Introduction

The Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) is a hospital unit that provides diagnosis and treatment of children from 0 to 18 years of age with critical, life-threatening illnesses.[

1] The most seriously ill children and their families receive all-encompassing care from the personnel at PICUs.[

2] The goal of critical care is to maintain a child's quality of life as much as possible, in addition to preserving their life.[

3] Due to the high level of empathy that is required to care for children at PICUs and the complexity of the relationships with their families, working in these units is very specific.[

4].Split-hour work schedules, ethical dilemmas like incapacity or death, unclear prognoses such as severe congenital anomalies and extreme prematurity compound the work. Additional features are the highly technical nature of the provided care, the daily exposure to the physical and psychological suffering of these children and their families, and the exposure to some extraordinary and unpredictable situations.[

5] everything mentioned above has an emotional and professional impact on the picu staff, often even without the fact being realized by the practitioners.

these complex factors inevitably lead to the exposure of the personnel working in PICUs to distress and the risk of developing pathological conditions such as burnout syndrome or depression. Burnout syndrome was first introduced by Freudenbenger (1974) in the middle of 1970s and defined as a phenomenon, characterized by emotional wear of the worker, accompanied by a decrease in physical and psychological energy, and a significant lack of motivation at work. The three dimensions of burnout are thought to function in a continuum. “Exhaustion” usually develops first, in response to overload, being followed by negative reactions such as detachment – “depersonalization”. If these continue, severe repercussions to the life of the individual may occur, resulting in “diminished accomplishments.”[

6] Although there are other measures for determining the level of burnout, the most widely used one is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), created by Susan E. Jackson and Christina Maslach to gauge a person's experience of burnout.[

7] Furthermore, recent research has demonstrated that staff members in intensive care units also report high levels of work-related post-traumatic stress disorder.[

8,

9,

10] Physicians of all specialties from Europe, Australia, and USA report that the main factor contributing to burnout is the repetition of night work in the form of in-house on-call duty, with the total number of hours worked per week being a risk factor for severe burnout.[

11,

12] In 2018, seven French neonatal intensive care units of III level of competence participated in a study that included the Maslach burnout test. The results showed that 15% of healthcare professionals are at high risk of burnout, with a wide disparity by profession: 22.6% among doctors and 11.6% among nurses. [

13] Critical care staff members are at an increased risk of psychological problems due to constant exposure to grief, trauma, and death. Those who work with children are particularly vulnerable.[

14,

15,

16] Situations in which quick and critical decisions are made without taking into account their accuracy or the consequences are not to be ignored. They affect the physician who is directly responsible for the consequences both emotionally and mentally. Nevertheless, fewer studies have looked at the possible risk or protective factors linked to burnout, and even fewer have looked at the prevalence of burnout among PICU staff.[

16] Given that burnout can negatively impair a physician's physical and mental well-being as well as their sense of self in the workplace, it is evident that high levels of burnout among health professionals have significant clinical and health effects on the system which in turn could have a detrimental effect on staff recruitment and retention as well as on the quality, safety, and satisfaction of patient care. [

19,

20,

21]

Bulgaria does not currently have a distinct specialty for working in PICUs or a specific status for employees as has been implemented in the majority of countries. Since PICU activities are of high cost, public medical institutions fail to invest enough additional funds in equipment and medicines in them. While private medical facilities aim to recruit and retain the best medical personnel, they do not want such wards as an addition to their infrastructure. This creates opportunities for high turnover of experienced and highly qualified medical staff. The staff has a great deal of responsibility for the lives of youngsters who are in critical condition. Along with treating the patients, the team is in close contact with the families and experiences every emotion of theirs. Working extra and overtime are frequently required. All of this has an impact on employees' emotional states and, in turn, on the quality of their work. Despite the urgent need to inform the wider health community and emphasize the need for extra care in PICUs, burnout among PICU staff has not yet been investigated in Bulgaria.

Aims, Participants and Methods

The aim of the current study was to evaluate burnout syndrome in PICUs' higher medical staff. The study took place between September and December of 2023. For the purpose of international comparisons in order to objectify the risk factors for burnout we preferred to use a survey that was used in a similar study in France, we utilised a survey that was validated and published in Acta Paediatrica (

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com) in June 2023. Permission was obtained, from the authors of the survey (Elodie Zana-Taïeb and team) for translation and adaptation to both Bulgarian language and Bulgarian working conditions. Its translation and adaptation was carried out by a doctor with one specialty, working for more than 5 years at PICU and and revised by a supervisor – a professor, head of the same structure. Some context and cultural adaptations were needed, primarily in terms of the organisation of the working environment and personnel structure. We followed the Cross-Cultural Survey Guidelines of the University of Michigan (

https://ccsg.isr.umich.edu/chapters/adaptation/0).

