1. Introduction

Preterm birth represents a critical challenge in neonatology, as these infants experience a highly vulnerable period of development outside the womb. Ensuring adequate postnatal growth and neurological development is essential, as suboptimal growth trajectories have been linked to adverse long-term outcomes, including increased risks for metabolic disorders and impaired cognitive function [

1,

2]. Despite advances in neonatal care, extrauterine growth restriction remains common, particularly in very low birth weight infants, due to accumulated nutritional deficits [

3]. While traditional fortification strategies aim to improve nutrient intake, they often fail to meet the individual requirements of preterm infants, potentially affecting both short- and long-term outcomes.

The human brain undergoes a significant growth spurt from mid-gestation to two years postnatally, with critical microstructural processes such as oligodendrocyte differentiation and axonal growth occurring in the third trimester of pregnancy [

4]. Preterm infants miss this critical in-utero phase, placing them at risk for suboptimal brain development. Adequate macronutrient intake, particularly protein, is crucial to supporting this rapid neurological maturation. Evidence suggests that a higher intake of macronutrients and fat-free mass gain is associated with improved neurological outcomes, whereas excessive fat mass gain may not have the same benefits [

5,

6].

Breast milk is the preferred source of nutrition for preterm infants due to its immunological and developmental benefits, including bioactive growth factors, phospholipids, and probiotics [

7,

8]. However, its macronutrient composition is highly variable, fluctuating based on maternal factors, lactation stage, and time of day [

9]. Standard fortification (SF), the most widely used fortification strategy, involves adding fixed doses of commercial fortifiers to breast milk. However, SF does not account for individual macronutrient variations, leading to inconsistent nutrient intake and persistent growth deficits, with up to 58% of preterm infants experiencing postnatal growth restriction despite fortification [

10]. Other individualized fortification methods, such as adjustable fortification attempt to mitigate the deficits of SF by modifying protein intake based on infant’s metabolic markers, such as blood urea nitrogen. However, this still lacks direct measurement of actual macronutrient intake leading to reactive rather than proactive adjustments [

11]. As a result, both standard and adjustable fortification may allow nutritional deficits to accumulate before they are recognized and corrected, potentially compromising early growth and development.

Target fortification (TFO) is an individualized fortification method that offers a more precise approach by measuring macronutrient levels in breast milk and adjusting protein, fat, and carbohydrate supplementation accordingly. This method aligns nutrient intake with recommendations of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) [

12] and reduces nutrient variability across feedings. Unlike SF or adjustable fortification, TFO ensures that each infant receives optimized nutrition rather than milk with an unpredictable composition. Our previous research has demonstrated that TFO leads to improved weight gain, growth velocity, and metabolic parameters while reducing feeding intolerance [

13]. However, its impact on long-term neurological development had not been examined.

This study aims to evaluate the effects of TFO compared to SF on growth, body composition, and neurological outcomes at 18 months corrected age. Specifically, it investigates whether TFO results in higher Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III (BSID-III) scores, improved weight and length gain, and better body composition at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). By reducing macronutrient variability and preventing cumulative nutrient deficits, we hypothesize that TFO will enhance both short-term growth and long-term neurological outcomes. The findings of this study could provide crucial insights into optimizing neonatal nutrition and improving the developmental trajectory of preterm infants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, single-center, double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in a Level III neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (McMaster Children's Hospital, Hamilton, ON, Canada) from January 2012 to December 2016. This nutritional study includes the analysis of both short-term and long-term treatment outcomes. The analysis of short-term outcomes has already been published [

13]. The present study examines the neurological development of preterm infants at 18 months corrected age as a long-term follow-up outcome. For the study population assessed using the BSID-III, the short-term outcomes were reanalyzed. Preterm infants were fed either standard-fortified or target-fortified human milk. The control group was defined as the group receiving only SF, while the intervention group received SF plus TFO. The local ethics committee approved the study (Hamilton Integrated Research Ethic Board, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada; Reference No. 12-109) and the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01609894. Informed written consent was obtained from both parents.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Infants eligible for this study were those born at a gestational age of < 32 weeks, as determined by maternal records or early fetal ultrasound. To be included, they had to have an enteral intake of ≥ 100 mL/kg/d for ≥ 24 hours. Additionally, the intervention was required to last for ≥ 3 consecutive weeks after achieving full enteral feeding, defined as a daily intake of ≥ 150 mL/kg. In the case of multiple births, each infant meeting the inclusion criteria was included in the study, with siblings randomized individually to one of the study arms.

Infants were excluded if they presented with intrauterine growth restriction or were classified as small for gestational age, defined by a birth weight below the 3rd percentile according to sex-specific reference data [

14]. Those with gastrointestinal malformations, severe congenital anomalies, or chromosomal abnormalities were not eligible. Conditions such as enterostomy, short bowel syndrome, or prolonged fluid restrictions (<140 mL/kg/d for ≥3 consecutive days) led to exclusion. Infants receiving ≥ 25% of their caloric intake from formula over a one-week period were also excluded. Medical conditions such as gram-negative sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC, Bell stage 2 or 3), kidney disease with symptoms such as oliguria, anuria, proteinuria, or hematuria, alongside elevated creatinine levels (≥ 130 mmol/L) [

15] or blood urea nitrogen levels (≥ 10 mmol/L) [

16], and liver dysfunction defined by jaundice (direct bilirubin level > 1.0 mg/dL) with abnormal liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, or gamma-glutamyl transferase) met exclusion criteria. Participation in another clinical trial that could influence study outcomes or a high likelihood of transfer to another NICU or Level II pediatric unit outside McMaster Children’s Hospital also resulted in exclusion.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

Randomization was stratified by gestational age (< 28 weeks; ≥ 28 weeks) in blocks of varying sizes (2, 4, and 6) to minimize allocation bias. A series of opaque, sealed, consecutively numbered envelopes was prepared for each stratum and opened by dietitians in their offices outside the NICU. Apart from the dietitians, all study personnel were blinded to the randomization and nutritional intervention. The fortification prescription was determined by attending physicians in both study arms. The added modular components did not alter the appearance of the milk [

13].

2.4. Measurement of Nutrient Concentration in Native Human Milk

Native human milk was pooled in 24-hour batches, and 2.5 mL samples were collected. Before analysis, the samples were homogenized for 15 seconds using an ultrasonic disintegrator (VCX 130; Chemical Instruments AB, Sollentuna, Sweden). Osmolality was measured in both native and fortified human milk using an osmometer (3320 MicroOsmometer; Advanced Instruments, Norwood, Massachusetts). Macronutrient analysis was conducted three times per week using a calibrated and validated near-infrared bedside milk analyzer (SpectraStar; Unity Scientific, Brookfield, Connecticut) [

17,

18,

19].

To calculate actual daily intake for data analysis, nutrient content was measured before fortification in all batches from both study arms. Protein and fat content were analyzed using the validated near-infrared bedside milk analyzer, while lactose content was determined using an established ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry reference method [

20]. Enteral feeding volume was recorded daily to calculate total fluid and macronutrient intake. A chemical analysis was performed on 10% of samples to validate the milk analyzer results.

2.5. Nutritional Standards of Study Groups

TFO was calculated and administered by trained dietitians using a standardized recipe for each macronutrient. Human milk analysis was conducted three times weekly, with previous values used on non-testing days [

13].

The fortifier used was a commercially available standard fortifier (Enfamil HMF®, Mead Johnson, Ohio), providing an additional 1 g fat, 1.1 g protein, and 0.4 g carbohydrates per 100 mL human milk, along with modular components for TFO: a polyunsaturated fat emulsion (0.5 g fat/mL; Microlipid, Nestlé HealthCare Nutrition, Minnesota), whey protein powder (0.86 g protein/g; Beneprotein, Nestlé HealthCare Nutrition, Minnesota), and glucose polymer powder (0.94 g carbohydrates/g; Polycal, Nutricia, UK). Infants receiving donor milk were supplemented with an additional 0.4 g whey protein powder per 100 mL (Beneprotein), following McMaster NICU guidelines.

