1. Introduction

Several international instruments have recognized the human right to water [

1,

2,

3]. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights established that water has to be considered a social, cultural and economic good. On 28 July 2010, the United Nations General Assembly passed the resolution 64/292, called The Human Right to Water and Sanitation, recognizing that drinking water and sanitation are essential for the full development of life and all human rights [

4]. In 2015, that entity established the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, which sets as a goal to “Ensure access to water and sanitation for all” [

5]. At present, the World Economic Forum states that humanity is facing a global crisis regarding water supply [

6].

Water insecurity is defined as the inability to access and benefit from adequate, reliable and safe water for one’s well-being and healthy life [

7]. The interest on the impacts of unreliable water supplies has increased [

8], and some studies have already started to realize the multiple implications of the lack or poor condition of water on the health and well-being of populations and households [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Within this framework, the HWISE Scale arises, which offers the possibility to evaluate and quantify people’s experiences in their households regarding water access and use. It has been validated in several countries, both high- and low-income ones [

9] which makes it a comparative measurement for different communities, regions or countries, as well as for overtime comparisons. In April 2023, a Pan-American meeting about the measurement of water insecurity was convened with the participation of experts from more than 30 institutions in nine countries and from the United Nations too. In this meeting, it was recognized the importance of promoting the use of valid and reliable measurements that support sustainable progress towards the full realization of the human right to water [

16].

In Argentina, the official tools available for the measurement of this phenomenon focus solely on water access and availability in terms of infrastructure. With the aim of improving water security information, understood as the ability to access sufficient adequate quality water for human consumption, in 2023 the HWISE Scale was integrated into the Argentine Social Debt Survey (EDSA) of the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina (UCA). This study has as its general objective to determine the validity and reliability of the HWISE Scale as an instrument for evaluating the experiences of Argentine households regarding insecurity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Information

In the present work, the microdata of EDSA, a multipurpose survey which has periodically provided since 2004 a broad set of development indicators, were used. For this study, a multistage probability sample of 5,799 households was used, with a first stage of clustering and a second of stratification. This sample represents the universe integrated by private households living in Argentine urban centers with more than 80 thousand inhabitants. The estimated margin of error is +/- 1.3%, with an estimated population proportion of 50% and a confidence level of 95%. Figure 1 shows the operational definitions of the main variables analyzed in this study.

Table 1.

Operational definition of the analyzed variables.

Table 1.

Operational definition of the analyzed variables.

| Variable |

Operational definition |

Variable values |

| Poverty [17] |

Percentage of households whose income does not allow them to acquire the value of the Total Basic Basket (CBT), and/or does not allow them to acquire the value of the Basic Food Basket (CBA) |

0. Not poor

1. Poor not indigent

2. Homeless |

| Food Insecurity [17] |

Percentage of households that reported reducing food portions and/or experiencing hunger due to economic hardship during the past 12 months. |

Moderate Deficit: Households in which it is expressed to have reduced the portion of food in the last 12 months.

Severe Deficit: Households in which it is expressed that they have felt hungry in the last 12 months.

Safety: Households in which it is not reported that they have reduced the portion of food in the last 12 months. |

| Socioeconomic level in quartiles [18] |

Percentage of households that are located in four levels of belonging based on a factorial index that takes into account the educational capital of the head of household, access to durable household goods and the residential condition of the housing, this index being re-coded into socioeconomic strata according to quartiles of the distribution. |

1. Very low (1st quartile)

2. Low (2nd quartile)

3. Middle (3rd quartile)

4. Medium-high (top 25%) |

| Urban agglomerates [18] |

Percentage of households residing in four large regions of urban agglomerations taken in the sample according to their spatial distribution, geopolitical importance and degree of socioeconomic consolidation. |

1. Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

2. Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area

3. Other Metropolitan Areas

4. Urban rest of the interior |

| Neighborhood Type [17] |

Percentage of households residing in three different forms of urbanization with varying degrees of formality in terms of planning, regulation and public investment in urban assets and with a heterogeneous presence of different socioeconomic levels. |

1. Emergency Village/Settlement

2. Social housing / Monoblocs

3. With an urban layout |

| Deficit of connection to the sewer network [17] |

Percentage of households living in homes without connection to the sewer network. |

0. No deficit

1. Deficit |

| Perception of lack of water in the home [17] |

Percentage of households in which the respondent reports that the neighborhood has the problem of lack of water. |

0. No deficit

1. Deficit |

| Psychological distress [19] |

Percentage of households in which the respondent reports having symptoms of anxiety and depression integrated into a score that indicates moderate or high risk of psychological distress on the KPDS-10 scale (score ranging from 10 to 50 points, and the distribution is categorized into tertiles). |

1.High

2. Moderate

3. Low |

2.2. Evaluation of Water in Insecurity

The HWISE Scale was applied to a household member aged 18 years or older randomly selected. Language was adapted based on the scale incorporated in the 2021 National Survey on Health and Nutrition (ENSANUT) in Mexico [

20]. The questions included were the following:

In the last 4 weeks, how often have you or someone from your household…

How frequently did you or anyone in your household worry you would not have enough water for all of your household needs?

