1. Introduction

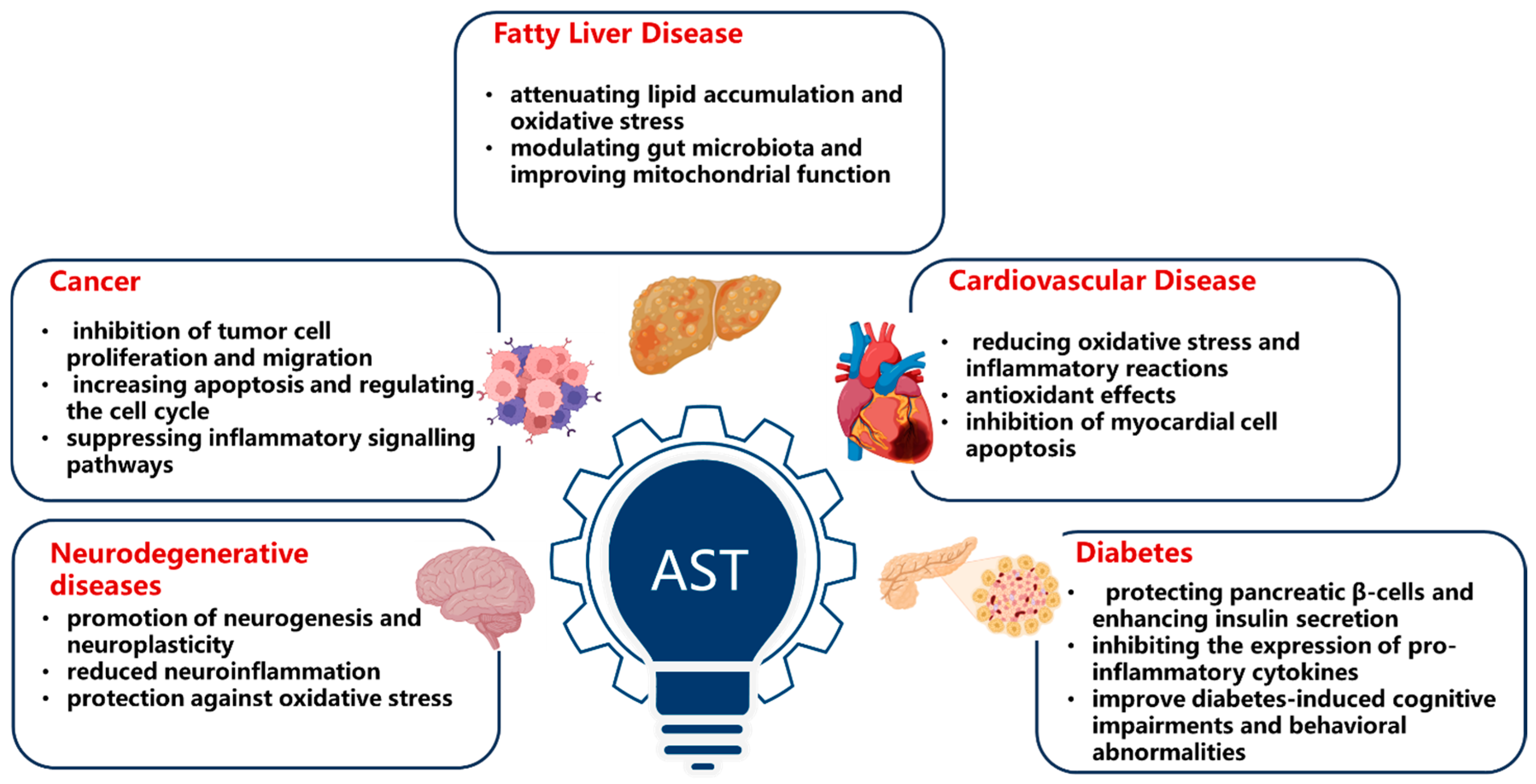

Astaxanthin, a powerful carotenoid pigment primarily found in aquatic organisms, has gained recognition for its potential medicinal benefits in preventing and managing chronic diseases. This natural compound offers a range of protective effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, immune-regulatory, and anti-tumor properties. These effects make it effective in preventing and protecting against several chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, liver diseases, and cancer, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

These diseases are often associated with prolonged inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage. Recent research indicates that astaxanthin may be a viable natural compound to help modulate the pathophysiological processes linked to irreversible complications of disease progression. This offers a novel approach to enhancing quality of life through disease prevention and management.

2. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Cellular Protection

Astaxanthin is an antioxidant that has been extensively studied for its ability to neutralize singlet oxygen, a reactive oxygen species known to cause cellular damage. The antioxidant properties of astaxanthin lead to its anti-inflammatory actions. By mitigating oxidative stress — a key factor in many chronic diseases — astaxanthin enhances cellular resilience against oxidative damage.

Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms of astaxanthin’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, highlighting its role in reducing oxidative stress and inflammation at the cellular level.

