1. Introduction

Karst aquifers, covering 12% of the global land surface area, store water resources critical to the survival of 20–25% of the world’s population [

1]. In northern China, carbonate rocks are distributed across 685,000 km², hosting karst groundwater resources of 10.88 billion m³/year [

2]. These karst waters supply drinking water to over 30 prefecture-level cities and more than 100 county-level cities in northern China, while also meeting 70% of the domestic and industrial water demands for large coal mines and supporting irrigation for thousands of hectares of farmland [

3]. Karst springs, as natural discharge pathways of karst groundwater, provide direct and accessible high-quality water sources for industrial, agricultural, and residential use in northern karst regions. Current research on typical karst springs, both domestically and internationally, primarily focuses on the dynamic variations of spring discharge in response to climate change [

4,

5,

6], as well as groundwater pollution status and hydrochemical characteristics in karst spring catchments [

7,

8,

9]. However, under global climate change and increasing human water demands, northern China’s karst springs have experienced declining flow rates, water quality deterioration, and degradation of ecological functions in spring catchments [

10,

11]. A notable example is the Shandong Laiwu Basin, where major karst springs such as Guoniang Spring, Niuwang Spring, and Yuchi Spring have dried up, accompanied by karst collapses within the catchment areas [

12].

Karst hydrogeochemistry serves as a critical tool for studying the state and dynamics of karst groundwater [

13]. Investigating the hydrochemical characteristics and formation mechanisms of karst springs can reveal the sources of major ions and controlling factors in groundwater, providing scientific references for the rational development, utilization, and protection of groundwater resources in spring catchments, as well as supporting the restoration of their ecological functions. The hydrochemical features of karst water are shaped by a combination of natural factors (e.g., precipitation, surface water, sedimentary environments) and anthropogenic influences (e.g., pollution, groundwater extraction), reflecting long-term interactions between groundwater and its environment. Major ion compositions in water are commonly used to analyze hydrochemical controls and material sources. Current mature methodologies integrate hydrogeological conditions, hydrogeochemical theories, and human activities, employing statistical analyses and ion ratio coefficients to systematically identify hydrochemical distribution patterns, controlling mechanisms, and origin pathways [

14].

In recent years, the China Geological Survey has conducted nearly 20 standard 1:50,000 scale hydrogeological surveys in the Central Shandong Mountainous Area, achieving significant progress in understanding karst hydrogeological conditions, regional tectonic settings, and karst development characteristics [

15]. The Laiwu Basin, one of the representative basins in the Central Shandong Mountainous Area, hosts Lower Cambrian to Middle Ordovician karst aquifers distributed within and around its boundaries. Based on field investigations of springs and a comparative analysis of hydrogeological and hydrochemical characteristics among spring sites, this study aims to elucidate the formation conditions and material sources of karst springs in the Laiwu Basin, thereby providing guidance for the rational development and scientific management of karst spring resources.

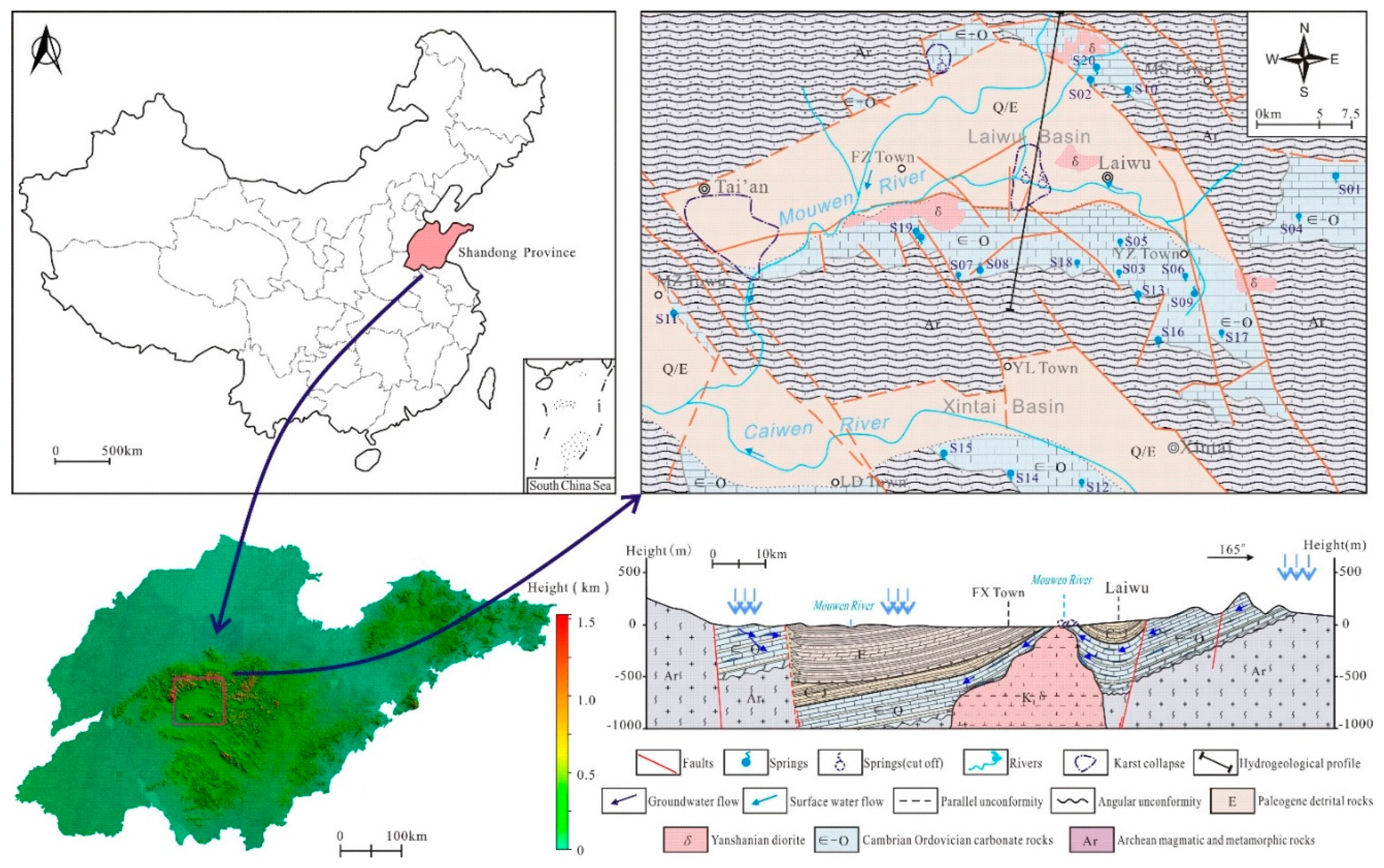

2. Study Area

The Laiwu Basin is situated in the Central Shandong Tai-Yi Mountainous Area, with a terrain generally descending from north to south and east to west. The basin is surrounded by mountains to the north, east, and south, while its central area comprises a low-relief plain with minor undulations, and the western section opens widely. The basin has an overall elevation of 150–200 m. Located in a mid-latitude inland zone, it experiences a temperate continental climate with distinct seasons: dry and windy springs, hot and rainy summers, and a multi-year average precipitation of 760.0 mm. The region’s river system is dominated by the Wen River, which flows southward from its northern headwaters. The main trunk of the Wen River system is the Muwen River, with major tributaries including the Yingwen River and Shiwen River. Influenced by seasonal precipitation and evaporation, the river system exhibits significant fluctuations in flow and water levels [

15]. Within the basin, karst groundwater resources exhibit uneven distribution, characterized by widespread scattered recharge and localized enrichment [

16].

