Submitted:

29 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

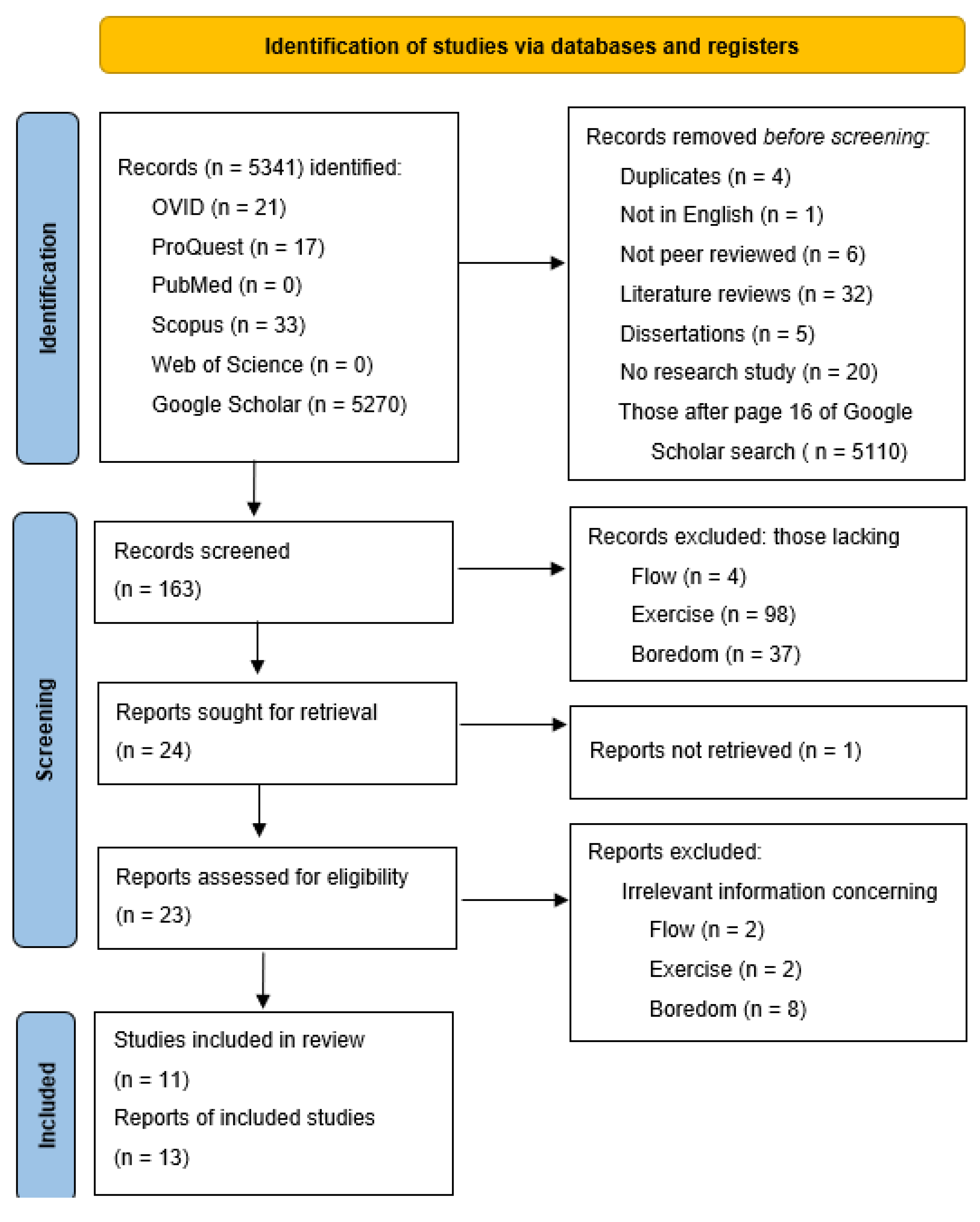

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Flow

3.2. Exercise

3.3. Boredom

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramar, K.; Malhotra, R.K.; Carden, K.A.; Martin, J.L.; Abbasi-Feinberg, F.; Aurora, R.N.; Kapur, V.K.; Olson, E.J.; Rosen, C.L.; Rowley, J.A.; et al. Sleep Is Essential to Health: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Position Statement. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2021, 17, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Dutil, C.; Featherstone, R.; Ross, R.; Giangregorio, L.; Saunders, T.J.; Janssen, I.; Poitras, V.J.; Kho, M.E.; Ross-White, A.; et al. Sleep Timing, Sleep Consistency, and Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, S232–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. Journal of Women’s Health 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Slopen, N.; Williams, D.R. Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Impacts of Racism on the Foundations of Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldursdottir, K.; McNamee, P.; Norton, E.; Asgeirsdóttir, T.L. Life Satisfaction and Body Mass Index: Estimating the Monetary Value of Achieving Optimal Body Weight; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, 2021; p. w2 8791.