The survey, containing 93 questions, was first made available online through the Google

Forms platform. Since the study was carried out online, no funding was utilized. Initially it was distributed to the heads of the five existing PICUs in Bulgaria, all affiliated to university hospitals – Department of Paediatric Anesthesiology and Intensive Care "N.I. Pirogov" – Sofia, Department of Intensive Treatment of Children's Diseases "Prof. Dr. Ivan Mitev" – Sofia, Paediadric Cardiology Intensive Care Unit in National Cardiology Hospital – Sofia, Paediatric Intensive Care Unit "St. Georgi" – Plovdiv, and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit "St. Marina" – Varna for review and opinion (

Figure 1). Once the final version of the survey was completed and approved, it was made available to the survey respondents. The total number of fully employed higher medical personnel at the units was also reported by the unit heads. Since Paediatric intensive care is not a recognized specialty in Bulgaria, physicians from various specialties may work in these wards.

The participants in the current survey worked in PICUs with 5 to 10 beds each. All physicians who worked in these structures were given the survey at the initial stage of the study. Temporary residents and trainee physicians were excluded from the study. It was anonymous and included questions from the following groups:

gender, age, and status of the medical facility;

specialty(ies) of the respondent;

working hours, number of shifts, workload;

recognition and discrimination at the workplace;

emotional stress related to work, family situation, non-professional activities;

monthly remuneration and overall professional satisfaction.

The study was conducted in compliance with the criteria of the Helsinki declaration. An explanation of the survey's objectives, the amount of time required to complete it, and the guarantee that respondents would stay completely anonymous were provided at the outset. The decision of the potential participants to continue with the survey was taken as consent, and this was explicitly stated in the text. The study was retrospectively approved by the Research Ethics committee at the Medical University of Varna/Bulgaria (№ 10/27.02.2025). SPSS for Windows, version 22, was used for the statistical work-up. Descriptive, correlational, and comparative analyses were included (p<0.05 was considered a significant value). For most of the questions, the number of answers is less than the overall number of participants. For clarity, the relative shares are shown in brackets alongside the number of answers.

Results

There were 43 full-time, higher education medical staff members working in five PICUs in the country. The survey was completed by 37/43 (86.05%) respondents – two clinical psychologists and 35 physicians who worked in the PICUs – over the course of four months, from September to December, 2023. More women than men took part in the study, as women represent 73% (n=27) of the respondents. Doctors between the ages of 30 and 40 made up the biggest percentage, accounting for 62.2% (n=23) of all respondents. The medical staff's average age was 36.6±7.6 years. The majority of them (81.1%, n=30) were married, and half of them (51.4%, n=19) thought that their jobs could interfere with their relationship. Partners who voiced skepticism or discontent with their work were 29.7% (n=11).

