Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Fungi in Plastic Degradation

2.1. Enhanced Substrate Penetration

2.2. Diverse Enzymatic Machinery

2.3. Adaptability to Diverse Environments

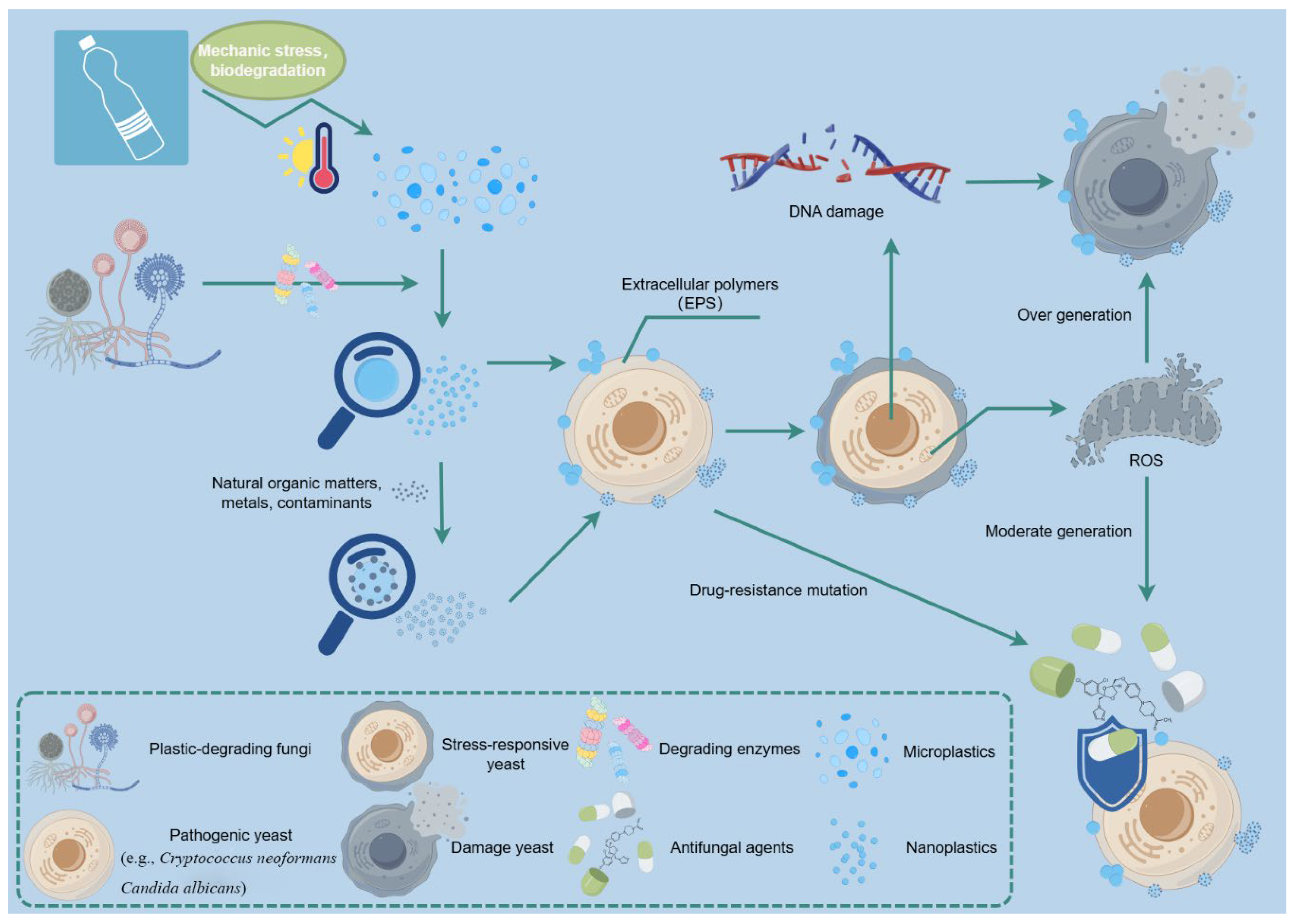

3. The Impact of Nanoplastics on Fungal Physiology and Pathogenicity

4. Potential Effects of Nanoplastics on Fungal Drug Resistance

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilcox, C.; Van Sebille, E.; Hardesty, B. D. Threat of plastic pollution to seabirds is global, pervasive, and increasing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 12(38), 11899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J. R.; Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science advances 2017, 3(7), e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseini, M.; Bond, T. Predicting the global environmental distribution of plastic polymers. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 2022, 300, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowger, W.; Willis, K. A.; Bullock, S.; Conlon, K.; Emmanuel, J.; Erdle, L. M.; Eriksen, M.; Farrelly, T. A.; Hardesty, B. D.; Kerge, K. Global producer responsibility for plastic pollution. Science advances 2024, 10(17), eadj8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, K. N.; Karapanagioti, H. K. Degradation of various plastics in the environment. Hazardous chemicals associated with plastics in the marine environment 2019, 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Hamidian, A. H.; Tubić, A.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J. K.; Wu, C.; Lam, P. K. Understanding plastic degradation and microplastic formation in the environment: A review. Environmental Pollution 2021, 274, 116554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; El Hadri, H.; Nguyen, B.; Grassl, B.; Rowenczyk, L.; Tufenkji, N.; Feng, S.; Wiesner, M. Nanoplastics are neither microplastics nor engineered nanoparticles. Nature nanotechnology 2021, 16(5), 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrano, D. M.; Wick, P.; Nowack, B. Placing nanoplastics in the context of global plastic pollution. Nature Nanotechnology 2021, 16(5), 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, A.; Yao, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Qu, J.; Wei, H.; Tang, J.; Chen, G. Polystyrene nanoplastics inhibit StAR expression by activating HIF-1α via ERK1/2 MAPK and AKT pathways in TM3 Leydig cells and testicular tissues of mice. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2023, 173, 113634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, W.; Yu, M.; Ma, X.; Shen, Z.; Ruan, J.; Qu, Y.; Huang, R.; Xue, P.; Ma, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhao, X. Gender-specific effects of prenatal polystyrene nanoparticle exposure on offspring lung development. Toxicology letters 2025, 407, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. O.; Abrantes, N.; Gonçalves, F. J. M.; Nogueira, H.; Marques, J. C.; Gonçalves, A. M. M. Impacts of plastic products used in daily life on the environment and human health: What is known? Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 2019, 72, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H. W.; Kim, D. H.; Jae, J.; Lam, S. S.; Park, E. D.; Park, Y. K. Recent advances in catalytic co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastic waste for the production of petroleum-like hydrocarbons. Bioresource technology 2020, 310, 123473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temporiti, M. E. E.; Nicola, L.; Nielsen, E.; Tosi, S. Fungal enzymes involved in plastics biodegradation. Microorganisms 2022, 10(6), 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S. S.; Ionescu, D.; Grossart, H.