In the SF and TFO groups, the standard fortifier was introduced gradually over two days once a total fluid intake of 120 mL/kg/d was achieved. Once the full SF concentration was reached in the TFO group, the modular components were gradually added over a period of three days. To prepare the target-fortified milk, SF was first added to native human milk in the recommended dosage. The modular components were then incorporated to meet the ESPGHAN-recommended intake levels of 4.4 g fat, 8.3 g carbohydrates, and 3.0 g protein per 100 mL, based on an average fluid intake of 150 mL/kg/d [

12]. Growth velocity was calculated from study day 2 after the complete introduction of TFO.

2.6. Assessment of Neurological Development

Neurological development was assessed at 18 months corrected age using the BSID-III. Cognitive, language (receptive and expressive), and motor (fine and gross motor) scales were analyzed based on US validation standards. Social-emotional and adaptive behavior scales were not included, as they rely on parental reports. The mean composite BSID-III score is 100 (standard deviation = 15). Children with BSID-III scores ≤ 85, ≤ 70, and ≤ 55 were categorized as having mild, moderate, or severe developmental delay, respectively. Assessments were conducted by trained child psychiatrists at McMaster Children's Hospital, with each test lasting approximately 90 minutes [

21].

2.7. Evaluation of Outcome Parameters

Weight gain velocity (g/kg/d) was measured during the first 21 days of intervention. Weight was recorded every other day to an accuracy of 10 g using an electronic scale. Additionally, macronutrient intake, nutritional efficiency, head circumference, crown-heel length, major morbidities, and metabolic parameters (blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, triglycerides) were assessed on days 7, 14, and 21. Neurological development at 18 months was correlated with these parameters.

Infants were stratified further into low-protein and high-protein groups within the control and intervention arms based on the projected protein intake after SF. This categorization aimed to better identify children at the highest risk for poor neurological development, particularly those in the low-protein group. The low-protein subgroup was calculated by analyzing the protein content of their native unfortified milk, and calculating the expected contribution from SF. Infants whose estimated protein intakes were below the median (3.5 g/kg/d) were classified as low-protein, and those with estimated protein intakes above as high-protein.

Nutritional efficiency (g/100 mL) was calculated as the ratio of daily weight gain (g/kg/d) to total fluid intake (mL/kg/d). Anthropometric measurements, including crown-heel length and front-occipital circumference, were recorded at admission and then weekly during the intervention period with an accuracy of 0.5 cm. Body composition, including fat mass and fat-free mass, was assessed at 36 weeks PMA before discharge or transfer using whole-body air displacement plethysmography (PEAPOD Infant Body Composition System, COSMED USA Inc., Concord, California, USA). Daily quality control checks were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All anthropometric and body composition measurements were conducted by two trained examiners [

13]. The study was performed at a tertiary centre leading to a 30% retro-transfer rate to local level 2 hospitals before 36 weeks PMA. As a result, secondary outcome measurements such as body composition and growth at 36 weeks were not available for transferred infants.

2.8. Quality Control

Good Clinical and Laboratory Practice (GCLP) standards were applied to all analytical point-of-care instruments (blood gas analyzer, osmometer, milk analyzer) [

22]. Daily quality controls were conducted for the near-infrared milk analyzer, and sample storage followed established protocols [

17].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The sample size calculations for this study were based on the expected short-term outcomes for the parameter of weight gain. The anticipated neurological treatment outcomes were not taken into account when determining the required sample size [

13]. Statistical analyses followed CONSORT guidelines [

23]. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean (standard deviation) or median (min-max) for continuous variables and count (%) for categorical variables. For the per-protocol analysis, only preterm infants who had received nutrition as specified in the study protocol for at least 14 days were included. The outcomes related to growth, body composition, nutritional parameters, and neurological development, as well as birth and study characteristics, were compared between groups (control vs. intervention and low-protein vs. high-protein groups) using t-tests. The means of nominally scaled control variables, such as the number of children with BSID-III scores ≤ 85 or ≤ 70, as well as maternal and perinatal risk factors, were analyzed for systematic differences between the control and intervention groups using the chi-square test. Logistic regression analyzed the relationship between baseline characteristics and outcomes, while linear mixed models assessed longitudinal associations between intervention groups, nutrition, and body composition. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05, using SPSS (v26; IBM, NY, USA) and R (v4.1.3; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment Process of Participants

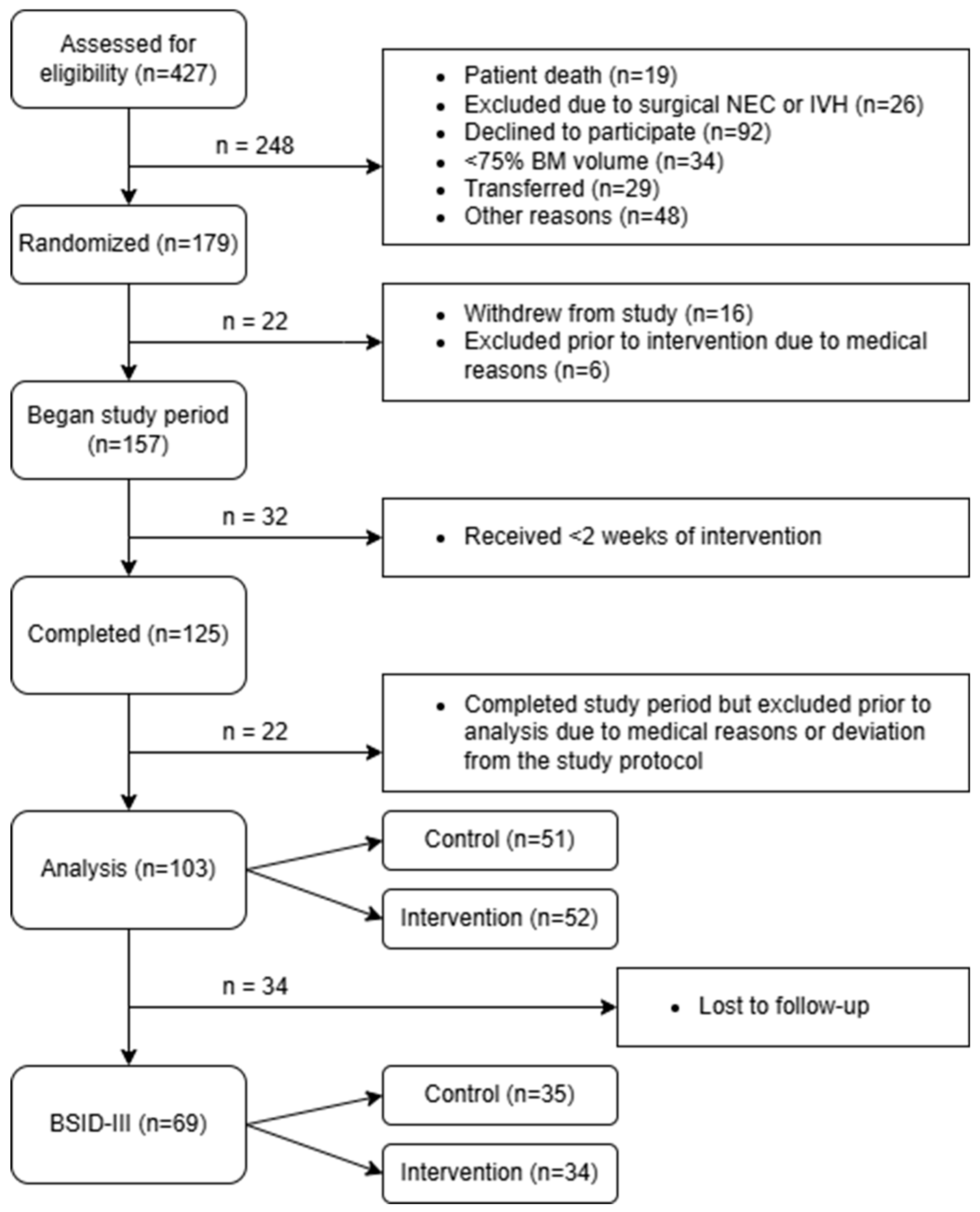

Of a total of 427 infants which were recruited, 103 preterm infants (control group: n = 51, intervention group: n = 52) completed the intervention according to the protocol and were included in the analysis [

13]. Among these 103 preterm infants, 69 underwent follow-up assessments using the BSID-III at 18 months corrected age (control group: n = 35, intervention group: n = 34) (

Figure 1).

