6.1.5. Patients with Multiple Pathologies on Biopsy

● ATN + Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG)

● ATN + Minimal change disease (MCD)

● ATN + Membranous nephropathy (MN)

● ATN + IgA nephropathy

● ATN + Thrombotic microangiopathy

● ATN + CG + MN

● ATN + CG + IgA nephropathy.

● ATN + Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis

Glomerular diseases associated with COVID-19 are described under an entity called COVID-19 associated nephropathy (COVAN) [7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, glomerular diseases have been reported more frequently. This is due to immune dysregulation, autoantibody production, cytokine storm, complement activation and direct viral toxicity associated with COVID-19 infection which led to various forms of glomerular injuries [7]. Treatment of the glomerular diseases in the setting of active or recent COVID-19 infection is challenging as these diseases require immunosuppression [7].

In a review study conducted by Kudose et al on-kidney biopsy findings of patients with COVID 19 related kidney injury, patients with collapsing glomerulopathy and minimal change disease were found to have high risk APOL1 genotypes on genetic studies and electron microscopy showed endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions in 60% samples [8]. The presence of tubuloreticular inclusions indicate the role of interferon mediated injury in genetically susceptible individuals with covid 19 infection [8,9]. These inclusions, referred to as "interferon footprints," indicate a significant role for interferon in the kidney pathology associated with COVID-19 [7]. Despite extensive investigation using multiple distinctive methods, this study did not detect any viral particles within the kidney cells [8]. Even in patients with positive Covid -19 RT-PCR , immunohistochemical staining of the kidney biopsy samples and electron microscopy did not show any viral particles (SARS-CoV-2) in the kidney tissues [4].

PLA2R, expressed in the respiratory tract and the kidney, may trigger PLA2R-mediated Membranous nephropathy if the respiratory tract is infected by SARS-CoV-2. There are case reports describing the association of membranous nephropathy and COVID-19 infection, with elevated PLA2R titters observed in these cases. Biopsies from these patients have shown features of secondary membranous nephropathy and they have responded to immunosuppression [10].

Gobor et.al described a case of crescentic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis after receiving covid 19 vaccine in a patient with a previous history of chronic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. This patient responded well to aggressive immunosuppression which led to normalization of renal function and improvement in proteinuria. This report illustrates possibility of covid 19 vaccination triggering glomerular disease [11].

In a study conducted in South Korea by Kim et.al, the most common glomerular disease diagnosed after infection with covid 19 was podocytopathy with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and minimal change disease. Whereas post vaccination the most common glomerular diseases were IgA nephropathy, Henoch Schönlein purpura nephritis, few cases of Lupus Nephritis and Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Covid 19 infection and vaccination can lead to autoimmune glomerulonephritis through activation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Covid-19 vaccinations, particularly mRNA vaccines are believed to enhance immune reactions which can trigger the development of glomerulonephritis [12].

Winkler et.al reported a case of recurrent Anti glomerular Basement membrane disease in a patient following SARS-CoV-2 infection. This patient had negative serologies, but biopsy has shown fibro cellular crescents, segmental fibrinoid necrosis and linear IgG, IgM and C3 deposits along glomerular basement membrane. This patient was treated with plasma exchange, pulse steroids and Rituximab with a positive outcome. This case illustrates the possibility that COVID infection can reactivate pre-existing auto reactive T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes and activate the complement system leading to inflammation which leads to glomerular endothelial injury resulting in crescentic glomerulonephritis [13].

Ta et.al described a case of ANCA associated vasculitis with mucosal involvement in a patient recovering from COVID-19 pneumonia. This paper suggests that COVID-19 infection triggered autoimmunity through molecular mimicry, viral persistence, epitope spreading and formation of neutrophil extra cellular traps. These neutrophil extra cellular traps are formed by activated neutrophils which lead to endothelial injury, complement activation, production of P-ANCA and C ANCA which led to crescentic glomerulonephritis. They also suggest that the expression of neutrophil extracellular traps expression is increased in COVID-19 patients [14].

