2. Materials and Methods

Urine samples sent from the clinics to our Medical Microbiology laboratory were cultured on 5% KKA and EMB double agar media, while other samples were cultured on 5% KKA, EMB agar, and chocolate agar media, before being incubated at 37°C. Blood samples were incubated in an automated culture system (BACT/ALERT® 3D) and bottles with positive signals were inoculated on 5% KKA, EMB, and chocolate agar media, before being incubated at 37°C.

At the end of the incubation period, the bacteria grown on EMB agar with blood and/or chocolate agar were considered to be Gram negative. They were passaged onto TSI and SIM agar for further identification. At the same time, they were inoculated on Mueller–Hinton agar at a density of 0.5 McFarland; susceptibility studies were performed with antibiotic disks effective against Gram-negative bacteria. These disks are routinely applied in our laboratory in accordance with EUCAST recommendations. After incubation in citrate, urea, TSI, and SIM agar at 37°C for 18-24 hours, catalase and oxidase tests were performed on citrate-positive, non-hydrolyzing, non-fermenting, and immobile bacteria. Those with positive catalase test results and negative oxidase test results were subjected to Gram staining. Those with Gram-negative coccobacilli or diplococci morphology on Gram staining were identified on the species level using the Acinetobacter spp. preliminary identification (VITEK® 2 Compact BioMérieux, France) automated identification system. The antibiotic susceptibilities of A. baumannii were determined and the strains were tested for colistin susceptibility.

2.1. Determination of the Colistin Resistance of Isolates

The Mıcronaut™ Mıc-Strip™ (Merlin Diagnostika Gmbh®, Bornheim, Germany) system is a commercial liquid microdilution method. Lyophilized, pre-prepared antibiotics are incubated and evaluated via the rehydration of Kamhb. The Mıcronaut MIC-Strip™ is run on a single 12-well strip. On this strip, the first well is the positive control, while the subsequent wells are composed of increasing doses of colistin (0.0625-64 μg/mL).