3.2. Patient Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the participating preterm infants (

Table 1) showed no significant differences between the control and intervention groups, regardless of whether the analysis included all infants who completed the intervention (n=103), only those assessed with the BSID-III (n=69), or only those not assessed with the BSID-III (n=34). For these three populations, comparisons were made based on birth characteristics, including anthropometric data, sex, Apgar scores, gestational age at birth, and maternal age, as well as study-related characteristics such as PMA, days of life at study initiation, and duration of the intervention [

24]. Additionally, for infants assessed with the BSID-III, anthropometric data and age at the time of the BSID-III evaluation were compared.

Regarding pregnancy risk factors and severe morbidities in the NICU, no significant differences were found between groups, with two exceptions. Pregnancy-induced hypertension or preeclampsia was more common among mothers in the intervention group whose infants underwent BSID-III assessment. Additionally, feeding disorders were less prevalent in the intervention group among preterm infants who completed the intervention but were not assessed with the BSID-III (

Table 2).

3.3. Nutritional Characteristics

In the infants assessed with the BSID-III, there were no differences between intervention and control group regarding the fat, protein, and carbohydrate content of the analyzed native human milk. However, the intervention group had a significantly higher average intake of fat, carbohydrates, and protein, as well as a significantly higher protein-to-energy ratio (

Table 3).

Fat intake in both the control and intervention groups, at 7.1 ± 0.7 g/kg/d and 7.6 ± 0.7 g/kg/d, respectively, exceeded the ESPGHAN recommendation of 4.4–6.8 g/kg/d. Carbohydrate intake in the control group was slightly below the ESPGHAN recommendation (11.6–13.2 g/kg/d) at 10.8 ± 0.8 g/kg/d, while the intervention group slightly exceeded the recommendation at 13.6 ± 0.6 g/kg/d. Protein intake in the control and intervention groups, at 3.6 ± 0.3 g/kg/d and 4.5 ± 0.2 g/kg/d, respectively, was at the lower and upper limits of the ESPGHAN recommendation (3.5–4.5 g/kg/d).

In the subgroup analysis, the low-protein group in the control arm did not reach the recommended protein intake, with an average of 3.3 ± 0.2 g/kg/d, whereas the high-protein group in the control arm achieved the recommendation at 3.9 ± 0.2 g/kg/d. In the intervention group, protein intake for both the low- and high-protein subgroups was at the upper limit of the recommendation, with 4.5 ± 0.1 g/kg/d and 4.6 ± 0.2 g/kg/d, respectively.

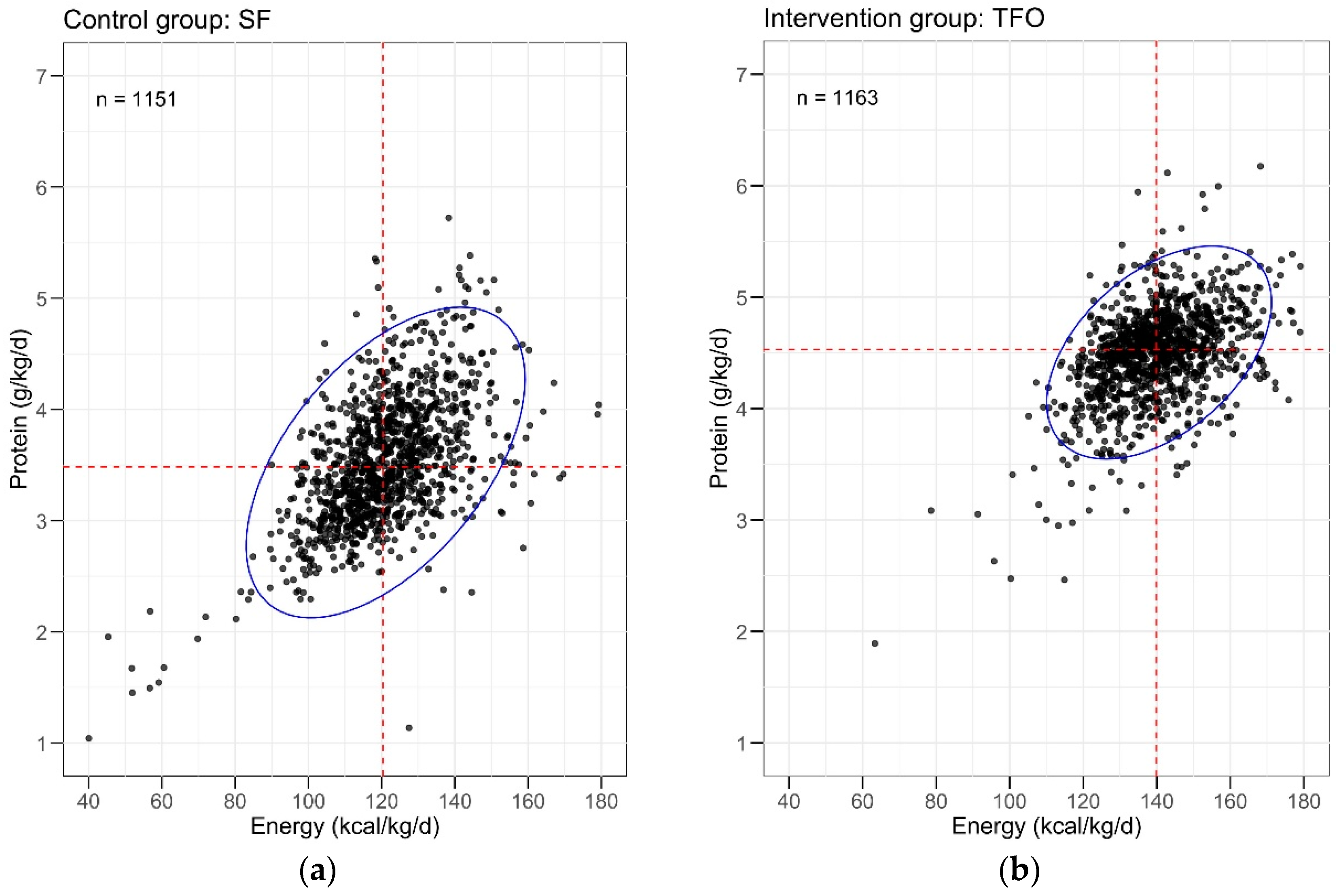

The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for protein and energy intake per kilogram and day were significantly smaller in the TFO group compared to the SF group (

Figure 2). TFO notably reduced macronutrient variability and minimized the number of extreme outliers with highly unbalanced nutritional composition.

3.4. Short-Term Effects of the Intervention

At 36 weeks PMA, body weight in the intervention group was significantly higher than in the control group (2,514 ± 289 g vs. 2,283 ± 332 g, mean difference [95% CI] of 231 g [81, 381], p < 0.01). Growth velocity during the first 21 days of the intervention (21.7 ± 2.3 g/kg/d vs. 19.2 ± 2.2 g/kg/d, mean difference [95% CI] of 2.5 g/kg/d [1.4, 3.6], p < 0.001) and nutritional efficiency (14.3 ± 1.7 g/dL vs. 12.4 ± 1.6 g/dL, mean difference [95% CI] of 1.9 g/dL [1.1, 2.2], p < 0.001) were also significantly higher in the intervention group.

In the subgroup with low native human milk protein content, TFO led to significantly improved growth (body weight 2,525 ± 283 g vs. 2,134 ± 277 g, mean difference [95% CI] of 391 g [203, 578], p < 0.001), while the weight difference in the high-protein subgroup was not significant.

Body composition measurements at 36 weeks PMA showed no significant differences in fat mass or fat-free mass between the control and intervention groups in the high-protein subgroup. However, in the TFO subgroup with low protein content, fat mass (610 ± 191 g vs. 451 ± 144 g, mean difference [95% CI] of 159 g [23, 295], p < 0.05) and fat-free mass (1,920 ± 183 g vs. 1,691 ± 240 g, mean difference [95% CI] of 229 g [54, 404], p < 0.05) were significantly higher (

Table 4).

