Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

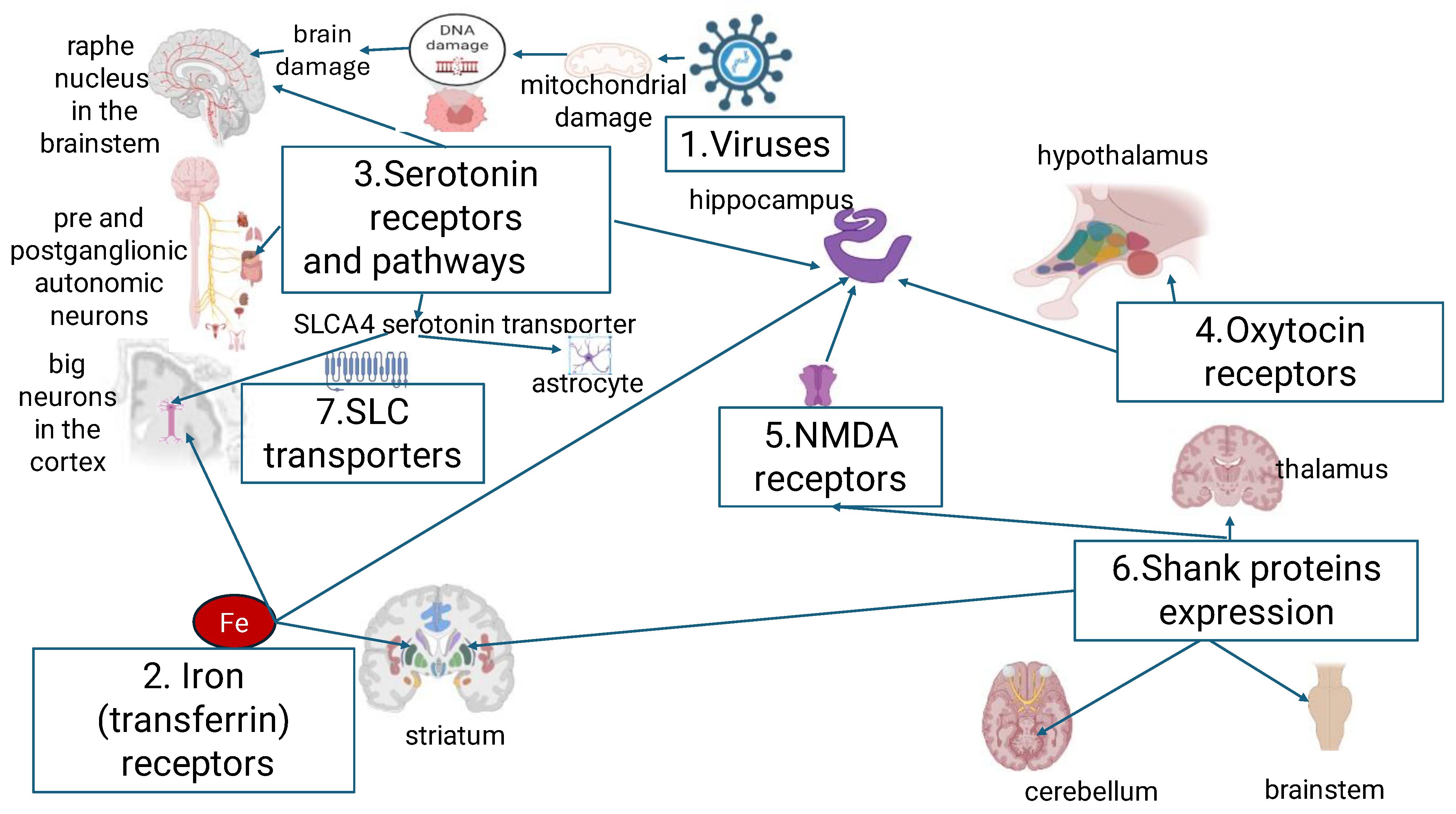

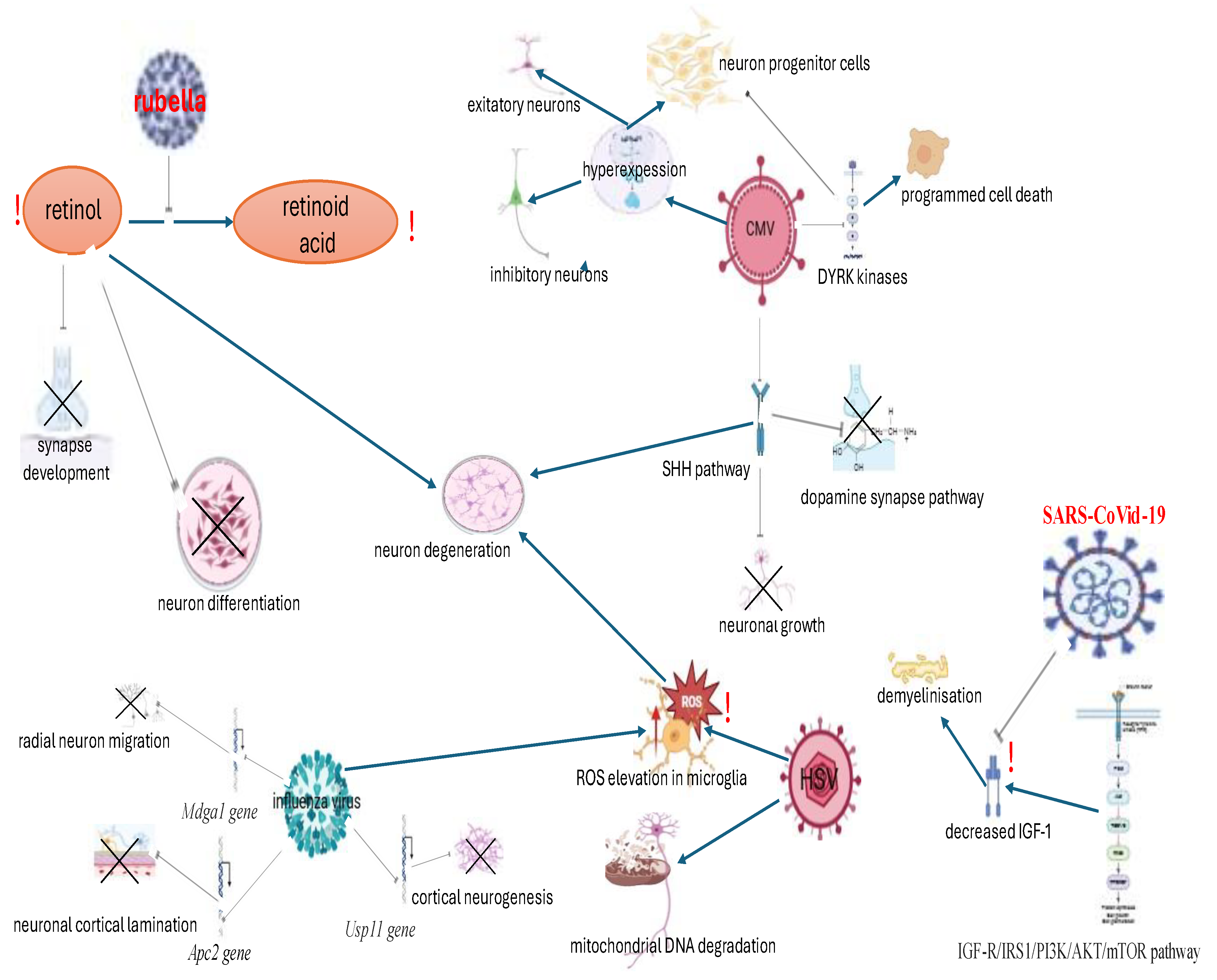

2. The Role of Viruses

3. The Role of Iron Metabolism

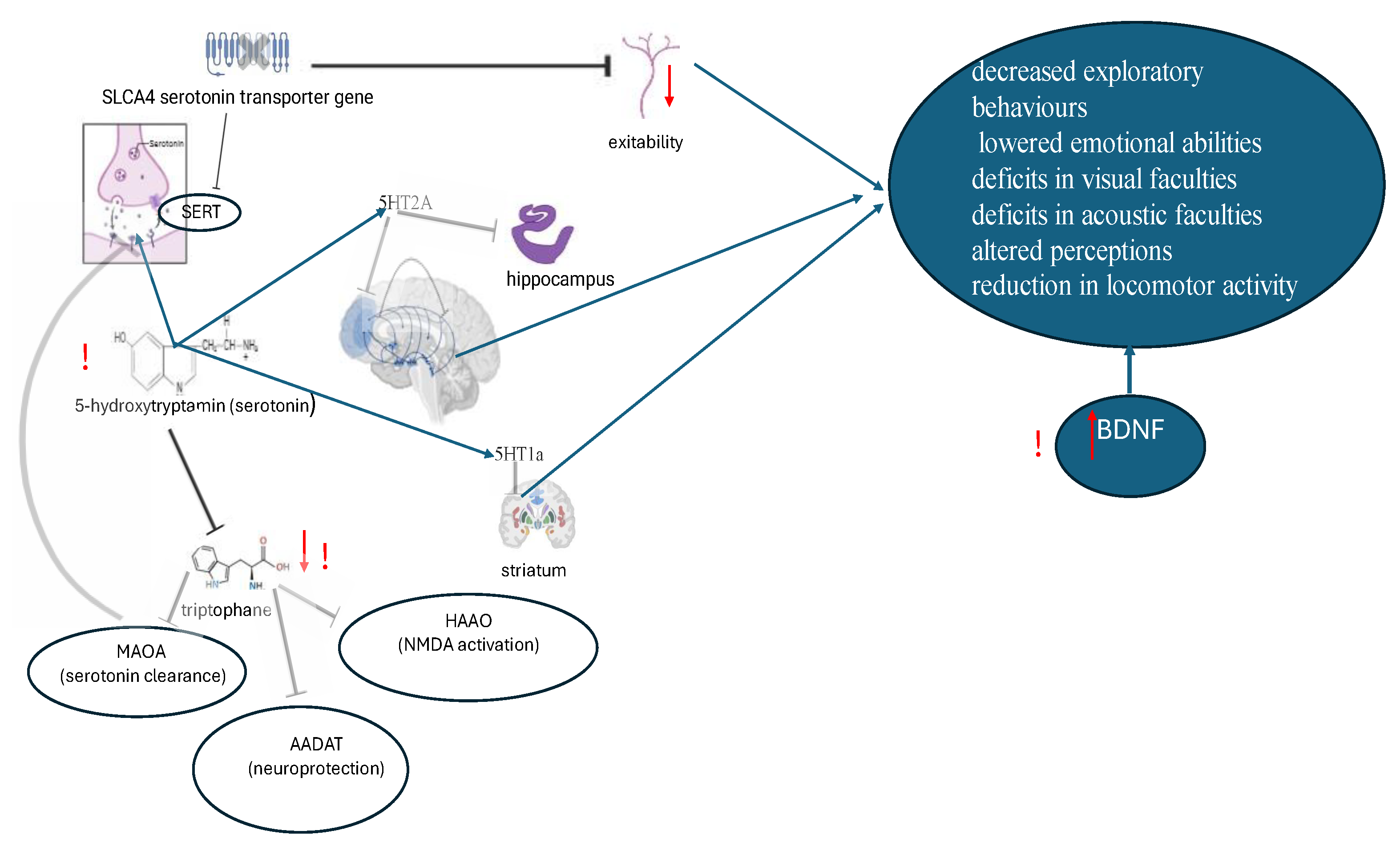

4. The Role of Serotonin Pathway

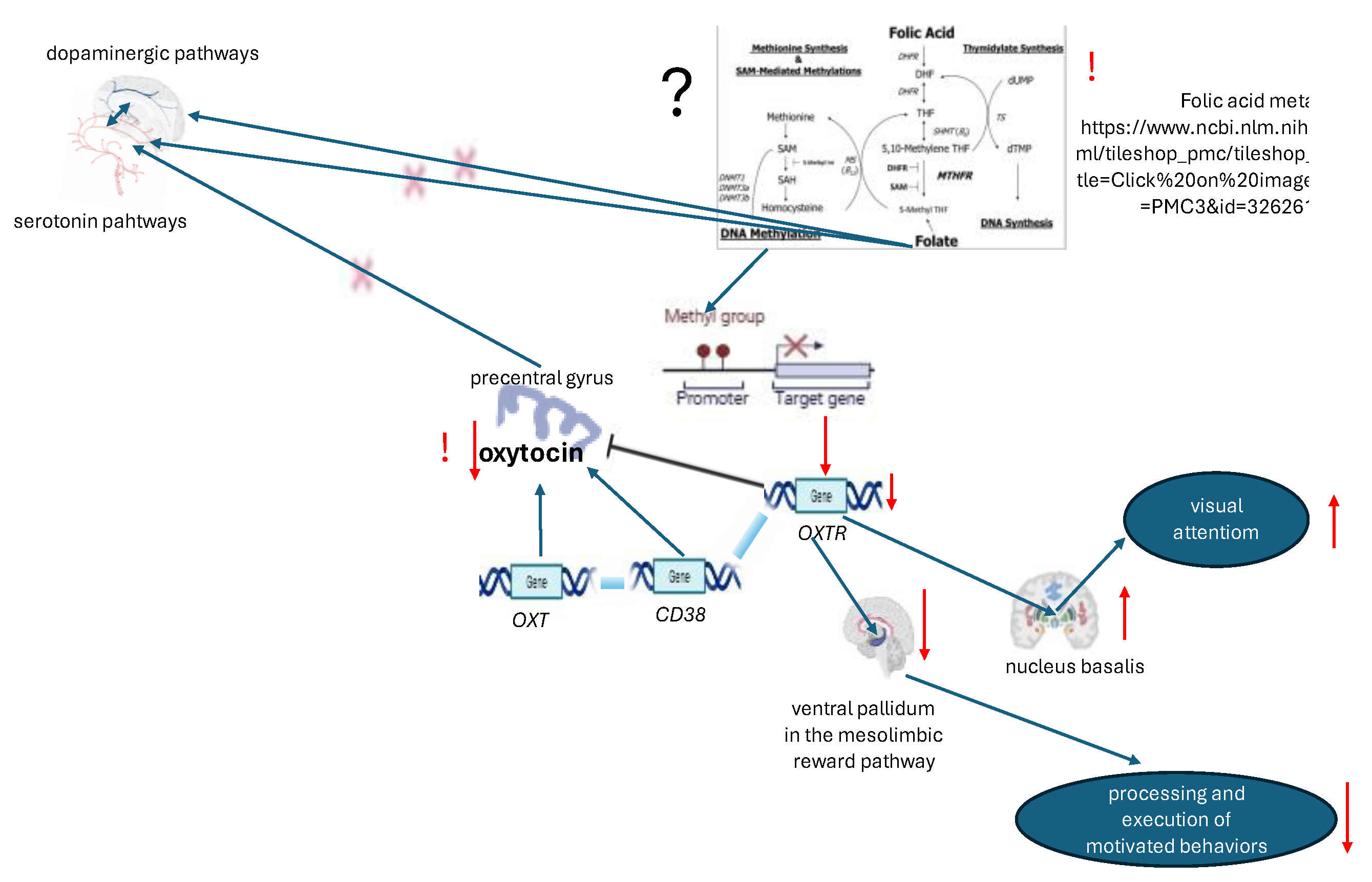

5. The Role of Oxytocin

6. The Role of NMDA and SHANK

7. Discussion (Clinical Comparisons, Suggested Biomarkers and Modulation Possibilities)

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodges, H.; Fealko, C.; Soares, N. Autism spectrum disorder: definition, epidemiology, causes, and clinical evaluation. Transl Pediatr. 2020 Feb;9 (Suppl 1):P.55-65. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Li Y, Liu B, Qian Li,; Yanmei Li, ; Qingsong Chen, ; Xiaohui Xing, ; Guifeng Xu, ; Wenhan Yang. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children and Adolescents in the United States From 2019 to 2020. AMA Pediatr. [CrossRef]

- Shuang, Qiu,; Yuping, Lu:, Yan Li,; Jikang, Shi,; Heran, Cui,; Yulu, Gu,; Yong, Li.; Weijing, Zhong,; Xiaojuan, Zhu,; Yunkai, Liu,; Yi, Cheng,; Yawen, Liu,; Yichun, Qiao. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, Volume 284, 2020, 112679. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, J,; Fombonne, E,; Scorah, J,; Ibrahim, A,; Durkin, MS,; Saxena, S,; Yusuf, A,, Shih, A,; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. [CrossRef]

