Submitted:

13 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction:

- To explain the core principles and communication modes of V2X systems, including V2V, V2I, V2N, and V2P, and their applications in transportation networks.

- To analyze the architectural frameworks supporting V2X, with a focus on 5G, PC5 interface, and LTE-Uu protocols.

- To evaluate the benefits and limitations of V2X in enhancing road safety, minimizing collisions, and enabling efficient traffic flow.

- To develop and apply mathematical models that quantify key V2X performance metrics, such as latency, packet delivery ratio, and throughput.

- To conduct simulation-based performance analysis for various deployment scenarios, including traffic density variations and RSU placement.

2. Why V2X (Benefits)?

- Warn if there is sudden braking in the vehicles ahead.

- Help drivers avoid collisions at intersections by alerting drivers if another vehicle approaching the intersection may run the red light. If you are the driver who might run a red light, V2X will send you an alert of a potential collision with cross traffic. Warn drivers of another vehicle in their blind spot.

- Inform drivers of bad road weather conditions, warning drivers of unsafe road conditions experienced by others ahead, enabling the driver to slow down or change routes altogether.

- V2X also has the potential to help enable warnings about pedestrians in crosswalks n crosswalks or work zones ahead.

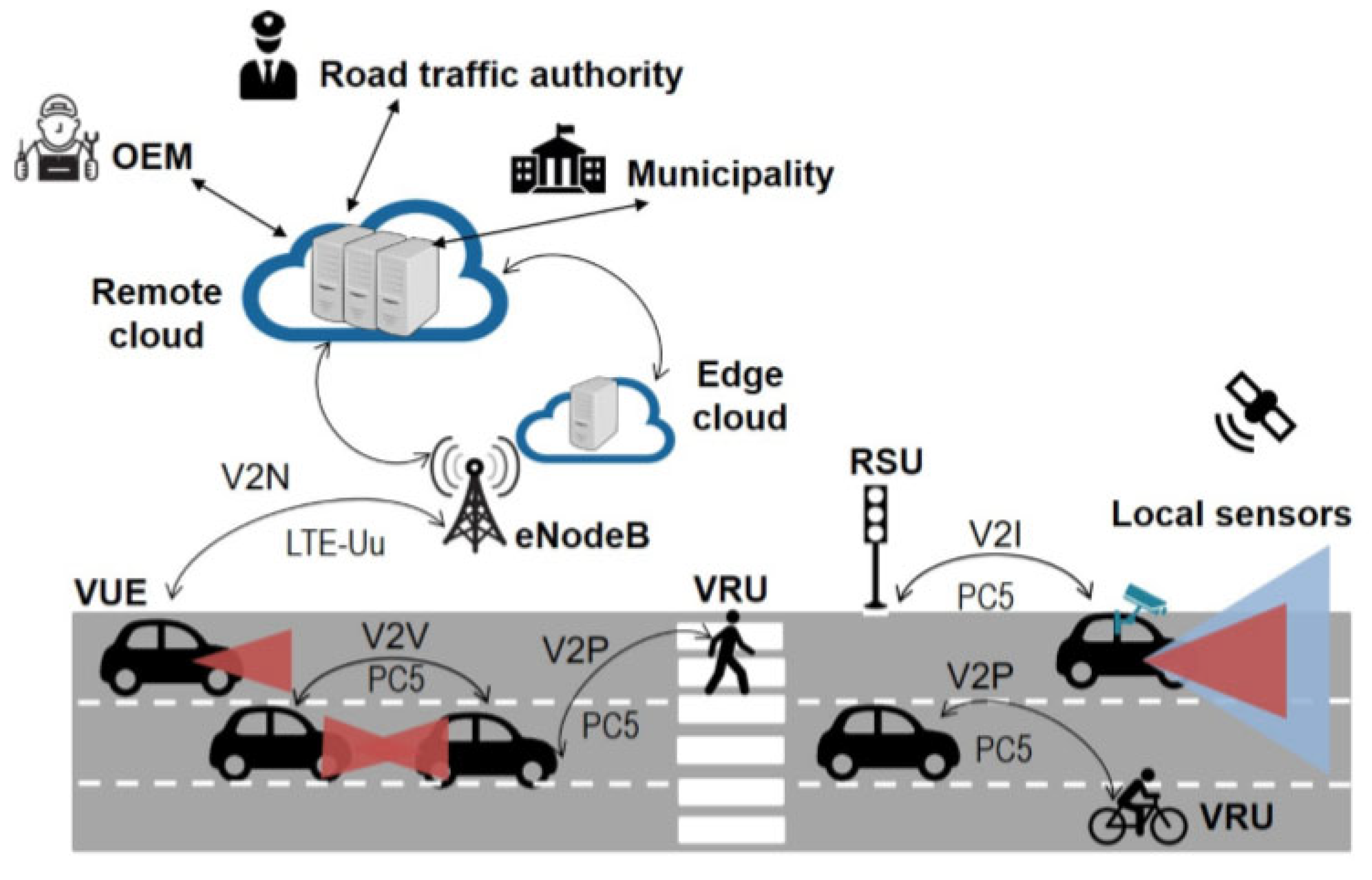

3. Modes of Operation of V2X:

- Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V): In this mode, vehicles will be allowed to exchange data between them directly, and a mesh network typically is formed, which helps to make better decisions through information exchange among the existing nodes. To do this, an authorization must firstly be obtained from the network operator. V2V application information involves location of the vehicle, vehicle attributes, traffic dynamics, etc., and the applications work by transmitting messages carrying these information. A prerequisite to create a V2V communication, is transforming data from one to many with minimum latency, this is done by keeping the message payloads flexible for better communication, and also by broadcasting Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) messages [6].