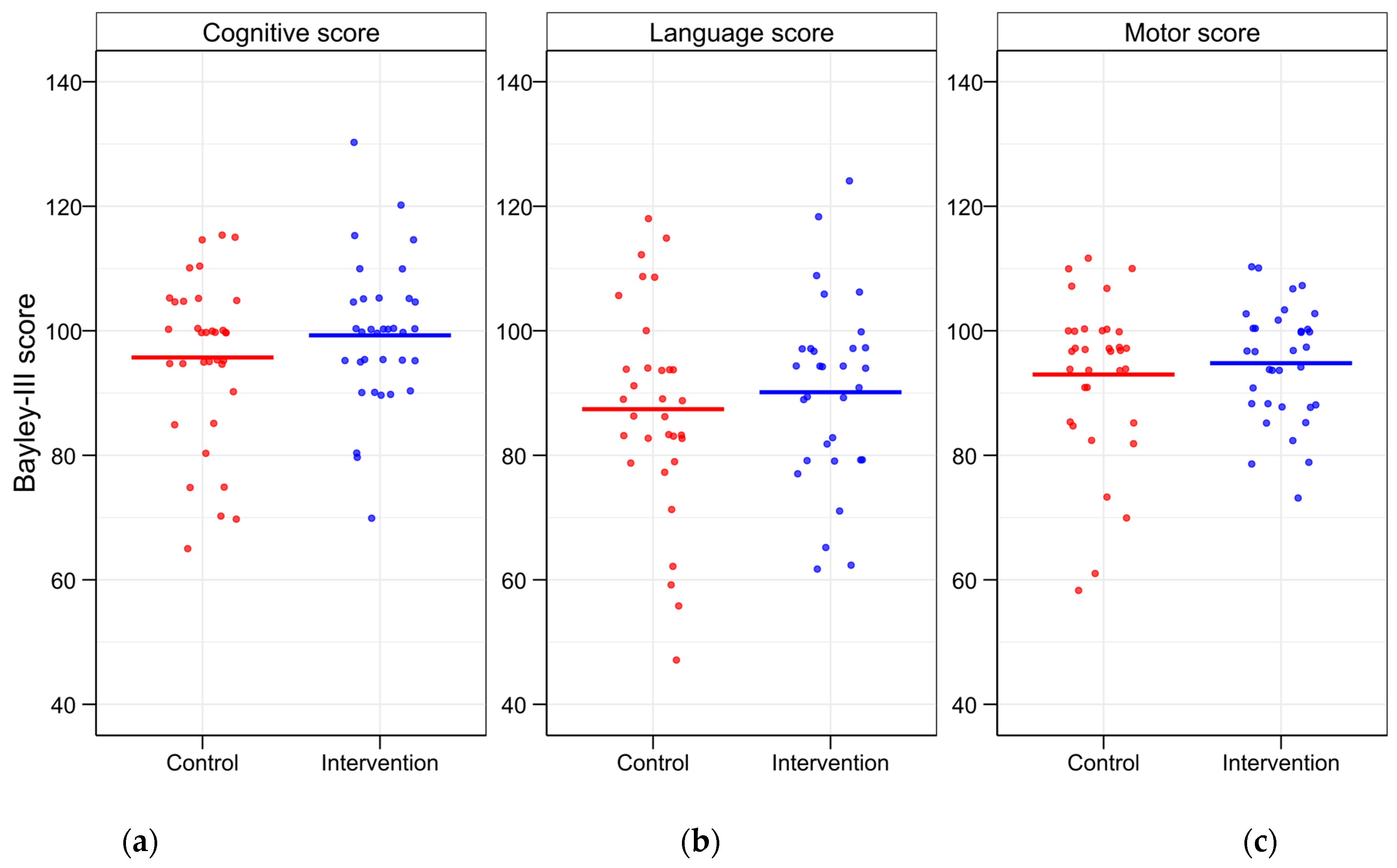

3.5. Evaluation of BSID-III Scores

Neurological development assessed using BSID-III at 18 months showed higher mean cognitive, language, and motor scores in the intervention group compared to the control group. However, none of these differences were statistically significant for the main BSID-III scales (

Table 5).

The highest cognitive BSID-III scores were observed in infants from the TFO subgroup with high protein content (102.5 ± 10.0), while the lowest cognitive scores (93.5 ± 15.9) were found in infants from the control group whose mothers had below-average human milk protein content. This difference was not statistically significant (

Table 5).

Comparing preterm infants in the low-protein and high-protein groups, regardless of study group, showed a weak trend toward better scores in the high-protein group, though statistical significance was not reached (

Table 5).

No significant differences were found within the low-protein subgroup. However, in the high-protein subgroup, the intervention group showed significantly higher scores in both the expressive and overall language scales than the control group (

Table 5).

The number of infants with scores ≤ 85 and ≤ 70 was lower in the TFO group across all categories (

Figure 3). The number of preterm infants with a motor BSID-III score of ≤ 70 was significantly lower in the intervention group compared to the control group (

Table 6). A score of ≤ 55 was observed in only one infant from the control group in the language scale.

3.6. Correlation Analyses of Growth and Neurological Development

Correlation analyses revealed that higher protein and lactose intake were significantly associated with increased growth velocity (p < 0.001). Fat intake had no impact on growth velocity.

Infants with a higher gestational age showed significantly better results across all three BSID-III scores, with cognitive scores reaching significance at p < 0.05 and language and motor scores at p < 0.01. Belonging to the intervention group or the high-protein group had a significant positive effect on cognitive scores (p < 0.05), while language and motor scores showed a positive trend, though not statistically significant.

Overall, a higher average total protein intake was associated with improved cognitive scores (p < 0.05). However, the reduced variability in protein intake during TFO compared to SF, as indicated by the standard deviation, had no significant effect on BSID-III scores. Gender as a confounding factor did not influence BSID-III scores.