Pfister et.al studied kidney biopsies of patients with COVID-19 infection and discovered marked complement activation in the vascular beds and tubules. All 3 pathways of complement activation were observed in COVID-19 infection. Complement activation in kidneys was observed to be indirect rather than direct as viruses were not detected in kidney tissue by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry in the study. Complement C3 C and specifically C3d deposition was noted extensively in the tubules of patients with COVID infection and the intensity of staining correlated with the severity of COVID-19 infection. C5b-9 deposits were also detected and showed high intensity staining in COVID-19 infection patients. These findings highlight the role of complement related kidney injury in COVID-19 [15].

C3 glomerulopathy is due to dysregulation of alternate complement pathway mainly related to complement gene abnormalities. It is characterized by persistently low serum C3 and autoantibodies directed against various complement factors that can be detected in serum. It can present clinically with asymptomatic hematuria, proteinuria or severe glomerulonephritis and progress to ESRD. Biopsy shows 3+ staining for C3 either in form of sausage shaped deposits and thickening of basement membrane in dense deposit disease or as electron dense deposits in mesangial and subendothelial regions in C3GN. Biopsy picture is described as MPGN usually. Treatment response is usually poor but might respond to anti complement agents (anti C5a agent-Eculizumab) and MMF [20]. In comparison, covid related glomerulopathy is secondary to covid infection. Clinical presentation is usually variable. Excessive proteinuria is usually seen in cases of collapsing glomerulopathy, which is seen in cases of high risk APOL1 carriers. Biopsy findings are not consistent unlike in C3 glomerulopathy. ATN is the predominant finding in biopsy. Tubuloreticular inclusion bodies are noted in biopsies of Covid -19 associated kidney injury indicating interferon activity which is not seen in C3GN.Complement activation is secondary to infection and serum C3 levels eventually normalize unlike in C3 glomerulopathy. Biopsy shows C3 deposits usually in tubules, vascular beds and all 3 pathways of complement system are activated. Treatment is directed against covid-19 with antivirals.

Yilmaz et.al reported a case of an adolescent with biopsy proven IgA nephropathy and Alport syndrome who developed crescentic glomerulonephritis due to flare up of IgA nephropathy following COVID-19 infection. Despite immunosuppression with pulse steroids, it has progressed to end stage renal disease and became dialysis dependent. This paper describes that COVID-19 infection stimulates IL-6 production, leading to excess production of galactose deficient IgA1 and flares up IgA Nephropathy. Various cytokines released in response to COVID-19 infection stimulate maturation and proliferation of IgA1 producing B cells. Covid -19 vaccination like influenza vaccination stimulates production of IgA1 monomers leading to IgA nephropathy flare up [17].

Duran et al described cases of pauci immune glomerulonephritis (ANCA associated vasculitis) following Covid -19 infection which were successfully treated with pulse steroids, Cyclophosphamide and plasma exchange [19].

Klomjit et al describe managing Collapsing glomerulopathy, Membranous nephropathy, Crescentic IgA Nephropathy, Sero positive crescentic pauci immune glomerulonephritis, Anti GBM glomerulonephritis, Proliferative Glomerulonephritis with Monoclonal Immunoglobulin deposits which have presented in patients following covid-19 infection and were managed with various immunosuppressive regimens which included steroids, cyclophosphamide, Rituximab, Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus along with antivirals and Plex in few cases with varying outcomes [7].

