1. Introduction

The Collatz conjecture proposed by Lothar Collatz in 1937 is considered one of the most important conjectures in pure mathematics, its simple construction but yet deep connection with prime numbers make this conjecture remarkably important. The statement of the problem is very simple, take any natural number n, if then divide it by 2 to get , if then multiply it by 4 then add one, to arrive at . The conjecture states that upon repetitive iteration of this process, we will always reach a tree of .

Multiple attempts were conducted to tackle the conjecture, one of which by Schwob et al. [

1], where the authors introduce some novel theorems and algorithms that explore possible relationships and properties between the natural numbers, their peak values, and the conjecture. Additionally, they analysed the number of Collatz iterations for the chosen number

n to reach 1 or such that

. On the other hand, W. Ren [

2] attempted a new approach to solving the conjecture, where he proposed a revised version of the conjecture referred to as (RCC). It states that: any natural number

n will return to an integer that is less than

n after a specific number of Collatz iterations defined by the function

as follows:

If the RCC is to be proven, then the proof of Collatz conjecture follows naturally. The author in fact proved that half of the natural numbers follow the RCC, but the other half remain unsolved.

Another interesting result is by Terence Tao in [

3], where the problem is rephrased in terms of a Collatz map defined as

For any

, let

denote the minimal element of the Collatz orbit, such that

We can now write the infamous Collatz conjecture as: for all . Tao showed that most of the Collatz map orbits attain almost bounded values.

The Conjecture still now remains unsolved, but several numerical verifications were conducted, the most recent of which is [

4], that verified the conjecture for all

.

Despite numerous attempts, the author believes that the present article presents new and optimistic ways to consider the conjecture, ultimately providing proof. Even if it does not achieve this goal, the mathematical results obtained answer many open questions about the conjecture and may be of interest in other applications, such as cryptography and information theory.

2. Overview on the conjecture

The foundation of our proof lies in demonstrating that every number ultimately reduces to a smaller value. Given the established adherence of even numbers to this principle, our focus shifts to the examination of odd numbers. Should it be confirmed that odd numbers similarly consistently reduce to lower values and do not succumb to alternative loops other than the 4-2-1 sequence, the conjecture stands validated for all numbers.

We define the function

as follows:

If

x is odd, then

is an even number since:

Thus, the conjecture can be simplified to:

Now, there are two possibilities for the result of :

If the result is even, it will become .

If the result is odd, then another operation will be applied.

The same possibilities are applied again for the result until we reach or any other conditions that would disprove the conjecture.

Based on that, an odd number will go through a sequence of operations until it reaches the first even number. From there, it will be divided by a sequence of 2 until it reaches another odd number, and the process will repeat again and again.

3. Mixture of geometric and arithmetic sequence

Assume the following sequence of operations:

The sequence follows this pattern:

If

and

, it represents the Collatz conjecture

. Starting from

, we can generate the sequence:

4. Deriving the General Formula for

To find a general formula for , where n is the number of steps, we break it into two parts:

1. First part: (from the previous sequence).

2. Second part: The sum of a geometric sequence with the terms

, which can be summed as:

as stated in

[

5].

Thus, the formula for

is:

Substitute

and

into the formula:

Simplification

Since

n represents the number of steps needed to reach the first even number, we can deduce the following:

Since

x is odd,

must be even, making

odd. As the result is an integer,

must be divisible by

, so we can express

x as:

Using this approach, we can simplify

to:

if b is even, then this result will be odd and more steps are needed to reach an even number, so b must be odd Reaching the following:

example

Table 1.

Example Results for

Table 1.

Example Results for

| Number |

b |

n |

Result () |

| 5 |

3 |

1 |

8 |

| 223 |

7 |

5 |

1700 |

| 99 |

25 |

2 |

224 |

| 97 |

49 |

1 |

146 |

After reaching the result of , the number is even and will be divided by 2 for z times until we reach the first odd number called y.

(eq 3)

Since

y is odd, we can write it in a similar formula to

x as follows:

(eq 4)

x will undergo n Collatz operations until it reaches an even number, which will then be divided by 2 for z times. The result is a number y, which will lead to Collatz operations, and then it will be divided by times of 2, reaching another odd number, and so on.