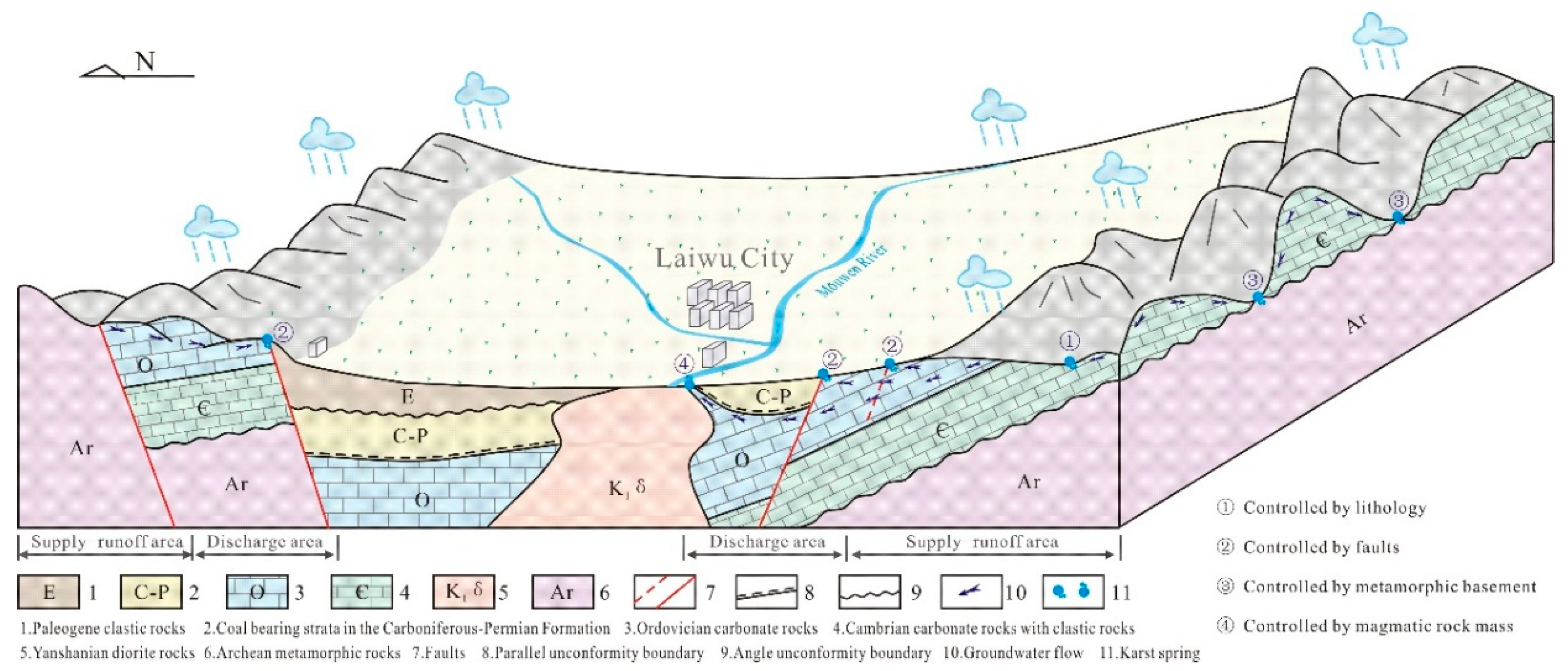

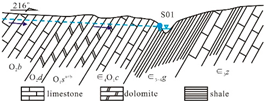

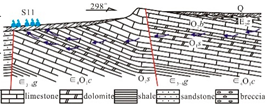

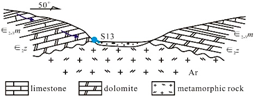

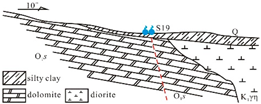

The sedimentary evolution and stratigraphic distribution of the Laiwu Basin are governed by the NEE-trending Dawangzhuang–Tongyedian fault zone and the NW-trending Kouzhen–Chenliangpo fault zone. In the northern part of the basin, weakly water-rich Archean metamorphic granitic rocks are distributed, where groundwater flows southward into the basin as subsurface runoff. Within the carbonate rock fault blocks bounded by these two fault zones, some karst springs emerge. The southern part of the basin comprises a monoclinal fault block composed of Lower Paleozoic strata, generally dipping northward. The southern section of the monoclinal block serves as the groundwater recharge zone dominated by Archean metamorphic granitic rocks. The central section of the block, where Cambrian–Ordovician carbonate rocks are distributed, functions as a groundwater recharge and runoff zone. Here, groundwater occurs as fractured-karst water in carbonate rocks and carbonate rocks interbedded with clastic rocks, constituting the main distribution area of karst springs. From the northern section of the block to the piedmont concealed carbonate zone, strongly water-rich Ordovician carbonate aquifers are developed. Within the basin interior, the underlying Carboniferous–Permian, Cretaceous, and Paleogene clastic aquifers, along with the large-scale Jurassic diorite intrusions (e.g., Jiaoyu and Kuangshan plutons), exhibit weak water abundance or act as aquitards (

Figure 1) [

12].

3. Data Sources and Research Methods

From October 2017 to November 2018, based on field investigations, a total of 20 representative karst spring water samples were collected across the Laiwu Basin and its surrounding areas (sampling locations shown in

Figure 1). Sampling was synchronized with on-site water quality rapid testing, and samples were collected only after field parameters stabilized. The collected water was filtered through 0.45 μm membranes and stored in pre-cleaned polyethylene bottles. For cation analysis, nitric acid was added to subsamples to maintain pH < 2.

All samples were analyzed by the Shandong Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Geo-mineral Exploration. During sampling, in-situ parameters including water temperature, TDS, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO.), electrical conductivity, and Eh were measured using a multiparameter water quality meter (in-Situ SMARTROLL). Laboratory analyses strictly followed standardized groundwater quality testing protocols:

Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, and K⁺ concentrations were determined by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS; contrAA300, Analytik Jena, Germany). HCO₃⁻ was measured via acid-base indicator titration. Cl⁻, NO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻ concentrations were quantified using ion chromatography (IC883, Metrohm, Switzerland).

The calculated ion charge balance error (ICBE) of the tested water samples (Equation 1) was within ±5%, confirming high reliability of the analytical results.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Distribution and Genesis of Karst Springs

Based on 1:50,000 hydrogeological surveys conducted across 10 standard map sheets (including Laiwu City and Dongwangzhuang) in the Laiwu Basin and surrounding areas during 2016–2018, statistical analyses were performed on the hydrogeological and hydrochemical characteristics of 12 karst springs with discharge exceeding 5 L/s in the basin and its periphery, as summarized in

Table 1.According to the basin’s structural framework, the genetic control factors of these karst springs are categorized into three aspects: faults, intrusive bodies, and lithology. Consequently, the genetic types of major karst springs in the Laiwu Basin are classified into four categories: lithology-controlled, fault-controlled, basement-controlled, and intrusion-controlled. Their distribution patterns are as follows:

Lithology-controlled springs: Predominantly distributed along the contact zones between Cambrian–Ordovician carbonate rocks and Cambrian clastic rocks. Emerge at lithological transition boundaries where groundwater flow is blocked by clastic strata. Representative example: Qishan Spring (S01). Fault-controlled springs: Mainly located on the footwalls of deep-seated peripheral faults (e.g., Tai’an–Laiwu Fault and Nanliu Fault). Groundwater discharge is impeded by Paleogene clastic strata within the basin. Representative examples: Shangquan Spring Group (S11) and the now-dry Yuchi Spring. Basement-controlled springs: Widely distributed in the study area, occurring at angular unconformities between the Lower Cambrian Zhushadong Formation dolomite and Archean metamorphic granitic rocks. Result from groundwater blockage by metamorphic granitic basement. Representative example: Shanjiazhuang Spring (S13). Intrusion-controlled springs: Primarily distributed around Yanshanian diorite intrusions at the basin periphery or interior. Form where karst groundwater flow is obstructed by diorite bodies. Representative examples: Zhifang Spring Group (S19) and the extinct Guoniang Spring (historical discharge: 150–350 L/s, 1974 data [

17]).

4.2. Groundwater Chemistry Characteristics

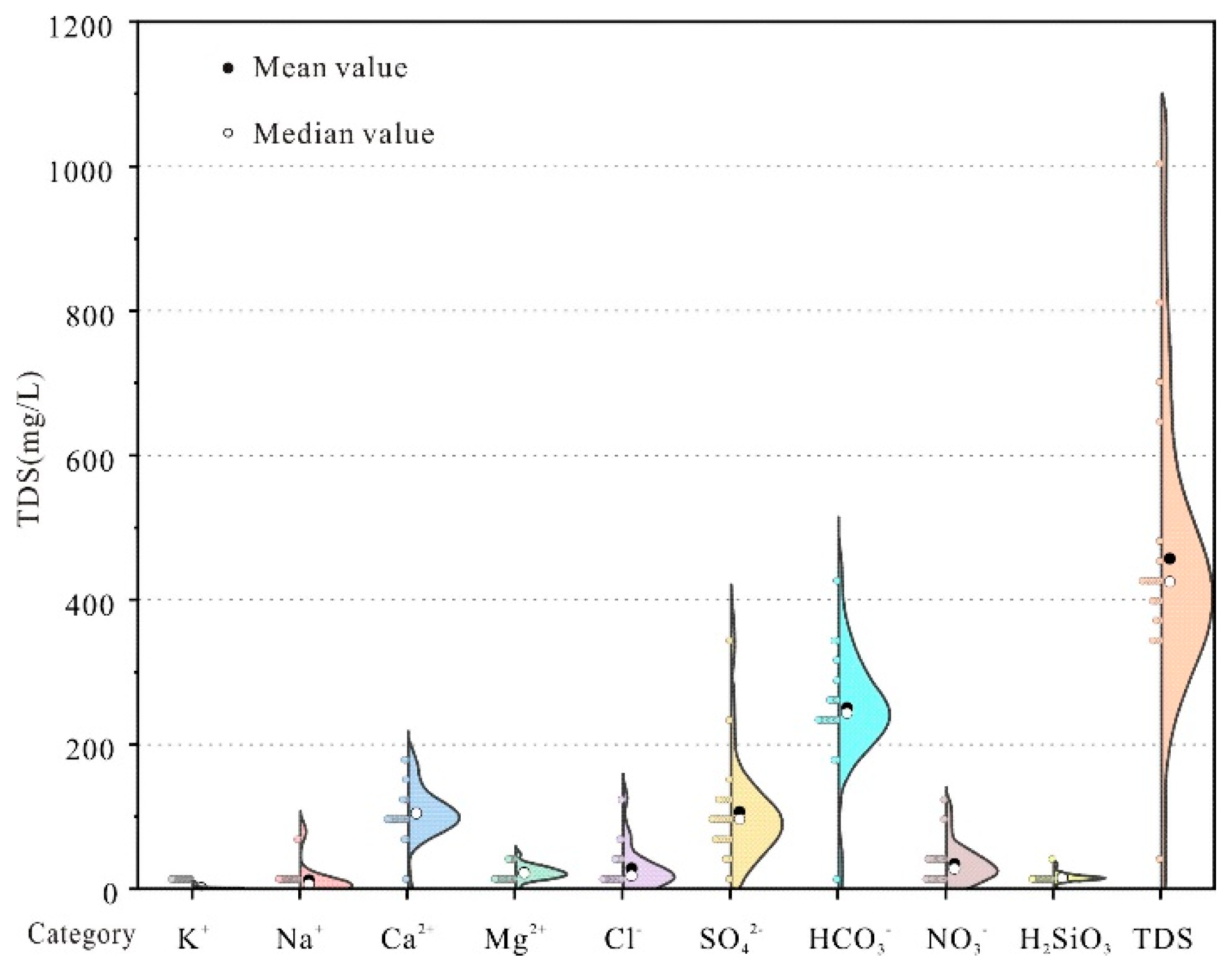

A statistical analysis of major ion concentrations in typical karst springs of the Laiwu Basin is presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 2. Except for pH, all hydrochemical parameters exhibit coefficients of variation (Cv) exceeding 20%, indicating moderate to high dispersion in the dataset. The springs are generally weakly alkaline, with pH values ranging from 7.10 to 8.20 (mean: 7.62). Total dissolved solids (TDS) for most springs are below 500 mg/L (mean: 481.17 mg/L), classifying them as freshwater, except for the Shangquan Spring Group (S11) and Huashui Spring (S20). The solute concentration hierarchy follows: HCO₃⁻ > SO₄²⁻ > Ca²⁺ > Cl⁻ > NO₃⁻ > Mg²⁺ > H₂SiO₃ > Na⁺ > K⁺ (

Figure 2). Anions are dominated by HCO₃⁻, accounting for 55.02% of total anions, followed by SO₄²⁻ and Cl⁻. Among cations, Ca²⁺ predominates, contributing 71.52% of total cations, with Mg²⁺ as the secondary component.

Quality assessment of conventional parameters (TDS, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻–N, Na⁺, and pH) was conducted against the Class III water quality thresholds of the Chinese National Standard for Groundwater Quality (GB/T 14848-2017) [

18], which applies to centralized drinking water sources and industrial/agricultural uses. Results show that all spring samples, except Huashui Spring (S20), meet Class III standards, with NO₃⁻–N concentration (ρ) in S20 exceeding the 20 mg/L limit. Evaluation using the World Health Organization (WHO) drinking water guidelines [

19] reveals the following: SO₄²⁻ exceeds the limit in S20 (exceedance rate: 5%). NO₃⁻ surpasses thresholds in S05, S07, S11, S12, S17, and S20 (exceedance rate: 30%) (

Table 1).

