1. Introduction

Seafarers are exposed to health risks because they work for months under unstable and limited living conditions [

1]. Psychological stress from vibration, noise, and heat in the workplace, fatigue and isolation, cardiovascular disease, harmful substances, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation negatively affect the health of seafarers [

2,

3]. Seafarers do not have reliable medical access because they are in challenging conditions in some areas. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, seafarers were more severely affected, which distinguished them from land workers. At sea, long hours of work and face-to-face contact in inevitable proximity environments not only rapidly spread ship infections, but maritime isolation also makes it difficult to access proper healthcare [

4]. The absence of doctors and the limited supply of medical care in ship pharmacies represent obstacles to providing seafarers with reasonable quality medical care [

5,

6]. Moreover, the lack of fresh food, long working hours, and night shifts make it difficult for them to maintain a healthy lifestyle [

7,

8,

9]. In particular, unbalanced eating habits, high blood pressure, poor sleep quality, and short sleep duration can cause health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases.

Another health detriment among sailors described in the literature is decreased physical activity onboard. It has been found that sailors have reduced physical activity while on board compared to their time on land. While 70% of participants engaged in physical exercise at least twice a week while on land, only 39% did so while on board [

10]. The majority of seafarers are men. Especially, men generally have lower health literacy compared to women, resulting in poorer lifestyle choices and unawareness of serious disease symptoms. This lack of health knowledge leads to underutilization of health services and missed opportunities for early intervention and lifestyle improvements [

11]. Therefore, it is important to target men to enhance their health literacy and utilization of health services. Men are particularly inclined to self-monitor their health status for extended periods and seek information independently before seeking professional medical assistance [

12]. Portable monitoring devices and communication technologies are promising alternatives for fast and accurate medical tracking of sources of high health risk. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of men utilizing wearable devices to address their lower health literacy, resulting in improved awareness of health risks and better utilization of health services.

Given the significant reduction in physical activity among sailors while on board, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of maintaining regular physical activity for overall health and well-being. Korea is a world-class powerhouse in information technology. It is possible to launch effective health-related wearable device products and related technologies; however, their application in the medical field is limited compared to their demand [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Wearable devices are moving towards measuring vital signs and transmitting safe and reliable data using smartphone technologies [

17]. Instead of participating in set exercise programs, several individuals manage their health by monitoring their daily activities using smartphone applications and wearable devices [

18,

19]. By providing feedback, wearable devices help users set daily exercise targets, motivating them to lead healthier lifestyles and exercise consistently [

20,

21,

22]. Wearable devices also help individuals pursue healthier lifestyles, actively record physiological parameters, and track their metabolic status, thereby providing continuous medical data for disease diagnosis and treatment [

23]. Existing research specifically focusing on digital healthcare for seafarers is limited. As a result, there is little current knowledge on this topic. However, this study aims to evaluate the potential for monitoring the physical activity of seafarers, a professional group that requires digital healthcare due to limited access to medical services. We seek to provide insights into how portable monitoring devices can be utilized to address health risks and optimize the use of health services in challenging maritime environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included seafarers aged ≥19 years who owned smartphones, used applications, and consented to provide researchers with data on daily steps taken and calories burned, measured, and collected using a wearable device. Those who did not consent to provide data on physical activity or who were not familiar with using smartphone applications were excluded. Additionally, those who experienced difficulties in using wearable devices, owing to skin conditions at the wearing site were excluded. This is an exploratory study to evaluate whether data on users’ physical activity measured using wearable devices in a shipboard environment can be collected efficiently and whether it is possible for seafarers to monitor their physical activity. The study participants consisted of a total of 11 seafarers, selected from merchant ships whose captains agreed to participate in the study.