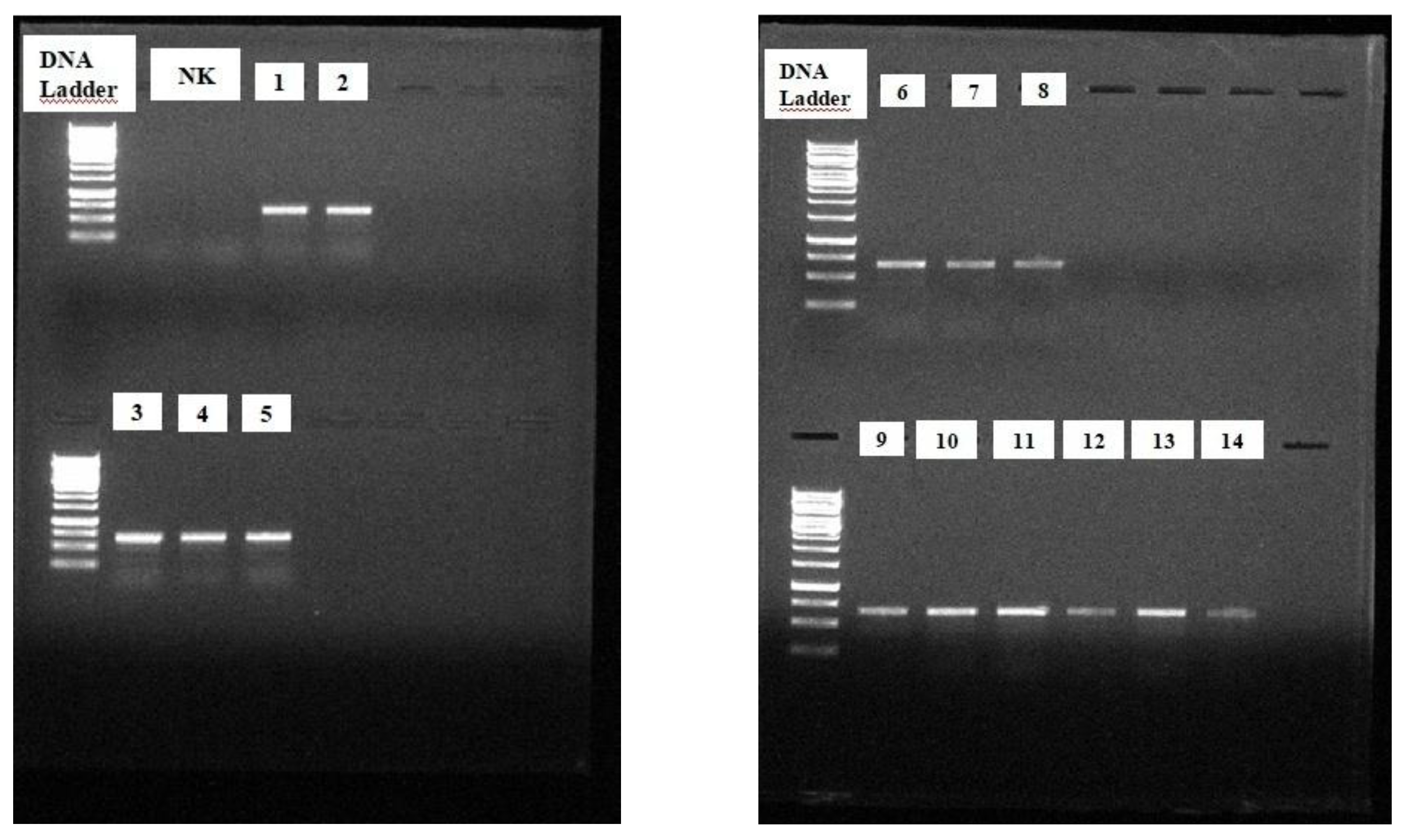

To investigate the molecular mechanism of resistance, 29 colistin-resistant and 1 colistin-susceptible A. baumannii strains (ATCC 19606) were included in the study. At this stage, we examined the expression of the chromosomal PmrA gene, which has been reported in the literature to be responsible for colistin resistance.

DNA isolation

A. baumannii strains stored at -80°C were resuspended for DNA isolation. One colony obtained using the single-colony dropping technique was inoculated into 1 ml of Luria–Bertani broth (LB) in a microcentrifuge tube under aseptic conditions, before being incubated at 37 ± 2 ºC for 18 ± 2 hours. After incubation, the following steps were adhered to, respectively, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

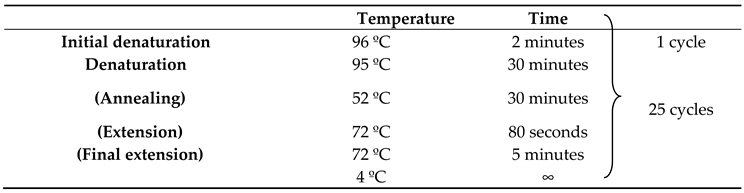

The reaction was carried out in a Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystem, USA). The cycles are shown in

Table 2.

The PCR products of 29 strains with a PmrA (+) PCR result were sent to a company for sequencing (Atlas Biotechnology LTD, Ankara) within the scope of the scientific research project TTU-2020-1102, as coordinated by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University.