How frequently has your main water source been interrupted or limited (e.g. Water pressure, less water than expected, river dried up)?

How frequently have problems with water meant that clothes could not be washed?

How frequently have you or anyone in your household had to change schedules or plans due to problems with your water situation? (activities that may have been interrupted include caring for others, doing household chores, agricultural work, income-generating activities, sleeping, etc.)

How frequently have you or anyone in your household had to change what was being eaten because there were problems with water (e.g., for washing foods, cooking, etc.)?

How frequently have you or anyone in your household had to go without washing hands after dirty activities (e.g., defecating or changing diapers, cleaning animal dung) because of problems with water?

How frequently have you or anyone in your household had to go without washing their body because of problems with water (e.g., not enough water, dirty, unsafe)?

How frequently has there not been as much water to drink as you would like for you or anyone in your household?

How frequently did you or anyone in your household feel angry about your water situation?

How frequently have you or anyone in your household gone to sleep thirsty because there wasn’t any water to drink?

How frequently has there been no useable or drinkable water whatsoever in your household?

How frequently have problems with water caused you or anyone in your household to feel ashamed/excluded/stigmatized?

The response options for each of the items are presented on an ordinal scale, and out of them, a score is calculated by adding the responses of each item in terms of frequency, following the methodology of Young et al. (2019). Four categories were used: Never (0), Rarely (1-2 times), Sometimes (3-10 times) and Often (11 or more times), which were scored 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively. If the respondent of the household chooses the option “Do not know/No answer” in any of the questions, the household is excluded from the sample. The same criterion is followed in the case of missing values. As a result, 115 observations were excluded, which represent 2.6% of the original sample. In Figure 2 and 3, descriptive statistics measures of the excluded observations are shown. Although there are statistically significant differences between the household characteristics of the included and the excluded observations, they did not significantly affect the representativity of the results exposed in the following section.

Following the methodology, it is considered that households with a score equal to or greater than 12 experience water insecurity.

Table 2.

Water insecurity indicator according to associated characteristics.

Table 2.

Water insecurity indicator according to associated characteristics.

| |

% |

IC95% |

| OVERALL AVERAGE |

6,5% |

5,6% |

7,5% |

| SEX OF HEAD OF HOUSEHOLD |

|

|

|

| Female |

6,8% |

5,5% |

8,3% |

| Male |

6,3% |

5,2% |

7,6% |

| AGE OF THE HEAD OF HOUSEHOLD |

|

|

|

| 18 to 29 years old |

5,4% |

3,6% |

7,8% |

| 30-49 |

7,2% |

5,8% |

9,0% |

| More than 50 years |

6,1% |

4,9% |

7,5% |

| CONNECTION TO THE SEWER NETWORK |

|

|

|

| No access |

10,8% |

8,7% |

13,4% |

| With access |

4,9% |

4,1% |

5,9% |

| PRESENCE OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS IN THE HOME |

|

|

|

| With children |

8,6% |

7,2% |

10,3% |

| Without children |

4,3% |

3,4% |

5,4% |

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC LEVEL |

|

|

|

| Very low |

12,8% |

10,4% |

15,6% |

| Low |

7,0% |

5,4% |

9,1% |

| Middle |

3,4% |

2,4% |

4,8% |

| Medium High |

2,4% |

1,5% |

3,8% |

| POVERTY AND INDIGENCE BY INCOME |

|

|

|

| Indigent |

14,0% |

9,6% |

20,0% |

| Poor no indigent |

10,1% |

8,1% |

12,6% |

| No poor |

4,1% |

3,3% |

5,0% |

| URBAN REGIONS |

|

|

|

| Autonomous City of Buenos Aires |

1,7% |

0,6% |

4,3% |

| Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area |

8,0% |

6,4% |

9,9% |

| Other Metropolitan Areas |

7,1% |

6,0% |

8,4% |

| Urban rest of the interior |

6,0% |

4,7% |

7,7% |

| TYPE OF NEIGHBORHOOD |

|

|

|

| Emergency Village/Settlement |

12,6% |

7,9% |

19,3% |

| Social housing / Monoblocs |

23,2% |

14,0% |

36,0% |

| With an urban layout |

5,9% |

5,0% |

6,8% |

Table 3.

