Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Microarray Dataset

Statistical Analysis

- Remove samples which exceed 99% line in RLE-NUSE T2 plot

RT-PCR Confirmation

Results

RMA Analysis of Whole Blood from Healthy Normal Control

RMA Analysis of Whole Blood from Septic Patients

Toll-like Signaling and Heat Shock Protein Expression in Septic Patients

Antigen Processing and Antigen Presentation Genes in Sepsis

TH17-like Innate Immune Transcription Factors in Sepsis

TH17-like and Treg Related Cytokines Are Up-Regulated During Sepsis

Th17-like Innate Immunity Related Effector Molecule Up-Regulation in Sepsis

Coagulation, Glycolysis, Acidosis, and Vasodilation Gene Dysregulation in Sepsis

Failure of T Lymphocyte Adaptive Immunity During Sepsis

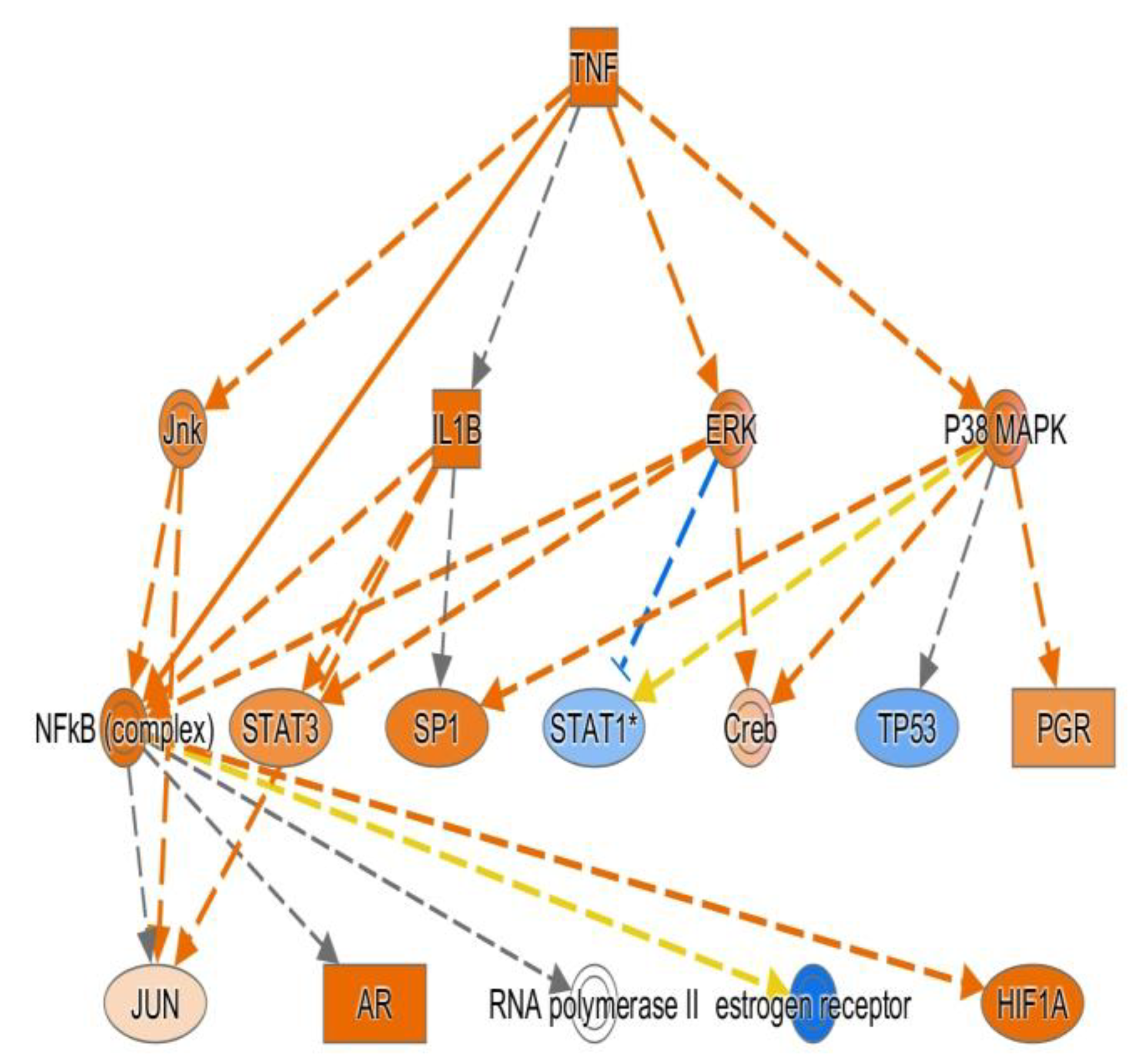

Results of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of Sepsis Patients Compared to Control

Discussion

Acknowledgement

Competing interests

References

- Hu, W.C. A Framework of All Discovered Immunological Pathways and Their Roles for Four Specific Types of Pathogens and Hypersensitivities. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.C. Human immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum infection: molecular evidence for a suboptimal THαβ and TH17 bias over ideal and effective traditional TH1 immune response. Malar J 2013, 12, 392. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.T.; Liao, M.T.; Tsai, K.W.; Lu, K.C.; Hu, W.C. Interplay of Chemokines Receptors, Toll-like Receptors, and Host Immunological Pathways. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Shih, L.J.; Hsieh, T.W.; Tsai, K.W.; Lu, K.C.; Liao, M.T.; Hu, W.C. Type 2 hypersensitivity disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, Graves' disease, myasthenia gravis, immune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, dermatomyositis, and graft-versus-host disease, are THαβ-dominant autoimmune diseases. Virulence 2024, 15, 2404225. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Tsai, K.W.; Lu, K.C.; Shih, L.J.; Hu, W.C. Cancer as a Dysfunctional Immune Disorder: Pro-Tumor TH1-like Immune Response and Anti-Tumor THαβ Immune Response Based on the Complete Updated Framework of Host Immunological Pathways. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.C.; Tsai, K.W.; Wang, Y.K.; Hu, W.C. Types of cell death and their relations to host immunological pathways. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 11755-11768. [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.C.; Tsai, K.W.; Hu, W.C. Role of TGFβ-producing regulatory T cells in scleroderma and end-stage organ failure. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35590. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.H.; Tsai, K.W.; Wu, Y.J.; Liao, M.T.; Lu, K.C.; Hu, W.C. The Framework for Human Host Immune Responses to Four Types of Parasitic Infections and Relevant Key JAK/STAT Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Howrylak, J.A.; Dolinay, T.; Lucht, L.; Wang, Z.; Christiani, D.C.; Sethi, J.M.; Xing, E.P.; Donahoe, M.P.; Choi, A.M. Discovery of the gene signature for acute lung injury in patients with sepsis. Physiol Genomics 2009, 37, 133-139. [CrossRef]

- Rotunno, M.; Hu, N.; Su, H.; Wang, C.; Goldstein, A.M.; Bergen, A.W.; Consonni, D.; Pesatori, A.C.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Wacholder, S., et al. A gene expression signature from peripheral whole blood for stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011, 4, 1599-1608. [CrossRef]

- Docke, W.D.; Randow, F.; Syrbe, U.; Krausch, D.; Asadullah, K.; Reinke, P.; Volk, H.D.; Kox, W. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med 1997, 3, 678-681.

- Kim, H.; Seed, B. The transcription factor MafB antagonizes antiviral responses by blocking recruitment of coactivators to the transcription factor IRF3. Nat Immunol 2010, 11, 743-750. [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.C.; Lo, D.; Glimcher, L.H. c-maf promotes T helper cell type 2 (Th2) and attenuates Th1 differentiation by both interleukin 4-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Exp Med 1998, 188, 1859-1866.

