1. Introduction

Amid the global shift toward digital transformation, the financial sector is undergoing unprecedented changes. Leveraging advanced technologies, including big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and digital finance, has reshaped the financial service system and profoundly impacted corporate financing models and economic behavior. Meanwhile, shadow banking activities among non-financial firms have become increasingly prominent, attracting considerable attention from academia and policymakers. Against the backdrop of global efforts to combat climate change and promote sustainable development, environmental regulation has emerged as a key policy tool for balancing economic growth and ecological protection. It influences corporate financing decisions and may significantly impact the relationship between digital finance and corporate shadow banking activities. Therefore, understanding the mechanism through which the coordinated development of digital finance affects the shadow banking activities of non-financial firms under environmental regulation is of theoretical and practical significance.

Digital finance has become a focal point in academic research in recent years. A substantial body of literature has explored its effects on corporate innovation, total factor productivity, and financing behavior. Studies suggest that the development of digital finance can significantly promote corporate technological innovation by enhancing profitability, reducing borrowing costs, optimizing financing structures, and mitigating financial mismatches (Xie and Zhu, 2021) [

1]. Additionally, digital finance reduces information asymmetry, improves the efficiency of credit resource allocation, and further enhances corporate total factor productivity (Jiang and Jiang, 2021) [

2]. The widespread adoption of digital finance has also accelerated the transformation of financial institutions' operating models. By leveraging intelligent risk management and big data analysis, digital finance optimizes capital allocation, reduces financial service costs (Dermertzis et al., 2018; Lu, 2018) [

3,

4], improves financing structures, enhances the efficiency of financial institutions, and broadens financing channels (Lin et al., 2021) [

5]. However, some studies argue that digital finance may face limitations in alleviating corporate financing constraints due to technological gaps (Gomber et al., 2018) [

6].

While research on digital finance is abundant, studies on the shadow banking activities of non-financial firms have primarily focused on its economic consequences and influencing factors. On the financial front, factors such as market monopolies, unequal financing access, and financial resource misallocation drive certain firms toward excessive borrowing, with surplus funds often directed toward shadow banking activities. This phenomenon is particularly evident in regions with higher economic development but lower levels of market-based resource allocation, notably among zombie firms, underperforming firms, state-owned firms, and companies with low growth potential (Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015) [

7,

8]. Furthermore, corporate financing structures are positively correlated with shadow banking activities. Firms with extensive supply chain networks and greater access to upstream and downstream information are likelier to engage in shadow banking. From a corporate governance perspective, dispersed ownership structures may increase coordination costs and weaken executive oversight, thus encouraging shadow banking activities (Huang and Jia, 2023) [

9]. Conversely, founders with substantial control rights may suppress shadow banking activities by reducing corporate risk tolerance. On the macroeconomic level, capital market openness enhances corporate transparency and strengthens external governance, thereby curbing shadow banking activities (Huang and Yao, 2021) [

10]. However, financial resource misallocation can exacerbate firms' motivation to engage in shadow banking (Han and Li, 2020; Bai et al., 2022) [

11,

12].

In the context of digital finance, the key indicator for measuring its coordinated progress is the level of coordinated development of digital finance, encompassing coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitalization degree. Unlike traditional financial systems, digital finance transcends spatial and temporal constraints, offering firms more diverse financing channels. However, the existing literature does not agree on the relationship between digital finance and corporate shadow banking activities. Some studies suggest that in the early stages of digital finance development, improved access to formal credit reduces firms' reliance on shadow banking financing (Fu and Huang, 2018) [

13]. Yet, as digital finance continues to advance, firms may increasingly exploit the flexibility and innovation of digital finance for regulatory arbitrage, engaging in shadow banking activities (Gong et al., 2014) [

14]. Under loose financial regulation, companies may utilize digital financial platforms for activities such as asset securitization to achieve greater financial leverage. Consequently, the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on corporate shadow banking activities may exhibit complex, nonlinear dynamics rather than a simple linear relationship.

This study makes the following marginal contributions: First, it constructs an index of the coordinated development of digital finance. By integrating three secondary indicators—coverage breadth, usage depth, and the digitalization degree of inclusive finance—and applying a coupling coordination model, this study provides a comprehensive measure of the coordinated development level of digital finance, offering a novel quantitative tool and analytical perspective for related research. Second, it analyzes the impact of digital finance on corporate shadow banking activities from a heterogeneous perspective. This study further examines the role of financing constraints, ownership structure, and marketization level in the underlying mechanism, aiming to uncover the distinctive financial behaviors of different types of firms. Third, it reveals the complex relationship between digital finance, environmental regulation, and corporate shadow banking activities. By establishing a unified analytical framework, this study investigates the "U-shaped" relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and corporate shadow banking activities and examines the moderating effect of environmental regulation. The findings offer valuable policy insights for financial regulators in formulating differentiated regulatory policies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 constructs the theoretical framework and proposes research hypotheses.

Section 3 introduces the data sources, model specifications, and variable measurement methods.

Section 4 reports the baseline regression results, robustness tests and heterogeneity analysis from the perspectives of financing constraints, ownership structure, and geographical location.

Section 5 further explores the "U-shaped" relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and corporate shadow banking activities and the moderating role of environmental regulation.

Section 6 summarizes the research conclusions and proposes policy recommendations.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Coordinated Development of Digital Finance and Its Promotion of Shadow Banking Activities Among Non-Financial Firms

The coordinated development of digital finance measures the extent of its balanced progress across multiple dimensions, including coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitalization level, aiming to establish an efficient and interconnected financial ecosystem. By leveraging advanced technologies such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence, digital finance fundamentally overcomes traditional financial services' time and space limitations. It significantly enhances the accessibility and allocation efficiency of financial resources, providing non-financial firms with more diversified and convenient financing channels. In the context of ongoing financial repression, credit constraints, and financing discrimination, some non-financial firms may engage in shadow banking activities driven by regulatory arbitrage motives, taking advantage of the flexibility and innovation of digital finance to meet their financing needs and pursue excess returns (Gong et al., 2014) [

14]. In this process, the level of coordinated development of digital finance is critical in influencing corporate shadow banking activities.

