Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

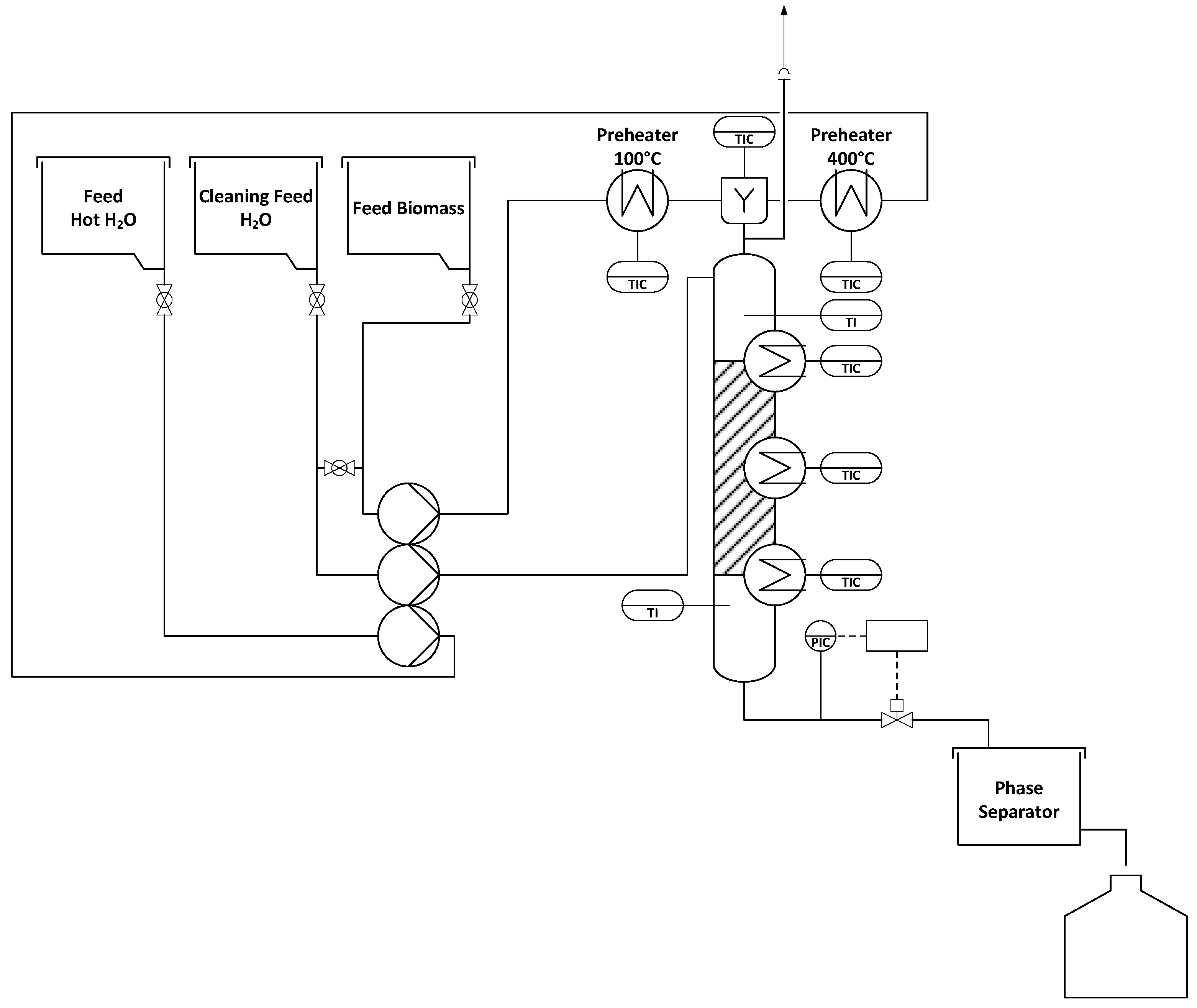

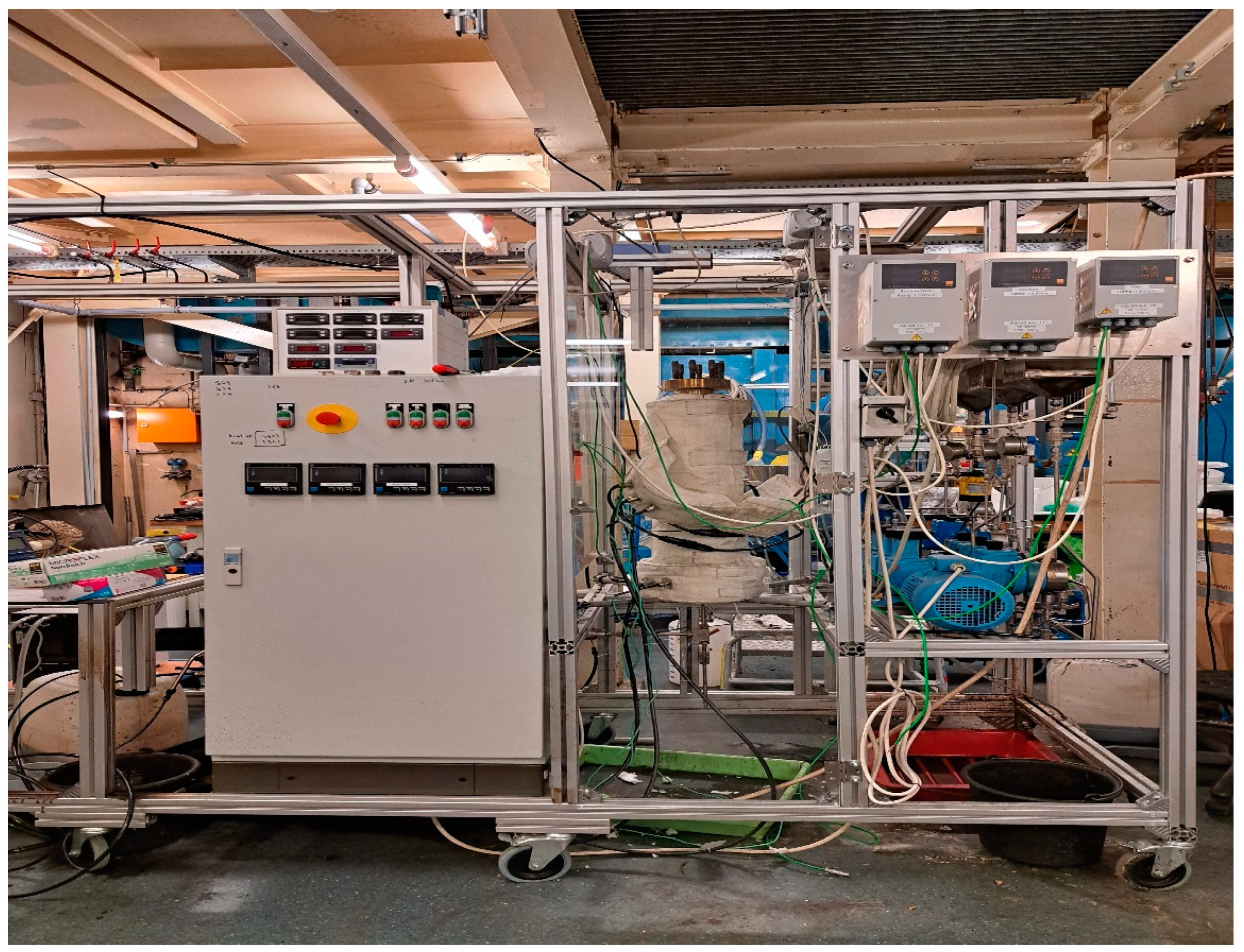

2.2. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Lignin

2.3. Adsorbent and DES Preparation

2.4. Adsorption Experiments on Model Compounds

2.5. Adsorbent Modification

2.6. Adsorption Experiments on HTL of Lignin Using DES Modified XAD-4

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Component Analysis of the Organic/Aqueous Phase of the HTL of Lignin Product