- Gómez, C.A.; Kleinman, D.V.; Pronk, N.; Wrenn Gordon, G.L.; Ochiai, E.; Blakey, C.; Johnson, A.; Brewer, K.H. Addressing Health Equity and Social Determinants of Health Through Healthy People 2030. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 2021, 27, S249–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J. Addressing Socioeconomic Inequalities in Obesity: Democratising Access to Resources for Achieving and Maintaining a Healthy Weight. PLoS Med 2020, 17, e1003243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løvhaug, A.L.; Granheim, S.I.; Djojosoeparto, S.K.; Harrington, J.M.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Poelman, M.P.; Roos, G.; Sawyer, A.; Stronks, K.; Torheim, L.E.; et al. The Potential of Food Environment Policies to Reduce Socioeconomic Inequalities in Diets and to Improve Healthy Diets among Lower Socioeconomic Groups: An Umbrella Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, M.E.; Cohen, R.T.; Baldwin, C.M.; Johnson, D.A.; Palen, B.N.; Parthasarathy, S.; Patel, S.R.; Russell, M.; Tapia, I.E.; Williamson, A.A.; et al. Disparities in Sleep Health and Potential Intervention Models. Chest 2021, 159, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Loaisa, A.; Beltrán-Carrillo, V.J.; González-Cutre, D.; Jennings, G. Healthism and the Experiences of Social, Healthcare and Self-Stigma of Women with Higher-Weight. Soc Theory Health 2020, 18, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiker, N.R.W.; Astrup, A.; Hjorth, M.F.; Sjödin, A.; Pijls, L.; Markus, C.R. Does Stress Influence Sleep Patterns, Food Intake, Weight Gain, Abdominal Obesity and Weight Loss Interventions and Vice Versa? Obesity Reviews 2018, 19, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatriantafyllou, E.; Efthymiou, D.; Zoumbaneas, E.; Popescu, C.A.; Vassilopoulou, E. Sleep Deprivation: Effects on Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, V.J.; Fenton, M.H.; Mahoney, K.J. Self-Direction: A Revolution in Human Services; State University of New York Press: Albany, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4384-8344-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, T.J.M.; Dijkstra, A.; Kooy, A.; Dotinga, A.; Van Der Schans, C.P.; De Groot, M. The Role of Self-Regulation in the Effect of Self-Tracking of Physical Activity and Weight on BMI. J. technol. behav. sci. 2020, 5, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetty, S.; Collin, K. Self-Direction. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of the Possible; Glăveanu, V.P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-90912-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd, J.R.; Pesce, C.; Strafford, B.W.; Davids, K. Physical Literacy - A Journey of Individual Enrichment: An Ecological Dynamics Rationale for Enhancing Performance and Physical Activity in All. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Reports (1974-) 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Piggin, J. What Is Physical Activity? A Holistic Definition for Teachers, Researchers and Policy Makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasso, N.A. How Is Exercise Different from Physical Activity? A Concept Analysis: DASSO. Nurs Forum 2019, 54, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; O’ Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of Physical Inactivity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Meta-analyses. Scandinavian Med Sci Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Habit and Physical Activity: Theoretical Advances, Practical Implications, and Agenda for Future Research. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2019, 42, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staller, T.; Kirschke, C. Drive. In Personality Assessment with ID37; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-53920-7. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, F.; Power, S.; Waddell, A.; Birkett, S.; Duncan, M.; Harwood, A.; McGregor, G.; Rowley, N.; Broom, D. Is It Really Home-Based? A Commentary on the Necessity for Accurate Definitions across Exercise and Physical Activity Programmes. IJERPH 2021, 18, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Fernández-García, B.; Lehmann, H.I.; Li, G.; Kroemer, G.; López-Otín, C.; Xiao, J. Exercise Sustains the Hallmarks of Health. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2023, 12, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshears, J.; Lee, H.N.; Milkman, K.L.; Mislavsky, R.; Wisdom, J. Creating Exercise Habits Using Incentives: The Trade-off Between Flexibility and Routinization. Management Science 2021, 67, 4139–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, L.M.; Thomas, J.G.; Raynor, H.A.; Rhodes, R.E.; O’Leary, K.C.; Wing, R.R.; Bond, D.S. Relationship of Consistency in Timing of Exercise Performance and Exercise Levels Among Successful Weight Loss Maintainers. Obesity 2019, 27, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, B.R.; Murias, J.M.; Keir, D.A.; Weir, J.M. What Is Moderate to Vigorous Exercise Intensity? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 682233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, G.E.; Letieri, R.V.; Caldo-Silva, A.; Sardão, V.A.; Teixeira, A.M.; De Barros, M.P.; Vieira, R.P.; Bachi, A.L.L. Sustaining Efficient Immune Functions with Regular Physical Exercise in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond. Eur J Clin Investigation 2021, 51, e13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, C.; Torre, G.; Vasta, S.; Giombini, A.; Quaranta, F.; Papalia, R.; Pigozzi, F. Physical Exercise and Mental Health: The Routes of a Reciprocal Relation. IJERPH 2021, 18, 12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.; Jongenelis, M.I.; Jackson, B.; Newton, R.U.; Pettigrew, S. Factors Influencing Physical Activity Participation among Older People with Low Activity Levels. Ageing and Society 2020, 40, 2593–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, A.; Stearns, J.A.; Rhodes, R.E.; Hopkins, D.; Mummery, K.; Spence, J.C. Relationships Between Physical Activity, Boredom Proneness, and Subjective Well-Being Among U.K. Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 2022, 44, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bösselmann, V.; Amatriain-Fernández, S.; Gronwald, T.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E.; Machado, S.; Budde, H. Physical Activity, Boredom and Fear of COVID-19 Among Adolescents in Germany. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.; Fuentesal, J.; Conte, L.; Ortiz-Camacho, M.D.M.; Zamarripa, J. Satisfaction, Enjoyment and Boredom with Physical Education as Mediator between Autonomy Support and Academic Performance in Physical Education. IJERPH 2020, 17, 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feig, E.H.; Harnedy, L.E.; Golden, J.; Thorndike, A.N.; Huffman, J.C.; Psaros, C. A Qualitative Examination of Emotional Experiences During Physical Activity Post-Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 2022, 32, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsen, I.K.; Kayser, L.; Teglgaard Lyk–Jensen, H.; Rossen, S.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Midtgaard, J. “ <i>I Tried Forcing Myself to Do It, but Then It Becomes a Boring Chore”</i> : Understanding (Dis)Engagement in Physical Activity Among Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes Using a Practice Theory Approach. Qual Health Res 2022, 32, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieleke, M.; Wolff, W.; Keller, L. Getting Trapped in a Dead End? Trait Self-Control and Boredom Are Linked to Goal Adjustment. Motiv Emot 2022, 46, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Rosenbaum, S.; Lawrence, A.; Vella, S.A.; McEwan, D.; Ekkekakis, P. Updating Goal-Setting Theory in Physical Activity Promotion: A Critical Conceptual Review. Health Psychology Review 2021, 15, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgate, E.C.; Steidle, B. Lost by Definition: Why Boredom Matters for Psychology and Society. Social & Personality Psych 2020, 14, e12562. [CrossRef]