First, from the perspective of coverage breadth, digital finance leverages the openness and convenience of the Internet to lower the barriers to financial service access, expanding financial service coverage and providing small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) with more diverse financing channels (Xie et al., 2015) [

15]. Research has shown a significant positive correlation between the wide coverage of digital finance and the financing accessibility of micro and small firms, indicating its role in alleviating corporate financing difficulties (Guo et al., 2020) [

16]. Therefore, in regions with a higher level of coordinated development of digital finance, the synergistic effect of expanded coverage will become more pronounced, facilitating non-financial firms in obtaining stable sources of funding, which may accelerate shadow banking activities.

Second, from the perspective of usage depth, the continuous innovation of digital financial products and services enables firms to select from various financing options, including supply chain finance, online lending, and intelligent wealth management, based on their operational characteristics, funding needs, and risk tolerance. Studies have shown that in supply chain finance, digital finance can accurately assess credit risk and optimize capital allocation by leveraging real transaction data, thereby promoting industrial chain collaboration (Gu and Yang, 2018) [

17]. When the coordinated development of digital finance is at a higher level, its usage depth synergizes with coverage breadth and digitalization level to optimize financial resource allocation and meet firms' diverse financing demands. However, this financing convenience may encourage firms to expand their shadow banking activities further to secure additional funds in certain situations.

Finally, from the perspective of the digitalization level, digital finance has achieved substantial progress through technologies such as big data, blockchain, and artificial intelligence. The advancement of digitalization enables digital finance to conduct more precise credit risk assessments, reducing information asymmetry (Guo et al., 2020) [

16]. For example, blockchain technology ensures transparency and immutability of transaction information, fostering trust between parties and reducing credit risk (Yao, 2018) [

18]. Additionally, artificial intelligence algorithms can conduct in-depth analyses of massive datasets, providing firms with customized financial services. During the coordinated development of digital finance, digitalization enhances the innovation of financial products and services, enabling firms to utilize digital financial advantages to engage in shadow banking activities for additional funding.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1(H1). Coordinated development of digital finance significantly promotes shadow banking activities among non-financial firms.

2.2. The "U-Shaped" Relationship Between the Coordinated Development of Digital Finance and Shadow Banking Activities

In the early stages of digital finance development, the coordinated development level is mainly reflected in the rapid expansion of coverage breadth and usage depth. By utilizing advanced digital technologies such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence, digital finance significantly reduces information asymmetry and financing costs (Lu, 2018) [

4]. On the one hand, digital finance enhances information matching efficiency between fund suppliers and demanders, making it easier for firms to access formal financing channels, thereby reducing their reliance on shadow banking. On the other hand, compared to traditional financial institutions, digital finance strengthens data collection and analysis capabilities, lowering financing costs and reducing credit risks for financial institutions (Xie et al., 2018) [

19].

Additionally, digital finance complements traditional financial services through innovative platforms, providing cost-effective, fast, and inclusive financial services that lower entry barriers and reduce service costs (Huang and Huang, 2018) [

20]. During this phase, digital finance's formal financial services partially replace the functions of shadow banking (He and Miao, 2015) [

21], increasing corporate access to formal credit (Fu and Huang, 2018) and reducing corporate reliance on shadow banking. Therefore, at this initial stage, the coordinated development of digital finance generally suppresses shadow banking activities.

However, as digital finance continues to develop, the complexity of the financial market and innovation increase. Small and medium-sized digital financial platforms, due to their short development history, often lack advanced technological capabilities, mature operational models, and robust risk management mechanisms. It results in persistent information asymmetry, limiting their effectiveness in alleviating corporate financing constraints and prompting some firms to seek funding from shadow banking (Gomber et al., 2018) [

22].

Moreover, the rapid innovation of digital financial services often outpaces regulatory frameworks, providing firms with opportunities for regulatory arbitrage. Many financial innovations are closely linked to shadow banking systems, further encouraging corporate engagement in shadow banking activities (Buchak et al., 2018) [

23]. In China, since 2013, the proliferation of Internet lending platforms has played a significant role in addressing the financing challenges of SMEs and promoting financial inclusion. However, the lag in financial regulation has transformed "Internet + Finance" into a tool for regulatory arbitrage and disorderly expansion, leading to excessive risk-taking and even Ponzi schemes. This deviation from the original purpose of financial inclusion has intensified corporate financing constraints, increasing reliance on shadow banking funds (Zhu et al., 2018) [

24].

During this phase, market complexity increases significantly with continuous advancements in digitalization and frequent financial product innovations. Unlike the initial phase, the interaction of various dimensions alters the overall effect, causing the impact of coordinated development of digital finance on corporate shadow banking activities to shift from suppression to promotion, forming a "U-shaped" relationship.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2(H2). A "U-shaped" nonlinear relationship exists between the coordinated development of digital finance and shadow banking activities among non-financial firms.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Environmental Regulation

Environmental issues have become a focal point in global efforts to address climate change and promote sustainable development (IPCC, 2021). Governments implement environmental regulations to regulate corporate ecological behavior, promote resource efficiency, and drive green industrial transformation (Porter & Kramer, 2006) [

25]. Environmental regulation significantly alters corporate operational costs and revenue structures, influencing strategic decisions, particularly in financing. With the increasing importance of digital finance, understanding how ecological regulation moderates the relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and shadow banking activities is of theoretical and practical significance.

Under low environmental regulation, compliance costs remain low, and environmental protection requirements exert minimal constraints on corporate activities. In this scenario, firms may prefer shadow banking for financing polluting projects due to its lower cost and lenient oversight (Zhang et al., 2011) [

26]. Shadow banking institutions often impose weaker environmental risk assessments, making it easier for firms to obtain financing (Wang et al., 2019) [

27]. Enhanced digital finance coordination may further amplify this effect, accelerating shadow banking activities.

Under high environmental regulation, stricter ecological policies compel firms to adopt green technologies, fulfil their environmental responsibilities, and shift towards sustainable practices (Chakraborty & Chatterjee, 2017) [

28]. Digital finance, particularly in the form of green finance innovations, promotes the availability of environmentally friendly loans and green investment options. Consequently, firms are more likely to rely on formal financial channels than shadow banking. It reduces digital finance's "U-shaped" effect on shadow banking activities.

Based on this analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a(H3a). Under low environmental regulation, increased regulation strengthens the positive effect of coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities while weakening its nonlinear effect.

Hypothesis 3b(H3b). Under high environmental regulation, the "U-shaped" effect of coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities becomes less pronounced.

