Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

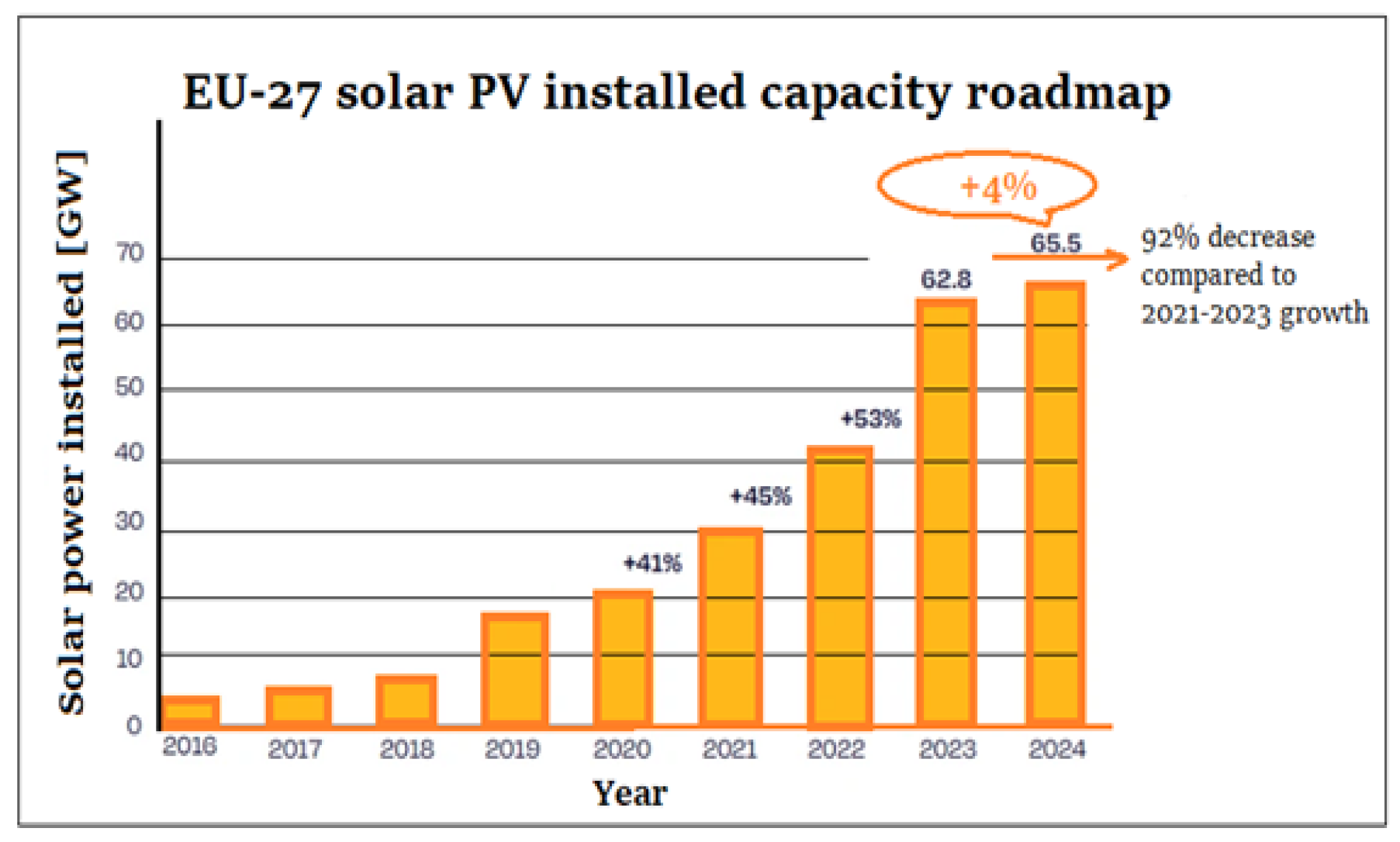

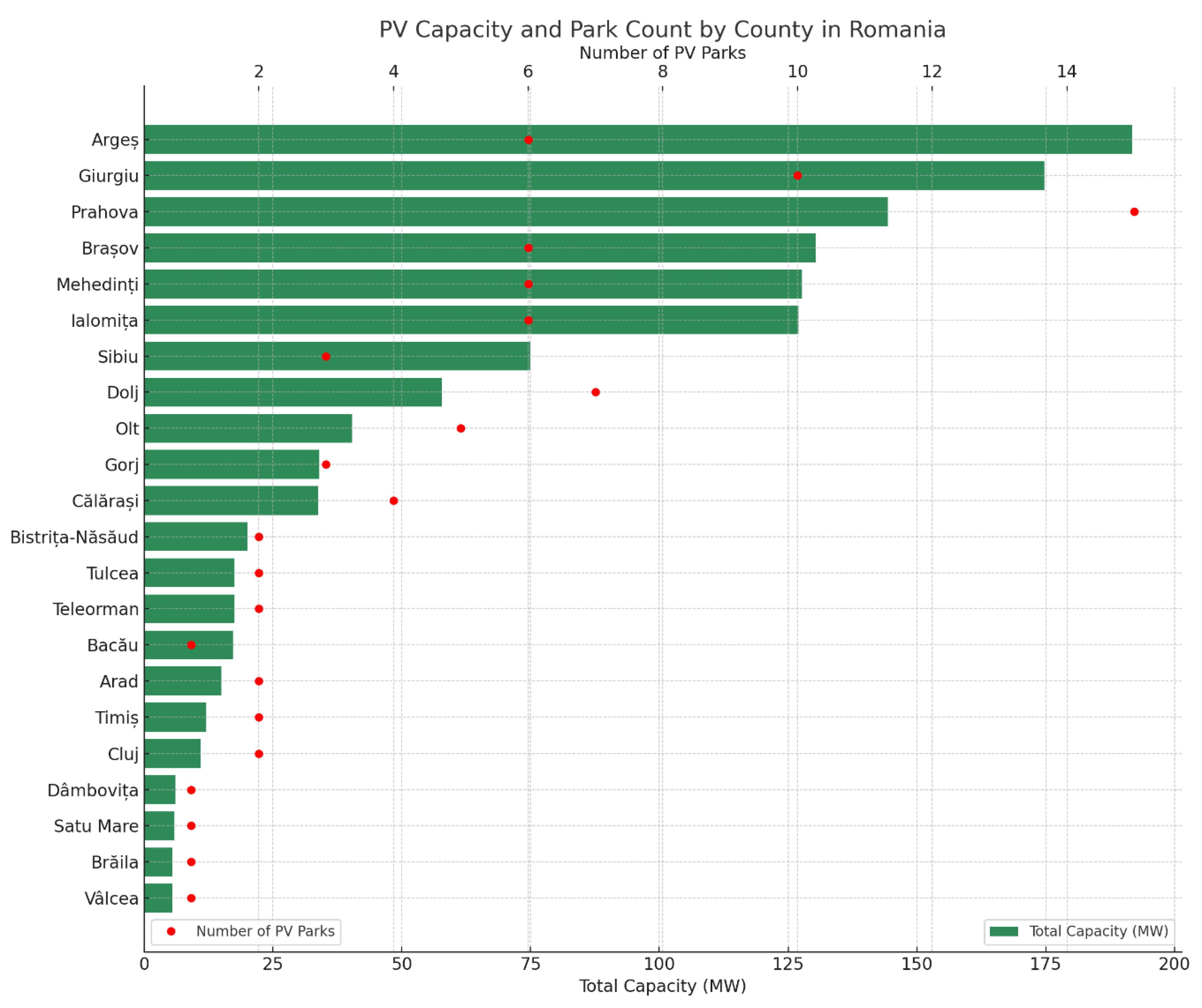

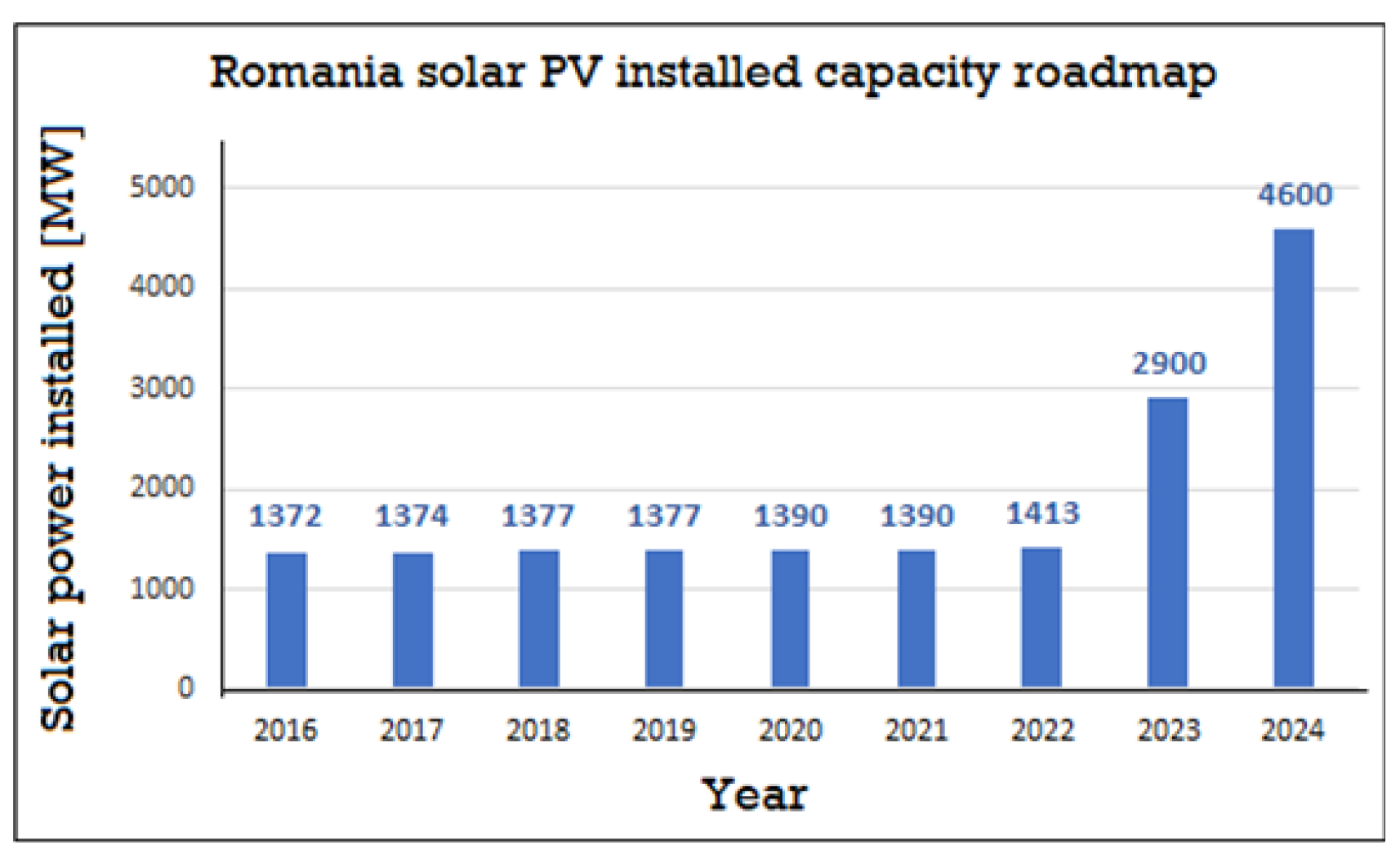

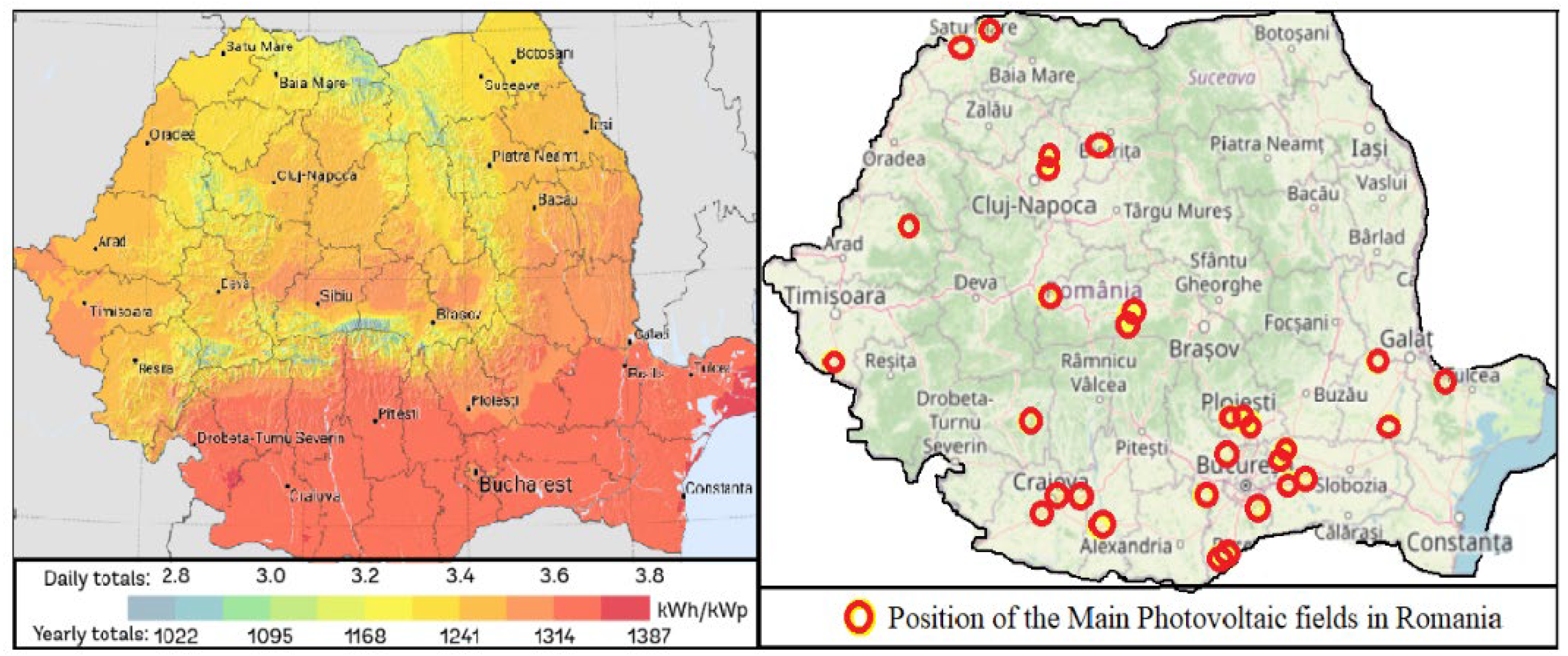

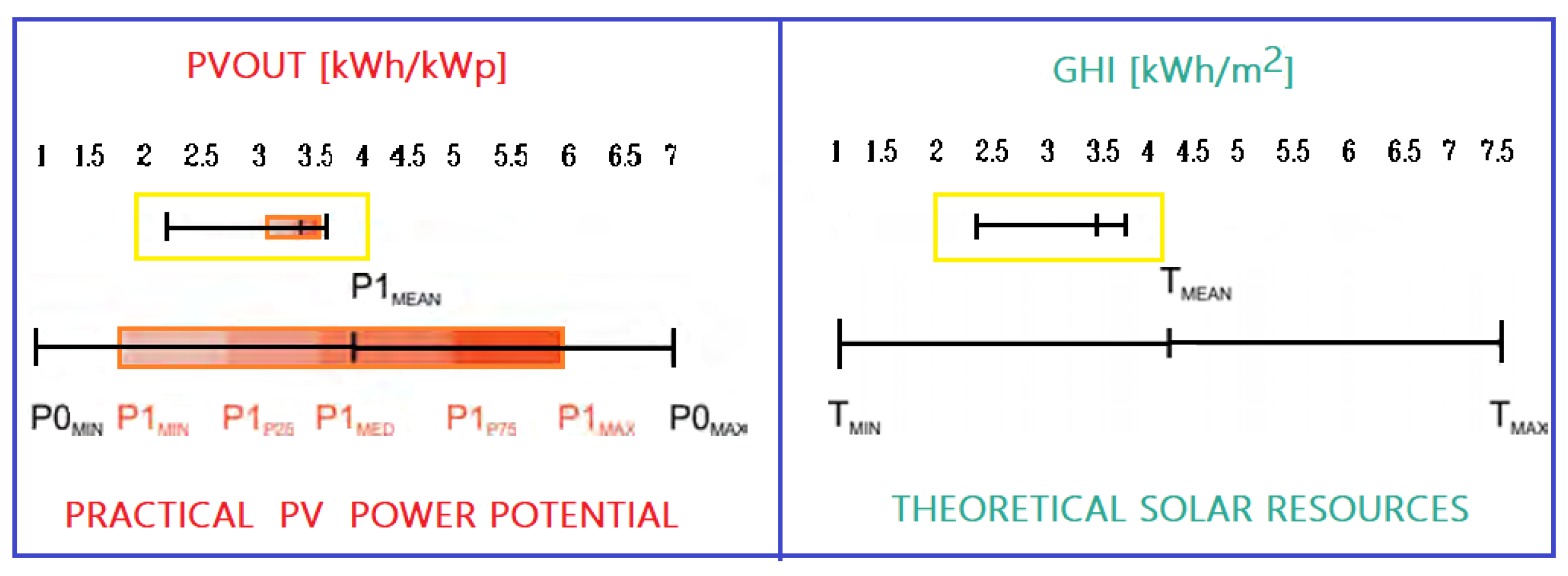

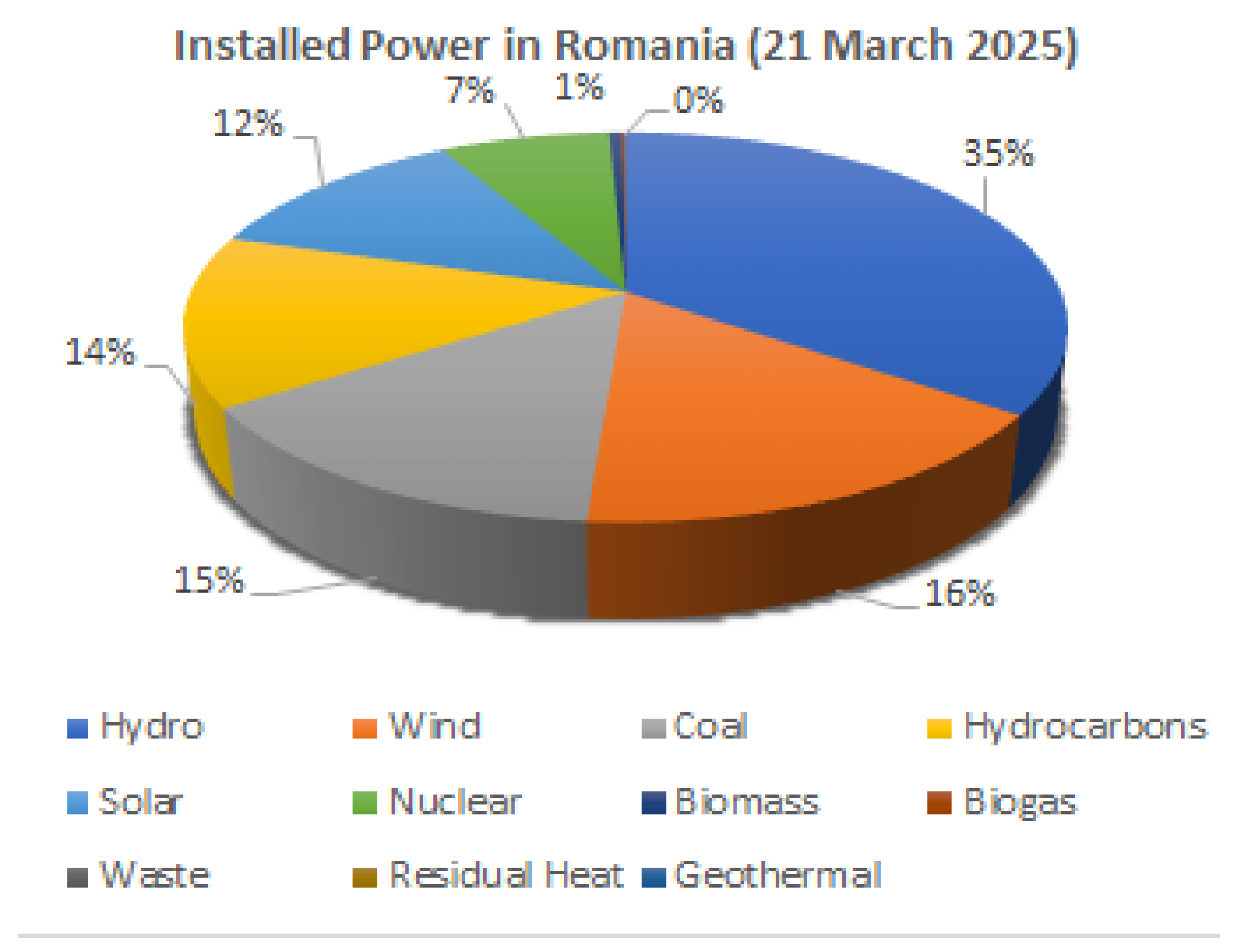

2. A Decade of Photovoltaic Installations in Europe and Romania

2.2. GW of Installed Capacity.

3. Assessing the Security and Safety of PV Systems as Critical Energy Infrastructure in Romania

3.1. SWOT Analysis

3.1.1. Strengths

- produce clean energy, without CO₂ emissions;

- do not generate noise pollution or hazardous waste;

- have a minimal impact on biodiversity, especially if they are harmoniously integrated into the landscape.

