Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Event

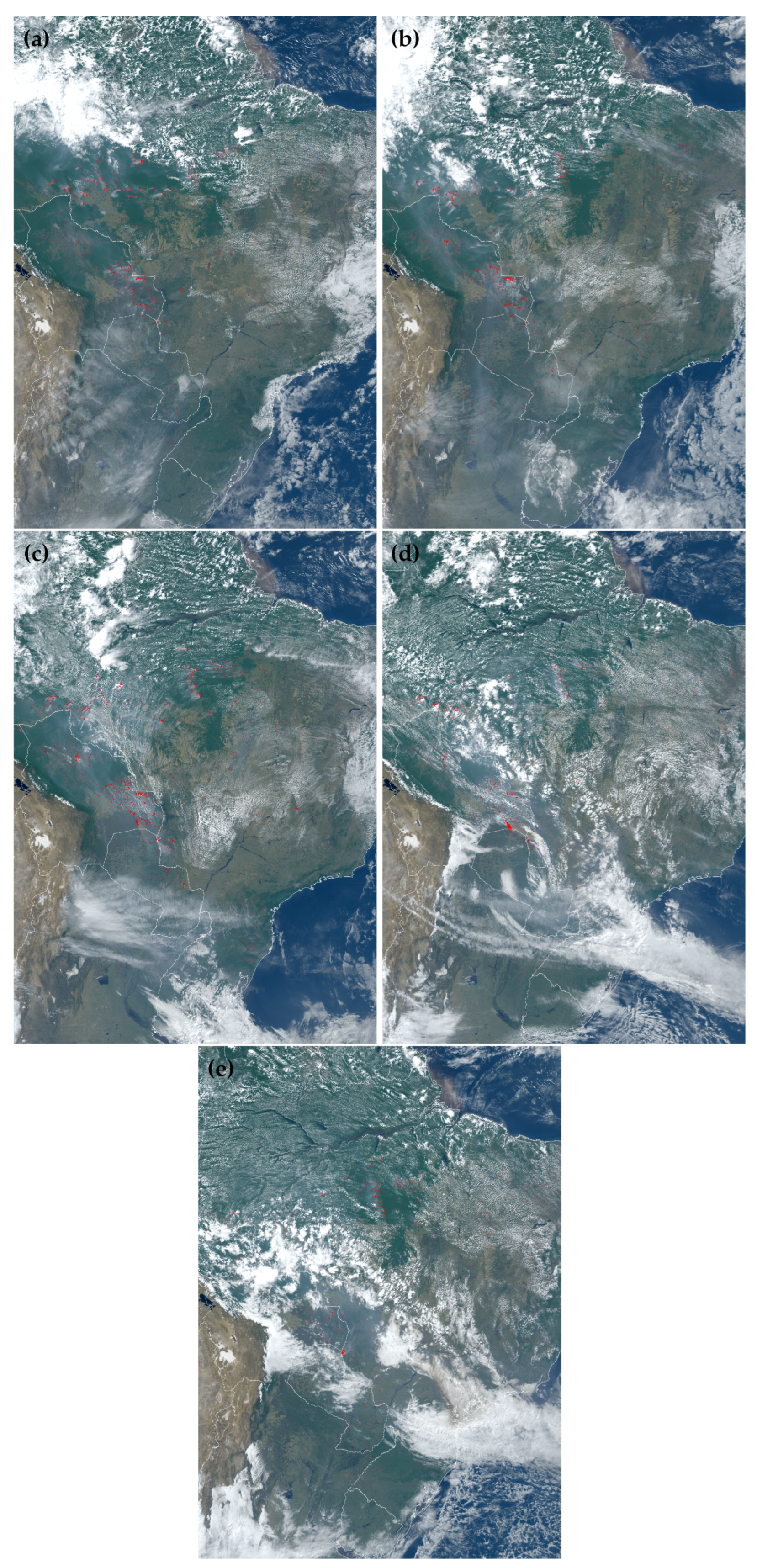

2.2. Description of the Event by Smoke from GOES-16 ABI

