Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Propositions

2.1. Complexity and Configurational Theory

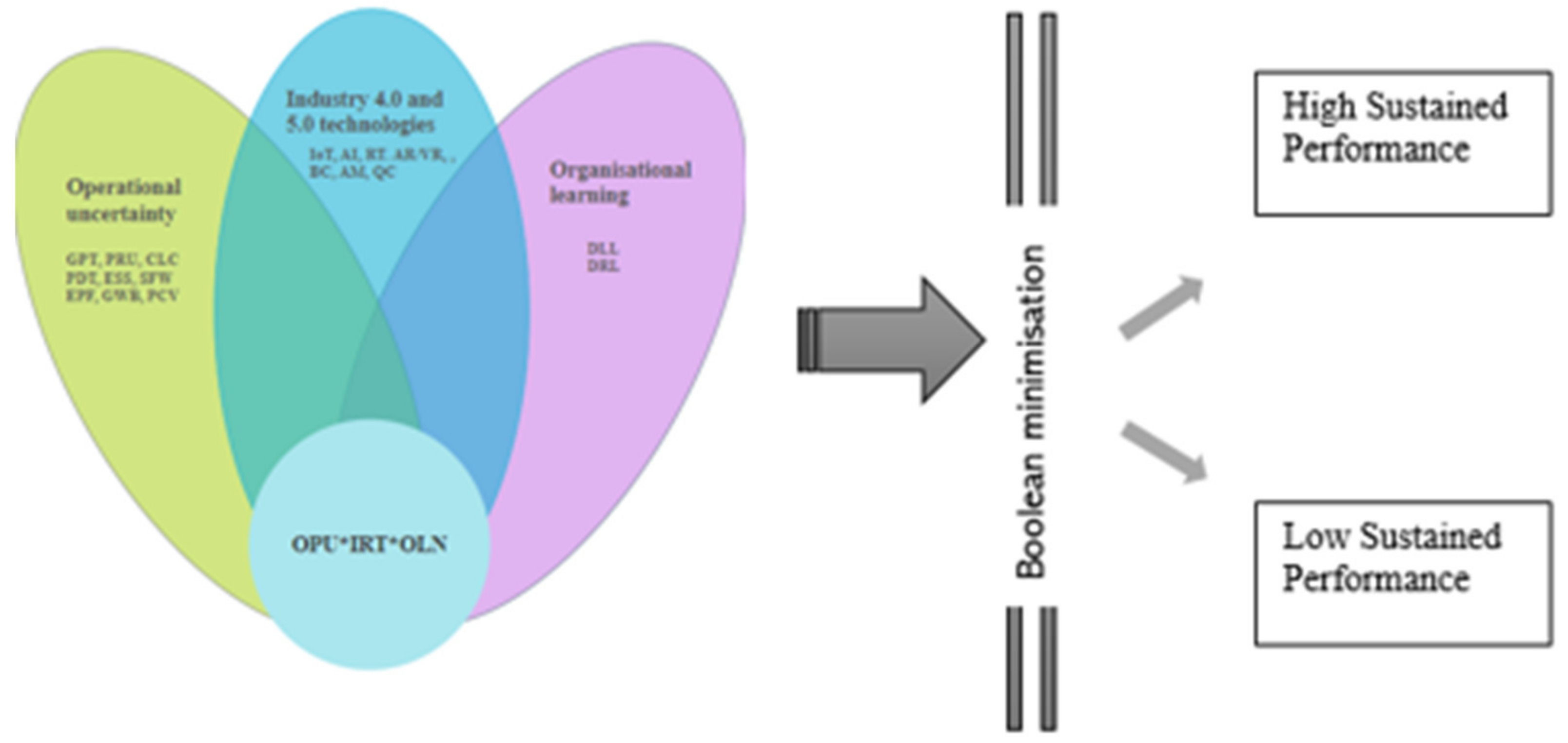

2.2. Configuration Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

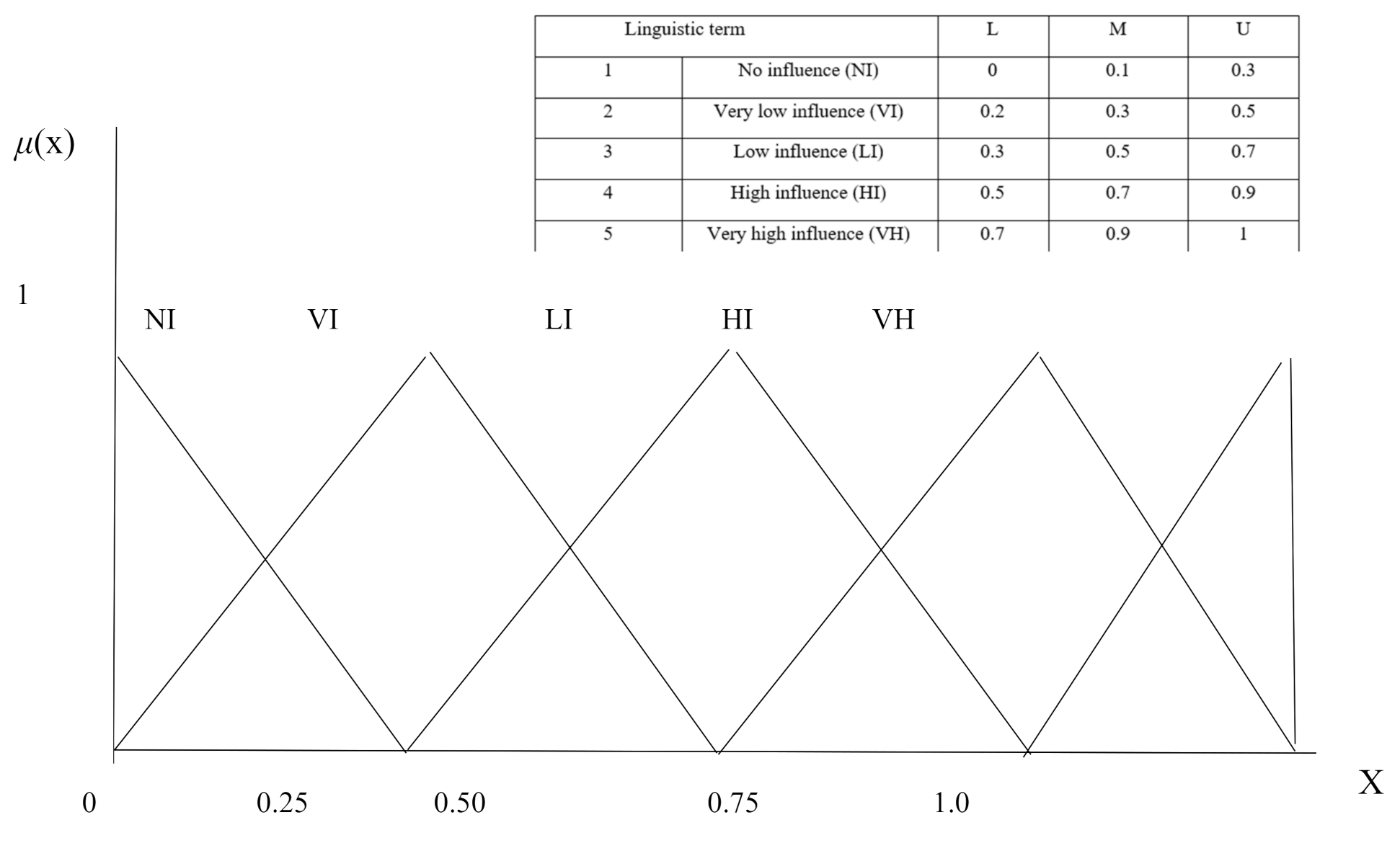

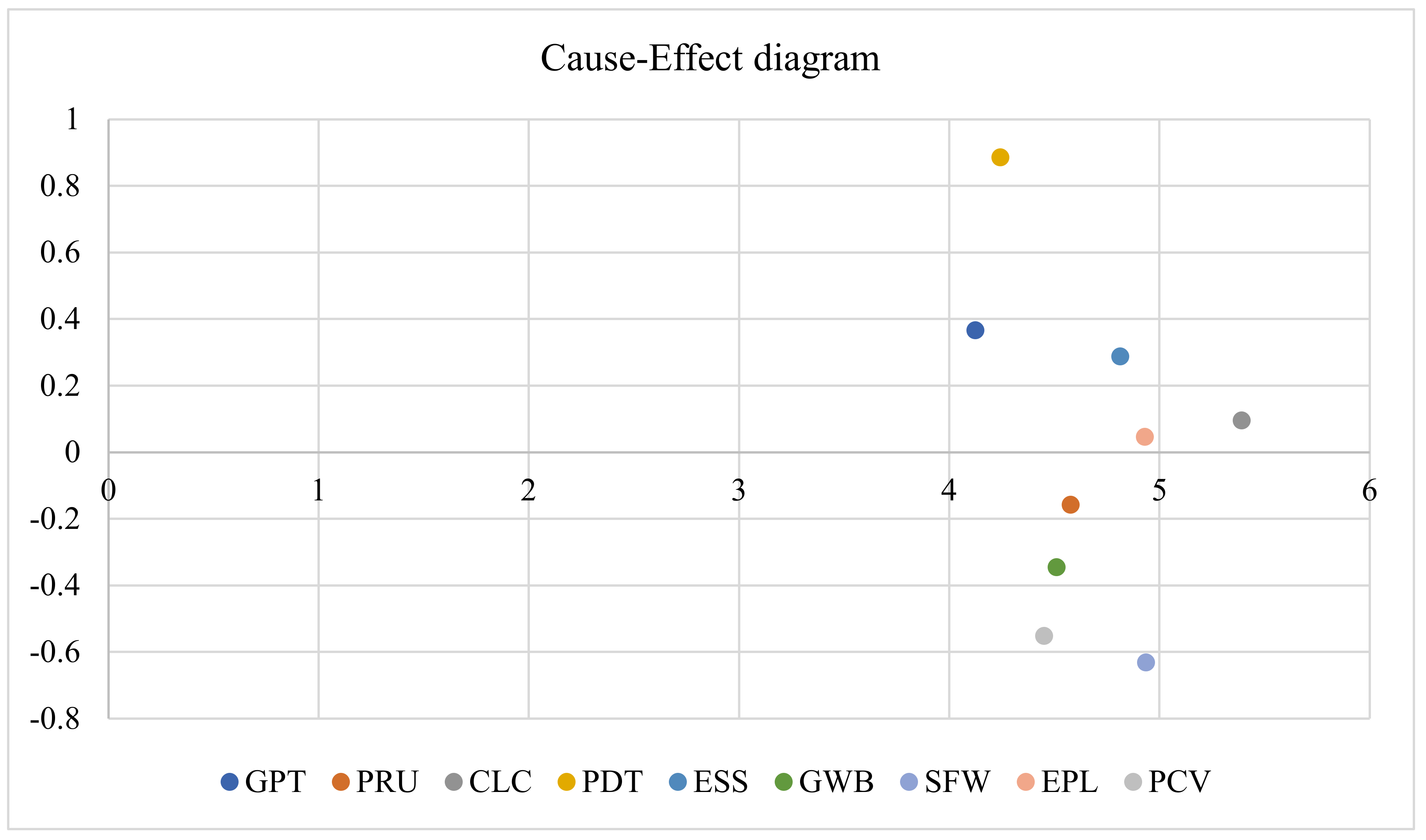

4.1. Causal Conditions of Operational Uncertainty with Fuzzy DEMATEL

4.2. Build Configurations

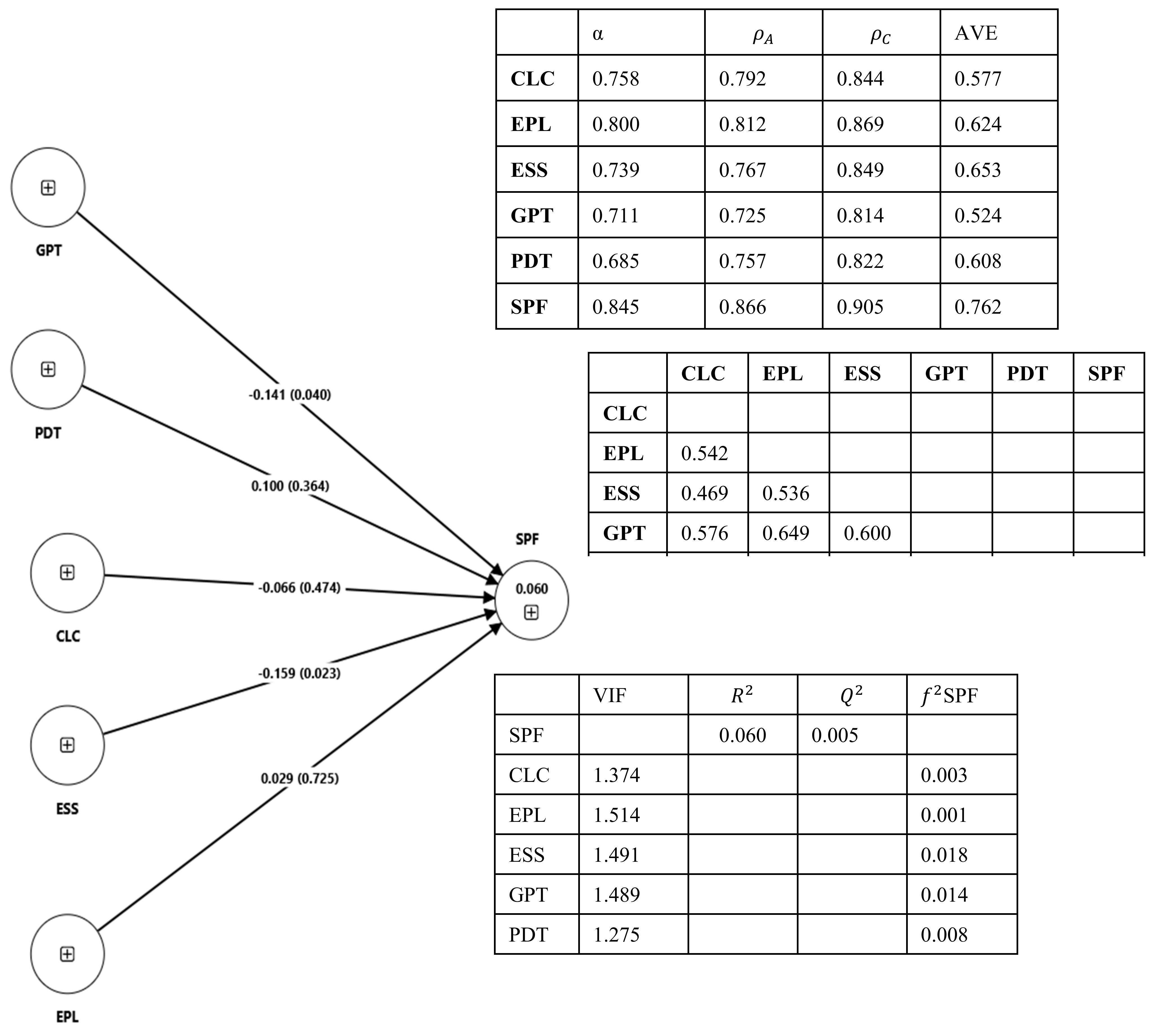

4.3. Structural Models – Direct Effect of Causal Model

4.4. Geopolitical Tension

4.4.2. Energy Stability and Security

4.4.3. Operational Uncertainty Construct

5. Discussion

5.1. Development of Framework

5.2. Theoretical Perspective

6. Conclusions

References

- Abdullah, F.M., Al-Ahmari, A.M., Anwar, S., 2023. A Hybrid Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model for Evaluating the Influence of Industry 4.0 Technologies on Manufacturing Strategies. Machines 11, 310. [CrossRef]