- Csíkszentmihályi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco (Calif.), 2000; ISBN 978-0-7879-5140-5. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen, B.A.K.; Oettingen, G. How Optimal Is the “Optimal Experience”? Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of the Relationship between Flow States, Attentional Performance, and Perceived Effort. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. [CrossRef]

- Zuzanek, J. Tribute to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1934–2021). Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 2022, 45, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhamdeh, S. On the Relationship Between Flow and Enjoyment. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer, C., Engeser, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-53467-7. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Play and Intrinsic Rewards. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 1975, 15, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning; Viking: New York, 2003; ISBN 978-0-670-03196-2. [Google Scholar]

- Heutte, J.; Fenouillet, F.; Martin-Krumm, C.; Gute, G.; Raes, A.; Gute, D.; Bachelet, R.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Optimal Experience in Adult Learning: Conception and Validation of the Flow in Education Scale (EduFlow-2). Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 828027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhamdeh, S. Investigating the “Flow” Experience: Key Conceptual and Operational Issues. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Developments and Trends in Flow Research Over 40 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis. Collabra: Psychology 2024, 10, 92948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; 1st ed.; HarperCollinsPublishers: New York, 1996; ISBN 978-0-06-017133-9. [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). PRISMA 2020 2024. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Smith, S.A.; Duncan, A.A. Systematic and Scoping Reviews: A Comparison and Overview. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 2022, 35, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, P.C.; Dargue, E.J.; Johnston, J.P.; Hawkins, R.M. Flow in Youth Sport, Physical Activity, and Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2021, 53, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, P.; Mackenzie, S.H.; Hodge, K. Flow States in Adventure Recreation: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2020, 46, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, S.G.; Stevens, C.J.; Jackman, P.C.; Swann, C. A Systematic Review of Flow Interventions in Sport and Exercise. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2023, 16, 657–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.J.; Allen, K.L.; Vine, S.J.; Wilson, M.R. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Flow States and Performance. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2023, 16, 693–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Research Synthesis Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to Overshadow Them All? Comparing the Sizes of 12 Academic Search Engines and Bibliographic Databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, P.; Figueiredo, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P. Does Exergaming Drive Future Physical Activity and Sport Intentions? J Health Psychol 2021, 26, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senecal, G. The Aftermath of Peak Experiences: Difficult Transitions for Contact Sport Athletes. The Humanistic Psychologist 2021, 49, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeder, J.D.; Postlewaite, E.L.; Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S.E. Construction and Validation of the Interest Development Scale. Motivation Science 2021, 7, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łucznik, K.; May, J.; Redding, E. A Qualitative Investigation of Flow Experience in Group Creativity. Research in Dance Education 2021, 22, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritikin, J.N.; Schmidt, K.M. Physical Activity Flow Propensity: Scale Development Using Exploratory Factor Analysis with Paired Comparison Indicators. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 2022, 7, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaç, E.; Tezcan, N. The Impact Of The Recreational Flow Experience On The Perception Of Wellness Among Individuals Engaged In Extreme Sports. Journal of Basic and Clinical Health Sciences 2024, 8, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Carr, A. ‘Living in the Moment’: Mountain Bikers’ Search for Flow. Annals of Leisure Research 2023, 26, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouelhi-Guizani, S.; Guinoubi, S.; Chtara, M.; Crespo, M. Relationships between Flow State and Motivation in Junior Elite Tennis Players: Differences by Gender. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 2023, 18, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialavori, S.; Bassi, M.; Delle Fave, A. Finding Flow in Pandemic Times: Leisure Opportunities for Optimal Experience and Positive Mental Health among Italian University Students. Journal of Leisure Research 2024, 55, 662–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weich, C.; Schüler, J.; Wolff, W. 24 Hours on the Run—Does Boredom Matter for Ultra-Endurance Athletes’ Crises? IJERPH 2022, 19, 6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, Y.; Zou, Z. The Role of Recreation Specialization and Self-Efficacy on Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Effect of Flow Experience. IJERPH 2022, 19, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panton, R.L. Incompressible Flow; Fifth edition.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2024; ISBN 978-1-119-98441-2. [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin, E.K.; Sabiston, C.M.; O’Rourke, R.H.; Bélanger, M.; Sylvestre, M.-P.; O’Loughlin, J.L. The Change in Exergaming From Before to During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Young Adults: Longitudinal Study. JMIR Serious Games 2023, 11, e41553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, T.; Dominski, F.H.; Marks, D.F. Human Needs in COVID-19 Isolation. J Health Psychol 2020, 25, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.H.; Houge Mackenzie, S. ‘I Don’t Want to Die. That’s Not Why I Do It at All’: Multifaceted Motivation, Psychological Health, and Personal Development in BASE Jumping. Annals of Leisure Research 2020, 23, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom; Bieleke, M. , Wolff, W., Martarelli, C.S., Eds.; Routledge international handbooks; Routledge: London New York, NY, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-327153-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, W.; Radtke, V.C.; Martarelli, C.S. Same Same but Different. In The Routledge International Handbook of Boredom; Routledge: London, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-327153-6. [Google Scholar]

