1. Introduction

To achieve a successful BIM implementation, one of the most relevant aspects to consider is the standardization of information flows that occur between the different activities, disciplines, and phases of a process, as well as capturing the correct information within each information model [

1]. Standards are fundamental for communication between the various disciplines involved in projects, whether they are architects, engineers, contractors, specialists, or owners, who work with different nomenclatures, vocabularies, geometries, formats, and data schemas. Therefore, advancing standardization is a key factor in the adoption of BIM [

2].

Likewise, the development of BIM standards makes it possible to address the different interoperability challenges that occur within the workflows of this methodology. Interoperability is defined as the ability of diverse systems, organizations, and/or individuals to work together, using each other's parts or equipment, to achieve a common goal, regardless of their differences [

3]. In this way, when BIM systems are interoperable, the different project participants can share and generate information on the different progress and phases of the project [

3].

One of the standards defined within the BIM methodology is the Information Delivery Manual (IDM), which involves the identification and documentation of the processes and requirements for information exchanges [

4] within the processes. ISO 29481-1 is responsible for defining this standard, with the aim of providing a methodology to capture and specify the processes and information flows required during the asset lifecycle [

5]. Likewise, this regulation provides a reliable basis for the exchange of information between users, so that they can be sure that the information they are receiving is sufficient to carry out the activities within the process [

6].

In this way, having a standardized data model that considers the information requirements for each activity is essential to ensure that information exchanges are carried out in a better way, and with it the process and development of projects improves itself. Thus, in the context of the adoption of the BIM methodology within industrialized timber projects, one of the important challenges is to define the exchanges of information that occur between the different processes, one of these being the commercial evaluation process that occurs in early stages.

Cost estimation in the early stages is a crucial element in any construction project. An accurate estimate of the initial cost will support project decision-making, considering that the project cost is significantly affected by decisions made in the design phase [

7]. In this way, the commercial evaluation process in the early stages takes on great significance, particularly for industrialized timber projects. This process must consider not only the requirements of a traditional project but also the assumptions and requirements that the design entails and that are necessary for the industrialization, manufacturing, and assembly process.

Regarding the use of BIM in the timber industry, and in general in the construction industry, it has been based on the use of digital models that have made it possible to facilitate the different processes and activities within the development of projects, since through the use of information models it has been possible to coordinate the different specialties, improve the visualization of its components, analyze performance, facilitate the processes of cost estimates, assembly sequence, manufacturing, logistics, among others. [

8,

9].

Likewise, the timber industry has made progress in defining BIM standards, covering the required information exchanges, for example, for the design of timber structures, focusing on information exchanges between architects and engineers during the preliminary design phase of the project [

2]. Similarly, in the work of Rojas, et al. [

10] an MDI associated with the evaluation process of industrialized timber projects is proposed for the system based on light frame (2D) panels. This proposal identifies the different phases, actors and activities that are present within this process, where the approach was based on the exchange model (EM) required to carry out the evaluation of the project during the early phases. The following section presents other work, advances and research associated with the development of BIM standards within the industrialization and prefabrication process of timber projects.

Along these lines, it is possible to mention that, although there have been developments of standards that have sought to map the standardization of information flows between processes, the real impact of using these standards and thus valuing the effects and possible improvements (for example, increased efficiency) in the development of activities that are executed during the different phases of the project has not been evaluated.

In this way, the purpose of this research is to carry out a practical validation of the IDM proposal presented in the study by Rojas et al. [

10], in particular, to test the information exchange model (EM) required to support the early evaluation subprocess of industrialized timber projects, and thus evaluate the impact that the use of this standard has on the development of commercial evaluation that occurs in the early stages of the project.

This validation was carried out based on two illustrative cases ("case illustrations") of projects in which two users associated with industrializing companies participated, who made use of the exchange model (EM) proposed within the IDM to support the process of evaluating projects in early stages, in order to identify if this activity is more efficient when using a standardized data model.

2. State of the Art and Practice

2.1. BIM in Industrialized Construction

Building Information Modeling (BIM) has had a significant effect on the construction industry over the past decade [

11]. Various studies have shown the benefits of the application of BIM, such as: improvements in design, faster and more effective processes, for example, for cost estimates, energy simulations, monitoring of tasks on site, etc. [

12,

13].

Similarly, the implementation of the BIM methodology has also had a relevant impact on the industrialized construction sector. With the help of information-rich construction models and integration of data from different processes, BIM has provided the industry with great potential to promote the industrialization of construction, and even improve the performance of modular construction [

14].

For industrialized buildings, the use of BIM has made it possible to facilitate the development and exploration of the different design options in order to meet the client's requirements and to be able to customize the design of the project [

15]. Likewise, the research of Barkokebas, Al-hussein, & Manrique [

16] presents and supports a cost estimation methodology for industrialized (manufactured) residential building projects through the use of BIM-based 3D parametric modeling.

Likewise, the research of Patlakas, Menendez, & Hairstans [

9] describes different benefits of using the BIM methodology for industrialized construction, in particular for prefabricated timber projects, which were categorized into 5 groups: increased design flexibility, improved off-site production process, improved delivery and assembly process of elements, easier determination of structural performance, and improved environmental and sustainable performance.

However, despite the various uses of BIM in industrialized construction and the multiple benefits it brings, there are still various challenges that need to be addressed. Partly, this is because most existing BIM tools have been developed in response to traditional non-prefabricated buildings, which means they do not consider the factory production process and the transfer to the construction site for assembly [

17]. Accordingly, some functionalities related to the design of prefabricated buildings are incomplete in some existing BIM products. Therefore, there is a pressing need to enhance the current BIM technology to meet the requirements of prefabricated building design [

18].

Along the same lines, the research of He et al. [

15] establishes that the understanding and integration of the relationships between design, detailed modeling, and automation for manufacturing is still very limited. Even research such as that of Yin, Liu, Chen, & Al-hussein [

19] establishes the need to use BIM in order to be able to incorporate concepts such as Design for Manufacture and Assembly and achieve optimized designs for prefabricated projects.

Another challenge that arises in various research associated with the use of BIM and industrialized projects is based on the exchange of information between BIM tools and modern manufacturing systems that use computerized numerical control (CNC) machines, which have traditionally worked successfully with CAD/CAM software tools.

On this last point, the research of Patlakas et al. [

9] states that the specification of a technical standard is required that allows the accurate translation of any parametrically produced geometry into the appropriate CNC instructions. In addition, standard protocols for interoperability and data exchange between existing BIM applications and CAM/CNC systems would prove to be of great benefit to the industry [

9].

In relation to this, one of the lessons learned from the work of He, et al. [

15] establishes that an adequate exchange of information between BIM and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) systems is a fundamental need for the integrated design and prefabrication of industrialized buildings. Likewise, in this research it is proposed that future work addresses the exchange of information through BIM and open standards for the automation of the design and prefabrication of industrialized buildings, whose main focus is based on developing BIM interoperability standards that specify the different information requirements of each activity and achieve interoperability between BIM tools and CAM applications [

15].

Regarding the impact of BIM on the life cycle cost control of prefabricated buildings, Sun, et al. [

20] conclude that the use of this methodology has a positive effect on all phases of the project, being more significant in the construction and installation phases, followed by the production and transport phases. and finally in the design phase, in which the impact is less.

Along these lines, and taking a further step in improving the use of the BIM methodology in the off-site construction of timber projects, is the work published by Paskoff, et al. [

21] with the aim of establishing a testing model of the process of applying the BIM methodology for buildings designed with mass timber. To this end, a digital verification model called BIM-Based Model Checking (BMC) is defined.

Based on this background, and in accordance with the challenges posed on the use of BIM in prefabricated projects, it is of great relevance to examine the state of the art associated with the BIM standards that have been proposed for the off-site construction sector, in particular, this research will focus on prefabricated projects based on the system of light timber framing panels.

2.2. Proposed BIM Standards in Industrialized Timber Construction

Standardization within the BIM methodology has become necessary to achieve the exchange of information between the different software applications used in the construction industry [

22]. One of the main organizations that has taken charge of this is buildingSMART, which has developed the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) format, a standard and open comprehensive information model scheme for the construction industry whose objective is to take care of the exchanges of information between the different existing BIM applications [

23].

There are also other works related to standardization within BIM, for example: IDM (Information Delivery Manual) and MVD (Model View Definition), which are necessary to specify the requirements of data exchanges and relate them to the IFC file format. On the one hand, IDM is responsible for the identification and documentation of the processes and the requirements for information exchanges within them (in a human-readable format), and then, through the definition of an MVD, integrates these requirements into the more logical Model Views that would be developed and implemented in the different software applications [

11].