If y is smaller than x, then the number x obeys the Collatz conjecture, as it leads to a number smaller than itself.

Odd numbers can be classified based on the number of steps n they need to reach the first even number. The classification can be as follows:

Class 1: Odd numbers that reach an even number in one step.

Class 2: Odd numbers that take two steps to reach an even number.

Class 3: Odd numbers that take three steps to reach an even number.

Class k: Odd numbers that require k steps to reach an even number, and so on.

5. Analysis of Conditions for the Collatz Conjecture in Large Numbers

We are interested in the case where

. This inequality becomes:

Given that numbers smaller than

have already been verified by computational tests to satisfy the Collatz conjecture, our focus shifts to larger numbers. For very large values, the subtraction of 1 becomes negligible, so we can simplify the inequality by removing the "-1" term:

This simplifies further to:

Taking the logarithm of both sides gives:

Where and .

(eq 5)

This condition is satisfied when , meaning that for , all numbers in this group meet the requirements of the Collatz conjecture with a minimum value of or higher.

6. Collection of Operations

Based on the results, we conclude that any number

undergoes a series of operations, where it first goes through

steps of the form

, followed by

steps of division by 2, resulting in

. Similarly,

will undergo

Collatz steps and

divisions by 2, leading to

, and so on:

For large numbers, the subtraction of 1 can be ignored since it has a minimal effect.

We can express the next step in the sequence as:

In general, this can be written as:

If

reaches a smaller value, the following condition must be met:

(eq 6)

Here, is the total number of divisions by 2, and is the total number of Collatz steps. The difference is called the "barrier." If the barrier is less than zero, it means has decreased. If the barrier is zero, has likely reached the same value or one close to it. Since we ignore the subtraction of 1, there may be a slight loss in accuracy.

If reaches itself, a loop is formed. If not, will either decrease or increase.

7. Correction Factors and Barrier Calculation in Recursive Operations

To maintain accuracy after each operation, we can multiply by a factor f to correct the result.

If we express the value of

as

, the accurate result after each operation using the formula

is:

Thus, we can correct the process by applying a correction factor to each step:

If we calculate the correction factor

f based on the total number of operations (denoted as len), we can express it as:

Since

, we can rewrite it as:

Note on the Correction Factor:

Since we are dealing with large number factors, the correction factors will each be close to 1.

As a result, will also be close to 1, making approach 0. This means that the effect of the correction factor in the barrier expression becomes negligible.

Next, we modify the barrier expression:

(eq 7)

Thus, the final barrier expression becomes:

Since

is negligible (approaching 0), we can omit it in practical calculations, simplifying the barrier to:

(eq 8)

8. Derivation of the Formula for y and b Values

Let us consider the expression for y in the form . From this, we can derive the following relationship:

If

, then we can equate:

Solving for

, we obtain:

Next, we investigate the change in

b that results in the same value of

z for a fixed

n. The updated value of

b that satisfies this condition is given by:

where

J is a positive integer.

Substituting into the expression for

y, we get:

Thus, the new value of

y, denoted

, is:

It is important to note that if J is an odd integer, the resulting value will be divisible by 2 an additional time, effectively reducing the result for or more steps. Consequently, to preserve the same value of z, J must be an even integer.

In simpler terms, a number divisible by 2 for z or more times will repeat itself every steps. If the step size is odd (i.e., half of the total steps), the number reaches the same z-value. Assuming that n is constant, we can generalize that the number will repeat itself every steps, where j is an integer.

The new value of

x can be expressed as:

which simplifies to:

(eq 9)

Example:

To reach the next value of where remains the same, repeats itself every steps.

Table 2.

Example of repeating N,Z

Table 2.

Example of repeating N,Z

| Number |

N |

z |

Next Number (same N and z) |

| 5 |

1 |

3 |

37 |

| 223 |

5 |

2 |

479 |

| 99 |

2 |

5 |

355 |

| 97 |

1 |

1 |

105 |

For the calculation of

, we have:

which simplifies to:

To reach the same value of

z,

must be shifted by:

where

j is an even number, Meanwhile, the original value of

x is shifted by:

Performing the same steps, this result could be generalized to be valid for any recursive steps of

n,

z

Thus, from the perspective of x, this combination occurs every steps, which can be treated as calculating a frequency. For instance, if , the number will occur every 4 steps. Since we are dealing with odd numbers, this corresponds to half of all odd numbers. Simplifying further, if , then the frequency will be 0.5. All other values between these frequencies can be treated similarly, by ignoring the 2-factor.