Water insecurity indicator according to food insecurity and psychological distress.

Table 3.

Water insecurity indicator according to food insecurity and psychological distress.

| |

% |

IC95% |

| OVERALL AVERAGE |

6,5% |

5,6% |

7,5% |

| FOOD INSECURITY |

|

|

|

| Severe |

23,1% |

17,8% |

29,3% |

| Moderate |

12,5% |

9,1% |

16,9% |

| Safety |

3,8% |

3,1% |

4,6% |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS |

|

|

|

| Hight |

10,5% |

8,5% |

12,9% |

| Moderate |

5,2% |

4,1% |

6,7% |

| Low |

4,3% |

3,1% |

5,8% |

2.3. Validity and Reliability Measurements

To evaluate the reliability of the HWISE and its robustness as an instrument in the case of Argentina, validity and reliability tests were conducted. The validity of the instrument was verified by demonstrating that the indicators of the water insecurity scale are valid measurements related to lack of in water access and use. For this, the relationships of the HWISE with other variables that have previously proven to be related to water insecurity were tested. The following variables were selected: connection to sewer networks, lack of water in the neighborhood, total and severe food insecurity in the household [

21], and the respondent's psychological distress.

2.4. Data Analysis

Logistic regression models were applied which regress these dichotomous variables on the individual indicators of the water module, the water insecurity indicator, and the HWISE. Furthermore, control variables related to the household socio-economic and demographic characteristics, such as the logarithm of per capita family income, the number of household members, the gender of the head of household, and the urban agglomeration where the household is at, were included [

22].

For the reliability analysis the Classical Test Theory (CTT) was used, that included Cronbach’s alpha, Revelle's beta, Guttman's lambda, and Omega [

23]. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to or greater than 0.7 was considered as acceptable [

24]. A threshold value of 0.5 was used for Beta, and a threshold of 0.7 for Guttman's lambdas and Omega.

Finally, a hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted as a variable clustering technique. The hierarchical cluster analysis is employed to examine how items relate to each other based on their proximity [

25].

3. Results

In the second semester of 2023, based on the application of the HWISE scale, it was estimated that 6.5% of the urban Argentine households suffered from water insecurity. A higher water insecurity prevalence was found in the least socioeconomically advantaged households. On this matter, it was observed that water insecurity affected 14% of people in extreme poverty, and in the lowest social stratum (25% lower), it affected 12.8%. Simultaneously, it affected the residents from Buenos Aires Conurbation (Conurbano Bonaerense) and other large metropolitan areas from the Argentine provinces more than the citizens from City of Buenos Aires (CABA) and other small metropolises from the provinces. It is worth acknowledging that it rose above average in informal housings (shanty towns and settlements) and in social housing neighborhoods and monoblocks (public housing projects). Moreover, a significant difference in households with children and adolescents was registered. This difference remained significant even after controlling it by urban agglomeration, social stratum, and type of neighborhood (Figure 2).

This study also explored the relationship between water insecurity and two health indicators: psychological distress and severe food insecurity (Figure 3). It was found that households where the respondent has a “high” psychological distress present 10.5% of water insecurity, and that in households with severe food insecurity, the percentage is 23.1%.

