1. Introduction

Cataract surgery is the most commonly performed invasive surgical operation world-wide [

1,

2]. There are approximately 3.3 million cataract surgeries performed annually in the USA [

3]. Du

et al., reported that the incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery is 0.127% at 6 weeks and 0.195% at 6 months in the Medicare population [

2], while other studies reported that the incidence of acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis ranges from 0.03% to 0.2% [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Endophthalmitis is an infection of the eye that can rapidly result in substantial loss of vision and may require enucleation. Currently, the 4

th generation fluoroquinolones are often used preoperatively in association with cataract surgery in the US. However, the drawbacks of this treatment are the narrowing spectrum of action of this drug, the cost (~

$2000.00/gram of antibiotic in a 3 ml bottle), and the evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance among coagulase-negative

Staphylococcus endophthalmitis isolates [

7,

8]. It was previously reported that from 56 to 90 percent of organisms causing infection in postoperative endophthalmitis are Gram positive, the most common of which is

S. epidermidis [

9]. Moreover, there is concern that late-generation fluoroquinolones may be less effective in preventing endophthalmitis caused by methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [

10,

11]. Sharifi

et al. investigated the role of cost as a potential factor in choosing a specific antibiotic for the prevention of endophthalmitis, and they found that none of the fluoroquinolones were cost saving in all scenarios modeled [

12]. In contrast to the fluoroquinolones, cefuroxime (~

$2.33 / gram), cefazolin (~

$0.77 / gram), azithromycin (~

$3.66/gram), and tobramycin (~

$37.50 / gram), are quite cost effective, at current doses [

13]. Also, intracameral cefuroxime has proven to be efficacious in reducing postoperative endophthalmitis overall [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Similarly, Garat

et al. reported that the cefazolin was effective in treatment of endophthalmitis [

19]. In addition, tobramycin has proven useful in controlling both superficial and deep infections of the eye and ocular adnexa (i.e., blepharitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis, and endophthalmitis) [

20,

21].

We compared the effectiveness of combinations of cefuroxime, cefazolin, azithromycin, and tobramycin as possible replacements for moxifloxacin, in commercially available concentrations against both Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria associated with endophthalmitis. The significance of this research is two fold, medical and economics. Medically, it may reduce the possible emergence of antibiotic resistant mutant strains. The development of strain resistant to a combination of two antibiotics is far less than that of one antibiotic. Financially, an enhanced spectrum of efficacy against common ocular pathogens may reduce the incidence of endophthalmitis thereby reducing health care costs. In addition, the cost of the generics is considerably less than the fluoroquinolones.

2. Results

2.1. Individual Antibiotic Killing Ability

2.1.1. Cefazolin

Initially, the antibiotic killing ability was individually determined to find the minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBC) of each antibiotic, against Klebsiella pneumonia clinical isolate (CI), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 GFP, Staphylococcus aureus AH133 GFP, Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus CI 121, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CI 139, and Staphylococcus epidermidis CI using the Disc Diffusion (ZOI) and the Colony Forming Unit (CFU) assays.

When examining Cefazolin, Staphylococcus epidermidis CI and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 GFP remain resistant to all tested concentrations (

Figure 1A) and showed no zone of inhibition. The CFU assay confirmed the resistance of S. epidermidis CI and P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP against Cefazolin.

Figure 1B showed that even at the highest tested concentration of 128 mg/ml, there was an average of over six logs of both S. epidermidis CI and P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP recovered per disc. However, at the lower concentrations, cefazolin effectively eliminated K. pneumonia CI, S. aureus AH133, and two clinical isolates of Methicillin resistant strains.

Figure 1.

2.1.2. Cefuroxime

Similar to Cefazolin,

S. epidermidis CI and

P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP also remain resistant to most tested concentrations of Cefuroxime, except the 64 mg/ml concentration killed S. epidermidis Cl, as showed in

Figure 2B. As shown in

Figure 2A, there is an increase in the size of the ZOI for both

S. epidermidis CI and

P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP bacteria at 16 mg/ml of Cefuroxime, but the CFU assay showed that there are an average of over six logs and four logs of bacteria recovered per disc for

S. epidermidis CI and for

P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP respectively.