2.3. Model Set-Up

2.4. PBL Schemes

2.4.1. Model Modifications

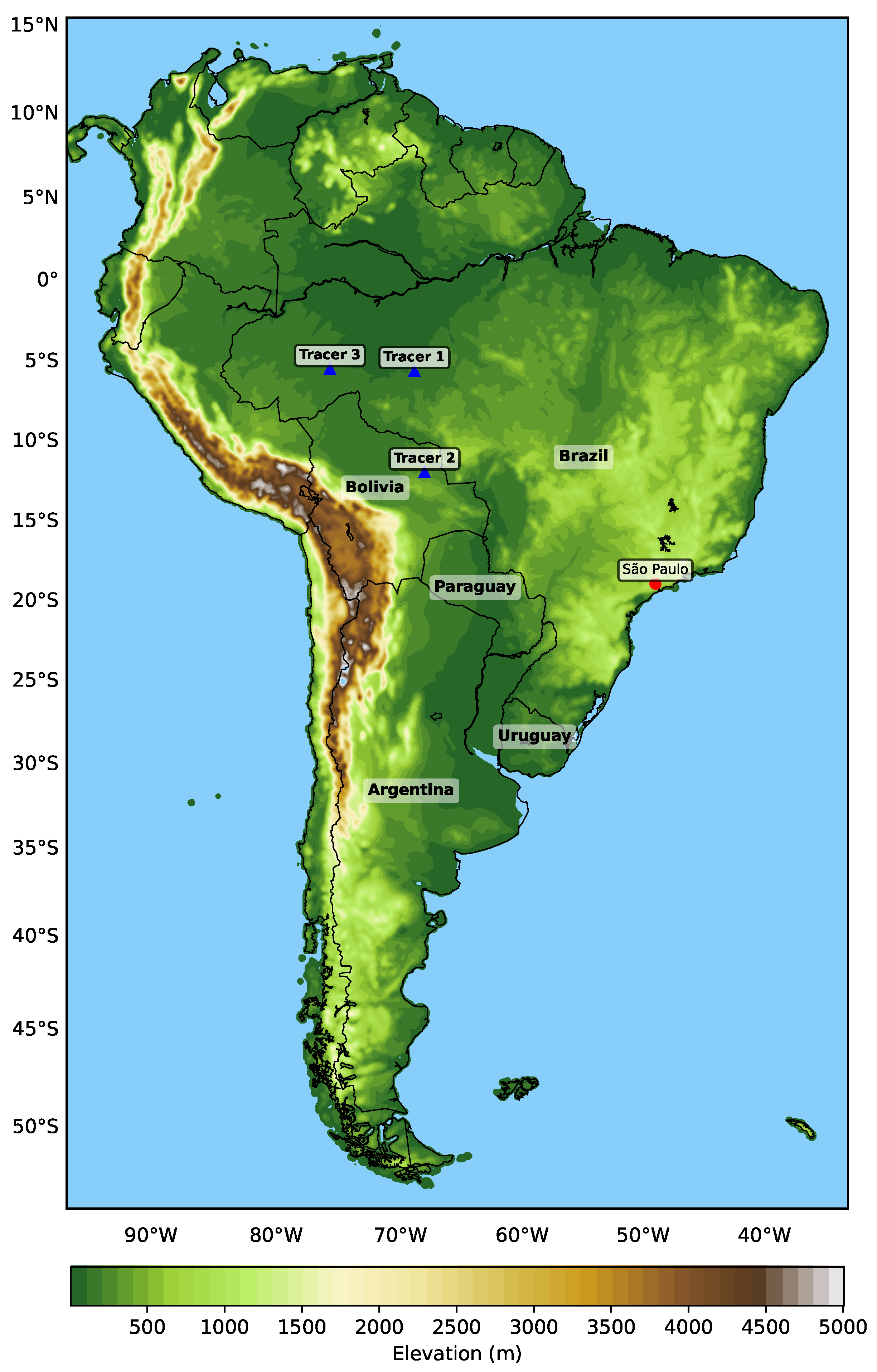