2.1. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties

In diabetic patients, astaxanthin significantly reduces oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde and interleukin-6, demonstrating its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

1]. Similarly, studies demonstrate that astaxanthin effectively lowers levels of malondialdehyde and isoprostane in overweight and obese individuals, further confirming its capacity to combat oxidative stress [

2]. These results are consistent with astaxanthin’s ability to quench and neutralize singlet oxygen, a key contributor to oxidative damage.

The anti-inflammatory actions of astaxanthin are closely linked to its antioxidant properties. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that astaxanthin suppresses oxidative stress and the production of inflammatory factors in LPS-induced dendritic cells via the HO-1/Nrf2 pathway. This comprehensive antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects suggest its potential for treating various diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation.

The comprehensive antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin suggest its potential for treating various diseases associated with oxidative stress and inflammation. Its ability to modulate mitochondrial function and immune cell activity further underscores its therapeutic versatility. Future research should focus on optimizing astaxanthin delivery systems to enhance its bioavailability and explore its long-term effects in clinical settings. In conclusion, astaxanthin’s robust antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, coupled with its cellular protective mechanisms, position it as a valuable adjuvant therapeutic agent for mitigating diseases related to oxidative stress.

2.2. Cellular Protection Mechanisms

Recent studies have revealed diverse mechanisms of action that underscore its effectiveness in cellular protection. Astaxanthin provides cellular protection by activating the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway, which promotes the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase [

3]. This activation enhances the cell’s antioxidant defense system, reducing oxidative damage. It modulates mitochondrial function by decreasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which protects cells from oxidative stress-induced damage. For instance, astaxanthin has been shown to promote mitochondrial biogenesis and enhance energy metabolism in muscle cells through the AMPK/Sirtuins/PGC-1α pathway [

4]. In vitro studies demonstrated that astaxanthin can significantly reduce ROS generation, particularly in cells exposed to oxidative stressors such as hydrogen peroxide. For example, nanoparticles containing astaxanthin have been shown to decrease ROS levels in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mitochondrial-targeted astaxanthin nanoparticles exhibit an even more pronounced protective effect [

5]. This suggests that astaxanthin’s ability to target mitochondria enhances its efficacy in reducing ROS production and protecting mitochondrial integrity.

Table 1.

Antioxidant, cellular protection and anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin.

Table 1.

Antioxidant, cellular protection and anti-inflammatory effects of astaxanthin.

| Mechanism |

Study Population/Model |

Key Findings |

Reference |

| Antioxidant Properties |

Diabetic patients |

Significant reduction in malondialdehyde and interleukin-6 levels, highlighting potent antioxidant effects |

Feng et al.

(2018) [1] |

| Overweight/obese individuals |

Effective lowering of malondialdehyde and isoprostane levels, confirming oxidative stress reduction |

Choi et al. (2011) [2] |

Cellular Protection

|

Muscle cells |

Activation of AMPK/Sirtuins/PGC-1α pathway, upregulation of antioxidant enzymes |

Lewis et al. (2022) [4] |

| RAW 264.7 macrophages |

Mitochondrial-targeted astaxanthin nanoparticles reduce ROS levels, enhance mitochondrial integrity |

Mei et al. (2019) [5] |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects |

LPS-induced dendritic cells |

Suppression of oxidative stress and inflammatory factor production via HO-1/Nrf2 pathway |

Yin et al.

(2021) [6] |

3. Immune Regulatory Effect

Recent studies have demonstrated that astaxanthin can modulate the immune system. It influences immune cells, especially dendritic cells, by inhibiting their maturation and the release of inflammatory factors. This effect occurs through the inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway, which subsequently reduces the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α [

7]. Moreover, astaxanthin modulates the function of immune cells, such as dendritic cells, by inhibiting their maturation and the secretion of inflammatory factors [

8]. This regulatory effect on immune cells is crucial for controlling inflammation. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that astaxanthin suppresses oxidative stress and inflammatory factor production in LPS-induced dendritic cells via the HO-1/Nrf2 pathway [

6], enhances defense mechanisms against pathogens, and reduces the incidence of autoimmune diseases. Extensive studies have elucidated the multifaceted mechanisms by which astaxanthin regulates the immune system, contributing to anti-infection, anti-inflammatory, and immune-modulatory effects, as summarized in

Table 2.

