Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collection

2.2. Acorn Germination

2.3. Substrates Characterization

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

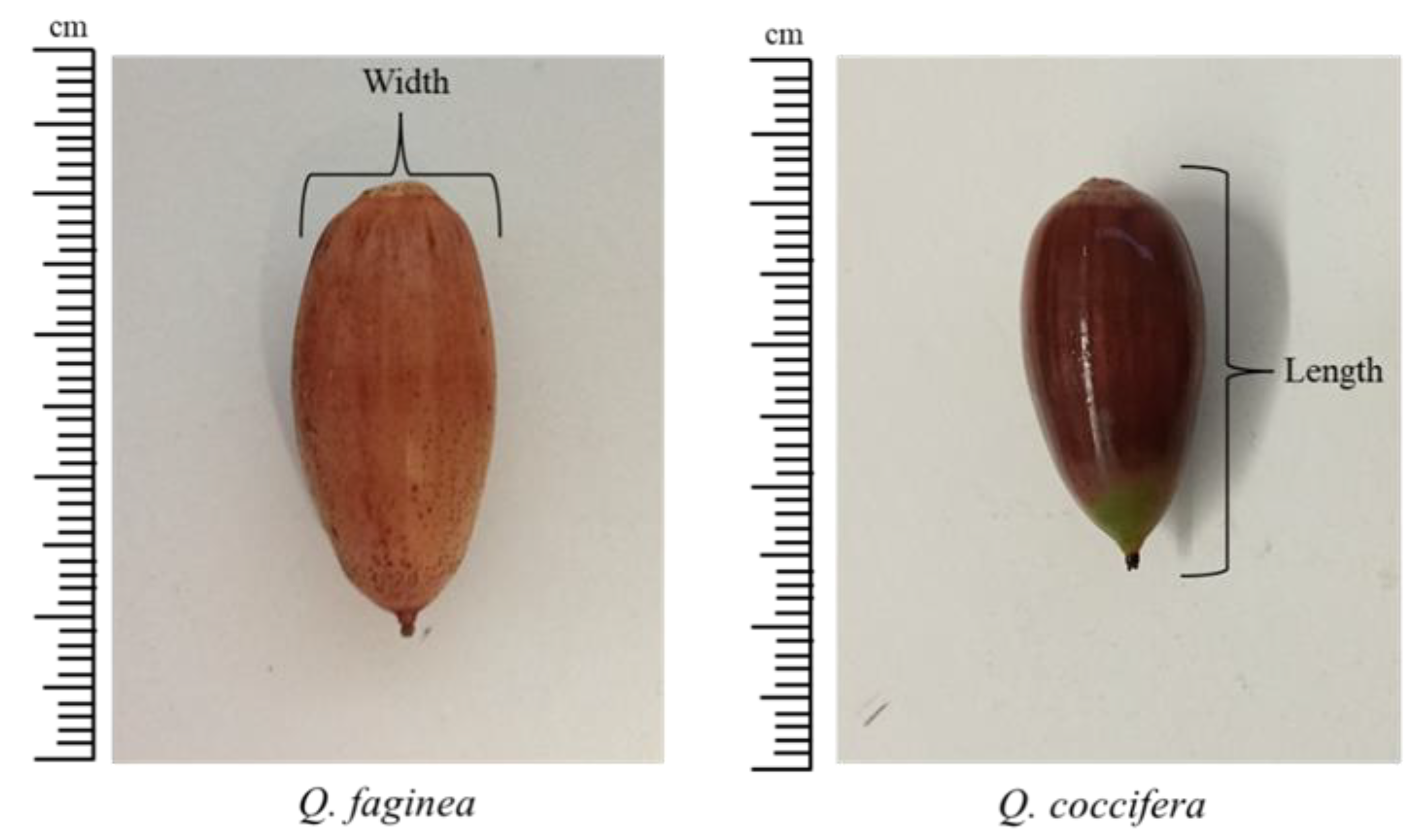

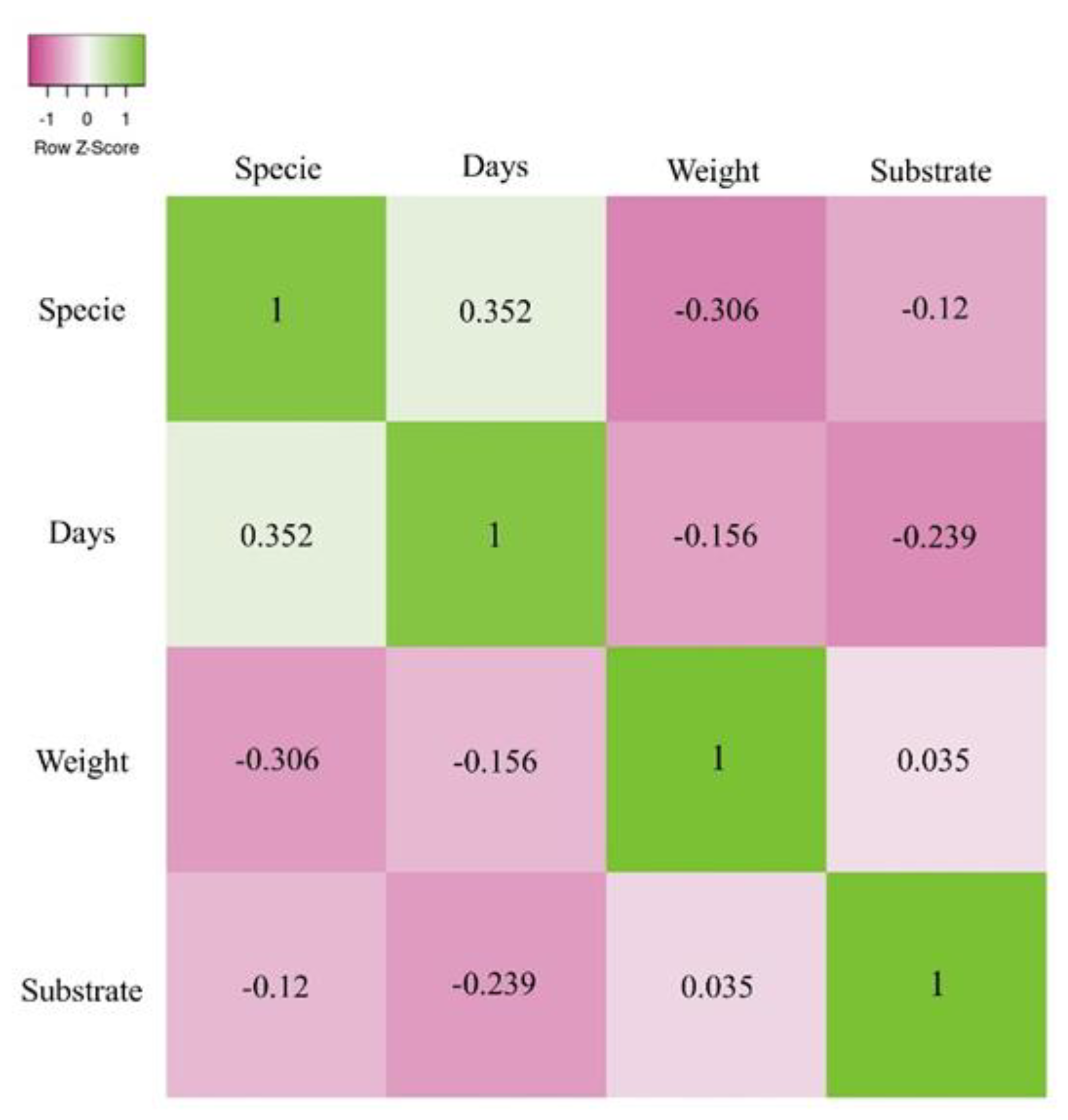

3.1. Physical Characterization of Acorns