3. Methods

3.1. Models

3.1.1. Baseline Regression Model

To explore the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities of non-financial firms, the following baseline regression model is established:

Where i represents the firm, t represents the year, and j represents the industry. is the dependent variable, measuring the level of shadow banking activities of firm i in year t. is the key independent variable representing the coordinated development of digital finance. A set of control variables, denoted as Controls, is included to control for other factors that may affect corporate shadow banking activities. The model incorporates year and industry-fixed effects to eliminate the influence of time trends and industry differences, with year-fixed effects represented by and industry-fixed effects represented by . The term represents the random error term in the model. The coefficient of primary interest captures the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on corporate shadow banking activities. A significantly positive indicates that the coordinated development of digital finance promotes corporate shadow banking activities while a significantly negative suggests that it inhibits corporate shadow banking activities.

3.1.2. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Model

A quasi-natural experiment is constructed using a DID model to investigate further the effect of coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities of non-financial firms. Firms are categorized into treatment and control groups based on ownership type, with private firms as the treatment group and state-owned firms as the control group. The DID model is specified as follows:

Where Post is a time dummy variable, equal to 0 for years before 2015 and 1 for years from 2015 onwards. Treatment is a group dummy variable, equal to 1 for private firms (treatment group) and 0 for state-owned firms (control group). Post×Treat is the interaction term representing the DID effect. If is significantly positive, it indicates that private firms exhibit a tremendous increase in shadow banking activities compared to state-owned firms after the policy implementation.

3.1.3. Parallel Trend Test Using Dynamic DID Model

To test the parallel trend assumption and verify whether there were significant differences between the treatment and control groups before the policy implementation, this study constructs a dynamic Difference-in-Differences (DID) model, as specified in Equation (3):

Where Before is a dummy variable representing the years before the event (taking a value of 1 before the event year and 0 otherwise), and After is a dummy variable representing the years after the event (taking a value of 1 after the event year and 0 otherwise). If is not statistically significant and is significantly positive, it indicates no significant differences in corporate shadow banking activities between the control group and the treatment group before the policy implementation, while a significant difference emerged after the policy implementation. It would satisfy the parallel trend assumption of the DID model.

3.1.4. Nonlinear Effect Model

To explore the nonlinear impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on corporate shadow banking activities, this study constructs the model as shown in Equation (4):

Where CDDF2 represents the quadratic term of the coordinated development of digital finance, captures the nonlinear effect.A significantly positive indicates a "U-shaped" relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and shadow banking activities.

3.1.5. Model with Environmental Regulation as a Moderator

To further explore the moderating effect of environmental regulation on the relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and shadow banking activities, the following interaction model is established:

Where Er represents the level of environmental regulation, CDDF×Er captures the interaction effect between the coordinated development of digital finance and environmental regulation, and CDDF2×Er captures the interaction effect between the squared term of the coordinated development of digital finance and environmental regulation.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

This paper selects sample data from listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen between 2012 and 2022 and the Digital Inclusive Finance Index developed by the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center for the study. Data related to the selected sample companies is obtained from CSMAR, while data on the development of digital finance comes from research reports disclosed by the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center. The sample screening and processing work is conducted following these steps: First, exclude data from companies in the financial and insurance industries, as the characteristics of this industry differ from the study's focus and could interfere with the generalizability of the results; secondly Remove observations with missing key variables to ensure data integrity and avoid analysis bias caused by missing critical information; thirdly to reduce the interference of extreme values, all continuous variables undergo a Winsorization treatment at the 1% and 99% levels, making the data distribution more reasonable. After excluding ST, *ST, and PT companies, a final sample of 31,904 unbalanced panel observations is obtained for further analysis.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

This paper uses the Digital Inclusive Finance Index from the Peking University Digital Finance Research Center to assess the level of digital finance development. The index includes three sub-indices: the breadth of digital finance coverage, the depth of use, and the degree of digitalization of inclusive finance. These sub-indices reflect the extent of digital finance's reach across geographical areas and user groups, the depth of user participation in activities, and the characteristics of financial services' digital transformation. This paper uses a coupling coordination model to calculate the coordinated development of digital finance. First, the range of the three sub-indicators is standardized to eliminate unit differences. Then, the CRITIC weighting method is used to calculate weights by considering the variability and correlation of the variables. Next, the coupling degree between variables is computed based on the coupling model, and the weighted sum is used to obtain the coordination index reflecting the overall digital finance level. Finally, the coupling coordination degree is obtained by multiplying the coupling degree and coordination index and taking the square root, providing a comprehensive measure of the coordinated development level of digital finance.

3.2.2. Independent Variables

Referring to the studies of Li Jianjun and Han Xun (2019) and Si Dengkui et al. (2021), this paper defines the scale of shadow banking as the sum of entrusted loans, entrusted wealth management, and private lending and takes the natural logarithm of this sum [

29,

30]. The entrusted loan data is manually retrieved from announcements of entrusted loans published by A-shares listed companies in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges and organized based on the content of these announcements. The entrusted wealth management data comes from the China Foreign Investment sub-database of the CSMAR database. For private lending, the "other receivables" account is used as a proxy to measure inter-company capital outflows, and this data is sourced from the CSMAR database's listed company balance sheets.

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

This paper follows the methods used by Chen et al. (2016) and Chen Shiyi and Chen Dengke (2018) by using the frequency of "environmental protection" related terms appearing in local government work reports as a proportion of the total number of words in the report, as a proxy for environmental regulation [

31,

32]. This method effectively reflects the strength of the government's ecological governance efforts. Since local government work reports are typically published early in the year while economic activities continue throughout the year (Chen Shiyi and Chen Dengke, 2018), it helps mitigate endogeneity issues.

3.2.4. Control Variables

The control variables involved in this study and their measurement methods are explained as follows: Firm Age (Age): The difference between the natural year and the year of establishment is used; Firm Size (Size): The natural logarithm of total assets plus one is used; Leverage Ratio (Lev): The ratio of total liabilities to total assets is used; Cash-to-Assets Ratio (Cash): The ratio of cash assets to total assets is used; Return on Assets (Roa): The ratio of net profit to average total assets is used; Firm Growth (TobinQ): The ratio of stock market value plus total liabilities to total assets is used; Duality (Dual): When the chairman and CEO are the same person, the value is 1. Otherwise, it is 0; Board Size (Board): The natural logarithm of the number of board members is used. The definitions of the main variables are shown in

Table 1.

