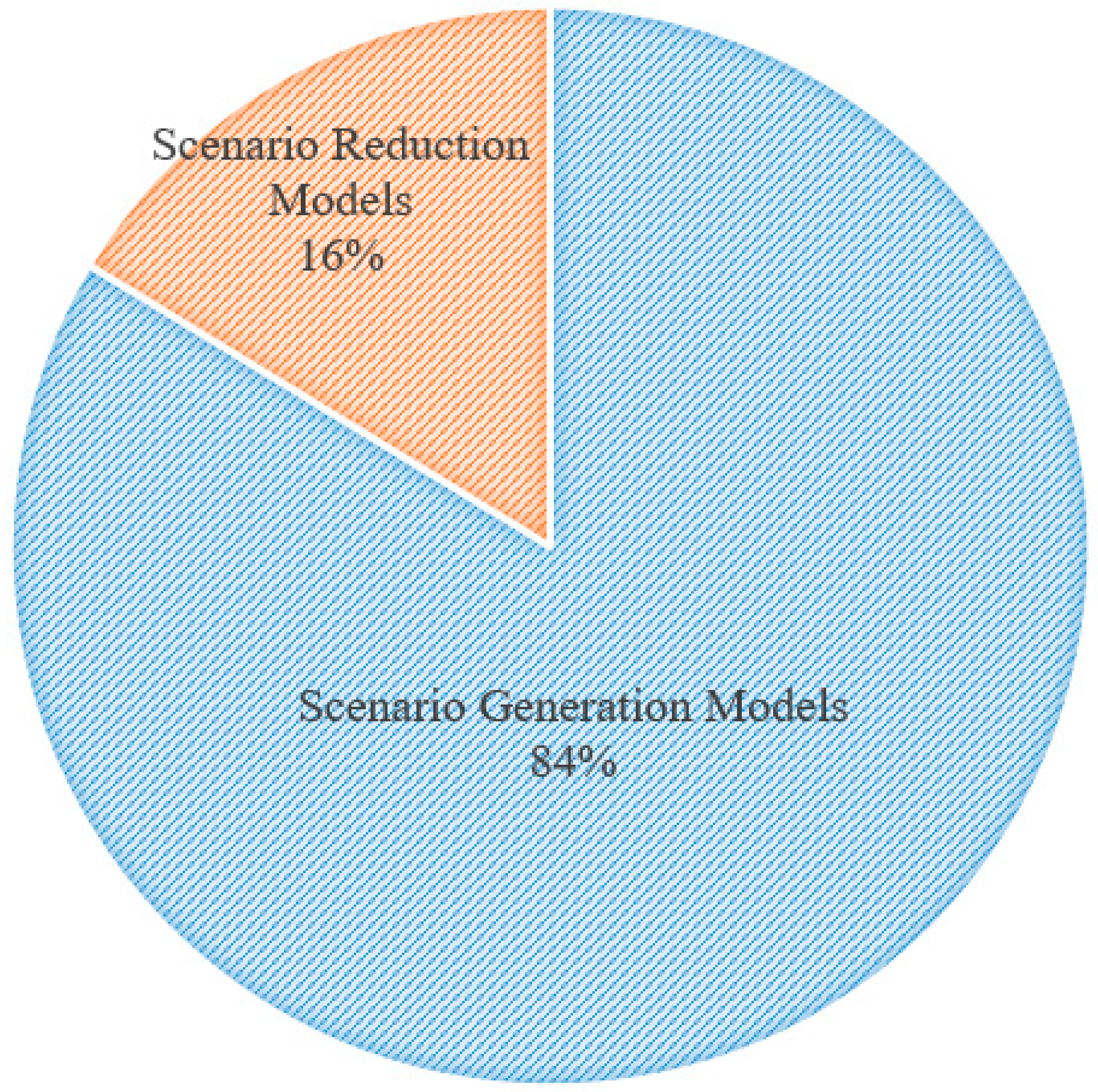

When examining the sections on scenario generation and reduction techniques, it is evident that the number of papers focusing on scenario reduction is significantly lower than those dedicated to scenario generation, as shown in

Figure 7. This discrepancy arises because reducing the number of scenarios may overlook some key features of the data generated through network training, which is undesirable. Additionally, training a network to tackle both scenario generation and reduction can be computationally expensive.

