Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of Patients

| PCa Patients | |||||

| EBV- single infection | EBV/JCV co-infection | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 41 | 35.7 | 16 | 13.9 | |

| Age | < 60 | 6 | 14.6 | 1 | 6.3 |

| > 60 | 35 | 85.4 | 15 | 93.8 | |

| p | 0.6599 | ||||

| Place of residence | Urban | 28 | 68.3 | 9 | 56.3 |

| Rural | 13 | 31.7 | 7 | 43.8 | |

| p | 0.5379 | ||||

| Smoking | Never | 10 | 24.4 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Ever | 31 | 75.6 | 14 | 87.5 | |

| p | 0.4767 | ||||

| Alcoholabuse | never | 14 | 34.2 | 5 | 31.3 |

| ≤ drink per week | 23 | 56.1 | 10 | 62.5 | |

| > drink per week | 4 | 9.8 | 1 | 6.3 | |

| p | 0.9999 | ||||

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Isolation and Detection of EBV DNA

2.4. Isolation and Detection BKV and JCV

2.5. Antibodies Detection—Serological Methods

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

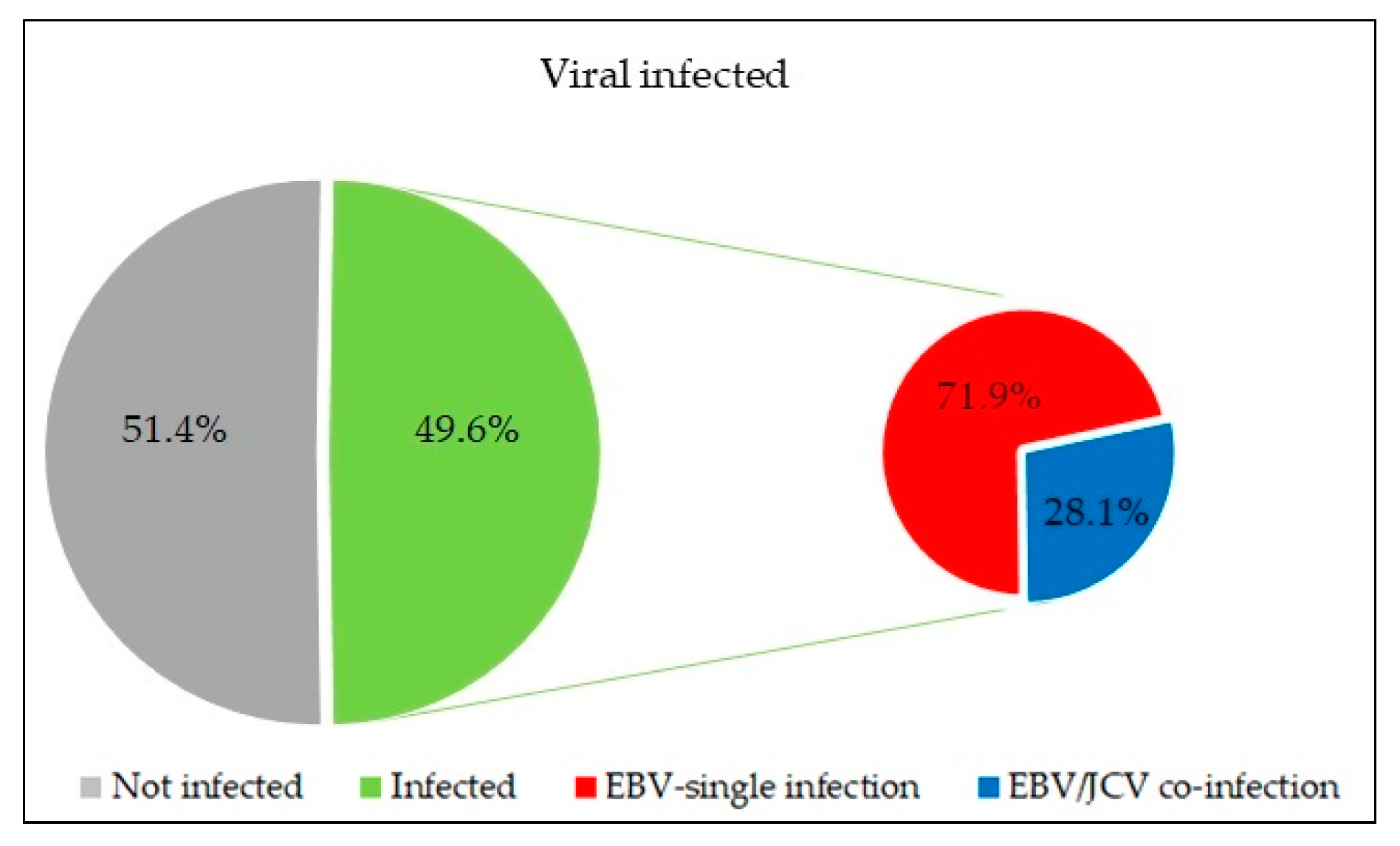

3.1. Evaluation of the Frequency EBV, JCV, BKV in the Tumor Tissue of PCa Patients

3.2. Comparison of Patients with Single EBV Infection and Patients with EBV/JCV Co-Infection in the Context of Risk Group, Gleason Score and TNM Classification

