1. Introduction

Dirac, in his seminal paper of 1931, justified the existence of a magnetic monopole from the quantization of angular moment as a product between electric and magnetic charges [

2]. From this quantization the basic pair of elementary electric and magnetic charges arises: the elementary electric charge is the electron, while the elementary magnetic particle is the “classical” magnetic monopole. Within the framework of the grand unified theories (GUT), “gauge” magnetic monopoles are singularities that appear at the transitions from a unified group into subgroups [

1,

3,

4]. The detection of classical or gauge magnetic monopoles still remains one of the biggest challenges at the frontier of scientific research [

5], although some new hopes have recently emerged [

6]. These same new theories have revealed that the electric charge can be fractional such as that of quarks [

1]. For this reason, we can imagine an analogous scenario for the magnetic charge. We propose here a hypothetical fractional magnetic source that we call a metapole, which can be defined in an analogous way to the other multipoles, such as monopoles, dipoles, quadruples, etcetera. We show some simple properties of the metapole, and speculate that it could be at the origin of all magnetic sources. For example, we show that a pair of metapoles produces, at a distance much greater than their separation and in most of their surroundings, the same effects as a monopole. Some implications of its possible existence are investigated. We expect that this magnetic particle was created at the big bang and it is still being created in the Universe as a consequence of a basic principle of fundamental physics related to gravitational bodies [

7] and its detection will probably be as challenging as that of monopoles. However, we believe that its initial presence may have generated a sort of “cosmic magnetic background relic” that, together with its continuous generation, is still contributing to the creation of a seed magnetic field at planetary and galactic scales.

2. The Metapole

Let us define the metapole in terms of its magnetic field potential in analogy with other more conventional multipoles [

8]. In general, we can define a magnetic multipole j-pole as a magnetic source with a magnetic field potential outside the matter:

with j=2

n ; k

n is an appropriate constant and f

n( ) is a function depending only on the colatitude ( ) and longitude ( ) but not on the radial distance r of the point of measurement from the location of the multipole, which is taken as the origin of the reference system. Their dimensions change accordingly with n. The latter parameter, in general, n≥0, is the corresponding harmonic degree when we expand the magnetic field potential in spherical harmonics. In this way, a monopole is defined with j=1 and n=0, a dipole with j=2 and n=1, a quadruple with j=4 and n=2, and so on. Consequently, we can define a magnetic field

Bn = -grad V

n:

It is easy to see that the total intensity of this vector will be

i.e., the intensity decays with the radial distance as an inverse (n+2)-power law; f

n* is a known function of n, f

n and its partial derivatives. Actually, for n=0 (monopole) there is no dependence on and while for n=1 (dipole), after an appropriate choice of the reference system (z-axis coinciding with the dipole axis), there is no dependence on

We can now extend the above definitions also to negative values of n, i.e. n=-2, -3, -4, …: in these cases, the corresponding sources are dipoles, quadrupoles, octupoles, …, respectively, placed at r=∞. As defined above, there is yet another kind of “j-pole” that has been never taken into account, one with j=1/2 and n=-1:

so that the magnetic potential will not have any radial dependence. The corresponding total intensity will be in the general form:

Because of the value of j, in analogy with the names of the other multipoles, we will call this magnetic source a

metapole, where the prefix meta has the double meaning of “beyond” (from meta in ancient Greek) and “half” (from metà in modern Italian). Because the field is derived from a scalar potential, it is always rot

