1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, communities and ecosystems have been in front of a serious threat of flooding. Although flooding is a natural phenomenon that occurred always, its frequency and intensity are increasing. Of course, climate change and human activities affect the phenomena. In the past, efforts were focused on flood control through reactive disaster responses. However, nowadays, it is clear that we all have to live with floods and learn not only how to deal with them but also how to proactively build our resilience [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

7]. For instance, traditionally, dams and levees were used as flood management strategies in the context of the authorities’ control measures. Yet, such static approaches do not only have limitations but they do not contribute to what we should expect. In other words, we need the shift to flood resilience because communities and ecosystems should coexist with floods and as a result, we need proactive, adaptive strategies. Unfortunately, this is not so simple. Flood events, and of course, their impacts are driven by complex interactions that require dynamic environmental risk assessments.

Currently, researchers work on a variety of approaches [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], aiming to flood resilience. These approaches include mainly hydrological modeling and community-based adaptation. However, these approaches are primarily based on traditional modeling techniques that often cannot deal with the flood systems' nonlinear dynamics and emergency tendencies. In this context, some voices emphasize the need for either engineering solutions or nature-based approaches. In this diverse and quite confusing community, this article attempts to address the challenges by presenting BRIDGES (Building Resilience Integrating Dynamical and Agent Systems), a novel computational framework that integrates rule-based agent modeling with mathematical dynamical analysis.

Agent-based modeling was chosen as the core technology since it is suitable for modeling individual entities as well as their interactions. Hence, it is a technology that can deal with flood events and their emergency dynamics. On the other hand, mathematical dynamical analysis was adopted for the underlying mechanisms of the flood behavior and environmental responses. Hence, BRIDGES, the proposed approach, combines Artificial Intelligence (AI) with the well-established mathematical analysis forming a dynamic and autonomous approach that deals with resilience mechanisms.

The primary aim of this research is to design and develop the BRIDGES computational framework as a risk assessment tool oriented to flood resilience. More specifically, the approach aims to simulate water propagation and flood dynamics using a rule-based agent system, analyze key environmental factors that influence flood resilience, understand and quantify as much as possible flood events and environmental responses through mathematical dynamical analysis and, of course, discuss the added-value of BRIDGES as a promising flood risk assessment and environmental management approach for civil protection authorities and researchers. In this context, the article presents the first findings of the aforementioned research, revealing that the integration of rule-based agent systems with mathematical dynamical analysis can be a powerful tool for flood resilience.

2. Methodology: The BRIDGES Computational Framework

This section presents the methodology of the BRIDGES computational framework. It integrates environmental data, agent-based modeling, rule-based systems, and mathematical dynamical analysis. In this section spatial representation, agent design, rule implementation and the coupling of agent interactions with continuous-time dynamics are discussed.

2.1. Environmental Data and Representation

First of all, it is important to discuss the data and their representation. The BRIDGES approach requires environment spatially data to simulate flood dynamics. To this end, the approach uses both geospatial datasets that are publicly available and site-specific data. In this context, Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) [

13,

14], providing detailed topographic information, were obtained from Copernicus DEM [

15] at a resolution of 30 meters. Additionally, land cover data were obtained from CORINE [

16], including vegetation types and urban areas. Of course, DEMs and Land Cover data can be obtained from other sources, like MODIS [

17,

18], too. As far as it concerns hydrological data, they should be site-specific. Hence, later for the purposes of the design and development of BRIDGES we obtained data from a specific area, including daily rainfall data.

For purposes of better understanding, an example of an area is presented below. Supposing that there is a Torrent Valley watershed, the BRIDGES model application will start with the data. Hence, we should have available a variety of them:

The DEM's extent was clipped using QGIS to the watershed boundary, resulting in a raster with 1667 rows and 1667 columns. Elevation values ranged from 212 meters (lowest point near the river outlet) to 1189 meters (highest peak in the north), stored as 32-bit floating-point numbers.

The CLC data was reclassified, namely Code 321 (Natural Grasslands) was reclassified as "Sparse Vegetation" (value 1); Code 333 (sparsely vegetated areas) was reclassified as "Rocky areas" (value 2); Code 211 (Arable land) was reclassified as "Agricultural Land" (value 3); and Code 311 (Forests) was reclassified as "Forest" (value 4). The resulting raster contained integer values 1-4.

An example of this dataset is the following: On November 12, 2022, the CSV recorded "2022-11-12, 120".

An example of this dataset is the following: "2022-11-12 14:00, 150.3" (cubic meters per second).