-P. Tapping into fungal potential: Biodegradation of plastic and rubber by potent Fungi. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 934, 173188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-K.; Gong, Z.; Wang, B.-T.; Hu, S.; Zhuo, Y.; Jin, C.-Z.; Jin, L.; Lee, H.-G.; Jin, F.-J. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene by mixed fungi composed of Alternaria sp. and Trametes sp. isolated from landfill sites. BMC microbiology 2024, 24(1), 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D. W. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegl, L.; Egger, M.; Boyer, J.; Hoenigl, M.; Krause, R. New treatment options for critically important WHO fungal priority pathogens. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaksmaa, A.; Polerecky, L.; Dombrowski, N.; Kienhuis, M. V.; Posthuma, I.; Gerritse, J.; Boekhout, T.; Niemann, H. Polyethylene degradation and assimilation by the marine yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. ISME communications 2023, 3(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A. R.; Costanzo, C. M.; Benham, R.; Loveridge, E. J.; Moody, S. C. Fungal bioremediation of polyethylene: Challenges and perspectives. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2022, 132(1), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Banerjee, S.; Biswas, C.; Guchhait, R.; Chatterjee, A.; Pramanick, K. Functional interplay between plastic polymers and microbes: a comprehensive review. Biodegradation 2021, 32(5), 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okal, E. J.; Heng, G.; Magige, E. A.; Khan, S.; Wu, S.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, T.; Mortimer, P. E.; Xu, J. Insights into the mechanisms involved in the fungal degradation of plastics. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2023, 262, 115202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, C. Fungal potential for the degradation of petroleum-based polymers: An overview of macro-and microplastics biodegradation. Biotechnology advances 2020, 40, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dix, N. J.; Webster, J.; Dix, N. J.; Webster, J. Fungi of extreme environments. Fungal ecology 1995, 322–340. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, E. Promising approaches towards biotransformation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with Ascomycota fungi. Current opinion in biotechnology 2016, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Khardenavis, A. A.; Purohit, H. J. Diverse metabolic capacities of fungi for bioremediation. Indian journal of microbiology 2016, 56(3), 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backa, S.; Gierer, J.; Reitberger, T.; Nilsson, T. Hydroxyl radical activity associated with the growth of white-rot fungi. 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L. A.; Robertson, P. K. Physico-chemical treatment methods for the removal of microcystins (cyanobacterial hepatotoxins) from potable waters. Chemical Society Reviews 1999, 28(4), 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Rice, J.; Martin, R.; Lindquist, E.; Lipzen, A.; Grigoriev, I.; Hibbett, D. Degradation of bunker C fuel oil by white-rot fungi in sawdust cultures suggests potential applications in bioremediation. PloS one 2015, 10(6), e0130381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I. F. Role of filamentous fungi to remove petroleum hydrocarbons from the environment. Microbial Action on Hydrocarbons 2018, 567–580. [Google Scholar]

