1. Introduction

The term Sphingolipids (SLs) is derived from the Greek word “sphinx” owing to their enigmatic biochemical properties [

1,

2]. SLs constitute a functional lipid raft in a eukaryotic cell. A lipid raft constitutes organized SLs and transmembrane functional and structural proteins [

3,

4]. They play a significant role in membrane biochemistry and regulating cell function [

5]

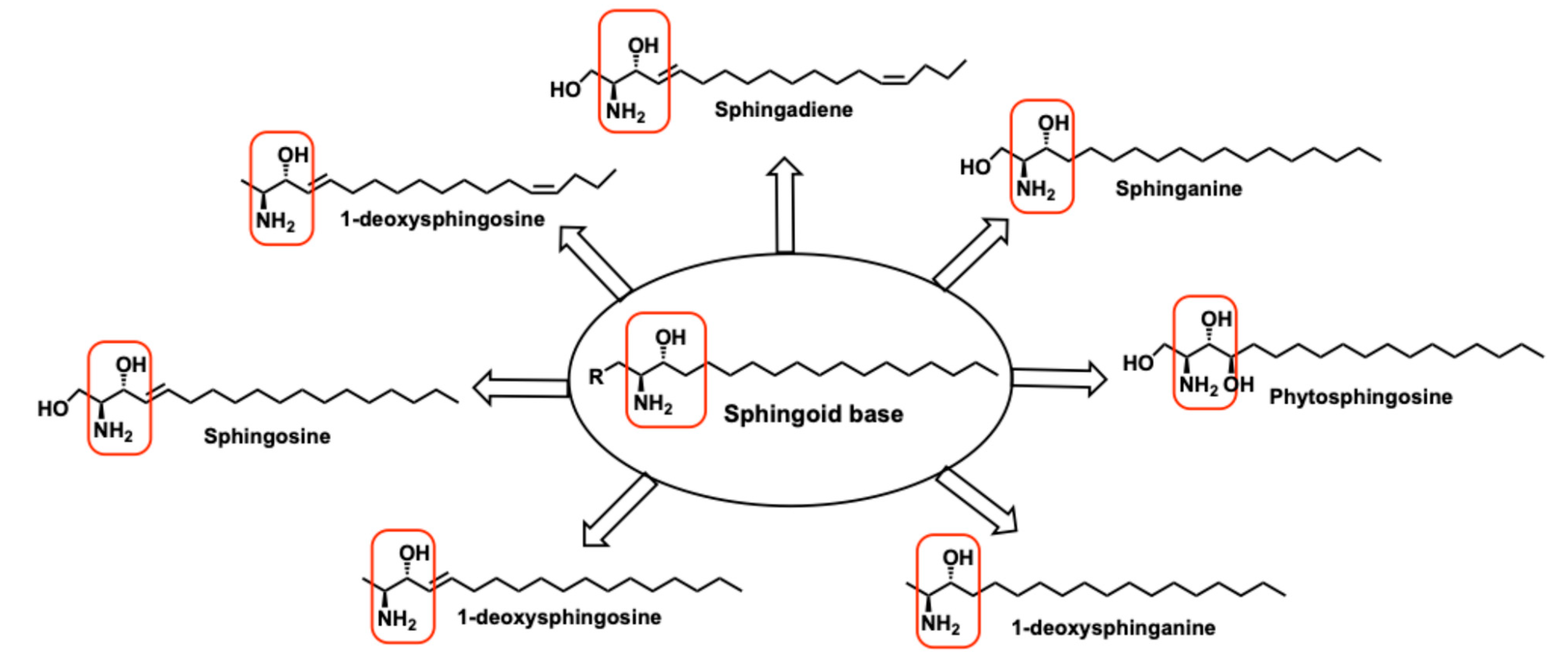

. The chemical structure of sphingolipids constitutes a sphingoid base, such as Sphingosine (Sph), as the building block. Sph is a substrate for the biosynthesis of diverse complex sphingolipids (

Figure 1). These complex sphingolipids are involved in highly regulated metabolic processes. Despite SL’s structural and functional diversity, they are created and recycled by common catabolic biosynthetic pathways [

3,

4,

5]

. These biosynthetic pathways occur in different organelles, forming an array of interconnected networks which differ from a single common entry point and converging into a single breakdown pathway [

6]. This network of SLs, with proximity to various receptors, enzymes, and lipids, participate in critical functions of the cells like growth regulation, apoptosis, senescence, cell migration, adhesion, and inflammatory responses. Most of these pharmacological functions have implications in diseased states like cancer, cardiovascular, metabolic disorders, and immune functions [

6]

. Biochemically, sphingolipids’ spatial distribution in distinct compartments is evolved to serve specialized functions in eukaryotic cells.

The physicochemical properties of SLs constitute a sphingoid base with an amino-alcohol functionality with an inherent

L-stereochemistry [

4,

7]. The biosynthesis starts from the cellular chiral pool,

L-Ser, resulting in a family of Oxysphingolipids. while

L-Ala results in a family of deoxysphingolipids [

8] (

Figure 1). The SL biosynthesized from

L-Ala lacks primary alcohol functionality, which is an essential nucleophile for derivatization towards complex functional SLs. For example, Ceramide (Cer) is biosynthesized from

L-Ser; the primary alcohol of Cer is derivatized to afford a very important sphingolipid, Sphingomyelin (SM). SM is a basic unit of myelin sheath, among several others. However, a deoxy-ceramide cannot be derivatized as SM due to a lack of alcohol functionality. Deoxysphingolipids also differ in their physico-chemical properties due to the absence of the primary alcohol [

9].

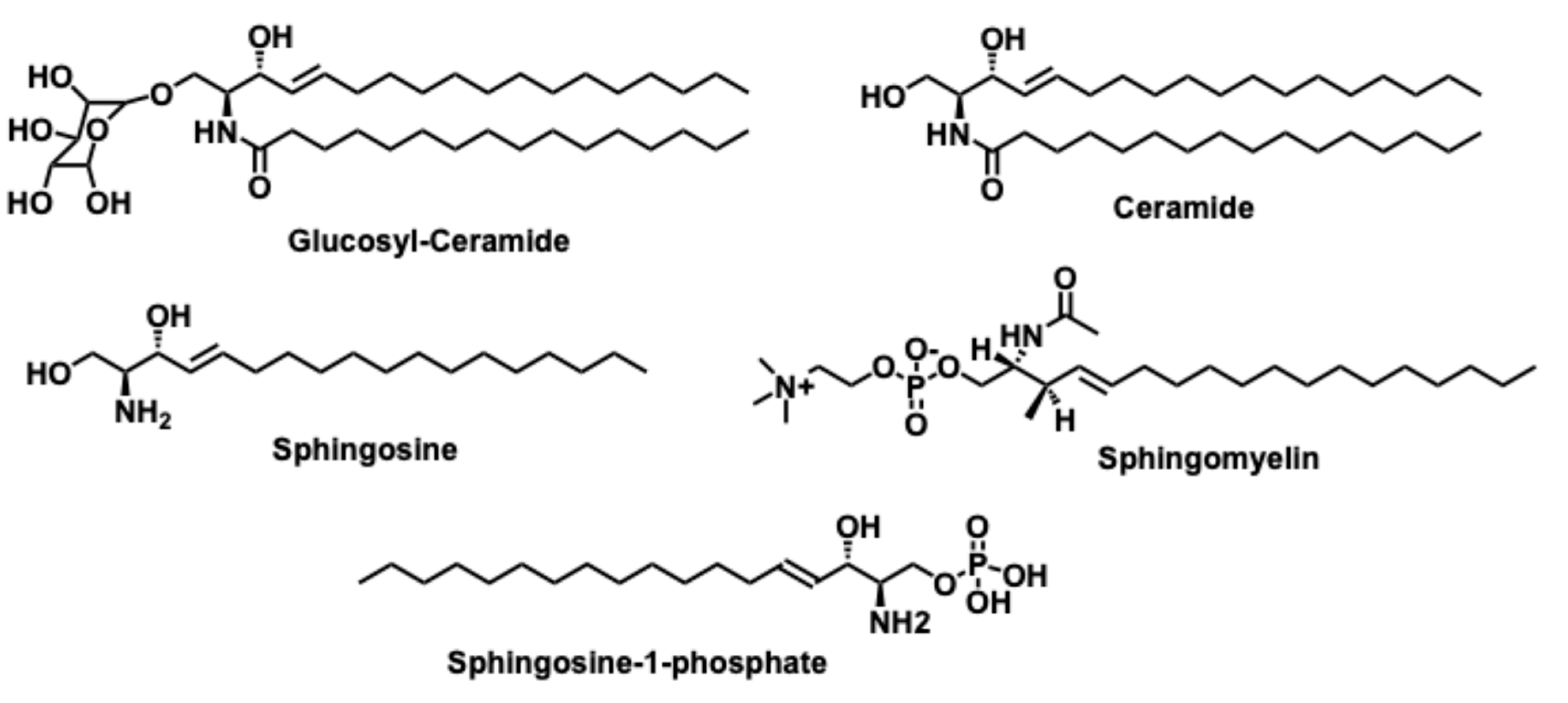

The major derivatized bioactive sphingolipids constitute ceramide (Cer), Glucosylceramide (GCer), ceramide-1-phosphate (C1P), Sphinganine (Sph), and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) structures depicted in

Figure 5. SLs possess the characteristic ‘sphingoid-base,’ an anti-amino alcohol with varying aliphatic chains [

10] (

Figure 1). The anti-amino alcohol system imparts a polar nature, with both amine and alcohol functionalities having a lone pair of electrons. The ‘-OH’ is the H-bond donor, whereas the -NH

2 can participate both as an H-bond donor and acceptor and the basic nature of -NH

2 makes this core the “Sphingoid base.” Amine as a base can participate as a biological nucleophile. The anti-amino-alcohol system is a stable conformation and enantiopure, which allows for derivatization towards complex functional sphingolipids. Synthetically, it is very challenging to achieve a 100% diastereoselective anti-amino alcohol but an elegant catalysis by 3-keto-sphinganine reductase affords this selectivity during biosynthesis of Cer (

Figure 5). A gauche or eclipsed confirmations along the σ-bond would have experienced internal H-bond and interfered with further derivatization towards functional SLs. So, anti- amino alcohol is favored.

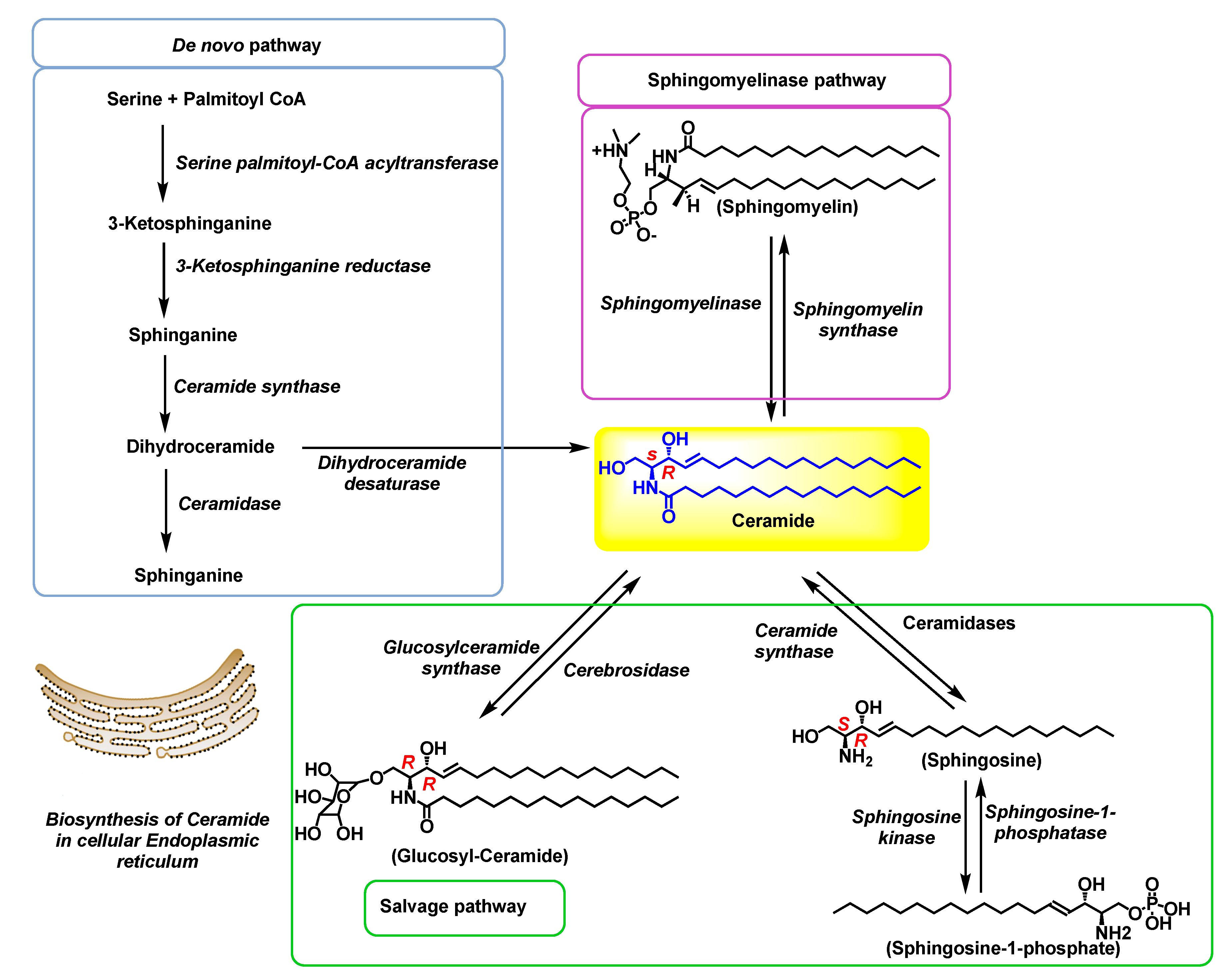

2. Ceramide Biosynthesis and Metabolism

Ceramide (Cer) is a biochiral SL, also known as the central signaling molecule of the SLs pathway because of its critical role in regulating various cellular metabolic processes, including but not confined to apoptosis, senescence, cell cycle arrest, cell aging, and multiple responses to stress signals within the body [

11]. Various external stimuli can activate pathways generating Cer, for example, TNF-α-a pro-inflammatory cytokine, apoptosis, heat stress, oxidative stress, radiation, and chemotherapeutic agents [3,12-17].

Cer biosynthesis involves

N-acylation of the sphingoid bases with varying fatty acids and/ or a variety of head group substitutions to afford complex SLs. The aliphatic tail can differ in structure depending on the number of carbons in the chain, the substitution of unsaturation, the position of these double bonds, and even the spatial arrangement. SLs with this structural complexity in a lipid raft interact with cholesterol and maintain membrane stability [

18,

19] . Cer biosynthesis involves complex pathways catalyzed by specific enzymes. There are three main pathways involved in ceramide biosynthesis:

the de novo biosynthesis starting from L-Ser, the Sphingomyelinase (SMase) pathway, involving the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin, and finally, hydrolysis of complex sphingolipids called salvage pathway. These three pathways contribute to the chiral pool ceramide cellular levels.

The significance of spatial distributions of enzymes in different cellular compartments and their effects on cell signaling and SLs flux was early on identified by Hannun

et al [

20]. For example, the rate-limiting enzyme of the

de novo pathway, serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT) is located in the endoplasmic reticulum [

21]. Dihydroceramide (DhCer), a substrate for the Cer biosynthesis in the

de novo pathway, is biosynthesized from the endoplasmic reticulum-derived dihydrosphingosine. Meanwhile, Sph, for Cer regeneration via salvage pathway, is generated from the breakdown of complex SLs in lysosomes [

22]. The distinct ceramide/dihydroceramide synthase isoforms involved in the

de novo vs. salvage pathways may be of differential cellular localization [

20]. Therefore, the ceramide biosynthetic pathways and the sphingolipid metabolism are highly compartmentalized with cross talk with complex networking involving transfer protein.

Figure 2.

The schematic representation of three biosynthetic pathways of ceramide including the de novo synthesis, sphingomyelinase, and salvage pathways.

Figure 2.

The schematic representation of three biosynthetic pathways of ceramide including the de novo synthesis, sphingomyelinase, and salvage pathways.

2.1. De novo biosynthesis pathway

The

de novo pathway builds up cellular ceramide pools to meet the demand of rapidly dividing cells by utilizing a simple starting material,

L-ser [

23]. The initial catalysis is localized to the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum, differentiating the polarity. The first step is catalyzed by

serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT). It is the Rate-determining step (RDS) involving a Claisen-type condensation of

L-Ser and the palmitoyl-CoA utilizing co-factor PLP (pyridoxal 5’-phosphate) to afford 3-ketosphinganine (

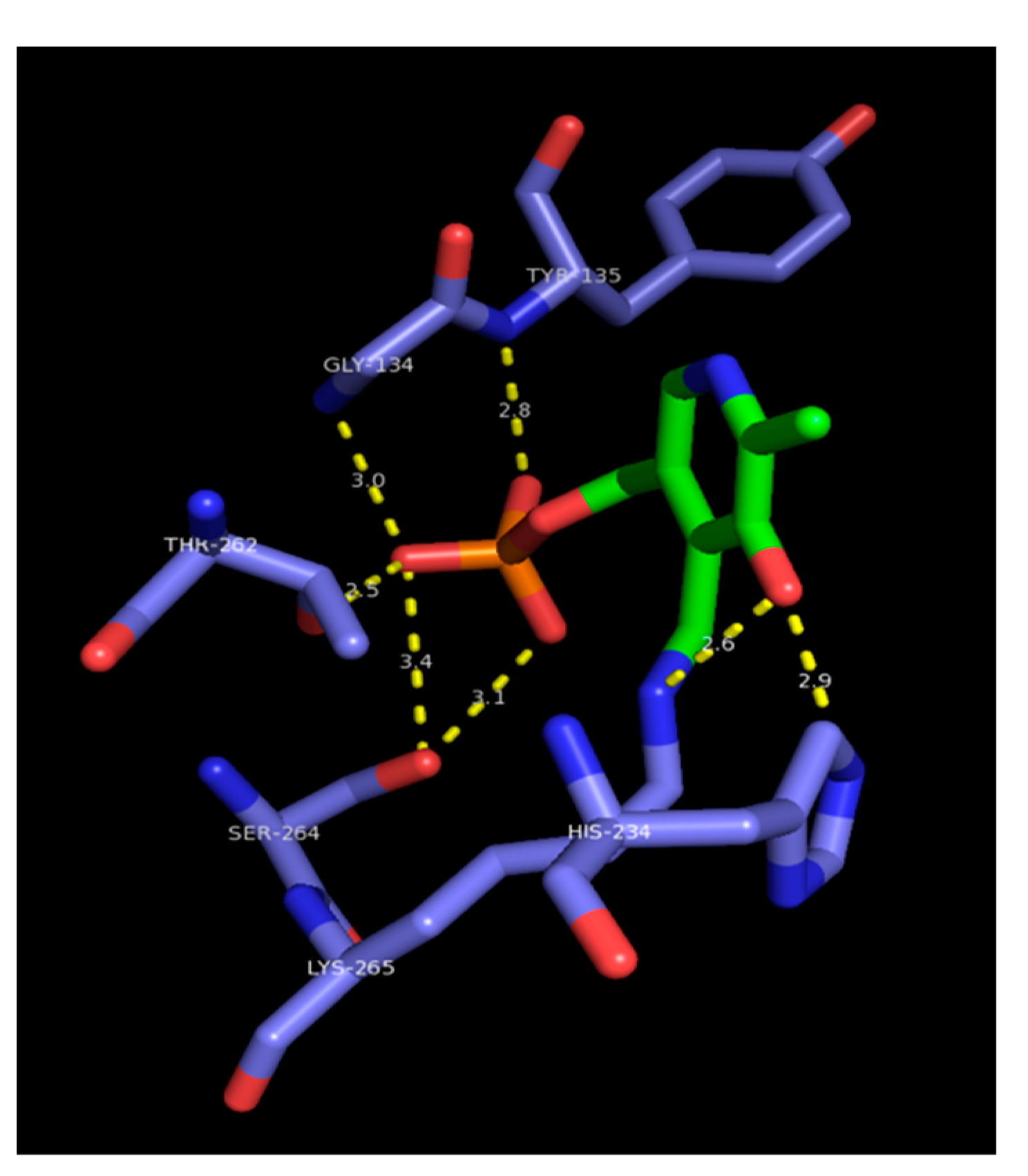

Figure 3).

Several medicinal chemistry approaches targeting SPT were performed to benefit from RDS and control the accumulation of cellular ceramide.

