1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains one of the leading cause for morbidity and mortality globally [

1]. Different strategies have been utilised to risk stratify patients and to aid decision making regarding optimal mode of revascularization for those who are symptomatic with angina [

2,

3,

4]. The Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) score is a well-established method to grade the complexity of CAD and high syntax score is associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at long-term follow up [

5].

The BCIS (British Cardiovascular Intervention Society) Jeopardy Score (BCIS-JS) was proposed as a scoring system taking into account myocardium at risk and is modified from the Duke Jeopardy Score [

4,

6]. The BCIS-JS is a simple system, provides semi-quantitative assessment of the myocardium at jeopardy, and can be used in patients with previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) [

7,

8]. It may provide insight into the procedural risk of patients undergoing PCI, particularly in patients with impaired left ventricle function [

7,

8].

Increasingly, BCIS-JS is being utilised as a method of defining complex CAD. Direct comparison between the two scoring systems is limited, particularly in patients who are deemed at high revascularization risk such as diabetes [

9]. Recent data suggest a role for the use of functional assessment, [

10,

11]. intra-vascular imaging, [

12] and intensive pharmacotherapy in diabetic patients undergoing PCI [

13,

14]. Better understanding of procedural and long-term risks, using BCIS-JS and/or SYNTAX scoring systems, will help providing insights into the role of PCI in patients with diabetes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the relationship between SYNTAX and BCIS-JS in patients who underwent complex PCI procedures and to identify if any of the two scoring systems can provide prognostic insight in patients with diabetes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a single-centre, retrospective observational study of consecutive patients who underwent complex PCI procedure and deemed not suitable for surgical revascularization (formal surgical turned down) [

15]. Clinical and procedural characteristics were prospectively entered into institutional electronic database and validated by a dedicated data manager. Anonymized data were obtained and retrospectively analysed and therefore the need for informed consent was waived by the institutional Medical Ethical Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines

The included patients were discussed and turned down for surgical revascularization by the Heart team. Patients were only included in this analysis if they underwent PCI and those who were treated medically or had plain balloon angioplasty were excluded.

2.2. PCI Procedure

The PCI procedure was performed according to current guidelines on coronary revascularization [

16,

17]. The PCI strategy was left to the operator’s discretion but majority of cases were done using trans-radial approach, minimal sedation and local anaesthesia. Heparin was universally used in all cases and patients were pre-loaded with aspirin and second antiplatelet agent before PCI.

The cohort included both stable and unstable patients. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) included unstable angina, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Unstable angina was defined as myocardial ischemia at rest or on minimal exertion in the absence of acute cardiomyocyte injury, identified using cardiac biomarker, and resulting in urgent hospital admission. Myocardial infarction was defined according to the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction [

18].

2.3. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was all-cause mortality at 12 months follow up. This was obtained from the institutional local database and cross-checked using data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS). Procedural complication was defined as the composite endpoint of side branch occlusion, slow flow or no-reflow, any arterial dissection, pericardial tamponade, cardiogenic shock, or major bleeding.

Both SYNTAX and BCIS-JS were calculated by experienced operators who were blinded to each other scores. Scoring calculation was done off-line and was blindly performed to patients’ clinical outcomes. In-hospital outcomes and complications were gathered from the databases. High SYNATX score was defined as more than 33 in line with previously reported studies [

3,

19,

20]. The Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study defined high BCIS-JS of more than 6 and the current analysis utilised the same cut-off [

8].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk test and reported as mean (+/- standard deviation) for normal distribution variables and compared using unpaired t tests. Non-normally distributed data were reported using median (Q1-Q3) and compared using Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Dichotomous data were reported as absolute number and percentages; and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Correlation analysis was done using Spearman test given the semi-quantitative nature of BCIS-JS data. The Kaplan–Meier survival methods with log-rank tests were used to assess the role of high versus low syntax and BCIS-JS on one-year mortality. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 28.0 and P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

A total of 452 patients were included in the study. The mean age was 72 ±11 years with 29% female. The indication for PCI was 46% for stable angina presentation. Preserved left ventricle function was present in 52% of patients. The mean Euro Score II was 6 (±6) and large percentage of patients had left main intervention (42%). High syntax score was calculated in 57% of patients compared to 93% of patients who deemed to have high BCIS-JS.