- reduce dependence on fossil fuels and their price fluctuations;

- can contribute to the energy independence of a country or region;

- are scalable, and can be expanded according to needs.

- After the initial investment, operating and maintenance costs are relatively low;

- Photovoltaic panels have a lifespan of 25-30 years, offering long-term returns;

- Government subsidies and support schemes can make the investment even more profitable.

- Installing a PV system is faster compared to other types of power plants;

- Requires little maintenance, as the panels have no moving parts that wear out quickly.

- Can be installed on unproductive or unused land;

- Coexist with other activities, such as agriculture (agrivoltaics);

- Can be integrated into smart-grid networks to optimize consumption.

3.1.2. Weaknesses

3.1.3. Opportunities

- Energy cost reduction – Own solar energy production can lead to lower costs for consumers and businesses;

- Profitable investments – The financial returns of photovoltaic parks are attractive due to the decrease in the prices of solar panels and their increase in efficiency;

- Job creation – The installation and maintenance of solar panels generates jobs in the renewable energy sector;

- Subsidies and financing – Governments and international organizations offer various financial support schemes for the development of renewable energy.

- CO₂ emission reduction – Solar energy is clean and contributes to reducing dependence on fossil fuels;

- Long-term sustainability – The sun is an inexhaustible resource, and its use does not negatively affect the environment;

- Reuse of degraded land – Photovoltaic parks can be located on unproductive or abandoned land, giving it a new utility.

- Innovations in Energy Storage – Modern batteries allow the storage of solar energy for use at night or on cloudy days;

- Integration into smart grids – Photovoltaic parks can be connected to smart grids, optimizing energy distribution;

- Increased automation and efficiency – New technologies, such as artificial intelligence and cleaning robots, improve the performance and maintenance of solar parks.

3.1.4. Threats, Risks, Vulnerabilities and Hazards

- Natural factors – Storms, hail, wildfires, earthquakes or floods can damage solar panels and park infrastructure;

- Vandalism and theft – Solar panels, inverters and cables are attractive to thieves, and vandalism can affect energy production;

- Cyber-attacks – Control and monitoring systems can be targets for cyber attacks, affecting the operation of the park;

- Regulations and policies – Changes in legislation, new taxes or land restrictions can threaten the economic viability of the project.

- Decreased efficiency – Dust, dirt or degradation of panels over time can reduce energy production;

- Technical problems – Failures in inverters, connections or energy storage system can affect the continuity of production;

- Dependence on weather conditions – The performance of a photovoltaic park depends directly on the intensity of sunlight, with the risk of lower production on cloudy days;

- Impact on the environment and biodiversity – Deforestation for the installation of the park or changes to the ecosystem can affect local fauna and flora;

- Unforeseen costs – Increased maintenance costs, repairs or price changes to equipment can affect profitability.

- Physical security – A poorly protected park is vulnerable to vandalism and theft;

- Dependence on supply chains – Problems with suppliers of panels, inverters or batteries can delay projects and increase costs;

- Lack of infrastructure – Connecting the park to the electricity grid can be difficult if the local infrastructure is not ready for such integration;

- Long payback period – The amortization of the initial costs can take years, and fluctuations in the price of electricity can affect profitability.

- Deforestation and habitat loss – PV parks are sometimes built on agricultural land or forests, affecting biodiversity;

- Impact on wildlife – Animals may be disturbed by changes in habitat or by the reflection of solar panels;

- Impact on soil and water – Changes to the land for the installation of panels can lead to erosion or changes in water runoff.

- Agricultural land use – If installed on fertile land, they can reduce the agricultural area available for food production;

- Visual impact – PV parks can alter the landscape and may be considered unsightly by local communities;

- Noise and nuisance – Although the panels themselves do not produce noise, auxiliary equipment such as inverters and cooling systems can generate some level of noise pollution.

- Difficulty in recycling panels – Solar panel components (glass, silicon, heavy metals) are difficult to recycle, which may lead to environmental problems in the future;

- Use of rare materials – Panels contain metals such as cadmium or tellurium, the extraction of which may have a negative impact on the environment.

- Fire risk – Solar panels and electrical equipment can present hazards in case of overload or technical defects;

- Material degradation – Solar panels have a limited lifespan (around 25-30 years), and managing the resulting waste can be problematic;

- Electromagnetism – Some studies suggest that equipment used in photovoltaic parks could generate electromagnetic fields, but the effects on health are still debated;

- Blackout risk – Some inverters can be remotely controlled by certain manufacturing companies, which makes the risk of disconnection of photovoltaic parks very likely and with a very serious gravity and impact on energy and national security.

3.1.5. Security, Safety and Protection Measures

- Fencing and access control – Installation of security fences and controlled access gates to prevent intrusion;

- Video surveillance systems – Use of surveillance cameras with motion detection and 24/7 monitoring;

- Detection sensors – Implementation of sensors to detect movement, vibration or opening of panels;

- Security patrols – Presence of security personnel or drones for regular inspections;

- Anti-theft and anti-vandalism systems – GPS tracking devices for panels, alarms and invisible markings for components.

- Grounding system – Prevention of electric shock and protection of equipment against atmospheric discharges;

- Lightning protection – Installation of lightning rods and surge arresters;

- Circuit breakers and overload protection – Installing safety equipment to prevent short circuits and fires;

- Adequate ventilation and cooling – Preventing equipment from overheating through efficient cooling systems;

- Periodic maintenance and inspection – Checking connections, wiring and panels to prevent failures.

- Wind and weather protection – Installation resistant to strong gusts, hail and floods;

- Fire prevention – Using fire-retardant materials and a rapid-fire response plan;

- Weather monitoring – Alert systems for extreme conditions that can affect production and park safety.

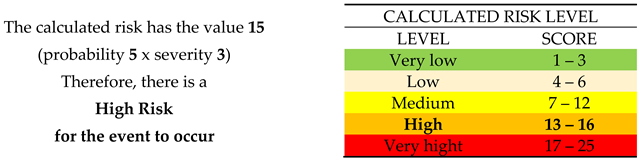

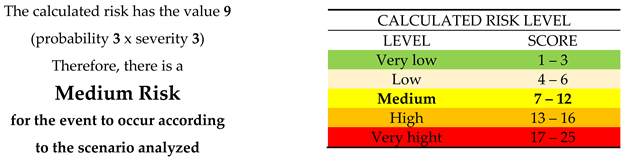

3.2. Black-Out Risk Assessment

3.2.1. Parts of the PV systems

- monocrystalline: Mono-Si;

- polycrystalline: Poly-Si;

- thin-film: Thin-Film;

- bifacial: captures light on both sides;

- with PERC technology: Passivated Emitter Rear Cell.

- centralized: used in large PV systems and connect several strings of solar panels to a single large inverter;

- string: each string of panels has its own inverter and is used in large commercial and residential installations;

- microinverters: each panel has its own inverter and is used in residential systems and small PV systems;

- hybrid: can operate both with the electrical grid and with energy storage batteries and is used in PV systems that include energy storage solutions.

- production measurement: measures the electrical energy generated by PV panels;

- auxiliary consumption measurement: records the consumption of auxiliary equipment in the park (inverters, cooling systems, lighting, surveillance, etc.);

- bidirectional: monitors both the energy delivered to the grid and the energy consumed from the grid, being essential for self-consumption and grid injection systems;

- smart meters: allows real-time monitoring in integration with SCADA systems to optimize energy management.

- role:

- voltage boosting: PV panels generate direct current (DC), converted into alternating current (DC) by inverters; this current usually has a voltage of 400V-690V, which must be raised to an appropriate level for efficient transport through the grid (e.g. 20 kV or 110 kV);

- loss reduction: increasing the voltage reduces losses on the power line and allows the efficient transport of electricity over long distances;

- grid connection: ensures compatibility between the PV park and the electricity distribution or transport network.

- types:

- boosters: raise the voltage from the level generated by the inverters (400V-690V) to 20 kV or 110 kV, to allow injection into the grid.

- distribution: are used to power auxiliary equipment in the park (monitoring systems, lighting, air conditioning, etc.);

- isolation: to protect the system against faults and to avoid the occurrence of ground fault currents.

- medium voltage: 20 kV;

- high voltage: 110 kV or 220 kV/400 kV.

- types:

- electrochemical batteries: Li-Ion, Lithium-Iron-Phosphate, Lead-Acid, Redox Flow, etc.;

- supercapacitors;

- hydrogen;

- pumped storage;

- compressed air, etc.

- benefits:

- grid balancing: reduces fluctuations caused by variations in solar intensity;

- consumption maximization: allows the use of the energy produced even when the panels are not generating electricity;

- reduction of balancing costs: minimizes the need to import electricity from other sources during peak hours;

- energy security: ensures constant power supply in microgrids or isolated areas.

- underground or overhead medium voltage power lines;

- underground or overhead high voltage power lines.

- by system architecture:

- centralized: all data is collected and processed in a single control center and provides complete visibility over the entire PV park;

- distributed: control is divided between several local nodes that communicate with each other, ensures redundancy and great flexibility, can operate independently in the event of a failure of the central system and is suitable for large PV systems with multiple conversion stations.

