Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

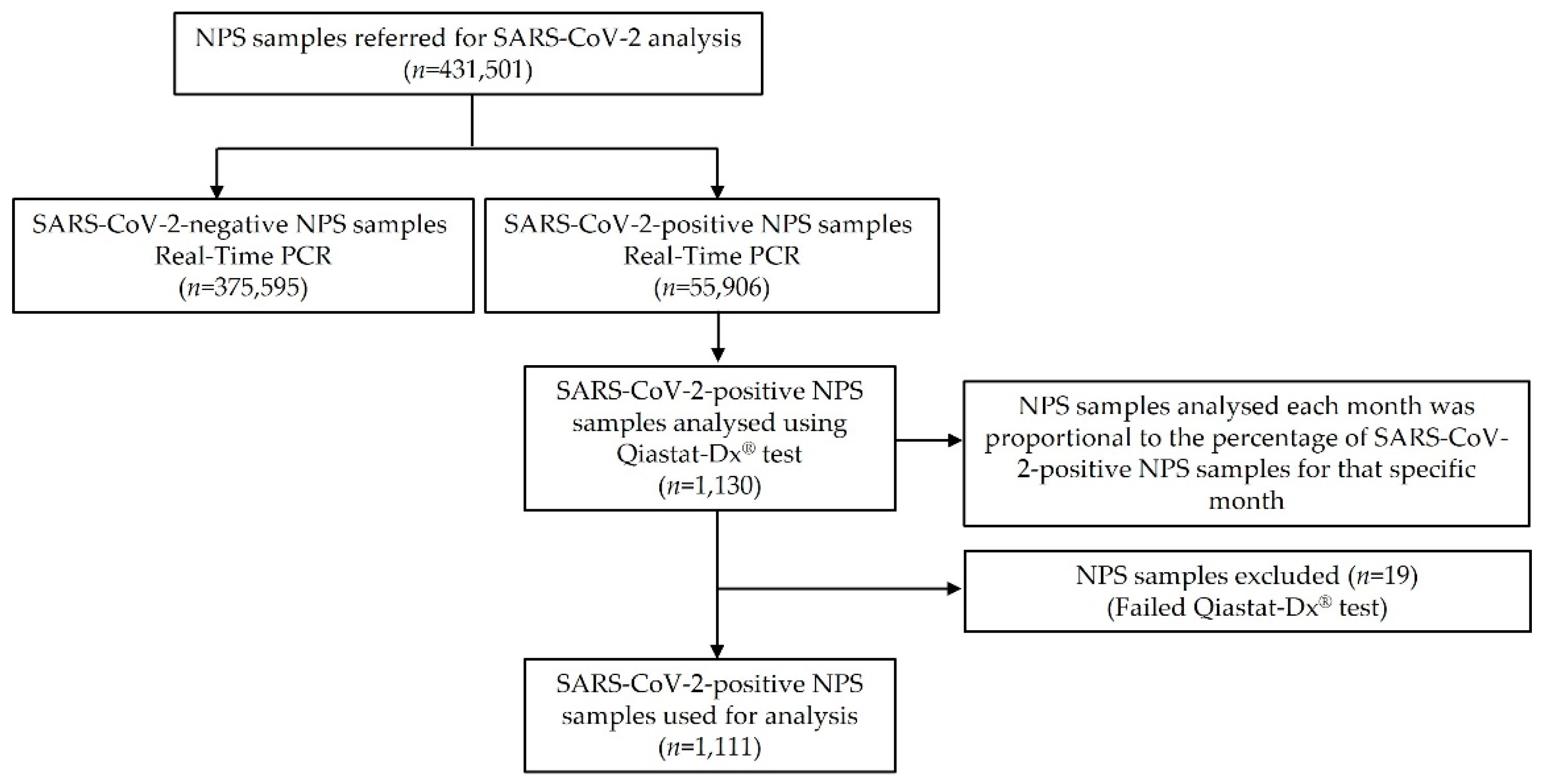

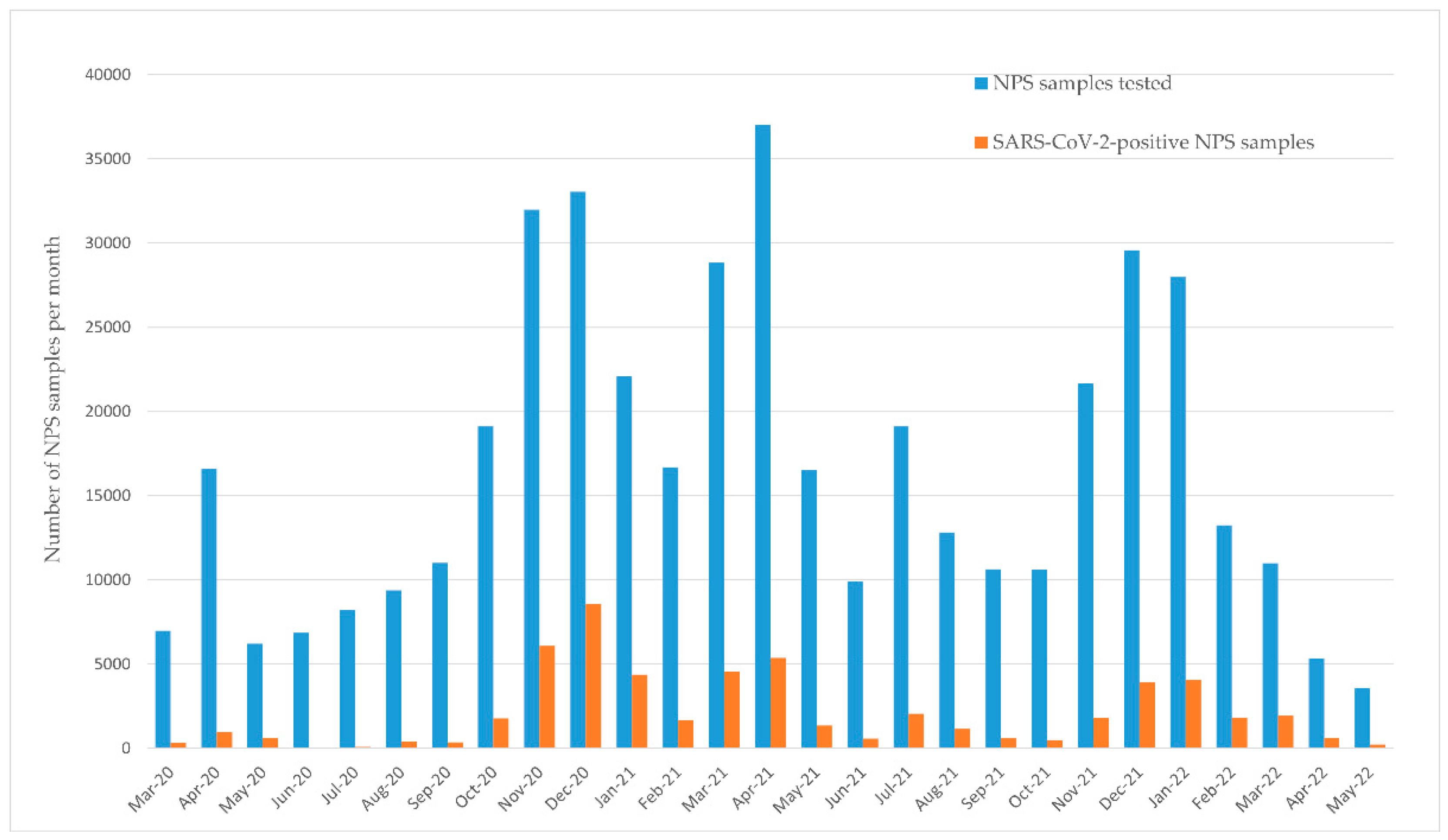

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. QIAstat-Dx® Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Panel