Bell et al describe modifying immunosuppressive regimen in transplant patients to improve the outcomes. These include discontinuing or holding Mycophenolate and switching to a mechanistic target of rapamycin(mTOR) based regimen. Patients on CNI (calcineurin inhibitors), mTOR and prednisone regimen have shown better outcomes according to this paper [18]. Using various antivirals and monoclonal antibodies directed against Covid-19 virus early in the course of infection has been advocated in this paper [18]. Kronbichler et al proposed that in patients with COVID-19 infection with lymphopenia and kidney transplant recipients with severe COVID-19 infection, further suppressing the T-cell immunity with immunosuppressants should be avoided. Controlling the cytokine storm and inflammatory state with anti-IL-6 agents should be considered. Kidney transplant recipients on triple immunosuppression, should hold antiproliferative drugs to allow the immunity to fight the infection. Severe COVID-19 infections associated with severe lymphopenia could slow progression of immune mediated glomerular disease even if immunosuppression is discontinued or not initiated [21].

Management of COVID-19-related acute kidney injury (AKI) involves treating septic shock, adapting lung-protective ventilation strategies, controlling cytokine storms and using antiviral agents targeting SARS-CoV-2. Renal replacement therapy is in cases of hypervolemia causing refractory hypoxemia, acid-base disturbances, and electrolyte abnormalities. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) helps remove inflammatory molecules from the body and mitigate the cytokine storm [2]. Mortality rates in patients with COVID-19-related AKI correlate with viral load and AKI severity. Patients with pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) required renal replacement therapy more frequently and those with advanced CKD who developed AKI often continued maintenance dialysis after discharge [2].

Ueda et al. published a case series of five patients with biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy who developed gross hematuria within 48 hours of COVID-19 symptom onset, which lasted for one week. Acute kidney injury accompanied hematuria in some cases and notably, some patients had no prior history of gross hematuria despite having IgA nephropathy [16].