- Zahorodny, W.; Shenouda, J.; Sidwell, K.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the New York-New Jersey Metropolitan Area. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarotti, F.; Venerosi, A. Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Worldwide Prevalence Estimates Since 2014. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, IL.; Almeida, S. Genes Involved in the Development of Autism. Int Arch Commun. Disord. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rylaarsdam, L.; Guemez-Gamboa, A. Genetic Causes and Modifiers of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019, Aug 20;13:385. [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, Apte.; Aayush, Kumar. Correlation of mutated gene and signalling pathways in ASD. IBRO Neuroscience Reports. [CrossRef]

- Khachadourian, V.; Mahjani, B.; Sandin, S.; Kolevzon, A.; Buxbaum, JD.; Reichenberg, A.; Janecka, M. ; Comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder and their etiologies. Transl Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, J.; Rasga, C.; Santos, J.X.; Martiniano, H.; Marques, A.R.; Oliveira, G.; Vicente, A.M. Bridging Genetic Insights with Neuroimaging in Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Beltagi, M.; Saeed, NK.; Elbeltagi, R.; Bediwy, AS. ; Aftab, SAS.; Alhawamdeh, R; Viruses and autism: A Bi-mutual cause and effect. World J Virol. [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, A.; Medicamento, S.; Pedaci, C.; Giambersio, D.; Giannico, O.V.; Petruzzelli, M.G.; Simone, M.; Corsalini, M.; Marzulli, L.; Matera, E. Peripheral Iron Levels in Autism Spectrum Disorders vs. Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Preliminary Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytel, A.; Ostrowska, S.; Marcinkiewicz, K.; Krawczuk-Rybak, M. ; & Sawicka-Żukowska,, M. Ferritin – novel uses of a well-known marker in paediatrics. Pediatria Polska - Polish Journal of Paediatrics, 2023 98(1), 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Bener., A.; Khattab, AO.; Bhugra, D. Bener., A.; Khattab, AO.; Bhugra, D. et al. Iron and vitamin D levels among autism spectrum disorders children. Ann Afr Med. [CrossRef]

- Li, Chen; Xingzhi, Guo; Chen Hou, Peng; Tang, Xin; Zhang, Li; Chong Rui Li; The causal association between iron status and the risk of autism: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Nutr., 2022. [CrossRef]

