Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

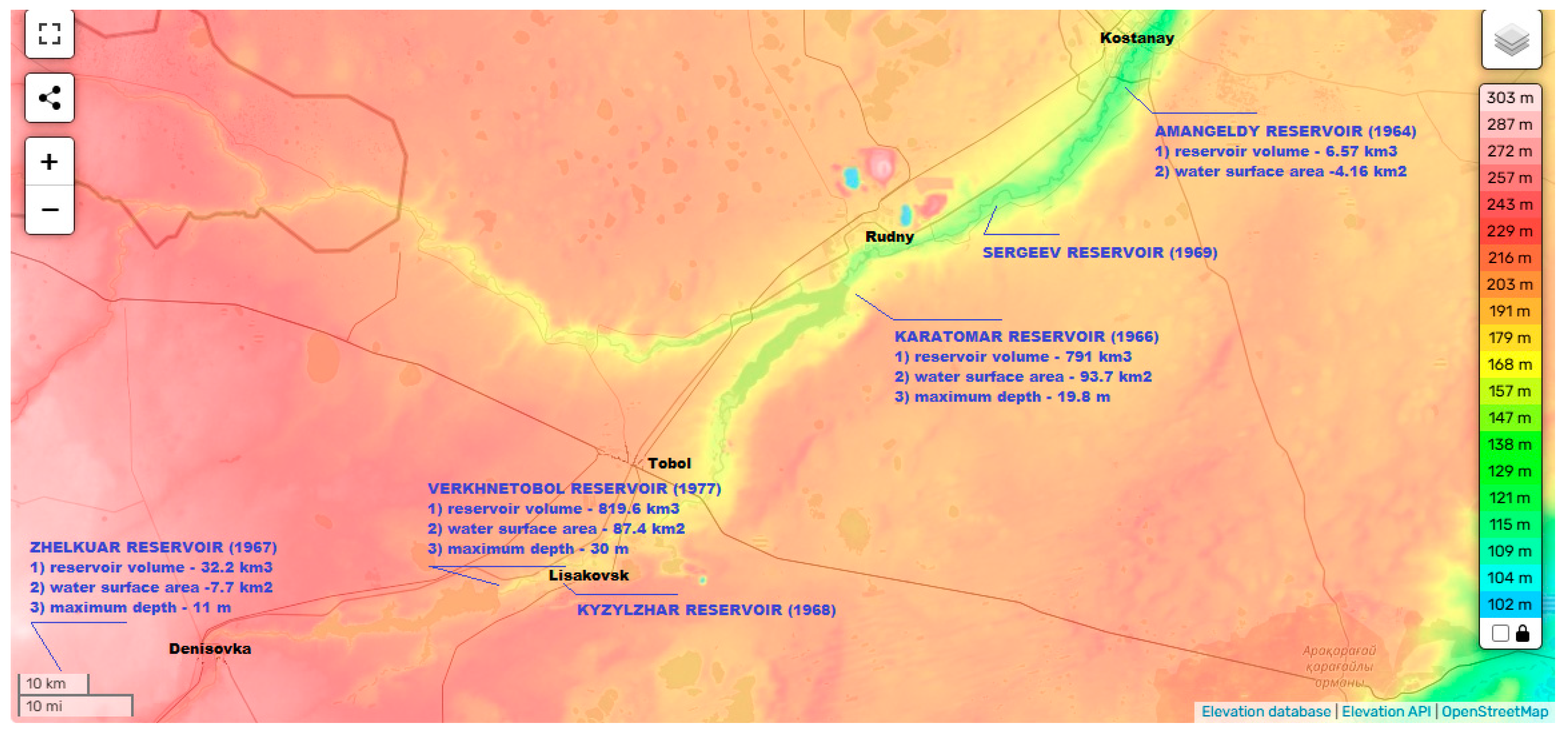

1. Introduction

- First, what is the real state of the Karatomar Reservoir after 78 years of operation;

- Second, how accurately does the bathymetric study convey the reservoir relief after interpolation of bathymetric data?

- Third, with what step of drone tacks should the bathymetric survey of the basins of flat reservoirs be carried out to achieve the required accuracy of 3D modeling?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

