1. Introduction

Polymer resins, in their unaltered form, fulfill numerous performance criteria but lack the coloration that appeals to consumers. Creating plastic that a commercially viable color necessitates the use of, in general, more than one pigments; yet, attaining the desired hue on the initial attempt is a significant hurdle. Nevertheless, getting the right shade on the first try could be quite difficult. There are a lot of factors that affect how polymers look. Screw speed and screw design, temperature FRate, and residence time all play a role in their extrusion process. Several studies have looked at how different process variables affect the final color of polymer compounding [

1,

2]. Due to the pigment’s chemical composition, it is highly probable that they will experience specific chemical reactions that will depend on the specific process circumstances. Moreover, the polymer's characteristics may be impacted by the substantial link between time and temperature. Therefore, the desired hue need a carefully chosen variables from our researchers. To achieve the required pigment dispersion and ideal homogeneity, reduce the resin's viscosity and increase the mixing time [

3]. When it comes to quality assurance, color measurement, and numerical comparison of color changes, spectrophotometers are indispensable [

3]. For polycarbonate grade-3, we established limitations for dE at or below 1.0 and for dL*, da*, and db* at or below 0.6, although in most cases, customers decide what is considered a suitable tolerance limit [

4]. The "dE*" represents the dispersion in (b*) (L*), & (a*):

In place of utilizing color values that are absolute, color differences concerning target values regarding dL*, da*, and db* are used. We represent the color difference in the CIELAB color space using the total change in color, dE* [

5].

This study states these challenges by examining the effects of various processing conditions on PC blends with additives and composites, focusing on color consistency. This study finds the best ways to use statistical tools like DOE and processing parameters to improve the quality and accuracy of color in colored polymer products. It accomplishes this by extrusion, blending, and color testing, studying their rheology and RSMs, and looking at their surface morphology and microstructural characteristics. With the rising importance of sustainability and preparing the way for advanced solutions that develop color consistency and execution [

6,

7,

8].

Reducing waste and expediting material delivery are the largest challenges facing polymer compounders; compounding is the process of homogeneously mixing pigments in predetermined amounts and ratios to create the desired color. These pigments, typically different colors, reflect the incident light at various depths, resulting in the desired color being seen as the result of the combined effect of reflection [

9,

10].

Color deviations can result from a variety of factors, such as differences in formulations or pigment dispersions and the effects of processing parameters on material performance; examine the results of these variations in color combinations when compounding is a unique opportunity. According to the CIE, L*, a*, and b* color values were obtained using a spectrophotometer [

11,

12].

This study looks at process characteristics in order to improve color choices and create more accurate simulation models. Feed rate (FRate), Speed (Sp), & Temperature (T) were the processing variables examined. We used the 3-Level- Full-Factorial Design (3LFFD) as well as (BBD) response surface techniques to adjust uniform processing in three levels. This study employed an experimental approach to optimize process parameters while holding all other variables constant. The Design Expert software facilitated experimental design while also allowing for statistical and numerical optimization. We used this technique to generate a statistical equation for simulated regression models. The optimal tristimulus color values have the smallest color variance (dE*). The created model and experimental data were passed all diagnostic tests. Statistically, these tests show that the model is valid . We have confirmed the model's statistical validation when all diagnostic tests were passed by both the created model and the experimental data.

The dL*, da*, and db* color parameters and the specific mechanical energy (SME) were all significantly impacted by the three parameters that were considered in the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Furthermore, we calculated specific mechanical energy for the experimental trials and found that it decreased as the Frate increased. The study concludes by comparing the two design models to determine which produces the best color quality.

Choosing the right process settings is crucial for reducing color fluctuations (dE*). Furthermore, during the experimental trials, we performed microscopic characterization, including agglomeration level assessments. To determine pigment dispersion, the collected data was analyzed using SEM as well as Micro-CT scanner pictures (MCT). This work contributes to optimize potential modelling design and manufacturing difficulties that affect color variability and waste minimization, for diverse chemical grades; hence, encouraging environmentally friendly operations.

The addition of additives to polymeric components may have led to unforeseen effects on their viscosity, mechanical processing, properties, and visual appearance [

13,

14]. A multitude of studies has explored the incorporation of color into virgin resin. In the experiment, we used the Response-Surface Method (RSM). This method included different processing conditions and three levels of process variables. When we optimally combined (FRate, T & Sp) values under specified processing conditions, we observed a deviation which is slight comparing to the expectation of the color output [

15,

16,

17,

18].

On top of that, the Response-Surface Method (RSM) generates new insights, improves material performance, and makes it possible to investigate intricate interrelationships. RSM has recently achieved remarkable achievements in enhancing the performance characteristics of polymer materials through statistical modeling and property refinement in PC composites. Using RSM has been shown to improve the performance of polycarbonate nanocomposites by looking at how key factors that affect material properties interact with each other [

19,

20].

To investigate the color variations caused by changes in processing parameters, we employed the Statistical Design of Experiments. Techniques such as Response Surface Methodology (RSM) facilitate this process. Careful experimental design to evaluate model parameters after execution is the first step in this process; then formulate a second-order polynomial for the responses [

21].

Design of trials (DOE) is a systematic methodology enabling an investigator to organize trials and ascertain cause-and-effect correlations. Because it decreases the necessary number of tests, DOE is actively used by several scientific areas. Improving the extrusion process parameters is key to getting these pigments dispersed evenly. A compounded polycarbonate grade's color characteristics were the subject of investigations to determine process parameters’ impact over these features. Therefore, we decided to build a regression model. The color disparity was caused by a myriad of factors. Understanding how these factors affect the final hue requires investigation of these factors [

21,

22].

In order to optimize process variables, many different experimental designs have been found to be effective. The impact on PVC-sheets' surface look and gloss with varying compounding process factors was studied using a modified general factorial Design of Experiments (DOE) [

23]. Some examples of RSM designs are: the factorial, the Central-Composite Design: CCD, the BBD, and the D-optimal [

24]. Research has shown that a DOE using the BBD may determine the relationship between processing factors and the variance in wood-plastic matrix viscosity [

25].

As a combined array design, the Box-Behnken Design (BBD) streamlines the computation of substantial interactions and reduces the number of runs needed compared to Taguchi's crossing array designs [

26]. With this method, you can construct a quadratic model with just three levels per factor, and it is quite economical in terms of runs [

26,

27]. Some designs, like a Central Composite Design (CCD) with five levels of each element or a Three-Level Factorial Design with potentially more trial runs, are required to estimate curvature.

To determine the produced quadratic model's usefulness and importance, as well as the model's suitability, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) is necessary. The process parameters' impact and how they interact were examined in the study. By giving careful thought to error propagation (POE), RSM designs become more dependable. When calculating POEs—the standard deviation of changes in output’s responsiveness resulting from, during experimentation, significant controllable process factors changes [

28]; we do not think noise is a big deal.

The processing parameters are thoroughly analyzed using design of experiments (DOE) in this study. Finding out how many tests would be necessary to collect enough data for a thorough study became much easier with the help of DOE. We designed the systems with processing speed, FRate, temperature, and accuracy in mind. We looked at how the parameters of the output response changed depending on the processing settings. To learn how the color of compounded plastics changed as processing parameters were adjusted, the researchers ran systematic testing on different grades; we looked over the data to find the optimal processing parameters for reducing waste while guaranteeing on-time order delivery.

If you want to find out how different processing settings affect color, you can use Statistical Design of Experiments (DOE) with approaches like RSM. In order to efficiently evaluate our model factors, some researchers have been implementing, the first step is to carefully prepare the experiments, followed by the recreation of a second-order polynomial to stand in for the replies [

27,

28].

The expected outcome is represented by y in this context, while the remaining values are as follows: b0: a constant, bii: the ith-quadratic coefficient, bi: the ith-linear coefficient, bij: the ith-interaction coefficient, k: # of factors, ε: the error, and xi: the independent variable. The model's coefficients are predicted by regression analysis of the collected experimental data. Some researchers have outlined the methodology used to estimate the model's parameters in their subsequent publications [

27,

28]. Optimization, process improvement, and development can all benefit from RSM's statistical and mathematical approaches. One of the most powerful and successful response surface methods is the 3LFFD when compared with others like Central Composite, Doehlert matrix, and BBD. We aim to utilize a three-LFFD. This design determines the optimal processing settings that minimize color disparities (dE* < 0.8).

A lot of research has looked at how processing parameters affect properties like water permeability and salt rejection, and ANOVA has confirmed those findings. Design of Experiment (DOE) models show how these parameters affect material properties, which helps to optimize pigment and polycarbonate mixes for better performance. We created supplementary models utilizing the Design of Experiments methodology. On the other hand, polyacrylic acid-graphene-oxide, a compound with multiple applications, had their synthesis parameters optimized using Response-Surface Methodology (RSM). Results from further analyses of variance (ANOVA) validated the models [

29,

30,

31,

32].