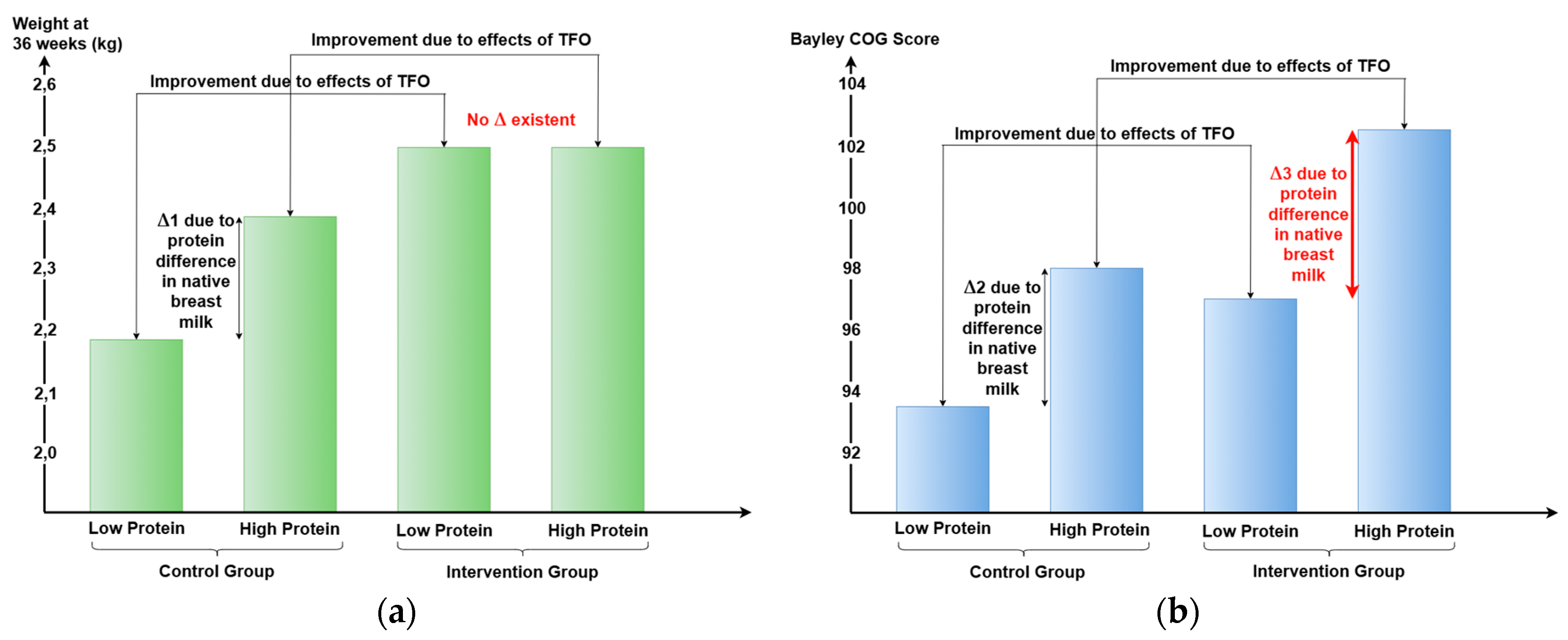

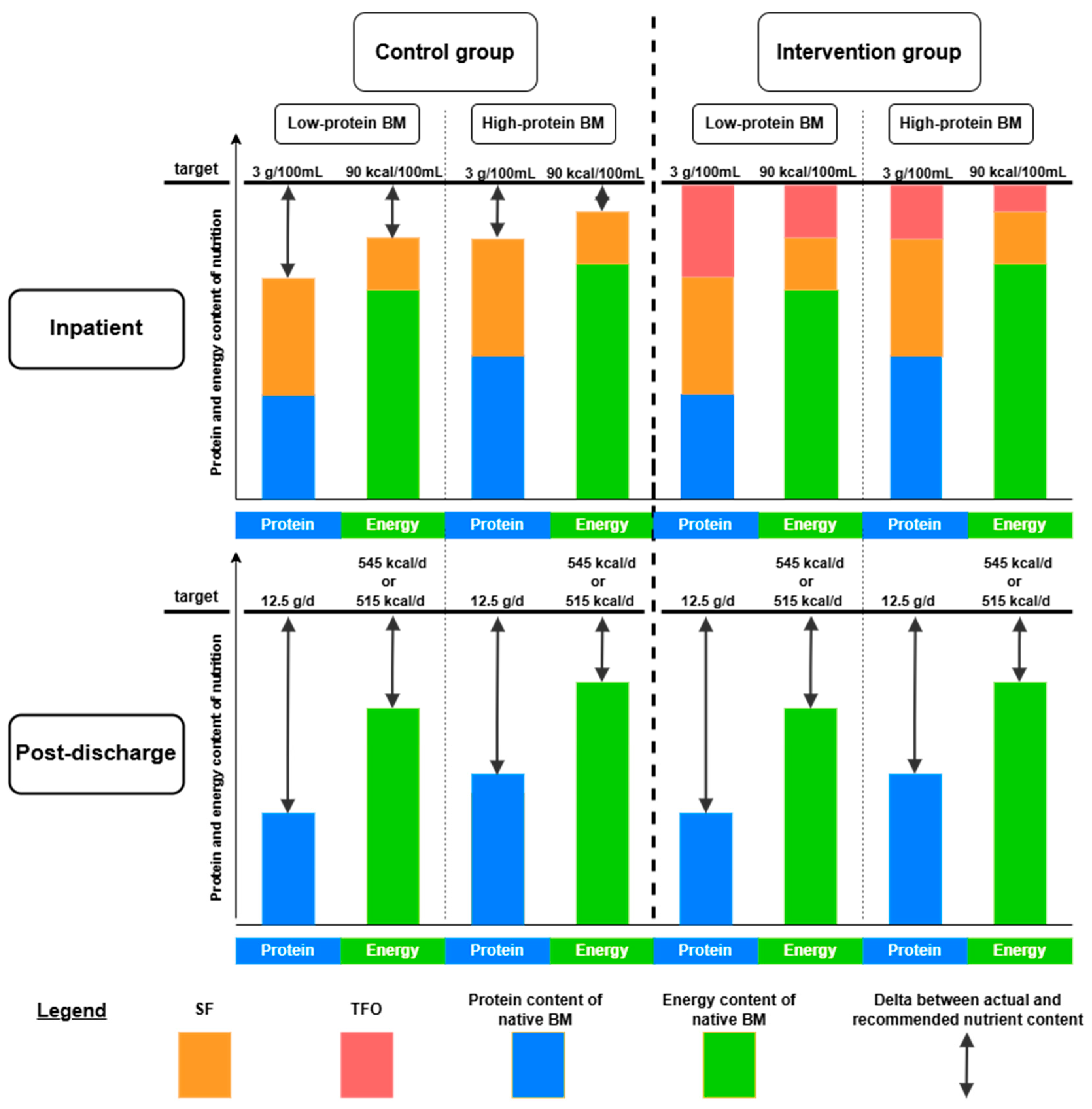

3.7. Differences Between Short- and Long-Term Outcomes

In the short term, TFO directly improved body weight, composition, and metabolic parameters by optimizing nutrient intake, particularly protein. Infants receiving SF had higher weights in the high-protein subgroup compared to the low-protein subgroup (see Δ1,

Figure 4a). In contrast, infants receiving TFO achieved similar weight gain regardless of native human milk protein content, indicating that TFO effectively corrected nutrient intake differences and met ESPGHAN recommendations. Thus, infants born to mothers with low human milk protein content benefited significantly from TFO in terms of growth.

For neurological long-term outcomes, infants whose mothers had low-protein human milk showed little improvement with TFO (see Δ2,

Figure 4b), while those receiving high-protein human milk exhibited greater developmental gains (see Δ3,

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

This follow-up study examines neurological development at 18 months corrected age in preterm infants (<30 weeks gestation) who participated in a double-blind RCT by Rochow et al. [

13]. In the original trial, infants received either target-fortified or standard-fortified human milk. The target-fortified milk was individually enriched, based on measurements of milk composition, with fat, protein, and carbohydrates using modular products, resulting in improved growth, body composition, metabolic parameters, and reduced neonatal morbidity at discharge [

13].

This study is the first to assess long-term neurological outcomes, showing a trend toward improvement across all BSID-III scales at 18 months.

4.1. Comparison with Previously Published TFO Studies

Few studies have investigated TFO in preterm infants, particularly its impact on neurological development. To date, in addition to Rochow et al. [

13], 16 studies on TFO have been published [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Five of these studies lacked an RCT design with a defined control group. Among them, one study fortified only protein, two studies fortified protein and fat, and two studies fortified all three macronutrients [

25,

28,

29,

34,

39].

Seven RCTs supplemented only protein in addition to SF [

27,

30,

31,

35,

36,

37,

38]. These studies reported mixed results, ranging from no improvements in growth parameters to significantly improved growth. Growth velocities between 17.7 and 25.7 g/kg/d were achieved, compared to 21.7 g/kg/d in this study. Most studies showed increased protein intake and protein-to-energy ratio with TFO, but without a proportional increase in energy intake, suggesting additional protein was metabolized rather than used for growth.

One RCT, which fortified only protein in the intervention group, assessed neurological development at 24 months corrected age using BSID-III (n = 22) [

31]. This is the only TFO study that has published neurological development data. The intervention group had significantly higher cognitive and motor scores compared to the control group. The intervention group received modular protein fortification with a target of 4.5 g/kg/d. The control group received SF. No significant differences in growth velocity were observed, but preterm infants born before 27 weeks had significantly higher weight and length Z-scores and increased fat-free mass at 32 and 35 weeks PMA.

Another study investigating the neurological development of preterm infants after TFO was discontinued due to increased feeding intolerance in the intervention group [

40]. The authors suggested that the fortifier used lacked fat and increased osmolarity due to excessive modular fat supplementation. However, methodological concerns raise doubts about the study’s validity, including a high dropout rate, frequent issues with milk analyzers, and inconsistent baseline characteristics [

40]. In contrast, the present study found fewer cases of feeding intolerance with TFO (5 vs. 11 in the control group).

An RCT comparing low (3.8 g/kg/d) vs. high (4.3 g/kg/d) protein intake found no growth differences despite higher protein intake in the high-protein group [

32]. The blood urea nitrogen level in the high-protein group increased by 50%, indicating that excess protein was metabolized rather than used for growth, reinforcing the idea that energy intake was the limiting factor [

41]. Another RCT fortified all three macronutrients but only supplemented protein modularly and fat and carbohydrates in fixed combinations to increase energy intake. No significant differences were observed in macronutrient intake between the SF and TFO groups, leading to no significant growth differences [

33].