In particular, the progress in BIM standardization for the industrialized timber construction industry has been based on the proposal of different IDMs and MVDs that try to address the exchanges of information between different processes and tasks that are relevant in this sector. This section reviews the proposed standards for the off-site construction sector for timber buildings.

The work of Ramaji & Memari [

11] presents a method to standardize information exchanges in industrialized modular projects, developing an IDM based on the method proposed in the National BIM Standard (NBIMS-US) and incorporating the Product Architecture Model (PAM) concept whose purpose is to address the additional needs that exist in the development of modular buildings. The Product Architecture Model is defined as a way in which the functional elements of a product are assigned to the different physical components of the project and how they interact. In this context, the Product Architecture Model (PAM) is the key element combined in the method proposed by NBIMS to look at modular buildings from a production point of view and is used as the core for all standardization [

11].

On the other hand, the work of Nawari [

1] addresses the challenges and opportunities to advance BIM standards in off-site construction. In this research, an IDM is proposed that provides a concrete description of the off-site construction processes of buildings, and the information requirements that must be delivered to allow these projects to be carried out successfully. The proposal of this MDI incorporated exchanges of information between various actors involved: architects, engineers, manufacturers, general contractors, and other subcontractors [

1]. It is worth mentioning that these definitions of workflows are linked to a general process and do not delve into specific requirements for off-site construction for systems based on timber or other materials.

In order to further advance in the harmonization of standards in timber construction and framed in the Finnish project "projectGENERIC" and "Puurakentamisen suunnittelun automaatio", Keskisalo, M. et al. [

24] publishes a paper whose objective is to map the needs of companies in the object sector with BIM modeling with the aim of incorporating them into the BIM object library "Nordic BIM library" and serve as a basis for the harmonization of standards in the construction sector with mass timber.

Finally, as part of the project UF-DCP-002 Wood Structural Design to Structural Analysis [

25], an IDM and MVD standard for the design of timber structures is proposed. Under the context of this project is the research published by N. Nawari [

2], which reviews the state of BIM tools in the process of modeling timber structures and formulates the functional requirements for the development of successful BIM models for the design of timber structures. In particular, this research focused on the exchanges of information between architects and engineers during the preliminary design phase of the project [

2].

According to these works and research, it is possible to mention that the development and advances in BIM standardization within the off-site timber construction industry have been addressed and explored independently, on the one hand, it has focused on the development of the projects themselves and on the other, requirements and process mappings for off-site construction have been formulated. there is a need for the integration of both processes.

In an effort to unite both aspects, Rojas et al. [

10] analyze the IFC defined in the international standard ISO 16739-1:2018, which although it is replaced by ISO 16739-1:2024, this does not imply any change in the IFC object of said work, referring to building projects, having produced changes only in the inclusion of aspects related to linear and civil works. The work of Rojas et al. [

10] proposes a new exchange model in which a series of parameters are incorporated that are considered minimum to achieve an optimal implementation of the BIM methodology in industrialized construction projects with a timber frame structure.

For all the above and in order to continue improving the implementation of the BIM methodology in this type of projects, the objective of this work is to validate the MDI proposed in the research by Rojas, et al. [

10] through two illustrative cases, a particular case study for the EM-01 information exchange model (EM) associated with the early evaluation of timber projects, under the off-site construction system based on light lattice panels.

In order to cover the lack of proposals in the implementation of the BIM methodology, and specifically in the early evaluation phase of this type of projects, this work is developed. The objective is to carry out the validation through the study of two illustrative cases of the EM-01 exchange model proposed by Rojas et al. [

10] of information associated with the early evaluation of timber projects, under the off-site construction system based on light frame panels.

3. Methodology (Experimental Design)

The research is developed through the study of two illustrative cases of projects with similar characteristics in terms of volumetry and use and both designed with the construction typology object of this research: structure of light timber frame panels. The analysis method used for both cases in order to meet the objectives set is described in detail below.

3.1. Objective and Description of the Experiment

The objective of the experiment is to evaluate the impact of using an information exchange model to support the early evaluation process of prefabricated timber projects. To this end, the evaluation of the data exchange (MA) model proposed in the IDM of Rojas, et al. [

10] is carried out, more specifically the one defined as EM_01 specifically designed for early assessment. This exchange model requires information (Exchange requirements, ERs) related to the conceptual evaluation of the model in which the data exchanged refer to general architectural and geometric characteristics of the project, such as volumes, construction systems and cost estimates per square meter of panel. To do this, the model proposes a series of minimum parameters to be defined, geometric and non-geometric. This proposal incorporates new non-geometric parameters in relation to the provisions of the international standard ISO 16739-1:2018: IFC (parameters that have not been modified by ISO 16739-1:2024) with the aim of completing this standard and thus being able to carry out a more accurate early assessment through the use of BIM methodology.

In order to test the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed model EM_01 by Rojas et al. [

10], and therefore considering these new parameters, this paper compares the results obtained with respect to those derived from the application of the traditional method used by prefabrication companies in the early evaluation of their projects and those obtained by applying the EM_01 exchange model.

The experiment is divided into 2 phases, which are summarized in the following diagram.

Table 1.

Research methodology for the evaluation of the EM_01 model.

Table 1.

Research methodology for the evaluation of the EM_01 model.

| Objective |

Phases/Activities |

Method |

|

Assess the impact of using the EM_EEIW information exchange model to support the early evaluation process in timber industrialized projects.

|

Phase 1

Company A evaluates Project W using the information exchange model (method X)

Company B evaluates Project W using the traditional method (method Y) |

Charrette |

Phase 2

Company A evaluates Project Z using the traditional method (method Y)

Company B evaluates Project Z using the information exchange model (method X) |

According to this, the experiment is divided into 2 phases. The first phase consists of two companies carrying out the evaluation of the W project. In this phase, company A uses the EM_EEIWP exchange model, while company B uses the traditional method (method Y). Then, in phase 2, project Z is evaluated, in which company A uses the traditional method (method Y) and company B uses the exchange model (method X) to perform the evaluation. In this way, there is no bias between the methods, since different projects are evaluated using the two possible methodologies.

Likewise, for the two activities that exist within each phase of the experiment, the method used is based on a charrette formed by the evaluators of the companies participating in the experiment. This charrette is based on carrying out the evaluation process (quote) of each project, while the evaluator answers a questionnaire in which different questions are asked associated with obtaining the metrics of each variable that is tested in this experiment.

3.2. Experiment Variables

3.2.1. Independent Variables

The experimental design described above mainly involves two independent variables, which are described and detailed in the following table.

Table 2.

Description of independent variables.

Table 2.

Description of independent variables.

| Independent variables |

Description |

Types |

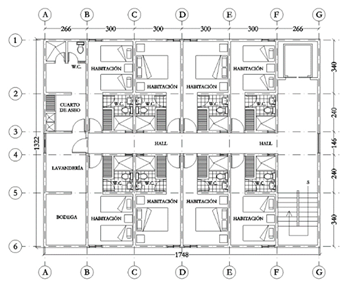

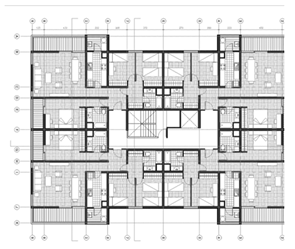

| Projects |

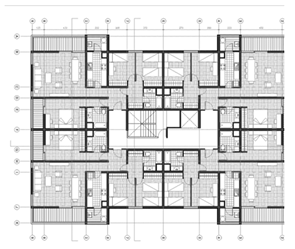

This variable represents the geometric and non-geometric characteristics and information that the project to be evaluated has. On the one hand, each project has a defined architecture, as well as different information parameters (non-graphic information) that are specific to each project and that have an impact on the design. The non-geometric parameters are: thermal regulations, region, commune, type of soil, seismic zone, type of grouping, number of floors, height of walls |

Project W |

Architecture associated with a 4-storey residential building. |

| Project Z |

Architecture of a 4-story residential building. |

| Evaluation methods |

This variable involves the types of methods that are used to evaluate projects. The objective is to be able to contrast the traditional method used by prefabricators to evaluate projects with respect to the EM-01 exchange model proposed by Rojas et al. [10] |

Method X: Exchange model |

This method consists of using the exchange model that contains different information parameters to carry out the early evaluation of the project. |

| Y-Method: Traditional |

This method is based on using information based on planimetry, documents or 2D information mainly, for users to carry out the evaluation of the project. |

3.2.2. Dependent Measured Variables to Assess the Impact of Using the EM_01 Model

In order to test and contrast the result of the early evaluation of the projects using both the exchange model and the traditional method, the purpose of this contrast is based on the measurement of different variables to evaluate whether the use of the data model (method X) generates benefits in the early evaluation process compared to the traditional method (method Y). To this end, during both phases of the experiment, the measurement of the metric variables associated with the different dependent variables of the experiment expressed in the following table will be carried out:

Table 3.

