Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

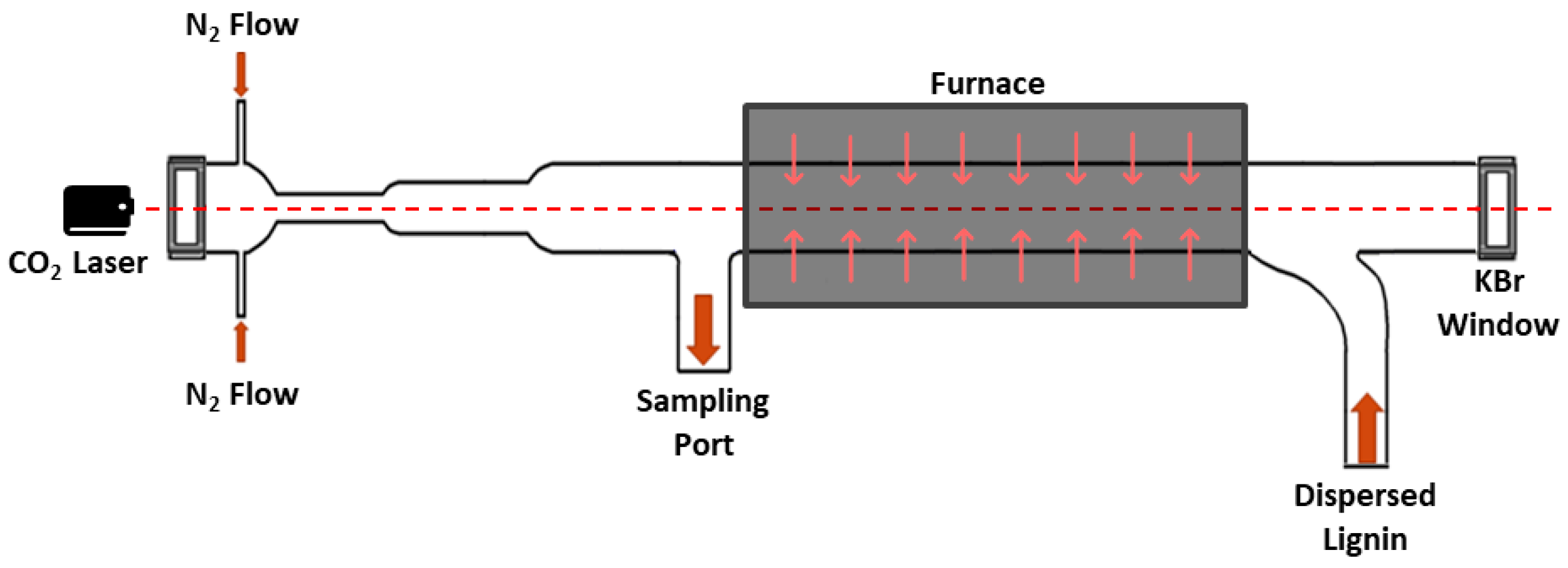

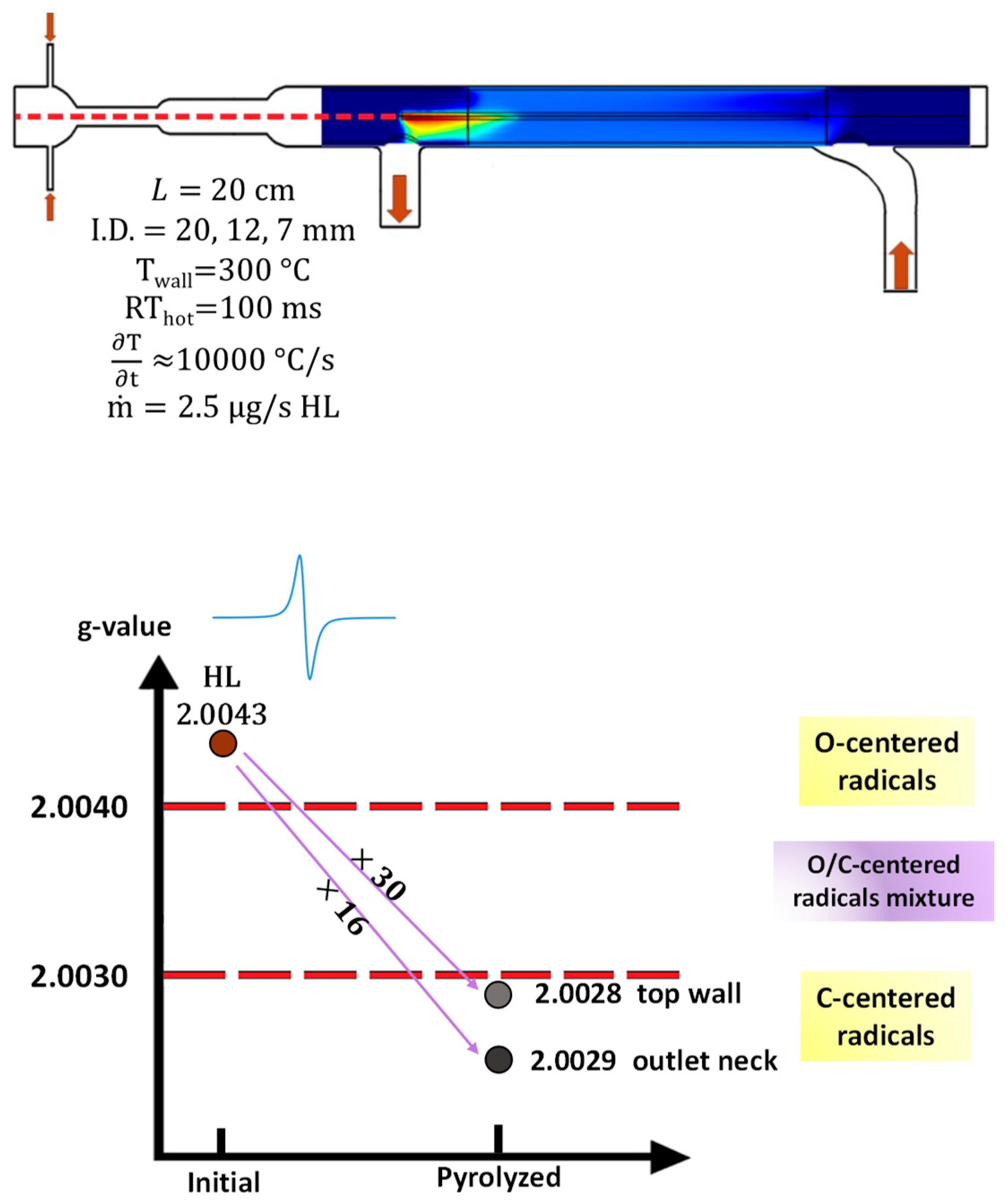

2.2. IR Laser Powered Homogeneous Pyrolysis (LPHP) Reactor

3. Results and Discussion

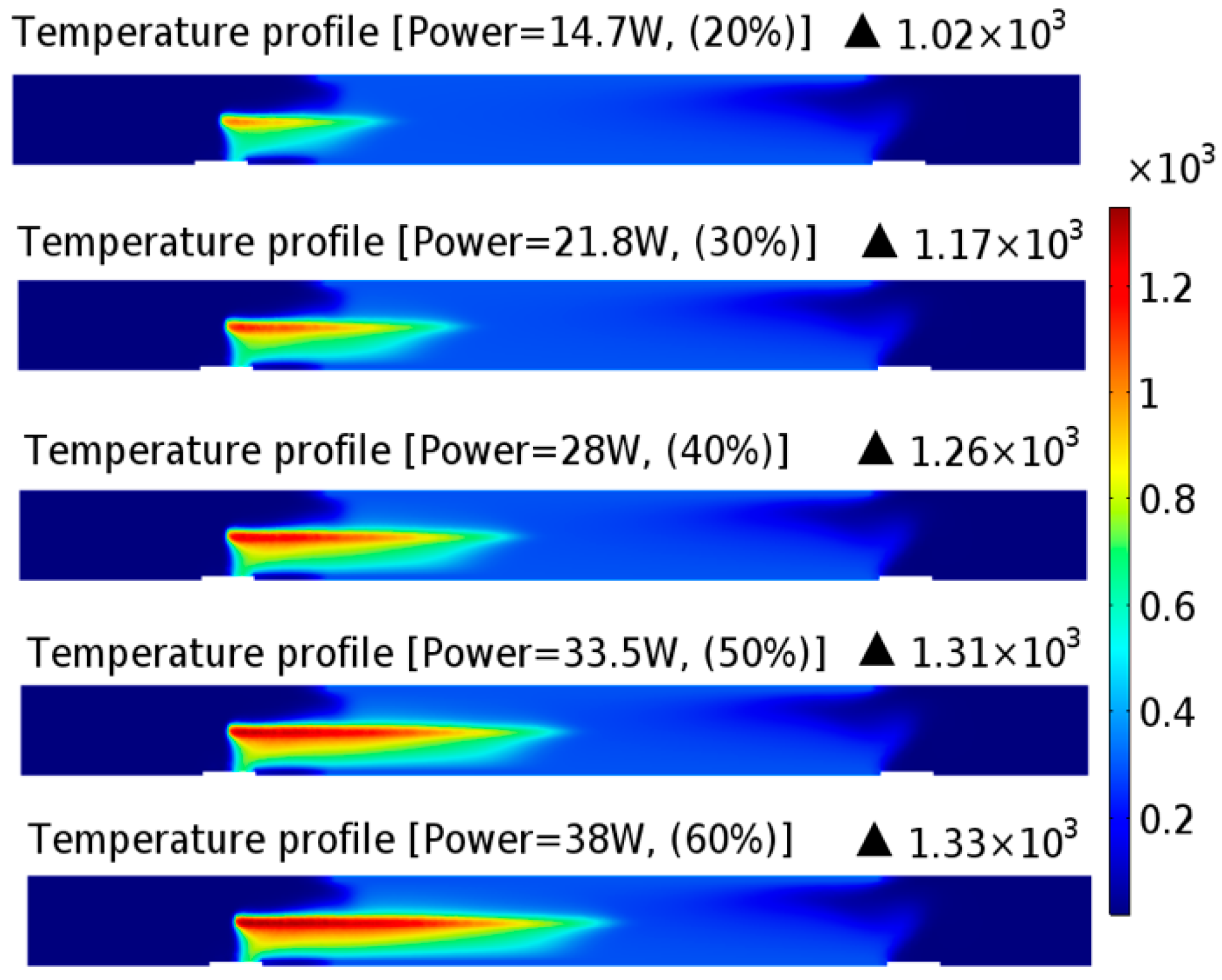

3.1. Temperature Distribution in LPHP Countercurrent Reactor

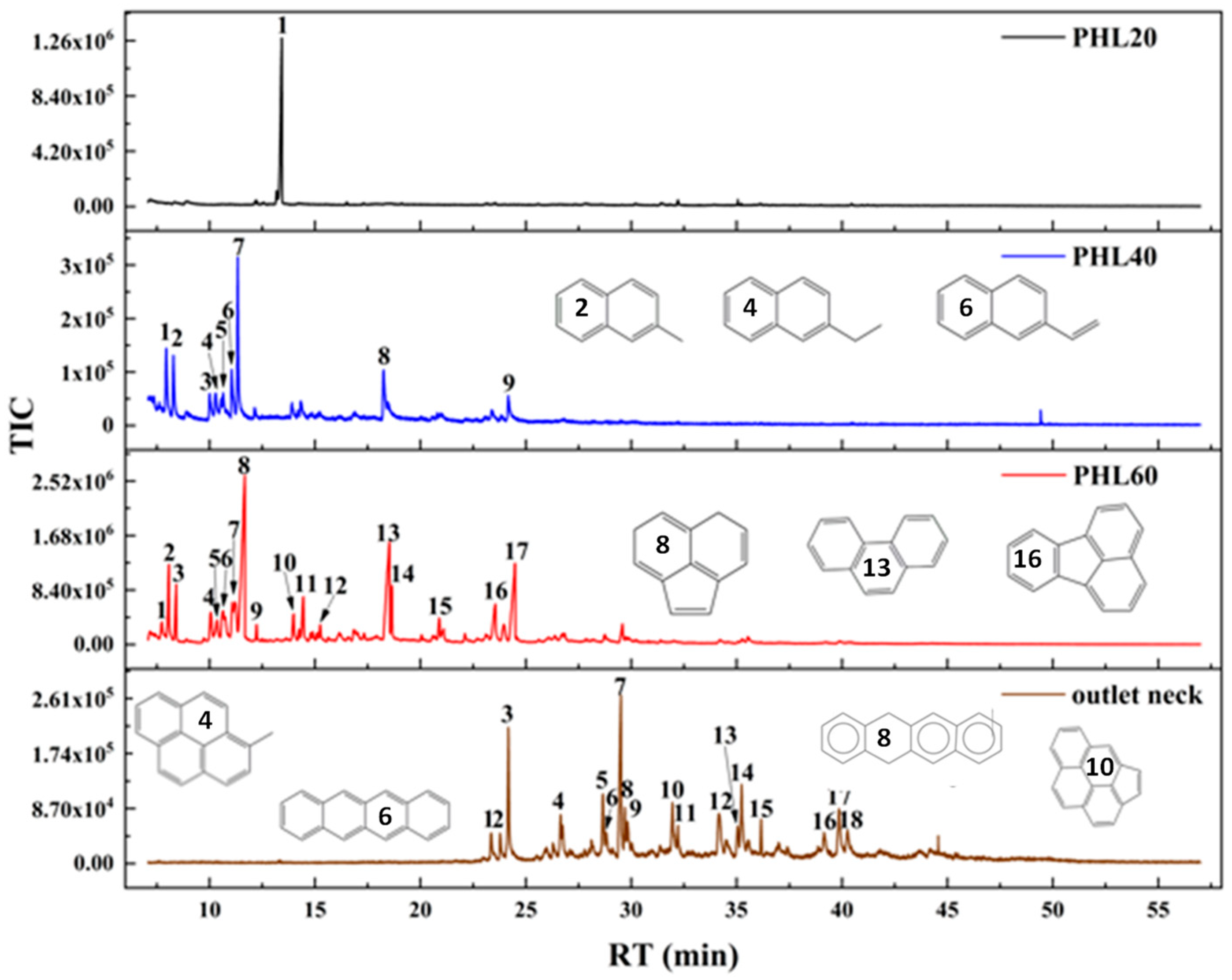