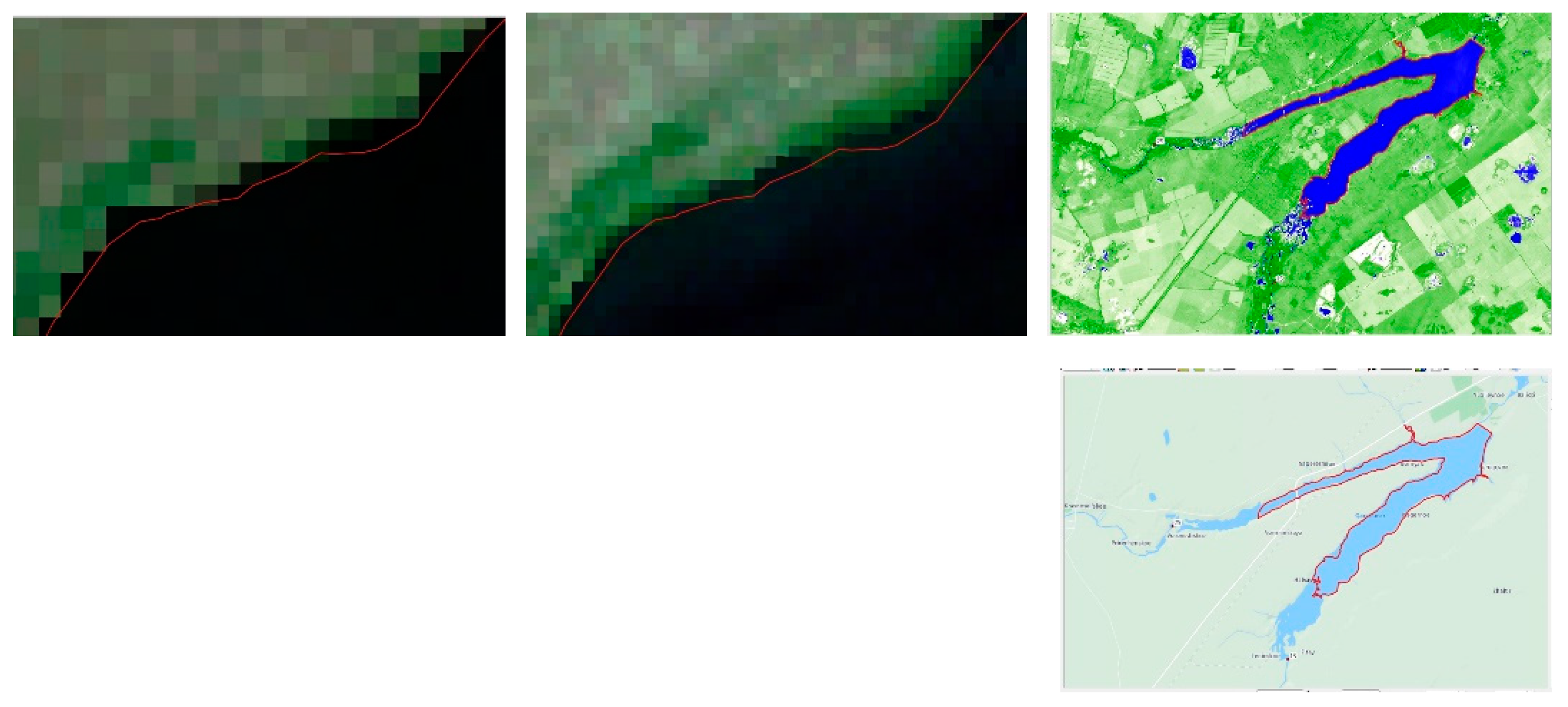

3.1. Analysis of Potential Methods for Studying Reservoir Bowls

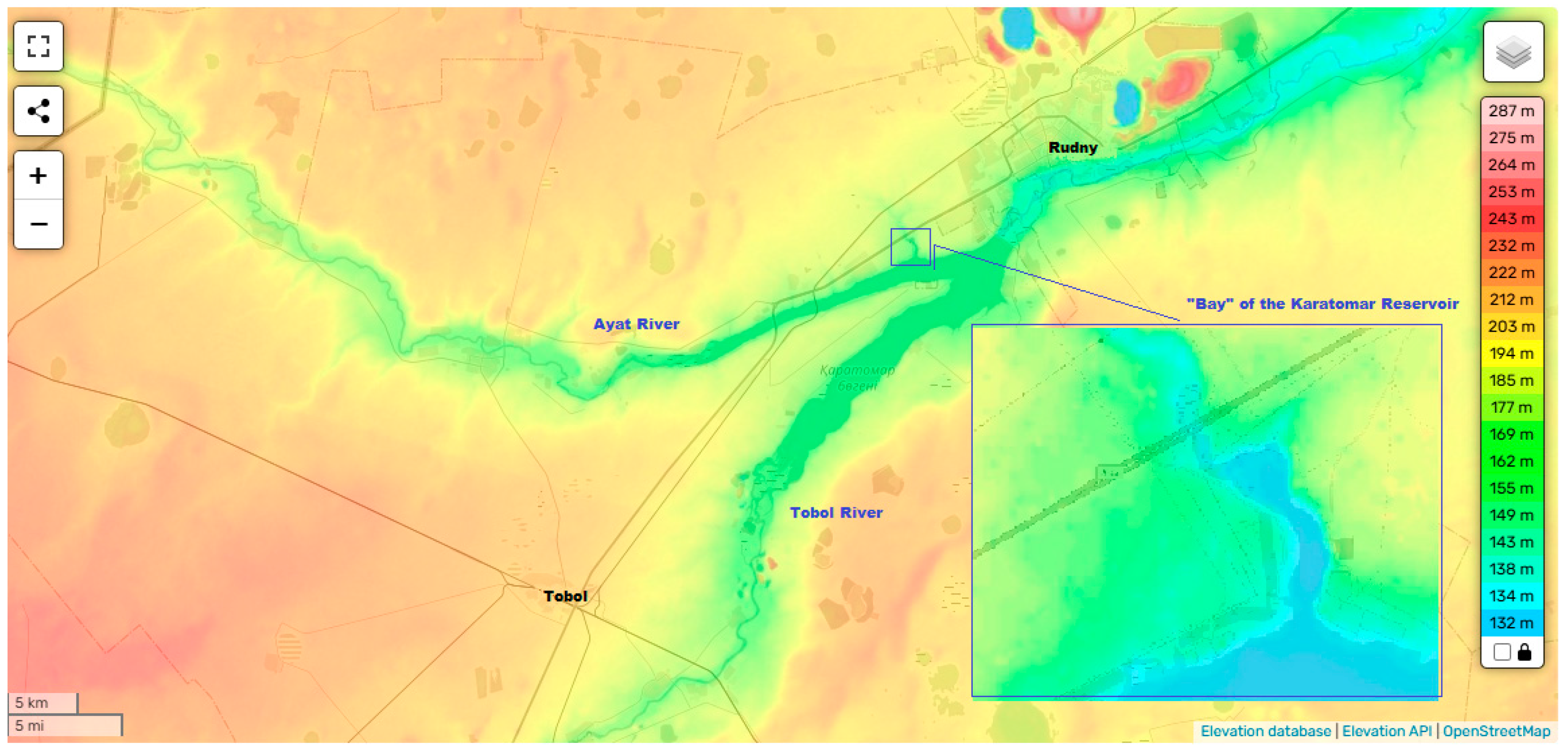

3.2. Analysis of Hydrogeology of the Tobol and Ayat Rivers in the Karatomar Reservoir Zone

- the hydromorphological picture is represented by alternating shallow riffles with shallow and medium-depth pools. The depth of the pools can reach up to 5 meters, and in some cases up to 10 meters or more;

- the river bottom is sandy-silty, rocky in places;

- the width of the channel varies from 50 to 400 meters;

- the banks are mainly loamy, overgrown with small bushes, slightly intersected by dry stream beds. The banks are steep, in places precipitous, 5-6 meters high, and at the confluence with the slopes of the valley they reach up to 30 meters;

- snow waters are predominant in the river's nutrition (70-90%). In winter, rivers are fed by underground waters, in summer - by underground waters, less often by rain;

- the water regime is characterized by a pronounced spring flood (up to 85-96% of the annual flow) and a long low water period;

- the mineralization of water during the spring flood period is 100-200 mg/l, and the hardness is 0.5-1.25 millimoles/l. In summer, the mineralization of water increases, the water becomes sulfate or weakly hydrocarbonate.

- the soils of the basin are mainly sandy and loamy, sometimes salty. Alluvial channels is located in a well defined river valley;

- the channel is gently winding, stretching, located in a well-defined river valley;

- the bottom of the river is sandy-silty, rocky in places;

- the width of the riverbed varies from 5 to 20 meters;

- the maximum water depth is 2 meters;

- the water regime is unstable, almost the entire annual flow occurs during the spring flood;

- due to large fluctuations in the water level, there are spits, islands-middens, and shoals on the river.

