Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics

2.2. Sample Information

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

2.5. Methylation Calling

2.6. Differentially Methylated Genes and Regions Identification

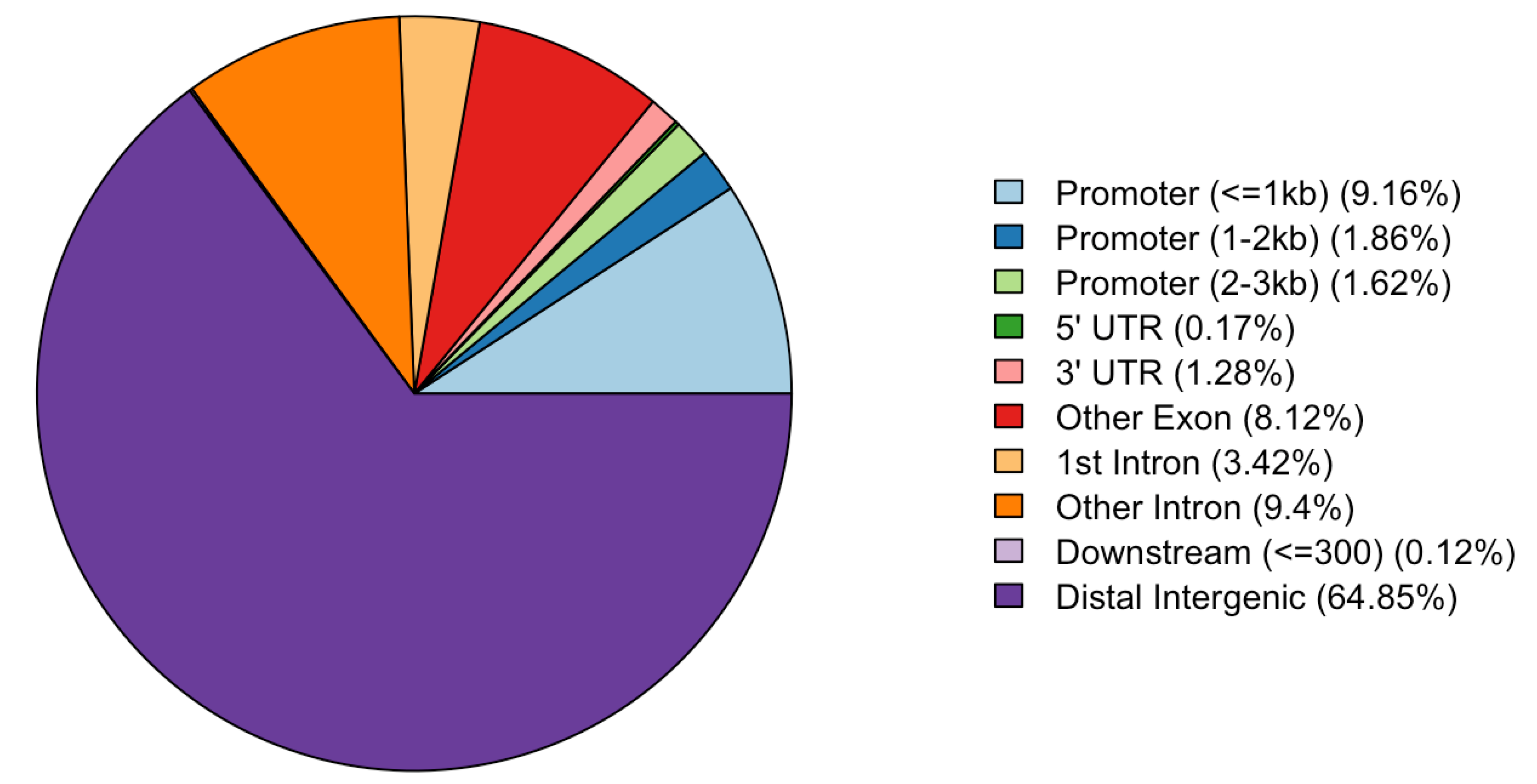

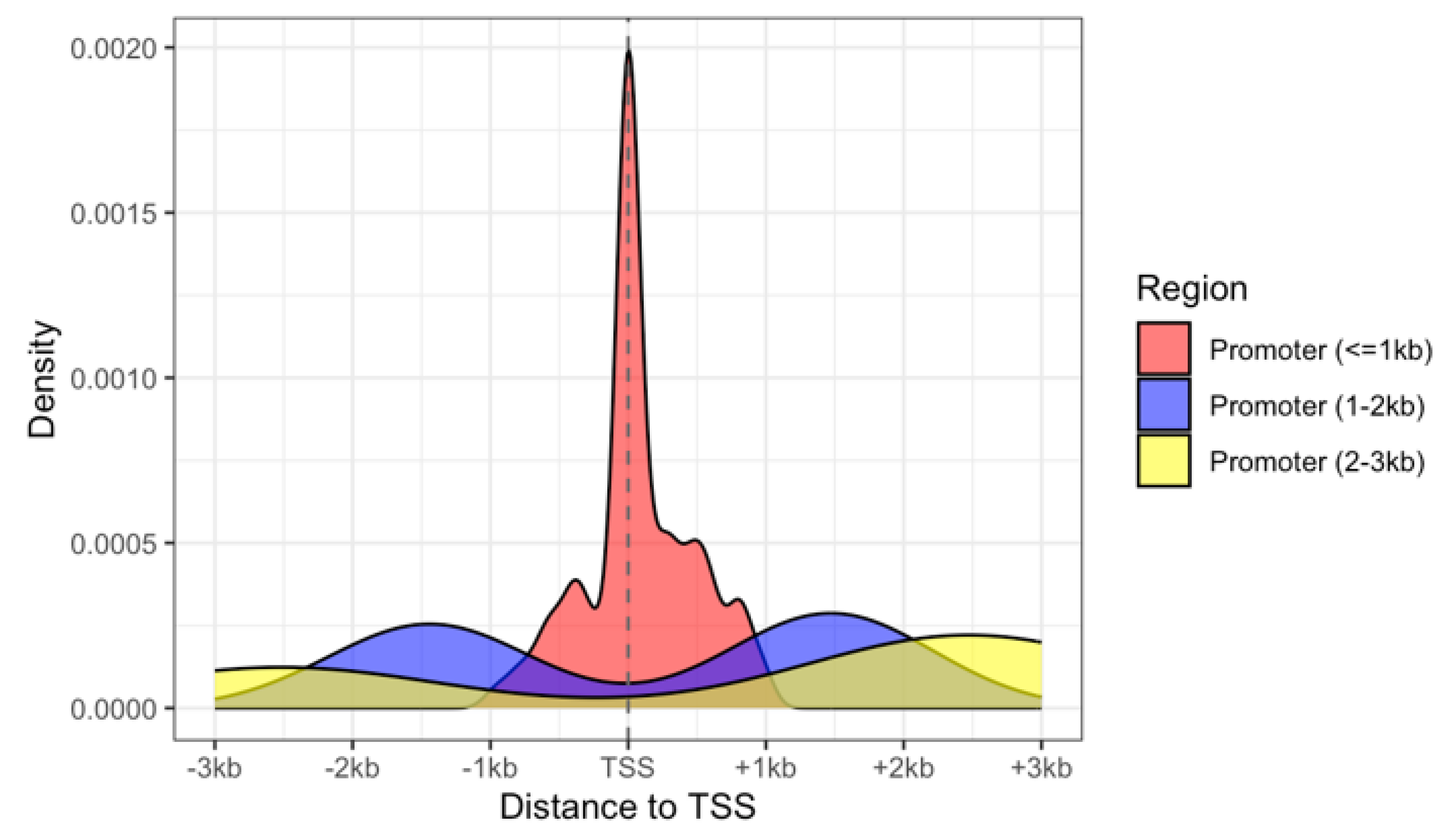

2.7. DMRs Annotation and DMRs Features Visualisation

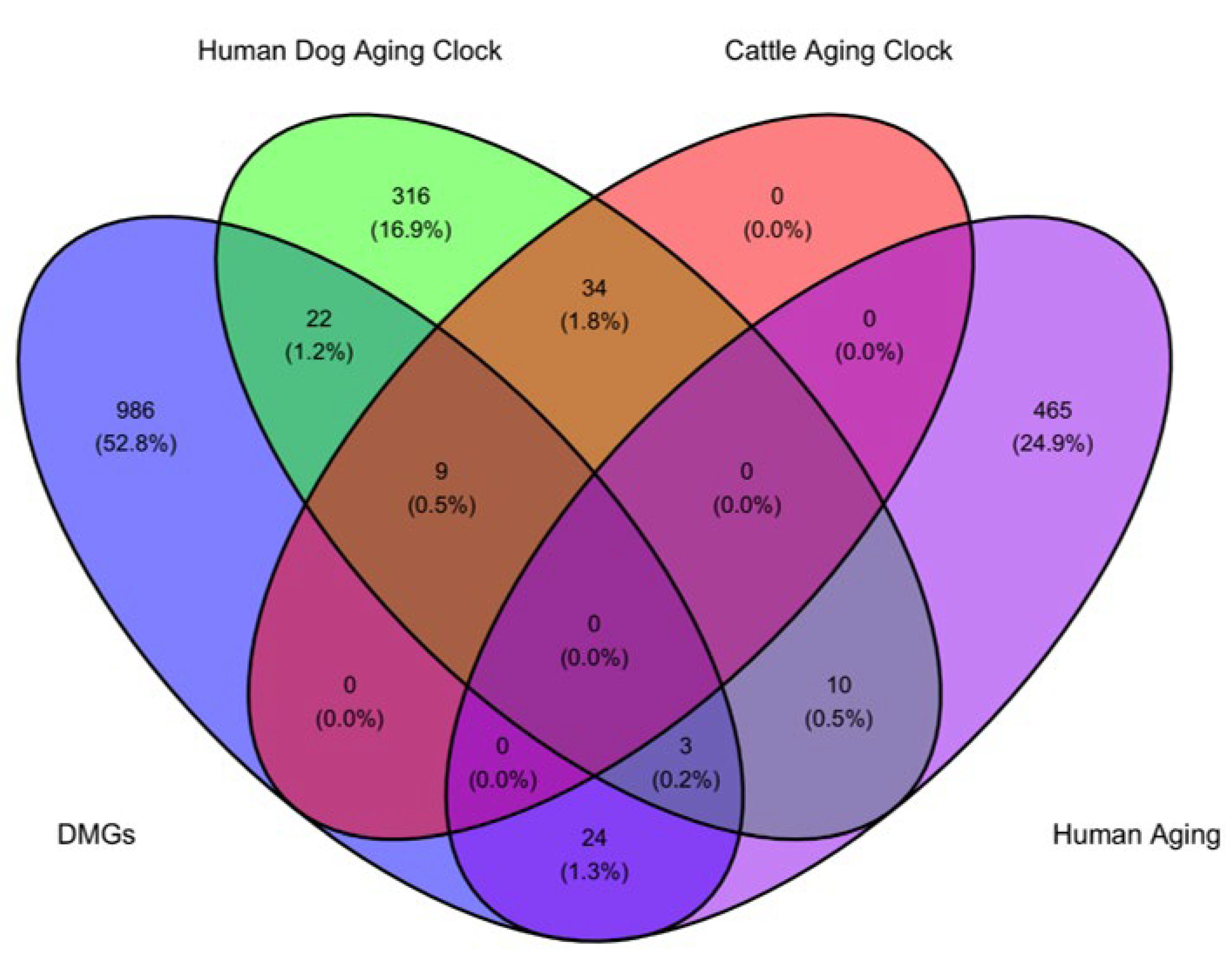

2.8. Identifying of Age-Related Genes

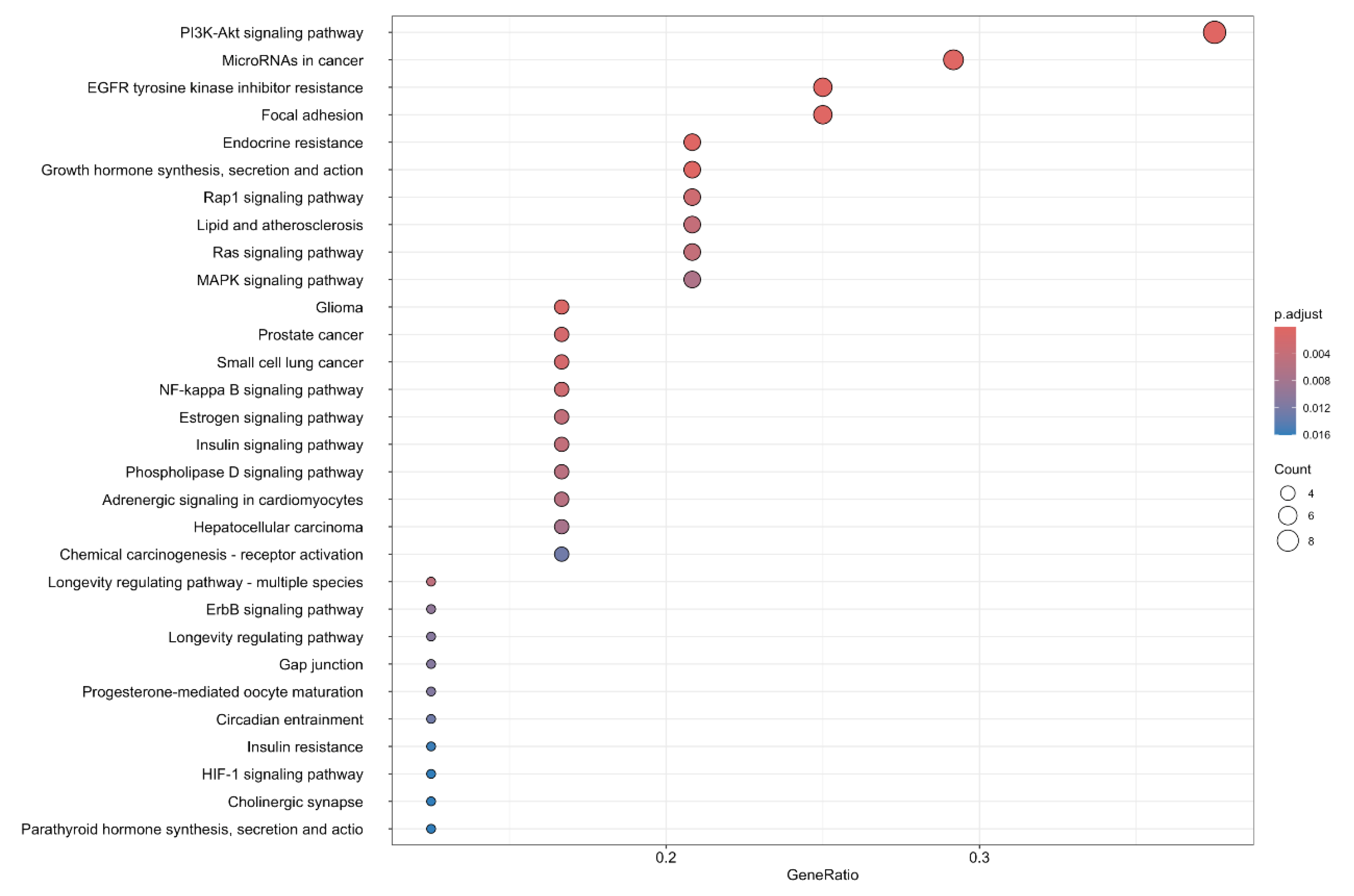

2.9. Identifying the Age-Related Gene Ontology Terms and KEGG Pathways