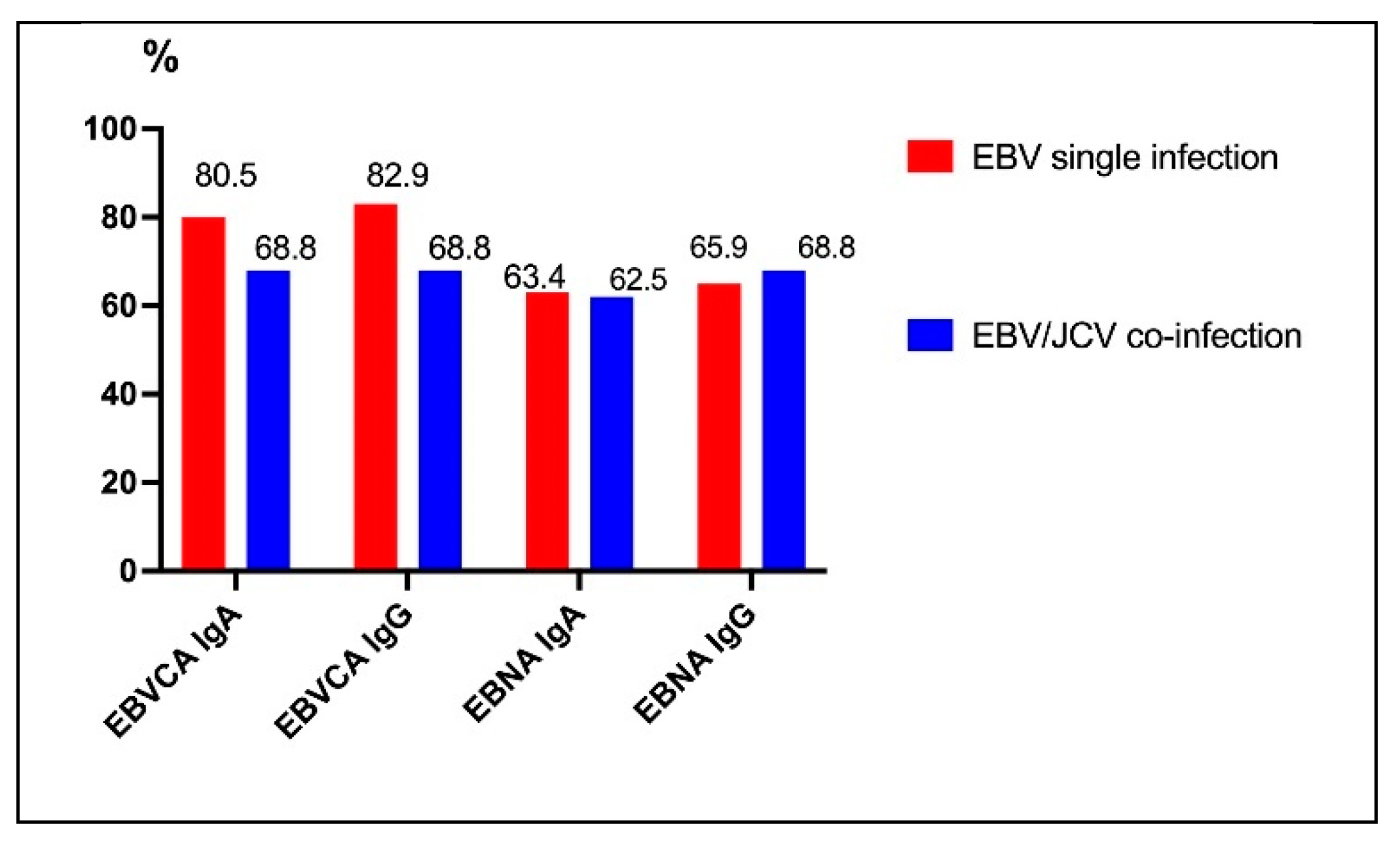

3.3. Frequency of Anti EBV Antibodies in PCa Patients with Ebvsingle Infection Compared with EBV/JCV Co-Infection

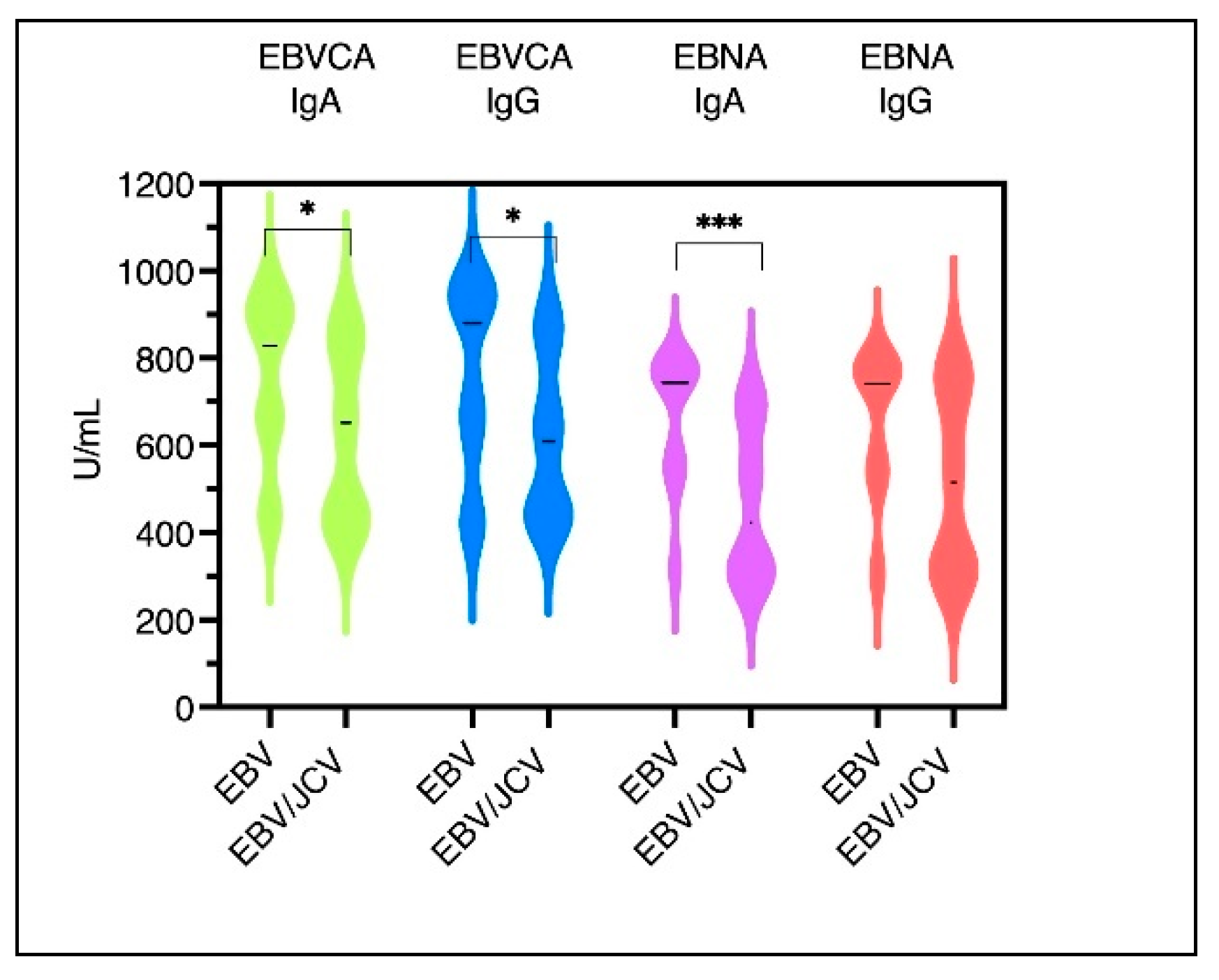

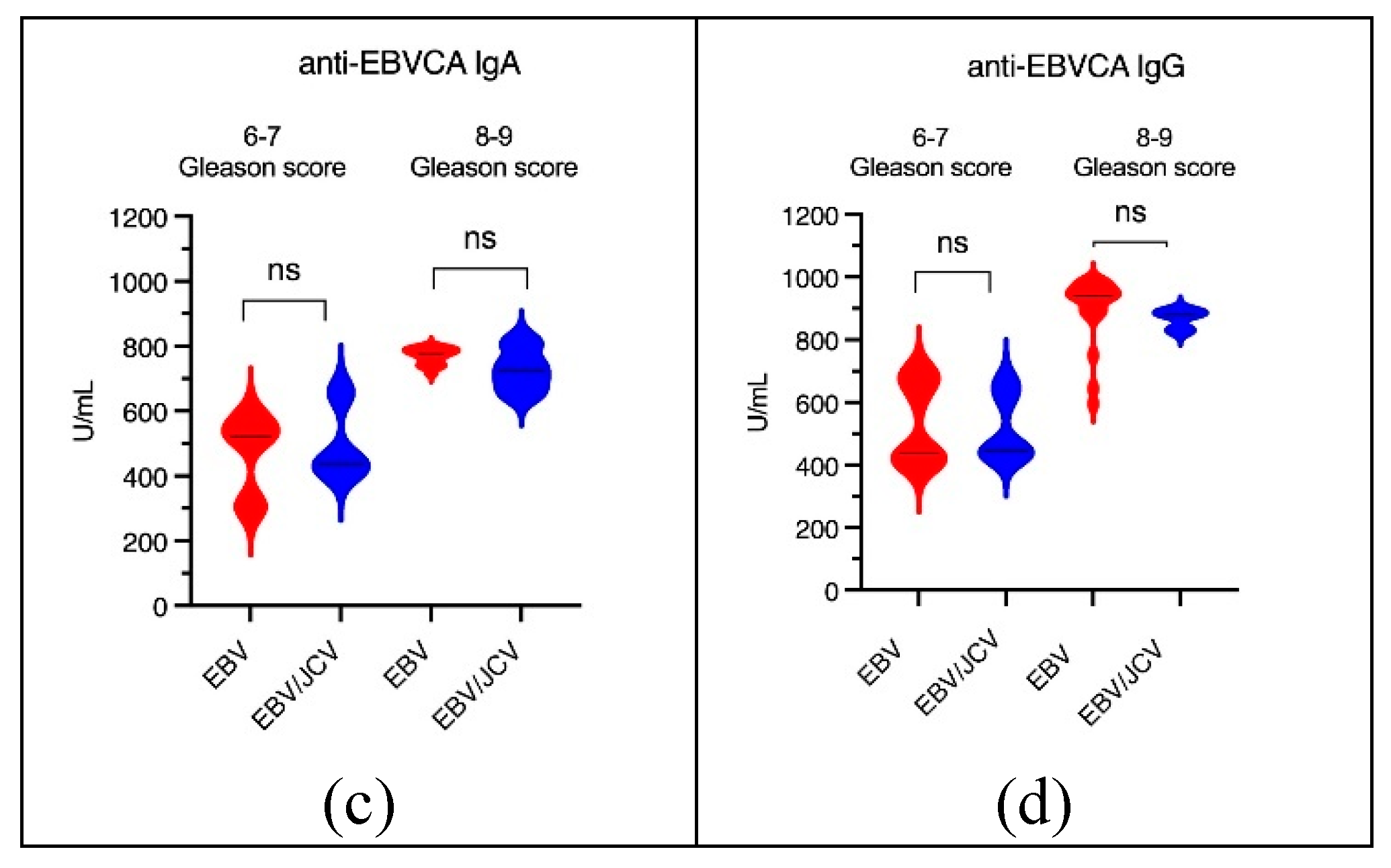

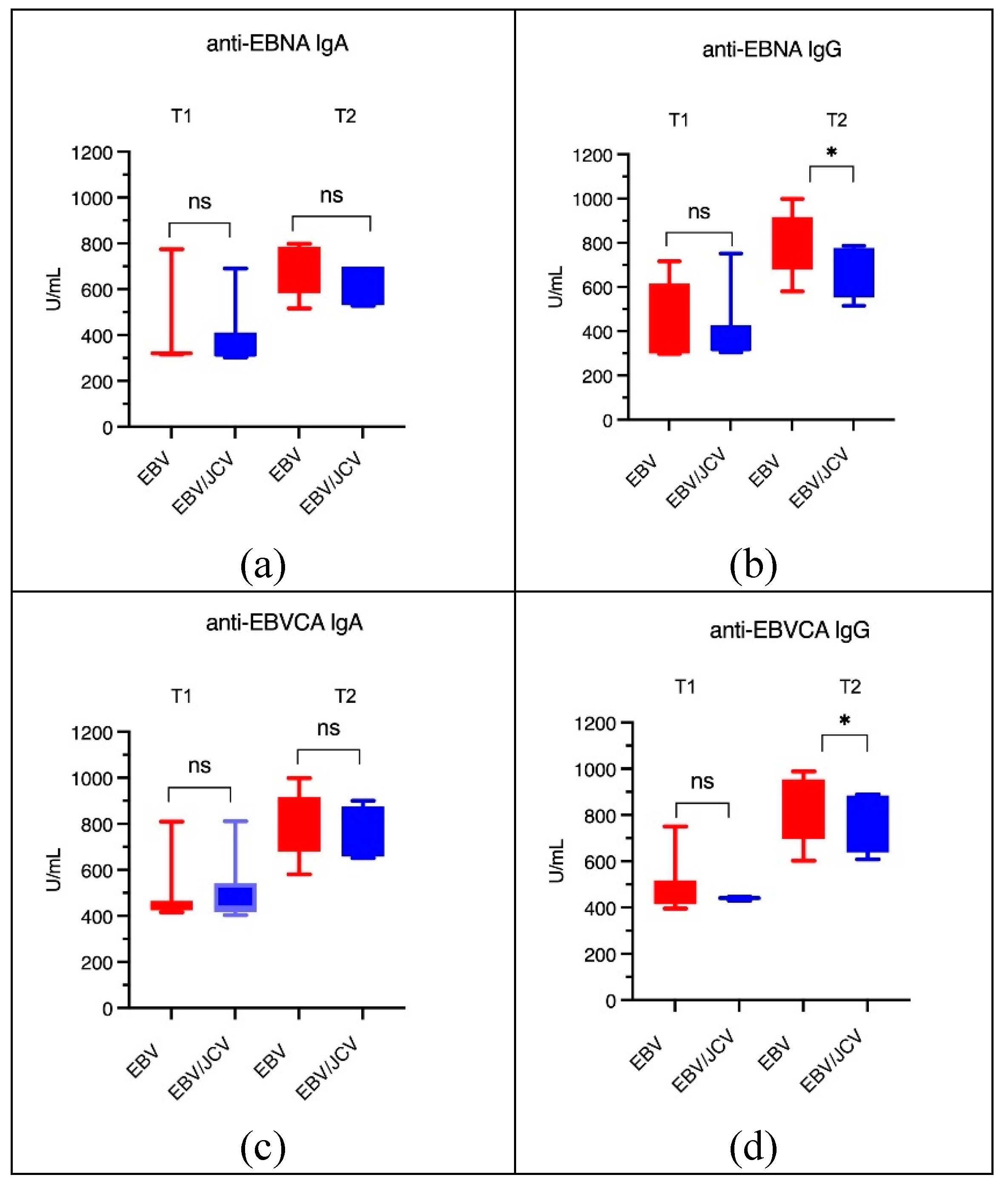

3.4. Antibody Levels for EBVCA IgA and IgG and EBNA1 IgA and IgG in PCa Patients

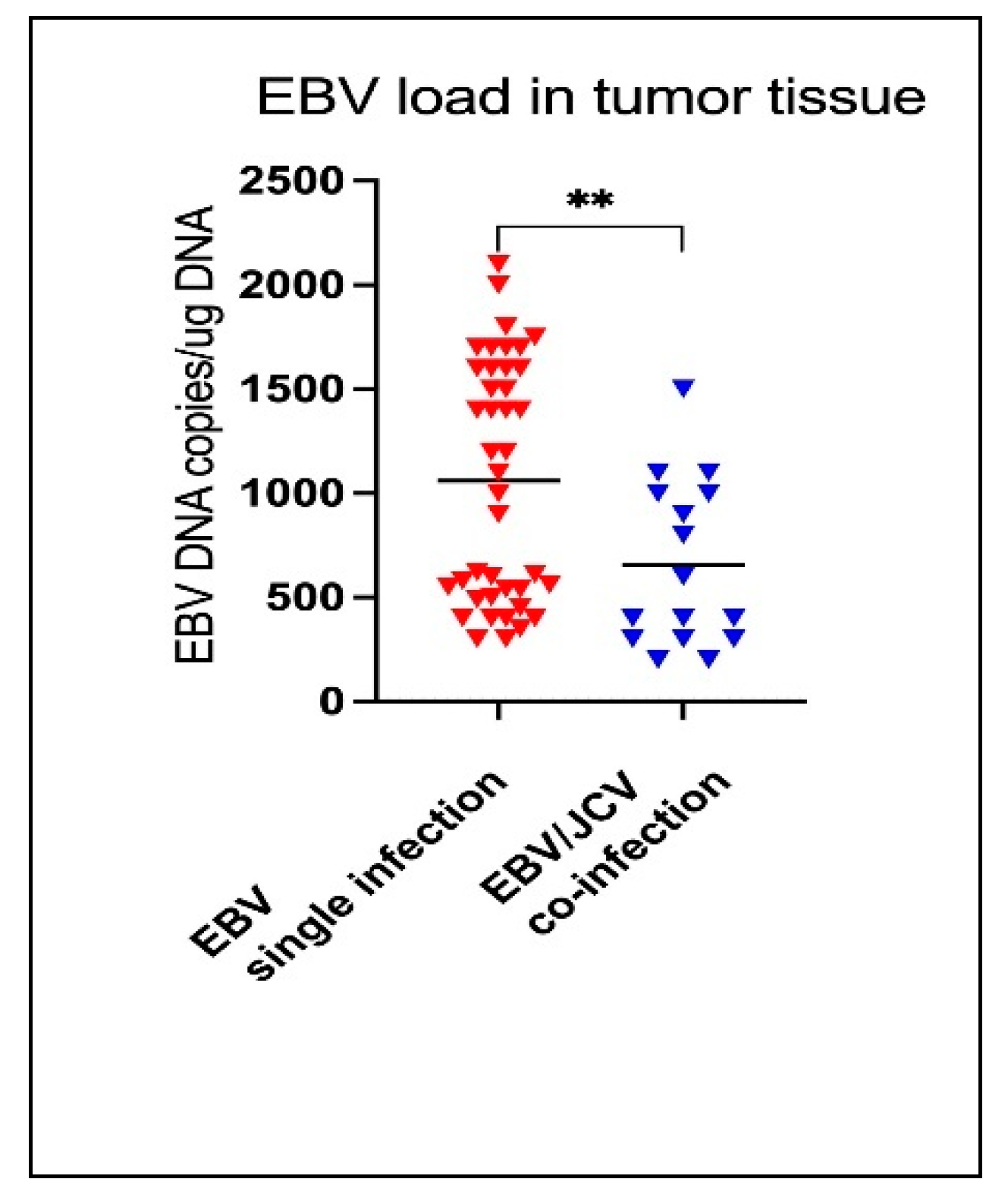

3.5. Comparison of EBV Load in Tumor Tissue in PCa Patients with Single EBV Infection and in Patients with EBV/JCV Co-Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization, International Agency for Research of Cancer Global Cancer Observatory 2022 available online:. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/27-prostate-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Wojciechowska, U.; Didkowska, J.A.; Barańska, K.; Miklewska, M.; Michałek, I.; Olasek, P.; Jawołowska, A. Cancer in Poland in 2022. Maria Skłodowska-Curie National Institute of Oncology. Warsaw, Poland; 2024. Available online: https://onkologia.org.