2.1.3. Azithromycin

Azithromycin was effective in 8 logs killing of all the bacteria tested except S. aureus at 8 mg/ml (

Figure 3B). It did not kill S. aureus at even higher concentrations, while killing two strains of MRSA. This is seen in both the ZOI study (

Figure 3A) and the CFU determination (

Figure 3B).

2.1.4. Tobramycin

Compared to Azithromycin, Cefazolin and Cefuroxime, Tobramycin is the most effective antibiotic against all six tested bacteria. The Zone of Inhibition for most bacteria increases as Tobramycin is increased from .0039 mg/ml to 8 mg/ml. However, as shown in

Figure 4A, Tobramycin did not show ZOI against

S. epidermidis CI until the concentration reached 1.0 mg/ml. Similar results were found by CFU assay as shown in

Figure 4B. The CFU assay showed that 0.125 mg/ml of Tobramycin effectively eliminated most bacteria except

S. epidermidis CI.

S. epidermidis CI remains resistant to Tobramycin until 1 mg/ml of Tobramycin, however Tobramycin never completely killed the

S. epidermidis even at 40 mg/ml.

The effects of Tobramycin alone can also be seen visually in

Figure 5, when observed by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy. Images of the

S. aureus GFP AH133 (

Figure 5. A,C,E,G), and the

P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP (

Figure 5. B,D,F,H), that remained on the control and Tobramycin discs. Bar Scale Equals to 200 µm.

2.1.5. Moxifloxacin

The Disc Diffusion (ZOI) and Colony Forming Unit (CFU) assays were also performed with Moxifloxacin, a current drug used in the treatment of endophthalmitis. As shown in

Figure 6, Moxifloxacin effectively eliminated

Klebsiella pneumonia CI,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 GFP

, Staphylococcus aureus GFP AH133, and two clinical isolates of Methicillin resistant strains, but it failed to eliminate

S. epidermidis CI.

2.2. Combinations of Antimicrobials

We selected concentrations of individual antibiotics and used these concentrations in an antibiotic combination study. The results allowed us to examine whether these antibiotic combinations, are additive, synergistic or antagonistic compared to their individual concentrations.

Combinations were tested by decreasing the concentration of the individual antibiotic in the combinations by a factor of two. This was used to find the minimum concentration of the antibiotic combinations that eliminated all six tested bacteria.

2.2.1. Cefuroxime and Azithromycin

As shown in

Figure 7, the lowest combination of Cefuroxime and Azithromycin that killed all (8 logs) of the bacteria tested was Cefuroxime (0.5 mg.ml) and Azithromycin (0.5 mg/ml).