2.2. Study Procedure

The researchers explained the study method in detail to participants who met the selection criteria and obtained written consent from those who fully understood it. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the Pusan National University Hospital (IRB No. 2002-002-087). Those who agreed to participate in the study were provided with wrist-type wearable devices and related applications were installed on their smartphones (B. BAND, B Life Inc., Korea). The participants were asked to wear as many devices as possible while living on board. The study was conducted by monitoring the participants’ physical activity through an application-linked Internet webpage and providing mobile feedback. Subsequently, at week 12 of the study, the participants underwent wired checking to assess their sense of use and satisfaction with the wearable device smartphone application.

2.3. Outcome Measured

The study outcome measured included the following: physical activity measured using wearable devices onboard (number of steps taken and calorie consumption), participants’ adherence to using the wearable devices (daily wearing hours), wearable device–user smartphone application webpage access activation and failure, whether a failure occurs in the process of collecting measured participant data and uploading them to the administrator’s website, Medical-Seafarers Mobile Communication Originality, wearable-smartphone application satisfaction visual analog scale usage (0 = very dissatisfied; 10 = very satisfied), and confirmation of whether the participants intended to continue using the device in the future (yes, no).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

General characteristics and descriptive statistics of the 11 participants were summarized, and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.0. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as proportions in the data display.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

Eleven participants had no specific drug history (

Table 1). The average age of the 11 participants was 47.00 ± 21.13 years, and 11 participants were men. The average height of the participants was 172.18 ± 6.54cm. The average weight of the participants was 73.46 ± 13.45 kg. The average body mass index was 24.82 ± 4.03 kg/m2. The average waist circumference was 88.59 ± 11.76 cm.

3.2. The Basal Metabolic Rate

Regarding the basal metabolic rate, the overall rate was 1,457.64 ± 205.26 kcal. During the 12-week study, the total average number of steps taken was 5,729.30 count. The average metabolic rate of all the participants was 197.84 kcal.

3.3. Metabolic Components After the 12-Week Period

After comparing the average systolic blood pressure before and after the 12-week period, results showed that the scores decreased from 137.09 ± 13.05 to 124.36 ± 5.66, indicating a significant difference. After comparing the average diastolic blood pressure before and after the 12-week period, results showed that the scores decreased from 86.45 ± 10.24 to 77.45 ± 5.26, indicating a significant difference (P= .011). Regarding weight change, an average decrease of 1.19 kg was observed among the participants over 12 weeks, but this difference was not significant (

Figure 1). Additionally, the BDI and PSS indices were assessed for five individuals on board. The average BDI score among the five participants decreased from 19.50 to 15.50, and the average PSS score decreased from 16.75 to 14.75. However, these changes were not statistically significant.