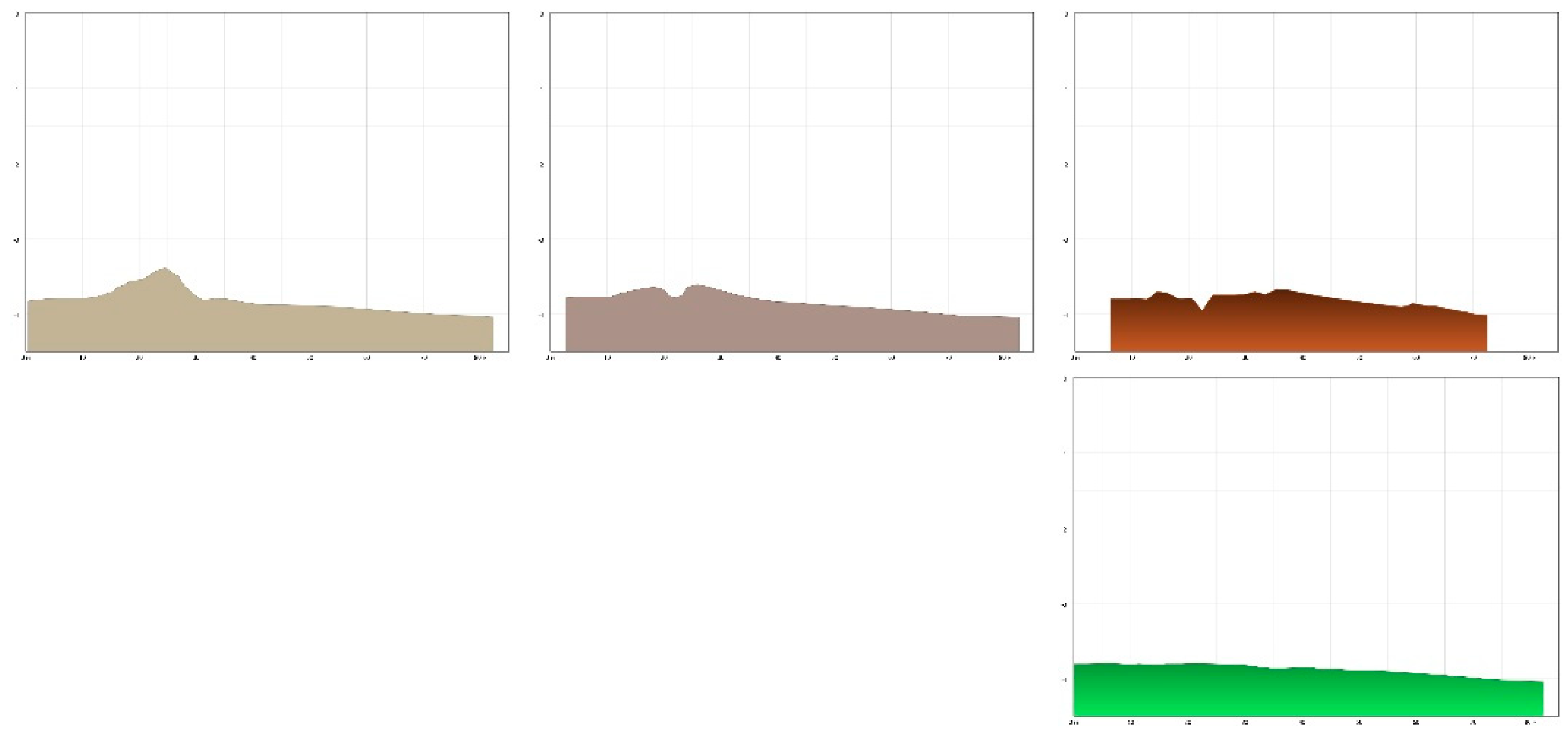

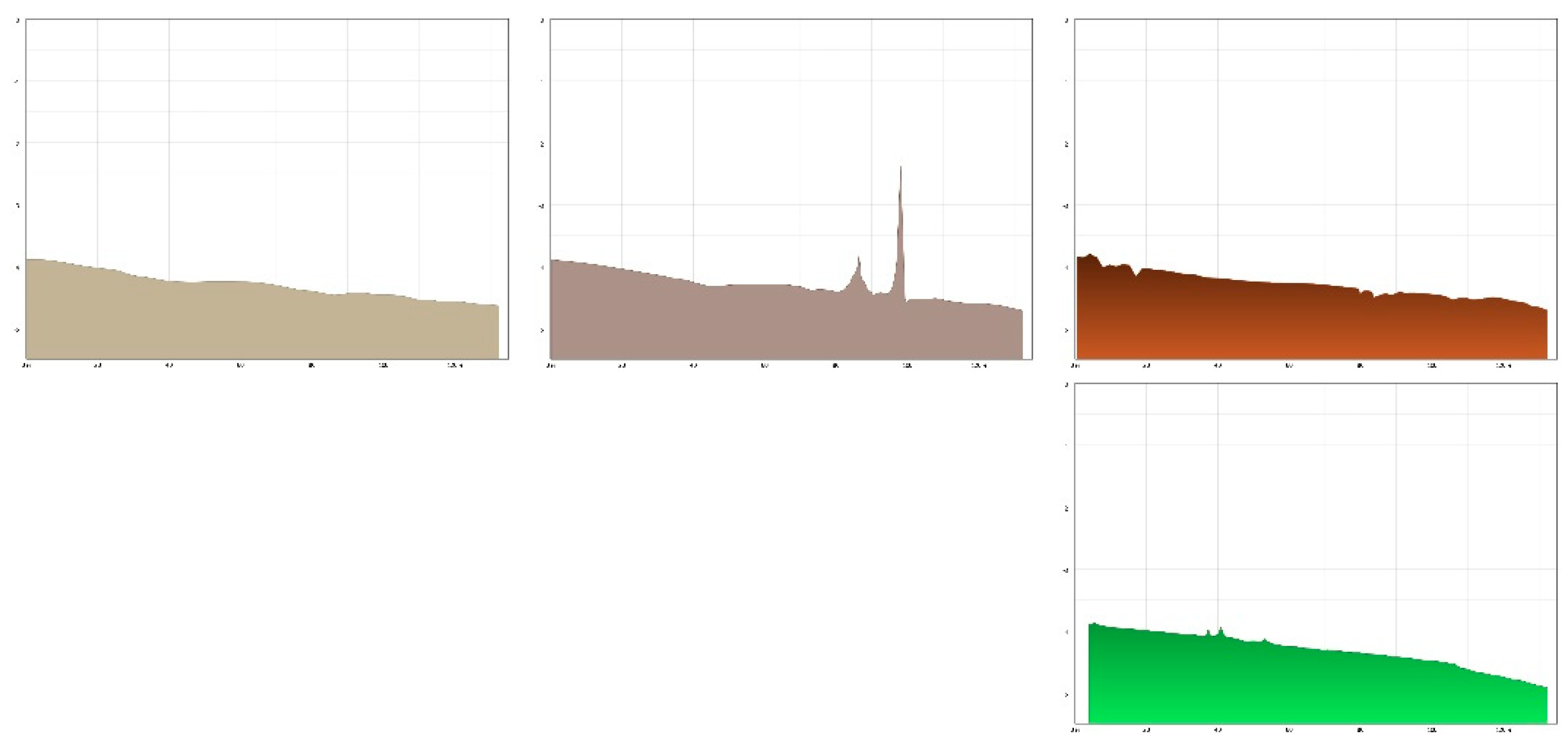

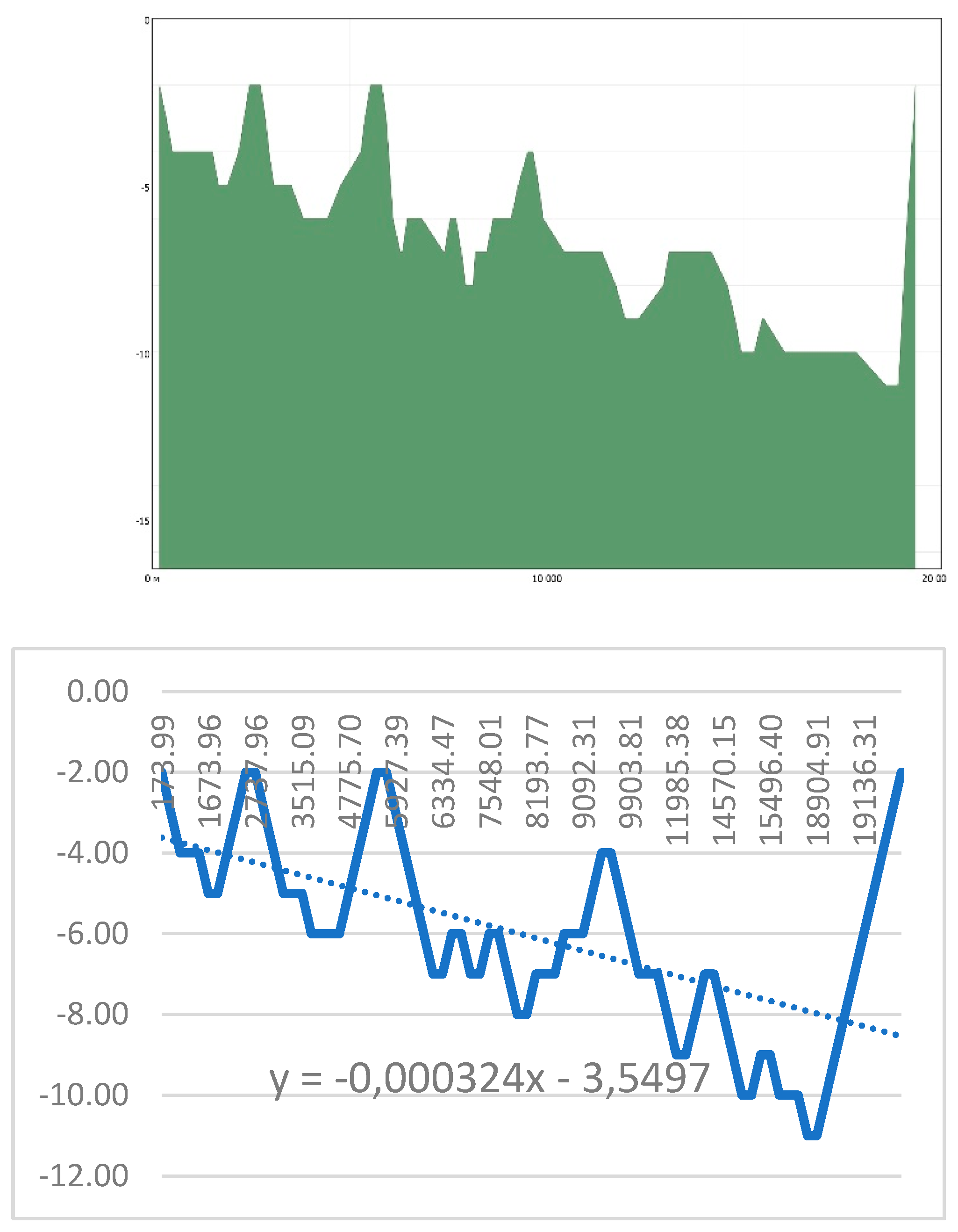

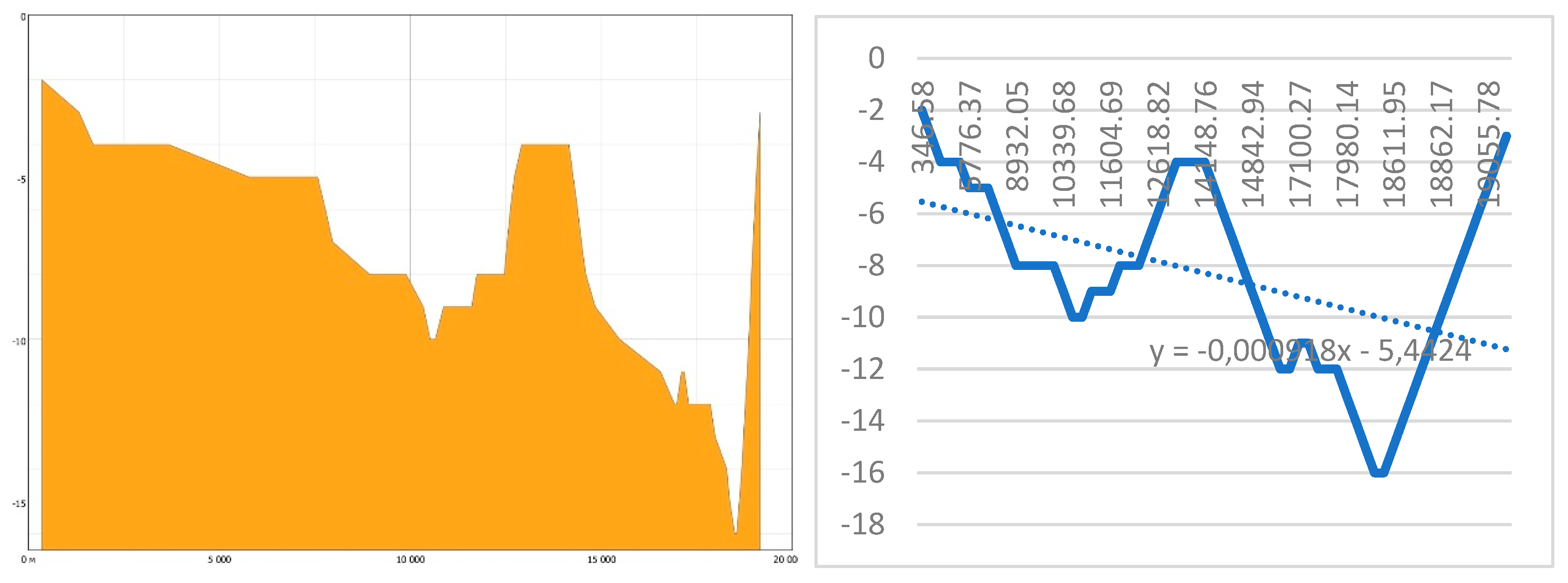

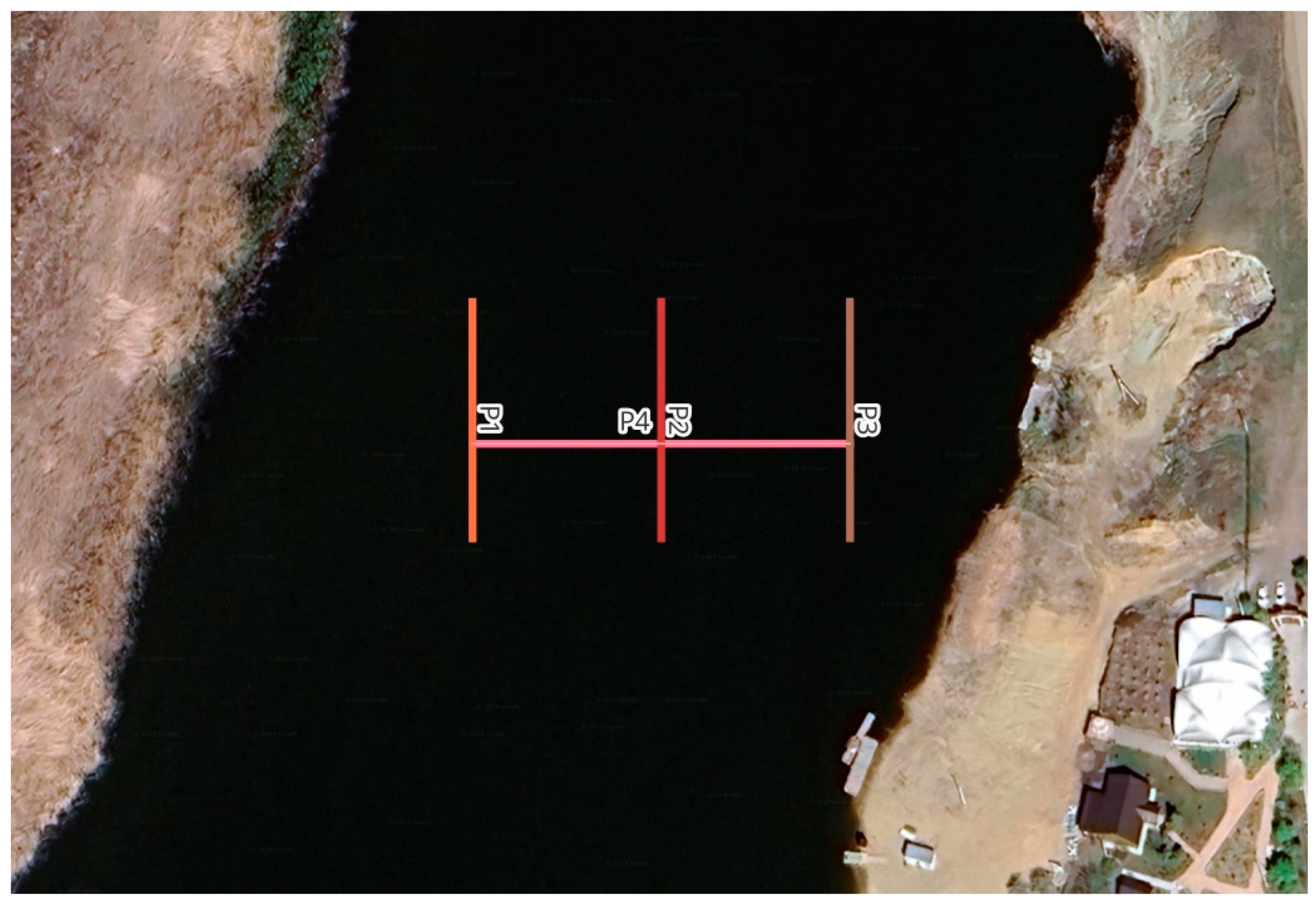

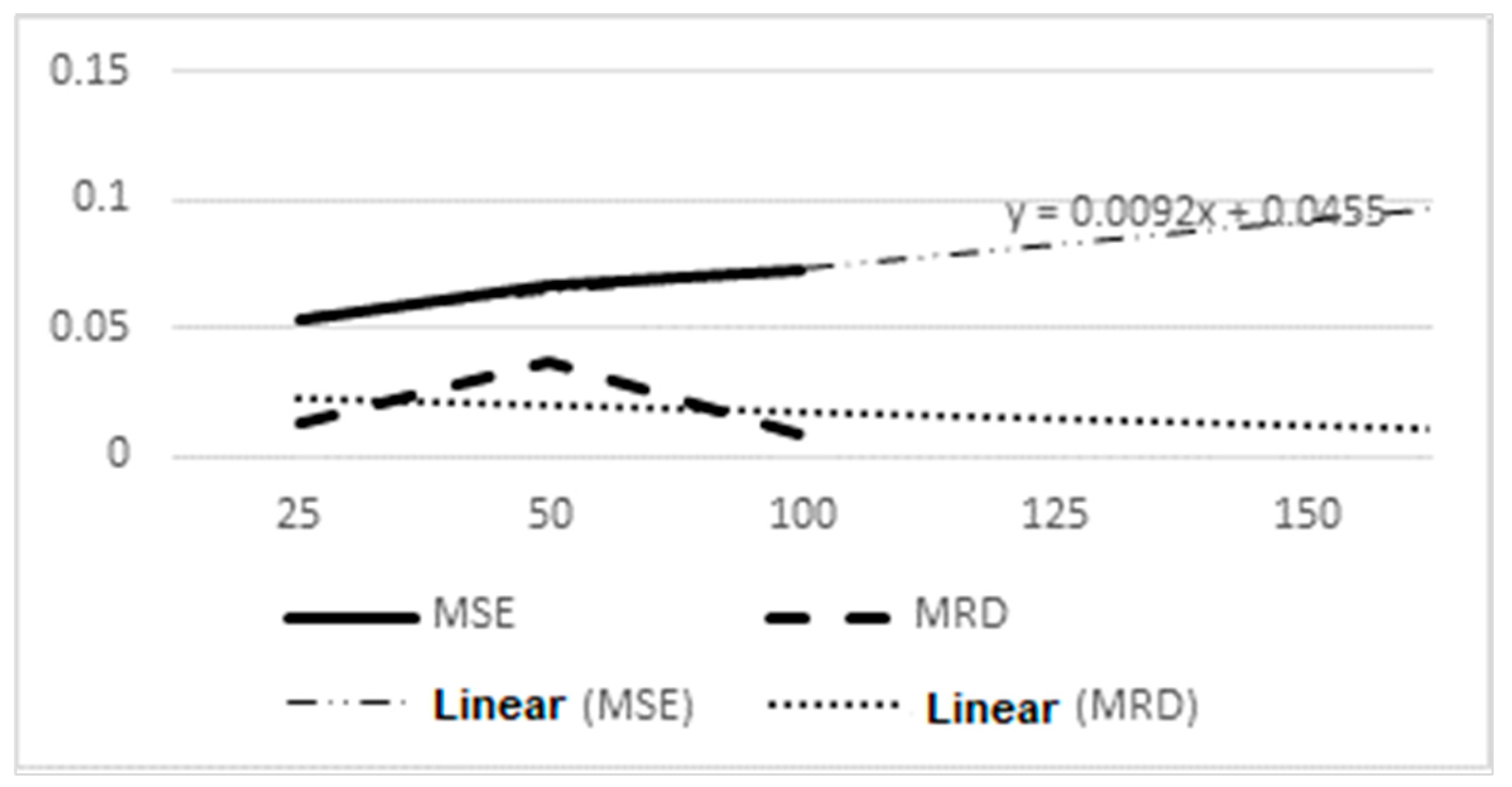

3.3. Evaluation of the Boat's Tack Pitch to Ensure the Required Measurement Accuracy

| Parameter | Depth (Minimum) | Depth (Maximum) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run step | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| Interpolation method | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.800 | 0.400 | 0.130 | 1.540 | 5.540 | 5.250 | 5.490 | 5.360 |

| Planar Regression: Z = AX+BY+C |

0,1353 | 0.009 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 3.054 | 1.073 | 1.096 | 0.707 |

| Kriging | 1.573 | 1.141 | 1.007 | 2.727 | 5.550 | 5.419 | 5.919 | 5.348 |

| Parameter | Depth (Mean) | MSE (Relative Mean Diff) | ||||||

| Run step | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| Interpolation method | ||||||||

| Linear | 4.225 | 4.216 | 4.274 | 4.301 | 0.112 | 0.106 | 0.105 | 0.161 |

| Planar Regression: Z = AX+BY+C |

2.245 | 0.313 | 0.320 | 0.288 | 0.164 | 0.359 | 0.301 | 0.342 |

| Kriging | 4.298 | 4.261 | 4.343 | 4.367 | 0.119 | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.105 |

| Section Р1 | Section Р2 | Section Р3 | ||||||||||