The proportion of diabetic patients was 35%. There were no significant differences between diabetic and non-diabetic patients in clinical presentation, co-morbidities, or gender; although non-diabetic patients were older (73 ±11 vs. 70 ±11, P= 0.001) with lower body mass index (27 ±5 vs. 31 ±7, P< 0.001). The percentage of previous stroke (13% vs. 6%) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (20% vs. 11%, P= 0.043) was also higher in non-diabetic compared to non-diabetic. Procedural complexity was comparable between diabetic and non-diabetic in relation to left main intervention, number of attempted lesions, number of stents, syntax score, and BCIS-JS score. Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

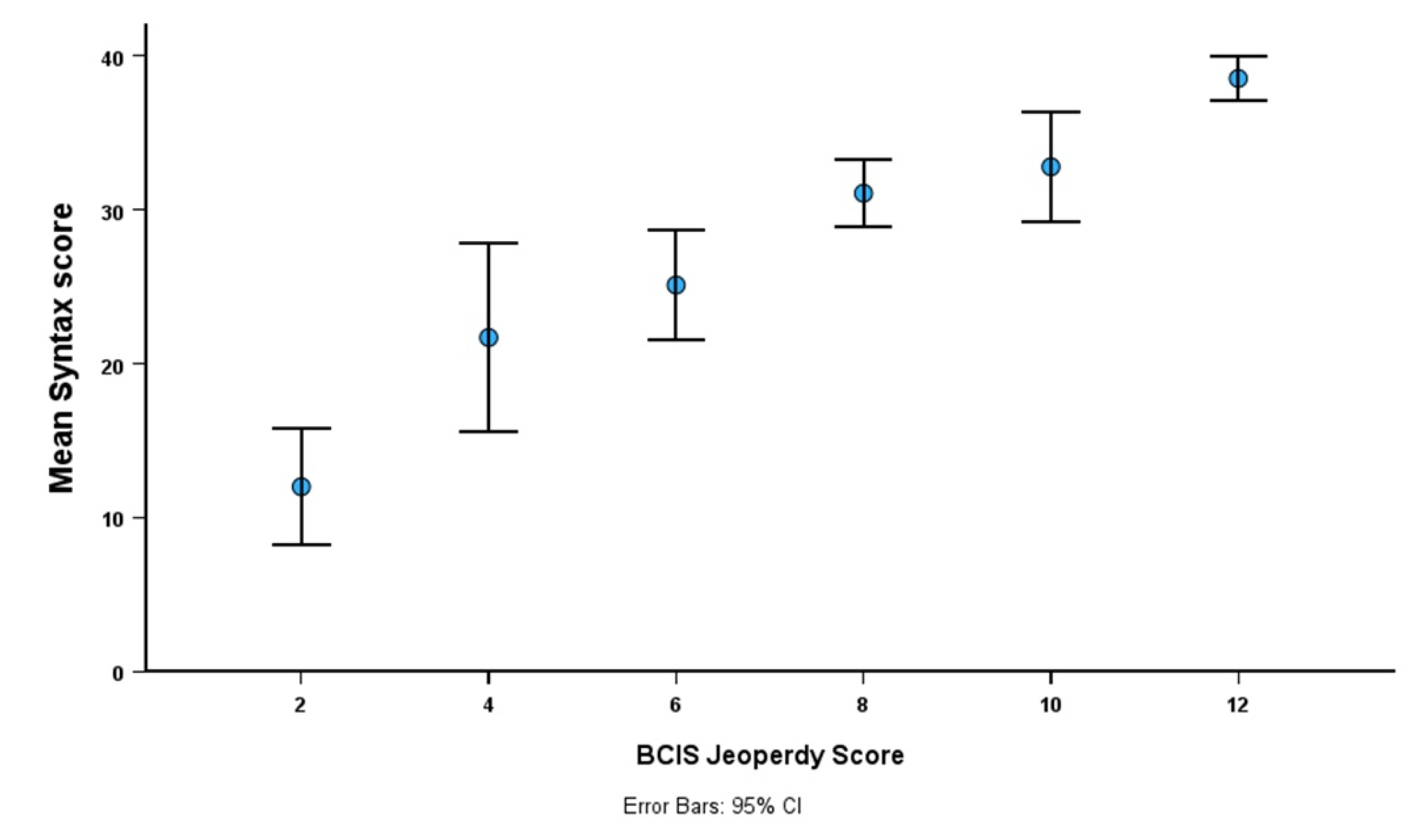

In the whole cohort, there was a modest relationship between BCIS-JS and syntax score (Spearman r= 0.44, P< 0.001) and this relationship was even weaker in patients with diabetes (Spearman r= 0.32, P< 0.001). Notably, the variation in syntax scores was getting wider in patients with low compared to high BCIS-JS (

Figure 1).