- by type of communication and technology:

- based on industrial protocol (Modbus, DNP3, IEC 61850): uses communication protocols for industrial equipment and is compatible with most equipment used in solar energy (inverters, energy meters, weather sensors);

- cloud-based (IoT – Enabled SCADA: data is transmitted and processed in a cloud environment, allows remote access, advanced data analysis and integration with AI and machine learning.

- by automation level:

- passive (monitoring, no control): only collects data (generated power, temperature, solar radiation level), decisions are made by human operators and is used in smaller PV systems or in the initial phase of implementation;

- active (monitoring and automated control): can adjust system parameters in real time (optimizing the operation of inverters, changing the angle of solar panels), includes advanced functions such as energy efficiency management and protection against faults

- by scope:

- for Energy Management (EMS – Energy Management System): monitors and optimizes electricity production, integrates with battery systems for energy storage and helps balance the load on the grid;

- for diagnostics and predictive maintenance: uses artificial intelligence algorithms to identify possible defects in equipment and can detect efficiency losses of PV panels caused by dirt or defects;

- for integration with the electrical grid: ensures compliance with the requirements of grid operators and regulates voltage and frequency to avoid imbalances in the system.

3.2.2. Causes and Effects in Black-Out Risk Scenario

- Storms and extreme weather events: strong winds, torrential rains, heavy snow, hail, lightning, which can damage electrical systems and equipment in PV systems (PV panels, electrical inverters, electrical meters, electrical transformers, energy storage systems, electrical power evacuation lines);

- Earthquakes or landslides: which can damage electrical and mechanical infrastructure;

- Extreme temperatures: excessive heat or cold, which can overload the electrical grid or damage PV panels.

- Defects or poor quality of PV panels;

- Damage to step-up transformers or overhead or underground cables: age or wear of equipment;

- Overload in the PV park: excessive electricity consumption in the power station;

- Short circuits: in the electrical power lines or in the electrical power distribution panels;

- Efficiency, life span and low quality of energy equipment;

- Lack of electrical energy storage systems;

- Lack or precariousness of SCADA systems;

- Lack of or poor cybersecurity programs.

- Lack or precariousness of maintenance or repair work;

- Human errors in the operation or management of the PV park or electrical networks;

- Acts of vandalism, theft, or sabotage;

- lack of investments;

- Wrong configuration: PV panels, inverters, transformers, electricity evacuation lines;

- Wrong maneuvers performed by operational or dispatching personnel;

- Lack of specialized and/or trained operational personnel;

- Lack of communication or poor communication with DET – Territorial Energy Dispatcher or DEN – National Energy Dispatcher;

- Lack of working procedures during a crisis;

- Lack/non-compliance/ignorance of national/European procedures in case of serious damage (black out);

- Lack of training in the field of Risk Management;

- Lack of physical security of PV systems. Effects:

- Lack of electricity in the distribution or transport networks: possible local, zonal, regional or national black-out of the National Energy System;

- Enormous material damage generated by the lack of electricity to critical consumers, households and industries;

- Enormous material damage resulting from the interdependence of other systems on electricity;

- State of energy, economic and national insecurity.

- Lack of electricity in the distribution or transmission networks: possible local, zonal, regional or national blackout of the National Energy System;

- Enormous material damage resulting from the lack of electricity to critical consumers, households and industries;

- Enormous material damage resulting from the interdependence of other systems on electricity;

- State of energy, economic and national insecurity.

3.2.3. The Probability Scale

3.2.4. The Severity of the Consequences

| P R O B A B I L I T Y | Very high 5 |

|||||

| High 4 |

||||||

|

Medium 3 |

Risk scenario | |||||

| Low 2 |

||||||

| Very low 1 |

||||||

| 0 |

Very low 1 |

Low 2 |

Medium 3 |

High 4 |

Very high 5 |

|

| SEVERITY / CONSEQUENCES | ||||||

| Note: Risk is given by the product of the probability of occurrence of a hazard/threat and the severity of its consequences. | ||||||

3.5. Risk Management

3.5. Reevaluation of the Consequence Severity

| LEVEL / SCORE | THE SEVERITY OF THE CONSEQUENCES | |

| 1. Very low | The event causes a minor disruption to the activity, without material damage. | |

| 2. Low | The event causes minor property damage and limited disruption to business | |

| X | 3. Medium | Injuries to personnel, and/or some loss of equipment, utilities, and delays in service provision. |

| 4. High | Serious injuries to personnel, significant loss of equipment, facilities, and delays and/or interruption of service provision. | |

| 5. Very high | The consequences are catastrophic resulting in fatalities and serious injuries to personnel, major loss of equipment, facilities, and services, and interruption of service provision. | |

3.6. Risk Level After Application of Mitigation Measures

| P R O B A B I L I T Y | Very high 5 |

|||||

| High 4 |

||||||

|

Medium 3 |

Risk scenario | |||||

| Low 2 |

||||||

| Very low 1 |

||||||

| 0 |

Very low 1 |

Low 2 |

Medium 3 |

High 4 |

Very high 5 |

|

| SEVERITY / CONSEQUENCES | ||||||

| Note: Risk is given by the product of the probability of occurrence of a hazard/threat and the severity of its consequences. | ||||||

4. Addressing PV Systems’ Vulnerabilities to Cyber-Attacks

4.1. Specific Cyber Threats in PV Systems

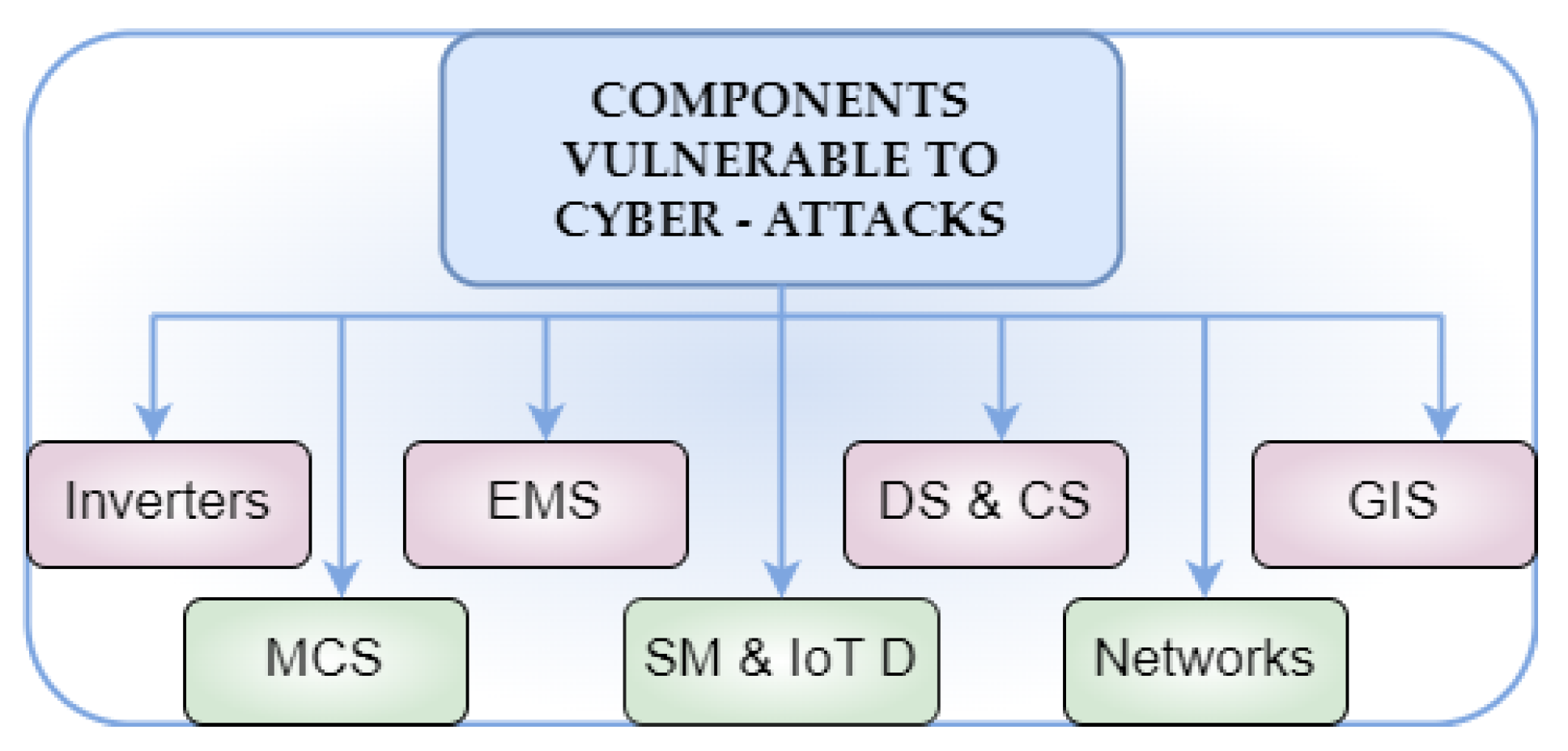

4.2. PV Key Components Vulnerable to Cyber Attacks

4.3. A Brief Literature Review on Cyber Treats and Security Solutions in PV systems

4.4. Cyber Incidents in Solar PV Systems

4.5. Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) and Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) in PV systems

5. Strategies for Cyber Threats Mitigation in solar PV systems

5.1. Cyber Security Risk Management in PV systems

5.2. Security Policy for PV Systems

- All PV systems’ assets (solar panels, inverters, SCADA systems, monitoring platforms, sensors, and network infrastructure);

- Personnel (employees, contractors, and third-party service providers handling PV operations);

- Data security (grid connectivity, energy production data, remote monitoring, and communication channels).

- Install fencing, gates, and surveillance cameras (CCTV) around PV fields;

- Use motion sensors and intrusion alarms for unauthorized access detection;

- Maintain security patrols in high-risk areas;

- GPS tracking on high-value assets (inverters, transformers);

- Lightning protection systems for weather-related risks;

- Fire detection and suppression systems at critical sites.

- Encrypt energy production data before transmission;

- Ensure compliance with GDPR for personal data collected from monitoring systems;

- Store logs and audit trails for at least 1 year for forensic analysis;

- Conduct mandatory security training for all employees and contractors;

- Simulated phishing tests to improve awareness;

- Strict onboarding and offboarding procedures for access control.

5.3. Compulsory Security Measures

- ensuring that all software and firmware in the system are up-to-date by regular updates and patch management;

- the use of MFA and enforce strong passwords for remote access to devices and control systems for a strong authentication;

- encrypting data both at rest and during transmission to protect sensitive information.