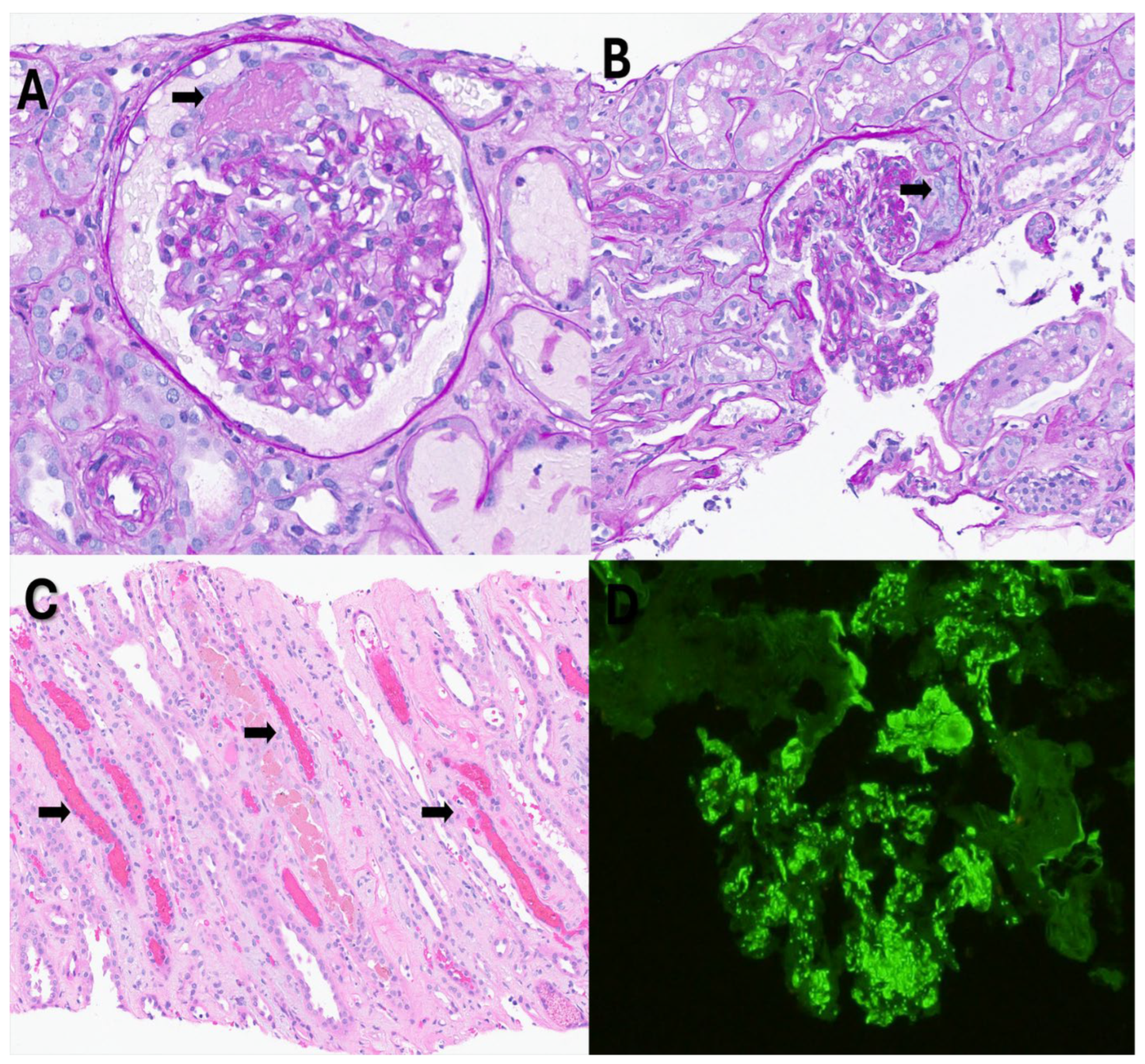

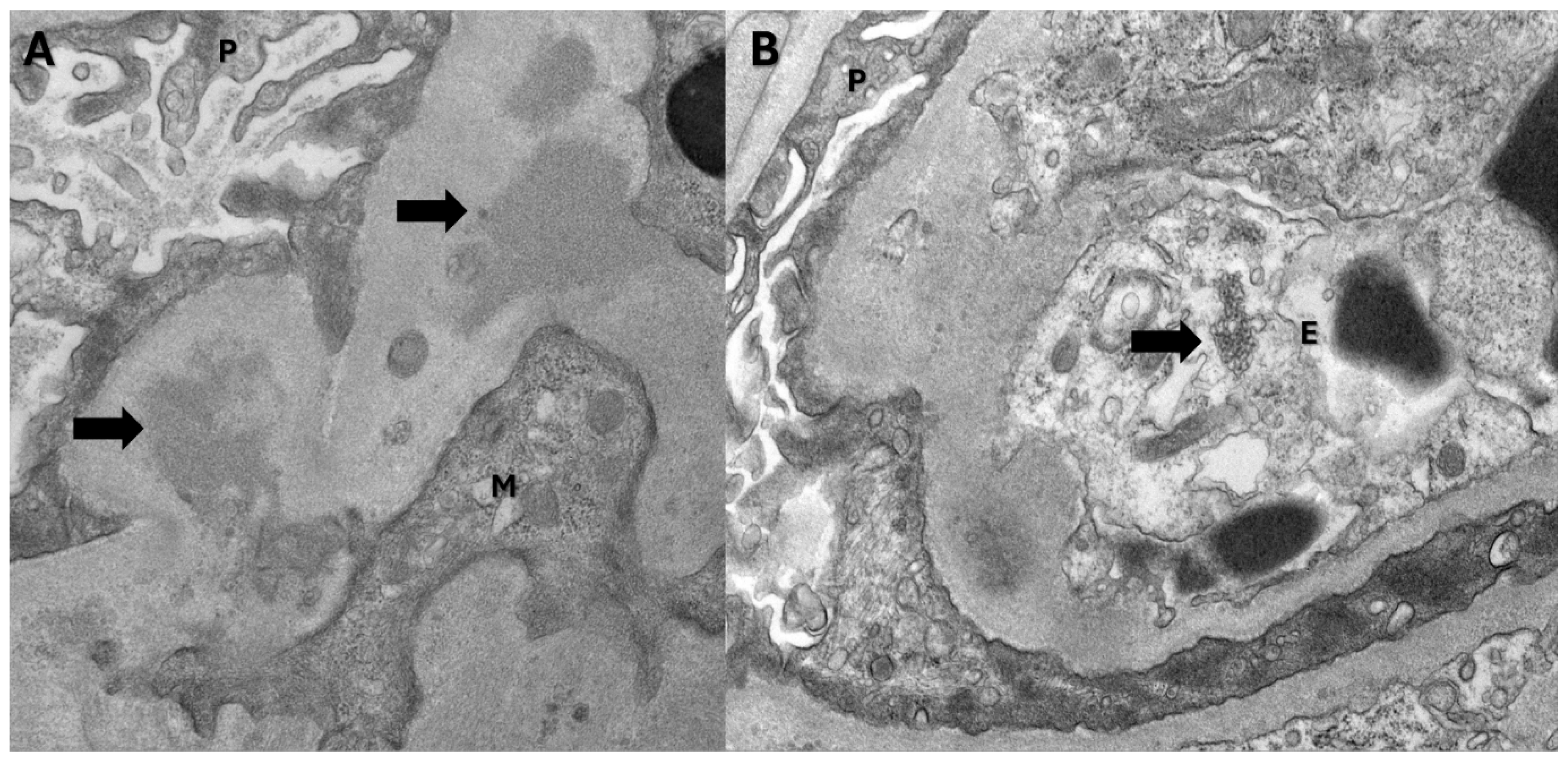

In our case, the patient had no previous history of chronic kidney disease or IgA nephropathy. His hematuria was attributed to infection-mediated crescentic glomerulonephritis secondary to COVID-19 infection. The biopsy revealed fibrinoid necrosis, crescentic glomerulonephritis, several RBC casts (in distal tubules), tubuloreticular inclusions in endothelial cells and C3 deposits supporting the diagnosis of infection-related glomerulonephritis [

