1. Introduction

Anxiety and depression are distinct psychiatric disorders with an overlap of symptoms between them [

1,

2]. Most published studies focused on later-life anxiety and depression, however a cross-sectional survey in United States of America revealed that the prevalence of depression in adolescents and young adults have raised and there is a growing number of depressed young adults who do not receive any mental health treatment [

3]. Recently, Villaume, Chen and Adam have reported that anxiety and depressive disorders affected approximately 40% and 33% of adults aged 18 to 39 years, respectively, compared with 20% and 16% of adults aged 60 years and older during the COVID-19 pandemic. After the pandemic period, levels declined for those aged 60 years and older but remained elevated for younger adults [

4]. Along with this data, anxiety and early-life depression, compared with later-life depression, is characterized by less agitation, hypochondriasis, as well as less somatic symptoms, leading to undiagnosed and underestimated prevalence of these mental conditions. Concomitantly, a strong association has been demonstrated between psychiatric comorbidity and episodic vertigo syndromes such as vestibular migraine, and Ménière’s disease in young adults [

5]. However, the emotional state and related somatic symptoms, as well as depression or anxiety specific motor symptoms, have been underscored by several recent studies.

Functional balance is essential to a variety of human goal-directed movements, and requires integrity of vestibular, visual and somatosensory systems. Abnormalities in any of these or a conflict of integration within the balance control system can result in the sensation of dizziness, imbalance, or vertigo [

5,

6]. Also, several studies reported that mismatched information between these inputs may also be related to other medical conditions, namely psychological comorbidities that impact the capacity for balance and orientation in space [

5,

7,

8,

9]. In fact, in healthy adults, movement is operated automatically under the control of brainstem and spinal cord, which requires a small amount of cognitive resources [

10]. For example, standing on a moving bus while carrying a bag is a challenging balance task that may require involvement of higher cortical functions, such as attention and other executive functions. However, a few studies have demonstrated that this process may be affected by emotional states, due to a more complex process that leads to a higher involvement of cortical regions, and consequently to recruitment of greater cognitive resources [

5,

7,

8,

9]. When cognitive resources are exhausted, balance instability and falls may occur [

10].

Accordingly, Park et al. reported that depressive symptoms have a negative association with balance, revealing a lower body balance score in patients with higher symptoms of depression, that may be explained by the underlying neurobiological and pathological mechanisms of depression, where both emotional and motor systems are affected [

7]. Previously, similar findings were described by Cruz et al., who conducted a cross-sectional study, verifying that those patients with altered dynamic balance had a higher rate of negative emotional states compared to controls, specifically stress [

5]. Moreover, Redfern, Furman and Jacob were one of the first studies confirming a direct influence of anxiety in balance threat [

11], followed by recent evidence of related changes in all aspects of postural control, including standing, anticipatory, and reactive balance in anxiety disorders [

12,

13,

14]. Concomitantly, these results indicate that patients with anxiety disorders are more susceptible to postural control deficits and falls, revealing a decrease in amplitude and increase in frequency of center of pressure (COP) displacements during quiet standing. Additionally, higher anxiety levels seem to lead to progressive decreases in sway amplitude and increases in sway frequency [

15]. However, methodological differences in assessment of emotional state and balance can be limited by use of self-reported emotional state and different balance assessment approaches, conducting to limited evidence into this relationship.

Otherwise, different involvement of emotional processes, i.e., anxiety, depression, stress, panic disorder and others, determine the necessity of ongoing research to better understand the etiology beyond this relationship, which could help to develop vestibular rehabilitation that focuses on sensory re-integration processes, including processing sensory information that is significantly influenced by threat. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how emotional factors can influence balance control, as these changes have the potential to mask or modify underlying balance deficits.

Given the trends in prevalence of anxiety and depression in young adults in the last few years, and consequently the growing number of young people with untreated depression, we expected that anxiety and depression would influence balance in young adults without any clear physiological dysfunction. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the postural control in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra (approval number 108_CEIPC/2023) and all participants provided written and verbal informed consent. The study was conducted in the Audiology Laboratory of the Coimbra Health School.

2.1. Participants

A total of fifty young adults participated in the study, with an average age of 21.86 ± 2.6 years, of which 13 were males and 37 females. Briefly, exclusion criteria for the study were history of neuropsychiatric disease besides anxiety or depression, any other vestibular impairment, injury (including previous lower limbs surgery) or medication that possibly affects balance, and outer and middle ear pathologies.