B-1=0, while the null divergence is satisfied for f

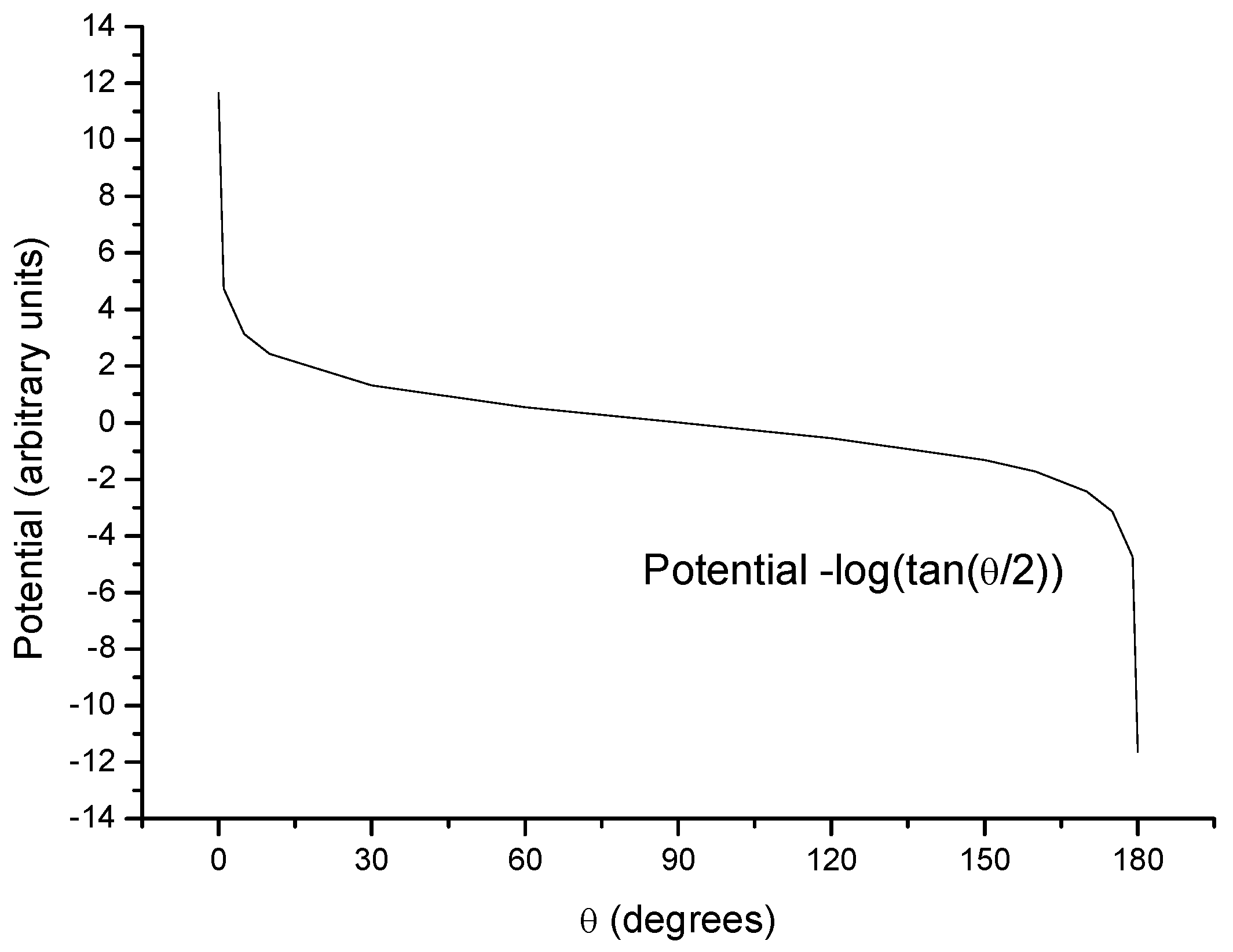

-1=log(tan( 2)), where log is the natural logarithm. Hence the corresponding equation (3) becomes:

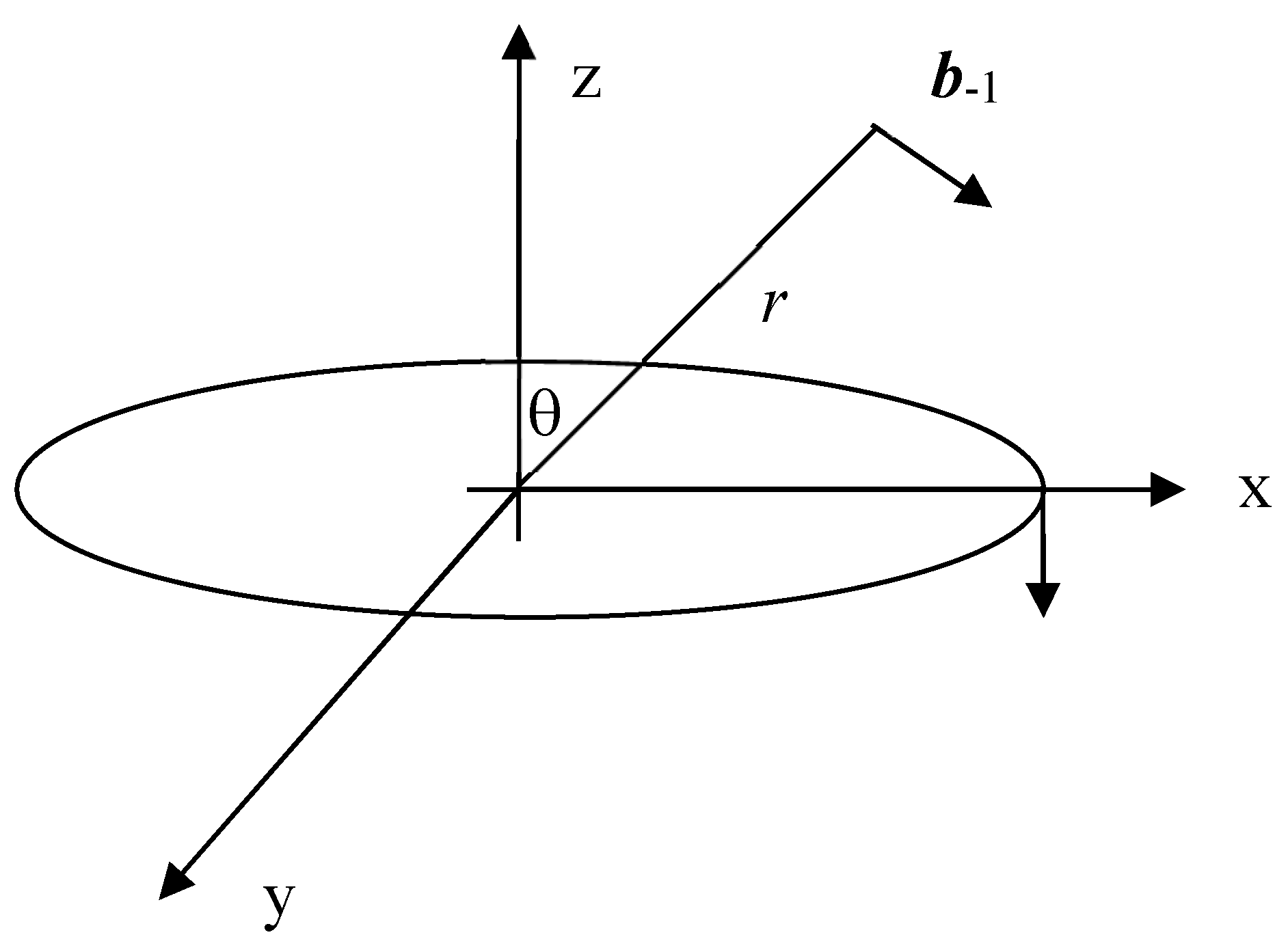

The corresponding field is a vector b-1 =(0, k-1/(rsin , 0), which has only the -component, in analogy with the dipole.

This hypothetical magnetic charge has some important properties.