2.2.2. Cefuroxime/Tobramycin or Azithromycin/Tobramycin

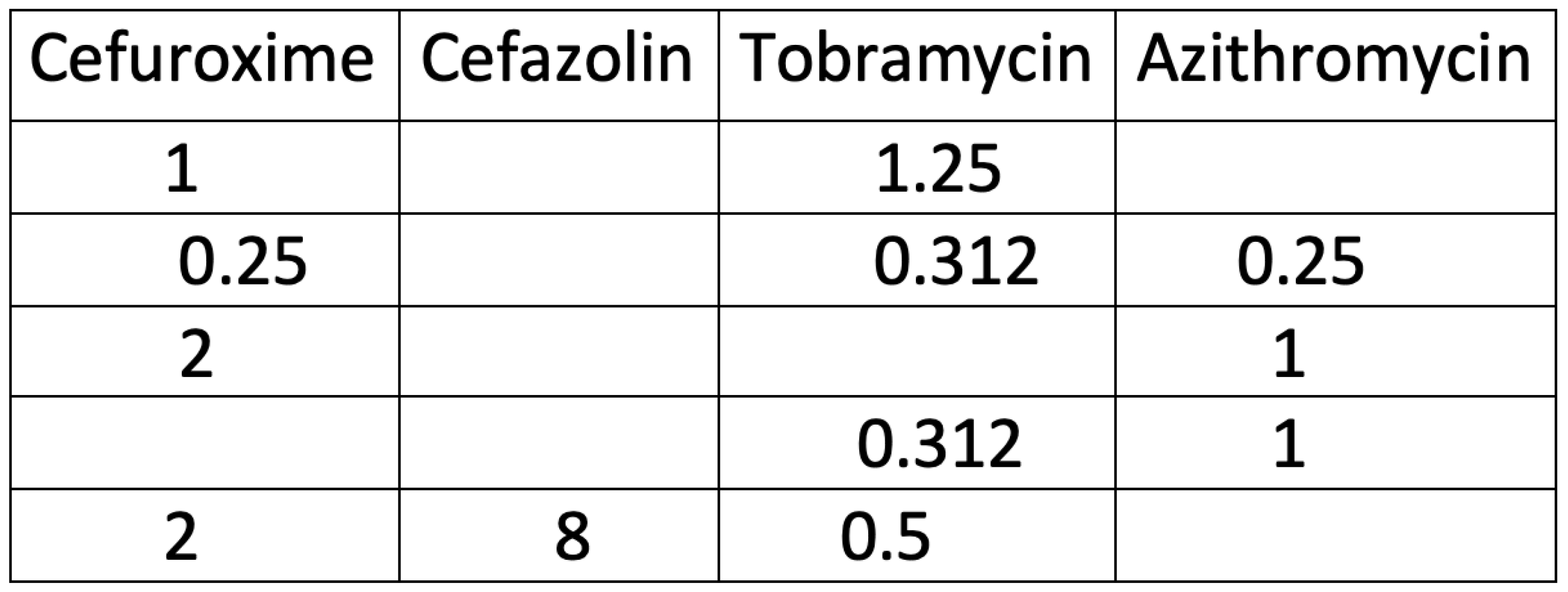

Similar experiments to those carried out with Cefuroxime and Azithromycin, were carried out with Cefuroxime/Tobramycin and Azithromycin/Tobramycin combinations. The lowest combinations that killed all 8 logs of bacteria are seen in

Table 1.

2.2.3. Cefazolin

The lowest concentrations for Cefazolin that would kill all 8 logs the bacteria tested had to be carried out in a triple combination. These results are seen in

Figure 8. The concentrations of individual antibiotics in the combination that eliminated all six bacteria is seen for the combination of 2 mg/ml of Cefuroxime, 8 mg/ml of Cefazolin and 0.5 mg/ml of Tobramycin. A triple combination of Azithromycin, Cefuroxime and Tobramycin was carried out (Figure not shown). It was found that the lowest combination where all the bacteria were killed (8 logs), was Azithromycin 0.25 mg/ml, Cefuroxime 0.25 mg/ml and Tobramycin 0.312 mg/ml.

2.2.4. Zone of Inhibition Results

With each of the antibiotics the ZOI assay was not as sensitive to changes in the inhibition of P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis as the CFU assay.

3. Discussion

The results showed that the double antibiotic combinations of Azithromycin, Cefuroxime and Tobramycin was synergistic and bactericidal against all Gram-negative and positive organisms tested. This is important because acute postoperative endophthalmitis have been shown to be caused by a broad spectrum of bacteria9.

A comparison of these double antibiotic combinations versus Vigamox (0.5% Moxifloxacin) found that Vigamox (0.5% Moxifloxacin) exhibited only 3-4 logs of inhibition of

Staphylococcus epidermidis CI

., while the different double combinations of Azithromycin, Cefuroxime and Tobramycin completely eliminated

Staphylococcus epidermidis CI (100% inhibition;

Table 1).

