1. Introduction

The Thomas-Fermi (TF) model is the simplest of all orbital-free density functional theories for determining the electron-components of thermodynamic properties of materials [

1,

2]. Its finite-temperature generalization, together with the spherical atomic cell concept, is commonly used for computing electron-properties of hot dense matter [

3]. The TF model leads to a nonlinear boundary value problem that is to be solved using numerical techniques [

4]. Important improvements to the original algorithm to solve the TF equation have also been reported [

5]. Addition of the quantum mechanical exchange correction to the TF model leads to Thomas-Fermi-Dirac (TFD) model, while the Thomas-Fermi-Dirac-Weizsäcker (TFDW) model is obtained when electron-density gradient corrections are accounted [

6]. The quantum statistical model (QSM) belongs to the same class although its development yielded the correct coefficient of the gradient term in the energy functinal [

7]. Numerical computations of electron-component of equation of state (EOS) using the QSM is somewhat involved. Moreover, there is no scaling of thermodynamic properties with atomic (Z) and mass (A) numbers [

8,

9]. Applications of TF model indeed demonstrate the need to account for the electron binding effects even in obtaining thermal part of electronic properties [

10]. Available analytical representations [

11,

12] of tabulated numerical results are not sufficiently accurate in the wide density-temperature plane required for applications. Perturbation solutions starting from the hot-curve (fully ionized state) do not explicitly account for the nuclear potential in the results [

13]. The excellent compilation of approximate analytical solutions of TF equation [

14] reinforces the need for efficient numerical schemes.

The well known method to solve the TF equation is to rewrite it as a Voltera integral equation and thereafter formulate a discrete version and then apply the shooting method to obtain a solution [

4]. However, numerical difficulties arise in the shooting method for lower temperature range, and special techniques are needed to overcome them [

5]. An alternate method is to apply Newton’s method to solve the non-linear TF equation. A discrete version of the resulting (linear second order) differential equation, obtained via the finite difference method (FDM), and the double sweep method provide an efficient algorithm, as the coefficient matrix is tri-diagonal [

15]. However, the second order derivative of the TF-function does not exist at the origin and is very large in its neighborhood where the FDM is not applicable. One of the aims of this paper is to develop a method with forth order accuracy to solve the linear equations which result from Newton’s method. Then, it is pointed out that Brachman’s differential equation [

16] is employable as it provides directly the thermal component of electron energy. Furthermore, with the use of very accurate rational function approximations of Fermi-Dirac integrals [

17], the present paper offers a simple algorithm that works in the entire scaled temperature-density plane.

The paper is organized as follows. The relevant formulas related to the TF model are collected in thomas-fermi-model, while the numerical scheme is detailed numerical-scheme. Analytical representations of thermodynamic functions, which include electron energy, pressure, ionization, Fermi energy and initial slope of TF-function, are provided and discussed in analytical-representation. Accuracy of these representations is demonstrated, in applications, via computation of electron-Hugoniot and the Hugoniot of Cu and comparison with experimental (or theoretical) data up to about 20.4 TPa pressure. Finally, summary provides a summary of the work.

2. Thomas-Fermi Model

The finite-temperature TF model follows from the Poisson equation for electrostatic potential in an atomic cell, where the electron density is given by the Fermi-Dirac distribution [

3]. In scaled variables, it yields a nonlinear second order differential equation [

4]

Here, the dimensionless radial co-ordinate

, where

R denotes the spherical cell radius. The TF-function

and dimensionless parameter

are defined as

where

is the electrostatic potential,

the Fermi energy,

Boltzmann’s constant and

T temperature. Note that

denotes the magnitude of electronic charge so that

is the electron potential energy. Remaining symbols are electron mass

and Planck’s constant

h. The Fermi-Dirac function of order

is given by

Accurate rational function approximations [

17] for these integrals (and their inverse functions) are available for

and

. The limiting condition that

must approach the nuclear potential

as

yields one boundary condition

. The other follows from the condition that the atomic sphere is electrically neutral, which implies that potential gradient

at

R. This fact, together with the choice of potential value

at

R (which is arbitrary) provides the condition

. Now, note that

which is also implicitly defined through the relation

, where

is number of free electrons at temperature

T and

the cell volume.

2.1. Thermodynamic Properties

Detailed derivations of all thermodynamic properties within the TF model are well known [

4]. For instance, electron pressure is given by

Only

is needed for computing

P. Alternatively, if

P is known,

and thereafter

can be obtained. Kinetic energy of electrons (per atom) needs

over the full interval, and is expressed in the integral

Similarly, the potential energy of electrons is given by

Note that the last three equations (

3 -

5) yield the virial theorem expressed as

. A partial integration in Eq.(

5) together with the TF equation and the relation

yields the alternate expression

Asymptotic forms of should be used near in evaluating these integrals. An alternate way to compute total energy of electrons (per atom) is the following.

The free energy

F and thereafter the entropy

S are obtained [

16] by integrating the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation

. Entropy so obtained is given by

where

and

are, respectively, the electron-electron and electron-nuclear components of potential energy

. Using the definition of

and Poisson equation for

V, it is readily found taht

, where

denotes the slope of TF function (with respect to x) at the origin [

15]. Use of this expression, together with the virial theorem, reduces Eq.(

6) to the expression

. Finally, the thermodynamic relation

yields Brachman’s differential equation for energy [

16,

18]

where the partial derivatives with

T, like

, are taken at constant volume. This first order differential equation can be integrated from a suitable starting value of

T. Note that only

, and not the full TF function

, is needed in Brachman’s equation, however, the differential equation needs to be integrated.