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

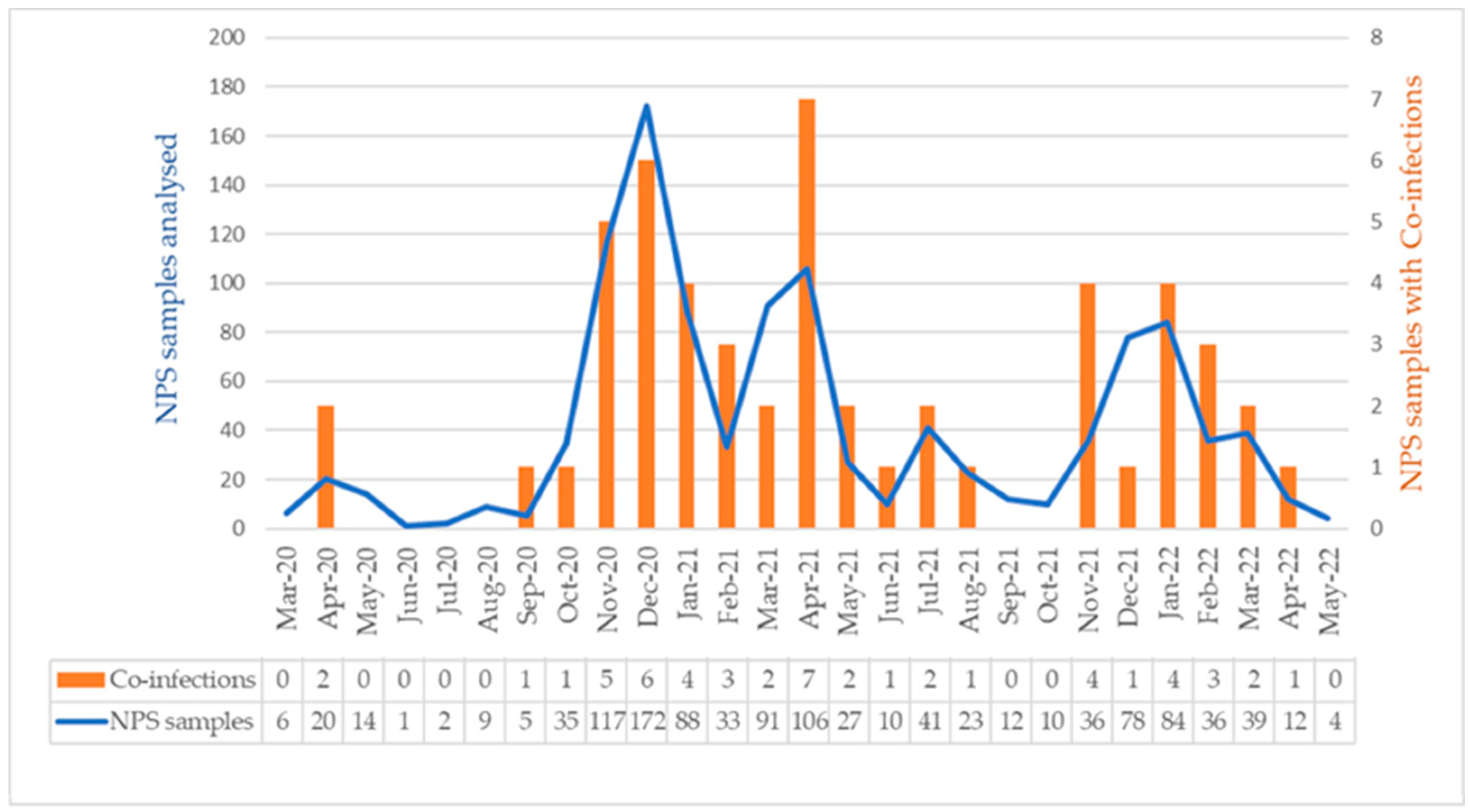

3.1. Co-Infection of Respiratory Pathogens with SARS-CoV-2

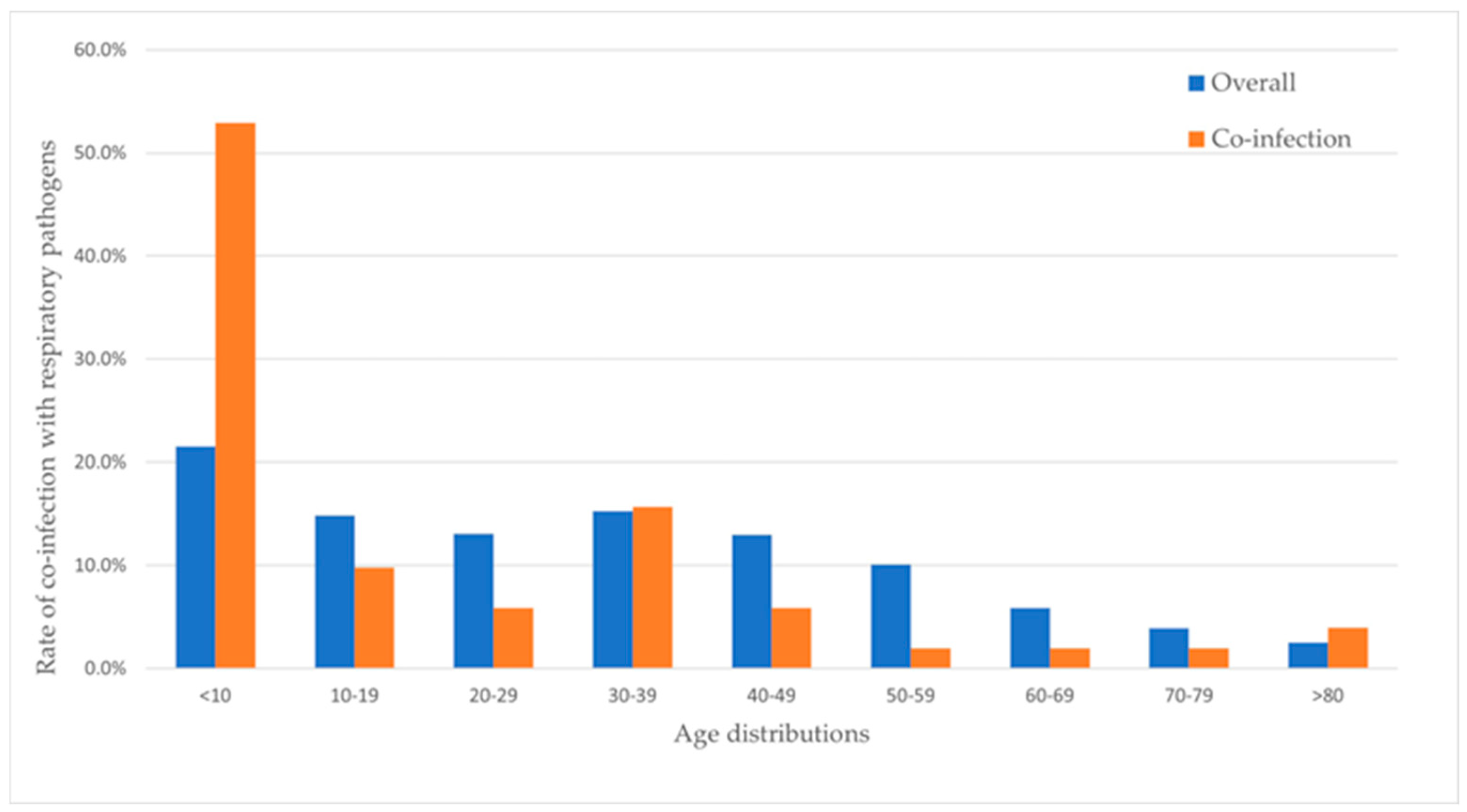

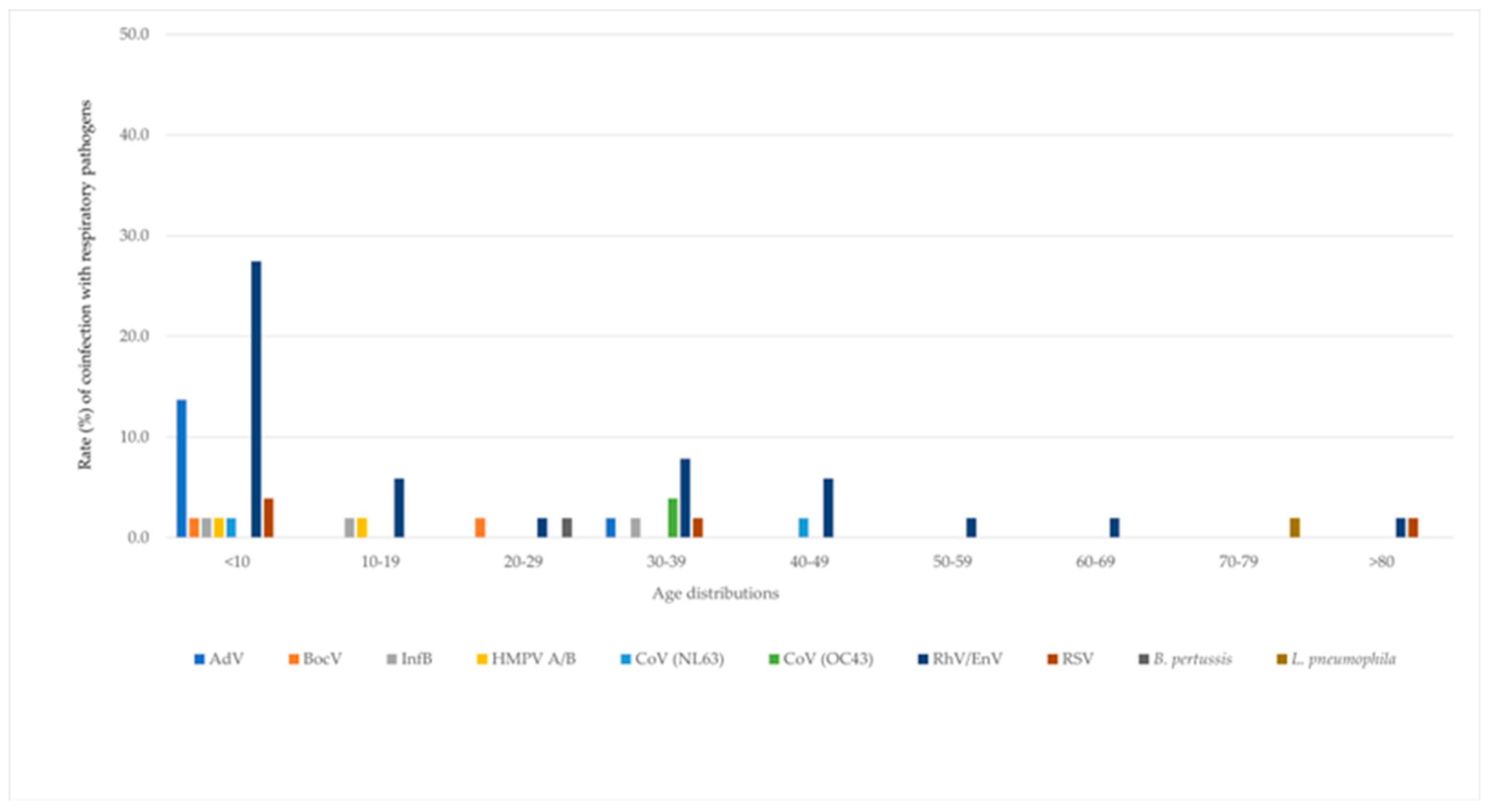

3.2. Variation of Co-Infection with Age Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPS | Nasopharengeal swab |

| RhV | Rhinovirus |

| EnV | Enterovirus |

| HMPV A/B | Human metapneumovirus A/B |

| CoV | Coronavirus |

| BocV | Bocavirus |

| LP | Legionella pneumophilia |

| BP | Bordetella pertussis |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Q. Unique Epidemiological and Clinical Features of the Emerging 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) Implicate Special Control Measures. J Med Virol 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, I.; Öztürk, R. From Asymptomatic to Critical Illness: Decoding Various Clinical Stages of COVID-19. Turk J Med Sci 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, F.; Vesal, S.; Goudarzi, P.; Sahafnejad, Z.; Khoshbayan, A. The Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 with Atypical Bacterial Respiratory Infections: A Mini Review. Vacunas 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Havasi, A.; Visan, S.; Cainap, C.; Cainap, S.S.; Mihaila, A.A.; Pop, L.A. Influenza A, Influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2 Similarities and Differences – A Focus on Diagnosis. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; Zhao, H.; Guy, R.; Muller-Pebody, B.; Zambon, M.; Andrews, N.; Ramsay, M.; Lopez Bernal, J. Interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza, and the Impact of Coinfection on Disease Severity: A Test-Negative Design. Int J Epidemiol 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.R.; Lin, Y.L.; Wan, C.K.; Wu, J.T.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chiu, M.H.; Huang, C.H. Co-Infection of Influenza B Virus and SARS-CoV-2: A Case Report from Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Zhang, M.; Xing, L.; Wang, K.; Rao, X.; Liu, H.; Tian, J.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Y.; Shang, J. The Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Viruses in Patients during COVID-19 Outbreak. J Med Virol 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.J.; Orihuela, C.J.; Harrod, K.S.; Bhuiyan, M.A.N.; Dominic, P.; Kevil, C.G.; Fort, D.; Liu, V.X.; Farhat, M.; Koff, J.L.; et al. COVID-19 Bacteremic Co-Infection Is a Major Risk Factor for Mortality, ICU Admission, and Mechanical Ventilation. Crit Care 2023, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Faramarzi, S.; Zandi, M.; Shahbahrami, R.; Jafarpour, A.; Akhavan