An elegant mechanistic model from Campopiano

et al. [

24] depicts the formation of internal aldimine

Figure 3 with PLP (Green) covalently bound with Lys-265 (Blue) in the enzyme's active site with the substrate Ser. The pentadentate phosphate anion of PLP is near the carboxylate of Ser-264. The resulting β-ketone (Ketosphinganine) undergoes alkyl chain modifications catalyzed by

3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase, ceramide synthases, and finally

dihydroceramide desaturase, resulting in the formation of chiral pool ceramide (

Figure 2). Activation of this

de novo biosynthetic pathway towards ceramide flux is observed in several abnormalities [

25]. For example, during apoptosis, signaling with chemotherapeutic agents [

26] or cannabinoids [

27,

28] and stress responses [

23].

Figure 3.

Serine palmitoyl transferase Claisen condensation type enzyme catalysis. The Cofactor PLP is bound to Lys-265. The phosphate anion of PLP interacts with carboxylate of Ser-264.

Figure 3.

Serine palmitoyl transferase Claisen condensation type enzyme catalysis. The Cofactor PLP is bound to Lys-265. The phosphate anion of PLP interacts with carboxylate of Ser-264.

2.2. Sphingomyelinase (SMase) pathway

The SMase pathway involves hydrolysis of membrane-embedded sphingomyelin by the action of a group of enzymes sphingomyelinases (SMases), resulting in Cer and charged phosphorylcholine [

29]. Sphingomyelinase enzyme is primarily found in the brain and lysosomes. Mutations in the gene expressing sphingomyelinase resulted in Niemann-Pick type A and type B, which are lysosomal storage diseases that are neuropathic and fatal[

30]. SMases can be either acidic or neutral, and the activity of these enzymes can be significantly stimulated by exposure to stress signals like TNF-alpha, oxidative stress, or Fas ligand [

31]. SMases play a vital role in ceramide-related signal transduction. In mammals, four different types of SMases have been identified; these include SMase1 (SMPD2), SMase2 (SMPD3), SMase3 (SMPD4), and a mitochondrial-associated SMase (SMPD5)[

32]. The first mammalian SMase to be cloned was SMPD2 [

33]. SMPD2 is mainly confined to the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear matrix, requiring divalent cations (Mg

2+) for activation [

32]. The metal-based catalysis suggests a possible lone pair of electrons coordinating with metal Mg. Another related metalloenzyme, bacterial phospholipase C (PLC) catalysis involve hydrolysis of phosphate attached to glycerol of the sphingomyelin polar head group resulting in cell signaling phospholipid [

34].

2.3. The salvage pathway

The "salvage pathway" is also known as the "sphingolipid recycling" pathway because it is a metabolic process where the cells effectively recycle the components of broken-down sphingolipids [

35]. The complex sphingolipids are broken down into Sphinganine (Sph), which is then used to synthesize Cer. Various key enzymes are involved in this process, like the SMases, glucocerebrosidase (acid-β-glucosidase), dihydroceramide synthases, and ceramidases (

Figure 2). This process occurs in the acidic subcellular compartments, lysosomes, and late endosomes. This salvage pathway leading to the regeneration of Cer

contributes to almost 50%-90% of sphingolipid biosynthesis [

36]

.

3. Biological significance of Sphingolipids and derivatized sphingolipids

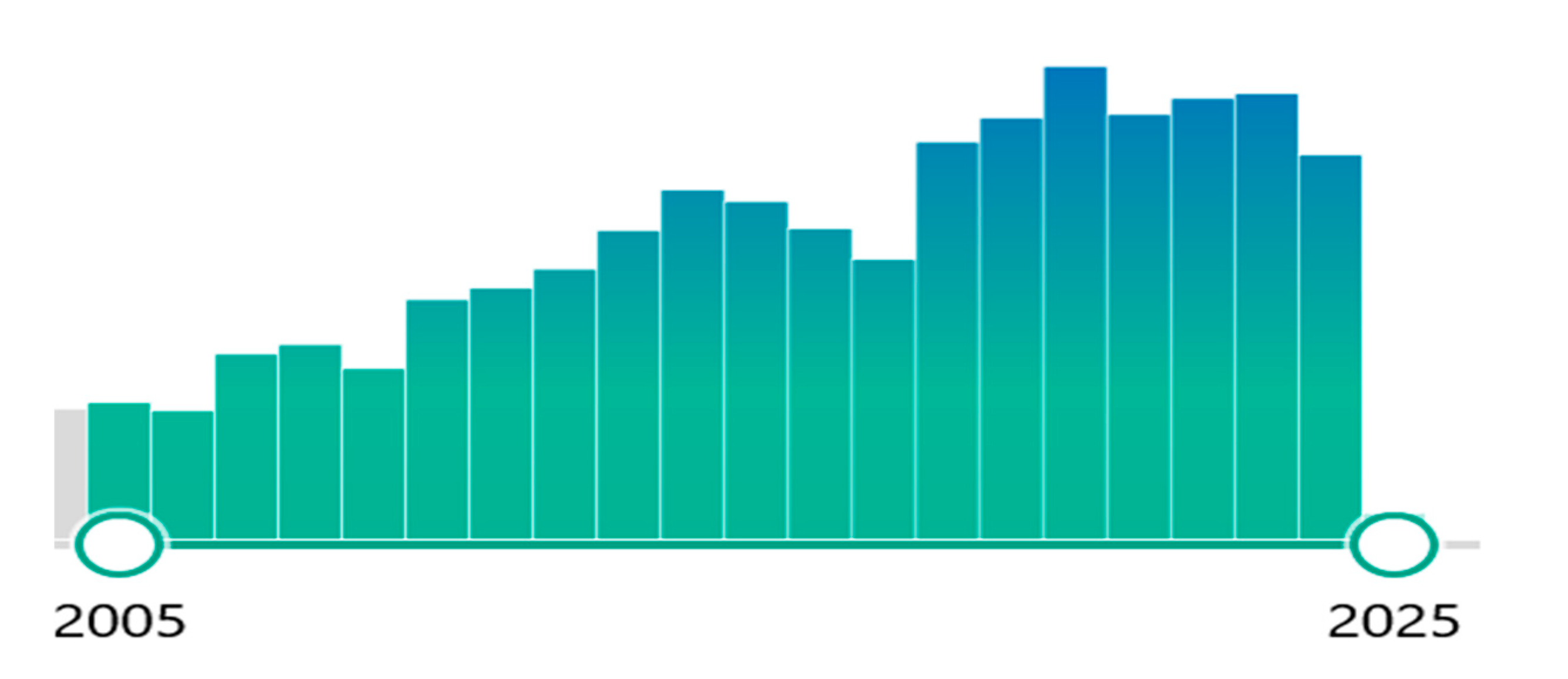

A PubMed search on bioactive sphingolipids in several disease states has reported approximately 3000 studies over the past two decades, and the topic continues to garner attention (

Figure 4).

The main sphingolipids contributing to biological relevance in these studies are complex SLs involving Cer, Sph, S1P, C1P, and GCer (

Figure 5). These are derivatives of the anti-amino-alcohol system in the sphingoid base. Some biological processes in which these derivatized functional sphingolipids are implicated are cell migration, proliferation, inflammation [

37] , and cell death [

3] . These cellular signaling pathways are relevant to autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, inflammation, lysosomal storage diseases, and cancer.

Figure 5.

Oxysphingolipids amine and alcohol derivatizations towards biosynthesis of complex functional sphingolipids.

Figure 5.

Oxysphingolipids amine and alcohol derivatizations towards biosynthesis of complex functional sphingolipids.

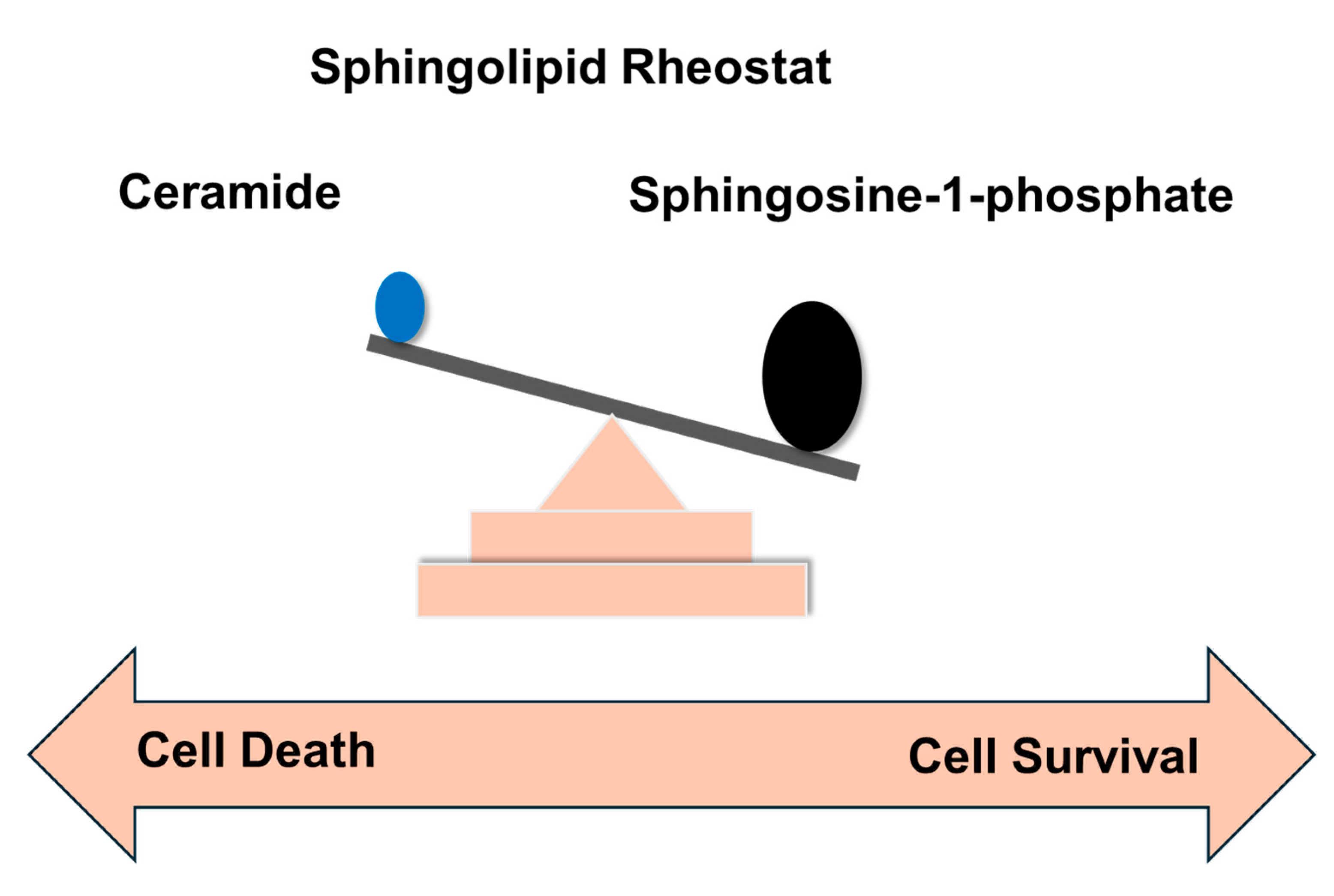

These complex sphingolipids form a functional lipid raft. The raft is observed in the plasma membrane, cell organelles, and membrane vesicles and is also used by budding virions to create a capsule. The significance of the lipid raft in organelle function and cell survival gained prominence with the importance of the Cer /S1P rheostat [38-41].

Disrupted sphingolipid metabolism across different human cancers indicates that bioactive SLs are critical in supporting tumor development, maintaining cancer cell viability, and regulating tumor cell death and survival [

42]. The fast-dividing and growing cell kinetics require membranous organelles for growth. Thus, the best cancer treatments and therapeutics can be developed by carefully controlling the flux of sphingolipids for building membranous organelles. This is more significant in cancer signaling for tumor growth by perturbation of Cer /S1P rheostat [

43]. The therapeutic roles of sphingolipids in various diseases, most notably in cancer, have been elucidated significantly in the past few decades. Still, very few potential drug candidates have been identified, and the full potential of bioactive lipids is yet to be fully realized in the context of ceramide flux and lipid raft function.

4. Sphingolipid rheostat, and significance in cancer

Research efforts from Hannun, Obeid, Lynch, Ogretmen, and Santos groups have extensively contributed towards advancements in sphingolipids biochemistry, and drug discovery efforts [

3,

6,

44] . Cer is considered pro-apoptotic, contributing to various cell death pathways involving cellular functions like growth arrest, differentiation, and programmed cell death [

3,

6,

45]. Sphingosine (Sph), which is produced by the breakdown of Cer, is also pro-apoptotic, contributing to cell death [

46]. S1P is a pro-survival SL that promotes cell growth and proliferation [

47], the opposite of Cer functioning. The evolution of sphingolipid biochemistry with these two opposing biological relevance is prominent in deciding the fate of the cell towards cell survival or cell death (

Figure 6).

The perturbation of this axis is observed in Cer's apoptotic effects [

48]. Elevated Cer levels, resulting from cellular stress, trigger apoptosis and cell death. In response to high Cer levels, enzymes like sphingosine kinase (Sphk) get activated to produce anti-apoptotic S1P, which counteracts the pro-apoptotic effects of Cer [

13]. Cer, a tumor-suppressing lipid, mediates the pro-apoptotic processes such as growth arrest, senescence, differentiation, and apoptosis. Conversely, the tumor-promoting lipid S1P promotes cell proliferation, transformation, migration, inflammation, and angiogenesis [

49]. The individual Cer, Sph, or S1P levels do not determine the cell's fate; it is determined by the ratio between the Cer + Sph and the S1P levels, which is often referred to as the Sphingolipid rheostat or the “Cer /S1P rheostat” [

50,

51]

.

Using medicinal chemistry approaches, sphingolipid rheostat can be moderated to control the cell's fate towards cell survival or cell death. These probes have the potential to identify hits targeting several disease states, including neurodegenerative disorders, inflammatory conditions, and, most importantly, various types of cancer [

43,

52].

Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of small molecules targeting the ceramide metabolism and biosynthetic enzymes.

This review discusses the synthesis and biological significance of sphingoid-based small molecules and their relevance to pre-clinical and clinical studies targeting enzymes involved in sphingolipid biochemistry. We have also performed novel molecular modeling studies to provide details about the enzyme's active site and the ligand. These studies will guide the development of hits. Due to space limitations, we have focused on selected natural products and small molecules that reached pre-clinical and clinical stages. We recognize the enormous medicinal chemistry efforts performed by other groups and apologize if we missed their contributions [100-102].

5. Sphingolipid-based therapeutic agents

Due to the structural similarities with ceramide, sphingoid-based compounds have demonstrated their potential for therapeutic efficacy in various disease conditions, especially cancer. Most biochemical assays suggest modulation of the sphingolipid rheostat and its perturbation. While reviewing the pharmacological action, synthesis, and SAR, we have also performed computational modeling studies to understand the binding interactions of these medicinal agents with the enzymes involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis and metabolism.

The crystal structures were downloaded from the RCSB protein database to develop molecular modeling studies. Ligands used for docking were imported as .mol files and prepared using Ligprep GUI and standard methods. The protein preparation workflow was used to prepare proteins. Missing side chains were filled to develop the binding environment studies. Water molecules were removed beyond 5.00 Å. Het states were generated with Epik. Settings for H-bond optimization were checked and performed with PROPKA. Heavy atoms were converged to RMSD 0.30 Å with force field OPLS4. Glide software was employed for the molecular docking studies.

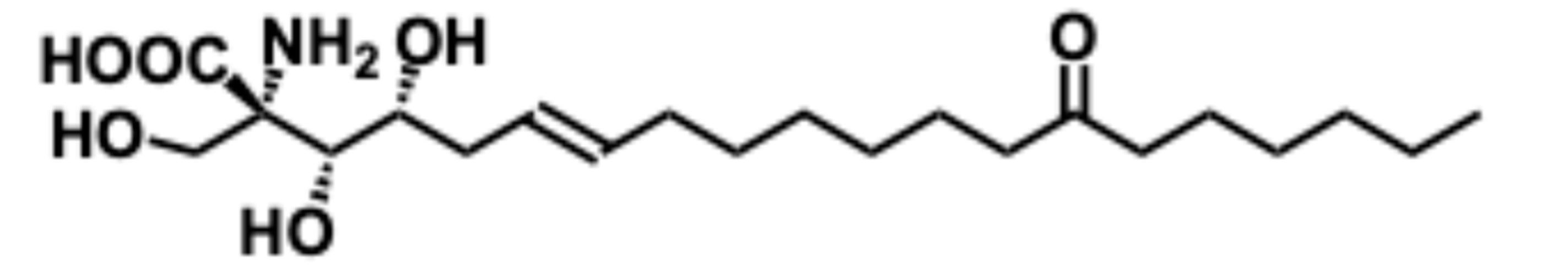

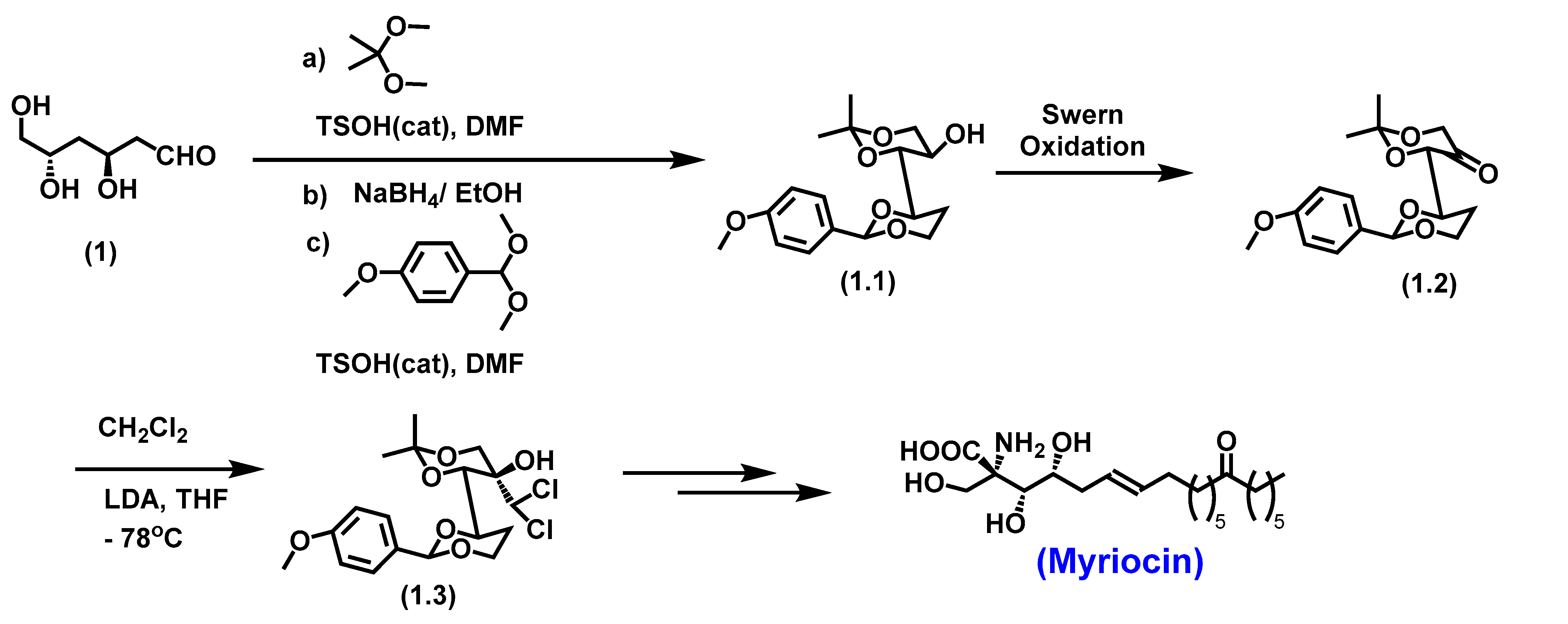

5.1. Myriocin

Myriocin, or ISP-1, is a biologically active sphingoid base with immunosuppression properties. It was first isolated from the fungus

