1. Introduction

Oral diseases pose a significant global health burden, affecting approximately 3.5 billion people worldwide with conditions such as dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancers, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Timely and accurate diagnosis is critical for effective treatment and prevention of complications. Oral disease recognition, which focuses on detecting specific pathologies from oral cavity images, has emerged as a promising application of computer vision in healthcare. The ability to identify issues such as calculus, gingivitis, or caries from standard images could revolutionize dental screenings, particularly in resource-limited settings where specialist care is scarce [

1,

2].

The advancement of deep learning technologies has catalyzed significant progress in medical image analysis, with researchers developing increasingly sophisticated algorithms capable of analyzing oral cavity images with promising initial results [

3,

4]. These AI-driven diagnostic tools hold immense potential for improving healthcare accessibility, enabling cost-effective screening programs, and augmenting clinical decision-making in dentistry and oral medicine. The integration of such technologies could particularly benefit underserved communities where access to dental specialists remains limited.

Despite promising advances, current approaches to oral disease recognition face critical limitations. Existing deep learning methods predominantly conceptualize this task as a straightforward image classification problem [

5,

6,

7], employing convolutional neural networks [

8,

9,

10,

11,

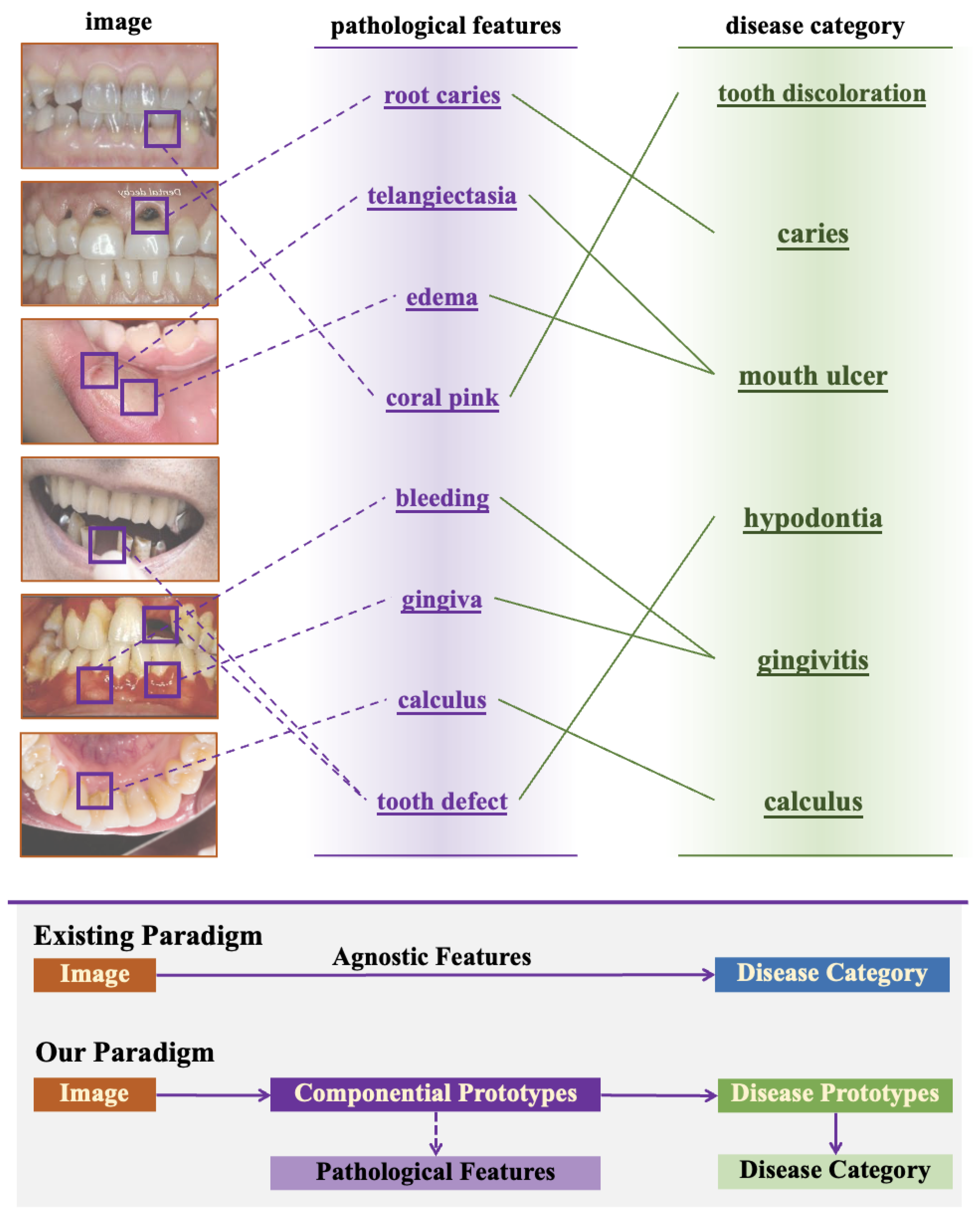

12] to directly map input images to predefined diagnostic labels. This end-to-end classification paradigm fundamentally diverges from the diagnostic process employed by clinical experts. As illustrated in

Figure 1, experienced clinicians employ a structured two-stage diagnostic workflow: first identifying specific pathological features—such as calculus deposits, inflamed gingival tissues, or enamel demineralization—then systematically correlating these observations with established diagnostic criteria through multidimensional analysis.