Description of measured variables.

Table 3.

Description of measured variables.

| Variable |

Description |

Testing |

| Effectiveness |

Feasibility of carrying out the project evaluation process with the information provided in the EM_01 exchange model |

Achievement of performing the assessment |

| Overall Assessment |

General perceptions about the advantages and challenges of the methods. |

Opinion of the evaluators regarding the use of both methods. |

| Efficiency |

Level of resources needed to carry out the project evaluation. |

Actual working time + client response times

Number of interactions required with the client |

| Level of certainty |

Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the level of certainty of each company at the time of carrying out the evaluation process |

Number of assumptions made during the evaluation

Perception of the evaluator according to scale |

Based on these variables, a questionnaire was created that was applied in the illustrative cases after the evaluation of the projects with the methods. The questionnaire was structured to conduct a guided interview with the users and collect information on the performance of each project according to the model applied.

4. Independent Variable Specifications

4.1. Projects to be Evaluated (Illustrative Cases)

Prior to testing the exchange model, it is important to mention that this model is generated through a digital platform, which was developed and implemented based on the information exchange proposal present in the IDM of Rojas, et al. [

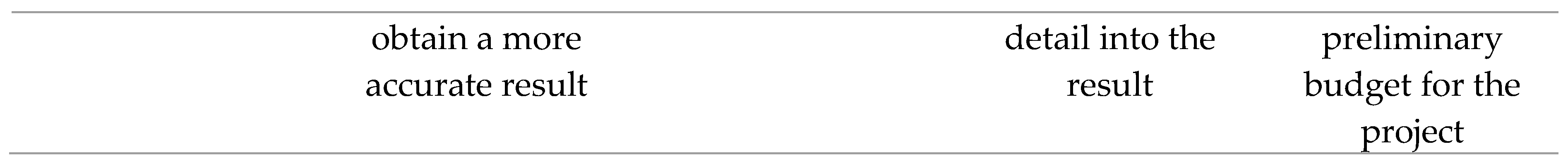

10]. This work was carried out in conjunction with an interdisciplinary research team, which worked on this platform so that different users could obtain a schematic design of the project they wish to evaluate. For this experiment, the information associated with the W and Z projects was entered into the platform, the result of which is the exchange model to be tested in this work. The following table shows the detail of the background of both projects.

Table 4.

Project background (Illustrative cases).

Table 4.

Project background (Illustrative cases).

| |

Project W |

Project Z |

| Architectural Plan |

|

|

| Thermal regulation |

Current thermal regulations |

Current thermal regulations |

| Region |

Santiago Metropolitan |

Santiago Metropolitan |

| Municipality |

Santiago |

Ñuñoa |

| Soil Type |

B |

B |

| Seismic Zone |

2 |

2 |

| Grouping Type |

Collective building |

Collective building |

| Number of storeys |

4 |

4 |

| First floor |

Grit |

Grit |

| Wall height |

2,4 m |

2,4 m |

4.2. Evaluation Methods

4.2.1. Model Exchange Method EM_01 (X)

The exchange model has different entities and parameters that allow the user to be given relevant information to support the project evaluation process in early stages.

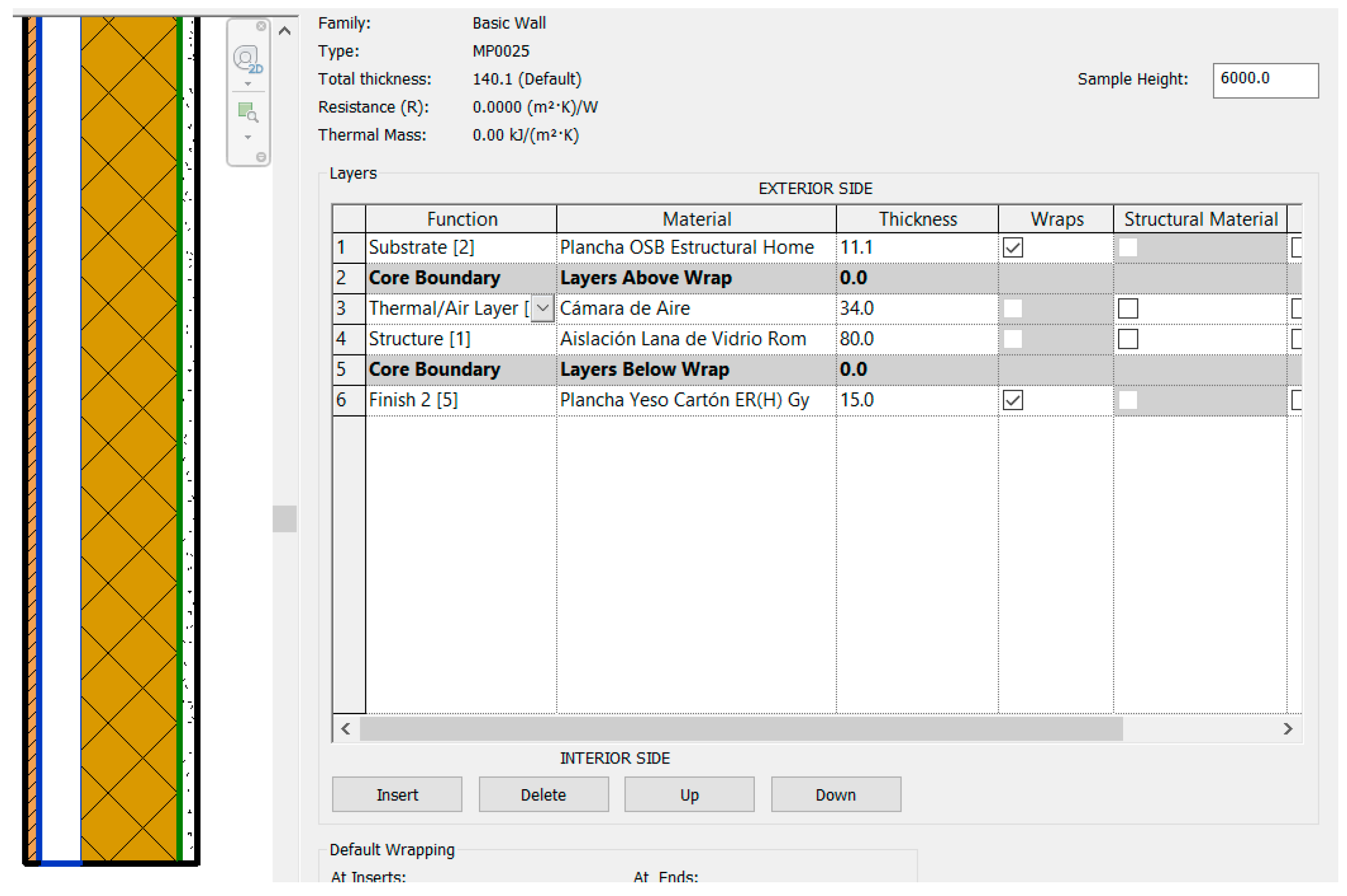

This exchange model defines parameters based on a minimum series of attributes that must be considered in this process. These parameters are classified as geometric and non-geometric. These parameters are classified as geometric and non-geometric. The geometric parameters refer to the dimensions of the panels that make up the volumetry of the project, mainly walls and floors (length, height and thickness of panels) and their location in relation to the floor level on which they are located. As non-geometric, the model defines a series of relevant parameters due to the impact that the different variables applied to them have on the final cost of the project. These parameters refer to the construction solutions adopted in which the materials that make up the panels and their configuration are defined, which allows the costs of materials and manufacturing processes to be evaluated more precisely. Within the non-geometric parameters, aspects are also defined that allow calculating production times and availability in the market of the materials that make up the panels and the means necessary for their manufacture.

The parameters considered in the model are reflected in

Table 5, classified as geometric and non-geometric and with a strong description of the relevance of their consideration in the exchange model for the improvement of accuracy in early assessment. The parameters listed in the table include the minimum information necessary for the application of the exchange model proposed and tested in this study.

Table 5.

EM-01 Exchange Model Parameters.

Table 5.