A study combining Adjustable Fortification with TFO found similar growth and nutrient intake between groups, possibly due to high blood urea nitrogen targets in the control group [

26,

42]. Additionally, only 25% of feedings consisted of human milk, and no infant was exclusively human milk-fed. Neurological outcomes at three years are still under investigation.

4.2. Interpretation of Results in the Scientific Context

TFO enabled macronutrient intake to align with ESPGHAN recommendations [

12]. With SF alone, 50% of infants would not have met the lower target of 3.5 g protein per kg per day. TFO precisely achieved the upper target for protein intake of 4.5 g/kg/d, while the mean protein intake in the SF group was 3.6 g/kg/d. TFO reduced macronutrient variability and minimized the number of extreme outliers in human milk composition, an effect that only adding extra protein to fortified human milk would not achieve.

Higher nutrient intake is linked to improved growth and a lower rate of extrauterine growth restriction [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. In this study, the intervention group had significantly greater protein, fat, carbohydrate, and energy intake, resulting in higher body weight, faster growth velocity, and improved nutritional efficiency [

13]. In the low-protein subgroup, both fat mass and fat-free mass were significantly higher with TFO.

TFO also led to better neurological outcomes, with BSID-III scores at 18 months showing higher cognitive, language, and motor scores in the intervention group, though not statistically significant. Subgroup analysis revealed a significant improvement in expressive language scores in the high-protein group (90.4 ± 6.2 vs. 83.4 ± 10.3, p < 0.05). Compared to SF, TFO resulted in fewer preterm infants with BSID-III scores ≤ 85 and ≤ 70 across all scales, with a statistically significant difference in motor scores ≤ 70. Additionally, the only infant with a score of ≤ 55 on the language scale was found in the control group. Previous studies confirm that early protein and energy intake positively correlate with improved BSID scores and brain volume [

49,

50]. Early fat intake is also associated with improved neurological outcomes [

51]. TFO allows us to identify infants at risk of neurological developmental delays while simultaneously addressing this risk, as the goal of TFO is not to achieve "superfortification" but rather to identify human milk samples with low macronutrient content and ensure that every feeding aligns with ESPGHAN recommendations by adding modular components.

Growth velocity appears to have a significant, possibly independent impact on neurological development. This study’s observed effect size aligns with previous research, with the intervention group achieving an average growth velocity of 21.7 g/kg/d. Studies on extremely low birth weight infants have linked faster in-hospital weight gain with lower incidences of BSID-II scores of mental and psychomotor development indices < 70 [

52]. The best neurological outcomes were linked to average growth rates of 21.2 g/kg/d from regaining birth weight until reaching 2,000 g. Faster weight gain from term to four months corrected age was also associated with better psychomotor development index scores [

5].

Recent research attributes improved neurological outcomes to increased fat-free mass [

6,

53], which is tied to optimized calorie and macronutrient intake [

54]. In this study, TFO significantly increased fat-free mass in the low-protein subgroup. Head circumference was also larger in this group (31.4 ± 1.4 cm vs. 30.6 ± 1.3 cm), a factor strongly correlated with brain size and cognitive outcomes [

5,

55,

56].

While most BSID-III scale differences between SF and TFO groups were not statistically significant, the study shows a clear trend favoring TFO. Given ongoing debates about p-values [

57], the lack of significance likely reflects the small sample size and large standard deviations rather than a lack of effect. These findings support the hypothesis that TFO optimizes nutrient intake and growth, contributing to improved neurological outcomes.

4.3. Differences Between Short- and Long-Term Outcomes

Short-term outcomes, such as body weight and composition at NICU discharge, differed from long-term neurological outcomes at 18 months corrected age. While short-term outcomes reflect in-hospital nutrition, long-term outcomes depend on both NICU and post-discharge nutrition.

TFO most benefited the low-protein group in terms of growth, as more protein was added to their human milk. However, this effect did not extend to neurological outcomes, suggesting that exposure to low-protein human milk before TFO initiation and after NICU discharge may have diminished its benefits.

During hospitalization, the protein and energy deficits in human milk are partially corrected by SF and completely balanced by TFO. However, after discharge, human milk can no longer be adequately fortified, leading to the reaccumulation of protein and energy deficits (

Figure 5).

The protein content of human milk naturally decreases over time [

9], but it remains unclear whether mothers with initially low-protein human milk continued to produce it after discharge. If so, TFO could help identify these mothers early, enabling individualized post-discharge fortification plans.

Previous studies adding fixed fortifiers to human milk post-discharge showed no clear benefits for weight gain or neurological development, likely because they did not account for variations in human milk macronutrient content [

59].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This is the first completed double-blind RCT evaluating neurological outcomes following individualized TFO of all three macronutrients. The findings have significant clinical implications, as TFO provides a feasible strategy to improve neurological development in preterm infants. The intervention resulted in better neurological outcomes, and TFO has proven practical both in this study and in previous research. Conducting three milk measurements per week represents a manageable cost-benefit ratio, adding 35–40 minutes of workload per infant weekly, which could be offset by improved outcomes and shorter hospital stays [

19].

Baseline characteristics, nutritional characteristics, and short-term treatment outcomes were reanalyzed for the subgroup of preterm infants who underwent BSID-III testing. The results were consistent with the short-term findings previously published from the initial RCT [

13]. Relevant confounding factors, such as maternal conditions and preterm morbidity, were assessed.

The sample size of the initial RCT was larger than most previous TFO studies, despite the study's complex design and higher workload.

Human milk analyzer are medical devices and adhering to GCLP and performing proper device validation were essential for accurate macronutrient measurement. A multicenter quality initiative has shown that measurement errors can have clinical consequences [

60]. Safety was ensured through daily quality controls, which must also be maintained in other institutions implementing TFO.

A limitation of this study was the relatively small sample size due to high dropout rates at follow-up, with only 67% of infants from the initial study participating in BSID-III evaluation. Recruiting larger samples at a single hospital is challenging due to eligibility constraints, staff workload, and the long-term commitment required from parents. Additionally, approximately half of the infants had unexpectedly high protein levels in their native human milk, affecting results and necessitating subgroup analysis.

Despite TFO, macronutrient variability was not completely eliminated because milk measurements and fortification adjustments were conducted three times per week instead of daily, and for some macronutrients, particularly fat, the ESPGHAN upper limits were already exceeded after adding SF, resulting in occasional overfortification.

TFO was applied for an average of 29 days, starting on day 24 of life, meaning early nutrient deficits [

3] could not be fully corrected, though further deficiencies were prevented.

Since this was the first RCT investigating TFO in preterm infants, ensuring safety and good tolerability was a priority. The study confirmed that TFO is safe and feasible in clinical practice. Extending the duration of TFO and implementing it earlier after birth could potentially enhance its benefits, which should be explored in future studies.

Post-discharge nutrition remains unknown, as no data were collected, and fortifiers were not routinely provided to parents. Given that rapid brain growth continues until the second year of life, future studies should track post-discharge intake, especially in infants receiving low-protein human milk.

BSID-III scores at 18 months provide only a moderate prediction of actual long-term cognitive abilities [

61]. However, they remain the most widely used method for assessing preterm neurological development. Testing at 18 months allows for comparability between studies. Future research should explore TFO’s impact on neurological outcomes at school age. While confounding factors such as gestational age, birth weight, sex, and neonatal diseases were controlled, maternal education, age, and socioeconomic factors were not analyzed. These should be considered in future studies, as they may influence neurological development [

62,

63].

5. Conclusions

TFO ensures that preterm infants receive balanced nutrition by measuring all three macronutrients in human milk and adding protein, fat, and carbohydrates as needed. Compared to the control group, the intervention group achieved significantly higher intakes of these macronutrients, a higher protein-to-energy ratio, greater body weight at 36 weeks, and faster growth velocity.