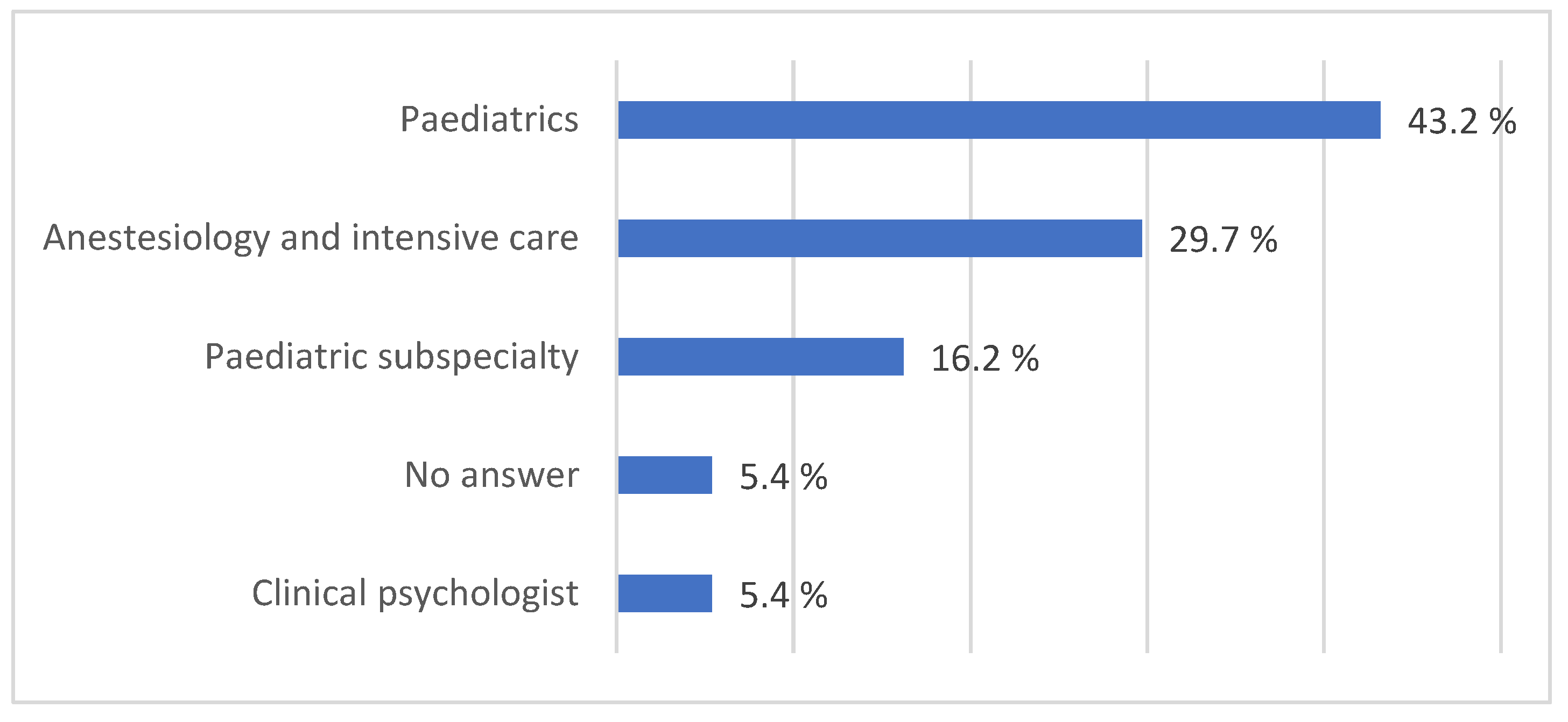

Of all respondents, 29.7% (n=11) had the specialty of anesthesiology and intensive care, while 43.2% (n=15) had the specialty of paediatrics, those with paediatric subspecialties comprised 16.2 % (n=9), and two clinical psychologist were also included, 5.4% (n=2) (

Figure 2).