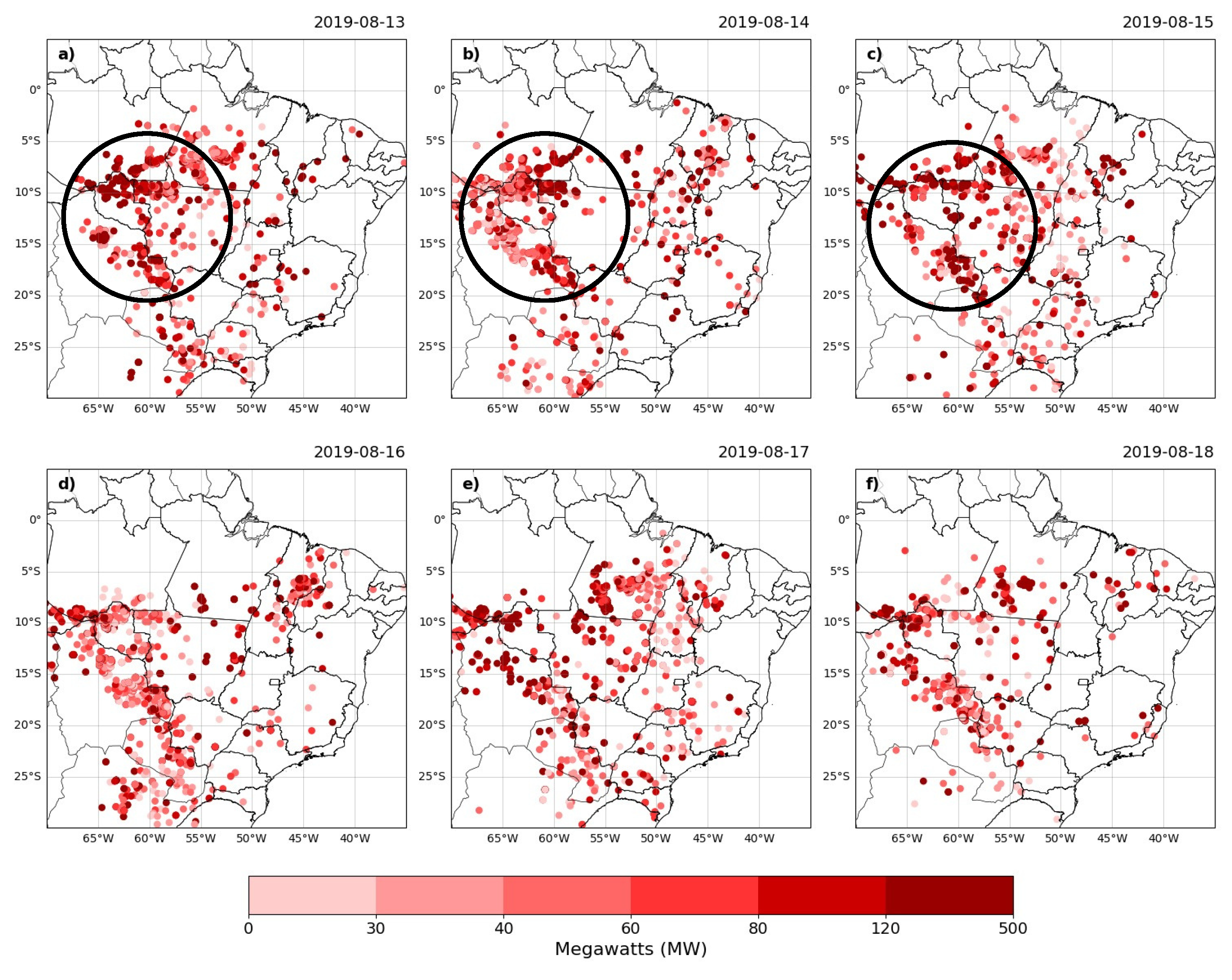

2.4.2. Passive Tracer’s Position Using FIRMS Data

| Tracer | Latitude (o) | Longitude (o) |

|---|---|---|

