1. Introduction

As consumers become increasingly health-conscious, their demand for food products that are not only nutritious but also promote overall well-being is reshaping the food industry. This shift has spurred interest in innovative ingredients that go beyond basic nutrition [

1]. Among the most promising are plant secondary metabolites—compounds like flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolic acids—which have gained attention for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and even anticancer properties (Anwar et al., 2019). These natural compounds are produced by plants as part of their defense mechanisms, helping them survive environmental stresses and ward off pathogens [

2]. Now, they’re being recognized for their potential to do the same for us, offering health benefits that could help prevent chronic diseases and improve quality of life.

As awareness grows, so does the concept of using food as medicine, where food is seen as a vehicle to deliver these beneficial compounds, offering long-term benefits with the potential of preventing diseases and, therefore, decreasing the use of medications [

3]. This idea has gained traction partly due to concerns about the side effects of conventional medicines and the environmental issues associated with pharmaceutical residues [

4,

5]. Incorporating plant secondary metabolites into everyday food products is a promising way to enhance their nutritional value while supporting health. Whether it is adding them to beverages, snacks, or supplements, the versatility of these compounds allows them to be tailored to different consumer needs and preferences [

6]. This adaptability is particularly important as more people look to manage or prevent health conditions like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease naturally [

7,

8,

9]

However, bringing these compounds into our diets isn’t without challenges. Their effectiveness depends on factors like bioavailability, and their stability during food processing and storage [

10,

11]. Additionally, regulatory hurdles must be navigated to ensure these products are safe and effective [

12,

13]. Consumer acceptance is another critical factor. Cultural habits, health awareness, and trust in natural products all play a role in how willing people are to embrace foods enriched with these plant-derived ingredients [

14,

15]. In some cultures, the use of plants for medicinal purposes is already well-established, making the transition to functional foods more straightforward. In others, education and clear, honest marketing will be key [

16].

Beyond health benefits, using these plant compounds also has environmental advantages. By sourcing them sustainably and reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals, the food industry can help mitigate environmental impacts, such as pharmaceutical pollution, which is becoming an increasingly serious issue [

17]. Moreover, many plants secondary metabolites can be extracted from agricultural by-products, turning waste into valuable resources. This approach not only supports environmental sustainability but also adds economic value to agricultural practices [

6,

18].

Looking ahead, the future of functional foods enriched with plant secondary metabolites is bright. Innovations in food technology, such as microencapsulation and nanotechnology, are opening new possibilities for improving the stability and bioavailability of these compounds [

19]. As the popularity of plant-based diets and sustainable food systems continues to grow, the development of functional foods that align with these trends seems both timely and promising.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the various types of plant secondary metabolites, their health benefits, and their applications in food technology. By examining the current state of research and innovation in this field, we seek to highlight the opportunities and challenges associated with the use of plant secondary metabolites in functional foods, offering insights into future directions for research and product development. As the food industry continues to evolve in response to consumer demands and environmental concerns, integrating plant secondary metabolites into functional foods represents a promising frontier in pursuing healthier, more sustainable diets.

2. Classification and Sources of Plant Secondary Metabolites

2.1. Overview

Secondary metabolites are organic compounds produced by algae, microorganisms, some animals, and plants to navigate both positive and negative interactions with their environment throughout evolutionary processes and different life stages. These compounds exhibit high structural diversity and, in some cases, biological redundancy. Based on their chemical origin, they are classified into major groups, including phenolic compounds, terpenoids, alkaloids, glycosides, sulfur-containing compounds, and non-alkaloid nitrogen-containing compounds. Secondary metabolites serve as a valuable source for medicine, agriculture, cosmetology and especially the food industry.

2.2. Key Classes of Plant Secondary Metabolites

2.2.1. Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds are a diverse group of secondary metabolites of plant origin, which have long been studied across various fields, ranging from organic chemistry to molecular biology. These compounds play a crucial role in defense against pathogens, UV radiation, and other environmental stress factors [

20,

21]. This family of compounds is synthesized through the shikimic acid pathway and the phenylpropanoid pathway. In the initial stage, before the synthesis of aromatic amino acids, phenolic acids (hydroxybenzoic acids) such as salicylic acid and gallic acid are synthesized from chorismic acid. The other group of phenolic compounds is synthesized from L-phenylalanine (or in some cases from L-tyrosine), with the enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) being the key enzyme in the pathway, catalyzing the conversion of phenylalanine into hydroxycinnamic acid, which is the precursor for phenylpropanoid acids, coumarins, flavonoids (including anthocyanins), stilbenoids, tannins, and lignin (including lignans) [

22]. These compounds are found in a wide variety of plant species, with relevance in edible plants such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, and legumes, although their concentrations can vary significantly depending on the species, cultivar, and environmental conditions.

In their natural function, phenolic compounds are primarily recognized for their potent antioxidant activity, which helps neutralize free radicals and protects plant cells from oxidative damage, as well as for their role as phytoalexins in the natural defense of plants, especially against bacterial and fungal infections [

20,

23,

24]. They also play a role in regulating growth and development, modulating hormonal signaling, and contributing to the coloration of flowers and fruits, which has an ecological role in attracting pollinators and facilitating seed dispersal. Additionally, they are involved in cell architecture through structural polymers like lignin and suberin [

25,

26,

27].

2.2.2. Terpenoids

Terpenoids (or isoprenoids) constitute one of the largest and most diverse classes of secondary metabolites in plants, encompassing a wide range of structures and functions. These compounds are synthesized through two primary biosynthetic pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, which occurs in the cytosol, and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway, which occurs in plastids [

28]. The MVA pathway primarily produces sesquiterpenes and triterpenes, while the MEP pathway forms monoterpenes, diterpenes, and tetraterpenes.

Smaller, more volatile terpenoids, such as monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, play key roles in plant-environment interactions [

29]. These compounds are often emitted as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and are crucial in attracting pollinators and deterring herbivores. These volatile terpenoids are also implicated in plant defense mechanisms, acting as deterrents to herbivores or as signaling molecules that trigger the production of other defensive compounds [

30].

Larger terpenoids, such as diterpenes and tetraterpenes, fulfill structural and functional roles within the plant. Diterpenes include compounds like gibberellins, which are plant hormones that regulate growth and development [

31], while tetraterpenes, including carotenoids, are responsible for pigmentation in many fruits and flowers, and play significant roles in photosynthesis by participating in light harvesting and photoprotection. Carotenoids are also precursors to important signaling molecules such as abscisic acid, which is involved in plant stress responses, regulating the opening and closing of stomata (Swapnil et al., 2021).

2.2.3. Alkaloids

Alkaloids are a diverse and biologically active class of secondary metabolites in plants, characterized by the presence of nitrogen atoms in their complex chemical structures. These compounds are primarily synthesized from amino acid precursors such as ornithine, lysine, tyrosine, and tryptophan through various biosynthetic pathways that often involve decarboxylation, methylation, and oxidation reactions [

32], and they exhibit significant specificity across different plant genera. The alkaloids produced by plants display a wide range of structures and functions, many of which play crucial roles in plant defense against herbivores and pathogens due to their potent bioactivity [

33], though their evolutionary role remains somewhat enigmatic and a subject of discussion [

34,

35].

Small alkaloids, such as nicotine and atropine, are well known for their strong physiological effects on both herbivores and humans. Nicotine, synthesized in the roots of tobacco plants and translocated to the leaves, acts as a powerful insecticide, deterring herbivory. Atropine, derived from tropane alkaloids in plants like deadly nightshade (

Atropa belladonna), is used medically as a muscle relaxant and in the treatment of certain types of poisoning. Larger and more complex alkaloids, such as vinblastine, an indole alkaloid, play significant roles in both plant defense and pharmaceutical applications, with vinblastine being widely used as an anticancer agent. Many authors have argued that these pharmacological roles derive from co-evolution with herbivores and that their mechanisms are precisely for defense, which is why many act so directly on the nervous system [

36,

37,

38,

39].