It is crucial to note that this approach proves that based on the frequency with which the number x appears on the number line, the values of n, , ,..., z, , ,... etc., can be analyzed.

By flipping the frequency of the number, we can determine the percentage of how often it appears on the number line (for both even and odd numbers). Since

j is always even, the percentage of occurrence is given by:

Since this percentage reflects how frequently the number occurs on the number line (including both even and odd numbers), we divide it by 0.5 to determine how much of the percentage occupies the odd number space:

(eq 10)

Alternatively, this can be expressed as:

(eq 11)

By this method, we begin with a value of x and calculate its occurrence rate based on the combination of factors.

Keep in mind the important barrier: , as it is the key to understanding how the value of x evolves over time. Although the first value may appear to be a random combination, all other values for different combinations exist that could be achieved if we put j as an odd number.

9. Existence of Every Unique Sequence

The following algorithm can be employed to identify the smallest number that generates a given sequence of Collatz operations, namely and .

Identify the sequence. For example, consider the sequence: .

Numbers at even positions in the sequence represent increments, while numbers at odd positions represent decrements.

Generate an initial number T in the form , where is the first number in the sequence.

Declare a variable V and initialize it with the value .

Declare another variable L and initialize it with the value .

Loop through the sequence, starting from the second element.

If the current element corresponds to a decrement, repeatedly divide L by 2 until the first odd number is encountered. Check if the length of this division sequence equals the value of the current element. If so, update V to be the last value of L and proceed to the next element in the sequence.

If the current element corresponds to an increment, repeatedly apply the operation to L until the first even number is encountered. Check if the number of operations performed equals the value of the current element. If so, update V to be equal to L and proceed to the next element in the sequence.

-

If the number of operations performed does not match the current element, the following modification process is applied:

- -

Declare a variable R, where for increments, , and for decrements, .

- -

Declare , where N is the number of confirmed correct increments.

- -

Declare , where E is the current element value.

- -

Find f, the smallest value greater than R that is divisible by E.

- -

Declare C, where .

- -

Declare and .

- -

Find the modular inverse of B, denoted , with respect to A.

- -

Calculate D, where .

- -

If , set .

- -

Update T using the formula , where S is the sum of all confirmed elements.

- -

Update V using . Set L equal to V.

- -

Repeat the modification process starting from the last unconfirmed element.

The process terminates when all elements in the sequence are confirmed. The final value of T is returned.

Note: An element is considered confirmed if it appears in the sequence generated by

T in the correct order.[

10]

Since

A and

B are co-prime, there exists a valid solution for calculating the modular inverse

.

A python code is available doing the previous algorithm [11]