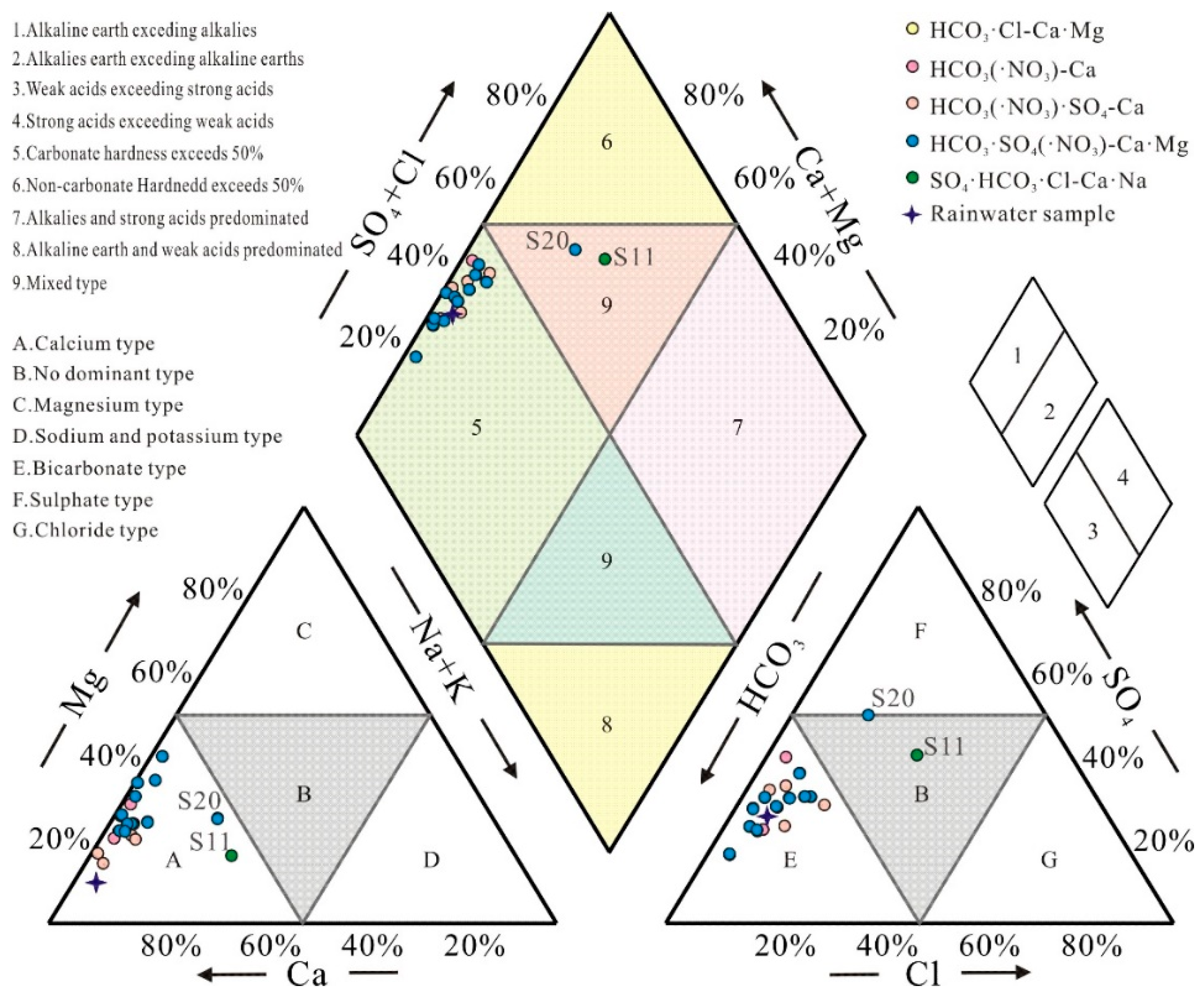

4.3. Hydrochemical Types of Groundwater

The Piper trilinear diagram is a widely used tool for understanding the major ion composition and hydrochemical evolutionary characteristics of karst spring water [

20]. The Piper diagram consists of three primary fields that plot the relative proportions of cations and anions in groundwater to assess hydrochemical facies. As shown in

Figure 3, the karst spring samples are predominantly distributed in Zones 5 (all except S11 and S20) and Zone 9 (S11 and S20). The results indicate that the karst springs are primarily classified as: HCO₃·SO₄-Ca·Mg type (50%), HCO₃·SO₄·NO₃-Ca·Mg type (10%), and HCO₃·SO₄-Ca type (20%). The cation and anion compositions of groundwater samples are concentrated in Fields E (alkaline earth metals, Ca²⁺ + Mg²⁺) and A (weak acids, HCO₃⁻), respectively, confirming that the dominant ions in the study area are HCO₃⁻ and Ca²⁺. This suggests that carbonate mineral weathering (e.g., calcite and dolomite) is likely the primary factor controlling the hydrochemical characteristics of the karst springs. Approximately 90% of the samples fall into the HCO₃-dominant water type, reflecting control by carbonate weathering in groundwater. The remaining samples are classified as SO₄-type (S20) and mixed-type (S11), implying influences from evaporative dissolution and anthropogenic inputs in these locations. For most karst spring samples, alkaline earth metals (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺, Field 1) and weak acids (HCO₃⁻, Field 3) dominate over alkali metals (Na⁺ and K⁺, Field 2) and strong acids (SO₄²⁻ + Cl⁻, Field 4). The elevated concentrations of alkaline earth metals and weak acid anions are attributed primarily to the weathering of calcite and dolomite.

4.4. Cause Analysis of Hydrochemical Characteristics

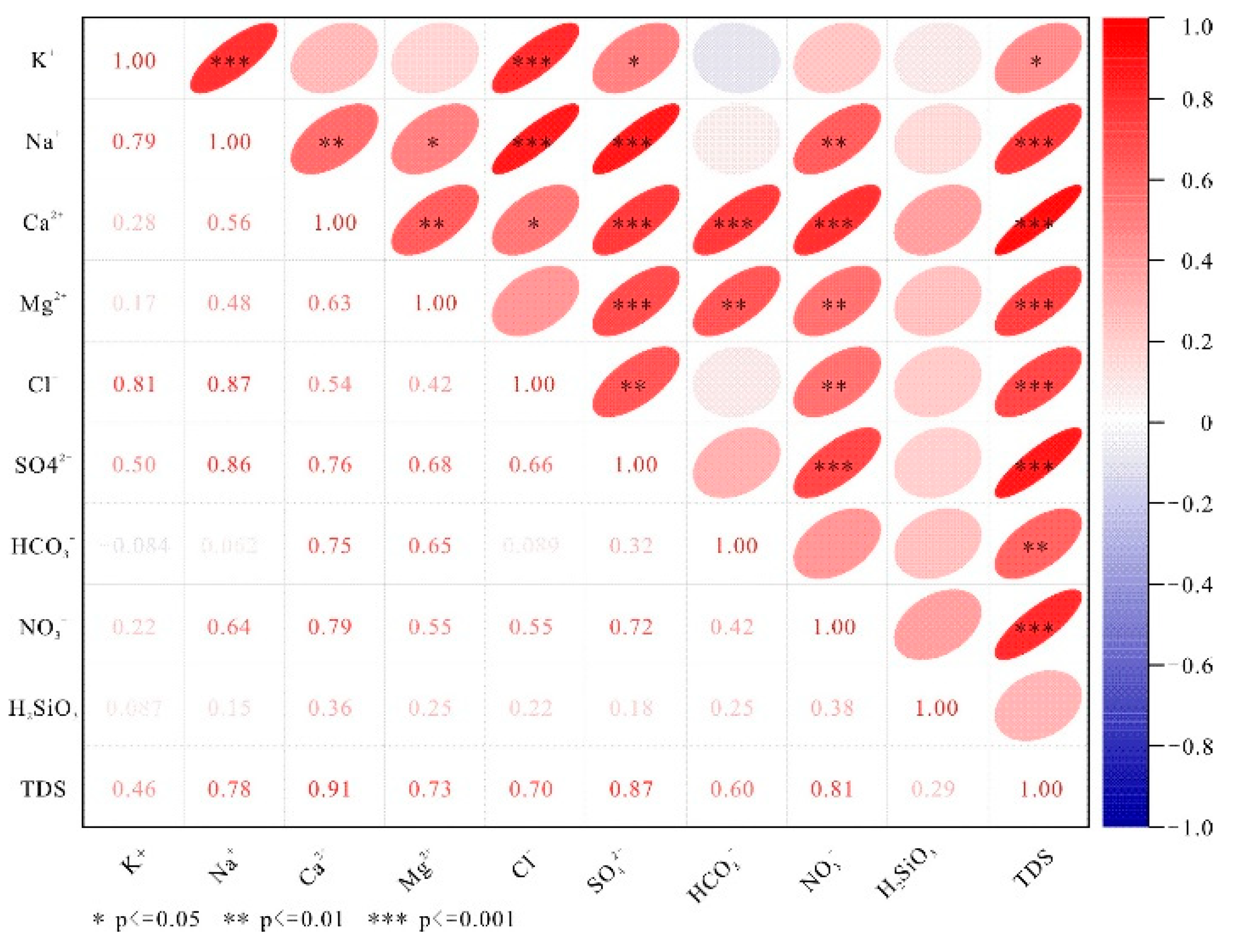

4.4.1. Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis of hydrochemistry is commonly used to reveal the source relationships between ions [

21]. Typically, correlation coefficient values R > 0.75 and 0.75 > R > 0.5 indicate significant and moderate correlations between hydrochemical parameters, respectively. A P-value < 0.001 signifies strong certainty of the correlation coefficient, while 0.001 < P < 0.05 represents moderate certainty [

22]. The heatmap of correlation relationships among chemical components in typical karst spring water from the study area (

Figure 4) reveals that Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Cl⁻, SO₄²⁻, and NO₃⁻ in karst water exhibit significant positive correlations with TDS (P < 0.001). Notably, Ca²⁺, NO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻ show correlation coefficients above 0.80, indicating their predominant contribution to spring water TDS. Cl⁻ demonstrates significant positive correlations with K⁺ and Na⁺ (R > 0.80, P < 0.001). Moderate positive correlations (R > 0.60) are observed between SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻ and Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, suggesting that the sources of Cl⁻, K⁺, and Na⁺ may be associated with atmospheric precipitation and halite dissolution [

23], while the dissolution of calcite and dolomite minerals involving carbonic and sulfuric acids contributes to the sources of SO₄²⁻, HCO₃⁻, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺ in karst water [

24]. The positive correlation between NO₃⁻ and Cl⁻ (R = 0.55, P < 0.01) in karst water implies their common origin, reflecting the impact of human activities on groundwater chemical composition.