| Run step | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| Point | Depth | |||||||||||

| 0 | -3.82 | -3.79 | -3.80 | -3.81 | -4.18 | -4.18 | -4.18 | -4.18 | -4.51 | -4.49 | -4.52 | -4.52 |

| 10 | -3.79 | -3.78 | -3.80 | -3.81 | -4.22 | -4.22 | -4.22 | -4.19 | -4.52 | -4.52 | -4.52 | -4.51 |

| 20 | -3.55 | -3.68 | -3.79 | -3.8 | -4.27 | -4.23 | -4.23 | -4.19 | -3.33 | -4.52 | -4.58 | -4.60 |

| 30 | -3.76 | -3.69 | -3.74 | -3.83 | -4.27 | -4.24 | -4.25 | -4.24 | -4.61 | -4.55 | -4.65 | -4.71 |

| 40 | -3.87 | -3.85 | -3.72 | -3.86 | -4.27 | -4.26 | -4.26 | -4.28 | -4.57 | -4.63 | -4.69 | -4.82 |

| 50 | -3.90 | -3.89 | -3.84 | -3.89 | -4.27 | -4.30 | -4.28 | -4.29 | -4.64 | -4.71 | -4.71 | -4.92 |

| 60 | -3.94 | -3.94 | -3.87 | -3.93 | -4.29 | -4.32 | -4.31 | -4.31 | -4.73 | -4.74 | -4.80 | -4.99 |

| 70 | -4.00 | -4.01 | -4.00 | -4.00 | -4.32 | -4.32 | -4.33 | -4.33 | -4.83 | -4.81 | -4.74 | -5.03 |

| 80 | -4.03 | -4.04 | -4.02 | -4.04 | -4.33 | -4.36 | -4.34 | -4.36 | -4.98 | -4.99 | -4.67 | -5.03 |

| Parameter | Р1 | Р2 | Р3 | Р4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run step | 25 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 100 |

| MSE | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| MRD | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | 0.93 | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| Similarity coefficient | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

