Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction:

2. Materials and Method:

3. Result and Discussion:

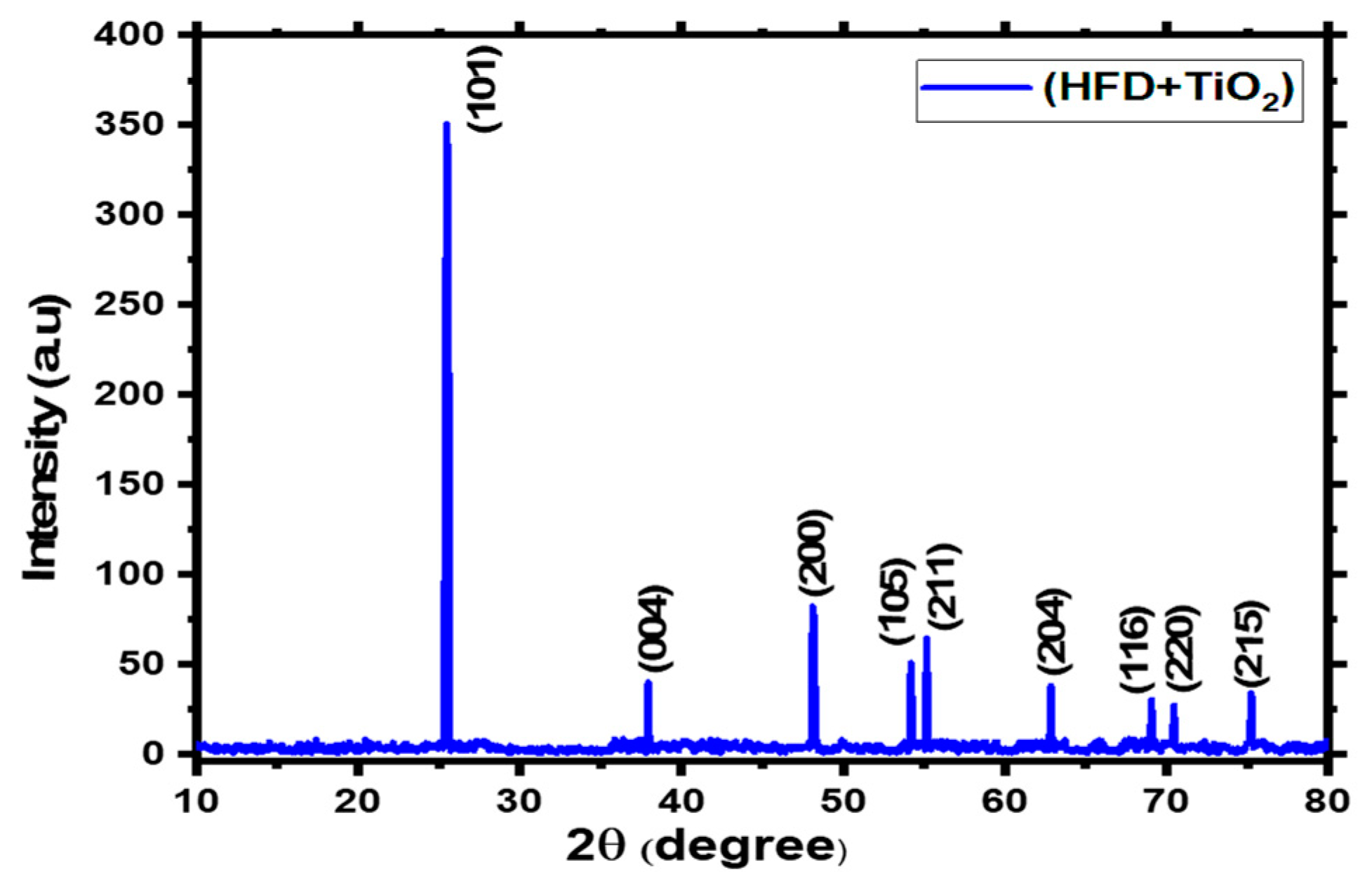

3.1 Xrd Analysis:

| Sample | FWHM Value | Crystallite size (nm) |

Dislocation density (Ꟙ) ( 1014) |

Microstrain ( 10−4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFD + TiO2 | 0.21424 | 40.12 | 6.24 | 9.03 |