2.2.4. Glycosides

Glycosides are a highly diverse group of metabolites in plants, not only secondary metabolites, characterized by the presence of a sugar molecule attached to a non-sugar component known as the aglycone. These compounds play crucial roles in plant defense, growth regulation, and ecological interactions. Given the diversity of this group of metabolites, this section will focus on groups that were not discussed previously. This group of metabolites is classified based on the nature of their aglycones, which include steroids, triterpenes (triterpenoid saponins), and cyanogenic compounds [

40].

Steroid glycosides, such as cardiac glycosides, are known for their potent effects on the heart, as they alter the sodium-potassium pump in animal cells. These compounds, present in plants like

Digitalis spp., act as a chemical defense against herbivores due to their toxicity. Cardiac glycosides, such as digoxin, are also used medicinally to treat certain heart conditions, highlighting their dual role in plant defense and human health [

41].

Saponins (mainly triterpenoid), another class of glycosides, are widely found in many plant species, including legumes, and are recognized for their ability to form foamy solutions in water. These compounds exhibit a wide range of biological activities, such as antifungal, antibacterial, and insecticidal properties, contributing to plant protection.

Cyanogenic glycosides, found in plants such as cassava, peaches, apples, bamboo and bitter almonds, are another important group. These compounds release hydrogen cyanide when plant tissue is damaged, providing a potent defense mechanism against herbivores and pests. The presence of these glycosides requires careful processing of certain food crops to avoid toxicity, but they also have potential uses in pest control and are studied for their ecological significance [

41].

2.2.5. S-Containing Compounds

Sulfur-containing compounds, often referred to as S-containing compounds, are a diverse group of secondary metabolites in plants that play an important role in plant defense, growth regulation, and ecological interactions. These compounds are characterized by the presence of sulfur atoms in their molecular structures, which confer unique chemical properties and biological activities [

42,

43].

One of the best-known classes of sulfur-containing compounds is glucosinolates, which are primarily found in the Brassicaceae family, including crops like broccoli, cabbage, and mustard. When plant tissue is damaged, glucosinolates are hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase, leading to the formation of various bioactive compounds, including isothiocyanates, nitriles, and thiocyanates. These hydrolysis products are known for their pungent taste and strong odor, which act as deterrents to herbivores and pathogens. Moreover, isothiocyanates have been studied for their potential anticancer properties, making glucosinolates a topic of great interest in both agriculture and medicine [

44,

45].

Another important group of sulfur-containing compounds are thionins and defensins, which are small sulfur-rich peptides found in various plant species. These compounds exhibit strong antimicrobial activity, allowing plants to resist bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Thionins disrupt the membranes of invading pathogens, causing cell lysis and death. Their role in plant defense has been the subject of research in crop protection and biotechnology, where they are explored for their potential to enhance disease resistance in cultivated plants [

46,

47].

In summary, sulfur-containing compounds are vital components of plant secondary metabolism, with diverse roles in defense, ecological interactions, and potential applications in agriculture, medicine, and food technology. Their unique sulfur-based chemistry underpins their biological activity, making them a key focus of research and innovation across multiple fields.

2.2.6. Non-Alkaloid N-Containing Compounds

Nitrogen-containing compounds (non-alkaloids) represent a diverse and significant category of secondary metabolites in plants, incorporating nitrogen into their structures. These compounds play various roles in plant physiology, defense, and ecological interactions. Since cyanogenic glycosides and glucosinolates have already been discussed in detail previously, other interesting compounds include betalains and ureides.

Betalains are a group of nitrogen-containing compounds primarily found in the Caryophyllales order, which includes plants such as beets and amaranth. These water-soluble pigments are responsible for the vivid red, purple, and yellow colors in plants of this order, playing important ecological roles in attracting pollinators and seed dispersers. Betalains are divided into two main categories: betacyanins (red-violet pigments) and betaxanthins (yellow pigments). Beyond their role in pigmentation, betalains exhibit anti-inflammatory activity [

48], strong antioxidant properties, making them valuable natural colorants and functional ingredients in the food industry [

49,

50].

Ureides, such as allantoin and allantoic acid, are nitrogen-rich compounds involved in nitrogen transport and storage, particularly in leguminous plants. These compounds are crucial in nitrogen metabolism in plants that possess symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing organisms, enabling the efficient movement of nitrogen from the roots, where it is fixed, to other parts of the plant, where it supports growth and development.

In summary, nitrogen-containing compounds that are not alkaloids, such as glucosinolates, betalains, and ureides, are fundamental to plant survival and their interaction with the environment. Their roles in defense, pigmentation, and nitrogen metabolism highlight their significance in plant biology and their potential application in agriculture, food science, and nutrition.

3. Biological Activities of Plant Secondary Metabolites

Plant metabolites play a crucial role in human health and nutrition. From supporting the immune system and fighting inflammation to protecting against chronic conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, plant metabolites offer a natural avenue to prevent disease and enhance health. This disease-protecting capacity of plant metabolites is associated with their different biological activities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer, among others. In the following section, we review some of the most important biological activities associated with plant metabolites and their relationship with the prevention of chronic diseases.

3.1. Antioxidant Activity

Plants possess an extensive variety of antioxidants that protect them from oxidative damage under different environmental conditions [

51]. Phenolic compounds, one of the most studied metabolites from plants, exhibit strong free radical scavenging activity due to their ability to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons from their hydroxyl groups on the aromatic ring [

15,

23,

51], as well as their metal ion chelation and singlet oxygen quenching [

52]. The number and position of hydroxyl groups significantly influence their antioxidant capacity. For example, flavonoids with a catechol structure in the B-ring (such as quercetin) show higher antioxidant activity compared to those with a single hydroxyl group (such as apigenin) [

53].

Another group of metabolites with antioxidant properties are carotenoids, which are found in chloroplasts of green plant tissues and whose function is to protect the photosynthetic apparatus and reduce the reactivity of harmful oxidative species during photosynthesis [

54]. Due to their hydrophobic nature, carotenoids interact with radicals within cell membranes and lipoproteins [

54]. The structure of carotenoids, which include large carbon backbones with a system of conjugated double bonds, determines their antioxidant activity, which includes scavenging of singlet molecular oxygen (

1O

2) and peroxyl radicals [

54]. Additionally, in living organisms, carotenoids have been shown to activate Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor), a transcription factor that activates antioxidant response elements [

54].

The antioxidant properties of these compounds make them valuable not only for human health but also for food preservation. In the food industry, antioxidants derived from plant secondary metabolites are used to prevent lipid oxidation, which can lead to rancidity and loss of nutritional value in food products. The use of natural antioxidants is particularly appealing to consumers who seek clean-label products free from synthetic additives.

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory

Inflammation is a natural immune response to injury or infection; however, chronic inflammation is a contributing factor to many diseases, such as arthritis, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Plant secondary metabolites, particularly flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, have been extensively studied for their anti-inflammatory effects, which are attributed to their ability to modulate various signaling pathways involved in the inflammatory response.

Some flavonoids can inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes such as cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX), which are key mediators of inflammation [

55]. Quercetin, for example, has been shown to inhibit the expression of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in macrophages, thereby reducing the production of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and nitric oxide [

56,

57].

Certain classes of terpenoids, particularly sesquiterpenes and diterpenes, also exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties. Compounds such as α-bisabolol and β-caryophyllene have been shown to reduce inflammation by inhibiting the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) signaling pathway, which regulates the expression of various inflammatory genes [

58]. Additionally, some terpenoids can promote the resolution of inflammation by encouraging the removal of inflammatory cells and restoring tissue homeostasis.