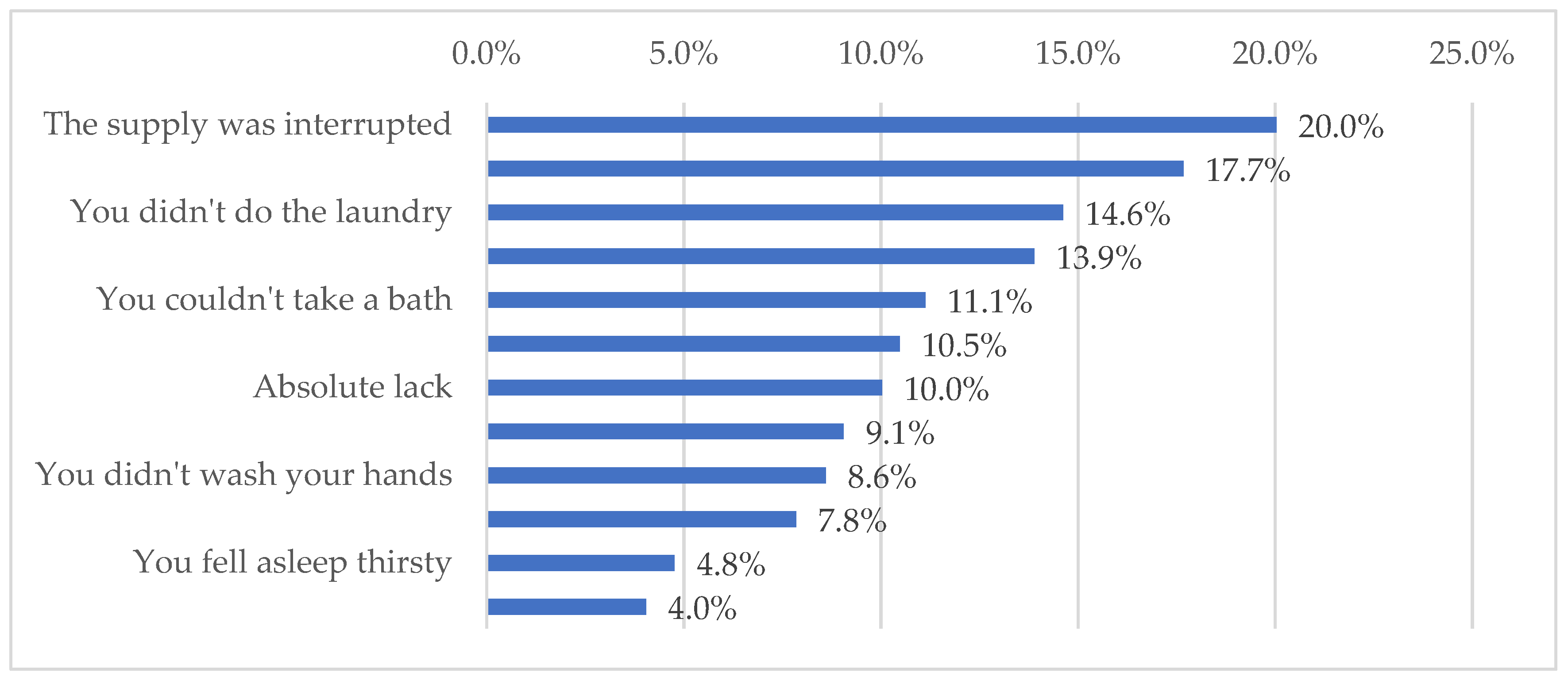

Regarding the 12 items of the HWISE Scale, it was observed that the item that referred to experiences of interruptions in water supply (20%) was the most common, followed by those related to feeling worry about not having enough water (17.7%) and problems with washing clothes (14.6%) (

Figure 4).

Figure 5 contains the results of the Maximum Likelihood estimation from the proposed logistic model. As it was expected, income poverty and extreme poverty maintained a positive and statistically significant relationship with water insecurity (p<0.001). In addition, having children and adolescents in the household increases the probability of experiencing water insecurity (p<0.10). Also, in low-socioeconomic neighborhoods the probability of having water insecurity increased (p<0.05). On the other hand, lack of connection to sewer networks had a significant and positive relationship with water insecurity (p<0.05). Finally, the validity was evaluated through logistic regressions, where lack of severe connection, lack of water in the neighborhood, total and severe water insecurity, and the respondent's psychological distress were statistically correlated with all the items included in the HWISE scale. Validity tests were successful, as all coefficients were significant in at least 10%. Moreover, reliability was verified through Cronbach's alpha, Revelle's beta, Guttman's lambda, and Omega statistics. The Alpha was satisfying and as can be observed in Figure 7, if any of the indicators are removed, the Alpha does not increase. In relation to Guttman's lambdas, and the Beta and Omega statistics, all of them exceed the suggested threshold of 0.8 (Figure 6).

Table 5.

Logistic regression model of household water insecurity.

Table 5.