2.2. Procedure

Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire, which included information on their demographic and clinical history, as well as their lifestyle.

HADS were developed by Zigmond and Snaith [

16], and there was a Portuguese version translated and validated by Pais-Ribeiro et al., that was used in this study [

17]. The scale is a self-administered instrument designed to provide clinicians with a reliable, valid, and user-friendly tool for identifying and quantifying symptoms of anxiety and depression. Initially it is intended to identify hospital patients who may require further psychiatric evaluation and intervention, however, nowadays it is broadly used in clinical practice as a tool to screen for anxiety and depression, rather than diagnose specific psychiatric disorders [

18]. Therefore, HADS were used to evaluate the severity of anxiety and depression, comprising 14 questions, scored from 0 to 3. Seven questions pertain to anxiety (maximum score of 21), and seven questions pertain to depression (maximum score of 21), with scores for each subscale between 0 to 7 indicating the absence of symptoms, and if the scores were between 8 to 10 indicating mild symptoms, a score of 11 to 14 indicating moderate symptoms; and a score of 15 to 21 indicating severe symptoms.

2.2.1. Evaluation of Postural Stability

Postural control was assessed using the mCTSIB. The evaluation was conducted on the Computerized Posturography platform NeuroCom, model Basic Balance Master System Version 8.2.0. The mCTSIB replicates the Sensory Organization Test by using a compliant foam pad instead of a sway-referenced forceplate. Timed measurements are taken using a stopwatch to provide scores. The test aims to identify abnormalities in the three sensory systems that contribute to postural control: somatosensory, visual, and vestibular.

Participants completed the mCTSIB assessment standing quietly on the forceplate, in four different sensory conditions: (1) firm surface, eyes Open (F/EO); (2) firm surface, eyes closed (F/EC); (3) foam surface, eyes open (FO/EO); and (4) foam surface, eyes closed (FO/EC). Participants were instructed to stand in each testing condition for 10s, with three trials conducted under each condition. The test was administered without shoes.

The mCTSIB variable of interest was the average sway velocity in each of the conditions and the sway index. This sway index represents the average of the mean sway velocity scores for all conditions. Further, sensory ratios were calculated for each participant. For the somatosensory ratio, the sway velocity of F/EC is divided by the sway velocity of F/EO, for visual, the sway velocity of FO/EO is divided by the sway velocity of F/EO, and for vestibular ratio, sway velocity of FO/EC is divided by the sway velocity of F/EO.

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to measure central tendency, including mean, median, maximum, minimum and standard deviation (DP) for continuous data, or N and percentage (%) for discrete variables. Correlations were assessed among variables using Pearson’s correlation coefficient test at a significance level of 0.05. P-values between 0.05 and 0.1 were considered marginally significant. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare results of postural control evaluation across levels of anxiety and depression.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The sample included fifty participants whose demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in

Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 21.86 (SD=2.63) years.

Of the fifty young adults who participated in the study, we noticed a higher participation of female gender (74%) as well as that only ten participants were employed. A lifestyle variable analyzed was physical activity, and when asked whether participant had some physical activity, 38% reported having participated in regular physical activity. Of the young adults included, 13 (26%) were smokers.

