Introduction

3D printing technology has transformed dentistry by allowing precise fabrication of complex dental restorations. Among the materials, 3D-printed composite resins have gained popularity due to their superior mechanical strength, aesthetic properties, and customization potential. However, the success of these materials in clinical applications depends significantly on their bond strength to underlying tooth substrates. [

1,

2] Studies have demonstrated that both the mechanical behavior and bond strength of composite resins are critical factors influencing their durability and effectiveness in dental applications. [

2,

3] The correlation between fracture toughness and bond strength further highlights the importance of optimizing these properties to ensure reliable and long-lasting clinical outcomes. [

4]

Advances in dentistry, combined with improved oral hygiene practices, have increased the demand for durable fixed prosthetic restorations, such as crowns and bridges. This trend is driven by the goal of preserving natural teeth for longer period. [

5] Advances in ceramic restorations and adhesive systems have made it possible to preserve more of the existing tooth structure while delivering superior clinical performance and aesthetic outcomes. [

6]

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, driven by computer-aided design (CAD) technology, has become a cutting-edge method in modern dentistry. It allows for the creation of precise, customized restorations, including surgical guides, splints, crowns, and bridges. [

2] The origins of 3D printing with commercial potential can be traced back to 1986 when Charles W. Hull filed a patent for stereolithography (SLA), a photopolymerization technology. [

7] The first printed model, an eye-wash cup, marked the beginning of this innovative technology's journey, which has since been further developed by 3D Systems Corporation. [

8]

Today, 3D printing technology has permeated almost all specialized branches of dentistry, offering new perspectives not only in patient treatment but also in the education and training of dental practitioners. It is widely used to produce surgical guides, occlusal splints, working models, removable partial denture frames, full dentures, temporary crowns, and bridges using polymer resin materials. [

9] The integration of ceramic into polymer resin printing materials has further enhanced the aesthetic, durability, and biocompatibility of 3D printed restorations, allowing for their use in permanent crowns, bridges, veneers, inlays, and onlays. As new resins are developed to be cost-effective and tailored to the desired characteristics, 3D printing continues to advance, providing personalized and high-quality dental solutions. [

10]

Achieving strong and durable bonds between dental restorations and tooth structures is essential for long-term clinical success. Resin-based adhesive systems are widely used to ensure reliable bonding in restorative dentistry. [

11] These adhesive systems typically consist of multiple components, including primers, bonding agents, and sometimes adhesives with filler particles for added strength. The selection of the adhesive system depends on various factors, including the material of the crown (e.g., porcelain, ceramic, composite) and the type of tooth preparation. [

12] Correctly applied adhesive cements have higher bond strength and lower solubility compared to non-adhesive cements. However, maintaining scrupulous isolation is crucial for the success of restorations using adhesive cements. [

13]

Surface treatment is a crucial factor in improving bond strength between dental substrates and restorative materials. Techniques such as sandblasting and hydrofluoric acid etching modify the surface to promote micromechanical retention and chemical bonding. Techniques such as sandblasting, acid etching, and the application of bonding agents can modify the surface characteristics of dental materials, promoting micromechanical retention and chemical adhesion. [

14,

15] The effectiveness of these surface treatments may vary depending on the composition and properties of the substrate material. [

15] Pretreatment of the ceramic interface improves the adhesion of cement and restoration. [

15] This is achieved through techniques such as air abrasion, sandblasting with aluminum oxide particles, or the application of etchant. Studies have shown that among these techniques, acid etching yields the highest bond strength, regardless of the ceramic composition. Etching creates microporosities that increase the surface area of the interface, enhancing the wettability of the cement and aiding in micromechanical interlocking at the ceramic interface. [

15,

16]

Despite the advancements in adhesive technology, achieving reliable bonding between 3D-printed composite resins and tooth structures remains challenging. The limited research on surface treatments for 3D-printed composites creates a gap in understanding how these treatments affect shear bond strength. The success of this bond depends on various factors, including proper surface preparation, the selection of suitable cement, and precise curing techniques. While advanced adhesive systems and meticulous clinical protocols are crucial in overcoming these obstacles, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding the effect of surface treatments on the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composites. [

15,

17]

This study aims to evaluate the effects of various surface treatments—no treatment, sandblasting, hydrofluoric acid etching, and a combination of both—on the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs bonded with Panavia V5 cement. This research seeks to address the gap in understanding how surface treatments influence bond strength in emerging 3D-printed composite materials.

Hypothesis: It is hypothesized that surface treatments, including sandblasting and hydrofluoric acid etching, will significantly enhance the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs compared to untreated surfaces.

Materials and Method

This study adhered to the CRIS (Checklist for Reporting In-Vitro Studies) guidelines. [

18]

Materials: The study utilized RODIN SCULPTURE 2 composite resin (Shade A3, Lot # 312065) for 3D printing applications and Vita Mark II blocks (Lot # 91260) for ceramic restoration. Panavia V5 resin cement (Lot # 000149) was used for bonding, while 9.6% hydrofluoric acid etching (PULPDENT Porcelain Etch Gel, Lot # 161115) was applied to the 3D-printed composite resin surfaces (

Table 1).