4.4.2. Natural Factors

Lixiviation primarily refers to the water-rock interaction between groundwater and surrounding media, leading to certain changes in the hydrochemical components of groundwater [

25]. The Gibbs diagram is commonly used to qualitatively assess the influence of atmospheric precipitation, rock weathering, and evaporation-crystallization processes on the sources of groundwater ions [

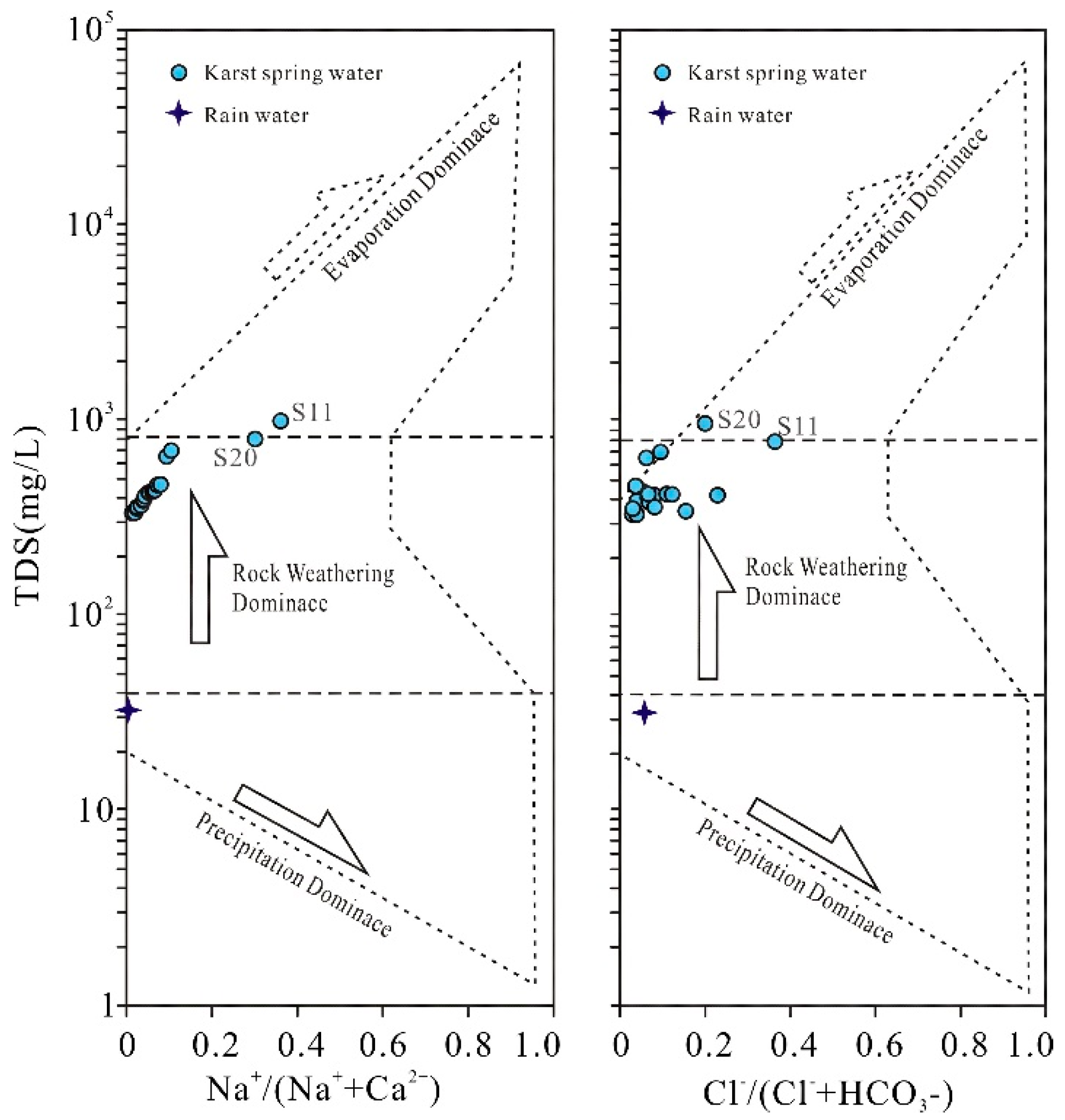

26,

27,

28]. As shown in

Figure 5, all spring water samples are clustered in the middle region of the TDS versus cation concentration ratio [ρ(Na⁺)/ρ(Na⁺+Ca²⁺)] and anion concentration ratio [ρ(Cl⁻)/ρ(Cl⁻+HCO₃⁻)] relationships, all plotting within the "rock weathering" end-member. This indicates that rock weathering serves as the dominant controlling factor for the source of major ion composition in karst spring water. In

Figure 5, sample points are distinctly distant from both the "atmospheric precipitation" and "evaporation-crystallization" end-members, demonstrating that atmospheric precipitation contributes minimally to the ionic sources of karst spring water, and evaporation-crystallization processes similarly do not constitute the primary genesis of major ions in the spring water.

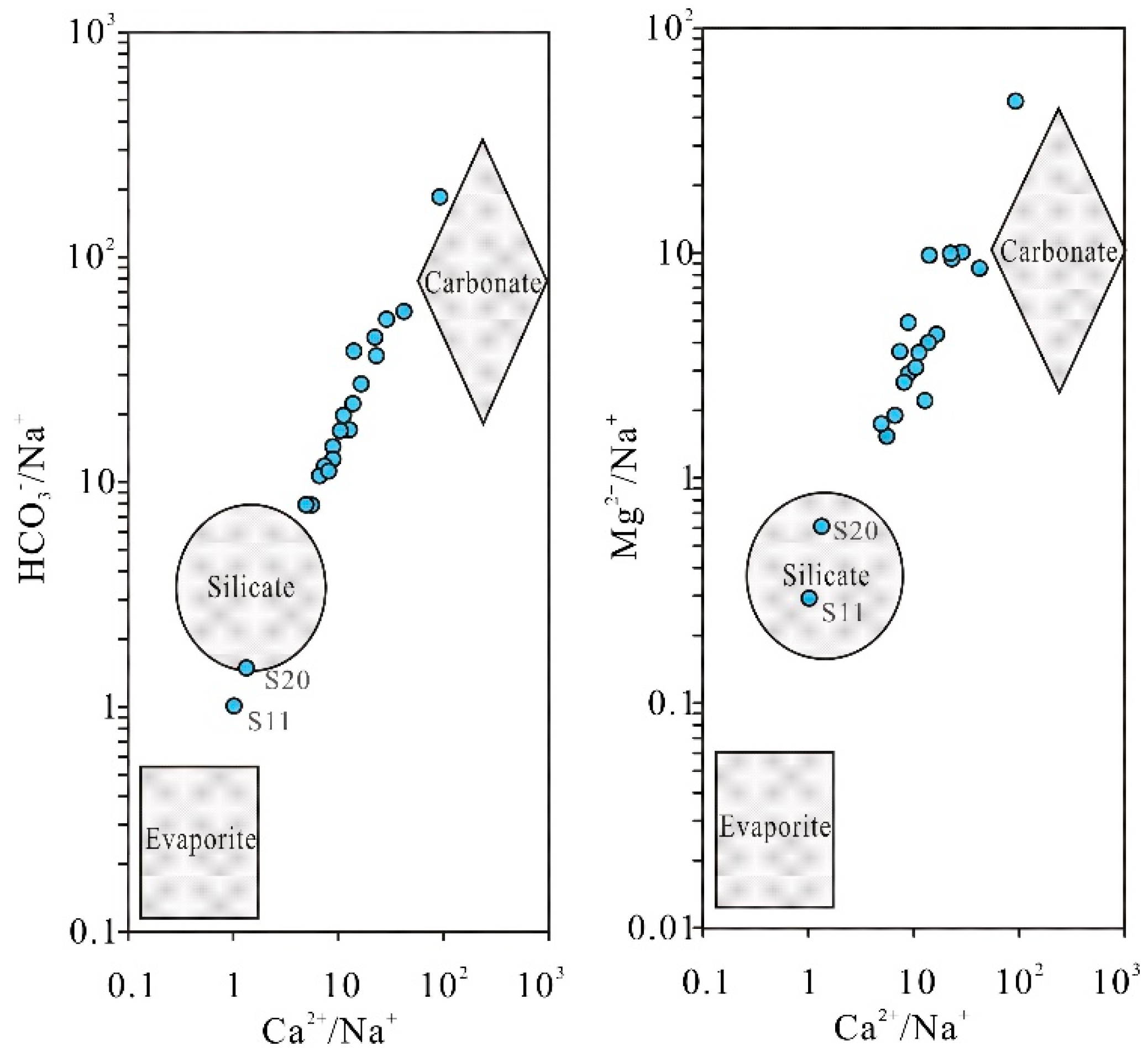

The molar ratios of n(Ca²⁺)/n(Na⁺), n(Mg²⁺)/n(Na⁺), and n(HCO₃⁻)/n(Na⁺) in groundwater are unaffected by flow velocity, dilution, or evaporation processes. These ratios are commonly employed to qualitatively identify the influence of carbonate rock, silicate rock, and partial evaporite weathering on groundwater solutes through variations in the relationships between n(HCO₃⁻)/n(Na⁺) versus n(Ca²⁺)/n(Na⁺) and n(Mg²⁺)/n(Na⁺) versus n(Ca²⁺)/n(Na⁺) [

29,

30]. As shown in

Figure 6, except for samples S11 and S20 located near the silicate rock weathering end-member, all other karst spring water samples cluster between the silicate rock weathering and carbonate rock weathering control end-members, with most distributed proximal to the carbonate weathering domain. This indicates that both silicate and carbonate rock weathering jointly contribute to solute formation in the springs, with carbonate weathering acting as the dominant control. This phenomenon correlates with the fact that the karst springs are hosted in carbonate aquifers, while S11 and S20 are influenced by the extensively exposed metamorphic rocks distributed in the upstream basin periphery.