A Shapefile ("TorrentValley_Roads.shp") containing polyline features representing roads and a Shapefile ("TorrentValley_Buildings.shp") containing polygon features representing building footprints.

Finally, specifications from the local water authority, including a dam height of 15 meters and a controlled release rate of 10 cubic meters per second.

Of course, datasets should be preprocessed and integrated into a, preferably grid/network-based, spatial framework in the sense that each grid/node will be a specific environmental unit. For the aforementioned example the preprocessing phase is the following:

A raster with values ranging from 0 to 45 degrees was generated by the QGIS "Slope" tool.

A raster with values representing the number of upstream cells was generated by the QGIS "Flow accumulation" tool.

The CLC raster was reclassified using the "Reclassify by table" tool in QGIS, assigning Manning's n values, namely Sparse Vegetation(0.08), Rocky Areas(0.10), Agricultural Land(0.05), Forest(0.15) and infiltration capacity values, namely Sparse vegetation(2 mm/hr), Rocky areas(0.5 mm/hr), Agricultural land(1 mm/hr), Forest(5 mm/hr).

The "TorVal.csv" data was processed in Python to create an hourly rainfall intensity time series, assuming a uniform distribution of rainfall within each day.

The "TorrentValley_Streamflow.csv" was used directly for comparison to simulated streamflow.

The "TorrentValley_Roads.shp" was rasterized using the "Rasterize (vector to raster)" tool in QGIS, assigning a value of 0.04 (Manning's n) to road cells.

The "TorrentValley_Buildings.shp" was rasterized, assigning a value of 0.2 (Manning's n) to building cells.

Finally, the dam was added to the DEM by raising the elevation of cells corresponding to the dam location by 15 meters.

Next, the QGIS "Create Raster Grid" tool was used to generate a grid-based framework with a cell size of 30 meters while with the QGIS "Resample" tool all rasters were resampled to the 30-meter grid. For this purpose, the nearest neighbor method was used for the categorical data (land cover) and bilinear interpolation as used for continuous data (DEM). Finally, each cell was assigned attributes, namely "Elevation," "LandCover," "ManningN," "Infiltration," "Rainfall," "Road," and "Building".

2.2. Agent-Based Modeling and Rule-Based Intelligence

This subsection presents the agent-based architecture of the BRIDGES model. This agent-based approach is the core component of the flood dynamics simulation. In this context, agents, like the WaterParticle, VegetationAgent, and the InfrastructureAgent, are used to represented key environmental elements. This way, the methodology can represent complex interactions that exist between flood propagation and resilience. The following sections discuss the attributes, behaviors, and interactions of these agents, providing a comprehensive overview of the agent-based framework. Yet, first, a brief discussion of AI intelligent agents is provided for better understanding.

2.2.1. Intelligent Agents and Adaptive Rule-Based Systems

As already discussed, the proposed methodology uses intelligent agents to represent the flood system components. At this point, it is important to understand what intelligent agents are and how they differ from traditional computational entities. Although, generally speaking, an intelligent agent is a computational entity, it can do more. More specifically, an agent can perceive its environment. It actually can gather information about it pretty much like a sensor. In BRIDGES, this involves sensing its position, the terrain slope, or the presence of other agents. An agent can also make decisions on its private strategy, namely its rule set, and the information it perceives from the environment. In the proposed model, these rules are, of course, based on established hydrological principles. An agent can even make decisions about how to act. In other words, it can act upon its decisions, changing its state or interacting with other agents and the environment. In BRIDGES this means, for instance, moving to a new location or altering water flow. Although, agents may differ in architecture and capabilities, for the proposed approach we adopt the use of rule-based agents. Hence, in this approach, intelligent agents can make decisions and adapt their behavior within the constraints of their rule-based framework. This form of intelligence allows agents to learn from their interactions with the environment and other agents. Then, they can re-decide upon their actions to better simulate real-world hydrological processes.

There are several advantages from this adaptive rule-based intelligence. First of all, agents can adapt their behavior based on environmental feedback and previously learned patterns. They can interact both with other agents, forming a multi-agent system, and the environment, simulating real-world with better accuracy than traditional approaches. Hence, this multi-agent approach can handle emergent patterns and behaviors that are difficult to model using traditional methods. These rules are carefully designed to mimic the behavior of real-world hydrological processes. Agents, this way, can respond intelligently to changing environmental conditions. Moreover, agents can represent the heterogeneity of the environment, integrating data from various sources.