Alkaloids, such as berberine and capsaicin, have also demonstrated interesting anti-inflammatory effects. Berberine found in plants like goldenseal and barberry, inhibits the activation of NF-kB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), both of which are involved in the inflammatory response. Capsaicin, the active component in hot chili peppers, exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by binding to the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor, which modulates pain and inflammation [

59,

60].

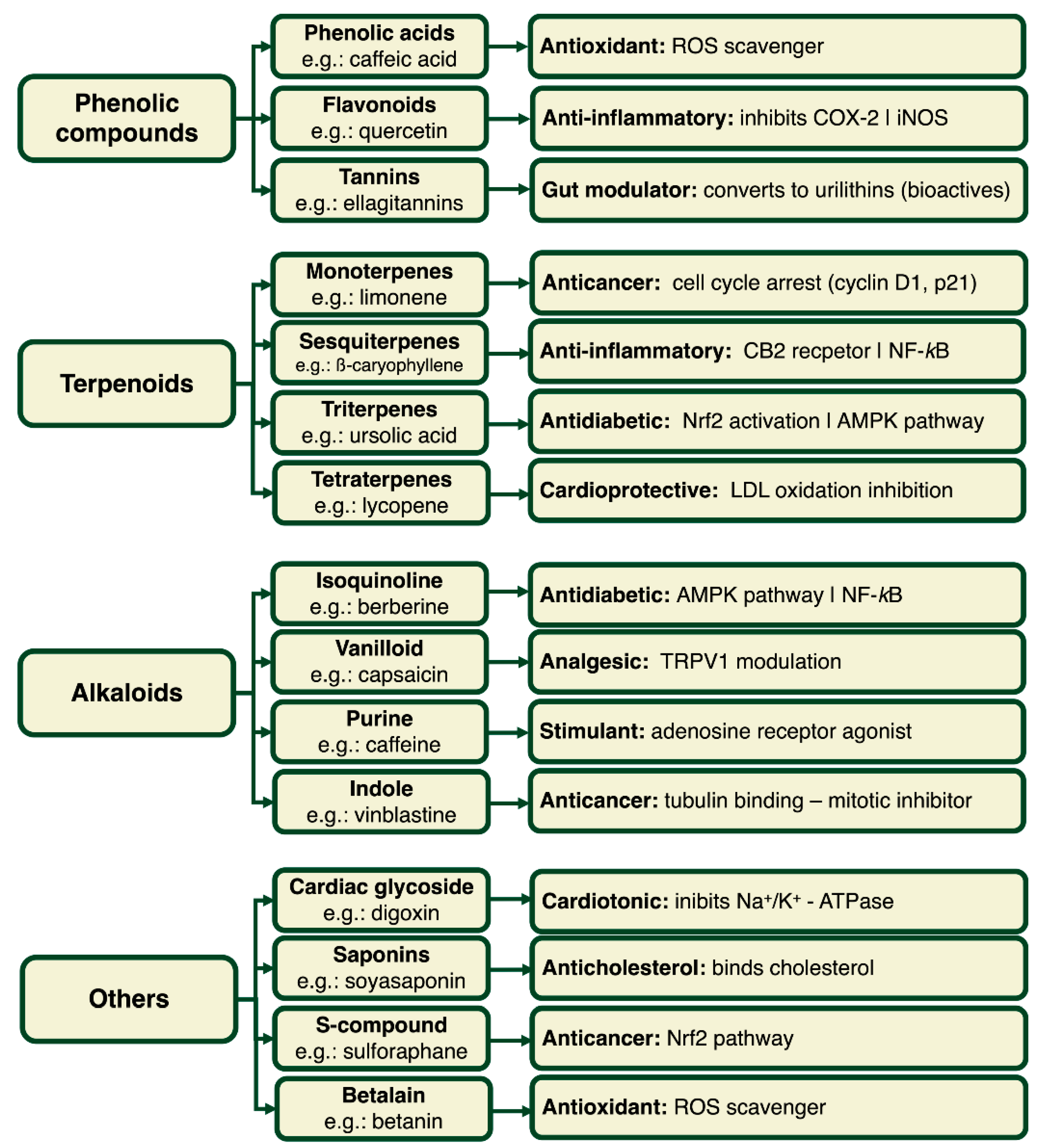

Figure 1 sumarizes the anti-inflammatory activity of some plant metabolites.

The anti-inflammatory effects of plant secondary metabolites are of particular interest in the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals aimed at managing chronic inflammatory conditions. By incorporating these bioactive compounds into the diet, it may be possible to reduce the risk of inflammation-related diseases and improve overall health [

61,

62].

3.3. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of certain plant secondary metabolites is another important health benefit, especially in the context of the growing problem of antibiotic resistance. It has been demonstrated that many plants secondary metabolites exhibit antimicrobial properties against a broad spectrum of pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Some phenolic compounds, such as tannins and flavonoids, exert their antimicrobial effects by altering microbial cell membranes, inactivating enzymes, and inhibiting nucleic acid synthesis. For example, tannins can bind to proteins and other macromolecules on the surface of microbial cells, leading to cell wall disruption and leakage of cellular contents, being particularly effective during the exponential growth phase when the highest rate of cell division is observed [

63,

64]. Flavonoids, such as catechins and epicatechins, can interfere with bacterial virulence factors, such as biofilm formation, and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria like

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus [

63,

64].

Terpenoids, especially from essential oils, are known for their strong antimicrobial activity [

65]. Compounds like thymol, carvacrol, and eugenol, which are found in the essential oils of thyme, oregano, and cloves, respectively, have been shown to alter microbial cell membranes, causing cell lysis and death. The lipophilic nature of these terpenoids allows them to integrate into the lipid bilayer of microbial membranes, increasing their permeability and causing the loss of vital cellular components [

66].

Alkaloids, such as berberine and sanguinarine, also exhibit antimicrobial properties. Berberine, for example, interferes with bacterial cell division by inhibiting the assembly of the FtsZ protein, which is essential for the formation of the bacterial cell division apparatus [

67]. Sanguinarine, found in plants like bloodroot and Mexican prickly poppy, shows strong antimicrobial activity by intercalating into DNA and inhibiting nucleic acid synthesis [

66].

The antimicrobial activity of plant secondary metabolites has significant implications for food safety and preservation. These compounds can be used as natural preservatives in food products to prevent microbial spoilage and extend shelf life [

68]. Additionally, the development of functional foods containing secondary metabolites with antimicrobial properties offers a promising approach to combating foodborne pathogens and reducing the risk of infectious diseases.

3.4. Anticancer Metabolites

The anticancer properties of plant secondary metabolites have garnered significant interest due to their potential to prevent and treat various types of cancer. These compounds can inhibit cancer development through multiple mechanisms, including the induction of apoptosis, inhibition of angiogenesis, and suppression of metastasis.

Various types of flavonoids, especially those found in fruits and vegetables, have been extensively studied for their anticancer effects. Quercetin, a common flavonoid in nature, present in apples, onions, and berries, has been shown to induce apoptosis in several cancer cell lines, including breast, colon, and prostate cancer cells [

69,

70]. This compound activates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis by increasing the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax and reducing the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2. Additionally, quercetin can inhibit angiogenesis by reducing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key molecule involved in the formation of new blood vessels [

68].

Some terpenoids also exhibit strong anticancer properties. Limonene has been shown to inhibit the growth of breast cancer cells by inducing cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. Limonene modulates the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins such as cyclin D1 and p21, leading to the accumulation of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle [

71]. In this way, limonene can enhance the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents by sensitizing cancer cells to apoptosis [

72].