A recent study demonstrated that astaxanthin significantly enhances both cellular and humoral immunity in mice [

9]. Specifically, it promotes the proliferation and transformation of splenic lymphocytes, increases serum hemolysin levels, and enhances the activity of antibody-producing cells. Additionally, astaxanthin significantly improves the carbon clearance rate in mice, indicating its capacity to bolster non-specific immune functions. These findings suggest that astaxanthin can fortify the body’s defense against pathogens by modulating immune cell activity and function. Besides, Li et al. [

10] uncovered a novel mechanism by which Astaxanthin enhances antiviral responses via inhibiting STING carbonylation. STING, a pivotal protein in the DNA-sensing pathway, is crucial for antiviral immunity. Their study revealed that Astaxanthin mitigates lipid peroxidation and inflammation induced by HSV-1 while augmenting type I interferon production, thereby restricting viral replication. This highlights the potential of Astaxanthin to enhance antiviral defenses by modulating the STING signaling pathway. He et al. [

11] explored the potential of astaxanthin to modulate immune responses in a mouse model of autoimmune hepatitis induced by Concanavalin A. They observed that astaxanthin significantly alleviated liver damage and downregulated pro-inflammatory cytokines. Mass cytometry and single-cell RNA sequencing analyses revealed a substantial increase in CD8+ T cells in the liver following Astaxanthin treatment, with downregulated expression of functional markers, such as CD69, MHC II, and PD-1. Specific CD8+ T cell subclusters (subclusters 4, 13, 24, and 27) exhibited distinct changes in marker gene expression, suggesting that Astaxanthin may mitigate AIH by modulating the quantity and function of CD8+ T cells.

Despite the promising immunomodulatory effects of astaxanthin, inconsistencies across studies highlight the complexity of its mechanisms. For instance, Nieman et al. [

12] reported that although astaxanthin supplementation did not significantly reduce exercise-induced muscle soreness, damage, or increases in plasma cytokines and oxylipins, it effectively counteracted the post-exercise decline in immune-related plasma proteins, particularly immunoglobulin IgM. This suggests that astaxanthin may play a role in modulating immune function under exercise-induced stress, although its effects may vary depending on the experimental design and conditions.

In summary, astaxanthin exhibits significant potential in modulating the immune system, enhancing defense mechanisms, and reducing the incidence of autoimmune diseases. Various studies have elucidated its mechanisms, including modulation of the STING signaling pathway, regulation of CD8+ T cell subclusters, and enhancement of immune cell activity. However, the mechanisms underlying astaxanthin’s effects may differ under diverse physiological and pathological conditions. Future research is warranted to elucidate its specific mechanisms in immune regulation and to explore its clinical applications.

4. Anti-Apoptotic Effect and Nervous System Protection

Astaxanthin demonstrates its anti-apoptotic effects by regulating apoptosis-related signaling pathways, which is particularly significant in neurodegenerative diseases. As outlined in

Table 3, astaxanthin shows potential neuroprotective effects against diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

In Alzheimer’s disease, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are key pathological mechanisms that contribute to neuronal apoptosis. Recent studies show that astaxanthin inhibits H

2O

2-induced excessive mitophagy and apoptosis by modulating the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, thereby reducing oxidative stress-induced damage in neuronal cells [

13,

14]. This mechanism is crucial for protecting neurons from apoptosis and preserving cognitive function.

Animal studies have demonstrated that astaxanthin can enhance spatial memory performance by promoting neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. For example, astaxanthin has been shown to improve hippocampus-associated spatial memory by increasing the proliferation of neural progenitor cells and protecting them from oxidative damage [

15]. Additionally, astaxanthin’s ability to upregulate brain-derived neurotrophic factors and activate the ERK pathway may further support synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [

16]. In human studies, astaxanthin has been shown to reduce biomarkers associated with cognitive decline [

17]. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study found that astaxanthin supplementation (6 mg/day or 12 mg/day) for 12 weeks significantly lowered phospholipid hydroperoxide concentrations in erythrocytes and plasma. Elevated hydroperoxide levels are associated with dementia, suggesting that astaxanthin may have preventative capabilities for Alzheimer’s disease. However, this study did not directly measure memory improvement.

For Parkinson’s disease, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are. Similarly critical factors lead to the apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons. Astaxanthin can inhibit the activation of microglia and astrocytes, reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factors [

18]. This anti-inflammatory action may help alleviate neuroinflammation and protect dopaminergic neurons. Astaxanthin’s neuroprotective effects in Parkinson’s disease may also be attributed to its ability to modulate signaling pathways involved in neuronal survival and function. For instance, it can activate the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is crucial for neuronal protection and survival [

19]. Astaxanthin may enhance the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a key molecule for neuronal plasticity and repair. While preclinical studies have shown promising results, clinical trials specifically investigating astaxanthin’s effects in Parkinson’s disease patients are limited. However, the existing evidence suggests that astaxanthin could be a valuable adjunctive therapy for Parkinson’s disease, potentially improving motor symptoms and cognitive function. Future research should focus on long-term clinical trials to determine the optimal dosage, delivery methods, and therapeutic efficacy of astaxanthin in Parkinson’s disease patients.