The primary endpoint was reported in 55 patients (12.2%) in the whole cohort. There was no difference between diabetic and non-diabetic patients in procedural, in-hospital, one month mortality, or one-year mortality (

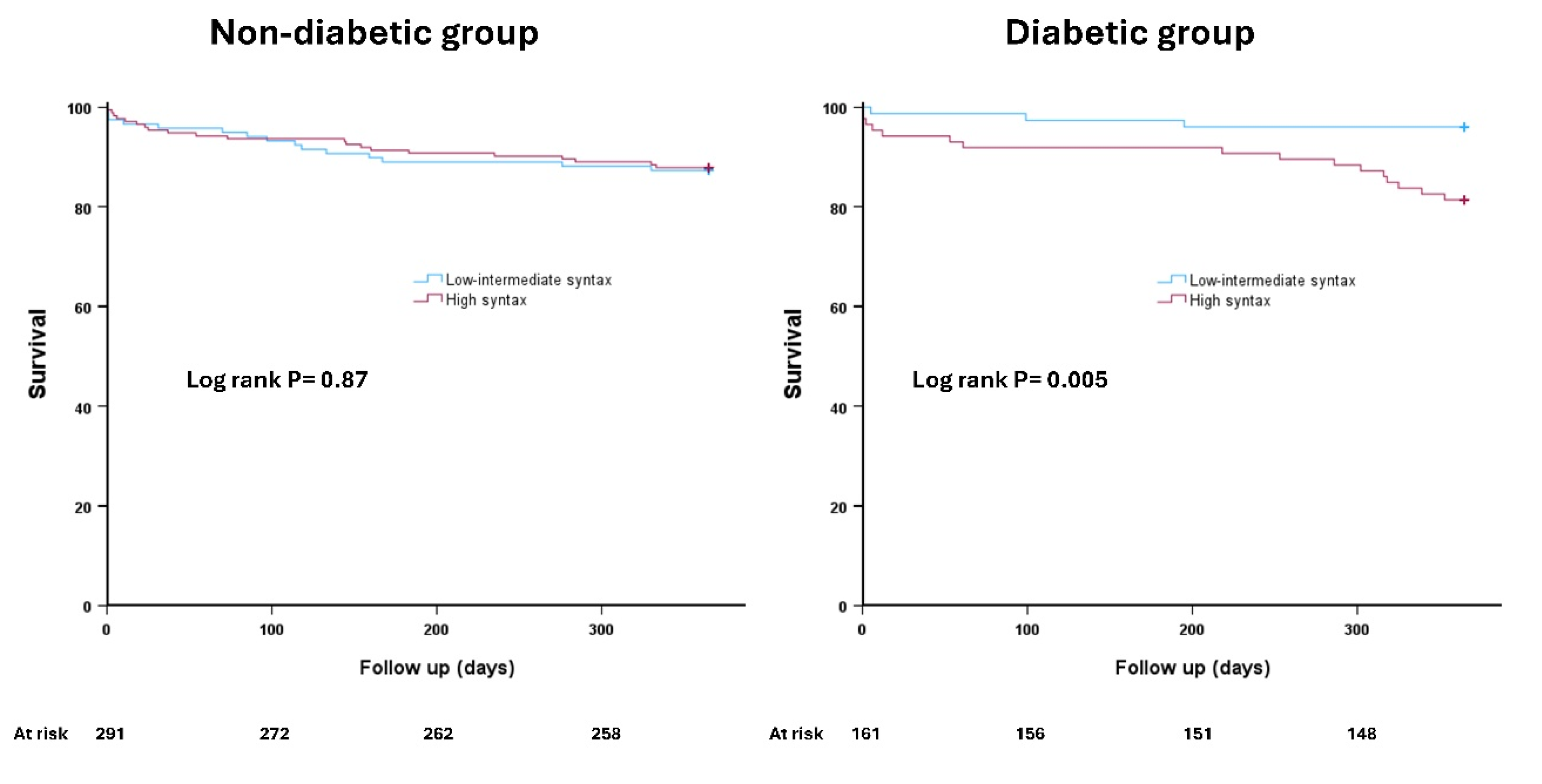

Table 2). The primary endpoint was comparable in the non-diabetic group irrespective of the used score to define complex CAD. Non-diabetic patients with high syntax had similar mortality rate at 12 months compared to those with low syntax score [12.1% vs. 12.7%, hazard ration (HR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.49- 1.84), P= 0.87] (