Alkaloids are another important class of plant secondary metabolites with anticancer activity. Vinblastine and vincristine, alkaloids derived from the Madagascar periwinkle (

Catharanthus roseus), are widely used in chemotherapy to treat cancers such as Hodgkin's lymphoma and leukemia. These compounds inhibit cell division by binding to tubulin, thereby preventing the assembly of the mitotic spindle and halting cell division. Similarly, berberine has been shown to induce apoptosis in cancer cells by activating the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and inhibiting the NF-kB signaling pathway, which is involved in cell survival and inflammation [

73].

The potential of plant secondary metabolites to act as natural anticancer agents highlights their importance in both preventive and therapeutic strategies against cancer (

Figure 1). Their ability to target multiple pathways involved in cancer development makes them promising candidates for the development of new anticancer drugs and functional foods aimed at reducing cancer risk.

3.5. Role in Disease Prevention

Oxidative stress and inflammation are important contributors to the development and progression of many diseases. Although ROS production is an important mechanism for several cellular processes, their overproduction can occur in pathological disorders such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and neurological disorders, among others [

74]. In the same way, sustained or chronic inflammation can cause a plethora of diseases [

75]. In line with this, we review the potential impact of plant secondary metabolites in disease prevention.

3.5.1. Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death worldwide [

75]. In recent years, the prevention of CVD using natural compounds, especially those derived from plants, has gained attention [

75]. It has been shown that many plant-derived compounds, such as certain flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, and terpenoids, have cardioprotective effects through various mechanisms, including antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory effects, and modulation of lipid metabolism [

61,

76].

Flavonoids, especially those found in fruits, vegetables, and tea, have been associated with a reduced risk of CVDs. These compounds can improve endothelial function by enhancing nitric oxide production, which promotes vasodilation and reduces blood pressure. Additionally, flavonoids inhibit the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, a key step in the development of atherosclerosis. The anti-inflammatory properties of flavonoids also contribute to their cardioprotective effects by reducing inflammation in the vascular endothelium, a critical factor in the progression of this disease [

77,

78].

Certain phenylpropanoids, such as caffeic and ferulic acid, are also beneficial for cardiovascular health. These compounds exhibit antioxidant activity, protecting the cardiovascular system from oxidative stress and inflammation. Caffeic acid, found in coffee and certain fruits, has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation, reducing the risk of thrombosis, while ferulic acid, present in whole grains and seeds, can lower blood pressure by promoting nitric oxide production [

77,

78].

Terpenoids, particularly carotenoids, are another important group of compounds that contribute to cardiovascular health. Carotenoids such as lycopene, lutein, and β-carotene have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by lowering LDL cholesterol levels, improving lipid profiles, and reducing oxidative stress (Yao et al., 2021). Lycopene, found in tomatoes and other red fruits, is particularly effective in reducing blood pressure and improving endothelial function [

79].

The potential of plant secondary metabolites to promote cardiovascular health underscores their importance in functional foods and nutraceuticals. By incorporating these bioactive compounds into the diet, it may be possible to reduce the risk of CVDs and improve overall heart health.

3.5.2. Metabolic Diseases

Plant secondary metabolites hold significant promise as functional ingredients for metabolic regulation, particularly in diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Some polyphenols, such as resveratrol found in grapes and red wine, are known to activate sirtuins—proteins that regulate metabolic processes, including insulin sensitivity, fat storage, and glucose metabolism. Additionally, resveratrol can enhance mitochondrial function and increase energy expenditure, making it an attractive candidate for functional foods aimed at weight management and metabolic health [

80].

Anthocyanins, found in red berries, have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation in adipose tissue [

81,

82]. By modulating the activity of key enzymes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, these compounds can help regulate blood sugar levels and prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Another mechanism by which plant metabolites contribute to the prevention of metabolic diseases is by modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Recent clinical trials have shown that the intake of ellagic acid and curcuminoids increases the levels of antioxidant defenses while decreasing the levels of Malondialdehyde (MDA) in patients with T2DM [

83,

84] all of which contributes to better insulin sensitivity in these patients. Ellagic acid was also found to decrease inflammation markers in these patients. In the same way, compounds like hesperidin and genistein have also been reported to improve the oxidative status of patients with T2DM [

85,

86].

These studies evidence the potential of incorporating phenolic-rich foods into the diet to offer preventive and therapeutic benefits for individuals at risk of metabolic disorders.

3.5.3. Neuroprotection and Cognitive Health

Several studies have shown how plant-derived secondary metabolites can play a significant role in neuroprotection and cognitive health, areas of growing interest as the global population ages. Compounds such as flavonoids and terpenoids have been widely studied for their ability to protect neurons from oxidative stress, reduce neuroinflammation, and enhance cognitive function. For example, flavonoids like luteolin, found in celery and green peppers, have been shown to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain, making them an interesting alternative for reducing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's (Can & Sanlier, 2024).

Terpenoids, including those found in essential oils like rosemary and sage, have been associated with memory enhancement and improved cognitive function. These compounds can modulate neurotransmitter activity, enhance synaptic plasticity, and even promote the growth of new neurons through neurogenesis [

87] . Plant extracts, such as EGb 761

® from

Ginkgo biloba, have also shown good results in clinical trials in patients with Alzheimer´s disease (AD). This extract, which contains flavonol glycosides and terpene lactones, exerts a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities such as protection and restoration of mitochondrial function, reduction in the formation of p-tau and Aβ plaques, and antioxidant activity, all of which are relevant for AD [

88]).

The inclusion of these neuroprotective compounds in functional foods could support cognitive health and prevent the development of neurodegenerative disorders, especially in the aging population.

4. Applications of Plant Metabolites in Functional Foods

The incorporation of plant secondary metabolites into functional foods represents a growing area within food technology, driven by increasing consumer demand for products that not only provide basic nutrition but also offer additional health benefits. Functional foods, which are those enriched with bioactive compounds to provide specific advantages beyond their nutritional value, have gained significant attention due to the trend of consumers seeking alternatives to pharmaceuticals and aiming to prevent diseases. Plant metabolites offer a wide range of applications for the development of functional foods intended to improve human health.

4.1. Functional Foods Enriched with Bioactive Compounds

Flavonoids, carotenoids, and phenolic acids are commonly incorporated into functional foods to enhance their antioxidant properties. For example, the addition of anthocyanins from berries to beverages or dairy products not only improves their visual appeal with vibrant colors but also increases their health benefits by providing potent antioxidant protection [

89]. Carotenoids, such as beta-carotene and lycopene, are also widely used in functional foods for their antioxidant activity and their ability to improve skin health and vision. Functional foods fortified with carotenoids are often marketed for their potential to protect against UV-induced skin damage and support eye health, especially in products aimed at aging populations. These compounds can be incorporated into a variety of food matrices, including juices, snacks, and dairy products, offering consumers an easy and appealing way to increase their intake of these vital nutrients [

90,

91,

92].

Curcumin, a terpenoid found in turmeric, is widely recognized for its potent anti-inflammatory effects. It is often incorporated into functional beverages, dietary supplements, and even energy bars, providing consumers with a convenient way to manage inflammation. Additionally, functional foods enriched with flavonoids such as quercetin or luteolin are developed to help reduce inflammation and improve joint health, making them particularly popular among athletes and individuals with arthritis [

93].

Functional foods aimed at improving metabolic health and aiding weight management have long been an area of interest. In this case, the search for alternatives to pharmaceuticals is very attractive, making it a relevant research area for several scientists worldwide. Resveratrol, known for its ability to activate sirtuins and improve insulin sensitivity, is frequently added to functional beverages and supplements focused on metabolic syndrome and diabetes management [

80]. Similarly, foods rich in anthocyanins are promoted for their ability to improve glucose metabolism and reduce abdominal fat, making them attractive options for individuals looking to manage their weight [

80,

82,

91,

94]. These functional foods can range from fortified beverages to meal replacements, offering versatility in product development. It should be noted that these findings are suggested as support for weight control treatments.