Astaxanthin’s multifaceted neuroprotective effects, including its ability to inhibit amyloid-beta aggregation, reduce neuroinflammation, and protect against oxidative stress, position it as a valuable candidate for the prevention and adjuvant treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Its safety profile and ability to cross the blood-brain barrier further enhance its clinical potential. In conclusion, astaxanthin’s role in reducing oxidative stress and regulating apoptosis signaling pathways offers a promising avenue for adjuvant treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. While direct evidence in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease is still emerging, its mechanisms in other diseases provide a strong theoretical basis for its neuroprotective potential. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms of astaxanthin in these diseases and exploring its potential as an adjuvant therapeutic agent in clinical settings.

5. Anti-Tumor Effect

Astaxanthin is theorized to possess significant anti-tumor potential by inhibiting cancer cell growth and metastasis, as detailed in

Table 4. This compound regulates the tumor cell cycle, induces apoptosis, and exhibits particularly outstanding free radical-scavenging abilities, making it effective in cancer prevention. Notably, Shao et al. [

20] demonstrated that astaxanthin suppresses the proliferation of prostate cancer DU145 cells by downregulating STAT3 expression, thereby enhancing apoptosis rates. Similarly, Faraone et al. [

21] conducted a systematic review that underscored the anti-tumor activity of astaxanthin in colorectal cancer and melanoma, attributing its efficacy to the modulation of multiple molecular targets. This multi-target mechanism of action was further corroborated by Ni et al. [

22], who validated the inhibitory effects of astaxanthin on tumor growth in a PC-3 prostate cancer xenograft mouse model. Complementing these findings, Maoka et al. [

23] elucidated the antioxidant properties of astaxanthin and its capacity to scavenge peroxynitrite, thereby contributing to its anti-tumor and anticarcinogenic effects.

Astaxanthin has garnered significant attention for its potential preventive and therapeutic effects on various cancers. In colorectal cancer, astaxanthin significantly curtails tumor cell proliferation and migration. This effect is mediated by the regulation of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, resulting in reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Consequently, astaxanthin alleviates oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, inhibiting colorectal cancer progression. Moreover, the downregulation of Ki67 expression by astaxanthin further curtails the malignant proliferation of tumor cells, highlighting its potential as a preventive and therapeutic agent for colorectal cancer [

24]. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Xu and Jiang [

25] reported that astaxanthin exerts significant anti-tumor effects by inhibiting the proliferation, migration, and invasion of NPC C666-1 cells. This is achieved by suppression of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways, as evidenced by reduced levels of p-AKT, p-P65, and p-IκB. Astaxanthin upregulates miR-29a-3p expression and further inhibits these signaling pathways, thereby reinforcing its anti-tumor effects in NPC treatment. Besides, astaxanthin inhibits the proliferation and migration of esophageal cancer cells by upregulating PPARγ expression [

26]. This effect is complemented by the reduction of oxidative stress markers (e.g., MDA) and the enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities (e.g., SOD and CAT). These findings collectively suggest that astaxanthin holds significant potential to prevent esophageal cancer. In glioblastoma multiforme, Shin et al. [

27] observed a hormetic effect of astaxanthin, where low concentrations promoted cell proliferation, while high concentrations induced apoptosis. This dose-dependent effect highlights the complexity of astaxanthin’s role in GBM treatment. Furthermore, astaxanthin regulates the cell cycle by upregulating Cdk2 and p-Cdk2/3 expression while downregulating p53, thereby exerting its anti-tumor effects.

These studies underscore the multifaceted anticancer potential of astaxanthin across various cancer types. Its mechanisms involve inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and migration, promoting apoptosis, regulating the cell cycle, suppressing inflammatory signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK and NF-κB), and alleviating oxidative stress. Despite variations in its effects across different cancer types, the consistent anti-tumor potential of astaxanthin is evident. Future research should focus on elucidating the safety and efficacy of astaxanthin in clinical settings to establish its viability as a novel therapeutic option for cancer patients.

6. Liver Protection

Astaxanthin, a powerful carotenoid antioxidant, has gained significant attention for its potential protective effects on the liver, particularly in cases of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Evidence shows that astaxanthin mitigates liver injury through anti-inflammatory actions by inhibiting NF-κB activation, antioxidant effects by upregulating glutathione levels, and metabolic regulatory actions by modulating lipid metabolism pathways. A key focus is its ability to upregulate fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α).

In NAFLD, astaxanthin shows strong protective effects by reducing lipid accumulation and oxidative stress. For example, Wu et al. [

28] demonstrated that astaxanthin significantly decreased hepatic lipid deposition in models of NAFLD induced by a high-fat diet. This improvement was accompanied by enhanced mitochondrial function, attributed to the upregulation of FGF21 and PGC-1α. These findings highlight astaxanthin’s role in improving mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation, which can help slow the progression of NAFLD. Additionally, astaxanthin regulates the expression of critical genes involved in lipid metabolism, inhibiting the uptake and synthesis of fatty acids while promoting their oxidation, collectively leading to reduced hepatic lipid accumulation.