Rezayat, S.; Pakzad, I.; Abdi, F.; Malekifar, P.; Pakzad, R. Bacterial Coinfection among Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patient Groups: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. New Microbes New Infect 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuuza, J.S.; Watson, L.; Parmasad, V.; Putman-Buehler, N.; Christensen, L.; Safdar, N. Prevalence and Outcomes of Co-Infection and Superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and Other Pathogens: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.; Fanis, P.; Tryfonos, C.; Koptides, D.; Krashias, G.; Bashiardes, S.; Hadjisavvas, A.; Loizidou, M.; Oulas, A.; Alexandrou, D.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Cyprus. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, J.; Koptides, D.; Tryfonos, C.; Alexandrou, D.; Christodoulou, C. Introduction, Spread and Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variants BA.1 and BA.2 in Cyprus. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebourgeois, S.; Storto, A.; Gout, B.; Le Hingrat, Q.; Ardila Tjader, G.; Cerdan, M. del C.; English, A.; Pareja, J.; Love, J.; Houhou-Fidouh, N.; et al. Performance Evaluation of the QIAstat-Dx® Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Panel. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikane, M.; Unoki-Kubota, H.; Moriya, A.; Kutsuna, S.; Ando, H.; Kaburagi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Iwamoto, N.; Kimura, M.; Ohmagari, N. Evaluation of the QIAstat-Dx Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Panel, a Rapid Multiplex PCR Method for the Diagnosis of COVID-19. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caza, M.; Hayman, J.; Jassem, A.; Wilmer, A. Evaluation of the QIAstat-Dx Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Panel for Detection of Pathogens in Nasopharyngeal and Lower Respiratory Tract Specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 110, 116368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebourgeois, S.; Storto, A.; Gout, B.; Le Hingrat, Q.; Ardila Tjader, G.; Cerdan, M.D.C.; English, A.; Pareja, J.; Love, J.; Houhou-Fidouh, N.; et al. Performance Evaluation of the QIAstat-Dx® Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Panel. Int J Infect Dis 2021, 107, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W.S. Co-Infections in People with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Infection 2020, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuuza, J.S.; Watson, L.; Parmasad, V.; Putman-Buehler, N.; Christensen, L.; Safdar, N. Prevalence and Outcomes of Co-Infection and Superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and Other Pathogens: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Moore, L.S.P.; Zhu, N.; Ranganathan, N.; Skolimowska, K.; Gilchrist, M.; Satta, G.; Cooke, G.; Holmes, A. Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals with Coronavirus: A Rapid Review to Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garazzino, S.; Montagnani, C.; Donà, D.; Meini, A.; Felici, E.; Vergine, G.; Bernardi, S.; Giacchero, R.; Lo Vecchio, A.; Marchisio, P.; et al. Multicentre Italian Study of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents, Preliminary Data as at 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripa, M.; Galli, L.; Poli, A.; Oltolini, C.; Spagnuolo, V.; Mastrangelo, A.; Muccini, C.; Monti, G.; De Luca, G.; Landoni, G.; et al. Secondary Infections in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19: Incidence and Predictive Factors. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021, 27, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Giordano, C.; Leonildi, A.; Menichini, M.; Vecchione, A.; Pistello, M.; Guarracino, F.; Ghiadoni, L.; Forfori, F.; et al. Predictors of Hospital-Acquired Bacterial and Fungal Superinfections in COVID-19: A Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaras, R.; Cirpin, R.; Duran, A.; Duman, H.; Arslan, O.; Bakcan, Y.; Kaya, M.; Mutlu, H.; Isayeva, L.; Kebanlı, F.; et al. Influenza and COVID-19 Coinfection: Report of Six Cases and Review of the Literature. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, H.K.-A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Aburahma, M.Z.; Elkhawaga, A.A.; El-Mokhtar, M.A.; Sayed, I.M.; Hosni, A.; Hassany, S.M.; Medhat, M.A. Predictors of Severity and Co-Infection Resistance Profile in COVID-19 Patients: First Report from Upper Egypt. Infect Drug Resist 2020, 13, 3409–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Jadán, D.; Muslin, C.; Viteri-Dávila, C.; Coronel, B.; Castro-Rodríguez, B.; Vallejo-Janeta, A.P.; Henríquez-Trujillo, A.R.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M.A.; Rivera-Olivero, I.A. Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 with Other Respiratory Pathogens in Outpatients from Ecuador. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1264632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Quinn, J.; Pinsky, B.; Shah, N.H.; Brown, I. Rates of Co-Infection between SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2020, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, M.C.; Russell, C.D.; Harrison, E.M.; Docherty, A.B.; Lone, N.; Girvan, M.; Hardwick, H.E.; Visser, L.G.; Openshaw, P.J.M.; Groeneveld, G.H.