- Ruan, Q.; Kameswaran, V.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; DeVirgiliis, J.; Liou, H.C.; Beg, A.A.; Chen, Y.H. The Th17 immune response is controlled by the Rel-RORgamma-RORgamma T transcriptional axis. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 2321-2333. [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, S.; Tanaka, J.; Sugita, J.; Kosugi, M.; Shiratori, S.; Wakasa, K.; Shono, Y.; Shigematsu, A.; Kondo, T.; Kobayashi, T., et al. Expansion of CD4(+)CD25 (+) regulatory T cells from cord blood CD4(+) cells using the common gamma-chain cytokines (IL-2 and IL-15) and rapamycin. Ann Hematol 2011, 90, 617-624. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.C.; Nadeau, K.C.; Tu, W.; Hwa, V.; Dionis, K.; Bezrodnik, L.; Teper, A.; Gaillard, M.; Heinrich, J.; Krensky, A.M., et al. Cutting edge: Decreased accumulation and regulatory function of CD4+ CD25(high) T cells in human STAT5b deficiency. J Immunol 2006, 177, 2770-2774.

- Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S.; Iglesias, A.H.; Korn, T.; Farez, M.F.; Bettelli, E.; Caccamo, M.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Gonda, H.; Sugai, M.; Nambu, Y.; Katakai, T.; Agata, Y.; Mori, K.J.; Yokota, Y.; Shimizu, A. The balance between Pax5 and Id2 activities is the key to AID gene expression. J Exp Med 2003, 198, 1427-1437. [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, K.; Nishizumi, H.; Umemori, H.; Aizawa, S.; Takatsu, K.; Yamamoto, T. Distinctive roles of Fyn and Lyn in IgD- and IgM-mediated signaling. Int Immunol 1999, 11, 1441-1449.

- Kirstetter, P.; Thomas, M.; Dierich, A.; Kastner, P.; Chan, S. Ikaros is critical for B cell differentiation and function. Eur J Immunol 2002, 32, 720-730.

- Netea, M.G.; Azam, T.; Lewis, E.C.; Joosten, L.A.; Wang, M.; Langenberg, D.; Meng, X.; Chan, E.D.; Yoon, D.Y.; Ottenhoff, T., et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-32 production through a caspase- 1/IL-18/interferon-gamma-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med 2006, 3, e277. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Best, J.A.; Knell, J.; Yang, E.; Sheridan, A.D.; Jesionek, A.K.; Li, H.S.; Rivera, R.R.; Lind, K.C.; D'Cruz, L.M., et al. The transcriptional regulators Id2 and Id3 control the formation of distinct memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Nat Immunol 2011, 12, 1221-1229. [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Karl, I.E. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 138-150. [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer, A.; Oberholzer, C.; Moldawer, L.L. Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock 2001, 16, 83-96.

- Girardin, E.; Grau, G.E.; Dayer, J.M.; Roux-Lombard, P.; Lambert, P.H. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 in the serum of children with severe infectious purpura. N Engl J Med 1988, 319, 397-400. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L. Germs. N Engl J Med 1972, 287, 553-555. [CrossRef]

- Warren, H.S. Strategies for the treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 1997, 336, 952-953. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.J., Jr.; Agosti, J.M.; Opal, S.M.; Lowry, S.F.; Balk, R.A.; Sadoff, J.C.; Abraham, E.; Schein, R.M.; Benjamin, E. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein. The Soluble TNF Receptor Sepsis Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 1697-1702. [CrossRef]

- Zeni, F.; Freeman, B.; Natanson, C. Anti-inflammatory therapies to treat sepsis and septic shock: a reassessment. Crit Care Med 1997, 25, 1095-1100.