- Elpidorou, A. The Bored Mind Is a Guiding Mind: Toward a Regulatory Theory of Boredom. Phenom Cogn Sci 2018, 17, 455–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Pagliaro, S.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Bonaiuto, M. Optimal Experience and Optimal Identity: A Multinational Study of the Associations Between Flow and Social Identity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, J.A.M.; Gimeno, E.C.; Coll, D.G.-C. Relationships among Goal Orientations, Motivational Climate and Flow in Adolescent Athletes: Differences by Gender. Span. J. Psychol. 2008, 11, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, O.; Ufer, M. Flow in Sports and Exercise: A Historical Overview. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer, C., Engeser, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-53467-7. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, T.M.S.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A General Model of Cognitive Bias in Human Judgment and Systematic Review Specific to Forensic Mental Health. Law and Human Behavior 2022, 46, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Title | Authors | Year |

| [62] | Does exergaming drive future physical activity and sport intentions? | Soltani, P; Figueiredo, P; Vilas-Boas, JP | 2021 |

| [63] | The Aftermath of Peak Experiences: Difficult Transitions for Contact Sport Athletes | Senecal, G | 2021 |

| [64] | Construction and Validation of the Interest Development Scale | Boeder, JD; Postlewaite, EL; Renninger, KA; Hidi, SE | 2021 |

| [65] | A qualitative investigation of flow experience in group creativity | Łucznik, K; May, J; Redding, E | 2021 |

| [66] | Physical Activity Flow Propensity: Scale Development using Exploratory Factor Analysis with Paired Comparison Indicators | Pritikin, JN; Schmidt, KM | 2022 |

| [67] | The Impact Of The Recreational Flow Experience On The Perception Of Wellness Among Individuals Engaged In Extreme Sports | Dilmaç, E; Tezcan, N | 2021 |

| [68] | 'Living in the moment': mountain bikers' search for flow | Taylor, S; Carr, A | 2023 |

| [69] | Relationships between flow state and motivation in junior elite tennis players: Differences by gender | Mouelhi-Guizani, S; Guinoubi, S; … | 2023 |

| [70] | Finding flow in pandemic times: Leisure opportunities for optimal experience and positive mental health among Italian university students | Mangialavori, S; Bassi, M … | 2024 |

| [71] | 24 hours on the Run—Does boredom matter for ultra-endurance Athletes' Crises? | Weich, C; Schüler, J; Wolff, W | 2022 |

| [72] | The role of recreation specialization and self-efficacy on life satisfaction: the mediating effect of flow experience | Röglin, L; Ketelhut, S; Ketelhut, K; Kircher E; … | 2021 |

| # | Aim | Participants | Date—Location |

| [62] | Examining how the usability and playability of sport exergames affects the future intentions of participation in physical activity or actual sport | 76 healthy university students | Date not reported, ethics approval January 2013—country not reported |