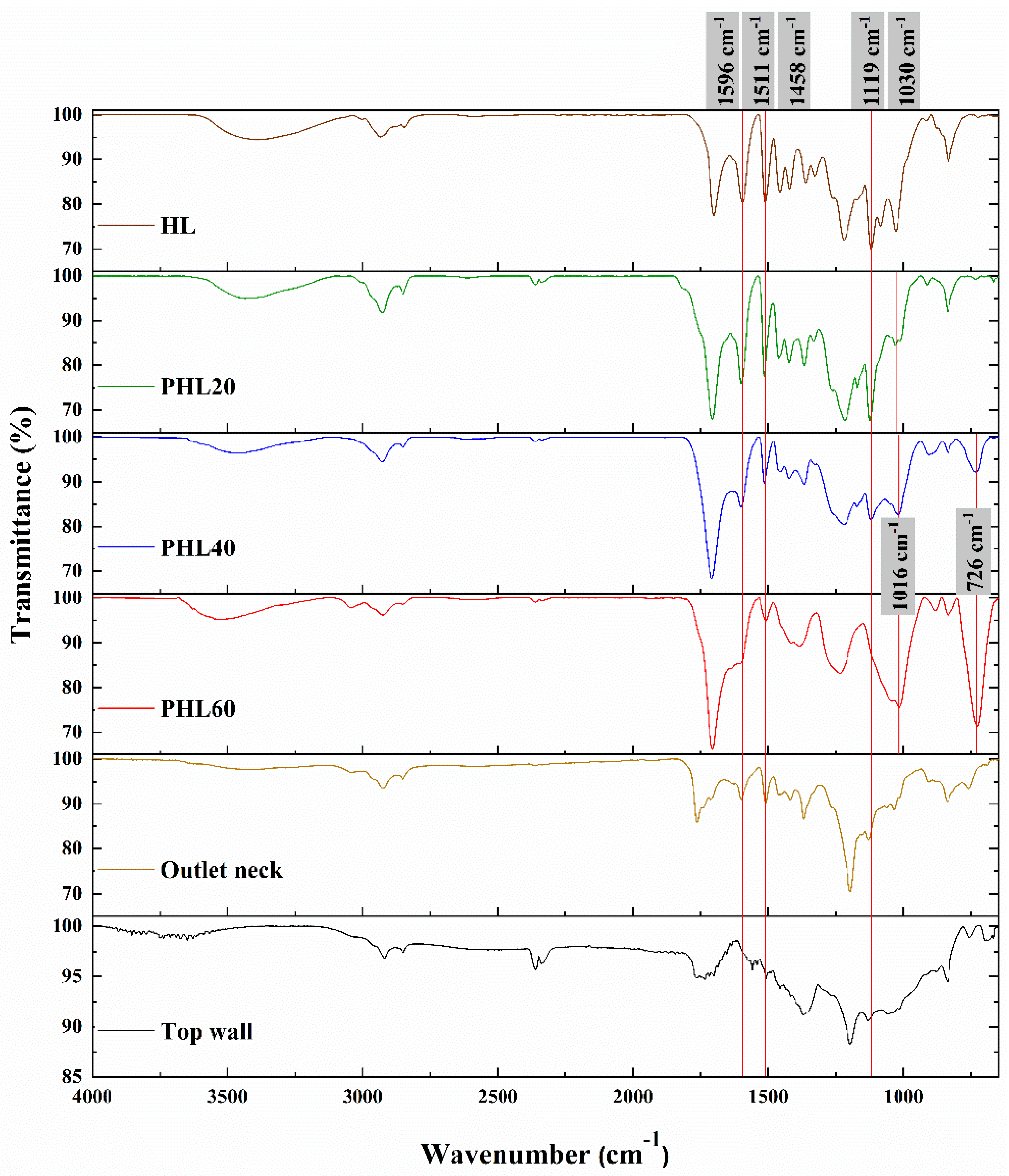

3.2. Condensable Products from Countercurrent LPHP Reactor

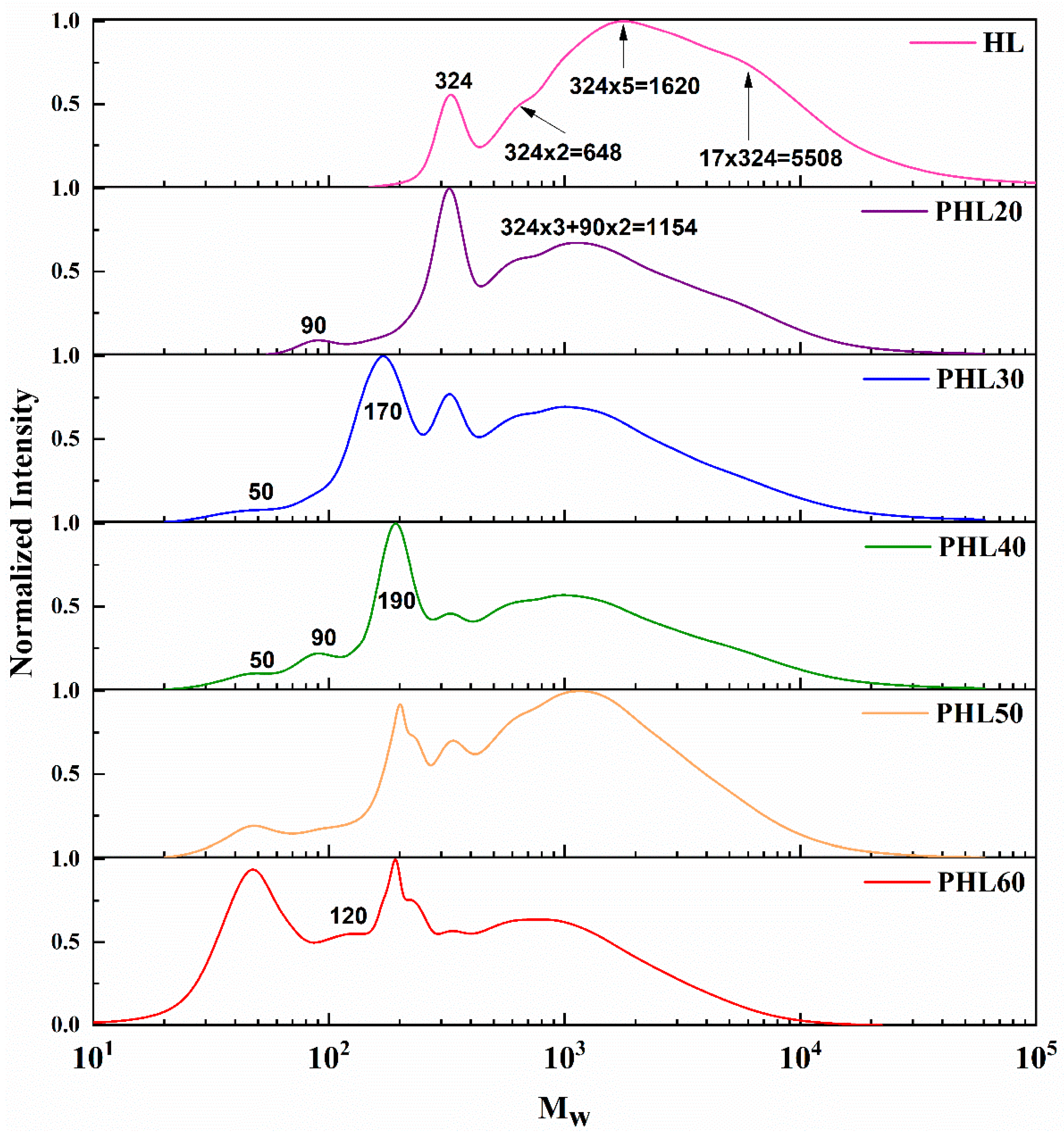

3.3. Molecular Weight Distribution of the Lignin Homogeneous Pyrolysis Products

3.3.1. GPC Analysis

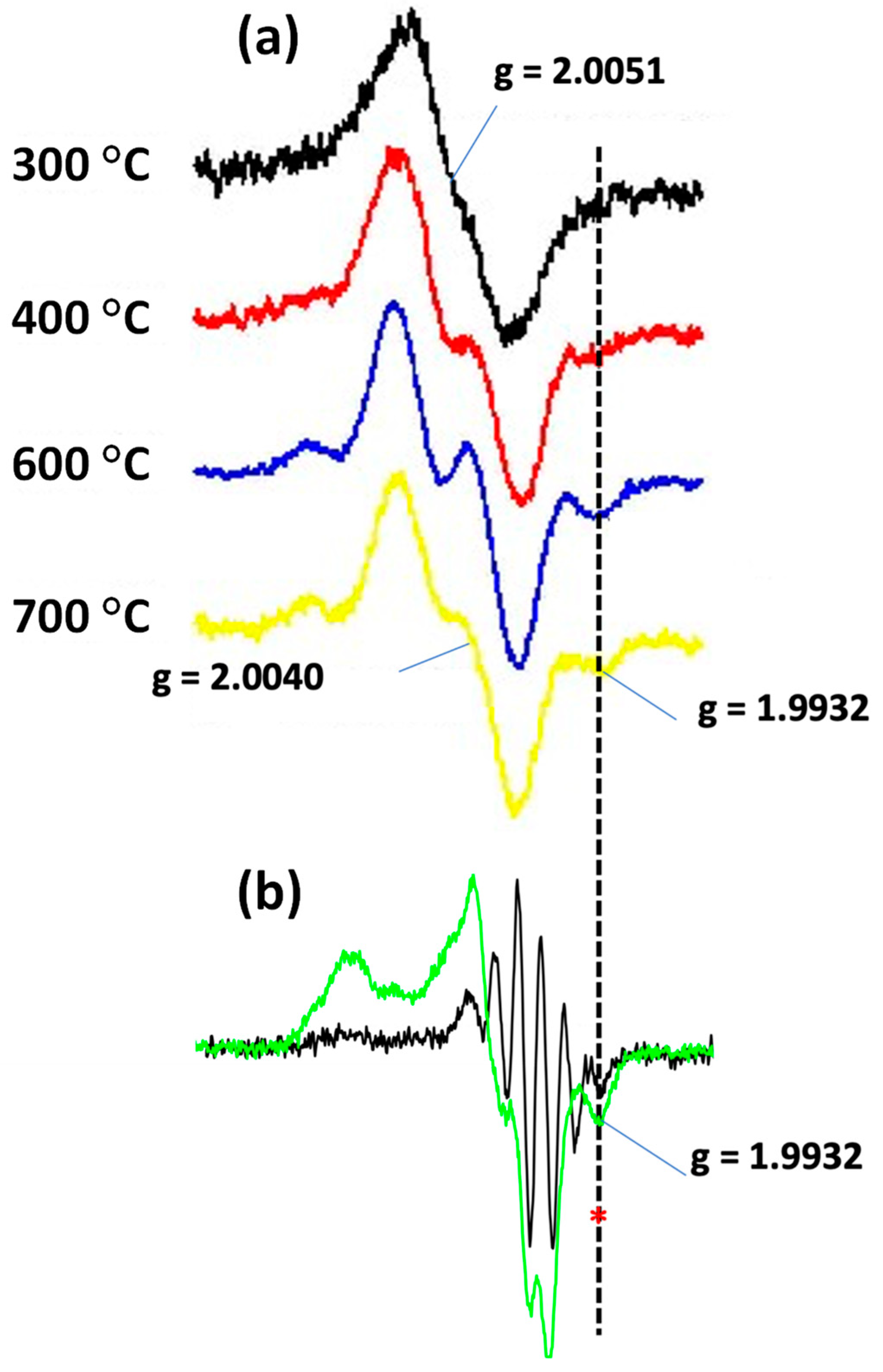

3.3.2. The Radical Character of the Decomposition of Lignin in LPHP Reactors