Subgroup analysis showed that preterm infants receiving low-protein human milk had significantly higher fat-free mass with TFO. A trend toward improved neurological development was observed, with significantly better outcomes in the BSID-III language scale and fewer infants at risk of neurological disorders. The number of preterm infants with a motor BSID-III score of ≤ 70 was significantly lower in the intervention group, though differences in overall BSID-III scores were not statistically significant.

TFO’s effects may differ between short- and long-term outcomes, potentially due to post-NICU feeding with low-protein human milk. Identifying at-risk infants and optimizing post-discharge nutrition is crucial.

TFO is a promising approach to improving neurological development and reducing the risk of cognitive developmental delays. Multicenter studies are needed to increase the statistical power of the data and fully evaluate the potential of TFO.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R., G.F., C.F.; methodology, N.R., N.L., G.F., C.F.; validation, N.R., N.L., G.F., C.F.; formal analysis, N.R., N.L., A.B., A.A., G.F.; resources, S.E., C.F.; data curation, A.B., A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R., N.L., G.A.W., A.A., C.F.; writing—review and editing, N.R., N.L., G.A.W., A.A., C.F.; visualization, N.R., N.L., A.B., A.A.; supervision, N.R., J.D., C.F.; project administration, N.R., A.B., A.A.; funding acquisition, N.R., C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, #MOP-125883.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HiREB, #12-109).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is unavailable due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BM |

Breast milk |

| BPD |

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| BSID-III |

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| ESPGHAN |

European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition |

| GCLP |

Good Clinical and Laboratory Practice |

| IVH |

Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| NEC |

Necrotizing enterocolitis |

| NICU |

Neonatal intensive care unit |

| PDA |

Patent ductus arteriosus |

| PMA |

Postmenstrual age |

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| SF |

Standard fortification |

| TFO |

Target fortification |

References

- Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Dusick, A.M.; Vohr, B.R.; Wright, L.L.; Wrage, L.A.; Poole, W.K. For the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Growth in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Influences Neurodevelopmental and Growth Outcomes of Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.; Eriksson, J.; Forsén, T.; Osmond, C. Fetal Origins of Adult Disease: Strength of Effects and Biological Basis. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002, 31, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N.E.; Pang, N.; Cooke, R.J. Postnatal Malnutrition and Growth Retardation: An Inevitable Consequence of Current Recommendations in Preterm Infants? Pediatrics 2001, 107, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortinau, C.; Neil, J. The Neuroanatomy of Prematurity: Normal Brain Development and the Impact of Preterm Birth. Clinical Anatomy 2015, 28, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfort, M.B.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Sullivan, T.; Collins, C.T.; McPhee, A.J.; Ryan, P.; Kleinman, K.P.; Gillman, M.W.; Gibson, R.A.; Makrides, M. Infant Growth Before and After Term: Effects on Neurodevelopment in Preterm Infants. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e899–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramel, S.E.; Gray, H.L.; Christiansen, E.; Boys, C.; Georgieff, M.K.; Demerath, E.W. Greater Early Gains in Fat-Free Mass, but Not Fat Mass, Are Associated with Improved Neurodevelopment at 1 Year Corrected Age for Prematurity in Very Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants. The Journal of Pediatrics 2016, 173, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; Loret De Mola, C.; Victora, C.G. Long-term Consequences of Breastfeeding on Cholesterol, Obesity, Systolic Blood Pressure and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 2015, 104, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, M.A. Human Milk for the Premature Infant. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2013, 60, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidrewicz, D.A.; Fenton, T.R. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Nutrient Content of Preterm and Term Breast Milk. BMC Pediatr 2014, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, C.; Westerberg, A.C.; Rønnestad, A.; Nakstad, B.; Veierød, M.B.; Drevon, C.A.; Iversen, P.O. Growth and Nutrient Intake among Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants Fed Fortified Human Milk during Hospitalisation. Br J Nutr 2009, 102, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanoglu, S.; Moro, G.E.; Ziegler, E.E. Adjustable Fortification of Human Milk Fed to Preterm Infants: Does It Make a Difference? J Perinatol 2006, 26, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostoni, C.; Buonocore, G.; Carnielli, V.; De Curtis, M.; Darmaun, D.; Decsi, T.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.; Fusch, C.; Genzel-Boroviczeny, O.; et al. Enteral Nutrient Supply for Preterm Infants: Commentary From the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. pediatr. gastroenterol. nutr. 2010, 50, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochow, N.; Fusch, G.; Ali, A.; Bhatia, A.; So, H.Y.; Iskander, R.; Chessell, L.; El Helou, S.; Fusch, C. Individualized Target Fortification of Breast Milk with Protein, Carbohydrates, and Fat for Preterm Infants: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Nutrition 2021, 40, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, M.; Rochow, N.; Straube, S.; Briese, V.; Olbertz, D.; Jorch, G. Birth Weight Percentile Charts Based on Daily Measurements for Very Preterm Male and Female Infants at the Age of 154–223 Days. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2010, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, H. Reference Ranges for Plasma Cystatin C and Creatinine Measurements in Premature Infants, Neonates, and Older Children. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2000, 82, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridout, E.; Melara, D.; Rottinghaus, S.; Thureen, P.J. Blood Urea Nitrogen Concentration as a Marker of Amino-Acid Intolerance in Neonates with Birthweight Less than 1250 g. J Perinatol 2005, 25, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, G.; Rochow, N.; Choi, A.; Fusch, S.; Poeschl, S.; Ubah, A.O.; Lee, S.-Y.; Raja, P.; Fusch, C. Rapid Measurement of Macronutrients in Breast Milk: How Reliable Are Infrared Milk Analyzers? Clinical Nutrition 2015, 34, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrri, G.; Fusch, G.; Kwan, C.; Choi, D.; Choi, A.; Al Kafi, N.; Rochow, N.; Fusch, C. Validation of Correction Algorithms for Near-IR Analysis of Human Milk in an Independent Sample Set—Effect of Pasteurization. Nutrients 2016, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochow, N.; Fusch, G.; Zapanta, B.; Ali, A.; Barui, S.; Fusch, C. Target Fortification of Breast Milk: How Often Should Milk Analysis Be Done? Nutrients 2015, 7, 2297–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, G.; Choi, A.; Rochow, N.; Fusch, C. Quantification of Lactose Content in Human and Cow’s Milk Using UPLC–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 2011, 879, 3759–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Smith, M.M.; Spittle, A.J.; Lee, K.J.; Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J. Bayley-III Cognitive and Language Scales in Preterm Children. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e1258–e1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP). 2009, 22.