- Mir-Tutusaus, J. A.; Baccar, R.; Caminal, G.; Sarrà, M. Can white-rot fungi be a real wastewater treatment alternative for organic micropollutants removal? A review. Water research 2018, 138, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odigbo, C.; Adenipekun, C.; Oladosu, I.; Ogunjobi, A. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) biodegradation by Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus pulmonarius. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195(5), 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Valdemar, R. M.; Turpin-Marion, S.; Delfín-Alcalá, I.; Vázquez-Morillas, A. Disposable diapers biodegradation by the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Waste management (New York, N.Y.) 2011, 31(8), 1683-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolski, E. A.; Durruty, I.; Haure, P. M.; González, J. F. Penicillium chrysogenum: phenol degradation abilities and kinetic model. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2012, 223, 2323–2332. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunmolu, F. E.; Kaur, I.; Gupta, M.; Bashir, Z.; Pasari, N.; Yazdani, S. S. Proteomics Insights into the Biomass Hydrolysis Potentials of a Hypercellulolytic Fungus Penicillium funiculosum. Journal of proteome research 2015, 14(10), 4342–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, H.V.; Ramalingappa; Krishnappa, M.; Thippeswamy, B. Degradation of polyethylene by Penicillium simplicissimum isolated from local dumpsite of Shivamogga district. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2015, 17(4), 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, A.; Ismail, F.; Imran, M. Biodegradation of synthetic plastics by the extracellular lipase of Aspergillus niger. Environmental Advances 2024, 17, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Yamagata, Y.; Abe, K.; Hasegawa, F.; Machida, M.; Ishioka, R.; Gomi, K.; Nakajima, T. Purification and characterization of a biodegradable plastic-degrading enzyme from Aspergillus oryzae. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2005, 67(6), 778–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dash, H. A.; Yousef, N. E.; Aboelazm, A. A.; Awan, Z. A. Optimizing Eco-Friendly Degradation of Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Plastic Using Environmental Strains of Malassezia Species and Aspergillus fumigatus. 2023, 24(20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchut-Mikolajczyk, O.; Kwapisz, E.; Wieczorek, D.; Antczak, T. Biodegradation of diesel oil hydrocarbons enhanced with Mucor circinelloides enzyme preparation. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2015, 104, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mousa, A. A.; Hassane, A. M. A.; Gomaa, A. E.-R. F.; Aljuriss, J. A.; Dahmash, N. D.; Abo-Dahab, N. F. Response-Surface Statistical Optimization of Submerged Fermentation for Pectinase and Cellulase Production by Mucor circinelloides and M. hiemalis. Fermentation 2022, 8(5), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vršanská, M.; Voběrková, S.; Jiménez Jiménez, A. M.; Strmiska, V.; Adam, V. Preparation and Optimisation of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates Using Native Isolate White Rot Fungi Trametes versicolor and Fomes fomentarius for the Decolourisation of Synthetic Dyes. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, D. S.; Sandhu, D. K. , Laccase production and wood degradation byTrametes hirsuta. Folia Microbiologica 1984, 29(4), 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, P.; Cullen, D. Extracellular oxidative systems of the lignin-degrading Basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Fungal genetics and biology : FG & B 2007, 44(2), 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, N.; Wada, N.; Yokoyama, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Habu, N.; Konno, N. Extracellular enzymes secreted in the mycelial block of Lentinula edodes during hyphal growth. 2023, 13(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, A. G.; Lisov, A. V.; Leontievsky, A. The Role of Ligninolytic Enzymes Laccase and a Versatile Peroxidase of the White-Rot Fungus Lentinus tigrinus in Biotransformation of Soil Humic Matter: Comparative In Vivo Study. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2018, 123, 2727–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, S.; Cvancarová, M.; Muzikár, M.; Svobodová, K.; D’Annibale, A.; Petruccioli, M.; Federici, F.; Kresinová, Z.; Cajthaml, T. An efficient PAH-degrading Lentinus (Panus) tigrinus strain: effect of inoculum formulation and pollutant bioavailability in solid matrices. Journal of hazardous materials 2010, 183(1-3), 669-76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, N. T.; Gurr, S. J.; Fisher, M. C.; Blehert, D. S.; Boone, C.; Casadevall, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Cuomo, C. A.; Currie, C. R.; Denning, D. W. Fungal impacts on Earth’s ecosystems. Nature 2025, 638(8049), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan, N. Fungi in extreme environments. The Mycota 2007, 4, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mancera-López, M.; Esparza-García, F.; Chávez-Gómez, B.; Rodríguez-Vázquez, R.; Saucedo-Castañeda, G.; Barrera-Cortés, J. Bioremediation of an aged hydrocarbon-contaminated soil by a combined system of biostimulation–bioaugmentation with filamentous fungi. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2008, 61(2), 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Durairaj, P.; Malla, S.; Nadarajan, S. P.; Lee, P.-G.; Jung, E.; Park, H. H.; Kim, B.-G.; Yun, H. Fungal cytochrome P450 monooxygenases of Fusarium oxysporum for the synthesis of ω-hydroxy fatty acids in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbial Cell Factories 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemoloye, M. D.; Jonathan, S. G.; Ahmad, R. Synergistic plant-microbes interactions in the rhizosphere: a potential headway for the remediation of hydrocarbon polluted soils. International journal of phytoremediation 2019, 21(2), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, R. Cytochromes P450 as versatile biocatalysts. Journal of biotechnology 2006, 124(1), 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Beilen, J. B.; Funhoff, E. G. Alkane hydroxylases involved in microbial alkane degradation. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2007, 74, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D. E.; Kraševec, N.; Mullins, J.; Nelson, D. R. The CYPome (cytochrome P450 complement) of Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal genetics and biology 2009, 46(1), S53–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktali, V.; Park, J.; Fedorova-Abrams, N. D.; Park, B.; Choi, J.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kang, S. Systematic and searchable classification of cytochrome P450 proteins encoded by fungal and oomycete genomes. BMC genomics 2012, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lee, M.-K.; Jefcoate, C.; Kim, S.-C.; Chen, F.; Yu, J.-H. Fungal cytochrome p450 monooxygenases: their distribution, structure, functions, family expansion, and evolutionary origin. Genome biology and evolution 2014, 6(7), 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauda, W. P.; Abraham, P.; Glen, E.; Adetunji, C. O.; Ghazanfar, S.; Ali, S.; Al-Zahrani, M.; Azameti, M. K.; Alao, S. E. L.; Zarafi, A. B. Robust Profiling of Cytochrome P450s (P450ome) in Notable Aspergillus spp. Life 2022, 12(3), 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doddapaneni, H.; Subramanian, V.; Fu, B.; Cullen, D. A comparative genomic analysis of the oxidative enzymes potentially involved in lignin degradation by Agaricus bisporus. Fungal genetics and biology 2013, 55, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayaka, A. H.; Tibpromma, S.; Dai, D.; Xu, R.; Suwannarach, N.; Stephenson, S. L.; Dao, C.; Karunarathna, S. C. A review of the fungi that degrade plastic. Journal of fungi 2022, 8(8), 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viel, T.; Manfra, L.; Zupo, V.; Libralato, G.; Cocca, M.; Costantini, M. Biodegradation of plastics induced by marine organisms: future perspectives for bioremediation approaches. Polymers 2023, 15(12), 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, E.; Harefa, R.; Priyani, N.; Suryanto, D. In Plastic degrading fungi Trichoderma viride and Aspergillus nomius isolated from local landfill soil in Medan, IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science, 2018; IOP Publishing: 2018; p 012145.