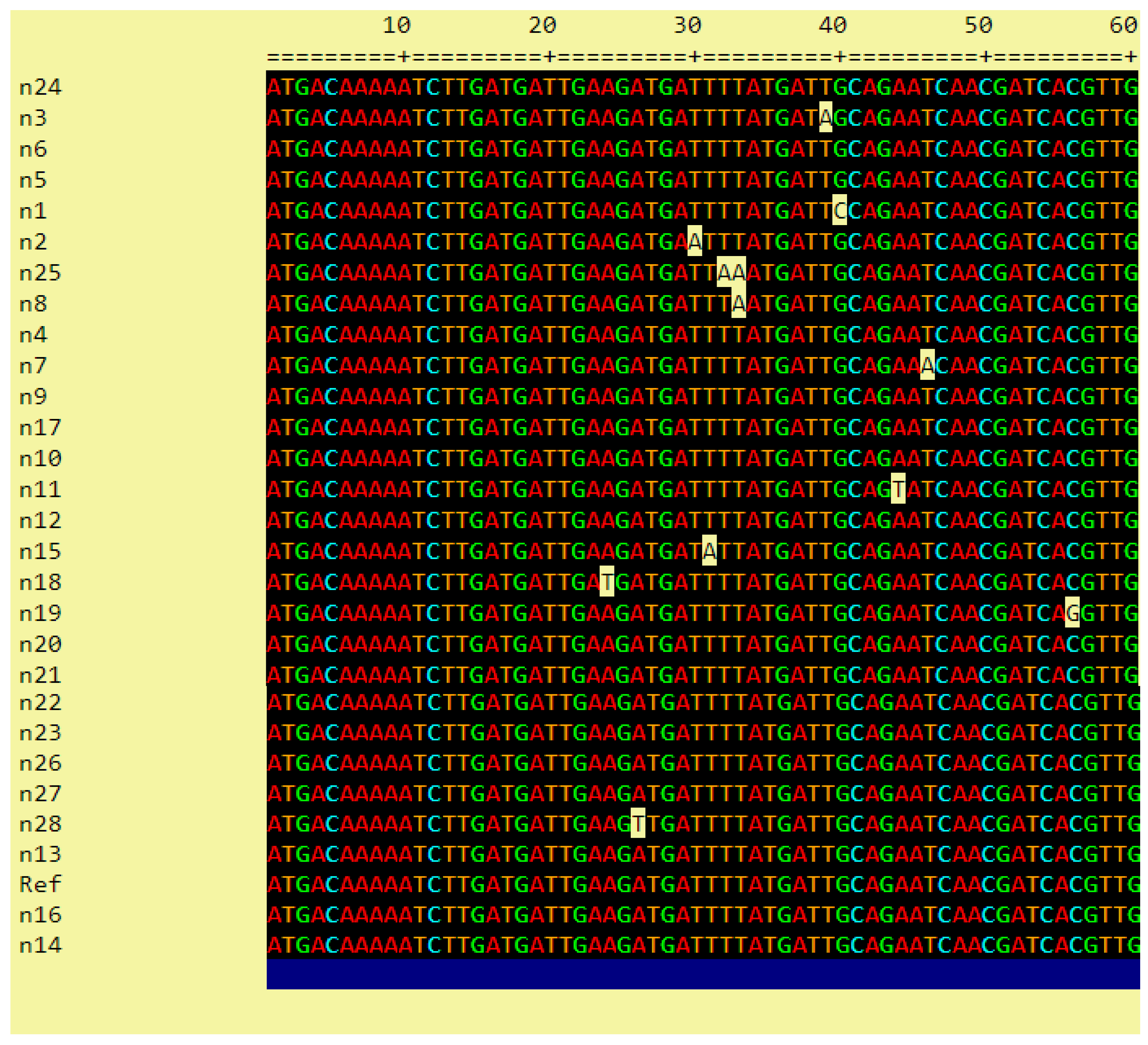

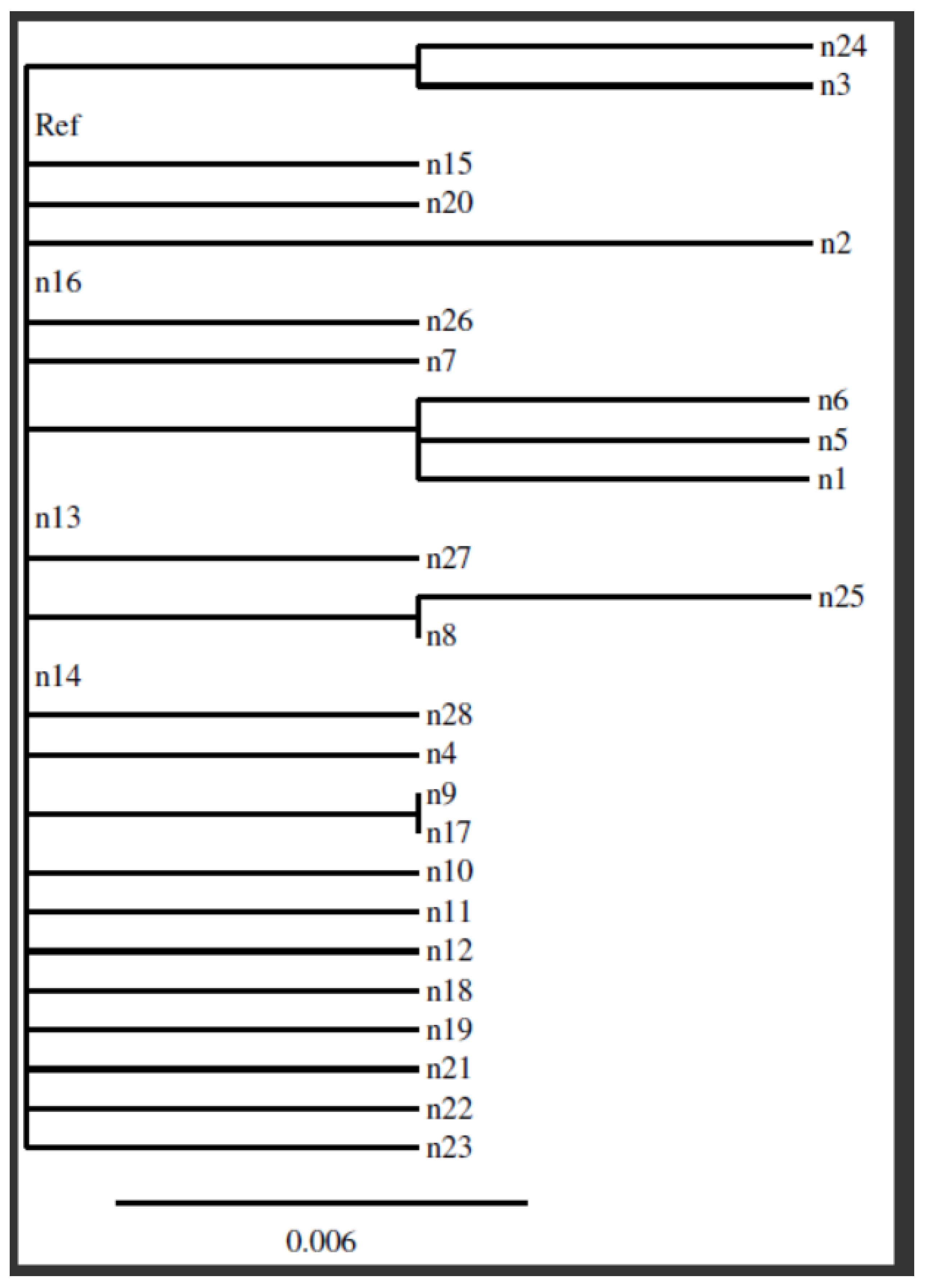

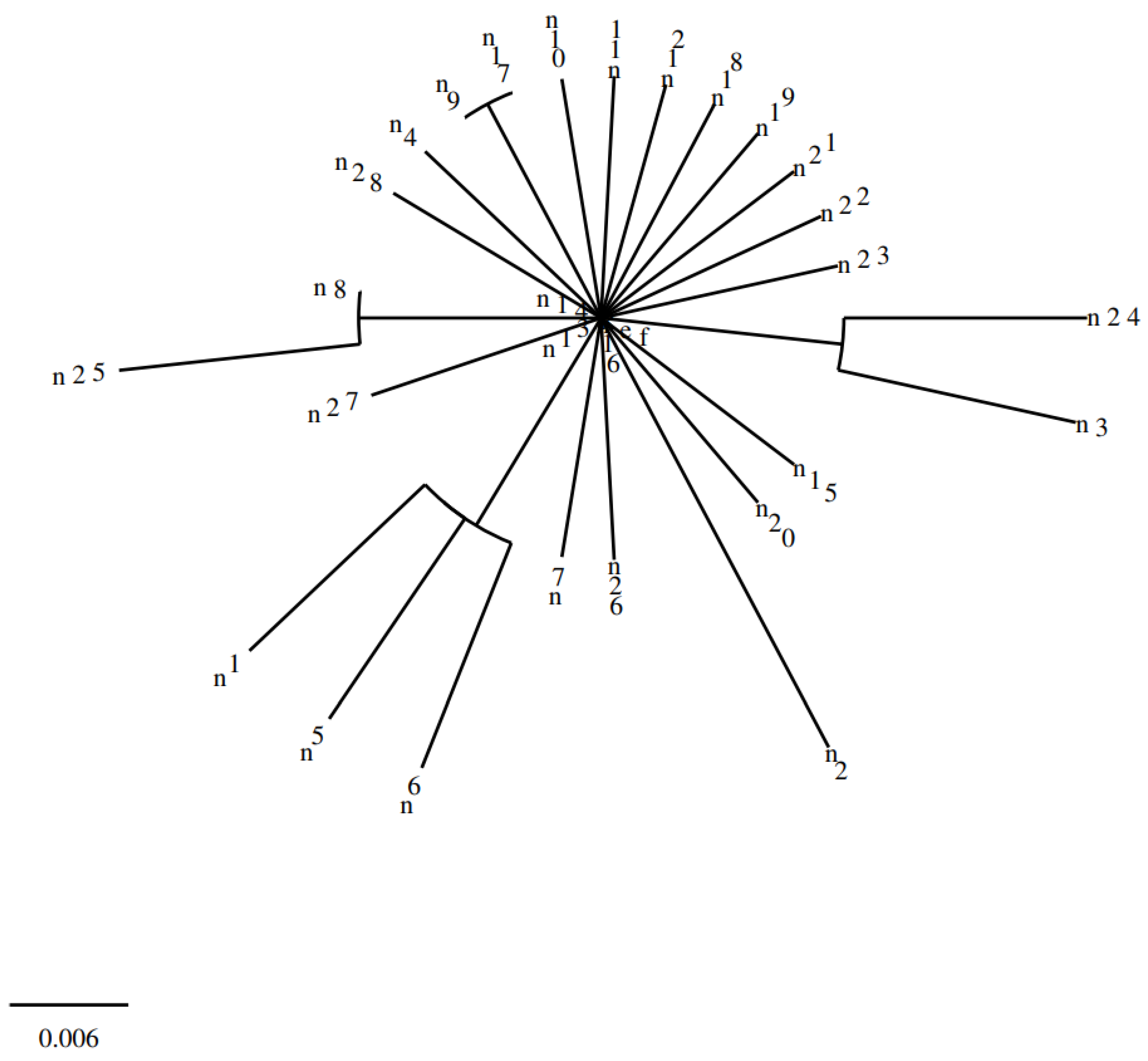

The phylogenetic analysis of the sequencing results was performed in Clustal 2.1 Multiple Sequence Alignment using the reference strain A. baumannii (GenBank: CP009257.1).

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (40465587-050.01.04-31 number 2020/20).

All analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, USA). Numerical variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (min–max), and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare independent variables. A value of p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all data.

4. Discussion

A. baumannii has emerged as being the causative agent of various infections worldwide [

1]. In recent years, this species has been widely identified as the major cause of nosocomial outbreaks associated with high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide. Although

A. baumannii, which is a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen, possesses only a limited number of “traditional” virulence factors, the mechanisms underlying its pathogenicity remain of great interest due to its increasing prevalence [

4].