- Huang, L.; La Bonte, M.J.; Craig, S.G.; Finn, S.P.; Allott, E.H. Inflammation and Prostate Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Identifying Opportunities for Treatment and Prevention. Cancers 2022, 14, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuri, A.; Ditonno, F.; Panunzio, A.; Gozzo, A.; Porcaro, A.B.; Verratti, V.; Cerruto, M.A.; Antonelli, A. Prostatic Inflammation in Prostate Cancer: Protective Effect or Risk Factor? Uro 2021, 1, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitland, N.J.; Collins, A.T. Inflammation as the Primary Aetiological Agent of Human Prostate Cancer: A Stem Cell Connection? J. Cell Biochem. 2008, 105, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Costa, C.; Fernandes, R.; Barros, A.N. Inflammation in Prostate Cancer: Exploring the Promising Role of Phenolic Compounds as an Innovative Therapeutic Approach. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurel, B.; Lucia, M.S.; Thompson, I.M.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Kristal, A.R.; Parnes, H.L.; Hoque, A.; Lippman, S.M.; Sutcliffe, S. Chronic inflammation in benign prostate tissue is associated with high-grade prostate cancer in the placebo arm of the prostate cancer prevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2014, 23, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisanzio, C.; Signoretti, S. P63 in Prostate Biology and Pathology. J. Cell Biochem. 2008, 103, 1354–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caini, S.; Gandini, S.; Dudas, M.; Bremer, V.; Severi, E.; Gherasim, A. Sexually transmitted infections and prostate cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014, 38, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.; Imran, M.; Noreen, M.; Ahmed, F.; Atif, M.; Fatima, Z.; Bilal Waqar, A. Oncogenic role of tumor viruses in humans. Viral Immunol. 2017, 30, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.S.; Chang, Y. Why do viruses cause cancer? Highlights of the first century of human tumour virology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Moore, P.S.; Weiss, R.A. Human oncogenic viruses: nature and discovery. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2017, 372, 20160264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLennan, S.A.; Marra, M.A. Oncogenic Viruses and the Epigenome: How Viruses Hijack Epigenetic Mechanisms to Drive Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumisimir, B.; Mahasneh, I.; Kasmi, Y.; Saif, I.; Hammou, R.A.; Mustafa, M. Prostate cancer and viral infections: epidemiological and clinical indications. Editor(s): Moulay Mustapha Ennaji, Oncogenic Viruses, Academic Press, 2023, 263-272.