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Data Statistic

3.2. Differentially Methylated Genes and Regions Identification

3.3. Annotation of CpG Sites

3.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agricultural Trade Report [https://www.ruralbank.com.au/knowledge-and-insights/publications/agricultural-trade/].

- Holliday R, Pugh JE: DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science (New York, NY) 1975, 187(4173):226-232.

- Horvath S: DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biology 2013, 14(10):3156.

- Raj K, Szladovits B, Haghani A, Zoller JA, Li CZ, Black P, Maddox D, Robeck TR, Horvath S: Epigenetic clock and methylation studies in cats. GeroScience 2021, 43(5):2363-2378.

- Thompson MJ, Chwiałkowska K, Rubbi L, Lusis AJ, Davis RC, Srivastava A, Korstanje R, Churchill GA, Horvath S, Pellegrini M: A multi-tissue full lifespan epigenetic clock for mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10(10):2832-2854.

- Thompson MJ, vonHoldt B, Horvath S, Pellegrini M: An epigenetic aging clock for dogs and wolves. Aging 2017, 9(3):1055-1068.

- Wagner W: Epigenetic aging clocks in mice and men. Genome Biology 2017, 18(1):107.

- Raddatz G, Arsenault RJ, Aylward B, Whelan R, Böhl F, Lyko F: A chicken DNA methylation clock for the prediction of broiler health. Communications biology 2021, 4(1):76.

- Kordowitzki P, Haghani A, Zoller JA, Li CZ, Raj K, Spangler ML, Horvath S: Epigenetic clock and methylation study of oocytes from a bovine model of reproductive aging. Aging cell 2021, 20(5):e13349.

