1. Introduction

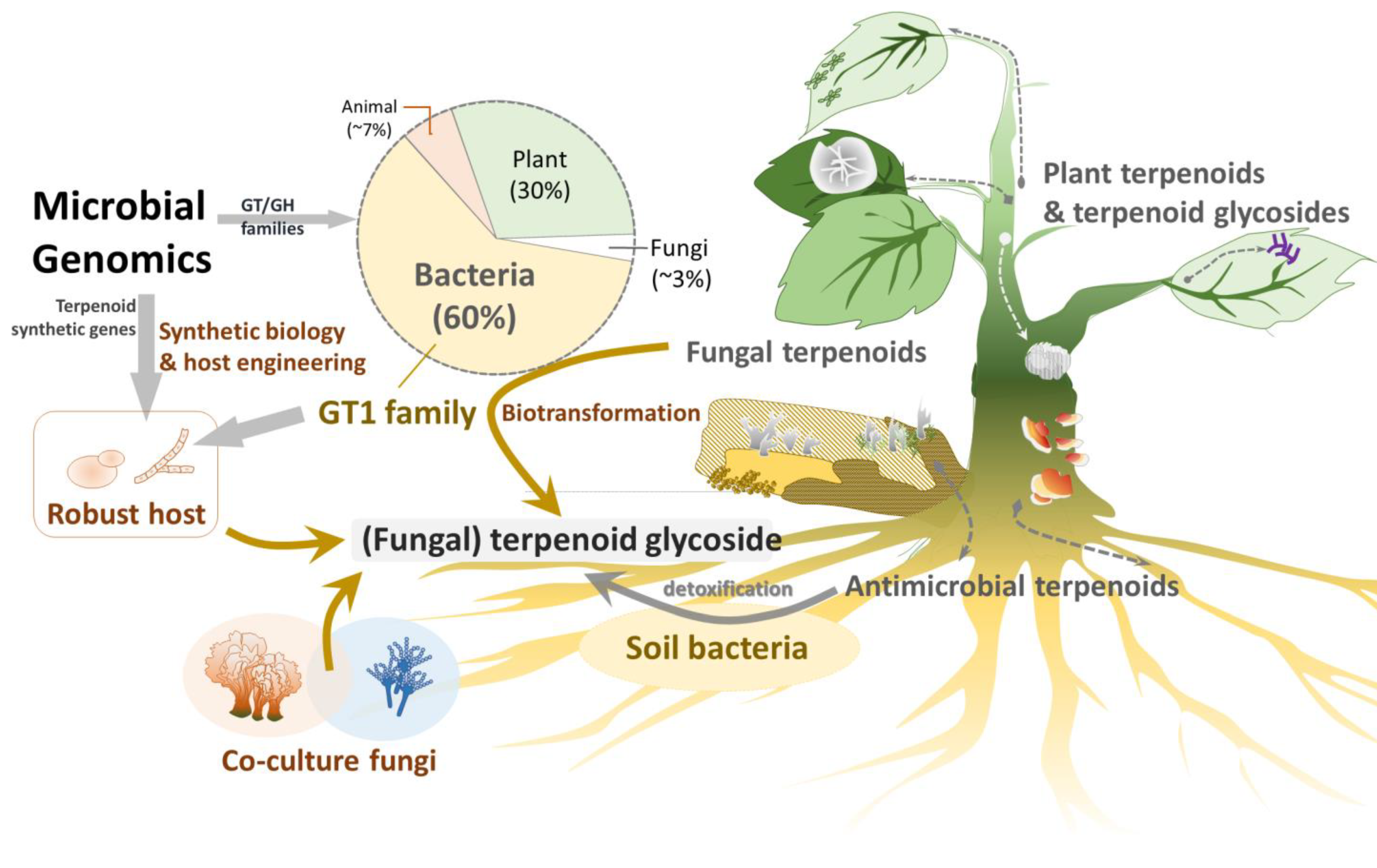

Natural products, such as terpenoids and phenolics, often exhibit significant biological activities, making them valuable for pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical, and nutraceutical applications [

1,

2]. Terpenoids are particularly abundant in plants and fungi [

3,

4,

5]. Although they do not have a direct relationship with plant growth and development, terpenoids serve as important secondary metabolites of plants, are critical for plant–environment interactions, and provide resistance to cold and water shortages and defense against diseases and pests (

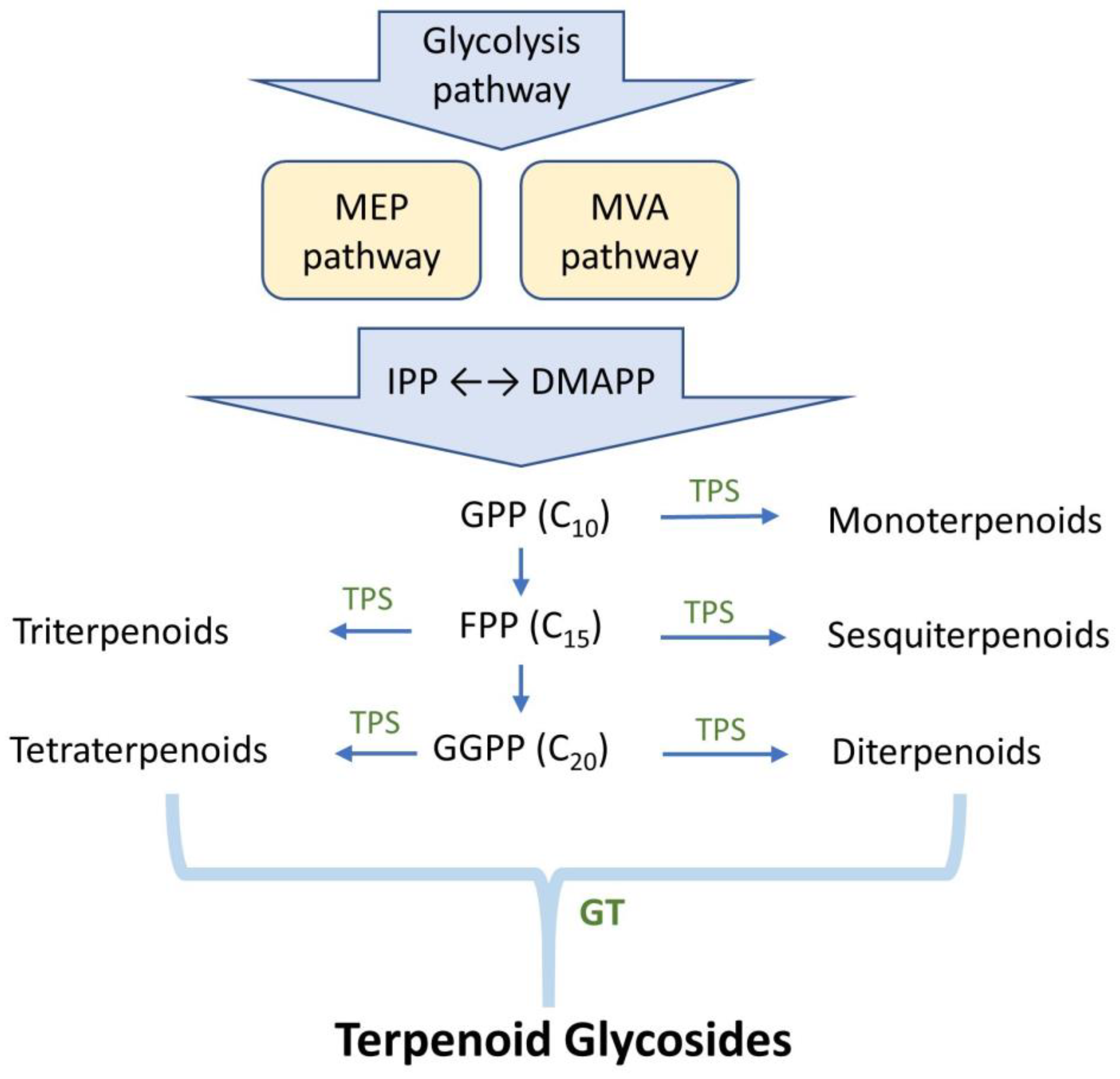

Figure 1).

Based on the number of isoprene units, terpenoids are classified into monoterpenoids (C10), sesquiterpenoids (C15), diterpenoids (C20), sesterterpenoids (C25), triterpenoids (C30), and tetraterpenoids (C40). These diverse terpenoids are synthesized from two universal five-carbon precursors: isopentenyl pyrophosphate and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (

Figure 2) [

6]. In nature, these precursors are synthesized via two upstream biosynthetic pathways: the mevalonate and methylphenidate pathways. Both compounds are ligated in downstream pathways to produce intermediate pyrophosphates, such as geranyl pyrophosphate, farnesyl pyrophosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. These pyrophosphates are then modified via numerous terpene synthases to produce various natural terpenoids [

7]. After formation, some terpenoids are glycosylated by glycosyltransferases (GTs) to form terpenoid glycosides (

Figure 2).

Glycosylation

, the process of covalently attaching a carbohydrate to another molecule, is a common strategy in nature to enhance the solubility, stability, and bioactivity of secondary metabolites. Enzymatic glycosylation, using biocatalysts such as GTs and glycoside hydrolases (GHs), offers several advantages over chemical methods, including high regioselectivity, substrate specificity, and mild reaction conditions. Both GTs and GHs have been applied in the glycosylation of natural products, such as phenolics and plant terpenoids, in recent decades [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This review focuses on recent advances in the enzymatic glycosylation of fungal (

Ganoderma) triterpenoids using bacterial GTs and GHs to produce novel glycosides with potentially improved properties.

Terpenoid glycosides are abundantly found in plants [

22] and many diterpenoid glycosides are also common in animals, such as gorgonian corals [

23]. However, terpenoid glycosides are rarely found in fungi [

5]. For example, the medical fungus genus

Ganoderma contains more than 374 triterpenoids [

24], and

Aspergillus contains more than 288 triterpenoids; however, they have only three triterpenoid glycosides each [

25]. This disparity indicates that fungi may lack specific GTs to form terpenoid glycosides [

26].