- Dalianis, T.; Hirsch, H.H. Human polyomaviruses in disease and cancer. Virology 2013, 437, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisque, R.J.; Bream, G.L.; Cannella, M.T. Human polyomavirus JC virus genome. J. Virol. 1984, 51, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, J.M.; Rao, S.; Wang, M.; Garcea, R.L. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbue, S.; Comar, M.; Ferrante, P. Review on the role of the human Polyomavirus JC in the development of tumors. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, A.; Kalantari, M.; Simoneau, A.; Jensen, J.L.; Villarreal, L.P. Detection of human polyomaviruses and papillomaviruses in prostatic tissue reveals the prostate as a habitat for multiple viral infections. Prostate. 2002, 53, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorish, B.M.T. JC Polyoma Virus as a Possible Risk Factor for Prostate Cancer Development - Immunofluorescence and Molecular Based Case Control Study. Cancer Control. 2022, 29, 10732748221140785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, S.; Gagliano, N.; Procacci, P.; Sartori, P.; Comar, M.; Provenzano, M.; Favi, E.; Ferraresso, M.; Ferrante, P.; Delbue, S. Characterization of an in vitro model to study the possible role of polyomavirus BK in prostate cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 11912–11922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbue, S.; Matei, D.V.; Carloni, C.; Pecchenini, V.; Carluccio, S.; Villani, S.; Tringali, V.; Brescia, A.; Ferrante, P. Evidence supporting the association of polyomavirus BK genome with prostate cancer. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2013, 202, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Sheikh, A.; Fatima, S.; Haider, G.; Ghias, K.; Abbas, F.; Mughal, N.; Abidi, S.H. Detection and characterization of latency stage of EBV and histopathological analysis of prostatic adenocarcinoma tissues. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moens, U.; Prezioso, C.; Pietropaolo, V. Functional Domains of the Early Proteins and Experimental and Epidemiological Studies Suggest a Role for the Novel Human Polyomaviruses in Cancer. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 834368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiś, J.; Góralczyk, M.; Sikora, D.; Stępień, E.; Drop, B.; Polz-Dacewicz, M. Can the Epstein–Barr Virus Play a Role in the Development of Prostate Cancer? Cancers 2024, 16, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.I.; Egevad, L.; Amin, M.B.; Delahunt, B.; Srigley, J.R.; Humphrey, P.A.; Grading Committee. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and Proposal for a New Grading System. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.I.; Zelefsky, M.J.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Nelson, J.B.; Egevad, L.; Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Vickers, A.J.; Parwani, A.V.; Reuter, V.E.; Fine, S.W.; et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the Gleason Score. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines for Prostate Cancer. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer/chapter/classification-and-staging-systems (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Abidi, S.H.; Bilwani, F. , Ghias, K. , Abbas F. Viral etiology of prostate cancer: Genetic alterations and immune response. A literature review, International Journal of Surgery 2018, 52, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balis, V.; Sourvinos, G.; Soulitzis, N.; Giannikaki, E.; Sofras, F.; Spandidos, D.A. Prevalence of BK virus and human papillomavirus in human prostate cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2007, 22(4):245-51.

- Padgett, B.L.; Zu Rhein, G.M.; Walker, D.L.; Echroade, R.; Dessel, B. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Lancet 1971, 1, 1257–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.D.; Field, A.M.; Coleman, D.V.; Hulme, B. New human papovavirus (B.K.) isolated from urine after renal transplantation. Lancet 1971, 1, 1:1253–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzivino, E.; Rodio, D.M.; Mischitelli, M.; Bellizzi, A.; Sciarra, A.; Salciccia, S.; Gentile, V.; Pietropaolo, V. High Frequency of JCV DNA Detection in Prostate Cancer Tissues. Cancer Genomics Proteomics, 2015,12(4):189-200.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Malaria and Some Polyomaviruses (SV40, BK, JC, and Merkel Cell Viruses), Lyon 2013, 104.

- Jiang, M.; Abend, J.R.; Johnson, S.F.; Imperiale, M.J. The role of polyomaviruses in human disease. Virology, 2009, 384(2):266-73.

- Prado, J.C.M.; Monezi, T.A.; Amorim, A.T.; Lino, V.; Paladino, A.; Boccardo, E. Human polyomaviruses and cancer: an overview. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 2018, 73(suppl 1):e558s.

- Shen, C. , Tung, C., Chao, C. Jou Y. Huang S.; Meng M.; Chang D.; Chen P. The differential presence of human polyomaviruses, JCPyV and BKPyV, in prostate cancer and benign prostate hypertrophy tissues. BMC Cancer 2021, 21: 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Leach, R.J.; Gomez-Guerra, L.S.; Gomez-Guerra, L.; Garza-Guajardo, R.; et al. Identification of viral infections in the prostate and evaluation of their association with cancer, BMC Cancer 2010, 10: 326. 10.

- Zheng, Z.M. Viral oncogenes, noncoding RNAs, and RNA splicing in human tumor viruses. Int. J. Biol. Sci, 2010, 6(7): 730–755. 41.