| [63] | Examine peak experiences in sport and how such experiences in an athletic career affect the athlete’s career transition | Nine semistructured interviews with former male team-contact sport athletes | Date not reported nor ethics approval information—USA |

| [64] | Assess adult interest as a variable that can develop | Three studies: 304 individuals, 484 respondents, 103 respondents | Dates not reported nor ethics approval information—USA |

| [65] | Investigating the role of flow experience in a group creativity task, contemporary dance improvisation | Six dancers | Date not reported nor ethics approval information—England |

| [66] | Investigating the flow propensity of physical activities | 987 participants | Date not reported nor ethics approval information—USA |

| [67] | Determine the impact of recreational flow experience on perceived wellness among extreme sports participants | 532 extreme sports participants |

Date not reported, ethics approval 10 March 2023—Turkey |

| [68] | Understanding if experienced mountain bikers actively search for flow experiences | 30 mountain bikers | Date not reported nor ethics approval information—New Zealand and England |

| [69] | Examine relationships between differing types of motivation and the flow state and possible gender differences | 94 junior elite tennis players | Experiences provided regarding the qualifying tournament for the Arabic Championships from 26 July 2019 to 3 August 2019— Tunisia |

| [70] | Flow-promoting activities during COVID-19—with specific attention to leisure—were investigated | 1281 Italian university students attending courses in Health Sciences and Humanities, Social and Political Sciences | 15 April 2020 and 15 May 2020—Italy |

| [71] | Examining the role of boredom in people who participate in ultra-endurance competitions | 113 competitors | 12 June 2021–13 June 2021—Germany |

| [72] | Examining the relationship between recreation specialization, self-efficacy, flow experience, and life satisfaction | 404 long-distance Chinese runners | 13 December to 21 December 2021—China |

| # | Flow | Exercise | Boredom |

| [62] | Associated with challenge and deep concentration, not enjoyment, in exergames | Exergames promote longer engagement times than traditional forms | With many of the movements in exergames repetitive, this is a possible result |

| [63] | A skills rise is proportionate to the increase in the challenge required to experience it for professionals | Promoted to ensure a continuation of flow experience following professional games | Without an increase in challenges, this is the result, proportionate to the decrease in flow |

| [64] | Concomitant with information seeking, motivation to reengage, persistence, self-regulation, and value | Effectiveness in promoting flow is determined by participant interest level | The Individual Interest Questionnaire predicts boredom, among other factors |

| [65] | Identified as a vital component of a dancer’s practice | Warm-up and team-building essential for flow | Require adequate challenge, otherwise experienced |

| [66] | Some activities offer more or less propensity for it— martial arts have the highest propensity | There must be interest and commitment to induce flow | Results when activity demands exceed skills or skills exceed demands |

| [67] | Found positively related to sports, exercise, and exceptional performance | When extreme or in excess can lead to anxiety, decreasing wellness perception | Negatively correlated with perceived wellness |

| [68] | Requires relatively smooth surfaces that allow and encourage the rider to achieve speed and momentum | Along with contemplation and nature experience, the most important motivations for bikers to achieve flow | Experienced most often when lacking challenge |

| [69] | Correlated with challenge/skill balance, action/awareness merging, unambiguous feedback, concentration on task, and sense of control with no significant gender differences | Should be modified to the tennis season and by gender | Produces a better quality of experience in tennis players than those in apathy or anxiety states as a psychological antecedent of flow |

| [70] | Possible during pandemic-related quarantine | Practiced within the limited spaces of city apartments | Resulted from inadaptive modifications in structure and contents of flow-promoting activities |

| [71] | Athletes can differ in their ability and frequency of exercise in this state | At a competitive level, reduced boredom with it, likely as a result of self-regulated regular training | Very extreme athletes report significantly lower sport-specific traits of this than other athletes |

| [72] | Those engaging in rewarding, specialized physical activities are more likely to experience it | There was an effect on the daily routines of runners by COVID-19 | Chinese runners become this with poor weather, injuries, or lack of a running partner |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).