Compared to conventional scenario reduction methods, like forward or backward selection, deep learning-based techniques offer a key advantage. Conventional methods rely on heuristics or predefined rules to iteratively add or remove scenarios based on similarity or representativeness. While effective, these methods can be computationally expensive for high-dimensional datasets and may not fully capture the underlying data distribution. Deep learning, by contrast, leverages data-driven optimization to directly learn the relationships and patterns within the dataset, providing a more holistic representation.

4. Challenges and Future Research Directions in Deep Learning for Scenario Analysis

This section delves into the critical challenges associated with applying deep learning techniques to scenario generation and reduction within modern power systems. It also outlines potential research directions and advancements to address these challenges and meet future requirements for power system optimization under uncertainty.

Table 3 and

Table 4 summarize these challenges and outline corresponding strategies for overcoming them in scenario generation and reduction, respectively.

The challenges outlined in

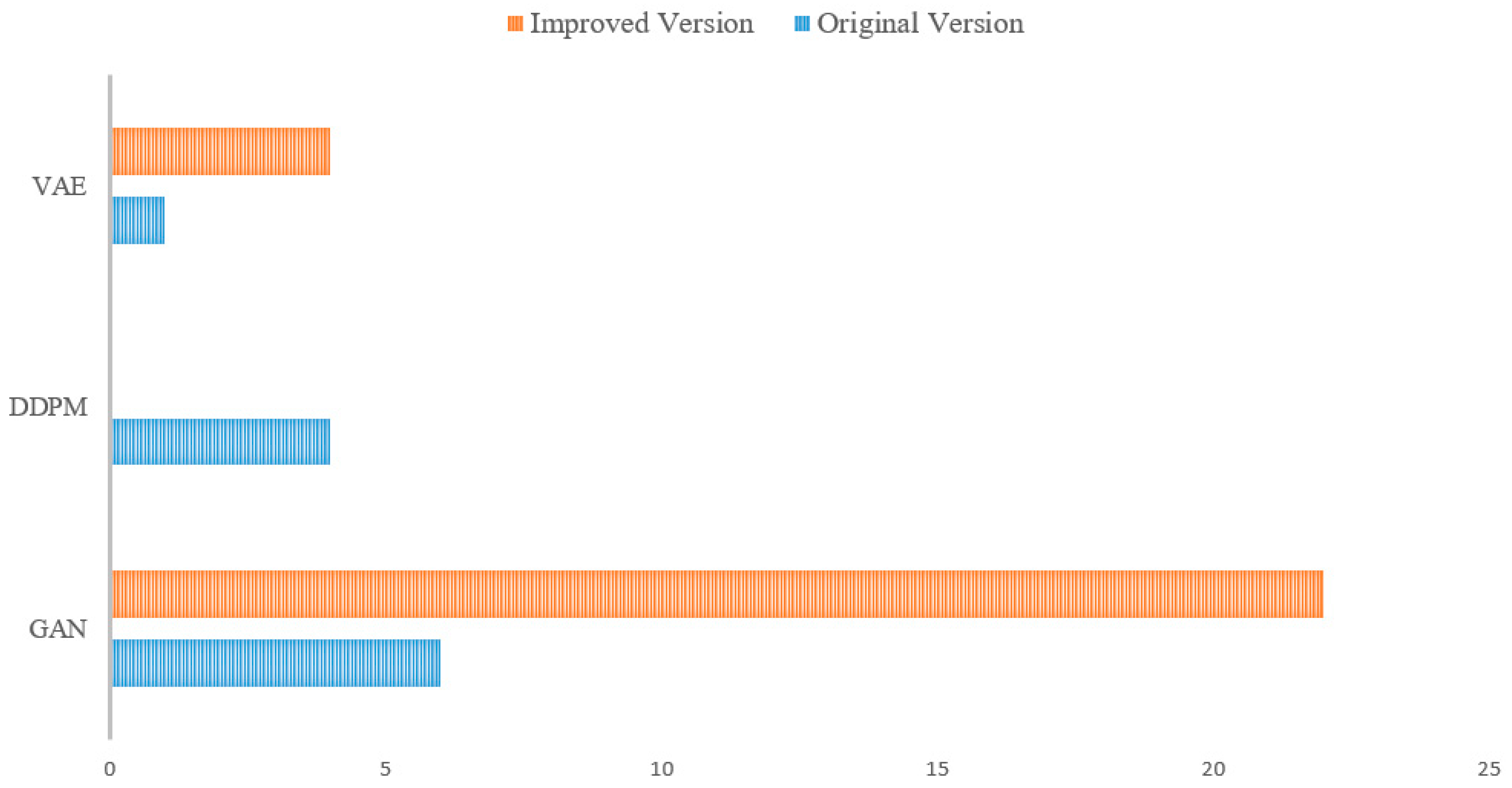

Table 3 emphasize the complexities of integrating deep learning into scenario generation for power systems. Key challenges, such as model stability, computational costs, and interpretability, remain significant hurdles, requiring innovative solutions, such as the development of hybrid architectures and the application of explainable AI techniques. This is evident in

Figure 8, where, apart from DDPM—a relatively novel model—existing literature has primarily focused on modifying established models to address their respective limitations. As indicated in

Table 3, addressing scalability through distributed learning can enhance the efficiency of large-scale scenario generation while improving training robustness.

Table 4 highlights the importance of balancing scenario reduction efficiency with information preservation and real-time adaptability. Advanced clustering techniques and deep reinforcement learning offer promising pathways to enhance scenario reduction quality without excessive computational overhead. By developing hybrid methods that integrate deep learning with numerical optimization, researchers can ensure that scenario reduction remains both scalable and practical for evolving energy systems.

