Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model of Electroconvection in Potentiodynamic Mode in Half of Desalination Channel with Ideally Selective Cation Exchange Membrane (CEM) with Modified Surface

2.1. Physical Statement: Solution Domain

2.2. Boundary Value Problem for the System of Navier-Stokes and Nernst-Planck-Poisson Equations

3. Results of Numerical Analysis

3.1. Calculation Parameters Used for Numerical Solution

3.2. Structure of the Solution Flow

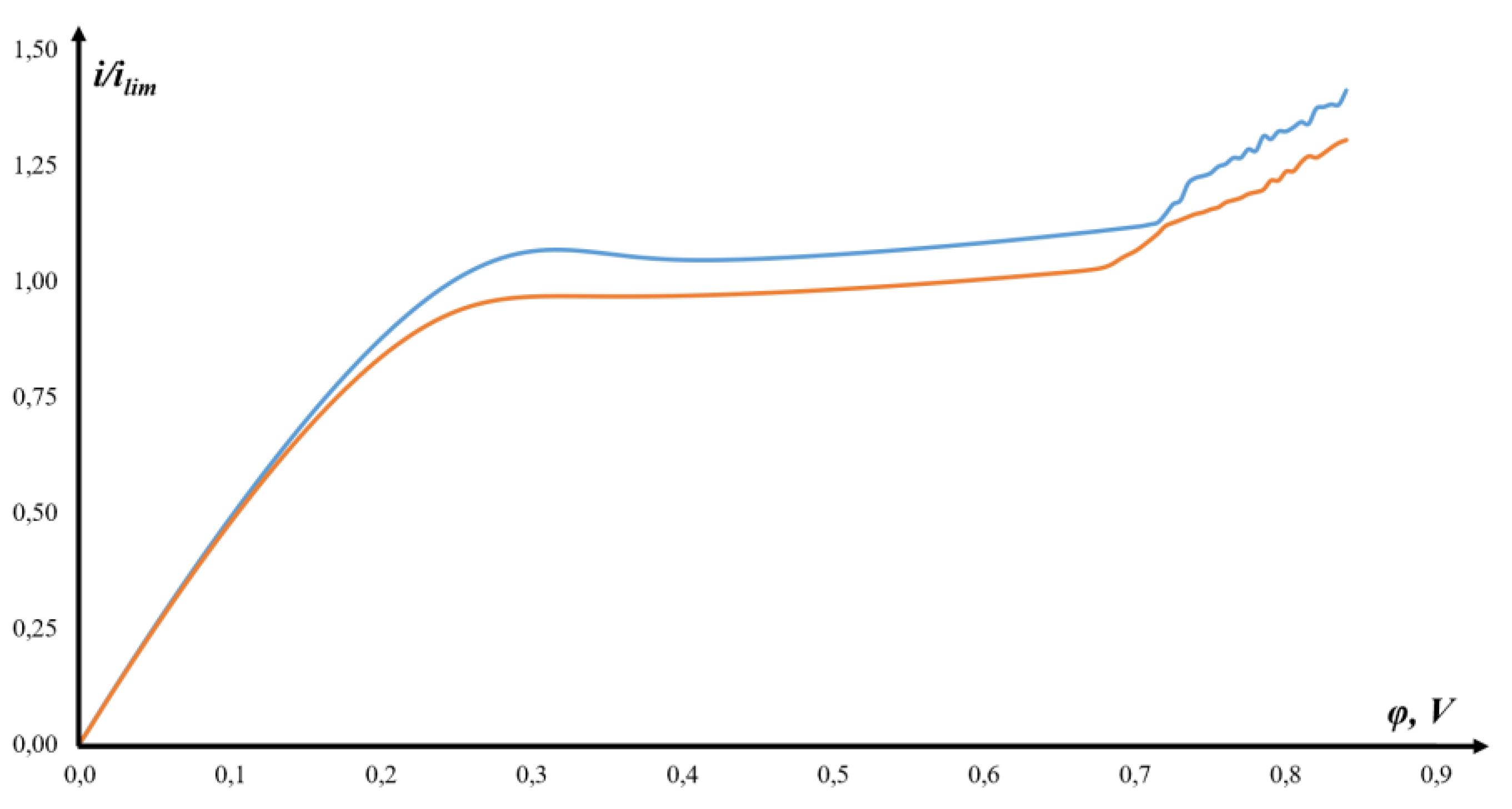

3.2. CVC and Its Description

3.3. Verification of Results

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menachem, E.; William P. The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2011, 333, 712-7. [CrossRef]

- Yuqing, S.; Xinyan, T. et al. Solar-driven interfacial evaporation for sustainable desalination: Evaluation of current salt-resistant strategies. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023. 474. 145945. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huo, E. Opportunities and Challenges of Seawater Desalination Technology. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10:960537. [CrossRef]

- Jay, W.; Menachem E. Materials for Next-Generation Desalination and Water Purification Membranes. Nature Reviews Materials. 2016, 1. 16018. [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Dydek, E.; Han, J. et al. Overlimiting Current and Shock Electrodialysis in Porous Media. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2013, 29. [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Wang, K. M. Electroconvection Near Electrochemical Interfaces: Experiments, Modeling, and Computation. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2020. 52:509–29. [CrossRef]

- Utenov, M. K.; Uzdenova, A. M.; Kovalenko A. et al. Basic mathematical model of overlimiting transport enhanced by electroconvection in flow-through electrodialysis membrane cells. J. Memb. Sci. 2013, 447, 190–202.

- Probstein, R.F. Physicochemical hydrodynamics: An introduction; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, 1994; 416p.