- Vehicle-to-Pedestrian (V2P): In this mode the data will be exchanged between vehicles and other road users those are not using vehicles(also known as Vulnerable Road Users (VRUs)), like bicyclists, pedestrians, etc. Information messages, warning messages, and alerts can be transmitted and received between the drivers and pedestrians by using User Equipment (UEs) that are provided for each of them [7]. The communication between vehicles and VRUs can be existed even when they are in Non-Line of Sight, and also under low visibility cases such as dark night, heavy rain, foggy weather, etc. The sensitivity of pedestrian UEs is lower than vehicular UEs because of the antenna and battery capacity difference. So V2P application supported UEs cannot transmit continuous messages like V2V supported UEs.

- Vehicle-to-Network (V2N): V2N transmission is between a vehicle and a V2X application server. A UE supporting V2N applications can communicate with the application server supporting V2N applications, while the parties communicate with each other using Evolved Packet Switching (EPS). V2X services are required for different applications and operation scenarios. It will help mobile operators to communicate the tasks of the Remote Switching Unit (RSU) over its network, reducing time to market, cost and eliminating the complexity of designing and running a purpose-built network for V2I as it could include communication between vehicles and the server via 4G or even 5G network. It does not need to be as precise as V2V but reliability is crucial

- Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I): V2I application information is transmitted through a RSU or locally available application server. RSUs are roadside stationary units, which act as a transceiver. RSUs or available application servers receive the broadcast message and transmits the message to one or more UEs supporting V2I application. V2I can provide us with information, such as available parking space, traffic congestion, road condition, etc. Due to the high cost and lengthy deployment time, its application or installation is more challenging [8].