In this context, the proposed methodology adopts agents to represent the entities within the flood simulation. In terms of computational modeling, an agent is a software entity that can perceive its environment, make decisions, and take actions to achieve specific goals. This AI technology was chosen because it is often used to simulate intelligent behavior in complex systems. The use of agents in the methodology offers several advantages such as modularity, agents are self-contained entities, flexibility, agents can be easily modified or extended, emergence, agents can lead to emergent patterns and dynamics, and representation of heterogeneity since they have the attributes that make them ideal for heterogeneous environments [

19,

20,

21].

Table 1 presents some of the abilities that intelligent agents have.

2.2.2. Agent-Based Module Design

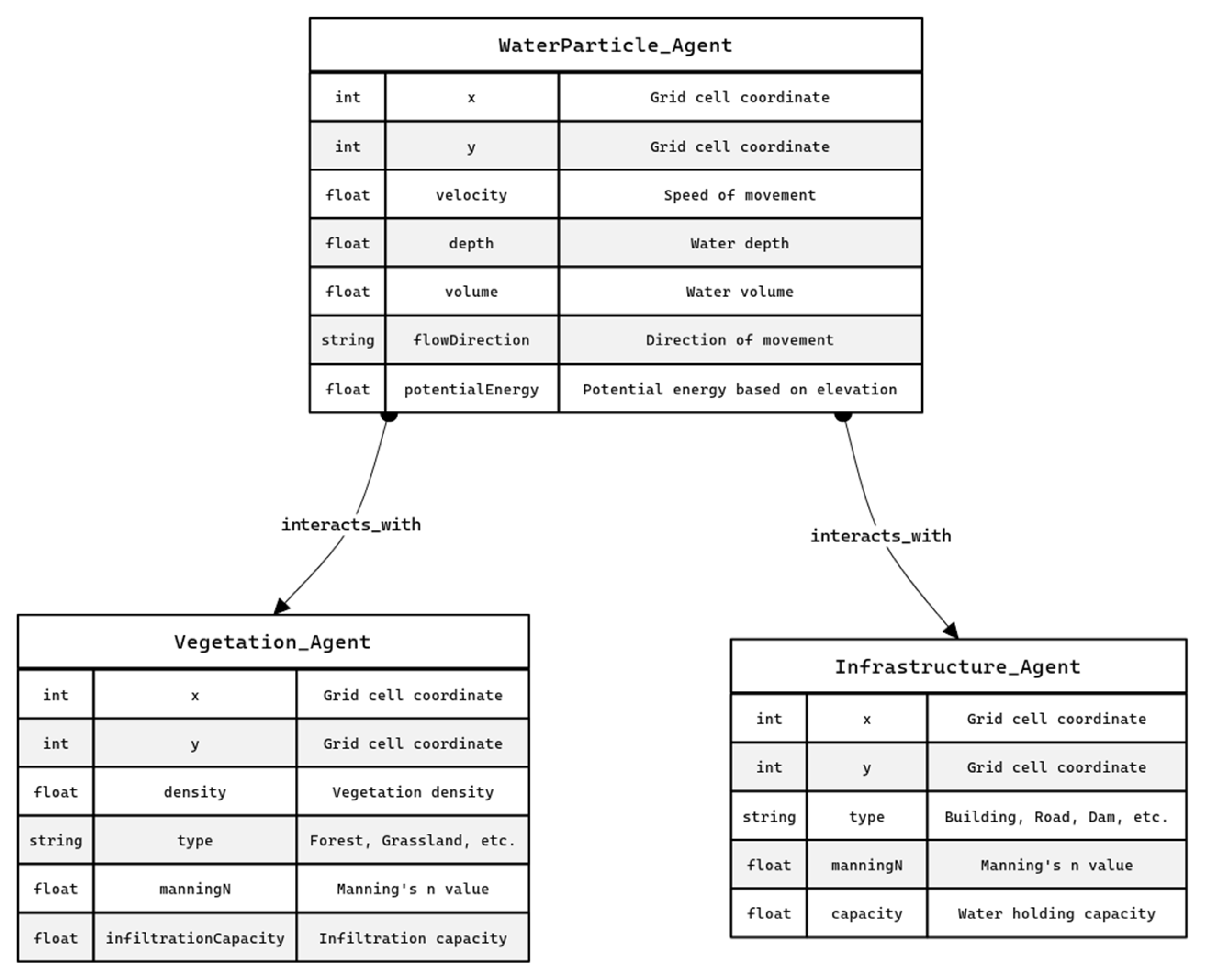

The complex interactions within a flood event are difficult to be represented, yet here agents with their unique properties simulate them, providing a promising approach. More specifically, we attempt to represent individual entities within a flood system as specific autonomous agents. These agents have among other a rule set forming their private strategy, as a result they can capture the dynamics of their role. The proposed agent types are three, namely WaterParticle, VegetationAgent, and InfrastructureAgent (

Figure 1). However, the approach is extendable and more agent types can be added easily.