Isaria sinclairii [

103]. Myriocin is a potent inhibitor of serine-palmitoyl-transferase (SPT), which is the very first and the rate-determining enzyme of the

de novo ceramide biosynthetic pathway [

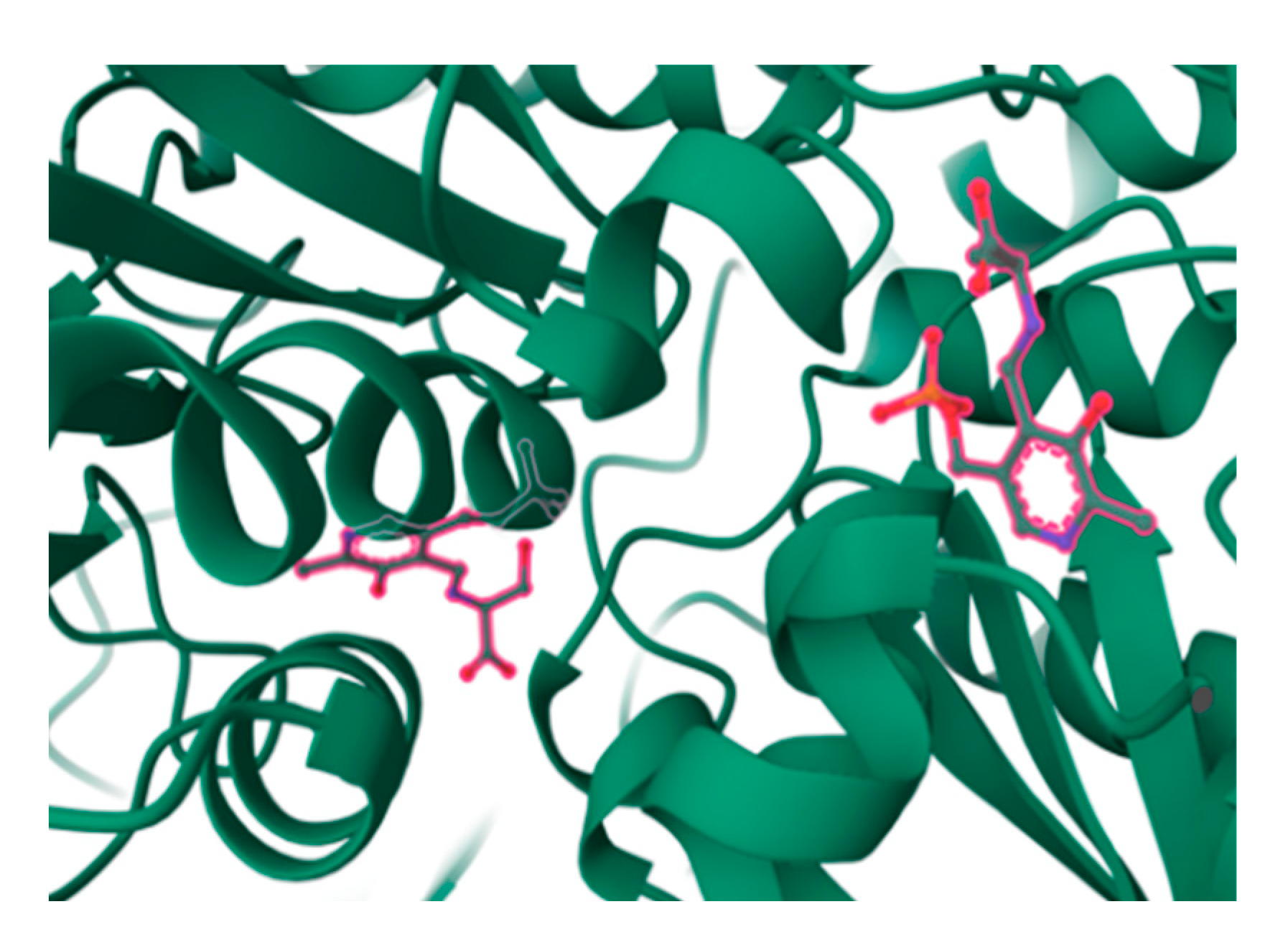

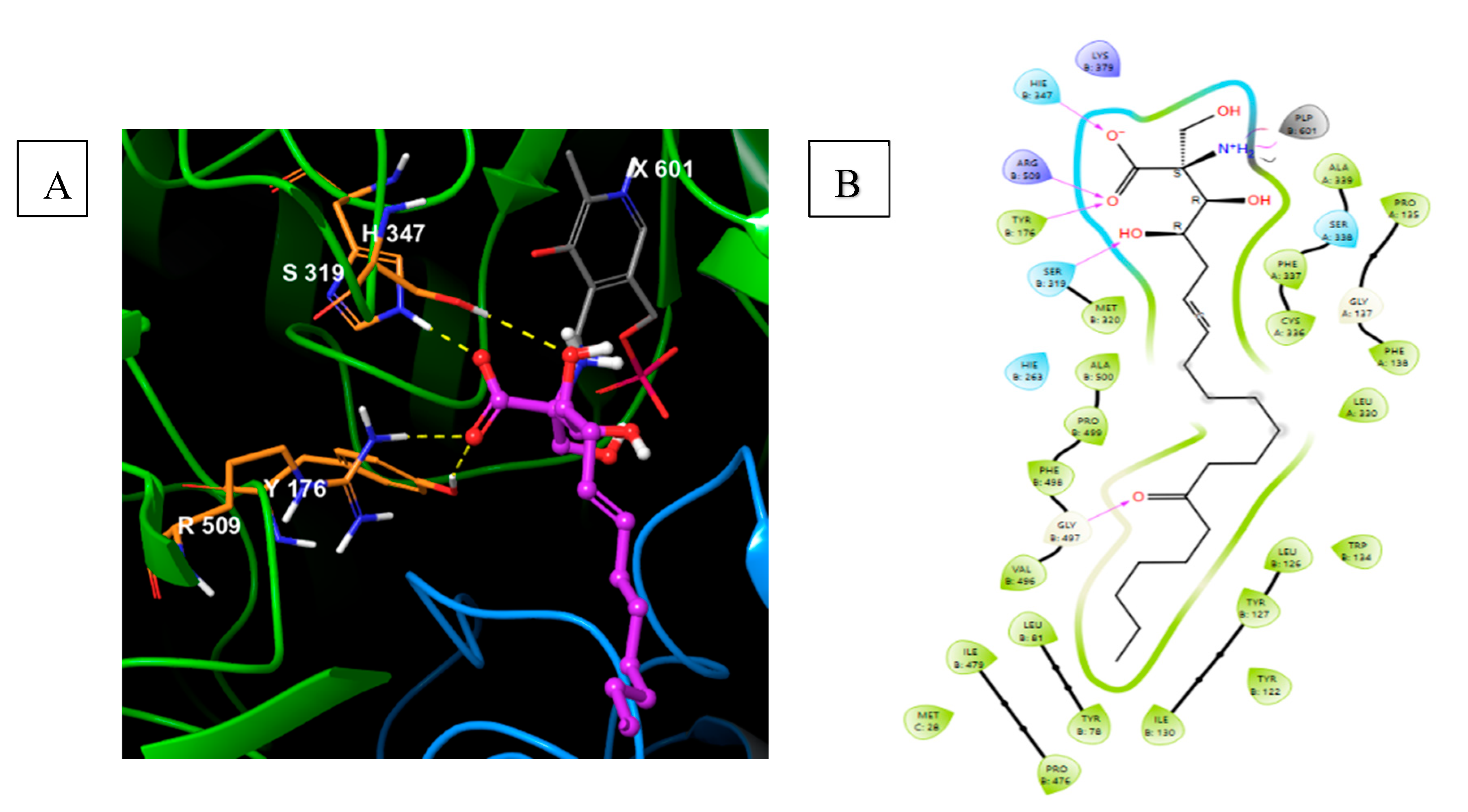

104]. Based on the SPT crystal structure (

Figure 8), the active site involves substrate

L-Ser Schiff-base formation with cofactor PLP (PDB:3A2B,

Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Myriocin - (2S,3R,4R,E)-2-amino-3,4-dihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-14-oxoicos-6-enoic acid.

Figure 7.

Myriocin - (2S,3R,4R,E)-2-amino-3,4-dihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-14-oxoicos-6-enoic acid.

Figure 8.

Serine palmitoyl transferase covalent catalysis involving Schiff-base formation with cofactor PLP (PDB:3A2B).

Figure 8.

Serine palmitoyl transferase covalent catalysis involving Schiff-base formation with cofactor PLP (PDB:3A2B).

Myriocin's physicochemical characteristics involve charged ammonium and carboxylate at physiological conditions with a lipophilic tail. Its biological relevance has encouraged several medicinal and synthetic efforts, contributing to early pharmaceutical development towards understanding immunological applications.

Myriocin was first synthesized by Yoshikawa

et al [

105]. Of the several total syntheses, discussed below is an application of the chiral pool strategy starting from chiral synthon, 2-deoxy-D-glucose. The key reactions involve acetonide protection to afford intermediate 1.1. Subsequent alcohol oxidation under Swern conditions resulted in a keto intermediate 1.2, followed by base-mediated carbanion addition using Darzen’s reaction afforded 1.3. Gem-dichloro intermediate (1.3) is subjected to multi-step synthesis involving protection-deprotection, S

N2, Wittig reaction, and regioselective separation to afford myriocin (

Scheme 1) [

105].

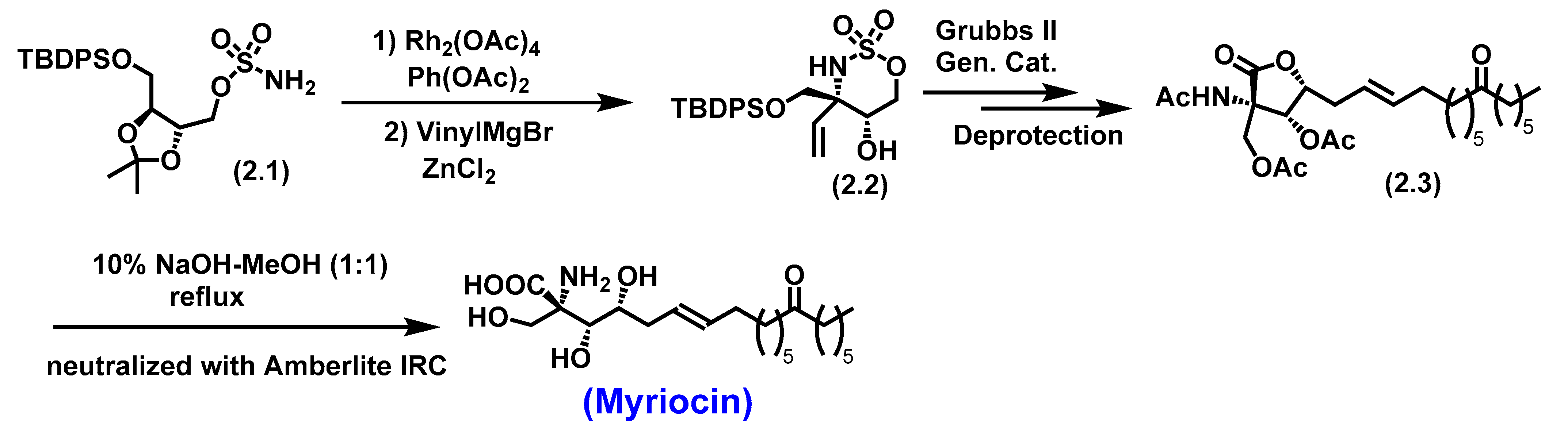

Du Bois

et al completed the total synthesis of myriocin involves a synthetic route that utilizes a quaternary chiral intermediate. The key reactions involved are Rh (II)-catalyzed C-H amination of a sulfamate and olefin metathesis strategy. Reaction of a sulfamate with PhI(OAc)

2 and MgO in the presence of Rh

2(OAc)

4 followed by vinyl addition afforded oxathiazinane

N,

O-cyclic sulphonate ester as a single product (2.2) with a quaternary center. The olefinic handle in

2.2 was subjected to cross-metathesis with a ketone-protected olefin (Type III/IV), affording the required olefinic side chain intermediate

2.3. Subsequent deprotection and oxidation of primary alcohol resulted in aldehyde for intramolecular lactonization to afford

2.3. A final deprotection followed by lactone hydrolysis afforded enantiopure Myriocin (

Scheme 2)[

106].

5.1.1. Biological Significance of Myriocin

Myriocin is an SPT inhibitor that suppresses T-cell proliferation by modulating sphingolipid metabolism. It is also a potent immunosuppressant, inhibiting the proliferation of an IL-2-dependent mouse cytotoxic T cell line, CTLL-2, at nanomolar concentrations [

107].

Myriocin inhibited cell growth in A549 and NCI-H460 lung cancer cell lines through apoptosis by activating the p-JNK, p-p38, and DR4 pathways. It also synergistically amplified the anti-cancer effects of notable drugs like docetaxel and cisplatin [

108].

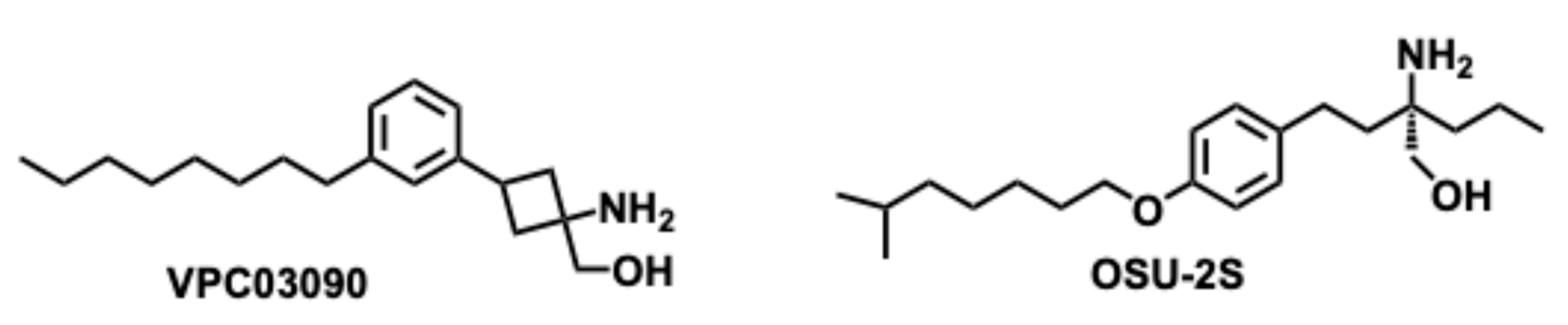

The biological importance of Myriocin has encouraged extensive SAR studies, which resulted in various analogs inspiring the synthesis of amino-alcohol-based scaffold. For example, VPC03090 and OSU-2S (

Figure 10) have structural similarities with Myriocin. These analogs have exhibited anticancer properties

in vitro and

in vivo models. The preliminary studies identified their significance in S1P receptor antagonism in hepatoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric, prostate, and breast cancers [

109]. The S1P receptor is a G-protein coupled receptor that activates with the binding of S1P extracellularly.

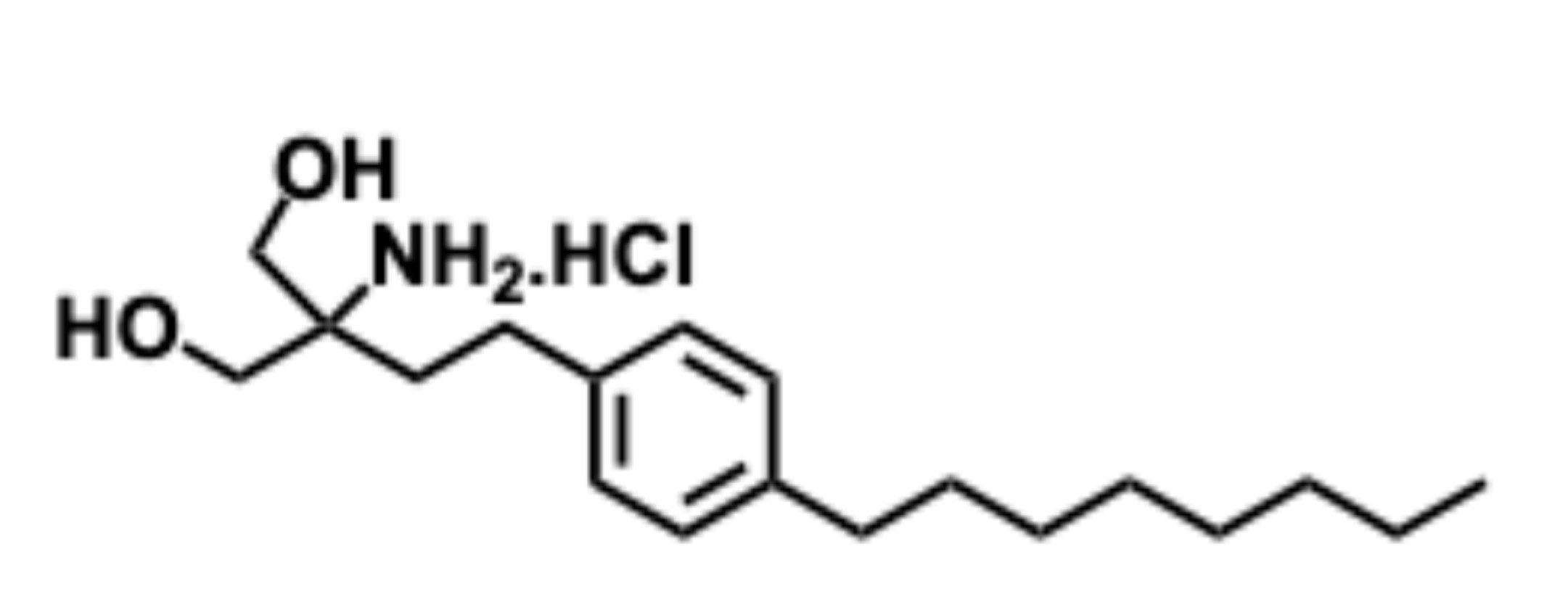

5.2. Fingolimod

Fingolimod (Gilenya) is a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator that was approved by the FDA in 2010 for treating relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) [

110].

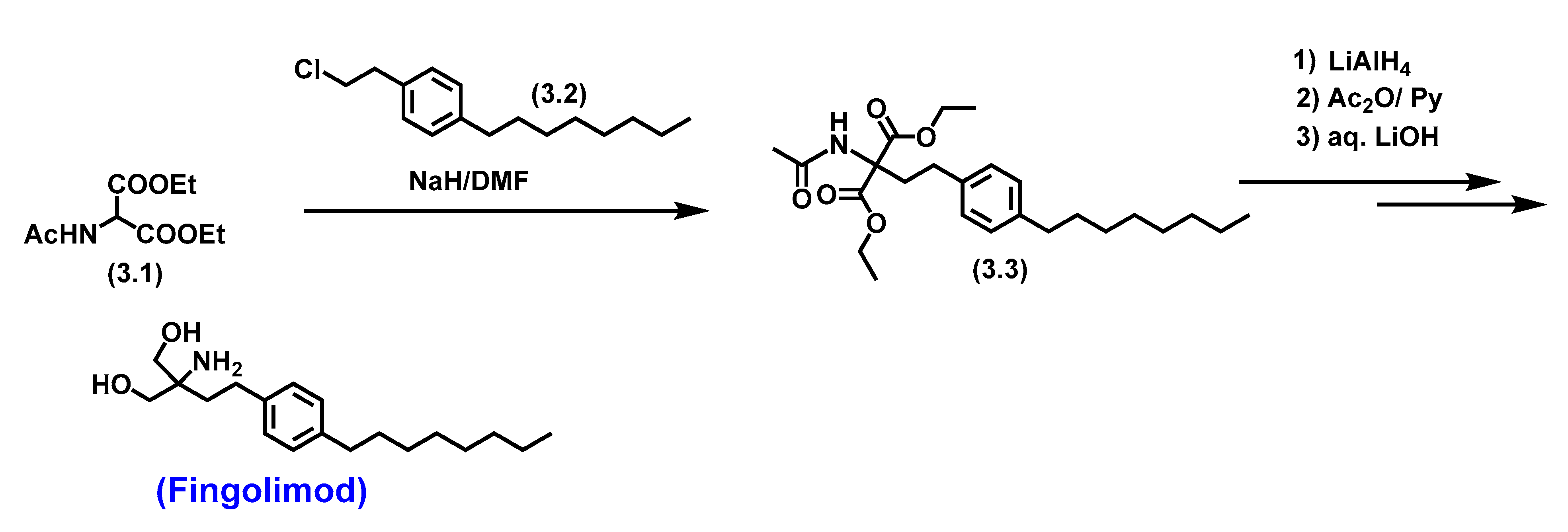

The key step in synthesizing fingolimod involved developing a hydrophilic ‘2-aminopropane-1,3-diol’ head group. An early synthesis of fingolimod employed a base-mediated alkylation of diethyl 2-acetamidomalonate (3.1) with 1-(2-chloroethyl)-4-octyl benzene (3.2) to afford Adachi-Fujita intermediate diethyl 2-acetamido-2-(4- octyl phenethyl)malonate (3.3). Complete reduction of diethyl esters followed by amide deprotection afforded fingolimod (

Scheme 3) [

111].