As the global population ages, the interest in functional foods that support cognitive health and protect against neurodegenerative diseases is steadily growing. Flavonoids and terpenoids, with their neuroprotective properties, are ideal candidates for inclusion in these products. Functional foods designed to enhance memory, improve focus, and reduce the risk of cognitive decline often contain compounds such as EGCG from green tea, luteolin from vegetables, or rosemary extract, which have been shown to promote neuroprotection and support brain function [

95].

These neuroprotective compounds are incorporated into a variety of functional foods, including teas, smoothies, and snacks, providing consumers with an easy way to support cognitive health through their diet. The development of these products not only meets the needs of the aging population but also attracts younger consumers looking to enhance mental performance and prevent future cognitive decline.

4.2. Technological Applications of Plant Metabolites

4.2.1. Preservatives

Many natural products of plant origin are increasingly recognized for their potential as natural food preservatives, offering an alternative to synthetic additives that meet consumer demand for cleaner labels and safer food products. These natural compounds, which include phenolic compounds, terpenoids, and essential oils, possess a variety of antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antifungal properties that make them effective in extending the shelf life of food products while maintaining their safety and quality.

4.2.1.1. Antimicrobials

One of the primary mechanisms by which plant secondary metabolites act as food preservatives is through their antimicrobial activity. These compounds can inhibit the growth of bacteria, yeasts, and molds, which are common culprits of spoilage in a wide variety of foods.

Flavonoids, such as quercetin and kaempferol, found in fruits and vegetables, exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Their ability to disrupt microbial cell walls and membranes, interfere with enzyme activity, and inhibit nucleic acid synthesis makes them valuable for preserving a wide range of food products, from fresh produce to dairy and meat [

96,

97].

Some phenolic acids, such as gallic acid and ferulic acid, are another group of plant secondary metabolites with potent antimicrobial properties. These compounds are particularly effective against spoilage-causing bacteria and fungi, making them ideal for use in products such as baked goods, beverages, and sauces [

98]. Their mode of action includes disrupting microbial cell membranes, inhibiting enzyme activity critical for microbial growth, and inducing oxidative stress within microbial cells, ultimately leading to cell death.

4.2.2. Antifungals

The growth of molds and yeasts can significantly impact the shelf life and safety of food products, especially in baked goods, fruits, and dairy products. Plant-derived metabolites with antifungal properties offer a natural solution to this challenge. Terpenoids like thymol from thyme and carvacrol from oregano are well known for their ability to inhibit fungal growth. These compounds disrupt the fungal cell membrane, interfere with intracellular enzyme function, and inhibit spore germination, making them effective in preventing the spread of molds and yeasts in food products [

97,

99,

100].

Essential oils, rich in monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and other volatile compounds, are particularly valuable as natural antifungal agents. For example, cinnamon oil, which contains cinnamaldehyde, has been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of Aspergillus, Penicillium, and other common spoilage fungi (Hou et al., 2022; H. Wu et al., 2024). These essential oils can be incorporated into packaging materials, sprayed onto the surface of food products, or included directly in the food matrix to provide a protective barrier against fungal contamination.

4.2.3. Antioxidants and Enzyme Inhibition

Oxidation is one of the main causes of food spoilage, leading to rancidity in fats and oils, unpleasant flavors, and the degradation of nutritional quality. Many antioxidant metabolites of plant origin, such as flavonoids, carotenoids, and tocopherols (vitamin E), can neutralize free radicals and prevent oxidative damage, thus extending the shelf life of food products [

101,

102,

103]. For example, catechins from green tea are highly effective in preventing lipid oxidation in foods like meats, oils, and processed snacks. Similarly, beta-carotene and lycopene not only impart color to food products but also protect against oxidative degradation. These compounds are often used in conjunction with other natural antioxidants to produce positive synergistic effects, providing a more complex protective barrier against spoilage [

104].

Enzymatic browning is a common issue in fresh fruits and vegetables, where exposure to oxygen leads to the formation of brown pigments that can affect the appearance and taste of the product. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C), found in citrus fruits, is a well-known inhibitor of polyphenol oxidase (PPO), the enzyme responsible for browning reactions. By reducing the activity of this enzyme, ascorbic acid helps maintain the color and freshness of cut fruits and vegetables, thereby extending their shelf life. This is also useful for ingredients and processed food products that contain fruits in their formulations [

105].

Similarly, phenolic acids such as caffeic acid and ferulic acid, can also inhibit enzymatic browning by acting as competitive inhibitors of PPO. These compounds are effective in maintaining the visual and sensory qualities of fresh produce, making them valuable for use in pre-packaged salads, fresh-cut fruits, and other minimally processed foods [

106].

4.2.4. Modulation of Sensorial Properties

Plant secondary metabolites are not only valuable for their health benefits and preservative qualities but also play a crucial role as enhancers or modulators of sensorial properties in food products. These compounds contribute to the development of flavors, aromas, colors, and textures that are essential for creating appealing and enjoyable food experiences. The ability to naturally enhance or modify these sensorial properties makes plant secondary metabolites indispensable in the food industry, particularly in the development of products that meet consumer demands for natural and flavorful foods.

4.2.4.1. Flavor and Aroma

One of the most significant applications of plant secondary metabolites is in the development and modulation of flavors and aromas. Terpenoids and phenolic compounds are among the key contributors to the complex flavor profiles of many foods and beverages. Limonene in citrus fruits, menthol in mint, and thymol in thyme, are highly aromatic compounds that define the characteristic flavors and aromas of various herbs, spices, and fruits. These compounds can be used to enhance the natural flavors of food products or to develop new flavor profiles. For example, terpenoids present in essential oils are often used in the formulation of flavorings for beverages, confectionery, and savory products, providing both freshness and depth to the overall taste [

107,

108].

Similarly, flavonoids contribute to the bitter, astringent, and sometimes sweet notes in foods and beverages. Catechins in tea and chocolate, for example, impart astringency, while flavanones in citrus fruits contribute to their bitterness [

109,

110]. The modulation of these flavor profiles through the careful blending of flavonoid-rich ingredients allows food scientists to achieve the desired balance of taste and mouthfeel in products ranging from teas and juices to complex culinary sauces.

Phenolic acids, such as cinnamic acid and vanillic acid, are also important in flavor development. These compounds are responsible for the warm, spicy notes found in cinnamon and vanilla, respectively. In addition to being used as flavoring agents, phenolic acids can influence the perception of other flavors, enhancing the overall taste experience. The interaction of phenolic compounds with taste receptors and other flavor molecules can intensify certain notes, such as sweetness or umami, or mellow harsh or bitter flavors, leading to a more balanced and harmonious flavor profile [

81].

Alkaloids, which often contribute to bitterness, can be modulated to achieve the desired flavor balance in products such as coffee, chocolate, and tonic water. The bitterness of caffeine in coffee, for example, can be balanced with other flavored compounds to create a smoother and more pleasant beverage. Similarly, the bitterness of certain plant-based products can be reduced or masked by blending them with sweet or umami-rich ingredients, creating a more balanced flavor profile [

109,

111].

Astringency, commonly associated with tannins, can also be modulated to enhance the sensory appeal of foods and beverages. Techniques such as aging, fermentation, and the addition of other polyphenols can be used to reduce astringency or to create the desired balance in products such as wine, tea, and chocolate [

112,

113]. By carefully controlling the levels of tannins and other astringent compounds, food scientists can develop products with the right balance of complexity, mouthfeel, and flavor. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the role of these metabolites in food products and to have a panel of experts to generate the balance between sensory experience and biological activity (or functionality), as the sensory experience remains the most relevant driver of consumption, more so than the awareness of functional benefits.