2.3. Rule-Based System Implementation

The rule-based system is the heart of the approach, its core intelligence that can be found in the agents’ behaviors and hydrological processes simulation. As already discussed, agent interactions are based on their strategies, namely their rule sets. The same is for i.e. the water flow since rules represent the established hydrological principles, simulating their dynamics.

2.3.1. Rule-Based Logic and Modular Design

The rule-based logic is designed to be modular and adaptable. The aim is to allow the representation of complex interactions and environmental conditions. Each rule consists of a set of conditions and a corresponding action. The rule is triggered when the conditions are met and the action is executed. This logic is implemented within the agent's behavior methods, namely its private strategy, enabling them to make context-aware decisions.

2.3.2. Concrete Rule Examples and Computational Implementation

The system is designed to be extensible. New rules can be easily added at any time and they can even modify existing rules if necessary. The examples below depict the statements and function calls of the computational implemented rule-based system. This approach enables a dynamic evaluation of conditions and the execution of corresponding actions.

Water Flow Rule. If a WaterParticle is located at cell (x, y) and the slope of the terrain at (x, y) is greater than 0 (Condition), Move the WaterParticle to the neighboring cell with the lowest elevation (Action).

Computational Implementation (Python).if terrain.slope[y][x] > 0:

next_cell = find_lowest_neighbor(x, y, terrain.elevation)

water_particle.move(next_cell) |

Infiltration Rule. If a WaterParticle is located at cell (x, y) and the VegetationAgent at (x, y) has a non-zero infiltrationCapacity (Condition), Move the WaterParticle to the neighboring cell with the lowest elevation (Action).

Computational Implementation (Python).if vegetation_agent.infiltrationCapacity > 0:

water_particle.volume -= vegetation_agent.infiltrationCapacity * time_step

Interaction with Infrastructure Rule: |

Interaction with Infrastructure Rule. If a WaterParticle encounters an InfrastructureAgent of type "Building" (Condition), Stop the WaterParticle's movement (Action).

Computational Implementation (Python).if infrastructure_agent.type == "Building":

water_particle.velocity = 0 |

2.4. Mathematical Dynamical System Integration

The proposed approach in order to represent flood dynamics and environmental response has to integrate mathematical dynamical systems equations. This way, we are able to model better the water flow, infiltration, and other hydrological processes.

2.4.1. Mathematical Models for Flood Dynamics

The mathematical model used in this approach is based on the shallow water equations. These equations describe the flow of water in a shallow layer and, additionally, they can be integrated effectively with the agent-based model to simulate flood propagation.

The Continuity Equation describes the mass conservation. It is used for various water sources and sinks.

where h is water depth, u and v are flow velocities in the x and y directions, R is rainfall intensity, I is infiltration rate, E is evaporation rate, ET is evapotranspiration rate and Q represents source/sink terms such as groundwater inflow/outflow, artificial water diversions etc.

The Momentum Equations describe the conservation of momentum. For larger-scale simulations, we incorporate the Coriolis effect and wind stress, namely the last two addition part of the equation.

where g is gravitational acceleration, z is terrain elevation, n is Manning's roughness coefficient, f is the Coriolis parameter, T

x and T

y are wind stress components in the x and y directions and ρ is water density.

Furthermore, instead of a simple infiltration rate we use an approximation of Richards' equation to model unsaturated soil water flow. A simplified form is presented below:

where I is the infiltration rate, K

s is the saturated hydraulic conductivity, ψ

f is the wetting front pressure head, ψ

s is the soil surface pressure head, and z

w is the depth of the wetting front.

In order to better model the impact of vegetation, we use the Penman-Monteith equation.

where ET is the evapotranspiration rate, Δ is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve, R

n is net radiation, G is soil heat flux, ρ

a is air density, c

p is specific heat of air, e

s is saturation vapor pressure, e

a is actual vapor pressure, r

a is aerodynamic resistance, γ is psychrometric constant and r

s is the surface resistance.

In cases that wehave to simulate erosion and sediment transport, we use the following exner equation:

where z

b is bed elevation, λ

p is bed porosity and q

s is the sediment transport rate.

2.4.2. Agent-Based Rules and Mathematical Models

As already discussed the proposed methodology combines agent-based rules and mathematical models in an attempt to reach the real-world water systems behaviour as much as possible. In this context, we have the cognitive rules on one side and the predictive analytics on the other. The information exchange is bidirectional which makes the approach more flexible.