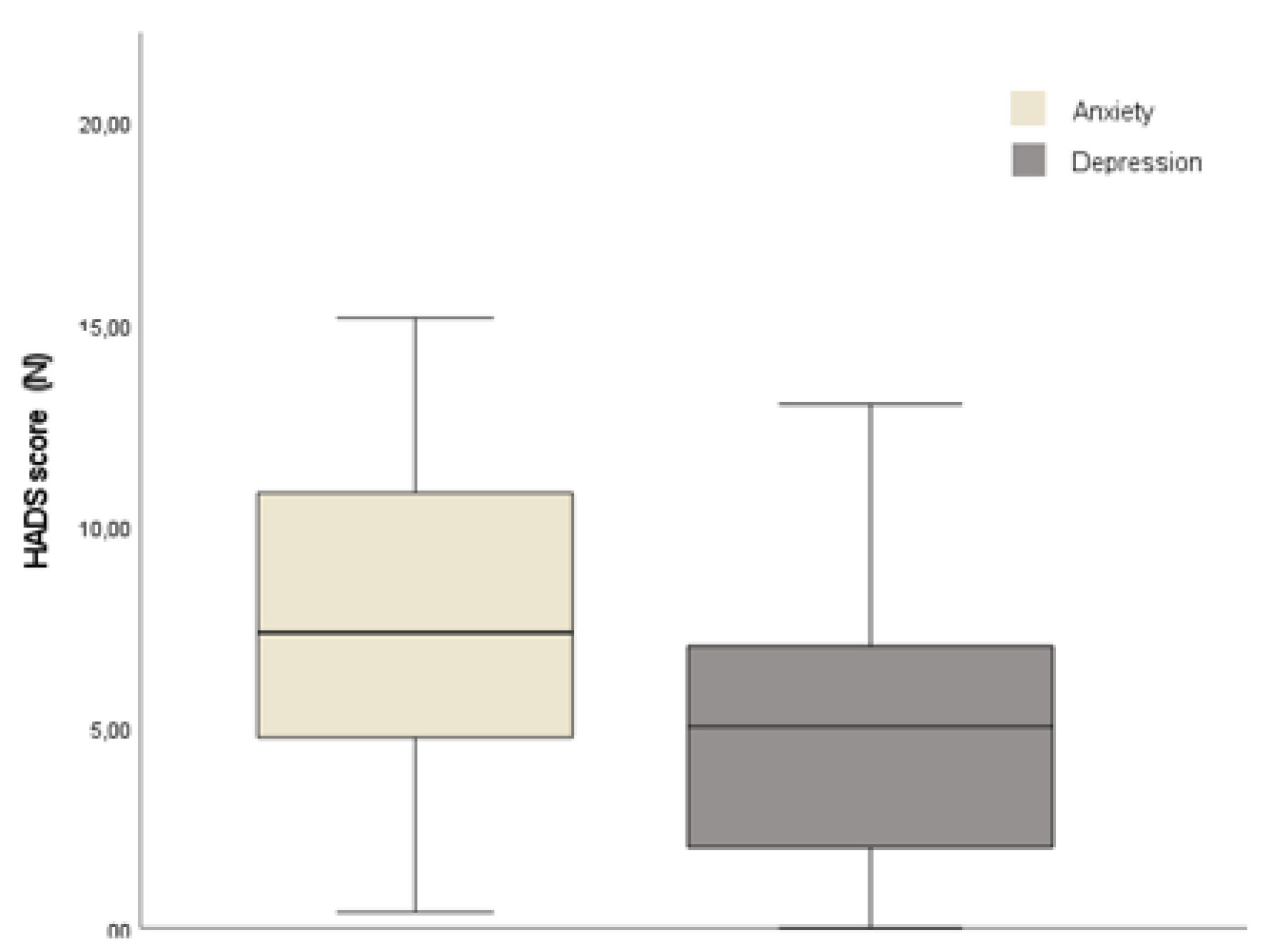

Mean HDAS – anxiety scores were above the cut-off of 8+ criterion for identifying cases of anxiety, indicating an anxiety prevalence of 62%, of whom 48.4% showed moderate symptoms. In detail, distribution of HDAS-anxiety score was 9 (SD 4.63; range 1-18). Instead, in depression subscale a mean of 5.26 (SD 3.44; range 0-13), as shown in

Figure 1. Concerning depression subscale scores, participants exhibit fewer and less severe depressive symptoms, as could be observed in

Table 2. Nonetheless, the results of Pearson’s correlation showed a moderate correlation with an increase in HDAS- anxiety scores and HDAS-depression scores (r= 0.608, p<0.001).

Correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationship between HDAS scores and demographic and clinical characteristics. Significant correlation was found exclusively between gender and anxiety (r=0.346, 9 = 0.0.14), with females being more anxious than males.