- isolate critical components (e.g., inverters, energy management systems) from less critical systems to reduce the attack surface using the network segmentation principle;

- deploy IDS to monitor any unusual activity and potential cyberattacks in real-time;

- secure physical assets with locks, surveillance cameras, and restricted access areas to prevent tampering;

- ensuring that PV components are sourced from reputable manufacturers with transparent security practices can reduce the risk of embedded vulnerabilities as part of a strong supply chain vigilance;

- adhering to established cybersecurity standards and guidelines can enhance the resilience of PV systems against potential threats.

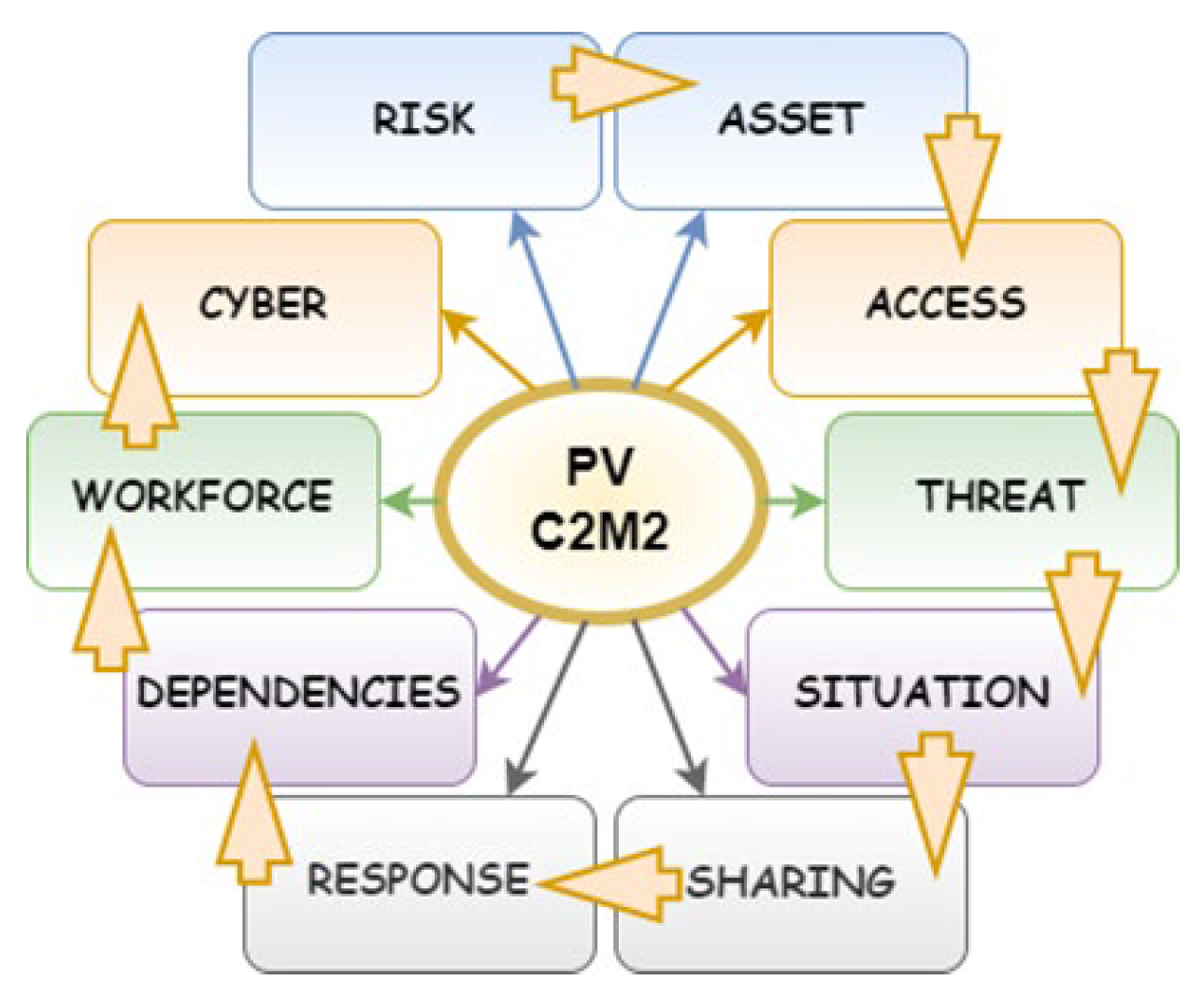

5.3. Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) for PV Systems

6. Results

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicolae Daniel Fîță, Mila Ilieva Obretenova, Adrian Mihai Șchiopu, Național Security – Elements regarding the optimisation of energy sector, LAP – Lambert Academic Publishing, UK, ISBN: 978-620-7-45693-2, 2024.

- Nicolae Daniel Fîță, Adina Tătar, Mila Ilieva Obretenova, Security risk assessment of critical energy infrastructures, LAP – Lambert Academic Publishing, UK, ISBN: 978-620-7-45824-0, 2024.

- Nicolae Daniel Fîță, Mila Ilieva Obretenova, Florin G. Popescu, Romanian Power System – European energy security generator LAP – Lambert Academic Publishing, UK, ISBN: 978-620-7-46269-8.

- Daniel N. Fîță, Dan C. Petrilean, Ioan L. Diodiu, Analysis of the National Power Grid from Romania in the context of identifying vulnerabilities and ensuring energy security, Proceedings of Renewable Energy and Power Quality Journal (RE&PQJ), 22nd International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality – ICREPQ 2004, Bilbao (Spain), ISSN 2172-038 X, Volume No.22. https://www.icrepq.com/icrepq24/386-24-fita.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Nicolae Daniel Fîță, Dan Codrut Petrilean, Ioan Lucian Diodiu, Andrei Cristian Rada, Adrian Mihai Schiopu, Florin Muresan-Grecu Analysis of the causes of power crises and theit impacts on energy security, Proceedings of International Conference on Electrical, Computer ad Energy Technologies – ICECET 2204, July 2024, Sydney, Australia, Publisher IEEE, Date added to IEEE Explore: 08 October 2024, www.icecet.com. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10698524. [CrossRef]

- Pasculescu D, Niculescu T., „Study of transient inductive-capacitive circuits using data acquisition systems”, International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM. 2015;2(1):323-9.

- Pasculescu VM, Radu SM, Pasculescu D, Niculescu T., „Dimensioning the intrinsic safety barriers of electrical equipment intended to be used in potentially explosive atmospheres using the SimPowerSystems software package”, International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM. 2013;1:417.

- Pana L, Grabara J, Pasculescu D, Pasculescu VM, Moraru RI., „Optimal quality management algorithm for assesing the usage capacity level of mining tranformers”, Polish Journal of Management Studies. 2018;18(2):233-44.

- Popescu FG, Pasculescu D, Marcu MD, Pasculescu VM., „Analysis of current and voltage harmonics introduced by the drive systems of a bucket wheel excavator”, Mining of Mineral Deposits. 2020 Dec 30.

- Ilieva-Obretenova, M., “Information System Functions for SmartGrid Management”, Sociology Study, Volume 6, Number 2, February 2016, (Serial Number 57) pp. 96-104, ISSN 2159-5526 (Print), ISSN 2159-5534 (Online). [CrossRef]

- Ilieva-Obretenova M. Impact of an energy conservation measure on reducing CO2 emissions. Electrotechnica & Electronica (Е+Е), Vol. 56 (3-4), 2021, pp.46-54, ISSN: 0861-4717 (Print), 2603-5421 (Online).

- Rossi R, Mehan B., EU Market Outlook for Solar Power 2024-2028, 17 December 2024, https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/eu-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2024-2028, (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Dumitrașcu, M., Grigorescu, I., Vrînceanu, A. et al. An indicator-based approach to assess and compare the environmental and socio-economic consequences of PV systems in Romania's development regions. Environ Dev Sustain (2024). [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ioplus.nl/en/posts/europes-solar-panel-installations-saw-a-significant-slowdown-in-2024 (accessed on 15 Febr 2025).

- Available online: https://www.power-technology.com/data-insights/top-5-solar-pv-plants-in-development-in-romania (accessed on 10 Febr 2025).

- Suri,Marcel; Betak,Juraj; Rosina,Konstantin; Chrkavy,Daniel; Suriova,Nada; Cebecauer,Tomas; Caltik,Marek; Erdelyi,Branislav., Global PV Power Potential by Country (English). Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/466331592817725242.

- Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/global-pv-potential-study, accessed (10 Feb 2025).

- Patrick Jowett, Romania’s 2024 solar additions hit 1.7 GW, January 31, 2025 https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/01/31/romanias-2024-solar-additions-hit-1-7-gw/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Niculescu G., Avăcăriței G., Mihăilescu M., Mihai I., Radu V., Dulamea R., Nagy-Bege Z., Monitor of the Romanian PV Projects, March 2024 https://www.energynomics.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Report-Energynomics-PV-Monitor-March-2024-0.2.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/, accessed (02 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/466331592817725242/pdf/Global-PV-Power-Potential-by-Country.pdf (accessed 20 March 2024).

- Available online: https://www.afm.ro/sisteme_fotovoltaice.php (accessed 20 Dec 2024).

- Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/repowereu-affordable-secure-and-sustainable-energy-europe_en, (accessed 20 Jan 2025).

- Available online: https://livoltek.com/products/, (accessed 10 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://support.enphase.com/, (accessed 05 Feb 20250).

- Available online: https://energyworld.ro/2025/02/06/romania-romania-remains-extremely-deficient-in-energy-storage/.

- Available online: https://anre.ro/puteri-instalate/, (accessed 01 Feb 2025).

- Marius Nicolae Badica, Carmen Matilda Marinescu (Badica), Silvian Suditu, Monica Emanuela Stoica, Identification, evaluation and minimization of industrial risks relating to gas pipelines, E3S Web of Conf. 225 02004 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Teymouri, A., A. Mehrizi-Sani, and C.-C. Liu. 2019. “Cyber Security Risk Assessment of Solar PV Units with Reactive Power Capability.” Proceedings of IECON 2018 - 44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society: 2,872–2,877. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan D., Riurean S. Cyber-Security Attacks, Prevention and Malware Detection Application. J. Digit. Sci. 4(2), 3 – 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Riurean P., Bolog G., Riurean S., The Rise of Sophisticated Phishing. How AI Fuels Cybercrime. JDS, 6(2), 15-25, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jay Johnson, "Roadmap for PV System Cyber Security", December 2017, Report number: SAND2017-13262Affiliation: Sandia National Laboratories https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322568290_Roadmap_for_PV_Cyber_Security.