- Akundi, A., Euresti, D., Luna, S., Ankobiah, W., Lopes, A., Edinbarough, I., 2022. State of Industry 5.0—Analysis and Identification of Current Research Trends. Appl. Syst. Innov. 5, 27. [CrossRef]

- Alsamhi, M.H., Al-Ofairi, F.A., Farhan, N.H.S., Al-ahdal, W.M., Siddiqui, A., 2022. Impact of Covid-19 on firms’ performance: Empirical evidence from India. Cogent Bus. Manag. 9, 2044593. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, V., Collier, N., Jenkins, M. 2009. A configurational approach to the dynamics of firm level knowledge. Journal of Strategy and Management, 2(1), 4–30.

- Aryeetey, E., Baffour, P.T., 2022. African competitiveness and the business environment: Does manufacturing still have a role to play? J. Afr. Econ. 31, i33–i58.

- Asif, M., Yang, L., Hashim, M., 2024. The role of digital transformation, corporate culture, and leadership in enhancing corporate sustainable performance in the manufacturing sector of China. Sustainability 16, 2651.

- Attiah, E., 2019. The Role of Manufacturing and Service Sectors in Economic Growth: An Empirical Study of Developing Countries. Eur. Res. Stud. J. XXII, 112–127. [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, S. B., 1989. Organizational Theories: Some Criteria for Evaluation. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 496. [CrossRef]

- Basten, D., Haamann, T., 2018. Approaches for Organizational Learning: A Literature Review. Sage Open 8, 2158244018794224. [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A., Kamble, S., Subramanian, N., Singh, R.K., Venkatesh, M., 2024. Digital capabilities to manage agri-food supply chain uncertainties and build supply chain resilience during compounding geopolitical disruptions. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 44, 1914–1950. [CrossRef]

- Brownstein, N.C., Louis, T.A., O’Hagan, A., Pendergast, J., 2019. The Role of Expert Judgment in Statistical Inference and Evidence-Based Decision-Making. Am. Stat. 73, 56–68. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D., 2005. Complexity, Configurations and Cases. Theory, Culture & Society, 22, 5, 95–111. [CrossRef]

- Cangialosi, N., 2023. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) in Organizational Psychology: Theoretical Overview, Research Guidelines, and A Step-By-Step Tutorial Using R Software. Span. J. Psychol. 26, e21. [CrossRef]

- Cantore, N., Clara, M., Lavopa, A., Soare, C., 2017. Manufacturing as an engine of growth: Which is the best fuel? Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 42, 56–66. [CrossRef]

- Charoenwong, B., Han, M., Wu, J., 2023. Trade and Foreign Economic Policy Uncertainty in Supply Chain Networks: Who Comes Home? Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 25, 126–147. [CrossRef]

- Charpin, R., Cousineau, M., 2024. Friendshoring: how geopolitical tensions affect foreign sourcing, supply base complexity, and sub-tier supplier sharing. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag.

