1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), a malignancy arising from the biliary tract epithelium, is the second most common primary hepatic malignancy and accounts for approximately 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers. Despite advances in diagnostic imaging and oncology therapeutics, outcomes remain dismal with a five-year survival rate below 20% in most subtypes. The incidence of CCA is rising globally, and in the United States, this trend is most evident among older adults aged 65 and above. This demographic is also more likely to present with advanced disease and require inpatient care, compounding the challenges of treatment with geriatric vulnerability [

3].

In this context, frailty—a syndrome of decreased physiological reserve and resistance to stressors—has emerged as a critical determinant of outcomes in elderly populations. It has been associated with worse outcomes across a broad range of settings, including surgery, chemotherapy, and hospitalization. Importantly, frailty is conceptually distinct from multimorbidity: while both may coexist, comorbid conditions do not necessarily confer functional decline, and frailty may be present even in the absence of significant comorbid disease [

4].

While comorbidity indices such as the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index have been used extensively for risk adjustment in health services research, they may fail to capture subtle but clinically meaningful physiologic deficits [

2]. In contrast, the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS), developed and validated using ICD-10 diagnostic codes, offers a scalable method to quantify frailty in administrative datasets [

1]

(Table A1). Prior studies have demonstrated its utility in predicting adverse outcomes such as readmission, mortality, and institutionalization in general hospitalized populations. However, its use in the oncogeriatric setting—and specifically among hospitalized patients with cholangiocarcinoma—remains underexplored.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database for the years 2019 through 2022. Our study population included hospitalized adults aged 65 years or older with a primary or secondary diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, identified through specific ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (C22.1), perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (C24.0), distal cholangiocarcinoma (C24.1), or unspecified bile duct cancer. Hospitalizations were excluded if essential outcome data, such as discharge disposition, length of stay (LOS), or total hospital charges, were missing. Additionally, transfers from other acute-care hospitals were excluded to prevent duplication of patient data and ensure consistency in assessing initial hospital admissions.

Frailty status was assessed using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS), a validated scoring system developed by Gilbert et al. that quantifies frailty based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes associated with reduced physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to adverse health outcomes. Because Present-on-Admission (POA) flags were not available in the NIS dataset, the HFRS was calculated using all diagnostic codes documented during the index hospitalization. This may include conditions arising during the stay and is discussed as a limitation. The HFRS is specifically designed for scalable application in large administrative datasets and has been extensively validated among hospitalized older adults. Patients were classified into three categories based on their calculated HFRS: low frailty (HFRS <5), intermediate frailty (HFRS 5–15), and high frailty (HFRS >15).

Comorbidity burden was evaluated using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, comprising 30 chronic medical conditions defined by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) comorbidity software. This index provided an independent measure of chronic illness burden to complement the assessment of frailty.

The primary study outcomes included in-hospital mortality (binary outcome), LOS (continuous outcome, measured in days), and total hospital charges (continuous outcome, measured in U.S. dollars). To ensure nationally representative estimates, analyses were weighted using the complex survey sampling design provided by the NIS database. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the associations between frailty categories and in-hospital mortality. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for patient demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), hospital characteristics (hospital type, teaching status, urban or rural location), and comorbidity burden. For continuous outcomes (LOS and total hospital charges), multivariable linear regression models were utilized, adjusting for the same covariates. Results from linear regression analyses were reported as adjusted regression coefficients (β), with 95% confidence intervals indicating the magnitude of change in LOS and hospital charges associated with intermediate and high frailty categories compared to the low frailty category.

Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between frailty scores and comorbidity indices. Partial correlation analyses controlled for potential confounders, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and hospital characteristics, to clarify the independent predictive value of frailty compared to comorbidity measures.

All statistical analyses were two-tailed, and statistical significance was established at a p-value of less than 0.05. Data management, statistical modeling, and validation of results were performed in accordance with established guidelines for observational clinical research, ensuring methodological rigor, accuracy, and reproducibility.