3.4. User Satisfaction

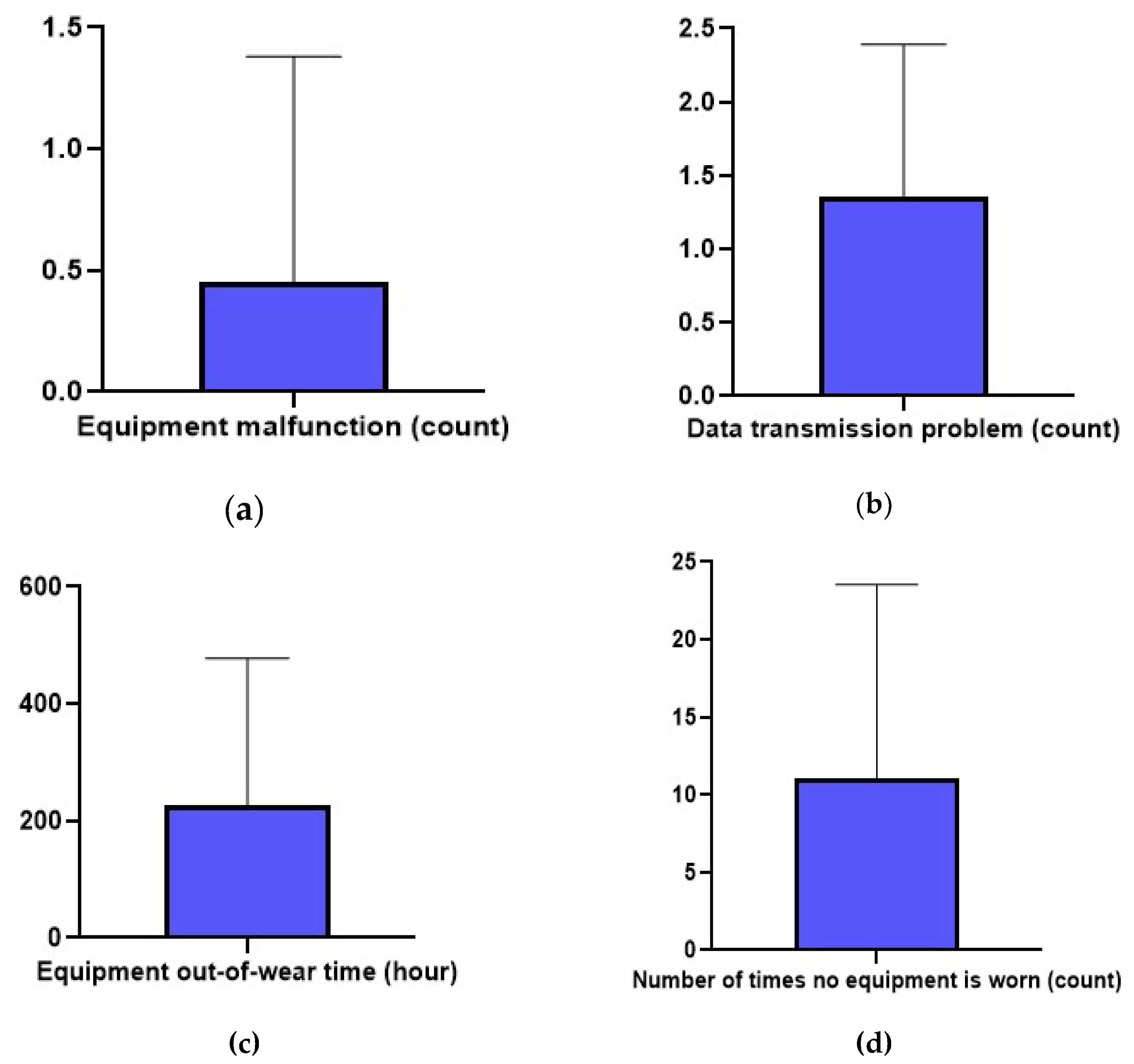

The average device satisfaction rate was 6.73 ± 1.62 points. The device malfunctioned an average of 0.45 ± 0.93 times. Participants experienced problems with transmitting and receiving data an average of 1.36 ± 1.03 times. Among the participants, the device was not worn an average of 11.09 ± 12.44 times, excluding the data of one participant who could not wear it for 13 days due to a device defect. Excluding this case, the out-of-wear time for equipment was found to be an average of 227.18 ± 250.80 hours for ten participants (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study assessed whether it was possible to monitor physical activity onboard a ship using wearable devices connected to a smartphone application among marine seafarers, a professional group that requires digital healthcare due to unfavorable access to medical care. This study confirmed the same effect of lowering participants’ blood pressure, as shown in previous studies. In 2016, a study confirmed that activity monitoring using wearable device-smartphone applications among patients with metabolic syndrome at the Pusan National University Hospital resolved metabolic syndrome in 45% of patients after a 12-week period, with a systolic blood pressure of 9.2 mmHg (6.71% vs. baseline) and diastolic blood pressure of 6.65 mmHg (7.98%) [

24]. Blood pressure measurements on wearable devices demonstrate the potential for user-friendly ways to enhance blood pressure management by enabling long-term monitoring to improve treatment adequacy and understanding users’ blood pressure responses to daily activities and stressors [

25].