| tr17_t1 | -8.851 | -61.580 |

| tr17_t2 | -15.372 | -61.617 |

| tr17_t3 | -8.096 | -66.981 |

3. Results and Discussion

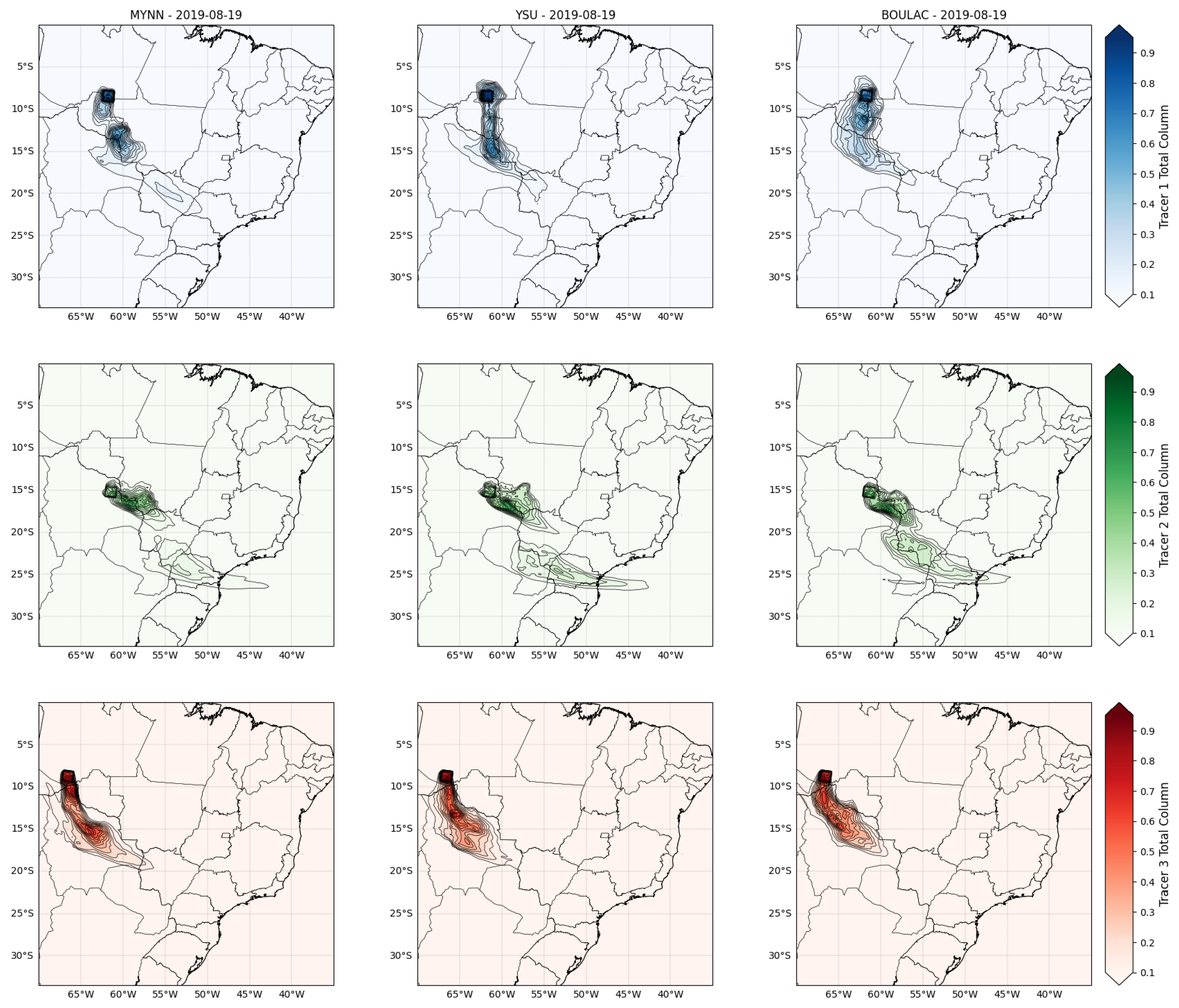