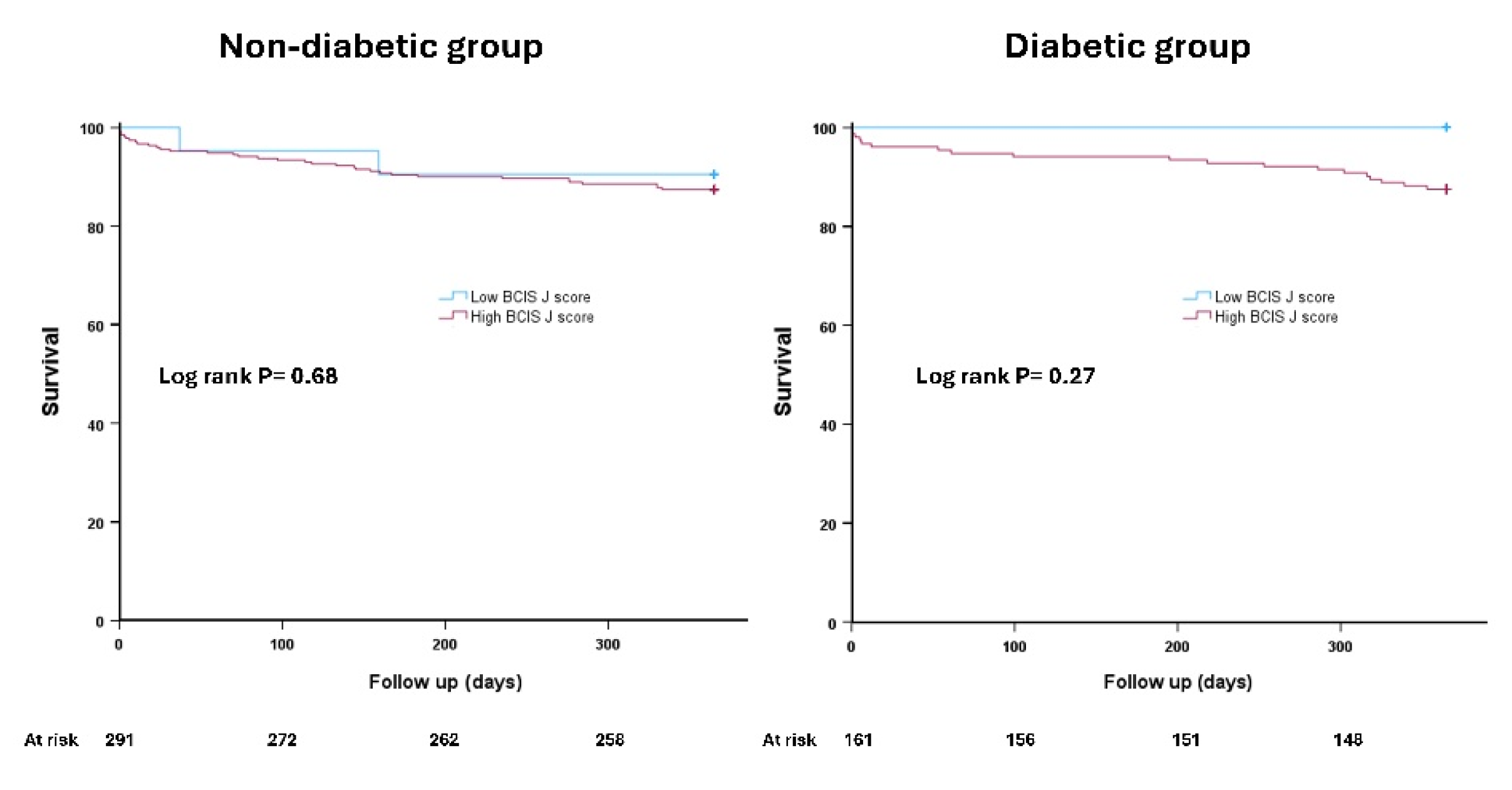

Figure 2). Likewise, non-diabetic patients with high versus low BCIS-JS had similar incidence of the primary endpoint [12.6% vs. 9.5%, HR 1.35 95% CI (0.32- 5.61), P=0.68] (

Figure 3).