Logistic regression model of household water insecurity.

| |

IH |

| Female Head of Household |

0.127 |

| |

(0.156) |

| Age of the head of household |

0.005 |

| |

(0.005) |

| It has no sewers |

0.360** |

| |

(0.181) |

| Presence of children (0 to 17 years) in the home |

0.324* |

| |

(0.180) |

| POVERTY SITUATION (BASE=Not Poor) |

|

| Poor no indigent |

0.621*** |

| |

(0.184) |

| Indigent |

0.914*** |

| |

(0.264) |

| URBAN AGLOM (BASE=CABA) |

|

| Greater Buenos Aires |

1.222** |

| |

(0.546) |

| Other large metropolitan areas |

1.188** |

| |

(0.531) |

| Rest of urban areas |

1.103** |

| |

(0.544) |

| TYPE OF NEIGHBORHOOD (BASE=With urban layout) |

|

| Social housing / Monoblocks |

1.515*** |

| |

(0.310) |

| Emergency village / Settlement |

0.669** |

| |

(0.291) |

| Constant |

-4.798*** |

| |

(0.613) |

| |

|

| Pseudo-R2 |

0.0714 |

| Remarks |

5,684 |

| Robust standard errors in parentheses |

|

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 |

|

Table 6.

Reliability coefficients.

Table 6.

Reliability coefficients.

| |

Cronbach's Alpha if the item is deleted |

| Total Alpha (without the deletion of any items) |

0,95 |

| The supply was interrupted |

0,94 |

| You worried |

0,94 |

| You didn't do the laundry |

0,94 |

| You got upset |

0,94 |

| You couldn't take a bath |

0,94 |

| You had to change plans |

0,94 |

| Absolute lack |

0,94 |

| You had to change the food |

0,94 |

| You didn't wash your hands |

0,94 |

| Not enough water to drink |

0,94 |

| You fell asleep thirsty |

0,95 |

| You felt ashamed |

0,95 |

| Beta Coefficient |

0,81 |

| Lambda 2 |

0,95 |

| Lambda 3 = Alpha |

0,95 |

| Lambda 4 |

0,97 |

| Omega_t |

0,96 |

4. Discussion

It has been shown that the HWISE is an important instrument to estimate and describe household water insecurity at a population level and has been tested in few Latin-American countries [

26], and to address the social gaps that condition and restrict children's opportunities for a better development [

27]. For instance, in the study by Shamah Levy et al. [

20] the application of the HWISE Scale was studied at a national level in Mexico, among other countries of the region [

21,

28]. The results of this study show that the HWISE scale can also be used as an estimate of water insecurity experiences in the case of Argentina, where it was previously qualitatively validated in terms of comprehension, acceptance, and relevance [

29], and in this article, quantitatively.

A significant association between higher scores of water insecurity measured with the HWISE and different variables of interest included in the analysis, such as monetary poverty, number of children in household, and socio-residential space, among others, was observed, matching with the findings of previous research. Thus, HWISE is deemed as a valid tool in terms of its measuring water insecurity and its association with other situations of deprivation and social vulnerability [

26,

30,

31,

32]. Similarly, water insecurity was evaluated in Bolivia and was related to infant feeding [

26]. In the study by Young et al. [

26] the association between water insecurity and food insecurity was studied using representative samples of 25 low-income and middle-income countries, including Brazil, Guatemala, and Honduras. The correlation between household water insecurity and the water insecurity has been previously reported [

8,

34,

35]. Also, we found a relationship between water insecurity and psychological distress. This has been previously reported, which allows us to build confidence regarding its consequences are not only physical [

37] but also psychological [

8,

11,

35,

36,

38]. This finding supports the theory about water insecurity is determined by multiple dimensions which may operate differently across populations in space and time [

39].

Firstly, the high response rate to the scale (97.4%) stands out, similar to that achieved in the Mexican case [

20], indicating that the scale's questions were understood by the urban Argentine population, confirming the results obtained in qualitative approaches [

29].

According to Cronbach's alpha coefficient, the scale demonstrates very good internal consistency. This result is consistent with the validation of the scale in Mexico [

20] and with the validation of a household water insecurity measure for low- and middle-income countries [

13].

The study presents a limitation: the information was gathered during the winter season in Argentina and the scale questions refer to a recall period of 4 weeks, which could have influenced the prevalence of water insecurity. As the country undergoes extremely different weather conditions depending on the season, and summer usually presents higher water access problems, it may be more adequate to evaluate household water insecurity using a recall period of more than 4 weeks. Given the climate difference between seasons, the measurement of water insecurity at household level can be affected by climate changes, as shown in Mexico [

20].

However, an important strength of our study is that includes a large sample of individuals, that allows comparisons between sociodemographic groups. In addition, other variables were measured that not online allowed to evaluate the criterion validity of the scale in Argentina, but it also provides new evidence to monitor and to evaluate water insecurity in the region and worldwide.

The access to safe water has been monitored for a long time using well-established metrics to evaluate water resources and their accessibility [

22]. Nevertheless, it is well understood that these old metrics are inaccurate and that they contribute to the underestimation of water insecurity [

34,

40].