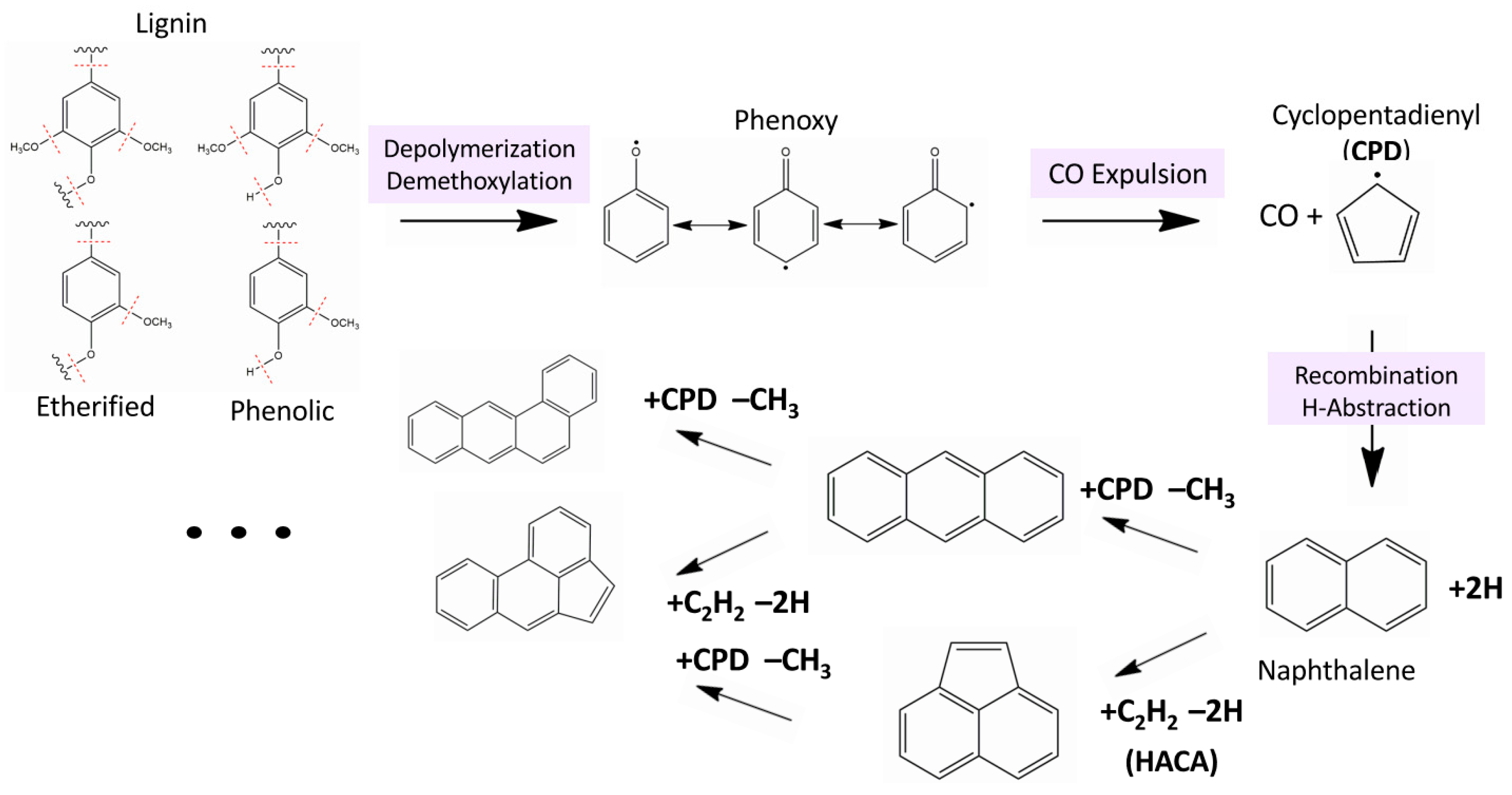

3.4. Formation Mechanism of PAHs from HL Gas-Phase Pyrolysis in LPHP Reactor.

3.4.1. Combustion Related Homogeneous Channels for Formation of PAHs

3.4.2. A “Heterogenous” Mechanism for Formation of PAHs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

References

- Barekati-Goudarzi, M.; Boldor, D.; Marculescu, C.; Khachatryan, L. Peculiarities of Pyrolysis of Hydrolytic Lignin in Dispersed Gas Phase and in Solid State. Energy & Fuels 2017, 31, 12156–12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barekati-Goudarzi, M.; Boldor, D.; Khachatryan, L.; Lynn, B.; Kalinoski, R.; Shi, J. Heterogeneous and Homogeneous Components in Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of Hydrolytic Lignin. Acs Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 12891–12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, L.; Barekati-Goudarzi, M.; Kekejian, D.; Aguilar, G.; Asatryan, R.; Stanley, G.G.; Boldor, D. Pyrolysis of Lignin in Gas-Phase Isothermal and cw-CO2 Laser Powered Non-Isothermal Reactors. Energ Fuel 2018, 32, 12597–12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Kekejian; L. Khachatryan; M. Barekati-Goudarzi; Boldor., D. Implication of COMSOL to Laser Powered Non-Isothermal Reactors for Pyrolysis in the Gas Phase. COMSOL CONFERENCE 2018, Boston Marriott Newton, October 3-5.