The failure to incorporate this pathological reasoning process into computational models creates several significant challenges. First, conventional deep learning approaches lack explicit mechanisms for modeling clinically relevant features, limiting their ability to capture the intrinsic characteristics of oral diseases. Second, without decomposing diseases into constituent pathological components, these models struggle to generalize across varied disease presentations and stages. Third, the black-box nature of standard classification networks provides minimal interpretability, offering little insight into the reasoning behind diagnostic predictions. These limitations highlight the urgent need for more sophisticated approaches that better align with clinical diagnostic paradigms.

To address these challenges, we propose Dynamic Compositional Hierarchical Prototype (DCHP) Learning, a novel deep neural architecture specifically designed to emulate clinical diagnostic reasoning for oral disease recognition. DCHP regards disease classification as a structured process of identifying, weighting, and composing pathological components, rather than a direct mapping from images to labels. This approach enables more robust recognition while providing clinically meaningful interpretations of model decisions.

Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

We proposed a novel dynamic compositional prototype network that decomposes complex oral diseases into a dictionary of reusable componential prototypes. Each prototype represents a fundamental visual pattern that may appear across multiple disease conditions. This compositional approach enables efficient knowledge sharing across diseases and reduces the reliance on large labeled datasets.

We developed a dynamic prototype assembly mechanism that selectively activates and weighs relevant prototypes based on input image characteristics, generating disease-specific signatures through sparse compositional representation. This dynamic assembly process accommodates the inherent variability in disease presentations across patients, enhancing model robustness to intra-class variations.

We introduce a gradient suppression strategy applied to lower-level convolutional layers during fine-tuning to ensure effective utilization of external knowledge from pre-training, enhance model generalization, and reduce data dependency. This approach preserves the fundamental visual processing capabilities acquired from pre-trained models while enabling higher layers to adapt specifically to oral disease features.

Through comprehensive experiments on the Dental Condition Dataset, we demonstrate that DCHP consistently outperforms state-of-the-art classification models, achieving 93.3% accuracy and 91.9% macro-F1 score across six common oral diseases. Additionally, we show that our approach maintains strong performance even with limited training data, highlighting its efficiency in real-world clinical scenarios.

2. Related Work

Our main work is to propose a novel prototype learning method for oral disease recognition. In this section, we review related works, including deep learning-based oral disease recognition and prototype learning methods for image analysis.

2.1. Oral Disease Recognition

Recent advances in deep learning have revolutionized oral disease diagnostics by addressing limitations of traditional methods. Hybrid architectures like InceptionResNetV2 [

5,

7] and optimization techniques such as Common Vector Approach (CVA)-pool weighting [

6] enhance feature extraction and classification accuracy for caries, gingivitis, and oral lesions. AI-driven biomarker discovery [

13] enables non-invasive salivary analysis, while specialized models demonstrate precision in detecting recurrent aphthous ulcers [

14] and oral cancers [

15,

16]. Systematic reviews [

17,

18] validate AI’s clinical potential, particularly in radiographic interpretation and lesion classification. Innovations in model interpretability [

16], multi-modal data integration [

19], and ensemble strategies [

20,

21] highlight the shift toward transparent, clinically actionable systems. These developments collectively establish AI as a transformative tool across diagnostic workflows, from early detection to treatment planning, while frameworks like ACES [

22] (Application of the 2018 periodontal status Classification to Epidemiological Survey data) provide standardized evaluation protocols for periodontal conditions.

Current deep learning methods often simplify diagnosis to a basic image-to-label mapping (i.e., classification), overlooking the need to model disease-specific visual patterns explicitly. This limits their generalization to new data, especially with scarce training samples. We introduce the DCHP framework, utilizing componential and category prototypes to capture localized pathological features and oral diseases, addressing these shortcomings.

2.2. Prototype Learning for Image Analysis

Prototype learning represents a classical method in pattern recognition where prototypes serve as representatives for sets of examples. These prototypes can be obtained by designing updating rules [

23] or minimizing loss functions [

24]. In semi-supervised learning tasks [

25,

26,

27,

28], prototypes represent the data manifold for each category, facilitating supervised information propagation and noisy label correction. For image classification, prototype learning approaches [

24,

29] address recognition challenges by assigning multiple prototypes to different classes, enhancing classification robustness through prototype-based decision functions and distance computations. The application of prototype learning has expanded to weakly supervised or few-shot semantic segmentation [

30,

31], few-shot object detection [

32,

33], and person re-identification [

34,

35]. The prototype mixture model (PMM) [

36] enforces prototype-based semantic representation from limited support images by correlating diverse image regions with multiple prototypes. To improve weakly supervised semantic segmentation (WSSS), various prototype-guided solutions have emerged. An unsupervised principal prototypical features discovering strategy was developed [

30] for initial object localization, though these prototypes cannot be learned end-to-end. To generate more precise segmentation pseudo masks, cross-view feature semantic consistency regularization was implemented [

37] using pixel-to-prototype contrast while promoting intra-class compactness and inter-class dispersion in the feature space.

Current prototype learning methods focus solely on establishing prototypes at the category level, which limits their representational capacity. We propose a hierarchical prototype approach, constructing prototypes at both the component level and the category level to enhance the method’s representational power.