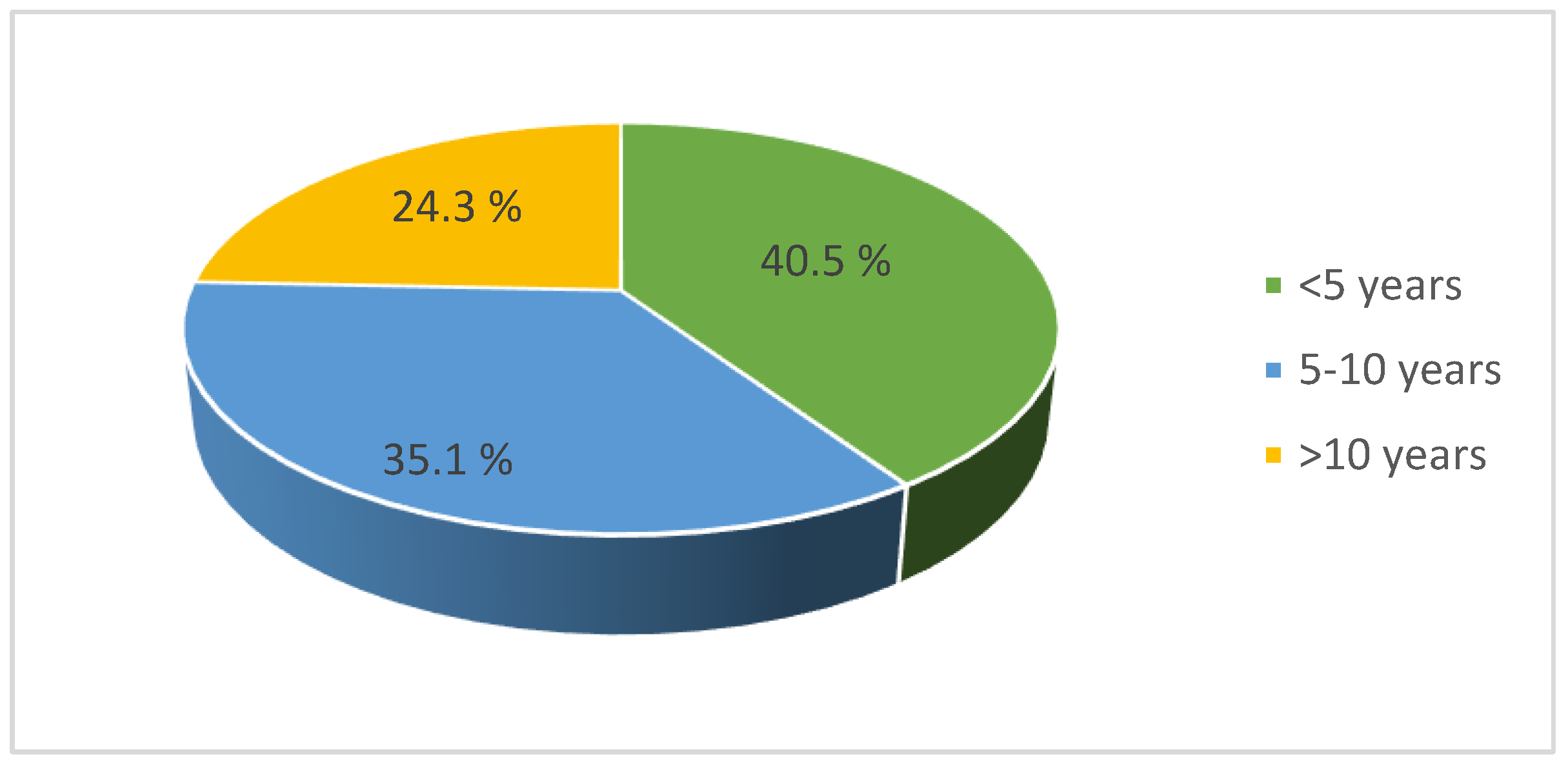

The majority of the respondents had fewer than five years of work experience (

Figure 3). Those with five to ten years of experience made up the next largest category. Of the employees, 70.3% reported that they worked 40–50 hours a week, while 23.5% worked more than 50 hours. While there was no significant difference between work experience and burnout (p=0.565), there was a significant link between weekly working hours and burnout (p=0.045).

Nearly two-thirds of the respondents (73%, n=27) described their workload as heavy but manageable, while 48.5% (n=15) of the participants reported that they occasionally felt overburdened by their work at the medical facility. Half of the respondents felt insecure in the work process, with 70.3% (n=26) attributing this to work overload.

A quarter of the respondents (27.0%, n=10) were additionally burdened with institutional responsibilities. The respondents with a researcher’s profile made up 62.2% (n=23) and those with teaching responsibilities – 41.0% (n=21) of the university faculty. Because therapeutic and scientific activities were conducted concurrently, this had an additional detrimental effect on the employees. However, statistical data revealed no association between burnout and teaching (p=0.479). Almost all (89.2%, n=33) provided shifts, with 75.7% (n=28) working in the ward and 18.9% (n=7) working both on-site and on-call, which reduces the amount of time needed to relax and recover before the next shift. For 83.8% (n=31) of all, the duty lasted 12 hours. Nearly half of the responses indicated there was no doctor on call at all times, whilst 29.7% of the wards had at least one doctor on call at all times. Average shifts per month were more than 12 for 37.8% (n=14) respondents. Out of all, 75.7% (n=28) said they always or occasionally took breaks during work, whereas 21.6% (n=8) said they had no time for rest. Of those working, 43.24% (n=16) had to perform administrative tasks during their free time, and 32.4% (n=12) were engaged in scientific activities mostly in hours outside the working time or used some of the spare time for hobbies. Against this background, 73.0% (n=27) of the respondents defined work as a source of intellectual stimulation.

Working from home in their free time was reported by 40.5% (n=15) of the respondents; 67.6% (n=25) visited the workplace sometimes or often on weekends even when they were officially not at work, and only 10.8% (n=4) said they were not available outside working hours. Of all, 59.4% always or frequently considered the legal aspects of intensive care (n=22). Of them, 58.8% (n=10) were significantly impacted by this (8–10 on the ten-point Likert scale), and 45.9% (n=17) were questioned during court proceedings. Only 8.1% (n=3) reported no emotional burden, but 70.2% (n=26) reported experiencing emotional burden frequently and always as a result of their profession, including the stress of handling life-threatening situations.