4.2.4.2. Color Enhancement

The vibrant and attractive colors of fruits, vegetables, and other plant-based foods are often due to the presence of secondary metabolites such as carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains. These compounds not only contribute to the visual appeal of food products but also influence consumer perception of flavor and freshness [

114].

Carotenoids, such as β-carotene, lycopene, and lutein are commonly used in the food industry as natural colorants, replacing synthetic dyes in products ranging from beverages and dairy to snacks and confectionery. In addition to their coloring properties, carotenoids can also influence the sensory perception of foods, as the vibrant colors they provide are often associated with fresh and nutrient-rich products [

115].

Anthocyanins, with their deep red, purple, and blue colors, are another group of secondary metabolites widely used as natural colorants. These pigments are particularly valued for their pH-sensitive color properties, which can range from red to purple to blue, depending on the acidity of the food matrix. This versatility makes anthocyanins ideal for use in a variety of food products, including beverages, desserts, and condiments, where they not only enhance visual appeal but also influence the perception of freshness and flavor intensity [

82,

114].

4.2.4.3. Texture and Mouthfeel Modification

Beyond flavor and color, plant-derived natural products can also play an important role in modifying and adjusting the texture and mouthfeel of food products. Saponins, tannins, and certain polysaccharides derived from plants are examples of compounds that can influence the sensory experience of texture.

Saponins, found in legumes, quinoa, quillay bark, and some herbs, have the characteristic of forming stable foams and emulsions, making them useful in developing creamy and frothy textures in beverages and dairy alternatives, for example, in barista applications and fantasy sodas to create an attractive foam for consumers. In addition to their functional properties, saponins can impart a slightly bitter or astringent taste, which can be desirable in certain culinary applications, such as in the formulation of bitter herbal beverages or complex flavor profiles in gourmet foods [

116,

117,

118,

119].

Tannins are known for their astringent properties that contribute to the drying sensation in the mouth. This astringency is often balanced with other flavors to create a desirable mouthfeel in products like wine, where tannins contribute to the overall complexity and structure and are related to its quality [

112,

113,

120]. In food technology, tannins can be used to modulate the mouthfeel of products, enhancing the sensation of body or richness in beverages, sauces, and confectioneries.

5. Optimizing Bioactive Compounds: Stability, Bioavailability and Absorption

5.1. Stability of Bioactive Compounds During Food Processing and Storage

The stability of plant secondary metabolites is a critical factor in ensuring their efficacy and safety in functional foods and other food products. Stability refers to the ability of these compounds to maintain their chemical structure, potency, and biological activity over time, especially during processing, storage, and consumption. The instability and high reactivity of certain plant-derived compounds pose significant challenges in food technology, as they can lead to the loss of desired health benefits, alterations in sensory properties, and even the formation of undesirable or harmful by-products.

Many of these metabolites are sensitive to factors such as temperature, light, and oxygen exposure, which can trigger their degradation and decrease their effectiveness. For example, flavonoids and carotenoids, known for their antioxidant properties, may lose their activity when exposed to high temperatures during processes like pasteurization or cooking. Similarly, phenolic acids with potent antioxidant activity can easily oxidize, leading to the production of catechols, thereby reducing their antioxidant capacity and negatively affecting the final product's stability, altering certain attributes like color and flavor [

121].

Furthermore, the stability of secondary metabolites not only influences the retention of their beneficial properties but also impacts the consumer's sensory experience. The degradation of these compounds can alter the taste, color, and texture of foods, making the final product less appealing or even unacceptable from an organoleptic standpoint. Therefore, food scientists must develop strategies to enhance the stability of these compounds throughout the product's shelf life, ensuring that the stability of functional ingredients does not become a deviation parameter for the product. Importantly, the shelf life of a product is directly related to its cost and, therefore, to its accessibility for consumers.

Among the strategies being explored to improve the stability of secondary metabolites are the use of encapsulation technologies, the incorporation of protective molecules (stabilizers and/or preservatives), and the modification of the storage environment, such as reducing oxygen and light exposure through packaging technologies. Continuous research in this field is essential to optimize the use of these compounds in the food industry and ensure that consumers can enjoy their health benefits without compromising the quality of the product [

68].

5.2. Bioavailability and Absorption

The bioavailability of plant secondary metabolites—referring to the extent and rate at which these compounds are absorbed into the bloodstream and become available for biological activity in target tissues or cells—is one of the most significant challenges in harnessing their full potential in functional foods and therapeutic applications. Despite the well-documented health benefits of flavonoids, terpenoids, and other secondary metabolites, their effectiveness can be limited by factors affecting their solubility, stability, absorption, metabolism, and overall bioavailability.

Many secondary metabolites exhibit poor water solubility, which directly affects their absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Flavonoids, for example, are often present in foods as glycosides, which have limited solubility in the aqueous environment of the intestine. This low solubility results in limited absorption into the bloodstream, thereby reducing their bioavailability. Terpenoids, due to their lipophilic nature, face similar challenges as they require adequate fat intake for optimal absorption, which can vary depending on the diet [

122].

Once ingested, plant secondary metabolites undergo an extensive process of metabolism in the liver and intestines, known as the first-pass effect, which determines the chemical structure that will finally reach the targets. This metabolism can transform the compounds into various metabolites, some of which may be less active or even completely inactive. For example, certain flavonoids are metabolized by gut microbiota and liver enzymes into metabolites with reduced biological activity, which can decrease their effectiveness. Understanding and managing the metabolic pathways of these compounds is crucial for optimizing their bioavailability and therapeutic potential [

123].

Another challenge is the rapid elimination of secondary metabolites that are incorporated into the body through the oral route. Many of these compounds are quickly excreted through urine or bile, which limits their half-life in the bloodstream. For example, catechins from green tea are rapidly metabolized and excreted, resulting in a short half-life and reduced bioavailability, highlighting the importance of the dose-activity balance. This rapid elimination necessitates frequent consumption of the active compounds, which may not always be practical or desirable for consumers [

124].

5.3. Emerging Technologies for Enhancing the Efficacy of Bioactive Compounds

To overcome the challenges of bioavailability, the development of advanced delivery systems is a key area of research. Encapsulation-based delivery systems, such as micro and nano emulsions, liposomes, and solid lipid nanoparticles, offer promising solutions for improving the solubility, stability, and absorption of secondary metabolites by consumers. These systems can protect bioactive compounds from degradation during processing and storage, enhance their absorption in the intestine, and prolong their circulation time in the bloodstream, thus improving overall bioavailability. This also reduces the effective doses and ensures that the desired effects are observed by consumers [

125,

126].

Encapsulation is a widely used strategy to enhance the stability of unstable or sensitive natural products that will be applied in food products. This process involves incorporating bioactive compounds into a protective matrix, such as liposomes, nano emulsions, or microcapsules, which shield them from environmental factors and prevent degradation during processing and storage. This technique allows these compounds to function as a thermodynamic system within another system, providing a favorable environment to preserve the attributes of sensitive molecules. For example, encapsulating carotenoids in lipid-based nano emulsions has proven effective in protecting them from oxidation and improving their stability in food products such as beverages and dairy. Similarly, the microencapsulation of essential oils can preserve their volatile compounds and extend the shelf life of flavored products [

125,

126,

127,

128].

Another future direction involves modifying the structure of plant secondary metabolites to enhance their metabolic stability. This can be achieved through chemical modifications, such as esterification or glycosylation, to protect the compounds from rapid metabolism and excretion. Several alternatives exist to maintain their natural status, including enzymatic modifications and fermentation processes using GRAS microorganisms, which can include molds, yeasts, and/or bacteria.