The resistance of Staphylococcus epidermidis CI against Vigamox (0.5% Moxifloxacin), a third generation fluoroquinolone, was confirmed by a previous study done by Schimel AM8. During 21.5 years of study, 168 patients were identified as having culture proven endophthalmitis caused by coagulase-negative staphylococcus8. In addition, despite the evolving mechanism of different generations of fluoroquinolones, the frequency of resistance to coagulase-negative staphylococcus continues to increase8.

The triple antibiotic combination of Cefazolin, Cefuroxime and Tobramycin, was also highly effective at eliminating against Klebsiella pneumonia clinical isolate (CI), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 GFP, Staphylococcus aureus AH133 GFP, Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus CI 121, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CI 139, and Staphylococcus epidermidis CI. The Zone of inhibition (ZOI) and CFU assays showed no growth for these six Gram-negative and positive bacteria.

A comparison of the different combinations can be seen in

Table 1. For topical ocular application, an important difference between our antibiotic combination solutions and Vigamox (0.5% Moxifloxacin) is that the combination was effective at much lower concentrations than when used as monotherapy. Cefuroxime worked at 2 mg/ml with Azithromycin or Tobramycin, while alone it is typically used topically at 25-100 mg/ml; Cefazolin worked at 8 mg/ml (triple combination) while it is used at 25- 100 mg/ml; and Tobramycin worked at 0.5 mg/ml with Azithromycin or Cefuroxime, while it is used a 14 mg/ml. Azithromycin was effective at 1 mg/ml in combination with Cefuroxime or Tobramycin, while alone it is used at 10mg/ml. When Cefuroxime’s concentration was dropped to 1 mg/ml there was no activity of the combination against

S. epidermidis CI.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

The laboratory strains of bacteria tested were S. aureus GFP AH133 [31] and P. aeruginosa PAO1GFP strains, which constitutively expresses green fluorescent protein from plasmids pCM11 and pMRP9-1 respectively [22.23]. The strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37ºC with shaking (250 rpm). To maintain pCM11 in AH133,LB was supplemented with 1 μg/ml erythromycin. To maintain pMRP9-1 in PAO1, LB broth was supplemented with 300 μg/ml carbenicillin. The clinical isolates studied were S. epidermidis, K. pneumoniae, and two strains of S. aureus, which are methicillin resistant (MRSA).

The efficacy of individual antibiotic solution was examined using LB broth medium (#113002022, MP Biomedical, Solon, OH)and LB-Agar medium (#113002222, MP Biomedical, Solon, OH, USA) as the growth medium. The clinical isolates were obtained from the Clinical lab at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center under an approved Institutional Review Board protocol, Texas Tech University Medical center/Lubbock, Texas, USA.

4.2. Antibiotic Solution Preparation

Tobramycin (#NDC 63323-306-02), cefuroxime (#NDC 25021-118-10), cefazolin (#NDC 0409-2585-01) were purchased from Cardinal Health, Dublin, OH, USA. Azithromycin (#NDC 55150-174-10) was purchased from Auromedics, East Winsor, NJ, USA., 5% Moxifloxacin hydrochloride (Vigamox) ophthalmic solution (#NDC 0065-4013-03) was purchased from Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Antibiotics were prepared in sterile dH2O into several stock solutions from the same batch following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Antibiotic solutions were prepared for each test from stock solutions stored at the manufacturer’s temperature recommendations. This was for consistency. For each experiment, antibiotic working solutions were made fresh on the day of inoculation. The range of antibiotic concentrations used for determining MICs were prepared in doubling dilution steps up and down from 1 mg/ml.