In the high temperature limit when electron density is uniform,

, and consequently,

and

. Fermi energy reduces to

in the same limit. This limiting form yields (see Eq.(

7)) the ideal gas limit

, as

becomes independent of

T in this limit. In the zero-temperature limit [

18], Eq.(

7) reduces to

, where

is the initial slope of (the zero-temperature) TF-function,

is the TF scaling length, and

the Bohr radius. Substituting

, and integrating the resulting equation from

T to

∞, the thermal energy

of electrons is obtained as

where

. It is necessary to integrate from

T to

∞ for the sake of numerical stability (see Eq.(

20)). Further, the zero-temperature terms are subtracted in

so that the integral does not diverge as

. Note that the expression for

is consistent with the high-temperature limits

and

for thermal pressure and energy of electrons in the cell. The term

, arising from

in this limit, cancels out. Very accurate numerical approximations for zero-temperature pressure

and slope

versus cell radius are available [

21,

22] (see analytical-representation).

3. Numerical Scheme

To develop a numerical method, the TF equation is converted to an integral equation. On integrating from

x to 1, and thereafter from 0 to

x, Eq.(

1) reduces to

where the kernel is

for

and

for

. The boundary conditions on

are incorporated in Eq.(

9). To employ Newton’s method, first the non-linear term is approximated using the expansion

, which follows from Taylor’s expansion of

around the function

. The recurrence relation

is also used. Substitution into Eq.(

9) yield linear equation

The known function

is

The integrals in these equations exist for

because

and

as

. Several numerical schemes exist [

19] for solving the linear Fredholm integral equations (FIE) as in Eq.(

10). Thereafter, a few iterations, together with the replacement

, provides the required solution, if Newton’s method converges.

In the Nyström’s method to solve FIE, which is employed to convert the FIE to a matrix equation [

20], the integral term is evaluated using a suitable quadrature. In the procedure adapted here,

(and also

) is approximated using piece-wise quadratic polynomials in the sub-intervals in [0, 1]. To this end, the interval [

, 1] is divided in to

N (even) sub-intervals defined with

(odd) mesh points

. This choice of

provides more mesh points near

where

varies more steeply. There are only

unknowns

to be determined as

is known. In the sub-interval

(

), the unknown function

is represented as as a quadratic polynomial

Substitution of

into Eq.(

10) yields Nyström’s interpolation formula

where the modified source function

is given by

The weight functions

(for

) are given by

An additional set of functions

are also introduced for expressing the source term

as

Note that the second sum (with

★ on lower limit) involving

is only over even values of

j. The last integral term is obtained using the approximation

. In all computations,

in

is approximated by the quadratic polynomial

. This polynomial passes through

and

and has the slope

at the origin. The slope at the origin given by

The first line follows by integrating Eq.(

1) over [0,1]. Latest available values of

and

are employed in computer implementation. Rigorously, a term proportional to

must be added in

near

to account for the divergence of

. However, this is not considered here since the dominant term contributing to the integral (in

) is

. All the integrals are readily evaluated using low order (say 6 or 8) Gauss quadrature. However, the asymptotic term

should be subtracted within the integral in Eq.(

18) (before applying Gauss quadrature formula) and its contribution

added separately. Similar technique may be used in obtaining

from Eq.(

17) for better accuracy. The approximation leading to Eq.(

13) is the same as in obtaining Simpson’s integration formula and hence the local truncation error is proportional to

. The collocation rule in Nyström’s method amounts to enforcing Eq.(

13) at the discrete set of values

, which yields a matrix equation

of order

for the vector

. The coefficient matrix is

. The components

and those of of the vectors

and

are

and

, respectively. Elements in a particular column of the lower triangular part of

are the same. The upper triangular part can be written as

with

sharing the same property.