3.1. Daily Transport of Tracer’s

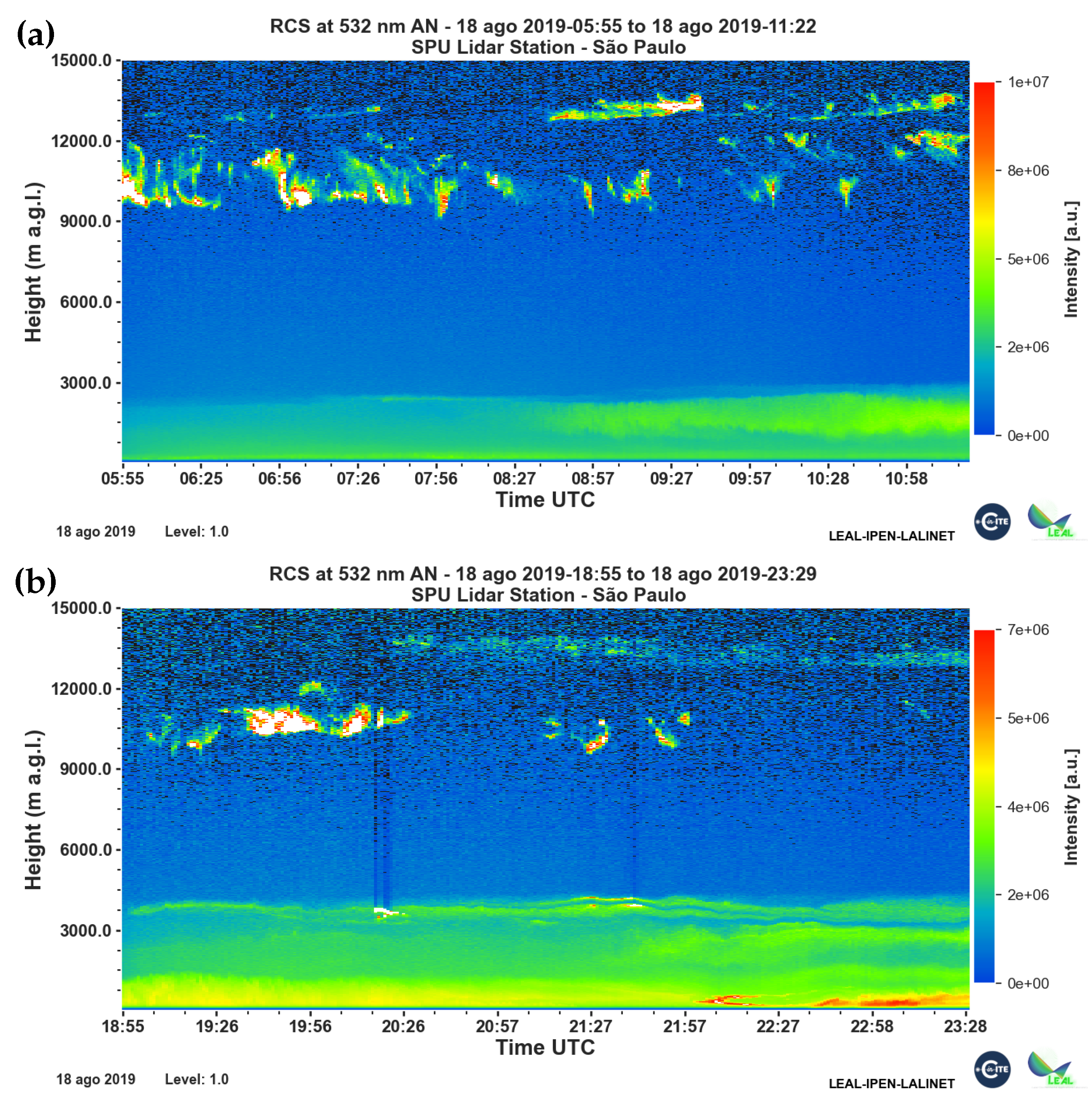

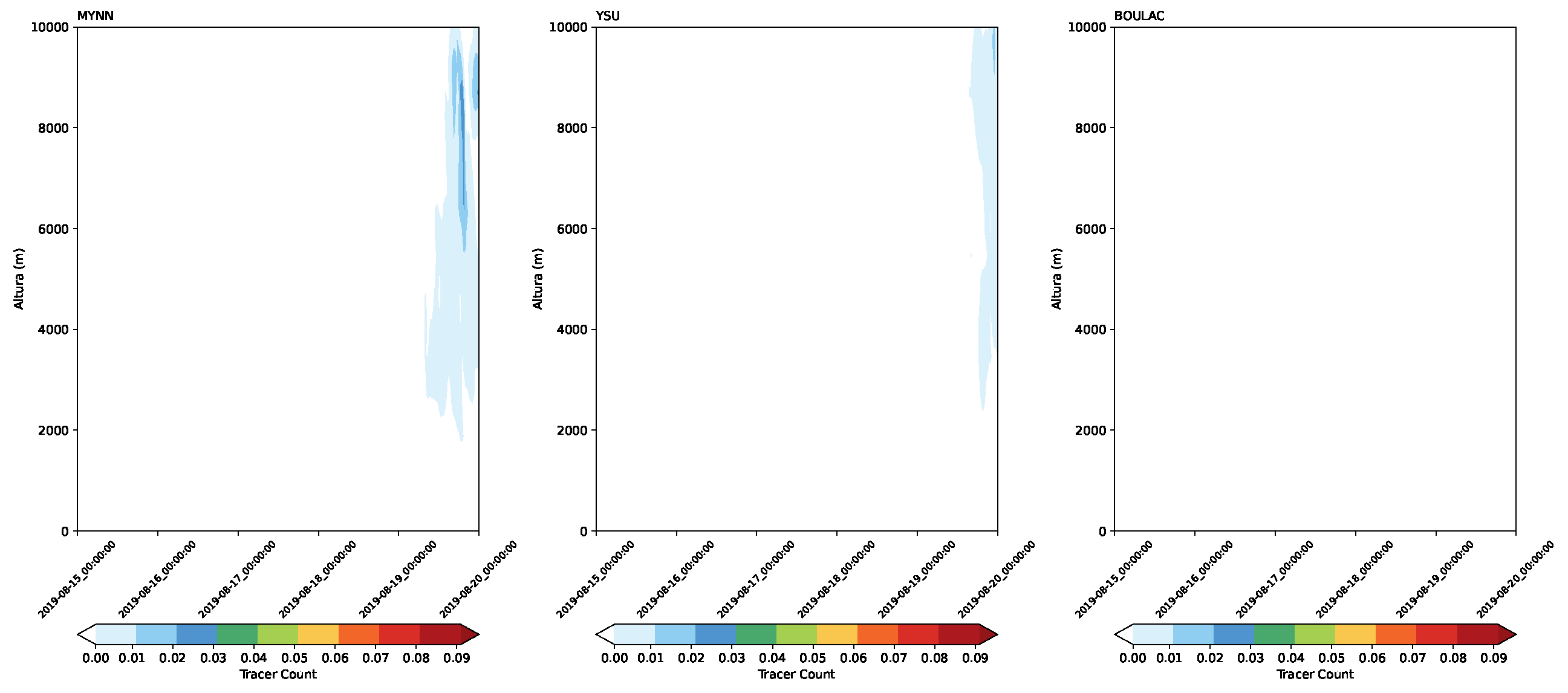