3. Methodology

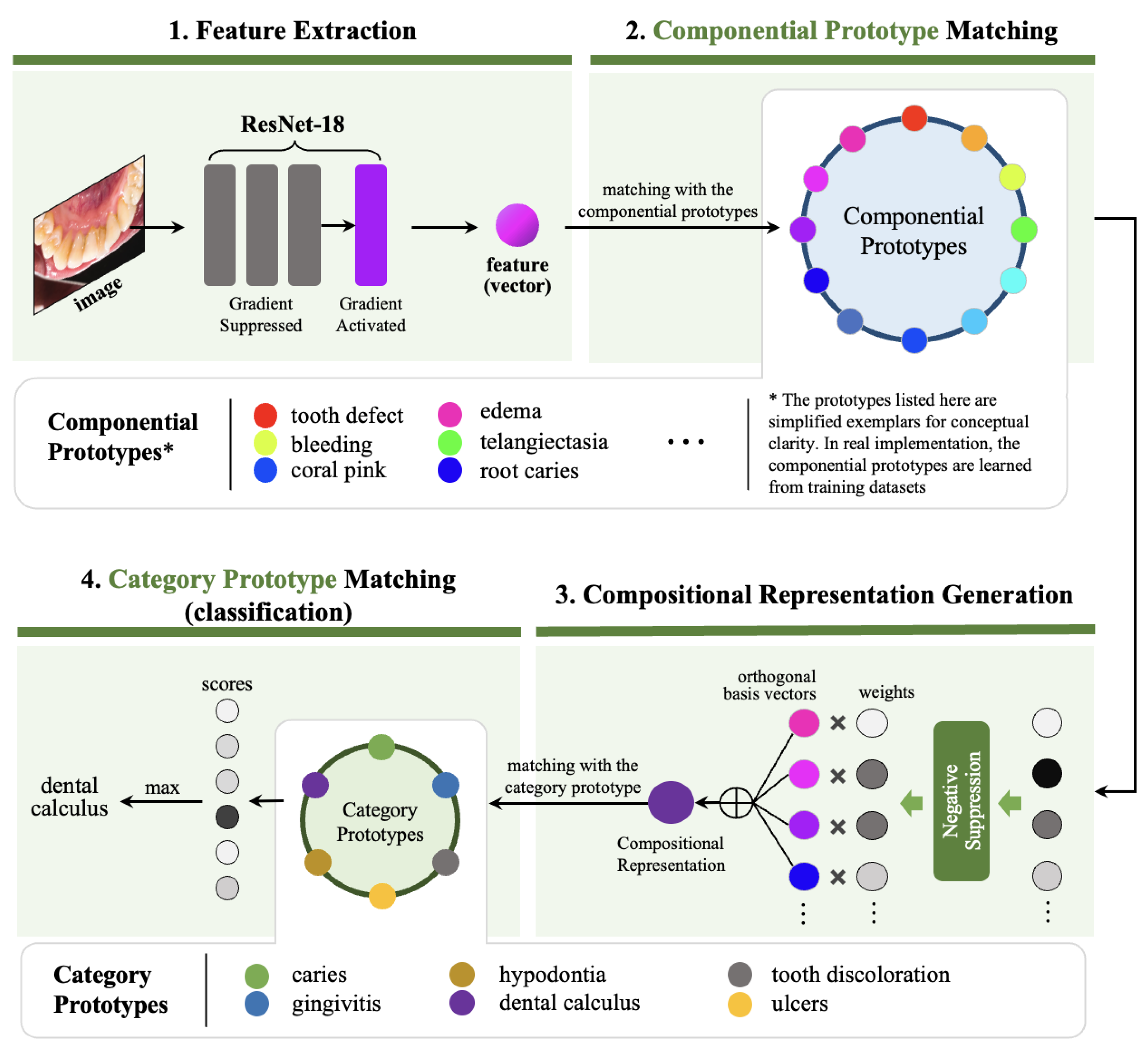

In this section, we present a comprehensive description of our proposed Dynamic Compositional Hierarchical Prototyping (DCHP) framework. As illustrated in

Figure 2, DyCoP performs oral condition recognition through a principled four-stage pipeline: 1) feature extraction, which transforms an input image into a high-dimensional feature vector

; 2) componential prototype matching, which identifies the presence of fine-grained semantic components by computing similarity scores between the extracted feature and a learned dictionary of componential prototypes; 3) compositional representation generation, which constructs a semantically-rich compositional representation by integrating the detected components with their corresponding weights; 4) category prototype matching, which performs classification by measuring similarities between the compositional representation and category-level prototypes. This architecture enables interpretable disease diagnosis by decomposing complex visual patterns into clinically meaningful components.

3.1. Feature Extraction

Given an input image from the oral cavity, we employ a parametric mapping function implemented as a modified ResNet-18 architecture to obtain discriminative feature vector , where d denotes the dimensionality of the embedding space. The feature extractor is initialized with weights pre-trained on ImageNet (ILSVRC 2012), thereby inheriting powerful visual pattern recognition capabilities developed through large-scale pretraining on natural images.

To simultaneously preserve the universal visual representations learned from large-scale pretraining while adapting to the specialized characteristics of oral pathology, we introduce a theoretically-motivated progressive gradient annealing strategy. This approach is based on the observation that early layers in convolutional neural networks typically capture domain-agnostic features (edges, textures, and basic shapes) that generalize well across visual domains, while later layers encode more task-specific semantic concepts.

For the first

L convolutional blocks containing domain-invariant edge detectors and texture filters, we employ a

selective gradient suppression strategy during backpropagation:

where

parameterizes the

l-th convolutional layer, and

denotes the task-specific loss function used in the training process. This gradient manipulation strategy effectively implements a form of transfer learning that preserves fundamental visual processing capabilities while allowing task-specific adaptation in the higher layers, striking an optimal balance between knowledge transfer and domain specialization.

3.2. Componential Prototype Matching

Central to our approach is the concept of componential prototypes, which represent atomic visual concepts that compose disease manifestations. We construct a parametric prototype dictionary

where each basis vector

represents a componential prototype encoding a distinct visual pattern relevant to oral disease classification. The component dictionary is implemented as a trainable parameter matrix

initialized using the Xavier method to ensure proper gradient flow during early training:

where

d denotes the dimensions of the feature vector, and

is the

identity matrix.