A. baumannii is naturally resistant to many antimicrobials but has developed resistance to a variety of antibiotics used in its treatment (such as β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides) due to its capacity to readily acquire new antimicrobial resistance determinants [

5]. Polymyxin group antibiotics, especially colistin (with various combinations), are currently used in the treatment of MDR

A. baumannii. The accurate identification of susceptibility to polymyxin group antibiotics, as well as their mechanisms of resistance, is crucial for the use of these drugs [

6]. It is thought that without serious intervention, hospital-acquired

A. baumannii infections may soon become untreatable [

5]

.

The colistin resistance mechanism of

A. baumannii has not yet been fully elucidated. As in the colistin resistance mechanism of other Gram-negative bacteria, LPS modification, as a result of a mutation in the PmrAB two-component regulatory system, has an important place in the literature [

7]

.

In this study, we aimed to understand from which species and units the colistin resistant A. baumannii strains isolated from the samples sent to our laboratory were isolated the most, as well as which strains had PmrA gene polymorphism/mutation and a phylogenetic relationship between PmrA genes. The purpose of examining the PmrA gene in this study is that colistin resistance in A. baumannii is frequently caused by mutations in the two-component PmrAB gene.

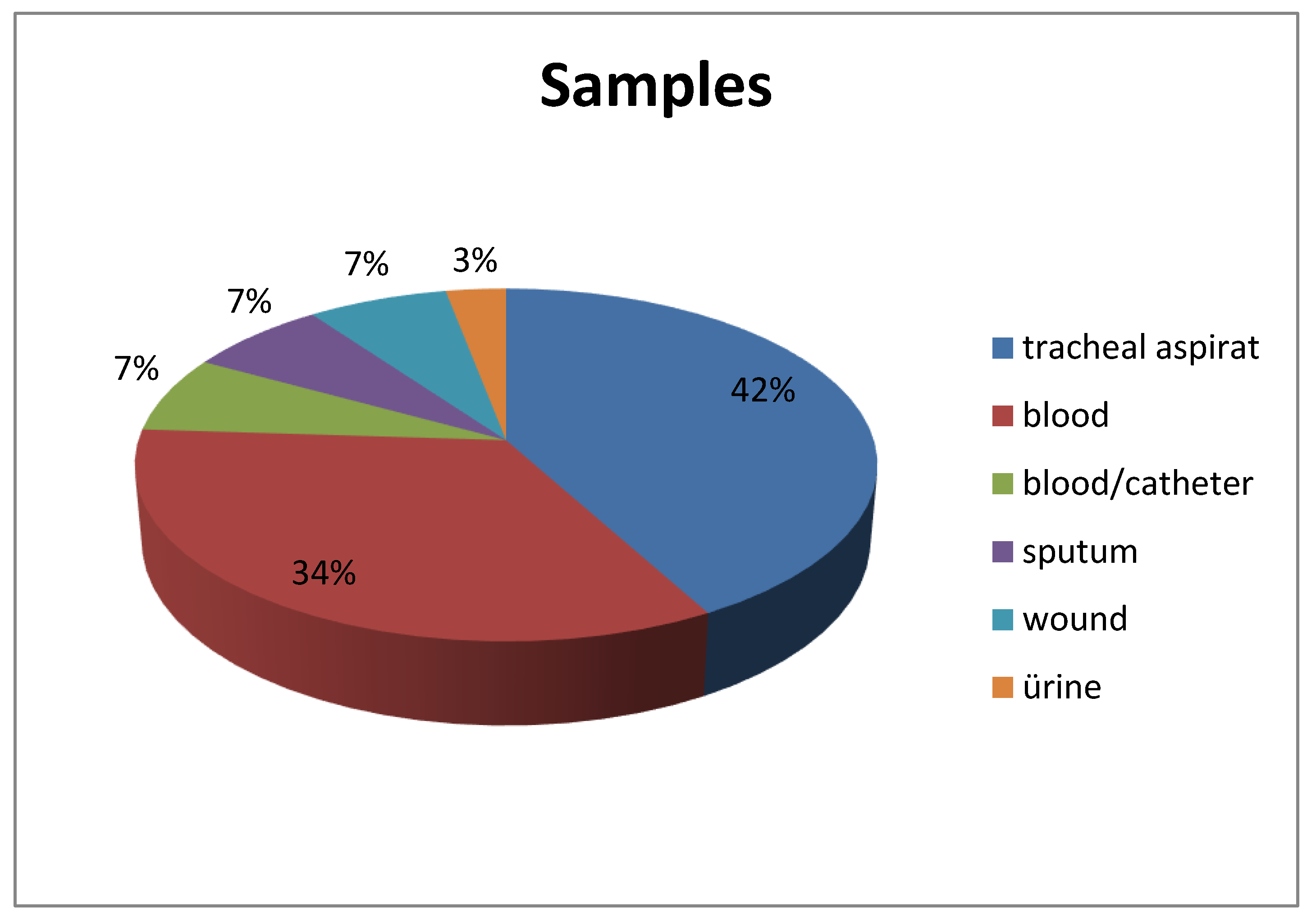

In a study investigating healthcare-associated infections in our country, it was reported that A. baumanii was the most common infectious agent in the ICU, causing respiratory tract infections. It was most frequently detected in tracheal aspirate samples [

8]. In many studies conducted in our country, it has been reported that

A. baumannii strains were mostly isolated from patients hospitalized in intensive care units [

9]. In many studies conducted globally,

A. baumannii has been the most common opportunistic pathogen in ICUs, causing respiratory tract infections and being the most frequently produced from samples such as tracheal aspirate due to its long residence time on surfaces [

10]. Similarly, in our study, tracheal aspirate (42%) was the most common sample type in which