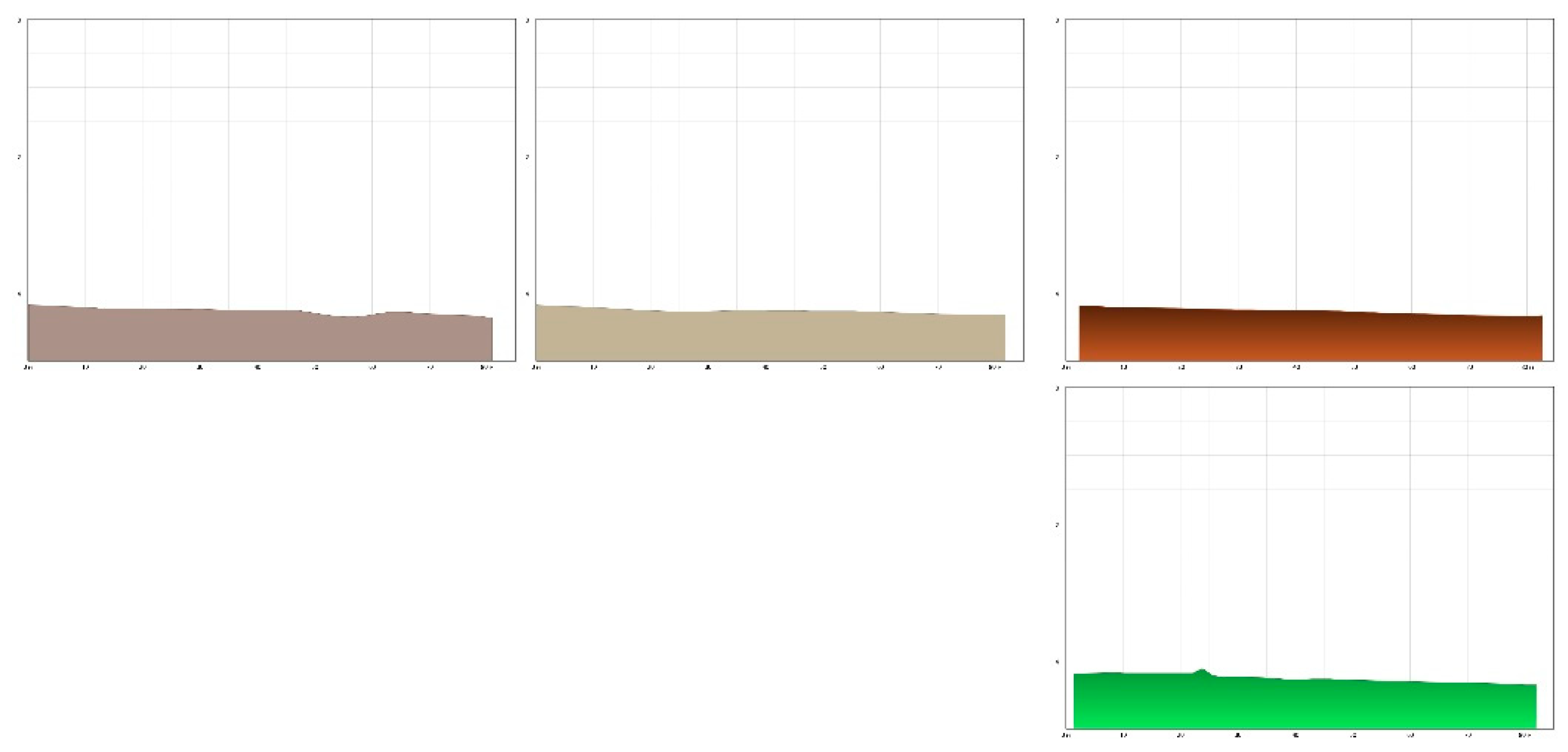

3.4. Evaluation of the Compliance of the Tobol River Bed with the Conditions Taken as the Standard "Bay"

| Depth, m | Pirson Аyat | Pirson Tobol | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance, m | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |||

| r. Ayat | P1 | -3.55 | -3.55 | -3.56 | -3.56 | -3.56 | -3.57 | -3.57 | -3.57 | -3.58 | ||

| r. Tobol | P2 | -5.44 | -5.45 | -5.45 | -5.46 | -5.46 | -5.47 | -5.47 | -5.48 | -5.48 | ||

| “Bay” | P1 | -3.82 | -3.79 | -3.55 | -3.76 | -3.87 | -3.90 | -3.94 | -4.03 | -4.00 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| P2 | -4.18 | -4.22 | -4.27 | -4.27 | -4.27 | -4.27 | -4.29 | -4.32 | -4.33 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| P3 | -4.51 | -4.52 | -3.33 | -4.61 | -4.57 | -4.64 | -4.73 | -4.83 | -4.98 | 0.54 | 0.54 | |