The prototype matrix undergoes optimization through stochastic gradient descent with momentum, following the update rule where represents an adaptive learning rate schedule and controls the degree of momentum retention. To ensure that each prototype captures a distinct visual concept, we impose an orthogonality constraint , which minimizes redundancy by penalizing linear dependence between prototype vectors. This can be viewed as a form of information-theoretic regularization that maximizes the semantic capacity of the prototype set within the high-dimensional feature space.

After sufficient training iterations, we establish a set of orthogonal componential prototypes that form a semantically meaningful basis for the feature space. These prototypes remain differentiable and adaptable during subsequent end-to-end training, allowing them to continuously refine their representation of disease-relevant visual patterns.

Given an oral disease image representation

, we quantify its semantic alignment with each componential prototype through a discriminative similarity metric. The matching coefficient

for the

k-th componential prototype

is computed via a non-linear transformation of the inner product:

where

denotes the non-linear negative suppression function defined as

. This rectification operation implements selective feature emphasis by preserving positive alignments while suppressing negative or conflicting evidence, thereby inducing sparsity in the prototype activation pattern. From a biological perspective, this operation mimics the selective activation patterns observed in neuronal populations responding to visual stimuli, where neurons activate only when their preferred pattern is present.

The resulting coefficients form a sparse attention distribution over prototypes, encoding the presence and strength of discriminative visual patterns characteristic of oral diseases. This decomposition provides a form of explainability, as the activation pattern reveals which visual components contribute to the diagnosis.

3.3. Dynamic Compositional Representation Generation

To dynamically integrate the detected componential patterns into a holistic disease representation, we develop a compositional encoding framework grounded in functional analysis and linear algebra. Let

denote the canonical orthonormal basis for

, uniquely characterized by the orthonormality condition:

where

represents the Kronecker delta function whose value is 1 when

and 0 otherwise, and

denotes the standard Euclidean inner product. This basis satisfies the fundamental duality relationship that enables direct component extraction:

.

Our compositional representation is generated through a weighted linear combination of these orthonormal basis vectors, where the weights are determined by the matching coefficients derived from componential prototype matching:

This formulation elegantly encodes the multi-componential nature of disease manifestations, allowing each disease to be represented as a unique combination of fundamental visual patterns. The representation dynamically adapts to the visual characteristics present in each image, highlighting the compositional nature of disease appearance.

To enable dimension adaptation between the latent composition space

and the target feature space

, we introduce a learnable projection operator with theoretical foundations in functional analysis:

where

denotes a

trainable projection matrix. This parametric transformation enables three critical capabilities: 1) dimension scaling between representation spaces, 2) learned feature recombination that captures higher-order interactions between components, and 3) differentiable composition through linear operator theory that maintains end-to-end trainability.

From a theoretical perspective, this projection can be interpreted as a form of non-linear manifold learning, where the high-dimensional disease representations are projected onto a lower-dimensional manifold that preserves the discriminative information relevant to classification. The parameters of are learned through backpropagation, allowing the model to discover the optimal embedding that maximizes classification performance.

3.4. Category Prototype Matching

The final prediction stage employs a prototype-based similarity analysis that connects our compositional representation to clinical disease categories. Let denote the learnable category prototypes in the latent space, where each corresponds to a specific disease class, and n represents the number of oral disease categories in our taxonomy.

The classification decision rule is formulated as a similarity maximization problem:

where

denotes the softmax operator that transforms raw similarity scores into probability distributions, and

represents the temperature hyperparameter that controls the sharpness of the probability distribution. Lower temperature values increase the contrast between similarities, effectively amplifying the model’s confidence in its predictions.

This prototype-based classification approach offers several advantages over traditional softmax classification: (1) it enables interpretation through prototype visualization; (2) it supports open-set recognition by defining acceptance thresholds on similarity scores; and (3) it provides a natural framework for few-shot learning by allowing new prototypes to be defined with limited examples.

Prototype Contrastive Loss: To train our model end-to-end, we employ a theoretically-grounded contrastive learning objective that encourages the compositional representation to align with the correct category prototype while maintaining separation from incorrect prototypes:

where

represents the projected compositional representation of input

derived using Eq. (

6).

This contrastive formulation can be interpreted through the lens of information theory as maximizing the mutual information between the compositional representation and the disease label. From a geometric perspective, the loss encourages the formation of well-separated clusters in representation space, where each cluster corresponds to a distinct disease category. The temperature parameter controls the effective radius of these clusters, with smaller values creating tighter, more concentrated distributions around the prototypes.

Note that the task-specific loss

referenced in Eq. (

1) is equivalent to the contrastive loss

defined here, establishing a unified optimization objective throughout our training procedure. This end-to-end optimization aligns all components of our framework—from feature extraction to prototype matching to compositional representation—toward the singular goal of accurate and interpretable disease classification.

4. Experiments

We conducted extensive experiments to validate the effectiveness of our proposed method. This section describes our experimental setup and results.

4.1. Experimental Setup

This part describes the experimental setups including dataset, implemental details, compared methods, and evaluation metrics.

4.1.1. Dataset

Our experiments utilize the

Dental Condition Dataset, a clinically curated collection of dental images annotated for diagnostic and research applications. The dataset covers six dental diseases as desceibed in

Table 1.

The entire dataset contains a total of 15,439 images, and all images are sourced from multisite hospital collaborations and public dental repositories. In our experiments, we selected 65% of the images for training, 20% for validation, and the remaining 15% for testing. During training, the dataset was augmented with rotation, horizontal flipping, scaling, and Gaussian noise injection. Some typical samples are shown in

Figure 3.