In the case of ALD, astaxanthin alleviates alcohol-induced liver injury by modulating gut microbiota and improving mitochondrial function. Liu et al. [

29] demonstrated that astaxanthin significantly altered the gut microbiota composition, reducing the abundance of pro-inflammatory bacteria while increasing beneficial species such as

Akkermansia muciniphila. This shift in microbiota composition was associated with improved gut barrier function, reduced systemic inflammation, and a decrease in alcohol-induced liver damage. Furthermore, Krestinina et al. [

30] clarified astaxanthin’s protective effects against alcohol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Their study demonstrated that astaxanthin restored mitochondrial respiratory function and oxidative phosphorylation activity by up-regulating the expression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes, thereby reducing alcohol-induced hepatic injury.

Overall, these studies revealed the various protective mechanisms of astaxanthin in both NAFLD and ALD. It alleviates liver injury by decreasing oxidative stress and inflammation, enhancing mitochondrial function, upregulating FGF21 and PGC-1α, and modulating gut microbiota to improve gut barrier integrity. These findings position astaxanthin as a promising therapeutic candidate for managing NAFLD and ALD. Future research should focus on clarifying the detailed molecular pathways involved in astaxanthin’s protective effects on the liver and on exploring its clinical potential in human studies.

7. Anti-Fibrotic Effect

In recent years, astaxanthin, a natural carotenoid, has gained significant attention due to its remarkable antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. In particular, its potential in addressing fibrosis-related diseases has been highlighted. Astaxanthin inhibits renal fibrosis by modulating the Smad2, Akt, and STAT3 signaling pathways and pulmonary fibrosis by regulating long non-coding RNA and mitochondrial signaling pathways. These effects primarily involve the regulation of specific signaling pathways that suppress fibroblast activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

Studies have shown that astaxanthin can exert anti-fibrotic effects through multiple pathways. For instance, Diao et al. [

31] utilized a unilateral ureteral obstruction mouse model and found that astaxanthin significantly alleviated renal fibrosis. The mechanisms involved include the inhibition of fibroblast activation by modulating the Smad2, Akt, and STAT3 signaling pathways, as well as the suppression of EMT in renal tubular epithelial cells through the Smad2, Snail, and β-catenin pathways. Astaxanthin promotes the accumulation of CD8+ T cells in the kidneys by upregulating the expression of CCL5, thereby inhibiting renal fibrosis. Another study further revealed that astaxanthin mitigates renal fibrosis and peritubular capillary rarefaction by inhibiting the activation of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway. These findings suggest that astaxanthin holds potential therapeutic value in the treatment of renal fibrosis [

32].

Chen et al. [

33] demonstrated that astaxanthin can alleviate pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the proliferation and migration of activated fibroblasts through long non-coding RNA (lncITPF) and mitochondria-mediated signaling pathways. Specifically, astaxanthin suppresses the expression of lncITPF by inhibiting the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Smad3, thereby reducing the expression of its target gene ITGBL1. Moreover, astaxanthin promotes apoptosis of activated fibroblasts by regulating Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission. These discoveries elucidate the anti-fibrotic mechanisms of astaxanthin in pulmonary fibrosis, providing a theoretical basis for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Although these studies have revealed the anti-fibrotic effects of astaxanthin in different fibrosis models, there are some differences between them. For instance, in renal fibrosis, astaxanthin mainly exerts its effects by modulating cellular signaling pathways and immune cell infiltration, while in pulmonary fibrosis, its mechanisms focus more on regulating fibroblast behavior through lncRNA and mitochondrial signaling pathways. Additionally, despite the demonstrated anti-fibrotic potential of astaxanthin in various fibrosis models, its mechanisms of action may exhibit tissue-specific characteristics, which require further investigation.

In summary, as a natural anti-fibrotic compound, astaxanthin inhibits fibroblast activation and the EMT process through multiple mechanisms, showing promising therapeutic prospects in the treatment of renal fibrosis and pulmonary fibrosis. Future research is needed to explore the mechanisms of action in different fibrotic diseases and to evaluate the feasibility and safety of its clinical application.

8. Cardiovascular Health Improvement

Astaxanthin protects the cardiovascular system by reducing oxidative stress through the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and suppressing inflammatory reactions by inhibiting NF-κB activation. This dual action offers potential preventive and therapeutic effects on cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (

Table 5).

Mechanistically, astaxanthin has been shown to activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thereby significantly mitigating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [

34]. This action reduces damage to endothelial and neuronal cells. Additionally, astaxanthin enhances the expression of vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), strengthening intercellular junctions and further protecting endothelial cells from oxidative injury [

34]. In animal models, astaxanthin demonstrated the ability to improve vascular hyperpermeability following intracerebral hemorrhage and alleviate neurologic deficits, highlighting its potential therapeutic role in cerebrovascular diseases. In the realm of cardiomyopathy, astaxanthin has been found to attenuate chronic alcohol-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis, offering new insights into its applications for cardiovascular protection.