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Co-Infection with Influenza Viruses, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, or Adenoviruses. The Lancet 2022, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miatech, J.L.; Tarte, N.N.; Katragadda, S.; Polman, J.; Robichaux, S.B. A Case Series of Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Virus in Louisiana. Respir Med Case Rep 2020, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ding, G.; Shu, T.; Fu, S.; Tong, W.; Tu, X.; Li, S.; Wu, D.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. The Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Interfered with Influenza in Wuhan. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, M.; Khaleghnejad, S.; Abedi Elkhichi, P.; Goudarzi, M.; Goudarzi, H.; Taghavi, A.; Vaezjalali, M.; Hajikhani, B. COVID-19 and Influenza Co-Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Li, K.; Lei, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, Q.; Wei, S. Prevalence and Associated Outcomes of Coinfection between SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, T.L.; Hoang, V.T.; Colson, P.; Million, M.; Gautret, P. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Viruses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Virology Plus 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpour, M.; Jalali, H.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Talarposhti, M.R.; Mousavi, T.; Ghara, A.A.N. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A/B among Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2025, 25, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, P.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Harvala, H.; Hovi, T.; Knowles, N.J.; Lindberg, A.M.; Oberste, M.S.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Reuter, G.; Skern, T.; et al. Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Enteroviruses and Rhinoviruses. Arch Virol 2020, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A.; Collison, M.; Pisano, J.; Kumar, M.; Oehler, C.; Ridgway, J.P. Coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.D.; Sordillo, E.M.; Gitman, M.R.; Paniz Mondolfi, A.E. Coinfection in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients: Where Are Influenza Virus and Rhinovirus/Enterovirus? J Med Virol 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, M.D.; Green, D.A.; Berry, G.J.; Wu, F. Assessing Respiratory Viral Exclusion and Affinity Interactions through Co-Infection Incidence in a Pediatric Population during the 2022 Resurgence of Influenza and RSV. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimura, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Sato, Y.; Miura, H.; Sato, A.; Katsura, H.; Kondo, M.; Itabashi, M.; Tagaya, E. SARS-CoV-2 Co-Detection with Other Respiratory Pathogens-Descriptive Epidemiological Study. Respir Investig 2024, 62, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbein, H.; Kümmel, L.S.; Fragkou, P.C.; Thölken, C.; Hünerbein, B.L.; Reiter, R.; Papathanasiou, K.A.; Renz, H.; Skevaki, C. Respiratory Viral Co-Infections in Patients with COVID-19 and Associated Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev Med Virol 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifipour, E.; Shams, S.; Esmkhani, M.; Khodadadi, J.; Fotouhi-Ardakani, R.; Koohpaei, A.; Doosti, Z.; Ej Golzari, S. Evaluation of Bacterial Co-Infections of the Respiratory Tract in COVID-19 Patients Admitted to ICU. BMC Infect Dis 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.P.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial Co-Infection and Secondary Infection in Patients with COVID-19: A Living Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeiza, S.S.; Shuaibu Bello, A.; Shuaibu, M.G. Random Effects Meta-Analysis of COVID-19/S. Aureus Partnership in Co-Infection. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, A.I.; Himsawi, N.M.; Abu-Raideh, J.A.; Sammour, A.; Safieh, H.A.; Obeidat, A.; Azab, M.; Tarifi, A.A.; Al Khawaldeh, A.; Al-Momani, H.; et al. Prevalence of SARS-COV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens among a Jordanian Subpopulation during Delta-to-Omicron Transition: Winter 2021/2022. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaba, S.M.; Jones, G.; Helsel, T.; Smith, L.L.; Avery, R.; Dzintars, K.; Salinas, A.B.; Keller, S.C.; Townsend, J.L.; Klein, E.; et al. Prevalence of Co-Infection at the Time of Hospital Admission in COVID-19 Patients, A Multicenter Study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinands, J.M.; Olsho, L.E.W.; Agan, A.A.; Bhat, N.; Sullivan, R.M.; Hall, M.; Mourani, P.M.; Thompson, M.; Randolph, A.G. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccine against Life-Threatening RT-PCR-Confirmed Influenza Illness in US Children, 2010-2012. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli Incalzi, R.; Consoli, A.; Lopalco, P.; Maggi, S.; Sesti, G.; Veronese, N.; Volpe, M. Influenza Vaccination for Elderly, Vulnerable and High-Risk Subjects: A Narrative Review and Expert Opinion. Intern Emerg Med 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Budd, A.P.; Brammer, L.; Sullivan, S.; Pineda, R.F.; Cohen, C.; Fry, A.M. Decreased Influenza Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n=1,111 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 518 | 46.6 |