This first reported synthetic scheme involved developing a polar head group followed by the lipophilic tail, which required extensive chromatography and affected the yields. The unstable reagent (3.2) were another concern, as they affected the cost of the synthesis on a larger scale.

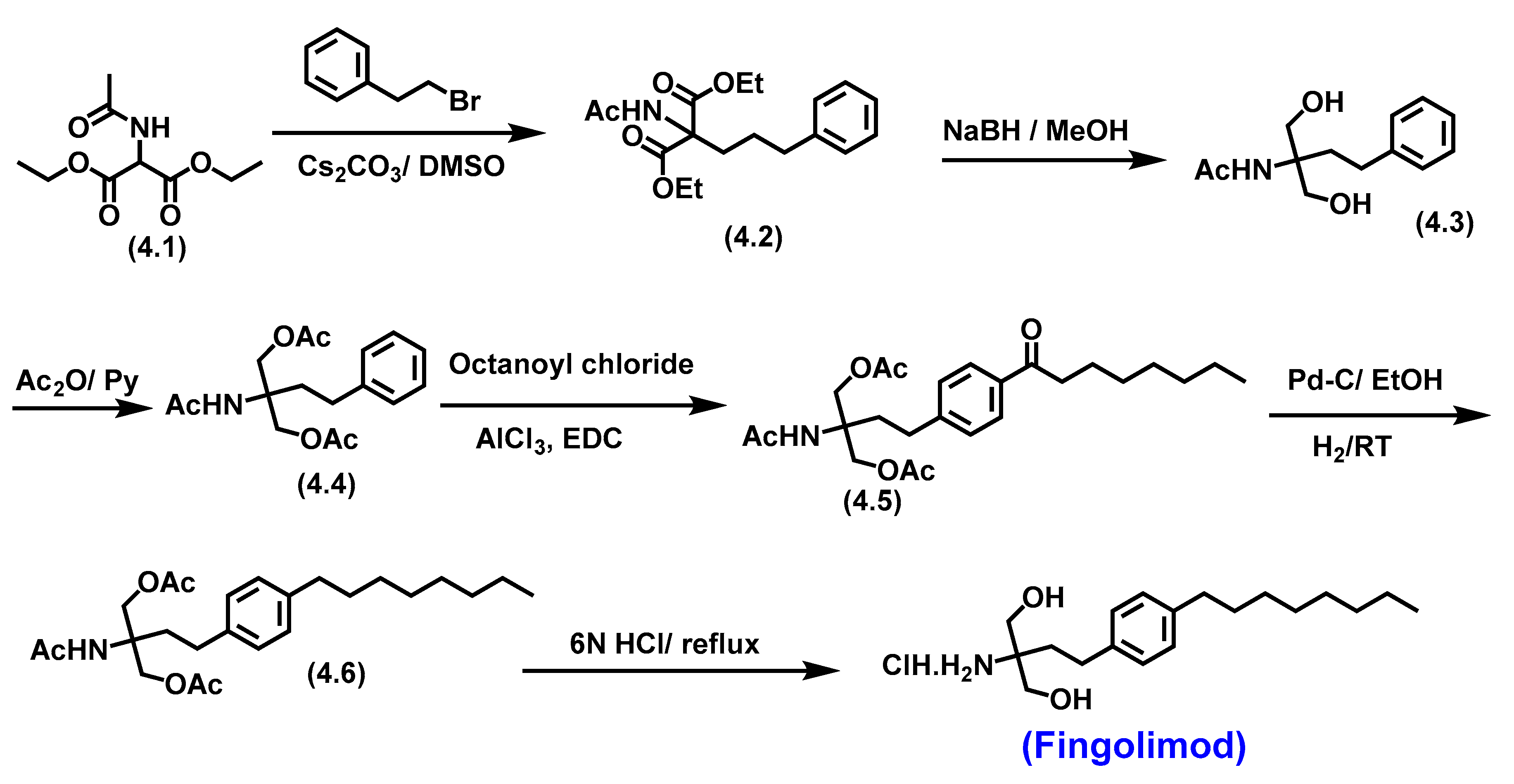

The improved synthesis of fingolimod involved a late-stage incorporation of a polar head group, resulting in scalable, cost-effective synthesis by Kandagatla

et al. [

112](

Scheme 4). The synthesis involved the alkylation of diethyl 2-acetamidomalonate, followed by complete reduction with NaBH

4, affording the polar diol (4.3) and acetyl groups protection afforded

4.4. The lipophilic tail was introduced by Friedel-Crafts acylation on

4.4 to afford

4.5 a keto intermediate. Subsequent keto provides the required saturated lipophilic tail

4.6. Global deprotection with 6N HCl to afford fingolimod as HCl salt [

112].

5.2.1. Pharmacological significance of Fingolimod

Fingolimod is an FDA-approved immunotherapy drug for relapsed multiple sclerosis with a novel mechanism of action. Fingolimod targets S1P as it resembles its ligand and rapidly phosphorylates into fingolimod-P, thus competing with it to bind to the G-protein-coupled S1P receptors (S1P

1,3,4,5) [

113,

114]. It prevents lymphocyte migration by ceasing them in the lymph nodes. It also inhibits lymphocyte production in secondary lymphoid organs, decreasing the number of lymphocytes in systemic circulation and infiltration into the brain and finally attenuating the inflammation [

115,

116].

Fingolimod also inhibits the P13K/AKT/mTOR/p7OS6K signaling pathway, thereby reducing the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma cell lines [

117], the primary cause of death in glioblastoma patients [

118]. It is also a cannabinoid receptor antagonist that inhibits cPLA2 [

119] and ceramide synthase [

120]. Fingolimod is a promising treatment option for patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus by reducing lung inflammation and preventing pulmonary exudation [

121,

122].

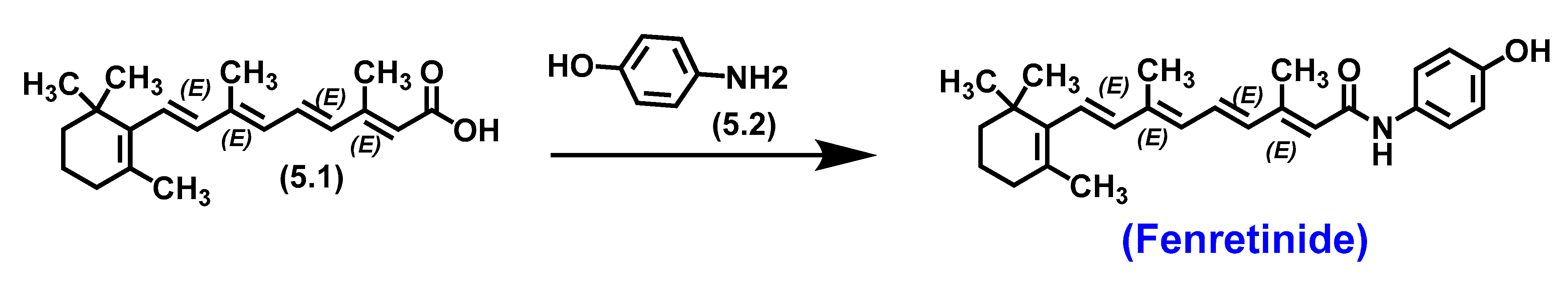

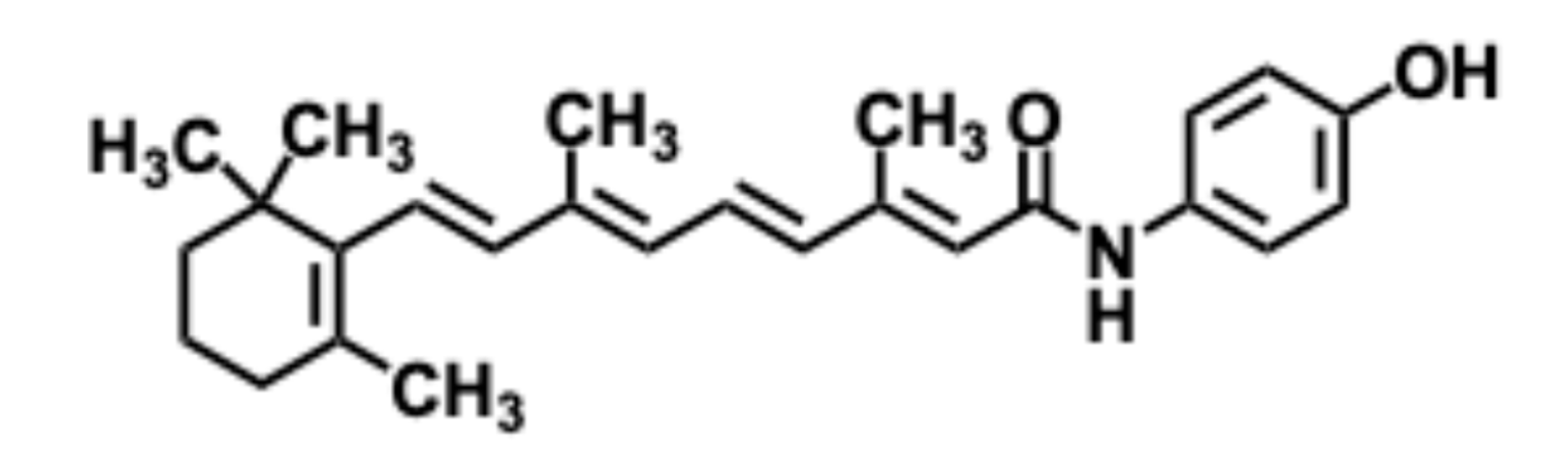

5.3. Fenretinide

Fenretinide, N-4-Hydroxyphenyl-Retinamide (4HPR), is a synthetic derivative of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA ) [

123]. Structurally, Fenretinide is a polyene conjugated system. Gander

et al. from Johnson & Johnson completed the synthesis utilizing a single-step coupling reaction between all-trans-retinoic acid (5.1) and 4-aminophenol (5.2) to explore its potential as a dermatological agent. However, unlike several retinoic acid analogs, it did not exhibit dermatological intervention.

Scheme 5.

Total synthesis of Fenretinide by Gander et al., et al.,.

Scheme 5.

Total synthesis of Fenretinide by Gander et al., et al.,.

5.3.1. Pharmacological significance of Fenretinide

It was not until the 1990s that Fenretinide was investigated for its anticancer potential. Fenretinide primarily works against cancer cells by apoptosis through the accretion of ceramides and reactive oxygen species (ROS) within tumor cells. Fenretinide is one of the few retinoids that showed high in vitro cytotoxic activity against a wide range of targets and several cancer cell lines, including lung, breast, ovarian, head and neck, prostate, and skin cancer cells [124-128]. Since then, it has been and continues to be, evaluated in clinical trials in specific types of cancer such as ovarian, prostate, neuroblastoma, cervical, lung, renal, bladder, breast, glioma, head and neck carcinoma, skin non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Fenretinide can act by retinoid-receptor-dependent and independent of the nuclear retinoid receptor [

129]. Fenretinide thus became a promising candidate for various cancer types, often by disrupting the normal lipid metabolism within cancer cells, leading to cell death, particularly breast cancer, due to its selective accumulation in fatty tissue [

130]. The clinical phase I-III evaluations of Fenretinide have shown minimal systemic toxicity and tolerability [

131]. These studies suggest it is a potent chemotherapeutic agent with limited off-target effects.

The pharmacological significance of Fenretinide garnered the development of novel formulations to overcome the low bioavailability. The notable ones are the complexation of Fenretinide with 2-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin, which resulted in nanoformulations - nano Fenretinide, which exhibited increased bioavailability and therapeutic effectiveness [

132]. A micellar formulation-Bionanofenretinide showed enhanced bioavailability, low toxicity, and potent antitumor efficacy in lung and colorectal cancers and melanoma xenografts [

133]. An emulsion intravenous infusion gave better results than the previous capsule formulations in a manageable safety profile with higher plasma steady-state concentrations of the active metabolite [

134]. These studies laid the foundation for drug formulations and delivery methods for sphingolipid-type scaffold analogs.

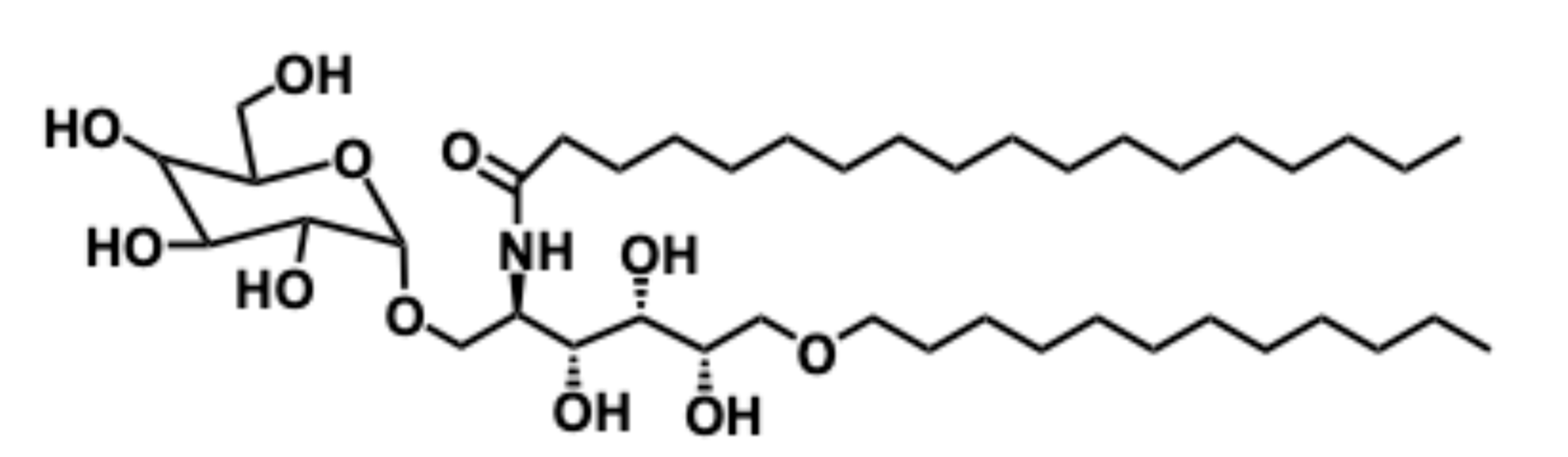

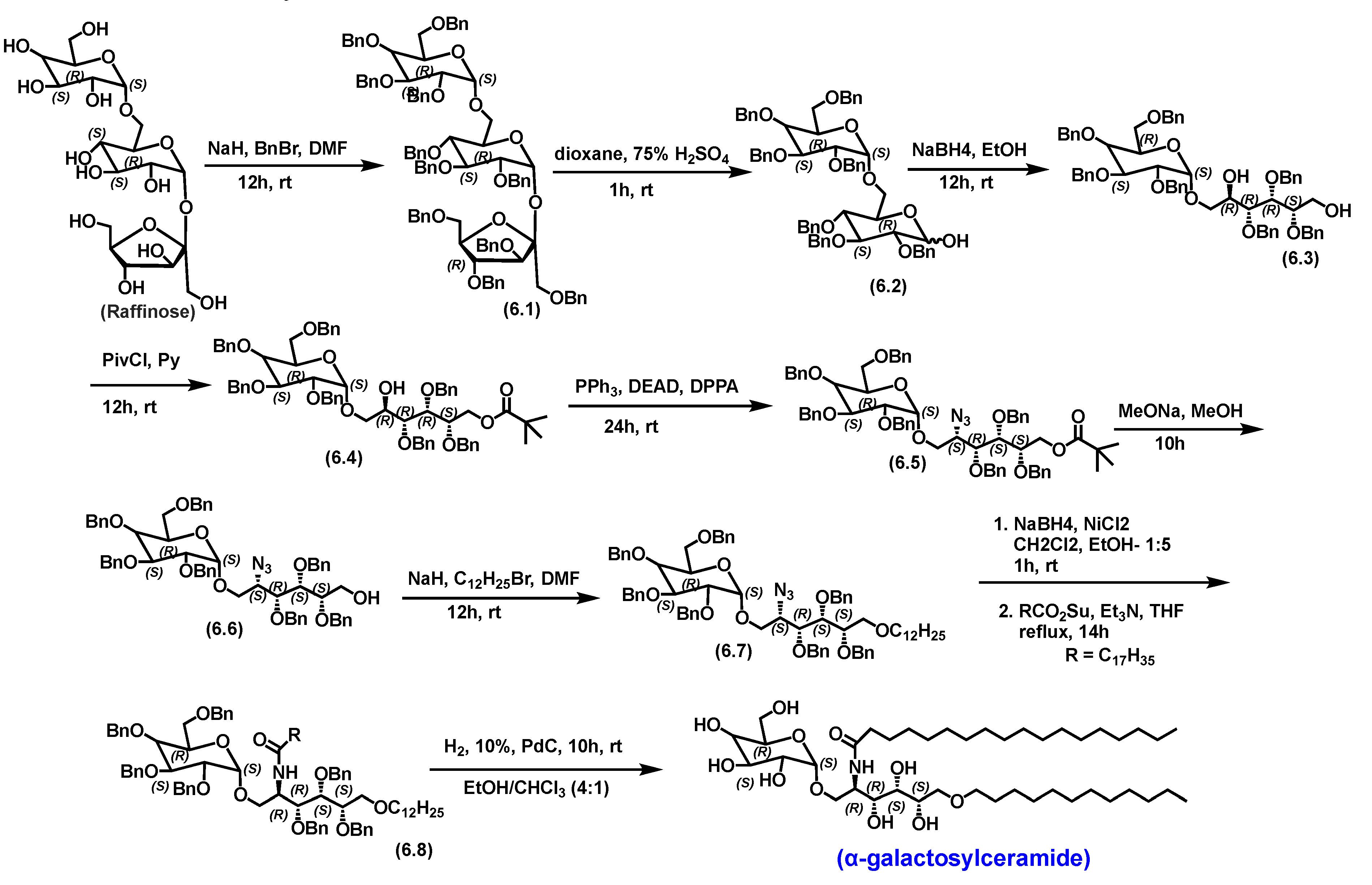

5.4. α-galactosylceramide

α-Galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) is a marine-based natural sphingolipid first isolated from the marine sponge Agelas Mauritian [

135]. Based on the structural core, it is a glycosylated analog of ceramide. Due to its promising antitumor activity, numerous efforts have been made to synthesize this molecule to identify its therapeutic potential. One of the most practical total syntheses of absolute anomeric confirmation of α-Galactosylceramide was developed utilizing chiral pool α-galactoside raffinose (

Scheme 6).

Figure 13.

α-Galactosylceramide -N-((2R,3R,4S,5S)-6-(dodecyloxy)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-1-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)hexan-2-yl)stearamide.

Figure 13.

α-Galactosylceramide -N-((2R,3R,4S,5S)-6-(dodecyloxy)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-1-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)hexan-2-yl)stearamide.

Using the α-galactoside raffinose as the starting material provided the required α stereochemistry of the product. The α-linkage is vital for the biological functions of the glycosphingolipids, and earlier attempts without α-linkage starting materials were challenging to synthesize [

136]. The synthesis involved the protection of alcohols by benzylation to afford

6.1. Acid-mediated selective cleavage of the β-fructofuranosidic linkage in

6.1 afforded hemiacetal (6.2). The subsequent reduction provided a diol (6.3). The primary alcohol in

6.3 was pivaloylated, and the secondary hydroxy was converted to azide (6.5), which was reduced to amine, followed by acylation to afford the amide (6.8). Finally, global debenzylation via catalytic hydrogenation over Pd/C afforded α-Galactosyl ceramide [

136].

5.4.1. Pharmacological relevance and mode of action of α-galactosyl ceramide

α-GalCer’s mode of action relies on binding to the CD1 molecule on antigen-presenting cells, activating invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells. These cells are a subset of immune cells that produce various cytokines, triggering T

h1/T

h2 immune responses. The cytokines effectively modulate the immune system to combat infections, autoimmune diseases, and cancer [

137].

Various studies have demonstrated α-GalCer as a promising anti-tumor agent against multiple cancers, including melanoma, liver, and colon [

138].

Preclinical trial data provided mixed results, even though they demonstrated α-GalCer as well-tolerated, with prolonged overall survival [

139]. However, efficacy was limited in humans due to challenges in effective delivery methods to enhance tumor-specific targeting and optimize immune cell interactions [

135]. The full potential of α-GalCer can only be realized by developing novel target-specific delivery strategies with significantly improved clinical models to optimize new strategies [

135].