- Satti, S. M.; Shah, A. A.; Auras, R.; Marsh, T. L. Isolation and characterization of bacteria capable of degrading poly (lactic acid) at ambient temperature. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2017, 144, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Morsy, E.; Hassan, H.; Ahmed, E. Biodegradative activities of fungal isolates from plastic contaminated soils. Mycosphere 2017, 8(8), 1071–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczak, K.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Znajewska, Z.; Dąbrowska, G. Use of rhizosphere microorganisms in the biodegradation of PLA and PET polymers in compost soil. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2018, 130, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, N.; Pradhan, N.; Singh, S.; Barla, A.; Shrivastava, A.; Khatua, P.; Rai, V.; Bose, S. Evaluation of HDPE and LDPE degradation by fungus, implemented by statistical optimization. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 39515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artham, T.; Doble, M. Biodegradation of physicochemically treated polycarbonate by fungi. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Paço, A. M. S. Biotechnological Tools for Plastic Waste Remediation Using Marine Fungi. Universidade de Aveiro (Portugal), 2024.

- Gao, R.; Liu, R.; Sun, C. A marine fungus Alternaria alternata FB1 efficiently degrades polyethylene. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 431, 128617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, F.; Moslem, M.; Hadi, S.; Al-Sabri, A. E. Biodegradation of Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE) by Mangrove fungi from the red sea coast. Progress in Rubber Plastics and Recycling Technology 2015, 31(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhel, R.; Sengupta, S.; Das, P.; Bhowal, A. Comparative biodegradation study of polymer from plastic bottle waste using novel isolated bacteria and fungi from marine source. Journal of Polymer Research 2020, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Junaid, M.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Eco-corona formation and associated ecotoxicological impacts of nanoplastics in the environment. The Science of the total environment 2022, 836, 155703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Wang, J. Interaction of nanoplastics with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in the aquatic environment: A special reference to eco-corona formation and associated impacts. Water research 2021, 201, 117319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüffer, T.; Hofmann, T. Sorption of non-polar organic compounds by micro-sized plastic particles in aqueous solution. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 2016, 214, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Sha, W.; Wang, Y. Sorption Behavior and Mechanisms of Organic Contaminants to Nano and Microplastics. 2020, 25(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M. M.; Dos, S. M. E.; da, S. S. I.; Lima, A. L.; de Oliveira, F. R.; de Freitas, C. M.; Fernandes, C. P.; de Carvalho, J. C. T.; Ferreira, I. M. Silver nanoparticle from whole cells of the fungi Trichoderma spp. isolated from Brazilian Amazon. 2020, 42(5), 833–843. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk, A.; Gajewicz, A.; Rasulev, B.; Schaeublin, N.; Maurer-Gardner, E.; Hussain, S.; Leszczynski, J.; Puzyn, T. Zeta Potential for Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: A Predictive Model Developed by a Nano-Quantitative Structure–Property Relationship Approach. Chemistry of Materials 2015, 27(7), 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N. A. R.; Lenardon, M. D. Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall. 2023, 21(4), 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orasch, T.; Gangapurwala, G.; Vollrath, A.; González, K.; Alex, J.; De San Luis, A.; Weber, C.; Hoeppener, S.; Cseresnyés, Z.; Figge, M. T.; Guerrero-Sanchez, C.; Schubert, U. S.; Brakhage, A. A. Polymer-based particles against pathogenic fungi: A non-uptake delivery of compounds. Biomaterials advances 2023, 146, 213300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafla-Endara, P. M.; Meklesh, V.; Beech, J. P.; Ohlsson, P.; Pucetaite, M.; Hammer, E. C. Exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics reduces bacterial and fungal biomass in microfabricated soil models. The Science of the total environment 2023, 904, 166503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Ye, R.