- Ward, P.A. Immunosuppression in sepsis. JAMA 2011, 306, 2618-2619. [CrossRef]

- Kasten, K.R.; Tschop, J.; Adediran, S.G.; Hildeman, D.A.; Caldwell, C.C. T cells are potent early mediators of the host response to sepsis. Shock 2010, 34, 327-336. [CrossRef]

- Hein, F.; Massin, F.; Cravoisy-Popovic, A.; Barraud, D.; Levy, B.; Bollaert, P.E.; Gibot, S. The relationship between CD4+CD25+CD127- regulatory T cells and inflammatory response and outcome during shock states. Crit Care 2010, 14, R19. [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Chung, C.S.; Xu, Y.X.; Evans, T.A.; Redmond, K.M.; Chaudry, I.H. Increased inducible apoptosis in CD4+ T lymphocytes during polymicrobial sepsis is mediated by Fas ligand and not endotoxin. Immunology 1999, 97, 45-55.

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Tinsley, K.W.; Swanson, P.E.; Grayson, M.H.; Osborne, D.F.; Wagner, T.H.; Cobb, J.P.; Coopersmith, C.; Karl, I.E. Depletion of dendritic cells, but not macrophages, in patients with sepsis. J Immunol 2002, 168, 2493-2500.

- Unsinger, J.; Herndon, J.M.; Davis, C.G.; Muenzer, J.T.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Ferguson, T.A. The role of TCR engagement and activation-induced cell death in sepsis-induced T cell apoptosis. J Immunol 2006, 177, 7968-7973.

- Manjuck, J.; Saha, D.C.; Astiz, M.; Eales, L.J.; Rackow, E.C. Decreased response to recall antigens is associated with depressed costimulatory receptor expression in septic critically ill patients. J Lab Clin Med 2000, 135, 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Scumpia, K.M.; Scumpia, P.O.; Weinstein, J.S.; Delano, M.J.; Cuenca, A.G.; Nacionales, D.C.; Wynn, J.L.; Lee, P.Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Efron, P.A., et al. B cells enhance early innate immune responses during bacterial sepsis. J Exp Med 2011, 208, 1673-1682. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, A.M.; Morris, N.L.; Cannon, A.R.; Khan, O.M.; Gagnon, R.C.; Movtchan, N.V.; van Langeveld, I.; Li, X.; Gao, B.; Choudhry, M.A. Interleukin-22 Prevents Microbial Dysbiosis and Promotes Intestinal Barrier Regeneration Following Acute Injury. Shock 2017, 48, 657-665. [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.H.; Zheng, Z.N.; Xiao, C.X.; Liu, X.; Lin, X.Q. IL-22 relieves sepsis-induced liver injury via activating JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2020, 34, 1719-1727. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ling, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Kong, X. Interleukin-22 protects from endotoxemia by inducing suppressive F4/80(+)Ly6G(hi)Ly6C(hi) cells population. BMC Immunol 2022, 23, 45. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Peng, W.; Deng, H.; Ni, H.; Tong, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, S.; Qian, J.; Liang, A., et al. Th17/Treg balance: the bloom and wane in the pathophysiology of sepsis. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1356869. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, M.; Chang, Y.; Yu, M.; Meng, Y.; Wan, X. Prediction of Th17/Treg cell balance on length of stay in intensive care units of patients with sepsis. J Intensive Med 2024, 4, 240-246. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, J.M.; Kronfeld, D.S. In vivo studies of hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis in endotoxic shock. Am J Physiol 1985, 248, E309-316.

- Hornef, M.W.; Wick, M.J.; Rhen, M.; Normark, S. Bacterial strategies for overcoming host innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2002, 3, 1033-1040. [CrossRef]