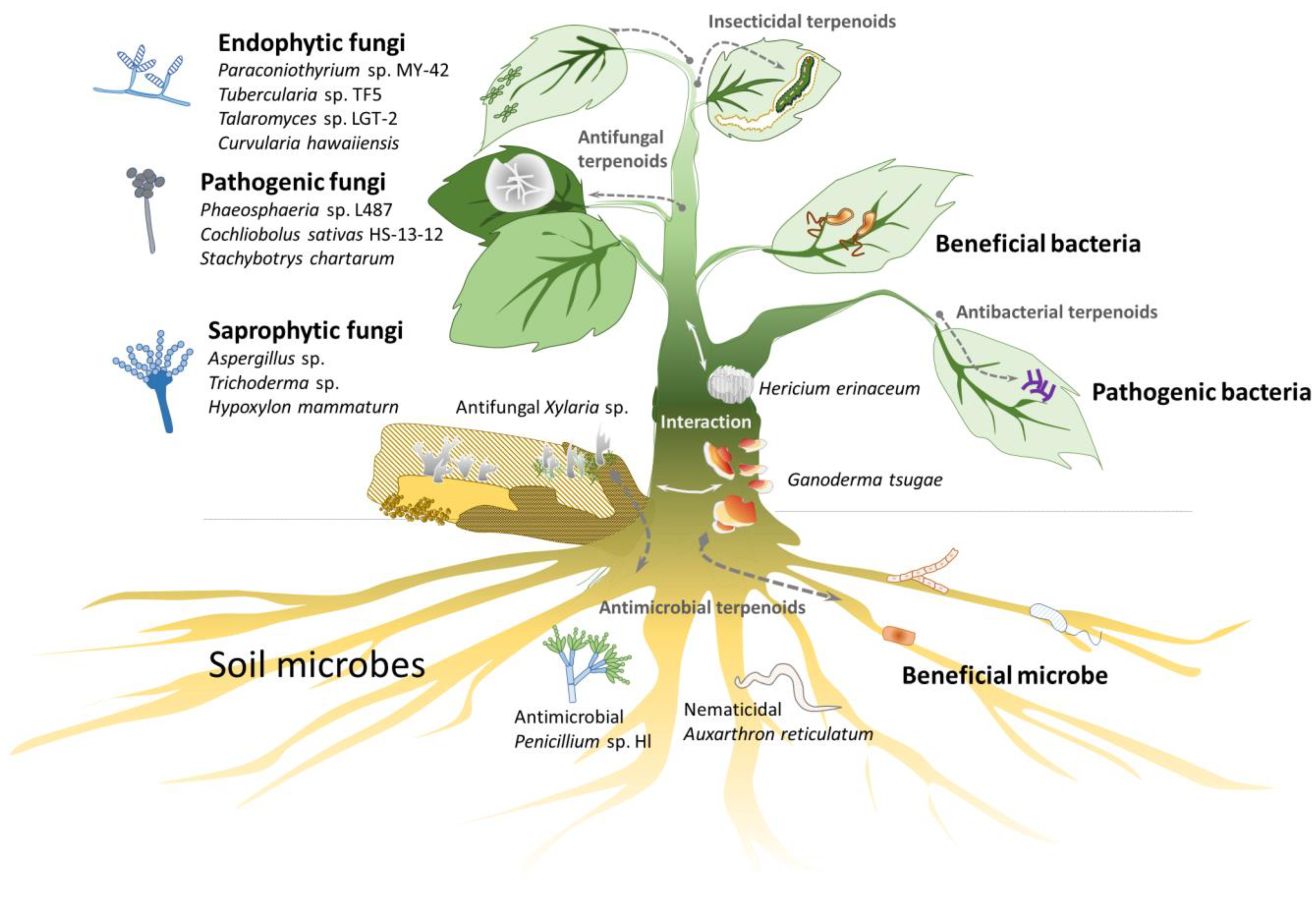

To compete with limited carbon resources (sugars), microbes need to obtain sugars quickly and/or kill other microbes. Plants and fungi produce terpenoids as chemical defenses to kill other microbes or insects [

27]. Homotropic plants have diverse terpenoids and terpenoid glycosides, whereas heterotrophic fungi have some terpenoids and few terpenoid glycosides, likely due to the lack of specific GTs.

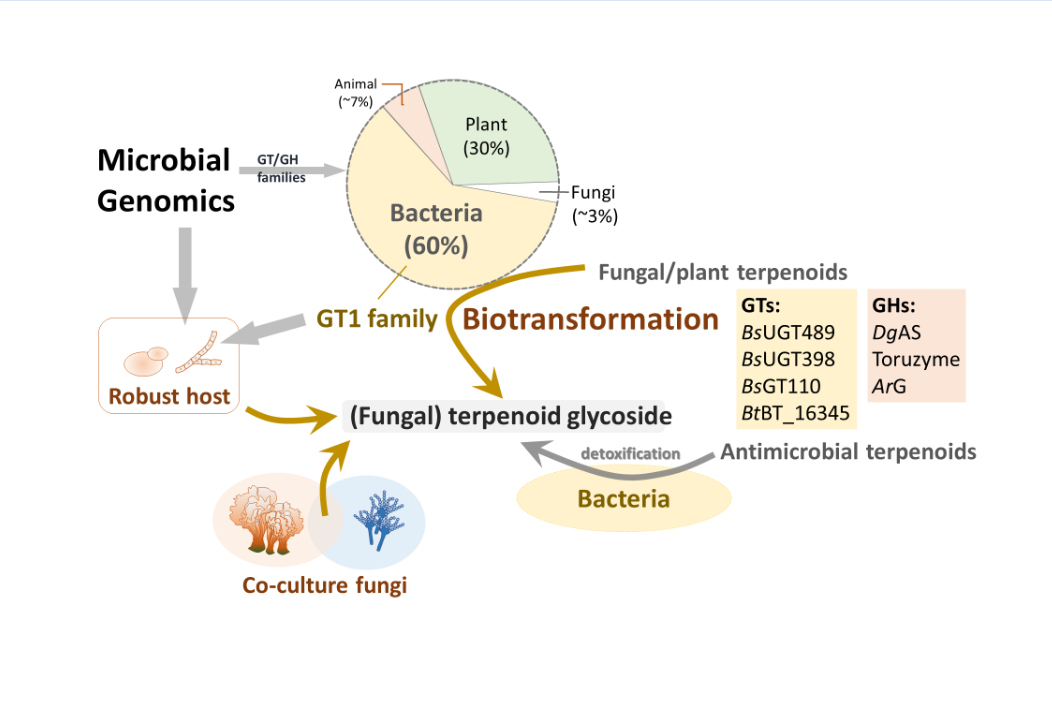

The GT1 family of enzymes plays a key role in terpenoid glycoside production. According to the Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZy) database, over 20,000 GT1 have been identified [

26], with nearly 60% originating from bacteria.

Figure 3.

Strategies for searching for novel terpenoid glycosides. Bacterial GTs may biotransform plant and fungal metabolites into glycosides, such as terpenoids and phenolics, which may alter the activity of the original metabolites in terms of solubility, bioavailability, and detoxification. On the basis of reality, one may recombinase and validate novel GTs or GHs from bacterial genomes or integrate functional gene clusters into suitable hosts. In addition, co-culturing microbes with natural compounds or precursors may also help isolate novel derivativities.

Figure 3.

Strategies for searching for novel terpenoid glycosides. Bacterial GTs may biotransform plant and fungal metabolites into glycosides, such as terpenoids and phenolics, which may alter the activity of the original metabolites in terms of solubility, bioavailability, and detoxification. On the basis of reality, one may recombinase and validate novel GTs or GHs from bacterial genomes or integrate functional gene clusters into suitable hosts. In addition, co-culturing microbes with natural compounds or precursors may also help isolate novel derivativities.

The remaining 30% and approximately 7% originate from plants and animals, respectively [

26]. In contrast, only a few GT1 genes originate from fungi, likely reflecting the paucity of terpenoid glycosides in fungi. On the other hand, GT1 family genes are quite commonly found in bacteria. This may be because the bacteria need the GT1 enzyme to detoxify the antibacterial terpenoids into terpenoid glycosides for survival. Notably, macrolide-producing

Streptomyces lividans glycosylates antibiotics via GT1 enzymes for self-protection [

28]. Recent studies have demonstrated that GT1 enzymes confer resistance to toxic terpenoids by glycosylating them [

29,

30,

31].

There may be two reasons why the heterotrophic fungi lost GT1 family genes and mainly produce terpenoids. First, fungi, competing with plants and microbes for limited sugar (carbon) sources, may have evolutionarily lost terpenoid glycosylation pathways or related metabolisms to conserve energy. This hypothesis is supported by the rarity of glycosylated secondary metabolites, including phenols, terpenes, alkaloids and terpenoids, in fungi [

6,

24,

25,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Second, terpenoid glycosides might be toxic to fungi. Thus, fungi do not waste energy to synthesize these types of toxic compounds. Some terpenoid glycosides possess amphiphilic properties, and the membrane-permeabilizing property induces cell toxicity in advance [

22]. Some plant- and animal-derived terpenoid glycosides exhibit antifungal activity, providing protection from pathogenic fungi [

41]. Notably, a few fungal terpenoid glycosides have been reported to exhibit weak antibacterial activity [

42].

2. Strategies for Producing Novel Terpenoid Glycosides

One approach to increasing terpenoid glycoside production is to cultivate heterotrophic fungi enriched with sugars or to integrate bacterial GT genes into the genomes of terpenoid-producing fungi. The recombinant fungi could then glycosylate cellular terpenoids to produce terpenoid glycosides with functionally expressed GTs. However, if these terpenoid glycosides prove to be toxic to the fungal host, this strategy may not be viable. Alternatively, screening to identify a robust host and integrating related pathway genes are required to mitigate toxicity and produce terpenoid glycosides.

Synthetic biology, encompassing techniques such as metabolic engineering and genome editing, offers solutions for the sustainable and efficient production of high-value plant terpenoids in industrial microbial cell factories,

Escherichia coli and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae [

43,

44,

45]. These genetic tools have been applied to produce various pharmaceutical terpenoids (terpenoid glycosides) on a large scale. However, the biosynthetic pathway genes of fungal terpenoids remain insufficiently understood.

Many studies have described the entire biosynthetic pathways of plant terpenoids or terpenoid glycosides, but knowledge of fungal biosynthetic pathways remains limited. Comparative genomics between closely related fungi with and without terpenoid glycosides may help identify putative biosynthetic pathway genes of fungal terpenoids (terpenoid glycosides), such as GTs responsible for terpenoid glycoside synthesis. For example, Basidiomycete

Hericium erinaceus produces diverse erinacine diterpenoid glycosides [

46]. Recently, a terpenoid biosynthetic gene cluster was identified in

H. erinaceus, comprising 10 synthetic pathway genes (

eriA to

eriJ), including one GT (

eriJ) [

46]. By using a novel knock-in genetic tool to integrate these genes into Ascomycete

Aspergillus oryzae, recombinant

A. oryzae successfully produced erinacine Q diterpenoid glycosides

in vivo [

47].