The mathematical model, part of which was present in the previous subsection, utilizes the needed predictive analytics. This part can forecast, for instance, a cascading flood event. Suppose that there is a failure of one flood control structure which eventually triggers a chain reaction. In this context, infrastructure agents use a cognitive analysis of the model's predictions and initiate emergency protocols such as rerouting water and adjusting release rates to mitigate the cascading failure. An example of the (Cognitive) rule of the InfrastructureAgent and the function is presented below:

IF predictedCascadingFailure(structureID) THEN initiateEmergencyProtocol(structureID)

FUNCTION initiateEmergencyProtocol(structureID):

alertAdjacentStructures(structureID)

simulateAlternativeRouting(structureID)

adjustReleaseRate(structureID, optimalRate) |

VegetationAgents, on the hand, in a dynamic delta region (x=5, y=8) learn from past flood events and adjust their manningN values using adaptive learning algorithms. An example of such an adaptive learning rule and the function from the mathematical model is presented below, where the manningN value is dynamically adjusted based on learned patterns from historical flood data, directly influencing the friction term in the mathematical model:

manningN[5, 8] = learnAndAdjustManningN(historicalFloodData[5, 8])

FUNCTION learnAndAdjustManningN(data):

learningAlgorithm = loadAdaptiveLearningAlgorithm("DeltaManningN")

RETURN learningAlgorithm.learn(data, currentManningN) |

Furthermore, the mathematical model is related with multi-physics models that simulate hypoxia, saltwater intrusion, and other biogeochemical processes. Of course, such models are needed only in complex interactions that biogeochemical interactions which is not the common case. However, an exmple is presented below for purposes of for completeness purposes. More specifically, the example is about an estuary simulation, where WaterParticle agents interact with a simulated estuary, including saltwater intrusion, nutrient cycling, and aquatic biodiversity.

IF salinity[x, y] > salinityThreshold THEN triggerSaltwaterIntrusionModel(x, y)

IF dissolvedOxygen[x, y] < oxygenThreshold THEN triggerHypoxiaModel(x, y)

IF sedimentLoad[x, y] > nutrientReleaseThreshold THEN triggerBiogeochemicalModel(x, y)

|

Another component of the methodology is related to visualization, a permant request of the civil authorities since they have somehow to understand and use methodologies and tools. In this context, we foresee the use of a virtual reality (VR) environment as an extra component for visualization purposes. This will allow stakeholders to interact with the model using neural interfaces. Part of this example is presented below:

IF neuralInput(user) THEN translateNeuralInputToSimulation(userInput)

IF collaborativeDecision(x, y) THEN implementDecision(x, y) |

It is worth mentioning here that this part of the implementation is quite limited at this point but further development will enrich the available interfaces promoting the proposed methodology eventually as a ready-to-use tool.

Another issue that civil protection authorities are interested in is their policy simulation. To this end, the proposed methodology included rules and agents that form AI dynamic policy networks. For instance, InfrastructureAgents and WaterParticle agents are involved in AI-driven dynamic policy networks and if needed they can adapt to real-time data and evolving socio-economic conditions. An example follows:

floodResponsePolicy = adaptPolicyNetworkWithAI(realTimeData, socioEconomicData)

IF floodEvent(x, y) THEN implementPolicy(floodResponsePolicy) |

Moreover, the parameters of the mathematical model are continuously calibrated using distributed AI learning. For instance, data from sensors and social media, whenever possible, is integrated using distributed AI learning algorithms.

Rules (Distributed AI Learning & Self-Calibration):

modelParameters = aggregateLearnedParametersWithDistributedAI(globalData)

calibrateModel(modelParameters)

Finally, there are rules that deal with the self-replication and repair of the agents.

IF damageDetected(agent) THEN replicateAndRepair()

FUNCTION replicateAndRepair():

replicateAgent()

repairDamagedAgent() |

3. Simulation Scenarios and Case Studies

This section presents parts of some simulation scenarios and case studies to present better the added-value of the approach. In this context, the aim is to discuss critical (what-if) situations and the potential of the methodology for real-time flood forecasting and proactive resilience building.

3.1. Torrent Valley Watershed Case Study

The Torrent Valley watershed has an intricate topography and diverse land cover. For the purposes of this study, we recreated a historical flood event from November 12, 2022, and compared the simulation's outputs with real-world data. Hence, first of all, the simulated flood inundation map was compared with historical flood extent maps using appropriate rules, such as:

Next, the Critical Success Index (CSI) was calculated to be 0.85, resulted from the mathematical expression:

Next, flooding hotspots were detected and reproduced.

