Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To study the present analytics of international divorce, legal framework, jurisdictional disputes, and difficulties faced by a person pursuing a divorce from another country.

- How cross-border spouses and their families adjust to their new societies.

- By addressing topics like discrimination, inequality, and human rights violations that may occur in the context of cross-border marriages and divorce.

2. Overview

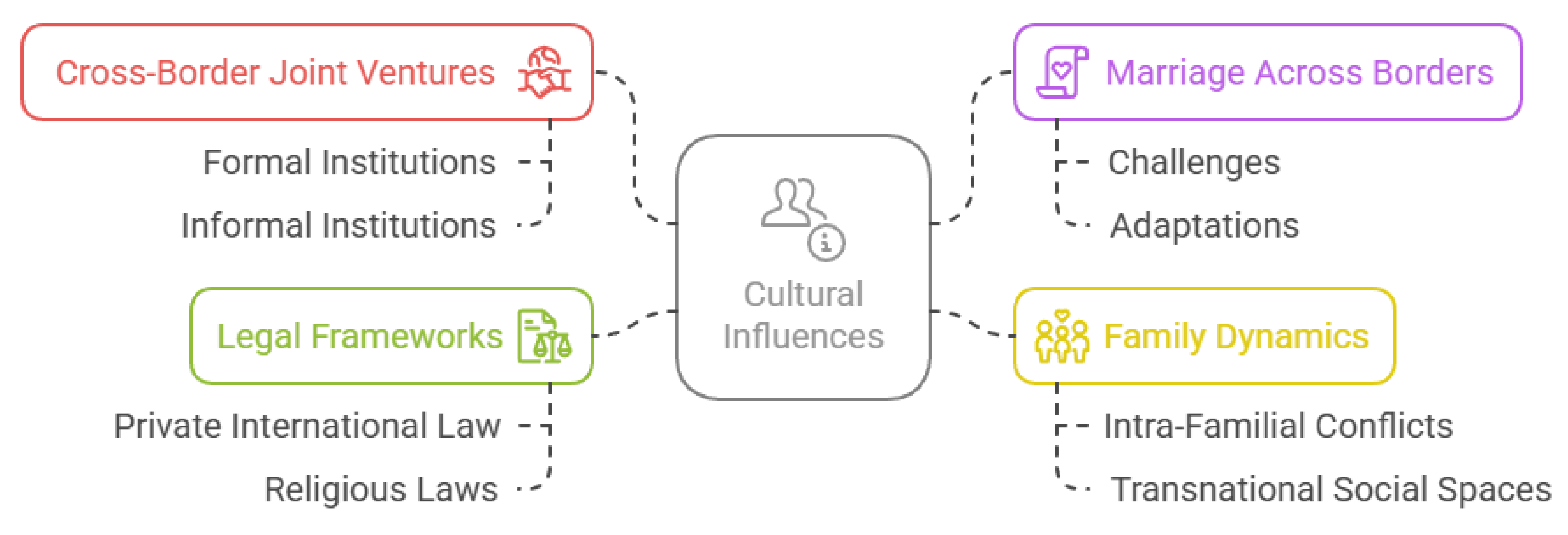

3. Impact of Cultural and Religious Differences on Marriage and Divorce

4. Legal Rights and Obligations of Spouses in Different Jurisdictions

5. Anatomy of Post-Divorce Finance Settlements

6. Financial Settlement

7. Considerations to Prove When Effectively giving Alimony, Support, or Financial Maintenance

| Section | Key Provisions | Key Terms | Considerations |

| 19 | - Court may award maintenance pending suit or financial provision to either spouse. | - Maintenance pending suit- Financial provision | - Must be "just and equitable"- Court must consider standard of living and circumstances of the parties. |

| 20 | - Court may order payment of money or conveyance of property (movable/immovable) to settle property rights or as financial provision. | - Settlement of property rights- Financial provision- "In gross" or "by instalments" | - Must be "just and equitable"- Payments/conveyances can be made in full (gross) or spread over time (instalments). |

- The income, earning capacity which encompass the capacity of both spouses to earn an income.

- The duration of the marriage.

- Property and other resources which each of the parties have or is likely to have in the reasonably foreseeable future.

- The financial needs, obligations and expenses which each of the parties has or is likely to have in the reasonably foreseeable future.

- The pre-breakdown standard of living maintained by the family

- The ages of the parties and the length of the marriage.

- Forgoing the spouse's career.

- Performance of domestic work and bearing a spouse's child

8. Alternative Dispute Resolution in Cross-Border Divorce Cases

| Term | Key Features | Benefits/Considerations |

| Mediation | Neutral mediator facilitates communication; voluntary settlement focus. | Collaborative, avoids court battles; requires good faith, legal review advised. |

| International Arbitration | Binding decision by private arbitrator; follows procedural rules/treaties. | Faster than cross-border litigation; enforceable outcomes, but parties lose control. |

| Collaborative Law | Lawyers negotiate cooperatively; withdrawal if talks fail. | Empowers mutual solutions, adaptable to cross-border issues; incentivizes compromise. |

8.1. Constructing a Strong Cross-Border Legal Team

8.1.1. Selecting the Best International Divorce Lawyers

8.1.2. Adding Financial and Tax Accountants

8.1.3. Other Necessary Experts and Services

9. Conclusions

References

- Gough, E. K. (1959). The Nayars and the definition of marriage. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 89(1), 23-34.