To get consistent color properties in plastics, this research looks at mixing two polycarbonate resins. Optimizing for speed, temperature, and FRate, this study employs DoE and RSM to see how pigment dispersion is affected. Improved production of colored polymer goods is the result of its use of prior industry data that addresses color consistency difficulties [

33,

34]. Some researchers argue that when Polycarbonate (PC) mixed with Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) may reduce the overall viscosity, allowing the components to glide about during injection molding, therefore improving the process [

35]. The study concludes by looking into letdown and pigment dispersion and how they are affected by the processing temperature to growth ratio in polymer matrices. It examines thermal stability plus viscosity parameters [

36].

SEM offers critical invaluable information about polycarbonate blends' characteristics (in particular, the microstructural ones), especially for examining agglomeration as well as pigment dispersion. The findings demonstrate significant shear thinning exhibited by Acrylonitrile-Butadiene Styrene (ABS), while, Polycarbonate (PC) largely exhibits Newtonian behavior [

37,

38]. In emulsions of polymers with a high viscosity: surface morphology, particle size, as well as distribution are studied in this report using a structured approach to Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). This method effectively solves the issues related to high-viscosity SEM analysis, giving a clear picture of the emulsion's microstructure at different viscosities [

37,

38].

Researchers also use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to find out how pigment dispersion quality affects color uniformity. They find that consistent dispersion reduces color variations and clumping [

39]. Researchers broadened their scope to investigate the variations in autonomous processing characteristics. For consistent output color, researchers used variables like speed, FRate, temperature to influence the dependent responses (L*, a*, b*, dE). When you compare the three-level full factorial and BBD designs to other methods, for example, BBD, the central composite, as well as Doehlert matrix, they considered the most powerful and effective response-surface.

Focusing on polycarbonate matrices specifically, this study aims to examine pigment dispersion-processing factors-color consistency interplay in compounded plastics. This work methodically optimizes pigment-mixing processes using two separate methodologies: RSM as well as DOE. This investigation enhances our understanding of consistency as well as color stability and how they impacted by processing conditions. Researchers’ concentration is enhancing the process of blending various pigments and additives with two polycarbonate resins. The extrusion speed (650, 750, and 850 rpm), temperature (230, 255, and 280 °C), and FRate (11, 19, and 27 kg/h) will be systematically varied during 17 Box-Behnken Designs (BBD) runs. Furthermore, we perform 32 experimental runs in 3LFFD, systematically adjusting the extrusion where Sp: 700 rpm, 750 rpm, and 800 rpm, T: 230 °C, 255 °C, and 280 °C while FRate: 20 kg/h, 25 kg/h, and 30 kg/h. we are Utilizing the software(version eight) of Design-Expert. Therefore, optimize the most effective design by analyzing the significant interactions of processing parameters in order to improve the accuracy of first-pass color while reducing color variability. Using both microscopies, the multi-mode (MCT) as well as scanning electron (SEM) scanning analysis, we will determine the effects of dispersion on the chemical and physical structures of the materials. In addition, we will verify the density of the agglomerations and the color consistency of the processed materials. The main goal is to find a correlation between processing parameters and color outputs so that color formulations can be more reliably improved. Our goal focuses on utilization as well as the comparison of two designs to optimize processing parameters, aiming for minimal deviation in color properties (dE* < 1.0). We will conduct further characterizations to assess the structure and efficiency of color dispersions. Optimal colors were determined and statistically significant models were generated by both designs.

2. Materials and Methods

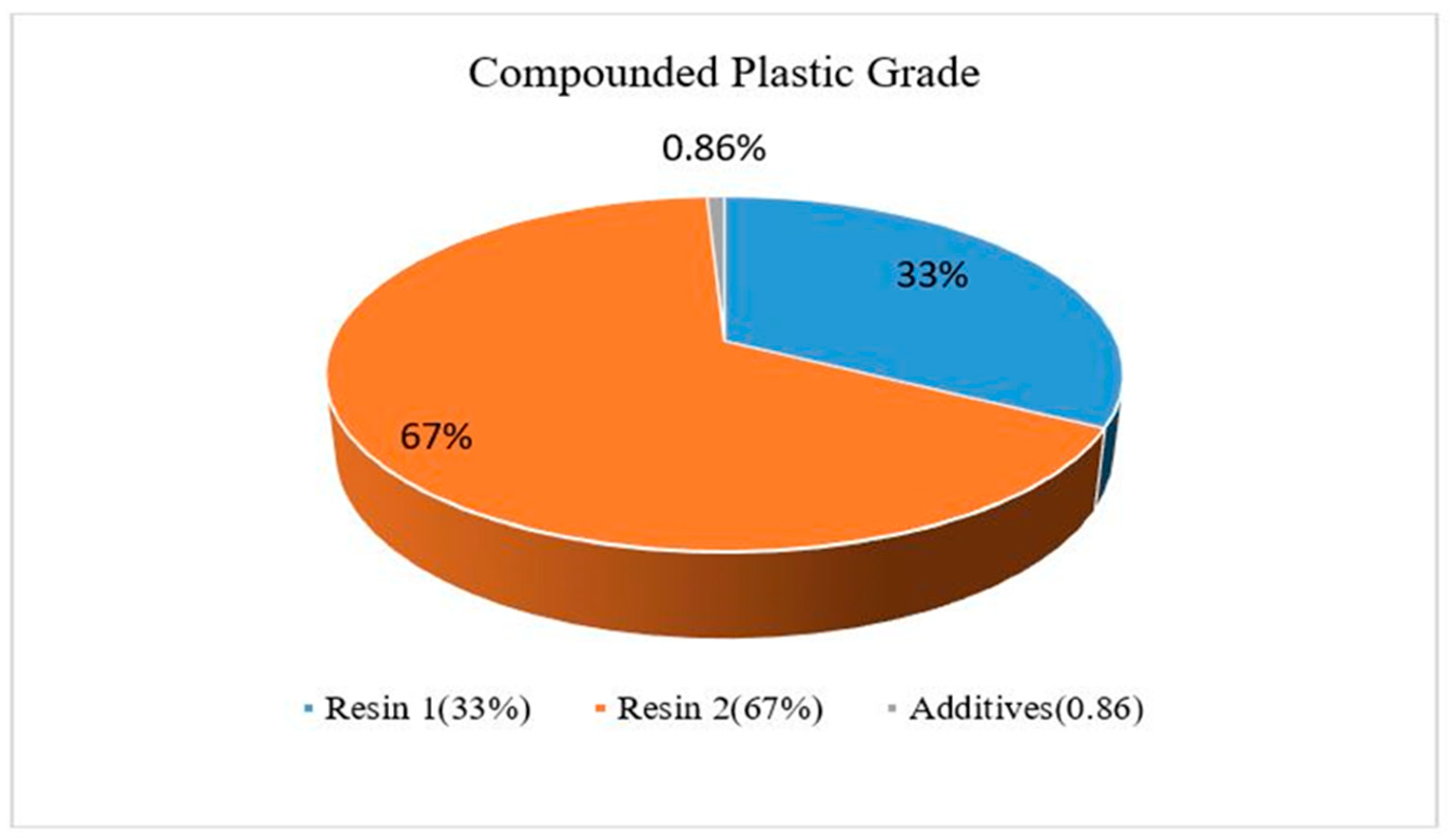

At the industrial plant, we carried out trials on the material under investigation. As detailed in

Table 1, a combination of various pigments and two PC resins was utilized, with these grades’ color formulation expressed in Parts per Hundred (PPH). A value of 6.5 g/10 min exhibited for Resin 2, whereas Melt-flow-index: MFI recorded at 25 g/10 min for Resin 1.