4.3. Disc Diffusion Assay

We used the disc diffusion testing method (zone of inhibition, ZOI) for our experiments as previously described.24 We then analyzed any remaining bacteria on the antibiotic discs using the viable count (Colony Forming Unit; CFU) assay. The disc diffusion testing method (ZOI) and CFU assay are standardized, reliable susceptibility testing techniques. Briefly, bacteria were grown overnight in LB medium. The following day, the bacterial culture was washed in Mueller Hinton (MH) broth (#70192,Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the bacterial suspension was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 (which is equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard of ~1 x 107 bacterial cell / mL) in MH broth according to the standard guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards.24 Following this, a sterile cotton swab was dipped into the adjusted bacterial culture, and a lawn of bacteria was made on a LB Agar plate using the dipped swab. The antibiotic discs were prepared by adding 20 μl of antibiotic solution onto 6mm diameter blank BD BBL Sensi-Disc Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Discs (#B31039, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Three antibiotic discs were distributed evenly onto an LB Agar surface. Three separate plates were measured, thus nine points were determined for each bacterial strain. The plates were then incubated at 37ºC for 24 h before the results were read and recorded. The diameters of the zones of complete and clear inhibition, including the diameter of the disc, were measured to the nearest millimeter with a ruler, however, the diameter of the disc was subtracted from all the measurements in the calculation and graphing

4.4. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) of the GFP Containing Bacteria

In addition to the disc diffusion study above, the discs from the S. aureus GFPAH133/pCM11 and P. aeruginosa GFPPAO1/pMRP9-1 plates were examined under the CLSM. S. aureus GFP and Pseudomonas aeruginosa GFP are lab strains, which constitutively express green fluorescent protein from plasmids pCM11 orpMRP9-1 when grown in the presence of 1 μg/mL erythromycin or 300 μg/mL carbenicillin respectively. Images were captured using the CLSM and comparison was made between the different concentrations of antibiotic and the control. Visualization of the S. aureus GFP AH133 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP bacteria was accomplished with a Nikon Eclipse Ti upright confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA).Samples were examined under 10X objective lens, FITC fluorescence to eyes laser (488.0 nm), 4 channel confocal, and 512 scan size. The images were processed and analyzed using NIS-Elements AR Imaging Software.

4.5. Determination of Viable Count Assay

The microorganisms remaining on the discs, following the disc diffusion assay, all strains were quantified by the CFU assay as previously described.[

25] Following incubation, each disc piece was transferred to a sterile 1.5-mL micro centrifuge tube containing 1mL of PBS (pH = 7.4) for enumeration of bacteria. The tubes were placed in a water bath sonicator for 10 min to loosen the cells within the disc and then vigorously vortexed 3 times for 1 min to detach the cells. Suspended cells were serially diluted (10-fold) in PBS, and 10-μL aliquots of each dilution were spotted onto LB Agar plates. In addition, the remained 900 μl zero dilution sample was also plated on a different LB Agar plate. Thus, the equation used to calculate the count was the recovered number of colonies ×dilution factor /inoculums size in ml. This means that if only one bacterial cell was originally in the tube we would have a 90% chance of detecting it. All experiments were done in triplicate on each plate, and all measurements were repeated on three separate plates. Thus, nine measurements total were carried out on each concentration.

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Results of the viable count assays (CFU) were statistically analyzed using GraphPad InStat 3.06 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance between pairs of values (Control versus one treatment group) was calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t test when SD was not significantly different and when a Gaussian distribution was observed. If SD was significantly different, the Welch correction was applied to the un-paired two-tailed t test. When non-Gaussian distribution was observed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), significance was calculated by a non-parametric Mann–Whitney test. Two treatment groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test (nonparametric ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for significance. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was ≤0.05.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study may be applicable to all types of eye surgery as well as for bacterial keratitis. The study showed that the combination of Cefuroxime, Azithromycin, or Tobramycin showed a synergistic effect and was superior to the individual antibiotics. In addition, this combination completely killed (8 logs, 100%) of all the tested bacteria. These different bacteria represent approximately 70% of the bacterial eye infections in the USA and 64% of those found in the world in 2023 [

26]. They included laboratory strains of

Staphylococcus aureus and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and clinical isolates of

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Staphylococcus epidermidis, and MRSAs. Moxifloxacin failed to kill the tested clinical isolate of