4.1.2. Implemental Details

In our implementation, we set the feature dimension

d to 512, orthonormal bases count

K to 512, temperature hyperparameter

to 1, and the layer number in Eq.(

1)

L to 12. All images were resized to

pixels for consistent network inputs. The model trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 16, balancing computational demands and convergence quality. Experiments ran on PyTorch using an NVIDIA 3090 GPU with 24 GB memory. We utilized the AdamW optimizer with decoupled weight decay regularization and implemented OneCycleLR scheduling with a maximum learning rate of 0.01, which peaks after 30% of training before gradually decreasing according to per-epoch training steps.

4.1.3. Compared Methods

We compared our DCHP model with several state-of-the-art computer vision architectures. The comparison models include: (1) classic CNN architectures (DenseNet121 [

8], MobileNet-v2 [

38], ResNet50 [

11], VGG16 [

12], VGG19 [

12]); (2) EfficientNet-family models [

39] (B0, B5); (3) EfficientViT variants [

40] (B3, L3, M3); (4) Inception-family networks (InceptionResnet-v2 [

41], Inception-v3 [

42]); and (5) Transformer-based models (CrossViT [

43], DEIT [

44], TNTTransformer [

45], Vision Transformer [

46]). This diverse set of baseline models spans different architectural paradigms from traditional CNNs to modern transformer-based approaches.

4.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of our classification model, we employ multiple metrics including Accuracy, Macro-Precision, Macro-Recall, and Macro F1-score.

Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified instances among the total instances:

While accuracy provides an overall performance measure, it may be misleading for imbalanced datasets. Therefore, we also utilize class-specific metrics averaged across all classes:

Macro-Precision calculates the average precision across all classes, where precision for each class is defined as:

Macro-Recall similarly averages the recall across all classes:

Macro F1-score combines precision and recall into a single metric that balances both considerations:

where

C represents the number of classes, and

,

, and

denote the true positives, false positives, and false negatives for class

i, respectively.

The macro-averaging method treats all classes equally regardless of their size, making it particularly suitable for evaluating performance on imbalanced datasets where minority classes are as important as majority classes.

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

In this part, we list the quantitative experimental results and analyze the data to evaluate our proposed method DCHP.

4.2.1. Performance Comparison with Other Models

As shown in

Table 2, the proposed DCHP model demonstrates superior performance compared to all other evaluated models. DCHP achieves a classification accuracy of 93.3%, outperforming the second-best model, InceptionResnet-v2 (92.5%), by a margin of 0.8%. Furthermore, DCHP attains the highest Macro-Precision of 92.5% and Macro-F1 Score of 91.9%, establishing its effectiveness in the classification of oral diseases.

Traditional CNN architectures, such as VGG16 and VGG19, exhibit substantially lower performance with accuracies of 64.5% and 50.3%, respectively. Notably, Transformer-based models, including Vision Transformer (75.6%) and CrossViT (79.5%), underperform compared to both our proposed model and other CNN-based architectures. This suggests that pure attention mechanisms may not sufficiently capture the intricate features associated with oral diseases without appropriate architectural modifications.

Among the evaluated models, EfficientNet-B0 (90.8%) and EfficientViT-B3 (91.0%) demonstrate competitive performance, indicating the potential of efficient architectures in this domain. However, the significant performance gap between these models and DCHP highlights the effectiveness of our approach in addressing the challenges inherent in oral disease classification.

Statistical analysis (

Table 3) demonstrates DCHP’s significant performance advantages. It achieves large gains over Classic CNNs (+20.0% Macro-F1, p<0.001) and Transformers (+13.9% Macro-F1, p<0.001). Compared to the previous SOTA (InceptionResNet-v2), DCHP shows statistically significant improvements in Accuracy (+0.8%, p=0.023), Macro-Precision (+1.4%, p=0.015), and Macro-F1 (+0.6%, p=0.031); a slight Macro-Recall dip (-0.7%) was not significant (p=0.104). Advantages hold for EfficientNet (+1.0-2.5%, p<0.05) and EfficientViT (+0.9-3.0%, p<0.05). Benchmarked across 17 models, these results validate DCHP’s architectural superiority.