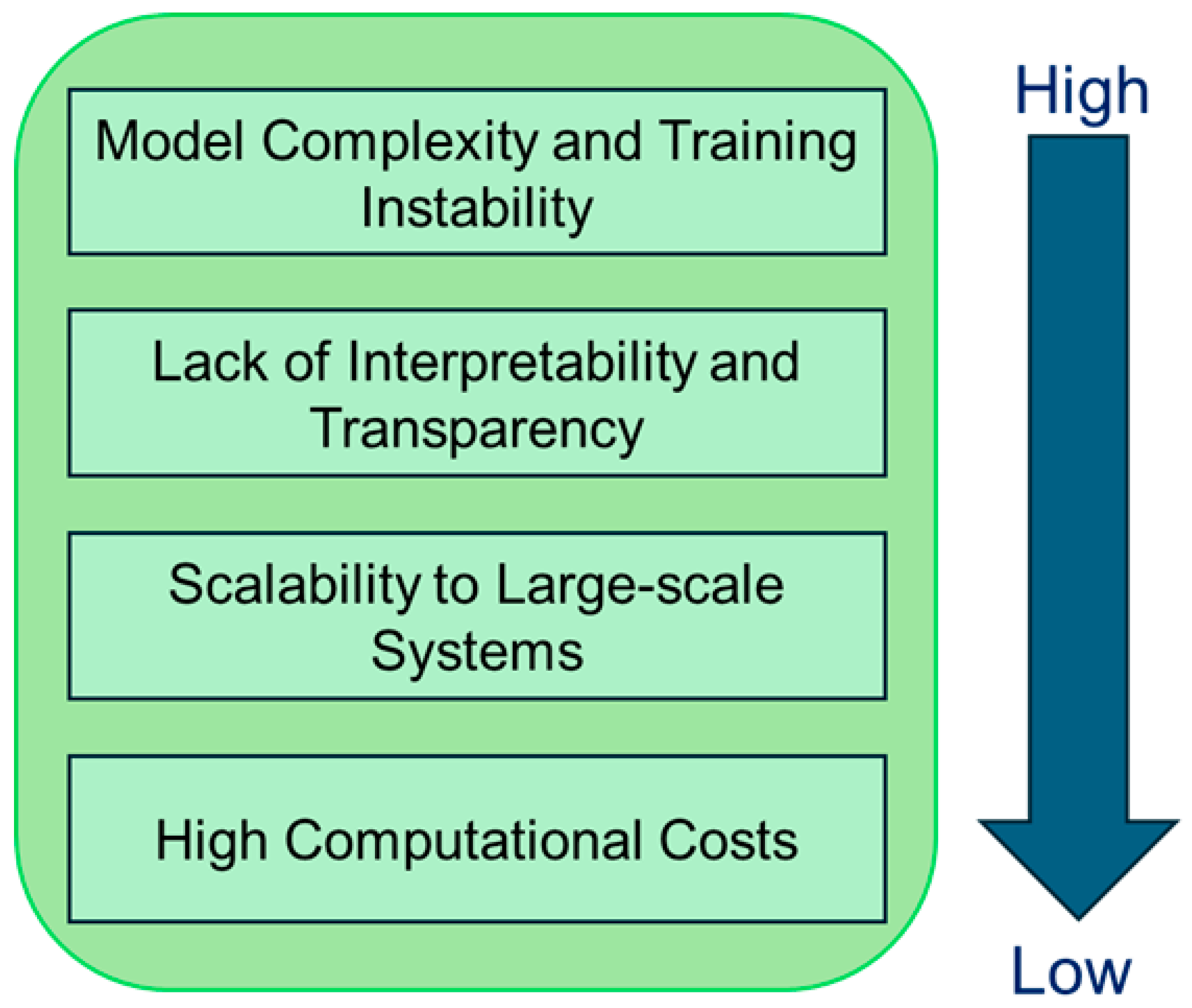

Figure 9 illustrates the criticality levels of various challenges listed in

Table 3. The highest criticality is associated with the model complexity and training, followed by the challenges of a lack of interpretability and transparency, scalability, and computational costs. The computational costs and scalability have relatively lower criticality levels due to advancements in computational resources and implementation methods, such as the emerging application of quantum computing in power systems [

56]. Similarly,

Figure 10 presents the criticality levels of different challenges shown in

Table 4. The loss of critical information is deemed highly critical for scenario reduction, as it can significantly impact various power system studies based on stochastic programming. This is followed by challenges in real-time processing, adaptability, and computational complexity.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented a comprehensive review of deep learning applications in scenario generation and reduction, highlighting their critical role in addressing uncertainties in modern power systems. By leveraging advanced models, such as GANs, VAEs, diffusion models, and LSTMs, researchers have achieved significant progress in generating realistic scenarios that reflect the complexities of renewable energy sources, electricity prices, and load demands. Additionally, innovative scenario reduction techniques have streamlined the optimization process, reducing the computation burden and enabling more efficient decision-making in renewable energy-integrated power systems.

Despite these advancements, challenges related to model complexity, computational demands, and interpretability still persist. Overcoming these challenges through the development of more robust and transparent architectures, along with scalable real-time frameworks, represents a critical direction for future research.

Ultimately, integrating deep learning with scenario analysis—alongside scenario generation and reduction—holds significant potential for enhancing the reliability and sustainability of renewable energy-integrated power systems. This integration paves the way for smarter, more adaptive energy management in an era of increasing reliance on renewable energy sources.

References

- A. Ahmed, M. Khalid, “A review on the selected applications of forecasting models in renewable power systems,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 100, pp. 9-21, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amjady, N. Chapter 4: Short-Term Electricity Prices Forecasting. In Electric Power Systems: Advanced Forecasting Techniques and Optimal Generation Scheduling; CRC Press; Taylor & Francis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- D. M. Minhas, R. R, Khalid and G. Frey, “Activation of electrical loads under electricity price uncertainty,” in IEEE International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE), pp. 16, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Rahmani, N. Amjady, “A new optimal power flow approach for wind energy integrated power systems,” Energy, vol. 134, pp. 349-359, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Heitsch, W. Römisch, “Scenario reduction algorithms in stochastic programming,” Computational Optimization and Applications, vol. 24, pp. 187-206, Feb. 2003. [CrossRef]