Staphylococcus epidermidis. Cefazolin had to be used in a triple combination to be effective. The combination of tested antibiotics showed enhanced efficacy, as well as enhanced value over that of Moxifloxacin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, d.m. and t.w.r.; methodology, p.t .; software, d.t.; validation, h.d., p.t., k.l., and p.l.; formal analysis, a.h.; investigation, h.d., k.l.,p.l. and s.m..; resources, p.t.; data curation, d.t.; writing—original draft preparation, t.w.r.; writing—review and editing, d.m., c.r. s.m.,and a.h; visualization, p.t.; supervision, t.w.r.; project administration, t.w.r.; funding acquisition, d.m. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The clinical isolates were obtained from the Clinical lab at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center under an approved Institutional Review Board protocol, Texas Tech University Medical Center/Lubbock, Texas, USA.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting results can be found archived in the TTUHSC Medical School Library.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

cefu, cefuroxime; cefa, cefazolin; azith, azithromycin; tob, Tobramycin; MBC minimal bacterial concentration; CFU colony forming unit; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; GFP. green fluorescent protein; LB, Luria-Bertani; NDC, National Drug Code; MH, Mueller Hinton; ANOVA, analysis of variance; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; SD, standard deviation; CI, clinical isolate; ZOI zone of inhibition;

References

- Lundstrom, M.; Friling, E.; Montan, P. Risk factors for endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Predictors for causative organisms and visual outcomes. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2015, 41, 2410–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.T.; Wagoner, A.; Barone, S.B.; et al. Incidence of endophthalmitis after corneal transplant or cataract surgery in a Medicare population. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yan, W.; Fotis, K.; Prasad, N.M. ; Lansingh V-C.; Taylor R.; Finger R.P.; Facciolo D.; He M. Cataract Surgical Rate and Socioeconomics: A Global Study. Invest Ophth & Vis Sci 2017, 57, 5872–5881. [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri, K.; Schwartz, S.G.; Kishor, K.; Flynn, H. W, Jr. Endophthalmitis: state of the art. Clinical ophthalmology 2015, 9, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friling, E.; Lundstrom, M.; Stenevi, U.; Montan, P. Six-year incidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Swedish national study. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2013, 39, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay.; Gower E.W.; Cassard S.D.; Tielsch J.M.; Schein O.D. Post cataract surgery endophthalmitis in the United States: analysis of the complete 2003 to 2004 Medicare database of cataract surgeries. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 914–922.

- https://www.alcon.com/. 04/23/2024.

- Schimel, A.M.; Miller, D.; Flynn, H.W. Evolving fluoroquinolone resistance among coagulase-negative Staphylococcus isolates causing endophthalmitis. Archives of ophthalmology 2012, 130, 1617–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelson, M.; and Forbes, M. The enigma of endophthalmitis. Rev Ophthalmology 2004;11.

- Blomquist, PH. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections of the eye and orbit (An American Ophthalmological Society Thesis). Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 2006, 104, 322–345. [Google Scholar]

- Major J.C., Jr.; Engelbert, M.; Flynn H.W., Jr.; Miller, D.; Smiddy, W.E.; Davis, J.L. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. American journal of ophthalmology 2010, 149, 278–283.e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Porco, T. C,.; Naseri A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intracameral cefuroxime use for prophylaxis of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 1887–1896.e1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- http://www.cardinalhealth.com/en.html.

- Barry, P.; Seal, D.V.; Gettinby, G.; Lees, F.; Peterson, M.; Revie, C.W. ESCRS study of prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Preliminary report of principal results from a European multicenter study. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2006, 32, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fintelmann, R.E.; Naseri, A. Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: current status and future directions. Drugs 2010, 70, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: results of the ESCRS multicenter study and identification of risk factors. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2007, 33, 978–988. [CrossRef]