Preclinical studies have extensively documented the antioxidant capacity of astaxanthin, which is approximately 6000 times stronger than that of vitamin C [

35]. It effectively scavenges various ROS, including singlet oxygen and peroxyl radicals, and inhibits lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. Moreover, astaxanthin suppresses the activation of NF-κB, reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and thereby alleviating inflammatory responses. These findings indicate that astaxanthin protects the cardiovascular system not only through direct antioxidant effects but also by modulating cellular signaling pathways and inflammatory responses [

36].

In the clinical domain, the potential cardiovascular benefits of astaxanthin have been preliminarily confirmed. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial demonstrated that astaxanthin significantly reduced levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [

37] and total cholesterol, as well as cardiovascular risk markers such as fibrinogen, L-selectin, and fetuin A. Although the primary endpoint did not reach the predefined level of significance, these results suggest that astaxanthin, as a safe dietary supplement, can improve lipid profiles and cardiovascular risk markers, providing a novel approach for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

In summary, astaxanthin exerts protective effects on the cardiovascular system through multiple mechanisms, including antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory effects, apoptosis inhibition, and modulation of cellular signaling pathways. These findings not only highlight the potential therapeutic value of astaxanthin in cardiovascular diseases but also provide a theoretical foundation for future clinical research and drug development. However, despite the progress made, larger-scale and long-term clinical trials are still needed to validate the specific efficacy and safety of astaxanthin in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Table 5.

Cardiovascular health improvement of astaxanthin: evidence from animal studies.

Table 5.

Cardiovascular health improvement of astaxanthin: evidence from animal studies.

| Mechanism |

Study Population/Model |

Key Findings |

Reference |

| Antioxidant Properties |

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell |

Activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses |

Niu et al.

(2018) [34] |

| Anti-apoptotic Effect |

H9c2 cell and primary cardiomyocyte |

Protection of the heart from alcoholic cardiomyopathy partially by attenuating ER stress |

Wang et al.

(2021) [36] |

9. Anti-Diabetes Effect

Astaxanthin exerts therapeutic effects on diabetes and its complications through antioxidant actions that protect pancreatic β-cells and anti-inflammatory effects that reduce insulin resistance. Additionally, it can improve diabetes-induced behavioral abnormalities by reducing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the brain (

Table 6).

Hyperglycemia in diabetes triggers excessive production of ROS, leading to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction, insulin resistance, and endothelial cell damage. Astaxanthin has been shown to effectively scavenge ROS and reduce oxidative stress, thereby protecting pancreatic β-cells and enhancing insulin secretion [

38]. Additionally, astaxanthin regulates the expression of antioxidant-related genes and strengthens the endogenous antioxidant system, further mitigating oxidative damage to cells [

39]. These antioxidant effects are crucial for alleviating the oxidative burden associated with diabetes.

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a hallmark of diabetes and its complications. Astaxanthin has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), thereby reducing inflammation [

40]. This anti-inflammatory activity not only improves insulin resistance but also attenuates the progression of diabetic complications, including nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy [

41].

Diabetes is often associated with behavioral abnormalities, including cognitive decline, anxiety, and depression, which may be linked to oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Studies have shown that astaxanthin can improve diabetes-induced cognitive impairments and behavioral abnormalities by reducing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [

42,

43,

44]. For instance, in diabetic rat models, astaxanthin significantly enhanced cognitive function by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thereby alleviating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [

44].

10. Discussion and Conclusion

Astaxanthin, a naturally occurring carotenoid, has garnered significant attention for its potential as a therapeutic agent against chronic diseases. This review comprehensively summarized the mechanisms underlying the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, immunomodulatory, anti-tumor, and anti-fibrotic activities of astaxanthin. These multifaceted actions position astaxanthin as a promising natural compound managing various chronic conditions. Its ability to scavenge ROS and modulate oxidative stress-related gene expression confers neuroprotective effects against neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Additionally, astaxanthin’s capacity to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines and regulate inflammatory signaling pathways protects against chronic inflammatory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular diseases, while also offering anti-diabetic benefits.

Despite these promising findings, several limitations and challenges remain in the current research landscape. The precise mechanisms of action of astaxanthin are not yet fully elucidated, particularly regarding its specific targets and signaling pathways under different pathological conditions. Moreover, the relatively low bioavailability of astaxanthin poses a significant challenge, as it may limit its effective absorption and distribution in the body, thereby affecting its therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, most existing studies have been conducted in animal models or in vitro settings, with a scarcity of clinical trials, especially those investigating the long-term efficacy and safety of astaxanthin in human patients with chronic diseases.

Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms of astaxanthin, improving its bioavailability, and conducting large-scale clinical trials to validate its therapeutic potential. First, a deeper exploration of the molecular mechanisms of astaxanthin in various chronic diseases is warranted, particularly its targets and signaling pathways in neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders. Second, developing novel astaxanthin derivatives or nanocarriers to enhance its bioavailability and targeting capabilities could significantly improve its therapeutic potential. Third, more clinical trials are needed to validate the efficacy and safety of astaxanthin in human patients with chronic diseases and to determine its optimal dosing and administration protocols. Lastly, given the multi-target nature of astaxanthin, future studies should also investigate its potential for combination therapies to achieve synergistic effects.