- Choi, T., Cheng, T.C.E., Zhao, X., 2016. Multi-Methodological Research in Operations Management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 25, 379–389. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J, 1988. Set Correlation and Contingency Tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B., Glaesser, J., 2016. Exploring the robustness of set theoretic findings from a large n fsQCA: an illustration from the sociology of education. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 19, 445–459. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G., 1977. Sampling techniques. Johan Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Dewa, M., Van Der Merwe, A., & Matope, S., 2020. Production scheduling heuristics for frequent load-shedding scenarios: a knowledge engineering approach. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 31, 3. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Peng, C.-Y.J., 2013. Principled missing data methods for researchers. SpringerPlus 2, 222. [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building Better Causal Theories: A Fuzzy Set Approach to Typologies in Organization Research. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 2, 393–420. [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P. C., Marx, A., & Cambré, B., 2013. Chapter 1 configurational theory and methods in organizational research: Introduction. In Configurational theory and methods in organizational research (pp. 1–22). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/S0733-558X(2013)0000038005/full/html.

- Greckhamer, T., Furnari, S., Fiss, P.C., Aguilera, R.V., 2018. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 16, 482–495. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H., Kumar, A., Wasan, P., 2021. Industry 4.0, cleaner production and circular economy: An integrative framework for evaluating ethical and sustainable business performance of manufacturing organizations. J. Clean. Prod. 295, 126253.

- Hair, J.F., Risher, J.J., Sarstedt, M. and Ringle, C.M., 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European business review, 31, 1, 2-24.

- Hauge, J., 2023. Manufacturing-led development in the digital age: how power trumps technology. Third World Q. 44, 1960–1980. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T.K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D.W., Ketchen, D.J., Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Calantone, R.J., 2014. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 17, 182–209. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., Bentler, P.M., 1998. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3, 424–453. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Burton-Jones, A., Xu, D., 2024. A configurational theory of digital disruption. Inf. Syst. J. 34, 1737–1786. [CrossRef]

- Iannacci, F., & Kraus, S., 2022. Configurational theory: A review. TheoryHub. Book (ISBN: 978-1-7396044-0-0).

- Ivaldi, S., Scaratti, G. and Fregnan, E., 2022. Dwelling within the fourth industrial revolution: organizational learning for new competences, processes and work cultures. Journal of Workplace Learning, 34, 1, 1-26.

- Jassbi, J., Mohamadnejad, F., & Nasrollahzadeh, H. 2011. A Fuzzy DEMATEL framework for modeling cause and effect relationships of strategy map. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(5), 5967–5973. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W., 2022. An expanded DEMATEL decision-making method by mixing qualitative and quantitative data, in: Wu, F., Liu, J., Chen, Y. (Eds.), International Conference on Computer Graphics, Artificial Intelligence, and Data Processing (ICCAID 2021). Presented at the International Conference on Computer Graphics, Artificial Intelligence, and Data Processing (ICCAID 2021), SPIE, Harbin, China, p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.J., Troth, A.C., 2020. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 45, 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Kan, K., Mativenga, P., & Marnewick, A., 2020. Understanding energy use in the South African manufacturing industry. Procedia CIRP, 91, 445–451. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Tiwari, P., Zymbler, M., 2019. Internet of Things is a revolutionary approach for future technology enhancement: a review. J. Big Data 6, 111. [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L., 2008. Configurational Information as Potentially Negative Entropy: The Triple Helix Model. Entropy 10, 391–410. [CrossRef]

- Li, Mingxing, Qu, T., Yan, M., Li, Ming, He, Z., Huang, G.Q., 2024. Out-of-Order Architecture for Real-Time Data-Driven Resilient Planning and Scheduling of Cyber-Physical Manufacturing Systems, in: 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE). Presented at the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), IEEE, Bari, Italy, pp. 3328–3333. [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.H., 2014. A General Framework of Dealing with Qualitative Data in DEA: A Fuzzy Number Approach, in: Emrouznejad, A., Tavana, M. (Eds.), Performance Measurement with Fuzzy Data Envelopment Analysis, Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 61–87. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Qian, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, Z., 2022. Can artificial intelligence improve the energy efficiency of manufacturing companies? Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, 2091.

- López-Ospina, H., Pardo, D., Rojas, A., Barros-Castro, R., Palacio, K., & Quezada, L., 2022. A revisited fuzzy DEMATEL and optimization method for strategy map design under the BSC framework: selection of objectives and relationships. Soft Computing, 26(14), 6619-6644.