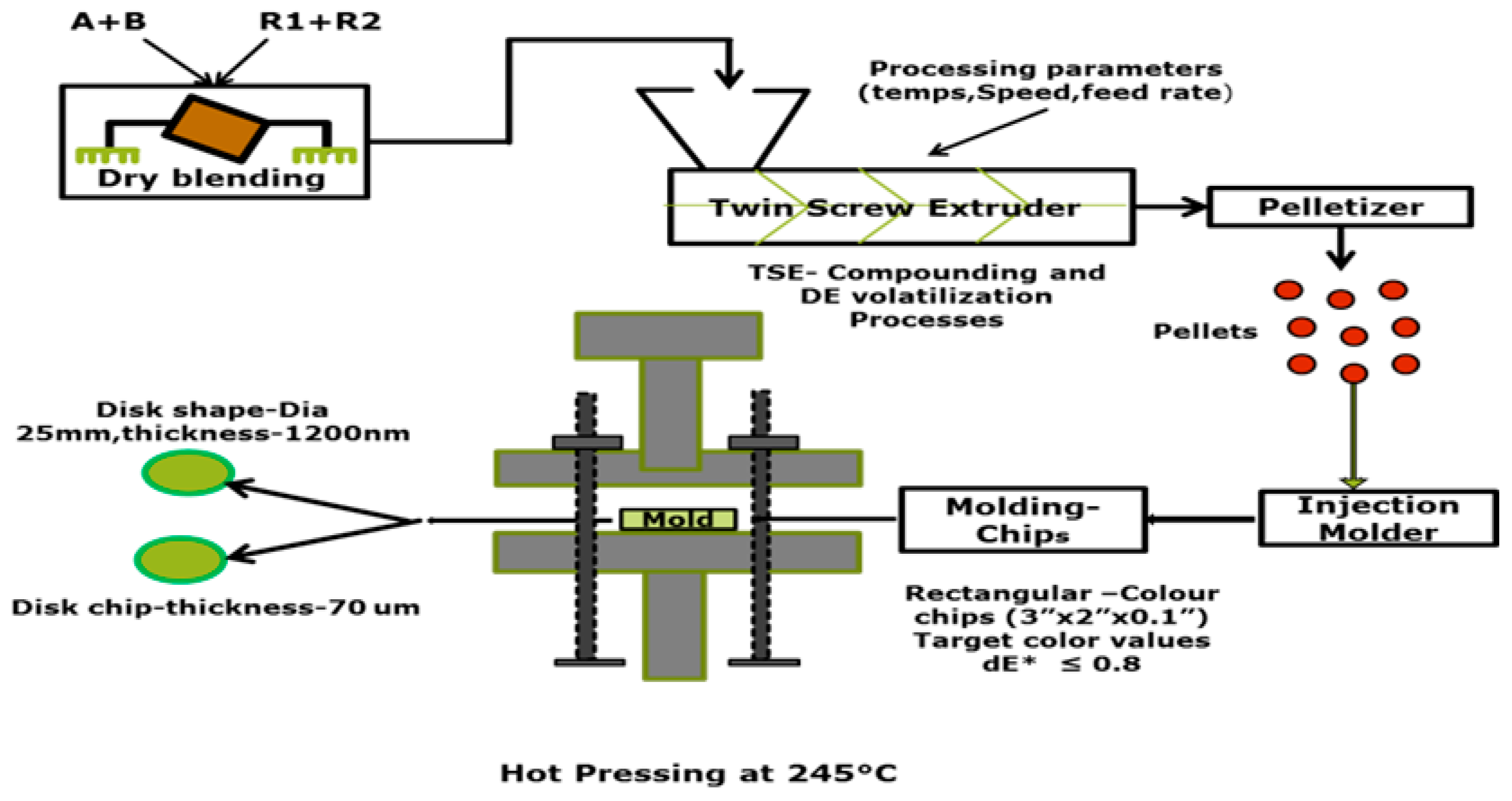

Given its 37:1 length-to-diameter ratio, 25.5 mm diameter, and a diameter (Do/Di ) ratio of 1.55, we ran the material extrusion process using a co-rotating (27-kW) Twin-Screw-Extruder (TSE): innovative intermeshing designs from Germany, ZSK26. Nine heating zones were located on the extruder's barrel while one was located at the die. After extruding the melt, we cooled it with cold water. Secondly, we allowed it to air dry, and thirdly, we pelletized it. Three rectangular chips measuring 3x2x0.1" were formed from the pellets from each run by injection molding. Then we used an American X-Rite spectrophotometer (CE: 7000A) to measure as well as (CIE L*, a*, b*)

In this case, L* = 70.04, a* = 3.41, and b* = 18.09 would produce the intended color result. We included three process parameters in the experimental design, as shown in

Table 2: extruder FRate, heating zone temperature, and screw speed. Utilizing the eighth version of American Design Expert Software (Stat-Ease, Inc.), we quantitatively assessed the data and established correlations among the variables at a 95% confidence interval through statistical analysis. To make sure the data stayed true to the target color, we optimized it numerically. We used a ratio of 100:0.86 to combine the resins and additives in

Figure 1. A super floater batch blender blends them according to weight ratios to make the mixture more consistent [

40,

41].

In the experimental design, the three different levels denoted by the code (-1, 0, and +1) for each element, as presented in

Table 2, assessed the same three process parameters. Both experimental designs took into account the utilization level in addition to the extruder FR, speed, and temperature, as indicated in

Table 2.

We prepared the batches using additives and pigments. Using the transparent PC grade material we created; we studied processing parameters and formulation's influence on changes in the final appearance of color and characteristics. By examining these results as well as the roles played by the dispersion morphologies of the three processing parameters, we gained a better understanding of the factors that create color disparities.

Figure 2 displays a simplified flow diagram that illustrates the steps involved in the compounding process. This illustration highlighting the relationships between various parameters and their impact on the final product's color and characteristics. By visualizing these connections, we can better understand how adjustments in processing can lead to different outcomes.

2.1. The Effects of Processing Parameter Interactions

The production of an accurate color through injection necessitates an appropriate operational procedure because the color variations will be affected by any changes in the processing parameters. The present study employed a systematic approach to manipulate the operational factors in order to examine their impact on pigmentation. We independently modified, (the speed, the rate of flow (FRate) & temperature) processing parameters across three separate stages. We noted when we held all other variables constant, we found that coloration was significantly correlated with the processing parameters. The experiments were conducted in the following manner: The recommended processing conditions included a steady speed (750 rpm) and an FR (25 kg/hr) and three distinct temperatures (280°C, 255°C & 230°C); then we repeat same processing for the speed and the rate of flow (FRate). This study utilizes two designs of the Response Surface Method (RSM).

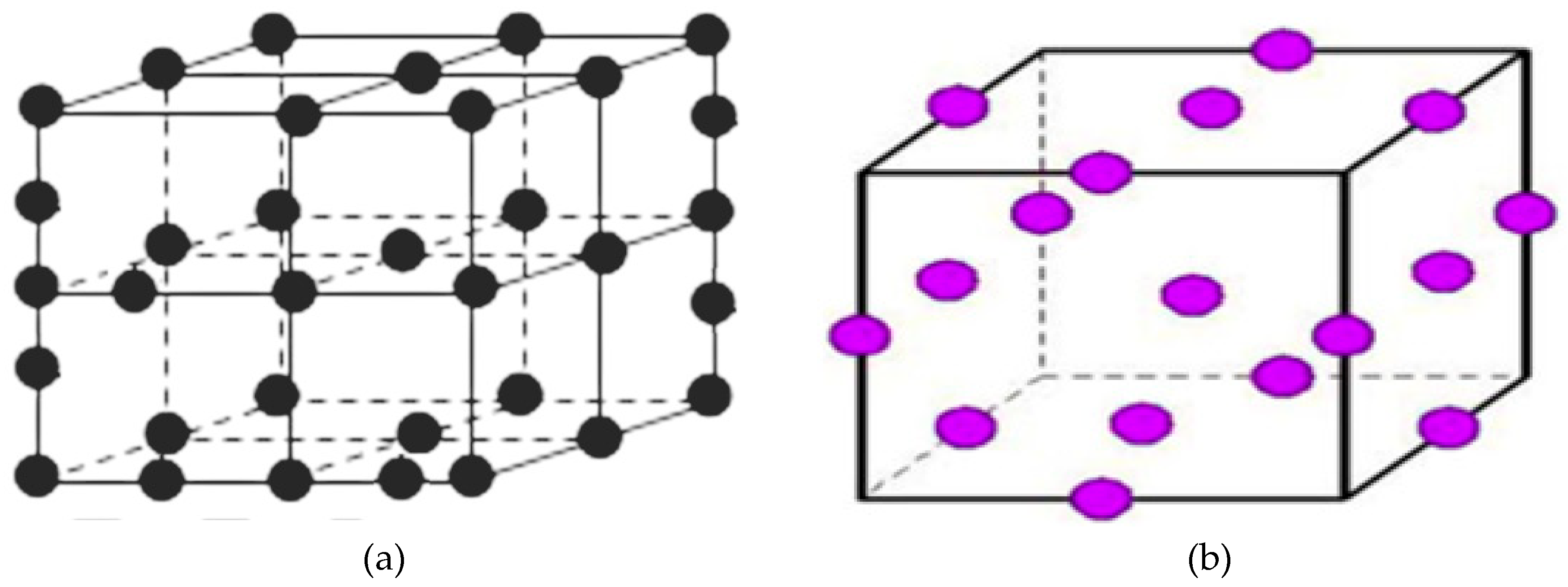

2.1.1. Three Level Full Factorial Design

A total of twenty-seven independent experimental runs make up the initial Design of Experiments (DOE), each with an additional five center points to accommodate differences in processing parameters. This results in a total of 32 treatments, as illustrated in Table 5 and

Figure 3a.