- Hayes BJ, Nguyen LT, Forutan M, Engle BN, Lamb HJ, Copley JP, Randhawa IAS, Ross EM: An Epigenetic Aging Clock for Cattle Using Portable Sequencing Technology. Frontiers in genetics 2021, 12:760450.

- Lamb HJ, Ross EM, Nguyen LT, Lyons RE, Moore SS, Hayes BJ: Characterization of the poll allele in Brahman cattle using long-read Oxford Nanopore sequencing. J Anim Sci 2020, 98(5).

- Rosen BD, Bickhart DM, Schnabel RD, Koren S, Elsik CG, Tseng E, Rowan TN, Low WY, Zimin A, Couldrey C et al.: De novo assembly of the cattle reference genome with single-molecule sequencing. GigaScience 2020, 9(3):giaa021.

- Li HJB: Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. 2018, 34(18):3094-3100.

- Gamaarachchi H, Lam CW, Jayatilaka G, Samarakoon H, Simpson JT, Smith MA, Parameswaran S: GPU accelerated adaptive banded event alignment for rapid comparative nanopore signal analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2020, 21(1):343.

- Feng H, Conneely KN, Wu H: A Bayesian hierarchical model to detect differentially methylated loci from single nucleotide resolution sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42(8):e69-e69.

- Wang Q, Li M, Wu T, Zhan L, Li L, Chen M, Xie W, Xie Z, Hu E, Xu S et al.: Exploring Epigenomic Datasets by ChIPseeker. Current Protocols 2022, 2(10):e585.

- Wang T, Ma J, Hogan AN, Fong S, Licon K, Tsui B, Kreisberg JF, Adams PD, Carvunis AR, Bannasch DL et al.: Quantitative Translation of Dog-to-Human Aging by Conserved Remodeling of the DNA Methylome. Cell Syst 2020, 11(2):176-185.e176.

- Xu S, Hu E, Cai Y, Xie Z, Luo X, Zhan L, Tang W, Wang Q, Liu B, Wang R et al.: Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nature protocols 2024, 19(11):3292-3320.

- Yu G: enrichplot: Visualization of Functional Enrichment Result. In.: R package; 2025.

- Luo W, Brouwer C: Pathview: an R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013, 29(14):1830-1831.

- López-Catalina A, Costes V, Peiró-Pastor R, Kiefer H, González-Recio O: Oxford nanopore sequencing as an alternative to reduced representation bisulphite sequencing for the identification of CpGs of interest in livestock populations. Livestock Science 2024, 279:105377.

- Fortes MR, Li Y, Collis E, Zhang Y, Hawken RJ: The IGF1 pathway genes and their association with age of puberty in cattle. Anim Genet 2013, 44(1):91-95.

- Fortes MRS, Nguyen LT, Porto Neto LR, Reverter A, Moore SS, Lehnert SA, Thomas MG: Polymorphisms and genes associated with puberty in heifers. Theriogenology 2016, 86(1):333-339.

- Jiang B, Wu X, Meng F, Si L, Cao S, Dong Y, Sun H, Lv M, Xu H, Bai N et al.: Progerin modulates the IGF-1R/Akt signaling involved in aging. Sci Adv 2022, 8(27):eabo0322.

- Tazearslan C, Huang J, Barzilai N, Suh Y: Impaired IGF1R signaling in cells expressing longevity-associated human IGF1R alleles. Aging cell 2011, 10(3):551-554.

- Mao K, Quipildor GF, Tabrizian T, Novaj A, Guan F, Walters RO, Delahaye F, Hubbard GB, Ikeno Y, Ejima K et al.: Late-life targeting of the IGF-1 receptor improves healthspan and lifespan in female mice. Nature Communications 2018, 9(1):2394.

- Savage SA, Chanock SJ, Lissowska J, Brinton LA, Richesson D, Peplonska B, Bardin-Mikolajczak A, Zatonski W, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Garcia-Closas M: Genetic variation in five genes important in telomere biology and risk for breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2007, 97(6):832-836.

- Shammas MA: Telomeres, lifestyle, cancer, and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2011, 14(1):28-34.

- Koss KJ, Schneper LM, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S, Mitchell C, Notterman DA: Early Puberty and Telomere Length in Preadolescent Girls and Mothers. J Pediatr 2020, 222:193-199.e195.