- Muller, CL. ; Anacker, AMJ.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. The serotonin system in autism spectrum disorder: From biomarker to animal models. Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Yamasue, H.; Domes, G. ; Oxytocin and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, J.; Walitza, S.; Bobrowski, E.; Gundelfinger, R.; Grünblatt, E. Association study in siblings and case-controls of serotonin- and oxytocin-related genes with high functioning autism. J Mol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Raphaelle Mottolese, AB.; Jérôme Redouté, BC.; Nicolas Costes, C.; Didier Le Bars, BC. and Angela Sirigua, B. Switching brain serotonin with oxytocin. PNAS. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Feng; Zhang, Hao; Wang, Peng; Cui, Wenjie; Xu, Kaiyong; Chen, Dan; Hu, Minghui; Li, Zifa; Geng, Xiwen; Wei, Sheng. Oxytocin and serotonin in the modulation of neural function: Neurobiological underpinnings of autism-related behavior. Front. Neurosci., 22 July 2022. Sec. NeurodevelopmentVolume 16 – 2022. [CrossRef]

- Elshahawi, H.H.; Taha, G.R.A.; Azzam, H.M.E.; et al. N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibody in relation to autism spectrum disorder (ASD): presence and association with symptom profile. Middle East Curr Psychiatry, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Choi, S.; Kim, E. NMDA receptor dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Ruu-Fen, Tzang.; Chuan-Hsin, Chang.; Yue-Cune, Chang.; Hsien-Yuan, Lane. Autism Associated With Anti-NMDAR Encephalitis: Glutamate-Related Therapy, Front. Psychiatry, 21 June 2019. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry, Volume 10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yukti, Vyas.; Juliette, E.; Cheyne, Kevin, Lee.; Yewon, Jung.; Pang Ying, Cheung.;, Montgomery, Johanna M.; Shankopathies in the Developing Brain in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Neurosci.,. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Qi, Q.; Xu, T. Targeting Shank3 deficiency and paresthesia in autism spectrum disorder: A brief review. Front Mol Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Tao, L.; Cao, X.; Chen, L. The solute carrier transporters and the brain: Physiological and pharmacological implications. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2020 Mar;15(2):131-144. [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.; Almudhry, M.; Alghamdi, F.; Albaradie, R.; Ibrahim, M.; Aldurayhim, F.; Alhedaithy, A.; Alamr, M.; Bawazir, M.; Mohammad, S.; Abdelhay, S.; Bashir, S.; Housawi, Y. SLC gene mutations and pediatric neurological disorders: diverse clinical phenotypes in a Saudi Arabian population. Hum Genet. [CrossRef]

- Schuch, J. B.; Müller, D.; Endres, R. G.; Bosa, C. A.; Longo, D.; Schuler-Faccini, L.; Ranzan, J.; Becker, M. M.; dos Santos Riesgo, R.; Roman, T. Psychomotor agitation and mood instability in patients with autism spectrum disorders: A possible effect of SLC6A4 gene? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders,. [CrossRef]

- Shuid, A.N.; Jayusman, P.A.; Shuid, N.; Ismail, J.; Kamal Nor, N.; Mohamed, I.N. Association between Viral Infections and Risk of Autistic Disorder: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawlani, V.; ShivaShankar, J. J.; White, C. Magnetic resonance imaging findins in a case of congenital rubella encephalitis. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Thong, V N.; Van, H Ph.; Kenji, A. Pathogenesis of Congenital Rubella Virus Infection in Human Fetuses: Viral Infection in the Ciliary Body Could Play an Important Role in Cataractogenesis. eBioMedicine, 2015, Volume 2, Issue 1, 59 – 63.

- Jonathan, P. C.; Jörg, M. The role of retinoic acid signaling in maintenance and regeneration of the CNS: from mechanisms to therapeutic targeting. Front. Mol. Neurosci., Sec. Molecular Signalling and Pathways, Volume 17 – 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oza, Y. R.; Mody, M.; Avula, M.; Allahudeen, S. D.; Appana, L. S. M.; Ali, M. A. Understanding progressive rubella pan encephalitis: a rare neurological disorder. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, B.L.; Talge, N.; Ingersoll, B.; Smith, A.; Glazier, A.; Kerver, J.; Paneth, N.; Racicot K. Maternal cytomegalovirus sero-positivity and autism symptoms in children. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018. May;79(5):e12840. [CrossRef]

- Pesch, M.H.; Leung, J.; Lanzieri, T.M.; Tinker, S.C.; Rose, C.E.; Danielson, M.L.; Yeargin-Allsopp, M.; Grosse, S.D. ; Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnoses and Congenital Cytomegalovirus. Pediatrics. [CrossRef]

- Piccirilli, G. , Gabrielli, L., Bonasoni, M.P.et al. Fetal Brain Damage in Human Fetuses with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Histological Features and Viral Tropism. Cell Mol Neurobiol. [CrossRef]

- Egilmezer, E. , Hamilton, S.T., Foster, C.S.P.et al. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) dysregulates neurodevelopmental pathways in cerebral organoids. Commun Biol. [CrossRef]

- Milada, M.; Siri, M.; Hege, M. B.; Gunnes, N. , et al. Maternal Immunoreactivity to Herpes Simplex Virus 2 and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Male Offspring. mSphere, 2017; 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, I.; Zappulo, E.; Bonavolta, R.; Maresca, R.; Ricci, M.P.; et al. Prevalence of herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 antibodies in patients with autism spectrum disorders. In Vivo. [PubMed]

- Duarte, L.F.; Farias, M.A.; Álvarez, D.M.; Bueno, S.M.; Riedel, C.A.; González, P.A. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection of the Central Nervous System: Insights Into Proposed Interrelationships With Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, A.M.; Connolly, M.G.; Gonzalez-Ricon, R.J.; et al. Influenza A virus during pregnancy disrupts maternal intestinal immunity and fetal cortical development in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.M.; Zhu, Y.; Bucher, C.; McGinnis, W.; Ryan, L.K.; Siegel, A.; Zalcman, S. Gestational flu exposure induces changes in neurochemicals, affiliative hormones and brainstem inflammation, in addition to autism-like behaviors in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, Volume 33, 2013, Pages 153-163. [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Culqui, T.A.; Getahun, D.; Chiu, V.; Sy, L.S.; Tseng, H.F. Prenatal Influenza Vaccination or Influenza Infection and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring. Clin Infect Dis. [CrossRef]

- Zerbo, O.; Qian, Y.; Yoshida, C.; Fireman, B.H.; Klein, N.P.; Croen, L.A. Association between influenza infection and vaccination during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Pediatr. [CrossRef]