4. Results

4.1. Main Effects

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. It is observed that non-financial firms are generally involved in shadow banking activities, but the extent of their involvement varies significantly. It provides a foundation for examining the factors influencing shadow banking activities in non-financial firms. It is worth noting that shadow banking activities such as entrusted loans and entrusted wealth management are often off-balance-sheet items, which need to be obtained through relevant announcements or report footnotes. The data collection process is cumbersome and may be affected by the extent of information disclosure by firms, leading to potential fluctuations in the degree of shadow banking activities among different companies due to limitations in data availability.

From the perspective of coordinated development of digital finance, the maximum value of the coupling coordination degree is 1.00, the minimum value is 0.00, and the mean is 0.6703. It indicates that the development level of digital finance in non-financial firms is uneven, with most firms falling into a relatively concentrated range near the mean. The overall level of coordination is moderately high but with relatively low variability.

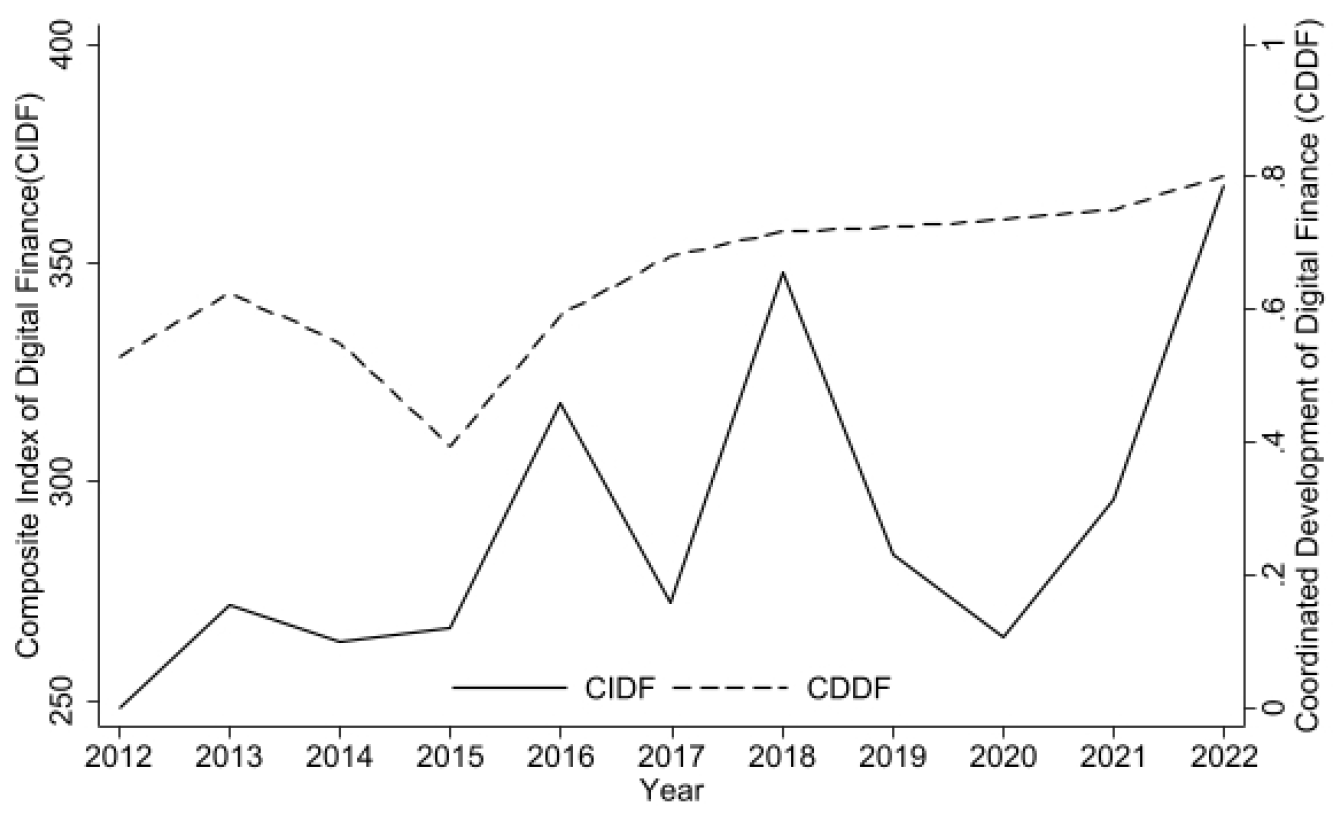

Figure 1 shows the annual changes in the comprehensive index of digital finance and coordinated development of digital finance from 2012 to 2022. The figure shows that the coordinated development of digital finance fluctuated and declined between 2012 and 2015 but began to rise steadily after 2015, reaching a higher level in 2022, indicating that the synergy between related systems or elements has continuously strengthened. The overall trend of the comprehensive index of digital finance is relatively more fluctuating, with a slight increase between 2012 and 2013, followed by a decline from 2013 to 2015, a rise between 2015 and 2018, reaching a peak in 2018, and then a decline again until 2020, followed by a sharp increase after 2020. Overall, the trends of the comprehensive index of digital finance and coordinated development of digital finance have been similar in some years but also exhibit differences, indicating that they are interrelated but influenced by different factors.

Bulleted lists look like this:

Table 3 presents the results of the baseline regression model. Model 1 reports the results without including any control variables, considering only the effect of the core explanatory variable, CDDF, on the shadow banking activities of non-financial firms. The results indicate that the regression coefficient of coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities is significantly positive at the 1% level.

Furthermore, Model 2 incorporates firm-level control variables based on results of Model 1. The findings show that the coefficient of shadow banking activities remains significantly positive at the 1% level. In Model 3, industry fixed effects are additionally controlled for, and the coefficient remains significantly positive at the 1% level. Model 4 further introduces year-fixed effects based on Model 3, and the results consistently demonstrate a significantly positive coefficient at the 1% level. Therefore, the coordinated development of digital finance promotes shadow banking activities of non-financial firms, supporting Hypothesis 1 of this study.

