Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Establishment of Stable Transfectants

2.3. Development of Hybridomas

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant Values Using Flow Cytometry

2.6. Immunoblotting

2.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) USING CELL BLOCKS

3. Results

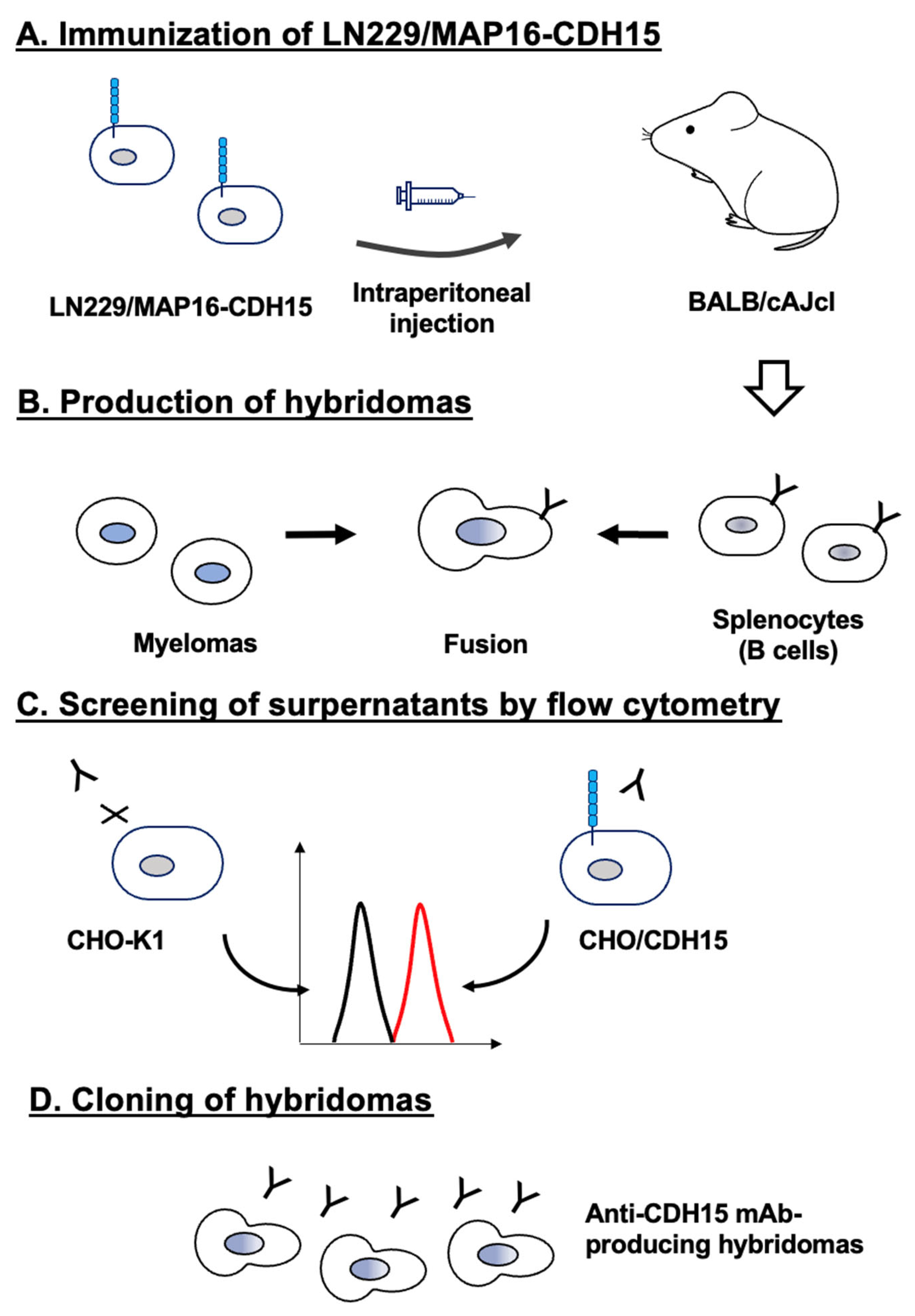

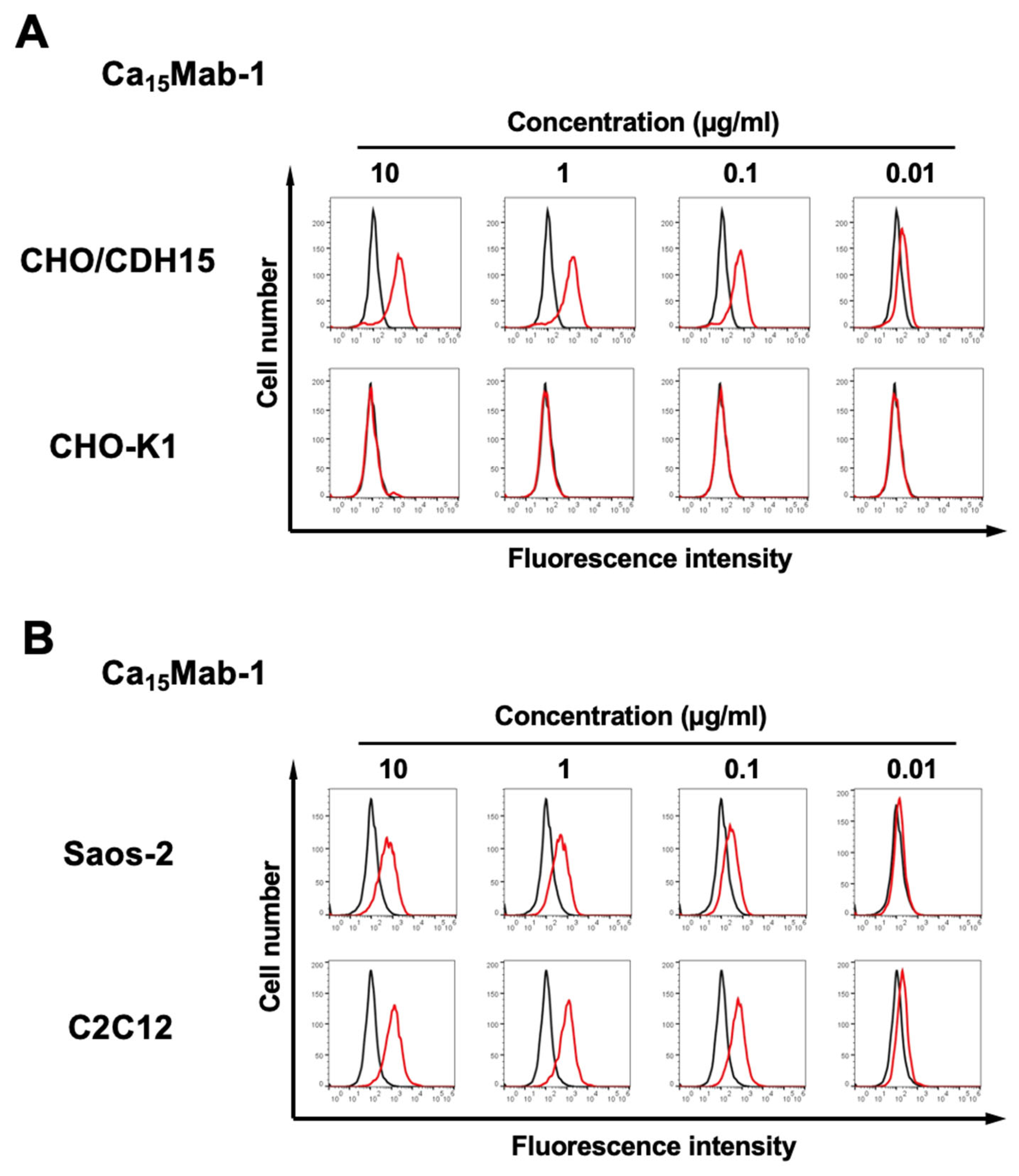

3.1. Development of Anti-CDH15 mAbs

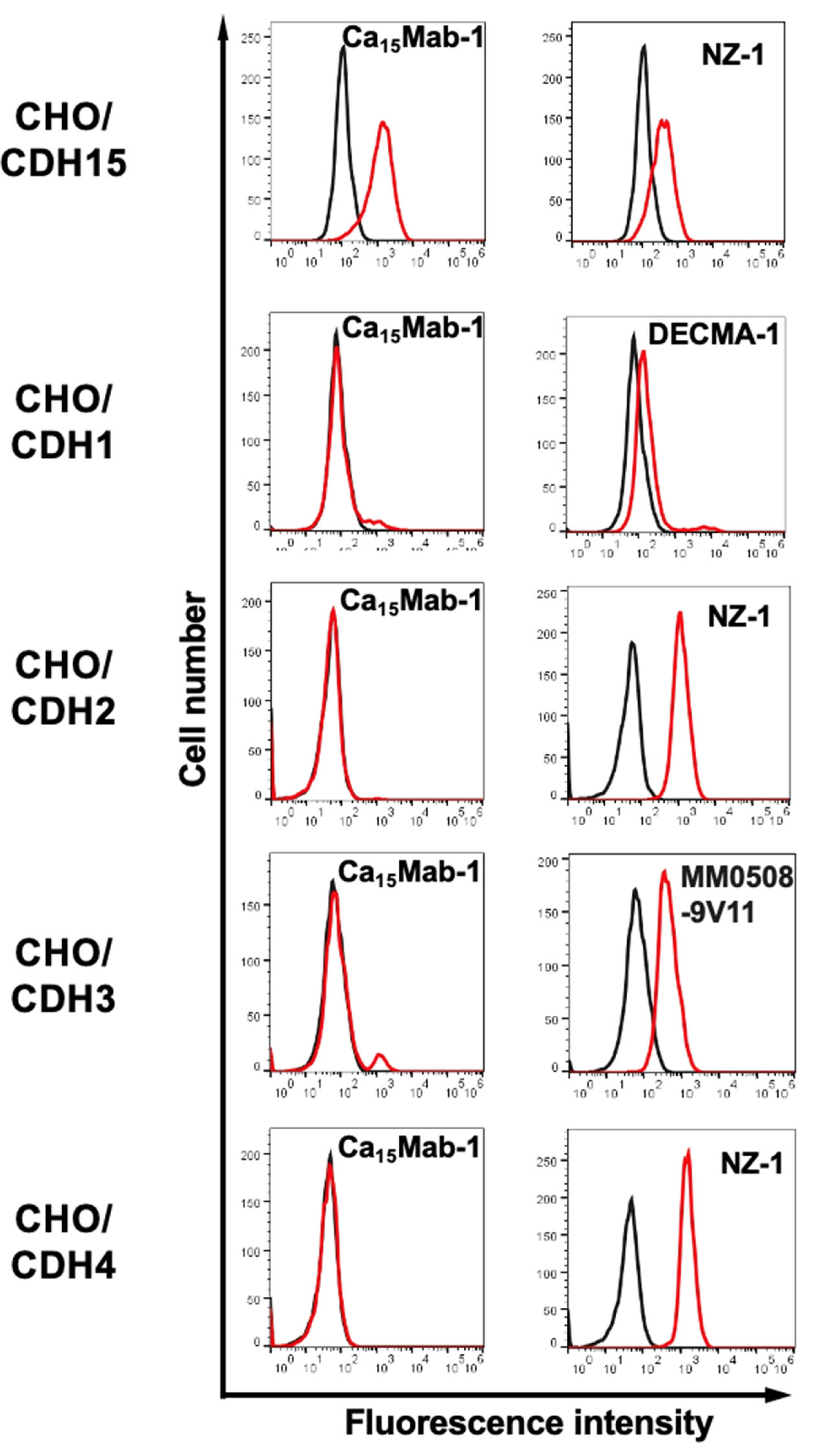

3.3. Specificity of Ca15Mabs to Type I Cadherin-Expressed CHO-K1

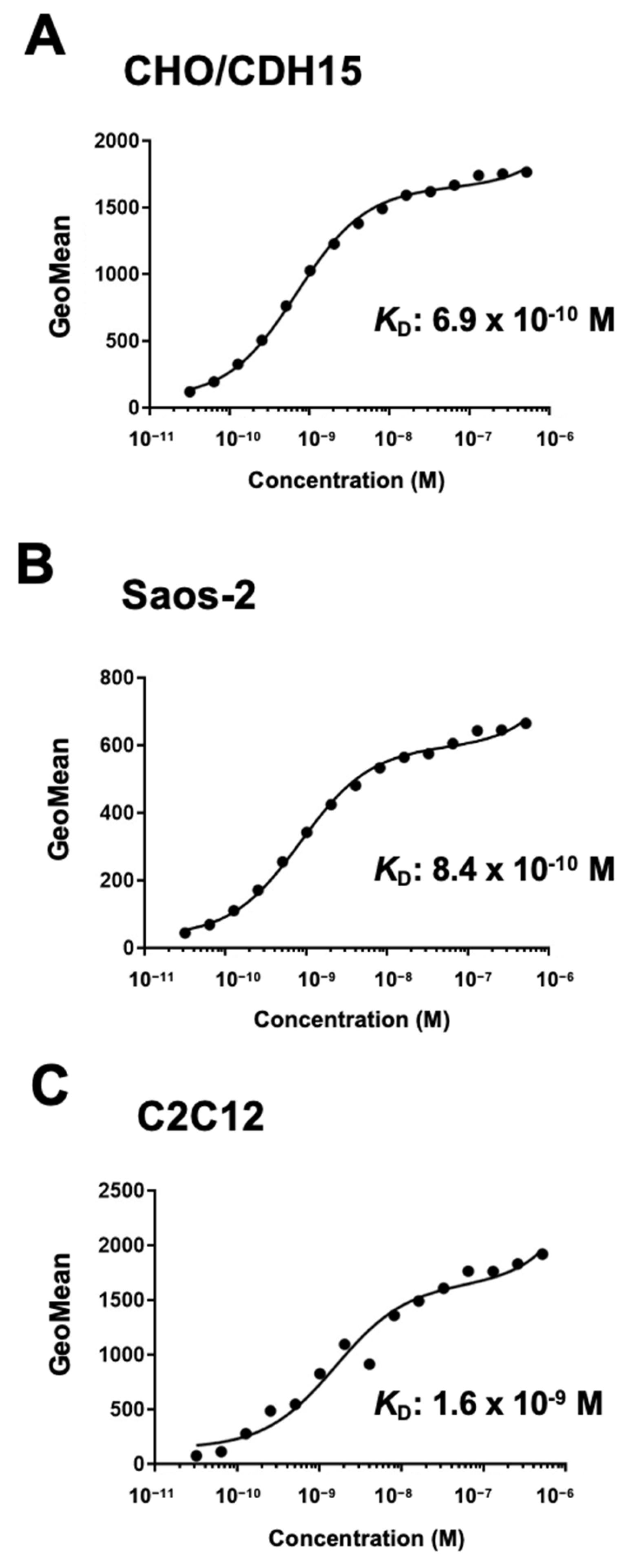

3.4. Determination of KD Values of Ca15Mab-1 by Flow Cytometry

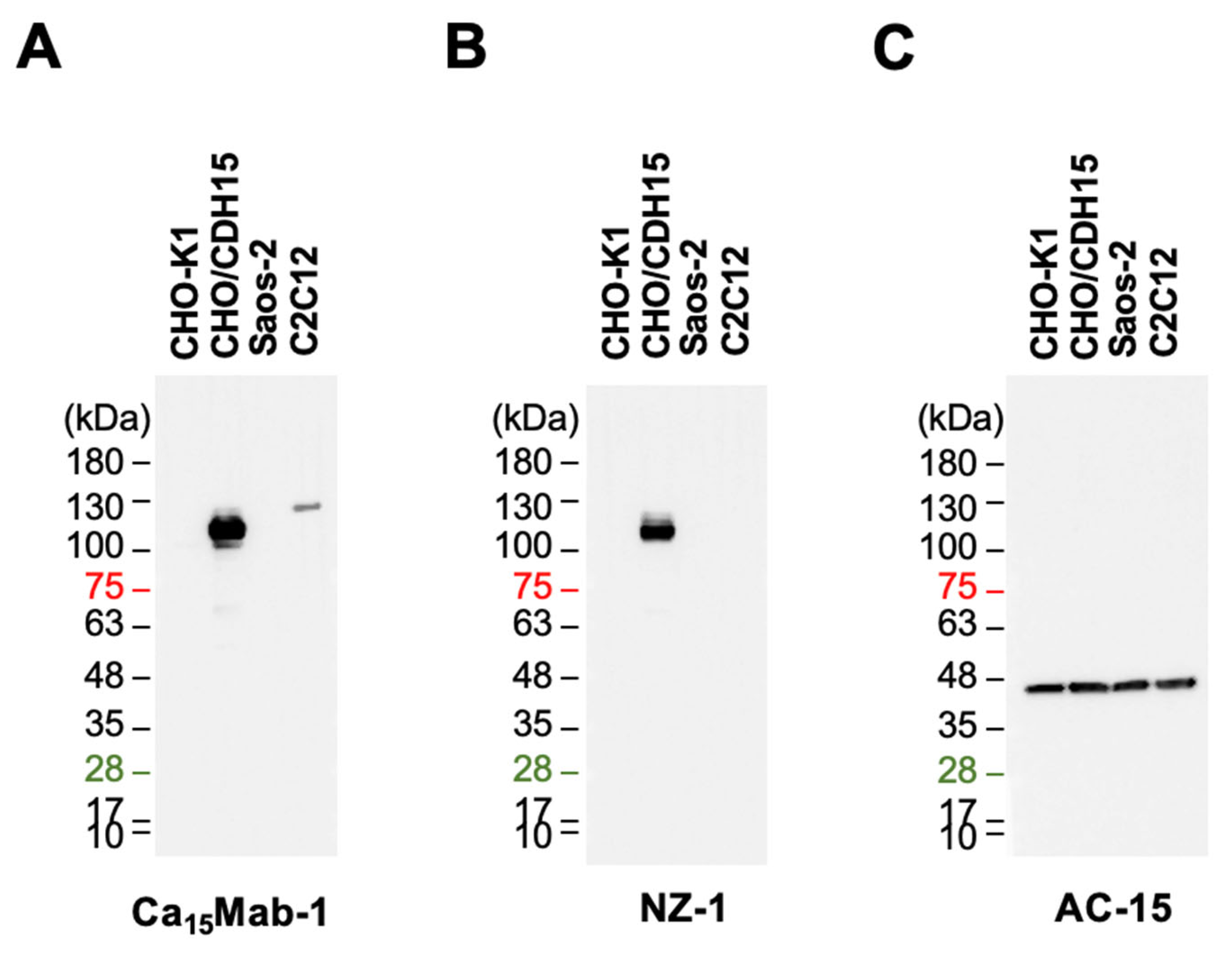

3.5. Immunoblotting Using Ca15Mab-1

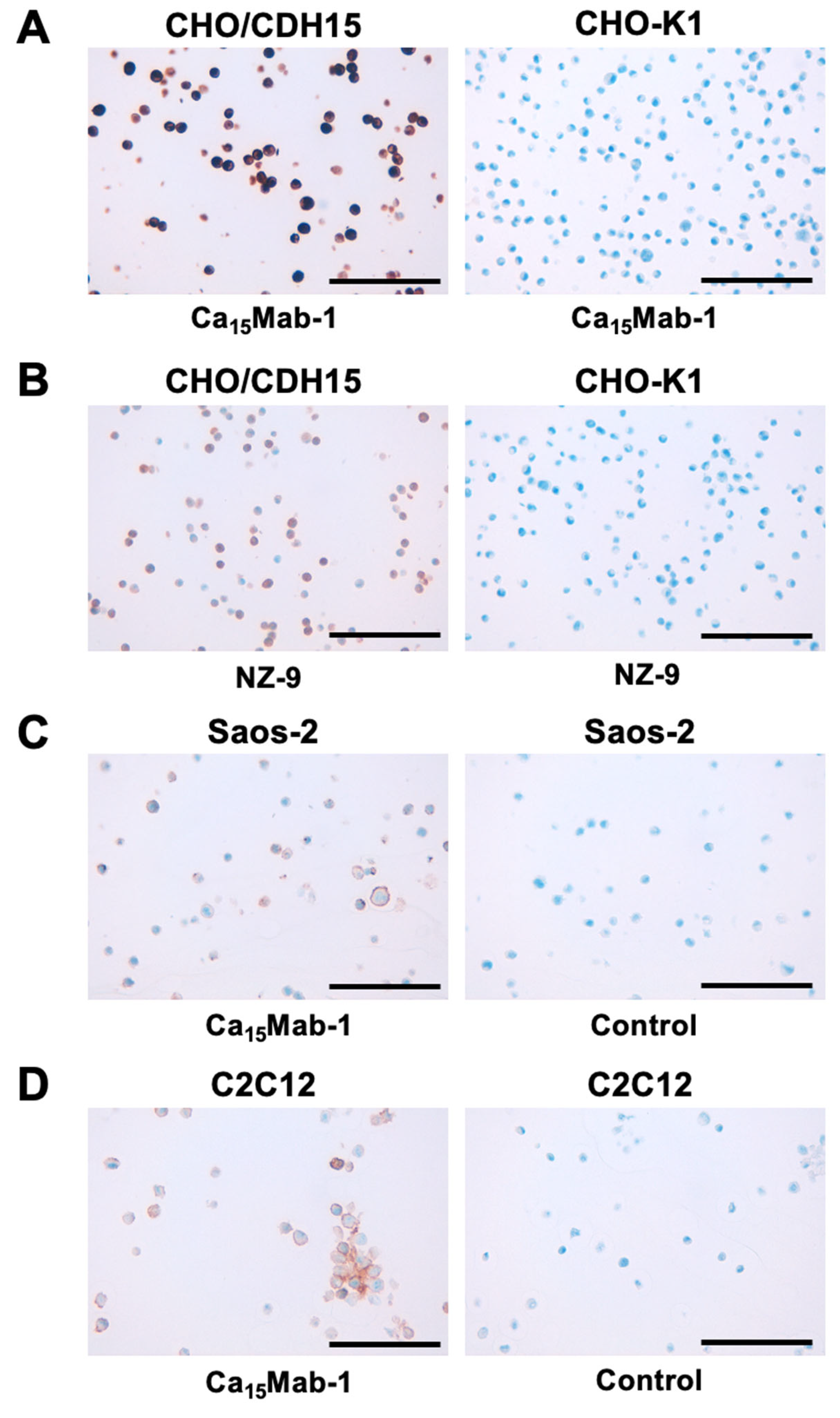

3.6. IHC Using Ca15Mab-1 in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Cell Blocks

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niessen, C.M.; Leckband, D.; Yap, A.S. Tissue organization by cadherin adhesion molecules: dynamic molecular and cellular mechanisms of morphogenetic regulation. Physiol Rev 2011, 91, 691–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Roy, F. Beyond E-cadherin: roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratheesh, A.; Yap, A.S. A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulpiau, P.; Gul, I.S.; van Roy, F. New insights into the evolution of metazoan cadherins and catenins. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2013, 116, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, H.; Takeichi, M. Evolution: structural and functional diversity of cadherin at the adherens junction. J Cell Biol 2011, 193, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.H.; Cooper, L.M.; Anastasiadis, P.Z. Cadherins and catenins in cancer: connecting cancer pathways and tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1137013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Cadherin Signaling in Cancer: Its Functions and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, R.S.; Cole, F.; Gaio, U.; et al. Close encounters: regulation of vertebrate skeletal myogenesis by cell-cell contact. J Cell Sci 2005, 118 Pt 11, 2355–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Diaz, C.; Nicolet, M.; Goudou, D.; Rieger, F.; Mège, R.M. N-cadherin and N-CAM-mediated adhesion in development and regeneration of skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul Disord 1993, 3, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donalies, M.; Cramer, M.; Ringwald, M.; Starzinski-Powitz, A. Expression of M-cadherin, a member of the cadherin multigene family, correlates with differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991, 88, 8024–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Walsh, F.S. The cell adhesion molecule M-cadherin is specifically expressed in developing and regenerating, but not denervated skeletal muscle. Development 1993, 117, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, M.; Lo, H.F.; Beckmann, A.G.; et al. Cadherin-dependent adhesion is required for muscle stem cell niche anchorage and maintenance. Development 2024, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irintchev, A.; Zeschnigk, M.; Starzinski-Powitz, A.; Wernig, A. Expression pattern of M-cadherin in normal, denervated, and regenerating mouse muscles. Dev Dyn 1994, 199, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, N.A.; Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating satellite cell function. Development 2015, 142, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A.S.; Rando, T.A. Tissue-specific stem cells: lessons from the skeletal muscle satellite cell. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Maltzahn, J.; Jones, A.E.; Parks, R.J.; Rudnicki, M.A. Pax7 is critical for the normal function of satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 16474–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relaix, F.; Bencze, M.; Borok, M.J.; et al. Perspectives on skeletal muscle stem cells. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, S.; Ma, Y.; Ohtani, T.; et al. Isolation, characterization, and molecular regulation of muscle stem cells. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011, 13, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozo, M.; Li, L.; Fan, C.M. Targeting β1-integrin signaling enhances regeneration in aged and dystrophic muscle in mice. Nat Med 2016, 22, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourikis, P.; Sambasivan, R.; Castel, D.; et al. A critical requirement for notch signaling in maintenance of the quiescent skeletal muscle stem cell state. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, T.H.; Quach, N.L.; Charville, G.W.; et al. Maintenance of muscle stem-cell quiescence by microRNA-489. Nature 2012, 482, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakkalakal, J.V.; Jones, K.M.; Basson, M.A.; Brack, A.S. The aged niche disrupts muscle stem cell quiescence. Nature 2012, 490, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, A.; Grund, C.; Franke, W.W.; Arnold, H.H. The cell adhesion molecule M-cadherin is not essential for muscle development and regeneration. Mol Cell Biol 2002, 22, 4760–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radice, G.L.; Rayburn, H.; Matsunami, H.; et al. Developmental defects in mouse embryos lacking N-cadherin. Dev Biol 1997, 181, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.J.; Rieder, M.K.; Arnold, H.H.; Radice, G.L.; Krauss, R.S. Niche Cadherins Control the Quiescence-to-Activation Transition in Muscle Stem Cells. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 2236–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Alway, S.E. Suppression of GSK-3β activation by M-cadherin protects myoblasts against mitochondria-associated apoptosis during myogenic differentiation. J Cell Sci 2011, 124 Pt 22, 3835–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a Novel Cancer-Specific Anti-HER2 Monoclonal Antibody H(2)Mab-250/H(2)CasMab-2 for Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanamiya, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an Anti-EphB4 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications Against Breast Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2023, 42, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, S.; Yamada, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. Establishment of EMab-134, a Sensitive and Specific Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody for Detecting Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells of the Oral Cavity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Li, G.; et al. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CCR5 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024, 43, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; et al. Development of Anti-Mouse CC Chemokine Receptor 8 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; Asano, T.; et al. Development of Anti-Human CC Chemokine Receptor 9 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1961, 9, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cheung, T.H.; Charville, G.W.; Rando, T.A. Isolation