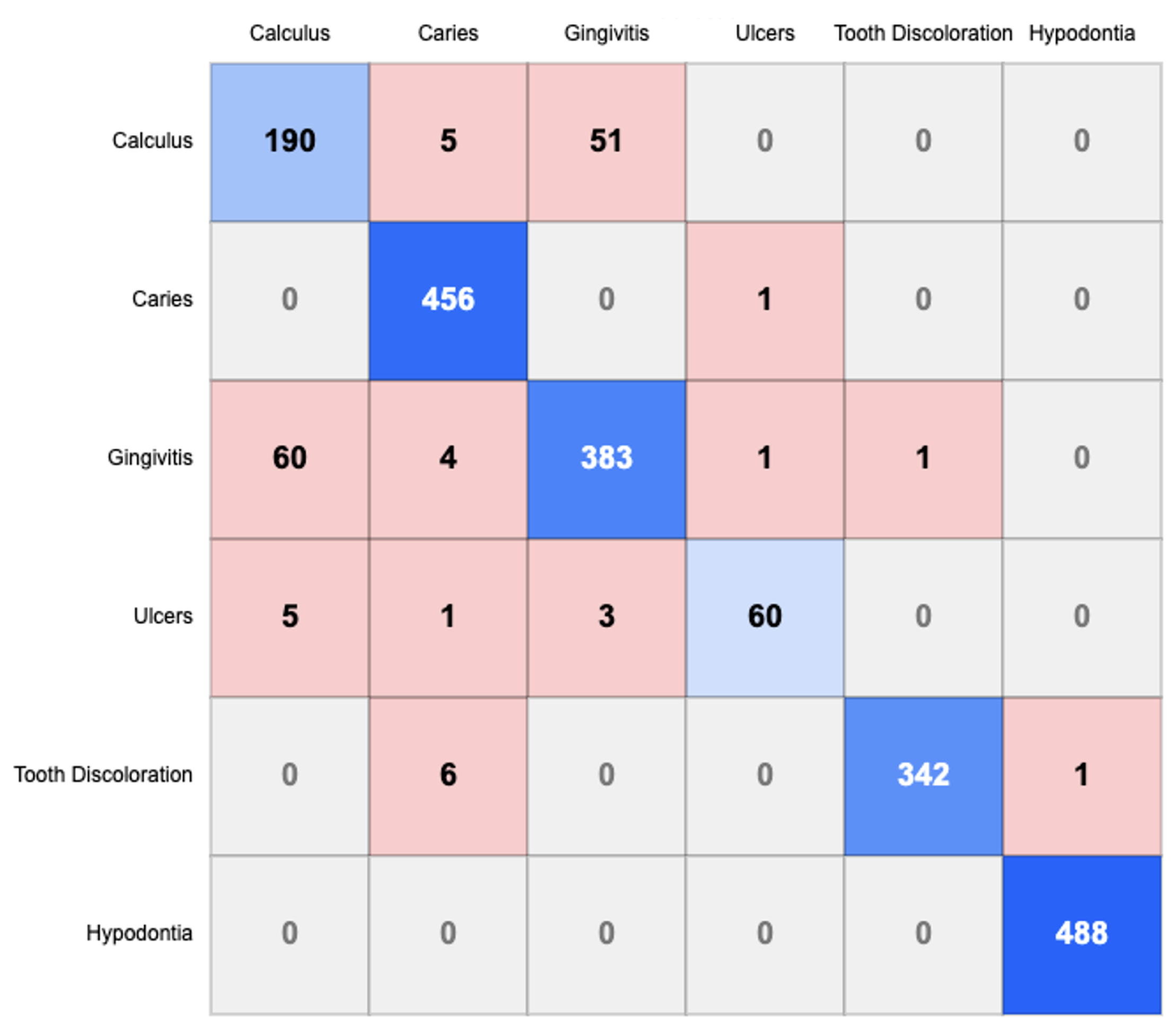

4.2.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 4 provides detailed insights into the model’s classification performance across six oral conditions: Calculus, Caries, Gingivitis, Ulcers, Tooth Discoloration, and Hypodontia.

Diagnostic Accuracy: The diagonal elements of the confusion matrix represent correctly classified instances, revealing strong performance across most categories. Hypodontia exhibits the highest number of correct classifications (488), followed by Caries (456) and Gingivitis (383). This demonstrates the model’s robust ability to identify distinctive features associated with these conditions.

Cross-Misclassification Patterns: Several notable cross-misclassification patterns emerge from the confusion matrix:

Calculus-Gingivitis Confusion: A substantial bidirectional misclassification exists between Calculus and Gingivitis, with 51 instances of Calculus misclassified as Gingivitis and 60 instances of Gingivitis misclassified as Calculus. This suggests morphological similarities between these conditions that challenge accurate differentiation.

Caries Classification: Caries demonstrates minimal confusion with other categories, indicating that its visual manifestations are sufficiently distinctive for accurate identification by the model.

Tooth Discoloration: Six instances of Tooth Discoloration are misclassified as Caries, indicating potential visual similarities in certain presentations of these conditions.

Hypodontia Recognition: Hypodontia shows negligible confusion with other conditions, achieving near-perfect classification with 488 correct identifications and no false negatives, suggesting highly distinctive visual characteristics.

Classification Robustness: The sparsity of certain regions in the confusion matrix indicates minimal confusion between specific condition pairs. For instance, Calculus and Tooth Discoloration show no mutual misclassification, as do Hypodontia and most other conditions. This demonstrates the model’s capacity to distinguish between conditions with dissimilar visual presentations.

In summary, the experimental results validate the superior performance of our proposed DCHP model across multiple evaluation metrics. The confusion matrix analysis reveals both the strengths of the model in differentiating most oral conditions and specific classification challenges, particularly between Calculus and Gingivitis. These insights provide valuable direction for future refinements, especially targeting improved discrimination between conditions that exhibit similar visual characteristics.