Furthermore, only small portions of the secondary metabolites have been identified in pure-cultured fungi, suggesting that co-culture systems may be better suited to produce more secondary metabolites, such as fungal terpenoid glycosides, because microbes may compete with limited resources to survive in natural environments. Such interspecific interactions may activate the biosynthesis of unique secondary metabolites. For example,

Xylaria flabelliformis produced an extra secondary metabolite, wheldone, only when co-cultured with

Aspergillus fischeri [

48]. Similarly,

Micromonospora species also produced an extra antibiotic, keyicin, only when co-cultured with a

Rhodococcus species [

49]. Therefore, a co-culturing system is another approach to isolating more terpenoid glycosides.

3. Bacterial GT/GH Enzymes for New Ganoderma Terpenoid Glycosides

Because nearly 60% of GT1 genes originate from bacteria, recombinant bacterial GT1 enzymes could be applied to biotransform valuable but low-soluble terpenoids. A notable example is

Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi mushroom), which has long been used in traditional medicine due to its diverse pharmacological activities [

24]. These activities are largely attributed to its triterpenoid constituents, particularly ganoderic acids (GAs), which exhibit various bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antioxidant effects. However, the poor aqueous solubility, and thus bioavailability, of some GAs limits their clinical application.

Glycosylation is a strategy to overcome these limitations [

50]. There are two glycosylation methods: chemical synthesis and enzymatic biotransformation. The main difficulty with the chemical synthesis of terpenoid glycosides is the lack of regioselectivity of multiple hydroxyl groups in the sugar moiety. In contrast, biotransformation is a promising method because of the regioselective and enantioselective synthesis of bioactive compounds [

13,

18,

20,

51,

52,

53,

54].

Although GT- or GH-mediated glycosylation of natural products (mainly in phenolics) has been reported [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], few terpenoid glycosides have been biotransformed from terpenoids. Therefore, this section highlights GTs or GHs that can generate new terpenoid glycosides from fungal terpenoids through enzymatic biotransformation (

Table 1) and reviews their glycosylation mechanisms (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These enzymatic modifications can enhance solubility, stability, and bioavailability and even alter bioactivity [

50,

55,

56,

57,

58].

3.1. New Terpenoid Glycosides from GT-Catalyzed Biotransformation

GTs (EC 2.4.x.y) catalyze the transfer of sugar moieties from activated donor molecules, typically uridine diphosphate (UDP)-sugars such as UDP glucose (UDP-G), to specific acceptor molecules. The CAZy database classifies GTs into numerous families [

59]. Among these, the GT1 family includes many enzymes that use small molecules, such as flavonoids and terpenes, as sugar acceptors [

26].

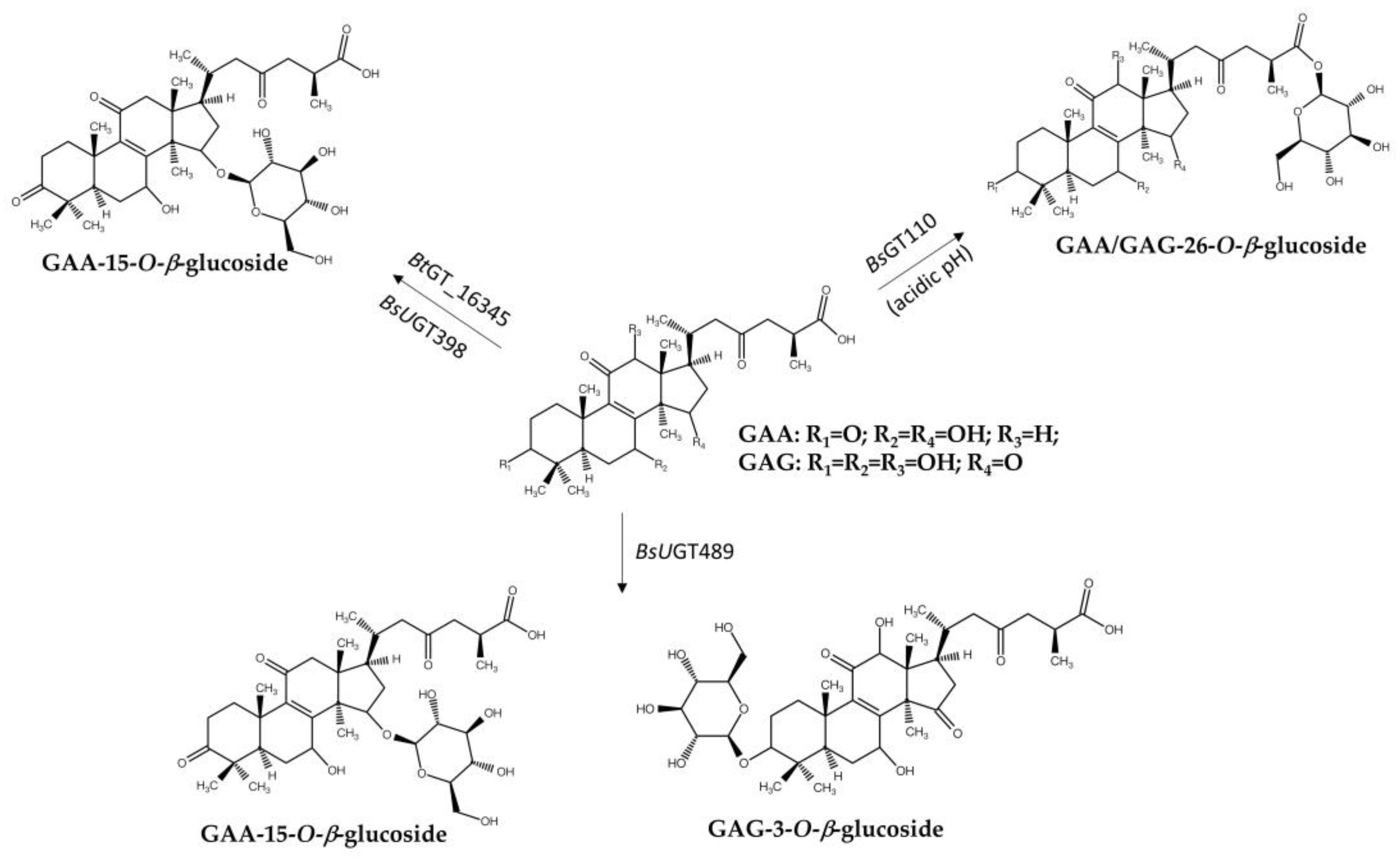

Enzymatic biotransformation is a synthetic method with good bioconversion efficiency. However, the difficulty is finding functional enzymes. One approach for identifying suitable enzymes is to feed the microbes with triterpenoids, check whether they can catalyze the precursors, and then screen for the putative enzymes involved in the biotransformation. For example,

Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 was found to glycosylate ganoderic acid A (GAA), a lanostane triterpenoid from

G. lucidum, and to produce two GAA derivatives: GAA-15-

O-

β-glucoside [

60] and GAA-26-

O-

β-glucoside [

61]. Based on the CAZy database, the GTs, which usually belong to GT family 1 (GT1), are responsible for GAA glycosylation. Thus, nine suitable GT candidates were selected from the whole genome sequence of

B. subtilis ATCC 6633. These candidates were further cloned and overexpressed in

Escherichia coli to produce pure GT enzymes. After functional screening, three GTs—

BsGT110,

BsUGT398, and

BsUGT489—were confirmed to have regioselective glycosylation activity toward GAA (

Figure 4). In addition,

BsGT110 was found to catalyze a novel acidic glycosylation of GAA at the C-26 carboxyl group, producing GAA-26-

O-

β-glucoside.

BsGT110 exhibited optimal activity at pH 6.0 and lost most of its activity at pH 8.0. Kinetic analysis indicated that the catalytic activity of

BsGT110 toward GAA was higher at acidic pH.

BsGT110 was also shown to glycosylate ganoderic acid G (GAG) at the C-26 position. These findings establish

BsGT110 as the first identified GT catalyzing triterpenoid glycosylation at the C-26 carboxyl group under acidic conditions. Moreover,

BsGT110 and

BsUGT489 were also found to glycosylate GAG into GAG-26-

O-

β-glucoside and GAG-3-

O-

β-glucoside, respectively [

62].

Table 1.

Enzymatic synthesis of new Ganoderma terpenoid glycosides.

Table 1.

Enzymatic synthesis of new Ganoderma terpenoid glycosides.

| Enzyme type |

Enzyme |

Precursor |

Product |

Property of the new glycosides |

Illustration |

Reference |

| Glycosyltransferase (GT) |

BsUGT4891,2, BsUGT3981,2, BtBT_163451,3

|

Ganoderic acid A (GAA) |

GAA-15-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 4 |

[60,63,64] |

|

BsGT1101,2

|

GAA |

GAA-26-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 4 |

[61] |

|

BsUGT489 |

Ganoderic acid G (GAG) |

GAG-3-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 4 |

[62] |

|

BsGT110 |

GAG |

GAG-26-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 4 |

[62] |

| Combination of BtBT_16345 and BsGT110 |

GAA |

GAA-15,26-O-β-diglucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 6 |

[65] |

| Glycoside hydrolase (GH) |

Combination of BtBT_16345 and Toruzyme4

|

GAA |

GAA-15-O-[α-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-glucopyranoside] |