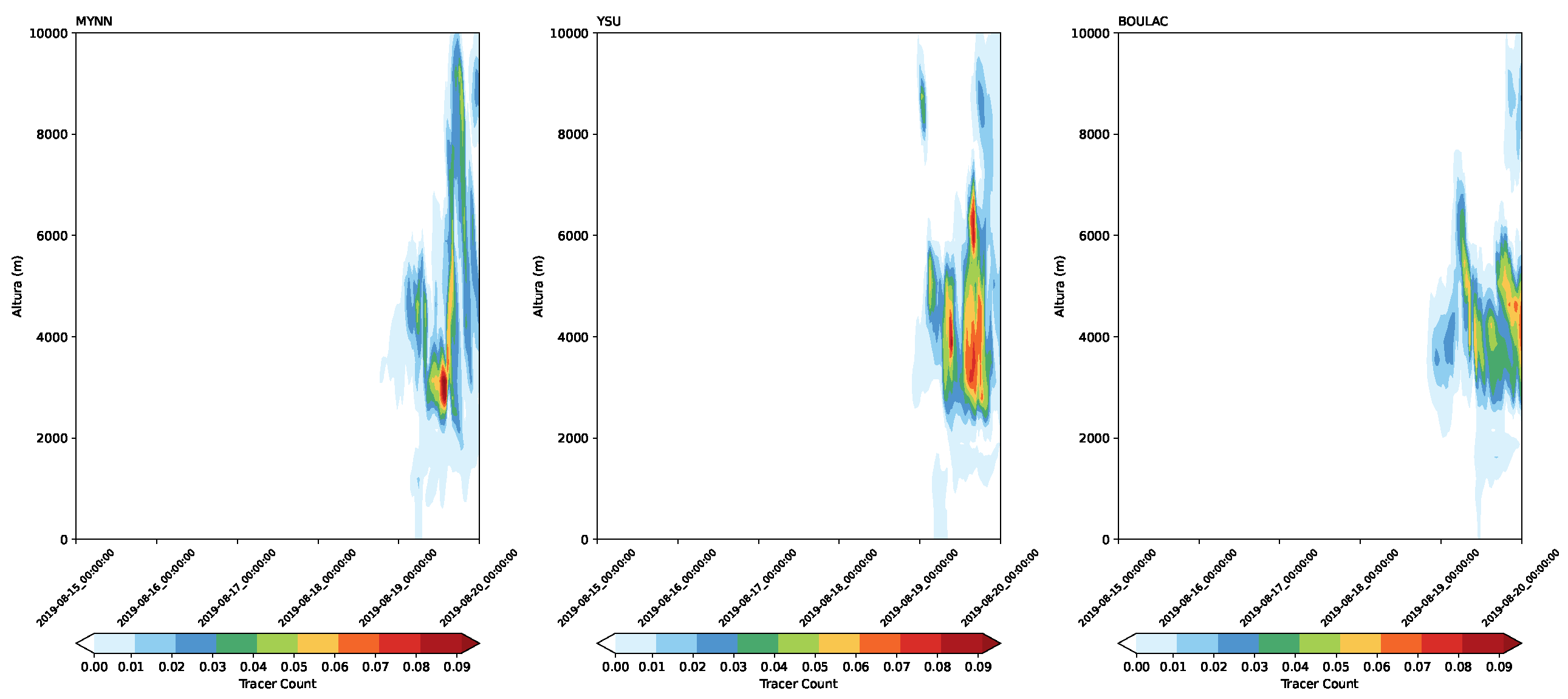

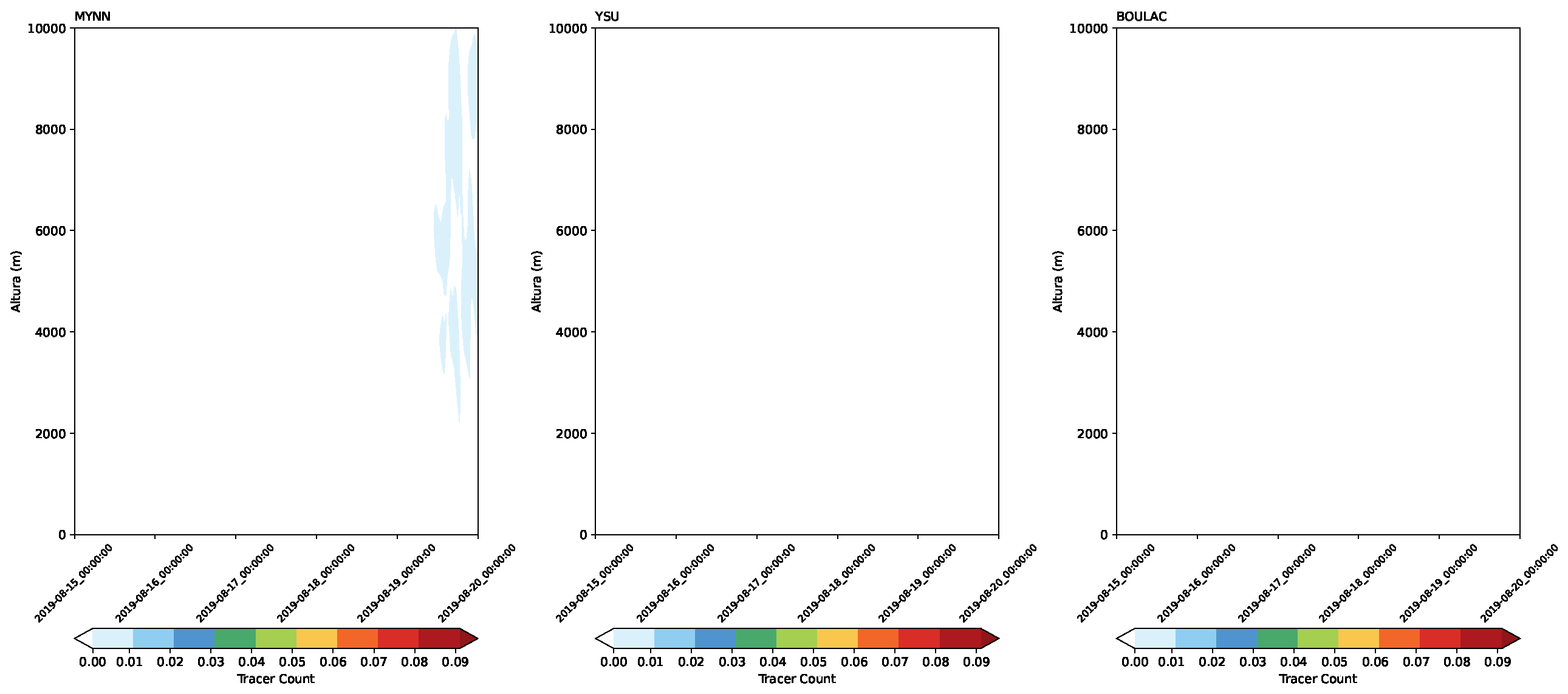

3.2. Time-Height Cross-Section Comparison with LiDAR Data

4. Conclusions