- Malacina, I., Lintukangas, K., 2024. On the edge: a multilevel perspective on innovation complexities and dynamic attractors in the supply network. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. [CrossRef]

- Marcinkiewicz, E. (2017). Pension Systems Similarity Assessment: An Application of Kendall’s W to Statistical Multivariate Analysis. Contemporary Economics, II, 303-314. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3197225.

- Mashapu, L. D., & Mathaba, T. N. D., 2024. The Economic Impact of Load Shedding in Industry: A South African Case Study. 2024 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mejía Trejo, J., 2023. Qualitative Comparative Analysis. VOLUME II. FUZZY-SET (fsQCA) Theory and Practice, Primera edicion. ed. Academia Mexicana de Investigación y Docencia en Innovación SC (AMIDI). [CrossRef]

- Meuer, J., & Fiss, P. C., 2020. Qualitative comparative analysis in business and management research. In Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. Oxford University Press. Available online: https://www.peerfiss.com/s/Meuer-Fiss-ORE-2020.pdf.

- Miller, D., 2018. Challenging trends in configuration research: Where are the configurations? Strategic Organization, 16(4), 453–469. [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F., Greckhamer, T., Furnari, S., Fiss, P.C., Crilly, D., Aguilera, R., 2017. Embracing Causal Complexity: The Emergence of a Neo-Configurational Perspective. J. Manag. 43, 255–282. [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M., 2003. Principles of Mixed Methods. Handb. Mix. Methods Soc. Behav. Res. 189.

- Moslem, S., Ghorbanzadeh, O., Blaschke, T., Duleba, S., 2019. Analysing Stakeholder Consensus for a Sustainable Transport Development Decision by the Fuzzy AHP and Interval AHP. Sustainability 11, 3271. [CrossRef]

- Mtotywa, M.M., Mohapeloa, M, 2025. Multidimensionality of operational uncertainty in manufacturing: Exploring emergent and non-linearity perspective. Unpublished.

- Ndung’u, N., Shimeles, A., Ngui, D., 2022. The Old Tale of the Manufacturing Sector in Africa: The Story Should Change. J. Afr. Econ. 31, i3–i9.

- Nnyanzi, J.B., Kavuma, S., Sseruyange, J., Nanyiti, A., 2022. The manufacturing output effects of infrastructure development, liberalization and governance: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 49, 369–400. [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D., 2008. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 301–314. [CrossRef]

- Oana, I.-E., Schneider, C.Q., Thomann, E., 2021. Qualitative comparative analysis using R: A beginner’s guide. Cambridge University Press.

- Pappas, I.O., Woodside, A.G., 2021. Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 58, 102310. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., Mithas, S., 2020. Organized complexity of digital business strategy: A configurational perspective. Mis Q. 44.

- Pattyn, V., Álamos-Concha, P., Cambré, B., Rihoux, B., Schalembier, B., 2022. Policy Effectiveness through Configurational and Mechanistic Lenses: Lessons for Concept Development. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 24, 33–50. [CrossRef]

- Pla-Barber, J., Villar, C., & Benito-Sarriá, G., 2020. Configurational Theory in Traditional Manufacturing Industries: A New Model of High-Performing Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability, 12, 17, 6818. [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C., 2009. Measurement Versus Calibration: A Set-Theoretic Approach, in: Box-Steffensmeier, J.M., Brady, H.E., Collier, D. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology. Oxford University Press, pp. 174–198. [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Olya, H., 2021. The combined use of symmetric and asymmetric approaches: partial least squares-structural equation modeling and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 33, 1571–1592. [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D., 2018. An African growth miracle? J. Afr. Econ. 27, 10–27.

- Sammut-Bonnici, T., 2014. Complexity theory.

- Schneider, C.Q., Wagemann, C., 2012. Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Shi, R., He, Y., Cai, Y., Yang, X., Feng, T., 2023. An Uncertain Operational Risk-Oriented Approach for Manufacturing System Functional Failure Prognosis, in: 2023 Global Reliability and Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-Hangzhou). Presented at the 2023 Global Reliability and Prognostics and Health Management Conference (PHM-Hangzhou), IEEE, Hangzhou, China, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Shieh, J.-I., Wu, H.-H., 2016. Measures of Consistency for DEMATEL Method. Commun. Stat. - Simul. Comput. 45, 781–790. [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J.F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., Ringle, C.M., 2019. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 53, 2322–2347. [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E., Fleiss, J.L., 1979. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 86, 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Signé, L., Johnson, C., 2018. The potential of manufacturing and industrialization in Africa. Afr. Growth Initiat.

- South African Reserve Bank, 2020. Occasional Bulletin of Economic Notes OBEN/20/01.