- Emery, R. E. (2013). Cultural sociology of divorce: An encyclopedia (Vol. 1). Sage.

- Constable, N. (Ed.). (2010). Cross-border marriages: Gender and mobility in transnational Asia. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Barkat, A., Anjum, R., & Jatoi, A. A. (2025). Cross Border Issues in International Divorce: A Legal Understanding. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 6(1), 518-528. [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. (2013). 2 Transnational Marriage Migration and Marriage Migration: An Overview. Transnational marriage, 23-37.

- Md Said, M. H. B., & Emmanuel Kaka, G. (2023). Domestic violence in cross-border marriages: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1483-1502. [CrossRef]

- SS, S., & Begum, S. F. (2024). Controlling Body and Sexuality: Cross Border Marriages Among Muslim Women in Kerala. Library of Progress-Library Science, Information Technology & Computer, 44(3).

- Charsley, K. (2013). 1 Transnational Marriage. In Transnational marriage (pp. 3-22). Routledge.

- Choi, S. Y., & Cheung, A. K. L. (2017). Dissimilar and disadvantaged: Age discrepancy, financial stress, and marital conflict in cross-border marriages. Journal of Family Issues, 38(18), 2521-2544. [CrossRef]

- Moret, J., Dahinden, J., & Andrikopoulos, A. (2023). Introduction: Contesting categories of cross-border marriages: perspectives of the state, spouses and researchers. In Cross-Border Marriages (pp. 1-18). Routledge.

- Constable, N. (Ed.). (2010). Cross-border marriages: Gender and mobility in transnational Asia. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Fresnoza-Flot, A., & De Hart, B. (2022). Divorce in transnational families: Norms, networks, and intersecting categories. Population, Space and Place, 28(5), e2582.

- Estin, A. L. (2016). Marriage and divorce conflicts in international perspective. Duke J. Comp. & Int’l L., 27, 485.

- Ahn, S. Y. (2025). Matching across markets: An economic analysis of cross-border marriage. Journal of Labor Economics, 43(2), 000-000. [CrossRef]

- Williams, L. (2013). 2 Transnational Marriage Migration and Marriage Migration: An Overview. Transnational marriage, 23-37.

- Le Bail, H. (2023). Promoting and restricting marriage migrations: when marriages are not such a private matter. In Research Handbook on the Institutions of Global Migration Governance (pp. 327-340). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ibrahim, F. (2018). Cross-border intimacies: Marriage, migration, and citizenship in western India. Modern Asian Studies, 52(5), 1664-1691. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri, K. S., Joyner, K., & Kao, G. (2017). Trading youth for citizenship? The spousal age gap in cross-border marriages. Population and Development Review, 43(3), 443. [CrossRef]

- Steyn, H. K. (2015). Cross-cultural divorce mediation by social workers: Experiences of mediators and clients (Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban).

- Georgieva, D., Jandik, T., & Lee, W. Y. (2012). The impact of laws, regulations, and culture on cross-border joint ventures. Journal of international financial markets, institutions and money, 22(4), 774-795. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan Ullah, A. K. M., & Chattoraj, D. (2023). International marriage migration: The predicament of culture and its negotiations. International Migration, 61(6), 262-278. [CrossRef]

- Sandel, T. L. (2011). Is it Just Cultural? Exploring (Mis) perceptions of Individual And Cultural Differences of Immigrants through Marriage in Contemporary Taiwan. China Media Research, 7(3).

- Kalmijn, M. (2010). Country differences in the effects of divorce on well-being: The role of norms, support, and selectivity. European Sociological Review, 26(4), 475-490. [CrossRef]

- Jänterä-Jareborg, M. (2016). Cross-border family cases and religious diversity: what can judges do?. In Family, Religion and Law (pp. 143-163). Routledge.

- Witte Jr, J., & Nichols, J. A. (2012). Who governs the family? Marriage as a new test case of overlapping jurisdictions. Faulkner L. Rev., 4, 321.

- Terradas, B. A. (2018). Jurisdiction clauses in international premarital agreements: A comparison between the US and the European system. European Review of Private Law, 26(4). [CrossRef]

- Crain, J. O. A. N. (2017). Cross-Border Divorces: Where Breaking Up Is Harder to Do. Am. J. Fam. L., 31, 20.

- Matrimonial Causes Act, 1971 (Act 367), s 1(2),.

- Samuel Babilogozo Ofori V. Danielle Tashima Pinkney, (2016) JELR 107759 (HC).

- Black’s Law Dictionary, (8th ed. 2004) page 228.

- ‘Maintenance: A Short Ride on the Alimony Pony’ (Cambridge Family Law Practice, July 25 2012) http://cflp.co.uk/maintenance-alimony-pony/.

- RIBEIRO v. RIBEIRO (1989-90) GLR 109 at 115-116.

- Addey, M. (2023). The Anatomy of Financial Settlements After a Divorce (Alimony): Understanding the Court's Evaluation of Crucial Factors. Available at SSRN 4527322.

- Obeng v. Obeng (2013), 63 Ghana Monthly Judgements, 158.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).