- Steinman, G. COVID-19 and autism. Med Hypotheses. [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Mashayekhi, F.; Salehi, Z. Analysis of Insulin-like growth factor-1 serum levels and promoter (rs12579108) polymorphism in the children with autism spectrum disorders, Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, V. 99, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Liu L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Has the Potential to Be Used as a Diagnostic Tool and Treatment Target for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Lichun, L.; Yongxing, L.; Zhidong, Z.; Qingxian, F.; Yuelian, J. Identification of Ferroptosis-Related Molecular Clusters and Immune Characterization in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Frontiers in Genetics. Sec. Computational Genomics. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J Hematol Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Parween, F.; Edara, N.; Zhang, H.; Gardina, P. ; Otaizo-Carrasquero, F, Myers, T,; Farber, J.M. The circadian clock gene ARNTL regulates the expression of CCR6 and Th17 related genes in human cells. J Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Tai, B.; Li, W.; Li, T. Ferroptosis and Its Multifaceted Roles in Cerebral Stroke. Front Cell Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, JP.; Krysko, DV.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis at the crossroads of cancer-acquired drug resistance and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Xie, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, X.; Lotze, M. T.; Zeh, H. J. Tang, D. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Du, J.; Kong, N.; Zhang, GY.; Liu, MZ.; Liu, C. Mechanisms and pharmacological applications of ferroptosis: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, P.; Kumari, R.; Sinha, N.; Kumar, S.; Sinha, P. Evaluation of Iron Status in Children with Autism Spectral Disorder: A Case-control Study. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research,. [CrossRef]

- Rabaya, S. ;∙Nairat, S, ∙Bader K.; Mohammad M.; Herzallah MM.;∙ Darwish, HM. Iron metabolism in autism spectrum disorder; inference through single nucleotide polymorphisms in key iron metabolism genes. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Giambersio, D.; Marzulli, L.; Margari, L.; Matera, E.; Nobili, L.; De Grandis, E.; Cordani, R.; Barbieri, A.; Peschechera, A.; Margari, A.; et al. Correlations between Sleep Features and Iron Status in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, K.; Marchezan, J.; Faccioli, LS.; Riesgo, R..; Perry IS.; Anemia Associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int J Pediat Health Care Adv. 2016 ,3(2), 17-20. ISSN 2572-7354.

- Kanney, ML. ; Durmer,; JS, Trotti,LM.; Leu, R. Rethinking bedtime resistance in children with autism: is restless legs syndrome to blame? J. Clin Sleep Med. [CrossRef]

- Taeubert, MJ.; de Prado-Bert, P.; Geurtsen, ML.; et al. Maternal iron status in early pregnancy and DNA methylation in offspring: an epigenome-wide meta-analysis. Clin Epigenet 2022, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Chauhan, V.; Brown, WT.; Cohen, I. Oxidative stress in autism: Increased lipid peroxidation and reduced serum levels of ceruloplasmin and transferrin - the antioxidant proteins. Life sciences (1973). [CrossRef]

- Abe, E.; Fuwa, T.J.; Hoshi, K.; Saito, T.; Murakami, T.; Miyajima, M.; Ogawa, N.; Akatsu, H.; Hashizume, Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; et al. Expression of Transferrin Protein and Messenger RNA in Neural Cells from Mouse and Human Brain Tissue. Metabolites 2022, 12, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petralla, S.; Saveleva, L.; Kanninen, KM.; et al. Increased Expression of Transferrin Receptor 1 in the Brain Cortex of 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Is Associated with Activation of HIF-1 Signaling Pathway. Mol Neurobiol.

- Pérez, MJ.; Carden, TR.; dos Santos Claro, PA.; et al. Transferrin Enhances Neuronal Differentiation. ASN Neuro. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, RC.; Sosa, JC.; Gardeck, AM.; Baez, AS, Lee CH., Wessling-Resnick, M. Inflammation-induced iron transport and metabolism by brain microglia. J Biol Chem. 2018 May 18;293(20):7853-7863. [CrossRef]

- Mensikova K.; Katerina Bucilova, K., Konickova, D.; Kurcova, S.; Otruba, P.; Grambalova, Z.; Kaiserova, M.; Petr Kanovsky, P. Transferrin as a Possible CSF Biomarker in Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies (P3-11.004). Neurology.2023. 100 (17, supplement 2). [CrossRef]

- Suri, D.; Teixeira, CM.; Cagliostro, MK.; Mahadevia, D. Ansorge, MS. Monoamine-sensitive developmental periods impacting adult emotional and cognitive behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hao, Z.; Peng, W.; Wenjie, C.; Kaiyong, Xu. et.al. Oxytocin and serotonin in the modulation of neural function: Neurobiological underpinnings of autism-related behavior. Frontiers in Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ying, X.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D.; Liu, J.; et al. Association of human serotonin receptor 4 promoter methylation with autism spectrum disorder. Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, A.; Richard, N.; Mottolese, R.; Leboyer, M.; Sirigu, A. An Association Between Serotonin 1A Receptor, Gray Matter Volume, and Sociability in Healthy Subjects and in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res 2020, 13, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higazi, A.M.; Kamel, H.M.; Abdel-Naeem, E.A.; et al. Expression analysis of selected genes involved in tryptophan metabolic pathways in Egyptian children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and learning disabilities. Sci Rep, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormstad, H.; Bryn, V.; Verkerk, R.; Skjeldal, O. H.; Halvorsen, B.; Saugstad, O. D.; Isaksen, J.; Maes, M. Serum Tryptophan, Tryptophan Catabolites and Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor in Subgroups of Youngsters, with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cns & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets, 2018, 7, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Coelho, D. Does the kynurenine pathway play a pathogenic role in autism spectrum disorder? Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijben, HJ.; Superti-Furga, G.; IJzerman, AP.; Heitman, LH. Targeting solute carriers to modulate receptor–ligand interactions, Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, Volume 43, Issue 5, 2022, Pages 358-361, doi :10.1016/j.tips.2022.02.004.

- Bala, K.; Aran, Kh. R. Exploring the common genes involved in autism spectrum disorder and Parkinson's disease: A systematic review, Aging and Health Research, Volume 4, Issue 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Dong, J.; Ruan, W.; Duan, X. Potential Theranostic Roles of SLC4 Molecules in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 4, 15166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, D.S.; Rokicki, J.; van der Meer, D.; et al. Oxytocin pathway gene networks in the human brain. Nat Commun 10, 668, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, A.M.; Rokicki, J.; Birkeland, S.; et al. An evolutionary timeline of the oxytocin signaling pathway. Commun Biol, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Hsu, K.S. Oxytocin receptor signaling in the hippocampus: Role in regulating neuronal excitability, network oscillatory activity, synaptic plasticity and social memory. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 171, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierzynowska, K.; Gaffke, L.; Żabińska, M.; Cyske, Z.; Rintz, E.; Wiśniewska, K.; Podlacha, M.; Węgrzyn, G. Roles of the Oxytocin Receptor (OXTR) in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, S.M.; Palumbo, M.C.; Lawrence, R.H.; Smith, A.L.; Goodman, M.M.; Bales, K.L. Effect of age and autism spectrum disorder on oxytocin receptor density in the human basal forebrain and midbrain. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andari, E.,; Nishitani, S.; Kaundinya, G.; Caceres, GA.; Morrier, MJ.’ Ousley, O.; Smith, AK.; Cubells, JF.; Young, LJ. Epigenetic modification of the oxytocin receptor gene: implications for autism symptom severity and brain functional connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jun;45(7):1150-1158. [CrossRef]