The evidence presented contributes to the validity of measuring water insecurity using the HWISE scale. The case of Argentina also provides evidence within Latin America on the importance of the HWISE scale as a key instrument for estimating water insecurity, its causes, and consequences, considering social and geographical inequalities and its evolution over time.

The validation process of a scale is long and complex. Given the nature of the scale, it is essential to ensure its validity in different contexts, and in this regard, this article represents an applied contribution to the case of Argentina. Contexts are highly diverse, even within a single country, so each contribution that demonstrates the scale’s validity is a step toward its global use.

Additionally, the correlations of the scale with poverty, food insecurity, habitat deprivations, and even indicators of psychological distress confirm the relevance of studying deprivations in access to water as a vital resource (and right) for human development and well-being.

Water insecurity affects the overall health of the population and, therefore, has consequences for the fulfillment of basic rights to subsistence and life, as well as the potential for human and social development in the country.

5. Conclusions

Access to safe water has historically been monitored through established metrics designed to assess water resources and their availability. However, it is widely acknowledged that these traditional metrics are often inaccurate and may underestimate the extent of water insecurity. In this context, the validation of the Household Water Insecurity Experiences Scale (HWISE) in Argentina represents a significant advancement in measuring this phenomenon, as it enables a more precise assessment of the deprivations associated with water access and use in households.

The findings of this study confirm the reliability and validity of the HWISE scale in the Argentine context, demonstrating its capacity to reflect social and geographical inequalities in water access. Furthermore, its significant correlation with indicators of social deprivation, food insecurity, sanitary infrastructure, and psychological distress reinforces its utility as a comprehensive tool for understanding the multiple dimensions of water insecurity and its impact on population well-being.

From a methodological perspective, this study constitutes a rigorous validation exercise that not only establishes the scale’s reliability in Argentina but also reinforces its applicability in countries with similar characteristics. The validation of measurement instruments is a fundamental step in social research and in the generation of reliable scientific evidence, as it ensures that the indicators employed accurately reflect the phenomenon they are intended to measure. In this regard, the analysis of internal consistency, criterion validity evaluation, and comparison with other social vulnerability factors consolidate HWISE as a robust and replicable instrument for future research and applications in the region.

In particular, the validation of this scale in Argentina is of special relevance due to the country’s geographical and socioeconomic heterogeneity. The unequal distribution of water resources, deficient infrastructure in certain areas, and extreme climatic conditions result in substantial disparities in water access across regions and socioeconomic groups. The adoption of a locally validated instrument facilitates a precise identification of these disparities and enables the implementation of more effective and context-specific public policies.

From a public policy perspective, the findings of this study support the need for the Argentine government to incorporate the HWISE scale into its official household surveys as a fundamental input for diagnosing and managing water access policies. Having robust and comparable data will enhance the design and implementation of strategies aimed at reducing water insecurity and its effects on the population’s quality of life.

Finally, this study reaffirms that measuring water insecurity is not merely a technical or statistical issue but also a moral imperative and a global commitment. Ensuring equitable and safe access to water is a fundamental human right and a key requirement for sustainable development. In this regard, advancing the accurate measurement of water insecurity through tools such as the HWISE scale is an essential step toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and building more just and resilient societies

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ianina Tuñón, Matías Maljar, Nazarena Bauso, Olga García and Hugo Melgar Quiñonez; Formal analysis, Matías Maljar and Nazarena Bauso; Investigation, Nazarena Bauso, Olga García and Hugo Melgar Quiñonez; Methodology, Ianina Tuñón, Matías Maljar and Hugo Melgar Quiñonez; Supervision, Ianina Tuñón; Validation, Ianina Tuñón, Matías Maljar and Hugo Melgar Quiñonez; Writing – review & editing, Ianina Tuñón, Matías Maljar and Nazarena Bauso.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to observatorio_deudasocial@uca.edu.ar.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina and the Alimentaris Foundation for their support. Thanks to Aridana Lo Iacono for the professional translation of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas. Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos, Resolución 217, A (III). 1948. Disponible en línea: https://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2003/2336.pdf (consultado el 25/03/2025).

- Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas. Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño. 1989. Disponible en línea: https://www.un.org/es/events/childrenday/pdf/derechos.pdf (consultado el 25/03/2025).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Guías para la calidad del agua potable. Vol. 1: Recomendaciones, 3.ª ed.; 2011. Disponible en línea: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272403/9789243549958-spa.pdf?sequence=1 (consultado el 25/03/2025.