Improved solubility |

Figure 6 |

[66] |

| |

DgAS1,5

|

GAA |

Glucosyl-(2→26)-GAA anomers |

Unique anomers |

Figure 5 |

[67] |

| |

DgAS |

GAG |

Glucosyl-(2→26)-GAG anomers |

Unique anomers |

Figure 5 |

[67] |

| |

DgAS |

Ganoderic acid F (GAF) |

Glucosyl-(2→26)-GAF anomers |

Unique anomers |

Figure 5 |

[67] |

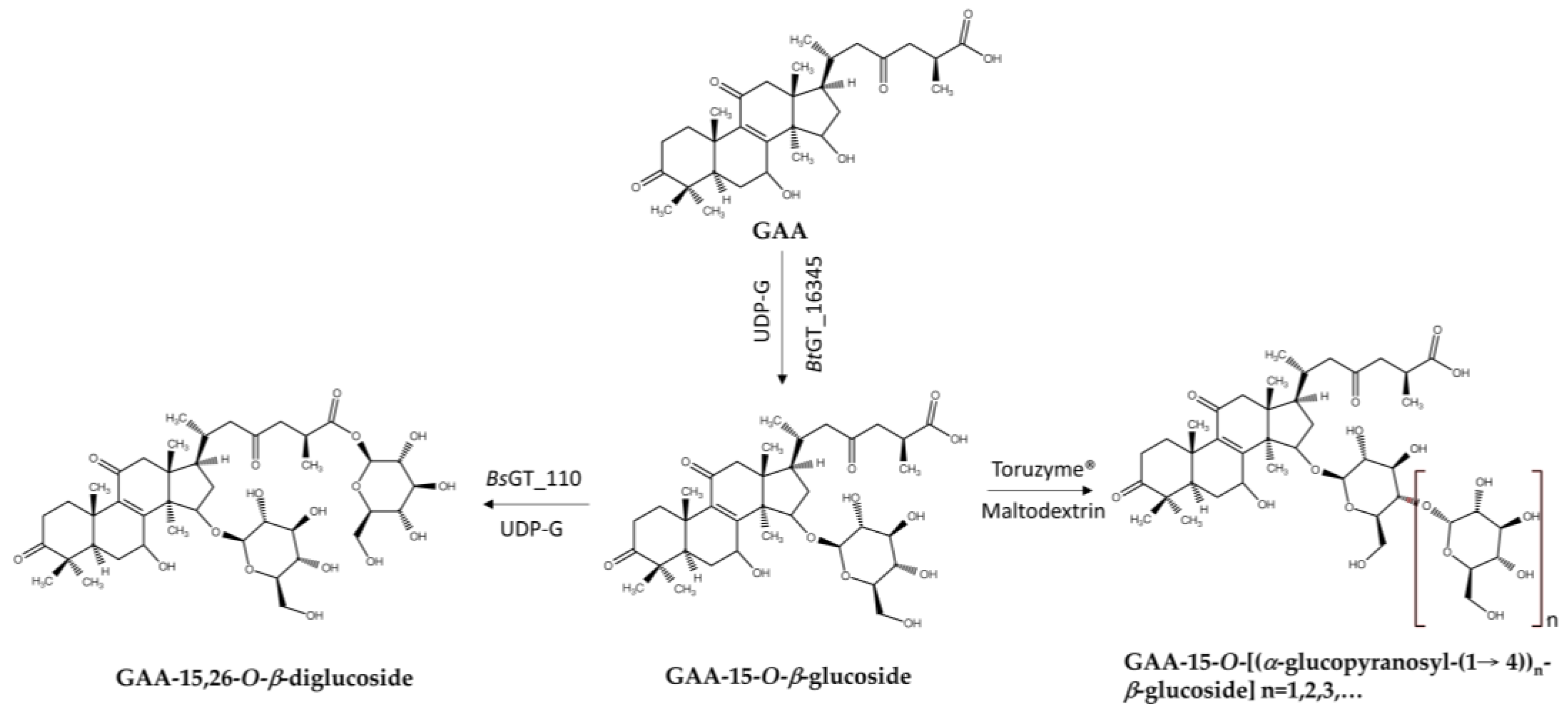

Similarly, an intestinal

Bacillus thuringiensis strain, GA A07, from zebrafish exhibited 10-fold higher efficiency for producing GAA-15-

O-

β-glucoside than

B. subtilis ATCC 6633 [

63]. A genome-centric approach and functional validation revealed a key glycosyltransferase,

BtGT_16345, as the first GT family 28 (GT28) enzyme responsible for regioselective glycosylation on the C-15 hydroxyl group of GAA (

Figure 5). The optimal conditions for

BtGT_16345 activity were determined to be pH 7.5 and 30 °C, with magnesium ions. Unlike

BsUGT398 and

BsUGT489,

BtGT_16345 showed broader substrate specificity, exhibiting glycosylation activity toward several flavonoids and antcin K [

63]. Kinetic studies revealed comparable catalytic efficiencies between

BtGT_16345 and

BsUGT398/

BsUGT489 for GAA glycosylation. Moreover, the highly efficient and highly regioselective glycosylation of

BtGT_16345 toward GAA can be integrated with other GTs to form

in vitro cascade reactions and produce soluble terpenoid oligosaccharides (

Figure 5) [

65]. These terpenoid disaccharides possessed several thousand-fold higher solubilities than their parent terpenoid aglycone, implying promising medical applications.

3.2. New Terpenoid Glycosides from GH-Catalyzed Biotransformation

In nature, terpenoid glycosides are mainly produced by GT catalytic reactions in the presence of a sugar donor, such as UDP-G [

13,

52]. However, the high cost of UDP-G limits large-scale industrial applications. Thus, researchers have tried to find alternative enzymes to glycosylate terpenoid aglycones. Several GH enzymes have been identified to glycosylate flavonoids by using cheaper sugar donors, such as starch, cyclodextrin, sucrose, and maltose [

20,

68]. Although such an affordable biotransformation would be highly useful and scalable, most identified GHs cannot directly glycosylate terpenoid aglycones into terpenoid glycosides [

67]. To date, only one GH—

Deinococcus geothermalis amylosucrase (

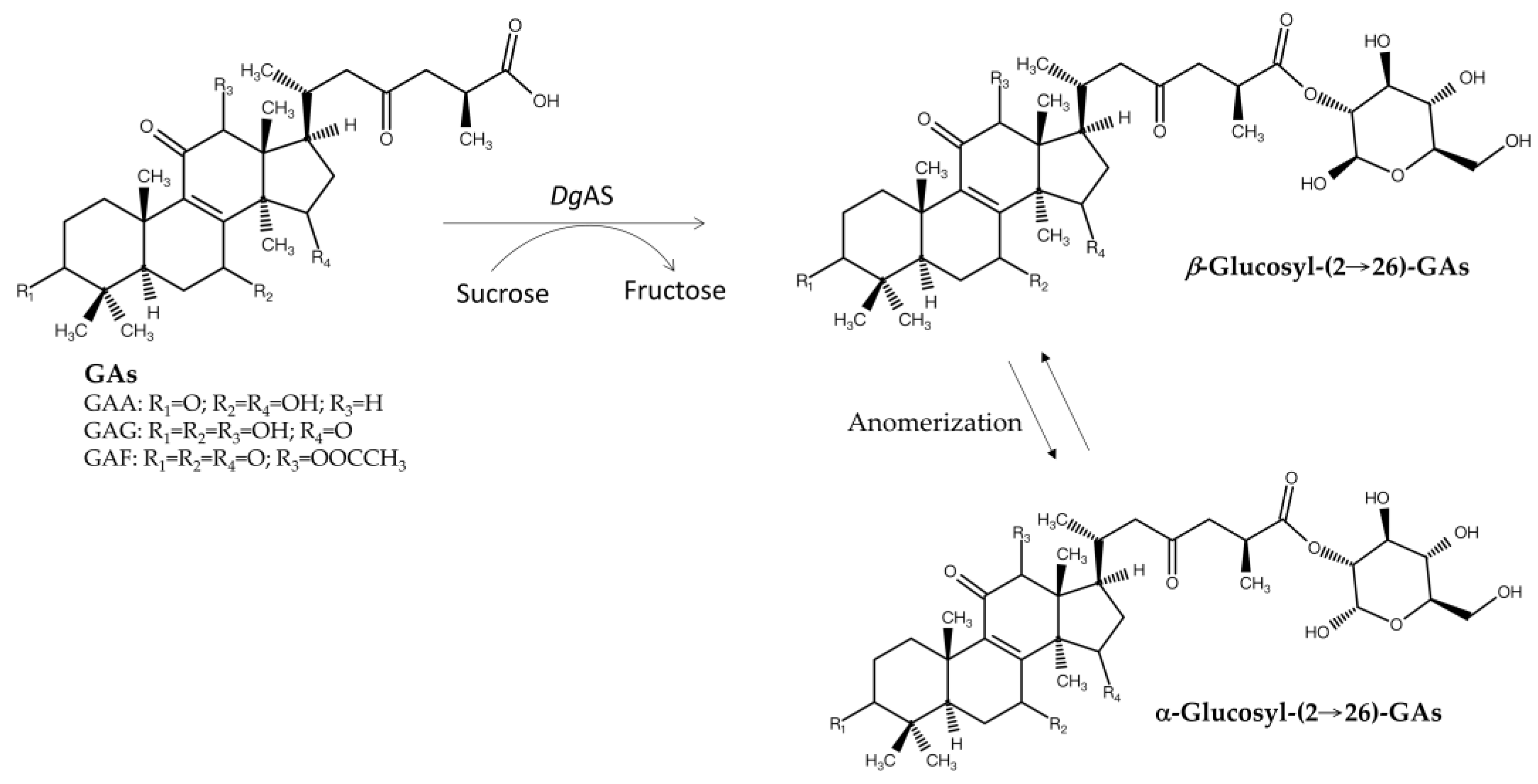

DgAS)—has been reported to glycosylate fungal terpenoid aglycones.

DgAS has been found to glycosylate three triterpenoids from

G. lucidum, namely, GAA, GAG, and ganoderic acid F (GAF), forming glucosyl-(2→26)-GA anomers with sucrose as the sugar donor (

Figure 6) [

67]. This activity was optimal under acidic conditions (pH 5–6) and was significantly reduced at neutral or alkaline pH and produces

α-glucosyl-(2→26)-GAF and

β-glucosyl-(2→26)-GAF anomers in a 3:2 ratio, as confirmed with nuclear magnetic resonance analysis. Similar anomers were also produced with GAA and GAG.

Natural glycosides are linked by glycosidic bonds, in which the linkages usually connect the C-1 bounded anomeric carbon of the glucose donor with the sugar acceptor molecules; therefore, either α- or β-glycosides are formed. However, DgAS causes glycosylation at the C-2 position, with C-1 remaining free and thus anomerizing in solutions, producing both α- and β-glycosides of triterpenoid aglycones. Although unknown, the proposed mechanism involves a carbon switch, leading to a novel glycosidic linkage. The bioactivity and biological implications of these GA glycoside anomers remain unknown.