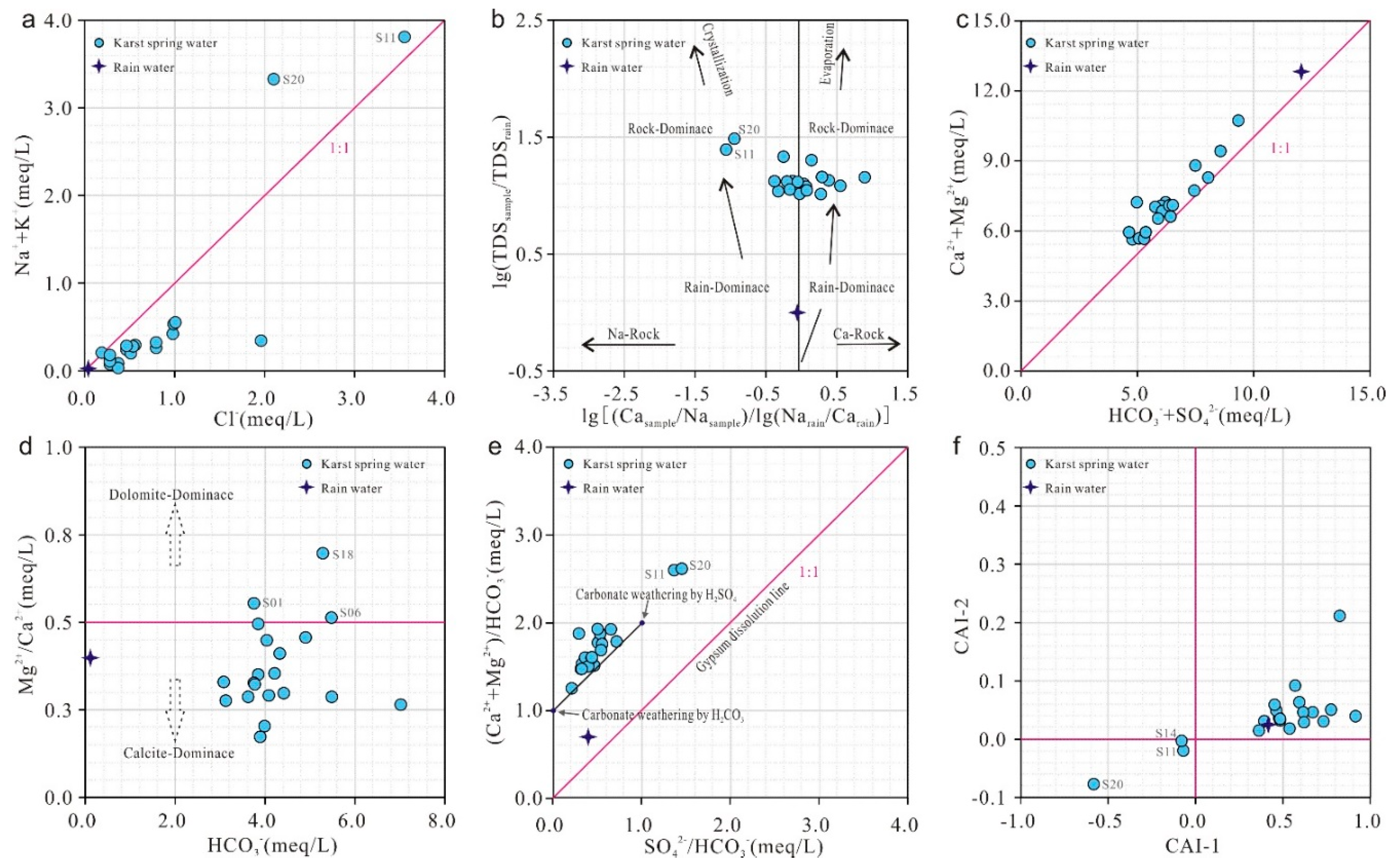

The milliequivalent ratio γ(Na⁺+K⁺)/γ(Cl⁻) can be used to identify the primary sources of Na⁺ and K⁺ in water. Halite dissolution typically yields γ(Na⁺+K⁺)/γ(Cl⁻) = 1. As shown in

Figure 7(a), nearly all spring water samples plot below the halite dissolution line, indicating that groundwater is influenced not only by halite dissolution but also by other processes causing Na⁺+K⁺ depletion.

Using atmospheric precipitation as a baseline, the logarithmic relationship model between ρ(Ca²⁺)/ρ(Na⁺) (ionic concentration) and TDS is commonly employed to evaluate factors controlling hydrochemical evolution in groundwater [

31,

32]. Three rainwater samples collected from the Laiwu Basin yielded average TDS, ρ(Ca²⁺), and ρ(Na⁺) values of 32.49, 4.98, and 0.28 mg·L⁻¹, respectively. These baseline values were combined with groundwater test results to establish the lg(Ca²⁺/Na⁺) vs. lg(TDS) relationship model. In

Figure 7(b), most samples fall within the rock weathering zone, consistent with the Gibbs diagram analysis (

Figure 5). Notably, samples S11 and S20 are distinctly influenced by sodium-rich rock weathering in Paleogene clastic rocks and Yanshanian diorite, respectively.

The milliequivalent ratio γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻+SO₄²⁻) is often used to analyze the sources of Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, HCO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻ in groundwater. If hydrochemical samples plot along the 1:1 line in a γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻+SO₄²⁻) diagram, it suggests that these ions are entirely derived from carbonate weathering and evaporite dissolution (e.g., gypsum layers in the Majiagou Group) [

33]. As shown in

Figure 7(c), nearly all samples cluster near the 1:1 line but exhibit a weak surplus of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺, indicating that while carbonate weathering remains the dominant source of HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺ in the studied springs, additional processes (e.g., silicate weathering or cation exchange) likely contribute to the formation and slight excess of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺.

To determine the contribution of carbonate mineral dissolution (calcite and dolomite) to the major ionic composition of water, the γ(Mg²⁺)/γ(Ca²⁺) vs. γ(HCO₃⁻) model is typically employed. When only dolomite dissolves, γ(Mg²⁺)/γ(Ca²⁺) = 1; when only calcite dissolves, γ(Mg²⁺)/γ(Ca²⁺) = 0; and when both minerals participate, γ(Mg²⁺)/γ(Ca²⁺) = 0.5 [

34]. As shown in

Figure 7(d), all samples except S01, S06, and S18 plot below the 0.5 ratio, indicating that calcite – the dominant mineral in Cambrian and Ordovician carbonate rocks – serves as the primary component of carbonate dissolution in the region.

The milliequivalent ratios γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻) and γ(SO₄²⁻)/γ(HCO₃⁻) are commonly used to analyze the involvement of carbonic acid (H₂CO₃) and sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) in carbonate dissolution. For pure carbonic acid-driven dissolution, γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻) = 1 and γ(SO₄²⁻)/γ(HCO₃⁻) = 0, whereas pure sulfuric acid-driven dissolution yields γ(SO₄²⁻)/γ(HCO₃⁻) = 1 and γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻) = 2 [

35]. In

Figure 7(e), most samples plot between the carbonic and sulfuric acid end-members, with all points distant from the gypsum dissolution line. This demonstrates minimal evaporite weathering influence on groundwater ions, with Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, HCO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻ predominantly originating from carbonate dissolution mediated by both acids. Notably, samples S11 and S20 deviate from the sulfuric acid end-member and exhibit γ(Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺)/γ(HCO₃⁻) > 2, consistent with

Figure 7(c), suggesting additional Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ sources beyond carbonate dissolution. Combined with

Figure 6 findings, this surplus likely arises from weathering of calcium-magnesium silicate minerals in magmatic and metamorphic rocks distributed along the periphery of the Laiwu Basin. For instance, sulfuric acid-mediated silicate weathering may generate excess Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ via reactions such as:

As shown in

Figure 7(a,c), nearly all samples exhibit significant Na⁺+K⁺ depletion and Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺ surplus. Such phenomena can result from cation exchange between adsorbed cations on soil/rock surfaces and dissolved cations in groundwater. The Chloro-Alkaline Indices (CAI-1 and CAI-2) are used to determine the direction and intensity of cation exchange. When Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ in groundwater replace Na⁺ and K⁺ in aquifer minerals (reverse cation exchange), CAI-1 and CAI-2 yield negative values. Conversely, when Na⁺ and K⁺ in groundwater replace Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ in aquifer minerals (forward cation exchange), CAI-1 and CAI-2 yield positive values [

36]. The indices are calculated as follows:

From the relationship between Chloro-Alkaline Indices and TDS [

Figure 7(f)], all spring water samples except S11, S20, and S14 show positive CAI values, indicating dominant reverse cation exchange in the study area. In this process, Na⁺ and K⁺ in groundwater replace Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ in carbonate aquifer minerals (Equation 5), leading to decreased Na⁺+K⁺ and increased Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺ concentrations. Conversely, samples S11, S20, and S14 exhibit negative CAI values, reflecting forward cation exchange (Equation 6), where Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ are replaced by Na⁺ and K⁺, resulting in elevated Na⁺+K⁺ and reduced Ca²⁺+Mg²⁺ levels.