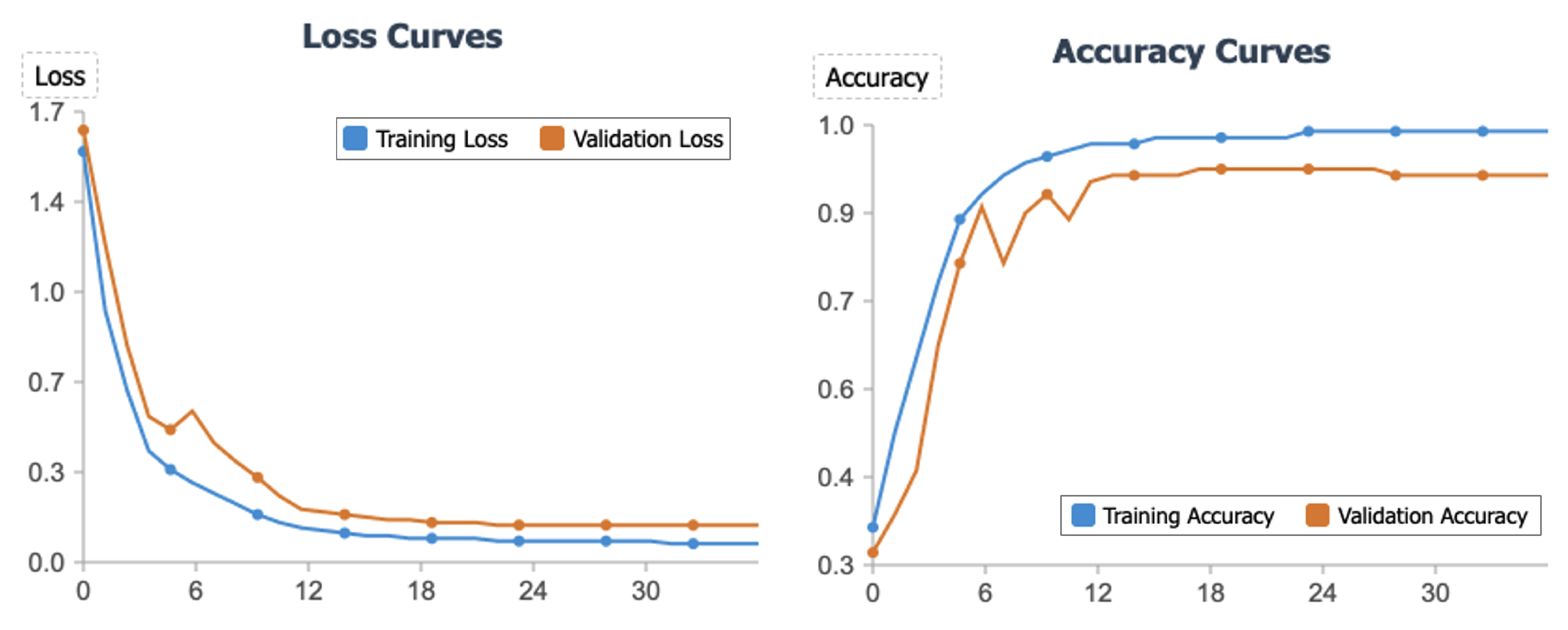

4.3. Convergence Analysis

Figure 5 presents the loss and accuracy curves for our model during training and validation. The loss curves demonstrate rapid convergence, with validation loss declining sharply from 1.63 to 0.5 within the first 4 epochs and ultimately stabilizing at 0.14. Similarly, the accuracy curves show swift improvement, with validation accuracy increasing from 32% to nearly 80% in early epochs before reaching a steady state of 92-93%. The consistent downward trend of the loss function and the corresponding increase in accuracy, both exhibiting stability in later epochs, provide compelling evidence that our proposed method converges efficiently and achieves robust performance on unseen data.

4.4. Ablation Study

To validate the contribution of each component in our proposed DCHP model, we conducted a comprehensive ablation study.

Table 4 presents the quantitative results of this analysis, demonstrating the impact of various architectural choices on model performance.

4.4.1. Overall Performance Gain from Our Multiple Designs

To evaluate the cumulative effect of our proposed designs, we performed an ablation by removing all DCHP-specific components, reverting to the baseline ResNet-18 architecture. As reported in

Table 4, the ResNet-18 baseline achieves an accuracy of 83.3%, macro-precision of 81.4%, macro-recall of 85.0%, and macro-F

1 score of 83.2%. In contrast, the full DCHP model attains a significantly higher accuracy of 93.3%, representing a performance gain of 10.0%. This substantial improvement highlights the critical role of our architectural enhancements in advancing the classification of oral diseases.

4.4.2. Effectiveness of Main Designs

We systematically ablated individual components from the DCHP model to quantify their contributions to overall performance. The results are detailed below:

Gradient Suppression: Eliminating the gradient suppression mechanism reduces accuracy by 2.2% (from 93.3% to 91.1%) and macro-F1 score by 1.8% (from 91.9% to 90.1%). This decline underscores the importance of gradient suppression in mitigating overfitting and bolstering the model’s generalization capacity.

-

Componential Prototypes: Removing componential prototypes results in a notable decrease of 3.0% in accuracy (from 93.3% to 90.3%) and 2.8% in macro-F1 score (from 91.9% to 89.1%). This indicates that componential prototypes are instrumental in capturing fine-grained features essential for distinguishing diverse oral disease manifestations. Furthermore, we investigated the impact of varying the number of componential prototypes on model performance:

- -

Increased Prototype Number: Doubling the number of componential prototypes to 1024 yields a slight performance reduction compared to the default configuration, with accuracy decreasing by 1.2% (from 93.3% to 92.1%) and macro-F1 score by 0.6% (from 91.9% to 91.3%). This suggests that an excess of prototypes may introduce redundancy, potentially capturing noise rather than meaningful patterns.

- -

Reduced Prototype Number: Halving the number of componential prototypes to 256 results in an accuracy drop of 1.7% (from 93.3% to 91.6%) and a macro-F1 score reduction of 1.4% (from 91.9% to 90.5%). This indicates that a minimum threshold of prototypes is required to adequately represent the diversity of features necessary for precise oral disease classification.

Dynamic Compositional Representation: The absence of dynamic compositional representation leads to the most pronounced performance drop, with accuracy decreasing by 3.5% (from 93.3% to 89.8%) and macro-F1 score by 3.8% (from 91.9% to 88.1%). This substantial degradation emphasizes the pivotal role of dynamic representations in generating discriminative features that effectively differentiate between oral disease categories.