3.2. Characterization of XAD-4 and Modified Adsorbent

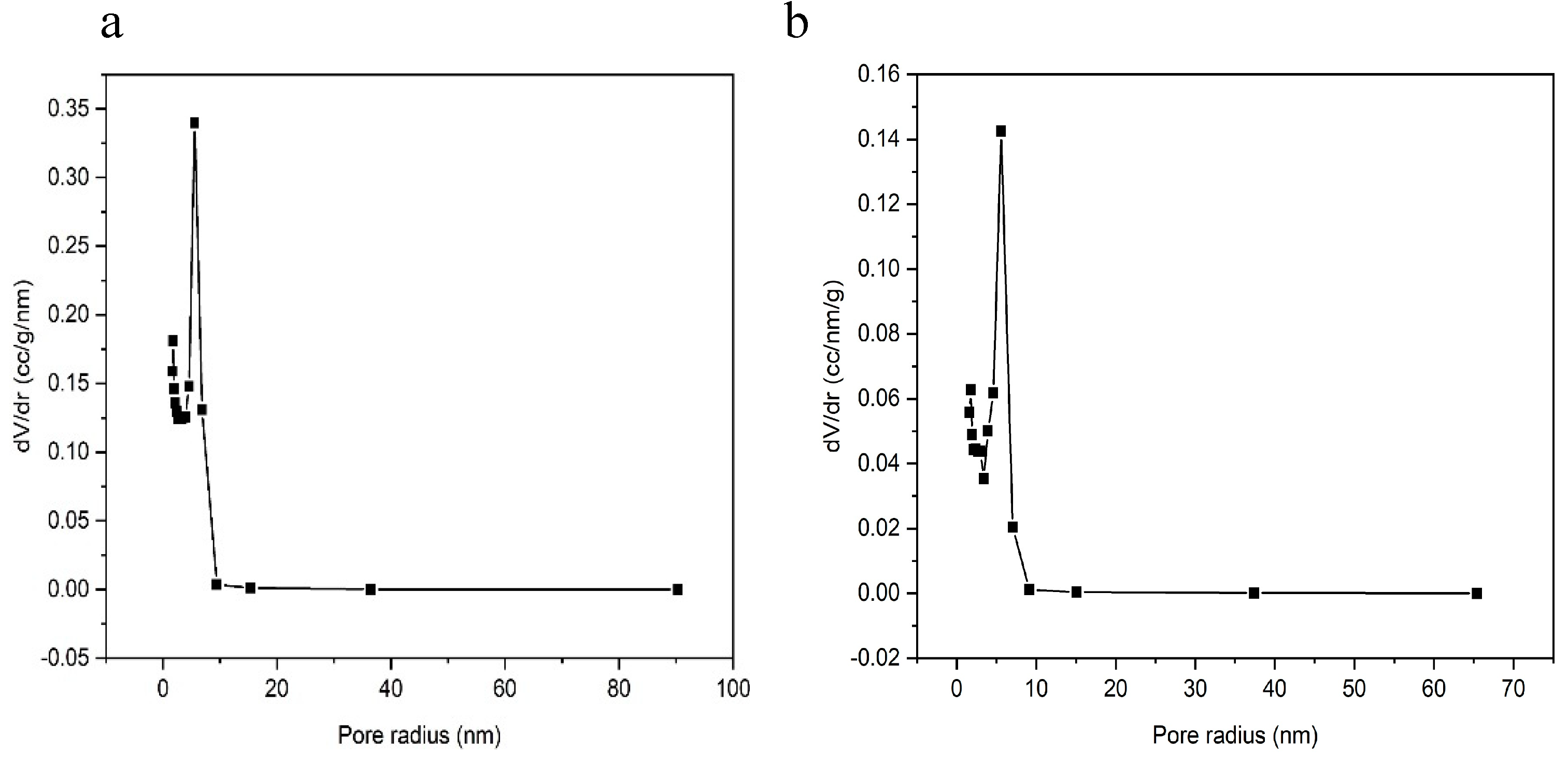

3.2.1. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Parameters

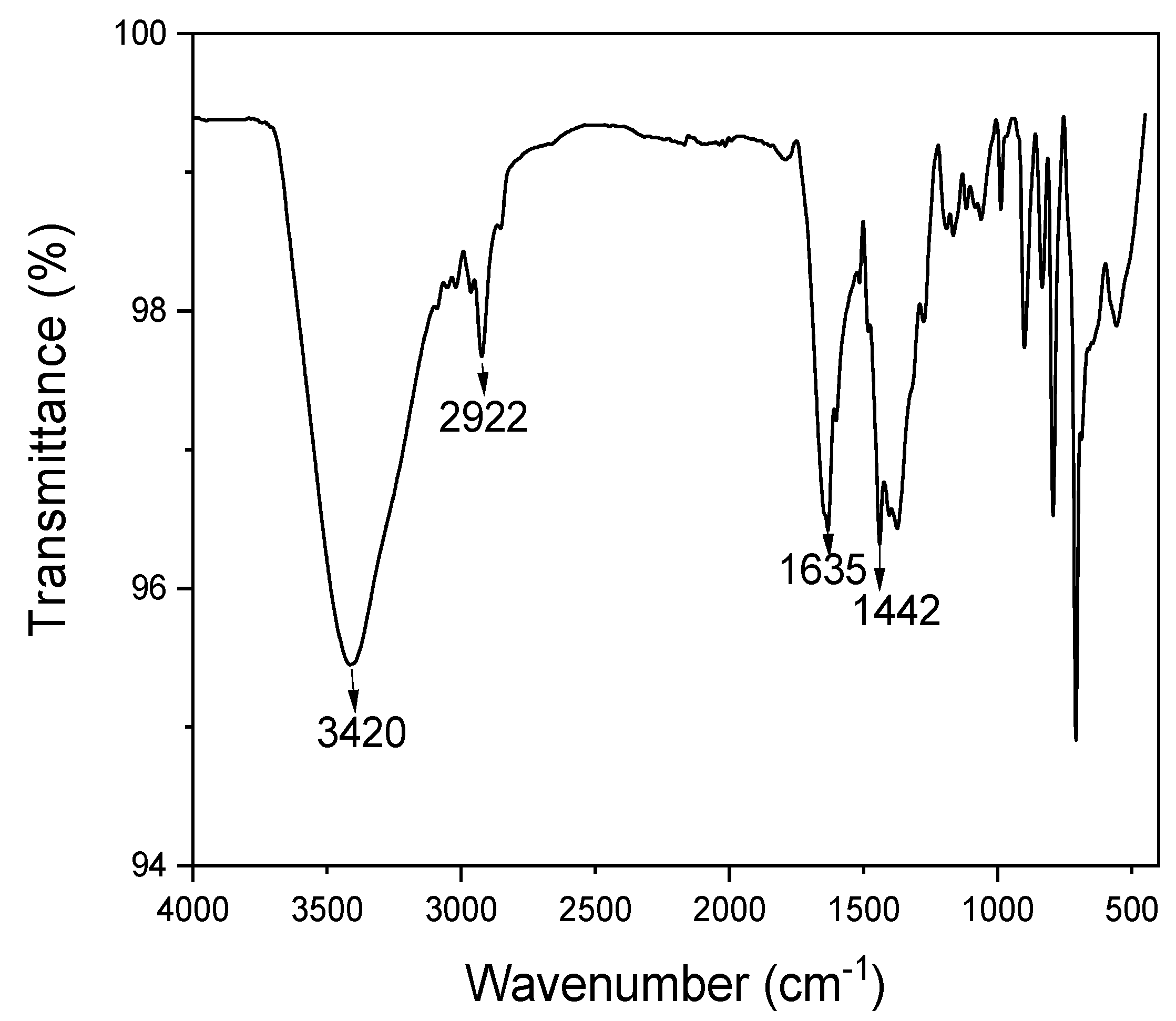

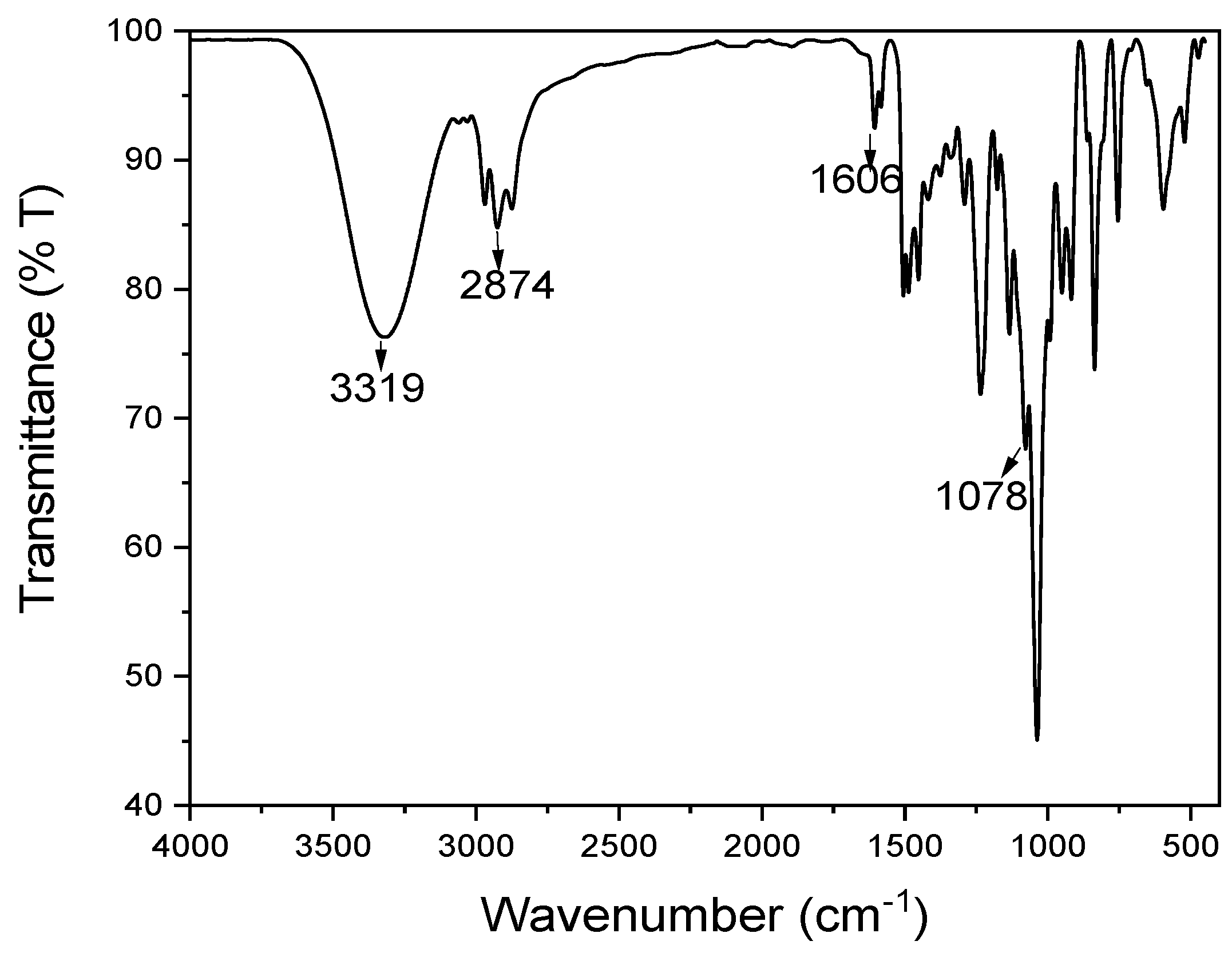

3.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

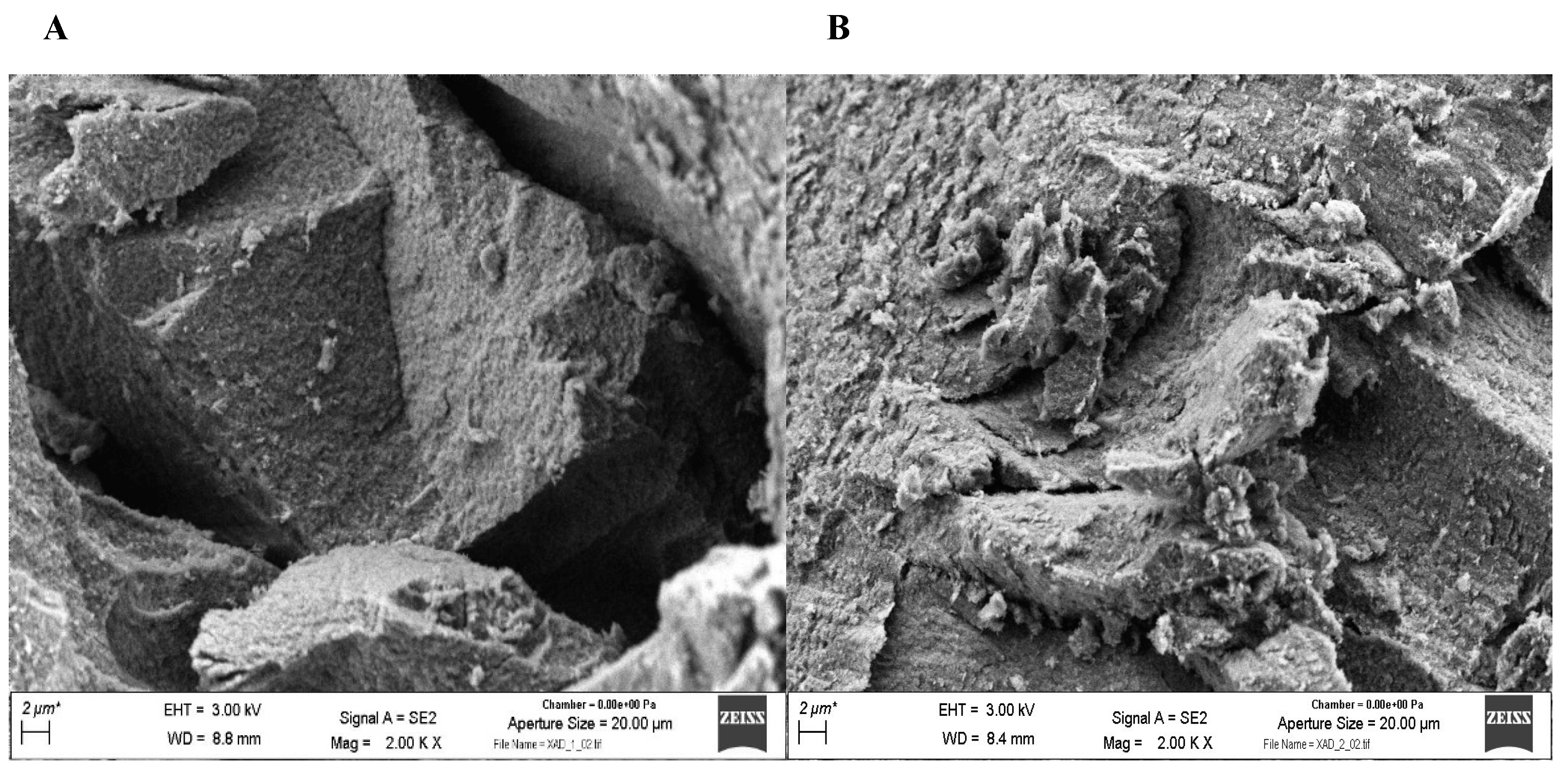

3.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

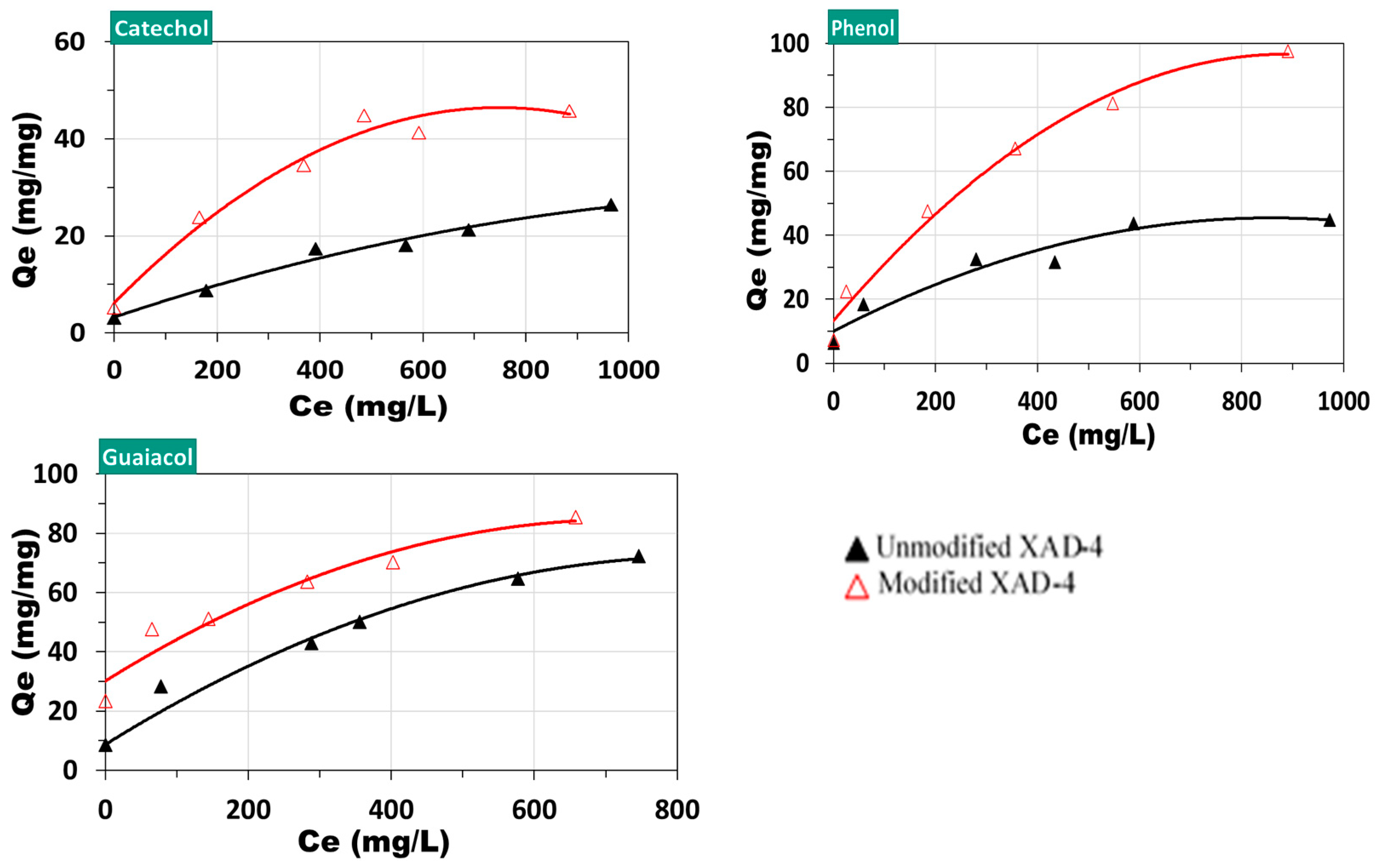

3.3. Performance of Unmodified and Modified XAD-4 on Model Compounds

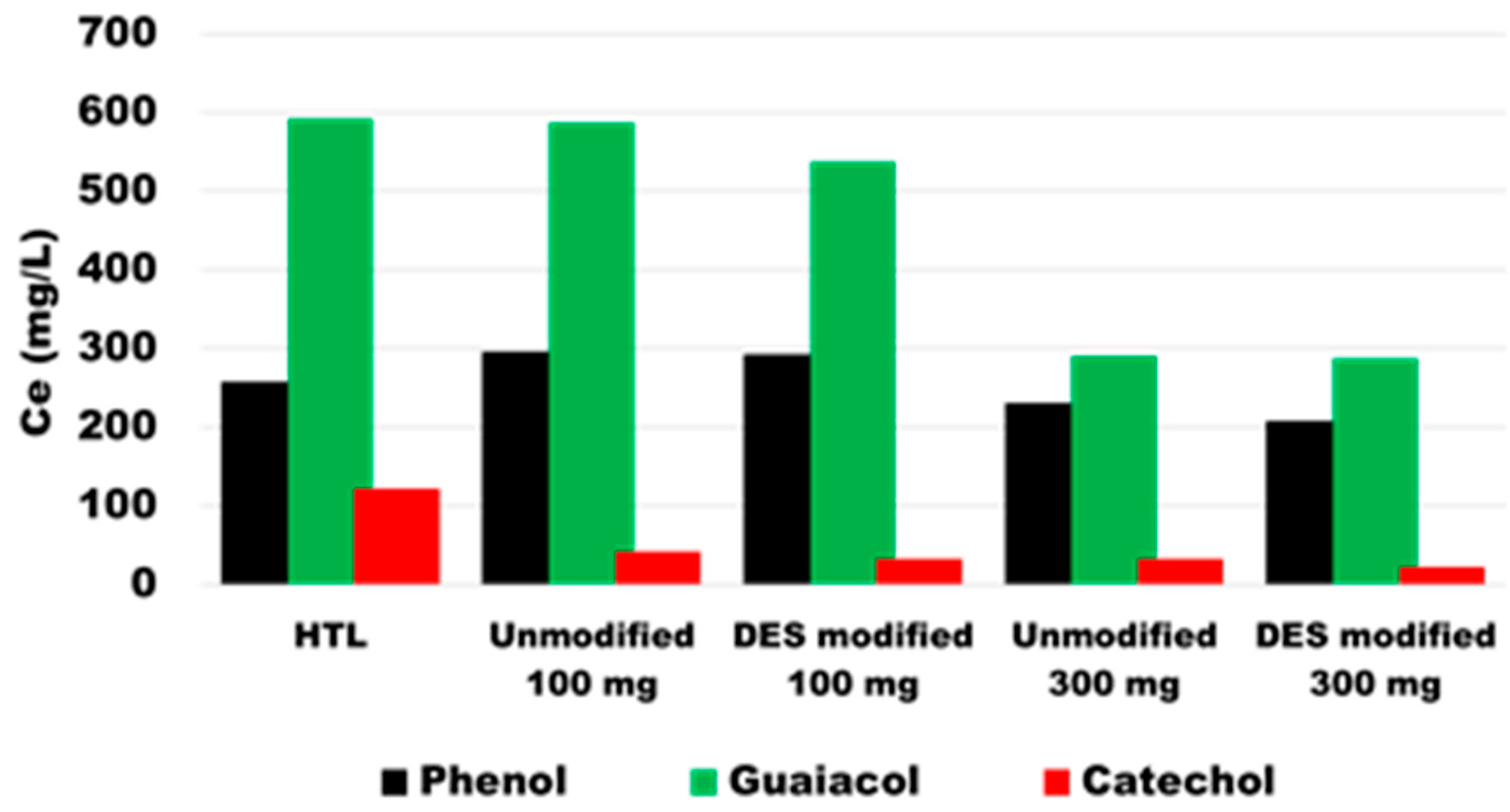

3.4. Performance of Unmodified and Modified XAD-4 on HTL Product

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roy, R.; Rahman, M. S.; Raynie, D. E. Recent Advances of Greener Pretreatment Technologies of Lignocellulose. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2020, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Purkait, M. K. Lignocellulosic Conversion into Value-Added Products: A Review. Process Biochemistry 2020, 89, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, N.; Lewandowski, I.; Zibek, S.; Weidtmann, A. Integrated Lignocellulosic Value Chains in a Growing Bioeconomy: Status Quo and Perspectives. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, D.; Leitch, M.; Fatehi, P. Lignin–Carbohydrate Complexes: Properties, Applications, Analyses, and Methods of Extraction: A Review. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Chang, C.; Zhang, L.; Cui, S.; Luo, X.; Hu, S.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y. Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass Into Platform Chemicals for Biobased Polyurethane Application. In Advances in Bioenergy; Elsevier, 2018; 3, pp 161–213. [CrossRef]