4.2. Endogeneity Analysis

The baseline regression assessed the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on the shadow banking activities of non-financial firms, revealing a significant positive effect. However, the results may be biased due to potential reverse causality or omitted variable issues. This study employs the instrumental variable (IV) approach to validate the findings further. Following Xie Xuanli et al. (2018) methodology, the number of broadband internet users per 100 people is selected as a proxy variable for the annual internet penetration rate at the prefecture-level city [

33]. Specifically, the number of broadband internet users each year is divided by the registered population to obtain the number of broadband users per 100 people, which is used as the instrumental variable for the coordinated development of digital finance.

The choice of this instrument is justified as follows: First, broadband internet access is closely related to the development of digital finance. Higher internet penetration typically facilitates the promotion and application of digital finance, satisfying the relevance requirement of the instrumental variable. Second, the broadband internet access and population data used in this study are derived from official macroeconomic statistics published by government agencies. These statistics are unrelated to non-financial firms' behaviors and financial data, satisfying the homogeneity requirement to a certain extent.

Table 4 reports the regression results based on the instrumental variable approach. Model 5 presents the first-stage regression results, showing that the instrumental variable (IV) coefficient is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating a strong correlation between the instrumental variable and the core explanatory variable — coordinated development of digital finance. Model 6 reports the second-stage regression results, where the coefficient of coordinated development of digital finance remains significantly positive at the 1% level. Furthermore, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic rejects the null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, suggesting that the instrument is valid and identifiable. The Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic is 184.263, which exceeds the Stock-Yogo weak instrument threshold of 16.38 at the 10% level, indicating that weak instrument bias is not a concern. Therefore, the conclusions of this study are robust and reliable.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Alternative Measurement of Shadow Banking

To ensure the robustness of the study's findings, this study follows the method of Li Jianjun and Han Xun (2019) [

29]. It redefines shadow banking activities as the proportion of entrusted loans, entrusted wealth management products, private lending, purchases of bank wealth management products, trust products, structured deposits, and asset management plans to total assets. The results are presented in

Table 5. After replacing the core explanatory variable, the coefficient of coordinated development of digital finance remains significantly positive at the 1% level despite a slight decrease in magnitude, which supports the robustness of the baseline regression results.

4.3.2. Lagged Dependent Variable

Considering that the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities may exhibit a lagged effect, this study conducts a robustness test using the dependent variable's lagged value. Column (2) of

Table 5 shows the results using a one-period lag of shadow banking as the dependent variable. The results suggest that the coordinated development of digital finance continues to promote shadow banking activities significantly, consistent with the findings of the baseline regression.

4.3.3. Further Test Based on a Quasi-Natural Experiment

To further examine the robustness of the impact of the coordinated development of digital finance on shadow banking activities of non-financial firms, this study employs a quasi-natural experiment using a policy shock. During the development of the digital finance industry, the government has introduced and implemented a series of policies that significantly influenced the industry landscape. Among them, the Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Healthy Development of Internet Finance, issued on July 18, 2015, represents a key policy. This guideline established the fundamental regulations and outlined the development direction of the digital finance industry. Given the immature regulatory framework during the early development of the digital finance market, implementing this policy facilitated the industry's orderly growth, enhanced market transparency, and reduced systemic risks. Its impact extended beyond the digital finance sector, potentially influencing the financial environment and financing choices of non-financial firms, thus affecting their shadow banking activities.

Based on this policy context, this study treats the policy issuance as an exogenous shock and constructs a quasi-natural experiment. Since the policy implementation is a macro-level external shock unrelated to individual firm characteristics, the quasi-natural experiment satisfies the exogeneity condition. Additionally, given that state-owned firms (SOEs) generally have stronger government support and more stable financing channels. In contrast, private firms face tighter financing constraints and rely more on external financial markets. This study hypothesizes that the sensitivity to digital finance development varies significantly between SOEs and private firms. Accordingly, the study classifies private firms as the treatment group and SOEs as the control group, applying a Difference-in-Differences (DID) model, as specified in Equation (2). To ensure the parallel trends assumption is satisfied — confirming no significant differences between the treatment and control groups before the policy implementation — a dynamic DID model is constructed, as presented in Equation (3).

Recognizing that SOEs and private firms differ significantly in profitability goals and governance structures, leading to potential sample selection bias, this study employs the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method for further verification. The detailed steps are as follows: First, this study conducts a Logit regression based on firm ownership, using variables such as firm age (Age), size (Size), leverage ratio (Lev), cash ratio (Cash), and return on assets (Roa) to estimate the propensity scores. Then, a "one-to-one matching" method is applied to determine the weights, with a "common support" condition imposed. Finally, the original treatment and control groups in the DID regression are replaced with the matched treatment and control groups, and the same analysis process is repeated, resulting in a PSM-DID regression.

The results in

Table 6 indicate that the coefficients of Post×Treat remain significantly positive across all specifications, demonstrating that the coordinated development of digital finance significantly enhances shadow banking activities among non-financial firms. Furthermore, the results of the parallel trends test show that the coefficient of Before × Treat is not significant, while After × Treat is significantly positive. It supports the validity of the assumption of parallel trends, further affirming the robustness of the conclusion.

This study conducts a placebo test to ensure that unobservable factors do not drive the findings. Specifically, private firms are randomly assigned as the placebo treatment group, while SOEs serve as the placebo control group. A DID regression is then performed, extracting the coefficient and standard error of the core explanatory variable to calculate the t-statistic. This simulation is repeated 1,000 times. The results show that the estimated coefficients and t-values are distributed around zero, with the average values differing significantly from the true values, and most of the coefficients are not significant. These results confirm that the observed effect of digital finance on shadow banking is not driven by unobserved factors, supporting the robustness of the empirical conclusions.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity of Financing Constraints

Financing constraints influence firms' financing behaviors, especially in imperfect financial markets. Firms with different levels of financing constraints exhibit significant differences in their reliance on external financing channels. Firms with high financing constraints often struggle to obtain sufficient funding from traditional banking systems due to lower credit ratings, insufficient collateral, or lack of financial transparency. In contrast, firms with low financing constraints can easily access bank credit or capital market financing. In the context of the rapid development of digital finance, firms with different levels of financing constraints may exhibit varying degrees of shadow banking activity.

Based on firms' financing constraint levels, this study defines firms with an absolute SA index greater than the industry median as highly constrained, while those below the median are considered firms with low financing constraints.