We acknowledge inherent limitations associated with administrative data, including the inability to control for potentially confounding clinical factors such as cancer stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, detailed laboratory values, specific surgical interventions, chemotherapy treatments, or other targeted therapies. These limitations were carefully considered in the interpretation and contextualization of our findings.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Our final analytic cohort included 18,785 hospitalizations among patients aged 65 years or older with a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma

(Table 1). The median age was 74 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 69–80), with 54% identifying as male. The racial and ethnic composition was predominantly White (68.9%), followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (8.8%), and other or unknown categories (11.6%). The median length of stay (LOS) was 5 days (IQR: 3–8), and the median total hospital charge was

$59,615 (IQR:

$32,202–

$111,477). In-hospital mortality occurred in 7.18% of hospitalizations. Among survivors, 61.9% were discharged home, whereas 17.2% were discharged to skilled nursing or rehabilitation facilities, indicating substantial post-acute care needs.

3.2. Frailty and Comorbidity Profiles

Patients demonstrated a spectrum of frailty based on the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS): 25.7% met criteria for low frailty (HFRS <5), 58.7% had intermediate frailty (HFRS 5–15), and 15.8% had high frailty (HFRS >15). The six most documented comorbidities were solid cancer (46.4%), uncomplicated hypertension (45.9%), metastatic cancer (32.9%), complicated hypertension (25.2%), complicated diabetes (20.6%), and chronic pulmonary disease (16.4%).

Average total hospital charges (TOTCHG) in this cohort were $95,152 (SD $136,090), with a median of $60,029 (IQR $32,616–$111,917), and length of stay (LOS) averaged 6.86 days (SD 6.90) with a median of 5.0 days (IQR 3.0–8.0). The mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Score was 2.62, and the mean HFRS value was 6.05, indicating moderate overall frailty. We observed a statistically significant yet weak positive correlation between the HFRS and the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (r = 0.21, p < 0.001), suggesting that although these domains overlap, they reflect distinct clinical constructs in older adults hospitalized with cholangiocarcinoma.