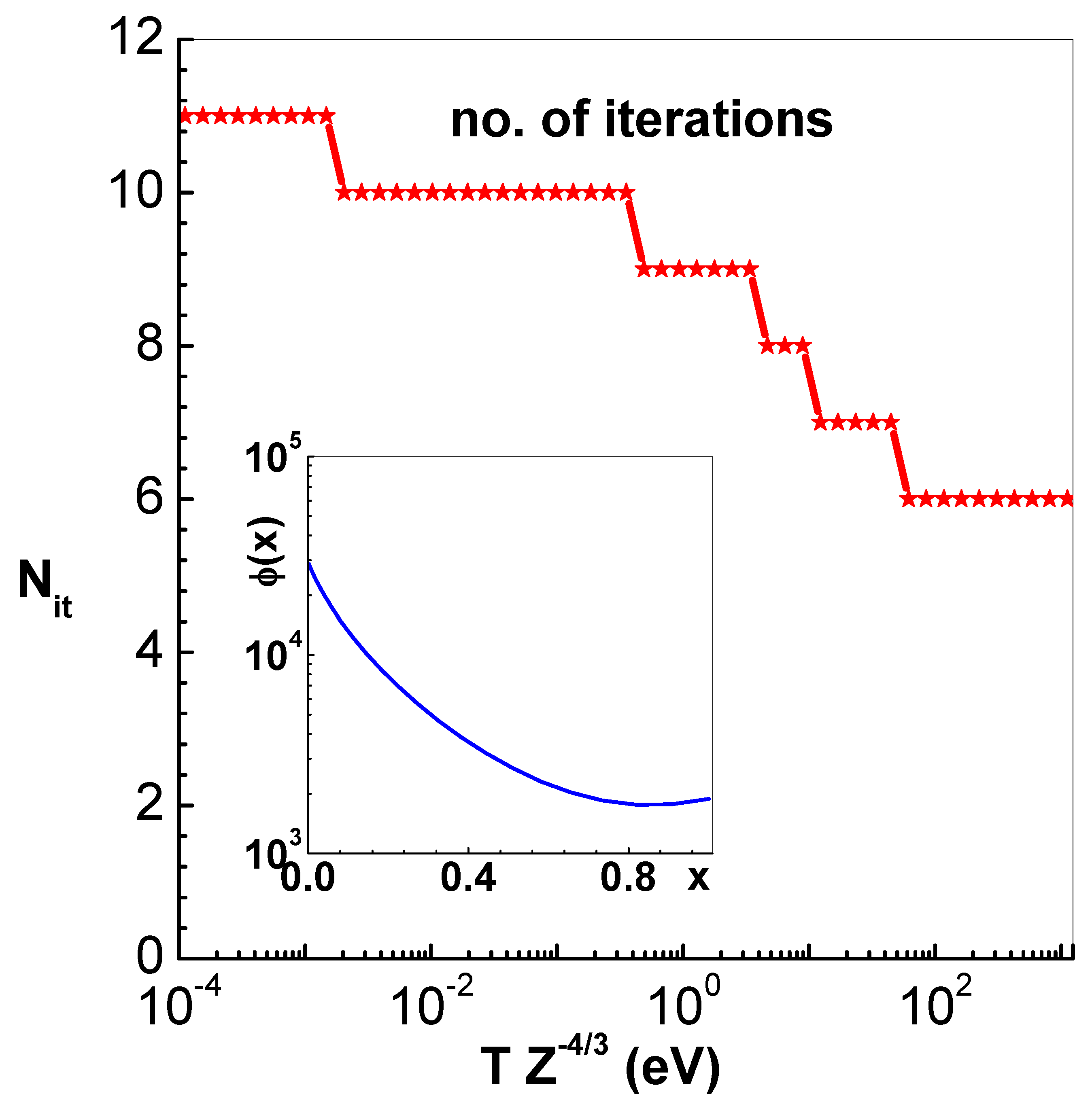

The number of Newton’s iterations

needed for convergence to a specified accuracy is indeed depended on the starting guess solution. For illustration,

Figure 1 shows

needed versus

to reduce the Euclidean norm between successive iterates to

. The starting guess solution for each temperature corresponds to uniform electron density and

are the number of sub-intervals used. The scaled cell radius in this case is

, however, similar results are obtained for expanded as well as compressed configurations. Even for very low temperatures

eV, Newton’s method converges in about 10 iterations to the specified accuracy. The inset in this figure is the converged profile

for reduced temperature

eV, which justify piece-wise quadratic polynomials used in the method. It is also found that the spatial profile of

converges with about 10 sub-intervals

N.

3.1. Thermodynamic Quantities

All the properties described earlier (see thermodynamic-properties) is computed using the converged solution vector

. For instance, pressure is obtained directly from Eq.(

3) using the converged value of

. Next, the kinetic energy is obtained as

Note that the second sum is only over even values of

j. The contribution of the asymptotic term in

to the first integral should be accounted as explained earlier in the case of

. Further,

follows from the virial theorem. Alternatively, the thermal energy

at temperature

is obtained directly via a recursion relation

This follows directly from Eq.(

8), and the dependence of

and

on cell volume

is suppressed. For sufficiently large

n, the starting value of thermal energy

. An interpolation function of

is first constructed from its tabulation versus

T and then used in this relation. The last integral in Eq.(

20) is computed with three-point Simpson’s rule. The slope

is given by Eq.(

18) (also see analytical-representation).