- I. Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S/ Ozair, A. Courville, and Y. Bengio, “Generative adversarial networks,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 63, No. 11, pp. 139 – 144, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Sherstinsky, “Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network,” Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, vol, 404, pp. 1-28, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, F. Liu, W. Yang, S. Peng, and J. Zhou, “A survey of convolutional neural networks: Analysis, applications, and prospects,” IEEE Trans. Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 33, No. 12, pp. 6999-7019, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Kousounadis-Knousen, I. K. Bazionis, A. P. Georgilaki, F. Catthoor, P. S. Georgilakis, “A review of solar power scenario generation methods with focus on weather classifications, temporal horizons, and deep generative models,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 15, pp. 1-29, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, J. Zhou, and B. Chen, “Review of wind power scenario generation methods for optimal operation of renewable energy systems,” Applied Energy, vol. 280, pp. 1-18, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, Z. Ren, M. Fan, W. Li, Y. Xu, Y. Jiang, W. Xi, “A review of scenario analysis methods in planning and operation of modern power systems: Methodologies, applications, and challenges,” Electric Power Systems Research, vol. 205, pp. 1-20, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Hosseini, J.-F. Toubeau, Z. De Grève, Y. Wang, N. Amjady, F. Vallée, “Data-Driven Multi-Resolution Probabilistic Energy and Reserve Bidding of Wind Power,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 85-99, January 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. M. M. Bendaoud, N. Farah, S. B. Ahmed, “Comparing generative adversarial networks architectures for electricity demand forecasting,” Energy and Buildings, vol. 247, pp. 1-12, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Yilmaz, C. Laudagé, R. Korn, and S. Desmettre, “Electricity GANs: Generative adversarial networks for electricity price scenario generation,” Commodities, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 254-280, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Rastgoo, N. Amjady, S. Islam, I. Kamwa, S. M. Muyeen, “Extreme Outage Prediction in Power Systems Using a New Deep Generative Informer Model,” International Journal of Electric Power & Energy Systems, Vol. 167, June 2025, 110627. [CrossRef]