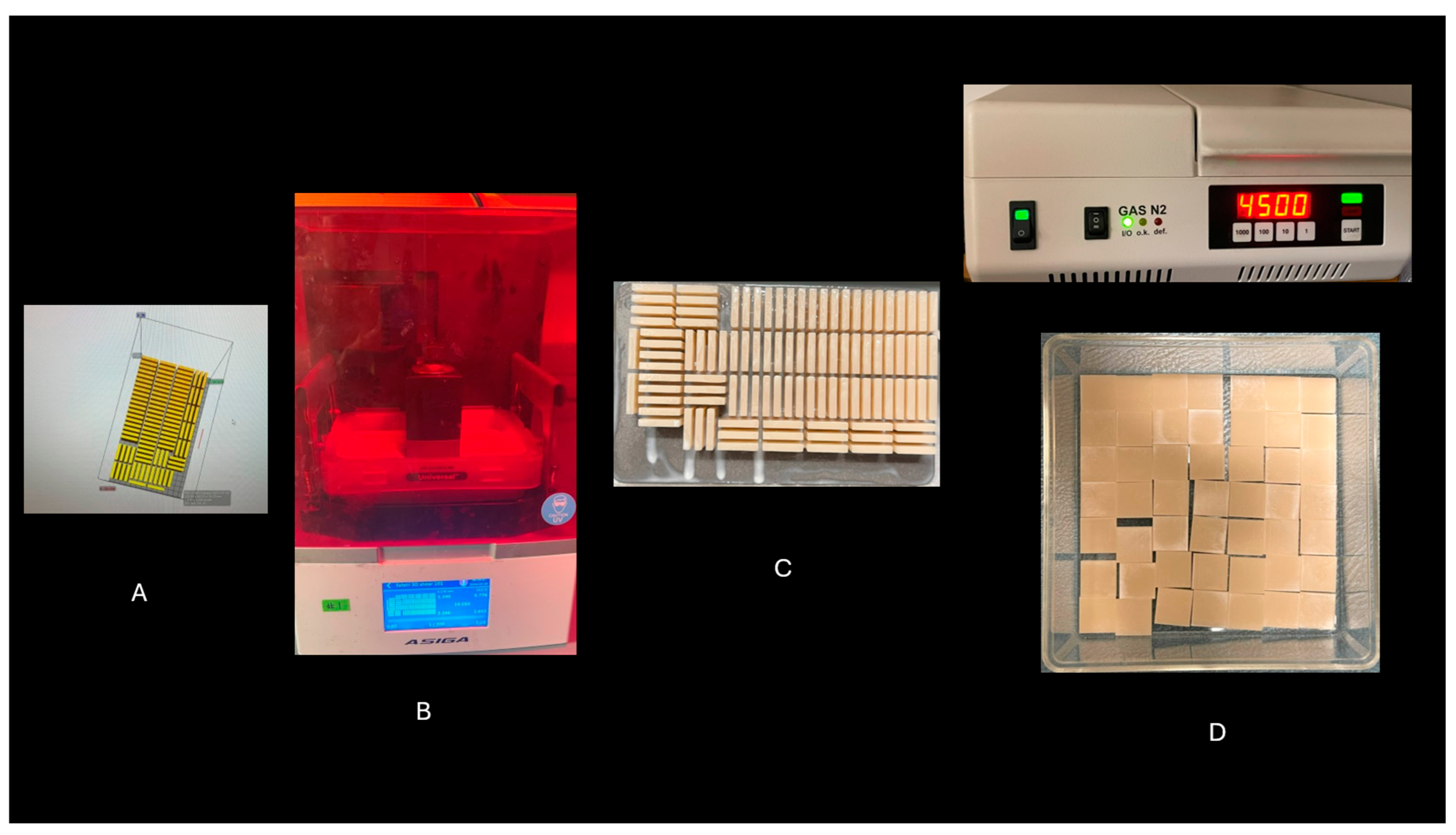

A total of 48 discs, each with dimensions of 2 mm thickness × 14 mm length × 14 mm width, were fabricated using ASIGA design software (

Figure 1A) and printed using the ASIGA MAX UV 3D Printer (ASIGA, Sydney, Australia) (

Figure 1B). The composite resin used was RODIN SCULPTURE 2 (Shade A3, Lot # 312065), recognized for its superior aesthetic qualities and mechanical strength. After the printing process, each disc underwent a thorough cleaning procedure using isopropanol to remove any residual uncured resin that could interfere with the bonding process or affect the mechanical properties (

Figure 1C). This cleaning step was essential to ensure a clean bonding surface for subsequent cementation. To ensure optimal polymerization and enhance the mechanical properties of the printed discs, a final curing process was performed in a nitrogen gas environment using a Gas N2 4500 curing unit (

Figure 1D). This nitrogen environment prevented oxygen inhibition, ensuring complete polymerization and resulting in discs with improved durability and mechanical properties for experimental analysis.