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Xie, Z.; Ou, X.; Yu, N.; Huang, C.; Hua, Y.; Zhou, R.; Tian, B. Distinct lipid membrane interaction and uptake of differentially charged nanoplastics in bacteria. 2022, 20(1), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, O.; Chrisman, C. J.; Castelli, M. V.; Frases, S.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J. L.; Casadevall, A. Capsule enlargement in Cryptococcus neoformans confers resistance to oxidative stress suggesting a mechanism for intracellular survival. Cellular microbiology 2008, 10(10), 2043–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, M.; Webb, G. The Environmental Effects on Virulence Factors and the Antifungal Susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevention, U. S. C. f. D. C. a. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shruti, V. C.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Pérez-Guevara, F. Do microbial decomposers find micro- and nanoplastics to be harmful stressors in the aquatic environment? A systematic review of in vitro toxicological research. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 903, 166561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, B. Physiological response of ectomycorrhizal fungi (Lactarius delicious) to microplastics stress. Global Nest Journal 2023, 25(3), 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Qv, W.; Niu, Y.; Qv, M.; Jin, K.; Xie, J.; Li, Z. Nanoplastic pollution inhibits stream leaf decomposition through modulating microbial metabolic activity and fungal community structure. Journal of hazardous materials 2022, 424 Pt A, 127392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Zeng, R.; Zeng, S.; Liu, S. Polystyrene nanoplastics foster Escherichia coli O157:H7 growth and antibiotic resistance with a stimulating effect on metabolism. Environmental Science: Nano 2023, 10(5), 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, R.; Wu, H.; Xu, K.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gong, W. Nanoplastics promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance through conjugative gene transfer: implications from oxidative stress and gene expression. Environmental Science: Nano 2023, 10(5), 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, A.; Różalska, S. Microplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress in Metolachlor-Degrading Filamentous Fungus Trichoderma harzianum. 2022, 23(21). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus | Representative Species | Enzymes | Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ganoderma | Ganoderma lucidum; G. applanatum | Lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase, polyesterase | Degradation of plastics and other organic materials | [30] |

| Pleurotus | Pleurotus abalones; P. ostreatus | Cellulases, lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase | Capable of degrading polylactic acid (PLA), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyester plastics such as PET | [31,32] |

| Penicillium | Penicillium chrysogenum; P. funiculosum; P. simplicissimum | Polyesterases, esterases, ligninases, cellulases, phenol oxidase | Strains of Penicillium capable of degrading plastics such as polyurethane and polyethylene | [33,34,35] |

| Aspergillus | Aspergillus niger; A. oryzae; A. fumigatus | Esterases, polyesterases, cellulases, phenol oxidase, ligninases | Capable of degrading polyester plastics, such as PET | [36,37,38] |

| Mucor | Mucor circinelloides; M. hiemalis | Polyesterases, esterases, oxidases, cellulases | Capable of degrading polyester plastics | [39,40] |

| Trametes | Trametes versicolor; T. hirsuta | Lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase, polyesterase | Effective in plastic degradation, especially for polymers like polyurethane and polyethylene | [41,42] |

| Phanerochaete | Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase, polyesterase | Degradation of lignin and certain plastics | [43] |

| Lentinus | Lentinus edodes; L. tigrinus | Lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, laccase, cellulase | Effective in degrading lignin and some synthetic materials | [44,45,46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).