2.1.2. Box Behnken Design (BBD)

Table 6 and

Figure 3b display the second Design of Experiments (DOE). The second Design of Experiments (DOE) includes 12 experimental runs and five additional center points to accommodate various processing parameters, resulting in a total of 17 treatments. The experimental design took into account three process parameters: the extruder’s screw speed, FRate as well as the heating zones’ temperature, the extruder’s screw speed as well as FRate, with

Table 2 displaying the levels used. We varied the parameters on 12 different treatments. To see how they affected color, we added, for the BBD response method, five additional center points. Then, for the sake of detecting nonlinearity in the responses and estimating the experimental error, we added the additional five center points.We also recorded the percentage load during the experimental runs to calculate the specific mechanical energy (SME) using equation 3 [

42].

where: P: Power (kW); n

m: Max. Screw rotations (rpm); O: Load (%); n: Screw rotations (rpm); Q: FRate (kg/h).

The extruder’s screw speed, FRate as well as the heating zones’ temperature. Here, a control study has been conducted for examining the screw speed, FRate as well as temperature’s effects on color, as these factors directly influence it. We individually controlled three processing parameters at different stages. Here, we fixed the FR and temperature at middle values, and then we chose speeds of 700, 750, and 800 rpm. Then, we repeat the same procedure for the rate of flow (FRate) and temperature; our observation confirmed a significant color-processing variables correlation. We consider the above factors, which help us zero down on the best process parameters to make the plastic grade consistently colored [

43].

The study employs various scientific design techniques to minimize material rejects during the initial batch of color evaluations. Its primary objective is to investigate the interactions between FRate, temperature, screw speed, and trismillus color variants, as well as the processing conditions' effects. To maximize our processing parameters’ effect, we employes two experimental designs, and subsequently presented a statistical comparison of both designs. There are three steps to these statistical procedures study: Here we take a look at how color output and FR, temperature, and screw speed interact with one another. We compare the two designs using tools like ANOVA, overlay plots, and desirability graphs. This research examines the specific mechanical energy process in detail. We measured the colors in the experiments. We used MCT as well as SEM microscopes to examine pigments’ morphology in PC compounds. We also used them to look into the shape, dispersion quality, and color consistency-PC compound quality of pigments correlation.

Figure 1.

Typical compounding plastic color grade of polycarbonate.

Figure 1.

Typical compounding plastic color grade of polycarbonate.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of process methods of plastic.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams of process methods of plastic.

Figure 3.

(a) Three Level Full Factorial Design, (32 runs). (b). Box Behnken Design (17 Runs).

Figure 3.

(a) Three Level Full Factorial Design, (32 runs). (b). Box Behnken Design (17 Runs).

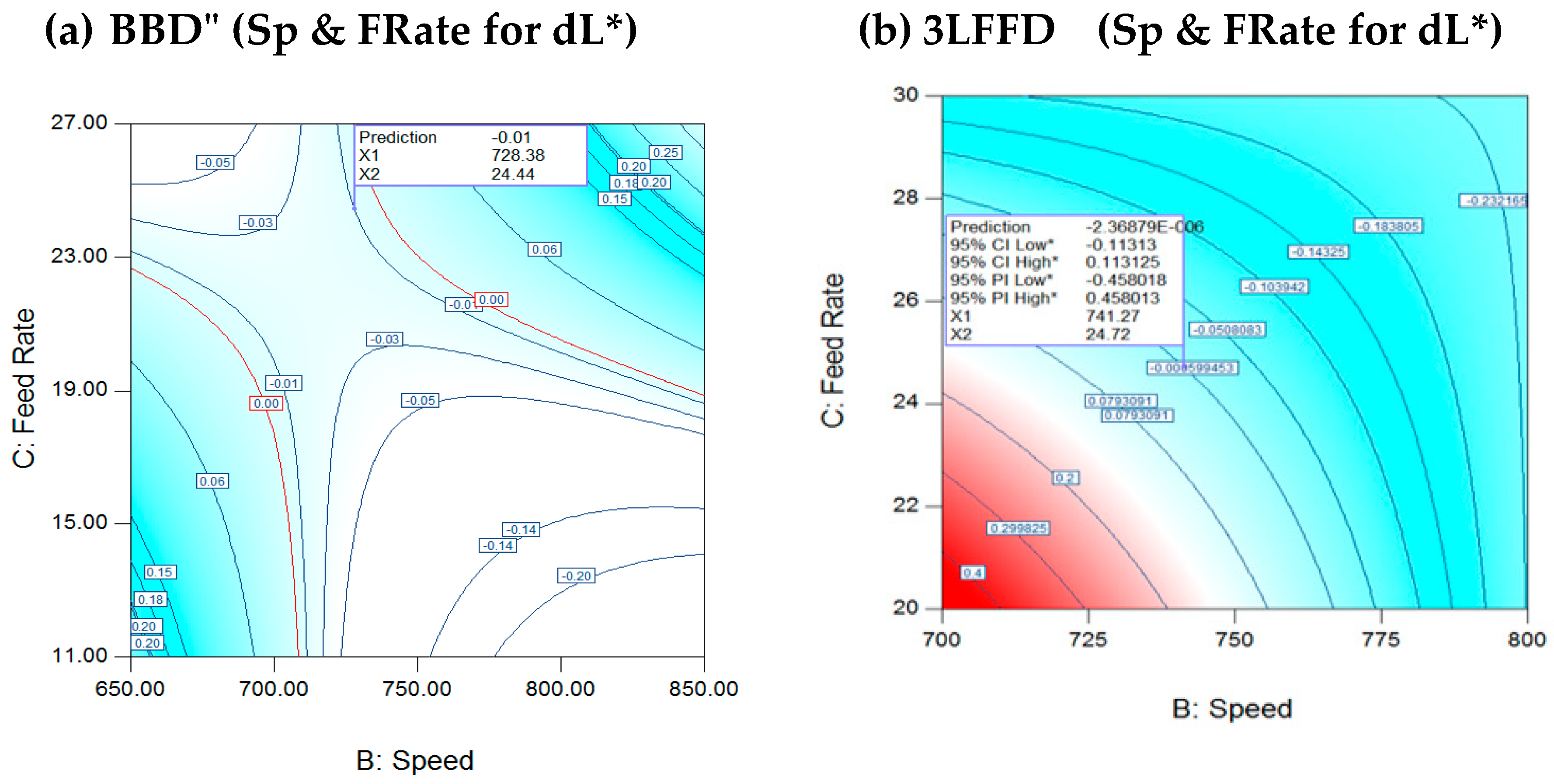

Figure 4.

(a) Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at (a) 274.23 oC for dL*, (b) 3LFFD at 245.2 oC for dL*.

Figure 4.

(a) Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at (a) 274.23 oC for dL*, (b) 3LFFD at 245.2 oC for dL*.