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 201743_at | 1.37E-04 | up | 2.18 | CD14 |

| 204924_at | 1.45E-10 | up | 3.38 | TLR2 |

| 210166_at | 9.16E-08 | up | 2.40 | TLR5 |

| 210176_at | 0.001131 | up | 2.07 | TLR1 |

| 213817_at | 3.14E-13 | up | 21.04 | IRAK3 |

| 219618_at | 1.89E-09 | up | 2.69 | IRAK4 |

| 220832_at | 4.76E-09 | up | 5.16 | TLR8 |

| 221060_s_at | 6.62E-07 | up | 3.33 | TLR4 |

| 212184_s_at | 2.03E-05 | up | 2.61 | TAB2 |

| 221705_s_at | 8.46E-10 | down | 2.08 | SIKE1 |

| 205118_at | 1.05E-10 | down | 7.61 | FPR1 |

| 210772_at | 2.06E-08 | up | 4.78 | FPR2 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 201137_s_at | 5.80E-04 | down | 2.09 | HLA-DPB1 |

| 203290_at | 2.56E-08 | down | 5.19 | HLA-DQA1 |

| 204670_x_at | 6.77E-08 | down | 2.85 | HLA-DRB1/B4 |

| 205671_s_at | 1.27E-04 | down | 2.02 | HLA-DOB |

| 208306_x_at | 1.53E-06 | down | 2.44 | HLA-DRB1 |

| 208894_at | 8.06E-07 | down | 2.76 | HLA-DRA |

| 209312_x_at | 1.24E-06 | down | 2.67 | HLA-DRB1/B4/B5 |

| 209823_x_at | 8.65E-04 | down | 2.08 | HLA-DQB1 |

| 210294_at | 7.08E-10 | down | 2.25 | TAPBP |

| 210528_at | 1.28E-05 | down | 2.57 | MR1 |

| 211948_x_at | 3.66E-28 | down | 11.75 | BAT2L2 |

| 211990_at | 5.10E-06 | down | 3.19 | HLA-DPA1 |

| 212384_at | 8.83E-15 | down | 2.98 | HLABAT1 |

| 212671_s_at | 0.002545 | down | 2.27 | HLA-DQA1/A2 |

| 214055_x_at | 1.16E-24 | down | 9.42 | BAT2L2 |

| 215193_x_at | 2.90E-06 | down | 2.52 | HLA-DRB1/B3/B4 |

| 221491_x_at | 1.50E-06 | down | 2.25 | HLA-DRB1/B3/B4/B5 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 201473_at | 3.65E-09 | up | 2.46 | JUNB |