A. baumannii was detected. It was isolated most frequently in the ICU, especially in the internal medicine ICU (89.6%). These data emphasize the necessity of infection control measures, especially in the ICU, for this agent, which is strongly associated with healthcare-associated infections.

Colistin was first discovered in 1947; however, its use was limited in the 1980s due to the renal toxicity manifested by acute tubular necrosis and neurotoxic side effects such as vertigo, visual disturbances, confusion, ataxia, and neuromuscular blockade [

11]. In recent years, it has been observed that colistin has a high therapeutic success against serious infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria [

12]. The mechanism of resistance of MDR

A. baumannii to colistin should be clarified to prevent the spread of this microorganism. Although different hypotheses have been put forward regarding the mechanism of action of colistin, the most widely accepted mechanism is that it binds to LPS and disrupts the phospholipid bilayer, causing osmotic imbalance, which leads to bacterial death [

13].

The complete loss of the lipopolysaccharide layer or mutations in LPS can lead to colistin resistance by blocking the effect of colistin on the cell membrane [

14]

. Mutations in the lpxA, lpxC, and lpxD genes associated with lipid A synthesis result in the complete loss of LPS, causing colistin resistance [

15]. Another resistance mechanism is the decrease in the negative charge of LPS due to the addition of phosphoethanolamine to lipid A as a result of increased PmrCAB expression due to mutations in the PmrAB regulatory system [

16]. In the literature, there are cases in which colistin treatment led to PmrAB mutation and paved the way for resistance [

17]. Another colistin resistance mechanism that leads to lipopolysaccharide modification occurs with the addition of galactosamine to lipid A by increasing naxD expression as a result of PmrB mutation [

18]. In addition to the colistin resistance mechanisms caused by chromosomal mutations, colistin resistance caused by plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene transfer has been detected in some Gram-negative bacteria; however, this has not yet been detected in

A. baumannii [

19].