By tracking the average number of steps and calorie consumption, we showed expectations for weight loss through simple monitoring. Regarding weight change, an average reduction of 1.19 kg was observed among the participants over 12 weeks. The use of wearable activity trackers has been shown to reduce body mass and increase physical activity compared with standard intervention programs for middle-aged or elderly people [

26]. Wearable devices can quickly provide users with health-related information and potentially affect an individual’s attitude and response to perceived health conditions by providing them with awareness of those conditions. Physical activity is important for good health and reduces the risk of death [

27]. Particularly for seafarers, obesity can increase cardiovascular risks, making it crucial to raise awareness about health [

28]. In addition to physical activity, we observed a decrease in depression and stress indices among young adults. Utilizing appropriate tools would be a beneficial approach for addressing mental health problems encountered by seafarers [

29]. Therefore, it is important to use a monitoring device as a means of informing users about their awareness of health conditions.

With wearable devices, the average number of steps per day and calories consumed can be used as indicators of seafarers’ activity. After the 12-week study period, the average number of steps taken was 5,729. The mean metabolic rate was 197. These results can be interpreted as disparities in vessel size and available workload. Public health guidelines recommend that adults should walk approximately 10,000 steps per, whereas 7,000–8,000 steps are considered a threshold for minimal physical activity [

30]. Walking fewer than 5,000 steps/day is linked to a higher prevalence of cardiac metabolic risk [

31]. This study highlighted the risk of metabolic syndrome in Asian seafarers, which is associated with chronic metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, nutrition, sleep patterns, work-related stress, fatigue, and physical activity, all of which are relevant issues at sea [

32,

33,

34]. In addition to health concerns, the labor structure of seafarers is aging, and the possibility of acute and cerebral cardiovascular diseases in their onboard lives is increasing [

35]. Given the challenges of accessing healthcare while onboard a ship, active intervention using wearable devices to monitor seafarers’ physical activity is critical for improving their health.

However, participants did not wear the device an average of 11.1 times, resulting in approximately 14.2% of the total 84 days in the study period being unwearable. This excludes participants who were unable to wear the device for 13 days due to device damage. Satisfaction with device use was found to be moderate, with an average rating of 6.7 out of 10. When asked about their intentions for future device usage, all seven participants who had no previous experience with using a device answered “No,” while three out of the four participants who had previous experience using a similar device answered “Yes.” This difference is a potential barrier to the use of wearable tracking devices. However, the intention not to use such devices in the future may be due to the nature of seafarers’ work, which involves considerable physical activity. Nevertheless, this study showed that wearable devices connected to smartphone applications can effectively monitor the physical activity of marine sailors who have difficulty accessing medical care.

The results of this study provide a clinical basis for the development of wearable devices in onboard environments. For example, a wearable device that can be worn at all times, with GPS-based physical activity tracking, sleep pattern monitoring, and sufficient battery life, will not only help in managing the health of seafarers but also in locating them in case of an emergency. This study is the first to investigate whether it is possible to manage health by monitoring the activities in the daily lives of marine seafarers using wearable devices. Furthermore, this study is novel, as it was conducted at an unprecedented time when global external activities were reduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Wearable devices will become more important after the COVID-19 pandemic, as they shift from in-person visits to clinical outpatient care environments, where dependence on telemedicine and remote monitoring increases [

36].