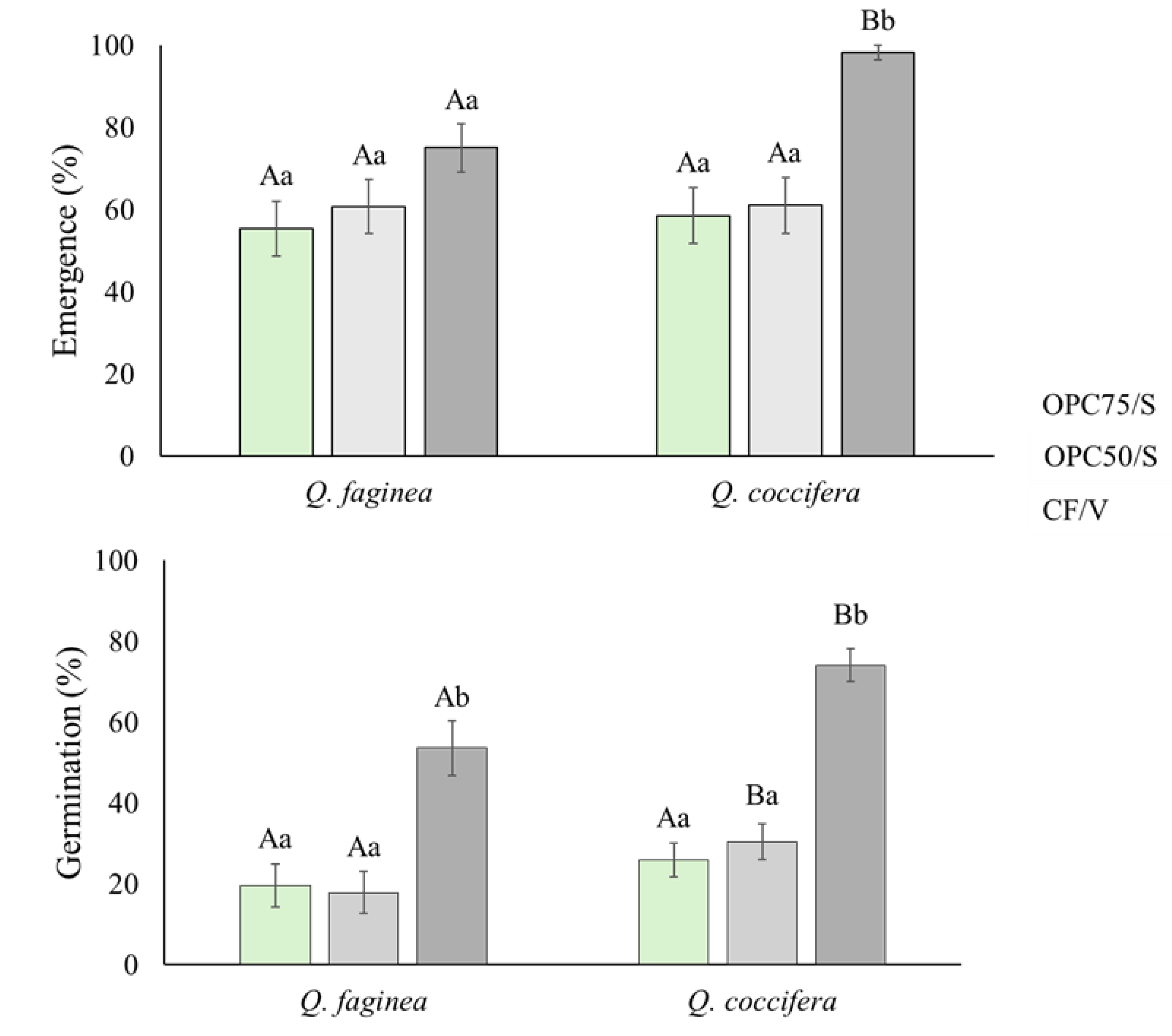

3.2. Root Emergence and Germination

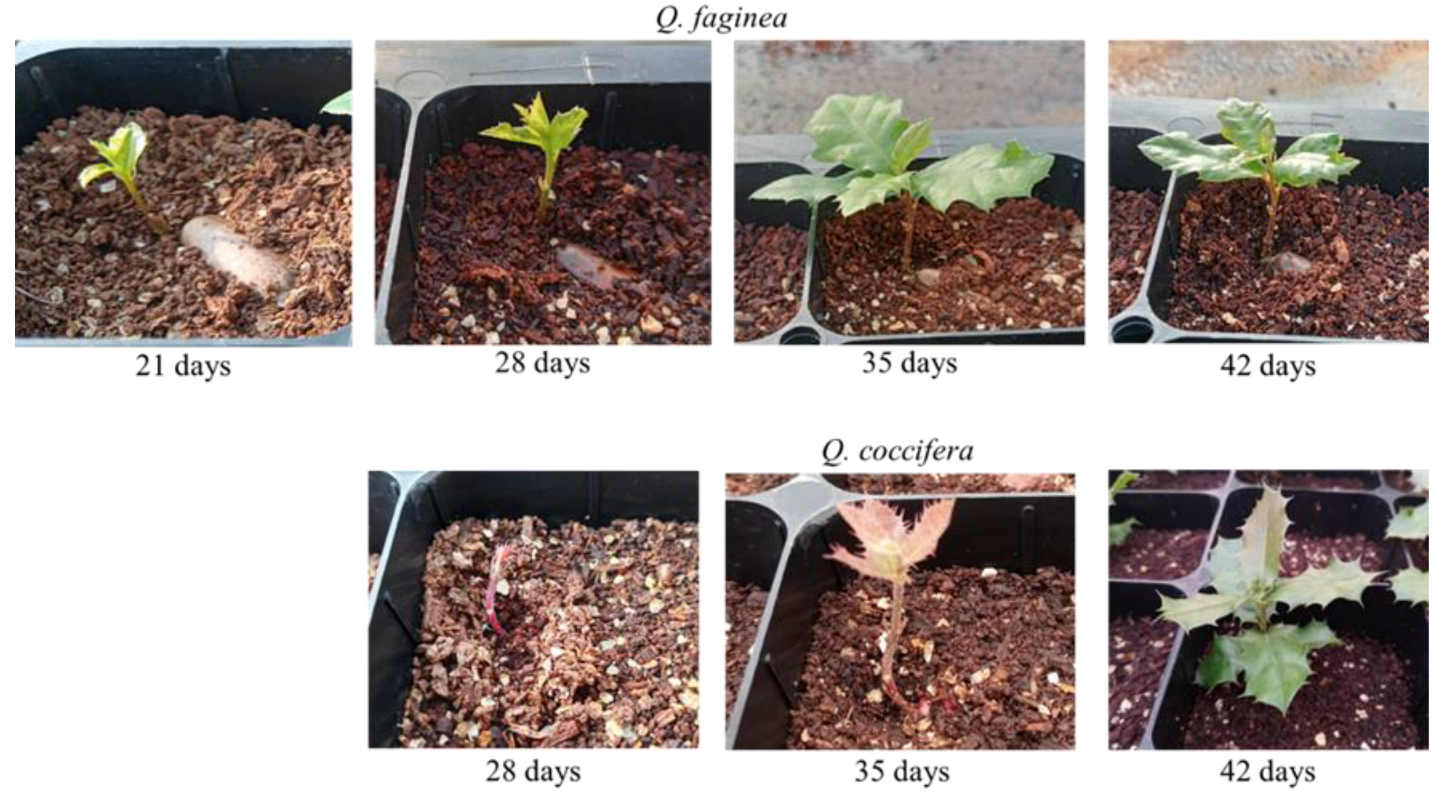