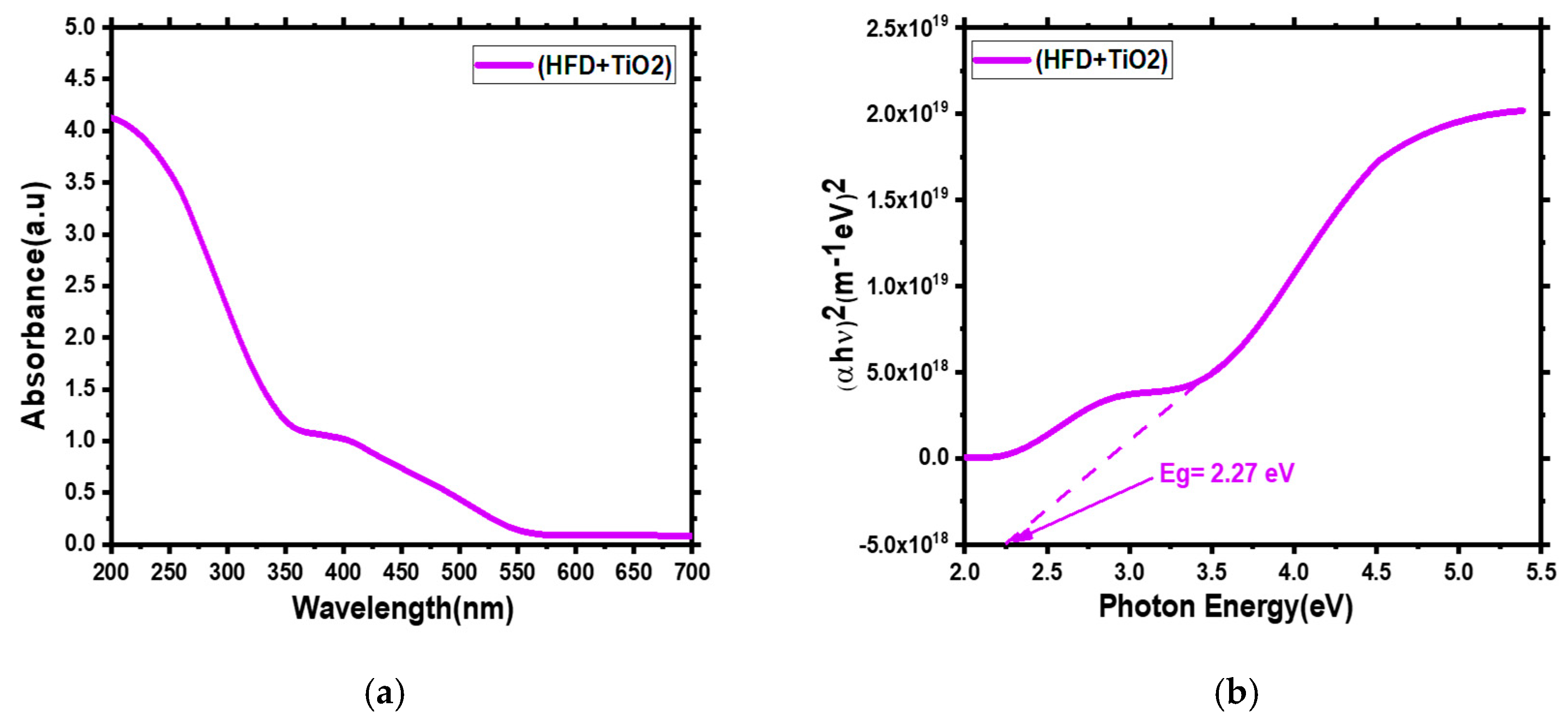

3.2. UV Visible Analysis:

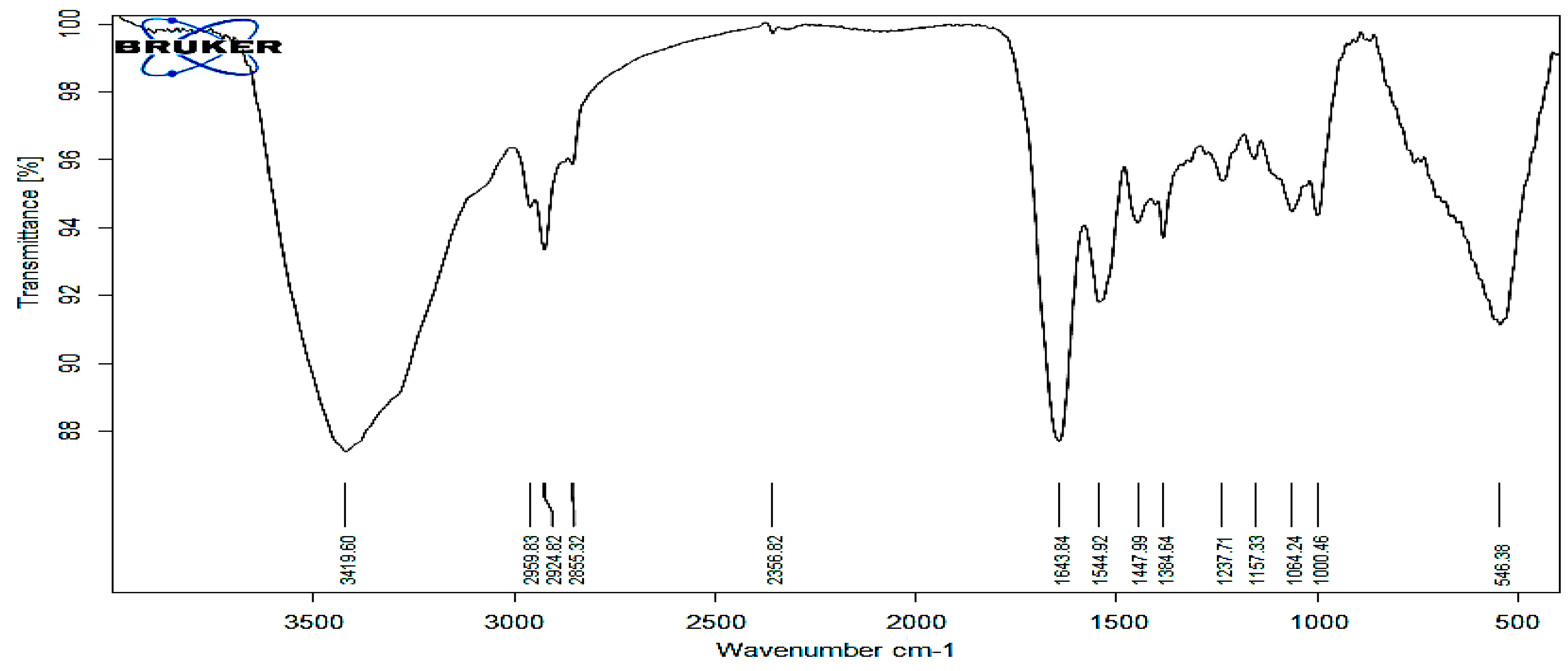

3.3. Ftir Analys:

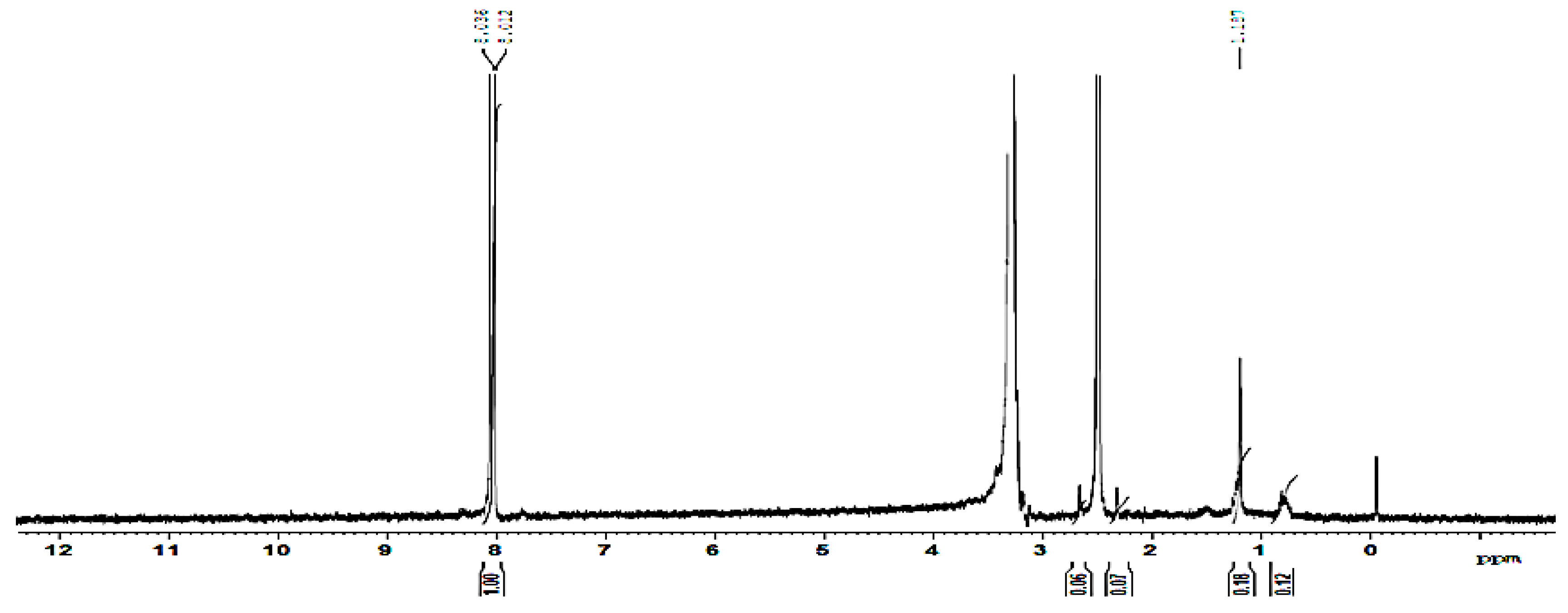

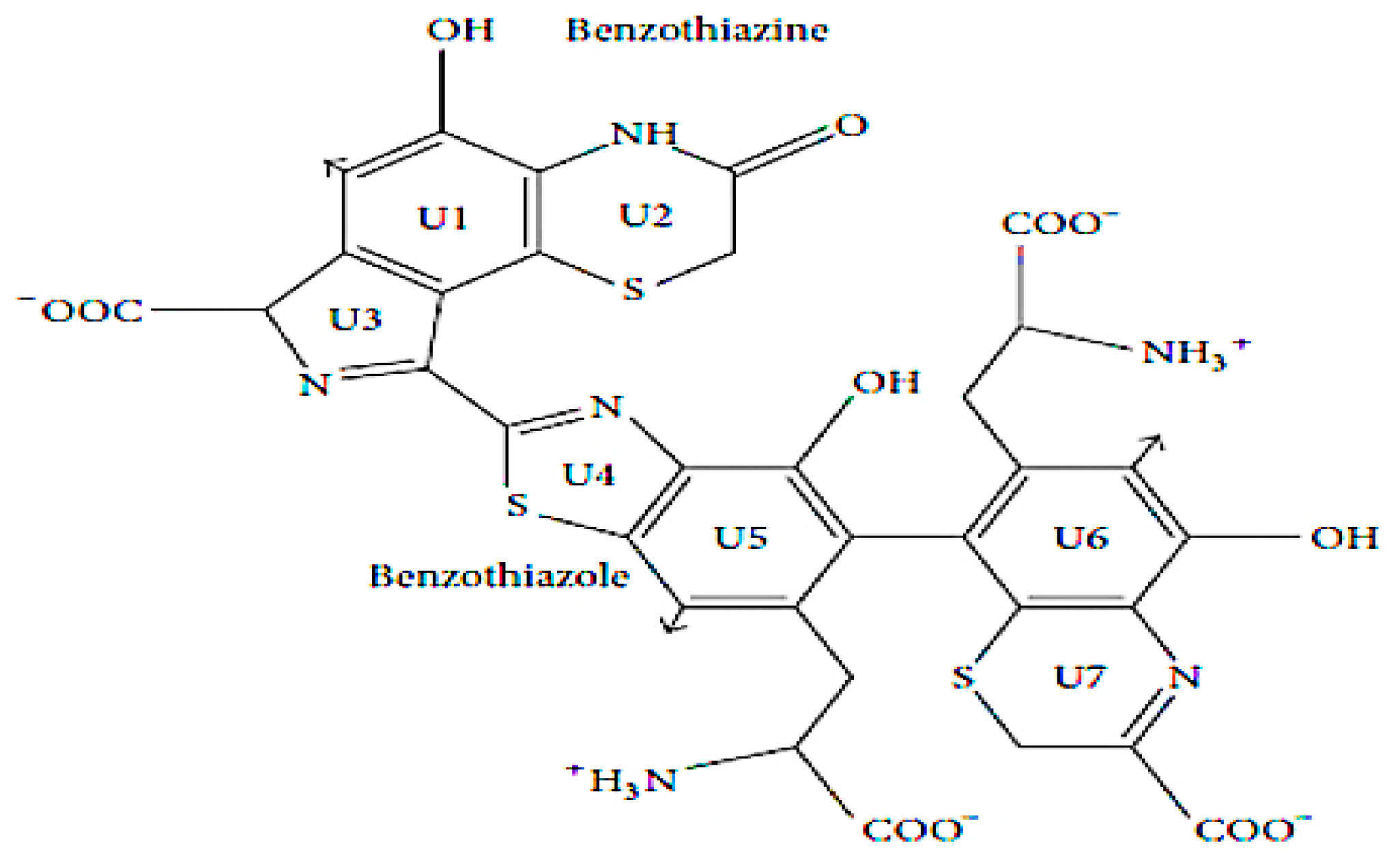

3.4. NMR Analysis:

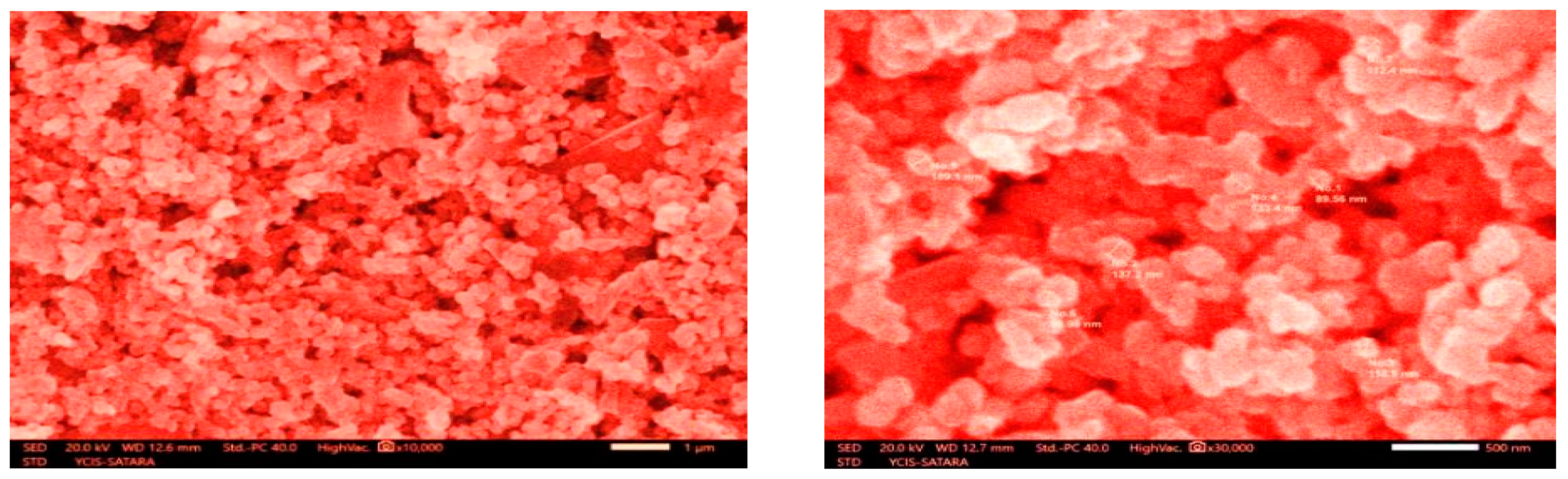

3.5. SEM Analysis:

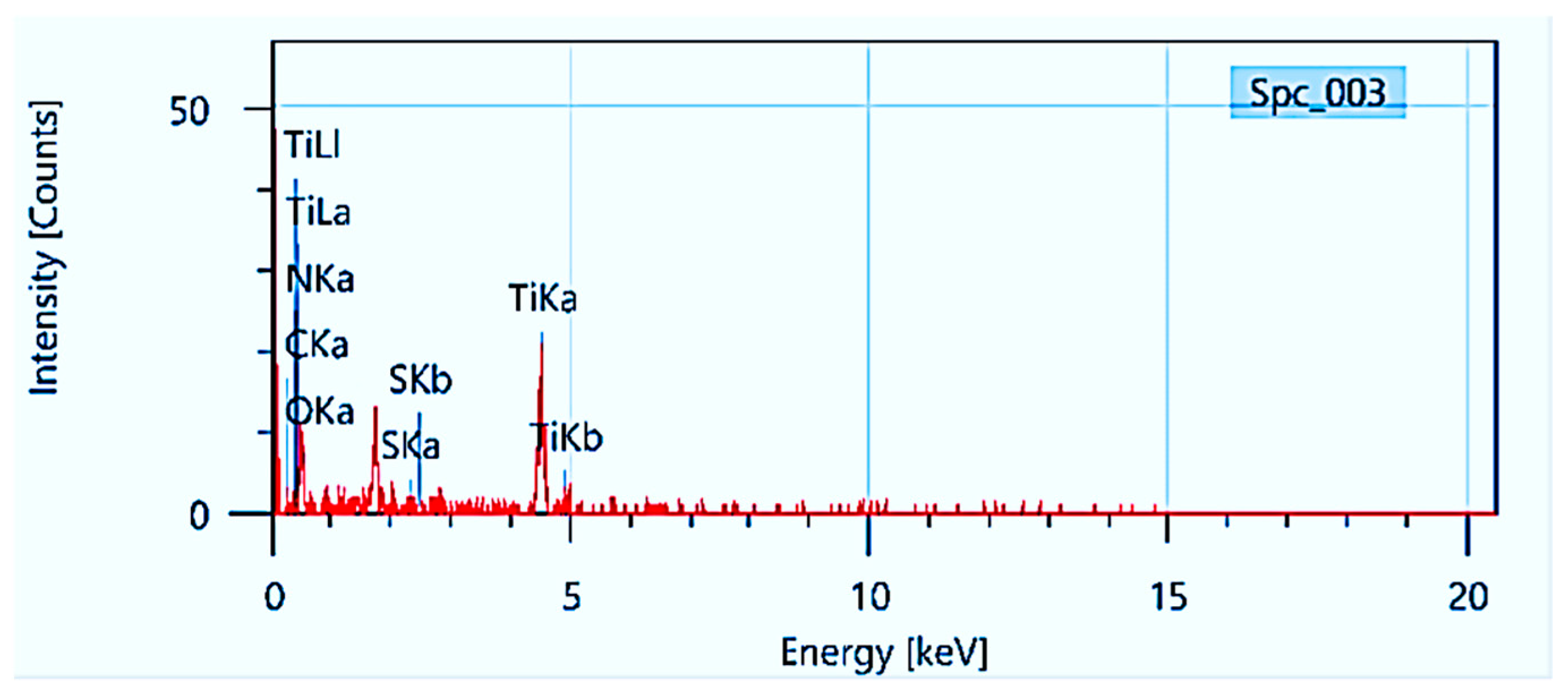

3.6. EDAX Analysis:

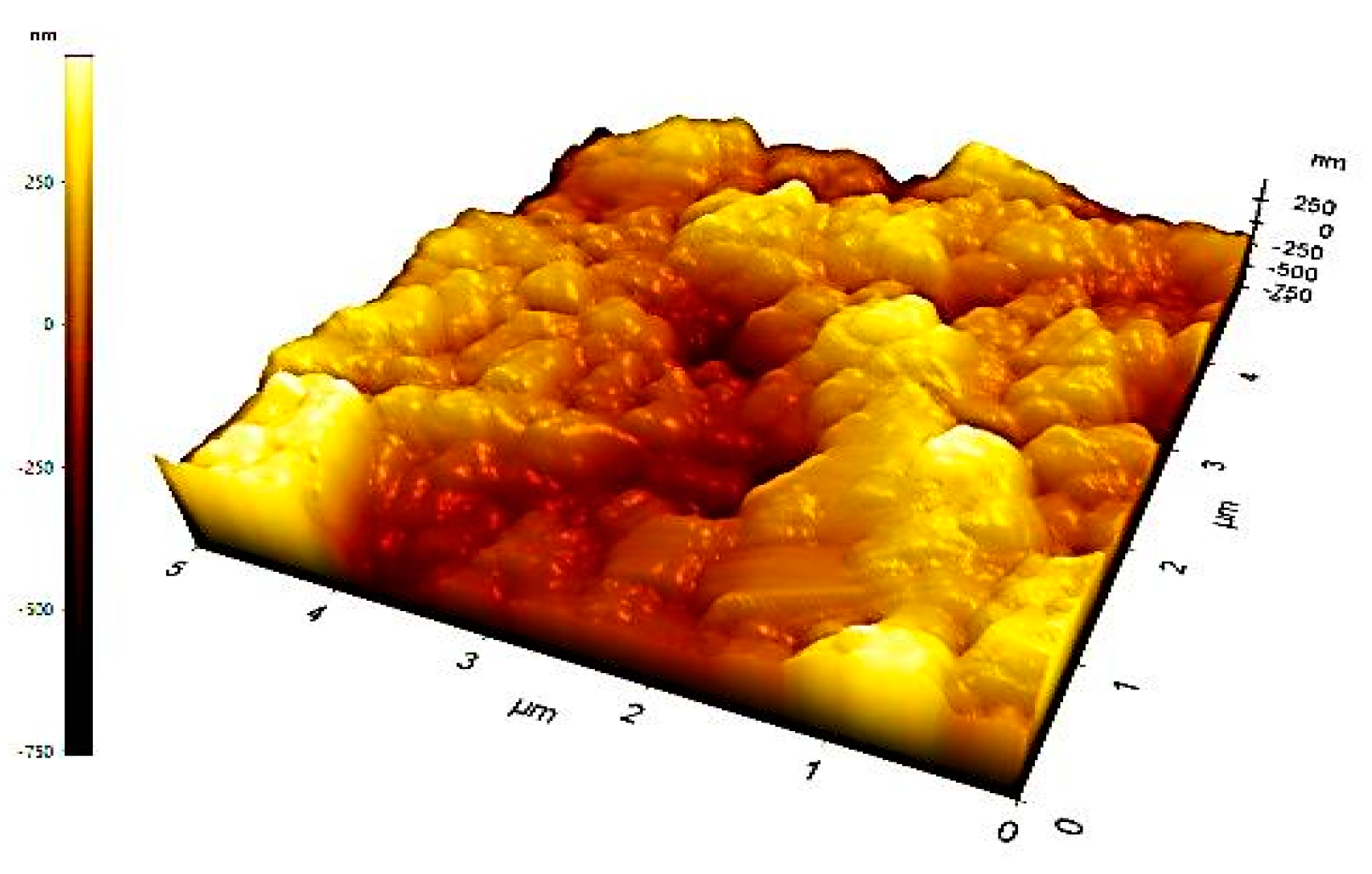

3.7. AFM Analysis:

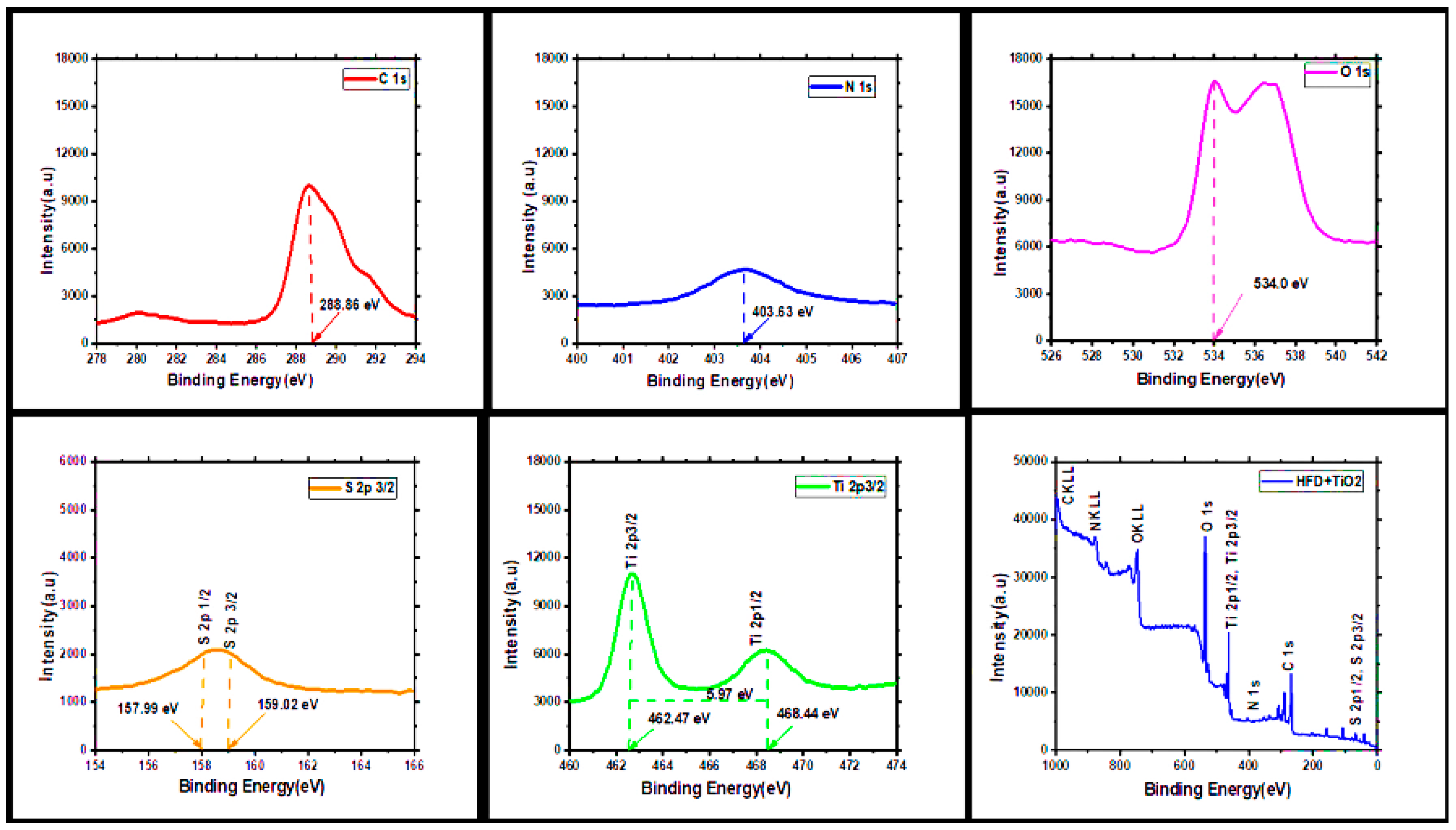

3.8. XPS Analysis:

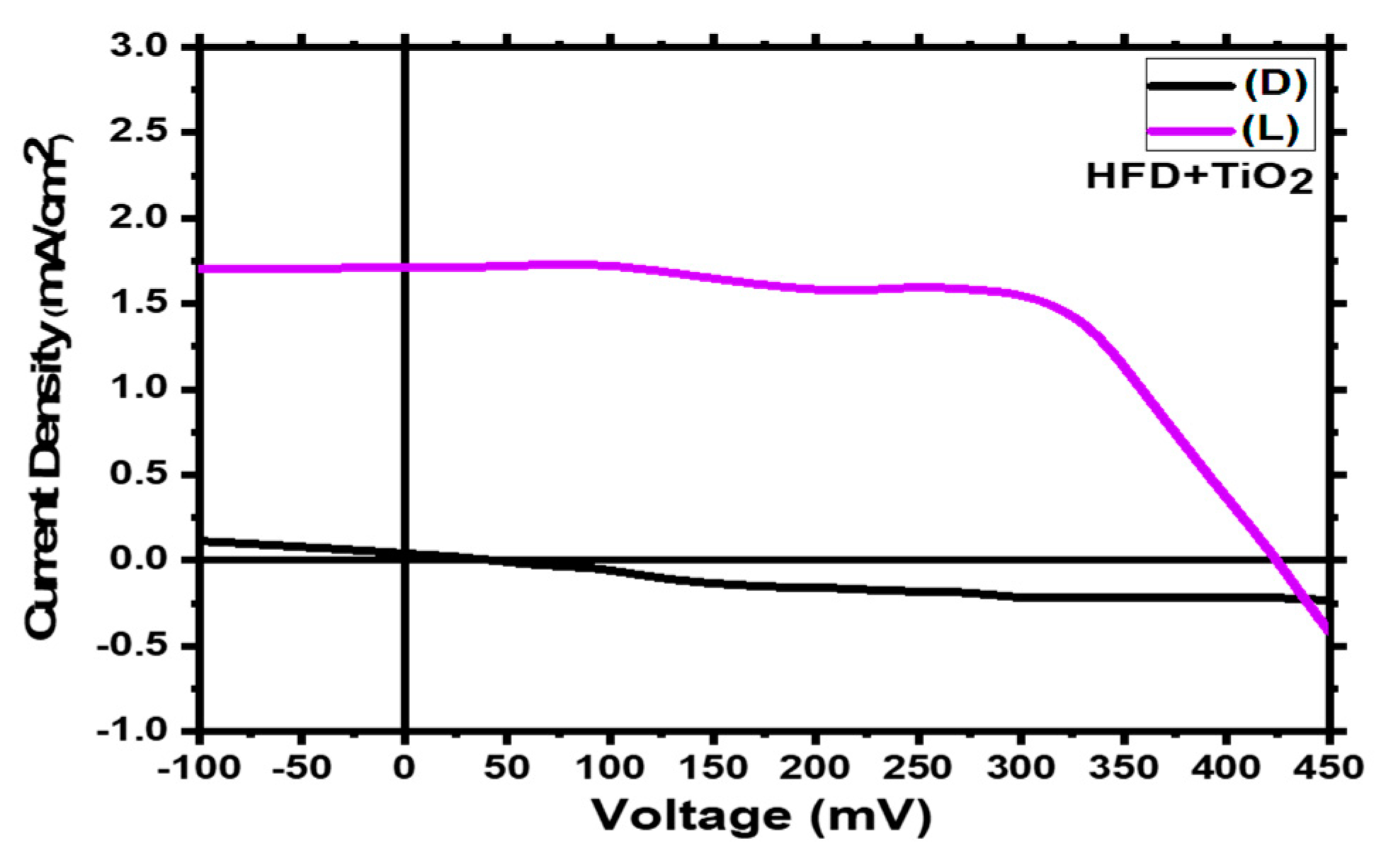

3.9. PEC Analysis:

4. Conclusion:

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Fakhfakh, N.; Ktari, N.; Haddar, A.; et al. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1731–1737. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, E.V.; Srijana, M.; Chaitanya, K.; et al. Biodegradation of poultry feathers by a novel bacterial isolate Bacillus altitudinis GVC11. Indian J Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul, T.I.; Embaby, A.M.; Elmahdy, A.R. Biodegradation of chicken feathers waste directed by Bacillus subtilis recombinant cells: Scaling up in a laboratory scale fermentor. Bioresour Technol. 2011, 102, 2387–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazotto, A.M.; Ascheri, J.L.R.; de Oliveira Godoy, R.L.; et al. Production of feather protein hydrolyzed by B. subtilis AMR and its application in a blend with cornmeal by extrusion. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2017, 84, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, S.; Wadhwa, N. Int J Poult Sci. 2010, 9, 482–489. [CrossRef]

- SAGARPA. Secretaria de Agricultura, ganaderia, desarrollo rural, pescay aliment ac ión. Escenario base: Proyecciones para el sector Agropecuario de México. Mexico DF 2009, 51–53.

- Kowalska, T.; Bohacz, J. Dynamics of growth and succession of bacterial and fungal communities during composting of feather waste. Bioresour Technol. 2010, 101, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotheim, T. Dye sensitized solar-cells US patent 4190950, 1980.

- Regan, B.; Gratzel, M. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [CrossRef]

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H.J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p–n junction solar cells. J Appl Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.A.; Meyer, G.J. Excited state processes at sensitized nanocrystalline thin film semiconductor interfaces. Coord Chem Rev. 2001, 211, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A.; Boschloo, G.; Sun, L.; Kloo, L.; Pettersson, H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem Rev. 2010, 110, 6595–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Fischer, M.K.R.; Bauerle, P. Metal-free organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells: from structure: property relationships to design rules. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009, 48, 2474–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, M.R. Review: dye sensitized solar cells based on natural photo- sensitizers. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Saha, A.; Kumar, S. Journal of Polymer Research 2021, 16, 441. [CrossRef]

- Oladele, I.O.; Okoro, A.M.; Omotoyinbo, J.A.; Khoathane, M.C. Journal of Taibah University for Science 2018, 12, 56–63. [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.; Sheikh, A.; Jain, V.; Lakshmi, N. Materials Science and Engineering 2021, 1187, 012005.

- Cano-Casanova, L.; Anson-Casaos, A.; Hernandez-Ferrer, J.; Benito, A.M.; Maser, W.K.; Garro, N.; Lillo-Rodenas, M.A.; et al. ACS Appl. Nano Material 2022, 5, 12527–12539. [CrossRef]

- Metwally, R.A.; El, Nady; Ebrahim, S.; et al. Microb Cell Fact. 2023, 22, 78. [CrossRef]

- Gokilamani, N.; et al. Materials in electronics 2013, 24, 3394. [CrossRef]

- Al-Taweel, S.S.; Saud, H.R. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research; 2016; 8, pp. 620–626.

- Sun, P.; Liu, Z.-T.; Liu, Z.-W. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 170, 786–790. [CrossRef]