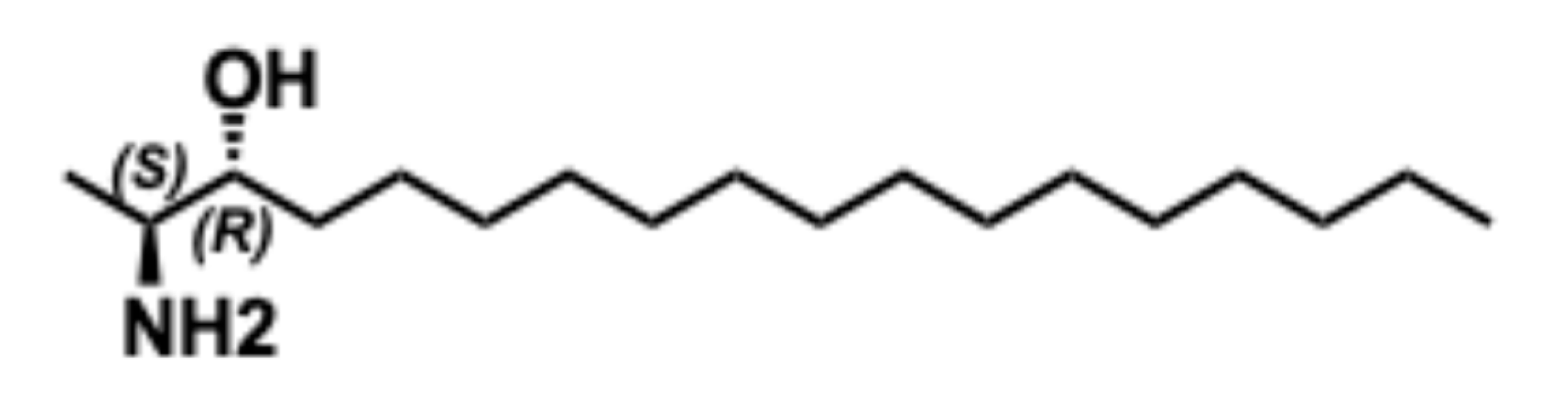

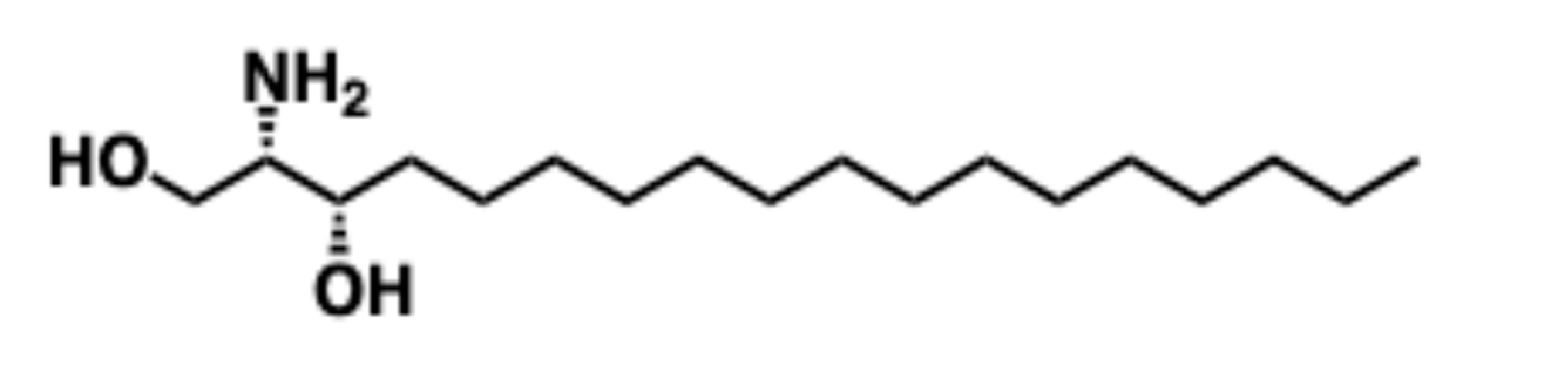

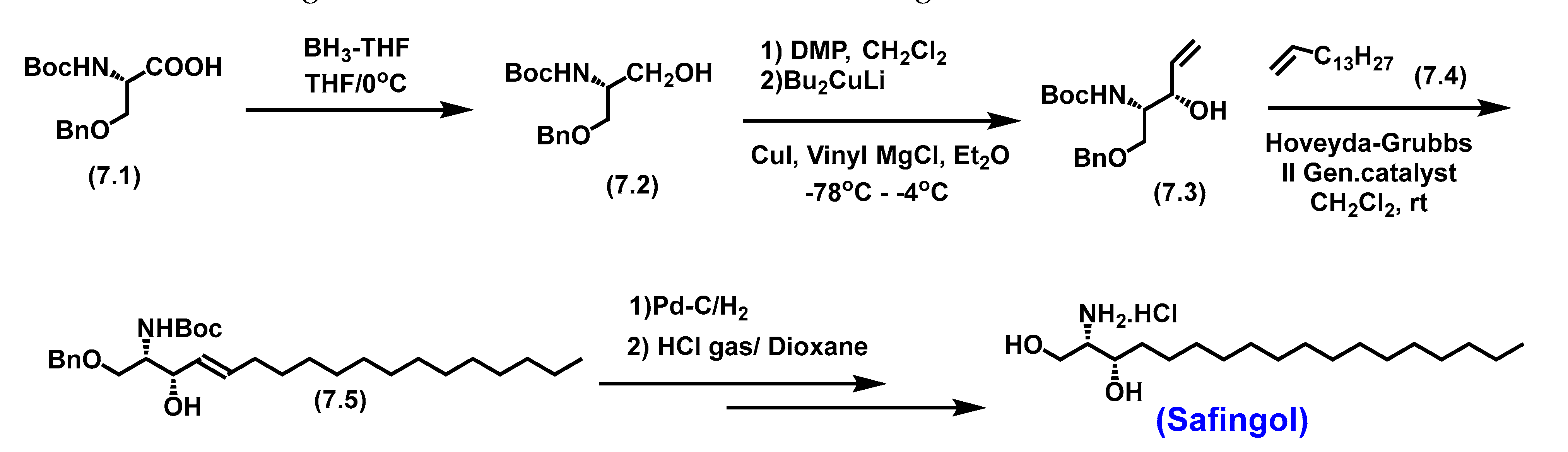

5.5. Safingol

Safingol, known as L-threo dihydrosphingosine, is a potential anti-cancer therapeutic agent [

140].

It’s a synthetic L-threo-stereoisomer of endogenous D-erythro-Sphinganine. Unlike typical sphingolipids with 'anti-amino alcohol’ stereochemistry, it possesses atypical syn amino alcohol stereochemistry. The total synthesis of Safingol starts from L-Serine; the nucleophilic amine and hydroxy groups are protected to afford intermediate 7.2 (Scheme 7). The allyl appendage for cross-metathesis was added by oxidation of primary alcohol to an aldehyde followed by chelation-controlled Grignard addition, resulting in cross-metathesis precursor (7.3). A long-chain alkene is achieved using a cross-metathesis reaction with Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst. Finally, hydrogenation in the presence of Pd/C followed by Boc deprotection afforded Safingol as an HCl salt [

141]

. The common synthetic methodology utilized to afford anti-amino alcohol system is utilize the chelation controlled synthetic efforts. .

5.5.1. Pharmacological relevance and Mode of action of Safingol

Safingol demonstrates its promising anticancer properties as an inducer of autophagy [

142] and a modulator of multi-drug resistance. Safingol is a Sphingosine kinase inhibitor (Ki-

5 µM) and a milder sphingolipid protein kinase C(PKC) inhibitor (

Ki -33

µM) [

143].

Being a Sphingosine kinase inhibitor, Safingol shifts the sphingolipid rheostat towards ceramide accumulation, which is pro-apoptotic by reducing the S1P and thus limiting anti-proliferative effects [

144]. Even though Safingol demonstrated significant

in vitro anti-cancer activity, it showed limited

in vivo activity. The most therapeutic advantage of Safingol that’s being explored is its ability to enhance the

in vitro antitumor effect of various chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin, mitomycin C, and doxorubicin, when used in combination.

Safingol is the first Sphingosine kinase inhibitor that entered the clinical trial as an anti-cancer agent for various cancers like colon and breast cancers as a single agent with good achievable plasma levels consistent with target inhibition and manageable hepatotoxicity. The results of preclinical trials also suggested that Safingol is safe to co-administer with cisplatin, with dramatic potentiation in antitumor properties [

143].

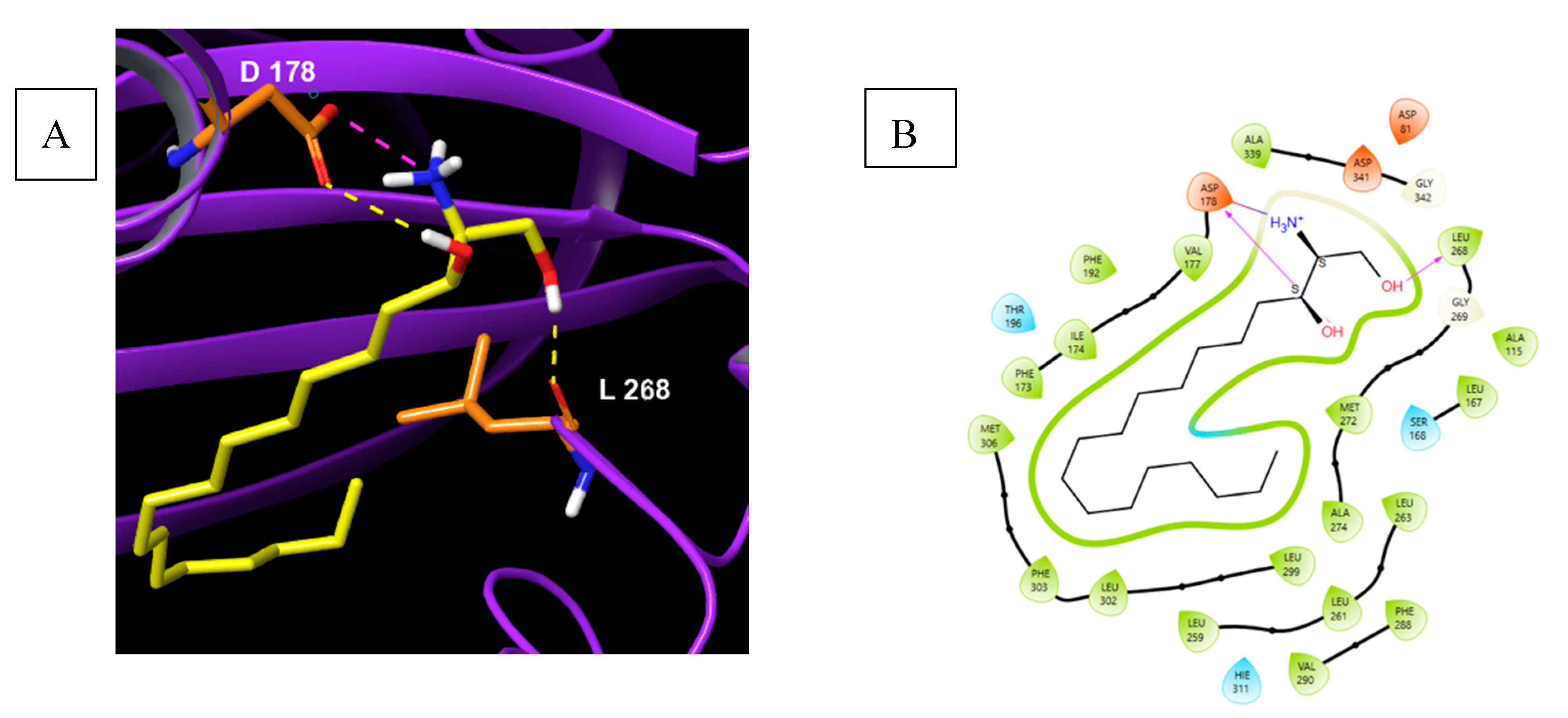

A molecular docking study of Safingol in sphingosine kinase 1 shows a polar head group is in proximity of Asp-178 with H-Bond donor OH and H-Bond interaction with NH2. Both the interactions are highlighted. The terminal methylene alcohol exhibit interactions with Leu-268 amide carbonyl (Fig 15).

5.6. Spisulosine

Spisulosine (ES-285/ 1-deoxy-sphinganine) was first isolated from the clam

spisula polynyma, proclaiming its marine origin [

145]. Due to its strong antiproliferative potential, it has gained notable importance. Some significant syntheses are discussed below.

Figure 16.

Spisulosine - (2S,3R)-2-aminooctadecan-3-ol.

Figure 16.

Spisulosine - (2S,3R)-2-aminooctadecan-3-ol.

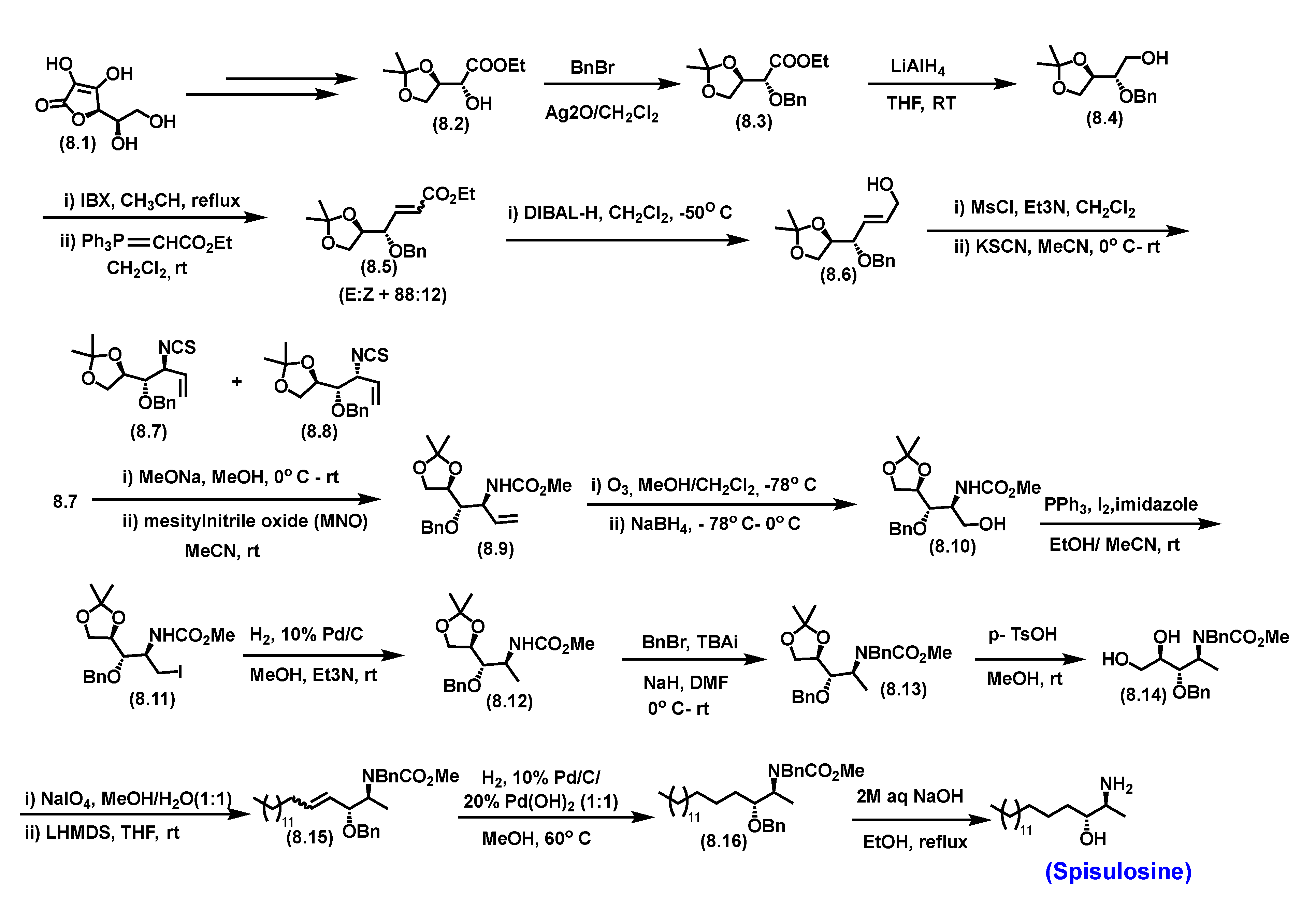

5.6.1. Synthesis of Spisulosine

One of the total syntheses of Spisulosine involved a substrate-controlled aza-Claisen rearrangement, which set the anti-amino-alcohol motif. The methyl head group was created by deoxygenation. The 15-carbon chain was obtained by Wittig olefination and subsequent hydrogenation, as shown in

Scheme 8 [

145].

As shown in

Scheme 8, starting from D-isoascorbic acid, a known ester 8.1 was prepared on a multi-gram scale. Benzylation of

8.2 followed by reduction afforded the acetonide alcohol (8.4). Subsequent oxidation and witting provided the olefinic ethyl ester (8.5). Mesylation followed by S

N2 addition afforded a mixture of enantiomers (8.7) and (8.8). Several method development studies were performed towards increasing the diastereoselectivity of

anti-8.7 over

syn-8.8. After optimization, starting from

8.7, a carbamate intermediate (8.9) was synthesized upon mesiyllnitrile oxide (MNO) treatment. The olefin in (8.9) was subjected to ozonolysis and reduction to afford alcohol (8.10). The alcohol was converted to iodo intermediate followed by reduction afforded (8.12).

N-benzylation followed by acetonide deprotection afforded Vic-diol (8.14). Periodate oxidation of vicinal diol, which was then treated with a non-stabilized ylide, produced a barely separable mixture of olefinic intermediates (8.15). Repeated chromatographic separation afforded pure (

Z)- 8.15. Saturation of double bond and removal of both benzyl ether protecting groups under catalytic hydrogenation gratifyingly provided Spisulosine.

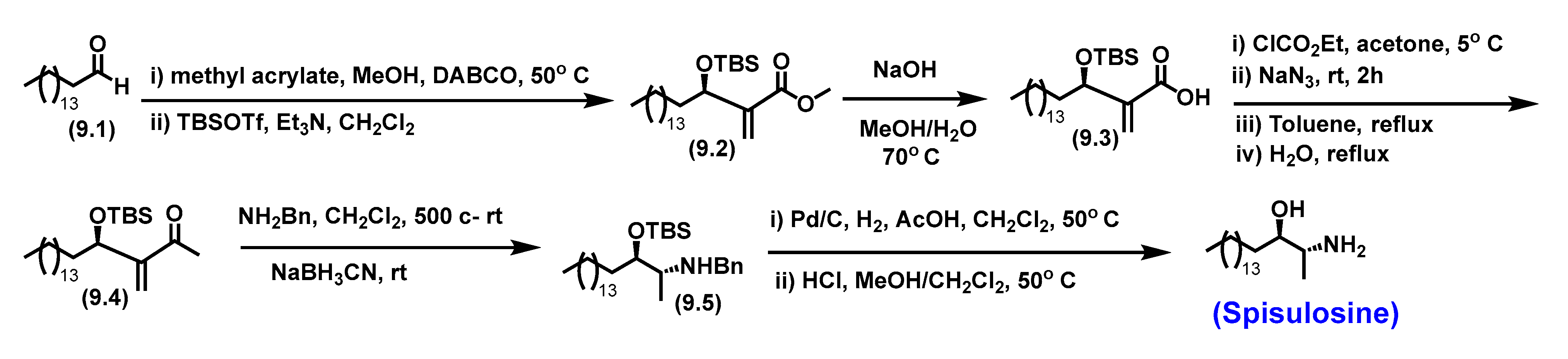

An improved synthetic method discussed here involves a Morita-Baylis-Hillman adduct

; hexadecanal (9.1) was subjected to a Morita-Baylis-Hillman reaction in the presence of DABCO with methyl acrylate, converting the aldehyde to methyl ester (9.2). The yield of this very first step was not as good as hexadecanal, which is a long-chain aldehyde and is not a much desirable substrate for the Morita-Baylis-Hillman reaction. The subsequent hydrolysis of ester to acid (9.3) followed by reductive amination to afford the benzylamine (9.5) and finally deprotection afforded free amino-alcohol Spisulosine (

Scheme 9) [

146].