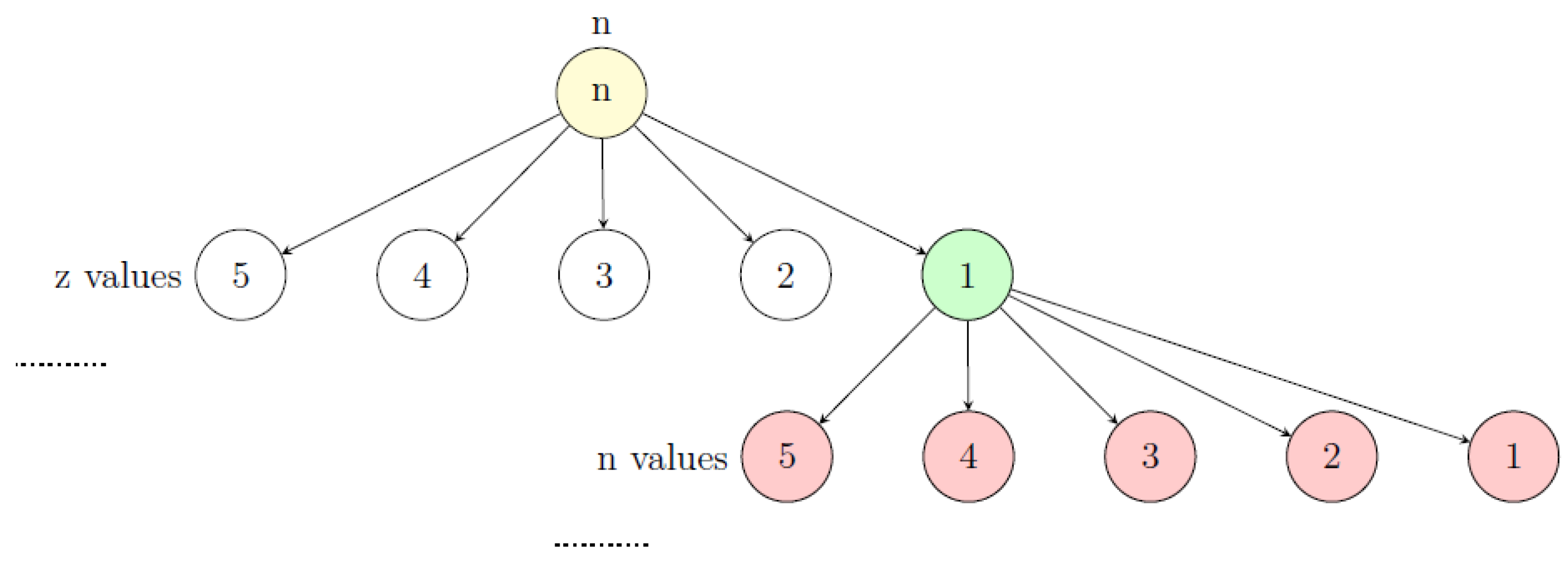

10. Collatz Tree

We can build a tree to count how many numbers satisfy the Collatz conjecture. To do this, we check all possible values of n and z, exploring their possibilities until the barrier becomes zero or negative. When this happens, we return to the starting point in the tree and add the found possibility to the percentage of numbers that satisfy the conjecture, as they lead to smaller numbers.

We start with an initial barrier, where and . The starting percentage of numbers that lead to smaller numbers is .

We then branch out with all possible values of z. Each value of z has a frequency of . After exploring each z, we check the new value of the barrier. If the barrier is less than or equal to zero, we stop and count the branch as leading to a smaller number. We add the frequency of that branch, , to P.

If the barrier is still positive, we explore each z that didn’t meet the condition and consider all possible values of n. Each value of n has a frequency of . The total frequency for each branch is . We then continue exploring all possible z-values for each branch, checking the barrier again and adding the frequency to P if it meets the condition.

Note: The frequency term or represents how frequently a certain pattern occurs in the process. The smaller the exponent, the more frequently that particular pattern appears. This reflects the likelihood of reaching a specific state or condition as we explore different values in the tree.

Figure 1.

Visualizing Collatz tree.

Figure 1.

Visualizing Collatz tree.

Since both n and z have the same frequency of occurrence, the likelihood of reducing the barrier increases as we progress deeper into the tree. More values are added to the percentage as we go further. This happens because in the barrier expression , the term is multiplied by , which is approximately 0.58 (less than 1), while is multiplied by -1. As we explore all possible patterns, the total value of the barrier (accounting for different patterns) becomes smaller as we go deeper into the tree. This means that as the depth approaches infinity.

This sequence exhibits a behavior analogous to that of prime numbers.

Just as prime numbers define the non-prime status of other numbers through a specific repeating frequency, a similar phenomenon occurs here, where decreasing patterns recur at regular intervals, effectively covering other numbers as part of the decreasing pattern set.

In the case of prime numbers, as we extend towards infinity, they progressively cover all natural numbers as non-primes, since the deeper we analyze the distribution of primes, the higher the percentage of numbers identified as composite.

Similarly, the Collatz tree follows a similar behavior, where the branching structure systematically encompasses an increasing number of values, reinforcing its coverage as depth increases. [

8]

This approach demonstrates that proving the impossibility of infinite increments results in a recursive process of unbounded steps.

As the proof expands, it progressively encompasses more numbers, reinforcing its validity through an increasingly extensive coverage.