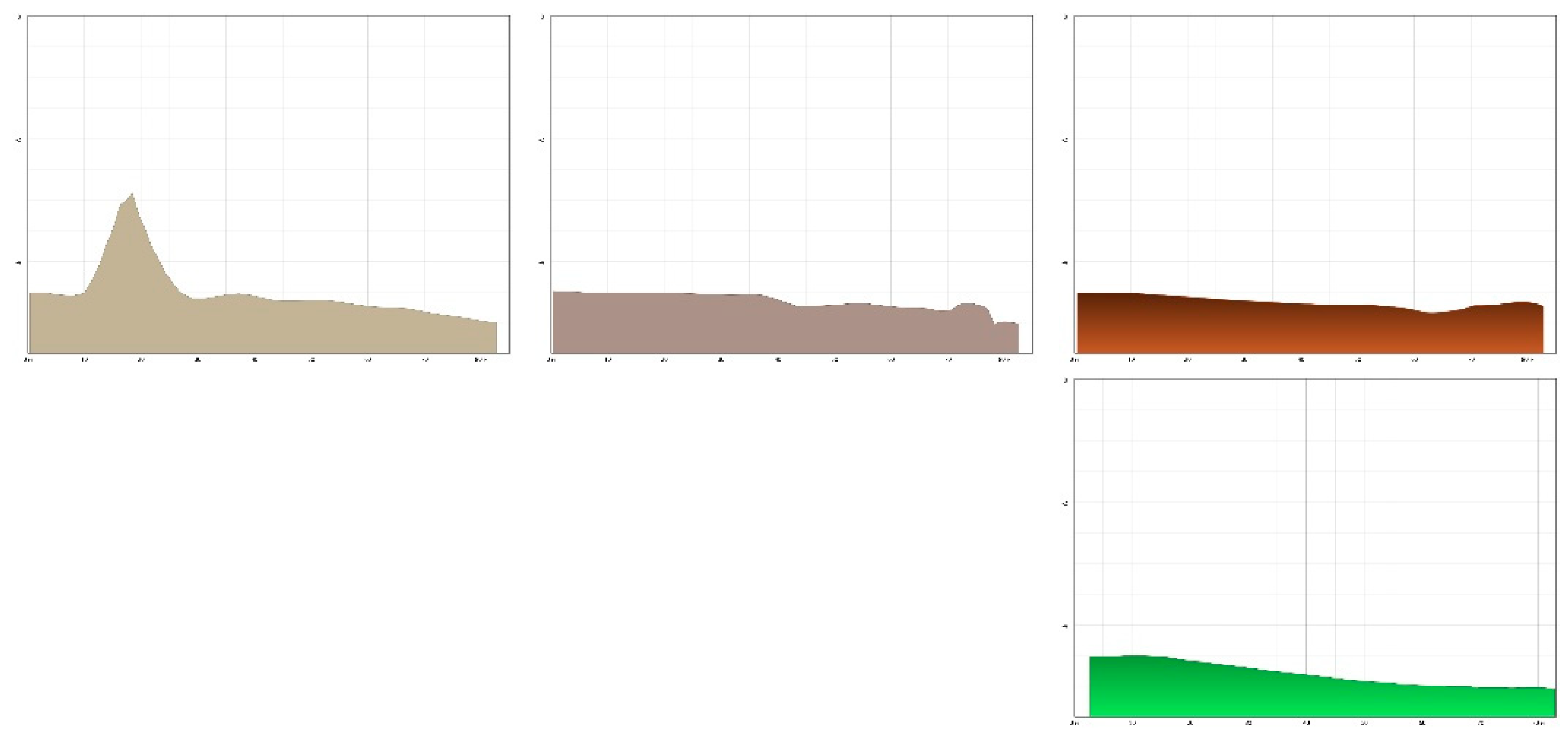

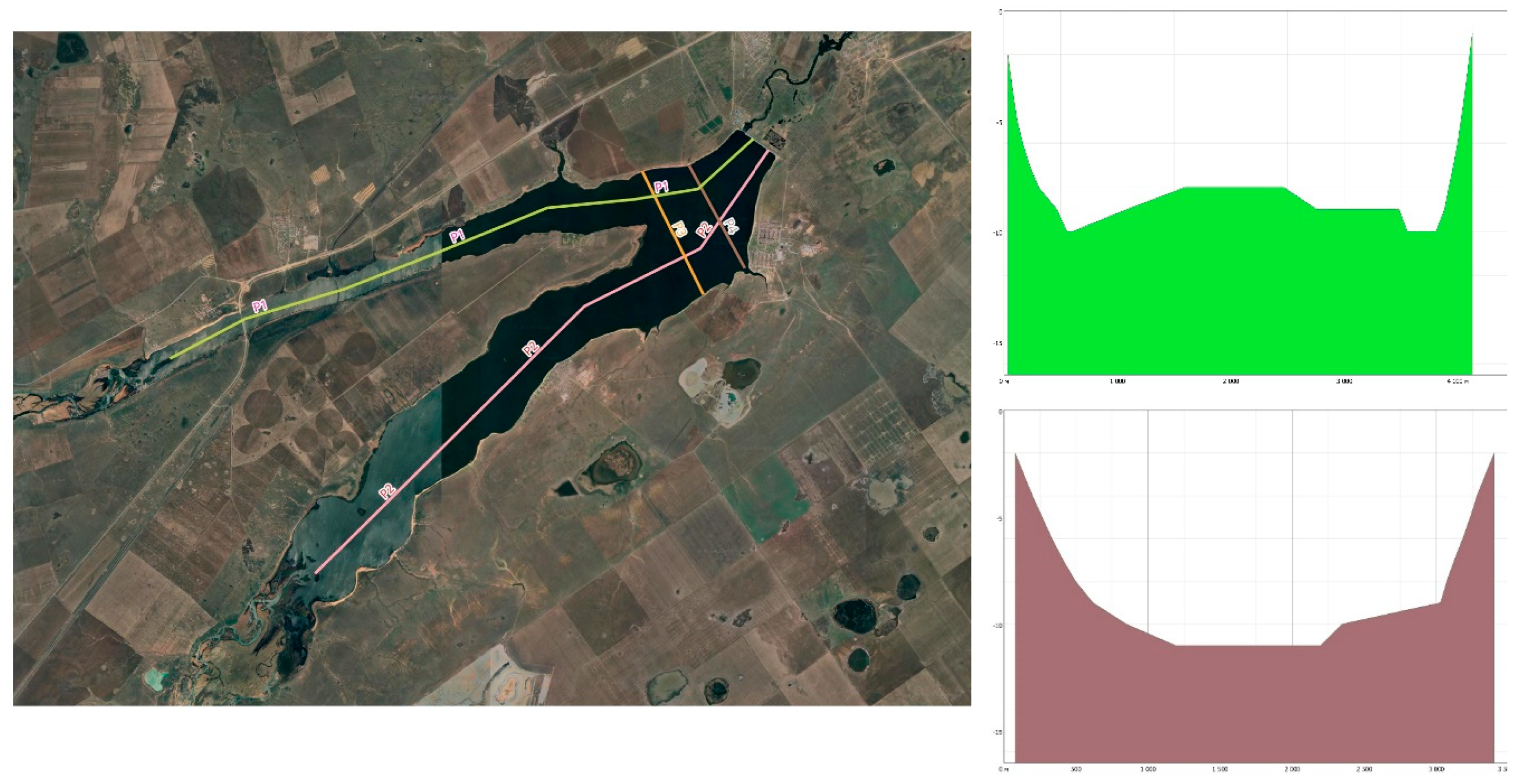

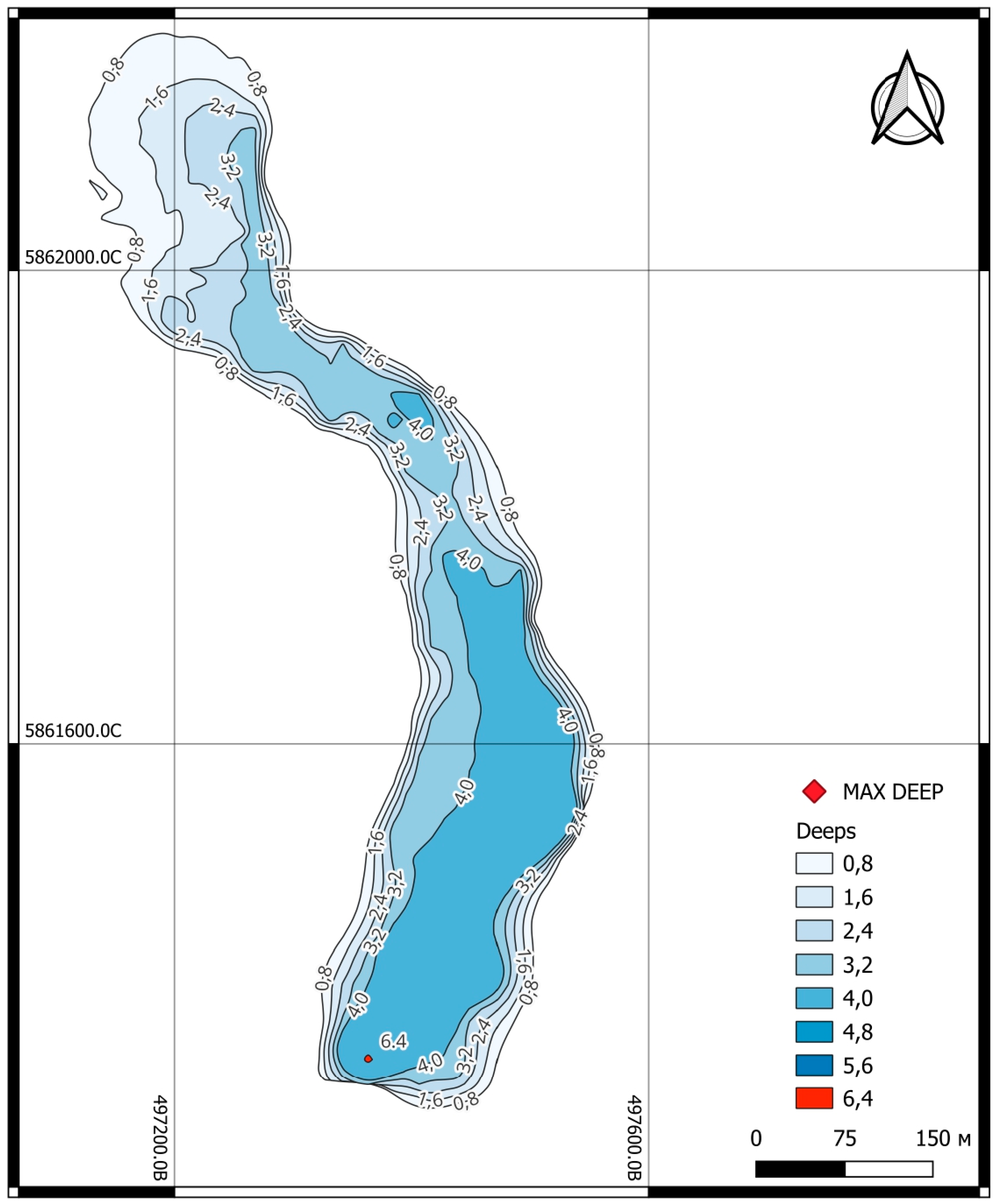

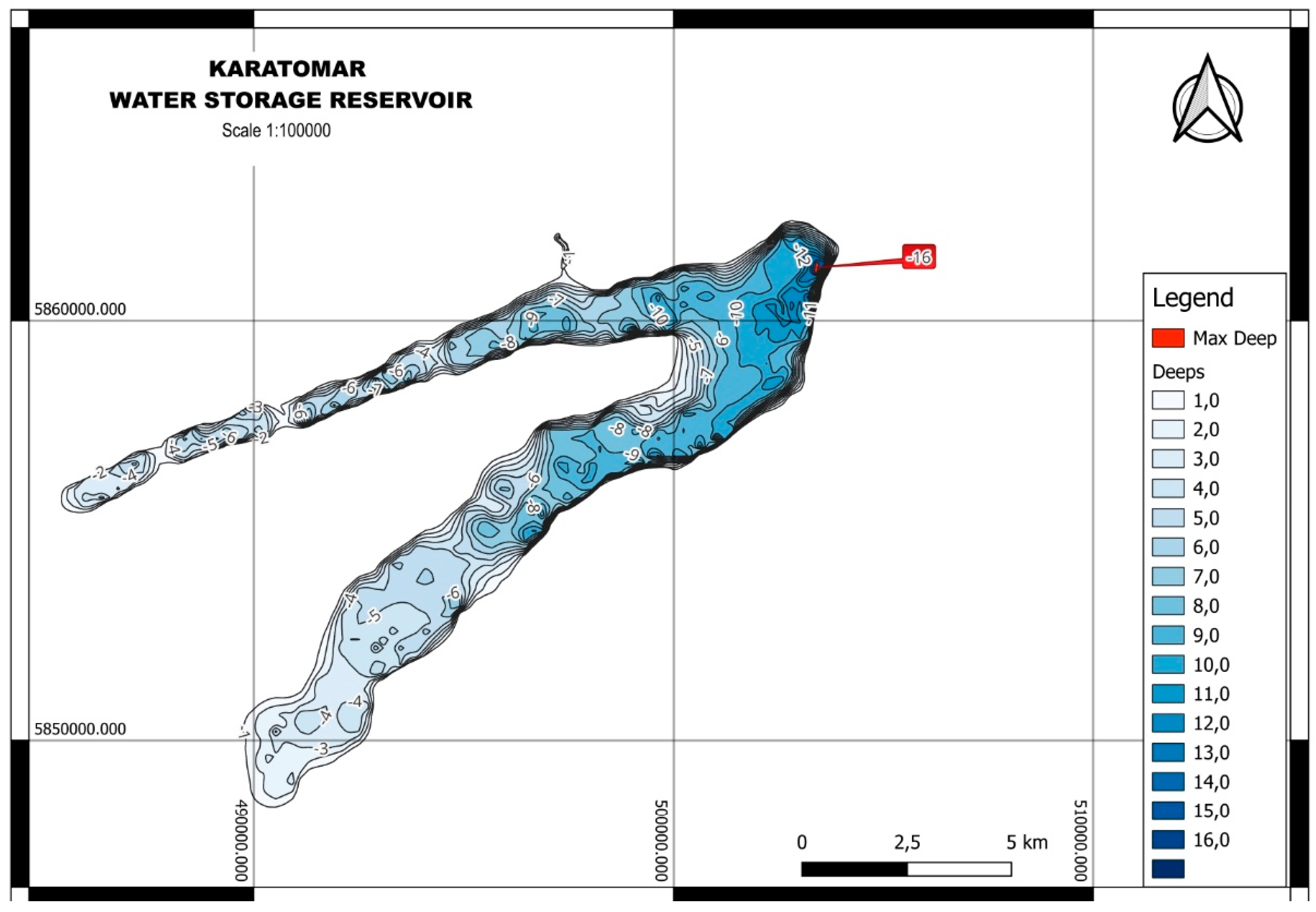

3.5. Modeling the State of the Kartomar Reservoir

| Depth, m | Mirror area by depth | Bowl volume by depth | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % of maximum | km3 | % of maximum | |

| 0 | 61.466 | 100.00 | 367.049 | 100.00 |

| 1 | 55.254 | 89.89 | 305.582 | 83.25 |

| 2 | 50.716 | 82.51 | 250.329 | 68.20 |

| 3 | 45.473 | 73.98 | 199.613 | 54.38 |

| 4 | 38.947 | 63.36 | 154.140 | 41.99 |

| 5 | 31.860 | 51.83 | 115.192 | 31.38 |

| 6 | 24.899 | 40.51 | 83.332 | 22.70 |

| 7 | 20.794 | 33.83 | 58.433 | 15.92 |

| 8 | 16.750 | 27.25 | 37.638 | 10.25 |

| 9 | 11.618 | 18.90 | 20.889 | 5.69 |

| 10 | 5.739 | 9.34 | 9.271 | 2.53 |

| 11 | 2.137 | 3.48 | 3.531 | 0.96 |

| 12 | 0.878 | 1.43 | 1.394 | 0.38 |

| 13 | 0.309 | 0.50 | 0.516 | 0.14 |

| 14 | 0.129 | 0,21 | 0.208 | 0.06 |

| 15 | 0.061 | 0.10 | 0.079 | 0.02 |

| 16 | 0.018 | 0.03 | 0.018 | 0.00 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LI | Interpolation method. Linear interpolation (midpoint method) |

| GPI | Interpolation method. Interpolation by the global polynomial method |

| LPI | Interpolation method. Interpolation by the local polynomial method |

| IDW | Interpolation method. Interpolation by the inverse distance weighted method |

| RBF | Interpolation method. Interpolation based on the application of radial basis functions |

| Kriging | Interpolation method. Ordinary, simple, universal, indicator, probabilistic, disjunctive and empirical Bayesian kriging. |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| RBFN | Radial basis function neural network |

| FNN | Back propagation neural network |

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| CapsNet | Capsule neural networks |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| MRD | Maximum relative deviation |

References

- Cooley, S. W., Ryan, J. C., Smith, L. C. Human alteration of global surface water storage variability. Nature, 2021, 591(7848), pp. 78–81. [CrossRef]

- Chao, B., Wu, Y., Li, Y. Impact of artificial reservoir water impoundment on global sea level. Science, 2008, 320(5873), pp. 212–214. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C. E., Saros, J. E., Vincent, W. F., Smol, J. P. Lakes and reservoirs as sentinels, integrators, and regulators of climate change. Limnology & Oceanography, 2009, 54 (6 part 2), pp. 2273–2282. [CrossRef]

- On approval of the Concept for the development of the water resources management system of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2024–2030, Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated February 5, 2024. No. 66. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2400000066 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Yigzaw, W., Li, H. Y., Demissie, Y., Hejazi, M. I., Leung, L. R., Voisin, N., Payn, R. A new global storage-area-depth data set for modeling reservoirs in land surface and earth system models. Water Resources Research, 2018, 54(12), pp. 386. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Gao, H., Jasinski, M. F., Zhang, S., Stoll, J. D. Deriving high-resolution reservoir bathymetry from ICESat-2 prototype photon-counting lidar and landsat imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2019, 57(10), pp. 7883–7893. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E., Morris, C., Belz, J., Chapin, E., Martin, J., Daffer, W., Hensley, S. An assessment of the SRTM topographic products, Technical Report JPL D-31639, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, 2005, 143 p.