5.6.2. Pharmacological relevance and mode of action of Spisulosine

On studying the sequence of molecular level events triggering apoptosis and examining its effects on the “cell death markers,” it was observed that Spisulosine triggers apoptosis by activating caspase 3 and 12 and modifying the phosphorylation of P53. Spisulosine induces phosphorylation of MARCKS just like the sphingonine-related lipids. However, Spisulosine is not an inhibitor of PKC; instead, it’s an activator of PKC at the cellular level, unlike its analogous sphingonine-related lipids. Spisulosine did not affect other pathways involved in cell survival/apoptosis, such as JNK, Erks, or Akt, suggesting triggering an atypical cell death [

147]. In

in vitro studies, Spisulosine showed an activity of 1 - 10 μM against both PC-3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cell lines by increasing intracellular ceramide levels. This ceramide level increase was not observed when challenged with ceramide synthase inhibitor Fumonisin B1. Ceramide synthase is involved in the salvage pathway towards the biosynthesis of ceramide. This indicates that cellular ceramide level increase resulted via a

de novo biosynthetic pathway and how complex the sphingolipid’s biochemistry is regulated and compartmentalized [

148].

Activation of PKCζ, a target protein of ceramide, was also observed in PC-3 and LNCaP prostate cancer cell lines. The results obtained with specific inhibitors of various pathways inferred that the anti-proliferative effect induced by Spisulosine in prostate cancer cells was independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), p38/ classical protein kinase C (PKCs) pathways, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/(P13K/Akt). Another study indicates that Spisulosine cytotoxicity is due to the prevention of the formation of stress fibers, which ultimately decreases the activity of Rho proteins [

149].

Several clinical trials were conducted on Spisulosine owing to its antiproliferative activity. The results were not promising; one of the phase 1 trials indicated induction and elevation of the liver enzymes, resulting in dose-limiting for Spisulosine and low antitumor activity[

150]

. Other Clinical trials also indicated hepato- and neuro-toxicity as schedule-independent dose-limiting adverse events [

2].

Another phase 1 clinical trial was designed to identify the recommended and maximum tolerated doses (MTD)for phase (II) trials. This study also evaluated the safety profile, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary efficacy data in patients with advanced solid tumors. The results indicated dose level VIII (200 mg/m

2) as the MTD, and dose level IX (160 mg/m

2) was defined as the RD. This study also indicated limited antitumor activity [

151].

These adverse events correlate to the poor physicochemical properties of Spisulosine resulting from the structure including the long hydrocarbon chain's high lipophilicity and intramolecular hydrogen-bond formation between the hydroxyl and the amine functionality, hindering the ionization of the functional groups, lowering the pH to much lower values than commonly seen for primary amines. The basic amine salts improve the water solubility. Even though adequate solubility in salt form may be achieved, another issue is the tendency towards gel formation due to aggregation of the lipophilic portion of the molecule over time in plasma. These features interfere with the infusion of aqueous solution. It was evidenced in the Phase II clinical trial that the time for infusion increased up to 24 to even 72 hours, which would result in gel formation [

152]

. This observation resulted in halting clinical trials for Spisulosine.

These studies warrant new drug delivery platforms for therapeutic applications of Spisulosine and its analogs.

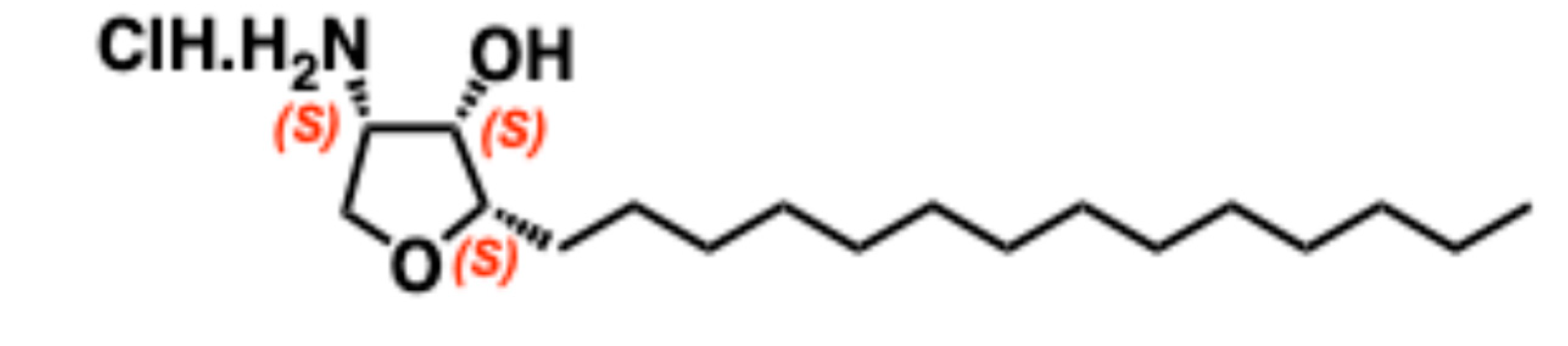

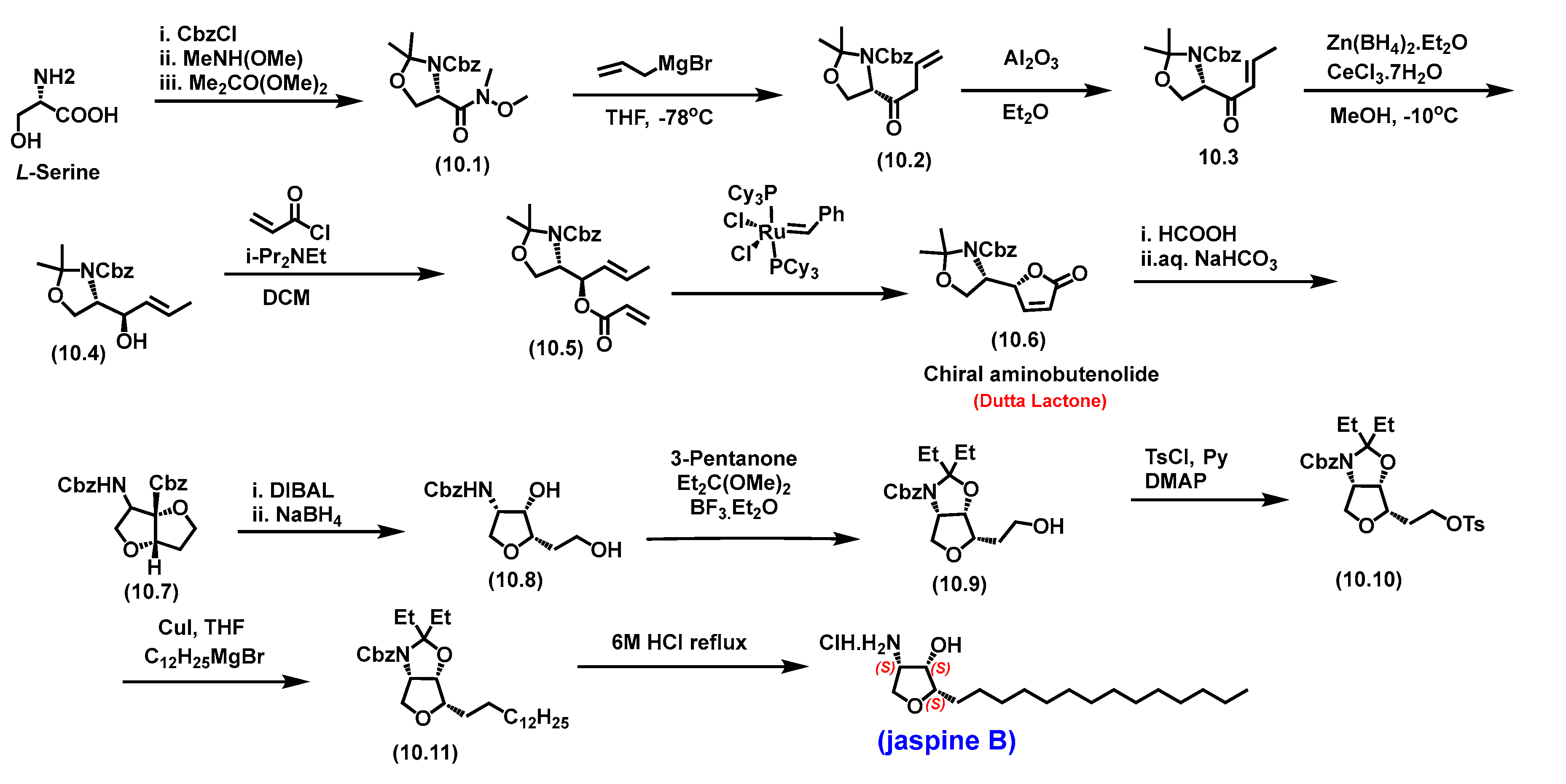

5.7. Jaspine B

5.7.1. Synthesis of Jaspine B

Jaspine B (pachastrissamine) is an anhydrophytosphingosine extracted from the marine sponge

jaspis sp.[

153]. It has effective anti-cancer activity against several human carcinomas [

154]. The gram-scale synthesis of jaspine B starts from naturally abundant L-Ser utilizing a chiral pool strategy to afford an advanced chiral intermediate, Dutta lactone (10.6,

Scheme 10). The total synthesis design strategy involved using a chromophoric Cbz-L-Ser over

N-Boc-L-Ser functionality. This helped the robust purification of several intermediates utilizing the Combi-flash purification system for scale-up to afford an advanced chiral intermediate, Dutta lactone. Jaspine B, as such, is a non-UV active natural product on thin-layer chromatography. Strategic incorporation of Cbz protecting functionality in the first step significantly helped synthesize multi-gram scale batches and chromatography. It is very well tolerated in acidic and base environments and was retained until the precursor step of jaspine B starting from

L-Ser.

Synthesis of jaspine B utilizes a chiral pool strategy starting from L-Ser (

Scheme 10). Initial steps involve

N-Cbz protection followed by amidation of carboxylic acid and acetonide protection to afford Weinreb amide (10.1). This scale-up is a very robust, efficient methodology executed on a 50 g scale. Weinreb amide (10.1) is subjected to Grignard addition using allyl. Mg. bromide followed by double bond migration to afford thermodynamically favored unsaturated trans ketone (10.3). A chelation-controlled reduction of a trans ketone using a freshly prepared Zinc borohydride reagent afforded trans-alcohol intermediate (10.4). Acroylation of

10.4 provides the acrylate intermediate (10.5) as a greasy liquid. Utilizing Grubbs I

st Gen. catalyst, a Ring Closing Metathesis (RCM) of

10.5 acrylate affords Dutta lactone (10.6,

Scheme 10). Utilizing the Teledyne combliflash chromatographic system, all the intermediates can be subjected to chromatographic separation, resulting in reduced solvent utilization and increasing efficiency by reducing time and manpower.

Dutta lactone is a second-generation advanced chiral intermediate with inherent chirality, unsaturated lactone (Michael acceptor), and protected nucleophiles (OH, NH

2). Acetonide deprotection of this lactone affords thermodynamically favorable enantiopure bicyclic furafuranone as the only product. The required all-syn tri-substitutions are achieved in this transformation. Functional group transformation of the lactone in bicyclic furafuranone provides an

N, O-protected jaspine B precursor (10.11). Global deprotection affords jaspine B as HCl salt [

155], as shown in

Scheme 10.

5.7.2. Pharmacological relevance and mode of action of Jaspine B

Structurally jaspine B resembles ceramide (

Figure 13). This close similarity makes it a probe and interferes with ceramide metabolizing enzymes. Jaspine B was extensively tested in several

in vitro and

in vivo studies. Some mechanistic studies involved necroptosis followed by cell death [

156] and mitosis-mediated programmed cell death [

157], among others. Datta et al.. developed an efficient synthetic route using an

L-serine-derived bicyclic lactone as an advanced chiral building block [

158] . Utilizing this synthesis, our groups have accomplished the synthesis of a gram quantity of jaspine B. We have used this knowledge to understand membrane binding potential and develop a sphingolipid-based structural core formulation for novel drug delivery platforms.

In collaborative efforts, a novel liposomal formulation was developed using jaspine B [

159]. The novel liposome drug delivery system has addressed jaspine B’s low bioavailability issues with control and improved its therapeutic efficacy.[

160] There have also been few pharmacokinetics and ADME studies to understand the mechanisms of intestinal-absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of Jaspine B in rats [

161]. Jaspine B does not have excellent bioavailability, but only 6.2% [

161]. Several studies have suggested increased bioavailability of jaspine B by co-administration with bile salts and micelle formations [

161] . The lipophilic cholesterol portion might interact with the lipophilic portion of jaspine B in this formulation. Jaspine B was observed to be a highly tissue-distributed compound with higher concentrations in the brain, kidney, heart, and spleen [

161].

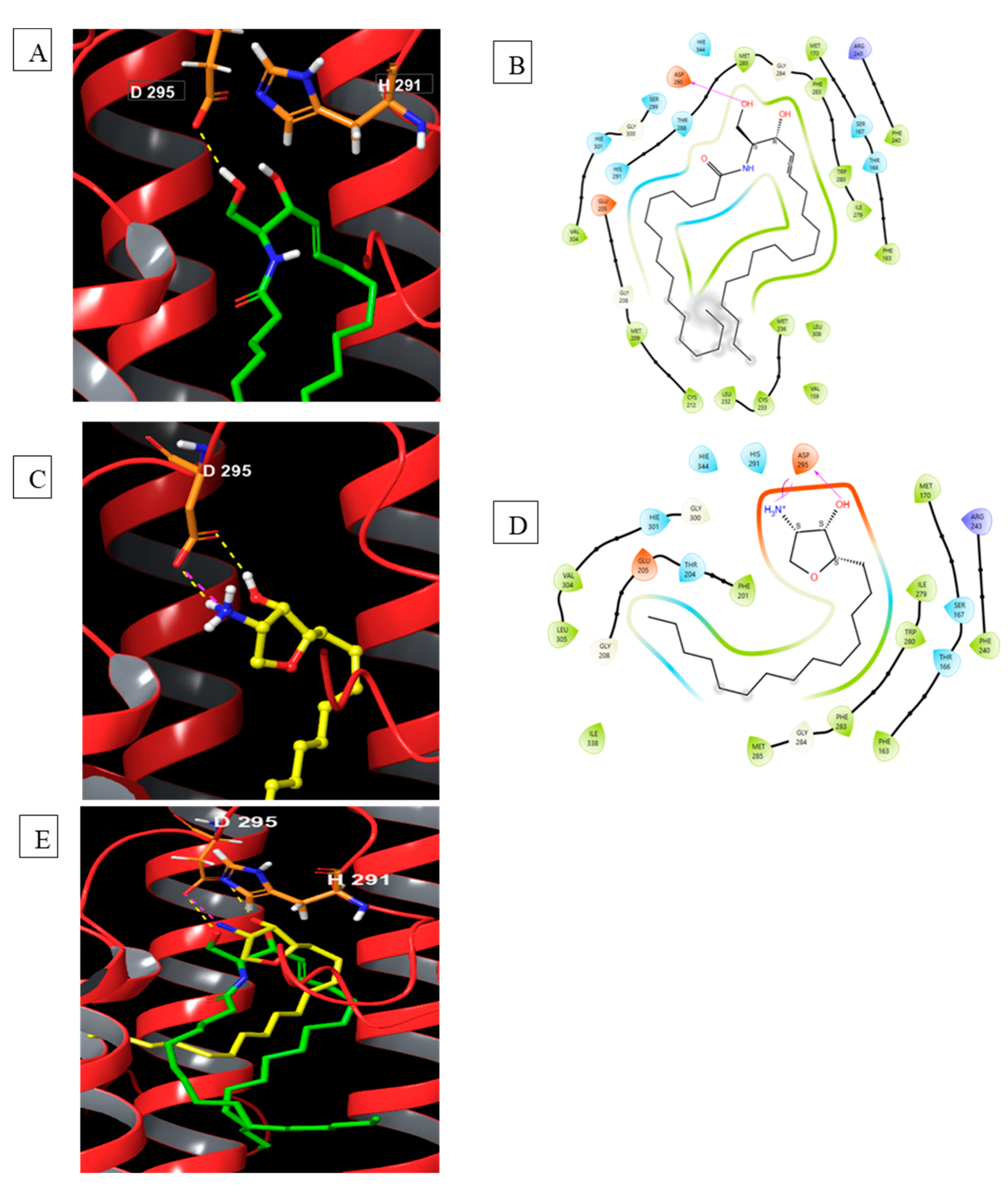

Towards understanding binding interactions with sphingomyelin synthase 1 (

Figure 18), SMS-prepared protein is subjected to the binding of ceramide, its natural substrate, followed by the natural product jaspine B. The key observations are similarities of lipophilic portions binding in the same environments of the prepared protein for both molecules.

Figure 18-E shows the olefinic tail and the jaspine B tetradecyl side chain have structural overlays. The tetrahydrofuran core interacts with amino acids like the ceramide polar head group.

These studies suggested that structural similarities with ceramide have the potential to bind in the same environment as the enzyme substrate. This further supports the pharmacological intervention studies with jaspine B and ceramide for drug discovery efforts.

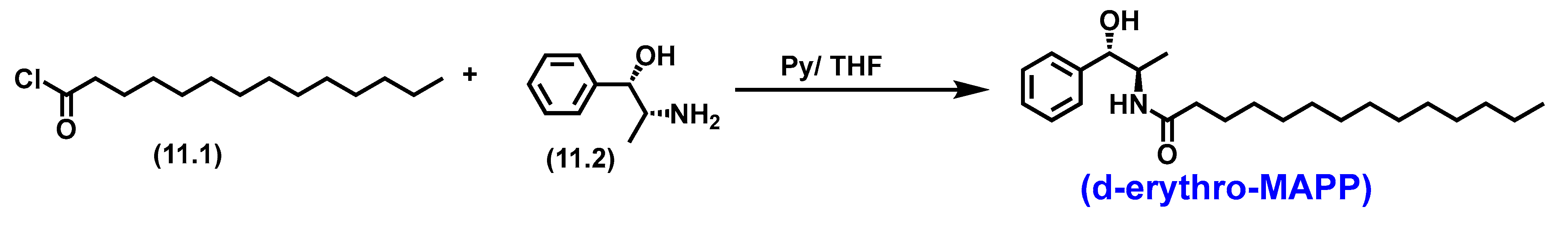

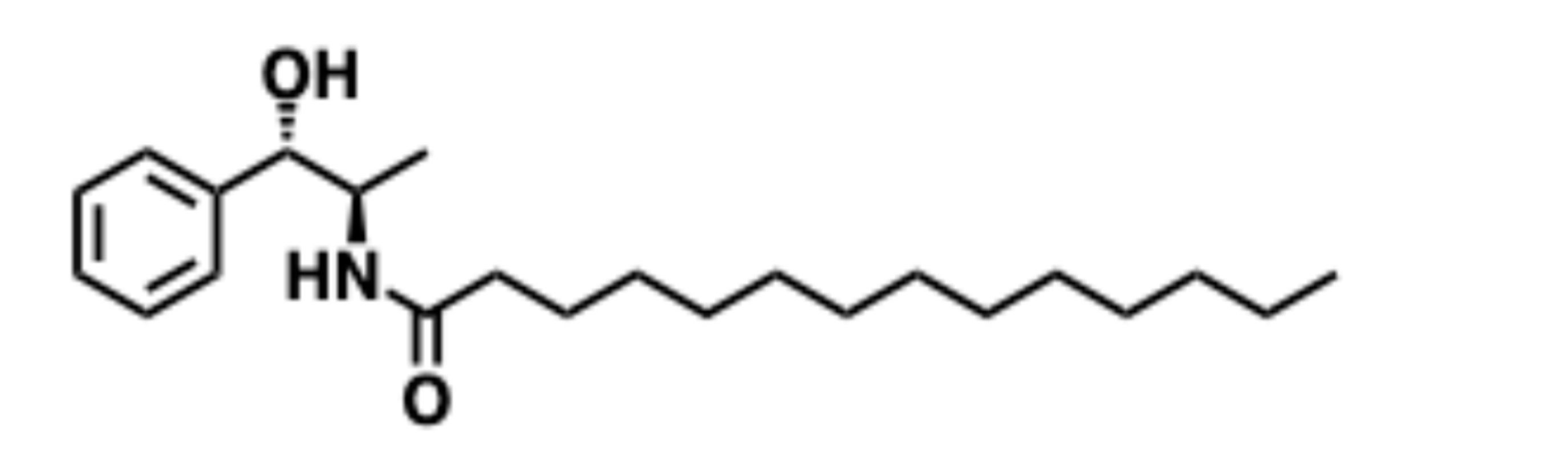

5.8. d-erythro-MAPP( D-e-MAPP)

d-e-MAPP is a stereochemically opposite enantiomer to the typical

L-sphingolipids, and only the D-stereoisomer has exhibited the antiproliferative effect. The

L-stereoisomer (L-e-MAPP) is inactive [

162]. Therefore, stereospecific syntheses were necessary to afford D-enantiomer selectively.