- Comité de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales. Observación general N° 15 (Art. 11 y 12): El derecho al agua. Pacto Internacional de Derechos Económicos, Sociales y Culturales. 2002. Disponible en línea: https://www.escr-net.org/es/recursos/observacion-general-no-15-derecho-al-agua-articulos-11-y-12-del-pacto-internacional (consultado el 25/03/2025).

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas (ONU). Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. 2004. Disponible en línea: https://www.un.org/es/impacto-acad%C3%A9mico/page/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible (consultado el día, mes, año).

- Foro Económico Mundial. Incremento de los riesgos naturales. En colaboración con PwC. Serie Nueva Economía Natural. 2020. Disponible en línea: https://www.weforum.org/reports/increasing-nature-related-risks (consultado el 25/03/2025).

- Young, S. L.; Boateng, G. O.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Miller, J. D.; Frongillo, E. A.; Neilands, T. B.; Collin, S. M.; Wutich, A.; Jepson, E.; Stoler, J. The Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) Scale: Development and validation of a household water insecurity measure for low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health: 2019, 4, e001750. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P. R.; Zmirou-Navier, D.; Hartemann, P. Estimating the impact on health of poor reliability of drinking water interventions in developing countries. Science of the Total Environment: 2009, 407, 2621–2624. [CrossRef]

- Bethancourt, H.; Frongillo, E.; Viviani, S.; Cafiero, C.; Young, S. Household water insecurity is positively associated with household food insecurity in low-and middle-income countries. Current Developments in Nutrition: 2022, 6, 549. [CrossRef]

- Jepson, W. E.; Stoler, J.; Baek, J.; Martínez, J. M.; Salas, F. J. U.; Carrillo, G. Cross-sectional study to measure household water insecurity and its health outcomes in urban Mexico. BMJ Open: 2021, 11, e040825. [CrossRef]

- Baisa, B.; Davis, L. W.; Salant, S. W.; Wilcox, W. The welfare costs of unreliable water service. Journal of Development Economics: 2010, 92, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Majuru, B.; Mokoena, M. M.; Jagals, P.; Hunter, P. R. Health impact of small-community water supply reliability. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health: 2011, 214, 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. L. The measurement of water access and use is key for more effective food and nutrition policy. Food Policy: 2021, 104, 102138. [CrossRef]

- Aihara, Y.; Shrestha, S.; Kazama, F.; Nishida, K. Validation of household water insecurity scale in urban Nepal. Water Policy: 2015, 17, 1019–1032. [CrossRef]

- Kumpel, E.; Nelson, K. L. Comparing microbial water quality in an intermittent and continuous piped water supply. Water Research: 2013, 47, 5176–5188.

- Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Teruel-Belismelis, G.; Young, S. L.; the Water Insecurity Experiences-Latin America & the Caribbean (WISE-LAC) Network. A declaration on the value of experiential measures of food and water insecurity to improve science and policies in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Journal for Equity in Health: 2023, 22, 184. [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglio, J. I.; Vera, J.; Salvia, A. (Coord.). Privaciones sociales y desigualdades estructurales. Condiciones materiales de los hogares en un escenario de estancamiento económico (2010-2022), 1.ª ed.; Educa: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023.

- Tuñón, I. Retorno a la senda de privaciones que signan a la infancia argentina. Las deudas sociales con la infancia se retrotraen a los niveles prepandemia, marcando lo estructural de las carencias y desigualdades sociales que condicionan su desarrollo. Documento Estadístico. Barómetro de la Deuda Social de la Infancia. Serie Agenda para la Equidad (2017-2025); Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023.

- Rodríguez Espínola, C. S. (coord.); Garofalo, C. S.; Paternó Manavella, M. A.; Bauso, N.; Lafferriere, F. Desigualdades y retrocesos en el desarrollo humano y social 2010-2022. El deterioro del bienestar de los ciudadanos en la pospandemia por COVID-19, 1.ª ed.; Educa: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023.

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Mundo-Rosas, V.; Muñoz-Espinosa, A.; Gómez-Humarán, I. M.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Melgar-Quiñones, H.; Young, S. L. Viabilidad de una escala de experiencias de inseguridad del agua en hogares mexicanos. Salud Pública de México: 2023, 65, 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Stoler, J.; Miller, J. D.; Brewis, A.; Freeman, M. C.; Harris, L. M.; Jepson, W.; Pearson, A. L.; Rosinger, A.; Shah, S.; Staddon, C.; Workman, C.; Wutich, A.; Young, S. Household water insecurity will complicate the ongoing COVID-19 response: Evidence from 27 sites in 23 low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health: 2021, 234, 113715. [CrossRef]

- Jepson, W. E.; Wutich, A.; Collins, S. M.; Boateng, G. O.; Young, S. L. Progress in household water insecurity metrics: a cross-disciplinary approach. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water: 2017, 4. [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, I.; Lamarmora, G.; Sánchez, M. E. Pobreza multidimensional infantil en España y Argentina. Un ejercicio de construcción, compatibilización y análisis de robustez. EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales: 2022, 55, 57–96. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, L. Psychometric theory, 3.ª ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher, INC: New York, USA, 1994.