On the other hand, there was a differential prognostic outcome in the diabetic group. The primary endpoint was more frequently reported in diabetic patients with high versus low syntax score [18.6% vs. 4.0%, HR 4.96, 95% CI (1.44- 17.03), P= 0.011] (

Figure 2). This observation was not evident in diabetic patients with high versus low BCIS-JS [12.5% vs. 0%, HR 22.04, 95% CI (0.01- 101.41, P= 0.47] (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The main findings of our study can be summarised as follows: 1) there was no difference in procedural, in-hospital or one year mortality between diabetic and non-diabetic patients; 2) there was differential prognostic outcome using syntax score according to diabetic status; 3) high BCIS-JS did not differentiates patients at increased risk of mortality in both non-diabetic as well as diabetic patients.

Diabetes remains a major challenge for patients with complex CAD undergoing revascularization, particularly with PCI [

9,

21]. Poor glycemic control was associated with higher stent failure and risk of restenosis in diabetic patients [

14,

21]. Additionally, the quality of life in patients who underwent PCI remained sub-optimal compared to patients who underwent CABG [

22]. Interestingly, our study did not highlight worse clinical outcomes in diabetic versus non-diabetic patients. Importantly, there was no difference in the complexity of CAD between the two groups using either syntax or BCIS-JS scores. Of note, our cohort included high-risk surgical turned down patients with potentially competitive risk for mortality in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

The relationship between BCIS-JS and syntax was only modest. There are anatomical factors that are included in the calculation of syntax score that are not included in the BCIS-JS. Features such as lesion length, tortuosity, and calcifications are recognised to add procedural complexity but not included in the BCIS-JS. Additionally, the presence of chronic total occlusion has differential impact on the two scoring systems, and it significantly increases the syntax scoring more than the BCIS-JS. The degree of stenosis for any lesion that is required to be included is also different between the two scoring systems [

3].

The primary endpoint, defined as mortality at 12 months, was only significantly different in patients with diabetes using syntax score. Unlike BCIS-JS, diabetic patients with high syntax score had five folds more likelihood of death at 12 months compared to those with low syntax score. This observation was not evident when using BCIS-JS to define complex CAD in diabetic patients. Whilst type 1 error remains a possibility given the relatively low number of diabetic patients and low BCIS-JS, potential biological reasons may explain our findings. Diabetic patients tend to have large plaque burden, more diffuse, tortuous and calcified CAD [

23]. The prevalence of chronic total occlusion is higher in diabetic patients and is associated with worse clinical outcomes in diabetic versus non-diabetic [

24,

25,

26]. These feature of atherosclerotic disease in diabetes will inevitably contribute to long-term outcomes but more importantly are captured within the syntax scoring. Additionally, such plaque characteristics will add more procedural complexity related to lesion preparation, stent delivery and optimisation. Collectively, this will result in sub-optimal stent results and high likelihood of stent failure and major adverse cardiovascular events. In contrast, the BCIS-JS predominately encompass lesion locations without any granularity of other features of anatomical complexity. Our findings may have important clinical implications for risk stratification and treatment planning in patients with diabetes undergoing PCI for complex CAD. While the BCIS-JS has shown prognostic value in general PCI populations, including those with previous CABG, our results suggest that it may not be as effective in diabetic patients with high-risk features. Clinicians should exercise caution when using the BCIS-JS alone for risk assessment in this specific patient group.

Both BCIS-JS and syntax did not provide prognostic insights in the non-diabetic group. The primary endpoint was comparable between the four subgroups (low versus high score of syntax and BCIS-JS). This may be related to the pre-defined primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, The difference in clinical outcomes must be of a large magnitude to reflect a difference in mortality. Therefore, the complexity of CAD in non-diabetic patients does not appear to be a decisive factor in determining death at 12 months. The mortality rate was between 9-12% across the four sub-groups and the role of BCIS-JS and syntax was relatively limited in non-diabetic patients.