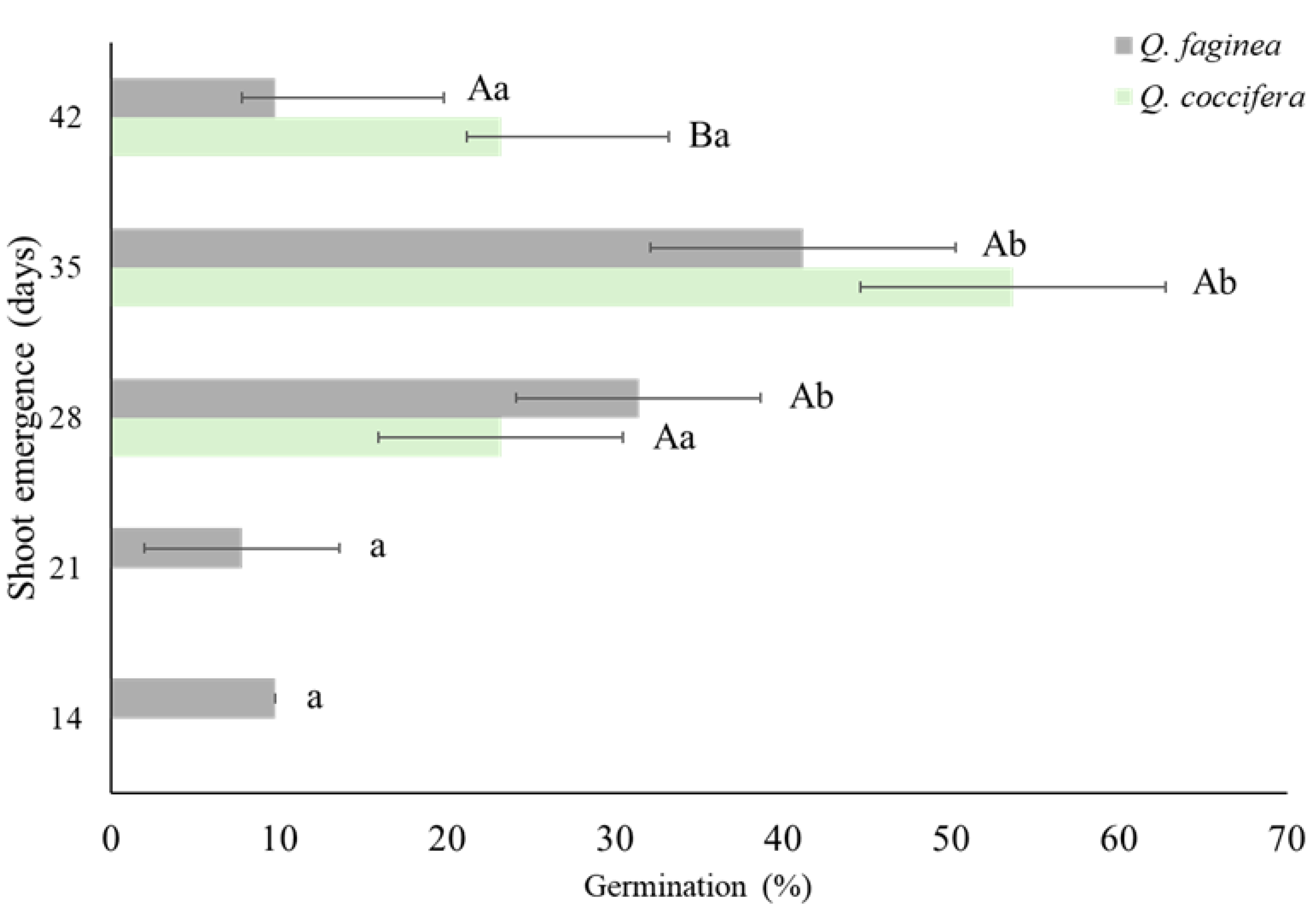

3.3. Shoot Emergence Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Characterization of Acorns

4.2. Emergence and Germination

4.3. Effect of Substrate on Germination

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OPC | Olive Pomace Compost |