- El-Ramly, Amal; Samy, Azza; Soliman, Eman; Oteify, Golnar. Evaluation of oxytocin and serotonin levels in autism spectrum disorder, Journal of Medicine in Scientific Research: 2018 Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 12. [CrossRef]

- John, S.; Jaeggi, A. V. Oxytocin levels tend to be lower in autistic children: A meta-analysis of 31 studies. Autism. [CrossRef]

- Lefevre, A.; Richard, N.; Jazayeri, M.; Beuriat, PA.; Fieux, S.; Zimmer, L.; Duhamel, JR. , Sirigu, A. Oxytocin and Serotonin Brain Mechanisms in the Nonhuman Primate. J Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Dölen, G.; Darvishzadeh, A. ; Huang, KW; Malenka, RC. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Ambrogini, P.; Chruścicka, B.; Lindskog, M.; Crespo-Ramirez, M.; Hernández-Mondragón, J.C.; Perez de la Mora, M.; Schellekens, H.; Fuxe, K. The Role of Central Serotonin Neurons and 5-HT Heteroreceptor Complexes in the Pathophysiology of Depression: A Historical Perspective and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker-Azmitia, PM. Behavioral and cellular consequences of increasing serotonergic activity during brain development: A role in autism? Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005, 2005.23, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaurain, M.; Salabert, A.-S.; Payoux, P.; Gras, E.; Talmont, F. NMDA Receptors: Distribution, Role, and Insights into Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, KB.; Wollmuth, LP.; Bowie, D.; Furukawa, H.; Menniti, FS.; Sobolevsky, AI.; Swanson, GT.; Swanger, SA.; et al. Structure, Function, and Pharmacology of Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels. Pharmacol Rev. [CrossRef]

- Vyklicky, V.; Stanley, C.; Habrian, C.; et al. Conformational rearrangement of the NMDA receptor amino-terminal domain during activation and allosteric modulation. Nat Commun 2021, 2021 12, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M. ; Yong,XLH.; Roche KW.; Anggono, V. Regulation of NMDA glutamate receptor functions by the GluN2 subunits. J Neurochem. [CrossRef]

- Sprengel, R.; Eltokhi, A. Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors (and Their Role in Health and Disease). In: Pfaff, D.W., Volkow, N.D., Rubenstein, J.L. (eds) Neuroscience in the 21st Century. Springer, Cham. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Egunlusi, AO.; Joubert, J. NMDA Receptor Antagonists: Emerging Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications in Neurological Disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Hagino, Y.; Kasai S.; Ikeda K.; Specific Roles of NMDA Receptor Subunits in Mental Disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2015;15 (3):193-205. [CrossRef]

- Kysilov, B.; Kuchtiak, V.; Hrcka Krausova, B.; et al. Disease-associated nonsense and frame-shift variants resulting in the truncation of the GluN2A or GluN2B C-terminal domain decrease NMDAR surface expression and reduce potentiating effects of neurosteroids. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, SJ.; Yuan, H.; Kang, JQ. ; Tan, FCK.; Traynelis SF.; Low CM. Distinct roles of GRIN2A and GRIN2B variants in neurological conditions. F1000Res. 2019 Nov 20;8: F1000 Faculty Rev-1940. [CrossRef]

- Tumdam, R.; Hussein, Y.; Garin-Shkolnik, T.; Stern, S. NMDA Receptors in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Pathophysiology and Disease Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanari, M. , Martella, G.; Bonsi, P.; Meringolo, M. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Focus on Glutamatergic Neurotransmission. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Kim, K.; Serraz, B.; Cho, YS.; Kim, D.; Kang, M.; Lee, EJ.; Lee, H.; Bae, YC.; Paoletti, P.; Kim, E. Early correction of synaptic long-term depression improves abnormal anxiety-like behavior in adult GluN2B-C456Y-mutant mice. PLoS Biol. [CrossRef]

- Sabo, SL.; Lahr, JM.; Offer, M.; Weekes, ALA.; Sceniak, MP. GRIN2B-related neurodevelopmental disorder: current understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2023, 14:1090865. [CrossRef]

- Leblond, CS.; Nava, C.; Polge, A.; Gauthier, J.; Huguet, G.; Lumbroso, S.; et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Unravelling the role of SHANK3 mutations in targeted therapies for autism spectrum disorders. Discov Psychol, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, TC.; Speed, HE.; Xuan, Z.; Reimers, JM.; Escamilla, CO.; Weaver, TP.; Liu, S.; Filonova, I.; Powell, CM. Novel Shank3 mutant exhibits behaviors with face validity for autism and altered striatal and hippocampal function. Autism Res. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Park, M. Shank postsynaptic scaffolding proteins in autism spectrum disorder: Mouse models and their dysfunctions in behaviors, synapses, and molecules. Pharmacol Res. [CrossRef]

- Lisé, MF.; El-Husseini, A. The neuroligin and neurexin families: from structure to function at the synapse. Cell Mol Life Sci. [CrossRef]

- Altas, B.; Tuffy, LP.; Patrizi, A.; Dimova, K.; Soykan, T. et. al. Region-Specific Phosphorylation Determines Neuroligin-3 Localization to Excitatory Versus Inhibitory Synapses. Biol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Peñagarikano, O.; Geschwind, DH. What does CNTNAP2 reveal about autism spectrum disorder? Trends Mol Med. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, D. ; Cho, KKA.; Shelton, SM.; Paul, A.; Huang, ZJ.; Sohal, VS.; Rubenstein, JLR. Mouse Cntnap2 and Human CNTNAP2 ASD Alleles Cell Autonomously Regulate PV+ Cortical Interneurons. Cereb Cortex. [CrossRef]

- Chalkiadaki, K.; Statoulla, E.; Zafeiri, M.; Voudouri, G. GABA/Glutamate Neuron Differentiation Imbalance and Increased AKT/mTOR Signaling in CNTNAP2-/- Cerebral Organoids. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. [CrossRef]