Over 50% of the physicians (54.1%, n=20) occasionally considered leaving their current medical facility to work in the private sector (Figure 4). More than 10% frequently considered quitting. Of the respondents, 78% (n=29) thought that an increase in the monthly remuneration would prevent the orientation of PICU doctors from joining the private sector. After leaving their workplace; 62.2% (n=23) of the respondents reported that they could not "break away" from work entirely; 75.7% (n=28) coped moderately with the psychological burden of the cases they treated; 5.4% (n=2) said they couldn't handle it at all.

An episode of overheating, depression, and anxiety disorder was experienced by 73% (n=27), and 75.6% (n=28) reported sleep problems. The statistical analysis showed no significant difference between burnout and sleep disturbances (p=0.705). More than once a week, 75.6% felt exhausted from work and 24.3% (n=9) defined themselves as "crushed". Emotional exhaustion was reported by 43.2% (n=16) of all respondents; 64.8% (n=24) were convinced that they worked too much at least once a week or more often; 37.8% (n=14) of respondents used less than 25 days of annual leave; and 37.8% (n=14) had to interrupt their annual leave at least once due to administrative reasons. There was no significant correlation between interruption of the annual leave and burnout (p=0.548). Over half of the respondents (51.4%, n=19) reported feeling pressured occasionally while on vacation.

Of the total, 51.4% (n=19) were not satisfied with their social life outside of medicine. Only 16.2% (n=6) were completely satisfied with their monthly salary; 64.9% (n=24) expressed only moderate satisfaction; the remaining (18.9%, n=7) were completely dissatisfied. Less than a third of the respondents (27%, n=10) received under BGN 2,000 (roughly 1,000 Euro) salary (Figure 5). The target salary of 45.9% of the respondents was over BGN 5,000 (2,500 Euro) monthly. There was no additional remuneration for being on duty for 45.9% (n=17) of the respondents, and 43.2% (n=16) defined their duty as worth more than BGN 250 (125 Euro). Surprisingly, no significant correlation between monthly remuneration and burnout was found (p=0.442). Once again, there was no significant association between the target salary and the doctors' specialization (p>0.05), nor was there a significant correlation between the target salary and the specialists' age (p>0.05). Significant correlation was not found between work experience and target salary, work experience and monthly remuneration (p>0.05).

The quality of professional life was satisfying for 43.2% of the specialists, and 56.8% (n=21) had never considered changing the field in which they worked; 70.3% (n=26) reported that they would choose to work with children again. Respondents listed the following as some of the changes they would want to see implemented into their workplace:

family time,

no obligations to administration,

less workload with teaching and scientific work,

better payment,

provision of psychological support for medical personnel,

more qualified staff,

better equipment,

a moderate seven-hour workday for every intensive care unit,

additional annual leave and extra time provided for continuous education and training.

Young physicians with fewer than five years of experience desired more practical training, greater organization of their work, higher-quality and better structured training, adherence to well recognized clinical guidelines, and assistance from a specialist throughout their shifts. Outside the context of a PICU, they wanted a better organization of the health care system, less bureaucracy, and better payment; the possibility of using longer (at least 3 weeks) vacations twice a year; and an overall improvement of the material base in the PICUs.

Discussion

The current study shows for the first time quantitative data on the quality of life at the workplace of Bulgarian doctors, working in PICUs, provides sound evidence about substantial burnout, and suggests areas of improvement. In 1967, John Downes opened the first PICU in the United States at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.[

22] Intensive care services are now a crucial component of healthcare in developed nations.[

23] Although paediatric intensive care emerged as a new specialty in the field of medicine in the 1960s, with the awareness that a separate subspecialty is required to care for critically ill paediatric patients,[

24] it is still not recognized as a separate specialty in Bulgaria.

Burnout among healthcare professionals is a worldwide issue that has a detrimental effect on staff productivity, patient safety, care quality, and medical staff recruitment and retention. Healthcare workers that experience burnout suffer psychologically and physically, which affects patient care.[

25,

26] It is therefore not unexpected that the majority of the workforce in the current study has worked in PICUs for less than five years, and that more than one in four doctors in PICUs have less than ten years of work experience. Burnout was more common among physicians than among their peers in the US, according to a survey of US medical students and residents.[

27] PICU staff are particularly at risk, with reported prevalence ranging from 40% to 70%.[

28,

29,

30] The present, study reporting over 70% of employees experiencing distress burden, is not an exclusion. In terms of staff issues, it establishes the foundation for comparing the country's critical case medical care quality with that of other counties.