Another GH13 enzyme, cyclodextrin glucanotransferase (CGTase, Toruzyme 3.0 L), was used in a sequential biotransformation strategy (

Figure 5) [

66]. In a one-pot reaction, GAA was first glycosylated at the C-15 position by

BtGT_16345 to produce GAA-15-

O-

β-glucopyranoside (GAA-15-G). Subsequently, Toruzyme catalyzed the glycosylation of GAA-15-G using maltose, yielding several GAA glucosides: GAA-G2, GAA-G3, and GAA-G4. The major product, GAA-15-

O-[α-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-

β-glucopyranoside] (GAA-G2), exhibited a significantly higher aqueous solubility (>4500-fold) than GAA. Toruzyme showed specificity toward GAA-15-G, as it did not directly glycosylate GAA. The enzyme catalyzed the α-(1→4) glycosylation linkage, which is consistent with previous studies on flavonoid and steroidal saponin glycosylation [

69,

70,

71]. This demonstrated the potential of combining GTs and GHs to synthesize triterpenoid saponins with improved properties.

Figure 6.

Biotransformation of three ganoderic acids into glycosides by DgAS [

67].

Figure 6.

Biotransformation of three ganoderic acids into glycosides by DgAS [

67].

4. Bacterial GTs/GHs Applied to Other Natural Compound Derivatives

Glycosylation improves solubility [

55,

56,

58,

65,

72,

73], bioavailability [

50], and detoxification [

74,

75] of molecules, making it a valuable strategy for modifying natural products. Over the past few decades, GTs and GHs have been widely applied in glycosylating various natural products, including phenolic compounds [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. As mentioned, bacterial GTs and GHs can glycosylate

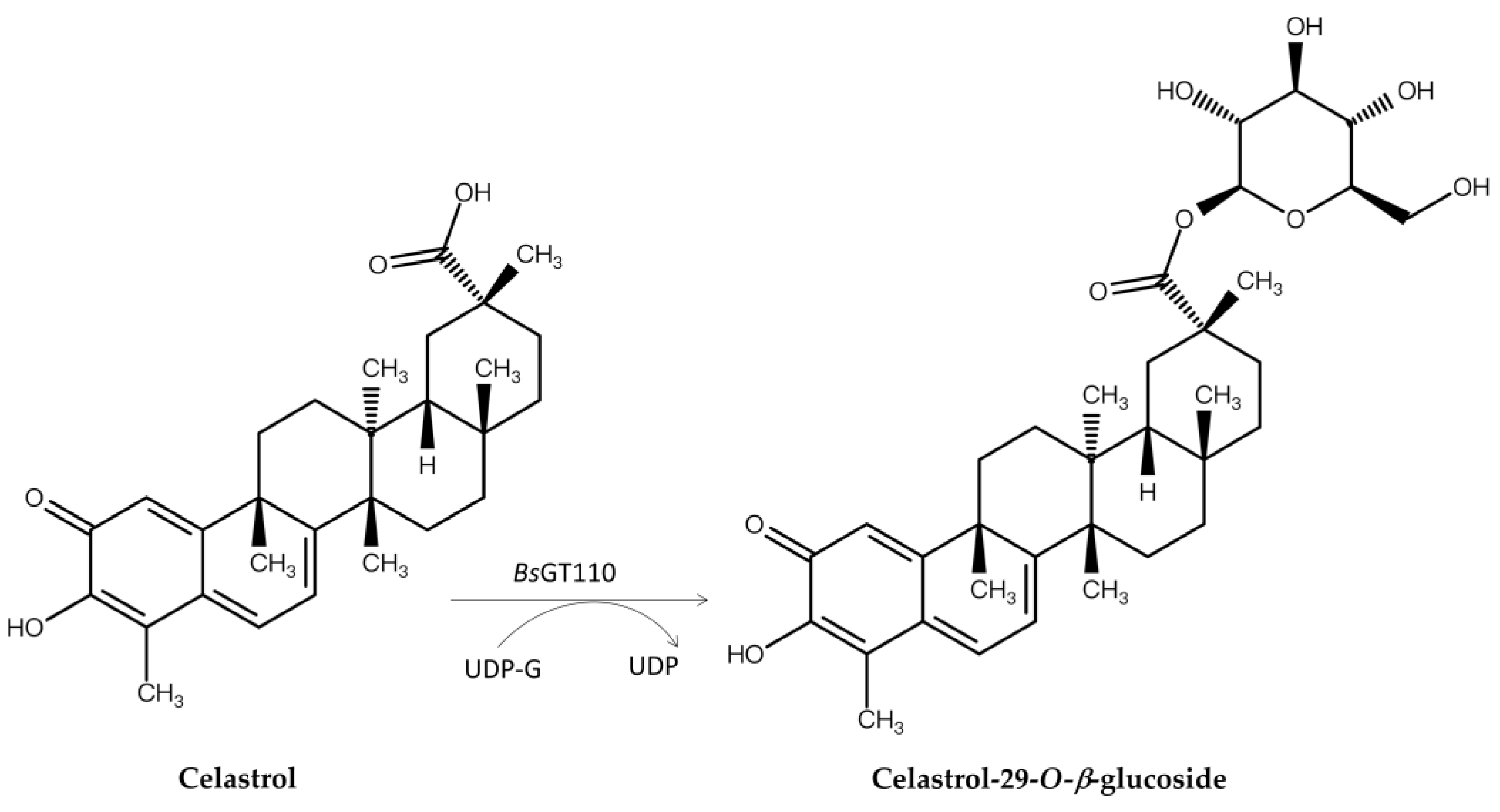

Ganoderma triterpenoids to produce new terpenoid glycosides with better solubility but lower bioactivity. These bacterial enzymes might also reduce the toxicity of terpenoids. To explore this potential, these recombinant enzymes were applied to celastrol (

Figure 7), a pentacyclic triterpenoid isolated from the root of the plant

Tripterygium wilfordii that not only has high toxicity, resulting in a narrow therapeutic window, but also possesses many useful bioactivities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, anticancer, antiobesity, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory effects [

55]. Moreover, its low water solubility restricts its oral bioavailability, further hindering its clinical application.

BsGT110 considerably mitigated these limitations by glycosylating celastrol to the highly soluble celastrol-29-

O-

β-glucoside at pH 8, which also displayed lower toxicity than celastrol (

Figure 7). This example underscores the advantages, and thus increased pharmaceutical applicability, of bacterial enzymatic glycosylation (

Table 1 and

Table 2) in improving water solubility and reducing the toxicity of compounds such as celastrol [

76,

77].

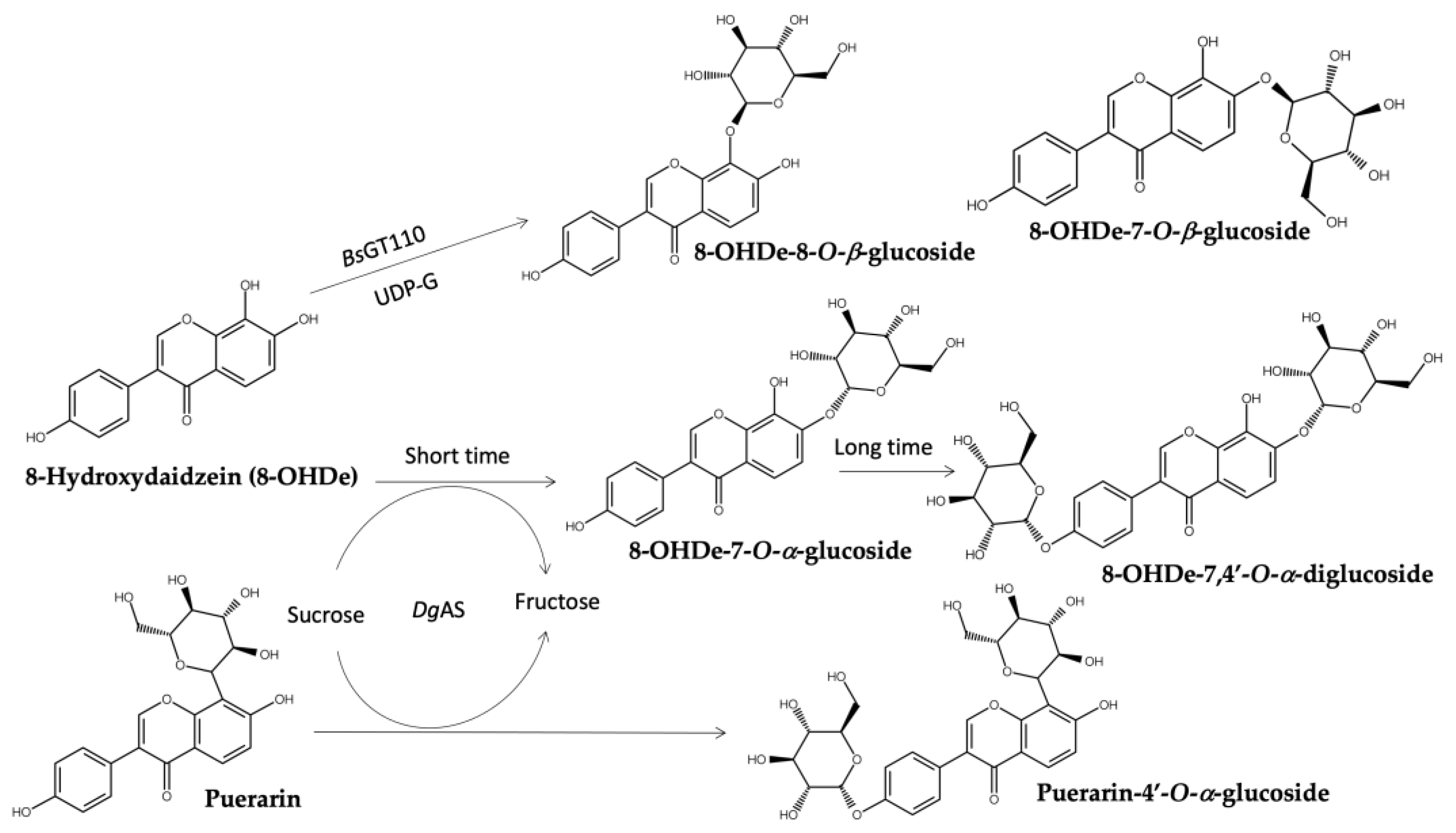

In addition to triterpenoid glycosylation,

BsGT110 also catalyzed the glycosylation of soybean isoflavone 8-hydroxydaidzein (8-OHDe) (

Figure 8) [

78] into two new isoflavone glucosides, 8-OHDe-7-

O-

β-glucoside and 8-OHDe-8-

O-

β-glucoside, which have significantly higher aqueous solubility (9.0-fold and 4.9-fold, respectively) and improved stability than 8-OHDe. Notably,

BsGT110 demonstrated acidic glycosylation activity toward

Ganoderma triterpenoid GAA at pH 6 [

61] but showed optimal glycosylation toward celastrol at pH 8 and isoflavonoid 8-OHDe at pH 7. Thus, the same enzyme showed different optimal reaction conditions toward different substrates, suggesting the importance of identifying optimal reaction conditions for different substrates in future studies on enzymatic synthesis.