| Female | 593 | 53.4 |

| Age | ||

| <10 | 239 | 23.9 |

| 10-19 | 165 | 16.5 |

| 20-29 | 145 | 14.5 |

| 30-39 | 170 | 17.0 |

| 40-49 | 144 | 14.4 |

| 50-59 | 112 | 11.2 |

| 60-69 | 65 | 6.5 |

| 70-79 | 43 | 4.3 |

| >80 | 28 | 2.8 |

| Year | ||

| Mar 20-Dec 20 | 381 | 34.2 |

| Jan 21-Dec 21 | 555 | 50.0 |

| Jan 22-May 22 | 175 | 15.8 |

| Year | NPS n (%) |

NPS +ve for one other virus n (%) | NPS +ve for two other viruses n (%) | NPS +ve for bacteria n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 381 (34.3) | 12 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) |

| 2021 | 555 (49.9) | 25 (4.5) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| 2022 | 175 (15.8) | 10 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 1,111 | 47 (4.1) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

| Year | RhV/EnV n (%) |

HMPV A/B n (%) |

AdV n %) |

CoV (NL63) n (%) |

CoV (OC43) n (%) |

InfB n (%) |

RSV n (%) |

BocV n (%) |

LP n (%) |

BP n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 9 (2.4) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.3) |

1 (0.3) |

| 2021 | 14 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.5) |

2 (0.4) |

2 (0.4) |

3 (0.5) |

3 (0.5) |

2 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| 2022 | 5 (2.9) |

2 (1.1) |

3 (1.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Total |

28 (2.5) |

2 (0.2) |

8 (0.7) |

2 (0.2) |

2 (0.2) |

3 (0.3) |

4 (0.4) |

2 (0.2) |

1 (0.1) |

1 (0.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).