In a study based on whole-genome sequencing, 21 colistin-resistant

A. baumannii strains were examined; PmrAB mutation was detected in 71.4% of them [

20]. In a study conducted with 29 patients in Türkiye, the PmrCAB region was examined, and a total of 14 non-synonymous mutations were detected, i.e., one in PmrA, nine in PmrB, and four in PmrC [

21]. Oikonomou et al. [

22] associated PmrA and PmrC mutations with colistin resistance; they observed that these mutations did not increase resistance to other antimicrobials. In an American study, PmrA and PmrB gene mutations were found in all 14 colistin-resistant strains isolated from patients, and colistin resistance was associated with PmrAB mutations [

17]. In our study, PmrA mutation was found in colistin-resistant strains in parallel with these studies. Although PmrAB mutations have been reported to cause heterodistance in addition to colistin resistance, the number of studies in the literature is quite small since heterodistance cannot be determined using routine tests [

16].

Not all mutations occurring in PmrAB cause colistin resistance. Lean et al. [

23] found 3 point mutations in the PmrA gene, 11 in the PmrB gene, and 8 in the PmrC gene; however, there was no significant difference between colistin-sensitive and -resistant isolates. Similarly, in a study conducted in China in which different clinical isolates were examined, several mutations were found in this gene region, but these mutations were not associated with colistin resistance [

24]. This difference may be due to the fact that different gene regions of PmrAB were examined in the studies.

In a study conducted in the UK, no mutations were found in the PmrA and PmrC gene regions in colistin-resistant isolates, while mutations were found in the PmrB gene region. In addition to the absence of PmrA mutations, PmrA expression was found to be increased up to 4-13-fold in colistin-resistant isolates [

25]. This reveals the importance of a holistic view not only of PmrA but also of the PmrCAB complex.

In another study conducted in the USA, a model for the N-terminal domain and full-length PmrA structure was created using X-ray crystallography to solve the structure of PmrA in MDR A. baumannii. Through biochemical and computational approaches, detailed information on two biologically relevant PmrA mutants and their potential structural disruptions was obtained [

26], providing information on the complexity and diversity of colistin resistance in

A. baumannii and highlighting the need for further studies.

Sequence analysis of the PmrA gene region and determination of the resulting changes is one of the first studies conducted in our country related to this field. When our study was evaluated in terms of phylogenetic relationship, the mutations in the samples were found to be closely related to each other. In contrast to some studies that failed to associate PmrA mutation with colistin resistance, we found that mutations in the 175 bp region of the PmrA gene were associated with colistin resistance, potentially paving the way for future studies in this field.

This study shows the necessity of conducting more detailed studies with larger budgets and larger sample pools for a microorganism such as A. baumannii, which is undoubtedly one of the most dangerous opportunistic pathogens globally; it continues to be on our agenda due to its resistance to the last-resort drug colistin. Our study is of great importance as a reference for both the epidemiologic and phylogenetic diversity of colistin resistance in colistin-resistant A. baumannii strains to be isolated from our region.

Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii isolates are an important problem in intensive care units; the morbidity and mortality of infections caused by these isolates are high. Increasing resistance to colistin decreases the treatment options for infections caused by these isolates. In any case, the increase in resistance to colistin has reached alarming proportions. The irregular, incorrect, and unconscious use of colistin, which is preferred to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant A. baumannii, has drastically increased the resistance to this molecule. As such, specific colistin use guidelines should be established for each patient.

Resistance to colistin and antibiotics is an indication of the need for new antibiotic regimens. New molecules should be developed and resources should be allocated to prevent antibiotic resistance, which is a common problem of humanity and is on the agenda of the United Nations.

In addition, it is clear that it is very important to monitor the resistance rates of these isolates, especially in the ICU, and to take the necessary infection control measures to prevent the colonization of resistant isolates in hospitals.

Next-generation genomic technologies are a very good option to determine the exact mechanism of colistin resistance in multidrug-resistant A. baumannii isolates. However, since these technologies are costly, reference centers should be established and identified resistant strains should be subjected to further research.

In order to prevent resistance globally, serious policies should be developed, preventive services should be increased, and traditional and natural methods should be used more frequently to increase treatment options.