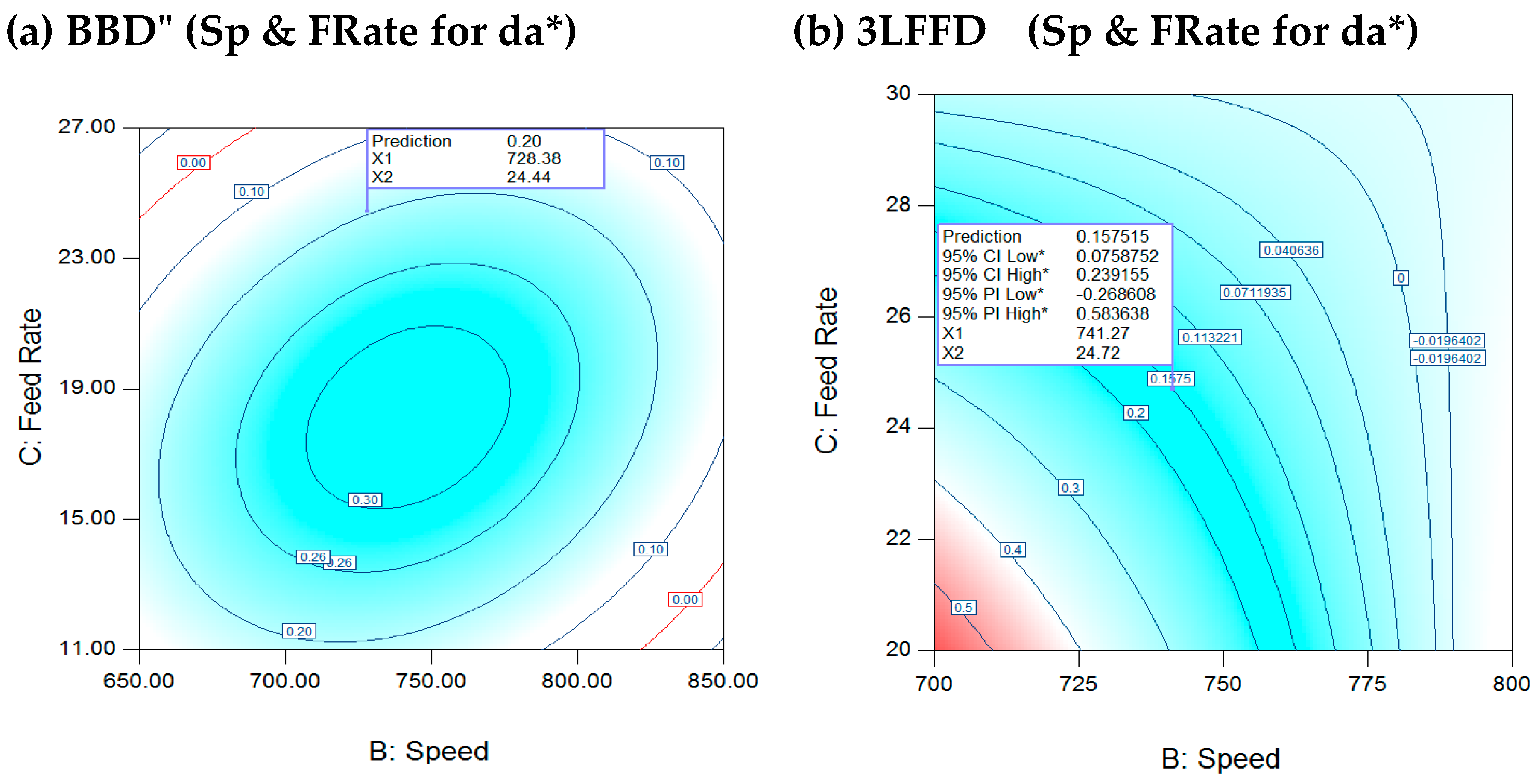

Figure 5.

(a): Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at 274.23oC for (da*), (b) 3LFFD at 245.2oC for (da*).

Figure 5.

(a): Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at 274.23oC for (da*), (b) 3LFFD at 245.2oC for (da*).

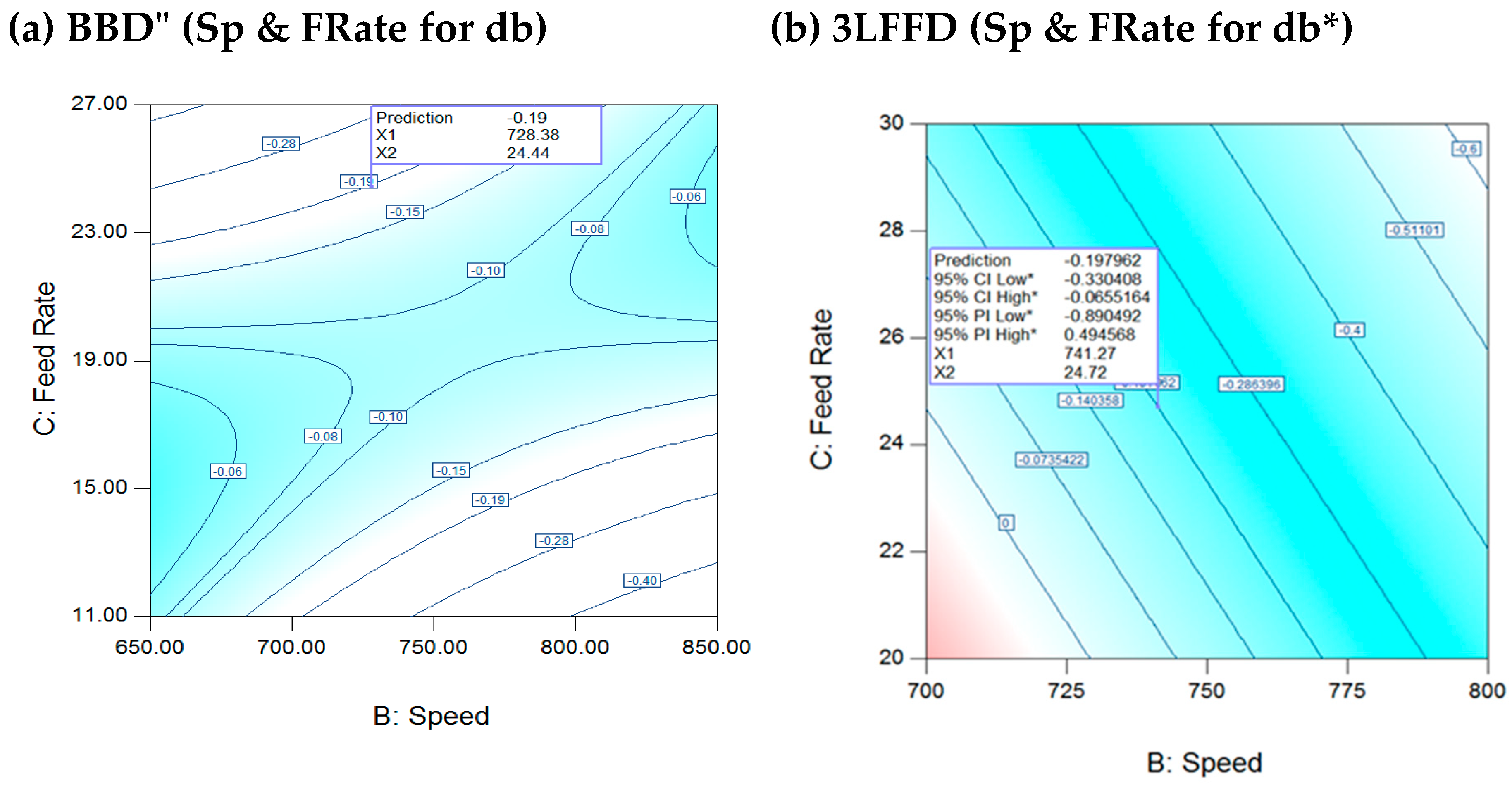

Figure 6.

(a): Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at 274.4 oC for db*, (b): 3LFFD at 245.2 oC for db*.

Figure 6.

(a): Interaction Sp & FRate for BBD at 274.4 oC for db*, (b): 3LFFD at 245.2 oC for db*.

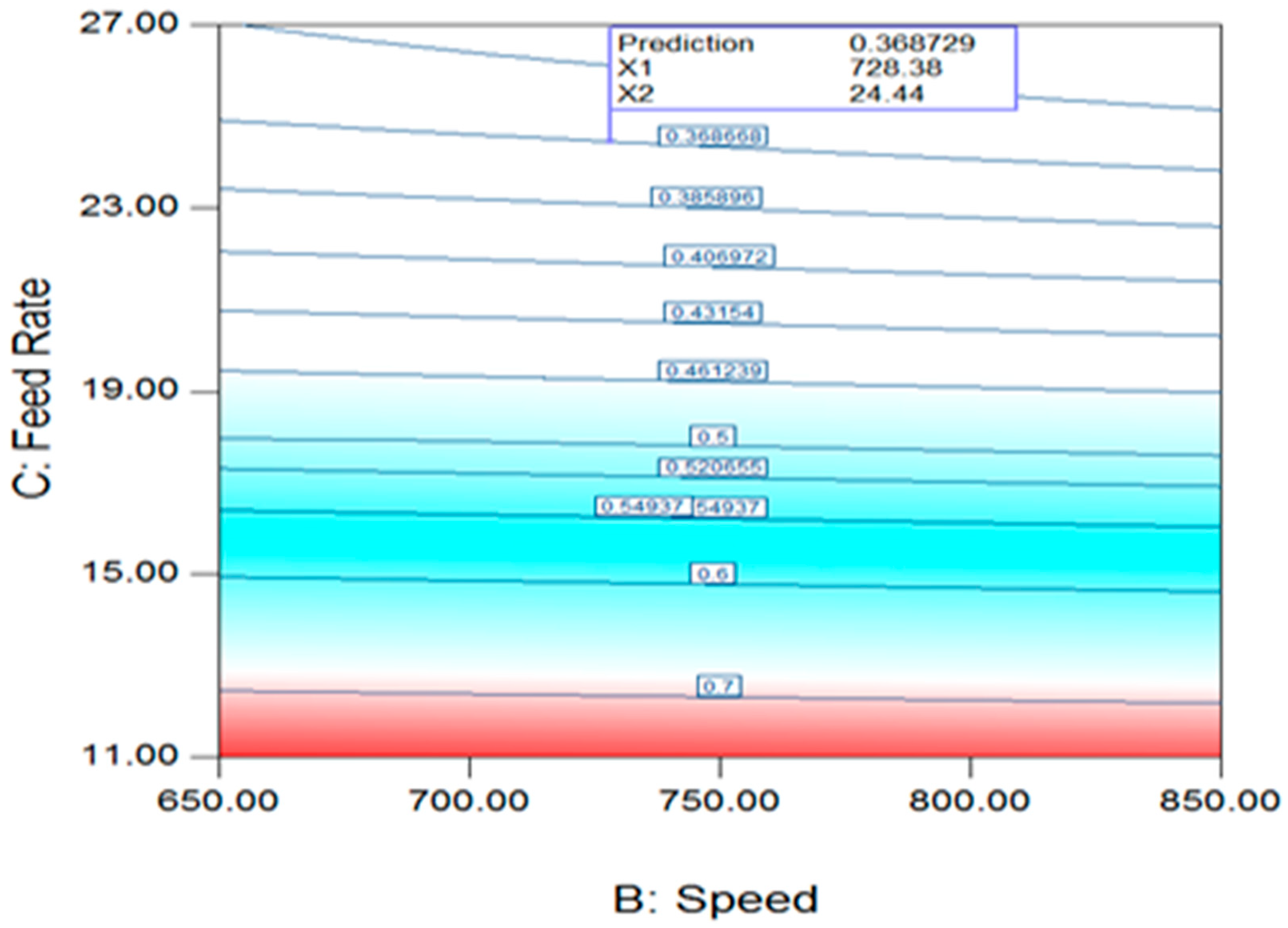

Figure 7.