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. ; for the CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332–c332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apgar, V. A Proposal for a New Method of Evaluation of the Newborn Infant. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2015, 120, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochow, N.; Fusch, G.; Choi, A.; Chessell, L.; Elliott, L.; McDonald, K.; Kuiper, E.; Purcha, M.; Turner, S.; Chan, E.; et al. Target Fortification of Breast Milk with Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates for Preterm Infants. The Journal of Pediatrics 2013, 163, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brion, L.P.; Rosenfeld, C.R.; Heyne, R.; Brown, L.S.; Lair, C.S.; Petrosyan, E.; Jacob, T.; Caraig, M.; Burchfield, P.J. Optimizing Individual Nutrition in Preterm Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. J Perinatol 2020, 40, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, O.; Coban, A.; Uzunhan, O.; Ince, Z. Effects of Targeted Versus Adjustable Protein Fortification of Breast Milk on Early Growth in Very Low-Birth-Weight Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nut in Clin Prac 2020, 35, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.; Virella, D.; Papoila, A.L.; Alves, M.; Macedo, I.; E Silva, D.; Pereira-da-Silva, L. Individualized Fortification Based on Measured Macronutrient Content of Human Milk Improves Growth and Body Composition in Infants Born Less than 33 Weeks: A Mixed-Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Halleux, V.; Rigo, J. Variability in Human Milk Composition: Benefit of Individualized Fortification in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 98, 529S–535S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadıoğlu Şimşek, G.; Alyamaç Dizdar, E.; Arayıcı, S.; Canpolat, F.E.; Sarı, F.N.; Uraş, N.; Oguz, S.S. Comparison of the Effect of Three Different Fortification Methods on Growth of Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Breastfeeding Medicine 2019, 14, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaira, S.; Pert, A.; Farrell, E.; Sibley, C.; Harvey-Wilkes, K.; Nielsen, H.C.; Volpe, M.V. Expressed Breast Milk Analysis: Role of Individualized Protein Fortification to Avoid Protein Deficit After Preterm Birth and Improve Infant Outcomes. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 9, 652038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C.; Mathes, M.; Bleeker, C.; Vek, J.; Bernhard, W.; Wiechers, C.; Peter, A.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Effect of Increased Enteral Protein Intake on Growth in Human Milk–Fed Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2017, 171, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, G.; Sherriff, J.; Hartmann, P.E.; Nathan, E.; Geddes, D.; Simmer, K. Comparing Different Methods of Human Breast Milk Fortification Using Measured v. Assumed Macronutrient Composition to Target Reference Growth: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Br J Nutr 2016, 115, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlacchi, L.; Mallardi, D.; Giannì, M.L.; Roggero, P.; Amato, O.; Piemontese, P.; Consonni, D.; Mosca, F. Is Targeted Fortification of Human Breast Milk an Optimal Nutrition Strategy for Preterm Infants? An Interventional Study. J Transl Med 2016, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olhager, E.; Danielsson, I.; Sauklyte, U.; Törnqvist, C. Different Feeding Regimens Were Not Associated with Variation in Body Composition in Preterm Infants. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2022, 35, 6403–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parat, S.; Raza, P.; Kamleh, M.; Super, D.; Groh-Wargo, S. Targeted Breast Milk Fortification for Very Low Birth Weight (VLBW) Infants: Nutritional Intake, Growth Outcome and Body Composition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polberger, S.; Räihä, N.C.R.; Juvonen, P.; Moro, G.E.; Minoli, I.; Warm, A. Individualized Protein Fortification of Human Milk for Preterm Infants: Comparison of Ultrafiltrated Human Milk Protein and a Bovine Whey Fortifier. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 1999, 29, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, M.; Wang, D.; Gou, L.; Sun, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Schibler, K.; Li, Z. Individualized Human Milk Fortification to Improve the Growth of Hospitalized Preterm Infants. Nut in Clin Prac 2020, 35, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reali, A.; Greco, F.; Marongiu, G.; Deidda, F.; Atzeni, S.; Campus, R.; Dessì, A.; Fanos, V. Individualized Fortification of Breast Milk in 41 Extremely Low Birth Weight (ELBW) Preterm Infants. Clinica Chimica Acta 2015, 451, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliga-Siwecka, J.; Fiałkowska, J.; Chmielewska, A. Effect of Targeted vs. Standard Fortification of Breast Milk on Growth and Development of Preterm Infants (≤32 Weeks): Results from an Interrupted Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, S.; Ohira-Kist, K.; Abildskov, K.; Towers, H.M.; Sahni, R.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Schulze, K. Effects of Quality of Energy Intake on Growth and Metabolic Response of Enterally Fed Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Pediatr Res 2001, 50, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N.D.; Cooke, R.J. Protein Requirements in Preterm Infants: Effect of Different Levels of Protein Intake on Growth and Body Composition. Pediatr Res 2005, 58, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormack, B.E.; Bloomfield, F.H. Increased Protein Intake Decreases Postnatal Growth Faltering in ELBW Babies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2013, 98, F399–F404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, A.; Nieto, R.M.; Solana, C.L.; Perez, G.P.; Otheguy, L.E.; Larguia, A.M. Early and Aggressive Nutritional Strategy (Parenteral and Enteral) Decreases Postnatal Growth Failure in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. J Perinatol 2006, 26, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, L.; Cota, F.; Gallini, F.; Lauriola, V.; Zecca, C.; Romagnoli, C. Effects of High versus Standard Early Protein Intake on Growth of Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. J. pediatr. gastroenterol. nutr. 2007, 44, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauls, J.; Bauer, K.; Versmold, H. Postnatal Body Weight Curves for Infants below 1000 g Birth Weight Receiving Early Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition. Eur J Pediatr 1998, 157, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.M.; Cai, W.; Cao, Y.; Fang, B.H.; Feng, Y. Extrauterine Growth Retardation in Premature Infants in Shanghai: A Multicenter Retrospective Review. Eur J Pediatr 2009, 168, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.C.; Cairns, P.; Halliday, H.L.; Reid, M.; McClure, G.; Dodge, J.A. Randomised Controlled Trial of an Aggressive Nutritional Regimen in Sick Very Low Birthweight Infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 1997, 77, F4–F11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, B.E.; Walden, R.V.; Gargus, R.A.; Tucker, R.; McKinley, L.; Mance, M.; Nye, J.; Vohr, B.R. First-Week Protein and Energy Intakes Are Associated With 18-Month Developmental Outcomes in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, P.E.; Claessens, N.H.P.; Makropoulos, A.; Groenendaal, F.; De Vries, L.S.; Counsell, S.J.; Benders, M.J.N.L. Increase in Brain Volumes after Implementation of a Nutrition Regimen in Infants Born Extremely Preterm. The Journal of Pediatrics 2020, 223, 57–63.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleni Dit Trolli, S.; Kermorvant-Duchemin, E.; Huon, C.; Bremond-Gignac, D.; Lapillonne, A. Early Lipid Supply and Neurological Development at One Year in Very Low Birth Weight (VLBW) Preterm Infants. Early Human Development 2012, 88, S25–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenkranz, R.A. Nutrition, Growth and Clinical Outcomes. In World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics; Koletzko, B., Poindexter, B., Uauy, R., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2014; Vol. 110, pp. 11–26 ISBN 978-3-318-02640-5.

- Pfister, K.M.; Zhang, L.; Miller, N.C.; Ingolfsland, E.C.; Demerath, E.W.; Ramel, S.E. Early Body Composition Changes Are Associated with Neurodevelopmental and Metabolic Outcomes at 4 Years of Age in Very Preterm Infants. Pediatr Res 2018, 84, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramel, S.E.; Haapala, J.; Super, J.; Boys, C.; Demerath, E.W. Nutrition, Illness and Body Composition in Very Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants: Implications for Nutritional Management and Neurocognitive Outcomes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.L.Y.; Hunt, R.W.; Anderson, P.J.; Howard, K.; Thompson, D.K.; Wang, H.X.; Bear, M.J.; Inder, T.E.; Doyle, L.W. Head Growth in Preterm Infants: Correlation With Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Neurodevelopmental Outcome. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e1534–e1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, V.; Griesmaier, E.; Pehböck-Walser, N.; Pupp-Peglow, U.; Kiechl-Kohlendorfer, U. Poor Postnatal Head Growth in Very Preterm Infants Is Associated with Impaired Neurodevelopment Outcome. Acta Paediatrica 2013, 102, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrhein, V.; Greenland, S.; McShane, B. Scientists Rise up against Statistical Significance. Nature 2019, 567, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF., W.H.O. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2003; ISBN 978-92-4-156221-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lapillonne, A. Feeding the Preterm Infant after Discharge. In World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics; Koletzko, B., Poindexter, B., Uauy, R., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2014; Vol. 110, pp. 264–277 ISBN 978-3-318-02640-5.

- Kwan, C.; Fusch, G.; Rochow, N.; Fusch, C.; Kwan, C.; Fusch, G.; Rochow, N.; el-Helou, S.; Belfort, M.; Festival, J.; et al. Milk Analysis Using Milk Analyzers in a Standardized Setting (MAMAS) Study: A Multicentre Quality Initiative. Clinical Nutrition 2020, 39, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, M.; Taylor, H.G.; Drotar, D.; Schluchter, M.; Cartar, L.; Wilson-Costello, D.; Klein, N.; Friedman, H.; Mercuri-Minich, N.; Morrow, M. Poor Predictive Validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for Cognitive Function of Extremely Low Birth Weight Children at School Age. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.G.; Houston, S.M.; Brito, N.H.; Bartsch, H.; Kan, E.; Kuperman, J.M.; Akshoomoff, N.; Amaral, D.G.; Bloss, C.S.; Libiger, O.; et al. Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.; Greene, M.; Patel, A.; Meier, P. Maternal Education Level Predicts Cognitive, Language, and Motor Outcome in Preterm Infants in the Second Year of Life. Amer J Perinatol 2016, 33, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).