EM-01 Exchange Model Parameters.

| Parameter Type |

Parameters |

Description |

| Geometric |

Longitude |

Minimal geometric definition: prior knowledge of this parameter allows you to optimize production and logistics from transport to the site. |

| Thickness |

| High |

| Level |

The location of the panels by levels provides important information to establish in an orderly manner the supply and designation of storage areas for each of the elements that make up the structure. |

| Non-geometric |

Identification of the panel construction solution |

The definition of the construction typology allows us to know the materials that are going to be used in the manufacture of the panels, being able to estimate the costs and their availability in the market. |

| Weight |

It allows the design of a logistics plan for the transfer of panels on site, establishing the auxiliary means of lifting and moving to the plant that are necessary. |

| Specification of the type of anchors |

The cost of fasteners is significant, so this parameter is relevant to increase accuracy in early cost estimation. |

| Cost per square meter of panel |

It allows you to quantify the direct costs of the project. It also allows, by applying variations to the parameter, to obtain and compare total costs for the different variables. |

| Panel Type Identification |

It allows the identification and quantification of the panels that make up the project and allows for a more orderly management of these. |

| Identifying the type of table that makes up the panel |

The type of board and the configuration of the assemblies allow you to plan the production times and costs of the panels, being able to estimate the impact on the total cost more accurately. |

In order to be able to carry out the commercial evaluation process in early stages using the method based on the EM_EEIWP exchange model, the information provided to the evaluators of companies A and B (in phases 1 and 2) under this method is described in the following table:

Table 6.

Inputs and deliverables in evaluation method X (EM-01).

Table 6.

Inputs and deliverables in evaluation method X (EM-01).

| Input or deliverable |

Description |

1.-Summary sheet with background of the project and scope of the evaluation

|

Document that contains the non-geometric information associated with each project and scope of the evaluation. |

| 2.-Volumetric 3D model of the project |

Digital model in IFC and RVT format that has the entities of walls (vertical panels), mezzanines and ceilings (horizontal panels) of each project. Each of these entities has different information parameters that facilitate the early assessment process. |

| 3.-Technical sheets of construction solutions |

Document that shows information associated with the composition and acoustic, fire and thermal performance of the construction solutions proposed for the components of the project (walls and floors). |

| 4.-Tables with information parameters |

Summary table containing the information parameters of each entity (wall, mezzanine, ceiling) present in the 3D model. These tables are obtained directly from the 3D model through an export process, because they are parametric information contained in the entities of the 3D model. In addition, a brief description and explanation of the meaning of each parameter is provided. |

| 5.-Table with unit costs of materials |

Table containing the approximate unit costs (in UF/m2) of the materials present in light timber framing construction solutions (cladding, insulation, wood, etc.). |