SME’ plot: (at 274.23oC and 728.38 rpm).

Figure 7.

SME’ plot: (at 274.23oC and 728.38 rpm).

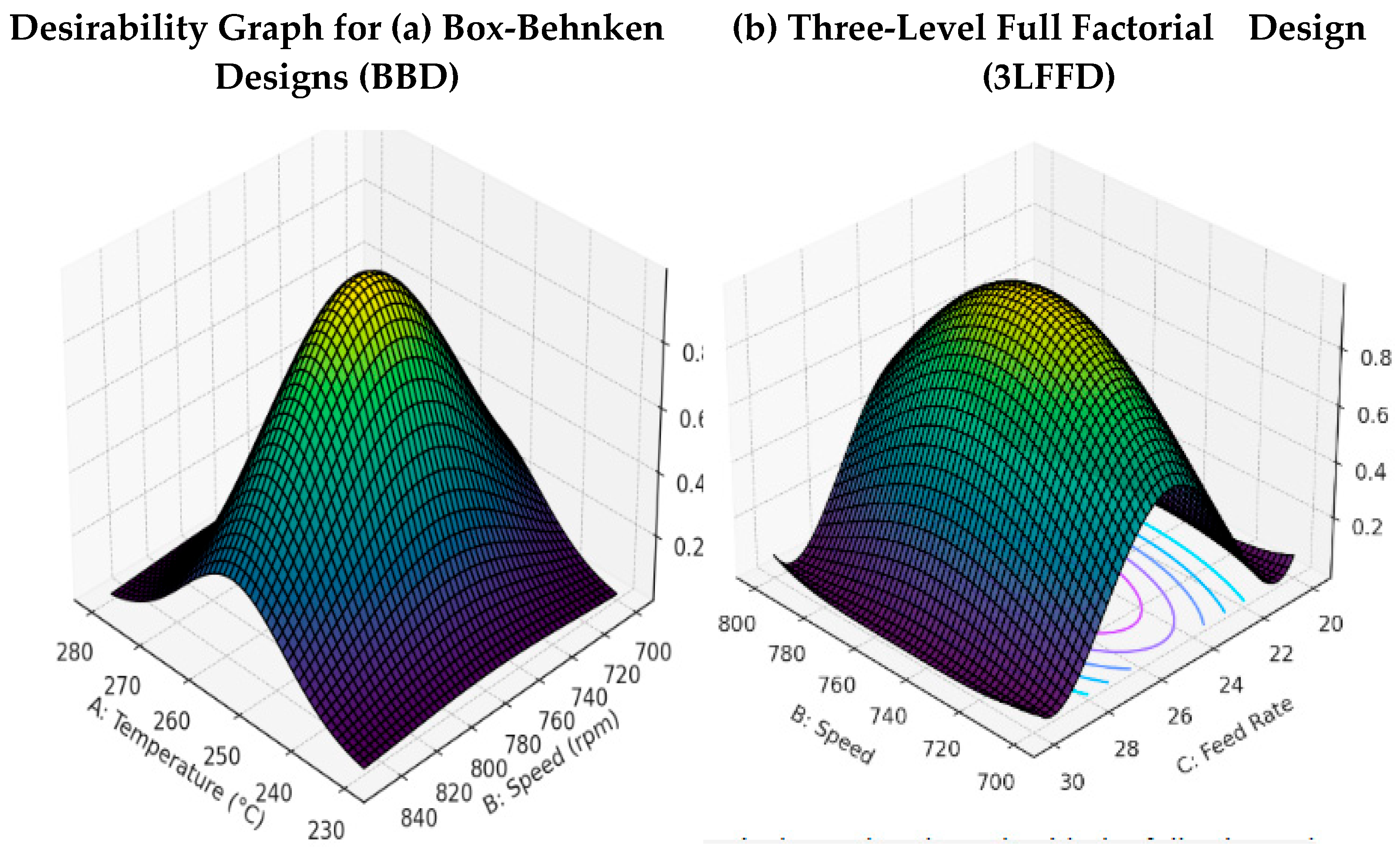

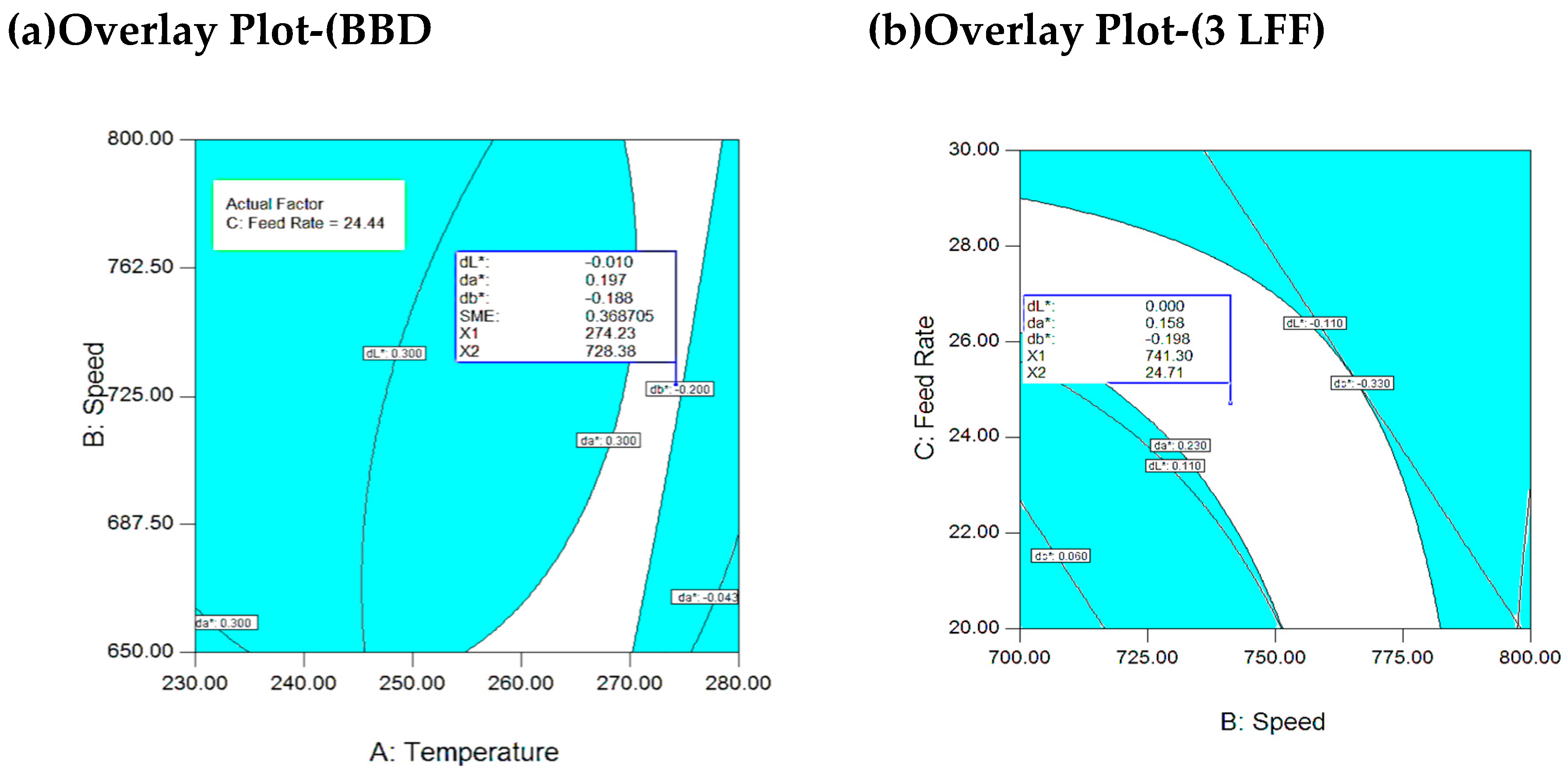

Figure 8.

(a) Desirability at 24.44 kg/hr FRate, (b) Desirability Graph at 245.2 oC Temp. A= T; B= Sp, C= FR.