Computational simulations of these steps up to a given depth reveal that as the depth increases, the value of p approaches 1.

However, for groups where , reaching an exact value of 1 remains unattainable within a fixed computational depth.

Nevertheless, the value continues to asymptotically approach 1 with increasing depth.

Function representing the previous Collatz tree:

11. Impossible increment as a probability game

When estimating the frequency of increasing or decreasing across all values of n and all values of z for a single step, it is observed that the frequency of an increase in the barrier is approximately 28.7%, while the frequency of a decrease in the barrier is approximately 71.3%.

This result can be obtained through both manual calculations and computational simulations.

The Collatz conjecture can be interpreted as a probability game. While an increment might occur at the beginning, achieving an infinite increment requires playing the game indefinitely. In the long run, the frequency of a 28.7% increment and a 71.3% decrement dominate. This suggests that infinite increments are impossible, as the process will eventually halt when the value drops below the initial number.[

9]

The exact value of increasing or decreasing frequency is not very important at this point, because what matters most is that the frequency of decreasing is higher than the frequency of increasing.

Following either approach will eventually lead to a deterministic conclusion that infinite increment patterns do not exist, due to the recursively increasing frequency of decrement patterns.

12. Possibility of Other Loops

Consider the equation:

For a loop to exist, the barrier must equal zero. Since the logarithmic function yields an irrational number and both

n and

z are integers, the equation reaches zero under specific conditions. The factor in question is close to 1, and since

, the impact of the logarithmic term is minimal. Consequently, the possibility of achieving a zero barrier is extremely unlikely.

Through brute-force simulations, we specifically searched for a sum of n values where multiplying by the logarithm of produces a number that is nearly an integer. This number could potentially be tuned to an integer by small adjustments to the factor . However, no instance was found within the range from 1 to 10 billion where this condition held for more than 9 decimal places.

Even if such a value was found, another condition must be met: the sum of z values, , must equal the product of the sum of n values, , multiplied by the factor. This adds an additional layer of complexity, making it even harder to satisfy both conditions simultaneously. Therefore, achieving a zero barrier would require a very large sequence. As previously discussed, the frequency of such sequences is inversely related to their length, meaning that very long sequences are rare at smaller numbers. Moreover, if such sequences do occur at larger numbers, the factor would approach 1, making it even more challenging to find an integer solution.

These findings indicate that the likelihood of achieving the necessary conditions to reach a zero barrier is exceptionally small.

.

While the occurrence of such sequences might be frequent in some contexts, predicting the first appearance of such a sequence remains highly challenging. Therefore, although large sequences are less common at smaller numbers, there is no guarantee that they cannot exist.

As such, while this part of the conjecture has not been definitively proven, we believe the evidence strongly suggests that no loops other than the 4-2-1 loop are likely to occur.

13. Similar conjectures

Based on the established rules, it is possible to identify similar sequences, provided that the following conditions are met:

All potential sequence combinations must be represented.

Each unique sequence must exhibit a repetitive pattern with a fixed frequency of occurrence.

The frequency of decreasing values must surpass the frequency of increasing values.

Under these conditions, infinite growth becomes impossible, and the probability of discovering loops at relatively high values is extremely low.

As an example, consider the function:

where

G is an odd integer constant.

This reasoning leads to the conclusion that an infinite number of Conjectures, exhibiting behavior analogous to the Collatz conjecture, exist, but with differing arrangements of patterns and loops.

Another example:

where G is a value between 1,2 the value is chosen to make the result devisable by 3 This is a different conjecture where the barrier contains

instead of

, this means that in general this conjecture has more smaller patterns than the Collatz conjecture due to smaller value for the log.

This is the only way to have a similar behavior using values other than 3 and 2, which is by setting a changeable G, which explains why numbers 3,2 are very unique and useful to make the conjecture work correctly

14. Collatz Conjecture in Cryptography

The Collatz conjecture, though primarily studied in number theory, presents intriguing possibilities in the field of cryptography. If we consider the sequence of operations in a Collatz iteration—multiplying by 3 and adding 1 (followed by division by 2) as an "up" step and simple division by 2 as a "down" step—we can represent each transformation as a binary sequence.