- Barbier, M.T.; Del Valle, L. Co-Detection of EBV and Human Polyomavirus JCPyV in a Case of AIDS-Related Multifocal Primary Central Nervous System Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Viruses 2023, 15, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbinyan, A.; White, M.K.; Akan, S.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Del Valle, L.; Amini, S.; Khalili, K. Alterations of DNA damage repair pathways resulting from JCV infection. Virology 2007, 364, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Valle, L.; Gordon, J.; Assimakopoulou, M.; Enam, S.; Geddes, J.F.; Varakis, J.N.; Katsetos, C.D.; Croul, S.; Khalili, K. Detection of JC Virus DNA sequences and expression of the viral regulatory protein T-Antigen in tumors of the Central Nervous System. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4287–4293. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, M.J.; Parker Struckhoff, A.; Trillo-Tinoco, J.; Li, L.; Margolin, D.A.; McGoey, R.; Del Valle, L. Activation of c-Myc and Cyclin D1 by JCV T-Antigen and beta-catenin in colon cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Papenhausen, P.; Shao, H. The Role of c-MYC in B-Cell Lymphomas: Diagnostic and Molecular Aspects. Genes 2017, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobedo-Bonilla, C.M. Mini Review: Virus Interference: History, Types and Occurrence in Crustaceans. Front. Immunol, 2021, 12:674216.

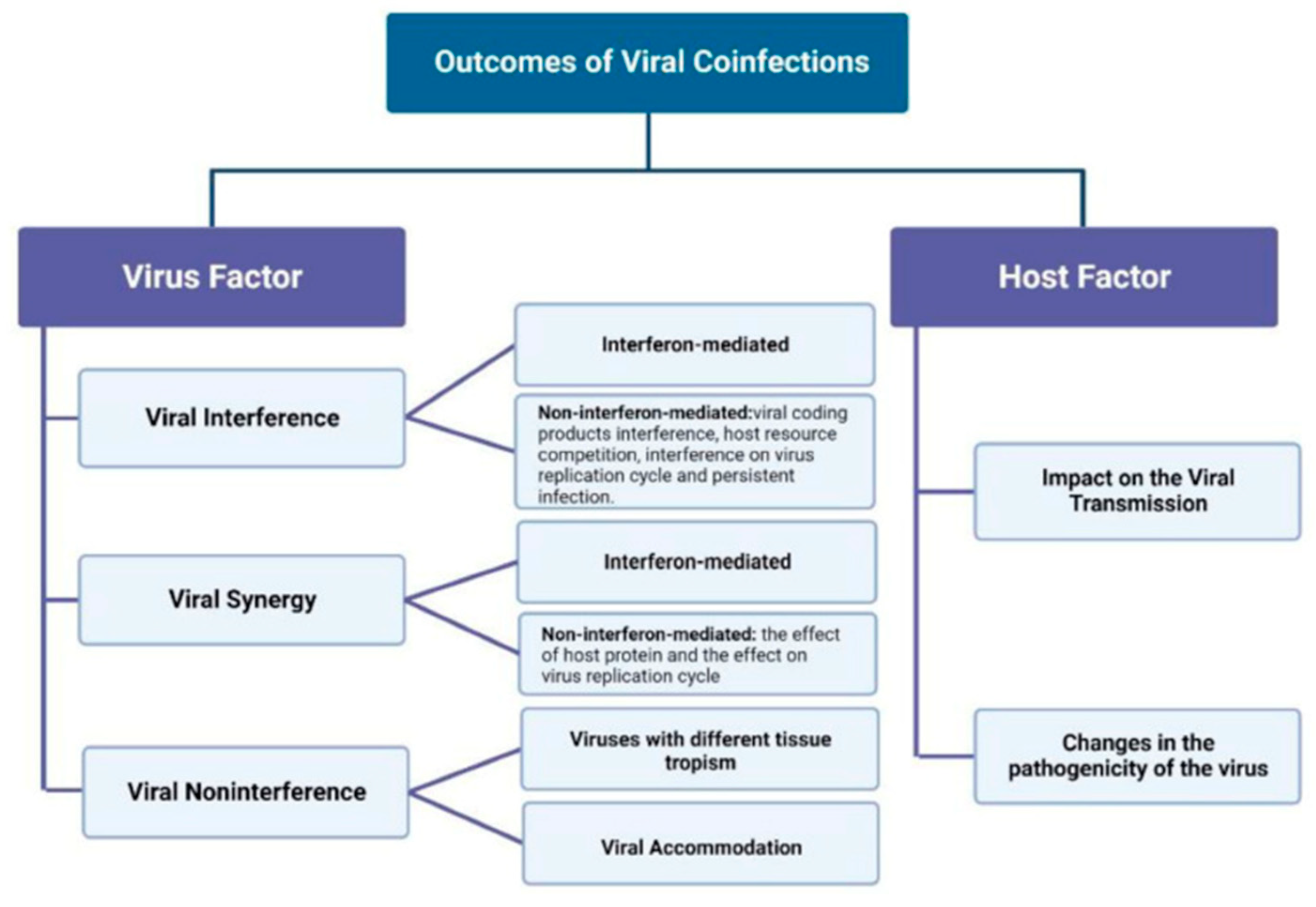

- Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Viral Coinfections. Viruses, 2022;14(12):2645.