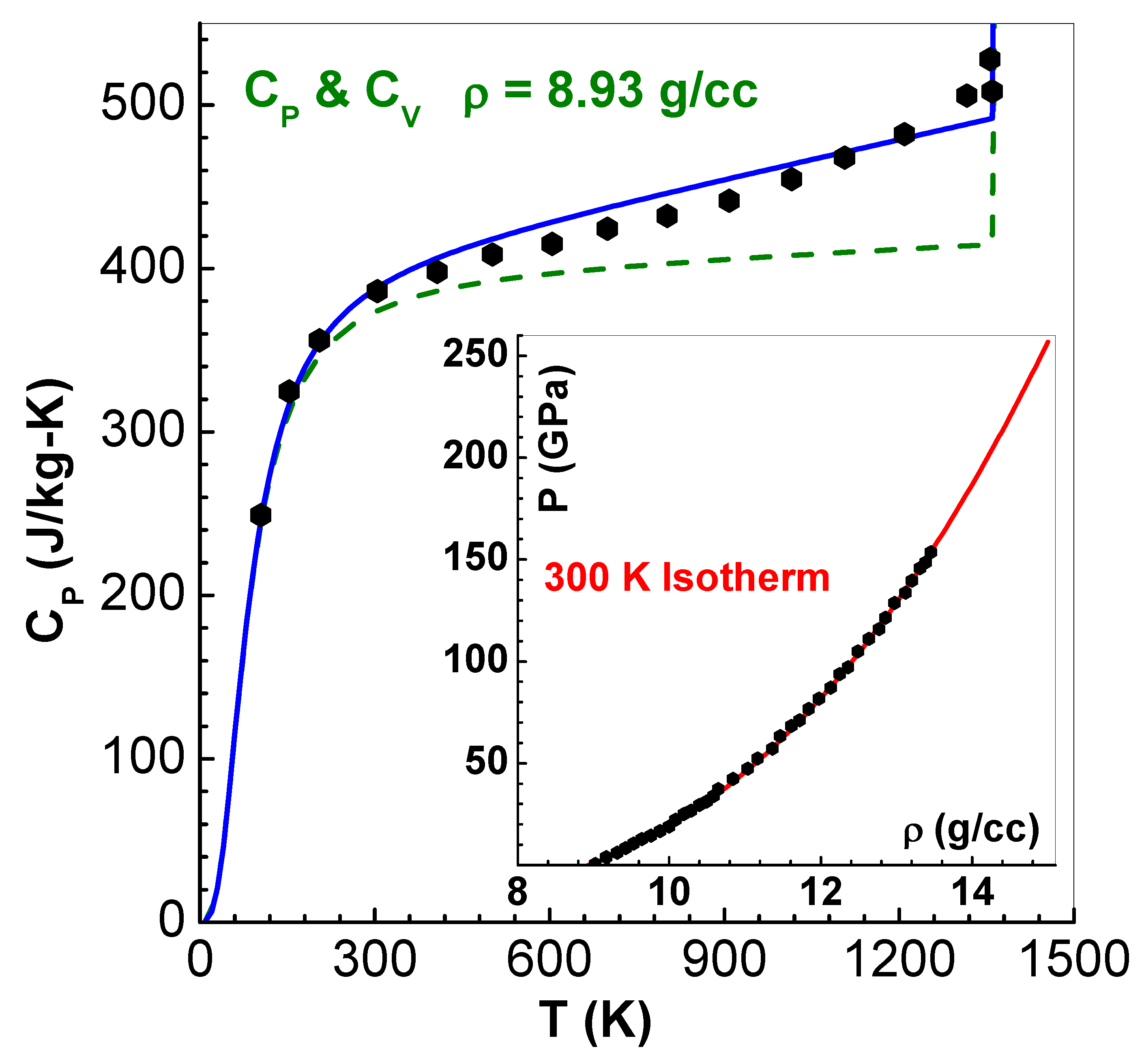

4. Analytical Representations

Using the results of extensive calculations, covering the temperature range (eV) and cell radius range (Ao), analytical representations for thermal energy , thermal pressure , thermal ionization , Fermi energy and initial slope of TF-function are derived. As explained earlier, while ionization provides Fermi energy, the initial slope gives entropy and free energy.

1. Thermal Energy

Thermal energy is represented in the form

The factor

is the scale parameter for energy in TF-model and

(eV) is the scaled temperature. The parameters

(for

) are functions of the scaled cell radius

(A

o). The expression for

is proportional to the asymptotic forms

and

in the limits

and

, respectively. Therefore, it is evident that

. The parameter

is already determined by Gilvarry [

21,

22] using solutions of temperature-perturbed TF equation. It’s fit as a function of