3.3. In-Hospital Mortality

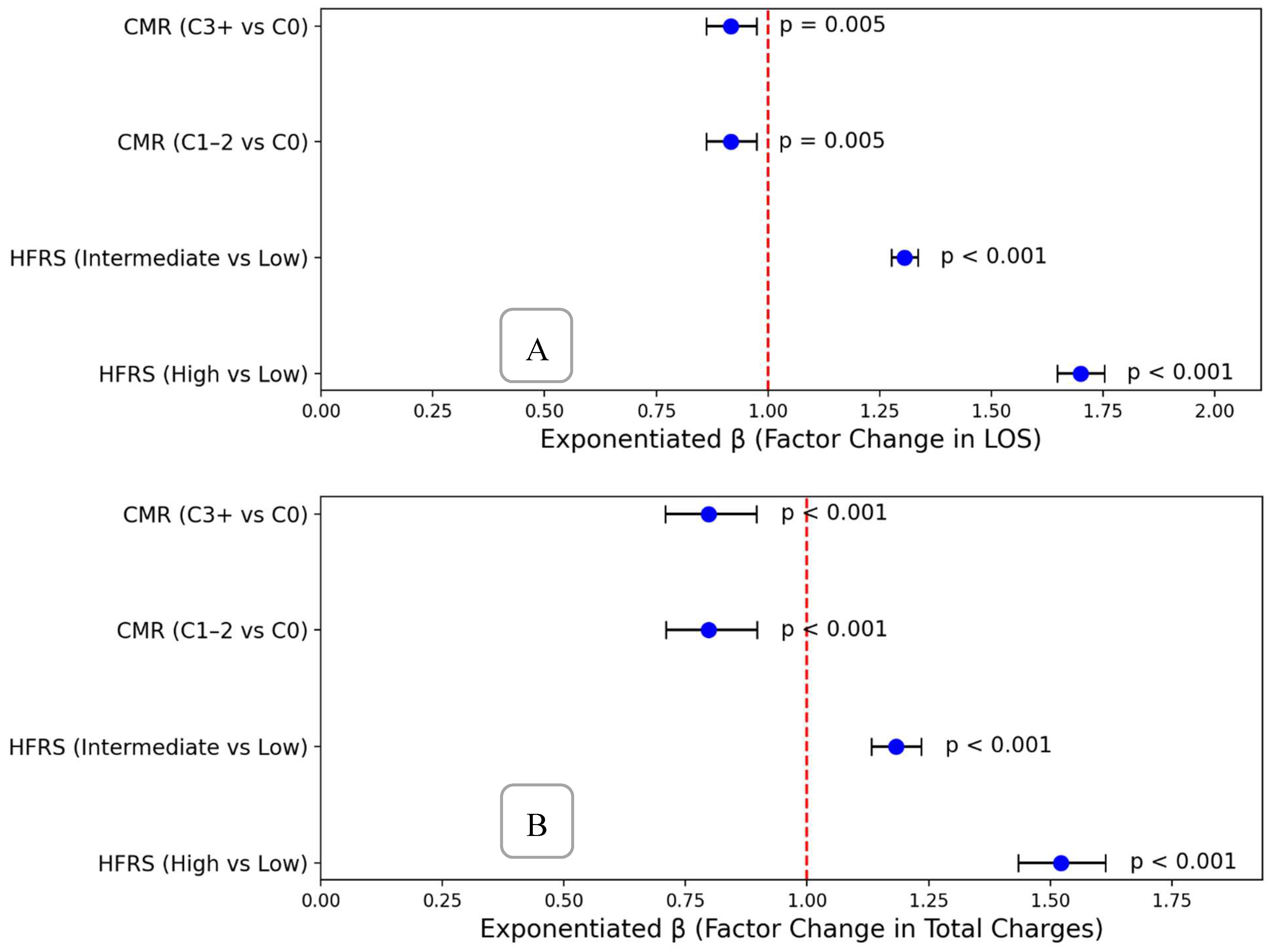

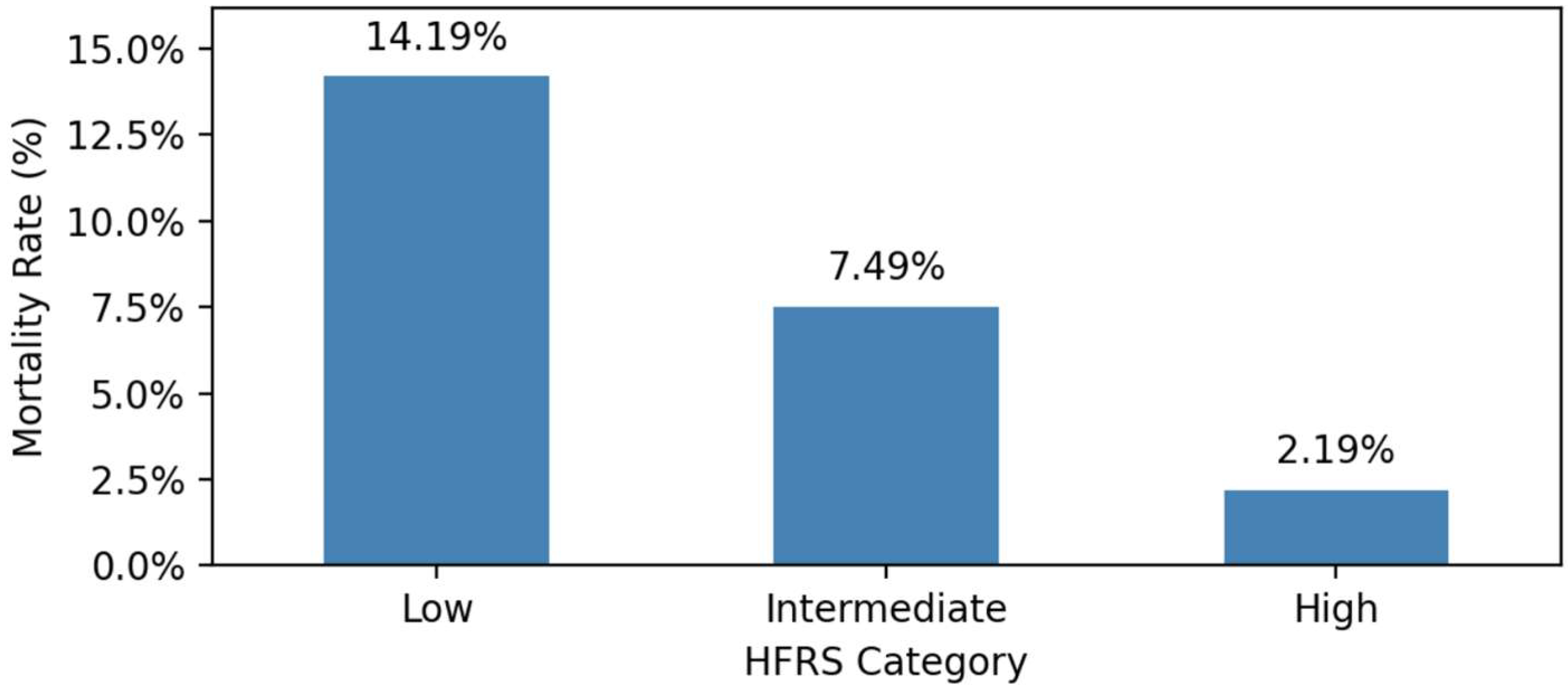

In unadjusted analyses, in-hospital mortality exhibited a stepwise increase with rising frailty severity, ranging from 2.19% among patients with low frailty (HFRS <5), to 7.49% in intermediate frailty (HFRS 5–15), and reaching 14.19% in high frailty (HFRS >15).

A multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for age and comorbidity categories, confirmed significantly higher odds of in-hospital mortality for patients in intermediate and high HFRS frailty categories compared to low HFRS frailty

(Figure 1). Specifically, relative to low frailty, intermediate frailty was associated with an approximately four-fold increase in the adjusted odds of mortality (adjusted odds ratio, aOR: 3.78; 95% CI: 3.44–4.14), while high frailty conferred nearly an eight-fold increase (aOR: 7.95; 95% CI: 7.20–8.78). Notably, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was not independently associated with mortality when HFRS frailty level was included, highlighting the superior prognostic value of frailty severity in predicting death among older adults hospitalized with cholangiocarcinoma

(Figure 2).

3.4. Length of Stay and Hospital Charges

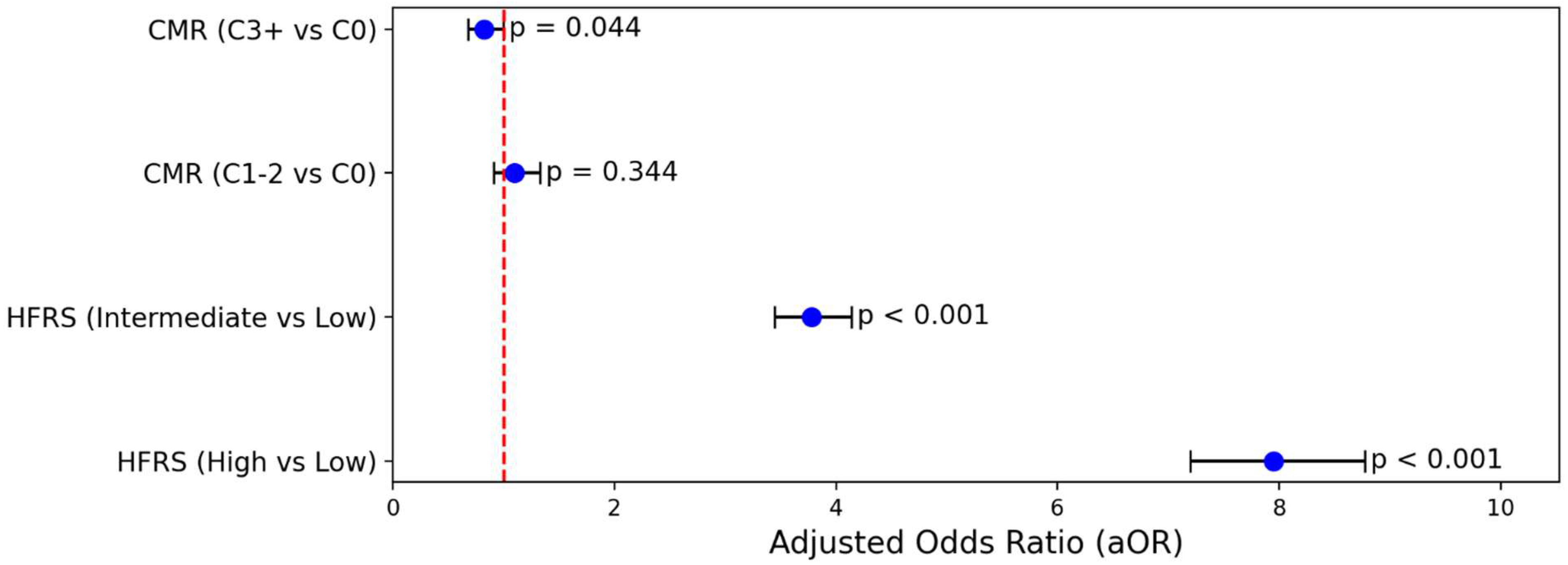

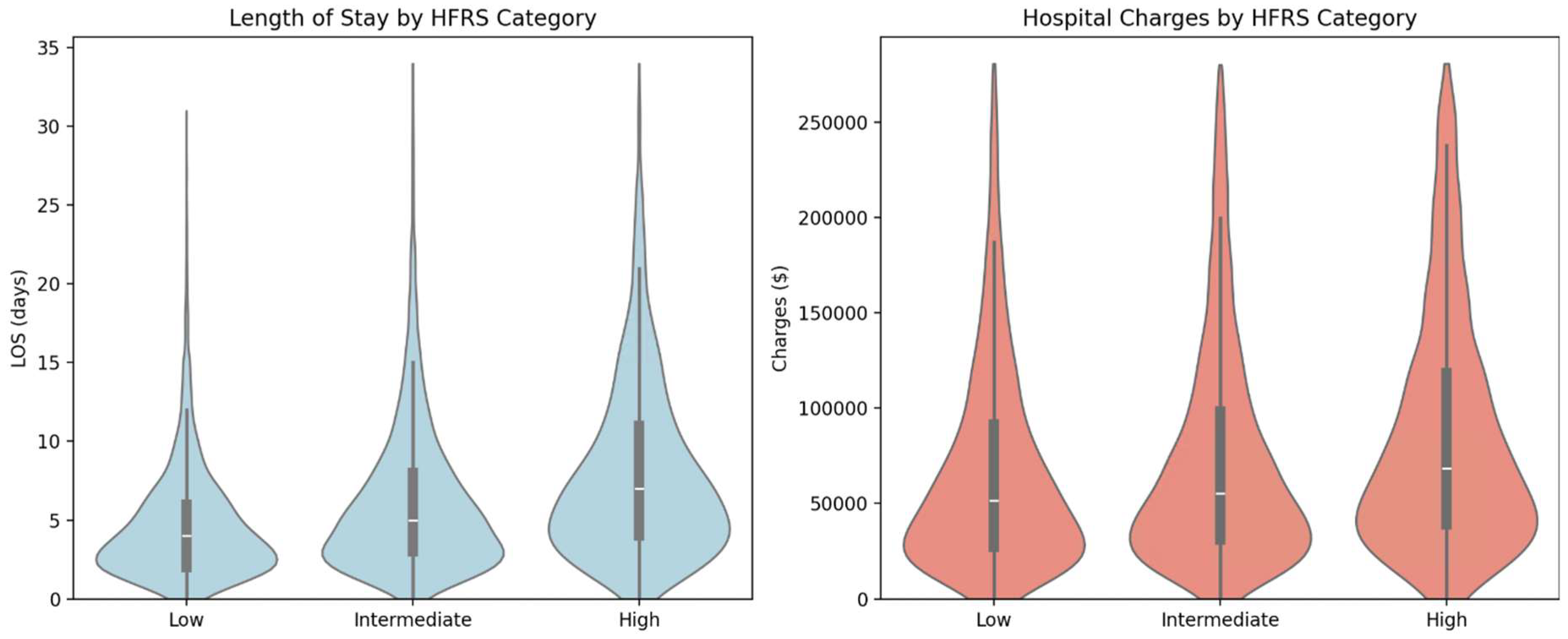

Higher HFRS frailty categories were strongly associated with increased hospital resource utilization

(Figure 3). Median length of stay (LOS) rose stepwise with HFRS severity: from 4.0 days (low frailty: HFRS <5) to 5.2 days (intermediate frailty: HFRS 5–15), reaching 6.8 days in the high frailty group (HFRS >15). A similar pattern was observed for hospital charges, with median charges ranging from

$45,000 (low HFRS frailty) to

$65,000 (intermediate HFRS frailty), and peaking at

$95,000 in the high HFRS group.

Adjusted linear regression analyses demonstrated robust and statistically significant associations between HFRS frailty categories and both length of stay (LOS) and total hospital charges. Compared to patients with low frailty (HFRS <5), those classified as having intermediate frailty (HFRS 5–15) experienced a 31% increase in LOS (adjusted β: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.28–1.34) and an 18% increase in total charges (adjusted β: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.13–1.24). Patients with high frailty (HFRS >15) had even more pronounced effects, with a 70% increase in LOS (adjusted β: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.65–1.75) and 52% higher hospital charges (adjusted β: 1.52; 95% CI: 1.43–1.61).