The working conditions and the specific activities, performed at PICUs can have significant consequences on the practitioners’ mental health. It should come as no surprise that in the present study over two thirds of the doctors report feeling insecure in the work process. This portion of the burden may be lessened in the near future by the potential for assisted medical decision making and the significant advancements in AI technology. Healthcare systems have to be flexible in their swift introduction. The young staff in PICUs is among the best candidates to quickly adapt to new technology. [

31]

The current results demonstrate that PICU staff members already suffer from severe burnout and disrupted personal lives, with over half of the participants experiencing legal issues related to their work. We acknowledge that this may be made worse by the fact that hospital staff support is still poorly organized and legal liability is a relatively new phenomenon in the country. Additionally, the study unequivocally demonstrates the higher percentage of female participants compared to male participants. Being the most numerous group in PICUs may be a sign that women act with responsibility and dedication in their professional life. Alternatively, it may just reflect the fact that Paediatrics attracts more women, perhaps in connection with motherhood as a contributing factor for choosing the specialty. Paediatrics in general is dominated by women.[

32] Historically, the sociological assignment of childcare as a woman’s role made it also easier for female doctors to enter Paediatrics.[

33]

The medical staff in this study is of young age, probably because this is the most comprehensive specialty in medicine as it covers diseases from the neonatal period, infectious diseases, surgical diseases, traumatology, and diseases of all organs and systems. The majority of the respondents emphasized the need for higher remuneration and improved working conditions (reduced total working time, longer yearly leave, less night shifts). All this would only be possible if Paediatric Intensive Care is recognized as a separate specialty in Bulgaria, like in other countries. In 2020, an article, examining the current situation of the paediatric intensive care specialty and Paediatric intensive care units, was published in Turkey. It showed that there are 60 Paediatric intensive care units managed by Paediatric intensive care specialists.[

34] The current study showed that the majority of doctors in PICUs are paediatricians or other types of paediatric specialists. This is a reason to believe that with the acceptance of the new specialty in Paediatric Intensive Care the leading physicians will have primarily paediatric background.

Despite the poor working conditions, the majority of the staff was dedicated and willing to work without complaining. If the monthly salary was increased and the weekly workload was reduced, they would have the opportunity to recover after duty, have time for their families, and time for personal commitments. This would also increase the quality of service. Otherwise, over 16% of the respondents were currently thinking of changing jobs. This is not a very high percentage of employees considering all issues mentioned above. It is consistent with research from other countries, such as 18% in Ireland in 2018.[

35]

Professional dissatisfaction has been found to be associated with increased general dissatisfaction, burnout, reduced commitment to clinical practice, and turnover among the most experienced professionals. This subsequently leads to a decline in the quality of patient care. Patients who are treated by doctors satisfied with their profession, receive a better quality of care.[

36,

37] The major feedback from the respondents was the excessive weekly work, overtime, and insufficient remuneration for being on duty. It is important to mark that the respondents desire for higher salary was not tied to whether they were married, had children, their work experience, number of duties, gender or kind of specialty. Family obligations should not be neglected, as more than half of the respondents claimed that this could impede work and eventually cause overheating. Because of the detrimental effects of prolonged work in an intensive care unit, employees wanted their job to be adequately paid or compensated for. A decision of the European Court of Justice of 14 May 2019 sets an average working time for a seven-day workweek of 48 hours, including overtime, for a typical 4-month reference period. More than two-thirds of the physicians who participated in the present survey reported working for 40-50 hours per week, with almost a quarter reporting work exceeding 50 hours per week. This could be compensated for by periodically assigning employees to wards with less rigorous work for a set amount of time, providing specialization and observation in another city or country. Such an approach would stimulate both a "break" from work and an enrichment of knowledge in the field, which in turn would lead to an improvement in the quality of intensive care units.

According to the sample study, burnout rates among French physicians ranged from 28% to 73% across all disciplines, with rates among emergency medicine specialists being higher. The number of night shifts was linked to an even higher rate of burnout, in accordance with our study results.[

38] Employees working in non-university or private centers seem to be more satisfied with their work. Almost 2000 registered professionals were asked to rate the sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in New Zealand. Overall satisfaction was higher and dissatisfaction scores were lower in the private sector among 47% of the respondents. More clinical autonomy, strategic influence, and a stronger sense of being valued were the reasons for being engaged in private practice.[

39] The respondents in our survey reacted negatively to administrative workload. This fact may have an additional negative impact on physicians, as clinical and scientific activities were conducted concurrently. Surprisingly, there was no correlation between teaching, research, and burnout. This highlights the well-known fact that creative work protects against burnout and justifies the place of PICUs in university hospitals.[

39,

40]

To provide the necessary care for critically ill patients and their families, physicians must be in a favorable psychological state, satisfied with their work, and appreciated by their environment. As a result, the pediatric intensive care units could provide higher-quality care. Healthcare workers who experience psychological instability face a variety of personal and professional challenges, including decreased productivity, poor quality of care, absenteeism due to health or other reasons, use of psychoactive substances, smoking, alcohol use, interpersonal stress, as well as inferiority in family relationships.