- Muddasar, M.; Culebras, M.; Collins, M.N. Lignin and its carbon derivatives: Synthesis techniques and their energy storage applications. Mater. Today Sustain 2024, 28, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, D.S.; Pourhashem, B.; Ullahb, A.H. ; Bajwa. S.G. A concise review of current lignin production, applications, products and their environmental impact. Ind. Crops & Prod 2019, 139, 111526. 139. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K.G.; Hobson, P.A. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Lignin. In Cane-based Biofuels and Bioproducts, 1st ed; O’Hara, I.; Mundree, S.; Eds; John Wiley & Sons. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, Y.; Hornung, U.; Bugaje, I.M. Lignin Hydrothermal Liquefaction into Bifunctional Chemicals: A Concise Review, 1st ed.; Besschkov, V., Ed; InTechOpen. London, UK, 2020; ch 5. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Thilakarathna, W.; He, Q.S.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. A Review: Depolymerization of Lignin to Generate High-Value Bio-Products: Opportunities, Challenges, and Prospects. Front. Energy Res 2022, 9, 758744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, J.; Hornung, U.; Kruse, A.; Dahmen, N.; Sauer, J. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Lignin. Journal of Biomaterials and Nanobiotechnology 2016, 8, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. , Huang, K., & Yan, C. (2009). Application of an easily water-compatible hypercrosslinked polymeric adsorbent for efficient removal of catechol and resorcinol in aqueous solution. Journal of Hazardous Materials. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Lyu, H.; Hao, S.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Separation of Phenolic Compounds with Modified Adsorption Resin from Aqueous Phase Products of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Rice Straw. Bioresource Technology 2015, 182, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issabayeva, G.; Hang, S. Y.; Wong, M. C.; Aroua, M. K. A Review on the Adsorption of Phenols from Wastewater onto Diverse Groups of Adsorbents. Reviews in Chemical Engineering 2018, 34, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, C.-M.; Ardelean, R.; Popa, A. New Polymeric Adsorbent Materials Used for Removal of Phenolic Derivatives from Wastewaters. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2019, 91, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E. F.; Andriantsiferana, C.; Wilhelm, A. M.; Delmas, H. Competitive Adsorption of Phenolic Compounds from Aqueous Solution Using Sludge-based Activated Carbon. Environmental Technology 2011, 32, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S. Sorptive separation of phenolic compounds from wastewater. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M. A. R.; Pinho, S. P.; Coutinho, J. A. P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J Solution Chem 2019, 48, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B. B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J. M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B. W.; Gurkan, B.; Maginn, E. J.; Ragauskas, A.; Dadmun, M.; Zawodzinski, T. A.; Baker, G. A.; Tuckerman, M. E.; Savinell, R. F.; Sangoro, J. R. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, I. A.; Klink, M.; Ndungu, P. Deep Eutectic Solvent as an Efficient Modifier of Low-Cost Ad sorbent for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Dye. Environmental Research 2019, 179, 108837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Row, K. H. Hydrophilic Deep Eutectic Solvents Modified Phenolic Resin as Tailored Adsorbent for the Extraction and Determination of Levofloxacin and Ciprofloxacin from Milk. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021, 413, 4329–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A. P.; Boothby, D.; Capper, G.; Davies, D. L.; Rasheed, R. K. Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed between Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids: Versatile Alternatives to Ionic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9142–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoś, P.; Słupek, E.; Małachowska, A. Silica Gel Impregnated by Deep Eutectic Solvents for Adsorptive Removal of BTEX from Gas Streams. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffi, B.; Loppi, M.; Rizzo, A. M.; Chiaramonti, D.; Rosi, L. Towards a Better Understanding of the HTL Process of Lignin-Rich Feedstock. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrovi, M. H.; Abolhassanzadeh Parizi, M. The Modification of the BET Surface Area by Considering the Excluded Area of Adsorbed Molecules. PCR 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid Kalal, H.; Panahi, H. A.; Hoveidi, H.; Taghiof, M.; Menderjani, M. T. Synthesis and Application of Amberlite Xad-4 Functionalized with Alizarin Red-s for Preconcentration and Adsorption of Rhodium (III). J Environ Health Sci Engineer 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrijević, J.; Jevtić, S.; Marinković, A.; Simić, M.; Koprivica, M.; Petrović, J. Ability of Deep Eutectic Solvent Modified Oat Straw for Cu(II), Zn(II), and Se(IV) Ions Removal. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Ye, P.; Borole, A. P. Separation of Chemical Groups from Bio-Oil Aqueous Phase via Sequential Organic Solvent Extraction. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 123, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansado, I. P. D. P.; Mourão, P. A. M.; Morais, I. D.; Peniche, V.; Janeirinho, J. Removal of 4-Ethylphenol and 4-Ethylguaiacol, from Wine-like Model Solutions, by Commercial Modified Activated Carbons Produced from Coconut Shell. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Srivastava, V. C.; Mishra, I. M. Adsorption of Catechol, Resorcinol, Hydroquinone, and Their Derivatives: A Review. Int J Energy Environ Eng 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S. A.; Yang, L.