- Dukhin, S. S. Electrokinetic phenomena of the second kind and their applications. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 1991, 35, 173–196. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, I.; Shtilman, L. Voltage against current curves of cation exchange membranes. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 1979, 2, 75, 231. [CrossRef]

- Urtenov, M.A.; Kirillova, E.V.; Seidova, N.M.; Nikonenko, V.V. Decoupling of the Nernst-Planck and Poisson equations. Application to a membrane system at overlimiting currents. J Phys Chem B. 2007, 27;111(51):14208-22. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rjal, R., Leibowitz, N., Park, S., Zaltzman, B., Rubinstein, I. & Yossifon, G. Signature of electroconvective instability in transient galvanostatic and potentiostatic modes in a microchannel-nanoslot device. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2019, 4 (8), 084203. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Townsend, A.; Archer, L.A.; Koch, D.L. Electroconvection near an ion-selective surface with Butler–Volmer kinetics. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2022;930:A26. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Davidson, S.M.; Mani, A.. Characterization of chaotic electroconvection near flat inert electrodes under oscillatory voltages. Micromachines 2019, 10:161. [CrossRef]

- Demekhin, E.A.; Ganchenko, G.S.; Kalaydin, E.N. Transition to electrokinetic instability near imperfect charge-selective membranes. Phys. Fluids 2018, 30:082006. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Cho, M.; Shin, J.; Kwak, R.; Kim, B. Electroconvective instability at the surface of one-dimensionally patterned ion exchange membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2024, 691. [CrossRef]

- Zabolotskii, V.I.; Loza, S.A.; Sharafan, M. V. Physicochemical properties of profiled heterogeneous ion-exchange membranes, Elektrokhimiya 2005, 41, 1185–1192. [CrossRef]

- Gnusin, N.P.; Pevnitskaya, M.V.; Varentsov, V.K.; Grebenyuk, V.D. USSR Inventor’s Certificate no. 216622, Byull. Izobret., 1971, no. 35.

- Larchet, C.; Zabolotsky, V.I.; Pismenskaya, N.; Nikonenko, V.V.; Tskhay, A.; Tastanov, K.; Pourcelly, G. Comparison of different ED stack conceptions when applied for drinking water production from brackish waters, Desalination 2008, 222, 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Vasil’eva, V.; Goleva, E.; Pismenskaya, N.; Kozmai, A.; Nikonenko, V. Effect of surface profiling of a cation-exchange membrane on the phenylalanine and NaCl separation performances in diffusion dialysis, Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 210, 48–59. [CrossRef]

- Loza, S.; Loza, N.; Kutenko, N.; Smyshlyaev, N. Profiled Ion-Exchange Membranes for Reverse and Conventional Electrodialysis. Membranes 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, S.; Loza, S.; Sharafan, M.; Zabolotskiy, V. Electrodialysis treatment of secondary steam condensate obtained during production of ammonium nitrate. Technical and economic analysis, Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 179–191. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Geise, G.M.; Luo, X.; Hou, H.; Zhang, F.; Feng, Y.; Hickner, M.A.; Logan, B.E. Patterned ion exchange membranes for improved power production in microbial reverse-electrodialysis cells, J. Power Sources. 2014, 271, 437–443. [CrossRef]

- Stockmeier, F.; Felder, D.; Eser, S. et al. Localized Electroconvection at Ion-Exchange Membranes with Heterogeneous Surface Charge. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chuah, C. Y.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, S. 3D Printed Functional Membranes for Water Purification. Chapter 11. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.; Urtenov, M. Analysis of the theoretical CVC of electromembrane systems. E3S Web of Conferences, 2020, 224, 02010. [CrossRef]

- Gudza, I.V.; Kovalenko, A.V.; Urtenov, M.Kh.; Pismenskiy, A.V. Artificial intelligence system for the analysis of theoretical and experimental current-voltage characteristics. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 2131(2), 022089. [CrossRef]

- Urtenov, M.K.; Kovalenko, A.V.; Sukhinov, A.I.; Chubyr, N.O.; Gudza, V.A. Model and numerical experiment for calculating the theoretical current-voltage characteristic in electro-membrane systems. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2019, 680(1), 012030. [CrossRef]

- Kirillova E.; Kovalenko A.; Urtenov M. Study of the Current–Voltage Characteristics of Membrane Systems Using Neural Networks. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.V.; Gudza, I.V.; Pismenskiy, A.V.; Chubyr, N.O.; Urtenov, M.Kh. Theoretical analysis of the current-voltage characteristic of the unsteady 1:1 transport of an electrolyte in membrane systems, taking into account electroconvection and the dissociation/recombination reaction of water. Modeling, Optimization and Information Technology. 2021;9(3). https://moitvivt.ru/ru/journal/pdf?id=1014. (In Russ) [CrossRef]

- Shkorkina, I.; Chubyr, N.; Gudza, V.; Urtenov M. Analysis of the theoretical current-voltage characteristic of non-stationary transport in the cross-section of the desalination channel. 2020, 224, 02015 . [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, A.; Urtenov, M.; Chekanov, V.; Kandaurova, N. Theoretical Analysis of the Influence of Spacers on Salt Ion Transport in Electromembrane Systems Considering the Main Coupled Effects. Membranes, 2024, 14(1), 20. [CrossRef]

- Vasil’eva, V.; Goleva, E.; Pismenskaya N. et al. Effect of surface profiling of a cation-exchange membrane on the phenylalanine and NaCl separation performances in diffusion dialysis. Separation and Purification Technology 2019. 210, 2018, 48-59. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).