- Zhang, K., Gann, D., Ross, M., Robertson, Q., Sarmiento, J., Santana, S., Rhome, J., Fritz, C. Accuracy assessment of ASTER, SRTM, ALOS, and TDX DEMs for Hispaniola and implications for mapping vulnerability to coastal flooding. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2019, 225, pp. 290–306. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z., Chen, F., Jia, X., Cai, X., Yang, C., Du, Y., Ling, F. GRDL: A new global reservoirarea-storage-depth data set derivedthrough deep learning-based bathymetryreconstruction. Water ResourcesResearch,, 2024, 60. [CrossRef]

- Bandini, F., Olesen, D., Jakobsen, J., Kittel, C., Wang, S., Garcia, M., Bauer-Gottwein, P. Bathymetry observations of inland water bodies using a tethered single-beam sonar controlled by an unmanned aerial vehicle. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 2018, 22(8), pp. 4165–4181. [CrossRef]

- Pirani, F., Modarres, R. Geostatistical and deterministic methods for rainfall interpolation in the Zayandeh. Hydrological sciences journal, 2020, 65(16), pp. 2678–2692. [CrossRef]

- Zarubin, M., Zarubina, V., Jamanbalin, K., Akhmetov, D., Yessenkulova, Z., Salimbayeva, R. Digital Technologies as a Factor in Reducing the Impact of Quarries on the Environment. Environmental and Climate Technologies, 2021, 25, pp. 436–454. [CrossRef]

- Dovile, K., Zenonas, N., Raimondas, Č., Minvydas, R. An extended Prony’s interpolation scheme on an equispaced grid. Open Mathematics, 2015, 13(1), pp. 000010151520150031. [CrossRef]

- Skorokhodov, I. Interpolating Points on a Non-Uniform Grid using a Mixture of Gaussians, 2020, Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2012.13257 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Gilewski, P. Impact of the Grid Resolution and Deterministic Interpolation of Precipitation on Rainfall-Runoff Modeling in a Sparsely Gauged Mountainous Catchment. Water, 2021, 13(2):230, doi:doi: 10.3390/W13020230.

- Ben-Or, M., Tiwari, P. A deterministic algorithm for sparse multivariate polynomial interpolation. In Proceedings of the twentieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing (STOC '88). Association for Computing Machinery, 1988, pp. 301–309. [CrossRef]

- Biernacik, P., Kazimierski, W., Wlodarczyk-Sielicka, M. Comparative Analysis of Selected Geostatistical Methods for Bottom Surface Modeling. Sensors, 2023, 23, 3941. [CrossRef]

- Alcaras, E., Amoroso, P.P. , Parente, C. The Influence of Interpolated Point Location and Density on 3D Bathymetric Models Generated by Kriging Methods: An Application on the Giglio Island Seabed (Italy). Geosciences (Switzerland), 2022, 12. 62. [CrossRef]

- Kazimierski, W., Wlodarczyk-Sielicka, M. Comparative Analysis of Selected Geostatistical Methods for Bottom Surface Modeling. Sensors, 2023, 23(8), pp. 3941-3941, doi:doi: 10.3390/s23083941.

- Chowdhury, M., Alouani, A.T., Hossain, F. Comparison of Ordinary Kriging and Artificial Neural Network for Spatial Mapping of Arsenic Contamination of Groundwater. Stochastic Environmental Research & Risk Assessment, 2008, 24, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Janowicz, K., Gao, S., McKenzie, G., Hu, Y., Bhaduri, B. GeoAI: spatially explicit artificial intelligence techniques for geographic knowledge discovery and beyond. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 2019, 34 (4), pp. 625-636. [CrossRef]

- Zarubin, M., Zarubina, V. Results of using neural networks for technological processes control of iron mill. Journal Energy procedia, 2016, 95, pp. 512-516, doi:DOI:10.1016/j.egypro.2016.09.077.