is

Here,

is the pressure at zero-temperature and

,

and

. The factor

arises because

should be proportional to

. The dimensionless parameter

is proportional scaled cell-radius as

(

the Bohr radius) and

are constants. The zero-temperature pressure

, the boundary value of zero-temperature TF-function

and the parameters

and

are fitted functions of

given by

The remaining parameters

and

are fitted to the rational expressions

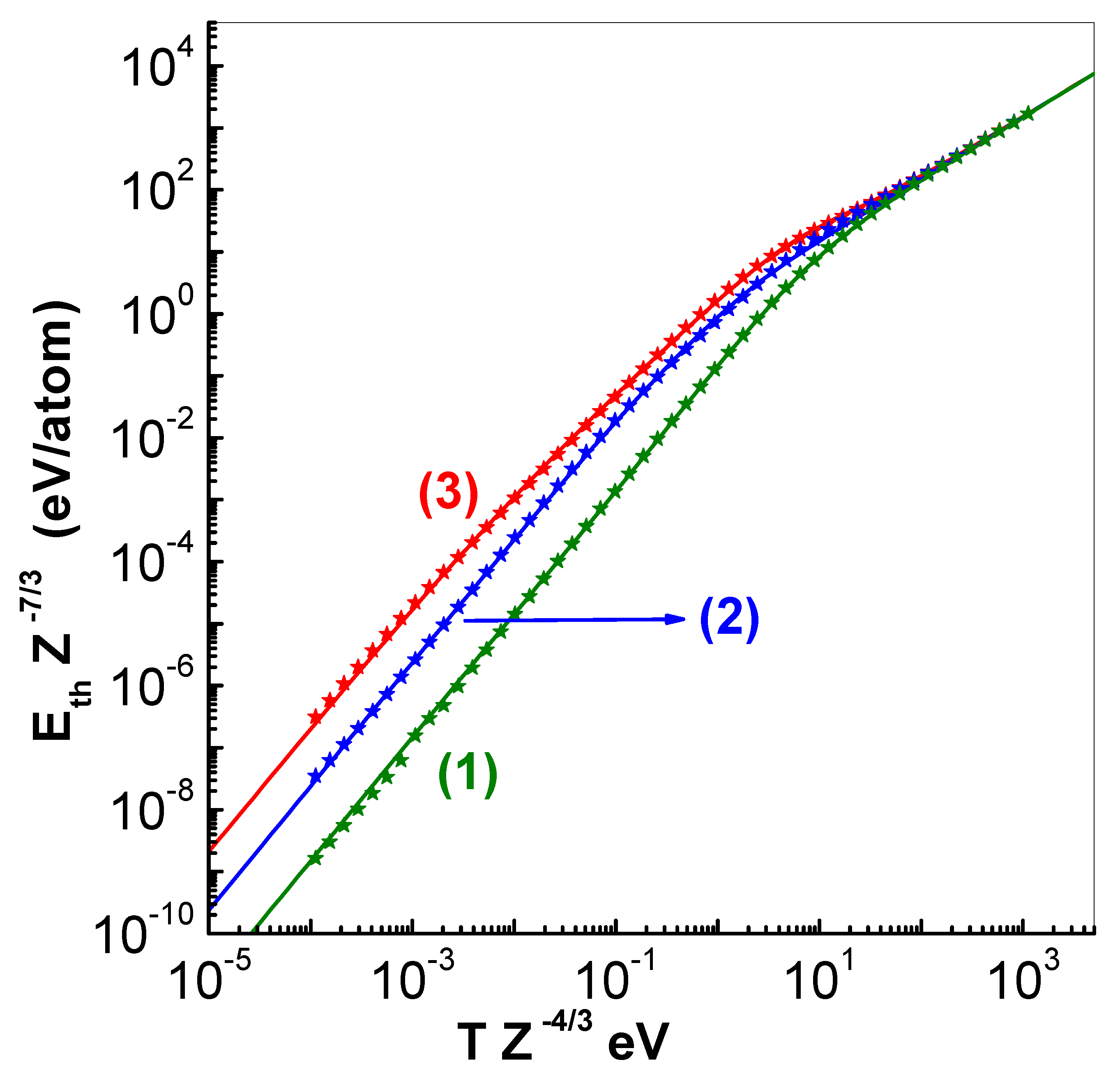

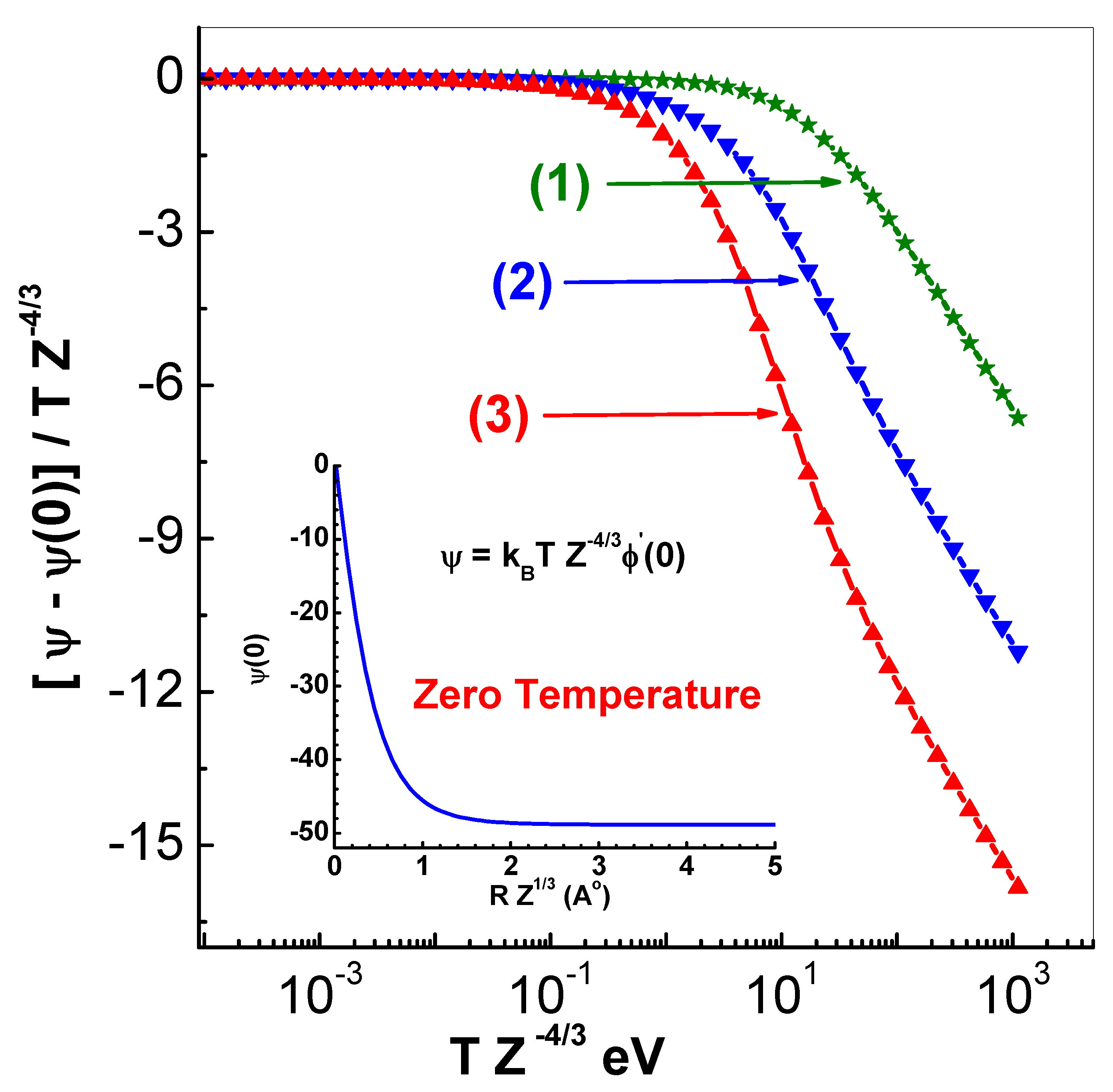

As application of these formulas, plots of scaled energy

(eV/atom) versus scaled temperature

(eV) are shown in

Figure 2 for three values of scaled cell radius

. Here, the symbols are numerical values and lines represent analytical representations. It is important to note that all the three curves merge together at high temperatures thereby indicating approach to ideal gas limit.