- Suhan, S, Achar, A.P., 2016. Assessment of PLS-SEM Path Model for Coefficient of Determination and Predictive Relevance of Consumer Trust on Organic Cosmetics. Ushus - J. Bus. Manag. 15, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Sukhov, A., Friman, M., Olsson, L.E., 2023. Unlocking potential: An integrated approach using PLS-SEM, NCA, and fsQCA for informed decision making. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 74, 103424. [CrossRef]

- Szirmai, A. 2012. Industrialisation as an engine of growth in developing countries, 1950–2005. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 23, 406–420. [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.Z. and Olaore, G.O., 2021. Effect of organizational learning and effectiveness on the operations, employees productivity and management performance. Vilakshan-XIMB Journal of Management, 19(2), 110-127.

- Teles, J. (2012). Concordance coefficients to measure the agreement among several sets of ranks. Journal of Applied Statistics, 39(8), 1749–1764. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. R., & Baker, R. M. (2019). Complexity Theory: An Overview with Potential Applications for the Social Sciences. Systems, 7(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Thiem, A. 2016. Standards of good practice and the methodology of necessary conditions in qualitative comparative analysis. Polit. Anal. 24, 478–484.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, 2020. UNIDO: Industrial development report 2020: Industrializin... - Google Scholar [WWW Document]. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Industrial%20development%20report%202020.%20Industrializing%20in%20the%20digital%20age&author=UNIDO&publication_year=2019 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), 2024. South Africa Competitive Industrial Performance Index 2024.

- Wacker, J. G., 1998. A definition of theory: research guidelines for different theory-building research methods in operations management. Journal of operations management, 16(4), 361-385.

- Walker, R.M., Chen, J., Aravind, D., 2015. Management innovation and firm performance: An integration of research findings. Eur. Manag. J. 33, 407–422. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X., Kazmi, S.A.A., Wong, C.Y., 2022. Manufacturing, Exports, and Sustainable Growth: Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability 14, 1646. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-L., Sun, T.-T., Xu, R.-Y., 2023. The impact of artificial intelligence on total factor productivity: empirical evidence from China’s manufacturing enterprises. Econ. Change Restruct. 56, 1113–1146.

- Wellman, N., Tröster, C., Grimes, M., Roberson, Q., Rink, F., Gruber, M., 2023. Publishing Multimethod Research in AMJ: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Acad. Manage. J. 66, 1007–1015. [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G., Nagy, G., Megehee, C.M., 2018. Applying complexity theory: A primer for identifying and modeling firm anomalies. J. Innov. Knowl. 3, 9–25. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group, 2024. Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) - South Africa.

- Xie, B., Liu, H., Alghofaili, R., Zhang, Y., Jiang, Y., Lobo, F. D., Li, C., Li, W., Huang, H., Akdere, M., Mousas, C., & Yu, L.-F. , 2021. A Review on Virtual Reality Skill Training Applications. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2, 645153. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-M., & Huang, Y.-L. (2014). Factors in determining wind farm location: Integrating GQM, fuzzy DEMATEL, and ANP. Renewable Energy, 66, 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B., Jiang, Z., Lyu, A., Wu, J., Wang, Z., Yang, M., Liu, K., Mou, M., Cui, P., 2023. Emergence and Causality in Complex Systems: A Survey on Causal Emergence and Related Quantitative Studies. [CrossRef]

- Yusif, S., Hafeez-Baig, A., Soar, J., Teik, D.O.L., 2020. PLS-SEM path analysis to determine the predictive relevance of e-Health readiness assessment model. Health Technol. 10, 1497–1513. [CrossRef]

| R | D | D+R | D-R | |

| GPT | 1,878 | 2,245 | 4,123 | 0,367 |

| PRU | 2,366 | 2,21 | 4,576 | -0,157 |

| CLC | 2,647 | 2,743 | 5,39 | 0,096 |

| PDT | 1,677 | 2,564 | 4,241 | 0,886 |

| ESS | 2,262 | 2,55 | 4,812 | 0,288 |

| GWB | 2,427 | 2,082 | 4,509 | -0,345 |

| SFW | 2,783 | 2,152 | 4,935 | -0,631 |

| EPL | 2,441 | 2,488 | 4,929 | 0,047 |

| PCV | 2,5 | 1,949 | 4,45 | -0,551 |

| Causal condition Operational uncertainty (X) Validation method: Fuzzy-DEMATEL |

Causal condition Industry 4.0 and 5.0 technologies (W) Validation method: Heatmap, PLS-SEM measurement model |

Causal condition Organisational learning (Z) Validation method: Corrected Item-total correlation, Pearson correlation |

Outcome (Y) Sustained performance Validation method: PLS-SEM measurement model |

| Model I: Growing political tensions (GPT) | Scenario planning and supply chain integration (SPSI)** Flexible production and mass customisation (FPMC) Real-time system and process monitoring and response (RPMR) IoT, AI, ARB, BCC |