The specimens were divided into four groups (n = 12 per group) based on the surface treatment applied. In the control group, no surface treatment was applied to the 3D-printed composite resin discs. For the sandblasting group, the discs were sandblasted with 50 µm aluminum oxide particles at a pressure of 2.5 bar from a distance of 10 mm. In the hydrofluoric acid etching group, the discs were treated with 9.6% hydrofluoric acid etching gel (PULPDENT Porcelain Etch Gel, Lot # 161115) for 60 seconds, followed by rinsing with water for 30 seconds and air-drying for 20 seconds. In the combination treatment group, the discs underwent sandblasting followed by hydrofluoric acid etching as described. [

19]

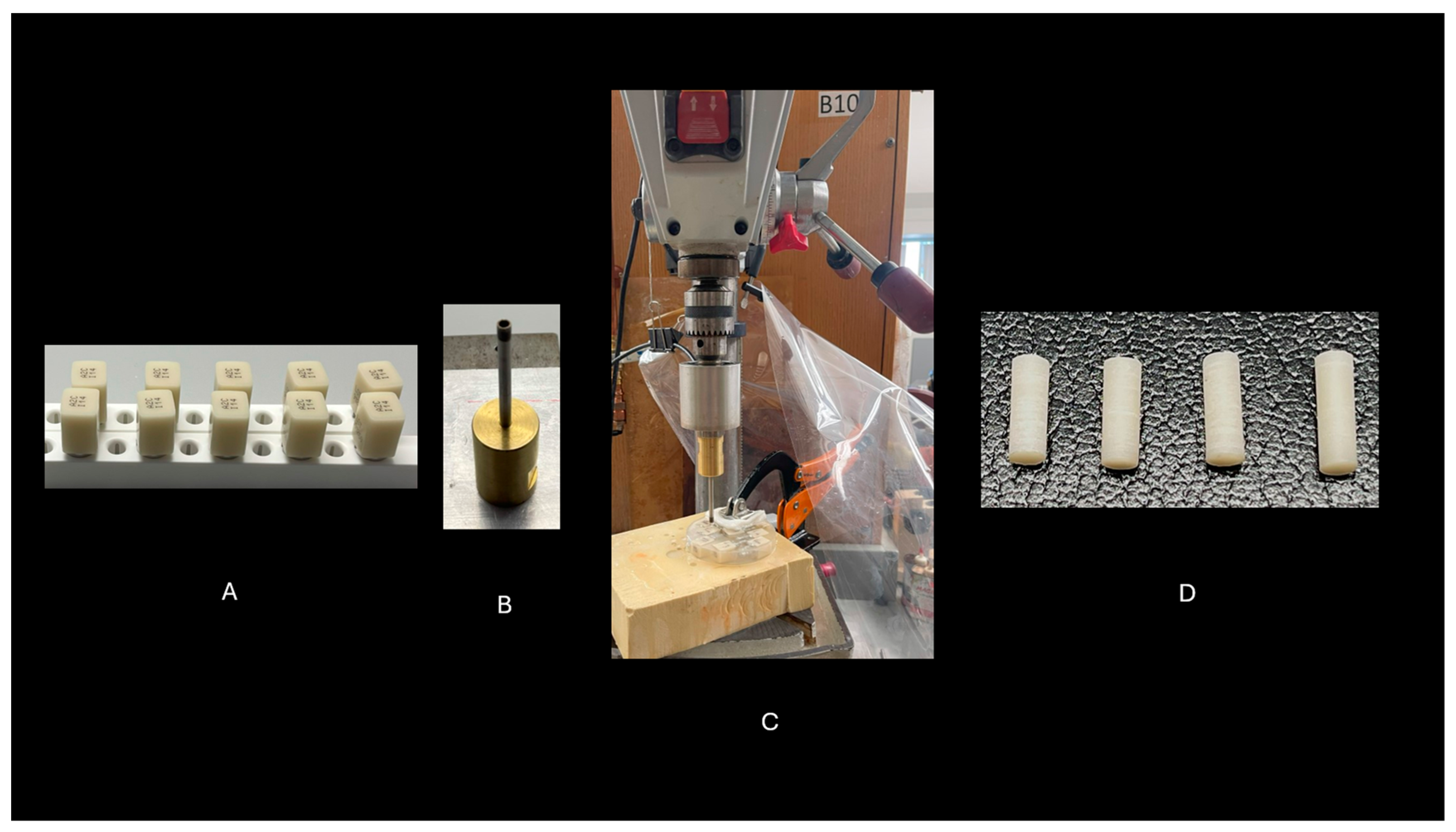

The Vita Mark II blocks (Lot # 91260) (

Figure 2A) were embedded in Buehler Epoxi Cure 2 Resin and securely mounted onto a drill press for stability during the drilling process. A 3.5 mm diamond-coated drill bit was chosen for its precision and durability in cutting through the ceramic material (