Table 7 presents the heterogeneity analysis results of the effect of the CDDF on non-financial firms' shadow banking activities. The results show that firms with higher financing constraints experience a more pronounced increase in shadow banking activities as digital finance coordination improves. It suggests that highly constrained firms are more likely to rely on shadow banking financing when traditional credit channels are restricted. The development of digital finance fails to fully address their financing needs, leading to increased shadow banking activities. In contrast, firms with lower financing constraints, with smoother access to traditional credit, rely less on shadow banking.

4.4.2. Heterogeneity of Ownership Structure

Ownership structure significantly affects firms' governance, operational objectives, and risk preferences, influencing their behavior in different economic environments. State-owned firms (SOEs) and non-state-owned firms (non-SOEs) differ considerably in resource allocation, policy implementation, and market adaptability. SOEs often shoulder greater social responsibilities beyond profitability, including maintaining employment and executing national strategies. Non-SOEs, however, are more market-oriented and flexible in decision-making.

This study divides the sample into SOEs and non-SOEs to examine the heterogeneous effects of CDDF on shadow banking activities. As shown in

Table 7, Column (3) represents SOEs, while Column (4) represents non-SOEs. The results indicate that as digital finance coordination improves, the increase in shadow banking activities is more pronounced for SOEs than non-SOEs. This phenomenon may be attributed to SOEs' operational goals and risk management models. SOEs often possess stronger resource integration capabilities and policy advantages, gaining preferential access to traditional credit and government support funds. However, as digital finance advances, SOEs may increasingly use shadow banking for off-balance-sheet financing to optimize capital management, increase leverage, and support industrial chain integration and expansion. Additionally, SOEs tend to have a higher risk tolerance, making them more likely to use shadow banking channels, such as trust asset management plans, or even engage in asset securitization or arbitrage activities.

In contrast, non-SOEs rely more on market competition and adopt market-oriented and prudent financing approaches. During the development of digital finance, non-SOEs tend to choose more transparent and strictly regulated financing methods, such as supply chain finance, rather than engaging in shadow banking activities.

4.4.3. Heterogeneity of Marketization Level

In China, due to varying geographical conditions and resource endowments, provincial capital and non-capital cities exhibit significant differences in development. Provincial capitals generally have more abundant resources, advanced transportation and information technology, and well-established policy frameworks, leading to higher marketization. In contrast, non-capital cities, constrained by geographical and resource limitations, often faceless developed information technology and regulatory systems, resulting in lower levels of marketization. The degree of marketization determines the extent to which the market plays a fundamental role in resource allocation. Higher marketization reduces financial resource misallocation, while lower marketization, characterized by administrative intervention, may increase financial resource misallocation, further promoting shadow banking activities (Han & Li, 2020) [

11].

Based on geographic location, this study classifies firms in provincial capitals as belonging to the high marketization group, while those in non-capital cities are in the low marketization group.

Table 7 presents the results, which indicate that as CDDF improves, firms in highly marketized regions experience a more pronounced increase in shadow banking activities. It may be because firms in highly marketized regions are more likely to receive attention and services from financial institutions and have greater access to financial innovation tools. These firms may use shadow banking channels for capital operations, asset management, and off-balance-sheet business expansion. The development of digital finance provides firms in these regions with more financial instruments and trading platforms, further facilitating their involvement in shadow banking activities.

In contrast, firms in low marketization regions often face limited financial services and fewer information channels, resulting in lower reliance on shadow banking. Additionally, these regions may have stricter local regulatory environments and limited risk control capabilities, further constraining firms' engagement in shadow banking. Firms in these regions are more likely to adopt traditional and transparent financial methods.

5. Additional Analysis

5.1. The "U-shaped" Effect

The coordinated development of digital finance may have two different effects on non-financial firms' shadow banking activities. On the one hand, digital finance coordination improves financing accessibility for firms, especially for small and medium-sized firms (SMEs), which can obtain more convenient and efficient funding through digital financial platforms, thereby reducing their reliance on shadow banking. On the other hand, digital finance coordination also provides more room for innovation within the shadow banking system, enhancing firms' ability to conduct capital operations and leverage expansions through shadow banking activities. Therefore, the relationship between digital finance coordination and shadow banking activities may exhibit nonlinear characteristics. To further explore the nonlinear impact of digital finance coordination on non-financial firms' shadow banking activities, this paper constructs equation (4).

The results, as shown in

Table 8, indicate that the regression coefficient of CDDF is significantly negative. In contrast, the regression coefficient of CDDF2 is significantly positive, suggesting a "U-shaped" nonlinear relationship between the coordinated development of digital finance and non-financial firms' shadow banking activities. At the same time, this paper conducts a U-test for the "U-shaped" relationship between the two, with the turning point of the curve at 0.6197, which lies within the range of the independent variable [0.000, 1.000], and the t-value equals 15.15 with a p-value less than 0.001, indicating an effective turning point within the existing range. Analyzing the sample range shows that the current level of digital finance development among firms in China is partially in the descending stage of the U-shaped curve and partially in the ascending stage, which aligns with the actual situation. It suggests that the degree of shadow banking activities decreases in the early stages of digital finance coordination. However, when digital finance coordination reaches a certain level, shadow banking activities increase, confirming Hypothesis 2 of this study.

5.2. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Regulation on the "U-shaped" Effect

With the intensification of global environmental issues, environmental regulation has become an important policy tool for governments to intervene in firms' business activities, aiming to promote green transformation and sustainable development. Environmental regulation affects firms' production models and has a profound impact on their financing decisions, capital operations, and risk management. Environmental regulation may play a key moderating role in the relationship between digital finance coordination and shadow banking activities.

To analyze the impact of environmental regulation further, this paper adds an environmental regulation term, interaction terms between environmental regulation and shadow banking activities, and the interaction term of the square of environmental regulation and shadow banking activities to equation (4). Grouped regression is performed based on the intensity of environmental regulation, defining those above the median of environmental regulation as high environmental regulation and those below as low environmental regulation, respectively examining the impact of digital finance coordination on shadow banking activities under high and low environmental regulation conditions. The model constructed is equation (5).