Figure 1 shows the magnetic field of this kind of metapole, while

Figure 2 and

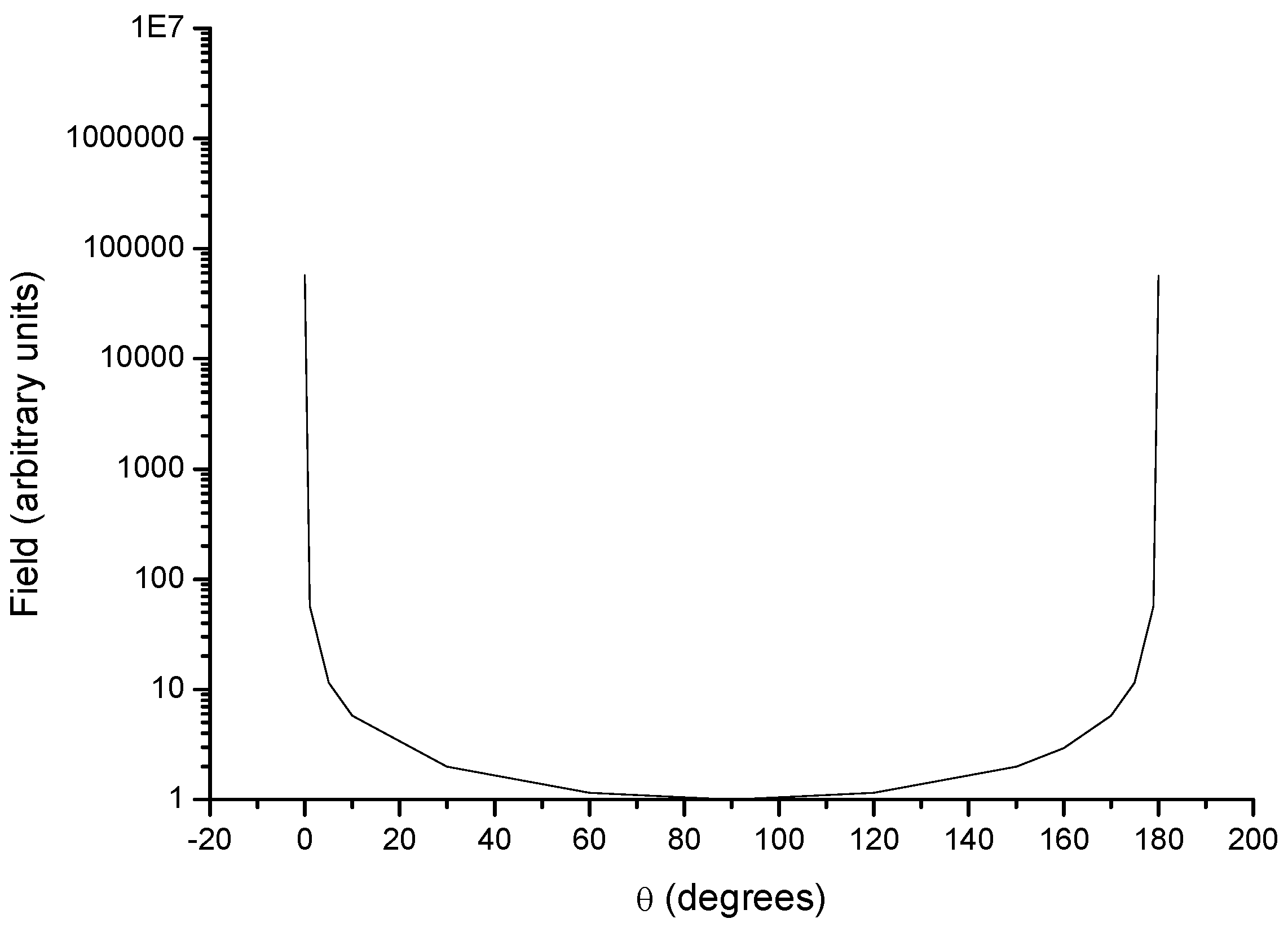

Figure 3 describe the behaviour of its magnetic potential and field, respectively, with colatitude. Because the corresponding magnetic field is always positive and colatitudinal, the field vector is always directed toward increasing colatitudes and the magnetic field lines of the metapole are along spherical surfaces. This means that the metapole has a preferential axis and direction: rotating the metapole by 180° changes the signs of both the potential and field. Both the field and potential are singular along all the entire z-axis, where they go to plus or minus infinity. However this divergence could be prevented (see

Appendix), but for convenience we continue with this simpler expressions for potential and magnetic field. We can call the metapole defined above, i.e. with V=+∞ in =0, “up”, while the other kind of metapole (defined by the same potential but without the minus sign, i.e. with V=-∞ in =0), can be called “down” (this nomenclature somewhat follows that used for the first two kinds of quarks [

1]).

Figure 4 compares the equipotential surfaces and magnetic field lines of the metapole and the monopole. It is noteworthy that there is a striking duality between the two magnetic charges, i.e. the similarity between the equipotential surfaces of the metapole and the magnetic field lines of the latter, and vice versa.