- Nguyen LT, Zacchi LF, Schulz BL, Moore SS, Fortes MRS: Adipose tissue proteomic analyses to study puberty in Brahman heifers. J Anim Sci 2018, 96(6):2392-2398.

- Nardai G, Csermely P, Söti C: Chaperone function and chaperone overload in the aged. A preliminary analysis. Exp Gerontol 2002, 37(10-11):1257-1262.

- Plant TM: Neuroendocrine control of the onset of puberty. Front Neuroendocrinol 2015, 38:73-88.

- Nguyen LT, Lau LY, Fortes MRS: Proteomic Analysis of Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland in Pre and Postpubertal Brahman Heifers. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13:935433.

- Luo L, Yao Z, Ye J, Tian Y, Yang C, Gao X, Song M, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li Y et al.: Identification of differential genomic DNA Methylation in the hypothalamus of pubertal rat using reduced representation Bisulfite sequencing. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2017, 15(1):81.

- Nguyen LT, Reverter A, Cánovas A, Venus B, Anderson ST, Islas-Trejo A, Dias MM, Crawford NF, Lehnert SA, Medrano JF et al.: STAT6, PBX2, and PBRM1 Emerge as Predicted Regulators of 452 Differentially Expressed Genes Associated With Puberty in Brahman Heifers. Frontiers in genetics 2018, 9:87.

- Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M: mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature 2013, 493(7432):338-345.

- Roa J, Garcia-Galiano D, Varela L, Sánchez-Garrido MA, Pineda R, Castellano JM, Ruiz-Pino F, Romero M, Aguilar E, López M et al.: The mammalian target of rapamycin as novel central regulator of puberty onset via modulation of hypothalamic Kiss1 system. Endocrinology 2009, 150(11):5016-5026.

- Palumbo S, Palumbo D, Cirillo G, Giurato G, Aiello F, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Grandone A: Methylome analysis in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty. Clin Epigenetics 2024, 16(1):82.

- Sehovic E, Zellers SM, Youssef MK, Heikkinen A, Kaprio J, Ollikainen M: DNA methylation sites in early adulthood characterised by pubertal timing and development: a twin study. Clin Epigenetics 2023, 15(1):181.

- Han L, Zhang H, Kaushal A, Rezwan FI, Kadalayil L, Karmaus W, Henderson AJ, Relton CL, Ring S, Arshad SH et al.: Changes in DNA methylation from pre- to post-adolescence are associated with pubertal exposures. Clinical Epigenetics 2019, 11(1):176.

- Perrier JP, Kenny DA, Chaulot-Talmon A, Byrne CJ, Sellem E, Jouneau L, Aubert-Frambourg A, Schibler L, Jammes H, Lonergan P et al.: Accelerating Onset of Puberty Through Modification of Early Life Nutrition Induces Modest but Persistent Changes in Bull Sperm DNA Methylation Profiles Post-puberty. Frontiers in genetics 2020, 11:945.

- Meaker HJ, Coetsee TPN, Lishman AW: The effects of age at first calving on the productive and reproductive performance of beef cows. South African Journal of Animal Science 1980, 10(2):105-113.

| Sample | Age | Weight | Hip Height | Body Condition Score | N50 | Total Methylation site (M) | Filtered Methylation site (10X - M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult_01 | 2.64 | 586 | 1430 | 4 | 1.25 | 15.5 | 0.77 |

| Adult_02 | 2.65 | 610 | 1410 | 4 | 2.45 | 14.7 | 0.79 |

| Adult_03 | 2.62 | 530 | 1340 | 5 | 2.33 | 17.8 | 1.17 |

| Mean | 2.64 | 575.33 | 1393.33 | 4.33 | 2.01 | 16.00 | 0.91 |

| SD | 0.02 | 41.05 | 47.26 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 1.61 | 0.23 |

| Yearling_01 | 1.5 | 281 | 1290 | 3 | 1.63 | 18.9 | 1.39 |

| Yearling_02 | 1.52 | 424 | 1290 | 4.5 | 1.27 | 20.7 | 1.63 |

| Yearling_03 | 1.42 | 414 | 1240 | 4.5 | 2.72 | 20.2 | 1.49 |

| Mean | 1.48 | 373.00 | 1273.33 | 4.00 | 1.87 | 19.93 | 1.50 |

| SD | 0.05 | 79.83 | 28.87 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).