The regression results are shown in

Table 8. In the case of low environmental regulation intensity, the regression coefficient of CDDF is significantly negative, the regression coefficient of CDDF2 is significantly positive, CDDF × Er is significantly positive, and the interaction term CDDF2 × Er is significantly negative. These results suggest that under low environmental regulation, the enhancement of environmental regulation strengthens the role of digital finance coordination in promoting non-financial firms' shadow banking activities while suppressing the nonlinear effect on shadow banking activities. In other words, to some extent, environmental regulation weakens the "U-shaped" effect of digital finance coordination, making its effect on shadow banking activities more direct, confirming Hypothesis 3a. In the case of high environmental regulation intensity, the regression coefficient of CDDF is negative but not significant, and the regression coefficient of CDDF2 is also not significant, indicating that under high environmental regulation conditions, the "U-shaped" effect of digital finance on shadow banking activities is more ambiguous. Moreover, the interaction terms CDDF × Er and CDDF2 × Er are both insignificant, indicating that the enhancement of environmental regulation has not significantly affected the path of digital finance's effect on shadow banking activities, confirming Hypothesis 3b.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of results

This study investigates the impact mechanism of the coordinated development of digital finance on non-financial firms' shadow banking activities under environmental regulation. Based on data from listed firms on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2012 to 2022, our findings offer several important insights into how digital finance interacts with firm behavior in the context of institutional and market heterogeneity.

First, the results show that the coordinated development of digital finance significantly promotes shadow banking activities among non-financial firms. This finding echoes existing literature which suggests that digital finance reduces information asymmetry, expands access to financial services, and lowers the threshold for financial participation, thereby encouraging off-balance-sheet activities that characterize shadow banking. While these developments improve financing efficiency and inclusiveness, they may also blur regulatory boundaries, posing challenges to traditional financial supervision.

Second, the heterogeneity analysis reveals that the influence of digital finance coordination is more pronounced in firms with high financing constraints, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and firms operating in regions with a higher degree of marketization. These results suggest that firms with limited access to formal financing channels or those with institutional advantages are more inclined to leverage digital finance to engage in shadow banking. In particular, SOEs may exploit their preferential access to financial resources and regulatory leniency to expand financial operations beyond their core businesses. Similarly, in more market-oriented regions, the advanced digital infrastructure and financial openness may provide favorable conditions for shadow banking to flourish under digital finance.

Third, a U-shaped nonlinear relationship is found between digital finance coordination and firms' shadow banking activities. This implies that at the early stages, digital finance development plays a positive role in promoting financial inclusion and innovation. However, beyond a certain threshold, its marginal effect turns negative, potentially due to over-financialization, excessive risk-taking, or speculative behaviors. This result supports theories emphasizing the dual effects of financial development—where excessive financialization may harm real economic performance .

Fourth, environmental regulation serves as an important moderating factor. In regions with low environmental regulatory pressure, the enhancement of environmental regulation amplifies the positive relationship between digital finance and shadow banking, while mitigating the nonlinear U-shaped effect. This may be because stricter regulation increases firms’ demand for flexible financing to cover compliance costs, thereby boosting shadow banking activities. Conversely, in regions with strong environmental regulation, the moderating effect becomes less significant, potentially due to mature institutional frameworks or the availability of formal green financing options.

6.2. Policy Proposal

Based on the above findings, several practical policy implications emerge. First, the coordinated development of digital finance is crucial for adapting to the ongoing digital transformation of the financial sector. Policymakers should strengthen macro-level oversight, refine regulatory frameworks for digital financial services, and clearly delineate the boundaries and legal responsibilities associated with shadow banking activities. Efforts should also be made to channel digital finance toward supporting the real economy, especially through developing financial products that align with firms’ operational needs and curbing its misuse for speculative or informal financial activities.

Second, differentiated policy strategies are needed to address firm-level heterogeneity. For firms facing high financing constraints, policy instruments such as subsidized credit or expanded formal financing channels could reduce their dependence on shadow banking. For state-owned enterprises, enhanced supervision of internal financial operations is essential to limit excessive financialization. Additionally, improving financial infrastructure and service accessibility in less marketized regions can help reduce the regional disparities in shadow banking activity.

Third, regulatory responses should be dynamic across different stages of digital finance development. In the early phase, policy support should prioritize technological innovation and financial infrastructure construction. As digital finance matures and potentially fuels shadow banking, regulations should shift toward strengthening oversight, standardizing business practices, and promoting inclusive, formal financing alternatives.

Finally, environmental regulation should be harmonized with financial policy. In regions with lax environmental enforcement, gradually increasing regulatory intensity can deter firms from resorting to shadow banking to bypass compliance. In contrast, in areas with strong environmental regulation, promoting green finance initiatives and expanding access to environmentally oriented financial products can reduce firms’ incentives to seek informal financing, thereby mitigating the non-linear effects observed in this study.

7. Conclusions

Although the rapid development of digital finance has attracted widespread attention, its impact on corporate financial behavior—particularly shadow banking activities—remains underexplored. This study investigates how the coordinated development of digital finance influences shadow banking activities among non-financial firms, while also examining the moderating role of environmental regulation. Using panel data from non-financial firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2012 to 2022, several key findings emerge. First, digital finance coordination significantly promotes shadow banking activities. Second, there exists a U-shaped nonlinear relationship between digital finance development and shadow banking, suggesting dual effects—initially beneficial but potentially risky beyond a certain point. Third, the effect is more pronounced in firms facing higher financing constraints, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and those located in regions with a higher degree of marketization. Fourth, environmental regulation serves as a critical moderating factor: in regions with low regulatory pressure, its enhancement strengthens the positive impact of digital finance while attenuating the U-shaped effect; whereas in regions with stricter regulation, the moderating role becomes less significant.

Nonetheless, there are limitations to this research.First, shadow banking activities are inherently opaque, and although we adopt a relatively robust proxy, measurement bias may still exist. Second, our sample is limited to listed firms in China, excluding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and unlisted firms, which may exhibit different financial behaviors. Third, the analysis primarily focuses on macro-level and institutional variables, leaving firm-level behavioral mechanisms underexplored.

Future research can build on this study in several directions. First, incorporating internal factors such as managerial incentives and risk preferences may help uncover the micro-level pathways through which digital finance influences shadow banking. Second, with the rise of green and sustainable finance, it is worthwhile to examine how environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations affect firms’ choices between formal and informal financing under digital finance. Third, expanding the empirical scope to include cross-country or cross-industry comparisons would enhance the external validity and generalizability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and X.X.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Y., Y.Z. and X.X.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, X.X.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available, but may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie Xueyan, Zhu Xiaoyang. Digital Finance and SME's Technological Innovation——Evidence from NEEQ Companies [J]. Studies of International Finance, 2021, (01): 87–96.