The study findings are somewhat difficult to interpret due to the limited sample size; however, the resulting evidence was consistent. We confirmed the possibility of digital healthcare using wearable devices, and in the future, we intend to conduct a follow-up study to evaluate whether this will help seafarers improve their healthcare and indicators on board. As a countermeasure, the most important and effective way to improve seafarers’ health is to prevent diseases that may worsen during boarding. Moreover, it is necessary to improve seafarers’ health-related behaviors. Therefore, considering the difficulties seafarers face in receiving timely medical services, digital healthcare through wearable devices is essential. Additionally, the ongoing management of seafarers’ health is crucial, and there will be many areas for further improvement and development in the future.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a 12-week pilot study using wearable devices for physical activity monitoring confirmed that it is possible to monitor the level of physical activity of seafarers on board. The 12-week wearable device-based physical activity monitoring allowed the participants to record their steps and metabolism and confirmed the effects of weight loss and blood pressure reduction, which are representative clinical indicators of metabolic syndrome. We also found a high satisfaction rate with the usage of wearable devices among the participants. Considering the difficulties seafarers face in receiving timely medical services despite having health problems while working onboard, digital healthcare through such wearable devices is essential. Moreover, the continuous monitoring and feedback provided by these devices can encourage seafarers to maintain healthier lifestyles, thereby potentially reducing the incidence of chronic diseases associated with physical inactivity. The integration of wearable technology into the daily routines of seafarers can serve as a proactive measure to address health issues before they become severe, thus improving the overall health and productivity of this workforce. Future research should explore the long-term benefits and potential challenges of implementing such digital healthcare solutions on a larger scale within the maritime industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J.T. and J.H.P.; methodology, S.H.S.; software, U.H.; validation, M.W.J., M.J.S. and Y.J.R; formal analysis, D.R.K.; investigation, Y.J.T. and J.H.P.; resources, M.W.J. and M.J.S.; data curation, S.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.T., D.R.K., Y.J.R. and J.H.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.J.T., D.R.K., and J.H.P.; visualization, U.H.; supervision, Y.J.T.; project administration, Y.J.T., D.R.K., and J.H.P.; funding acquisition, Y.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Biomedical Research Institute Grant (20200032) from Pusan National University Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the Pusan National University Hospital (IRB No. 2002-002-087).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author;