Our study has several limitations that need to be highlighted. This was a retrospective single centre analysis, and the results need to be interpreted within the inherent limitation of the study’s design. Our study did not collect data on medical treatments, including antiplatelet, lipid-lowering drugs, and diabetic treatment. The primary endpoint did not include risk of myocardial infarction and unplanned revascularization. This did not allow deep dive analysis of the role of BCIS-JS and syntax scoring in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

5. Conclusions

There was a modest relationship between BCIS-JS and syntax score. Unlike, BCIS-JS, syntax score identified patients who are at increased risk of death in diabetic patients. Both scoring system did not effectively differentiate the mortality risk in non-diabetic patients. Future research is needed to confirm this study’s findings.

References

- Diseases GBD and Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204-1222.

- Wykrzykowska JJ, Garg S, Girasis C, de Vries T, Morel MA, van Es GA, Buszman P, Linke A, Ischinger T, Klauss V and et al. Value of the SYNTAX score for risk assessment in the all-comers population of the randomized multicenter LEADERS (Limus Eluted from A Durable versus ERodable Stent coating) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56:272-277. [CrossRef]

- Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Stahle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ, Van Dyck N, Leadley K, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW and Investigators S. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961-72. [CrossRef]

- De Silva K, Morton G, Sicard P, Chong E, Indermuehle A, Clapp B, Thomas M, Redwood S and Perera D. Prognostic utility of BCIS myocardial jeopardy score for classification of coronary disease burden and completeness of revascularization. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:172-7. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Ahn JM, Kim JH, Jeong YJ, Hyun J, Yang Y, Lee JS, Park H, Kang DY, Lee PH, Park DW, Park SJ and on the behalf of the PI. Prognostic Effect of the SYNTAX Score on 10-Year Outcomes After Left Main Coronary Artery Revascularization in a Randomized Population: Insights From the Extended PRECOMBAT Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020359. [CrossRef]

- Califf RM, Phillips HR, 3rd, Hindman MC, Mark DB, Lee KL, Behar VS, Johnson RA, Pryor DB, Rosati RA, Wagner GS and et al. Prognostic value of a coronary artery jeopardy score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:1055-63.

- Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, Greenwood JP, Weerackody R, Ryan M, Morgan HP, Dodd M, Evans R, Canter R, Arnold S, Dixon LJ, Edwards RJ, De Silva K, Spratt JC, Conway D, Cotton J, McEntegart M, Chiribiri A, Saramago P, Gershlick A, Shah AM, Clark AL, Petrie MC and Investigators R-B. Percutaneous Revascularization for Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1351-1360. [CrossRef]

- Perera D, Clayton T, Petrie MC, Greenwood JP, O’Kane PD, Evans R, Sculpher M, McDonagh T, Gershlick A, de Belder M, Redwood S, Carr-White G, Marber M and investigators R. Percutaneous Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction: Rationale and Design of the REVIVED-BCIS2 Trial: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:517-526.

- Fuster V and Farkouh ME. Main Results of the Future REvascularization evaluation in patients with diabetes mellitus: optimal management of multivessel disease (FREEDOM) trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2779. [CrossRef]

- Alkhalil M, McCune C, McClenaghan L, Mailey J, Collins P, Kearney A, Todd M and McKavanagh P. Clinical Outcomes of Deferred Revascularisation Using Fractional Flow Reserve in Diabetic Patients. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:897-902. [CrossRef]

- Fearon WF, Zimmermann FM, Ding VY, Takahashi K, Piroth Z, van Straten AHM, Szekely L, Davidavicius G, Kalinauskas G, Mansour S, Kharbanda R, Ostlund-Papadogeorgos N, Aminian A, Oldroyd KG, Al-Attar N, Jagic N, Dambrink JE, Kala P, Angeras O, MacCarthy P, Wendler O, Casselman F, Witt N, Mavromatis K, Miner SES, Sarma J, Engstrom T, Christiansen EH, Tonino PAL, Reardon MJ, Otsuki H, Kobayashi Y, Hlatky MA, Mahaffey KW, Desai M, Woo YJ, Yeung AC, Pijls NHJ and De Bruyne B. Outcomes after fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting (FAME 3): 5-year follow-up of a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Choi KH, Park TK, Song YB, Lee JM, Lee JY, Lee SJ, Lee SY, Kim SM, Yun KH, Cho JY, Kim CJ, Ahn HS, Yoon HJ, Park YH, Lee WS, Jeong JO, Song PS, Doh JH, Jo SH, Yoon CH, Kang MG, Koh JS, Lee KY, Lim YH, Cho YH, Cho JM, Jang WJ, Chun KJ, Hong D, Yang JH, Choi SH, Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Nam CW and Investigators RC-P. Intravascular Imaging and Angiography Guidance in Complex Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Among Patients With Diabetes: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2417613.