3.2. Postural Stability

Means for sway velocity for all mCTSIB conditions are reported in

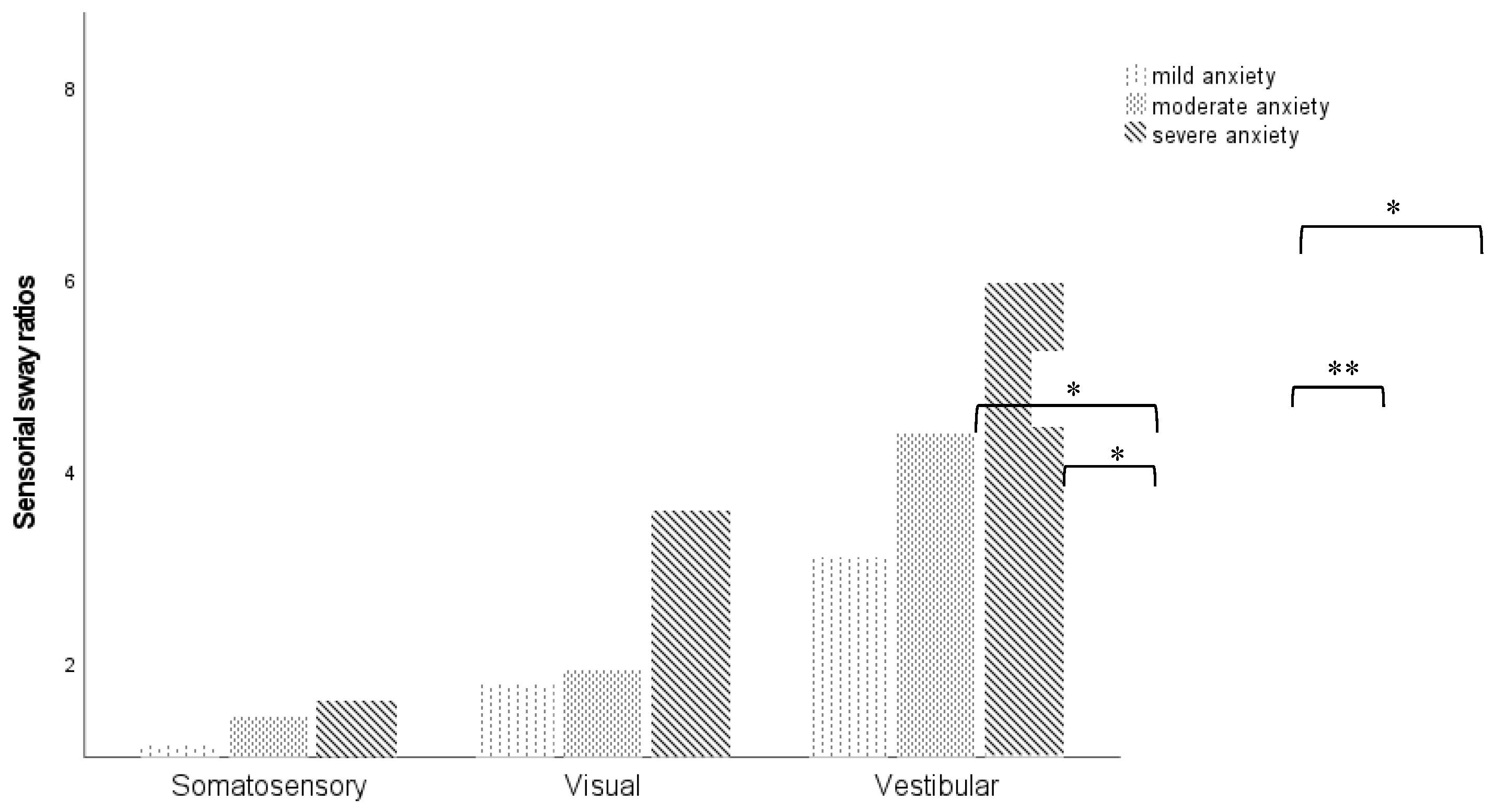

Table 3. As expected, sway velocity mean increased significantly (p<0.001) as a result of increasing task difficulty postural control, showing that participants had more difficulties in the eyes-closed standing on foam condition. However, Kruskall-Wallys analysis between anxiety levels and mCTSIB conditions revealed that sway postural control is significantly different between anxiety participants when visual and somatosensory cues are unavailable (FO/EO condition: mild vs severe anxiety, p=0.034, and moderate vs severe anxiety, p=0.011; FO/EC condition: mild vs severe anxiety, p= 0.027, and moderate vs severe anxiety, p=0.035).

Correlation analysis showed no significant correlation between HADS-anxiety scores and mCTSIB conditions (see

Table 4), as well as between HADS-depression scores and mCTSIB conditions and sway index. However, weak positive correlations between anxiety symptoms and somatosensorial ratio (r=0.28, p=0.048), and anxiety symptoms and visual ratio (r=0.28, p=0.05) were found. Participants exhibited a marginally significant correlation between anxiety and sway index (r=0.26, p=0.069). For depression subscale we did not find significant correlations.