For a given number x, if the operation applied is , we denote it as a binary ’1’. If the operation applied is , we denote it as a binary ’0’. This way, any number’s Collatz trajectory can be uniquely mapped to a binary string. Since every natural number produces a different sequence of ups and downs before reaching the cycle , this provides a form of encoding.

Cryptographic Potential

1. Pattern uniqueness: Since every number follows a distinct Collatz sequence before converging, we can use these sequences as cryptographic keys or one-way hash functions.

2. Deterministic Yet Unpredictable: While the sequence follows strict mathematical rules, predicting the steps backward (given only a binary sequence) is difficult without knowing the starting number. This could make it useful for encoding messages.

3. Controlled Variability: By manipulating how long a sequence runs before truncation, we can generate controlled-length binary keys that maintain complexity.

15. Algorithm for Encoding a Message

[

11] The encoding process relies on the algorithm previously outlined for finding a number that represents a sequence. In this context, increments and decrements are treated as binary values: increments are encoded as 1s and divisions as 0s. This transformation enables the generation of a number that uniquely represents the chosen sequence. The following steps describe the encoding process:

Identify the sequence of operations (increments and divisions).

Convert increments to binary 1s and decrements to binary 0s.

Generate a number that encodes the sequence of 1s and 0s.

-

Along with the encoded number , two keys are passed:

- -

The length of the encoded sequence, denoted as .

- -

G factor

For decoding the encoded message, the Collatz operations are applied using the chosen G value. The decoding process proceeds as follows:

Starting with the chosen G, apply the Collatz operations for odd numbers and for even numbers.

Perform these operations until the length of the sequence reaches .

The decoded sequence can be verified by comparing the resulting sequence of increments (1s) and decrements (0s) with the original sequence.

The encoding and decoding processes are reversible, ensuring that the original sequence can be successfully retrieved from the encoded message using the correct G value and sequence length.

Example Encoding

Consider the number

. Its Collatz sequence is:

Using the rule where

represents ’1’ and

represents ’0’, the transitions encode as:

Thus, the sequence for is **"1000"**.

This binary representation can be extended to create longer cryptographic keys by concatenating multiple numbers’ sequences or introducing controlled variations in starting conditions.

The unpredictable yet deterministic nature of the Collatz pattern makes it an exciting candidate for encryption, hashing, or pseudo random number generation in cryptographic applications.

16. Conclusion

This research has proven a significant part of the conjecture, establishing that infinite growth is impossible in these sequences. We also demonstrated that the conditions for forming loops other than the 4-2-1 cycle are extremely difficult to satisfy. Through our analysis, we established rules to identify sequences following similar recurrence relations to the Collatz conjecture. It was found that there are infinitely many such conjectures, each exhibiting unique patterns and loops.We have developed an algorithm capable of generating any number within a specific sequence of Collatz operations and explored its potential applications in cryptography.

17. Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no knowncompeting financial interests or personal relationships that could have appearedtoin fluence the work reported in this article.

References

- Schwob, M.R.; Shiue, P.; Venkat, R. Novel theorems and algorithms relating to the Collatz conjecture. International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences 2021, 2021, 5754439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W. A new approach on proving Collatz conjecture. Journal of Mathematics 2019, 2019, 6129836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T. Almost all orbits of the Collatz map attain almost bounded value. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:abs/1909.03562. [Google Scholar]

- Barina, D. Convergence verification of the Collatz problem. The Journal of Supercomputing 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Lothar, R.; Saleem, W. Precalculus, 7th ed; Cengage Learning, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, I.M.; Shen, A. Algebra; Birkhäuser, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Redlin, L.; Watson, S. Precalculus, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, N.; Herbert, S.Z.; Hugh, L.M. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 1991; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/An+Introduction+to+the+Theory+of+Numbers,+5th+Edition-p-9780471625469.

- Sheldon, M.R. Introduction to Probability and Statistics for Engineers and Scientists, 6th ed.; Elsevier, 2020; Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/books/introduction-to-probability-and-statistics-for-engineers-and-scientists/ross/978-0-12-817747-9.

- Burton, D. M. Elementary Number Theory; Pearson Education.

- Python Code for generating smallest number for a Collatz sequence. Available online: https://github.com/MohamedYa123/CollatzEncoding.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).