| 201502_s_at | 9.16E-07 | down | 2.36 | NFKBIA |

| 202527_s_at | 5.77E-09 | up | 3.24 | SMAD4 |

| 203077_s_at | 4.90E-07 | up | 2.37 | SMAD2 |

| 203574_at | 4.37E-10 | up | 5.18 | NFIL3 |

| 204039_at | 4.62E-08 | up | 2.06 | CEBPA |

| 204203_at | 9.92E-07 | up | 2.17 | CEBPG |

| 205841_at | 1.02E-13 | up | 4.66 | JAK2 |

| 206036_s_at | 8.46E-12 | down | 4.75 | REL |

| 206359_at | 3.22E-07 | up | 2.09 | SOCS3 |

| 206363_at | 9.68E-06 | down | 2.26 | MAF |

| 208991_at | 1.49E-13 | down | 3.22 | STAT3 |

| 209604_s_at | 2.74E-19 | down | 6.55 | GATA3 |

| 209969_s_at | 2.12E-08 | down | 4.75 | STAT1 |

| 210479_s_at | 5.21E-15 | down | 7.85 | RORA |

| 212501_at | 1.73E-07 | up | 2.17 | CEBPB |

| 212550_at | 7.19E-10 | up | 2.52 | STAT5B |

| 213006_at | 6.03E-10 | up | 4.21 | CEBPD |

| 218221_at | 1.49E-11 | up | 2.35 | ARNT |

| 218559_s_at | 9.49E-07 | up | 3.35 | MAFB |

| 218880_at | 5.34E-11 | up | 3.75 | FOSL2 |

| 208808_s_at | 1.07E-11 | up | 9.12 | HMGB |

| 200989_at | 1.17E-06 | up | 3.00 | HIF1A |

| 221969_at | 9.96E-13 | down | 4.20 | PAX5 |

| 203140_at | 3.09E-10 | up | 3.69 | BCL6 |

| 210105_s_at | 9.37E-10 | down | 3.32 | FYN |

| 210754_s_at | 2.98E-10 | down | 3.55 | LYN |

| 217620_s_at | 4.31E-12 | down | 2.79 | PIK3CB |

| 221756_at | 5.52E-10 | down | 2.62 | PIK3IP1 |

| 204054_at | 2.56E-10 | up | 5.51 | PTEN |

| 206370_at | 2.95E-09 | down | 2.44 | PIK3CG |

| 212240_s_at | 4.29E-13 | down | 4.51 | PIK3R1 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 201110_s_at | 2.02E-09 | up | 8.27 | THBS1 |

| 203085_s_at | 1.57E-08 | up | 2.33 | TGFB1 |

| 203828_s_at | 7.88E-05 | down | 2.13 | IL32 |

| 205016_at | 8.33E-10 | up | 4.86 | TGFA |

| 205992_s_at | 4.40E-06 | up | 3.58 | IL15 |

| 208114_s_at | 7.75E-20 | down | 5.85 | ISG20L2 |

| 208200_at | 3.06E-11 | down | 4.80 | IL1A |

| 212195_at | 3.90E-06 | up | 2.67 | IL6ST |

| 209555_s_at | 2.87E-05 | up | 3.18 | CD36 |

| 212657_s_at | 2.96E-07 | up | 2.31 | IL1RN |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 201642_at | 1.42E-09 | up | 2.32 | IFNGR2 |

| 202948_at | 5.77E-10 | up | 6.46 | IL1R1 |

| 203233_at | 2.36E-10 | up | 3.27 | IL4R |

| 204191_at | 2.98E-07 | up | 2.06 | IFNAR1 |

| 204731_at | 7.48E-21 | down | 11.93 | TGFBR3 |

| 204786_s_at | 5.23E-19 | down | 6.86 | IFNAR2 |

| 205227_at | 2.89E-05 | up | 2.68 | IL1RAP |

| 205291_at | 2.89E-08 | down | 2.44 | IL2RB |

| 205707_at | 1.73E-09 | down | 2.41 | IL17RA |

| 205798_at | 2.48E-24 | down | 31.79 | IL7R |

| 205926_at | 1.06E-09 | down | 2.19 | IL27RA |

| 205945_at | 1.49E-22 | down | 16.69 | IL6R |

| 206618_at | 4.70E-09 | up | 12.92 | IL18R1 |

| 207072_at | 5.22E-08 | up | 4.93 | IL18RAP |

| 211372_s_at | 1.76E-08 | up | 10.68 | IL1R2 |

| 211676_s_at | 6.66E-09 | up | 4.61 | IFNGR1 |

| 205159_at | 1.17E-06 | up | 2.51 | CSF2RB |

| 210340_s_at | 4.36E-10 | up | 2.30 | CSF2RA |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 200602_at | 3.75E-12 | up | 4.38 | APP |

| 206157_at | 8.31E-08 | up | 3.27 | PTX3 |

| 208691_at | 0.001264 | up | 2.49 | TFRC |

| 208703_s_at | 1.26E-07 | up | 3.05 | APLP2 |

| 219890_at | 1.43E-12 | up | 7.83 | CLEC5A |

| 220496_at | 2.59E-07 | up | 3.33 | CLEC1B |

| 205033_s_at | 1.17E-05 | up | 4.79 | DEFA1/A1B/A3 |

| 207269_at | 2.87E-05 | up | 6.67 | DEFA4 |

| 201943_s_at | 7.91E-12 | up | 6.94 | CPD |

| 204961_s_at | 7.26E-08 | up | 2.02 | NCF1/1B/1C |

| 207677_s_at | 5.88E-10 | up | 2.66 | NCF4 |

| 214084_x_at | 1.31E-08 | up | 2.25 | NCF1C |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 200985_s_at | 4.85E-11 | up | 6.59 | CD59 |