- Bridges Jr, C. C. Hierarchical cluster analysis. Psychological Reports: 1966, 18, 851–854.

- Young, S. L.; Bethancourt, H. J.; Ritter, Z. R.; Frongillo, E. A. Estimating national, demographic, and socioeconomic disparities in water insecurity experiences in low-income and middle-income countries in 2020–21: A cross-sectional, observational study using nationally representative survey data. The Lancet Planetary Health: 2022, 6, e880–e891. [CrossRef]

- Korc, M.; Hauchman, F. Advancing environmental public health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública: 2021, 45. [CrossRef]

- Rosinger, A. Y.; Bethancourt, H. J.; Young, S. L.; Schultz, A. F. The embodiment of water insecurity: Injuries and chronic stress in lowland Bolivia. Social Science & Medicine: 2021, 291, 114490. [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, I.; Bauso, N.; Maljar, M.; García, O.; Melgar Quiñonez, H. Validación cualitativa de la Escala de Inseguridad Hídrica (HWISE): Caso Gran Buenos Aires, Argentina. Agua y Territorio, 2025, frase que indica la etapa de publicación (en prensa).

- Stoler, J.; Pearson, A. L.; Staddon, C.; Wutich, A.; Mack, E.; Brewis, A.; Rosinger, A. Cash water expenditures are associated with household water insecurity, food insecurity, and perceived stress in study sites across 20 low-and middle-income countries. Science of the Total Environment: 2020, 716, 135881. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G. O.; Neilands, T. B.; Frongillo, E. A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R.; Young, S. L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health: 2018, 6, 149. [CrossRef]

- Frongillo, E. A.; Nanama, S.; Wolfe, W. S. Technical guide to developing a direct, experience-based measurement tool for household food insecurity. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance, Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, 2004; págs. 1–51. Disponible en línea: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/Experience-Expression-Food-Insecurity-Apr2004.pdf (consultado el 25/03/2025).

- Schuster, R. C.; Butler, M. S.; Wutich, A.; Miller, J. D.; Young, S. L.; Household Water Insecurity Experiences-Research Coordination Network (HWISE-RCN); Workman, C. “If there is no water, we cannot feed our children”: The far-reaching consequences of water insecurity on infant feeding practices and infant health across 16 low-and middle-income countries. American Journal of Human Biology: 2020, 32, e23357. [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. The millennium development goals and urban poverty reduction: Great expectations and nonsense statistics. Environment and Urbanization: 2003, 15, 179–190.

- Workman, C. L.; Brewis, A.; Wutich, A.; Young, S.; Stoler, J.; Kearns, J. Understanding biopsychosocial health outcomes of syndemic water and food insecurity: Applications for global health. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene: 2021, 104, 8–11.

- Workman, C. L.; Ureksoy, H. Water insecurity in a syndemic context: Understanding the psycho-emotional stress of water insecurity in Lesotho, Africa. Social Science & Medicine: 2017, 179, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Brewis, A.; Choudhary, N.; Wutich, A. Household water insecurity may influence common mental disorders directly and indirectly through multiple pathways: Evidence from Haiti. Social Science & Medicine: 2019, 238, 112520. [CrossRef]

- Bose, I.; Bethancourt, H. J.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Mundo-Rosas, V.; Muñoz-Espinosa, A.; Ginsberg, T.; Kadiyala, S.; Frongillo, E. A.; Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Young, S. L. Mental health, water, and food: Relationships between water and food insecurity and probable depression amongst adults in Mexico. Journal of Affective Disorders: 2025, 370, 348–355. [CrossRef]

- Young, S. L.; Frongillo, E. A.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Ringler, C.; Rosinger, A. Y. Perspective: The importance of water security for ensuring food security, good nutrition, and well-being. Advances in Nutrition: 2021, 12, 1058–1073. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L.; Movik, S. Liquid dynamics: Challenges for sustainability in the water domain. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water: 2014, 1, 369–384. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).