- Kuzemczak M, Ibrahem A and Alkhalil M. Colchicine in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease with or Without Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Clin Drug Investig. 2021;41:667-674. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pardo I, Andersson Franko M, Lagerqvist B, Ritsinger V, Eliasson B, Witt N, Norhammar A and Nystrom T. Glycemic Control and Coronary Stent Failure in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:260-272. [CrossRef]

- Farag M, Al-Atta A, Abdalazeem I, Salim T, Alkhalil M and Egred M. Clinical outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in high-risk patients turned down for surgical revascularization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100:360-366. [CrossRef]

- Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Falk V, Head SJ, Juni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ, Seferovic PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO and Group ESCSD. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165. [CrossRef]

- Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthelemy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, Dendale P, Dorobantu M, Edvardsen T, Folliguet T, Gale CP, Gilard M, Jobs A, Juni P, Lambrinou E, Lewis BS, Mehilli J, Meliga E, Merkely B, Mueller C, Roffi M, Rutten FH, Sibbing D, Siontis GCM and Group ESCSD. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1289-1367. [CrossRef]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD and Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology /American College of Cardiology /American Heart Association /World Heart Federation Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial I. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618-e651.

- Esper RB, Ribeiro EE, Hueb W, Domanski M, Hamza T, Siami S, Farkouh ME and Fuster V. The role of the syntax score in predicting clinical outcome in diabetic patients after percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass graft: a freedom trial sub-analysis. Circulation. 2017;136.

- Esper RB, Farkouh ME, Ribeiro EE, Hueb W, Domanski M, Hamza TH, Siami FS, Godoy LC, Mathew V, French J and et al. SYNTAX Score in Patients With Diabetes Undergoing Coronary Revascularization in the FREEDOM Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72:2826-2837. [CrossRef]

- Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, Siami FS, Dangas G, Mack M, Yang M, Cohen DJ, Rosenberg Y, Solomon SD and et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:2375-2384. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah MS, Wang K, Magnuson EA, Spertus JA, Farkouh ME, Fuster V and Cohen DJ. Quality of life after PCI vs CABG among patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1581-1590.

- Gebert ZM, Kwiecinski J, Weir-McCall JR, Adamson PD, Mills NL, Roditi G, van Beek EJR, Nicol ED, Berman DS, Slomka PJ, Dweck MR, Dey D, Newby DE and Williams MC. Impact of diabetes mellitus on coronary artery plaque characteristics and outcomes in the SCOT-HEART trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2025.

- Latif A, Ahsan MJ, Kabach A, Kapoor V, Mirza M, Ahsan MZ, Kearney K, Panaich S, Cohen M and Goldsweig AM. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Chronic Total Occlusions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;37:68-75. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Parachini JR, Karatasakis A, Karmpaliotis D, Alaswad K, Jaffer FA, Yeh RW, Patel M, Bahadorani J, Doing A, Nguyen-Trong PK, Danek BA, Karacsonyi J, Alame A, Rangan BV, Thompson CA, Banerjee S and Brilakis ES. Impact of diabetes mellitus on acute outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in chronic total occlusions: insights from a US multicentre registry. Diabet Med. 2017;34:558-562.

- Konstantinidis NV, Werner GS, Deftereos S, Di Mario C, Galassi AR, Buettner JH, Avran A, Reifart N, Goktekin O, Garbo R, Bufe A, Mashayekhi K, Boudou N, Meyer-Gessner M, Lauer B, Elhadad S, Christiansen EH, Escaned J, Hildick-Smith D, Carlino M, Louvard Y, Lefevre T, Angelis L, Giannopoulos G, Sianos G and Euro CTOC. Temporal Trends in Chronic Total Occlusion Interventions in Europe. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e006229. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).