| 201925_s_at | 2.14E-07 | up | 5.61 | CD55 |

| 202953_at | 7.01E-06 | up | 2.53 | C1QB |

| 205786_s_at | 5.02E-13 | up | 4.05 | ITGAM |

| 206244_at | 6.06E-12 | up | 6.76 | CR1 |

| 208783_s_at | 0.004769 | up | 2.21 | CD46 |

| 209906_at | 7.48E-09 | up | 4.34 | C3AR1 |

| 210184_at | 1.17E-06 | up | 2.07 | ITGAX |

| 218232_at | 1.52E-08 | up | 3.97 | C1QA |

| 218983_at | 7.83E-08 | up | 2.64 | C1RL |

| 220088_at | 9.13E-08 | up | 2.49 | C5AR1 |

| 202910_s_at | 3.42E-07 | up | 2.26 | CD97 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 203167_at | 1.02E-13 | up | 3.14 | TIMP2 |

| 203936_s_at | 2.89E-16 | up | 10.59 | MMP9 |

| 206871_at | 1.04E-06 | up | 5.39 | ELANE |

| 207329_at | 3.41E-11 | up | 32.06 | MMP8 |

| 207890_s_at | 1.30E-11 | up | 3.11 | MMP25 |

| 202833_s_at | 2.83E-09 | up | 2.78 | SERPINA1 |

| 204614_at | 5.64E-08 | up | 3.07 | SERPINB2 |

| 212268_at | 8.64E-11 | up | 5.64 | SERPINB1 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 203305_at | 2.16E-04 | up | 2.18 | F13A1 |

| 204714_s_at | 1.87E-08 | up | 3.93 | F5 |

| 205756_s_at | 2.79E-05 | up | 2.08 | F8 |

| 205871_at | 7.54E-07 | down | 3.12 | PLGLA/B1/B2 |

| 206655_s_at | 2.25E-08 | up | 5.37 | GP1BB/SEPT5 |

| 207808_s_at | 6.30E-08 | up | 2.88 | PROS1 |

| 211924_s_at | 5.53E-07 | up | 2.33 | PLAUR |

| 212245_at | 6.18E-07 | up | 2.30 | MCFD2 |

| 213258_at | 1.07E-06 | up | 2.35 | TFPI |

| 213506_at | 0.002877 | up | 2.35 | F2RL1 |

| 214415_at | 1.30E-09 | down | 5.54 | PLGLB1/B2 |

| 216956_s_at | 4.64E-05 | up | 2.39 | ITGA2B |

| 218718_at | 2.79E-10 | up | 9.39 | PDGFC |

| 204627_s_at | 1.30E-06 | up | 4.18 | ITGB3 |

| 203887_s_at | 8.66E-09 | up | 4.53 | THBD |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 200650_s_at | 2.02E-09 | up | 2.71 | LDHA |

| 200737_at | 2.94E-11 | up | 3.17 | PGK1 |

| 201030_x_at | 9.45E-05 | down | 2.02 | LDHB |

| 201251_at | 2.51E-10 | up | 2.67 | PKM2 |

| 202464_s_at | 6.45E-09 | up | 7.30 | PFKFB3 |

| 202934_at | 9.80E-14 | up | 4.77 | HK2 |

| 202990_at | 2.15E-12 | up | 4.20 | PYGL |

| 203502_at | 1.24E-04 | up | 3.67 | BPGM |

| 205936_s_at | 5.17E-12 | up | 4.99 | HK3 |

| 206348_s_at | 9.53E-11 | up | 2.60 | PDK3 |

| 208308_s_at | 3.92E-09 | up | 2.22 | GPI |

| 209992_at | 3.99E-09 | up | 11.77 | PFKFB2 |

| 213453_x_at | 2.13E-12 | up | 2.18 | GAPDH |

| 217294_s_at | 3.28E-06 | up | 2.62 | ENO1 |

| 218273_s_at | 1.01E-07 | down | 2.25 | PDP1 |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 200078_s_at | 6.15E-13 | up | 2.53 | ATP6V0B |