One of the syntheses mentioned in the literature involves a single-step coupling reaction between (1

S,2

R)-2-amino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol and the tetradecanoyl chloride in the presence of organic base pyridine and THF as the solvent [

163].

Scheme 11.

Total synthesis of D-e-MAPP by Chang et al.

Scheme 11.

Total synthesis of D-e-MAPP by Chang et al.

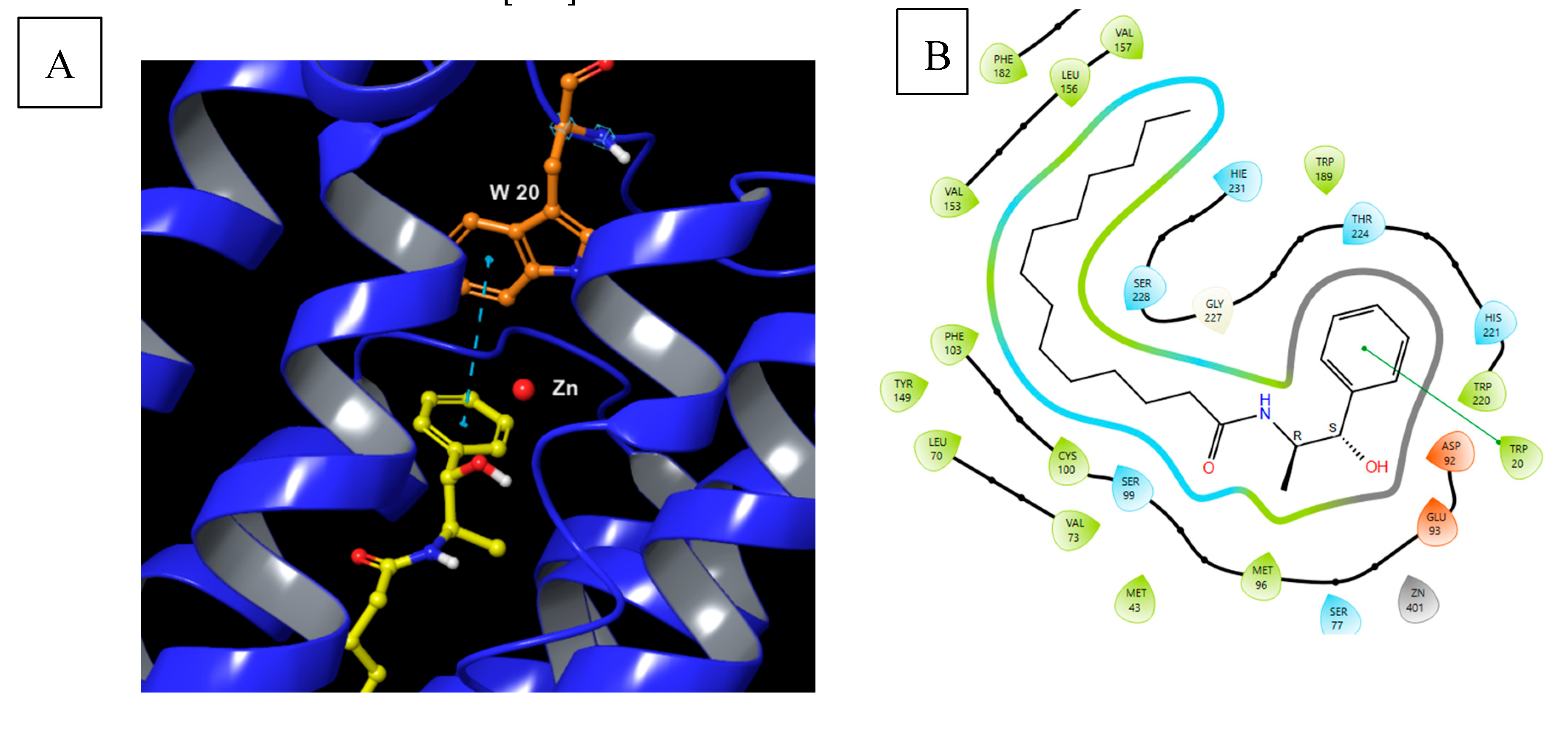

5.8.1. Pharmacological significance of d-erythro-MAPP

Various studies have demonstrated that D-e-MAPP is an inhibitor of alkaline ceramidase both in vitro and in cells [

164,

165]. It elevates endogenous ceramide levels with growth suppression and cell cycle arrest effects. D-e-MAPP has been used as an alkaline ceramidase inhibitor to perform detailed studies demonstrating the role of ceramidases in regulating the endogenous levels of ceramide [

162] [

164] [

165]. D-e-MAPP showed no interesting effects on other ceramide metabolism enzymes, including sphingomyelinase and glucocerebroside synthase. It is also ineffective against neutral and acidic ceramidases[

166].

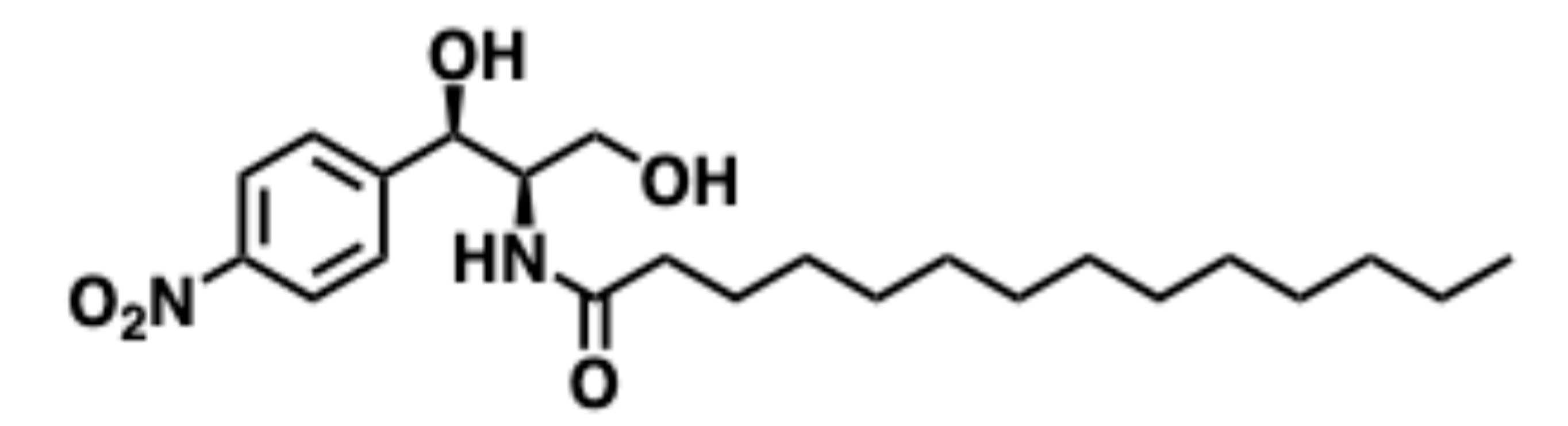

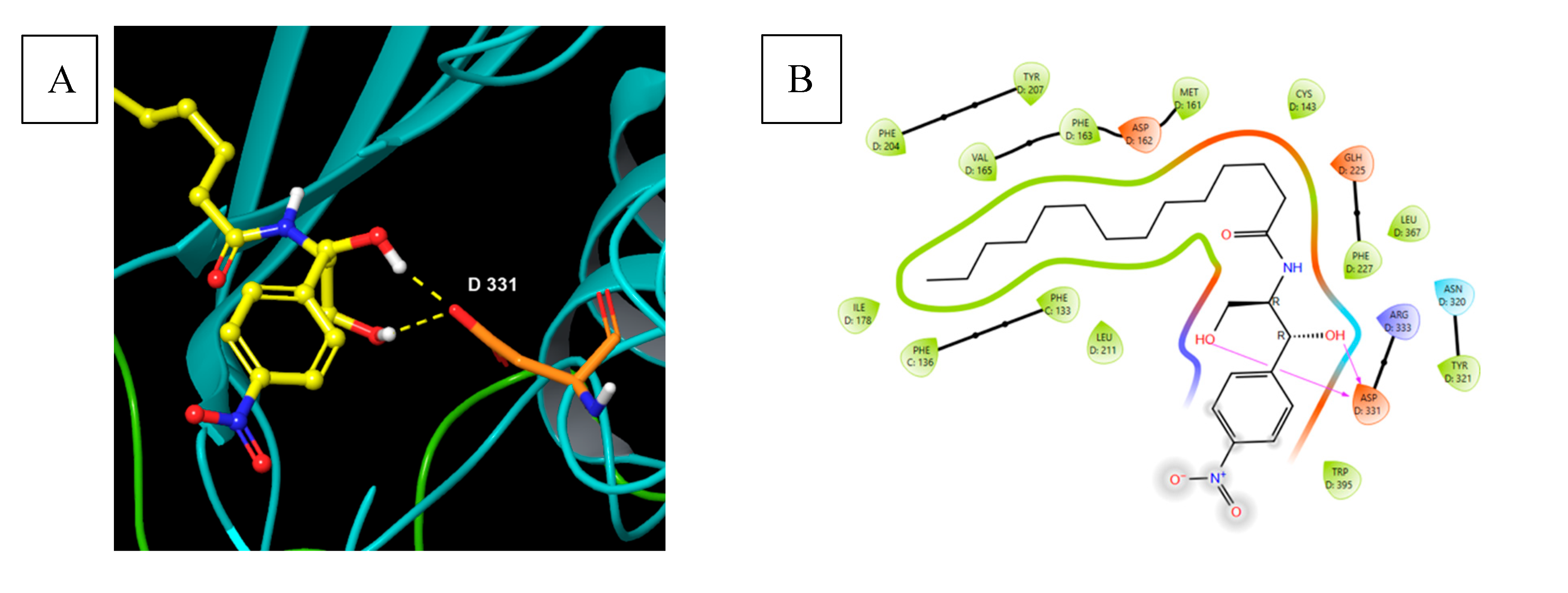

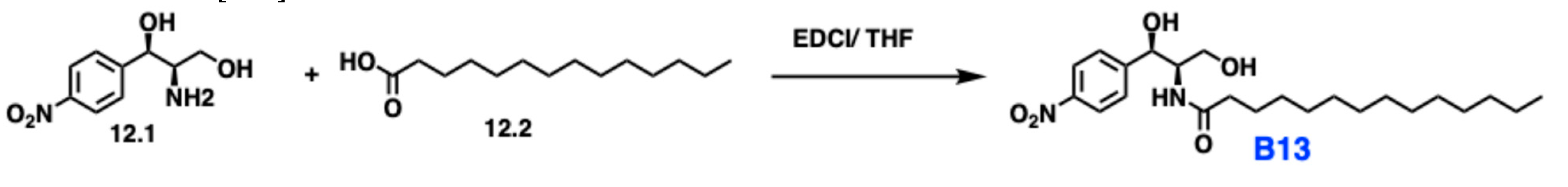

5.9. B13

B13 is a small molecule that targets ceramidases. It is synthesized by a simple amidation of tetradecanoic acid (12.2,

Scheme 12) and 2-amino-1-(4-nitrophenyl)propane-1,3-diol. B13 is a potent acid ceramidase inhibitor, with a primary target being the lysosomal acid ceramidase enzyme. This selectively inhibits the acidic form of acid ceramidase. B13 has also shown a minor effect on neutral ceramidase. B13 is being explored as an antiproliferative agent because it enhances ceramide levels in cancer cells [

167].

Figure 20.

Docked D-e-MAPP in human alkaline ceramidase in the active site with a metal atom Zinc. PDB ID: 6G7O protein is represented in blue color (A). The backbone amino acids are shown in orange. D-e-MAPP is represented in yellow. The metal ion zinc atom is shown in red color. The active site is located in close proximity to the zinc ion. (B) Two dimensional interactions of D-e-MAPP in the enzyme active site.

Figure 20.

Docked D-e-MAPP in human alkaline ceramidase in the active site with a metal atom Zinc. PDB ID: 6G7O protein is represented in blue color (A). The backbone amino acids are shown in orange. D-e-MAPP is represented in yellow. The metal ion zinc atom is shown in red color. The active site is located in close proximity to the zinc ion. (B) Two dimensional interactions of D-e-MAPP in the enzyme active site.

Figure 21.

B13 N-((1R,2R)-1,3-dihydroxy-1-(4-nitrophenyl)propan-2-yl)tetradecanamide.

Figure 21.

B13 N-((1R,2R)-1,3-dihydroxy-1-(4-nitrophenyl)propan-2-yl)tetradecanamide.

Figure 22.

(A) Binding of B13 or D-NAPPD to human acid ceramidase. PDB ID: 6MHM. Protein chains are green and blue. Backbone amino acids are shown in orange. B13 is yellow. The active site is located at the catalytic site of ceramide. Hydrogen bonding interaction was 1.8 to 2.3 Å. (B) Two dimensional interactions for B13 binding in the active site.

Figure 22.

(A) Binding of B13 or D-NAPPD to human acid ceramidase. PDB ID: 6MHM. Protein chains are green and blue. Backbone amino acids are shown in orange. B13 is yellow. The active site is located at the catalytic site of ceramide. Hydrogen bonding interaction was 1.8 to 2.3 Å. (B) Two dimensional interactions for B13 binding in the active site.

5.9.1. Pharmacological significance of B13

B13 prevents the aminolysis of ceramide to form sphingosine and a fatty acid by binding to the acid ceramidase enzyme's active site, resulting in ceramide-induced apoptosis [

168]. The close structural similarity with the substrate Cer makes it a suitable inhibitor targeting ceramidase. B13 was found to be highly potent

in vitro against various cancer cell lines but had challenges reaching the lysosomal compartment within the cells, potentially limiting its

in vivo efficacy. The molecular modeling studies discussed in Figure 22 depict the H-bond donor interaction of secondary and primary alcohol of B13 with Asp-331. The lipophilic tail is elongated and extends to form a U-shaped motif. A lysosomal formulation of B13 utilizing N, N-dimethylglycine (DMG) ester-modified prodrug (DMG-B13 prodrug) was synthesized to address drug delivery issues. DMG-B13 formulation facilitated its accumulation in acid lysosomes because of the basicity of the ionizable amine and resulted in a markedly improved cellular action [

167]. Notably, a one-step amidation can provide a pharmacological agent to perform pharmacological studies targeting ceramidase.

6. Discussion

Sphingolipids are key components of the lipid membrane. In preclinical studies, several molecules resembling the sphingolipids’ structural core add significance to targeting enzymes involved in sphingolipid biochemistry. The natural products and small molecules discussed in this review also highlighted the importance of the chiral pool strategy, especially utilizing amino acids and carbohydrate scaffolds. Most molecules have an inherent polar head group and a membrane-binding / lipophilic tail. Mammalian cellular sphingolipid biochemistry starts with L-Ser to afford Oxysphingolipids. Chiral pool strategy utilizing L, D, or unnatural amino acids can potentially enter the sphingolipid biosynthetic pathway. This can result in extensive SAR, probing the enzyme catalysis, and drug discovery. So far, very limited studies have been reported on bioconjugation chemistry to understand the trafficking of sphingolipids. An appropriate conjugation will provide insights into SL trafficking. It is not discussed in this review but fluorescent NBD-Sphingolipid derivatives were extensively used to understand the sphingolipid trafficking in cellular compartments. Utilizing these trafficking studies specific targeting of enzymes can be developed.

This focused review also identified the significance of compartmentalization at the cellular level and its effects in several disease states. Sphingolipid composition provides fluidity at the organ level, adding more complexity. The sphingolipid flux, localization, and compartmentalization interfere with cellular signaling. The expression of enzymes involved in sphingolipid biochemistry varies at tissue level. Studies involving the mRNA levels, bioinformatics targeting sphingolipid biochemistry will guide the early drug discovery efforts for hits identification. It is a fertile discipline towards learning the significance of compartmentalization and physicochemical properties of molecules bound to target membrane-bound enzymes. Incorporating drug delivery platforms early on will advance the therapeutic potential of hits identified.

Author Contributions

This research scholarship is dedicated to Professor Apurba Dutta and Dr. Dinah Dutta for their unwavering support and mentoring to synthetic and medicinal chemistry students. conceptualization- S.M., and S.P.; resources, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M., J.O., and S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.M., J.O., and S.P.; visualization, S.M., J.O., S.H., K.S., A.A.-H and S.P.; supervision, S.M., S.P.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by funds from Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, L.S. Skaggs College of Pharmacy, Idaho State University; the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy NIA award—2023; Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant #P20GM103408; The Institute for Modeling Collaboration and Innovation, University of Idaho, COBRE: P20GM104420 for chemdraw software.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yusuf Hannun for ceramide based cancer pharmacology discussion, Dr. Jared Barrott for pharmacogenomics discussions, and Dr. James K. Lai for pharmacology/toxicology discussions.

References

- Merrill, A.H., Jr.; Schmelz Em Fau - Dillehay, D.L.; Dillehay Dl Fau - Spiegel, S.; Spiegel S Fau - Shayman, J.A.; Shayman Ja Fau - Schroeder, J.J.; Schroeder Jj Fau - Riley, R.T.; Riley Rt Fau - Voss, K.A.; Voss Ka Fau - Wang, E.; Wang, E. Sphingolipids--the enigmatic lipid class: biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology.

- Schöffski, P.; Dumez, H.; Ruijter, R.; Miguel-Lillo, B.; Soto-Matos, A.; Alfaro, V.; Giaccone, G. Spisulosine (ES-285) given as a weekly three-hour intravenous infusion: results of a phase I dose-escalating study in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2011, 68, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogretmen, B. Sphingolipid metabolism in cancer signalling and therapy. (1474-1768 (Electronic)).

- Bouscary, A.; Quessada, C.; René, F.; Spedding, M.; Turner, B.J.; Henriques, A.; Ngo, S.T.; Loeffler, J.P. Sphingolipids metabolism alteration in the central nervous system: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and other neurodegenerative diseases.

- Gault, C.R.; Obeid, L.M.; Hannun, Y.A. An Overview of Sphingolipid Metabolism: From Synthesis to Breakdown. In Sphingolipids as Signaling and Regulatory Molecules, Chalfant, C., Poeta, M.D., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M. Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruett, S.T.; Bushnev, A.; Hagedorn, K.; Adiga, M.; Haynes, C.A.; Sullards, M.C.; Liotta, D.C.; Merrill, A.H., Jr. Biodiversity of sphingoid bases ("sphingosines") and related amino alcohols. J Lipid Res 2008, 49, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.; Myers, S.; McGowan, C.; Henstridge, D.; Eri, R.; Sonda, S.; Caruso, V. 1-Deoxysphingolipids, Early Predictors of Type 2 Diabetes, Compromise the Functionality of Skeletal Myoblasts. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 772925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ramírez, E.J.; García-Arribas, A.B.; Artetxe, I.; Shaw, W.A.; Goñi, F.M.; Alonso, A.; Jiménez-Rojo, N. (1-Deoxy)ceramides in bilayers containing sphingomyelin and cholesterol.

- Carreira, A.C.; Santos, T.C.; Lone, M.A.; Zupančič, E.; Lloyd-Evans, E.; de Almeida, R.F.M.; Hornemann, T.; Silva, L.C. Mammalian sphingoid bases: Biophysical, physiological and pathological properties. Progress in Lipid Research 2019, 75, 100988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, J.L.; Velazquez, F.N.; Obeid, L.M. Advances in determining signaling mechanisms of ceramide and role in disease. Journal of Lipid Research 2019, 60, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Corbacho, M.J.; Canals, D.; Adada, M.M.; Liu, M.; Senkal, C.E.; Yi, J.K.; Mao, C.; Luberto, C.; Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNFα)-induced Ceramide Generation via Ceramide Synthases Regulates Loss of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) and Programmed Cell Death *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 25356–25373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.D.; Maceyka, M.; Cowart, L.A.; Spiegel, S. Sphingolipids in metabolic disease: The good, the bad, and the unknown.

- Quinville, B.M.; Deschenes, N.M.; Ryckman, A.E.; Walia, J.S. A Comprehensive Review: Sphingolipid Metabolism and Implications of Disruption in Sphingolipid Homeostasis. LID - 10.3390/ijms22115793 [doi] LID - 5793.

- Foran, D.A.-O.; Antoniades, C.; Akoumianakis, I. Emerging Roles for Sphingolipids in Cardiometabolic Disease: A Rational Therapeutic Target? LID - 10.3390/nu16193296 [doi] LID - 3296.

- Šakić, Z.; Atić, A.A.-O.; Potočki, S.; Bašić-Jukić, N.A.-O. Sphingolipids and Chronic Kidney Disease. LID - 10.3390/jcm13175050 [doi] LID - 5050.