These findings underscore the powerful and independent role of frailty severity, as measured by the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS), in predicting hospital resource utilization among older adults with cholangiocarcinoma. The associations between HFRS category and both LOS and cost remained significant after adjustment for age and comorbidity burden, suggesting that frailty reflects a distinct and clinically meaningful dimension of vulnerability that is not captured by traditional comorbidity indices.

In contrast, comorbidity burden based on the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index demonstrated statistically significant but clinically modest associations with LOS and cost. Both moderate (C1–2) and high (C3+) comorbidity groups were associated with slightly reduced LOS (exponentiated β: 0.92, 95% CI: ~0.86–0.97) and approximately 20% lower charges (exponentiated β: ~0.80, 95% CI: ~0.71–0.90). This inverse relationship may reflect selective early mortality, limitations in care intensity, or potential differences in coding practices. Regardless of mechanism, the relatively small effect size of comorbidity stands in contrast to the much larger impact of frailty on hospital utilization (Figure 4).

Taken together, these results emphasize the superior prognostic value of HFRS frailty classification in this population. Given the complex clinical trajectories and high resource needs associated with cholangiocarcinoma in older adults, integrating frailty screening into routine workflows may aid in risk stratification, prognostication, and timely referral for supportive or palliative care services.

Figure 5.

(A) Forest Plot Showing Effects On Length of Stay (B) Forest Plot Showing Effects On Hospital Charges.

Figure 5.

(A) Forest Plot Showing Effects On Length of Stay (B) Forest Plot Showing Effects On Hospital Charges.

We observed a robust positive correlation (r = 0.64; p < 0.001) between LOS and total hospital charges. This relationship remained statistically significant after adjusting for age, sex, HFRS frailty level, and comorbidities, underscoring the high resource burden associated with frailty in older cholangiocarcinoma patients.

4. Discussion

This nationally representative study highlights the critical role of frailty in predicting adverse in-hospital outcomes among older adults with cholangiocarcinoma (CCA). Using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS), we identified a strong, independent association between frailty and increased mortality, prolonged length of stay (LOS), and higher healthcare costs. These associations persisted even after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidity burden as measured by the Elixhauser Index, emphasizing the unique prognostic value of frailty in this population (1,2).

Our findings are consistent with broader geriatric oncology literature: frailty represents a dynamic marker of physiological reserve and vulnerability to stressors, particularly hospitalizations (4). Unlike comorbidity indices that reflect disease burden, frailty scores encompass deficits in function, mobility, cognition, and resilience. Patients with high frailty had nearly eight-fold increased odds of in-hospital mortality compared to those with low frailty—a finding with significant implications for clinical decision-making, discharge planning, and goals-of-care discussions.

Interestingly, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, while widely used in health services research, demonstrated limited utility in this cohort. The weak correlation between Elixhauser score and HFRS (r = 0.21) suggests they measure overlapping but non-equivalent domains. Importantly, once frailty was included in the multivariable model, the Elixhauser score was no longer significantly associated with mortality, LOS, or total charges. This underscores the need to incorporate frailty screening into standard inpatient assessments, especially for older adults with complex oncologic diagnoses (1,2).

The observed gradients in LOS and hospitalization costs by frailty level mirror findings in other cancer types. A recent study in elderly patients with colorectal and lung cancer similarly reported that frailty, not comorbidity, was the primary determinant of acute care resource use (6). Our findings extend this concept to CCA, where patients with high frailty experienced 70% longer hospitalizations and incurred 52% higher charges than their low-frailty counterparts. Given the high costs associated with CCA-related hospitalizations, incorporating frailty into risk stratification models could improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

These findings also have implications for perioperative risk assessment. Although we did not examine surgical outcomes specifically, many CCA patients undergo invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures during hospitalization. Frailty screening may help identify patients who would benefit from prehabilitation, geriatric co-management, or palliative care referral rather than aggressive intervention (5).

Our data support the growing recognition that frailty is not only a patient-level risk factor but also a system-level indicator of complexity. HFRS—derived from routinely collected ICD-10 codes—offers a scalable tool for hospitals to identify high-risk patients, guide transitions of care, benchmark outcomes, and optimize resource allocation (1).