- C. Huo, C. Peng, Z. Hao, X. Rong, X. Dong, and S. Yang, “Scenario generation method considering the uncertainty of renewable energy generations based on generative adversarial networks,” in International Conference on Energy and Electrical Power Systems (ICEEPS), pp. 130-134, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Rastgoo, N. Amjady, and H. Zareipour, “A Deep Generative Model for Selecting Representative Periods in Renewable Energy-Integrated Power Systems,” Applied Soft Computing, Vol. 165, Nov. 2024, 112107. [CrossRef]

- M. Kang, R. Zhu, D. Chen, C. Li, W. Gu, X. Qian, “A cross-modal generative adversarial network for scenarios generation of renewable energy,” IEEE Trans. Power Systems, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 2630 – 2640, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Qiao, T. Pu, and X. Wang, “Renewable scenario generation using controllable generative adversarial networks with transparent latent space,” CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 66 – 77, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Dong, X. Chen, and Q. Yang, “Data-driven scenario generation of renewable energy production based on controllable generative adversarial networks with interpretability,” Applied Energy, vol. 308, pp. 1-13, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Yuan, B. Wang, Y. Sun, X. Song, and J. Watada, “Conditional style-based generative adversarial networks for renewable scenario generation,” IEEE Trans. Power Systems, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 1281 – 1296, March 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiaojie Pan, M. Zhang, Y. Wang, S. Du, and T. Ding, “Renewable scenario generation under extreme meteorological conditions via improved conditional generative adversarial networks,” in International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), pp. 559-564, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Q. Ai, F. Xiao, R. Hao, T. Lu, “Typical wind power scenario generation for multiple wind farms using conditional improved Wasserstein generative adversarial network,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 114, pp. 1-12, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, D. Li, and X. Fu, “A novel Wasserstein generative adversarial network for stochastic wind power output scenario generation,” IET Renewable Power Generation, vol. 18, no. 16, pp. 3537-4232, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, “Improved conditional generative adversarial network-based approach for extreme scenario generation in renewable energy sources,” in International Conference on Civil Aviation Safety and Information Technology (ICCASIT), pp. 1391-1398, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, H. Wei, K. Zhou, S, Tian, “WGAN-GP generating wind power scenarios and using BP neural network for classification evaluation,” in International Seminar on Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Information Technology (AINIT), pp. 1430-1436, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Ding, G. He, Y. Sun, X, Zhang, Y. Cai, and Z. Hu, “Refined wind-solar scene generation research based on improved deep convolutional CWGAN-GP model,” in Asian Conference on Frontiers of Power and Energy (ACFPE), pp. 414-418, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, J. Yu, L. Gong, M. Liu, and X. Xiang, “A GCN-based adaptive generative adversarial network model for short-term wind speed scenario prediction,” Energy, vol. 294, pp. 1-20, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Cho, S. Liu, H. Zhu, and D. Lee, “Wind power scenario generation using graph convolutional generative adversarial network,” in IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), pp. 1-5, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wei, Z. Hongxuan, D. Yu, W. Yiting, D. Ling, and X. Ming, “Short-term optimal operation of hydro-wind-solar hybrid system with improved generative adversarial networks,” Applied Energy, vol. 250, pp. 389-403, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Fan, and D. Li, “Spectral normalization generative adversarial networks for photovoltaic power scenario generation,” IET Renewable Power Generation, vol. 99, pp. 1-10, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Yang, J. Yan, Y. Hong, J. Yang, K. Wang, and Y. Li, “Scenario generation of PV power based on DDPM,” in Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), pp. 1-5, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, Z. Mao, Y. Sun, X. Xu, “Short-term wind power scenario generation based on conditional latent diffusion models,” IEEE Trans. Sustainable Energy, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 1074 – 1085, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Meng, Y. Nan, G. Zheng, J. Shen, Y. Mi, and C. Lu, “Scenario generation of renewable energy resources based on denoising diffusion probability models,” in 4th International Conference on Advanced Electrical and Energy Systems, pp. 1-6, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, D. Peng, D. Huang, H. Zhao, and