Figure 2B). Drilling was performed at a controlled speed to prevent overheating, which could lead to cracks or other damage to the ceramic. A continuous flow of water coolant was used throughout the process to maintain the integrity of both the ceramic blocks and the drill bit (

Figure 2C). Once drilling was complete, 48 rods were carefully extracted from the blocks and smoothed with fine-grit sandpaper to remove any rough edges or imperfections. The rods were then polished to ensure a consistent, uniform surface, which is essential for achieving optimal bonding in subsequent procedures (

Figure 2D). This preparation ensured that the ceramic rods were of high quality and ready for the bonding tests that followed.

Vita Mark II ceramic rods were bonded to the treated surfaces of the 3D-printed composite resin discs using Panavia V5 resin cement (Lot # 000149). Before cementation, a ceramic primer (Clearfil Ceramic Primer Plus, Kuraray Noritake) was applied to both the Vita Mark II ceramic rods and the composite resin discs, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The bonding process was standardized by applying a load of 10 N for 5 minutes to ensure uniform cement thickness. After the load was applied, the specimens were light-cured for 20 seconds on each side using an LED curing unit with a light intensity of 1200 mW/cm² to achieve proper polymerization. [

19]

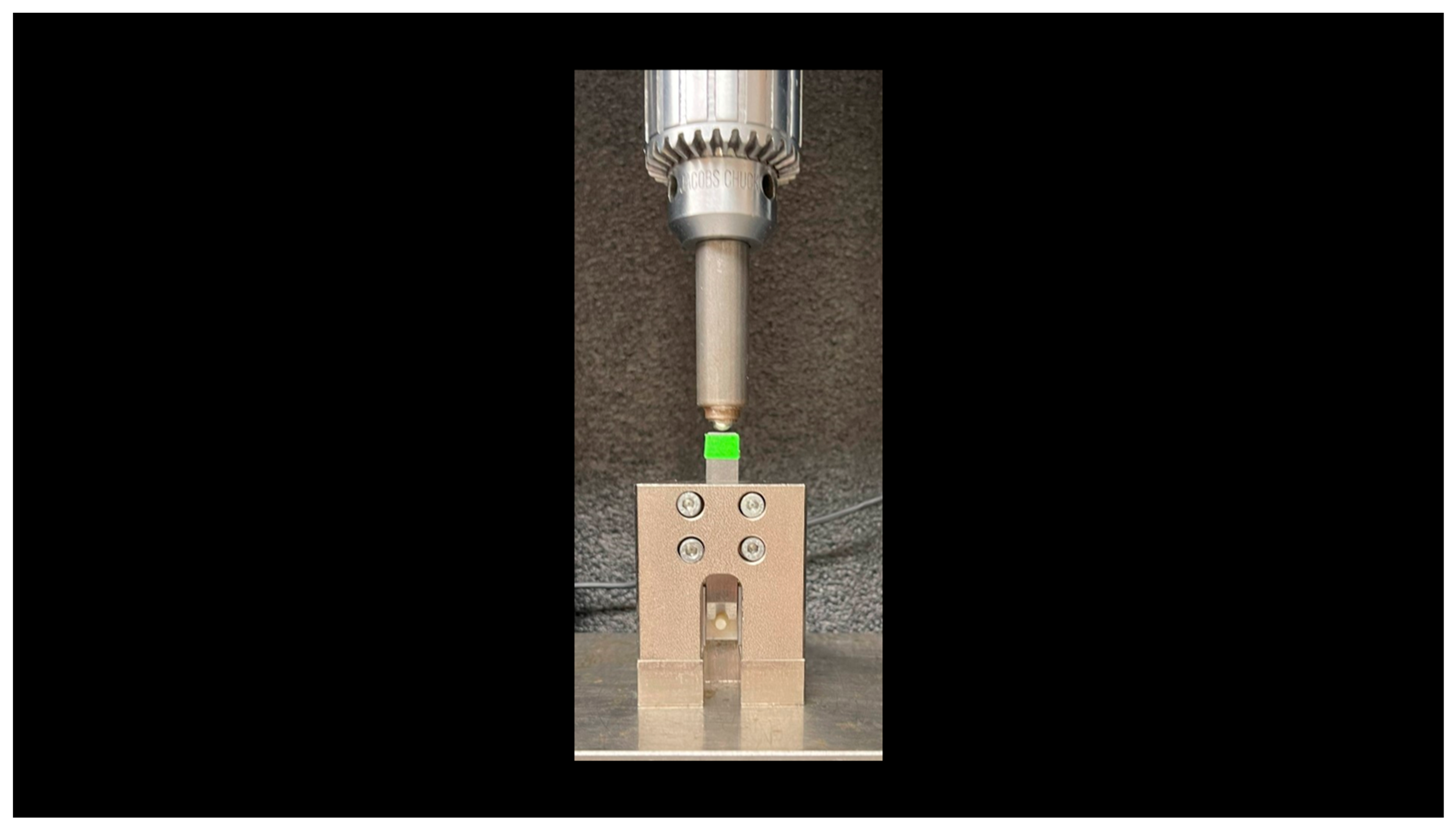

Shear bond strength was assessed for all groups, each consisting of 10 specimens, using a half-round blade with a 4 mm diameter and 2 mm edge thickness, centrally positioned on each specimen for consistent testing (