2. Thermal Pressure

The analytical representation for thermal pressure is chosen as

Here the factor

is the scale parameter for pressure. Now, all the parameters

(

) are functions of the scaled cell radius

. Since the expression for

is proportional to the asymptotic form

in the limit

, the parameter

. The parameter

(already determined by Gilvarry [

21,

22] using the temperature-perturbed TF equation) is given by

The factor

arises in this expression because

should be proportional to

. Other quantities

,

and

are already given above. The parameters

and

are represented as

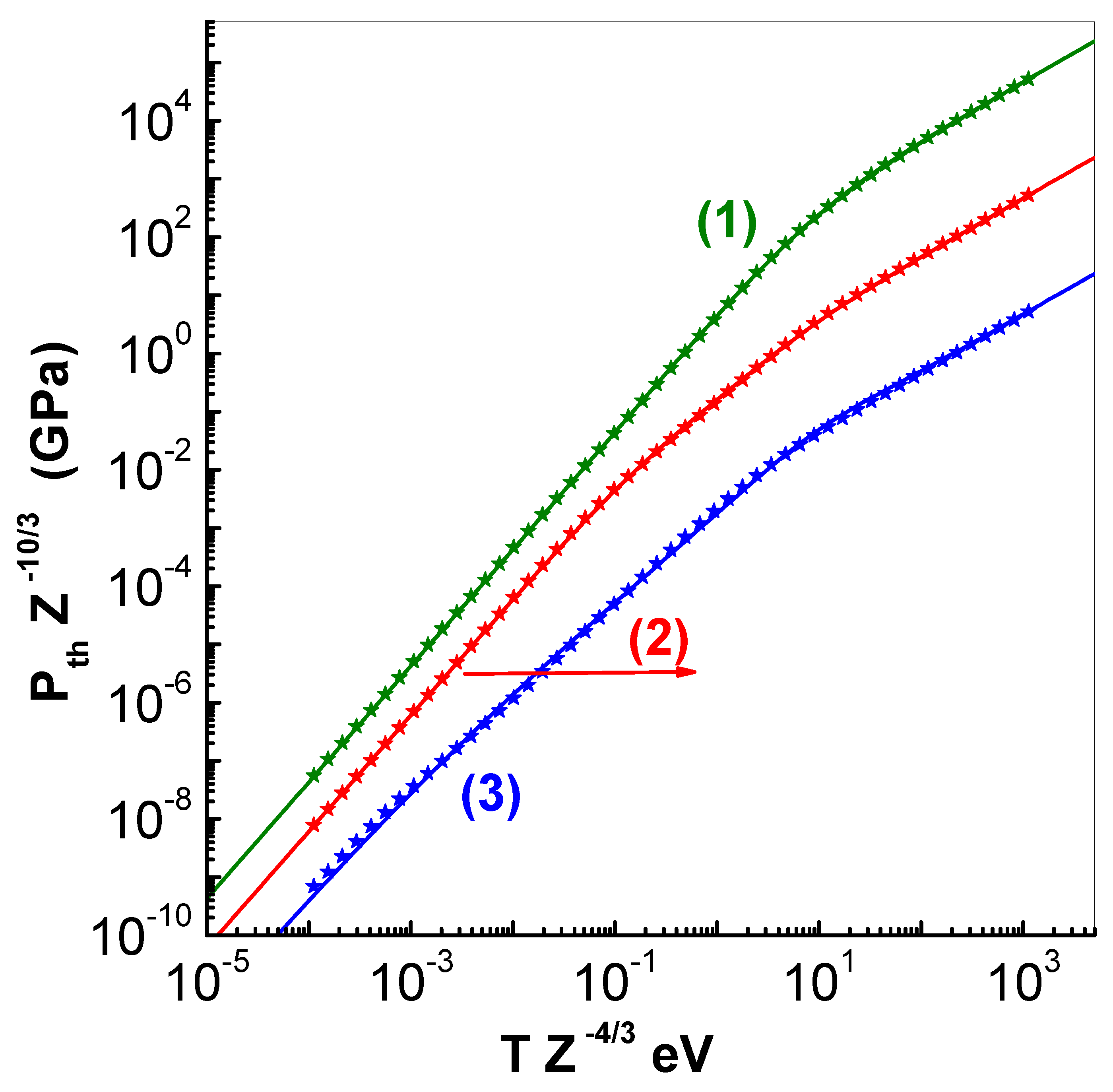

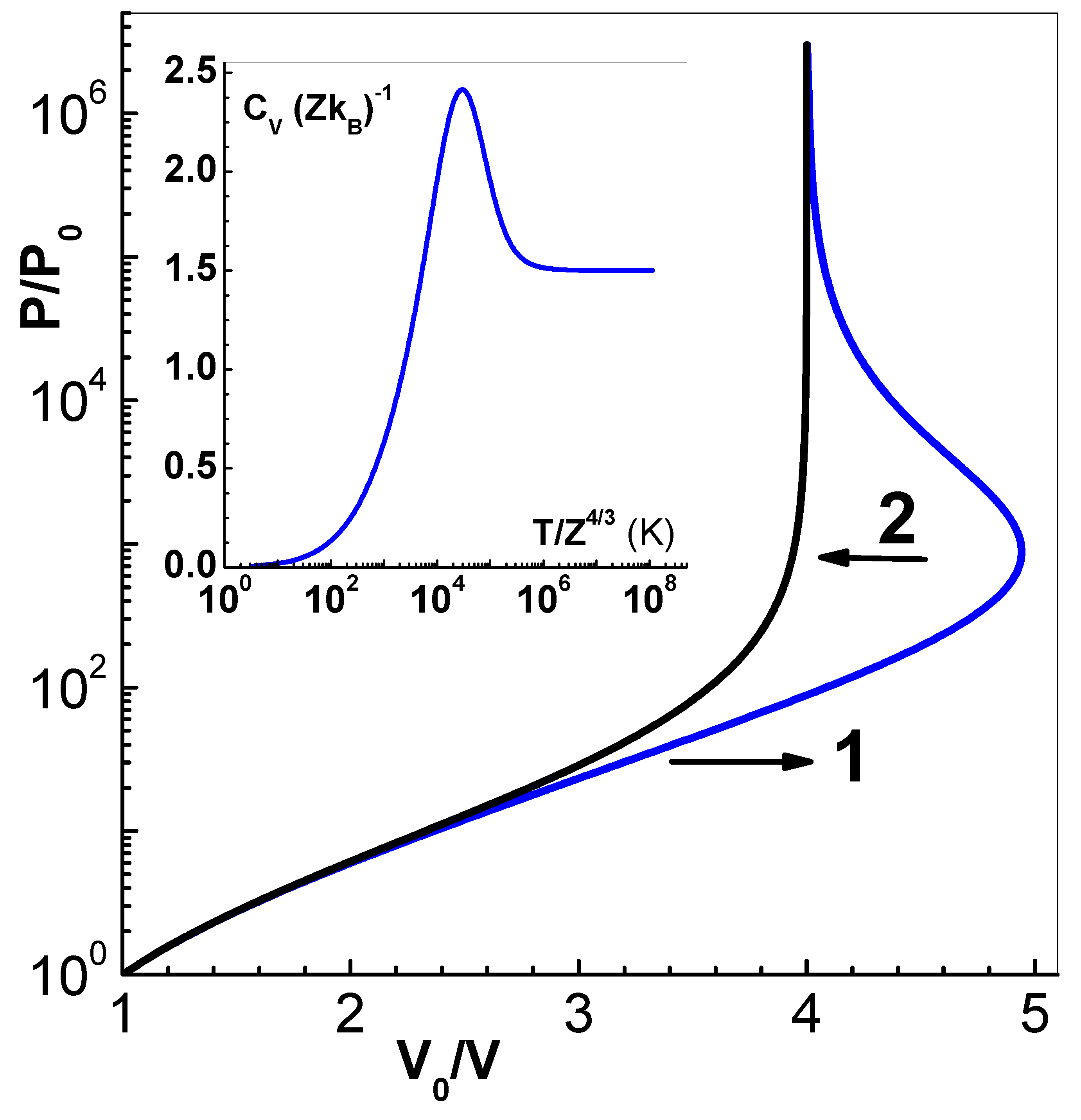

Plots of

(GPa) versus

(eV) are shown in

Figure 3 for same values of scaled cell radius

. Here also the symbols denote numerical values while the lines depict analytical representations. The linear variation at high temperature in all the three curves indicates approach to ideal gas limit. Unlike the fits available in the literature [

11,

12], the expressions in Eq.(

21) and

22 have the correct dependence on cell radius

, and are applicable in compressed as well as expanded volume regions (see applications).

4. Thermal Ionization

As the numerical procedure gives

, thermal ionization is directly given in terms of

(see thomas-fermi-model). A numerical fit to

as a function of density and temperature is given by More [

23]. However, it is found that the relative error in this formula is as much as 30 percent for low temperature and expanded volume states. The data generated now is expressed in rational function representation as