This is the first study to investigate how work environment, work structure, working hours and working conditions affect the psychological wellbeing and contentment of employees in Bulgarian PICUs. A significant portion of the personnel (around 70%) would still choose to work with children in spite of the challenges they encounter on a daily basis. In addition to offering them better working conditions and greater compensation, the high percentage highlights the fact that such healthcare professionals work with love and passion which should be appropriately acknowledged. The identification of paediatric intensive care as a specialty and its separation from both paediatrics and adult critical care seems to lead to a higher standard of treatment in PICUsand more young people, interested in pursuing jobs in this field, may be attracted as a result.

Our study had limitations, since it was the first quantitative study on the quality of life of Bulgarian doctors at PICUs as their workplace, and there was no basis for comparisons with previous data. The number of responses to this questionnaire was high for the short time of the study and representative for the overall work force at PICUs, but apparently small for performing a quantitative analysis, as many of the trends did not reach statistical significance. The weekly overtime and inadequate compensation for the shifts were the primary causes of discontent. The working conditions and the specifics of the PICUs activities could have significant consequences on the mental health of the practitioners, and hence a decline in the quality of service. Such studies can help raise awareness of the actual risk of burnout for PICU workers by being conducted on a regular basis and can lead to the development of effective interventions for promoting the sustainable well-being of healthcare practitioners. A similar study will be conducted among health care workers (nurses, midwives, etc.) working in PICUs as the emotional and psychological burden is likely to be comparable.

Conclusion

This is the first evaluation of burnout among Bulgarian physicians employed in paediatric intensive care units. They deal with challenges on a daily basis that may negatively affect their emotional well-being and the quality of their work. Along with the responsibilities assigned to them, they must handle emergency situations, communicate daily with the relatives of the critically ill children, and often have to deliver bad news. The main reasons for dissatisfaction seem to be the excessive weekly working hours and the insufficient remuneration. Practitioners' mental health may suffer greatly as a result of the specialized nature of the PICU activities. Since the doctors in Bulgaria who want to work in PICUs are few, it is necessary to improve the working conditions in these departments. The doctors should feel appreciated and acknowledged for their work as paediatric intensive care providers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

References

- Köroğlu TF. Türkiye Çocuk Yoğun Bakım ve Çocuk Acil Tıp Hekim İnsangücü Raporu. Istanbul: Çocuk Acil Tıp ve Yoğun Bakım Derneği; 2008.

- Moynihan KM, Alexander PMA, Schlapbach LJ, Millar J, Jacobe S, Ravindranathan H, et al. Epidemiology of childhood death in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 2019;45(9):1262e71.

- Groeger Jeffrey S. MD at all, Descriptive analysis of critical care units in the United States. Critical Care Medicine 20(6): p 846-863, June 1992.

- Buckley L, Berta W, Cleverley K, Medeiros C, Widger K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: a scoping review. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Prentice TM, Gillam L, Davis PG, Janvier A. Always a burden? Healthcare providers' perspectives on moral distress. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103(5): F441-F445. [CrossRef]

- De Diego-Cordero, R., Iglesias-Romo, M., Badanta, B., Lucchetti, G., & Vega-Escaño, J. (2021). Burnout and spirituality among nurses: A scoping review. EXPLORE. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. (1981). "The measurement of experienced burnout". Journal of Occupational Behaviour. 2 (2): 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, et al: Increased prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:693–697 7.

- de Boer J, Lok A, Van’t Verlaat E, et al: Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, et al: Increased prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175:693–697 7. de Boer J, Lok A, Van’t Verlaat E, et al: Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic.

- Czaja AS, Moss M, Mealer M: Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among pediatric acute care nurses. J Pediatr Nurs 2012; 27:357–365.