- Goto, H. , Ihira H., Morishita K., Tsuchiya M., Ohta K., Yumine N., Tsurudome M., Nishio M. Enhanced growth of influenza A virus by coinfection with human parainfluenza virus type 2. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 205: 209–218.

- Chu, C.-J. , Lee S.-D. Hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus coinfection: Epidemiology, clinical features, viral interactions and treatment. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moens, U. ; Van Ghule, M; Ehlers, B. Are human polyomaviruses co-factors for cancers induced by other oncoviruses? Rev Medical Virology, 2014, 24(5): 343-360.

- Ahmed, K. , Sheikh A., Fatima S., Haider G., Ghias K., Abbas F., Mughal N., Abidi S.H. Detection and characterization of latency stage of EBV and histopathological analysis of prostatic adenocarcinoma tissues. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12:10399.. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, N.J. , Glenn W.K., Sahrudin A., Orde M.M., Delprado W., Lawson J.S. Human papillomavirus and Epstein Barr virus in prostate cancer: Koilocytes indicate potential oncogenic influences of human papillomavirus in prostate cancer. Prostate 2013, 73, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahand, J.S. , Khanaliha K., Mirzaei H., Moghoofei M., Baghi H.B., Esghaei M., Khatami A.R., Fatemipour M., Bokharaei-Salim F. Possible role of HPV/EBV coinfection in anoikis resistance and development in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2021, 21:926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaolo V, Prezioso C, Bagnato F, Antonelli G. John Cunningham virus: an overview on biology and disease of the etiological agent of the progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. New Microbiol, 2018,41(3):179-186.

- Ferreira, A.D.; Tayyar, Y.; Idris, A.; McMillan, N.A.J. A “hit-and-run” affair – A possible link for cancer progression in virally driven cancers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, 2021, 1875(1):188476.

- Lawson JS, Glenn WK. Multiple pathogens and prostate cancer. Infect Agent Cancer, 2022, 17(1):23.

- zur Hausen The Search for Infectious Causes of Human Cancers: Where and Why (Nobel Lecture), Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2009, 48(32), 2009, 48(32): 5769-5969.

| PCa Patients | |||||

| EBV single infection N = 41 |

EBV/JCV co-infection N = 16 |

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Risk | Low | 10 | 24.4 | 9 | 56.2 |

| Intermediate/ high | 31 | 75.6 | 7 | 43.8 | |

| p | 0.0307* | ||||

| Gleason score | 6-7 | 18 | 43.9 | 12 | 75.0 |

| 8-9 | 23 | 56.1 | 4 | 25.0 | |

| p | 0.0430* | ||||

| T | T1 | 11 | 26.8 | 10 | 62.5 |

| T2 | 30 | 73.2 | 6 | 37.5 | |

| T3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| T4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| p | 0.0166* | ||||

| N | N0 | 41 | 100.0 | 16 | 100.0 |

| M | M0 | 41 | 100.0 | 16 | 100.0 |

| EBV-positive | EBV/JCV coinfection | |||||||||

| Low risk | Intermediate/ high risk |

p | Low risk | Intermediate/ high risk |

p | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| n=10 | n=30 | n=9 | n=7 | |||||||

| EBVCA IgA |

7 | 70.00 | 26 | 86.67 | 0.2297 | 5 | 55.56 | 6 | 85.71 | 0.1967 |

| EBVCA IgG |

9 | 90.00 | 25 | 83.33 | 0.9090 | 5 | 55.56 | 6 | 85.71 | 0.1967 |

| EBNA IgA |

3 | 30.00 | 23 | 83.33 | 0.0036* | 5 | 55.56 | 5 | 71.43 | 0.5153 |

| EBNA IgG |

4 | 40.00 | 23 | 83.33 | 0.0159* | 5 | 55.56 | 6 | 85.71 | 0.1967 |

| EBV- single infection | EBV/JCV co-infection | |||||||||

| 6-7 Gleason score |

8-9 Gleason score |

p | 6-7 Gleason score |

8-9 Gleason score |

p | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| n=18 | n=23 | n=12 | n=4 | |||||||

| EBVCA IgA | 12 | 66.67 | 13 | 56.52 | 0.5087 | 7 | 58.33 | 4 | 100.00 | 0.1195 |

| EBVCA IgG | 13 | 72.22 | 21 | 91.30 | 0.1071 | 8 | 66.67 | 3 | 75.00 | 0.7555 |

| EBNA IgA | 9 | 50.00 | 17 | 73.91 | 0.0217* | 7 | 58.33 | 3 | 75.00 | 0.5510 |

| EBNA IgG | 10 | 55.56 | 17 | 73.91 | 0.2186 | 7 | 58.33 | 4 | 100.00 | 0.1195 |

| EBV single infection | EBV/JCV co-infection | |||||||||

| T1 | T2 | p | T1 | T2 | p | |||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n (%) | (%) | |||

| n=11 | n=30 | n=10 | n=6 | |||||||

| EBVCA IgA | 7 | 63.64 | 26 | 86.67 | 0.0992 | 6 | 60.00 | 5 | 83.33 | 0.3296 |

| EBVCA IgG | 9 | 81.82 | 25 | 83.33 | 0.9090 | 5 | 50.00 | 6 | 100.00 | 0.0367* |

| EBNA IgA | 3 | 27.27 | 23 | 76.67 | 0.0036* | 6 | 60.00 | 4 | 66.67 | 0.7897 |

| EBNA IgG | 4 | 36.36 | 23 | 76.67 | 0.0159* | 6 | 60.00 | 5 | 83.33 | 0.3296 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).