of skeletal muscle stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 1612–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cheung, T.H.; Charville, G.W.; et al. Chromatin modifications as determinants of muscle stem cell quiescence and chronological aging. Cell Rep 2013, 4, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, A.W.; Yi, L.; Natarajan, A.; et al. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, R.I.; Christensen, J.L.; Conboy, I.M.; et al. Isolation of adult mouse myogenic progenitors: functional heterogeneity of cells within and engrafting skeletal muscle. Cell 2004, 119, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burattini, S.; Ferri, P.; Battistelli, M.; et al. C2C12 murine myoblasts as a model of skeletal muscle development: morpho-functional characterization. Eur J Histochem 2004, 48, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Huang, C.; Pang, J.; et al. Advances in research on cell models for skeletal muscle atrophy. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 167, 115517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, K.W.; Choi, C.S.; Jun, H.S. Amelioration of muscle wasting by glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist in muscle atrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Stitt, T.N.; Gonzalez, M.; et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavlakadze, T.; McGeachie, J.; Grounds, M.D. Delayed but excellent myogenic stem cell response of regenerating geriatric skeletal muscles in mice. Biogerontology 2010, 11, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.A.; Zammit, P.S.; Ruiz, A.P.; Morgan, J.E.; Partridge, T.A. A population of myogenic stem cells that survives skeletal muscle aging. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, A.S.; Bildsoe, H.; Hughes, S.M. Evidence that satellite cell decrement contributes to preferential decline in nuclear number from large fibres during murine age-related muscle atrophy. J Cell Sci 2005, 118 Pt 20, 4813–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, C.S.; Lee, J.D.; Mula, J.; et al. Inducible depletion of satellite cells in adult, sedentary mice impairs muscle regenerative capacity without affecting sarcopenia. Nat Med 2015, 21, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, A.M.; Straub, V.W. δ-Sarcoglycan-deficient muscular dystrophy: from discovery to therapeutic approaches. Skelet Muscle 2011, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.G.; Huo, J.; Han, S.; et al. Depletion of skeletal muscle satellite cells attenuates pathology in muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Anti-HER2 Cancer-Specific mAb, H(2)Mab-250-hG(1), Possesses Higher Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity than Trastuzumab. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).