- Walker, Andy, Jal Desai, Danish Saleem, and Thushara Gunda. 2021. Cybersecurity in Photovoltaic Plant Operations. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-5D00-78755. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/78755.pdf. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/solar-cybersecurity.

- Cynthia Brumfield, Hijack of monitoring devices highlights cyber threat to solar power infrastructure, May 2024. https://www.csoonline.com/article/2119281/hijack-of-monitoring-devices-highlights-cyber-threat-to-solar-power-infrastructure.html.

- J. Ye et al., "A Review of Cyber–Physical Security for PV Systems," in IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 4879-4901, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Călin, A.-M.; Cotfas, D.T.; Cotfas, P.A. A Review of Smart PV Systems Which Are Using Remote-Control, AI, and Cybersecurity Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7838. [CrossRef]

- Volker Naumann, Dominik Lausch, Angelika Hähnel, Jan Bauer, Otwin Breitenstein, Andreas Graff, Martina Werner, Sina Swatek, Stephan Großer, Jörg Bagdahn, Christian Hagendorf, Explanation of potential-induced degradation of the shunting type by Na decoration of stacking faults in Si solar cells, Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells,Volume 120, Part A,2014,Pages 383-389,ISSN 0927-0248.

- A.M. Saber, A. Youssef, D. Svetinovic, H. Zeineldin and E. El-Saadany, "Learning-Based Detection of Malicious Volt-VAr Control Parameters in Smart Inverters," IECON 2023- 49th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, Singapore, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Sourav, S., Biswas, P. P., Chen, B., & Mashima, D. (2022). Detecting Hidden Attackers in PV Systems Using Machine Learning. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.05226.

- Lindström, M., Sasahara, H., He, X., Sandberg, H., & Johansson, K. H. (2020). Power Injection Attacks in Smart Distribution Grids with PVs. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.05829.

- Zografopoulos, I., Hatziargyriou, N. D., & Konstantinou, C. (2022). Distributed Energy Resources Cybersecurity Outlook: Vulnerabilities, Attacks, Impacts, and Mitigations. ArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Feenstra Helin, Solar cybersecurity vulnerabilities: 6 ways in which hackers target solar installations, October 15, 2024, https://www.helindata.com/blog/solar-cybersecurity-vulnerabilities.

- A. Teymouri, A. Mehrizi-Sani and C. -C. Liu, "Cyber Security Risk Assessment of Solar PV Units with Reactive Power Capability," IECON 2018 - 44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 2018, pp. 2872-2877. [CrossRef]

- I. Zografopoulos, N. D. Hatziargyriou and C. Konstantinou, "Distributed Energy Resources Cybersecurity Outlook: Vulnerabilities, Attacks, Impacts, and Mitigations," in IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 6695-6709, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Harrou Fouzi, Taghezouit Bilal, Bouyeddou Benamar, Sun Ying; Cybersecurity of PV systems: challenges, threats, and mitigation strategies: a short survey, Frontiers in Energy Research, Vol 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Maghami, M.R., Mutambara, A.G.O. & Gomes, C. Assessing cyber-attack vulnerabilities of distributed generation in grid-connected systems. Environ Dev Sustain (2025). [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Liu, L., Wei, D., and Cao, J. “Research on security threat and evaluation model of new energy plant and station,” in Proceedings - 2020 International Conference on Computer Communication and Network Security, Xi'an, China, August 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A., Poudel, B., Bidram, A., and Modares, H. (2020). Detection and mitigation of data manipulation attacks in AC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 11, 2588–2603. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T., Wang, B., Ramos-Ruiz, J., Enjeti, P., Kumar, P. R., and Xie, L. “Detection of cyber-attacks in renewable-rich microgrids using dynamic watermarking,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, August 2020. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A., Roy, S., and Baldi, S. (2021). Wide-area damping control resilience towards cyber-attacks: A dynamic loop approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 12, 3438–3447. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Li, J., Li, Q., and Li, F. (2022). A federated learning framework for detecting false data injection attacks in solar farms. IEEE Trans. Power Electron 37, 2496–2501. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Guo, L., and Ye, J. (2022). Cyber-attack detection for PV farms based on power-electronics-enabled harmonic state space modeling. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 13, 3929–3942. [CrossRef]

- Beg, O. A., Nguyen, L. V., Johnson, T. T., and Davoudi, A. (2019). Signal temporal logic-based attack detection in DC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10, 3585–3595. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. K., and Govindarasu, M. (2021). A cyber-physical anomaly detection for wide-area protection using machine learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 12, 3514–3526. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Zhang, J., Ye, J., Coshatt, S. J., and Song, W. (2022). Data-driven cyber-attack detection for PV farms via time-frequency domain features. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 13, 1582–1597. [CrossRef]

- Rahim, FA, et.al., Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities in Smart Grids with Solar Photovoltaic: A Threat Modelling and Risk Assessment Approach, International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology, Vol. 14, Iss. 3, 210-220. [CrossRef]

- Ioan Alexandru MELNICIUC, Alexandru LAZĂR, George CABĂU, Radu Alexandru BASARABA, Bitdefender Disclosure Report, Solarman Platform Vulnerability https://blogapp.bitdefender.com/labs/content/files/2024/08/Bitdefender-PReport-solarman-creat7907.pdf.

- Eduard Kovacs, Vulnerabilities Exposed Widely Used Solar Power Systems to Hacking, Disruption, August 8, 2024, https://www.securityweek.com/vulnerabilities-exposed-widely-used-solar-power-systems-to-hacking-disruption/.

- Available online: https://www.csoonline.com/article/2119281/hijack-of-monitoring-devices-highlights-cyber-threat-to-solar-power-infrastructure.html, (accessed 15 Dec 2024).

- Available online: https://www.climatesolutionslaw.com/2025/02/cybersecurity-and-solar-power-vulnerability, (accessed 28 Febr 2025).

- Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/solar-power-stocks-fall-on-concerns-about-potential-hackers-8685365, (accessed 20 Oct 2024).

- Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/finnish-utility-fortums-power-assets-targeted-with-surveillance-cyber-attacks-2024-10-10/, accessed 20 Dec 2024.

- Nikolaus J. Kurmayer, White hat hacker shines spotlight on vulnerability of solar panels installed in Europe, Oct 1, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/hacker-shines-spotlight-on-vulnerability-of-solar-panels-installed-in-europe.

- Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/, (accessed 28 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://cve.mitre.org/, (accessed 05 Feb 2025).

- Y. Dubasi, A. Khan, Q. Li and A. Mantooth, "Security Vulnerability and Mitigation in Photovoltaic Systems," 2021 IEEE 12th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Chicago, IL, USA, 2021, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/ics-advisories/icsa-25-044-16, (accessed 12 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://dnsc.ro/citeste/alerta-vulnerabilitati-critice-de-securitate-cibernetica-identificate-la-nivelul-unor-produse-myscada, (accessed 08 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.myscada.org/, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/ics-advisories/icsa-25-044-16, (accessed 08 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://cwe.mitre.org/., (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/calculator/3.1#CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:H/A:H, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/calculator/4.0#CVSS:4.0/AV:N/AC:L/AT:N/PR:N/UI:N/VC:H/VI:H/VA:H/SC:N/SI:N/SA:N, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/calculator/3.1#CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/calculator/4.0#CVSS:4.0/AV:N/AC:L/AT:N/PR:N/UI:N/VC:H/VI:H/VA:H/SC:H/SI:H/SA:H, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Tatiana Antipova, Simona Riurean, Managing cyber resilience literacy for consumers, International Journal of Informatics and Communication Technology (IJ-ICT) 122 Vol. 14, No. 1, April 2025, pp. 122~131 ISSN: 2252-8776. [CrossRef]

- "IEEE Guide for Cybersecurity of Distributed Energy Resources Interconnected with Electric Power Systems," in IEEE Std 1547.3-2023 (Revision of IEEE Std 1547.3-2007) , vol., no., pp.1-183, 11 Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., Liu, M., Zuo, K., Tan, W., and Deng, R. “Stealthy data integrity attacks against grid-tied PV systems,” in Proc. - 2023 IEEE 6th Int. Conf. Ind. Cyber-Physical Syst. ICPS, Wuhan, China, May 2023, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Simona Riurean, Tatiana Antipova, Prebunking, An Effective Defense Mechanism To Strengthen Consumers’ Cyber Awareness, Annals of the University of Petrosani, Electrical Engineering, 26 (2024).

- Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/nis2-directive, (accessed 20 Dec 2024).

- Available online: https://www.energy.gov, (accessed 20 Feb 2025).

- Jay Johnson, Roadmap for PV Cyber Security. Report number: SAND2017-13262, Affiliation: Sandia National Laboratories, Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322568290_.