Following that, high-resolution LiDAR data was used to compare simulated water surface elevations with observed elevations. This resulted in a Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 0.4 meters based on the following mathematical expression:

A temporal validation were conducted too, where the simulated hydrograph at the “Torrent Valley Outlet” gauge was compared with observed streamflow data.

In this context, the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) was calculated to be 0.92 based on:

This revealed that the timing and magnitude of the flood peak were accurately captured. Of course, vegetation and infrastructural impact could not left without a notice. In this case study, VegetationAgents in forested areas reduced WaterParticle velocity while InfrastructureAgents representing buildings created localized flooding. Hence, agents dynamically influenced the mathematical parameters of the model. For instance, high VegetationAgent density led to increased ManningN in the mathematical model, and high velocity from the model led to WaterParticle flow direction changes.

IF vegetationType == "Forest" THEN waterParticleVelocity = waterParticleVelocity * (1 - vegetationDensity * ManningN).

IF infrastructureType == "Building" THEN waterParticleVelocity = 0. |

It is worth mentioning that the dam, controlled by the InfrastructureAgent, managed downstream flow.

To sum up, in this case study, the proposed approach had a high degree of accuracy in replicating the historical flood event. CSI and RMSE metrics revealed that the model accurately captured the extent and depth of the flood while the high NSE value revealed an ability to reproduce the timing and magnitude of the flood peak. Moreover, VegetationAgents simulated effectively the role of vegetation in mitigating flood risk while InfrastructureAgents represented well the impact of urban development and dam operations. This dynamic interaction between agents and the mathematical model enabled a realistic simulation of the flood event. As a result, the proposal seems promising for reproducing real-world flood dynamics while its flexibility can simulate complex interactions, turning it to a flood risk assessment tool.

3.2. Scenario Analysis: Flood Resilience

An obvious question is how the methodology will perform in future flood risks. To this end, we conducted some what-if scenario analysis. These simulations aimed to explore the impacts of potential changes in rainfall, land use, and flood management policies. First is discussed a climate change scenario which involves increased rainfall intensity. For that scenario, we assumed that the rainfall intensity increased by 20%.

This increase, as it was expected, led to a significant rise in peak streamflow and flood inundation area. The AI policy network responded by dynamically adjusting dam release rates and activating flood barriers in vulnerable zones. The peak flow increase was calculated then revealing a 30% increase in the peak streamflow, indicating the high sensitivity of the watershed to increased rainfall.

where ΔR represents the percentage increase in rainfall.

The second scenario was related to land use change, including deforestation and urbanization.

This resulted in a significant increase in surface runoff and a reduction in infiltration capacity. The simulation revealed a 40% increase in surface runoff, leading to more extensive and rapid flooding.

where ΔA represents the increase in impervious area and I represents the infiltration rate.

The third scenario was related to nature-based solutions, including a green infrastructure implementation such as constructed wetlands and permeable pavements. This resulted in a significant reduction in peak streamflow and flood inundation.

where ΔI represents the increase in infiltration capacity due to green infrastructure.

The VegetationAgents in the wetland areas increased the infiltration capacity and slowed down the WaterParticle agents. The simulation revealed a 25% reduction in peak streamflow. This means that green infrastructure is effective in mitigating flood risk.

The fourth scenario was about Adaptive Management and, thus, it was related to dynamic dam release policies. Specifically, dam release policies were dynamically adjusted based on weather forecasts and sensor data.

The AI policy networks adjusted dam release rates in anticipation of heavy rainfall events, effectively reducing downstream flood risk. The dam release rate was dynamically adjusted according to the forecasted rain fall, and the real time water level of the dam .The results of the dynamic dam release, was compared with the result of a static dam release, and the dynamic dam release, showed much better results.

To sum up, these scenario analysis confirmed that the proposed approach can deal pretty well with flood risk changes. Furthermore, the first chosen use cases depicted the need for proactive flood management strategies while the green infrastructure case connected the nature-based solutions with flood resilience.

3.3. Real-Time Simulation and Early Warning

Although, the first goal of the methodology is to be used for simulation providing valuable information that could lead to conclusion about future changes in the flood risk of an area, it is important to move beyond that to a proactive flood management and early warning system. Although, it is not easy and a number of parameters can affect real-time conditions, the proposed approach already handles the main dynamics while it is easily extendable. As discussed, the approach can integrate data from various real-time sources, including rainfall intensity from weather radar and rain gauges, streamflow data from gauging stations, water depth and velocity from sensor networks as well as some social media feeds.