Moreover, individuals who showed severe symptoms of anxiety reported a higher postural sway velocity for all sensory ratio, especially for visual (mild vs severe anxiety, p=0.042; moderate vs severe anxiety, p=0.019) and vestibular ratios (mild vs moderate anxiety, p= 0.071; mild vs severe anxiety, p=0.047), as shown in

Figure 2.

Among depression, mean values of sway velocity for sensory ratios were similar between participants. Analyzing the HDAS – depression scores and mCTSIB sensory ratios, no correlation was found.

Table 4 shows the correlation among variables.

4. Discussion

The present experiment explored whether emotional state, i.e. anxiety and depression, can influence static balance among young adults. First, it is important to notice that high levels of anxiety were identified in this population, with a prevalence of 62%. Villaume et al. had previously obtained similar results, concluding that young adults have higher levels of depression and anxiety than older adults [

4]. Hence, it is extremely important to evaluate emotional state across lifespan, and specifically in young adults, be aware of other comorbidities that may be the cause or caused by neuropsychiatric disorders.

Second, we expected that higher levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms would be associated with increased postural sway. Generally, young adults from our sample had reliable postural control, nevertheless we found a positive correlation between anxiety levels and sway index. These findings suggest that an increase in HADS-anxiety score is associated with higher sway index score, indicating a greater degree of instability and increased risk of fall.

Moreover, our findings from sensorial sway ratios revealed a positive association of anxiety and somatosensorial and visual ratios. Specifically, the higher the anxiety score on the HDAS, the greater the use of somatosensory or visual references, if visual or somatosensory cues, respectively, are removed. In comparison between anxiety levels, in unstable conditions of mCTSIB, were observed that higher scores of anxiety leads to more difficulties in postural control, especially when beside somatosensorial cues, visual cues are inaccurate. Therefore, anxiety seems to increase reliance on somatosensory and vision systems for balance due to a decreased ability to use vestibular feedback for balance. These results support the findings of Goto et al., who evaluated the effect of anxiety on the postural stability of 54 patients with dizziness and found that higher levels of anxiety are associated with larger postural sway. Furthermore, were identified that anxiety affects the interactions of visual on vestibular and somatosensory inputs in the maintenance of postural control [

19]. Although, these authors studied postural control in patients complaining of dizziness, with a significant effect of the vestibular perturbation.

Furthermore, the diminished performance of postural control may be explained by changes in postural threat, i.e. inaccurate visual or somatosensorial cues, leading to more anxiety and consequently affecting postural control measures. Therefore, we hypothesized that postural threat emerge as a consequence of higher anxiety related to the possibility of instability, such as may occur when there is a fear of falling. This interpretation is in line with the study of Hauck, Carpenter and Frank, who suggested that increased levels of threat and consequently of task difficulty led to decreased stability, while anxiety levels increased [

14]. Moreover, increased motor task difficulty may exert greater cognitive resources, as has been demonstrated previously by Khaya et al, that showed that challenging postural demand is associated with cognitive overload in healthy young adults. Therefore, if postural threat is mediated by anxiety, and knowing that anxious thoughts affect cognitive resources due to overloading [

6,

20], leading to competitive processes, these results may suggest that postural control is affected by anxiety due to overloaded cognitive resources in young adults. These findings are of clinical importance, namely due to the high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in the young population. Hence, Stins, Roerdink and Peek demonstrated that affective interventions can contribute to ameliorate postural control, which could be a potential tool to introduce in vestibular rehabilitation [

13].

Surprisingly, for depression no significant interaction was found, even considering that HADS subscales scores are significantly correlated. Considering that in our study young adults had fewer and less severe symptoms of depression, these results may be different if depression symptoms worse. In fact, Park et al. have shown that higher clinical risk for depression has a negative association with balance scores due to dopamine pathways’ dysregulation, which leads to motor symptoms specific to depression [

7]. Other study suggested that specifically dynamic balance is affected by emotional states, however other comorbidities and lifestyle are also appointed as a potential cause of balance dysfunction [

5]. In fact, in this study we compared HDAS scores and demographic and clinical characteristics, namely physical activity, and no association was found. However, Cruz et al. did not use an objective instrument to assess depression, which reduces the reliability and replication of their results.