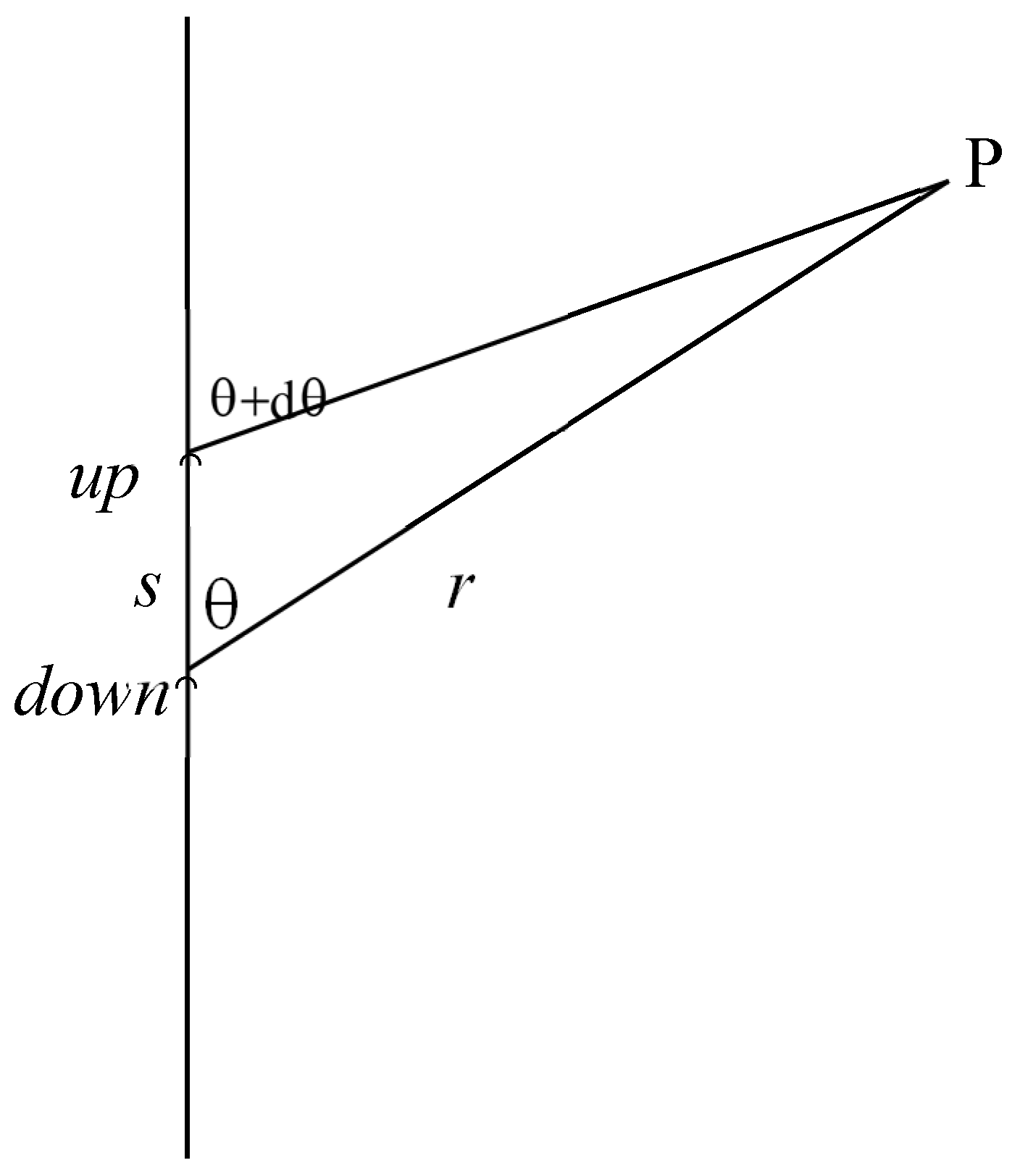

A couple of metapoles with opposite orientations, up (potential V+dV) and down (potential –V), placed at small distance s from each other, with the down metapole placed at the origin, provides a magnetic potential V

t at radial distance r (r>>s) (

Figure 4):

where dV is the differential of the potential. Since rdq≈s sinq, the resulting potential is:

with a field

whose total intensity is

Equations (6-6c) resemble the general definitions (1-2a) for a positive magnetic monopole, whose field is directed toward the origin and decays as 1/r2. An exception to the radial field occurs along the z-axis, where the field is only colatitudinal but still follows a 1/r2 dependence. If we have a combination of down-up metapoles, we will closely resemble a negative magnetic monopole. A complete resemblance can be achieved when a series of down-up pairs are rotated differently with respect to the original orientation. For instance, a couple of metapoles placed in the equatorial plane (q= /2) would resolve the issue along the z-axis.