Figure 3). Testing was conducted using an Instron universal testing machine (Model 5566A) with a 1-kN load cell at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min. The blade was aligned perpendicular to the interface between the Vita Mark II rods and the 3D-printed composite materials. Load was applied parallel to the bonded interface. Shear bond strength (MPa) was calculated using the formula: Shear bond strength = F / πr², where F is the load at failure (in newtons) and r is the radius of the bonded area (in millimeters). [

20]

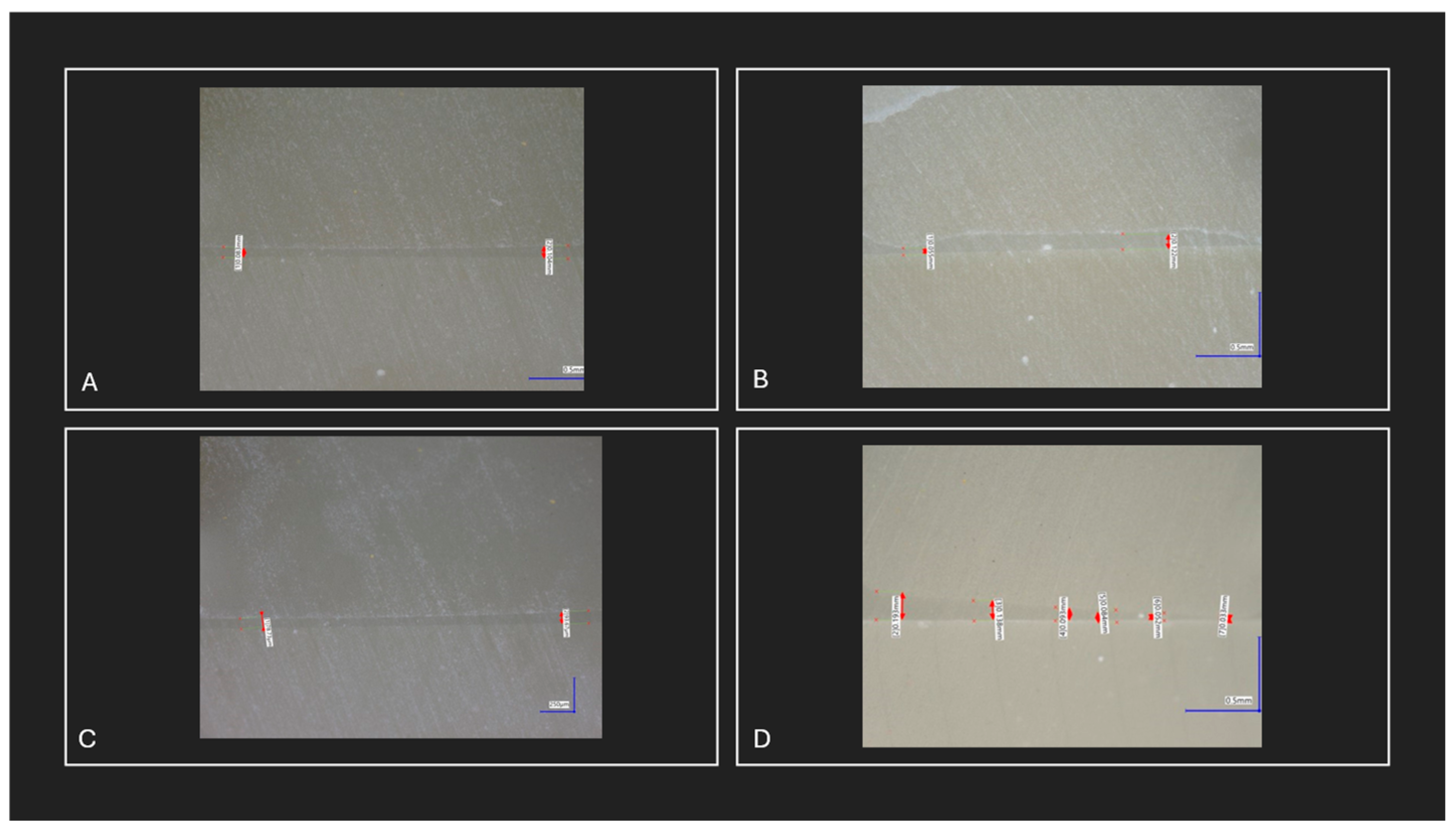

Two specimens from each group, including the Vita Mark II rods, were examined for bonding integrity and cement layer thickness using a digital optical microscope. This analysis assessed variations in bonding performance and cement layer uniformity across the different surface treatments.