- Tan, BT.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Long, ZY.; Wu, YM.; Liu, Y. Retinoic acid induced the differentiation of neural stem cells from embryonic spinal cord into functional neurons in vitro. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. [PubMed]

- Lazzeri, G.; Lenzi, P.; Signorini, G.; Raffaelli, S.; Giammattei, E.; Natale, G.; Ruffoli, R.; Fornai, F.; Ferrucci, M. Retinoic Acid Promotes Neuronal Differentiation While Increasing Proteins and Organelles Related to Autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, CH.; Grandits, AM.; Purton, LE.; Sill, H.; Wieser, R. All-trans retinoic acid in non-promyelocytic acute myeloid leukemia: driver lesion dependent effects on leukemic stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2020 Oct;19(20):2573-2588. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tong. X.; Lu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, T. All-trans retinoic acid in hematologic disorders: not just acute promyelocytic leukemia. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15:1404092. [CrossRef]

- Levada, OA.; Troyan, AS. Insulin-like growth factor-1: a possible marker for emotional and cognitive disturbances, and treatment effectiveness in major depressive disorder. Ann General Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Levada, OA. ; Troya, AS; Pinchuk, IY. Serum insulin-like growth factor-1 as a potential marker for MDD diagnosis, its clinical characteristics, and treatment efficacy validation: data from an open-label vortioxetine study. BMC Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Dichtl, S.; Haschka, D.; Nairz, M.; Seifert, M.; Volani, C.; Lutz, O.; Weiss, G. Dopamine promotes cellular iron accumulation and oxidative stress responses in macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Levada, OA.; Dobrodub, IV.; Trailin, AV. Reduced expression of dopamine d2-receptors on peripheral blood lymphocytes as a marker for progression of subcortical cognitive impairments. Zaporozhye Medical Journal, No 5, 2013, p.43-45.

- Gesundheit, B.; Zisman, PD.; Hochbaum, L.; Posen, Y.; Steinberg, A.; Friedman, G.; Ravkin, HD.; Rubin, E.; Faktor, O.; Ellis, R. Autism spectrum disorder diagnosis using a new panel of immune- and inflammatory-related serum biomarkers: A case-control multicenter study. Front Pediatr. [CrossRef]

- Stancioiu, F.; Bogdan, R.; Dumitrescu, R. Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE) as a Biomarker for Autistic Spectrum Disease (ASD). Life (Basel). 2023 Aug 13;13(8):1736. [CrossRef]

- Evers, M. ; Cunningham-Rundles.; C.; Hollander, E. Heat shock protein 90 antibodies in autism. Mol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Singh, VK. Phenotypic expression of autoimmune autistic disorder (AAD): a major subset of autism. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009 Jul-Sep;21(3):148-61. PMID: 19758536.

- Belenichev, IF.; Aliyeva, OG.; Popazova, OO.; Bukhtiyarova, NV. Involvement of heat shock proteins HSP70 in the mechanisms of endogenous neuroprotection: the prospect of using HSP70 modulators. Front Cell Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Iorgu, AM.; Inta, D.; Peter, G. Inducible HSP72 protein as a marker of neuronal vulnerability in brain research: A potential biomarker for clinical psychiatry?, Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry, V. 12, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Talalay, P.; Fahey, JW. Biomarker-Guided Strategy for Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2016;15(5):602-13. [CrossRef]

- Frye, RE.; Rincon, N.; McCarty, PJ.; Brister, D.; Scheck, AC.; Rossignol, DA. Biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Dis. [CrossRef]

- Manivasagam, T. ; Arunadevi. S.; Essa, M.; Saravana Babu, C.; Borah, A.; Thenmozhi, AJ.; Qoronfleh, MW. Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Autism. Adv Neurobiol. [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Ahmad, SF.; Bakheet, SA.; Al-Harbi, NO.; Al-Ayadhi, LY.; Attia, SM. ; Zoheir, KMA. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling is associated with upregulated NADPH oxidase expression in peripheral T cells of children with autism. Brain Behav Immun. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Du, Y.; Shi, S.; Cheng, Y. Antioxidant interventions in autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Manivasagam, T.; Arunadevi, S.; Essa, M. M.; SaravanaBabu, C.; Borah, A.; Thenmozhi, A. J.; Qoronfleh, M. W. Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Autism.

- Colucci-D’Amato, L.; Speranza, L.; Volpicelli, F. Neurotrophic Factor BDNF, Physiological Functions and Therapeutic Potential in Depression, Neurodegeneration and Brain Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. [CrossRef]

- Shu-Hui, D.; Yu, C.; Shu-Ming, H.; Bo, Zh. The Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling in Central Nervous System Disease Pathogenesis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. V.16. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, T.; Okamura, K.; Ikehara, M.; et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor from microglia regulates neuronal development in the medial prefrontal cortex and its associated social behavior. Mol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, JF.; Zanoni, MB.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. V.13. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathina, S.; Das, UN. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Arch Med Sci. [CrossRef]

- Troyan, AS.; Levada, OA. The Diagnostic Value of the Combination of Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 for Major Depressive Disorder Diagnosis and Treatment Efficacy. Front Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cong, Y.; Liu, H. Folic acid ameliorates depression-like behaviour in a rat model of chronic unpredictable mild stress. BMC Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Ahmavaara, K.; Ayoub, G. Cerebral Folate Deficiency in Autism Spectrum Disorder Folate in Nervous System Development Crimson Publishers Wings to the Research. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, DA.; Frye, RE. ; Cerebral Folate Deficiency, Folate Receptor Alpha Autoantibodies and Leucovorin (Folinic Acid) Treatment in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, DO. B Vitamins and the Brain: Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy--A Review. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Field, DT.; Cracknell, RO.; Eastwood, JR.; Scarfe, P.; Williams, CM.; Zheng, Y.; Tavassoli, T. High-dose Vitamin B6 supplementation reduces anxiety and strengthens visual surround suppression. Hum Psychopharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Havranek, Т.; Bacova, Z. ; Bakos J. Oxytocin, GABA, and dopamine interplay in autism. Endocrine regulations, 2024; 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerkerke, M.; Daniels, N.; Tibermont, L.; et al. Chronic oxytocin administration stimulates the oxytocinergic system in children with autism. Nat Commun. [CrossRef]

- Yingying, Z.; Xiaolu, Z.; Linghong, H. Optimal dose of oxytocin to improve social impairments and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: meta-analysis and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2025; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaurain, M.; Salabert, A.-S.; Payoux, P.; Gras, E.; Talmont, F. NMDA Receptors: Distribution, Role, and Insights into Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashi, A.; Koji, K.; Wataru, U.; Christina, A.; Kaito, T. ; S. Yuya. et. al. Reduced neurite density index in the prefrontal cortex of adults with autism assessed using neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging. Frontiers in Neurology. [CrossRef]