If we relax the null divergence condition, for example, even a simpler potential with f-1= provides another metapole-like field: the corresponding field b-1 =(0, k-1/r, 0) satisfies the general condition established by equation (4). By the way, this potential, with an appropriate factor, is a good approximation of equation (5) for colatitudes in the interval 150°> >30°. A couple of this kind of metapoles can also generate, at distances r>>s, a monopole-like potential and field (although non completely radial): and , respectively. The total intensity is and decays as a monopole. It is interesting to notice that there is a preferential plane = /2, where the field divergence is also null. This is obvious because, in this plane, this simpler potential is the same as the log-tan potential of equation (5).

This raises the question: Could magnetic monopoles, if they exist, actually be bound metapole pairs? This hypothesis could have implications for high-energy physics and early-universe magnetic field generation.

More in general, we can think of metapoles as a sort of elementary magnetic charges, whose different combinations can produce, in some localized areas of space, the same effects as monopoles and multipoles of successive orders. If metapoles are fundamental entities, they might form the building blocks of larger magnetic structures, much like quarks combine to form hadrons. This would provide an alternative to monopole-based explanations of cosmic magnetism.

3. Discussion and conclusions

We do not explore here the consequences of the introduction of metapoles on the work of Dirac [

2] or within the framework of GUT (1,3,4); we prefer to make other speculations bases on different considerations. As all heavier chemical elements have been created from the lightest ones, such as Hydrogen, Helium, and so on [

9,

10], we can expect that not only monopoles, but also metapoles were the first kinds of magnetic sources generated at the beginning of the Universe when the physical conditions were very extreme [

11]. Since magnetic monopole and successive j-pole fields decrease more quickly with distance than the magnetic metapole field, we expect that footprint of metapoles could still exist in the deep space. On the other hand, from the behaviour of pulsar and galactic magnetic fields with distance that generally follow a 1/r law [

12], such as that of equation (4), i.e. that is typical of the metapole, we could also expect that the magnetic metapole field can be generated from some principle of fundamental physics related to massive gravitational bodies that is under investigation [

7]. The continuous generation of this kind of field would allow the violation of the so-called Parker’s limit [

13]. which otherwise would impose a maximum number of monopoles in the Galaxy, due to the presence of a substantial magnetic field. This possibility would shed new light on the basic properties of the gravitational field and on the possible quantization of its hypothetical elementary particle, the graviton, within the framework of the search for a supposed lost symmetry [

14]. Moreover, the existence of metapoles and their possible creation under particular conditions would provide more support for the ubiquity of planetary magnetic fields [

15], possibly contributing to the seed magnetic fields that are so important for the activation of planetary dynamos.

Finally, we could ask why, so far, we have never found this kind of particle, just as it was for the magnetic monopole. We think this is due to the huge length scale over which the present metapole field generation acts. In a work in preparation [

7], it is shown that a metapole field can be generated by a very massive body over less massive bodies gravitating around it with asynchronous rotation: the general effect is visible when extended to very large spatial scales (some effects can be seen on the Solar System scale, greater effects can be seen on galactic scales), and this could explain the difficulty in detecting it over smaller scales (comparable to or less than Earth’s size) where dipole and higher order poles provide more significant contributions.

Since metapoles exhibit a unique field behavior ( 1/r decay rather than 1/r2), potential observational signatures could include:

Astrophysical magnetic fields: If galactic or pulsar magnetic fields exhibit a persistent behavior, it could hint at metapole contributions.

Lab-based searches: Investigating whether fractional magnetic charges can manifest in high-energy experiments, similar to the fractional electric charges of quarks.

Numerical simulations: Testing whether metapole interactions can self-consistently reproduce observed planetary and galactic magnetic structures.

Although apparently metapoles are only theoretical objects, we can even expect some practical applications in equivalent source modelling of many real sources in nature, in analogy with the equivalent source methods [

16] where a set of dipoles or monopoles placed at some distance from some real distributions of sources can represent their effects, e.g. inside the Earth, in the outer core [

17,

18] or in the lithosphere [

19].