Differences in shear bond strength across the four surface treatment groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). This method was selected to evaluate the main effects of the different surface treatments and to identify any statistically significant variations in bond strength. When ANOVA indicated significant differences, post-hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) tests were conducted to determine specific pairwise differences between the surface treatments. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software.

Ethical Standards Statement:

This study did not involve human participants or animal subjects. All procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for in-vitro research and adhered to the highest standards of research integrity.

Results

The shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs was evaluated under four different surface treatments: no treatment (control), sandblasting, hydrofluoric acid etching, and a combination of sandblasting and hydrofluoric acid etching. Significant differences in bond strength were observed across the treatments

In the no treatment group (control), the mean shear bond strength was 24.35 ± 6.77 MPa (range: 15.54–33.77 MPa). The sandblasting group showed a slightly lower mean bond strength of 19.07 ± 8.14 MPa (range: 8.56–31.55 MPa), The hydrofluoric acid etching group exhibited a significant increase in bond strength, with a mean of 37.79 ± 9.25 MPa (range: 28.01–54.87 MPa). The combination treatment group yielded the highest bond strength, with a mean of 40.73 ± 11.53 MPa (range: 28.29–55.21 MPa). The overall mean shear bond strength across all groups was 30.48 ± 12.64 MPa (

Table 2)

A one-way ANOVA showed significant differences in shear bond strength among the surface treatment groups (F = 13.159, p < 0.001) (

Table 3). Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests indicated no significant difference between the no treatment and sandblasting groups (mean difference = 5.28 MPa, p = 0.570), suggesting that sandblasting alone did not improve bond strength. However, hydrofluoric acid etching significantly increased bond strength compared to both no treatment (mean difference = -13.44 MPa, p = 0.011) and sandblasting (mean difference = -18.72 MPa, p < 0.001). The combination treatment also resulted in a significant increase compared to no treatment (mean difference = -16.38 MPa, p = 0.002) and sandblasting alone (mean difference = -21.66 MPa, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between hydrofluoric acid etching and the combination treatment (mean difference = -2.95 MPa, p = 0.887) (

Table 4).

Microscopic examination revealed no observable differences in bonding characteristics among the 3D-printed composites, Vita Mark II rods, and Panavia V5 cement across all surface treatment groups. Bonding performance appeared consistent. However, minor variations in cement layer thickness were noted within individual specimens and among groups. These variations were not associated with any specific surface treatment but were likely due to factors such as inconsistencies in sample preparation, differences in pressure application during bonding, or irregularities in the surfaces of the Vita Mark II rods, which were not entirely flat (

Figure 4).

Discussion

Strong adhesion between restorative materials and tooth structures is crucial for the long-term success of dental restorations. This study emphasizes the pivotal role of surface treatments in enhancing adhesion, particularly in 3D-printed composite resins, a rapidly evolving material in dental technology. Our findings provide clear evidence that hydrofluoric acid etching, either alone or in combination with sandblasting, significantly improves the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs. These results highlight the critical importance of chemical surface treatments in optimizing the bond strength of emerging 3D-printed dental materials. In this discussion, we will review the results and analyze the influence of each surface treatment on bond strength.

The results of this study demonstrated that surface treatments significantly impacted the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs. Hydrofluoric acid etching, both alone and in combination with sandblasting, resulted in notably higher bond strengths compared to no surface treatment and sandblasting alone. The improved bond strength associated with hydrofluoric acid etching can be attributed to its ability to create a micro-retentive surface, enhancing the adhesion of resin cement to the composite material by increasing surface roughness and facilitating mechanical interlocking. The results of this study demonstrated that surface treatments significantly impacted the shear bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs. Hydrofluoric acid etching, both alone and in combination with sandblasting, resulted in notably higher bond strengths compared to no surface treatment and sandblasting alone. The improved bond strength associated with hydrofluoric acid etching can be attributed to its ability to create a micro-retentive surface, enhancing the adhesion of resin cement to the composite material by increasing surface roughness and facilitating mechanical interlocking. [

21]

The lack of a notable improvement in bond strength with sandblasting alone for 3D-printed composite resin indicates that while mechanical roughening increases surface texture, it is insufficient to significantly enhance adhesion without the addition of chemical treatments such as hydrofluoric acid etching. Sandblasting provides physical roughness but does not chemically alter the surface of the 3D-printed composite resin, limiting its ability to achieve optimal bonding. [