In conclusion, astaxanthin holds good promise as a natural compound for preventing and treating various chronic diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z. and X.C.; writing—review and editing, M.W. and H.H; visualization, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| AFLD |

Alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| EMT |

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| FGF21 |

Fibroblast growth factor 21 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| MCP-1 |

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| NAFLD |

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| PGC-1α |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VE-cadherin |

Vascular endothelial cadherin |

References

- Feng, Y.; Chu, A.; Luo, Q.; Wu, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y. The Protective Effect of Astaxanthin on Cognitive Function via Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Brains of Chronic T2DM Rats. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.D.; Kim, J.H.; Chang, M.J.; Kyu-Youn, Y.; Shin, W.G. Effects of astaxanthin on oxidative stress in overweight and obese adults. Phytother Res 2011, 25, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, N.; Qin, T.; Zhou, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ma, B.; Xu, Z.; Li, C. Astaxanthin Provides Antioxidant Protection in LPS-Induced Dendritic Cells for Inflammatory Control. Mar Drugs 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis Luján, L.M.; McCarty, M.F.; Di Nicolantonio, J.J.; Gálvez Ruiz, J.C.; Rosas-Burgos, E.C.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M.; Iloki Assanga, S.B. Nutraceuticals/Drugs Promoting Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Biogenesis May Combat the Mitochondrial Dysfunction Driving Progression of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Su, S.; Zhu, J.; Geng, Y. Studies on Protection of Astaxanthin from Oxidative Damage Induced by H(2)O(2) in RAW 264.7 Cells Based on (1)H NMR Metabolomics. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 13568–13576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, N.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, B.; Sun, D.; Ma, B.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, C. Astaxanthin Protects Dendritic Cells from Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Immune Dysfunction. Mar Drugs 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, L.; Pesce, M.; Patruno, A.; Franceschelli, S.; Lutiis, M.A.; Grilli, A.; Felaco, M. Astaxanthin treatment reduced oxidative induced pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion in U937: SHP-1 as a novel biological target. Mar Drugs 2012, 10, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.M.; Kim, Y.J. Astaxanthin Treatment Induces Maturation and Functional Change of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor-Bearing Mice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Z. Study on the Enhancement of Immune Function of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jia, M.; Song, H.; Peng, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, W. Astaxanthin Inhibits STING Carbonylation and Enhances Antiviral Responses. J Immunol 2024, 212, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ding, M.; Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Tao, R.; Wu, Z.; Guo, W. Astaxanthin Alleviates Autoimmune Hepatitis by Modulating CD8(+) T Cells: Insights From Mass Cytometry and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analyses. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, 11, e2403148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, C.; Ma, W.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Li, J. Tea polyphenols, astaxanthin, and melittin can significantly enhance the immune response of juvenile spotted knifejaw (Oplegnathus punctatus). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2023, 138, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Ye, Q.; Qi, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Astaxanthin delays brain aging in senescence-accelerated mouse prone 10: inducing autophagy as a potential mechanism. Nutr Neurosci 2023, 26, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Ding, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, X.; Jia, G.; et al. Astaxanthin Inhibits H(2)O(2)-Induced Excessive Mitophagy and Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells by Regulation of Akt/mTOR Activation. Mar Drugs 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaghegh Shalmani, L.; Valian, N.; Pournajaf, S.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Dargahi, L.; Jorjani, M. Combination therapy with astaxanthin and epidermal neural crest stem cells improves motor impairments and activates mitochondrial biogenesis in a rat model of spinal cord injury. Mitochondrion 2020, 52, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Pan, W.; Lai, H. Astaxanthin alleviates pathological brain aging through the upregulation of hippocampal synaptic proteins. Neural Regen Res 2021, 16, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Kiko, T.; Miyazawa, T.; Carpentero Burdeos, G.; Kimura, F.; Satoh, A.; Miyazawa, T. Antioxidant effect of astaxanthin on phospholipid peroxidation in human erythrocytes. Br J Nutr 2011, 105, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, K.; Lou, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, W.; Li, R.; Geng, L.; Cheng, B. Astaxanthin ameliorates dopaminergic neuron damage in paraquat-induced SH-SY5Y cells and mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res Bull 2023, 202, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.M.; Cai, X.L.; Wen, Q.P. Astaxanthin reduces isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 4073–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.Q.; Zhao, Y.X.; Li, S.Y.; Qiang, J.W.; Ji, Y.Z. Anti-Tumor Effects of Astaxanthin by Inhibition of the Expression of STAT3 in Prostate Cancer. Mar Drugs 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, I.; Sinisgalli, C.; Ostuni, A.; Armentano, M.F.; Carmosino, M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D.; Labanca, F.; Khan, H. Astaxanthin anticancer effects are mediated through multiple molecular mechanisms: A systematic review. Pharmacol Res 2020, 155, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Shen, S. Astaxanthin Inhibits PC-3 Xenograft Prostate