- Available online: https://indiasmartgrid.org/upload/201705Wed174314.pdf, (accessed 28 Feb 2025).

| Category | Power Range | Application | Characteristics | Cost per Watt ($) |

Efficiency (%), | ROI (Years) |

Residential |

<10 kW | Installed on rooftops of homes. | - Used for self-consumption and grid-tied systems. - May include battery storage for backup. |

2.50 - 3.50 | 15-22% | 5-10 |

Commercial |

<250 kW | Found on business buildings, schools, and shopping centers. | - Used to offset electricity costs. - Often connected to local grids with net metering |

1.50 - 2.50 | 16-22% | 4-8 |

Industrial |

<1000 kW (1 MW) |

Used in factories, manufacturing plants, and data centers. |

- Supports high energy demands and may include on-site battery storage. - May be grid-connected or hybrid |

1.20 - 2.00 | 17-23% | 3-7 |

Utility-Scale |

>1000 kW (1 MW+) | Large-scale, ground-mounted solar farms. | - Generates electricity for utility grids. - Includes centralized inverters and tracking systems for maximum efficiency. - Requires high-voltage grid connections |

0.90 - 1.50 | 18-24% | 2-6 |

| County |

Location (commune) in Romania |

Capacity [MW] |

| Dolj | Piscu Sadovei | 1,500.00 |

| Dolj | near Calafat | 1,050.00 |

| Arad | Pilu și Grăniceri | 1,044.00 |

| (Grasshopper Romania Solar PV Park) | 1,000.00 | |

| Teleorman | Băbăita | 710.00 |

| Type of Energy | MW | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hydro | 6,687.78 | 34.9810 |

| Wind | 3,095.31 | 16.1903 |

| Coal | 2,762.2 | 14.4479 |

| Hydrocarbons | 2,713.78 | 14.1946 |

| Solar | 2,307.35 | 12.0688 |

| Nuclear | 1,413 | 7.3908 |

| Biomass | 106.27 | 0.5559 |

| Biogas | 22.46 | 0.1175 |

| Waste | 6.03 | 0.0315 |

| Residual Heat | 4.1 | 0.0214 |

| Geothermal | 0.05 | 0.0003 |

| LEVEL / ASSOCIATED SCORE |

DEFINITION OF PROBABILITY |

PERIODS | |

| 1. Very low | There is a very low probability of occurring. Normal measures are required to monitor the evolution of the event. |

over 13 years | |

| 2. Low | The event has a low probability of occurring. Efforts are being made to reduce the probability and/or mitigate the impact. |

10 – 12 years | |

| X | 3. Medium | The event has a significant probability of occurring. Significant efforts are required to reduce the probability and/or mitigate the impact. | 7 – 9 years |

| 4. High | The event has a probability of occurring. Priority efforts are required to reduce the probability and mitigate the impact produced. | 4 – 6 years | |

| 5. Very high | The event is considered imminent. Immediate and extreme measures are required to protect the objective, evacuation to a safe location if the impact requires it. | 1 – 3 years | |

| RISK SCENARIO: BLACK-OUT RISKS | LEVEL |

1. Natural hazards

|

Very low |

| Low | |

| Medium | |

| High | |

| Very High | |

2. Technical risks

|

Very low |

| Low | |

| Medium | |

| High | |

| Very High | |

3. Human risk factors:

|

Very low |

| Low | |

| Medium | |

| High | |

| Very High |

| IMPACTS | Level | |

| Enormous damage caused by lack of electricity | 1. Vey low | temporary |

| 2. Low | significant damage | |

| 3. Medium | average damage | |

| 4. High | high damage | |

| 5. Very high | very heavy damage | |

| Enormous damage generated by the interdependence of other systems | 1. Vey low | 0 – 10% of RIC |

| 2. Low | 11 – 20% of RIC | |

| 3. Medium | 21 – 30% of RIC | |

| 4. High | 31 – 40% of RIC | |

| 5. Very high | over 41% of RIC | |

| Potential environmental damage | 1. Vey low | 0 – 20% |

| 2. Low | 21 – 40% | |

| 3. Medium | 41 – 60% | |

| 4. High | 61 – 80% | |

| 5. Very high | over 81% | |

| High social impacts | 1. Vey low | 0 – 10% of PT |

| 2. Low | 11 – 20% of PT | |

| 3. Medium | 21 – 30% of PT | |

| 4. High | 31 – 40% of PT | |

| 5. Very high | over 41% of PT | |

| RIC– Return on Invested Capital; PT – Public Trust. | ||

| LEVEL / SCORE | THE SEVERITY OF THE CONSEQUENCES | |

| 1. Very low | The event causes a minor disruption to the activity, without material damage. | |

| 2. Low | The event causes minor property damage and limited disruption to business | |

| 3. Medium | Injuries to personnel, and/or some loss of equipment, utilities, and delays in service provision. | |

| 4. High | Serious injuries to personnel, significant loss of equipment, facilities, and delays and/or interruption of service provision. | |

| X | 5. Very high | The consequences are catastrophic resulting in fatalities and serious injuries to personnel, major loss of equipment, facilities, and services, and interruption of service provision. |