DgAS, a GH, glycosylates 8-OHDe into

α-glucosides, 8-OHDe-7-

O-

α-glucopyranoside (8-OHDe-7-G), with a short reaction time [

57]. However, prolonged reaction time led to the formation of two additional diglucoside derivatives, indicating

DgAS’s broad regioselectivity in forming glycosidic linkages (

Figure 8) [

79]. The resulting glucosides also exhibited enhanced solubility and stability.

DgAS was also employed for the glycosylation of puerarin, an isoflavone with limited solubility and similar structure to 8-OHDe (

Figure 8) [

80]. Unlike other GTs and GHs,

DgAS glycosylated the 4′-hydroxyl group of puerarin, producing a novel glycoside with improved solubility. This regioselectivity distinguishes it from previously studied GHs, which typically glycosylate the C-glucoside residue of puerarin.

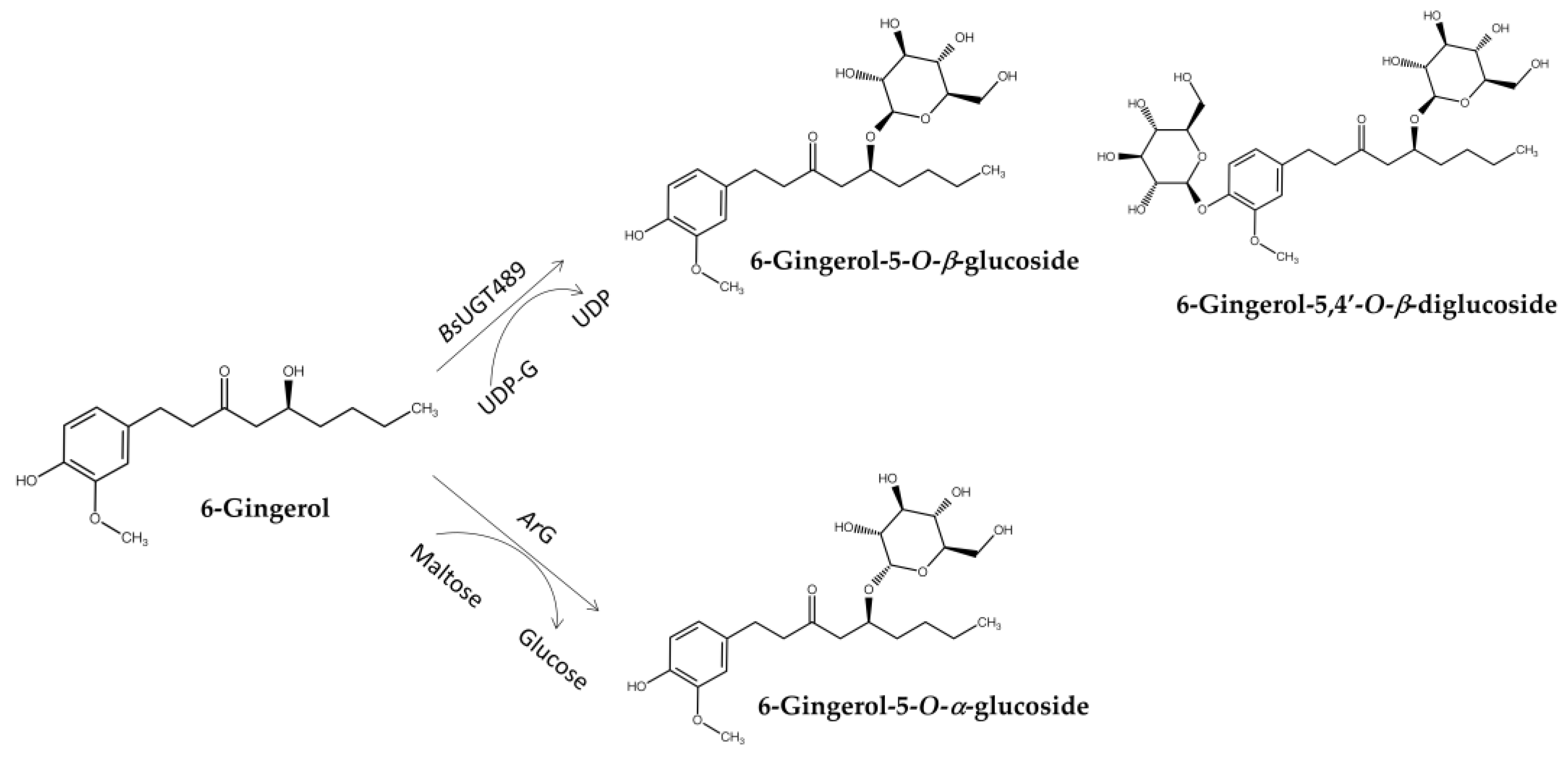

BsUGT489 was identified as a suitable GT for the biotransformation of 6-gingerol through glycosylation into several products, namely 6-gingerol-4′,5-

O-β-diglucoside, 6-gingerol-4′-

O-

β-glucoside, and 6-gingerol-5-

O-β-glucoside (

Figure 9) [

81]. These glucosides greatly improved aqueous solubility compared with 6-gingerol. In addition, spontaneous deglucosylation of some 6-gingerol glucosides led to the formation of 6-shogaol derivatives, thereby highlighting the complex interplay between glycosylation and stability. Compared with GTs, another GH, an

α-glucosidase from

Agrobacterium radiobacter DSM 30147 (

ArG), was found to catalyze the

α-glycosylation of 6-gingerol to produce 6-gingerol-5-

O-

α-glucoside, which possessed 10-fold higher anti-inflammatory activity than 6-gingerol (

Figure 9) [

73].

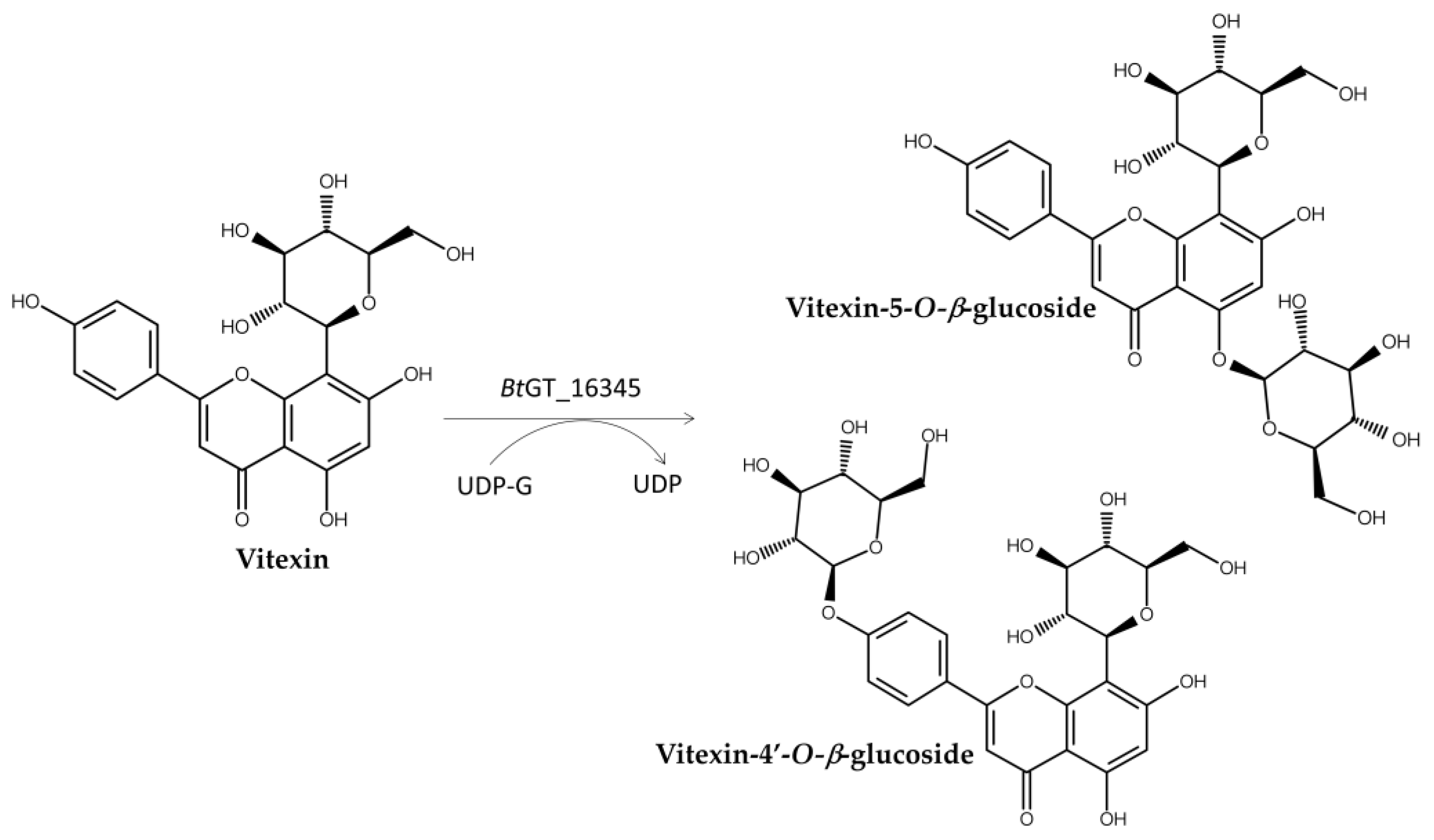

The newly identified GT28 enzyme,

BsGT_16345, catalyzed the glycosylation of vitexin, a C-glucoside flavone with low solubility, to produce vitexin-4′-

O-

β-glucoside and vitexin-5-

O-

β-glucoside, both of which displayed greater aqueous solubility than vitexin (

Figure 10) [

82].

5. Conclusions

The enzymatic glycosylation of natural products using bacterial GTs and GHs has emerged as a powerful strategy for improving their physicochemical properties, particularly aqueous solubility and stability, and potentially enhancing their bioactivity. GTs offer high regioselectivity and typically produce β-glucosides using activated sugar donors, such as UDP-G. In contrast, some GHs, such as amylosucrase and maltogenic amylase, can use more cost-effective sugar donors, such as sucrose and starch, to catalyze transglycosylation reactions, facilitating the production of α-glucosides.

Table 2.