Organisational learning (OLN) | Sustained performance (SPF) |

| Model II: Cost of living-driven consumer behavioural change (CLC) | Scenario planning and supply chain integration (SPSI) Flexible production and mass customization (FPMC) IoT, AI, BCC, ARB, BDA* |

||

| Model III: Pandemic turbulence (PDT) | Scenario planning and supply chain integration (SPSI) Flexible production and mass customisation (FPMC) Real-time system and process monitoring and response (RPMR) Protective ecosystem (human and system) (PEHS) IoT, AI, BCC, ARB, BDA*, ARVR, QCP |

||

| Model IV: Operational uncertainty of energy stability and security (ESS) | Real-time system and process monitoring and response (RPMR) Scenario planning and supply chain integration (SPSI) Root cause analysis and sustainable solutions (RCAS) IoT, AI, ARB, BDA*, ARVR |

||

| Model V: Entrenchment power of large firms (EPL) | Scenario planning and supply chain integration (SPSI) IoT, AI, BCC, ARB |

| Solution | ||||||||||||

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| GPT | ⏺ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ◯ | ⏺ | ◯ | ◯ | ||

| OLN | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ◯ | ◯ | ⏺ | ◯ | |||

| SPSI | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ||||

| FPMC | ○ | ⏺ | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ⏺ | |||

| RPMR | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| AI | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ||

| BCC | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Raw coverage | 0.388 | 0.499 | 0.377 | 0.371 | 0.381 | 0.519 | 0.383 | 0.393 | 0.453 | 0.355 | 0.376 | 0.327 |

| Unique coverage | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.005 | 0.056 | 0.004 |

| Consistency | 0.869 | 0.899 | 0.886 | 0.895 | 0.899 | 0.887 | 0.874 | 0.870 | 0.906 | 0.895 | 0.933 | 0.936 |

| Overall solution coverage 0.832 | ||||||||||||

| Solution consistency 0.799 | ||||||||||||

| High SPF: PSPF = f(GPT, OLN, SPSI, FPMC,RPMR, AI, BCC) Note: Black circles indicate the presence of conditions, and empty circles indicate the absence of condition | ||||||||||||

| Large circle: core condition small circle: peripheral condition blank space: "don't care condition | ||||||||||||

| Solution | |||||||||||

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| ESS | ○ | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ||||

| OLN | ◯ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ◯ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ||||

| RCAS | ⏺ | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ○ | ⏺ | ○ | ||

| RPMR | ⏺ | ○ | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ○ | ⏺ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| SPSI | ⬤ | ◯ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ◯ | ⬤ | ◯ | ◯ | ⬤ | ||

| AI | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | |||

| BDA | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | |||||

| Raw coverage | 0.476 | 0.299 | 0.316 | 0.413 | 0.418 | 0.282 | 0.293 | 0.535 | 0.393 | 0.388 | 0.386 |

| Unique coverage | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.007 |

| Consistency | 0.850 | 0.883 | 0.901 | 0.921 | 0.901 | 0.867 | 0.885 | 0.896 | 0.912 | 0.932 | 0.943 |

| Overall solution coverage 0.825 | |||||||||||

| Solution consistency 0.810 | |||||||||||

| Note: Black circles indicate the presence of conditions, and empty circles indicate the absence of condition | |||||||||||

| Large circle: core condition small circle: peripheral condition blank space: "don't care condition Source: Authors | |||||||||||

| Solution | ||||

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Configuration for High SPF | OPU2 | ⏺ | ○ | |

| OLN | ⬤ | ◯ | ||

| PEHS | ○ | ○ | ||

| SPSI | ⬤ | |||

| AI | ⏺ | ⏺ | ||

| ARVR | ○ | |||

| BDA | ⏺ | |||

| Raw coverage | 0.280 | 0.260 | ||

| Unique coverage | 0.043 | 0.021 | ||

| Consistency | 0.895 | 0.925 | ||

| Overall solution coverage 0.686 | ||||

| Solution consistency 0.864 | ||||

| Configuration for low SPF | OPU2 | ○ | ⏺ | ⏺ |

| OLN | ◯ | ⬤ | ||

| PEHS | ○ | ○ | ||

| SPSI | ⬤ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| AI | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | |

| ARVR | ||||

| BDA | ⏺ | ⏺ | ⏺ | |

| Raw coverage | 0.255 | 0.304 | 0.301 | |

| Unique coverage | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Consistency | 0.924 | 0.914 | 0.909 | |

| Overall solution coverage 0.636 | ||||

| Solution consistency 0.849 | ||||

| High SPF | SPF = f(OPU2, OLN, PEHS, SPSI,AI, ARVR, BDA | |||

| Low SPF | ~SPF = f(cOPU2, OLN, PEHS, SPSI,AI, ARVR, BDA | |||

| Large circle: core condition small circle: peripheral condition blank space: "don't care condition | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).