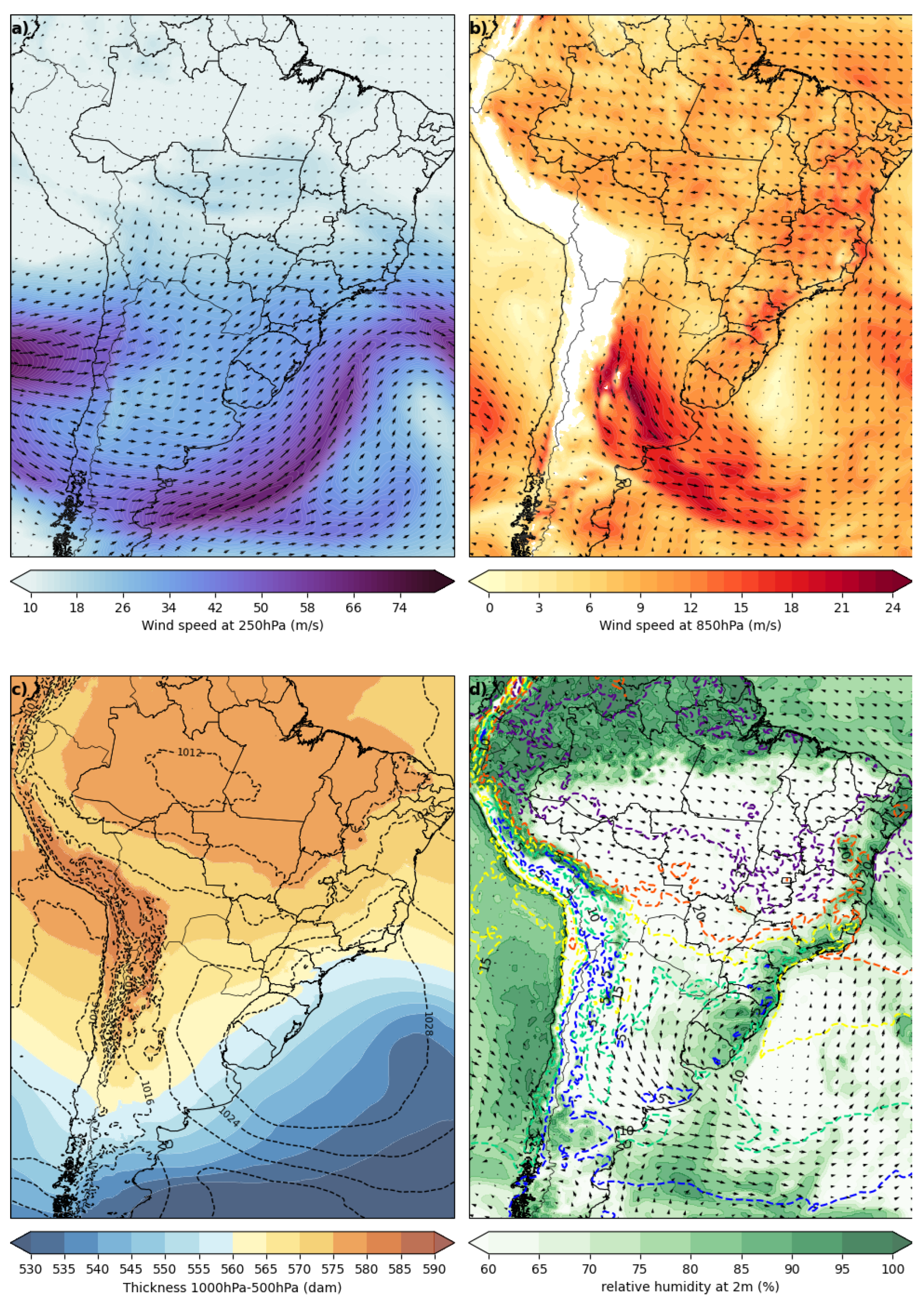

- Synoptic circulation was crucial in channeling particulates southward and then southeastward.