This study contributes to the limited literature applying HFRS in oncology populations. Prior work has validated HFRS in general medical and surgical cohorts; however, few studies have focused on high-risk cancers like CCA. The ability to apply HFRS retrospectively across large datasets enhances its utility in population health and quality improvement.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the use of administrative data limits granularity—clinical variables such as cancer stage, ECOG performance status, tumor burden, and treatment exposures were unavailable. Second, the HFRS may underestimate frailty in patients with functional or social deficits not captured in ICD codes. Additionally, some diagnoses contributing to HFRS—such as delirium or urinary tract infection—may occur during the hospitalization, raising the possibility of reverse causation. We also lacked post-discharge data, which precluded analysis of 30-day readmissions or long-term outcomes. Finally, residual confounding may persist despite adjustment for demographics and comorbidities.

Despite these limitations, our findings are strengthened using a large, nationally representative dataset, validated frailty and comorbidity indices, and robust multivariable models. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to systematically evaluate frailty as a prognostic factor in hospitalized older adults with cholangiocarcinoma.

In summary, frailty—as measured by the Hospital Frailty Risk Score—is a strong and independent predictor of mortality, hospital length of stay, and healthcare costs in older adults hospitalized with cholangiocarcinoma. Comorbidity indices such as the Elixhauser Index, while informative, do not fully capture the physiologic vulnerability associated with frailty. The implementation of scalable frailty screening tools such as HFRS may support more personalized, anticipatory, and resource-conscious care strategies for older adults with complex oncologic needs.

Author Contributions

M.M.S. drafted the manuscript, collected the data, and is the article guarantor. S.J.P. was responsible for the review of the literature. C.A.S.; software, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the methodology. V.A. and C.E. were responsible for the study conception, editing, critical review, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study used publicly available de-identified data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study are available from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Conflicts of Interest

C.E. and V.A. are consultants at Gilead Sciences and Madrigal Pharmaceuticals.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS) ICD-10 Codes and Assigned Weights.

Table A1.

Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS) ICD-10 Codes and Assigned Weights.

| ICD-10 Code |

Description |

Weight |

| A04 |

Other bacterial intestinal infections |

1.1 |

| A09 |

Diarrhea and gastroenteritis of presumed infectious origin |

1.1 |

| A41 |

Other septicemia |

1.6 |

| B95 |

Streptococcus and staphylococcus as cause of diseases classified to other chapters |

1.7 |

| B96 |

Other bacterial agents as cause of diseases classified to other chapters (secondary code) |