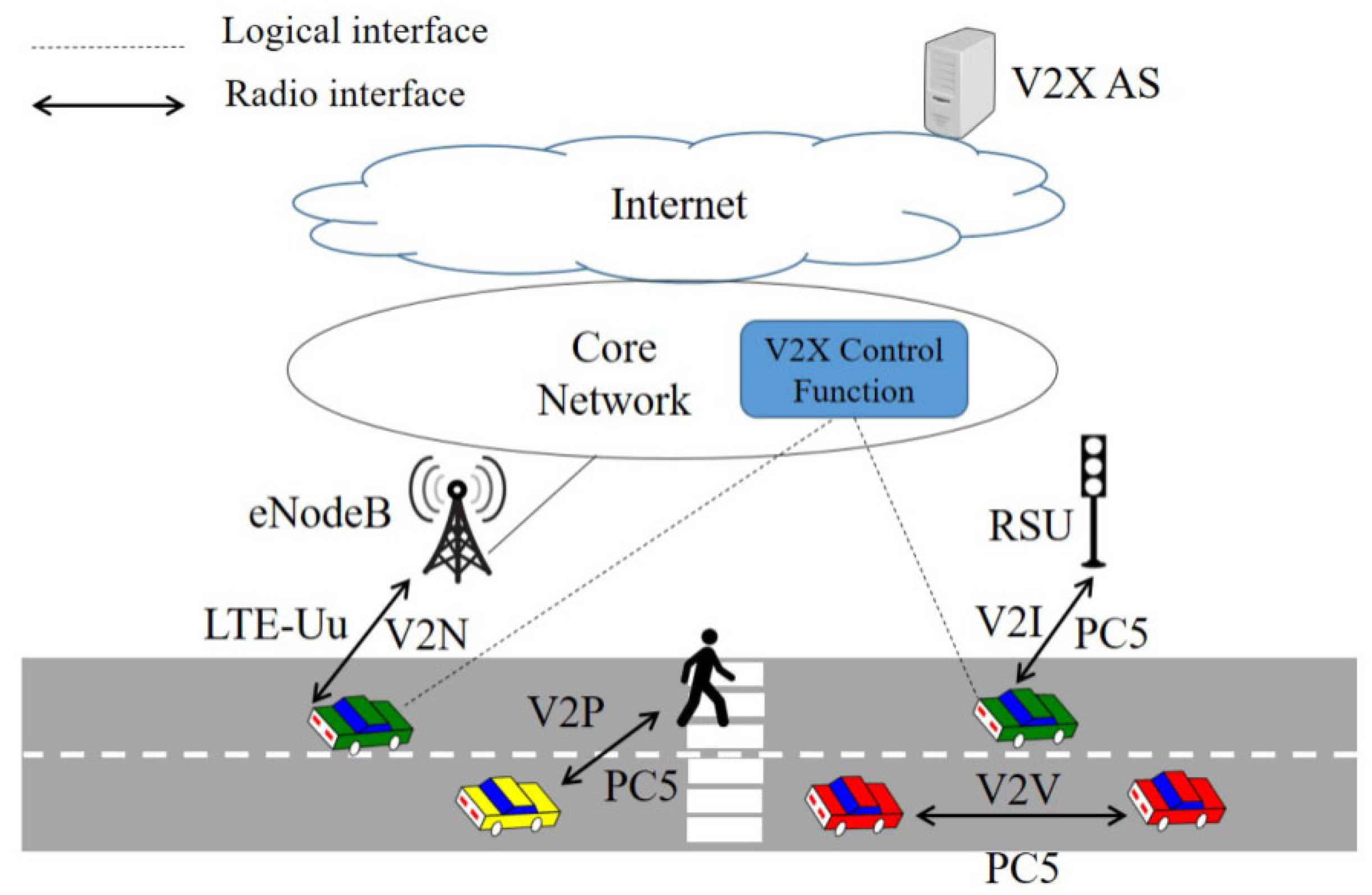

4. V2X Architecture:

- PC5 Based Communication: V2X messages are transmitted via PC5 and are received by UEs through PC5 and MBMS. With PC5, V2X messages are received by an RSU serving as a UE. Afterward, the RSU forwards the processed message to a V2X Application Server using the V1 interface. V2X Application Server processed messages are distributed to UEs through MBMS [10]. In this mode, the cellular network can deliver information from extended range. It enables advanced driving assistance applications.

- LTE-Uu based and PC5 based V2X Communication without MBMS: This mode supports communication of UE-type RSUs via PC5 for both transmission and reception of V2X messages. V2X application servers can communicate with the RSU through a cellular network. For instance, LTE-Uu is used to communicate V2X messages beyond the direct PC5 communication range. Based on such hybrid use of LTE-Uu and PC5-based V2X communications, MBMS broadcast of downlink data transmissions could be negligible [9]. This operation mode has got three components:

- To ensure adequate coverage to the available traffic, stationary infrastructures like UE-type RSUs are incorporated. This RSUs and UEs communicate with each other for V2X over PC5. The V2X Application Servers can also communicate with the UE-type RSUs.

- UE-type RSUs obtain V2X messages from other UEs via PC5. The V2X application of the RSUs evaluates whether the message should be routed to the V2X Application Servers over the LTE-Uu connection or not, in case of a larger target area (i.e. larger V2X communication coverage over PC5). The target area and the size of the area are determined by the V2X Application Servers, where the V2X messages are distributed. In the process of determining the coverage area, V2X Application Servers can communicate with each other.

- V2X downlink (‘Sidelink' in terms of D2D Communication) messages are sent by V2X Application Servers to the available RSU in the target distribution area. Afterward, the received message is broadcast by RSUs over PC5. UEs available in the same region are free to receive those broadcast data. In this process, vehicles operate using V2V/V2P services. When the UEs are employed as RSUs, they operate in a hybrid mode with simultaneous V2X communications over PC5 and LTE-Uu. These hybrid operations are also performed by UEs when they are unable to obtain a V2X signal directly from distant UEs via PC5 [12].