Figure 8.

(a) Desirability at 24.44 kg/hr FRate, (b) Desirability Graph at 245.2 oC Temp. A= T; B= Sp, C= FR.

Figure 9.

(a): Temp-speed contour plot (FRate = 24.44 kg/hr), (b): Speed-FRate Contour plot: at (245.2 oC).

Figure 9.

(a): Temp-speed contour plot (FRate = 24.44 kg/hr), (b): Speed-FRate Contour plot: at (245.2 oC).

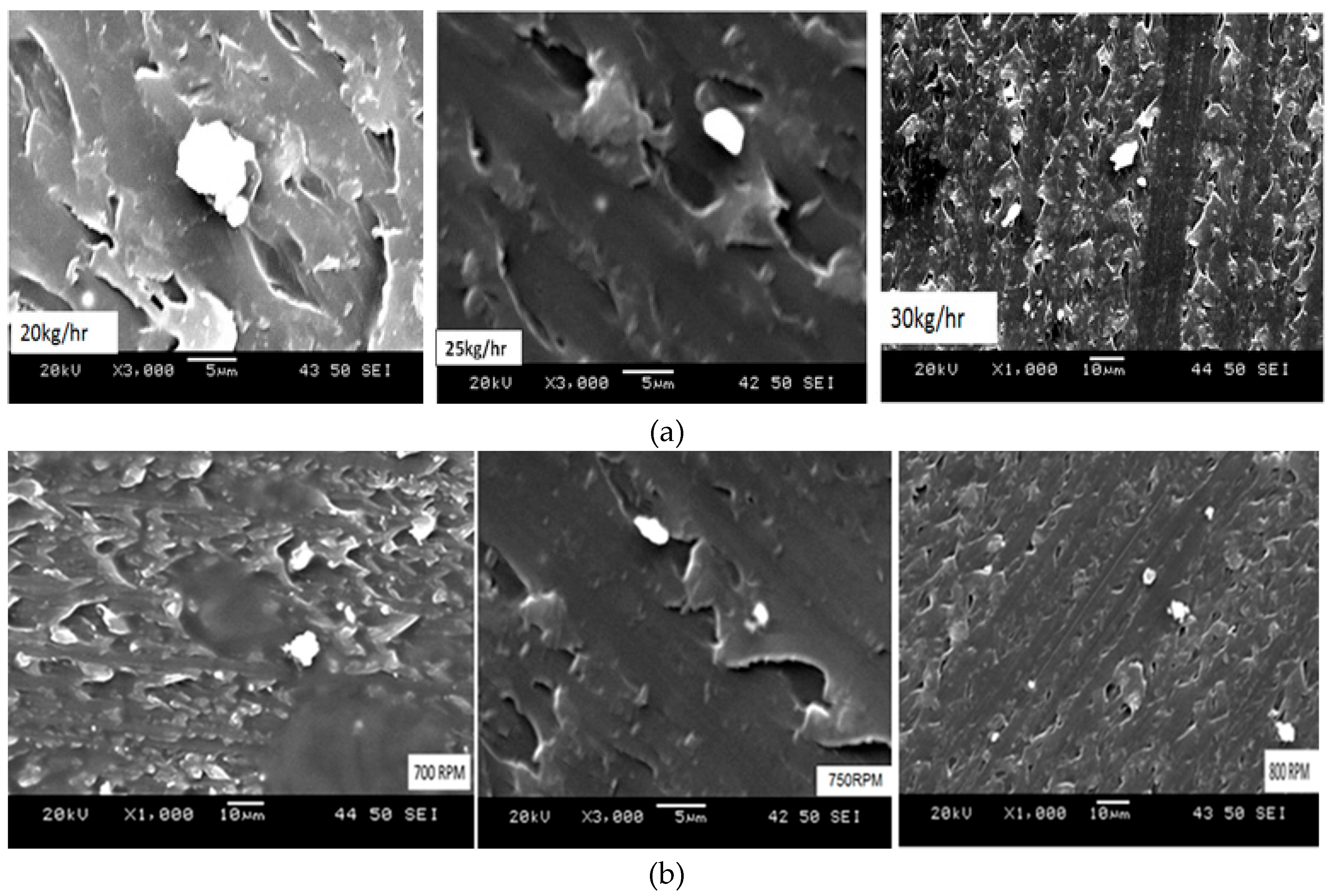

Figure 10.

(a): SEM agglomeration Micrographs for variation of Feedrate; (b): SEM agglomeration Micrographs for variation of Speed.

Figure 10.

(a): SEM agglomeration Micrographs for variation of Feedrate; (b): SEM agglomeration Micrographs for variation of Speed.

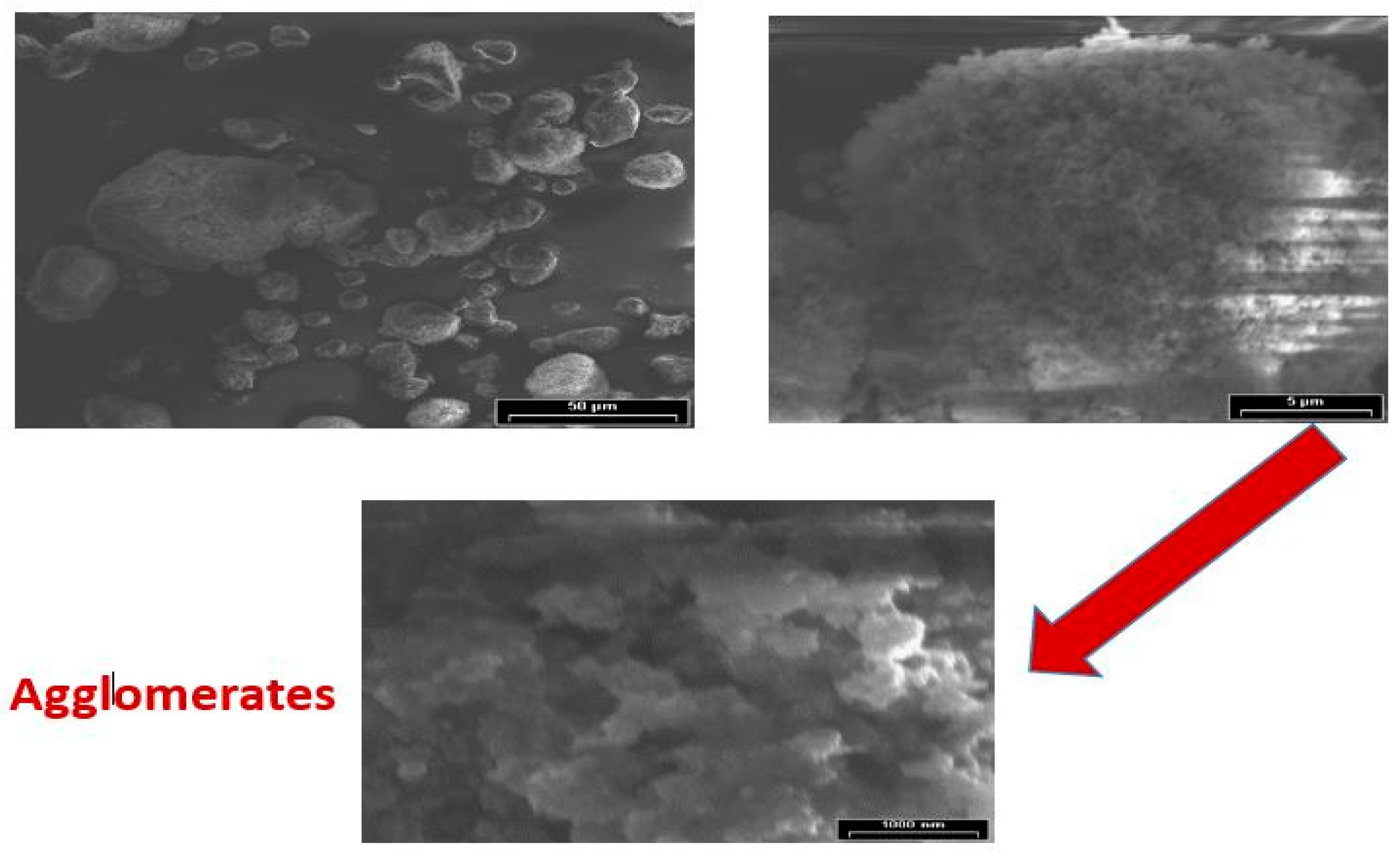

Figure 11.

SEM micrograph of raw pigments - Red, 3000X (Agglomerations’).

Figure 11.

SEM micrograph of raw pigments - Red, 3000X (Agglomerations’).