- Jiang Hongli, Jiang Pengcheng. Can Digital Finance Improve Enterprise Total Factor Productivity? Empirical Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies [J]. Journal of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 2021, 23(03): 3–18.

- Demertzis M, Merler S, Wolff G B. Capital Markets Union and the Fintech Opportunity [J]. Journal of Financial Regulation, 2018, 4(1): 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Lu L. Promoting SME Finance in the Context of the Fintech Revolution: A Case Study of the UK's Practice and Regulation [J]. Banking and Finance Law Review, 2018: 317–343.

- Lin Aijie, Liang Qi, Fu Guohua. Development of Digital Finance and Enterprise Deleveraging [J]. Journal of Management Science, 2021, 34(01): 142–158.

- Gomber P, Kauffman R J, Parker C, et al. On the Fintech Revolution: Interpreting the Forces of Innovation, Disruption, and Transformation in Financial Services [J]. Journal of Management Information Systems, 2018, 35(1): 220–265. [CrossRef]

- Liu Jun, Sheng Hongqing, Ma Yan. The Mechanism of Corporate Enterprises Participating in Shadow Banking Businesses and Its Model Analysis of Social-Welfare Net Loss [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2014, (05): 96–109.

- Wang Yongqin, Liu Zihan, Li Chang, et al. Identifying Shadow Banking Activities of Non-Financial Firms: Evidence from Consolidated Balance Sheets [J]. Journal of Management World, 2015, (12): 24–40. (in Chinese).

- Huang Xianhuan, Jia Min. Multiple Major Shareholders and Shadow Banking of Non-financial Enterprises [J]. Operations Research and Management Science, 2023, 32(07): 190–196.

- Huang Xianhuan, Yao Rongrong. Capital Market Liberalization and Shadow Banking of Non-Financial Enterprises [J]. Studies of International Finance, 2021, (11): 87–96.

- Han Xun, Li Jianjun. Financial Mismatch, the Shadow Banking Activities of Non-Financial Enterprises and Funds Being Diverted Out of the Real Economy [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2020, (08): 93–111.

- Bai Jun, Gong Xiaoyun, Zhao Xiangfang. Credit Mismatch and Non-financial Firms' Shadow Banking Activities——Evidence Based on Entrusted Loans [J]. Accounting Research, 2022, (02): 46–55.

- Fu Qiuzi, Huang Yiping. Digital Finance's Heterogeneous Effects On Rural Financial Demand: Evidence From China Household Finance Survey and Inclusive Digital Finance Index [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2018, (11): 68–84.

- Gong Qiang, Zhang Yilin, Lin Yifu. Industrial Structure, Risk Characteristics, and Optimal Financial Structure [J]. Economic Research Journal, 2014, 49(04): 4–16.

- Xie Ping, Zou Chuanwei, Liu Hai'er. The Fundamental Theory of Internet Finance [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2015, (08): 1–12.

- Guo Feng, Wang Jingyi, Wang Fang, et al. Measuring China's Digital Financial Inclusion: Index Compilation and Spatial Characteristics [J]. China Economic Quarterly, 2020, 19(04): 1401–1418.

- Gu Haifeng, Yang Lixiang. Internet Finance and Bank Risk-Taking: Evidence from the Chinese Banking Sector [J]. The Journal of World Economy, 2018, 41(10): 75–100.

- Yao Qian. The Differences and Practical Significance between Distributed Ledger and Traditional Ledger [J]. Tsinghua Financial Review, 2018, (06): 64–68. (in Chinese).

- Xie Xuanli, Shen Yan, Zhang Haoxing, et al. Can Digital Finance Promote Entrepreneurship? - Evidence from China [J]. China Economic Quarterly, 2018, 17(04): 1557–1580.

- Huang Yiping, Huang Zhuo. The Development of Digital Finance in China: Present and Future [J]. China Economic Quarterly, 2018, 17(04): 1489–1502.

- He Dexu, Miao Wenlong. Financial Exclusion, Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Financial Institution in China [J]. Finance & Trade Economics, 2015, (03): 5–16.

- Gomber P, Kauffman R J, Parker C, et al. On the Fintech Revolution: Interpreting the Forces of Innovation, Disruption, and Transformation in Financial Services [J]. Journal of Management Information Systems, 2018, 35(1): 220–265. [CrossRef]

- Buchak G, Matvos G, Piskorski T, et al. Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of Shadow Banks [J]. Journal of Financial Economics, 2018, 130(3): 453–483.

- Zhu Jiaxiang, Shen Yan, Zou Xin. P2P Lending in China and the Role of Regulation Technology: Inclusive Financing or Ponzi Scheme? [J]. China Economic Quarterly, 2018, 17(04): 1599–1622.

- Porter M E, Kramer M R. The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility [J]. Harvard Business Review, 2006, 84(12): 78–92.

- Zhang Cheng, Lu Yang, Guo Lu, et al. The Intensity of Environmental Regulation and Technological Progress of Production [J]. Economic Research Journal, 2011, 46(02): 113–124.

- Wang Yao, Pan Dongyang, Peng Yuchao, et al. China's Incentive Policies for Green Loans: A DSGE Approach [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2019, (11): 1–18.

- Chakraborty P, Chatterjee C. Does Environmental Regulation Indirectly Induce Upstream Innovation? New Evidence from India [J]. Research Policy, 2017, 46(5): 939–955. [CrossRef]

- Li Jianjun, Han Xun. The Effect of Financial Inclusion on Income Distribution and Poverty Alleviation: Policy Framework Selection for Efficiency and Equity [J]. Journal of Financial Research, 2019, (03): 129–148.

- Si Dengkui, Li Xiaolin, Zhao Zhongkuang. Non-financial Enterprises' Shadow Banking Business and Stock Price Crash Risk [J]. China Industrial Economics, 2021, (06): 174–192.

- Chen Z, Kahn M E, Liu Y, et al. The Consequences of Spatially Differentiated Water Pollution Regulation in China [J]. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 2018, 88: 468–485. [CrossRef]

- Chen Shiyi, Chen Dengke. Air Pollution, Government Regulations and High-quality Economic Development [J]. Economic Research Journal, 2018, 53(02): 20–34.

- Xie Xuanli, Shen Yan, Zhang Haoxing, et al. Can Digital Finance Promote Entrepreneurship? Evidence from China [J]. China Economic Quarterly, 2018, 17(04): 1557–1580.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).