-M.; Saha, L. C.; Ahmed, E.; Ajmal, M.; Ganz, E. A Fundamental Understanding of Catechol and Water Adsorption on a Hydrophilic Silica Surface: Exploring the Underwater Adhesion Mechanism of Mussels on an Atomic Scale. Langmuir 2014, 30, 6906–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogstad, T. M.; Kiewidt, L.; Van Haasterecht, T.; Bitter, J. H. Size Selectivity in Adsorption of Polydisperse Starches on Activated Carbon. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 309, 120705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, R.; Peleanu, I.; Meghea, I.; Tudorache, A. Competitive Adsorption Models of Organic Pollutants from Bi-and Tri-Solute Systems on Activated Carbon. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 1998, 229, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, R.-S.; Lin, S.-H.; Tsao, K.-H. Mechanism of Sorption of Phenols from Aqueous Solutions onto Surfactant-Modified Montmorillonite. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2002, 254, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Nakato, T. Competitive Adsorption of Phenols on Organically Modified Layered Hexaniobate K4Nb6O17. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2006, 96, (1–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, M.; Cui, Y.; Alali, A.; Atkinson, J. D. Phenol Adsorption and Desorption with Physically and Chemically Tailored Porous Polymers: Mechanistic Variability Associated with Hyper-Cross-Linking and Amination. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2019, 361, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Adsorbate | Concentration (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenol | 592.7 |