22] This limitation is reflected in the lower, though not statistically significant, bond strengths observed in sandblasted specimens compared to untreated ones. In contrast, hydrofluoric acid etching not only roughens the surface but also chemically modifies it, leading to superior bond strength. This chemical alteration enhances surface energy and creates a stronger interface for bonding. [

23] While there are no specific studies directly confirming this effect for 3D-printed composite resins, research on ceramics supports the idea that hydrofluoric acid etching provides superior bond strength, particularly for silica-based ceramics. In ceramics, sandblasting increases surface roughness and mechanical retention, but hydrofluoric acid etching chemically modifies the surface, leading to enhanced bonding. These findings suggest that similar principles may apply to 3D-printed composite resins, where chemical surface treatments, such as hydrofluoric acid etching, could play a crucial role in significantly improving bond strength beyond what mechanical roughening alone can achieve. This underscores the importance of integrating chemical modifications into surface treatment protocols to optimize the adhesive properties of 3D-printed materials. [

23,

24,

25]

Sandblasting alone causes a minor, non-significant reduction in bond strength due to the lack of chemical alteration, despite increased surface roughness. However, applying hydrofluoric acid etching after sandblasting significantly improves bond strength by chemically modifying the surface, enhancing micromechanical interlocking and chemical bonding. [

24] While the combination of sandblasting and etching provides superior adhesion compared to untreated surfaces or sandblasting alone, the primary contributor to increased bond strength is the chemical modification from hydrofluoric acid etching. The addition of sandblasting does not significantly enhance the bond strength beyond what is achieved through etching alone.

The variation in cement thickness observed during the interface analysis provides a clear explanation for the wide range of shear bond strength values and large standard deviations noted in this study. Thicker cement layers can lead to void formation and uneven stress distribution, which weakens the overall bond strength. On the other hand, thinner cement layers allow for a more even distribution of stress, resulting in enhanced bonding efficiency. This is consistent with findings from other studies, which suggest that thinner cement layers, typically between 50-150 µm, produce higher bond strengths. [

26,

27] Additionally, the irregularity of the bonding surface of the Mark II rods may also contribute to the wide range of shear bond strength values and large standard deviations. Surface unevenness could cause inconsistent cement flow and distribution during the bonding process, further exacerbating the variability in bond strength. The irregular bonding surfaces might lead to variations in how the cement fills and adheres, making it difficult to maintain a uniform bond across all specimens. [

28] These factors variation in cement thickness and the irregularity of the Mark II rod surfaces highlight the importance of maintaining control over both cement application and the preparation of bonding surfaces. Ensuring consistent cement thickness and addressing surface irregularities are crucial to achieving reliable bond strength, especially in applications involving advanced materials like 3D-printed composites. By standardizing these aspects, the wide range of bond strength values and large deviations can be minimized, leading to more predictable and robust bonding outcomes. [

28]

In summary, this study demonstrates the critical impact of surface treatments on the bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs. Hydrofluoric acid etching was found to be the most effective treatment in enhancing bonding characteristics, while the addition of sandblasting did not provide significant additional benefits. Variations in cement thickness and the irregular bonding surface of the Mark II rods contributed to the wide range of bond strength values. Clinically, these results demonstrate that hydrofluoric acid etching should be prioritized when optimizing surface treatment protocols for 3D-printed composite resins. Ensuring consistent cement application further enhances adhesion and long-term durability, providing valuable insights for improving dental restorations. Future research should explore the long-term clinical performance of 3D-printed composite resins.

Study Strengths and Considerations

The use of a standardized Mark II ceramic substrate in this study provided a controlled and reproducible testing environment, ensuring consistency in material properties and minimizing variability inherent to natural tooth structures. This approach allows for a more precise evaluation of the effects of different surface treatments and bonding protocols. While natural tooth substrates present clinical relevance, they introduce significant variability due to differences in composition, age, and preparation methods, which could affect the reliability and comparability of the results. Furthermore, the focus on specific surface treatments enables a systematic investigation of their impact on bonding performance without confounding factors such as variations in 3D printing processes or resin cement handling techniques. The findings from this study provide a foundational understanding that can guide future research incorporating natural substrates and broader experimental conditions to further optimize bonding strategies.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the crucial role of surface treatments in improving the bond strength of 3D-printed composite resin discs. Hydrofluoric acid etching demonstrated a significant enhancement in bonding performance, while the addition of sandblasting did not provide any substantial advantage. These findings suggest that chemical surface modification is more effective than mechanical roughening alone in optimizing adhesion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest related to this study. No financial or personal relationships exist that could have inappropriately influenced the results or interpretation of the study.