- Doll, C.A.-O.; Snider, A.A.-O. The diverse roles of sphingolipids in inflammatory bowel disease.

- Vona, R.; Iessi, E.; Matarrese, P. Role of Cholesterol and Lipid Rafts in Cancer Signaling: A Promising Therapeutic Opportunity? Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.; Bagatolli, L.A.; Volovyk, Z.N.; Thompson, N.L.; Levi, M.; Jacobson, K.; Gratton, E. Lipid Rafts Reconstituted in Model Membranes. Biophysical Journal 2001, 80, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitatani, K.; Idkowiak-Baldys, J.; Hannun, Y.A. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cellular Signalling 2008, 20, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandon, E.C.; Ehses I Fau - Rother, J.; Rother J Fau - van Echten, G.; van Echten G Fau - Sandhoff, K.; Sandhoff, K. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of serine palmitoyltransferase, 3-dehydrosphinganine reductase, and sphinganine N-acyltransferase in mouse liver.

- Moskot, M.; Bocheńska, K.; Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka, J.; Banecki, B.; Gabig-Cimińska, M. Abnormal Sphingolipid World in Inflammation Specific for Lysosomal Storage Diseases and Skin Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, D.K. Serine palmitoyltransferase: role in apoptotic de novo ceramide synthesis and other stress responses. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2002, 1585, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yard, B.A.; Carter, L.G.; Johnson, K.A.; Overton, I.M.; Dorward, M.; Liu, H.; McMahon, S.A.; Oke, M.; Puech, D.; Barton, G.J.; et al. The Structure of Serine Palmitoyltransferase; Gateway to Sphingolipid Biosynthesis. Journal of Molecular Biology 2007, 370, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemski Berry, K.A.-O.X.; Garfield, A.A.-O.; Jambal, P.; Zarini, S.A.-O.; Perreault, L.A.-O.; Bergman, B.A.-O. Oxidised phosphatidylcholine induces sarcolemmal ceramide accumulation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle.

- Tahia, F.; Ma, D.A.-O.; Stephenson, D.J.; Basu, S.K.; Del Mar, N.A.; Lenchik, N.; Kochat, H.; Brown, K.; Chalfant, C.A.-O.; Mandal, N.A.-O. Inhibiting De Novo Biosynthesis of Ceramide by L-Cycloserine Can Prevent Light-Induced Retinal Degeneration in Albino BALB/c Mice. LID - 13389 [pii] LID - 10.3390/ijms252413389 [doi].

- Hengst, J.A.; Ruiz-Velasco, V.J.; Raup-Konsavage, W.A.-O.; Vrana, K.A.-O.; Yun, J.A.-O. Cannabinoid-Induced Immunogenic Cell Death of Colorectal Cancer Cells Through De Novo Synthesis of Ceramide Is Partially Mediated by CB2 Receptor. LID - 10.3390/cancers16233973 [doi] LID - 3973.

- Jenkins, G.M.; Cowart, L.A.; Signorelli, P.; Pettus, B.J.; Chalfant, C.E.; Hannun, Y.A. Acute Activation of de Novo Sphingolipid Biosynthesis upon Heat Shock Causes an Accumulation of Ceramide and Subsequent Dephosphorylation of SR Proteins*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 42572–42578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamjoum, R.; Majumder, S.; Issleny, B.; Stiban, J. Mysterious sphingolipids: metabolic interrelationships at the center of pathophysiology. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1229108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurm, A.; Chlebowski, C.; Joseph, L.; Farmer, C.; Adedipe, D.; Weiss, M.; Wiggs, E.; Farhat, N.; Bianconi, S.; Berry-Kravis, E.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Characterization of Young Children Diagnosed with Niemann-Pick Disease, Type C1. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 2020, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.Y.; Linardic, C.; Obeid, L.; Hannun, Y. Identification of sphingomyelin turnover as an effector mechanism for the action of tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma-interferon. Specific role in cell differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Qi, B.; Yin, J.; Li, R.; Chen, X.; Hu, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Molecular basis for the catalytic mechanism of human neutral sphingomyelinases 1 (hSMPD2). Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiuk, S.; Hofmann K Fau - Nix, M.; Nix M Fau - Zumbansen, M.; Zumbansen M Fau - Stoffel, W.; Stoffel, W. Cloned mammalian neutral sphingomyelinase: functions in sphingolipid signaling?

- Monturiol-Gross, L.; Villalta-Romero, F.; Flores-Díaz, M.; Alape-Girón, A. Bacterial phospholipases C with dual activity: phosphatidylcholinesterase and sphingomyelinase. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 3262–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitatani, K.; Idkowiak-Baldys, J.; Hannun, Y.A. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cell Signal 2008, 20, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikman, B.T.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides as modulators of cellular and whole-body metabolism.

- Maceyka, M.; Spiegel, S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature 2014, 510, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaibaq, F.A.-O.; Dowdy, T.; Larion, M.A.-O. Targeting the Sphingolipid Rheostat in Gliomas. LID - 10.3390/ijms23169255 [doi] LID - 9255.

- Karmelić, I.; Jurilj Sajko, M.; Sajko, T.; Rotim, K.; Fabris, D. The role of sphingolipid rheostat in the adult-type diffuse glioma pathogenesis.

- Moro, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Koyama, Y.; Abe, S.; Uchida, H.; Naruse, K.; Obata, Y.; Tsuchida, J.; Toshikawa, C.; Ikarashi, M.; et al. Oral Administration of Glucosylceramide Suppresses Tumor Growth by Affecting the Ceramide/Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Balance in Breast Cancer Tissue.

- Piccoli, M.A.-O.; Cirillo, F.A.-O.; Ghiroldi, A.A.-O.; Rota, P.A.-O.; Coviello, S.; Tarantino, A.A.-O.X.; La Rocca, P.A.-O.; Lavota, I.; Creo, P.; Signorelli, P.A.-O.; et al. Sphingolipids and Atherosclerosis: The Dual Role of Ceramide and Sphingosine-1-Phosphate. LID - 10.3390/antiox12010143 [doi] LID - 143.

- Li, R.Z.; Wang, X.R.; Wang, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, X.X.; Pan, H.D.; Meng, W.Y.; Liang, T.L.; Li, J.X.; Yan, P.Y.; et al. The key role of sphingolipid metabolism in cancer: New therapeutic targets, diagnostic and prognostic values, and anti-tumor immunotherapy resistance. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 941643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajapeyee, N.; Beamon, T.C.; Gupta, R. Roles and therapeutic targeting of ceramide metabolism in cancer. Molecular Metabolism 2024, 83, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.L.; Lynch, K.R. Drugging sphingosine kinases.

- O'Brien, M.A.; Kirby, R. Apoptosis: A review of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic pathways and dysregulation in disease. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care 2008, 18, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, N.C.; Oskeritzian, C.A.; Paugh, S.W.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine kinases, sphingosine 1-phosphate, apoptosis and diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2006, 1758, 2016–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Vaena, S.G.; Thyagarajan, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Al-Khami, A.; Selvam, S.P.; Nguyen, H.; Kang, I.; Wyatt, M.W.; Baliga, U.; et al. Pro-Survival Lipid Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Metabolically Programs T Cells to Limit Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Reports 2019, 28, 1879–1893.e1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giussani, P.; Tringali, C.; Riboni, L.; Viani, P.; Venerando, B. Sphingolipids: Key Regulators of Apoptosis and Pivotal Players in Cancer Drug Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 4356–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brocklyn, J.R.; Williams, J.B. The control of the balance between ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate by sphingosine kinase: Oxidative stress and the seesaw of cell survival and death. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2012, 163, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, O.; Matute, J.; Gelineau-van Waes, J.; Maddox, J.R.; Gregory, S.G.; Ashley-Koch, A.E.; Showker, J.L.; Voss, K.A.; Riley, R.T. Human health implications from co-exposure to aflatoxins and fumonisins in maize-based foods in Latin America: Guatemala as a case study. World Mycotoxin Journal 2015, 8, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskouian, B.; Saba, J.D. Cancer Treatment Strategies Targeting Sphingolipid Metabolism. In Sphingolipids as Signaling and Regulatory Molecules, Chalfant, C., Poeta, M.D., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zaibaq, F.; Dowdy, T.; Larion, M. Targeting the Sphingolipid Rheostat in Gliomas. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Choi, K.M.; Choi, M.H.; Ji, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Sin, D.M.; Oh, K.W.; Lee, Y.M.; Hong, J.T.; Yun, Y.P.; et al. Serine palmitoyltransferase inhibitor myriocin induces growth inhibition of B16F10 melanoma cells through G2/M phase arrest. Cell Proliferation 2011, 44, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hada, N.; Katsume, A.; Kenichi, K.; Endo, C.; Horiba, N.; Sudoh, M. Novel oral SPT inhibitor CH5169356 inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in mouse models of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 2023, 11, e01094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahia, F.; Basu, S.K.; Prislovsky, A.; Mondal, K.; Ma, D.; Kochat, H.; Brown, K.; Stephenson, D.J.; Chalfant, C.E.; Mandal, N. Sphingolipid biosynthetic inhibitor L-Cycloserine prevents oxidative-stress-mediated death in an in vitro model of photoreceptor-derived 661W cells. Experimental Eye Research 2024, 242, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, T.; Albani, C.; Realini, N.; Migliore, M.; Basit, A.; Ottonello, G.; Cavalli, A. Inhibition of Serine Palmitoyltransferase by a Small Organic Molecule Promotes Neuronal Survival after Astrocyte Amyloid Beta 1–42 Injury. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2019, 10, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther, J.; Beattie, A.E.; Langridge-Smith, P.R.R.; Clarke, D.J.; Campopiano, D.J. l-Penicillamine is a mechanism-based inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase by forming a pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-thiazolidine adduct. MedChemComm 2012, 3, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, K.; Nishijima, M.; Fujita, T.; Kobayashi, S. Specificity of inhibitors of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), a key enzyme in sphingolipid biosynthesis, in intact cells: A novel evaluation system using an SPT-defective mammalian cell mutant. Biochemical Pharmacology 2000, 59, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Ji, C.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, W.; Ni, W.; Tong, X.; Wei, J.-F. Sphingosine kinase inhibitors: A patent review. Int J Mol Med 2018, 41, 2450–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Companioni, O.; Mir, C.; Garcia-Mayea, Y.; ME, L.L. Targeting Sphingolipids for Cancer Therapy.

- Adams, D.R.; Pyne, S.; Pyne, N.J. Structure-function analysis of lipid substrates and inhibitors of sphingosine kinases. Cellular Signalling 2020, 76, 109806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonica, J.; Clarke, C.J.; Obeid, L.M.; Luberto, C.; Hannun, Y.A. Upregulation of sphingosine kinase 1 in response to doxorubicin generates an angiogenic response via stabilization of Snail. The FASEB Journal 2023, 37, e22787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S.; Sauer, B.; Spika, I.; Schraut, C.; Kleuser, B.; Schäfer-Korting, M. Glucocorticoids mediate differential anti-apoptotic effects in human fibroblasts and keratinocytes via sphingosine-1-phosphate formation. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2004, 91, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Yokoyama, M.; Terasawa, K.; Ichinose, S.; Watanabe, A.; Podyma-Inoue, K.A.; Akiyoshi, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Yanagishita, M. Sphingosine kinase 2 inhibitor SG-12 induces apoptosis via phosphorylation by sphingosine kinase 2. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2013, 23, 2220–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, C.D.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Chin, S.H.; Shirai, K.; Ogretmen, B.; Bentz, T.A.; Brisendine, A.; Anderton, K.; Cusack, S.L.; Maines, L.W.; et al. A Phase I Study of ABC294640, a First-in-Class Sphingosine Kinase-2 Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 2017, 23, 4642–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Tang, X.; Li, T.; Chen, L.; He, H.; Wu, X.; Xiang, C.; Cao, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Therapeutic potential of the sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitor, PF-543. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 163, 114401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehin, M.; Melchior, M.; Welford, R.W.D.; Sidharta, P.N.; Dingemanse, J. Assessment of Target Engagement in a First-in-Human Trial with Sinbaglustat, an Iminosugar to Treat Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Clinical and Translational Science 2021, 14, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Deng, Y.; Yasgar, A.; Yadav, R.; Talley, D.; Zakharov, A.V.; Jain, S.; Rai, G.; Noinaj, N.; Simeonov, A.; et al. Venglustat Inhibits Protein N-Terminal Methyltransferase 1 in a Substrate-Competitive Manner. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 12334–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayman, J.A.; Lee, L.; Abe, A.; Shu, L. [38] Inhibitors of glucosylceramide synthase. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: 2000; Volume 311, pp. 373–387.

- Stocker, B.L.; Dangerfield, E.M.; Win-Mason, A.L.; Haslett, G.W.; Timmer, M.S.M. Recent Developments in the Synthesis of Pyrrolidine-Containing Iminosugars. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2010, 2010, 1615–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, W.; Sun, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, P.; Venkataramanan, R.; Yang, D.; Ma, X.; Rana, A.; Li, S. Novel glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor based prodrug copolymer micelles for delivery of anticancer agents. Journal of Controlled Release 2018, 288, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Seto, M.; Kakegawa, K.; Takami, K.; Kikuchi, F.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakamura, M.; Daini, M.; Murakami, M.; Ohashi, T.; et al. Discovery of Brain-Penetrant Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitors with a Novel Pharmacophore. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 4270–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.; Casas, J.; Llebaria, A.; Abad, J.L.; Fabriás, G. Chemical Tools to Investigate Sphingolipid Metabolism and Functions. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 580–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, J.M.; Ottenhoff, R.; Powlson, A.S.; Grefhorst, A.; van Eijk, M.; Dubbelhuis, P.F.; Aten, J.; Kuipers, F.; Serlie, M.J.; Wennekes, T.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of Glucosylceramide Synthase Enhances Insulin Sensitivity. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artola, M.; Kuo, C.-L.; Lelieveld, L.T.; Rowland, R.J.; van der Marel, G.A.; Codée, J.D.C.; Boot, R.G.; Davies, G.J.; Aerts, J.M.F.G.; Overkleeft, H.S. Functionalized Cyclophellitols Are Selective Glucocerebrosidase Inhibitors and Induce a Bona Fide Neuropathic Gaucher Model in Zebrafish. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019, 141, 4214–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, B.P.; Withers, S.G. Covalent inhibitors of glycosidases and their applications in biochemistry and biology. Glycobiology 2008, 18, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.-L.; Kallemeijn, W.W.; Lelieveld, L.T.; Mirzaian, M.; Zoutendijk, I.; Vardi, A.; Futerman, A.H.; Meijer, A.H.; Spaink, H.P.; Overkleeft, H.S.; et al. In vivo inactivation of glycosidases by conduritol B epoxide and cyclophellitol as revealed by activity-based protein profiling. The FEBS Journal 2019, 286, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Oyama, M.; Iwai, T.; Tanabe, M. Glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor ameliorates chronic inflammatory pain. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 156, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.A.; Yuyama, K.; Murai, Y.; Igarashi, Y.; Mikami, D.; Sivasothy, Y.; Awang, K.; Monde, K. Malabaricone C as Natural Sphingomyelin Synthase Inhibitor against Diet-Induced Obesity and Its Lipid Metabolism in Mice. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2019, 10, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, A.; Luberto, C.; Meier, P.; Bai, A.; Yang, X.; Hannun, Y.A.; Zhou, D. Sphingomyelin synthase as a potential target for D609-induced apoptosis in U937 human monocytic leukemia cells. Experimental Cell Research 2004, 292, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Lin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Lou, B.; Li, Y.; Dong, J.; Ding, T.; Jiang, X.; et al. Identification of small molecule sphingomyelin synthase inhibitors. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, B.; Dong, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, T.; Bi, T.; Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Ye, D.; Jiang, X.-C. Pharmacologic Inhibition of Sphingomyelin Synthase (SMS) Activity Reduces Apolipoprotein-B Secretion from Hepatocytes and Attenuates Endotoxin-Mediated Macrophage Inflammation. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavek, A.; Afrin, F.; Meldrum, T.; Pashikanti, S.; Barrott, J. Sphingomyelin synthase inhibition in sarcomas results in ceramide accumulation and apoptosis. The FASEB Journal 2019, 33, 471.416–471.416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JaffrÉZou, J.-P.; Bruno, A.P.; Moisand, A.; Levade, T.; Laurent, G.U.Y. Activation of a nuclear sphingomyelinase in radiation induced apoptosis. The FASEB Journal 2001, 15, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoi, H.; Maeda, S.; Shinohara, N.; Matsuyama, K.; Imamura, K.; Kawamura, I.; Nagano, S.; Setoguchi, T.; Yokouchi, M.; Ishidou, Y.; et al. Bone Morphogenic Protein (BMP) Signaling Up-regulates Neutral Sphingomyelinase 2 to Suppress Chondrocyte Maturation via the Akt Protein Signaling Pathway as a Negative Feedback Mechanism*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 8135–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keresztes, A.; Streicher, J.M. Synergistic interaction of the cannabinoid and death receptor systems – a potential target for future cancer therapies? FEBS Letters 2017, 591, 3235–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klutzny, S.; Lesche, R.; Keck, M.; Kaulfuss, S.; Schlicker, A.; Christian, S.; Sperl, C.; Neuhaus, R.; Mowat, J.; Steckel, M.; et al. Functional inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase by Fluphenazine triggers hypoxia-specific tumor cell death. Cell Death & Disease 2017, 8, e2709–e2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risner, M.L.; Ribeiro, M.; McGrady, N.R.; Kagitapalli, B.S.; Chamling, X.; Zack, D.J.; Calkins, D.J. Neutral sphingomyelinase inhibition promotes local and network degeneration in vitro and in vivo. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenz, C. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Acid Sphingomyelinase. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2010, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skácel, J.; Slusher, B.S.; Tsukamoto, T. Small Molecule Inhibitors Targeting Biosynthesis of Ceramide, the Central Hub of the Sphingolipid Network. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 64, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Yokota, W.; Katoh, T. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Scyphostatin, a Potent and Specific Inhibitor of Neutral Sphingomyelinase. Synthesis 2007, 2007, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Bai, A.; Beckham, T.H.; Marrison, S.T.; Yount, C.L.; Young, K.; Lu, P.; Bartlett, A.M.; Wu, B.X.; Keane, B.J.; et al. Radiation-induced acid ceramidase confers prostate cancer resistance and tumor relapse. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013, 123, 4344–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghandour, B.; Dbaibo, G.; Darwiche, N. The unfolding role of ceramide in coordinating retinoid-based cancer therapy. Biochemical Journal 2021, 478, 3621–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bawab, S.; Birbes, H.; Roddy, P.; Szulc, Z.M.; Bielawska, A.; Hannun, Y.A. Biochemical Characterization of the Reverse Activity of Rat Brain Ceramidase: A CoA-INDEPENDENT AND FUMONISIN B1-INSENSITIVE CERAMIDE SYNTHASE*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 16758–16766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J.M.; Xia, Z.; Smith, R.A.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, W.; Smith, C.D. Discovery and Evaluation of Inhibitors of Human Ceramidase. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2011, 10, 2052–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kus, G.; Kabadere, S.; Uyar, R.; Kutlu, H.M. Induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by the novel ceramidase inhibitor ceranib-2. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2015, 51, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saied, E.M.; Arenz, C. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Ceramidases. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2014, 34, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielawska, A.; Bielawski, J.; Szulc, Z.M.; Mayroo, N.; Liu, X.; Bai, A.; Elojeimy, S.; Rembiesa, B.; Pierce, J.; Norris, J.S.; et al. Novel analogs of d-e-MAPP and B13. Part 2: Signature effects on bioactive sphingolipids. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2008, 16, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saied, E.M.; Arenz, C. Inhibitors of Ceramidases. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2016, 197, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarocki, M.; Turek, K.; Saczko, J.; Tarek, M.; Kulbacka, J.A.-O. Lipids associated with autophagy: mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

- Ruzzi, F.; Cappello, C.; Semprini, M.S.; Scalambra, L.; Angelicola, S.; Pittino, O.M.; Landuzzi, L.; Palladini, A.; Nanni, P.; Lollini, P.L. Lipid rafts, caveolae, and epidermal growth factor receptor family: friends or foes?

- Jia, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Lin, W.; Cheng, B. Bioactive sphingolipids as emerging targets for signal transduction in cancer development.

- Lai, M.K.P.; Chew, W.S.; Torta, F.; Rao, A.; Harris, G.L.; Chun, J.; Herr, D.R. Biological Effects of Naturally Occurring Sphingolipids, Uncommon Variants, and Their Analogs. NeuroMolecular Medicine 2016, 18, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]