The addition of stabilizing and preservative agents, such as antioxidants, emulsifiers, and chelating agents, can help protect bioactive compounds from degradation. Antioxidants like ascorbic acid and tocopherols can neutralize free radicals and prevent the oxidation of sensitive compounds like flavonoids and carotenoids. Emulsifiers, such as lecithin, can improve the solubility and dispersion of lipophilic compounds in aqueous environments, enhancing their stability in food matrices. Chelating agents like EDTA can bind to metal ions that catalyze oxidation reactions, such as the Fenton reaction, reducing the risk of oxidative degradation of susceptible compounds like various phenolic compounds.

The incorporation of bioactive compounds into food matrices that enhance their bioavailability represents another promising direction in the development of functional foods. For example, by combining fat-soluble carotenoids with healthy fats in food products, their absorption in the body can be significantly improved. This approach not only maximizes the nutritional benefits of carotenoids but also ensures that consumers receive an adequate amount of these essential compounds for visual health and overall well-being.

Similarly, the formulation of beverages or supplements that contain both prebiotics and polyphenols can generate positive synergistic effects that enhance bioavailability and activity. Prebiotics, by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut, not only support digestive health but can also facilitate the metabolism and absorption of polyphenols, thereby increasing their efficacy. Moreover, the design of foods that integrate sources of soluble fiber along with bioactive compounds could offer dual functionality: on one side, contributing to gastrointestinal health, and on the other, enhancing the availability and positive impact of antioxidants present in the diet.

From the food processing perspective, there are several strategies that can be used to minimize the degradation of bioactive compounds. This may involve reducing temperatures, shortening processing times, or modifying processing methods to be gentler to protect the integrity of active molecules. For example, cold-pressing techniques for extracting vegetable oils help preserve the stability of heat-sensitive compounds, such as essential fatty acids and volatile terpenoids. Some of these oils retain their natural antioxidants, eliminating the need for synthetic antioxidants and harnessing the potential of the raw material itself. Similarly, using non-thermal processing methods, such as high-pressure processing or pulsed electric fields, can help maintain the bioactivity of secondary metabolites while ensuring food safety [

10,

129,

130,

131].

These strategies, when applied together, offer a comprehensive approach to maximizing the stability and effectiveness of secondary metabolites in food products. They not only ensure that health benefits are maintained throughout the product's shelf life but also contribute to preserving the sensory and nutritional properties vital to commercial success and consumer satisfaction.

6. Regulatory Considerations, Labeling Requirements, and Consumer Acceptance

The use of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals in food products, especially within the scope of functional foods and natural preservatives, involves a range of regulatory and safety considerations that differ across various regions worldwide. These regulations are designed to ensure that these compounds are safe for consumer use and that products are labeled and marketed accurately. Although the underlying goals of these regulatory frameworks are similar, the specific requirements and guidelines can vary significantly from one region to another. The same happens with consumer acceptance, a key factor in determining the success of food products that incorporate plant secondary metabolites and botanicals, especially within the expanding market for functional foods and natural products.

6.1. North America

In North America, the regulation of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals in food products is primarily managed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States and Health Canada in Canada. In the U.S., new plant-derived compounds, including botanicals, must either be approved as food additives or be recognized as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) to be used in food products. For botanicals and secondary metabolites that do not have GRAS status, manufacturers are required to submit a food additive petition to the FDA. This petition must include evidence of safety, such as toxicological data, to demonstrate that the ingredient is safe for consumption. In Canada, the regulation of botanicals and plant secondary metabolites falls under the Food and Drugs Act. Similar to the U.S., these compounds must be approved as food additives or categorized as natural health products (NHPs) if they are used in supplements. Health Canada mandates a comprehensive safety assessment, which includes toxicological data, before approving any new ingredients. Both the U.S. and Canada place a strong emphasis on accurate labeling and transparency, ensuring that the source and function of these compounds in food products are clearly communicated to consumers.

In both countries consumer acceptance of food products containing plant secondary metabolites and botanicals is robust and continues to expand. This growing trend is fueled by a strong demand for natural and clean-label products, alongside increasing awareness of the health benefits associated with these compounds. Consumers in this region are progressively seeking foods that provide functional benefits, such as enhanced nutrition, improved digestion, and overall well-being support. But these products must be supported by solid scientific evidence, and there is noticeable skepticism towards exaggerated health claims. This highlights the crucial need for accurate labeling and well-substantiated claims to maintain and build consumer confidence.

6.2. Latin America

In Latin America, the regulation of plant secondary metabolites and botanical compounds varies by country, but there is a general trend toward aligning regulations with international standards. In Chile, the Ministry of Health oversees food safety and regulation through the Food Sanitary Regulations (Reglamento Sanitario de los Alimentos, RSA). Botanical and plant-derived compounds intended for use in food products must be approved by the Ministry, and their safety must be supported by scientific evidence. Chile follows an approach similar to the U.S. GRAS system, where certain traditional ingredients are accepted based on a history of safe use. In other Latin American countries, regulations are generally aligned with Codex Alimentarius standards, although enforcement and specific requirements may vary. For instance, Brazil and Argentina have established regulations for dietary supplements and functional foods that require pre-market approval and safety assessments for new botanicals or secondary metabolites.

In a similar manner, consumer acceptance of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals varies across different countries but tends to be generally favorable, especially in key markets like Chile, Brazil, and Mexico. In Chile, there is a strong cultural tradition of using natural remedies and botanicals, which has contributed to a positive attitude toward functional foods and products containing these plant-derived compounds. As awareness of the health benefits associated with these compounds grows, the market for products incorporating traditional ingredients such as maqui berry, yerba mate, and aloe vera is expanding.

6.3. Europe

In Europe, the regulation of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals in food products is overseen by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Depending on their intended use, botanicals and secondary metabolites must be approved either as food additives or as novel foods. The Novel Foods Regulation applies to ingredients that were not commonly consumed in the EU before May 1997, requiring a comprehensive safety assessment, including toxicological studies, to prove that the novel food is safe. The EU also has strict rules regarding health claims on functional foods. Under the Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation (NHCR), any health-related claim must be supported by scientific evidence and receive approval from the European Commission, based on EFSA’s evaluation. This ensures that consumers are not misled by unsubstantiated claims about the health benefits of botanicals or plant secondary metabolites.

Europe is one of the most advanced markets for functional foods and products containing plant secondary metabolites and botanicals. Consumer acceptance in this region is fueled by a strong focus on health and wellness, as well as a preference for natural and organic products. European consumers are particularly attentive to the safety and effectiveness of the products they choose, often favoring those backed by scientific research and approved by regulatory bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

Botanicals such as echinacea, elderberry, and milk thistle are widely embraced in Europe, with a growing market for products that incorporate these ingredients due to their perceived health benefits. The EU’s rigorous regulations on health claims have further bolstered consumer confidence in the functional food sector, as consumers can trust that the claims on product labels are substantiated by solid evidence. Additionally, there is a deep cultural appreciation for traditional herbal remedies, especially in countries like Germany and Austria, which further supports the acceptance and popularity of botanicals in food products across the continent.

6.4. Asia

In Asia, regulatory approaches vary significantly across different countries. In Japan, the Food for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) system permits certain functional foods containing botanicals and plant secondary metabolites to be marketed with health claims, provided they receive approval from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. In China, the regulation of botanicals and food additives is managed by the National Health Commission (NHC) and the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR). Plant secondary metabolites used in functional foods or as food additives must undergo approval processes, and their safety must be demonstrated through toxicological studies. While Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) ingredients are commonly used in food products and generally accepted due to their long history of use, new applications or specific health claims may be subject to additional scrutiny.

In Asia, consumer acceptance of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals is deeply intertwined with the region's rich traditions of herbal medicine and natural health practices. Countries like Japan, China, India, and South Korea have long histories of using botanicals for health and wellness, leading to a high level of acceptance for functional foods that incorporate these ingredients.