Hence, there is a continuous update in the simulation parameters based on incoming data. This way the underlying model will remain updated to current conditions.

where S

t is the simulation state, u

t is the input data, y

obs is the observed data, and K is the Kalman gain. Mention that Kalman filters is a data assimilation technique that merge observations with simulation.

Next, the approach can generate some flood alerts.

These alerts can be customized based on location and severity. This way local communities will receive relevant information. Of course, these alerts can be transmitted through various channels such as mobile apps, SMS notifications, sirens or other emergency response systems. Yet, currently the system is not connected with such software or infrastructural.

However, adaptation strategies are already available.

The ultimate goal is to eventually transform flood management from a reactive to a proactive approach.

4. Computational Complexity

The proposed approach involves agent-based modeling and mathematical dynamical analysis, as a result, it has computational demands.More specifically, there are many complex interactions between a large number of agents while at the same time the system should partially solve differential equations (PDEs) representing hydrological processes. In this context, this section discusses complexity issues. First, we study the computational complexity of the agent-based component since there are many agents and many interaction rules.

The number of agents is stated as N

a while C

i is the average cost of an agent interaction. Hence, the total computational cost of the agent interactions will be:

For instance, with 106 WaterParticle agents and an average interaction cost of 10−5 seconds per interaction, the total cost is 10 seconds per simulation step. Another parameter that affects the complexity is the spatial resolution. The higher the resolution grid is, the more agents are needed and the computational cost is unavoidable higher.

As far as it concerns the mathematical dynamical analysis complexity, the approach obviously requires numerical solutions that have a computational cost. Once again the complexity depends on the grid resolution (Nx, Ny), the time step (Δt), and the number of iterations (Nt).

For instance, if we use an explicit finite difference scheme for the shallow water equations, the computational cost per time step is proportional to , while f we use a Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition the total cost is proportional to .

A calculation example, estimating agent interaction cost, is the following where we have a watershed discretized into a grid of 1000 x 1000 cells. This grid hosts WaterParticle agents, with an average density of 5 agents per cell. Hence we have agents. If each agent has to check its neighboring cells for interactions, like collision etc, with an average of 8 neighbors and each interaction check takes 10−6 seconds, then the cost will be seconds per agent. As a result, the total interaction cost will be seconds per time step.

This calculation reveals that just the agent-agent interaction part of the simulation takes 40 seconds per time step. It is obvious that if we wanted to run the simulation for an event that lasts several hours, using a time step of 1 second, the agent interaction calculations alone would take a very long time.

We now use another example to calculate RMSE for water depth for checking model validation. In this example we have a small section of an watershed with 5 observation points depicting the measured water depth during a flood event. Additionally, we have the corresponding simulated water depth values from our approach.

Table 9.

This is a table. Tables sho.

Table 9.

This is a table. Tables sho.

| Observation Point |

Observed Depth (m) (yi) |

) |

| 1 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

| 2 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

| 3 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

| 4 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

| 5 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

First, we calculate the squared difference for each point:

(2.5−2.3)2 =0.04

(1.8−2.0)2 =0.04

(3.0−2.8)2=0.04

(1.5−1.7)2=0.04

(2.2−2.4)2=0.04

Next, we sum the squared differences 0.04+0.04+0.04+0.04+0.04=0.20 and divide by the number of points (n = 5) 0.20/5=0.04. Finally, meters. This indicates that the average difference between the observed and simulated water depths at these 5 points.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a novel agent-based computational approach was discussed. It is a framework designed for flood resilience that involves rule-based agent modeling with mathematical dynamical analysis. This approach deals with the increasing threat of flooding and the limitations of traditional, static flood management strategies. It proposes a dynamic and adaptive methodology suitable for risk assessment and scenario analysis. Among the key findings is that it can deal with complex flood dynamics, simulating the interactions between environmental factors, infrastructure, and water flow. A number of case studied were used to validate and check the approach, with metrics such as CSI, RMSE, and NSE indicating agreement between simulated and observed data. This analysis revealed the capability of the approach to deal with future flood risks and mitigation strategies. Another issue that was taken into account, was the need for early warning systems, namely proactive flood management. Of course, the approach should be continuously updated regarding the simulation parameters in order to support better the emergent situations and response. Furthermore, the cognitive rules and bidirectional information exchange between agents and the mathematical model proved to be a tool for more realistic simulation of complex hydrological processes. However, we acknowledge the limitations of the approach, including computational complexity and data requirements. Further research, of course, is needed to address these limitations. Specifically, future work will focus on improving computational efficiency by integrating more advanced AI techniques.