- Dionísio, A.; Espírito, A.; Pereira; A.C. et al. Neurochemical differences in core regions of the autistic brain: a multivoxel 1H-MRS study in children. Sci Rep 14, 2024, 2374. [CrossRef]

- Avino, T.; Hutsler.J.J. Supernumerary neurons within the cerebral cortical subplate in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research. V.1760, 2021, 147350. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, AK.; Hagmeyer, S.; Grabrucker, AM. Prenatal Zinc Deficient Mice as a Model for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Mills, Z.; Cheung, P.; Cheyne, JE.; Montgomery, JM. The Role of Zinc and NMDA Receptors in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pharmaceuticals. [CrossRef]

- Schoen, M.; Asoglu, H.; Bauer, HF. ; Müller, H-P.; Abaei, A.; Sauer, AK.; Zhang, R. et al. Shank3 Transgenic and Prenatal Zinc-Deficient Autism Mouse Models Show Convergent and Individual Alterations of Brain Structures in MRI. Front. Neural Circuits. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, DMD.; Kim, M.; Lee, HJ.; Botanas, CJ.; Custodio, RJP.; Sayson, LV.; Campomayor, NB.; Lee, C.; Lee, YS.; Cheong, JH.; Kim, HJ. 4-F-PCP, a Novel PCP Analog Ameliorates the Depressive-Like Behavior of Chronic Social Defeat Stress Mice via NMDA Receptor Antagonism. Biomol Ther (Seoul). [CrossRef]

- Dessus-Gilbert, ML. ; Nourredine. M.; Zimmer. L.; Rolland, B.; Geoffray, MM.; Auffret, M.; Jurek, L. NMDA antagonist agents for the treatment of symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Ralston, M.; Osman, A.; Suryadevara, P.; Cleland, E. Effect of Ketamine Treatment on Social Withdrawal in Autism and Autism-Like Conditions. Clin Neuropharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Harris, CP.; Jones, B.; Walker, K.; Berry, MS. Case report: Adult with bipolar disorder and autism treated with ketamine assisted psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Kurahashi, H.; Kunisawa, K.; Tanaka, K.F.; et al. Autism spectrum disorder-like behaviors induced by hyper-glutamatergic NMDA receptor signaling through hypo-serotonergic 5-HT1A receptor signaling in the prefrontal cortex in mice exposed to prenatal valproic acid. Neuropsychopharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; We, H.; Chen, WJ.; Zhu, S. Structural insights into the diverse actions of magnesium on NMDA receptors, Neuron, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Veer, P.; Akimbekov, NS.; Grant, WB.; Dean, C.; Fang, X.; Razzaque, MS. Neuroprotective effects of magnesium: implications for neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Frontiers in Endocrinology. [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, A. Targeting of glycine site on NMDA receptor as a possible new strategy for autism treatment. Neurochem Res. [CrossRef]

- Chen, WX.; Chen, YR.; Peng, MZ.; et al. Plasma Amino Acid Profile in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Southern China: Analysis of 110 Cases. J Autism Dev Disord. [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, M.; Prato, A.; Messina, M.; Meli, C.; Casabona, A.; Rizzo, R.; Barone, R. Neuroactive Amino Acid Profile in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results from a Clinical Sample. Children (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Salceda, R. Glycine neurotransmission: Its role in development. Front Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos, G.; Pasca, SP. A matter of space and time: Emerging roles of disease-associated proteins in neural development, Neuron,V. 2022; 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Qi, Q.; Xu, T. Targeting Shank3 deficiency and paresthesia in autism spectrum disorder: A brief review. Front Mol Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Has the Potential to Be Used as a Diagnostic Tool and Treatment Target for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Camino-Alarcón, J.; Robles-Bello, MA.; Valencia-Naranjo, N.; Sarhani-Robles, A. A Systematic Review of Treatment for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Sensory Processing and Sensory Integration Approach. Children (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Cerliani, L.; Mennes, M.; Thomas, RM.; Di Martino, A.; Thioux, M. Keysers, C. Increased functional connectivity between subcortical and cortical resting-state networks in autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Mc Glanaghy, E.; Bonnin, A.; Oberlander, TF. Developmental changes in serotonin signaling: Implications for early brain function, behavior and adaptation. Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, C.R.; Nelson, J.L.; Miller, S.N.; Rickert Hong, M.; Lambert, E.; Tallman Ruhm, H. Reversal of Autism Symptoms among Dizygotic Twins through a Personalized Lifestyle and Environmental Modification Approach: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prevailed ASD signs | Suggested biomarkers | Suggested combined modulation |

| History of prenatal viral exposure, DSM -5 relevant signs of DA deficit (unusual mood or emotional reactions, anxiety, stress, or excessive worry) | Retinoid status, dopamine, IgG antibodies to DA1 and DA2 receptors, BDNF, IgF-1, NSE, oxidative stress markers (malonic dialdehyde) | Folinic acid (leucovorin or L-methylfolate) or all-trans retinoic acid, antioxidants (glutation +Vit C + NAC), IgF-1 derived neurotrophins (mecasermine, trofinetid) |

| Parasomnias, restless legs syndrome, delayed language skills, DA deficit | Ferritin, transferrin, dopamine, IgG antibodies to DA1 and DA2 receptors, oxidative stress markers, Vit B 6 levels, NSE, HSP | DA agonists, antioxidants, Vit B6 |

| Negative DSM -5 relevant signs (avoids or does not keep eye contact, does not respond to name by 9 months of age, does not show facial expressions such as happy, sad, angry, and surprised by 9 months of age) | Serotonin, BDNF, IgF-1, tryptophan, folates, Vit B 6 levels | SSRI, folinic acid, VitB6 |

| DSM-5 relevant repetitive signs (focusing on parts of objects, obsessive interests, extreme interest or knowledge of specific, narrow topics, strong attachment to a certain object) | Oxytocin, folic circle genes, folates, vit B 6 levels. | Intranasal oxytocin, folates, vit B6, neurotrophins. |

| DSM-5 relevant cognitive signs (delayed cognitive or learning skills, hyperactive, impulsive, and/or inattentive behavior) | Plasma glutamate, magnesium, zinc, NSE, BDNF, IgF-1. | NMDARs antagonists, glycine, magnesium-containing drugs, zinc-containing drug |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).