| OPC75/S | Olive Pomace Compost and Sand in a ratio of 75/25% |

| OPC50/S | Olive Pomace Compost and Sand in a ratio of 50/50% |

| CF/V | Coconut Fiber and Vermiculite |

References

- Moreno, G.; S, A. ; S., B.; J, C.-D. Agroforestry systems of high nature and cultural value in Europe: provision of commercial goods and other ecosystem services. Agroforest Syst. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Crespo, I.M.; Silla, F.; Jiménez Del Nogal, P.; Fernández, M.J.; Martínez-Ruiz, C.; Fernández-Santos, B. Effect of the Mother Tree Age and Acorn Weight in the Regenerative Characteristics of Quercus Faginea. Eur. J. Forest Res. 2020, 139, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, V.; Villar, R.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M. Maternal Influences on Seed Mass Effect and Initial Seedling Growth in Four Quercus Species. Acta Oecologica 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Campelo, F.; Nabais, C. Environment Controls Seasonal and Daily Cycles of Stem Diameter Variations in Portuguese Oak (Quercus Faginea Lambert). Forests 2022, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltez-Mouro, S.; García, L.V.; Freitas, H. Influence of Forest Structure and Environmental Variables on Recruit Survival and Performance of Two Mediterranean Tree Species (Quercus Faginea L. and Q. Suber Lam.). Eur.J. Forest Res. 2009, 128, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Altay, V. Role of Quercus Coccifera (= Q. Calliprinos) in the Light of Climate Change Scenarios in the Mediterranean Basin. Plant Fungal Res. [CrossRef]

- Stefi, A.L.; Nikou, T.; Papadopoulou, S.; Kalaboka, M.; Vassilacopoulou, D.; Halabalaki, M.; Christodoulakis, N.S. The Response of the Laboratory Cultivated Quercus Coccifera Plants to an Artificial Water Stress. Plant Stress 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilagrosa, A.; Cortina, J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Bellot, J. Suitability of Drought-Preconditioning Techniques in Mediterranean Climate. Restor. Ecol. 2003, 2, 208–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Espelta, J.M.; Hampe, A. Managing Forest Regeneration and Expansion at a Time of Unprecedented Global Change. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 2310–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Fonseca, T.F. Influence Management and Disturbances on the Regeneration of Forest Stands. Front. For. Glo. Change 6. [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-González, A.; Andivia, E.; Hampe, A. Revegetation through Seeding or Planting: A Worldwide Systematic Map. Environ. Manage. 2023, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Why Seedlings Survive: Influence of Plant Attributes. New Forests 2012, 43, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, B.; Maltoni, A.; Jacobs, D.F.; Tani, A. Container Effects on Growth and Biomass Allocation in Quercus Robur and Juglans Regia Seedlings. Scand. J. For. Res. 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Â.; Fabião, A. ; Gonçalves, Ana Cristina; Correia, Alexandre Vaz O Carvalho-Cerquinho em Portugal, Ed.; ISA Press: Lisboa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Warsaw, A.L.; Fernandez, R.T.; Cregg, B.M.; Andresen, J.A. Container-Grown Ornamental Plant Growth and Water Runoff Nutrient Content and Volume Under Four Irrigation Treatments. Horts 2009, 44, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pezeshki, S.R.; Goodwin, S. Effects of Soil Moisture Regimes on Photosynthesis and Growth in Cattail (Typha Latifolia). Acta Oecologica 2004, 25, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upretee, P.; Bandara, M.S.; Tanino, K.K. The Role of Seed Characteristics on Water Uptake Preceding Germination. Seeds 2024, 3, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reho, M.; Vilček, J.; Torma, S.; Koco, Š.; Lisnyak, A. Influence of Soil Substrate on Success of Growing of of English Oak (Quercus Robur, L.) Seedlings: Key Study in Conditions of Forest-Steppe Ukraine. In Prime Archives in Environmental Research; Vide Leaf, Hyderabad, 2023. ISBN 978-93-92117-15-2.