| 2 | O-cresol | 13.6 |

| 3 | Guaiacol | 823.5 |

| 4 | Catechol | 257.4 |

| 5 | 4-Ethylphenol | - |

| 6 | 4-Methylguaiacol | 86.5 |

| 7 | 4-Ethylguaiacol | 80.5 |

| 8 | Syringol | 75.1 |

| 9 | Methanol | - |

| 10 | 3-Ethylphenol | - |

| 11 | 2-Methoxy-4-Propylphenol | - |

| 12 | 4-Ethylcatechol | - |

| 13 | 3-Methoxycatechol | - |

| 14 | 3-Methylcatechol | - |

| 15 | Resorcinol | - |

| 16 | Vanillin | - |

|

XAD-4 | DES modified XAD-4 |

|---|---|---|

| BET surface area (m2/g) | 864.52 | 629.76 |

| Micropore BET (m2/g) | 123.86 | 107.19 |

| Total pore volume (cm3/g) | 1.09 | 0.76 |

| Micropore volume (cm3/g) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Average pore radius (nm) | 5.56 | 5.59 |

| Adsorbate | Adsorbent | n | Kf | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | unmodified XAD-4 | 1.911 | 3.918 | 0.9987 |

| Phenol | modified XAD-4 | 3.042 | 4.739 | 0.9967 |

| Guaiacol | unmodified XAD-4 | 2.538 | 5.169 | 0.9985 |

| Guaiacol | modified XAD-4 | 3.918 | 12.522 | 0.9987 |

| Catechol | unmodified XAD-4 | 1.773 | 2.257 | 0.9979 |

| Catechol | modified XAD-4 | 2.636 | 3.853 | 0.9598 |

| Adsorbate | Adsorbent | Qmax | Kl | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.1068 | 0.1068 | 0.1068 |

| Phenol | modified XAD-4 | 0.1113 | -1240000 | -4.78E-08 |

| Guaiacol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.1135 | 2430000 | -2.17E-08 |

| Guaiacol | modified XAD-4 | 0.1108 | -1290000 | -3.58E-08 |

| Catechol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.0653 | -0.117 | -1.33 |

| Catechol | modified XAD-4 | 0.4243 | 0.00976 | 0.9024 |

| Adsorbate | Adsorbent | B | A | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.0687 | 0.041 | 0.9365 |

| Phenol | modified XAD-4 | 0.0585 | 0.0692 | 0.9036 |

| Guaiacol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.0643 | 0.0616 | 0.9115 |

| Guaiacol | modified XAD-4 | 0.0651 | 0.0533 | 0.9025 |

| Catechol | unmodified XAD-4 | 0.0606 | 0.219 | 0.9127 |

| Catechol | modified XAD-4 | 0.0575 | 0.349 | 0.8394 |

| Catechol (mg/L) | Phenol (mg/L) | Guaiacol (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTL product | 257.4 | 592.9 | 823.5 |

| Unmodified XAD-4 (100mg) | 296.1 | 587.3 | 41.9 |

| DES modified XAD-4 (100 mg) | 293.4 | 538.0 | 32.7 |

| Unmodified XAD-4 (300mg) | 231.2 | 295.3 | 33.8 |

| DES modified XAD-4 (300 mg) | 207.8 | 287.6 | 121.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).