This form approaches approaches

Z as

, and the parameter

provides ionization at zero-temperature. Theoretically, the value of

in the limit

should approach 1; the numerical value obtained

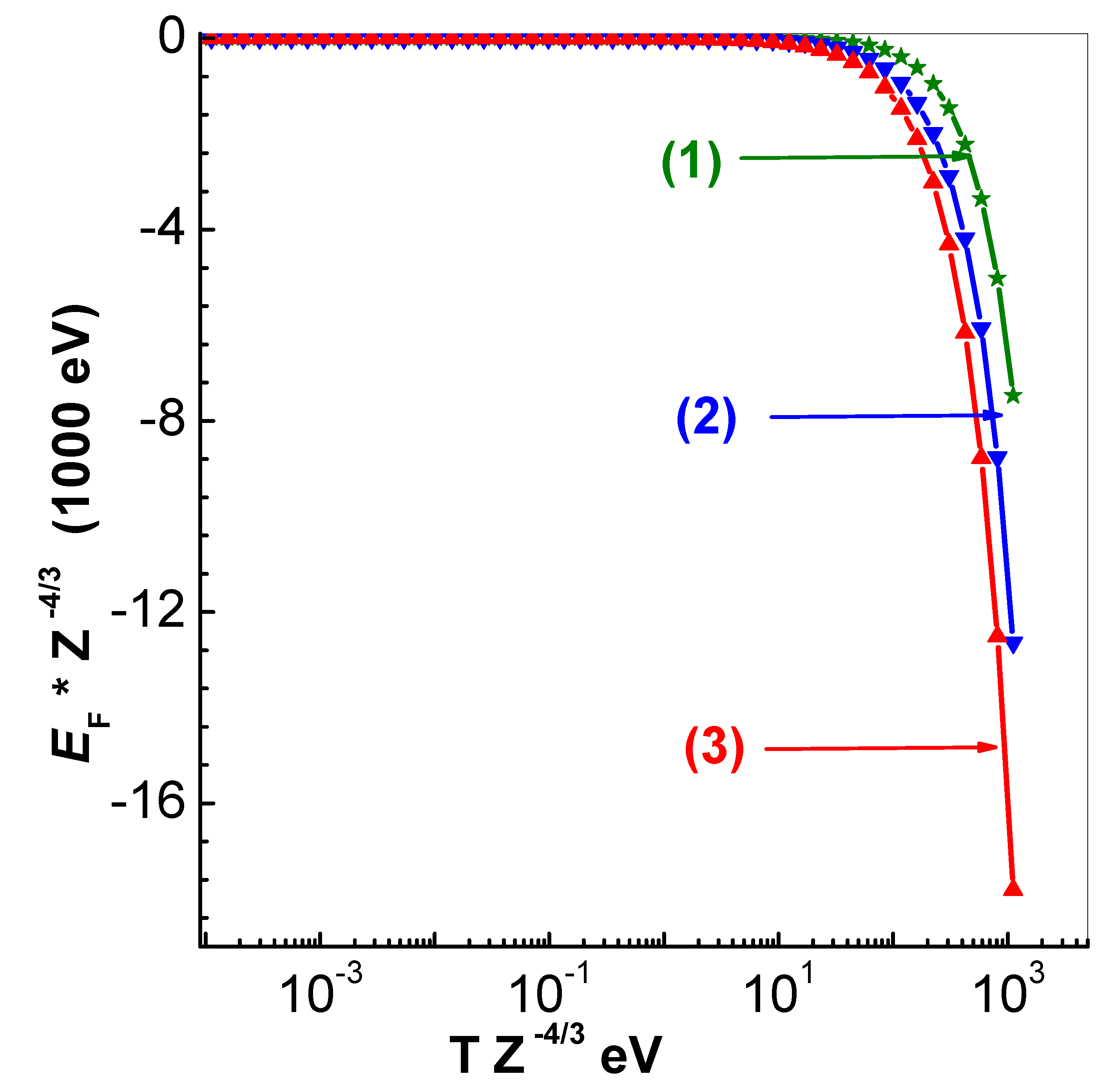

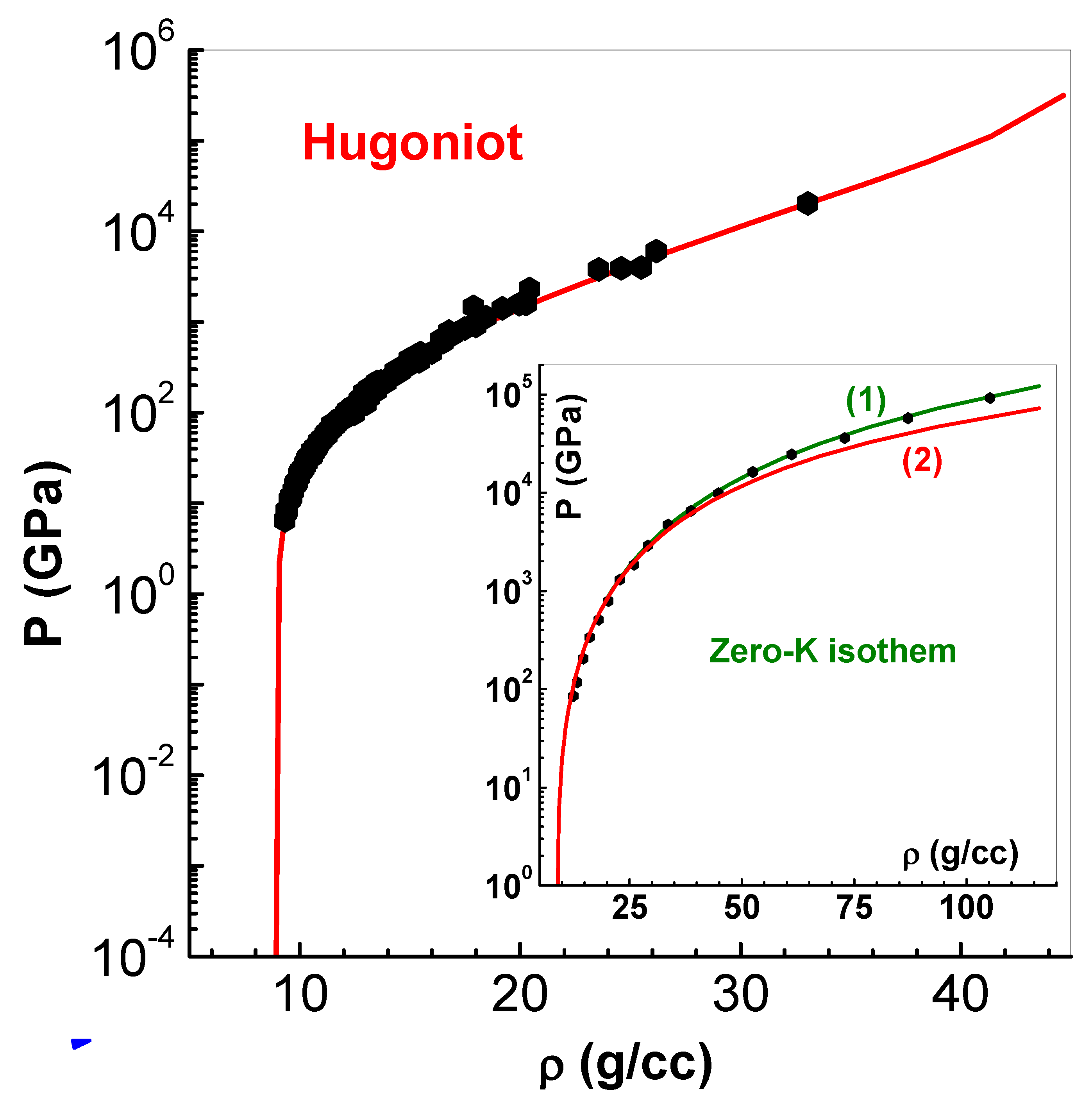

is close to this theoretical limit. Plots of

versus

are shown in

Figure 4 for same values (0.9348, 4.339 and 20.14

) of scaled cell radius

considered earlier. Again, symbols are numerical values and lines analytical representations. The present expression has about

percent accuracy in the entire plane.

Dependence of all the five parameters

on

is obtained as

3. Fermi Energy

Although the solution procedure of TF model directly gives

, it can also be obtained in terms of ionization using the inverse of

integral (see thomas-fermi-model). Since very accurate representation of this inverse function is available [

17], it is unnecessary to represent

directly. However, for the sake of completeness, scaled values

versus scaled temperature

(eV) are shown in

Figure 5 for the three values (0.9348, 4.339 and 20.14

) of scaled radius

.

4. Initial Slope

The initial slope of the Thomas-Fermi function

is needed in calculating entropy (and free energy) as it is defined by

. To this end, the parameter

is introduced so that entropy is expressed in terms of thermal quantities as

. The representation chosen

is

Here,

is the limiting form of

corresponding to uniform distribution of electrons. This follows readily from

. Further,

is the limiting value of

as

. This separation is useful as

as

. The representation for

, where

is computed using ionization

, is given by

where

and

are in eV and A

o, respectively. The parameters

(

) and the zero-temperature slope

are found to be

The variation of

versus

is shown in

Figure 6 for three different values (0.9348, 4.339 and 20.14

) of

. The chosen functions represent the data accurately. For the sake of completeness, the dependence of

versus

is shown in the inset in this figure.

The definition of

and Eq.(

8) shows that

is the same as

. The fit for

(initial slope of zero-temperature TF-function) provided by Gilvarry [

21,

22] is

with

. Note that

is the slope for isolated atom. This yields

as the energy of the isolated atom at zero-temperature. Numerical results show that the two representations for

agree well.