- Cann, J.; Tang, E.; Thomas, S.C. Biochar and Deactivated Yeast as Seed Coatings for Restoration: Performance on Alternative Substrates. Seeds 2024, 3, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, R.; Falace, A.; De la Fuente, G.; Della Torre, C. Ex-Situ Restoration of the Mediterranean Forest-Forming Macroalga Ericaria Amentacea: Optimizing Growth in Culture May Not Be the Key to Growth in the Field. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholkhal, D.; Benmahioul, B. Effects of Substrate on the Germination and Seedling Growth of Quercus Suber L. Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 2021, 64, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvino, F. de O.; Rayol, B.P. Different substrata effects in the germination of Ochroma Pyramidale (Cav. ex Lam.) urb. (Bombacaceae). Ciência Florestal 17. [CrossRef]

- Piva, A.L.; Mezzalira, E.J.; Santin, A.; Schwantes, D.; Klein, J.; Villa, F.; Tsutsumi, C.Y.; Nava, G.A. Mergence and Initial Development of Cape Gooseberry (Physalis Peruviana) Seedlings with Different Substrates Compositions. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 6579–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, M.; Awad, S.; Villot, A.; Abderrabba, M.; Tazerout, M. Heterogeneous Acid Catalyst Preparation from Olive Pomace and Its Use for Olive Pomace Oil Esterification. Renew. Energy. 2021, 165, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.B.; Oliveira, A.L.; Costa, C.; Nunes, J.; Vicente, A.A.; Pintado, M. Total and Sustainable Valorisation of Olive Pomace Using a Fractionation Approach. Applied Sci. 2020, 10, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermeche, S.; Nadour, M.; Larroche, C.; Moulti-Mati, F.; Michaud, P. Olive Mill Wastes: Biochemical Characterizations and Valorization Strategies. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1532–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, D.D.; Said-Pullicino, D.; Proietti, P.; Nasini, L.; Gigliotti, G. Utilization of Olive Husks as Plant Growing Substrates: Phytotoxicity and Plant Biochemical Responses. Compost Sci. Util. 2011, 19, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameziane, H.; Nounah, A.; Khamar, M.; Zouahri, A. Composting Olive Pomace: Evolution of Organic Matter and Compost Quality. Agron. Res. [CrossRef]

- Sempiterno, C.; Fernandes, R.; Dias, A.; Fitas, V. Valorização Agronómica de Bagaço Húmido Compostado e não Compostado – Impacto no Desenvolvimento de Lolium perenne L. In Proceedings of the X National Symposium on Olive Growing, Bragança, Portugal, 2024., 23–25 October.

- Afonso, A.; Nunes, C. Aplicações e Soluções Em SPSS. Universidade de Évora, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tilki, F. Influence of Acorn Size and Storage Duration on Moisture Content, Germination and Survival of Quercus Petraea (Mattuschka). New For. 2010, 18, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.M. Bigger is not always better: conflicting selective pressures on seed size in Quercus ilex. Evolution 2004, 58, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, V.K.; Tamta, S.; Nandi, S.K.; Rikhari, H.C.; Palni, L.M.S. Does acorn weight influence germination and subsequent seedling growth of central himalayan oaks? J. Trop. For. Sci. 2003, 15, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Montes De Oca, E.J.; Badano, E.I.; Silva-Alvarado, L.E.; Flores, J.; Barragán-Torres, F.; Flores-Cano, J.A. Acorn Weight as Determinant of Germination in Red and White Oaks: Evidences from a Common-Garden Greenhouse Experiment. Ann. For. Sci. 2018, 75, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, S.; Ivanković, M.; Vujnović, Z.; Lanšćak, M.; Gradečki Poštenjak, M.; Bogunović, S.; Gavranović Markić, A. Acorn Yields and Seed Viability of Pedunculate Oak in a 10-Year Period in Forest Seed Objects across Croatia. SEEFOR 2022, 13, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Santos, B.; Moro, D.; Martínez-Ruiz, C.; Fernández, M.J. Efectos del peso de la bellota y de la edad del árbol productor en las características regenerativas de Quercus ilex. Avances en la restauración de sistemas forestales. Técnicas de implantación. University of Salamanca, 2013, 197-202.