- McGrath, T.; Sharma, R.; Hajaligol, M. An experimental investigation into the formation of polycyclic-aromatic hydrocarbons( PAH) from pyrolysis of biomass materials. Fuel 2001, 80, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D.; Adamiano, A.; Torri, C. GC-MS determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons evolved from pyrolysis of biomass. Anal Bioanal Chem 2010, 397, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozliak, E.I.; Kubatova, A.; Artemyeva, A.A.; Nagel, E.; Zhang, C.; Rajappagowda, R.B.; Srnirnova, A.L. Thermal Liquefaction of Lignin to Aromatics: Efficiency, Selectivity, and Product Analysis. Acs Sustain Chem Eng 2016, 4, 5106–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerholm, R.N.; Alsberg, T.E.; Frommelin, A.B.; Strandell, M.E.; Rannug, U.; Winquist, L.; Grigoriadis, V.; Egeback, K.E. Effect of Fuel Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Content on the Emissions of Polycyclic Aromatic-Hydrocarbons and Other Mutagenic Substances from a Gasoline-Fueled Automobile. Environmental Science & Technology 1988, 22, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.V.; Corrêa, S.M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in diesel emission, diesel fuel and lubricant oil. Fuel 2016, 185, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, C.F.; Onwudili, J.A.; Meng, A.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Williams, P.T. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Formation from the Pyrolysis/Gasification of Lignin at Different Reaction Conditions. Energy & Fuels 2014, 28, 6371–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A.; Lee, Y.J. Petroleomic Analysis of Bio-oils from the Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass: Laser Desorption Ionization−Linear Ion Trap−Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry Approach. Energy & Fuels 2010, 24, 5190–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaub, W.M.; Bauer, S.H. Laser-Powered Homogeneous Pyrolysis. Int J Chem Kinet 1975, 7, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, P.; Pola, J. Spatial Temperature Distribution in Cw Co2-Laser Photosensitized Reactions. Collect Czech Chem C 1984, 49, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, Y.N.; Panfilov, V.N.; Petrov, A.K. Infrared Photochemistry. Novosibirsk, Izd. Nauka 1985.

- Sukiasyan, A.A.; Khachatryan, L.A.; Il’in, S.D. Measuring of the kinetic parameters of homogeneous decomposition of Azomethane under CO2-laser irradiation. Arm. Khim.Zhur. 1988, 41, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.K. Infrared-Laser Powered Homogeneous Pyrolysis. Chem Soc Rev 1990, 19, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantashyan, A.A. Peculiarities of the slow combustion of a hydrocarbon in a ''wall-less'' reactor with laser heating. Combust Flame 1998, 112, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swihart, M.T.; Carr, R.W. Pulsed laser powered homogeneous pyrolysis for reaction kinetics studies: Probe laser measurement of reaction time and temperature. Int J Chem Kinet 1996, 28, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorciuc, T.; Capraru, A.-M.; Kratochvilova, I.; Popa, V.I. Characterization of non-wood lignin and its hydroxymethylated derivatives by spectroscopy and self-assembling investigations. 2009, 43, 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Faix, O. Classification of Lignins from Different Botanical Origins by FT-IR Spectroscopy. 1991, 45, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Wooten, J.B.; Baliga, V.L.; Lin, X.; Chan, W.G.; Hajaligol, M.R. Characterization of chars from pyrolysis of lignin. Fuel 2004, 83, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, J.; Bobeldijk Pastorova, I.; Botto, R.E.; Arisz, P. Structural studies on cellulose pyrolysis and cellulose chars by PYMS, PYGCMS, FTIR, NMR and by wet chemical techniques. Biomass and Bioenergy 1994, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, H.; Ragauskas, A.J. Comparison for the compositions of fast and slow pyrolysis oils by NMR characterization. Bioresource Technology 2013, 147, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, P.S.; Westerhof, R.J.M.; Kersten, S.R.A. Fast pyrolysis of lignins with different molecular weight: Experiments and modelling. Applied Energy 2019, 236, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Garcia-Perez, M.; Pecha, B.; Kersten, S.R.A.; McDonald, A.G.; Westerhof, R.J.M. Effect of the Fast Pyrolysis Temperature on the Primary and Secondary Products of Lignin. 2013, 27, 5867-5877. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Garcia-Perez, M.; Pecha, B.; Kersten, S.R.A.; McDonald, A.G.; Westerhof, R.J.M. Effect of the Fast Pyrolysis Temperature on the Primary and Secondary Products of Lignin. Energy & Fuels 2013, 27, 5867–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Formation of nascent soot and other condensed-phase materials in flames. P Combust Inst 2011, 33, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenklach, M.; Gardiner, W.C.; Stein, S.E.; Clary, D.W.; Yuan, T. Mechanism of Soot Formation in Acetylene-Oxygen Mixtures. Combustion Science and Technology 1986, 50, 79–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenklach, M.; Singh, R.I.; Mebel, A.M. On the low-temperature limit of HACA. P Combust Inst 2019, 37, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggese, C.; Frassoldati, A.; Cuoci, A.; Faravelli, T.; Ranzi, E. A wide range kinetic modeling study of pyrolysis and oxidation of benzene. Combust Flame 2013, 160, 1168–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, E.B.; Marsh, N.D.; Sandrowitz, A.K.; Wornat, M.J. Global kinetic rate parameters for the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from the pyrolyis of catechol, a model compound representative of solid fuel moieties. 2002, 16, 1331-1336. [CrossRef]

- Mastral, A.M.; Callen, M.S. A review an polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) emissions from energy generation. 2000, 34, 3051-3057. [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, M.; Kojima, Y.; Kato, Y. Formation mechanism of polycyclic compounds from phenols by fast pyrolysis. EC Agriculture 2015, 1, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, C.; Onwudili, J.A.; Meng, A.; Zhang, Y.; Williams, P.T. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Formation from the Pyrolysis/Gasification of Lignin at Different Reaction Conditions. Energy & Fuels 2014, 28, 6371–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.F. Sarofim; J.P. Longwell; M.J. Wornat; J. Mukherjee; (Ed.), i.H.B. Soot Formation in Combustion. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1994.