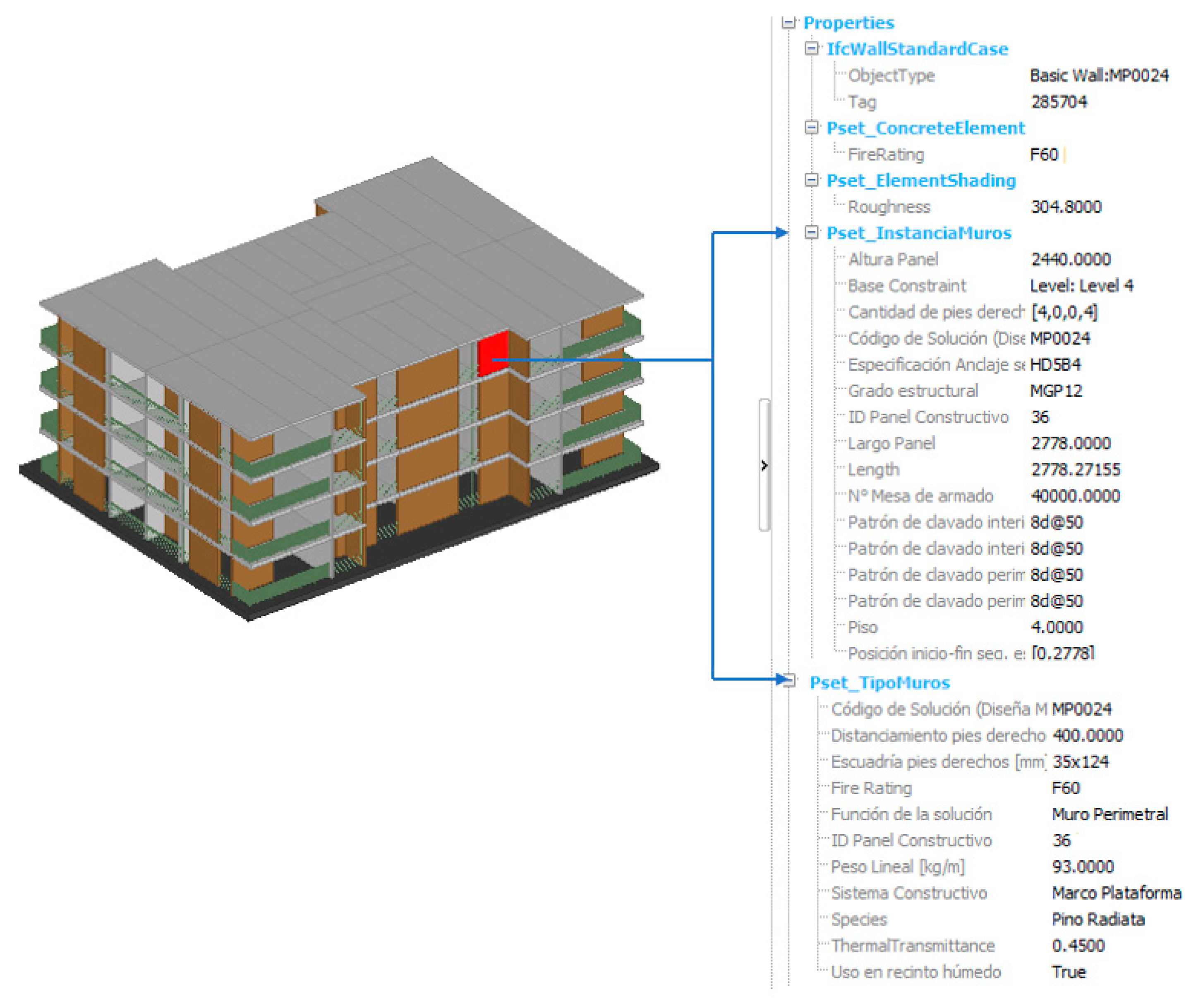

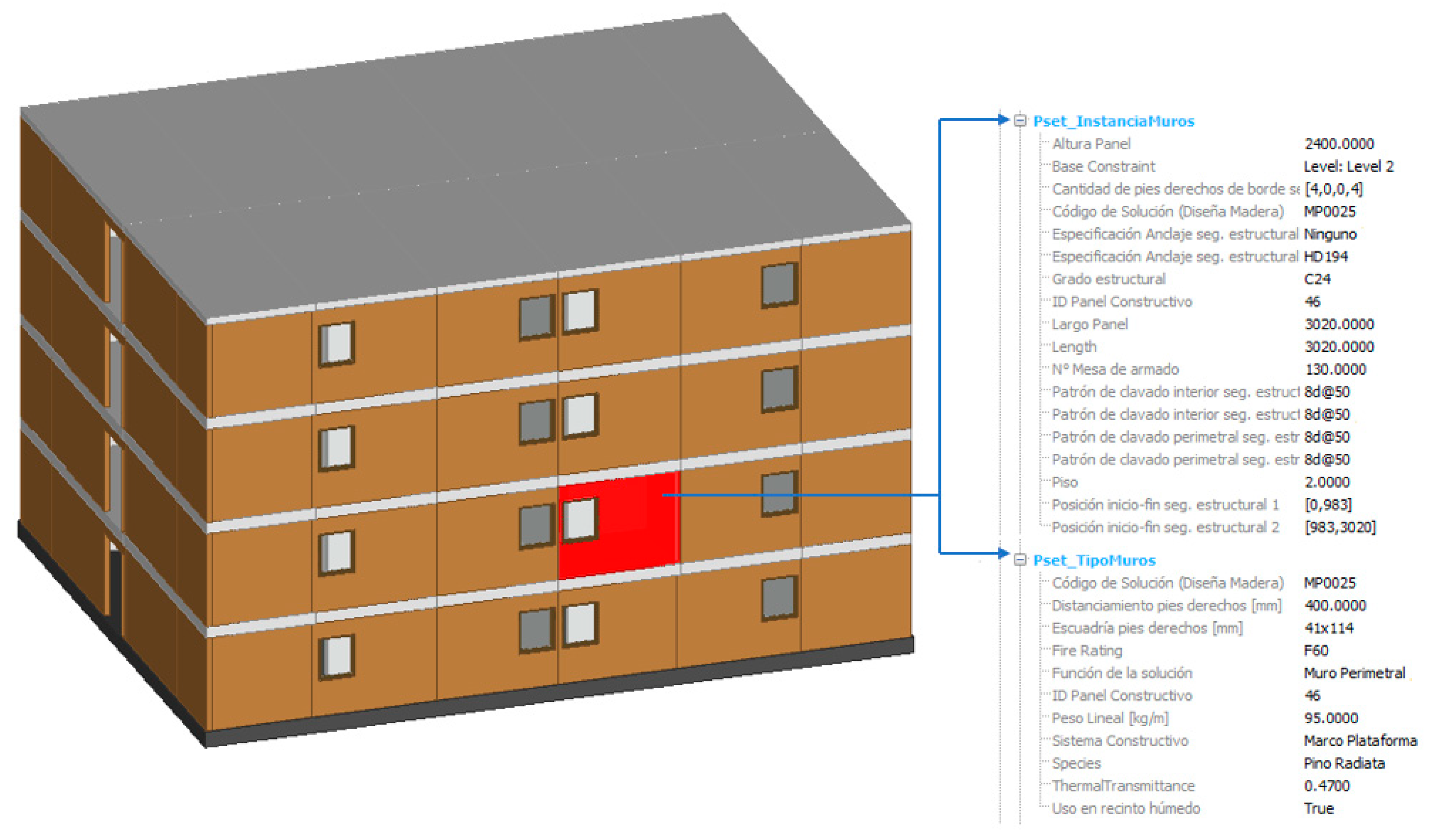

According to what is specified in table 5, the entities present in deliverable 2 (volumetric 3D model) associated with the wall, mezzanine and ceiling panels, have different parameters that allow the evaluator to provide relevant information to support the project evaluation process in early stages.

In addition to geometric information, each entity within the model contains either instance or type parametric information that complements the model data.

On the one hand, instance parameters are those that are unique to a particular element, i.e., they are unique values that belong to the element. On the other hand, type parameters apply to more than one element and are specific to the solution family. The following tables show the entities present in the model and their information parameters.

Table 7.

Wall entity information parameters.

Table 7.

Wall entity information parameters.

| Entity Wall |

Type Parameters |

Description |

|

Fire resistance |

Indicates the fire resistance property of the wall |

| Core wood species |

Indicates the species of wood in the core of the wall (studs and plates) |

| Thermal transmittance |

Indicates the thermal performance of the wall |

| Thermal transmittance |

Indicates the acoustic performance of the solution |

| Wet Room Use |

Indicates whether the wall solution can be used in wet rooms |

| Solution Code |

Enter a code to identify the solution |

| Studs spacing [mm] |

Indicates the distance of the studs inside the wall. |

| Studs dimensions [mm] |

Indicates the dimensions of the dimension of the studs |

| Función de la solución |

It indicates the function of the wall, whether it is: perimeter, interior or dividing |

| Linear Weight [kg/m] |

Indicates the weight per unit length of the solution |

| Construction System |

Indicates the construction system in which the solution is used |

| Instance parameters |

Description |

| ID Construction Panel |

Panel identifier or label |

| Manufacturing table number |

Number that identifies the table on which the panel will be built |

| Storey |

Indicates the floor on which the panel is located |

| Anchor Specification |

It corresponds to the specification of the anchorage obtained by each structural segment. |

| Anchor position |

It corresponds to the position where there are anchors within a panel, according to the structural segment belonging to the panel, in local coordinates |

| Number of end studs |

A number that indicates the number of edge studs that the structural segments will have within each panel |

| Inner nailing pattern of lateral structural segments |

Corresponds to the information on the nailing patterns of the structural plates (on their perimeter and inside) |

| Perimeter nailing pattern of lateral structural segments |

| Internal nailing pattern of gravitational structural segments |

| Perimeter nailing pattern of gravitational structural segments |

| Structural Grade |

Corresponds to the structural grade of the panel core |

| Start-end position structural segment |

(Local) coordinates that indicate where a structural segment begins and ends within the panel. |

Table 8.

Slab entity information parameters.

Table 8.

Slab entity information parameters.

| Slab Entity |

Type Parameters |

Description |

|

Core species |

Indicates the species of wood in the core of the slab (beams) |

Acoustic resistance

|

Indicates the acoustic performance of the solution |

Fire resistance

|

Indicates the fire resistance property of the wall |

Thermal transmittance

|

Indicates the thermal performance of the wall |

Weight per square meter [kg/m2]

|

Indicates the weight per unit area of the solution |

Construction system

|

Indicates the construction system in which the solution is used |

Wet Room Use

|

Indicates whether the wall solution can be used in wet rooms |

Solution Code

|

Enter a code to identify the solution |

Beam Spacing [mm]

|

Indicates the distance of the beams to the inside of the slab |

Beam dimension [mm]

|

Indicates the dimensions of the beam dimension |

Function of the solution

|

Indicates the function of the slab (or mezzanine) |

| Normalized Impact Sound Pressure Level [dB] |

Indicates the sound insulation information of the solution |

| Instance Parameters |

Description |

| ID Construction Panel |

Panel identifier or label |

| Assembly table number |

Number that identifies the table on which the panel will be built |

| Storey |

Indicates the storey on which the panel is located |

Structural Grade Wood

|

Corresponds to the structural grade of the panel core |

Likewise, the composition of each wall or slab solution is also stored in the type information, where the materials of each cladding of the element are identified, as can be seen in the following figure.

Figure 1.

Solution Composition Information (Wall Example).

Figure 1.

Solution Composition Information (Wall Example).

In order to comply with standardized information flows, the exchange models to be tested are delivered to users in IFC format, this, because prefabricators can use different software for their tasks and processes, in this way, the exchange model is delivered in an open source format, such as the IFC data model standard proposed by Building Smart [

26].

On the other hand, the information parameters contained in each entity presented in the previous section are contained within a specific Property Set that separates between the instance and type parameters for each entity, whether it is a wall or a slab. The following images show the interchange models corresponding to projects W and Z, with the information parameters contained in the Property Sets.

Figure 2.

Project W exchange model in IFC viewer.

Figure 2.

Project W exchange model in IFC viewer.

Figure 3.

Project Z Exchange Model in IFC Viewer.

Figure 3.

Project Z Exchange Model in IFC Viewer.

4.2.2. Traditional Method (Y)

Regarding the inputs and deliverables provided in the traditional method (Y) to carry out the early evaluation process, these are presented in the following table.

Table 9.

Inputs and deliverables in evaluation method Y (traditional).

Table 9.

Inputs and deliverables in evaluation method Y (traditional).

| Inputs or Deliverables |

Description |

| 1.- Summary sheet with background information on the project |

Document containing the non-geometric information associated with each project. |

| 2.- 2D planimetry |

Plans (cuts and elevations) in pdf and dwg format associated with the architecture of each project |

| 3.-Table with unit costs of materials |

Table containing the approximate unit costs (in UF/m2) of the materials present in light timber framing construction solutions (cladding, insulation, etc.) |

5. Results of the Evaluation of the Use of the EM_01 Exchange Model in the Early Evaluation Process of Industrialized Timber Projects

This section presents the results obtained from the experimental method described in section 3. The results are shown for the tested variables associated with the effectiveness, general evaluation, efficiency and level of uncertainty of the users when carrying out the commercial evaluation process of a timber building project, when using the traditional method (based on 2D information), and, on the other hand, when using the EM-01 information exchange model. The results presented in this section are based on the charrettes in which the evaluators of the participating companies participated at the time of carrying out the commercial evaluation process of the W and/or Z project. The graphs and conclusions presented below are obtained directly from these questionnaires.