Enzymatic glycosylation of plant precursors by glycosyltransferases (GTs) and glycoside hydrolases (GHs).

Table 2.

Enzymatic glycosylation of plant precursors by glycosyltransferases (GTs) and glycoside hydrolases (GHs).

| Enzyme type |

Enzyme name |

Precursor |

Product |

Property of the new glycosides |

Illustration |

Reference |

| GT |

BsGT1101,2

|

Celastrol |

Celastrol-29-O-β-glucoside |

Detoxification |

Figure 7 |

[55] |

|

BsGT110 |

8-Hydroxydaidzein(8-OHDe) |

8-OHDe-7-O-β-glucoside8-OHDe-8-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility and stability |

Figure 8 |

[78] |

|

BsUGT4891,2

|

6-Gingerol |

6-Gingerol-5-O-β-glucoside6-Gingerol-5,4’-O-β-diglucoside |

Improved solubility and anti-inflammatory activity |

Figure 9 |

[81] |

|

BtBT_163451,3

|

Vitexin |

Vitexin-5-O-β-glucosideVitexin-4’-O-β-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 10 |

[82] |

| GH |

DgAS1,5

|

8-OHDe |

8-OHDe-7-O-α-glucoside8-OHDe-7,4’-O-α-diglucoside |

Improved solubility and stability |

Figure 8 |

[57,79] |

| |

DgAS |

Puerarin |

Puerarin-4’-O-α-glucoside |

Improved solubility |

Figure 8 |

[80] |

| |

ArG |

6-Gingerol |

6-Gingerol-5-O-α-glucoside |

Improved stability and anti-inflammatory activity |

Figure 9 |

[73] |

The enzymatic glycosylation of Ganoderma triterpenoids has proven to be promising for synthesizing novel bioactive compounds with improved characteristics. Bacterial GTs, particularly from Bacillus species, exhibit high regioselectivity, catalyzing the O-glycosylation of ganoderic acids at specific hydroxyl (C-15) and carboxyl (C-26) groups using UDP glucose as a sugar donor. The identification of enzymes such as BsUGT398, BsUGT489, BtGT_16345, and BsGT110 has significantly advanced the modification of these valuable natural products. Furthermore, the application of GHs, such as DgAS and Toruzyme, introduces novel possibilities. DgAS demonstrates a unique ability to form both α- and β-anomers with a nonanomeric carbon linkage to the C-26 carboxyl group, expanding the structural diversity of Ganoderma triterpenoid glycosides. The sequential use of GTs and GHs, as demonstrated by BtGT_16345 and Toruzyme, presents a powerful strategy for producing triterpenoid saponins with significantly enhanced aqueous solubility.

Beyond Ganoderma triterpenoids, the glycosylation of phenolic compounds, including 8-OHDe, vitexin, puerarin, mangiferin, corylin, and gingerols, demonstrates the versatility of GTs and GHs in modifying numerous natural compounds. The resulting glycosides often exhibit significantly enhanced aqueous solubility, which is a critical factor in their bioavailability and industry application.

Investigating the bioactivity of fungal terpenoid glycosides is a developing field. Exploration of microbial genomes could uncover new GTs or GHs and terpenoid biosynthetic pathway genes that could be applied to produce non-natural terpenoid glycosides. Additionally, terpenoid biosynthetic pathway genes could be engineered into microorganisms, such as Ganoderma or new hosts, to produce additional terpenoid glycosides. Moreover, fungal co-culture systems might also stimulate the discovery of more natural terpenoid glycosides.