References

- Dawood, A.; Marti Marti, B.; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. 3D printing in dentistry. Br Dent J. 2015, 219, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D.; Güth, J.F. 3D Printing in Digital Prosthetic Dentistry: An Overview of Recent Developments in Additive Manufacturing. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferracane, J.L. Resin composite--state of the art. Dent Mater. 2011, 27, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, P.C.; Schultheis, S.; Bonfante, E.A.; Coelho, P.G.; Ferencz, J.L.; Silva, N.R.F.A. All-ceramic systems: laboratory and clinical performance. Dent Clin N. Am. 2011, 55, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaqawi, A.H.; Aljanakh, M.D.; Alshammari, B.N.; Alshammari, M.A.; Alshammari, R.H.; Alshammari, G.D.; et al. Quality of Fixed Dental Prostheses and Patient Satisfaction in a Sample From Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023, 15, e51063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Sheikh, Z.; Misbahuddin, S.; Kazmi, M.R.; Qureshi, S.; Uddin, M.Z. Advancements in all-ceramics for dental restorations and their effect on the wear of opposing dentition. Eur J Dent. 2016, 10, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahi̇N, M.E. Example of using 3d printers in hospital biomedical units. Int. J. 3d Print. Technol. Digit. Ind. 2022, 6, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagac, M.; Hajnys, J.; Ma, Q.P.; Jancar, L.; Jansa, J.; Stefek, P.; et al. A Review of Vat Photopolymerization Technology: Materials, Applications, Challenges, and Future Trends of 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Radomski, K.; Lopez, D.; Liu, J.T.; Lee, J.D.; Lee, S.J. Materials and Applications of 3D Printing Technology in Dentistry: An Overview. Dentistry Journal 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Shenoy, M.; Alhasmi, A.; Al Saleh, A.A.; CSG; Shivakumar, S. Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Dental Resins: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024, 16, e51721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.M.; Manso, A.P.; Geraldeli, S.; Tay, F.R.; Pashley, D.H. Durability of bonds and clinical success of adhesive restorations. Dental Materials 2012, 28, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEMENT SELECTION IN DENTAL PRACTICE. WS 2019. Available online: https://rsglobal.pl/index.php/ws/article/view/106.

- Vargas, M.A.; Bergeron, C.; Diaz-Arnold, A. Cementing all-ceramic restorations. J. Am. Dent. Association 2011, 142, 20S–24S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.M.; Vieira, L.C.C.; Araújo, É.; Monteiro Júnior, S. Effect of Different Ceramic Surface Treatments on Resin Microtensile Bond Strength. J. Prosthodont. 2004, 13, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, K.; Pahinis, K.; Saltidou, K.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Tsitrou, E. Evaluation of the Surface Characteristics of Dental CAD/CAM Materials after Different Surface Treatments. Materials 2020, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köroğlu, A.; Sahin, O.; Dede, D.Ö.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of different surface treatment methods on the surface roughness and color stability of interim prosthodontic materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zicari, F.; De Munck, J.; Scotti, R.; Naert, I.; Van Meerbeek, B. Factors affecting the cement–post interface. Dental Materials 2012, 28, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Gopikrishna, V.; Datta, M. CRIS Guidelines (Checklist for Reporting In-vitro Studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting in-vitro studies in experimental dental research. J Conserv Dent. 2014, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Park, C.; Jo, D.; Yu, B.; Khalifah, S.A.; et al. Evaluation of Shear Bond Strengths of 3D Printed Materials for Permanent Restorations with Different Surface Treatments. Polymers 2024, 16, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, M.; Giordano, R.; Pober, R. Effect of time period on biaxial strength for different Y-TZP veneering porcelains. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020, 32, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzic, C.; Jivanescu, A.; Negru, R.M.; Hulka, I.; Rominu, M. The Influence of Hydrofluoric Acid Temperature and Application Technique on Ceramic Surface Texture and Shear Bond Strength of an Adhesive Cement. Materials 2023, 16, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.S. Effect of surface treatment on shear bond strength of relining material and 3D-printed denture base. J Adv Prosthodont. 2022, 14, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnaiah, R.; Alkheraif, A.A.; Divakar, D.D.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Vallittu, P.K. The Effect of Hydrofluoric Acid Etching Duration on the Surface Micromorphology, Roughness, and Wettability of Dental Ceramics. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effects of Sandblasting and Hydrofluoric Acid Etching on Surface Topography, Flexural Strength, Modulus and Bond Strength of Composite Cement to Ceramics. J. Adhes. Dent. 2021, 23, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Smielak, B.; Klimek, L. Effect of hydrofluoric acid concentration and etching duration on select surface roughness parameters for zirconia. J Prosthet Dent. 2015, 113, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urapepon, S. Effect of cement film thickness on shear bond strengths of two resin cements. 2014, 34.

- Maneenacarith, A.; Rakmanee, T.; Klaisiri, A. The influence of resin cement thicknesses on shear bond strength of the cement-zirconia. Jos 2022, 75, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleisa, K.; Habib, S.R.; Ansari, A.S.; Altayyar, R.; Alharbi, S.; Alanazi, S.A.S.; et al. Effect of Luting Cement Film Thickness on the Pull-Out Bond Strength of Endodontic Post Systems. Polymers 2021, 13, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).