- García-De La Cruz, Y.; López-Barrera, F.; Ramos-Prado, J.M. Germinación y Emergencia de Plántulas de Cuatro Especies de Encino Amenazadas. MYB 2016, 22, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.S. Dormancy Break and Germination Requirements in Acorns of Two Bottomland Quercus Species (Sect. Lobatae ) of the Eastern United States with References to Ecology and Phylogeny. Seed Sci. Res. 2020, 30, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrzębowski, S.; Ukalska, J.; Walck, J.L. Does the Lag Time between Radicle and Epicotyl Emergences in Acorns of Pedunculate Oak (Quercus Robur L.) Depend on the Duration of Cold Stratification and Poststratification Temperatures? Modelling with the Sigmoidal Growth Curves Approach. Seed Sci Res. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tilki, F.; Alptekin, C.U. Germination and Seedling Growth of Quercus Vulcanica: Effects of Stratification, Desiccation, Radicle Pruning, and Season of Sowing. New For. 2006, 32, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhou, H.; Ning, R. Research Progress on Dormancy Mechanism and Germination Technology of Kobresia Seeds. Plants 2022, 11, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandón, M.; Bigatton, E.D.; Guerrero-Sánchez, V.M.; Hernández-Lao, T.; Rey, M.-D.; Jorrín-Novo, J.V.; Castillejo, M.A. Identification of Proteases and Protease Inhibitors in Seeds of the Recalcitrant Forest Tree Species Quercus Ilex. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 907042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimi, N.; Dussert, S.; Vaissayre, V.; Ghouil, H.; Doulbeau, S.; Costantini, C.; Ammari, Y.; Joët, T. Variation in Seed Traits among Mediterranean Oaks in Tunisia and Their Ecological Significance. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canet, R.; Pomares, F.; Cabot, B.; Chaves, C.; Ferrer, E.; Ribó, M.; Albiach, M.R. Composting Olive Mill Pomace and Other Residues from Rural Southeastern Spain. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2585–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmão, A.G.; Toloto, M.; Segatelli, A.B.; Fonseca, F.; Cortez, P.; Figueiredo, T.D.; Hernández, Z. Efeito de diferentes substratos na taxa de crescimento de Quercus suber L. Revista de Ciências Agrárias. [CrossRef]

- Arenas, M.; Vavrina, C.S.; Cornell, J.A.; Hanlon, E.A.; Hochmuth, G.J. Coir as an Alternative to Peat in Media for Tomato Transplant Production. HortSci. 2002, 37, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Physical, Chemical and Biological Properties of Coir Dust. Acta Hortic. 1997, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Rueda, M.; Domínguez-Vidal, A.; Aranda, V.; Ayora-Cañada, M.J. Monitoring the Composting Process of Olive Oil Industry Waste: Benchtop FT-NIR vs. Miniaturized NIR Spectrometer. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarezi, R.S.; Lin, X.; Gonzalez Neira, A.C.; Tabay Zambon, F.; Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.-H.; Fan, G. Substrate pH Influences the Nutrient Absorption and Rhizosphere Microbiome of Huanglongbing-Affected Grapefruit Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 856937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, C.; Bartsch, N. Germination of Acorns and Development of Oak Seedlings (Quercus Robur L.) Following Flooding. J. For. Sci. 2007, 53, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oneț, A.; Teușdea, A.; Boja, N.; Domuța, C.; Oneț, C. Effects of Common Oak (Quercus Robur L.) Defolition on the Soil Properties of an Oak Forest in Western Plain of Romania. Ann. For. Res. 2016, 59, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | N | Q. faginea | Q. coccifera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 168 | 5.18 ± 0.08 b | 4.28 ± 0.07 a |

| Lenght | 168 | 32.25 ± 0.18 b | 31.74 ± 0.15 b |

| Width | 168 | 16.06 ± 0.09 b | 14.09 ± 0.09 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).