Future studies should identify and engineer novel GTs and GHs with improved catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, and tolerance to reaction conditions. Exploring the regioselectivity of these enzymes and developing methods for controlling the degree of glycosylation are also key areas of investigation. Furthermore, in-depth studies on the bioactivity and bioavailability of newly synthesized glucosides are crucial to fully realizing their potential applications in pharmaceuticals, cosmeceuticals, and other fields. The application of computational tools and predictive methods can aid in the selection of suitable enzyme–substrate pairs and the design of novel glycosylated natural products with desired properties. The continued exploration of enzymatic glycosylation promises to unlock the full potential of natural products for various biomedical and industrial applications.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.-Y.W., T.-S.C.; project administration: T.-S.C. and J.-Y.W.; writing—original draft, review, and editing: T.-S.C., T.-Y.W., J.-Y.W. and H.-Y.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under grant number MOST 111-2221-E-024 -001-MY3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekiert, H.M.; Szopa, A. Biological activities of natural products. Molecules 2020, 25, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couillaud, J.; Leydet, L.; Duquesne, K.; Iacazio, G. The terpene mini-path, a new promising alternative for terpenoids bio-production. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncan, D.A.T.; Tsang, S.S.K.; Li, C.; Lee, I.H.T.; Lam, H.M.; Chan, T.F.; Hui, J.H.L. Terpenes and terpenoids in plants: interactions with environment and insects. International Journal of Molecular Science 2020, 21, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, J.J.; Vieira, I.J.; Rodrigues-Filho, E.; Braz-Filho, R. Terpenoids from endophytic fungi. Molecules 2011, 16, 10604–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, P.; Wang, L.; Fang, S. Biosynthesis and regulation of terpenoids from basidiomycetes: exploration of new research. AMB Express 2021, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tholl, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: a mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant Journal 2011, 66, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.N.; Wang, R.F.; Zhao, S.J.; Wang, Z.T. Advance in glycosyltransferases, the important bioparts for production of diversified ginsenosides. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines 2020, 18, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yao, M.; Wang, Y.; Ding, M.; Zha, J.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, Y. Advances in engineering UDP-sugar supply for recombinant biosynthesis of glycosides in microbes. Biotechnology Advances 2020, 41, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Yang, S.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Cha, M.N.; Ahn, J.H. Biosynthesis and production of glycosylated flavonoids in Escherichia coli: current state and perspectives. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2015, 99, 2979–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Barton, C.D.; Zhan, J. Engineered production of bioactive polyphenolic O-glycosides. Biotechnology Advances 2023, 65, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overwin, H.; Wray, V.; Seeger, M.; Sepulveda-Boza, S.; Hofer, B. Flavanone and isoflavone glucosylation by non-Leloir glycosyltransferases. Journal of Biotechnology 2016, 233, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrudulakumari Vasudevan, U.; Lee, E.Y. Flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyketide antibiotics: Role of glycosylation and biocatalytic tactics in engineering glycosylation. Biotechnology Advances 2020, 41, 107550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulis, C.; Andre, I.; Remaud-Simeon, M. GH13 amylosucrases and GH70 branching sucrases, atypical enzymes in their respective families. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 2661–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nidetzky, B.; Gutmann, A.; Zhong, C. Leloir Glycosyltransferases as Biocatalysts for Chemical Production. ACS Catalysis 2018, 8, 6283–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrom, L.; Przypis, M.; Kowalczykiewicz, D.; Pollender, A.; Kumpf, A.; Marsden, S.R.; Bento, I.; Jarzebski, A.B.; Szymanska, K.; Chrusciel, A.; et al. Leloir glycosyltransferases in applied biocatalysis: a multidisciplinary approach. International Journal of Molecular Science 2019, 20, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Guang, C.; Mu, W. Amylosucrase as a transglucosylation tool: From molecular features to bioengineering applications. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Gonzalez, A.; Nunez-Lopez, G.; Morel, S.; Amaya-Delgado, L.; Sandoval, G.; Gschaedler, A.; Remaud-Simeon, M.; Arrizon, J. Functionalization of natural compounds by enzymatic fructosylation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2017, 101, 5223–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulis, C.; Guieysse, D.; Morel, S.; Severac, E.; Remaud-Simeon, M. Natural and engineered transglycosylases: Green tools for the enzyme-based synthesis of glycoproducts. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2021, 61, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamova, K.; Kapesova, J.; Valentova, K. "Sweet flavonoids": glycosidase-catalyzed modifications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Xia, G.; Zang, H. Synthesis, alpha-glucosidase inhibition and molecular docking studies of tyrosol derivatives. Natural Product Research 2021, 35, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Khan, Z.; Amin, S.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Mubarak, M.S.; Hadda, T.B.; Maione, F. Plant bioactive molecules bearing glycosides as lead compounds for the treatment of fungal infection: A review. Biomedical Pharmacotherapy 2017, 93, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrue, F.; McCulloch, M.W.; Kerr, R.G. Marine diterpene glycosides. Bioorganic Medicine and Chemistry 2011, 19, 6702–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Zhu, D.; Yang, G.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mao, X.; et al. A comprehensive review of the structure elucidation and biological activity of triterpenoids from Ganoderma spp. Molecules 2014, 19, 17478–17535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.Y.; Yi, J.; Chang, Y.B.; Sun, C.P.; Ma, X.C. Recent studies on terpenoids in Aspergillus fungi: Chemical diversity, biosynthesis, and bioactivity. Phytochemistry 2022, 193, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Glycosyltransferase GT1 family: Phylogenetic distribution, substrates coverage, and representative structural features. Computional and Structrucral Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Raguso, R.A. Why do plants produce so many terpenoid compounds? New Phytologist Foundation 2018, 220, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: enzymatic degradation and modification. Advanced Drug Delivery Review 2005, 57, 1451–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairullina, A.; Tsardakas Renhuldt, N.; Wiesenberger, G.; Bentzer, J.; Collinge, D.B.; Adam, G.; Bulow, L. Identification and functional characterisation of two oat UDP-glucosyltransferases involved in deoxynivalenol detoxification. Toxins (Basel) 2022, 14, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Gala, V.; Dato, L.; Wiesenberger, G.; Jæger, D.; Adam, G.; Hansen, J.; Welner, D.H. Plant-derived UDP-glycosyltransferases for glycosylation-mediated detoxification of deoxynivalenol: enzyme discovery, characterization, and in vivo resistance assessment. Toxins 2025, 17, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, Y.; Chang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sang, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, M.; et al. The silkworm (Bombyx mori) gut microbiota is involved in metabolic detoxification by glucosylation of plant toxins. Communication Biology 2023, 6, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadamuro, R.D.; da Silveira Bastos, I.M.A.; Silva, I.T.; da Cruz, A.C.C.; Robl, D.; Sandjo, L.P.; Alves, S., Jr.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rodriguez-Lazaro, D.; Treichel, H.; et al. Bioactive compounds from mangrove endophytic fungus and their uses for microorganism control. Journal of Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.A.; Zhu, H.J.; Cao, F. Marine fungal metabolites as a source of drug leads against aquatic pathogens. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022, 106, 3337–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, S.K.; Dufosse, L.; Chhipa, H.; Saxena, S.; Mahajan, G.B.; Gupta, M.K. Fungal endophytes: A potential source of antibacterial compounds. Journal of Fungi (Basel) 2022, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hridoy, M.; Gorapi, M.Z.H.; Noor, S.; Chowdhury, N.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Muscari, I.; Masia, F.; Adorisio, S.; Delfino, D.V.; Mazid, M.A. Putative anticancer compounds from plant-derived endophytic aungi: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, R.; Kannappan, A.; Shi, C.; Lin, X. Marine bacterial secondary metabolites: A treasure house for structurally unique and effective antimicrobial compounds. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganyi, M.C.; Ateba, C.N. Untapped potentials of endophytic fungi: A review of novel bioactive compounds with biological applications. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wu, Z.; Guo, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, S. A review of terpenes from marine-derived fungi: 2015-2019. Marine Drugs 2020, 18, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Hermosa, G.C.; Sun, A.-C.; Wu, C.-W.K.; Gao, M.-T.; Wu, C.; David Wang, H.-M. Monacolin-K loaded MIL-100(Fe) metal–organic framework induces ferroptosis on metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-H.; Lin, R.-H.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Shih, P.-K.; Show, P.L.; Chen, H.-Y.; Nakmee, P.S.; Chang, J.-J.; Huang, D.-M.; Wang, H.-M.D. A biomimetic micropillar wound dressing with flavone and polyphenol control release in vitro and in vivo. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2024, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Shao, X.; Zhu, D.; Yu, B. Chemical synthesis of marine saponins. Natural Product Reports 2019, 36, 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.P.; Miao, F.P.; Liu, X.H.; Yin, X.L.; Ji, N.Y. Seven chromanoid norbisabolane derivatives from the marine-alga-endophytic fungus Trichoderma asperellum A-YMD-9-2. Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Wang, Q.; Dai, Z. Metabolic engineering of Yarrowia lipolytica for terpenoids production: advances and perspectives. Critical Review in Biotechnology 2022, 42, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, L.R.; Shi, T.Q.; Sun, X.M.; Huang, H. Advanced strategies for the synthesis of terpenoids in Yarrowia lipolytica. Journal of Agricutural and Food Chemistry 2021, 69, 2367–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.C.; Pakrasi, H.B. Engineering cyanobacteria for production of terpenoids. Planta 2019, 249, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, S.; Ma, K.; Xu, Y.; Tao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, S.; Ren, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Discovery and characterization of a new family of diterpene cyclases in bacteria and fungi. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 2017, 56, 4749–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Minami, A.; Ozaki, T.; Wu, J.; Kawagishi, H.; Maruyama, J.I.; Oikawa, H. Efficient reconstitution of basidiomycota diterpene erinacine gene cluster in ascomycota host Aspergillus oryzae based on genomic DNA sequences. Journal of American Chemistry Society 2019, 141, 15519–15523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.L.; Raja, H.A.; Isawi, I.H.; Flores-Bocanegra, L.; Reggio, P.H.; Pearce, C.J.; Burdette, J.E.; Rokas, A.; Oberlies, N.H. Wheldone: Characterization of a unique scaffold from the coculture of Aspergillus fischeri and Xylaria flabelliformis. Organic Letters 2020, 22, 1878–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnani, N.; Chevrette, M.G.; Adibhatla, S.N.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Q.; Braun, D.R.; Nelson, J.; Simpkins, S.W.; McDonald, B.R.; Myers, C.L.; et al. Coculture of marine invertebrate-associated bacteria and interdisciplinary technologies enable biosynthesis and discovery of a new antibiotic, keyicin. ACS Chemical Biology 2017, 12, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Xie, Y. Improvement strategies for the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble flavonoids: An overview. International Journal of Pharmacy 2019, 570, 118642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahawi, S.I.; Shaaban, K.A.; Kharel, M.K.; Thorson, J.S. A comprehensive review of glycosylated bacterial natural products. Chemical Society Review 2015, 44, 7591–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas, F.; Parra, A.; Martinez, A.; Garcia-Granados, A. Enzymatic glycosylation of terpenoids. Phytochemistry Reviews 2013, 12, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Dhar, Y.V.; Asif, M.H.; Misra, P. Exploring the functional significance of sterol glycosyltransferase enzymes. Progress on Lipid Research 2018, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Yoo, S.H.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, Y.R.; Park, C.S. Versatile biotechnological applications of amylosucrase, a novel glucosyltransferase. Food Science and Biotechnology 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Chiang, C.M.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, H.L.; Wu, Y.W.; Ting, H.J.; Wu, J.Y. Biotransformation of celastrol to a novel, well-soluble, low-toxic and anti-oxidative celastrol-29-O-beta-glucoside by Bacillus glycosyltransferases. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2021, 131, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Ting, H.-J.; Chang, T.-S. Improving aqueous solubility of natural antioxidant mangiferin through glycosylation by maltogenic amylase from Parageobacillus galactosidasius DSM 18751. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Kao, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Chiang, C.M. Potential industrial production of a well-soluble, alkaline-stable, and anti-inflammatory isoflavone glucoside from 8-hydroxydaidzein glucosylated by recombinant amylosucrase of Deinococcus geothermalis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Tayo, L.L.; Suratos, K.S.; Tsai, P.W.; Wang, T.Y.; Fong, Y.N.; Ting, H.J. Predictive production of a new highly soluble glucoside, corylin-7-O-beta-glucoside with potent anti-inflammatory and anti-melanoma activities. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, D490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Wu, K.Y.; Chiang, C.M. Uridine diphosphate-dependent glycosyltransferases from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 catalyze the 15-O-glycosylation of ganoderic acid A. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Chiang, C.M.; Kao, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Wang, T.Y. A new triterpenoid glucoside from a novel acidic glycosylation of ganoderic acid A via recombinant glycosyltransferase of Bacillus subtilis. Molecules 2019, 24, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Chang, T.S. Glycosylation of ganoderic acid G by Bacillus glycosyltransferases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 9744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Hsueh, T.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Chuang, H.M.; Cai, W.X.; Wu, J.Y.; Chiang, C.M.; Wu, Y.W. A genome-centric approach reveals a novel glycosyltransferase from the GA A07 strain of Bacillus thuringiensis responsible for catalyzing 15-O-glycosylation of ganoderic acid A. International Journal Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.S.; Chiang, C.M.; Wang, T.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, Y.W.; Wu, J.Y. New Triterpenoid from Novel Triterpenoid 15-O-Glycosylation on Ganoderic Acid A by Intestinal Bacteria of Zebrafish. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S.; Chiang, C.-M.; Wu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Ting, H.-J. Production of a new triterpenoid disaccharide saponin from sequential glycosylation of ganoderic acid A by 2 Bacillus glycosyltransferases. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2021, 85, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S.; Chiang, C.-M.; Wang, T.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-W.; Ting, H.-J.; Wu, J.-Y. One-pot bi-enzymatic cascade synthesis of novel Ganoderma triterpenoid saponins. Catalysts 2021, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Luo, S.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Tsai, Y.L.; Chang, T.S. Novel glycosylation by amylosucrase to produce glycoside anomers. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Guang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Glycosylation of flavonoids by sucrose- and starch-utilizing glycoside hydrolases: A practical approach to enhance glycodiversification. Critical Review on Food Scienes and Nutrition 2023, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.B.; Feng, B.; Huang, H.Z.; Qin, Y.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Kang, L.P.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.N.; Cai, Y.; Tan, D.W.; et al. Enzymatic synthesis of alpha-glucosyl-timosaponin BII catalyzed by the extremely thermophilic enzyme: Toruzyme 3.0L. Carbohydrate Research 2010, 345, 1752–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.S.; Lee, H.J.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, D.U.; Lee, D.Y.; Min, J.W.; Jimenez, Z.; Yang, D.C. Synthesis of a novel alpha-glucosyl ginsenoside F1 by cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and its in vitro cosmetic applications. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Alfonso, J.L.; Rodrigo-Frutos, D.; Belmonte-Reche, E.; Penalver, P.; Poveda, A.; Jimenez-Barbero, J.; Ballesteros, A.O.; Hirose, Y.; Polaina, J.; Morales, J.C.; et al. Enzymatic synthesis of a novel pterostilbene alpha-glucoside by the combination of cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and amyloglucosidase. Molecules 2018, 23, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Lin, S.Y.; Chang, T.S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel vitexin glucosides. Molecules 2021, 26, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Wu, J.Y.; Ding, H.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y. Exploring gingerol glucosides with enhanced anti-inflammatory activity through a newly identified alpha-glucosidase (ArG) from Agrobacterium radiobacter DSM 30147. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2024, 138, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova, R.; Busscher, J.; Schempp, F.M.; Buchhaupt, M.; van Dijk, A.D.J.; Beekwilder, J. Detoxification of monoterpenes by a family of plant glycosyltransferases. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppenberger, B.; Berthiller, F.; Lucyshyn, D.; Sieberer, T.; Schuhmacher, R.; Krska, R.; Kuchler, K.; Glossl, J.; Luschnig, C.; Adam, G. Detoxification of the fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol by a UDP-glucosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 47905–47914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.Y.; Ong, P.S.; Wang, L.; Goel, A.; Ding, L.; Li-Ann Wong, A.; Ho, P.C.; Sethi, G.; Xiang, X.; Goh, B.C. Celastrol in cancer therapy: Recent developments, challenges and prospects. Cancer Letters 2021, 521, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xie, F.; Wang, L.; Zhu, G.; Qi, L.W.; Jiang, S. Celastrol: an update on its hepatoprotective properties and the linked molecular mechanisms. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 857956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-M.; Wang, T.-Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chang, T.-S. Production of new isoflavone glucosides from glycosylation of 8-hydroxydaidzein by glycosyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633. Catalysts 2018, 8, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-M.; Wang, T.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, T.-S. Production of new isoflavone diglucosides from glycosylation of 8-hydroxydaidzein by Deinococcus geothermalis amylosucrase. Fermentation 2021, 7, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Chang, T.-S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel and highly soluble puerarin glucoside by Deinococcus geothermalis amylosucrase. Molecules 2022, 27, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.S.; Ding, H.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Wang, T.Y. Glycosylation of 6-gingerol and unusual spontaneous deglucosylation of two novel intermediates to form 6- shogaol-4′-O-β-glucoside by bacterial glycosyltransferase. Applied Enviromental Microbiology 2024, 9, e0077924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Ding, H.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, T.-S. Enzymatic synthesis of novel vitexin glucosides. Molecules 2021, 26, 6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).