- Kansoun Z, Boyer L, Hodgkinson M, Villes V, Lançon C, Fond G. Burnout in French physicians: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:132-147. [CrossRef]

- Zana-Taïeb E, Kermorvant E, Beuchée A, Patkaï J, Rozé JC, Torchin H; on the behalf of the French Society of Neonatology. Excessive workload and insufficient night-shift remuneration are key elements of dissatisfaction at work for French neonatologists. Acta Paediatr. 2023 Oct;112(10):2075-2083. Epub 2023 Jun 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basset A, Zana-Taïeb E, Bénard M, et al. Nurses and physicians at high risk of burnout in French level III neonatal intensive care units: an observational cross-sectional study. J Perinatol. 2022;42(5):669- 670. [CrossRef]

- Van Mol, Margo MC, et al. "The prevalence of compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units: a systematic review." PloS one 10.8 (2015): e0136955.

- Vincent L, Brindley PG, Highfield J, Innes R, Greig P, Suntharalingam G. Burnout Syndrome in UK Intensive Care Unit staff: Data from all three Burnout Syndrome domains and across professional groups, genders and ages. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2019;20(4):363-369. [CrossRef]

- Crowe L, Young J, Turner MJ. What is the prevalence and risk factors of burnout among pediatric intensive care staff (PICU)? A review. Transl Pediatr. 2021 Oct;10(10):2825-2835. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, Rikinkumar S., et al. "Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review." Behavioral sciences 8.11 (2018): 98.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018 Jun;283(6):516-529. Epub 2018 Mar 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigl M, Schneider A, Hoffmann F, Angerer P. Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 2015 Sep;174(9):1237-46. Epub 2015 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan KM, Alexander PMA, Schlapbach LJ, Millar J, Jacobe S, Ravindranathan H, Croston EJ, Staffa SJ, Burns JP, Gelbart B; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Pediatric Study Group (ANZICS PSG) and the ANZICS Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation (ANZICS CORE). Epidemiology of childhood death in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Sep;45(9):1262-1271. Epub 2019 Jul 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler DS, Dewan M, Maxwell A, Riley CL, Stalets EL. Staffing and workforce issues in the pediatric intensive care unit. Transl Pediatr. 2018 Oct;7(4):275-283. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Epstein D, Brill JE. A history of pediatric critical care medicine. Pe diatr Res 2005; 58: 987-96.

- Tenner PA, Dibrell H, Taylor RP. Improved survival with hospitalists in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 847-52.

- Khanal A, Sharma A, Basnet S. Current State of Pediatric Intensive Care and High Dependency Care in Nepal. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17: 1032-40.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. "Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being." (2019).

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272-2281. Epub 2016 Sep 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014 Mar;89(3):443-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, et al: An official critical care societies collaborative statement-burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals: A call for action. Chest 2016; 150:17–26.

- Garcia TT, Garcia PC, Molon ME, et al: Prevalence of burnout in pediatric intensivists: An observational comparison with general pediatricians. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014; 15:e347–e353.

- Crowe S, Sullivant S, Miller-Smith L, et al: Grief and burnout in the PICU. Pediatrics 2017; 139:e20164041.

- Choudhury A, Urena E. Artificial Intelligence in NICU and PICU: A Need for Ecological Validity, Accountability, and Human Factors. Healthcare (Basel). 2022 May 21;10(5):952. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- AAMC. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019: Exploring Pathways to Equity. https://store.aamc.org/the-state-of-women-in-academic-medicine2018-2019-exploring-pathways-to-equity.html (2020).

- DeAngelis, C. Women in pediatrics. JAMA Pediatr. ume 169, 106–107 (2015).

- Dinçer Yıldızdaş, Dinçer Yıldızdaş; Current situation of pediatric intensive care specialty and pediatric intensive care units in Turkey: Results of a national survey, 2020.

- Russell H, Maitre B, Watson D, et al. Job stress and working conditions: Ireland in comparative perspective — an analysis of the European working conditions survey. 2018. Available:.

- Kravitz RL. Physician job satisfaction as a public health issue. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2012;1(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. [CrossRef]

- Zana-Taïeb E, Kermorvant E, Beuchée A, Patkaï J, Rozé JC, Torchin H; on the behalf of the French Society of Neonatology. Excessive workload and insufficient night-shift remuneration are key elements of dissatisfaction at work for French neonatologists. Acta Paediatr. 2023 Oct;112(10):2075-2083. Epub 2023 Jun 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T, Brown P, Sopina E, Cameron L, Tenbensel T, Windsor J. Sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction among specialists within the public and private health sectors. N Z Med J. 2013;126(1383):9-19.

- Humphrey C, Russell J. Motivation and values of hospital consultants in south-East England who work in the national health service and do private practice. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(6):1241-1250. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).