While this study provides important preliminary evidence, it has some limitations. In fact, even considering that we have observed some significant differences or associations, these need to be interpreted with caution, given the relatively small sample size and small to moderate effect sizes. Furthermore, our study design, included both females and males, as well as individuals with no clinical complains. Future work should address the reliability of these results in patient populations.

5. Conclusions

Increased postural sway and consequently a greater degree of instability and increased risk of fall were associated with higher levels of anxiety, which reflects a higher dependence on somatosensory and vision system for maintaining postural control. Otherwise, depression symptoms seem to not influence postural control. This implication is in direct contradiction with extensive research that showed evidence that depression is detrimental to balance. We suggest that potential warms of anxiety are associated with increased levels of threat perceived due to decreased ability to use vestibular feedback for balance. Future work in this field will provide insight into this association and the reliability of these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and M.S.; methodology, M.S.; formal analysis, T.M., P.B. and M.S.; investigation, P.B.; resources, M.S.; data curation, T.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, T.M.; visualization, T.M.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra (approval number 108_CEIPC/2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| F/EO |

Firm/eyes open |

| F/EC |

Firm/eyes closed |

| FO/EO |

Foam/eyes open |

| FO/EC |

Foam/eyes closed |

| HADS |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| mCTSIB |

modified Clinical Test for the Sensory Interaction on Balance |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

References

- Hegeman, J.M., Kok, R.M.; van der Mast, R.C.; Giltay, E.J. Phenomenology of depression in older compared with younger adults: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 275-281.

- Nutt, D. Anxiety and depression: individual entities or two sides of the same coin? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2004, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.A.; Doan, J.B.; McKenzie, N.C.; Cooper, S.A. Anxiety-mediated gait adaptations reduce errors of obstacle negotiation among younger and older adults: Implications for fall risk. Gait Posture 2006, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villaume, S.C.; Chen, S.; Adam, E.K. Age disparities in prevalence of anxiety and depression among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, I.B.M.; Barreto, D.C.M.; Fronza, A.B.; Jung, I.E.C.; Krewer, E.C.; Rocha, M.I.U.M.; Silveira, A.F. Dinamic balance, lifestyle, and emotional states in young adults. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaya, M.; Liao, L.; Gustafson, K.M.; Akinwuntan, A.E.; Manor, B. Sensors 2022.

- Park, J.; Lee, C.; Nam, Y.E.; Lee, H. Association between depressive symptoms and dynamic balance among young adults in the community. Helyon 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahya, M.; Wood, T.A.; Sosnoff, J.J.; Devos, H. Increased postural demand is associated with greater cognitive workload in healthy young adults: a pupillometry study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Momani, M.; Al-Momani, F.; Alghadir, A.H.; Alharethy, S.; Gabr, S.A. Factors related to gait and balance deficits in older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2016, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Salihu, A.T.; Usman, J.S.; Hill, K.D.; Zoghi, M.; Jaberzadeh, S. Mental fatigue does not affect static balance under both single and dual task conditions in young adults. Exp Brain Res 2023, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfern, M.S.; Furman, M.S.; Jacob, R.G. Visually induced postural sway in anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 2007, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.J.; Zaback, M.; Tokuno, C.D.; Carpenter, M.G.; Adkin, A.L. Exploring the relationship between threat-related changes in anxiety, attention focus, and postural control. Psychol. Res. 2019, 445–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stins, J.F.; Roerdink, M.; Peek, P.J. To freeze or not to freeze? Affective and cognitive perturbations have markedly different effects on postural control. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2011, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauck, L.J.; Carpenter, M.G.; Frank, J.S. Task-specific measures of balance efficacy, anxiety, and stability and their relationship to clinical balance performance. Gait Posture 2008, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkin, A.L.; Carpenter, M.G. New insights on emotional contributions to human postural control. Front. Neurol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S. , Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro. J., Silva, I., Ferreira, T., Martins, A., Meneses, R., Baltar, M. Validation study of a Portuguese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psychol Health Med 2007, 225-237.

- Herrmann, C. International Experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997, 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, F.; Kabeya, M.; Kushiro, K.; Ttsutsumi, T.; Hayashi, K. Effect of anxiety on antero-posterior postural stability in patients with dizziness. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarigiannidis, I.; Kirk, P.A.; Roiser, J.P.; Robinson, O.J. Does overloading cognitive resources mimic the impact of anxiety on temporal cognition? J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2020, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).