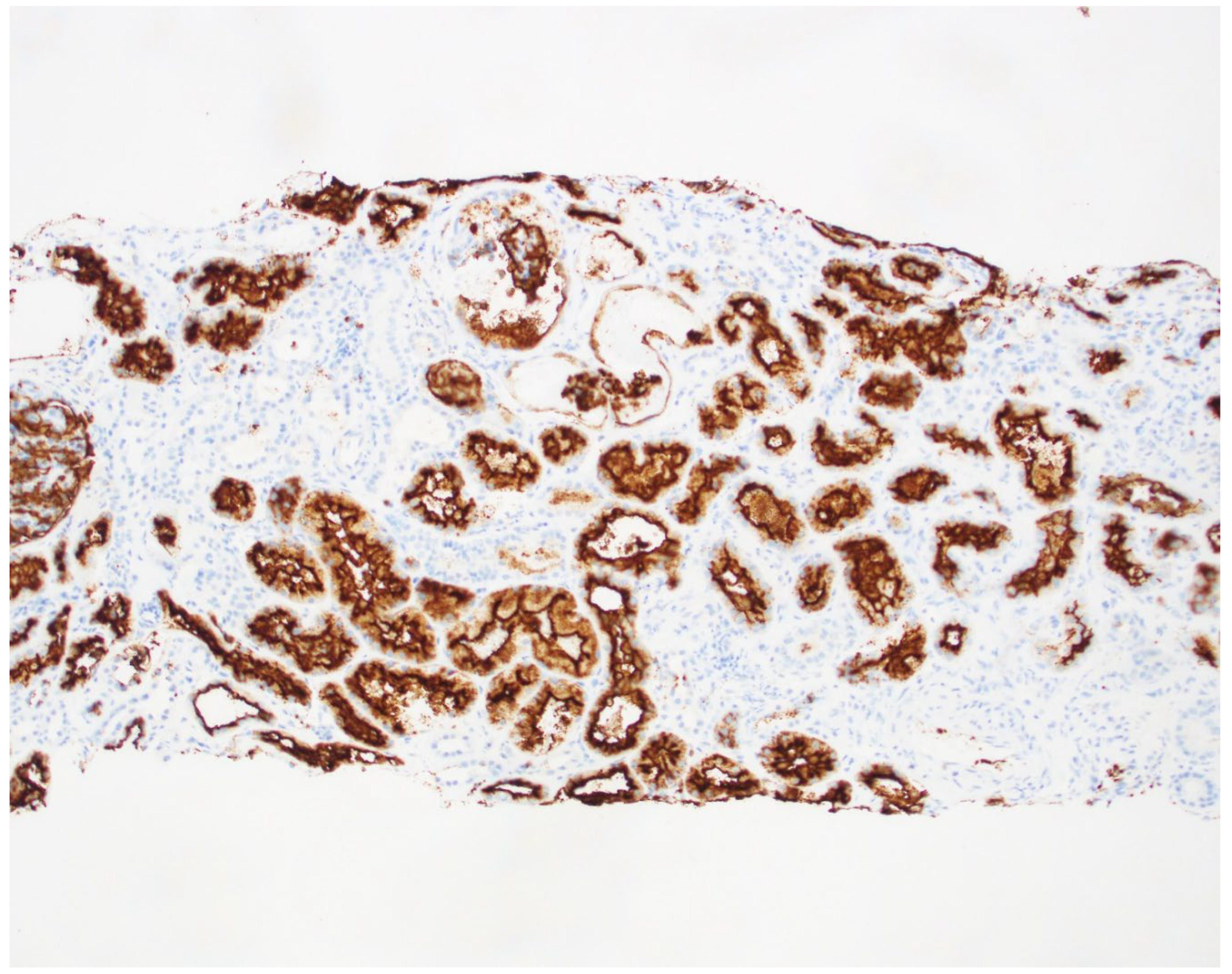

Figure 1and

Figure 2-biopsy images] from active COVID 19 infections. We did the CD10 staining to identify the proximal tubules. Despite the absence of respiratory symptoms, the patient was treated with Remdesivir (an antiviral agent inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), pulse steroids, and a prolonged prednisone taper over three months. The treatment led to the resolution of hematuria and improved renal function. This case is unique as it represents infection-related crescentic glomerulonephritis secondary to COVID-19 presenting initially with gross hematuria, a manifestation not previously described in the literature.

Figure 1.

Light microscopy findings: A. Glomerulus with segmental fibrinoid necrosis (arrow). B. Glomerulus with segmental cellular crescent (arrow). C. Red blood cell casts (arrows) in distal tubules. D. Immunofluorescence histology for C3 shows granular mesangial and capillary loop staining.

Figure 1.

Light microscopy findings: A. Glomerulus with segmental fibrinoid necrosis (arrow). B. Glomerulus with segmental cellular crescent (arrow). C. Red blood cell casts (arrows) in distal tubules. D. Immunofluorescence histology for C3 shows granular mesangial and capillary loop staining.

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy findings: A. Electron dense deposits(arrows) in the mesangial region (P: Visceral epithelial cell; M: Mesangial cell). B. Tubuloreticular inclusion body(arrow) (P: Visceral epithelial cell; E: Endothelial cell).

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy findings: A. Electron dense deposits(arrows) in the mesangial region (P: Visceral epithelial cell; M: Mesangial cell). B. Tubuloreticular inclusion body(arrow) (P: Visceral epithelial cell; E: Endothelial cell).

Figure 3.

Biopsy slide with CD 10 staining of the Proximal tubule.

Figure 3.

Biopsy slide with CD 10 staining of the Proximal tubule.