4.4.3. Saturation Index (SI)

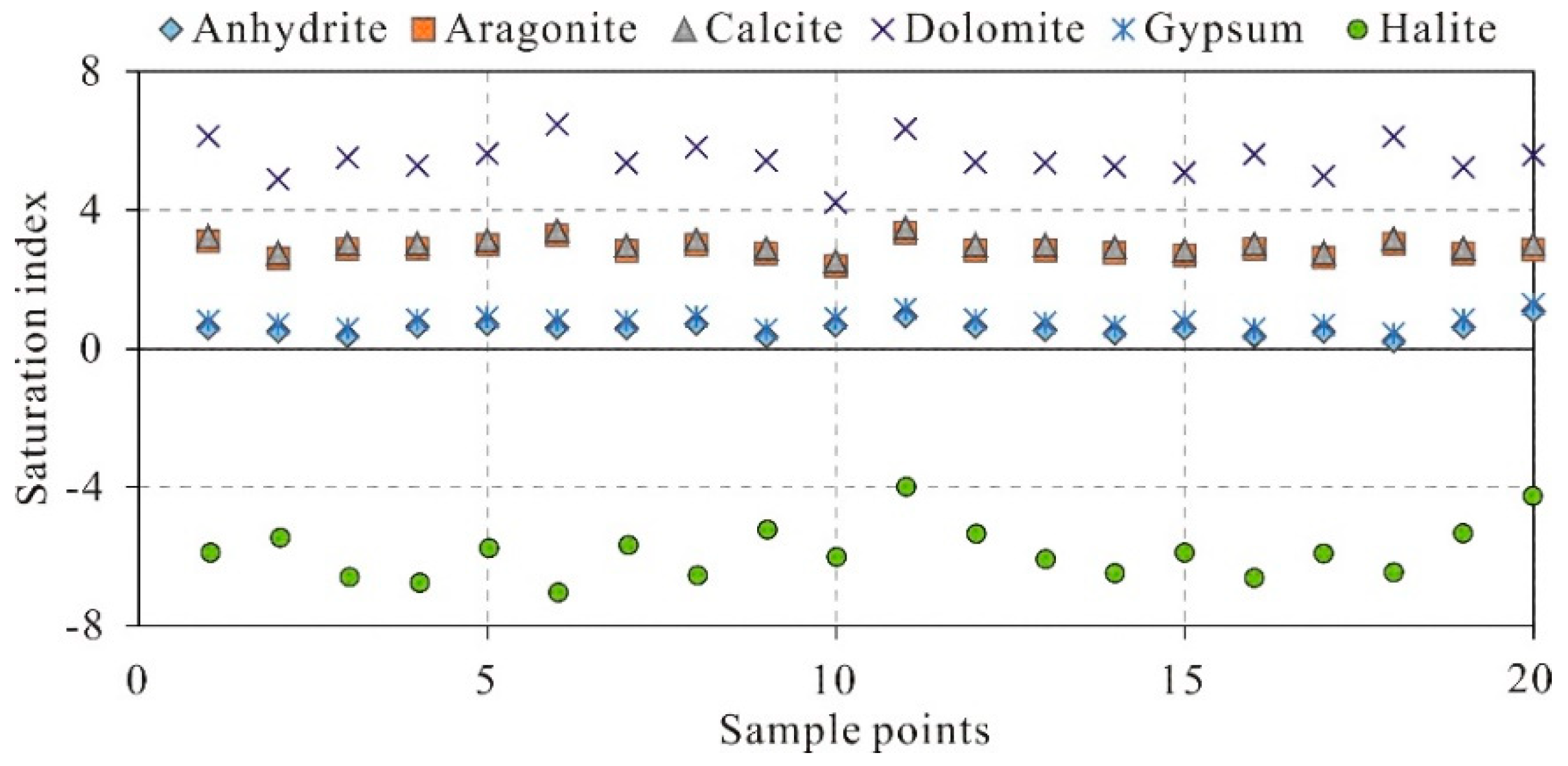

The mineral saturation index (SI) serves as a critical parameter in hydrogeochemical studies to assess the equilibrium state between groundwater and minerals. When SI = 0, the water-mineral system reaches dissolution equilibrium; when SI > 0, the mineral is supersaturated and may precipitate; when SI < 0, the mineral is undersaturated and likely to continue dissolving [

37]. In this study, the PHREEQC software was employed to calculate saturation indices of various minerals in karst spring water samples. As shown in

Figure 8, dolomite, calcite, and aragonite in all samples are in a supersaturated state, indicating that carbonate minerals tend to precipitate from groundwater. Gypsum and anhydrite approach saturation, suggesting that sulfate minerals may also undergo precipitation. Halite remains far below saturation levels, implying a persistent dissolution trend of salt minerals in groundwater, likely due to their limited abundance in the aquifer.

4.4.4. Human Activity

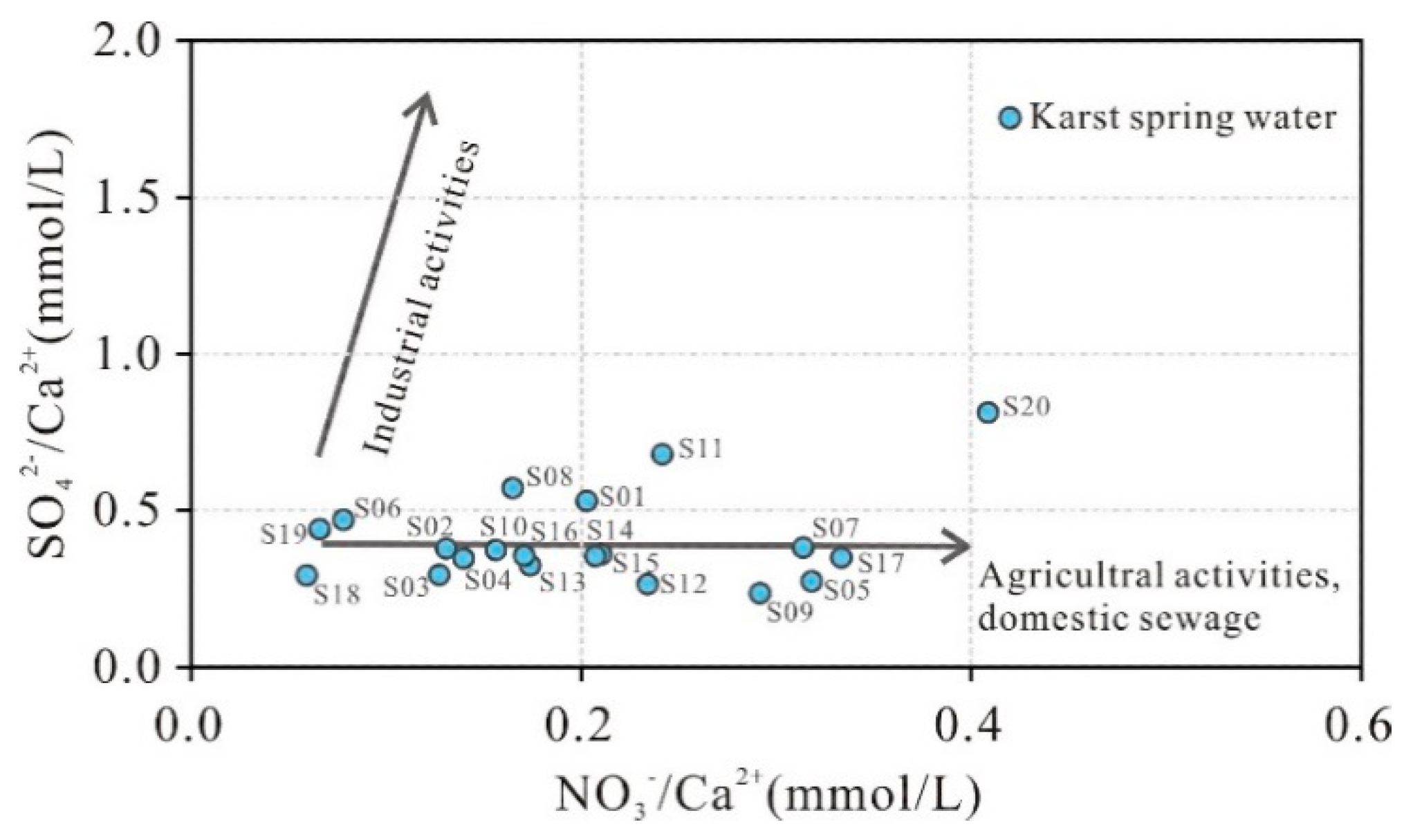

Nitrate, chloride, and sulfate are typically sensitive indicators of anthropogenic pollutants, and their ionic ratios can be utilized to investigate human impacts on groundwater chemistry [

38]. Studies suggest that when groundwater chemistry is dominantly governed by rock weathering (with carbonate rocks as the primary source of Ca²⁺), the relationships between n(NO₃⁻)/n(Ca²⁺) and n(SO₄²⁻)/n(Ca²⁺) can reveal anthropogenic influences on karst spring water [

39]. As shown in

Figure 9, most springs exhibit n(SO₄²⁻)/n(Ca²⁺) ratios ranging from 0.25 to 0.60 and n(NO₃⁻)/n(Ca²⁺) ratios between 0.10 and 0.30, indicating significant contamination from domestic sewage and agricultural activities, particularly in samples S11, S20, and S17 located near residential areas.

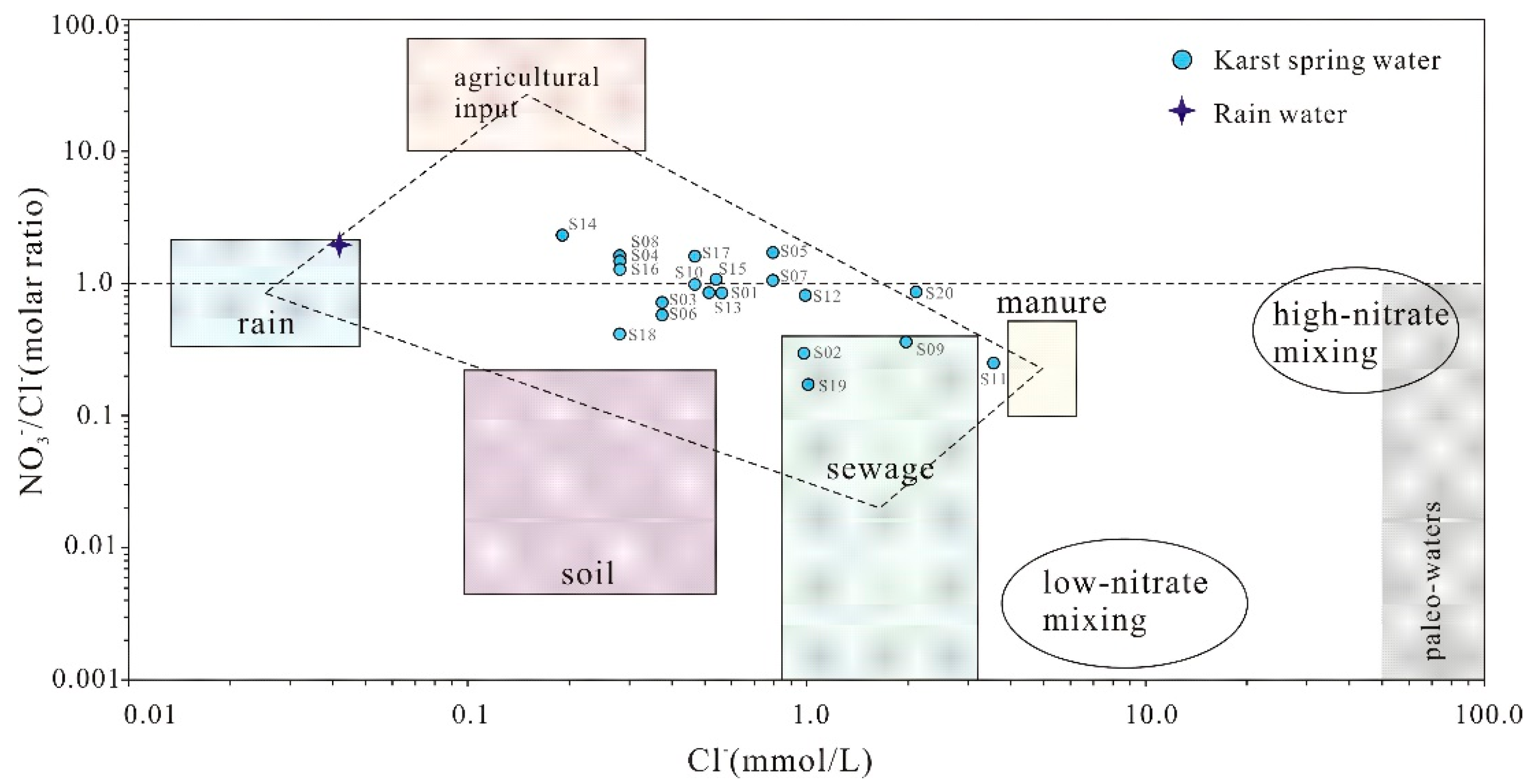

Further analysis of the n(Cl⁻) vs. n(NO₃⁻)/n(Cl⁻) relationships [

40] demonstrates that nearly all karst spring samples cluster within the domain bounded by "agricultural activities", "manure", "domestic sewage" and "precipitation" end-members, with minimal influence from precipitation (

Figure 10). This confirms that urban wastewater, agricultural practices, and manure collectively shape the hydrochemical composition of the springs. Notably, samples S02, S09, and S19 show strong impacts from domestic sewage, while S11 and S20 are predominantly influenced by manure contamination.