The introduction of the metapole offers a novel perspective on magnetic charge and field structures. While mathematical consistency is confirmed, further refinements are needed to establish its physical viability. Future work should explore its implications in astrophysics, quantum field theory, and experimental detection methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation A.D.S. and R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.S.; writing—review and editing, A.D.S. and R.D.; visualization, A.D.S. Both authors have read and agreed to a version of the manuscript very close to that published.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dedication

This work began in 2007 when, out of the blue, Roberto Dini wrote to me (A.D.S.), sharing his ingenious ideas about a possible mechanism for generating the seed of all galactic and planetary magnetic fields. Intrigued by his insight, we embarked on an intensive exchange of ideas via email, despite never meeting in person. However, as both of us were deeply engaged in other professional and personal commitments, our collaboration was set aside and remained unfinished for years. Only recently, when I found myself with more time, I felt compelled to revisit and complete our work. I reached out to Roberto via email, only to receive a notice that the recipient was unknown. A quick search online led me to the heartbreaking discovery that Roberto had passed away in 2020, suffering a fatal heart attack during a video meeting with his colleagues. Though I never had the chance to meet him in person, I came to appreciate, through our many exchanges, his profound understanding of physics and his expertise across multiple scientific disciplines. More than that, I admired his open-mindedness, integrity, and intellectual honesty. This work is, in part, a tribute to his brilliance and passion for discovery.

Appendix

To prevents divergence along the z-axis, we can add a small regularization parameter ε within the log tan function. This leads to a magnetic potential:

Computing the negative gradient of the potential, in spherical coordinates, we obtain the corresponding magnetic field B:

This confirms that the metapole has a purely colatitudinal field component, distinct from classical multipoles, which have radial dependence.

This modification allows to achieve two advantages, i.e. the regularization of the potential and the fact that metapoles have a finite-size: i) the addition of ε in the logarithmic function ensures that V remains finite at θ=0, π; ii) instead of being modeled as point sources, metapoles can be treated as extended charge distributions along a small finite segment on the -axis. This could be represented by an integration over a Gaussian-like distribution of sources.

These adjustments suggest that metapoles may not be localized point sources but rather extended field structures, possibly resembling filamentary magnetic sources. However, as said in the main text, for convenience we prefer to use the simpler expressions for potential and field.

References

- Ross G.G., Grand Unified theories, (Perseus, Reading, Massachusets, 2003).

- Dirac P.A.M., Quantized singularities in the electromagnetic field, Proc. R. Soc., A133, 60 (1931).

- Giacomelli G., Magnetic Monopoles, Il nuovo Cimento, 7, N.12, 1-111 (1984).

- Salam A., Gauge Unification of Fundamental Forces, Science, 210, N.4471, 723-732 (1980).

- Carrigan R.A. Jr., Trower W.P., Magnetic monopoles, Nature, 305, 673-678 (1983).

- Fang Z., Nagaosa N., Takahashi K.S:, Asamitsu A., Mathieu R:, Ogasawara T., Yamada AH., Kawasaki M., Tokura Y., Terakura K., The anomalous Hall effect and Magnetic monopoles in momentum space, Science, 302, 92-95 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Dini, R. et al., An Energy Conservation Invariant Law, in preparation.

- Jackson J.D., Classical Electrodynamics (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1962).

- Alpher R. A., Bethe, H. A. and G. Gamow, The Origin of Chemical Elements, Physical Review, 73, 803-804 (1948). [CrossRef]

- Gamow, G., The evolution of Universe, Nature, 162, 680-682 (1948).

- Harrison E., Cosmology, the science of the Universe, (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2nd Ed., 2000).

- Beck R., Magnetic fields in the Milky Way and other spiral galaxies, in How does the Galaxy Work?, 277-286, Alfaro E., Perez E. and Franco J. (eds) (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 2004).

- Parker E.N., Conversations on electric and magnetic fields in the cosmos, (Princeton University Press, 2007).

- Wilczek F., In search of symmetry lost, Nature, 433, 239-247 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.J. Planetary magnetic fields. Rep. Prog. Phys. 46, 555-620 (1983); Earth Planet. Science Lett., 208, 1-11 (2003).

- Mayhew, M.A., An equivalent layer magnetization model for the United States derived from satellite altitude magnetic anomalies, J. Geophys, Res., 87, 4837-4845 (1982). [CrossRef]

- Hodder B., Monopoly, Geoph. Journ. Inter., 70, 1:217-228 (1982).

- Rivera P. , Pavón-Carrasco F. J., De Santis A., Campuzano S. A. , Cianchini G. , Osete M. L. Magnetic core field anomalies in the non-axial field during the last 3300 years: approach with an equivalent monopole source, Frontiers in Earth Science, 13 (2025). [CrossRef]

- O’Brien M.S., Parker R.L., Regularized field modelling using monopoles, Geoph. Journ. Inter.,.118, 3, 566-578 (1994). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).