- Bayram, S. Production, purification, and characterization of Streptomyces sp. strain MPPS2 extracellular pyomelanin pigment. Archives of Microbiology 2021, 203, 4419–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrejon-Sanchez, V.H.; Lopez, R.; Ramon-Gonzalez, M.; Enriquez-Perez, A.; Camacho-Lopez, M.; Villa-Sánchez, G. Crystals 2019, 9, 22. [CrossRef]

- Sahdan, M. Advances in Materials Physics and Chemistry 2012, 2, 16–20. [CrossRef]

- Sarathi, R.; Meenakshi Sundar, S.J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2022, 7, 252–266.

- Pawar, R.A.; Dubal, D.P.; Kite, S.V.; Garadkar, K.M.; Bhuse, V.M. J. Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2021, 32, 19676–19687.

- Gaur, B.; Mittal, J.; Shah, S.A.A.; Mittal, A.; Baker, R.T. Sequestration of an Azo Dye by a Potential Biosorbent: Characterization of Biosorbent, Adsorption Isotherm and Adsorption Kinetic Studies. Molecules 2024, 29, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More-Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes. New Journal of Science 2014, 498276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Upadhya, R.; Pandey, A. Novel Dye Based Photoelectrode for Improvement of Solar Cell Conversion Efficiency. Applied Solar Energy 2013, 49, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Mass% | Atom% |

|---|---|---|

| C | 4 | 7.31 |

| N | 0.28 | 0.44 |

| O | 52.68 | 72.3 |

| S | 0.94 | 0.64 |

| Ti | 42.11 | 19.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Sample | Voc ( mV) | Vmax ( mV) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Jmax (mA/cm2) | FF | η % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFD + TiO2 | 421.78 | 187.03 | 1.7 | 1.56 | 0.40 | 2.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).