4.4.5. Isotopic Characteristics

Hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes (δD and δ

18O), integral components of natural water molecules, have been widely employed in tracing regional groundwater recharge sources and hydrochemical evolution since the early 1950s [

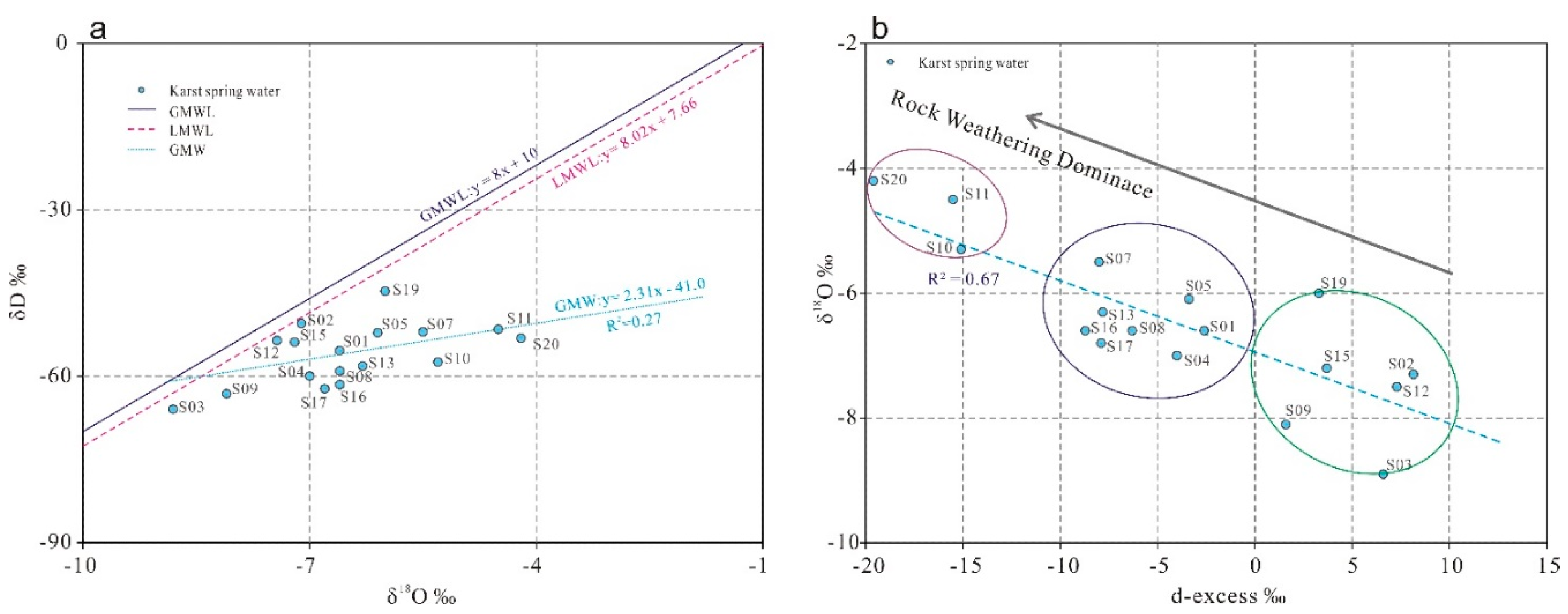

41]. In 2021, isotopic sampling and analysis were conducted on 17 representative karst springs in the Laiwu Basin. The δD vs. δ

18O scatter plot (

Figure 11a) reveals a regression line (GWM: δD = 2.31δ

18O-41.0) with a weak positive correlation (R=0.27). All samples plot below both the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL: δD = 8.0δ

18O + 10) [

42] and the Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL: δD = 8.02δ

18O + 7.66) [

43], showing noticeable deviations. This pattern indicates that atmospheric precipitation underwent evaporative fractionation during its recharge process into the karst aquifer system.

To effectively and accurately characterize groundwater circulation patterns, combined analysis with deuterium excess (d-excess, defined as d = δD – 8.0δ¹⁸O) is essential. Typically, d-excess < 10‰ reflects not only evaporation effects on atmospheric precipitation but also widespread water-rock interactions involving oxygen isotope exchange. Prolonged groundwater residence time enhances oxygen isotope exchange, resulting in lower d-excess values [

44]. As shown in

Figure 11b, the d-excess values exhibit distinct spatial variations: Samples S20, S11, and S10 located in the northern part of the basin show d-excess values less than -15, indicating that after atmospheric precipitation recharges the spring water, it undergoes prolonged residence time in the aquifer with intense water-rock interactions. Six southern samples (S03, S15, etc.) in the basin display d-excess values between 0 and 10, suggesting shorter aquifer residence times, weaker water-rock interactions, and smoother runoff pathways after atmospheric recharge. The remaining samples exhibit d-excess values between -10 and 0, reflecting moderate residence times and water-rock interactions. This spatial differentiation may be attributed to differences in groundwater recharge elevations between the northern and southern basin areas and the mixing of multiple water sources during runoff processes [

15].

4.5. Genetic Model of the Karst Springs

Based on the classification of karst spring types, recharge sources, hydrochemical characteristics, and deuterium-oxygen isotopic signatures obtained from the aforementioned research, combined with previous analyses of the genetic mechanisms of karst groundwater in the Laiwu Basin of the Central Shandong Mountains [

15], the genetic mechanisms of karst springs and hydrochemical components in the study area are summarized as follows: In the southern basin, the groundwater-bearing formations exhibit distinct temporal and lithological variations from south to north. The lithology transitions sequentially from Archean metamorphic granites in the recharge area, through Cambrian carbonate rocks interbedded with clastic rocks in the recharge-flow area, to Ordovician carbonate rocks in the discharge area. The karst aquifer receives recharge from atmospheric precipitation and bedrock fissure water in the southern metamorphic rock area. The groundwater flow direction aligns with the dip direction of the strata, while the significant topographic elevation difference creates a steep hydraulic gradient and unobstructed flow pathways. Overall, karst groundwater flows northward through exposed Cambrian carbonate-clastic interbeds and Ordovician carbonate rocks before discharging into the Muwen River. During this process, Type ③ springs form due to water-blocking effects from metamorphic bedrock, Type ① springs develop through Cambrian clastic rock aquicludes, Type ② springs originate from fault-induced water blocking, and Type ④ springs emerge from Yanshanian diorite intrusion barriers. Additionally, groundwater chemistry evolves through water-rock interactions and receives inputs from southern mountainous agricultural activities and urban domestic sewage in Laiwu City (

Figure 12).

In the northern basin, the aquifer system demonstrates relative lithological homogeneity, transitioning from Archean metamorphic granites in the recharge-flow area to Cambrian carbonate-clastic interbeds and Ordovician carbonate rocks in the discharge area. Influenced by subdued topography, karst groundwater migrates slowly southward against the strata dip direction through dissolution fractures in Cambrian and Ordovician carbonate rocks under gravitational drive. Type ② springs form through fault-controlled water blocking mechanisms. The hydrochemical evolution involves water-rock interactions combined with influences from northern mountainous agricultural practices and limited domestic wastewater from rural settlements (

Figure 12).

5. Conclusions

In this study, Piper diagrams, Gibbs diagrams, ionic ratios, factor analysis, and stable isotopes were employed to investigate the genetic mechanisms, hydrochemical characteristics, and influencing factors of karst springs in the Central Shandong Mountains. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

(1) Based on the geological structural characteristics of the Laiwu Basin, the controlling factors of karst spring formation were categorized into three aspects: faults, rock masses, and lithology. Consequently, the genetic types of major karst springs in the basin can be classified into four categories: lithological barriers, fault-induced water blocking, basement rock barriers, and intrusive rock barriers. The spatial distribution of these spring types varies across the basin.

(2) The dominant hydrochemical type of karst springs in the Laiwu Basin is Ca·Mg-HCO₃·SO₄, with weakly alkaline freshwater properties. Among anions, HCO₃⁻ predominates, accounting for 55.02% of total anion concentration, while Ca²⁺ dominates cations, constituting 71.52% of total cation concentration.

(3) Dissolution of calcite-dominated carbonate rocks serves as the primary source of HCO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺, whereas halite dissolution contributes predominantly to Na⁺ and K⁺. Reverse cation exchange adsorption explains the weak enrichment of Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ and depletion of Na⁺ and K⁺ in karst spring waters. Urban domestic sewage, agricultural activities, and manure fertilization influence hydrochemical compositions, with samples S02, S09, and S19 showing strong urban sewage impacts and S11 and S20 exhibiting pronounced manure-derived influences.

(4) All δD and δ¹⁸O values of karst spring waters plot below the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) and Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL), confirming atmospheric precipitation as the primary recharge source. Evaporative fractionation occurred to varying degrees during infiltration.

(5) Differences in topographic relief, aquifer lithology, structural attitude, and fault development result in distinct water-rock interaction intensities between northern and southern basin groundwater during flow. This is reflected in the deuterium excess (d-excess) values, which exhibit significant spatial differentiation, with higher d-excess values observed in southern basin springs compared to northern counterparts.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Writing—review and editing; L.Z.: Writing—original draft; X.M.: Analyzed the chemistry data; W.L.: Project Administration; D.W. and Z.S.: Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Geological Survey, grant number [DD20230424].