B. Qu, “Low-carbon optimization scheduling of IES based on enhanced diffusion model for scenario deep generation,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 167, pp. 1-24, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhai, S. Zhang, J. Chen, and Q. He, “Autoencoder and its various variants,” in IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), pp. 1-5, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Kim, D. Lee, S. Hwangbo, “A deep-learning framework for forecasting renewable demands using variational auto-encoder and bidirectional long short-term memory,” Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, vol. 38, pp. 1-15, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Xiao, Z. Liu, X. He, J. Zhang, and H. Liu, “Wind power output scenario generation based on importance weighted autoencoder,” in International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), pp. 1-6, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Peng, Z. Sun, and M. Liu, “Medium- and long-term scenario generation method based on autoencoder and generation adversarial network,” in International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), pp. 1-7, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, X. Peng, W. Cui, Y. Xu, J. Liu, H. Yuan, C. Sing Lai, and L. L. Lai, “A novel scenario generation method of renewable energy using improved VAEGAN with controllable interpretable features,” Applied Energy, vol. 363, pp. 1-15, June 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Hochreiter, J. Schmidhuber, “Long Short-Term Memory,” Neural Computation, Vol. 9, No. 8, pp. 1735–1780, Nov. 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Liang, W. Tang, “Wind power scenario generation for microgrid day-ahead scheduling using sequential generative adversarial networks,” in IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids, pp. 1-6, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Liang, W. Tang, “Sequence generative adversarial networks for wind power scenario generation,” IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 110-118, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, S. Zhang, Y. Xiang, J. Liu, J. Liu, X. Han, and F. Teng, “LSTM auto-encoder based representative scenario generation method for hybrid hydro-PV power system,” IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution, vol. 14, no. 24, pp. 5935-5943, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Stappers, N. G. Paterakis, K. Kok, M. Gibescu, “A class-driven approach based on long short-term memory networks for electricity price scenario generation and reduction,” IEEE Trans. Power Systems, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 3040-3050, July 2020. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, November 2017; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- L. Ye, Y. Peng, Y. Li, and Z. Li, “A novel informer-time-series generative adversarial networks for day-ahead scenario generation of wind power,” Applied Energy, vol. 364, pp. 1-15, June. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, H. Yu, Z. Liu, F. Li, X. Wu, B. Cao, C. Zhang, D. Liu, “Long-term scenario generation of renewable energy generation using attention-based conditional generative adversarial networks,” IET Energy Conversion and Economics, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. pp. 15-27, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, R. Zhu, “A photovoltaic power scenario generation method based on HiLo-WGAN,” in International Forum on Electrical Engineering and Automation (IFEEA), pp. 636-640, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Gu, J. Xu, D. Ke, Y. Deng, X. Hua, and Y. Yu, “Short-term output scenario generation of renewable energy using transformer–wasserstein generative adversarial nets-gradient penalty,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 24, pp. 1 – 20, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Liang, W. Tang, “Scenario reduction for stochastic day-ahead scheduling: A mixed autoencoder based time-series clustering approach,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 2652-2662, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Peng, L. Ye, P. Li, T. Gong, “A deep convolutional embedded clustering method for scenario reduction of production simulation,” in International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), pp. 1-6, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Huang, L. Liang, Z. Dai, S. Cao, H. Zhang, X. Zhao, J. Hou, H. Li, W. Ma, and L. Che, “Scenario reduction of power systems with renewable generations using improved time-GAN,” in International Conference on Smart Grid and Energy, pp. 1-9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gao, D.W. Fast scenario reduction for power systems by deep learning. Signal Processing 2019, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Ajagekar, F. You, “Quantum computing based hybrid deep learning for fault diagnosis in electrical power systems” Applied Energy, Vol. 303, pp. 1-31, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).