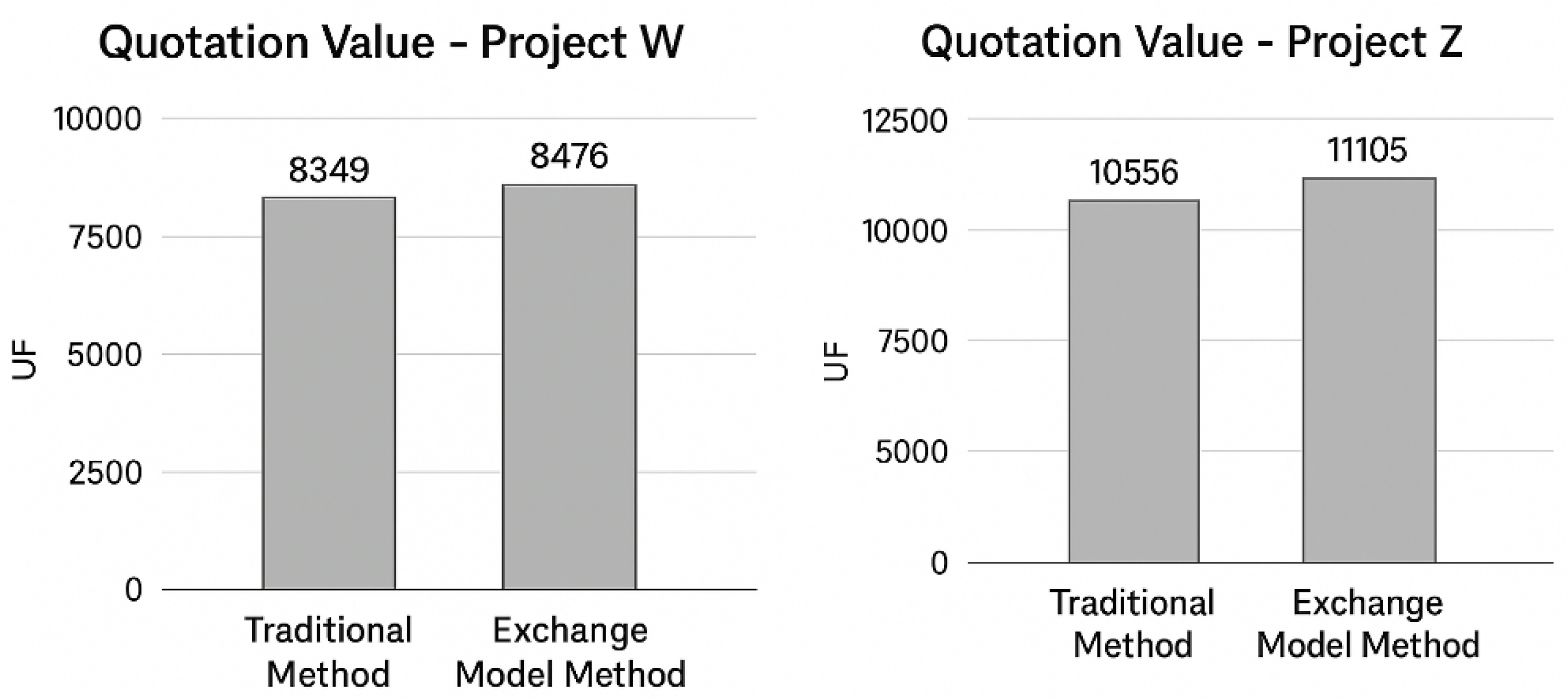

5.1. Effectiveness and Overall Evaluation

First, the results show that it is possible to carry out the commercial evaluation of the project by using either of the two methods, this implies that with both methods it is possible to obtain the value of a quote for the project in question, demonstrating the effectiveness of both methods. The following graphs show the comparison of the quotation values obtained by both methods for both project W and project Z.

According to the opinions of the evaluators, although the commercial evaluation process was possible using any of the methods, the use of the exchange model (method X) has certain advantages over the use of the traditional method. According to the evaluators, one of the main advantages of using the EM_01 model is that there is accurate information to ensure minimum values required for the evaluation, for example: square meters of solutions, type of solutions, acoustic and fire requirements, number of right feet, etc. Likewise, another advantage present in this method is that it considers a greater speed to carry out the calculations (for example, to obtain the total square meters of the building), where a subsequent verification is also not required. Similarly, the EM_01 model allows for more specific and detailed data regarding information associated with manufacturing, for example, the number of panels and configuration of assembly tables, which allows for a better estimation of the project's manufacturing times and costs.

On the other hand, the evaluators also commented on possible difficulties or disadvantages regarding the use of this model in contrast to the traditional method. These disadvantages are mainly based on the need for and use of more specific programs (software or applications), where an evaluator may not be familiar with the use of these tools. Also, when using the exchange model there is no room for iterations and it is not easy to compare with projects already executed. Finally, another disadvantage is that, in the event that the exchange model has an error, this would be very difficult to detect.

The following graphs show the comparison of the quotation values obtained by both methods for both project W and project Z.

Figure 4.

(left) Results of quotation values obtained by both methods in Project W; (right) Results of quotation values obtained by both methods in Project Z (Note: UF stands Chilean for non-circulating currency; 1UF=38.28 USD as April 2025).

Figure 4.

(left) Results of quotation values obtained by both methods in Project W; (right) Results of quotation values obtained by both methods in Project Z (Note: UF stands Chilean for non-circulating currency; 1UF=38.28 USD as April 2025).

According to graphs 1 and 2, it can be seen that, for both projects, the results of the quotation obtained using the exchange model method are higher than when using the traditional method. Although the difference does not exceed 5% in any of the projects, according to users, this is mainly due to the fact that the exchange model considers a more conservative structural result than the one considered in the traditional method.

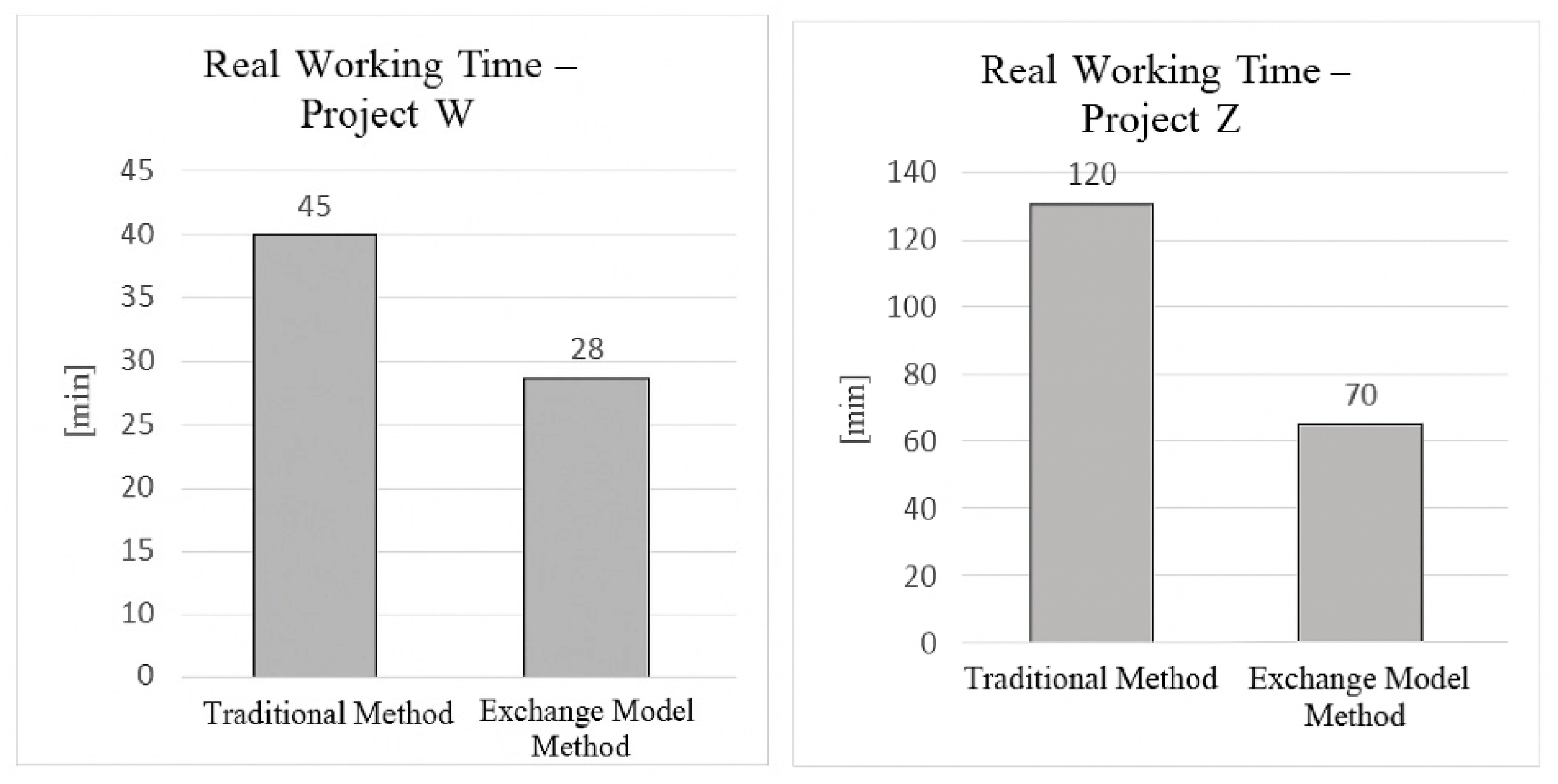

5.2. Efficiency

Graphs 3 and 4 show the result associated with the (actual) work times that users took to perform the project evaluation.

Figure 5.

(left) Result associated with the actual working time using both methods in Project W; (right) Result associated with the actual working time using both methods in Project Z.

Figure 5.

(left) Result associated with the actual working time using both methods in Project W; (right) Result associated with the actual working time using both methods in Project Z.

The results show that when using the information exchange model, work times are approximately 40% shorter than using the traditional method.