- Shukla, B.; Koshi, M. Comparative study on the growth mechanisms of PAHs. Combust Flame 2011, 158, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Mulholland, J.A. Chemosphere 2001, 42, 623. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hu, B.; Koylu, U.O. Mean soot volume fractions in turbulent hydrocarbon flames: A comparison of sampling and laser measurements. Combustion Science and Technology 2005, 177, 1603–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.C.; Smith, M.C.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.J.; Green, W.H. Theoretical study on the HACA chemistry of naphthalenyl radicals and acetylene: The formation of C12H8, C14H8, and C14H10 species. Int J Chem Kinet 2020, 52, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, L.; Adounkpè, J.; Maskos, Z.; Dellinger, B. Formation of Cyclopentadienyl Radical from the Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of Hydroquinone, Catechol, and Phenol. Environmental science & technology 2006, 40, 5071–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, L.; Adounkpe, J.; Dellinger, B. Formation of Phenoxy and Cyclopentadienyl Radicals from the Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of Phenol. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2008, 112, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrent Khachatryan; Meng-xia Xu; Ang-jian Wu; Mikhail Pechagin; Asatryan, R. Radicals and Molecular Products from the Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of Lignin Model Compounds. Cinnamyl Alcohol. J. Anal.Appl.Pyr 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.X.; Khachatryan, L.; Baev, A.; Asatryan, R. Radicals from the Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of Lignin Model Compounds. p-Coumaryl Alcohol. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 62399–62405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien Adounkpe; Martin Aina; Daouda Mama, a.; Sinsin, B. Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Identification of Labile Radicals Formed during Pyrolysis of Catechool, Hydroquinone, and Phenol through Neutral Pyrolysis Product Mass Analysis. Hindawi Publishing Corporation; ISRN Environmental Chemistry 2013, Article ID 930573.

- Custodis, V.B.F.; Hemberger, P.; Ma, Z.Q.; van Bokhoven, J.A. Mechanism of Fast Pyrolysis of Lignin: Studying Model Compounds. J Phys Chem B 2014, 118, 8524–8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, J.A.; Lu, M.; Kim, D.H. Pyrolytic growth of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by clyclopentadienyl moieties. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2000, 28, 2593–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, P.; Khachatryan, L.; Lomnicki, S.; Dellinger, B. Paramagnetic centers in particulate formed from the oxidative pyrolysis of 1-methylnaphthalene in the presence of Fe(III)(2)O-3 nanoparticles. Combust Flame 2013, 160, 2996–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asatryan, R.; Bennadji, H.; Bozzelli, J.W.; Ruckenstein, E.; Khachatryan, L. Molecular Products and Fundamentally Based Reaction Pathways in the Gas-Phase Pyrolysis of the Lignin Model Compound p-Coumaryl Alcohol. J Phys Chem A 2017, 121, 3352–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, B.; Koshi, M. A novel route for PAH growth in HACA based mechanisms. Combust Flame 2012, 159, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockhorn, H.; Fetting, F.; Wenz, H. Investigation of the Formation of High Molecular Hydrocarbons and Soot in Premixed Hydrocarbon-Oxygen Flames. Berichte der Bunsengesellschaft für physikalische Chemie 1983, 87, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenklach, M.; Warnatz, J. Detailed Modeling of PAH Profiles in Sooting Low-Pressure Acetylene Flame. Combustion Science and Technology - COMBUST SCI TECHNOL 1987, 51, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrent Khachatryan; Zofia Maskos, a.; Dellinger., B. The Tar and Tar Radicals from Lignin Pyrolysis. . SFRBM (Society for Free Radical Biology and Medicine) 2014, November 19-23.

- Khachatryan, L.; Adounkpe, J.; Dellinger, B. Formation of Phenoxy and cyclopentadienyl radicals from the gas-phase pyrolysis of phenol. J.Phys.Chem., A 2008, 112, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Peak Assignment |

| 3394 | O−H stretching in hydroxyl groups in phenolic and aliphatic structures [19,20] |

| 2936 | C−H stretching in methoxy, methyl and methylene [19] |

| 2846 | C=O stretching in p-substituted aryl ketones [19] |

| 1700 | C=C stretching in aromatic ring (S) [19] |

| 1596 | C=C stretching in skeletal aromatic ring (S>G) [20,21] |

| 1511 | C=C stretching in skeletal aromatic ring (G>S) [20,21] |

| 1458 | C−H bending in methoxy and methylene [20] |

| 1422 | C−H in-plane deformation combined with skeletal aromatic ring [20] |

| 1367 | O−H in-plain bending [21];O−H in phenol, aliphatic C−H stretch in CH3 [20] |

| 1326 | C−H bending in aromatic ring (S or condensed G) [20] |

| 1220 | Aryl−O of aryl−OH and aryl−OCH3 [20] |

| 1119 | C−H bending in aromatic ring (S> condensed G) [20] |

| 1085 | C−O deformation in secondary alcohols and aliphatic ethers [20] |

| 1030 | C−O stretch in O−CH3 and C−OH [21] |

| 915 | C−H out-of-plane deformation of aromatic ring [20] |

| 834 | C−H out-of-plane in H unit and C2,6 of S unit [20] |

| 726 | C−H wags for an aromatic fused ring [21] |

| HL | PHL20 | PHL30 | PHL40 | PHL50 | PHL60 | |

| Mw (g/mol) | 5591 | 2298 | 1985 | 1947 | 1601 | 763 |

| Mn (g/mol) | 1397 | 614 | 325 | 309 | 354 | 113 |

| PDI | 4.0 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 6.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).