- Seal, D.V.; Barry, P.; Gettinby, G.; et al. ESCRS study of prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Case for a European multicenter study. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2006, 32, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wejde, G.; Montan, P.; Lundstrom, M.; Stenevi, U.; Thorburn, W. Endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in Sweden: national prospective survey 1999-2001. Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica 2005, 83, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garat, M.; Moser, C.L.; Martin-Baranera, M.; Alonso-Tarres, C.; Alvarez-Rubio, L. Prophylactic intracameral cefazolin after cataract surgery: endophthalmitis risk reduction and safety results in a 6-year study. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery 2009, 5, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.S.; Mah, F.S. Comparison of tobramycin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.1% and tobramycin 0.3%, loteprednol 0.5% in the management of blepharo-keratoconjunctivitis. Advances in therapy 2007, 24, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmus, K.R.; Gilbert, M.L.; Osato, M.S. Tobramycin in ophthalmology. Survey of ophthalmology 1987, 32, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.L.; Boles, B.R.; Lauderdale K,J. ; Thoendel M.; Kavanaugh J.S.; et al. Fluorescent reporters for Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol Methods 2009, 77, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, B.W.; Krishnapillai, V.; Morgan, A.F. Chromosomal genetics of Pseudomonas. Microbiol Rev 1979, 43, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2025. Performance standards for antimicrobial disc susceptibility tests. Approved standard, 35th ed. CLSI publication M02-A10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- Tran, P.; Hamood, A.; Mosley, T.; Gray, T.; Jarvis, C.; Reid, T.W. Organo-selenium containing dental sealant inhibits bacterial biofilm. J Dent Res 2013, 92, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tweldemedhim, M.; Grebreyesus, H.; Atsbaha, A.H.; Asgendom, SW.; and Saravanan, M. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmology 2017, 17, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Cefazolin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Cefazolin discs was quantified by the Viable Count Assay (B).

Figure 1.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Cefazolin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Cefazolin discs was quantified by the Viable Count Assay (B).

Figure 2.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Cefuroxime discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Cefuroxime discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 2.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Cefuroxime discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Cefuroxime discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 3.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Azithromycin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Azithromycin discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 3.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Azithromycin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Azithromycin discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 4.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Tobramycin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Tobramycin discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 4.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Tobramycin discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Tobramycin discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 5.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy images of the S. aureus GFP AH133 (A,C,E,G), and the P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP (B,D,F,H), that remained on the control and Tobramycin discs. Bar Scale Equals to 200 µm.

Figure 5.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy images of the S. aureus GFP AH133 (A,C,E,G), and the P. aeruginosa PAO1 GFP (B,D,F,H), that remained on the control and Tobramycin discs. Bar Scale Equals to 200 µm.

Figure 6.

The bacteria remaining on the Moxifloxacin hydrochloride discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 6.

The bacteria remaining on the Moxifloxacin hydrochloride discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 7.

Cefuroxime and Azithromycin combination discs was quantified by the Viable Count Assay. Total killing (8 logs) of all bacteria tested were seen at 0.5mg/ml Cefuroxime and Azithromycin 0.5mg/ml. .

Figure 7.

Cefuroxime and Azithromycin combination discs was quantified by the Viable Count Assay. Total killing (8 logs) of all bacteria tested were seen at 0.5mg/ml Cefuroxime and Azithromycin 0.5mg/ml. .

Figure 8.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Tobramycin, Cefazolin, and Cefuroxime combination discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Tobramycin, Cefazolin, and Cefuroxime combination discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Figure 8.

The ZOI (A) of Gram positive and negative bacteria on the Tobramycin, Cefazolin, and Cefuroxime combination discs were measured in mm (the diameter of the disc was subtracted from total diameter of the zone) and the bacteria remaining on the Tobramycin, Cefazolin, and Cefuroxime combination discs was quantified by the CFU Assay (B).

Table 1.

Concentrations in mg/ml, which in a combination of antibiotics killed all (8 logs) of tested bacteria.

Table 1.

Concentrations in mg/ml, which in a combination of antibiotics killed all (8 logs) of tested bacteria.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).