Regarding the response times of the client associated with queries made by the evaluator, in the case of user A, a query was made prior to the start of the experiment, associated with the scope of the evaluation, for this, the response time of the client was 1 day. Likewise, user B did not consult the client at the time of carrying out the evaluation. The following table shows the number of interactions made with the project client.

Table 10.

Number of interactions required with the client during the evaluation.

Table 10.

Number of interactions required with the client during the evaluation.

| |

Traditional method (Y) |

Exchange Model Method (X) |

| Project W |

0 |

1 |

| Project Z |

1 |

0 |

5.3. Level of Certainty

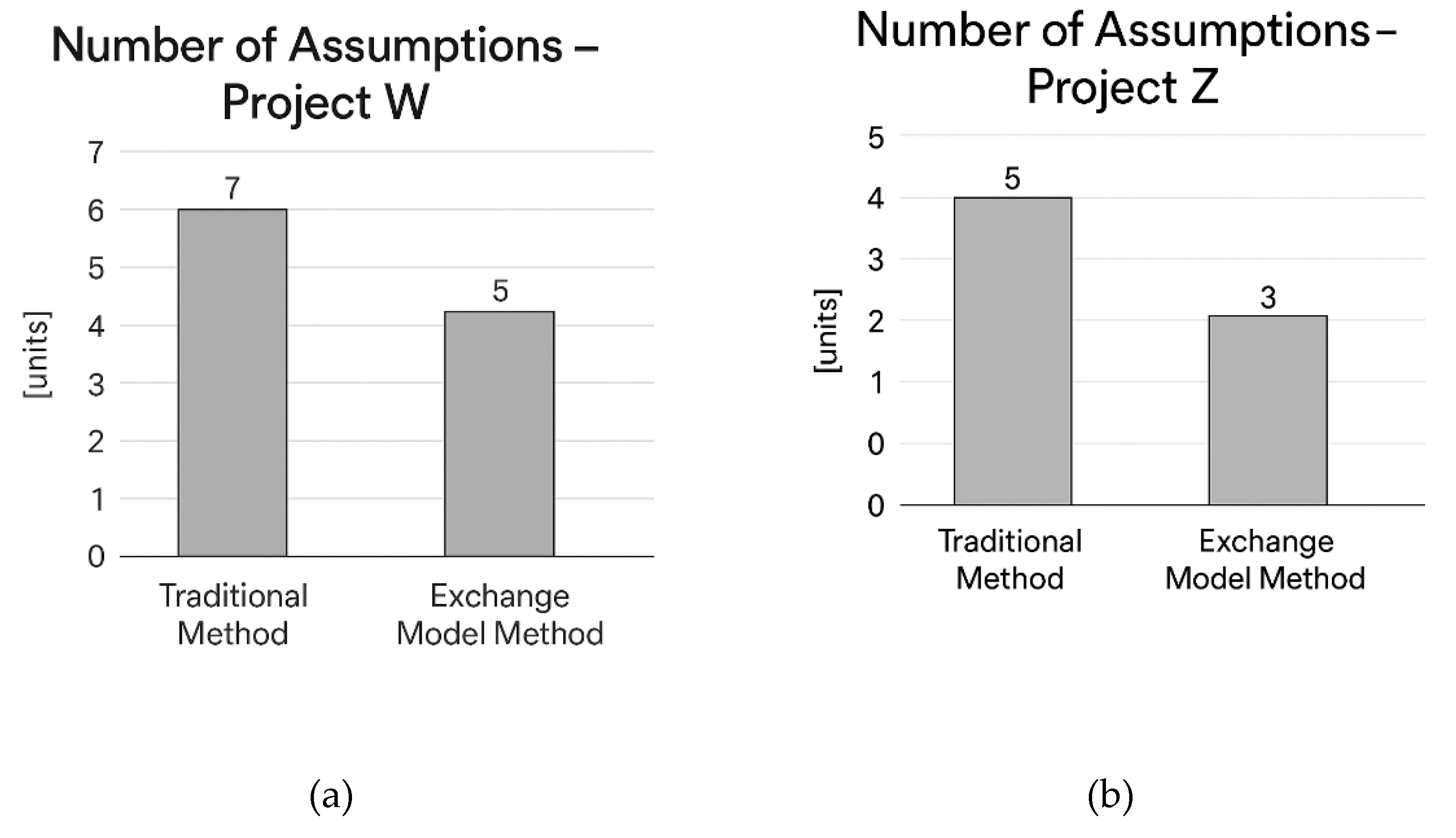

Finally, the evaluation process using both methods was tested with respect to the level of uncertainty of the user, according to the perception that was had during the process. For this, as a quantitative variable of this aspect, the number of assumptions made during the evaluation was counted. The following graphs show the results of this variable.

Figure 6.

(a) Number of assumptions made during the evaluation in Project W; (b) Number of assumptions made during the evaluation in Project Z.

Figure 6.

(a) Number of assumptions made during the evaluation in Project W; (b) Number of assumptions made during the evaluation in Project Z.

According to these results, through the quantitative analysis it was found that the exchange model for the evaluation process, in both projects, requires a smaller number of assumptions made compared to the traditional method.

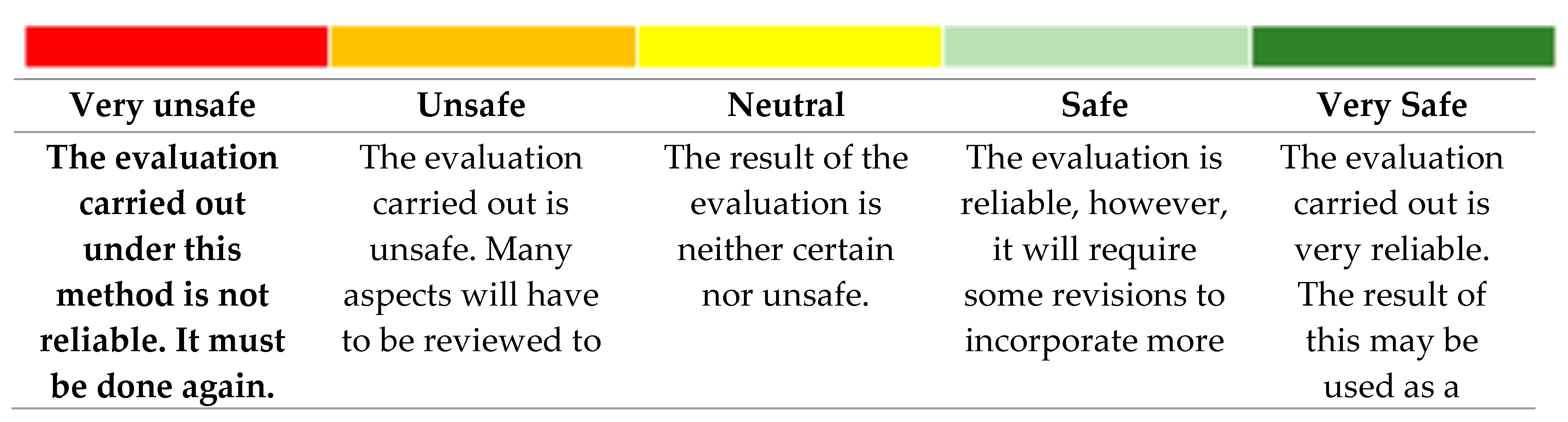

Likewise, in order to have a qualitative result of the level of uncertainty, users delivered their perception during the evaluation process by using either the traditional method (Y) or the exchange model (X). For this, it was tested based on the following perception scale.

Figure 7.

Assessment scale for level of uncertainty (evaluator's perception).

Figure 7.

Assessment scale for level of uncertainty (evaluator's perception).

The following table shows the result associated with the user's perception at the time of carrying out the commercial evaluation process of the project using both methods. According to the users' appreciation of the exchange model method, the commercial evaluation is safer than using the traditional method, and therefore this result can be used directly as a budget for the preliminary project.

Table 11.

Result of the user's level of certainty (evaluator's perception).

Table 11.

Result of the user's level of certainty (evaluator's perception).

| |

Traditional method (Y) |

Exchange Model Method (X) |

| Project W |

Safe |

Very Safe |

| Project Z |

Safe |

Very Safe |

6. Discussion

To validate the Em_01 information model proposed by Rojas et al. [

10], for the commercial evaluation in early stages of industrialized timber projects, the effectiveness, efficiency, and level of uncertainty were measured and its performance was compared with the traditional method.

First, the results of effectiveness; show that with both methods it is possible to carry out a commercial evaluation (or quote) of the project. However, the value of the quote obtained using method X (exchange model) turns out to be 1.5% higher in project W, and 4.9% higher in project Z, compared to the quote obtained using the traditional method (method Y).