In Japan, the Food for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) system has cultivated a market where consumers readily embrace functional foods containing ingredients like green tea catechins, soy isoflavones, and turmeric. Japanese consumers are particularly health-conscious, often seeking out foods that offer targeted health benefits, such as lowering cholesterol or enhancing digestive health.

In China and India, traditional medicine systems like Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda significantly influence consumer preferences. There is widespread acceptance of botanicals such as ginseng, goji berries, and ashwagandha, which are commonly included in both food products and supplements. While trust in these traditional ingredients remains strong, there is also an increasing demand for products that are backed by scientific validation and adhere to modern safety standards. This trend reflects a growing intersection between traditional practices and contemporary health and wellness expectations across the region.

6.5. Australia and New Zealand

In Australia and New Zealand, the regulation of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals is managed by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). These countries adopt a regulatory approach similar to that of the European Union, where any new plant-derived ingredient intended for use in food must undergo a rigorous safety assessment and approval process. The Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code specifies the requirements for food additives, novel foods, and health claims, ensuring that all products meet the necessary safety and quality standards.

Functional foods and supplements containing botanicals and plant secondary metabolites are subject to strict labeling regulations, and any health claims made must be substantiated by scientific evidence. The primary focus is on protecting consumers from misleading claims and ensuring that all food products are safe for consumption. FSANZ also closely monitors the use of traditional ingredients, requiring that any new applications or formulations undergo a thorough evaluation to ensure they meet safety standards.

Consumer acceptance of plant secondary metabolites and botanicals in Australia and New Zealand is marked by a strong inclination towards natural and organic products. The functional food market in these countries is well-established, with consumers increasingly favoring products that promote overall health and well-being. There is a notable interest in ingredients that are sustainably sourced and perceived as clean and natural.

Botanicals like manuka honey, eucalyptus, and kakadu plum are particularly popular in Australia and New Zealand, where they are cherished not only for their health benefits but also for their connection to the local environment. Consumers in this region are generally well-informed about the health benefits of functional foods and place a high degree of trust in products that are supported by scientific research and have received regulatory approval from Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

7. Conclusions

The exploration and utilization of plant secondary metabolites in functional foods represents a promising frontier in food science and technology. Compounds like flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic acids, glucosinolates, alkaloids, and glycosides offer a diverse range of health benefits, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, cardiovascular support, and cancer prevention. Their varied bioactivities not only enhance the nutritional profile of foods but also offer significant therapeutic potential for chronic disease prevention and overall well-being.

However, incorporating plant secondary metabolites into food products comes with its challenges, particularly regarding bioavailability, stability, and regulatory compliance. Overcoming these challenges requires innovative approaches such as advanced delivery systems, structural modifications, and leveraging prebiotics and probiotics to boost absorption and efficacy. Moreover, regulatory and safety considerations are crucial in ensuring that functional foods containing plant secondary metabolites meet the necessary standards and are safe for consumption. The varied regulatory frameworks across different regions underscore the importance of complying with local regulations and providing scientifically substantiated health claims.

In conclusion, the future of functional foods lies in successfully integrating plant secondary metabolites and harnessing their full potential to promote health and well-being. Continued research and innovation in bioavailability, stability, and regulatory compliance, along with a focus on consumer education and acceptance, will be crucial in realizing the benefits of these powerful compounds in the food industry. As the demand for functional and natural foods continues to rise, plant secondary metabolites will play an increasingly important role in shaping the future of food and nutrition.

Author Contributions

Rodrigo A. Contreras (RAC): Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Data Curation, and Figure/Table Preparation. Marisol Pizarro (MP): Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, and Data Curation. Ana Batista-González (AB-G): Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, and Data Curation.

Funding

Privately funded by The Not Company (Chile, and the US).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the members of The NotCo R&D department for their support and for providing essential insights into consumer needs and industry requirements, which helped guide this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The Link between the Consumer and the Innovations in Food Product Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiocchio, I.; Mandrone, M.; Tomasi, P.; Marincich, L.; Poli, F. Plant Secondary Metabolites: An Opportunity for Circular Economy. Molecules 2021, 26, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, A.; Novellino, E. Nutraceuticals - shedding light on the grey area between pharmaceuticals and food. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2018, 11, 545–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götz, K.; Courtier, A.; Stein, M.; Strelau, L.; Sunderer, G.; Vidaurre, R.; Winker, M.; Roig, B. Risk Perception of Pharmaceutical Residues in the Aquatic Environment and Precautionary Measures. Management of Emerging Public Health Issues and Risks; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 189–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, S.; Braunbeck, T. Transition towards sustainable pharmacy? The influence of public debates on policy responses to pharmaceutical contaminants in water. Environ Sci Eur 2020, 32, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M.M.; Bishir, M.; Bhat, A.; Chidambaram, S.B.; Al-Balushi, B.; Hamdan, H.; Govindarajan, N.; Freidland, R.P.; Qoronfleh, M.W. Functional foods and their impact on health. J Food Sci Technol 2023, 60, 820–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Go, A.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Cushman, M.; de Ferranti, S.; Després, J.-P.; Fullerton, H.J.; Howard, V.J.; Huffman, M.D.; Judd, S.E.; Kissela, B.M.; Lackland, D.T.; Lichtman, J.H.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Liu, S.; Mackey, R.H.; Matchar, D.B.; McGuire, D.K.; Mohler, E.R.; Moy, C.S.; Muntner, P.; Mussolino, M.E.; Nasir, K.; Neumar, R.W.; Nichol, G.; Palaniappan, L.; Pandey, D.K.; Reeves, M.J.; Rodriguez, C.J.; Sorlie, P.D.; Stein, J.; Towfighi, A.; Turan, T.N.; Virani, S.S.; Willey, J.Z.; Woo, D.; Yeh, R.W.; Turner, M.B. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2015 Update. Circulation 2015, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.-T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; Graham, I.; Hall, M.S.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Løchen, M.-L.; Löllgen, H.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Perk, J.; Prescott, E.; Redon, J.; Richter, D.J.; Sattar, N.; Smulders, Y.; Tiberi, M.; van der Worp, H.B.; van Dis, I.; Verschuren, W.M.M. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 2315–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmet, P.Z.; Magliano, D.J.; Herman, W.H.; Shaw, J.E. Diabetes: a 21st century challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014, 2, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfaoui, L. Dietary Plant Polyphenols: Effects of Food Processing on Their Content and Bioavailability. Molecules 2021, 26, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.B.; Nikmaram, N.; Esteghlal, S.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Niakousari, M.; Barba, F.J.; Roohinejad, S.; Koubaa, M. Efficiency of Ohmic assisted hydrodistillation for the extraction of essential oil from oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. viride) spices. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2017, 41, 172–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, F.; Restani, P.; Biella, S.; Di Lorenzo, C. Botanicals in Functional Foods and Food Supplements: Tradition, Efficacy and Regulatory Aspects. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2387. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lee, S.-L.; Taylor, C.; Li, J.; Chan, Y.-M.; Agarwal, R.; Temple, R.; Throckmorton, D.; Tyner, K. Scientific and Regulatory Approach to Botanical Drug Development: A U. S. FDA Perspective. J Nat Prod 2020, 83, 552–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E.; Plunkett, M.D. Genetically Modified Foods: Consumer Issues and the Role of Information Asymmetry. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne d’agroeconomie 1999, 47, 445–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects – A review. J Funct Foods 2015, 18, 820–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason Sonochem 2017, 34, 540–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Potential Health Benefits of Plant Food-Derived Bioactive Components: An Overview. Foods 2021, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, P.; Nitin, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, A.; Chhikara, N. Food Function and Health Benefits of Functional Foods. Functional Foods; Wiley, 2022; pp. 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]