- Yu-Len, H., Ruey-Feng, C. MLP interpolation for digital image processing using wavelet transform. In Proceedings of the Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 06 (ICASSP '99). IEEE Computer Society, USA, 1999, pp. 3217–3220. doi:0.1109/ICASSP.1999.757526.

- Nevtipilova, V., Pastwa, J., Boori, M. S., Vozenilek, V. Testing multilayer perceptron (MLP) for spatial interpolation. Interexpo Geo-Siberia, 2014, pp. 33-51. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/testing-multilayer-perceptron-mlp-for-spatial-interpolation (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Yeh, I., Huang, K.-C., Kuo, Y.-H.. Spatial interpolation using MLP–RBFN hybrid networks. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 2013, 27, pp. 1884-1901. [CrossRef]

- Gotway, C., Ferguson, R., Hergert, G., Peterson, T. Comparison of Kriging and Inverse-Distance Methods for Mapping Soil Parameters. Soil Science Society of America Journal - SSSAJ, 1996, pp. 60. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. , Ghorbanidehno, H., Lee, J.H. , Farthing, M., Hesser, T. , Kitanidis, P.K., Darve, E.F. Applications of Deep Neural Network to Near-shore Bathymetry with Sparse Measurements. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, abstract #EP43C-04., 2019. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2019AGUFMEP43C..04Q/abstract (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Mazzia, V., Salvetti, F., Chiaberge, M. Efficient-CapsNet: capsule network with self-attention routing. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1):14634. [CrossRef]

- Nurpeisova, M.B., Zharkimbaev, B.M. Geodesy, 2002.

- Neumann, J. Maximum depth and average depth of lakes. Journal of the Fisheries Board of Canada, 1959, 16(6), pp. 923–927. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. A note on the morphology of the basins of the Great Lakes. Journal of the Fisheries Board of Canada, 1961, 18(2), pp. 273–277. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, J. T. Reconstructing the rate of accumulation of lake sediment: The effect of sediment focusing. Quaternary Research, 1975, 5(4), pp.541–550.

- Carpenter, S. R. Lake geometry: Implications for production and sediment accretion rates. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1983, 105(2), pp.273–286. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., Birkett, C., Lettenmaier, D. Global monitoring of large reservoir storage from satellite remote sensing. Water Resources Research, 2012, 48(9), W09504. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Xie, F., Ling, F., Du, Y. Monitoring surface water inundation of Poyang Lake and Dongting Lake in China using Sentinel-1 SAR images. Remote Sensing, 2022, 14(14), 3473. [CrossRef]

- Zhen Hao, Fang Chen, Xiaofeng Jia, Xiaobin Cai, Chao Yang, Yun Du, Feng Ling. GRDL: A New Global Reservoir Area-Storage-Depth Data Set Derived Through Deep Learning-Based Bathymetry Reconstruction. Water Resources Research, 2024, 1(60). [CrossRef]

- Yao, F., Minear, J.T., Rajagopalan, B., Wang, C., Yang, K., Livneh, B. Estimating reservoir sedimentation rates and storage capacity losses using high-resolution Sentinel-2 satellite and water level data. Geophysical Research Letters, 2023, 50(16). [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Song, C., Wang, J., Ke, L., Zhu, Y., Jingying, Z., Luo, Z.L., Remote sensing-based modeling of the bathymetry and water storage for channel-type reservoirs worldwide. Water Resources Research, 2020, 56(11). [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.-S., Cho, J.-M. Hydroacoustic Application of Bathymetry and Geological Survey for Efficient Reservoir Management. Journal of the Korean Society of Surveying, Geodesy, Photogrammetry and Cartography, 2011, 29. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J. D. Coastline delineation by aerial photography. Australian Surveyor, 1978, 29(2), pp.76–82. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J., Bastos, M., Pinho, J., Granja, H. (Digital aerial photography to monitor changes in coastal areas based on direct georeferencing, 5th EARSeL Workshop on Remote Sensing of the Coastal ZoneAt, Prague, Czech Republic, 2011, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360427485_DIGITAL_AERIAL_PHOTOGRAPHY_TO_MONITOR_CHANGES_IN_COASTAL_AREAS_BASED_ON_DIRECT_GEOREFERENCING (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Tyszkowski, S., Zbucki, Ł., Kaczmarek, H., Duszyński, F., Strzelecki, M. Detection of Coastal Changes along Rauk Coasts of Gotland, Baltic Sea. Remote Sens, 2023, 15, 1667. [CrossRef]

- Lubczonek, J., Kazimierski, W., Zaniewicz, G., Lacka, M. Methodology for Combining Data Acquired by Unmanned Surface and Aerial Vehicles to Create Digital Bathymetric Models in Shallow and Ultra-Shallow Waters. Remote Sens, 2022, 14, 105. [CrossRef]

- Lubczonek, J., Wlodarczyk-Sielicka, M., Lacka, M., Zaniewicz, G. Methodology for Developing a Combined Bathymetric and Topographic Surface Model Using Interpolation and Geodata Reduction Techniques. Remote Sens, 2021, 13, 4427. [CrossRef]

- Han, D. Comparison of Commonly Used Image Interpolation Methods. In Proceedings of the ICCSEE 2013, Hangzhou, China.

- Jiao, Y., Zhang, F., Huang, Q., Liu, X., Li, L. Analysis of Interpolation Methods in the Validation of Backscattering Coefficient Products. Sensors, (2023, 23, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010469.

- Weather in Rudny in July 2024. Available online: https://belkraj.by/pogoda/kazakhstan/l1519843/rudnyy/july (accessed on 01 September 2024).

- Tobol. Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia. State Water Register, 2009.

| Parameter name | Value |

|---|---|

| Echo sounder | |

| Measured depth range, m | from 0.15 to 200 |

| Echo sounder operating frequency, kHz | 200 |

| Echo sounder resolution, m | 0.01 |

| Echo sounder beam width, ° | 6.5±1 |

| Root mean square error (RMSE) of depth measurements, m | 0.01+0.001·H, where H is the measured depth in cm |

| Location | |

| Number of channels | 624 |

| GNSS | GPS NAVSTAR: L1C/A, L1C, L2C, L2P, L5 ГЛОНАСС: L1C/A, L1P, L2C/A, L2P BeiDou: B1, B2, B3 Galileo: E1, E5A, E5B SBAS: WAAS, EGNOS, MSAS, QZSS, GAGAN |

| RMSE | RTK in plan 8.0 mm + 1.0 mm/km |

| RMSE | RTK in height 15.0 mm + 1.0 mm/km |

| RMSE DGPS in plan | 0.25 m |

| RMSE DGPS in altitude | 0.5 m |

| Heading accuracy | 0.2° per 1 m baseline |

| Inertial navigation stability | 6° per hour |

| Link | Name/Brief description of the method | Required equipment | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual methods of depth measurement and topographic survey of the relief of the coastal zone of the reservoir | ||||

| - | The method is based on measuring the length of the released lead line from the side of the vessel. | Hand lot, vessel | Affordability of single measurements | Low speed and accuracy of water body depth measurements |

| [29] | Theodolite survey | Theodolite, steel measuring tape (or optical rangefinder) | Affordability of single measurements | Low measurement speed, Limited sizes of theodolite traverses (polygons), Difficulty of carrying out work on hard-to-reach riverbed slopes |

| Tacheometric survey | Tacheometer | |||

| Tablet survey | Measuring plate | Difficulty of carrying out work on riverbed slopes | ||

| Surface leveling (vertical or altitude survey) | Level | High precision | Need for additional planning and reference work of reference points | |

| Phototheodolite survey of coastline relief (terrestrial) | Phototheodolite | |||

| Methods of automated bathymetry and topographic survey of the relief of the coastal zone of the reservoir | ||||

| [39] | Hydroacoustic sounding of the underwater part of the reservoir | Echo sounder, underwater measurement vessel/drone, attitude sensors | Possibility of capturing large volumes of data with high accuracy | Impossibility of taking measurements on overgrown areas of the reservoir |

| [40,41] | Phototheodolite survey of the coastline relief (aerial photography) | Aircraft, aerial camera | Possibility of obtaining plans of large areas. | Need for additional planning and reference work of reference points Sensitivity of measurement accuracy to the density of vegetation cover. |

| [42] | Laser scanning of the coastline relief | LiDAR, optional aerial survey aircraft + attitude sensors |

Obtaining topographic plans of complex profiles. High accuracy. Measurement speed. |

Sensitivity of measurement quality when working with reflective surfaces |

| Methods of remote satellite sensing and digital modeling of water bodies | ||||

| [34,37] | Group of space radar altimetry methods | Requires satellite LiDAR data and field survey data to determine depth | Obtaining topographic plans of complex profiles. High accuracy. Measurement speed |

Dependent on cloudiness and weather conditions. Possibility of constructing only surface reliefs |

| [5,38] | A group of methods for reconstructing and forecasting bathymetry using space data and global models. | Space photography data is required | Possibility of constructing the full relief of a reservoir bowl | Often does not take into account the complex bathymetry of a water body |

| Parameters | Data 1966 | Data 2024 | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir volume, | 791 mil. m3 (when the bowl is 100% full | 367 mil. m3 (at 98% bowl filling | -53.60 % |

| Useful reservoir volume, | 562 mil. m3 | Not rated | - |

| Water surface area, | 93.7 km2 | 61.47 km2 (based on digitized polygon) ± 5.63 km2 |

-34.44 ± 6.01% |

| Maximum depth, m | 19.8 | 16.0 | -18.99 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).