03141998@naver.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oldenburg, M.; Jensen, H.-J. Merchant seafaring: a changing and hazardous occupation. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenburg, M.; Felten, C.; Jörg, H.; Jensen, H.J. Physical influences on seafarers are different during their voyage episodes of port stay, river passage and sea passage: A maritime field study. Plos one 2020, 15, e0231309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenburg, M.; Baur, X.; Schlaich, C. Occupational risks and challenges of seafaring. J. Occup. Health 2010, 1007160136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandergeest, P.; Marschke, M.; MacDonnell, M. Seafarers in fishing: A year into the COVID-19 pandemic. Marine Policy 2021, 134, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, F.; Dauri, A.; Rizzo, N. Telemedicine and medical care to ships without a doctor on board. J. Telemed. Telecare 1998, 4, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittari, G.; Antonio, A.; Gopi, B.; Krutika, K.; Graziano, P.; Andrea, S.; Fabio, S.; Francesco, A. Design and evolution of the Seafarer’s Health Passport for supporting (tele)-medical assistance to seafarers. Int. arit. Health 2019, 70, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jeon, Y.W. A research on the perception level of seafarer related organizations in seafarer’s actual health care conditions. J. Navig. Port Res. 2015, 39, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.W.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, J.H. De Lege Frenda for Improvement of Marine Telemedicine Service System. J. Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education 2016, 28, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Investigation of occupational disease and prevention management of seafarers. Ph.D. Thesis, Pukyong National University, Busan, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geving, I.H.; Kristin, U.J.; Le Thi, M.S.; Sandsund, M. Physical activity levels among offshore fleet seafarers. Int. Marit. Health 2007, 58, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tharakan, T.; Christopher, C.K.; Aleksander, G.; Channa, N.J.; Nikolaos, S.; Andrea, S.; Minhas, S. Are sex disparities in COVID-19 a predictable outcome of failing men’s health provision? Nat. Rev. Urol. 2022, 19, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Annette, B.M.; Wittert, G.; Warin, M. “It’s sort of like being a detective”: Understanding how Australian men self-monitor their health prior to seeking help. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paré, G.; Leaver, C.; Bourget, C. Diffusion of the digital health self-tracking movement in Canada: results of a national survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e9388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, T.; Wijndaele, K.; Brage, S. Physical activity surveillance through smartphone apps and wearable trackers: examining the UK potential for nationally representative sampling. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e11898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukowicz, P.; Kirstein, T.; Tröster, G. Wearable systems for health care applications. Methods Inf. Med. 2004, 43, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, N.; Shenoy, S. Relation of pedometer steps count & self reported physical activity with health indices in middle aged adults. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2017, 11, S1017–S1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haghi, M.; Thurow, K.; Stoll, R. Wearable devices in medical internet of things: scientific research and commercially available devices. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2017, 23, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.; Duggan, M. Tracking for health. Pew research Center’s internet & American life project; PewResearchCenter: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jee, H. Review of researches on smartphone applications for physical activity promotion in healthy adults. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2017, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bort-Roig, J.; Gilson, N.D.; Puig-Ribera, A.; Contreras, R.S.; Trost, S.G. Measuring and influencing physical activity with smartphone technology: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Cheng, C.; Egger, G.; Binns, C.; Donovan, R. Using pedometers to increase physical activity in overweight and obese women: a pilot study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.P.; Wang, C.J.; Wang, J.J.; Lin, C.W.; Yang, Y.C.; Wang, J.S.; Yang, Y.K.; Yang, Y.C. The effects of an activity promotion system on active living in overweight subjects with metabolic abnormalities. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Ye, Z. Wearable health devices in health care: narrative systematic review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e18907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, U. , Tak, Y.J.; Song, S.; Chung, S.W.; Sung, S.M.; Lee, C.W.; Bae, M.; Ahn, H.Y. Feedback on physical activity through a wearable device connected to a mobile phone app in patients with metabolic syndrome: Pilot study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.S.; Cartledge, S.; Karmakar, C.; Rawstorn, J.C.; Fraser, S.F.; Chow, C.; Maddison, R. Validation and acceptability of a cuffless wrist-worn wearable blood pressure monitoring device among users and health care professionals: mixed methods study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e14706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheatham, S.W.; Stull, K.R.; Fantigrassi, M.; Motel, I. The efficacy of wearable activity tracking technology as part of a weight loss program: a systematic review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2018, 58, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.E.; Kim, J.W.; Jee, Y.S. Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, M.; Afendras, A.; Skiadas, C.; Renieri, D.; Tsaknaki, M.; Filippopoulos, I.; Liakou, C. Cardiovascular risk factors among 3712 Greek seafarers. Int. Marit. Health 2020, 71, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonglertmontree, W.; Kaewboonchoo, O.; Morioka, I.; Boonyamalik, P. Mental health problems and their related factors among seafarers: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Craig, C.L.; Brown, W.J.; Clemes, S.A.; De Cocker, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Hatano, Y.; Inoue, S.; Matsudo, S.M.; et al. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.D.; Cleland, V.J.; Shaw, K.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Cardiometabolic risk in younger and older adults across an index of ambulatory activity. Am. J. Prev.Med. 2009, 37, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, D.; Kalra, G.L.; Merchant, N.; Arora, A.; Khan, B.V. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in South Asians. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 731–743. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A.; Khurana, L. Obesity-related non-communicable diseases: South Asians vs White Caucasians. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, J.R.; Rasmussen, H.B. The metabolic syndrome among Danish seafarers: a follow-up study. Int. Marit. Health. 2016, 67, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, I.L. The impact on seafarers’ living and working conditions of changes in the structure of the shipping industry: report for discussion at the 29th Session of the Joint Maritime Commission, Geneva, 2001.

- Justin, G.; Nyenhuis, S.M. Wearable Technology and How This Can Be Implemented into Clinical Practice. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep 2020, 20, 36. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).