The ablation study collectively substantiates the efficacy of our DCHP architecture. Each component—gradient suppression, componential prototypes, and dynamic component representations—contributes significantly to the model’s performance, with dynamic component representations exhibiting the greatest individual impact. Additionally, the analysis reveals that 512 componential prototypes strike an optimal balance between feature granularity and computational complexity, maximizing classification accuracy for oral disease diagnosis.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a novel DCHP framework for oral disease recognition, addressing critical challenges in automated dental diagnostics. Our method employs a novel architecture that disentangles disease representations into reusable componential prototypes and dynamically assembles them via sparse activation mechanisms. DCHP includes several key technical designs: (1) a gradient suppression strategy that preserves hierarchical feature representations while adapting to domain-specific patterns; (2) componential prototype matching that identifies atomic visual concepts present in oral disease images; (3) dynamic compositional representation generation that adaptively combines these prototypes; and (4) category prototype matching that enables effective classification through prototype-based similarity analysis. Extensive experiments on the Dental Condition Dataset demonstrate the superior performance of our approach, and the ablation studies confirm the significant contribution of each component.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Caballé-Cervigón, N.; Castillo-Sequera, J.L.; Gómez-Pulido, J.A.; Gómez-Pulido, J.M.; Polo-Luque, M.L. Machine learning applied to diagnosis of human diseases: A systematic review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, D.; Cui, Z.; Gao, C.; Gao, X.; Lian, C.; Shen, D. Two-stream graph convolutional network for intra-oral scanner image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2021, 41, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cortés, X.A.; Matamala, F.; Venegas, B.; Rivera, C. Machine-learning applications in oral cancer: A systematic review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hou, Y.; Yan, Z.; Huo, S. Text-Driven Medical Image Segmentation With Text-Free Inference via Knowledge Distillation. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Qaisar, B.; Faheem, M.; Akram, A.; Amin, R.; Hamid, M. Mouth and oral disease classification using InceptionResNetV2 method. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 33903–33921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Z.; Isik, S.; Anagun, Y. CVApool: using null-space of CNN weights for the tooth disease classification. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 16567–16579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Le, V.; Lee, D.; Kim, S. Diagnosing oral and maxillofacial diseases using deep learning. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Y.; Huo, S. Edge-Guided Hierarchical Network for Building Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiang, W. Skim-and-scan transformer: A new transformer-inspired architecture for video-query based video moment retrieval. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 270, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adeoye, J.; Su, Y. Artificial intelligence in salivary biomarker discovery and validation for oral diseases. Oral Diseases 2024, 30, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Jie, W.; Tang, F.; Zhang, S.; Mao, Q.; et al. Deep learning algorithms for classification and detection of recurrent aphthous ulcerations using oral clinical photographic images. Journal of Dental Sciences 2024, 19, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, E.; Sapri, A.; Aljehanı, R.; Jambı, B.; Bashir, T.; et al. Early diagnosis of oral cancer using image processing and artificial intelligence. Fusion: Practice and Applications 2024, 14, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Rai, A.; Ramesh, J.; Nithyasri, A.; Sangeetha, S.; et al. An explainable deep learning approach for oral cancer detection. Journal of Electrical Engineering and Technology 2024, 19, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhshad, R.; Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Price, J.; Shoorgashti, R.; Abbasiparashkouh, Z.; et al. Artificial intelligence for classification and detection of oral mucosa lesions on photographs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Oral Investigations 2024, 28, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, L.; Rubira-Bullen, I.; Nunes, F. A systematic review on caries detection classification and segmentation from x-ray images: methods datasets evaluation and open opportunities. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagnoli, D.; Leite, V.; Godoy, Y.; Lafetá, V.; Junior, E.; et al. Can predictive factors determine the time to treatment initiation for oral and oropharyngeal cancer? A classification and regression tree analysis. Plos One 2024, 19, e0302370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, B.; Pal, M.; Panigrahi, P.; Pradhan, A. An ensemble deep learning model with empirical wavelet transform feature for oral cancer histopathological image classification. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.; Kukreja, V. Enhancing Skin Disease Classification: A Hybrid CNN-SVM Model Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Automation and Computation (AUTOCOM), March 2024; pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Holtfreter, B.; Kuhr, K.; Tonetti, M.; Sanz, M.; et al. ACES: A new framework for the application of the 2018 periodontal status classification scheme to epidemiological survey data. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2024, 51, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Eim, I.; Kim, J. High accuracy handwritten Chinese character recognition by improved feature matching method. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR). 1997; Vol. 2, pp. 1033–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yin, F.; Liu, C. Robust classification with convolutional prototype learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018, pp. 2018; pp. 3474–3482. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, J.; Swersky, K.; Zemel, R. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2017; pp. 4077–4087. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Huo, S.; Xiang, W.; Hou, C.; Kung, S.Y. Semi-supervised salient object detection using a linear feedback control system model. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2018, 49, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, X. Deep self-learning from noisy labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019; pp. 5138–5147. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xiang, W.; Kung, S.Y. Semisupervised Learning Based on a Novel Iterative Optimization Model for Saliency Detection. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2019, 30, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.; Ma, C.; Huang, J.; Kira, Z. Manifold graph with learned prototypes for semi-supervised image classification. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, X. Mining confident supervision by prototypes discovering and annotation selection for weakly supervised semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 2022, 501, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, L.; Lai, J.; Xie, X. Self-supervised Image-specific Prototype Exploration for Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 4288–4298. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Lin, L.; Lyu, J.; Huang, Y.; Luo, W.; Tang, X. Prior: Prototype representation joint learning from medical images and reports. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023; pp. 21361–21371. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Revisiting the Sibling Head in Object Detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020; pp. 11563–11572. [Google Scholar]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, X.; Huang, K. Got-10k: A large high-diversity benchmark for generic object tracking in the wild. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2019, 43, 1562–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Jiao, J.; Ye, Q. Prototype mixture models for few-shot semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); Springer, 2020; pp. 763–778. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation by Pixel-to-Prototype Contrast. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 4320–4329. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Li, J.; Hu, M.; Gan, C.; Han, S. EfficientViT: Lightweight Multi-Scale Attention for High-Resolution Dense Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A.A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.R.; Zhu, Y.; Sukthankar, R. CrossViT: Cross-Attention Multi-Scale Vision Transformer for Image Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jégou, H. Training data-efficient image transformers and distillation through attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Xiao, A.; Wu, E.; et al. Transformer in Transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2021. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).