2.9 |

| D64 |

Other anemias |

0.4 |

| E05 |

Thyrotoxicosis [hyperthyroidism] |

0.9 |

| E16 |

Other disorders of pancreatic internal secretion |

1.4 |

| E53 |

Deficiency of other B group vitamins |

1.9 |

| E55 |

Vitamin D deficiency |

1 |

| E83 |

Disorders of mineral metabolism |

0.4 |

| E86 |

Volume depletion |

2.3 |

| E87 |

Other disorders of fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance |

2.3 |

| F00 |

Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease |

7.1 |

| F01 |

Vascular dementia |

2 |

| F03 |

Unspecified dementia |

2.1 |

| F05 |

Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances |

3.2 |

| F10 |

Mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol |

0.7 |

| F32 |

Depressive episode |

0.5 |

| G20 |

Parkinson’s disease |

1.8 |

| G30 |

Alzheimer’s disease |

4 |

| G31 |

Other degenerative diseases of nervous system, not elsewhere classified |

1.2 |

| G40 |

Epilepsy |

1.5 |

| G45 |

Transient cerebral ischemic attacks and related syndromes |

1.2 |

| G81 |

Hemiplegia |

4.4 |

| H54 |

Blindness and low vision |

1.9 |

| H91 |

Other hearing loss |

0.9 |

| I63 |

Cerebral infarction |

0.8 |

| I67 |

Other cerebrovascular diseases |

2.6 |

| I69 |

Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease (secondary codes) |

3.7 |

| I95 |

Hypotension |

1.6 |

| J18 |

Pneumonia, organism unspecified |

1.1 |

| J22 |

Unspecified acute lower respiratory infection |

0.7 |

| J69 |

Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids |

1 |

| J96 |

Respiratory failure, not elsewhere classified |

1.5 |

| K26 |

Duodenal ulcer |

1.6 |

| K52 |

Other noninfective gastroenteritis and colitis |

0.3 |

| K59 |

Other functional intestinal disorders |

1.8 |

| K92 |

Other diseases of digestive system |

0.8 |

| L03 |

Cellulitis |

2 |

| L08 |

Other local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue |

0.4 |

| L89 |

Decubitus ulcer |

1.7 |

| L97 |

Ulcer of lower limb, not elsewhere classified |

1.6 |

| M15 |

Polyarthrosis |

0.4 |

| M19 |

Other arthrosis |

1.5 |

| M25 |

Other joint disorders, not elsewhere classified |

2.3 |

| M41 |

Scoliosis |

0.9 |

| M48 |

Spinal stenosis (secondary code only) |

0.5 |

| M79 |

Other soft tissue disorders, not elsewhere classified |

1.1 |

| M80 |

Osteoporosis with pathological fracture |

0.8 |

| M81 |

Osteoporosis without pathological fracture |

1.4 |

| N17 |

Acute renal failure |

1.8 |

| N18 |

Chronic renal failure |

1.4 |

| N19 |

Unspecified renal failure |

1.6 |

| N20 |

Calculus of kidney and ureter |

0.7 |

| N28 |

Other disorders of kidney and ureter, not elsewhere classified |

1.3 |

| N39 |

Other disorders of urinary system (includes UTI and incontinence) |

3.2 |

| R00 |

Abnormalities of heartbeat |

0.7 |

| R02 |

Gangrene, not elsewhere classified |

1 |

| R11 |

Nausea and vomiting |

0.3 |

| R13 |

Dysphagia |

0.8 |

| R26 |

Abnormalities of gait and mobility |

2.6 |

| R29 |

Other symptoms and signs involving the nervous and musculoskeletal systems |

3.6 |

| R31 |

Unspecified hematuria |

3 |

| R32 |

Unspecified urinary incontinence |

1.2 |

| R33 |

Retention of urine |

1.3 |

| R40 |

Somnolence, stupor and coma |

2.5 |

| R41 |

Other symptoms and signs involving cognitive functions and awareness |

2.7 |

| R44 |

Other symptoms and signs involving general sensations and perceptions |

1.6 |

| R45 |

Symptoms and signs involving emotional state |

1.2 |

| R47 |

Speech disturbances, not elsewhere classified |

1 |

| R50 |

Fever of unknown origin |

0.1 |

| R54 |

Senility |

2.2 |

| R56 |

Convulsions, not elsewhere classified |

2.6 |

| R63 |

Symptoms and signs concerning food and fluid intake |

0.9 |

| R69 |

Unknown and unspecified causes of morbidity |

1.3 |

| S00 |

Superficial injury of head |

3.2 |

| S01 |

Open wound of head |

1.1 |

| S06 |

Intracranial injury |

2.4 |

| S09 |

Other and unspecified injuries of head |

1.2 |

| S22 |

Fracture of rib(s), sternum and thoracic spine |

1.8 |

| S32 |

Fracture of lumbar spine and pelvis |

1.4 |

| S42 |

Fracture of shoulder and upper arm |

2.3 |

| S51 |

Open wound of forearm |

0.5 |

| S72 |

Fracture of femur |

1.4 |

| S80 |

Superficial injury of lower leg |

2 |

| W01 |

Fall on same level from slipping, tripping and stumbling |

0.9 |

| W06 |

Fall involving bed |

1.1 |

| W10 |

Fall on and from stairs and steps |

0.9 |

| W18 |

Other fall on same level |

2.1 |

| W19 |

Unspecified fall |

3.2 |

| X59 |

Exposure to unspecified factor |

1.5 |

| Y84 |

Other medical procedures as cause of abnormal reaction of patient |

0.7 |

| Y95 |

Nosocomial condition |

1.2 |

| Z06 |

Agent resistant to penicillin and related antibiotics |

0.8 |

| Z50 |

Care involving use of rehabilitation procedures |

2.1 |

| Z60 |

Problems related to social environment |

1.8 |

| Z73 |

Problems related to life-management difficulty |

0.6 |

| Z74 |

Problems related to care-provider dependency |

1.1 |

| Z75 |

Problems related to medical facilities and other health care |

2 |

| Z87 |

Personal history of other diseases and conditions |

1.5 |

| Z91 |

Personal history of risk-factors, not elsewhere classified |

0.5 |

| Z93 |

Artificial opening status |

1 |

| Z99 |

Dependence on enabling machines and devices |

0.8 |

References

- Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775–1782. [CrossRef]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ejaz, A.; Spolverato, G.; et al. A prognostic nomogram for cholangiocarcinoma: a SEER database analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2016, 18, 731–738. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. [CrossRef]

- Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–908. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Chaudhry, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Health care utilization and cost among older adults with cancer: role of frailty and functional status. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).