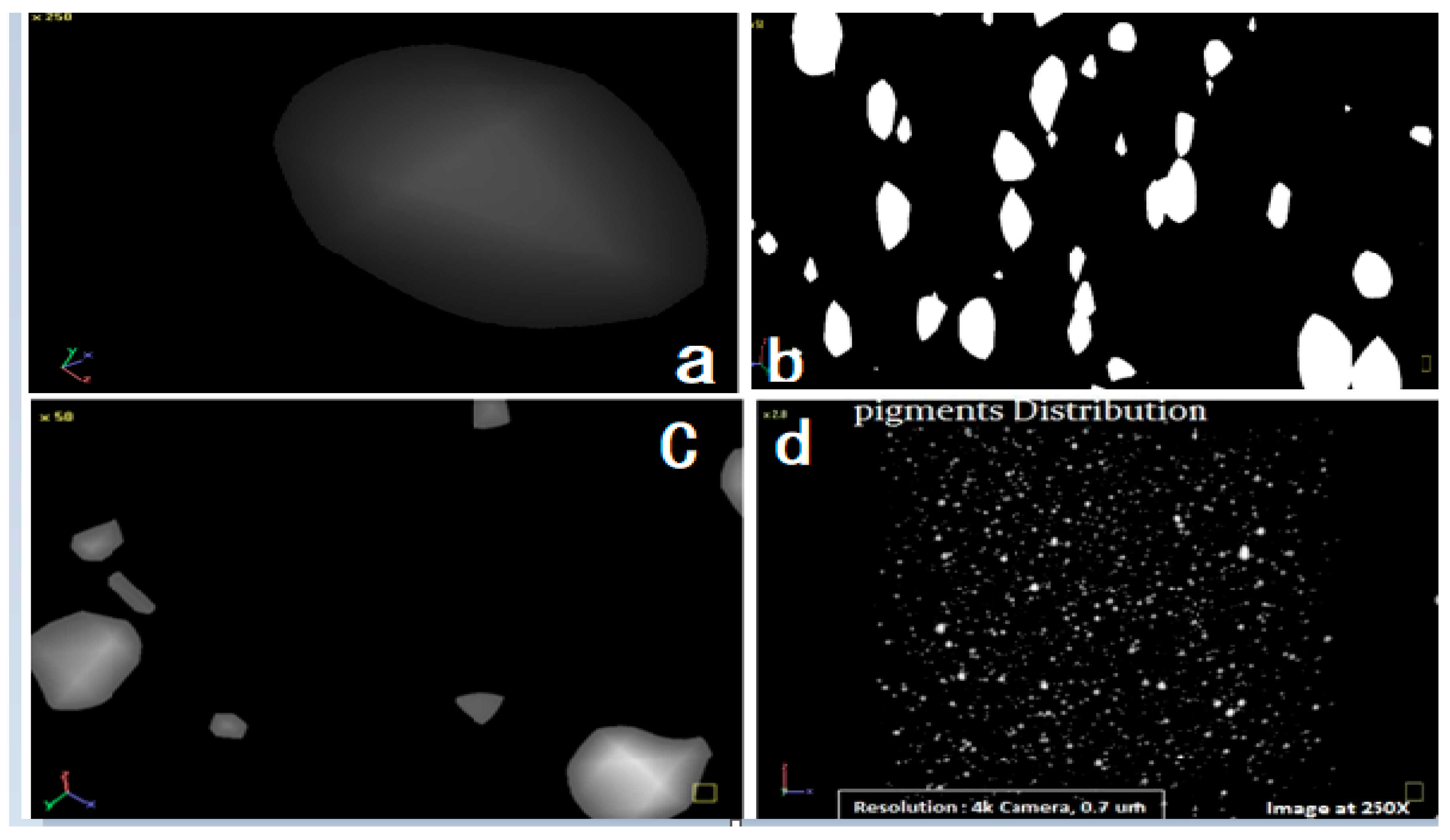

Figure 12.

Micro CT micrographs of PC grade at center point: (a) agglomerations image at 250 X, as well as. (b, c) particle shape (d) pigment distribution,

Figure 12.

Micro CT micrographs of PC grade at center point: (a) agglomerations image at 250 X, as well as. (b, c) particle shape (d) pigment distribution,

Table 1.

Various pigments & two PC resins / Color formulation.

Table 1.

Various pigments & two PC resins / Color formulation.

| (S#) |

(Type) |

(PPerHundred) |

| #1 |

Resin1 |

33.0 |

| #2 |

Resin2 |

67.0 |

| #3 |

PigmentA |

00.20 |

| #4 |

PigmentB |

00.05 |

| #5 |

PigmentC |

00.0004 |

| #6 |

PigmentD |

00.0016 |

| #7 |

PigemntE |

00.0710 |

Table 2.

Experimental design level and parameters for BBD and 3LFFD.

Table 2.

Experimental design level and parameters for BBD and 3LFFD.

| Design Models |

Units |

3 Levels |

| -1 |

0 |

+1 |

| 3LFFD |

Temp-°C |

230 |

255 |

280 |

| BBD |

230 |

255 |

280 |

| 3LFFD |

Speed -rpm |

700 |

750 |

800 |

| BBD |

650 |

750 |

850 |

| 3LFFD |

F.Rate-kg/h |

20 |

25 |

30 |

| BBD |

11 |

19 |

27 |

Table 3.

(ANOVA) Testing the hypothesis that RSM Used with da*, db*, dL*, & SME.

Table 3.

(ANOVA) Testing the hypothesis that RSM Used with da*, db*, dL*, & SME.

| (Response) |

(Significant Terms) |

(R2) |

(Predicted R2 ) |

(Adjacent R2) |

(Adequate

Precision)

|

| BBD |

(dL*) |

BC, B2 , C, B, A |

0.940 |

0.840 |

0.910 |

17.420 |

| 3LFFD |

C, B, A, AB, BC, AC |

0.780 |

0.380 |

0.550 |

0.550 |

| BBD |

(da*) |

C, B, A, C2, , B2, A2, AC, BC |

0.980 |

0.890 |

0.970 |

27.80 |

| 3LFFD |

C, B, BC |

0.750 |

0.240 |

0.390 |

8.530 |

| BBD |

(db*) |

C, B, A, B2, A2, BC |

0.720 |

0.400 |

0.560 |

5.620 |

| 3LFFD |

B, C |

0.750 |

0.280 |

0.300 |

8.610 |

| SME |

C, B, A, A2, C2

|

0.990 |

0.970 |

0.930 |

106.0 |

Table 4.

(da*, db*, dL*, & SME) Regression Model.

Table 4.

(da*, db*, dL*, & SME) Regression Model.

| (Response) |

(Regression Model) |

| (dL*) |

(BBD) |

+12.34563 - 0.011717 * T - 0.018803 * Sp - 0.22115 * FRate + 3.09375E-004 * Sp * FRate + 8.38889E-006 * Speed2 |

| (3LFFD) |

+63.86390 - 0.19647 * T -0.065085 * Sp - 0.99472 * FRate +1.84353E-004 * T * Sp +1.96624E-003 * T * FRate + 6.39611E-004 * Sp * FRate |

| (da*) |

(BBD) |

-34.33712 + 0.20508 * T + 0.024262 * Sp + 0.069289 * FRate - 2.16667E-004 * T * FRate + 1.20833E-004 * Sp * FRate - 4.07867E-004 * T2 - 1.78250E-005 * Sp2 - 2.74609E-003 * FRate2 |

| (3LFFD) |

+14.59778 - 0.018496 * Sp - 0.47296 * FRate + 5.98224E-004 * Sp * FRate |

| (db*) |

(BBD) |

-19.24168 + 0.18004 * T -5.00208E-003* Sp - 0.077943 * FRate + 2.52083E-004 * Sp * FRate-3.66316E-004 * T2 - 2.86116E-003 * FRate2 |

| (3LFFD) |

+4.08697 - 4.78866E -003 * Sp - 0.029746 * FRate |

| (SME) |

+2.72593 - 9.00716E-003 * T - 6.00329E-005 * Sp -0.077916 * FRate + 1.64940E-005 * T2 + 1.37360E-003 * FRate2 |

Table 7.

Optimized Processing Parameters and Corresponding Desirable Color Outputs.

Table 7.

Optimized Processing Parameters and Corresponding Desirable Color Outputs.

| Design Methodology |

Significant Processing Parameters |

Optimized Parameters |

Number

of Runs |

Desirability |

Color output dE* |

| dL* |

da* |

db* |

Temp |

Speed |

FRate |

|

% |

|

|

0C-A |

rpm-B |

Kg/hr-C |

|

|

|

| BBD |

A,C,BC, B2

|

B2 A2 C2 , AC, A, BC |

BC, A, A2 C2

|

274 |

728 |

24.4 |

17 |

87 |

0.26 |

| 3 LEVEL |

C, B, A, AB, BC, AC |

BC, B, C |

B, A |

255.7 |

734 |

24.4 |

32 |

77 |

0.25 |

| Core differences |

B |

BC |

BC |

18.3 |

6 |

0.0 |

15 |

10 |

0.01 |