In conclusion, the BRIDGES approach represents a significant step in the field of flood resilience since it integrates some advanced computational techniques. It provides a dynamic and adaptive tool for flood risk assessment and as such it can support more effective flood management strategies, contributing to more resilient communities. Hence, in the era of the continuous increasing challenges of climate change and urbanization, innovative approaches like the proposed one will be crucial for lives and the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.; methodology, K.K.; validation, K.K.; formal analysis, K.K.; investigation, K.K.; resources, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; visualization, K.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IAs |

Intelligent Agents |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Wang, L.; Cui, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Manandhar, B.; Nitivattananon, V.; Fang, X.; Huang, W. A review of the flood management: From Flood Control to Flood Resilience. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rözer, V.; Mehryar, S.; Surminski, S. From Managing Risk to Increasing Resilience: A Review on the Development of Urban Flood Resilience, Its Assessment and the Implications for Decision Making. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, O. M.; van de Lindt, J. W. Understanding flood risk in the context of community resilience modeling for the built environment: research needs and trends. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure 2020, 7, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norizan, N. Z. A.; Hassan, N.; Yusoff, M. M. Strengthening flood resilient development in malaysia through integration of flood risk reduction measures in local plans. Land Use Policy 2020, 102, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, G. Towards flood risk reduction: Commonalities and differences between urban flood resilience and risk based on a case study in the Pearl River Delta. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2023, 86, 103568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrasch, L.; Restemeyer, B.; Klenke, T. The ‘Flood Resilience Rose’: A management tool to promote transformation towards flood resilience. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.; Werritty, A.; Ball, T.; Black, A. Environmental vulnerability and resilience: Social differentiation in short- and long-term flood impacts. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 2020, 46, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, S.; Lu, Z.; Song, Y.; Yu, S. Towards an AI-driven framework for multi-scale urban flood resilience planning and design. Computational Urban Science 2021, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Kuehnert, J.; Fraccaro, P.; Meuriot, O.; Ishikawa, T.; Edwards, B.; Stoyanov, N.; Remy, S. L.; Weldemariam, K.; Assefa, S. AI for climate impacts: applications in flood risk. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 2023, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Fan, C.; Farahmand, H.; Coleman, N.; Esmalian, A.; Lee, C.-C.; Patrascu, F. I.; Zhang, C.; Dong, S.; Mostafavi, A. Smart flood resilience: harnessing community-scale big data for predictive flood risk monitoring, rapid impact assessment, and situational awareness. Environmental Research Infrastructure and Sustainability 2022, 2, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, M.; Asadzadeh, A.; Vafeidis, A.; Fekete, A.; Kötter, T. A multi-criteria approach for assessing urban flood resilience in Tehran, Iran. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 35, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, A.; Campbell, K.; Szoenyi, M.; McQuistan, C.; Nash, D.; Burer, M. Development and testing of a community flood resilience measurement tool. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2017, 17, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.L.; Van Niekerk, A.; Grohmann, C.H.; Muller, J.-P.; Hawker, L.; Florinsky, I.V.; Gesch, D.; Reuter, H.I.; Herrera-Cruz, V.; Riazanoff, S.; et al. Digital Elevation Models: Terminology and Definitions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie J., C.; Smit L., J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Digital elevation model (DEM) fusion: pre-processing, methods and applications. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 188, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, S.; Rengarajan, R. Evaluation of Copernicus DEM and Comparison to the DEM Used for Landsat Collection-2 Processing. Remote Sens 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, M.; Cocero, D. Using the European CORINE Land Cover Database: A 2011–2021 Specific Review. In: De Lázaro Torres, M.L., De Miguel González, R. (eds) Sustainable Development Goals in Europe. Key Challenges in Geography 2023. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- García-Monteiro, S.; Sobrino, J.; Julien, Y.; Sòria, G.; Skokovic, D. Surface Temperature trends in the Mediterranean Sea from MODIS data during years 2003–2019. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2021, 49, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, W.; Hansen, M. C.; Potapov, P. An evaluation of Landsat, Sentinel-2, Sentinel-1 and MODIS data for crop type mapping. Science of Remote Sensing 2021, 3, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboudian, M.; Kerachian, R.; Motlaghzadeh, K.; Ashrafi, S. Application of multi-agent decision-making methods in hydrological ecosystem services management. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales-Inca, C.; Calle, M.; Croghan, D.; Torabi Haghighi, A.; Marttila, H.; Silander, J.; Alho, P. Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) in the Integrated Hydrological and Fluvial Systems Modeling: Review of Current Applications and Trends. Water 2022, 14, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitzke, B.; Adamatti, D. Multiagent System and Rainfall-Runoff Model in Hydrological Problems: A Systematic Literature Review. Water 2021, 13, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).