According to users, this is mainly due to the fact that the exchange model provides more detailed information regarding the design of the building compared to the traditional method. Having more information reduces uncertainty in decision-making and therefore helps to have a more realistic approximation of the cost of the project in early stages. In addition, users stated that in the exchange model the results of structural verification are more conservative than those considered in the traditional method. For example, in the traditional method, a smaller spacing of straight feet and beams is considered, and also a smaller number of structural walls, and therefore fewer anchors, which results in a lower commercial evaluation based on this method than that of the exchange model.

On the other hand, the evaluation process with the exchange method turned out to be more efficient than the traditional method, obtaining less work time to make the project quote. According to users, this occurs because the identification of certain parameters and variables required to make the quote are very quick to identify and obtain based on a 3D model, versus, when using planimetry in the traditional method. In fact, users stated that many times the development of a 3D model to deliver a quote is necessary to be able to obtain values of the most accurate variables (for example, square meters of solution, openings, etc.) and to be able to iterate more quickly and efficiently with the client.

Regarding the interactions required with the client, the exchange model registered an interaction associated with the scope of the evaluation. While with the traditional model, the client did not require any interaction. Based on these results and user reviews. The number of interactions carried out with the client would not be related to the evaluation method used to carry out this process, but rather, they are associated with scope definitions and contractual issues of the evaluation, i.e., items to be executed, considerations within the evaluation (assembly, manufacturing), etc.

Finally, the level of uncertainty was tested quantitatively and qualitatively. Through the quantitative analysis, it was found that when using the exchange model, the number of assumptions made is lower than when the traditional method is used. According to users, using the method with the exchange model contains more information and specific to the structural design of the building compared to the traditional method. For example, the number of studs and their spacing, the number of panels and their configuration on manufacturing tables, m2 per type of solution, etc., which has an impact on fewer assumptions during the evaluation process. Another user said that it was not necessary to make the assumption of the number of structural walls per axis or the spacing of studs in vertical panels, nor the spacing of beams in mezzanines.

The qualitative analysis showed that by using the exchange model, the evaluator perceives a safer and more reliable process, and in both cases, this result could be used directly as a budget for the project in early stages. One of the users commented that by using the exchange model there is a "greater ease of calculating parameters that are considered within the evaluation, which makes the process more secure." Likewise, the user stated that nowadays the information that is sent to make the quote of a project in pre-design stages is very vague, (from a hand drawing, unclosed planimetry, etc.) which, in the same way, sometimes forces evaluating users to develop BIM models or 3D models, in order to be able to better visualize the definitions and conditions of the project. and, in the face of possible changes, iterate more securely with the client.

7. Conclusions

This research shows the impact of using an information exchange model to carry out the commercial evaluation process in the early stages of an industrialized timber building project. For this, two illustrative cases were applied based on two projects (Project W and Z) where the evaluation process was carried out using the traditional method, based on 2D information (planimetry), and using the method based on the information exchange model, which was proposed in the research of Rojas et al. [

10]. which considers various information parameters associated with the building's construction solutions.

The results of the illustrative cases show that the use of a standardized information exchange model to carry out the evaluation process of a project allows to increase the efficiency of the process in question, mainly reducing work times. It also reduces the uncertainty of the process, by having fewer assumptions and working with an information model that allows iterations or changes (if any) to be made more easily and safely. Similarly, according to the perception of users, they consider that by using the exchange model it is possible to obtain a more secure result of the quote, which can be used directly as a preliminary project budget.

The study presented in this document was limited to the commercial evaluation process of industrialized timber projects, using as a basis the proposal of the Information Delivery Manual (IDM) presented in the work of Rojas, et al. [

10]. It is proposed as future work to extend the illustrative cases presented in this case study to other sub-processes or tasks within the process of industrialization of timber projects, and thus identify not only a standardized data model that contains the information requirements for the different tasks, but also evaluate the impact that this has on the different tasks. being able to improve and make more efficient the sub-processes within the value chain of this type of project.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and P.G.; methodology, C.R.; validation, C.R., P.G. and C.M.; formal analysis, C.R.; investigation, C.R.; resources, C.R.; data curation, C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.; writing—review and editing, P.G, H.M., P.R., F.R., C.M.; visualization, C.R.; supervision, C.M and P.G.; project administration, C.M. and P.G.; funding acquisition, C.M. and P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Centro Nacional de Excelencia para la Industria de la Madera (CENAMAD ANID BASAL 210015).

Data Availability Statement

data will be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

Centro Nacional de Excelencia para la Industria de la Madera (CENAMAD) ANID BASAL FB210015.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nawari. (2012). BIM Standard in Off-Site Construction. Journal of Architectural Engineering, 18(June), 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Nawari, N. (2012). BIM Standardization and Wood Structures. Computing in Civil Engineering, 293–300. Retrieved from https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/9780784412343. 0037. [Google Scholar]

- Tchouanguem, D. , Karray, M., Kamsu, B., Magniot, C., & Henry, F. (2019). Interoperability Challenges in Building Information Modelling (BIM). Enterprise Interoperability VIII - Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Nawari, N. O., & Sgambelluri, M. (2010). The Role of National BIM Standard in Structural Design Nawari O. Nawari and Marcello Sgambelluri, 1660–1671.

- BuildingSMART International. (2021). Retrieved from https://technical.buildingsmart.org/standards/information-delivery-manual/.

- ISO. (2016). ISO 29481-1:2016(E) Building information models — Information delivery manual. Part 1: Methodology and format.

- Arafa, M. , & Alqedra, M. A. (2011). Early Stage Cost Estimation of Buildings Construction Projects using Artificial Neural Networks, (January). [CrossRef]

- Lu, N. (2018). Implementation of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Modular Construction: Benefits and Challenges, (May 2010). [CrossRef]

- Patlakas, P., Menendez, J., & Hairstans, R. (2015). The Potential, Requirements, and Limitations of BIM for Offsite Timber Construction. International Journal of 3D Information Modeling, 4(March), 54–70. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Mourgues, Guindos (Under review2023). IDM for the conceptual evaluation process of industrialized timber projects.

- Ramaji, I. J., & Memari, A. M. (2015). Information Exchange Standardization for BIM Application to Multi-Story Modular Residential Buildings, (April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. (2011). Building Information Modeling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 11, 241–252.

- Doumbouya, L. , Gao, G., & Guan, C. (2016). Adoption of the Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Construction Project Effectiveness: The Review of BIM Benefits, 4(3), 74–79.

- Zhang, J. , Long, Y., Lv, S., & Xiang, Y. (2016). BIM-enabled Modular and Industrialized Construction in China. Procedia Engineering, 145, 1456–1461. [CrossRef]

- He, R. , Li, M., Gan, V. J. L., & Ma, J. (2020). BIM-enabled computerized design and digital fabrication of industrialized buildings: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123505. [CrossRef]

- Barkokebas, B. , Al-hussein, M., & Manrique, J. D. (2015). Coordination of Cost Estimation for Industrialized Residential Projects Through the Use of BIM Coordination Of Cost Estimation For Industrialized Residential Projects Through The Use Of BIM, (15). 20 June. [CrossRef]

- Costa, G. , & Madrazo, L. (2015). Connecting building component catalogues with BIM models using semantic technologies: an application for precast concrete components. Automation in Construction, 57, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z. , Sun, C., & Wang, Y. (2018). Design for Manufacture and Assembly-oriented parametric design of prefabricated buildings. Automation in Construction, 88(16), 13–22. 20 April. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X. , Liu, H., Chen, Y., & Al-hussein, M. (2019). Building information modelling for off -site construction: Review and future directions. Automation in Construction, 101(January), 72–91. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. , Yi Man Li, R., & Deeprasert, J. (2024). The Impact of BIM Technology on the Lifecycle Cost Control of Prefabricated Buildings: Evidence from China. Buildings, 14(12), 3709.

- Paskoff, C. , Boton, C., & Blanchet, P. (2023). BIM-based checking method for the mass timber industry. Buildings, 13(6), 1474.

- Poljanšek, M. (2019). Building Information Modelling (BIM) standardization. Joint Reserach Centre - European Commission’s Science, (18). 20 January. [CrossRef]

- BuildingSMART International. (2012). An Integrated Process for Delivering IFC Based Data Exchange.

- Keskisalo, M. , Luukkonen, J., & Virtanen, J. (2022). BIM–object harmonization for timber construction. Wood Material Science & Engineering, 17(4), 274-282.

- BLIS Consortium and Digital Alchemy. (2021). IFC Solutions Factory - The Model View Definition Site. Retrieved from https://www.blis-project.org/IAI-MVD/.

- BuildingSMART. (2020). Industry Foundation Classes (IFC). Retrieved from https://www.buildingsmart.org/standards/bsi-standards/industry-foundation-classes/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).