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Darnault, C.J. Karst aquifers: hydrogeology and exploitation. Nato Security Through Science 2011, 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang,Z.H.; Li, L.R. Groundwater resources in China;China Cartographic Publishing House,Beijing,China,2004.

- Liang, Y.P.; Wang,W.T.; Zhao,H.H.; Wang, W.;Tang, C.L. Variations of karst water and environmental problems in North China.Carsologica Sinica,2013 32(1):34-42.

- Hao,Y.H.; Wang, Y. J.; Zhu, Y.;Lin,Y.; Wen, J.C.;Tian,C.J.Y. Response of karst springs to climate change and anthropogenic activities: the Niangziguan Springs, China. Progress in Physical Geography,2009 33(5):634-649.

- Huo,X.L.; Liu, Z.F.; Duan, Q.Y.;Hao, P.M.;Zhang Y.Y.; Hao Y.H.; Zhan H.B. Linkages between Large-Scale Climate Patterns and Karst Spring Discharge in Northern China. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 2016 17:713-724.

- Nerantzaki,S.D.; Nikolaidis,N.P. The response of three Mediterranean karst springs to drought and the impact of climate change.Journal of Hydrology, 2020 591(3):125296.

- Yin, X.L.; Wang,Q.B.; Feng,W. Hydro-chemical and isotopic study of the karst spring catchment in Jinan. Acta Geologica Sinica, 2017 91(7):1651-1660.

- Zhao,C.H.; Liang,Y.P.; Lu, H.P.; Tang,C.L.; Shen,H.Y. Hydrogen and oxygen isotopic characteristics and influencing factors of karst water in the Niangziguan Spring Area. Geological Science and Technology Information, 2018 37(5):200-205.

- Wang, Z.H.; Liang,Y.P.; Shi,Z.M.; Zhang,S.T.; Zhao,Y.; Xie,H.; Zhao C.H.; Tang, C.L. Currentsituation of karst groundwater environmental problems and spring source protectioninthe Gudui-Nanliang spring basin. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology, 2023 42(5) :228-230.

- Wang,Y.X. Study on ecological restoration strategy of karst spring region in north China:Taking Jinci spring as an example. Carsologica Sinica,2022 41(3):331-344.

- Liang,Y.P.; Shen,H.Y; Gao,X.B. Review ofresearch progress of karst groundwaterin northern China. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology,2022 41(5) :199-219.

- Liu,Y.Q.; Zhou,L.; Ma,X.M.; Lv, L.; Zheng,Y.D.;, Li,W.; Meng,S.X. Evaluation on chemical characteristics and water quality of groundwaterin Feicheng Basin. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment,2020 34(11) :118-124.

- Tang, C.L.; Zhao,C.H.; Shen,H.Y; Liang, Y.P.;Wang,Z.L. Chemical Characteristics and Causes of Groups Water in Niangziguan Spring. Environmental Science,2021 42(3):1416- 1423.

- Gao,Z.J.; Wan,Z.P.; He,K.Q.; Victor, K.Z,; Liu,J.T. Hydrochemical characteristics and controlling factors of karst groundwater in middle and upperreaches of Dawen River basin. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology 2022,41(5): 264-272.

- Liu,Y.Q.; Wen,D.G.; Lv,L.; Li,W.;Zhang,F.C.; Wang,X.F.; Meng,S.X. Characteristics of karst groundwater flow systems of typical faulted basins in Yimeng Mountain area: A case study of Laiwu Basin. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology 2022,41(1):157-167.

- He,K.Q.; Liu,W.J.; Shao,C.F. The Comprehensive Type Classification and Proper Adjustment of Karst Water Resource in the Central-South Region of Shandong Province. Acta Geoscientica Sinica 2002,23(4):369-374.

- HTSGB. Hydrogeological Summary Report of Laiwu Basin, Hydrogeological Team of Shandong Geological Bureau: Jinan,China, 1974.

- NTCSLR, China. Standard for groundwater quality, GB/T 14848-2017; National Technical Committee for Standardization of Land and Resources: Beijing, China, 2017.

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao,Y.; Liu, K.; Hao, Q.C.; Xiao, D.; Zhu,Y.C.; Yin, S.Q.; Zhang, Y.H. Hydrogeochemical insights into the signatures, genesis and sustainable perspective of nitrate enriched groundwater in the piedmont of Hutuo watershed, China. Catena 2022,212:106020.

- Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou,L.; Lv,L.; Li,W.; Wang,X.F.; Zheng,Y.D.; Li,C.S. Hydrochemical characteristics and control factors of pore-water in the middle and upper reaches of Muwen River. Environmental Science 2023,44(3):1429-1439.

- Chander, K.S.; Anand, K.; Satyanarayan, S.; Alok,K.;Pankaj, K.; Javed,M. Multivariate statistical analysis and geochemical modeling for geochemical assessment of groundwater of Delhi, India. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2017,175:59-71.

- Zhang,T.; Cai,W.T.; Li,Y.Z.;, Zhang,Z.Y.; Geng,T.T.; Bian,C.;,Zhao,M.; Cai,Y.M. Major ionic features and their possible controls in the water of the Niyang River Basin. Environmental Science 2017,38(11):4537-4545.

- Liu, P.; Nils, H.; Carsten,D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z.Hydro-geochemical paths of multi-layer groundwater system in coal mining regions - Using multivariate statistics and geochemical modeling approaches. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 601-602:1-14.

- He, J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Zhao,Y.Q.; Han, S.B.; Liu,Y.Q.; Zhang,T. Hydrochemical characteristics and possible controls of groundwater in the Xialatuo Basin section of the Xianshui River. Environmental Science 2019,40(3): 1236-1244.

- Gibbs,R.J. Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry.Science 1970,17(3962):1088-1090.

- Li,Z.J.; Yang,Q.C.; Yang,Y.S.; Ma,H.; Wang, H.; Luo,J.N.; Bian, J.M.; Jordi, D.M. Isotopic and geochemical interpretation of groundwater under the influences of anthropogenic activities. Journal of Hydrogeology 2019,576:685-697.

- Andres,M.; Paul.S. Groundwater chemistry and the Gibbs Diagram. Applied Geochemistry 2018, 97:209-212.

- Gaillardet,J.; Dupre,B.; Louvat,P.;Allegre C.J. Global silicate weathering and CO2 consumption rates deduced from the chemistry of large rivers.Chemical Geology 1999,159(1-4):3-30.

- Gan,Y.Q.; Zhao,K.; Deng,Y.M.; Liang,X.; Ma,T.; Wang,Y.X. Groundwater flow and hydrogeochemical evolution in the Jianghan Plain, central China. Hydrogeology Journal 2018, 26(5): 1609-1623.

- Wu,Y.; Gibson,C.E. Mechanisms controlling the water chemistry of small lakes in northern Ireland.Water Research 1996, 30:178–182.

- Zhu,B.Q.; Yu,J.J.; Qin, X.G.; Patrick,R.;Xiong,H.G. Climatic and geological factors contributing to the natural water chemistry in an arid environment from watersheds in northern Xinjiang, China. Geomorphology 2012,153-154:102-114.

- Ma,R.; Wang,Y.X.; Sun,Z.Y.;Zheng, C.M.; Ma,T.;Prommer,H. Geochemical evolution of groundwater in carbonate aquifers in Taiyuan, northern China[J]. Applied Geochemistry 2011,26(5):884-897.

- Pu,J.B.;Yuan,D.X.;Xiao,Q.;Zhao,H.P. Hydrogeochemical characteristics in karst subterranean streams: a case history from Chongqing, China. Carbonates and Evaporites 2015, 30: 307-319.

- Xie, Y.T.; Hao, Y.P.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.L.; Xiao, Q.; Huang F.Influence of anthropogenic sulfuric acid on different lithological carbonate weathering and the related carbon sink budget: examples from Southwest China[J]. Water 2023,15,2933:1-21.

- Thakur,T.; Rishi, M.S.; Naik,P.K.; Sharma, P. Elucidating hydrochemical properties of groundwater for drinking and agriculture in parts of Punjab, India[J]. Environmental Earth Sciences 2016, 75(6):1-15.

- Gao, Z.J.; Liu, J.T.; Feng, J.G.; Wang, M.; Wu, G.W. Hydrogeochemical characteristics and the suitability of Groundwater in the alluvial-diluvial Plain of Southwest Shandong Province, China. Water 2019, 11, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan,B.L.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Tao, F.X.; Liu, B. J.; Tao, Z.H.; Gao, S.; Zhang,Z.H. Characteristics of carbonate, evaporite and silicate weathering in Huanghe River basin: A comparison among the upstream, midstream and downstream. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2014, 96:17-26.

- Pu, J.B.; Yuan,D.X.; Jiang,Y.J.;Gou,P.F.;Yin,J.J. Hydrogeochemistry and environmental meaning of Chongqing subterranean karst streams in China. Advances in water science 2010,21(5):628-636.

- Mohamed,O.A.; Tiziano, B.; Abdillahi, E. A.; Mahamoud, A.C.;Moussa, M.A.; Omar, A.D.;Youssouf, D.S.;Nima, M.E.; Ali, D.K.; Ibrahim, H.K.; Mohamed, C. Origin of nitrate and sulfate sources in volcano-sedimentary aquifers of the East Africa Rift System: An example of the Ali-Sabieh groundwater (Republic of Djibouti). Science of the Total Environment 2022,804,150072.

- Wen,D.G. Groundwater resources attribute based on environmental isotopes.Earth Science-Journal of China University of Geosciences 2002,27(2):141-147.

- Clark,I.D.; Fritz,P. Environmental isotopes in Hydrogeology .NewYork: Lewis Publishers,1997: 1-312.

- Liu,Y.Q.; Zhou,L.; Li,W.; Zhu,Q.J.;,Xu,M.;Lv,L.;Deng,Q.J.; He,J.; Wang,X.F.The Characteristics and Genetic Analysis of the Paleogene Semi- Consolidated Water-Bearing Formation on the Northwestern Margin of Laiwu Basin, Shandong Province. Acta Geoscientica Sinica 2018, 39(6): 737-748.

- Yin,G.;Ni,S.J.;Gao,Z.Y.;Shi,Z.M.;Yan,Q.S. Variation of isotope compositions and deuterium excess of brines in Sichuan Basin. J Mineral Petrol 2008,28(2):56-62.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).