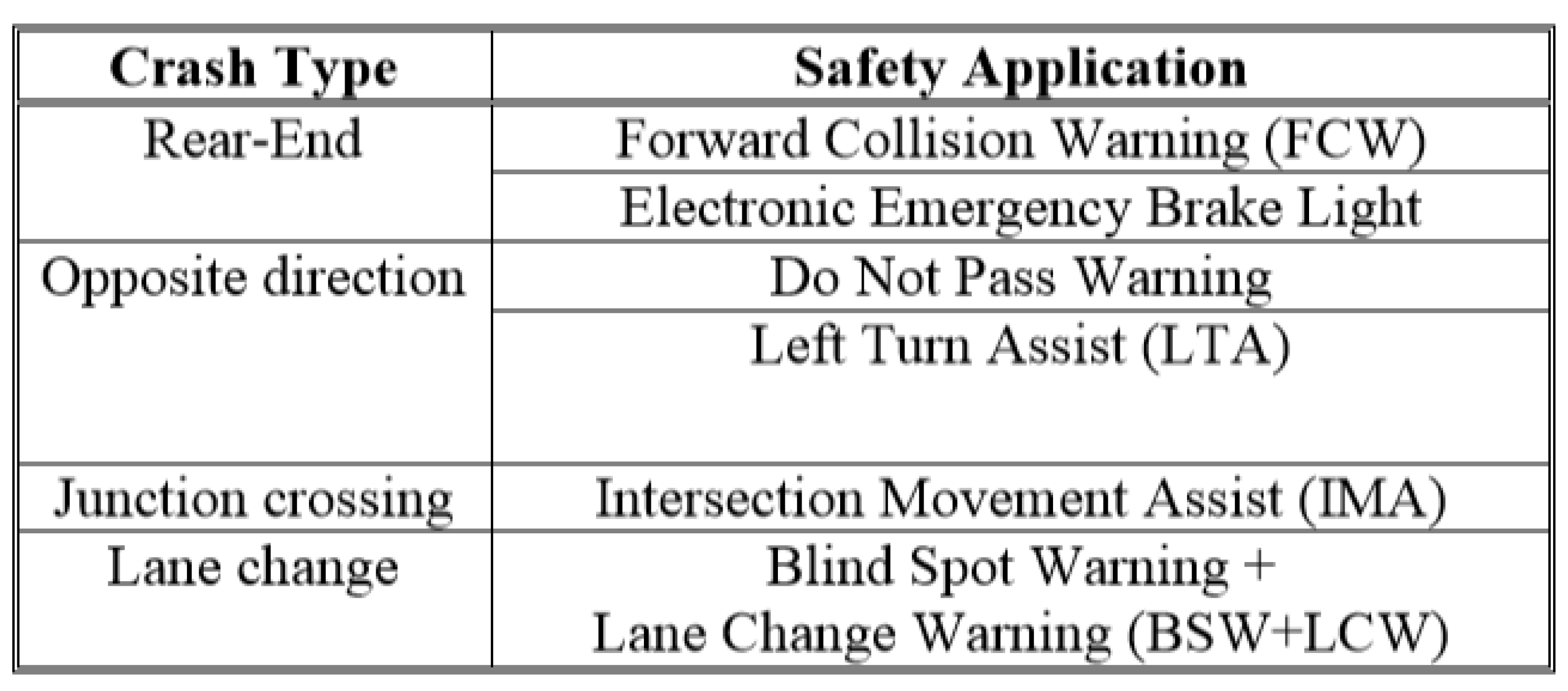

5. V2X Applications:

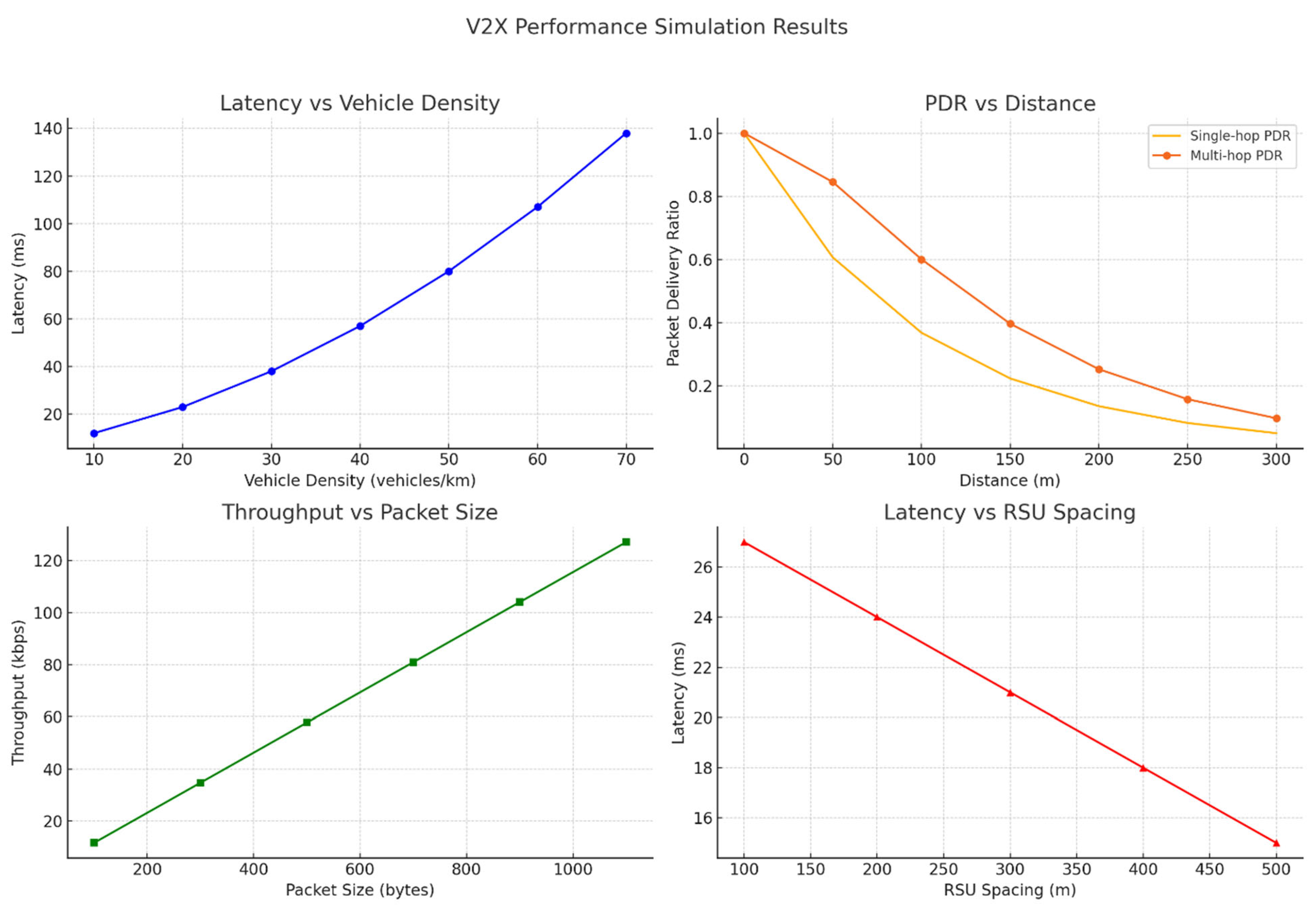

6. Mathematical Modeling and Performance Analysis

6.1. Assumptions and Network Model:

- Vehicles are distributed according to a Poisson Point Process (PPP) with a density λ_v vehicles/km.

- RSUs (Road Side Units) are distributed linearly along the road with a fixed spacing D.

- Communication occurs over a shared wireless channel using OFDM.

- Signal propagation follows a standard path-loss model with a path-loss exponent η.

- Transmit power is fixed and identical for all vehicles and infrastructure nodes.

6.2. Latency Model:

- L_proc: processing delay at sender and receiver (assumed to be ~5ms)

- L_tx = Packet Size / Bandwidth

- L_prop = d / c (distance divided by speed of light ~3x10^8 m/s)

- L_queue: depends on traffic density and buffer capacity (modeled via M/M/1 queueing system)

- Packet size = 500 bytes

- Bandwidth = 10 MHz

- Distance = 100 m

6.3. Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)

6.4. Throughput Model:

- Packet Size = 500 bytes

- L_total = 25.4 ms (real condition)

- PDR = 0.367

6.5. Simulation Results and Analysis

7. V2X Limitations and Challenges:

8. Conclusions:

References

- Y. Shi, X. H. Y. Shi, X. H. Peng, and G. Bai, “Efficient V2X Data Dissemination in Cluster-Based Vehicular Networks”, The Seventh International Conference on Advances in Vehicular Systems, Technologies and Applications, IARIA, 2018.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vehicle-to-everything.