| TYPES OF RISK | PROPOSED MEASURES |

1. Natural risk factors

|

|

2. Technical risks

|

|

3. Human risk factors

|

|

| RISKS | IDENTIFIED | RESULTS AFTER MEASUREMENT IMPLEMENTATION | |

1. Natural risk factors

|

1. Very low | 1. Very low | |

| 2. Low | 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | 4. High | ||

| 5. Very high | 5. Very high | ||

2. Technical risks

|

1. Very low | 1. Very low | |

| 2. Low | 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | 4. High | ||

| 5. Very high | 5. Very high | ||

3. Human risk factors

|

1. Very low | 1. Very low | |

| 2. Low | 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | 4. High | ||

| 5. Very high | 5. Very high | ||

| Score | Range | Severity | |

| From | To | ||

| None | 0 | 0 | |

| Low | 0.1 | 3.9 | |

| Medium | 4.0 | 6.9 | |

| High | 7.0 | 8.9 | |

| Critical | 9.0 | 10 | |

| Year | CWE | Explanation | CVE | Base score | CVSS severity |

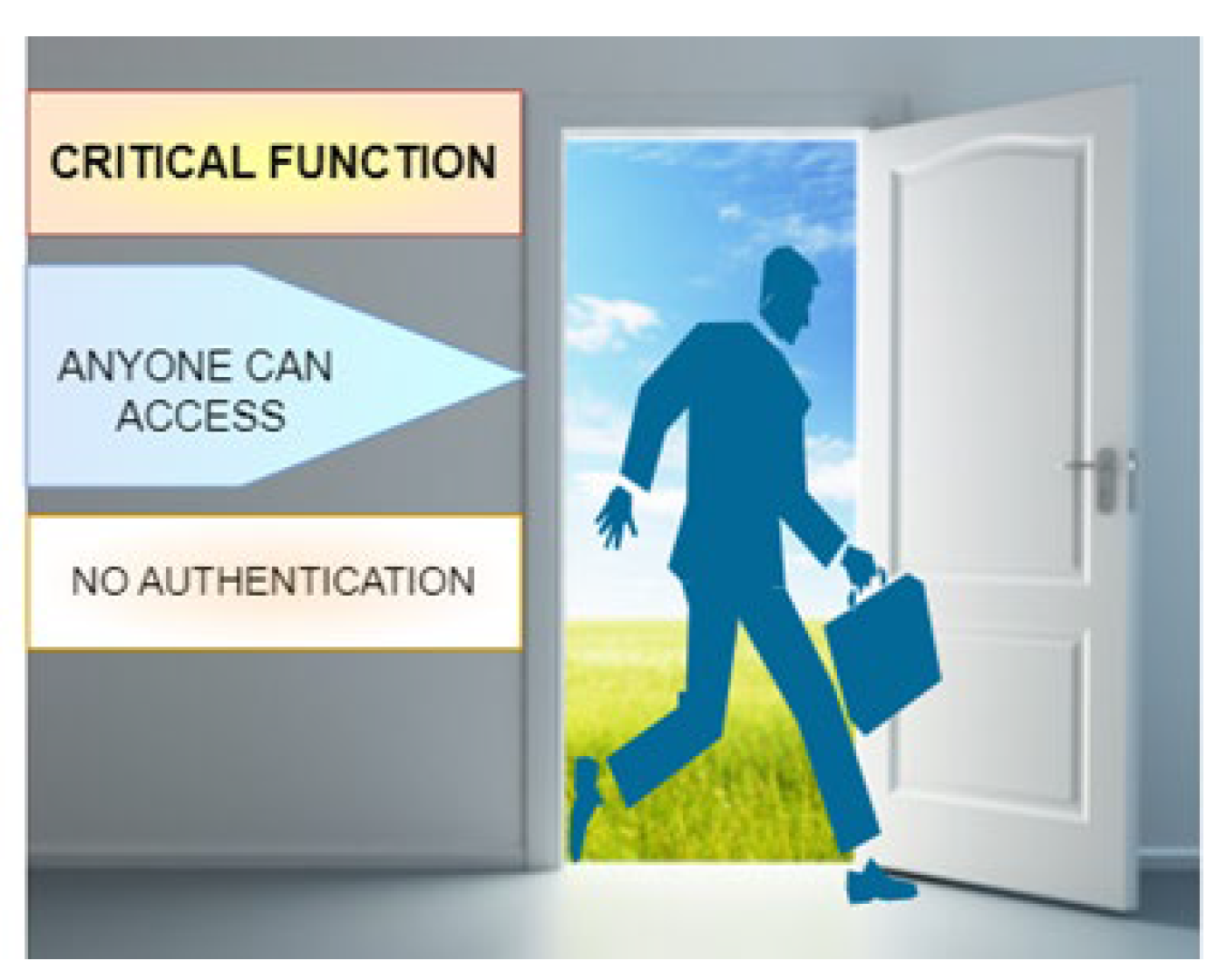

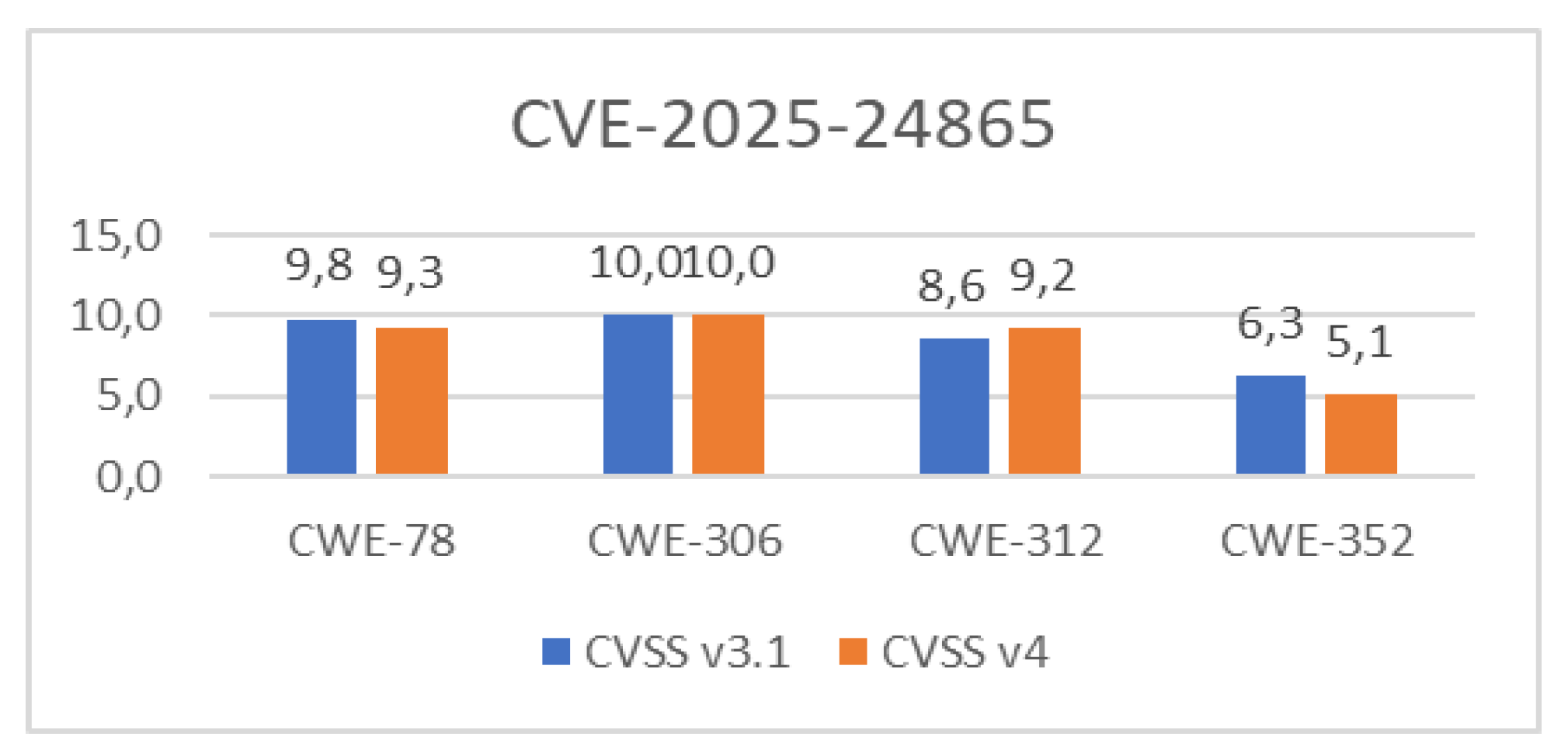

| 2025 | 306 | Missing authentication for critical function (MACF) | CVE-2025-24865 | 10 | critical |

| 312 | Cleartext storage of sensitive information (CSSI) | ||||

| 352 | Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) | ||||

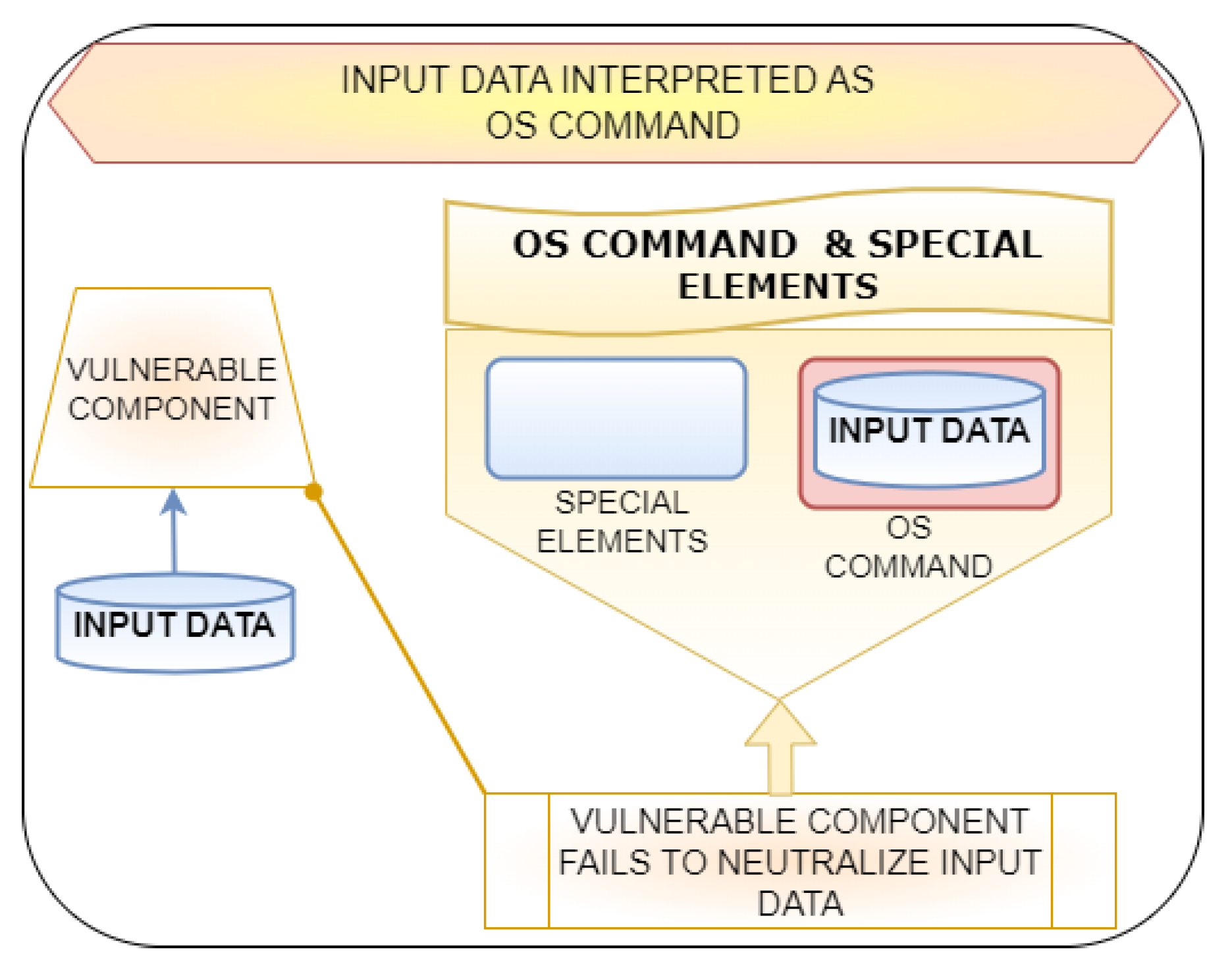

| 78 | Improper neutralization of special elements used in an OS Command (OS Command Injection) | ||||

| 2022 | 603 | Use of Client-Side Authentication | CVE-2022-33139 | 9.8 | critical |

| 287 | Improper Authentication - SCADA system only uses client-side authentication, allowing adversaries to impersonate other users. | ||||

| 2019 | 521 | Weak Password Requirements | CVE-2019-7676 | 7.2 | high |

| 79 | Improper Neutralization of Input During Web Page Generation ('Cross-site Scripting' XSS) | CVE-2019-7677 | 6.1 | medium | |

| 22 | Improper Limitation of a Pathname to a Restricted Directory ('Path Traversal') | CVE-2019-7678 | 9.8 | critical | |

| CVE-2019-19229 | 6.5 | medium | |||

| 312 | Cleartext Storage of Sensitive Information | CVE-2019-19228 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 2018 | 200 | Exposure of Sensitive Information to an Unauthorized Actor | CVE-2018-12735 | 7.5 | high |

| CVE-2018-12927 | 7.5 | high | |||

| 2017 | noinfo | Insufficient Information | CVE-2017-9851 | 7.5 | high |

| CVE-2017-9864 | 7.5 | high | |||

| 798 | Use of Hard-coded Credentials | CVE-2017-9852 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 521 | Weak Password Requirements - Allows brute-force attacks on the password | CVE-2017-9853 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 311 | Missing Encryption of Sensitive Data - Lack of encryption compromises CIA | CVE-2017-9854 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 311 | Incorrect Authorization | CVE-2017-9855 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 256 | Plaintext Storage of a Password - Storing a password in plaintext may result in a system compromise | CVE-2017-9856 | 3.4 | low | |

| 287 | Improper Authentication | CVE-2017-9857 | 8.1 | high | |

| CVE-2017-9860 | 9.8 | critical | |||

| 200 | Exposure of Sensitive Information to an Unauthorized Actor | CVE-2017-9858 | 7.5 | high | |

| CVE-2017-9862 | 7.5 | high | |||

| 327 | Use of a Broken or Risky Cryptographic Algorithm | CVE-2017-9859 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 74 | Improper Neutralization of Special Elements in Output Used by a Downstream Component ('Injection') | CVE-2017-9861 | 9.8 | critical | |

| 352 | Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) | CVE-2017-9863 | 8.8 | high | |

| 2012 | 89 | Improper Neutralization of Special Elements used in an SQL Command | CVE-2012-5861 | 7.5 | high |

| 310 | Cryptographic issues | CVE-2012-5862 | - | high | |

| 264 | Permissions, Privileges, and Access Control | CVE-2012-5863 | - | high |

| Control Area | Control Requirement | Standard Reference | Current Implemen-tation Status | Gap Description | Risk Level | Recommended Action |

| Access Control | Implement MFA for remote access. | NIST PR.AC-7 / ISO 27001 A.9.4.2 | N/A | Remote access protected only by username/password | High | Implement MFA using tokens or authenticator apps |

| Asset Management | Maintain an up-to-date asset inventory. | ISO 27001 A.8.1.1 / NIST ID.AM-1 | Partially imple- mented |

No centralized inventory of PV components | Medium | Deploy asset management system and conduct full inventory |

| Incident Response | Establish an incident response plan (IRP) and test it regularly. | ISO 27001 A.16.1.1 / NIST RS.RP-1 | N/A | No formal plan for responding to cyber incidents | High | Develop and regularly test an IRP |

| Step | Description | Explanation/Methods |

| Framing the Risk | Defining threats that give rise to overall risk | Threats may arise due to - flawed processes; - insecure products; - cyber attacks; - disruption of services; - legal exposure; - loss of confidential intellectual property. |

| Assessing the Risk | Consider the severity of each threat identified | Quantitative assessment (e.g., financial loss) and/or qualitative assessment (e.g., impact on operations). |

| Responding to the Risk | Reduce exposure to the risks | Each risk needs to be eliminated,- decreased, transferred, or accepted based on its assessed impact and available resources. |

| Planning for Incident Response |

Developing and keeping incident response plans, defining roles, responsibilities, and procedures in clear terms |

Conducting simulations and drills optimizes organizational preparedness. |

| Risk Monitoring | Risk management is continuous | Risks must still be monitored, and any remaining (accepted) risk should be monitored carefully to ensure that it remains acceptable. |

| Risk type | Likelihood | Impact | Risk level |

| Unauthorized Remote Access | High | Critical | High |

| Malware/Ransomware Attack | High | High | Critical |

| Physical Theft or Vandalism | Medium | High | High |

| Weather-Related Damage | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Regulatory Non-Compliance | Low | High | Medium |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).