| 201171_at | 4.49E-10 | up | 2.48 | ATP6V0E1 |

| 201443_s_at | 5.84E-06 | up | 2.33 | ATP6AP2 |

| 201971_s_at | 4.45E-13 | down | 5.21 | ATP6V1A |

| 202872_at | 1.95E-10 | up | 6.18 | ATP6V1C1 |

| 202874_s_at | 6.99E-10 | up | 5.72 | ATP6V1C1 |

| 204158_s_at | 5.14E-08 | up | 2.07 | TCIRG1 |

| 208898_at | 2.66E-09 | up | 2.41 | ATP6V1D |

| 213587_s_at | 1.13E-08 | down | 2.07 | ATP6V0E2 |

| 206208_at | 1.00E-11 | up | 3.51 | CA4 |

| 206209_s_at | 4.18E-15 | up | 7.98 | CA4 |

| 209301_at | 2.78E-06 | up | 3.42 | CA2 |

| 212536_at | 4.38E-09 | up | 4.21 | ATP11B |

| 213582_at | 1.89E-08 | up | 2.24 | ATP11A |

| Probe ID | Pvalue | Arrow | Fold | Gene |

| 205255_x_at | 3.09E-08 | down | 2.96 | TCF7 |

| 205456_at | 5.31E-08 | down | 2.88 | CD3E |

| 205488_at | 1.01E-05 | down | 2.87 | GZMA |

| 205495_s_at | 5.33E-10 | down | 4.38 | GNLY |

| 205758_at | 1.20E-07 | down | 3.26 | CD8A |

| 206666_at | 1.84E-07 | down | 3.45 | GZMK |

| 206804_at | 1.10E-15 | down | 5.12 | CD3G |

| 207460_at | 3.78E-09 | down | 2.50 | GZMM |

| 208003_s_at | 5.52E-18 | down | 12.04 | NFAT5 |

| 209671_x_at | 3.58E-08 | down | 2.77 | TRAC |

| 209813_x_at | 1.49E-09 | down | 4.42 | TARP |

| 210164_at | 8.91E-09 | down | 3.76 | GZMB |

| 210321_at | 8.94E-10 | down | 5.80 | GZMH |

| 210370_s_at | 1.34E-07 | down | 2.48 | LY9 |

| 210556_at | 4.68E-08 | down | 2.85 | NFATC3 |

| 210972_x_at | 1.78E-07 | down | 2.88 | TRAC/J17/V20 |

| 211796_s_at | 6.35E-06 | down | 2.93 | TRBC1/C2 |

| 212759_s_at | 3.98E-16 | down | 3.93 | TCF7L2 |

| 213193_x_at | 2.53E-06 | down | 2.92 | TRBC1 |

| 213539_at | 1.00E-08 | down | 3.19 | CD3D |

| 214617_at | 2.22E-06 | down | 2.65 | PRF1 |

| 216191_s_at | 4.71E-07 | down | 4.76 | TRDV3 |

| 216920_s_at | 2.28E-10 | down | 5.34 | TARP/TRGC2 |

| 217143_s_at | 1.26E-08 | down | 6.06 | TRD@ |

| 217527_s_at | 2.12E-13 | down | 5.80 | NFATC2IP |

| 220684_at | 7.39E-09 | down | 2.08 | TBX21 |

| 220704_at | 2.15E-10 | down | 5.69 | IKZF1 |

| 214032_at | 6.60E-08 | down | 2.52 | ZAP70 |

| 204891_s_at | 4.58E-08 | down | 3.31 | LCK |

| 205831_at | 4.40E-10 | down | 3.93 | CD2 |

| 201565_s_at | 8.13E-13 | down | 4.17 | ID2 |

| 213931_at | 7.33E-08 | down | 3.55 | ID2/2B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).