- Molinaro, and C. Campolo, “5G for V2X Communications”, University Mediterranea of Reggio Calabria, Loc. Feo di Vito, Reggio Calabria, Italy.

- https://www.transportation.gov/testimony/driving-safer-tomorrow-vehicle-vehicle-communications-and-connected-roadways-future.

- 3GPP TS 22.185, “Service requirements for V2X services”, Release 15, 2018.

- “Radio Interface Standards of Vehicle-to-Vehicle and Vehicle-to-Infrastructure Communications for Intelligent Transport System Applications”, Recommendation ITU-R M.2084-0, September 2015.

- Dr. M. Vanderveen, and K. Shukla, “Cellular V2X Communications Towards 5G”, 5G Americas (White Paper), March 2018.

- M. T. Kawser, M. S. Fahad, S. Ahmed, S. S. Sajjad, and H. A. Rafi, “The Perspective of Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) Communication towards 5G”. IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security 2019, 19. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP TS 23.285, “Architecture enhancements for V2X services”, Release 15, 2018.

- E. Dahlman, S. E. Dahlman, S. Parkvall, and J. Sköld, “4G LTE - Advanced Pro and The Road to 5G”, Elsevier Ltd., pp. 461486, ISBN: 978-0-12-804575-6.

- M. Amadeo, C. M. Amadeo, C. Campolo, A. Molinaro, J. Harri, C. E. Rothenberg, and A. Vinel, “Enhancing the 3GPP V2X Architecture with Information-Centric Networking”, Future Internet, MDPI journal, 2019.

- Zi. Liu, Zh. Liu, Z. Meng, X. Yang, L. Pu, and L. Zhang, “Implementation and performance measurement of a V2X communication system for vehicle and pedestrian safety. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2016, 12. [Google Scholar]

- CSAE, Cooperative Intelligent Transportation System, Vehicular Communication, Application Layer Specification and Data Exchange Standard, T/CSAE 0053-2017, CSAE: Beijing, China, 2017.

- J. Wang, Y. Shao, Y. Ge, and R. Yu, “A Survey of Vehicle to Everything (V2X) Testing. Sensors 2019. [Google Scholar]

- J. Harding, G. R. Powell, R. Yoon, J. Fikentscher, C. Doyle, D. Sade, M. Lukuc, J. Simons, and J. Wang, “Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communications: Readiness of V2V Technology for Application”, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE. Washington, DC 20590, August 2014.

- N. Lu, N. Cheng, N. Zhang, X. Shen, and J. W. Mark, “Connected Vehicles: Solutions and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- H. M. Tsai, W. Viriyasitavat, O. K. Tonguz, C. Saraydar, T. Talty, and A. Macdonald, “Feasibility of in-car wireless sensor networks: A statistical evaluation,” in Proc. IEEE SECON, San Diego, CA, USA, June 2007.

- F. S. Eisenlohr, “Interference in Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication Networks Analysis, Modeling, Simulation and Assessment”, Handbook, KIT Scientific Publishing 2010.

- Q. I. Ali, "Design, implementation & optimization of an energy harvesting system for VANETs’ road side units (RSU). IET Intelligent Transport Systems 2014, 8, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Q. I. Ali, "An efficient simulation methodology of networked industrial devices," in Proc. 5th Int. Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices, 2008, pp. 1-6.

- Q. I. Ali, "Security issues of solar energy harvesting road side unit (RSU). Iraqi Journal for Electrical & Electronic Engineering 2015, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Q. I. Ali, "Securing solar energy-harvesting road-side unit using an embedded cooperative-hybrid intrusion detection system. IET Information Security 2016, 10, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Ibrahim, "Design & Implementation of High-Speed Network Devices Using SRL16 Reconfigurable Content Addressable Memory (RCAM). Int. Arab. J. e Technol. 2011, 2, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- M. H. Alhabib and Q. I. Ali, "Internet of autonomous vehicles communication infrastructure: a short review. Diagnostyka 2023, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Q. I. Ali, "Realization of a robust fog-based green VANET infrastructure. IEEE Systems Journal 2022, 17, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar]

- Q. I. Ali and J. K. Jalal, "Practical design of solar-powered IEEE 802.11 backhaul wireless repeater," in Proc. 6th Int. Conf. on Multimedia, Computer Graphics and Broadcasting, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).