Tumor Growth in Nude Mice. Mar Drugs 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T.; Tokuda, H.; Suzuki, N.; Kato, H.; Etoh, H. Anti-oxidative, anti-tumor-promoting, and anti-carcinogensis activities of nitroastaxanthin and nitrolutein, the reaction products of astaxanthin and lutein with peroxynitrite. Mar Drugs 2012, 10, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, S.; Wang, F.; Li, C. Protective Effects of Astaxanthin against Oxidative Stress: Attenuation of TNF-α-Induced Oxidative Damage in SW480 Cells and Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis-Associated Cancer in C57BL/6 Mice. Mar Drugs 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, C. Astaxanthin suppresses the malignant behaviors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by blocking PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways via miR-29a-3p. Genes Environ 2024, 46, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, F.; Tian, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Lyu, Q. Antitumor Effects of Astaxanthin on Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by up-Regulation of PPARγ. Nutr Cancer 2022, 74, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, S.; Nakamura, S.; Maoka, T.; Yamada, T.; Imai, T.; Ohba, T.; Yako, T.; Hayashi, M.; Endo, K.; Saio, M.; et al. Antitumour Effects of Astaxanthin and Adonixanthin on Glioblastoma. Mar Drugs 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Mo, W.; Feng, J.; Li, J.; Yu, Q.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Ji, J.; Dai, W.; et al. Astaxanthin attenuates hepatic damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by up-regulating the FGF21/PGC-1α pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2020, 177, 3760–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J. Astaxanthin Prevents Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating Mouse Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestinina, O.; Odinokova, I.; Sotnikova, L.; Krestinin, R.; Zvyagina, A.; Baburina, Y. Astaxanthin Is Able to Prevent Alcohol-Induced Dysfunction of Liver Mitochondria. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Chen, W.; Cao, W.; Yuan, H.; Ji, H.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Guo, H.; et al. Astaxanthin protects against renal fibrosis through inhibiting myofibroblast activation and promoting CD8(+) T cell recruitment. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2019, 1863, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Meng, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Gao, M. Astaxanthin ameliorates renal interstitial fibrosis and peritubular capillary rarefaction in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Mol Med Rep 2019, 19, 3168–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Lv, C.; Xu, P.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, J. Astaxanthin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis through lncITPF and mitochondria-mediated signal pathways. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 10245–10250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, T.; Xuan, R.; Jiang, L.; Wu, W.; Zhen, Z.; Song, Y.; Hong, L.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; et al. Astaxanthin Induces the Nrf2/HO-1 Antioxidant Pathway in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells by Generating Trace Amounts of ROS. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Gasmi, A.; Lenchyk, L.; Shanaida, M.; Zafar, S.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Lysiuk, R.; Antonyak, H.; Noor, S.; Akram, M.; et al. The Role of Astaxanthin as a Nutraceutical in Health and Age-Related Conditions. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yan, X.; Weng, W.; Lu, X.; Zhang, C. Astaxanthin attenuates alcoholic cardiomyopathy via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cardiac apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2021, 412, 115378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Tang, N.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Low, T.Y.; Tan, S.C.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y. The effects of astaxanthin supplementation on obesity, blood pressure, CRP, glycemic biomarkers, and lipid profile: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res 2020, 161, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakayanathan, P.; Loganathan, C.; Thayumanavan, P. Astaxanthin-S-Allyl Cysteine Ester Protects Pancreatic β-Cell From Glucolipotoxicity by Suppressing Oxidative Stress, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and mTOR Pathway Dysregulation. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2024, 38, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qiao, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Xue, C. Hydrophilic Astaxanthin: PEGylated Astaxanthin Fights Diabetes by Enhancing the Solubility and Oral Absorbability. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 3649–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C.J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, X.Y.; Hu, X.T.; Chen, J.; Wen, X.R.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, K.Y.; Tang, R.X.; Song, Y.J. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Astaxanthin on the Sickness Behavior Induced by Diabetes Mellitus. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2015, 35, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwugu, O.N.; Glukhareva, T.V.; Danilova, I.G.; Kovaleva, E.G. Natural antioxidants in diabetes treatment and management: prospects of astaxanthin. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 5005–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, W.; Wang, C.X.; Xie, G.B.; Zhou, X.M.; Shi, J.X.; Zhou, M.L. Astaxanthin offers neuroprotection and reduces neuroinflammation in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Surg Res 2014, 192, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Qi, X. The Putative Role of Astaxanthin in Neuroinflammation Modulation: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 916653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ma, D.; Mulati, A.; Zhao, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, X. Development of astaxanthin-loaded layer-by-layer emulsions: physicochemical properties and improvement of LPS-induced neuroinflammation in mice. Food Funct 2021, 12, 5333–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).