- Despite showing a delay compared to observations and the displacement of particulates to higher levels, the WRF model simulations generally provided a good representation of particulate transport across the region.

- The MYNN planetary boundary layer (PBL) scheme yielded the best results, with tr17_t2 reaching the region of interest with a significantly strong signal compared to observations.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Sypnotic Conditions During the Event

Appendix A.2. Daily Transport of Tracer’s

References

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, C.E.; Stone, P.H.; Sokolov, A.P.; Allen, M.R.; Webster, M.D. Quantifying uncertainties in climate system properties with the use of recent climate observations. science 2002, 295, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RamanathanV, C.; et al. Atmosphere aerosols, climate, andthehydrologicalcycle. Science 2001, 294, 2119r2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickl, T.; Giehl, H.; Jäger, H.; Vogelmann, H. 35 yr of stratospheric aerosol measurements at Garmisch-Partenkirchen: from Fuego to Eyjafjallajökull, and beyond. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2013, 13, 5205–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencherif, H.; Bègue, N.; Kirsch Pinheiro, D.; Du Preez, D.J.; Cadet, J.M.; da Silva Lopes, F.J.; Shikwambana, L.; Landulfo, E.; Vescovini, T.; Labuschagne, C.; et al. Investigating the Long-Range Transport of Aerosol Plumes Following the Amazon Fires (August 2019): A Multi-Instrumental Approach from Ground-Based and Satellite Observations. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemes, M.; Reboita, M.S.; Capucin, B.C. Impactos das queimadas na Amazônia no tempo em São Paulo na tarde do dia 19 de agosto de 2019. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Física 2020, 13, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima de Bem, D.; Anabor, V.; Dornelles Bittencourt, G.; Kirsch Pinheiro, D.; Scremin Puhales, F.; Bencherif, H.; Bègue, N.; Angelo Steffenel, L. Análise das condições sinóticas durante os incêndios florestais na Amazônia e seu impacto na cidade de São Paulo em 19 de agosto de 2019. Revista Ciência e Natura 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus. Observer: Monitoring fire emissions and mitigating global impacts with CAMS. https://www.copernicus.eu/en/news/news/observer-monitoring-fire-emissions-and-mitigating-global-impacts-cams. [Online; acessado em 28-fev-2025].

- Barbosa, H.A.; Buriti, C.O.; Kumar, T.V.L. Assessment of Fire Dynamics in the Amazon Basin Through Satellite Data. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R. An introduction to boundary layer meteorology; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, 1988; p. 666.

- Reid, J.; Koppmann, R.; Eck, T.; Eleuterio, D. A review of biomass burning emissions part II: intensive physical properties of biomass burning particles. Atmospheric chemistry and physics 2005, 5, 799–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.F.; Hudson, J.G.; Zielinska, B.; Tanner, R.L.; Hallett, J.; Watson, J.G. Cloud condensation nuclei from biomass burning 1991.

- Malavelle, F.F.; Haywood, J.M.; Mercado, L.M.; Folberth, G.A.; Bellouin, N.; Sitch, S.; Artaxo, P. Studying the impact of biomass burning aerosol radiative and climate effects on the Amazon rainforest productivity with an Earth system model. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2019, 19, 1301–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, F.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Rosenfeld, D.; Ding, Y. Long-term impacts of aerosols on the vertical development of clouds and precipitation. Nature Geoscience 2011, 4, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.K.; Chen, J.P.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C. Impact of aerosols on convective clouds and precipitation. Reviews of Geophysics 2012, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, W.P.; Purdom, J.F. Introducing GOES-I: The first of a new generation of geostationary operational environmental satellites. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 1994, 75, 757–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmit, T.J.; Gunshor, M.M.; Menzel, W.P.; Gurka, J.J.; Li, J.; Bachmeier, A.S. Introducing the next-generation Advanced Baseline Imager on GOES-R. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2005, 86, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C. Monitoring fires with the GOES-R series. In The GOES-R Series; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 145–163.

- Roberts, G.J.; Wooster, M.J. Fire detection and fire characterization over Africa using Meteosat SEVIRI. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2008, 46, 1200–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Schroeder, W.; Rishmawi, K.; Wooster, M.; Schmidt, C.; Huang, C.; Csiszar, I.; Giglio, L. Geostationary active fire products validation: GOES-17 ABI, GOES-16 ABI, and Himawari AHI. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 44, 3174–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.V.; Zhang, R.; Schroeder, W.; Huang, C.; Giglio, L. Validation of GOES-16 ABI and MSG SEVIRI active fire products. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 83, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Schmit, T. GOES-16 ABI level 1b and cloud and moisture imagery (CMI) release full validation data quality. Nat. Centers Environ. Inf.(NCEI), College Park, MD, USA, Tech. Rep 2019, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C.; Hoffman, J.; Prins, E.; Lindstrom, S. GOES-R advanced baseline imager (ABI) algorithm theoretical basis document for fire/hot spot characterization, version 2.0, NOAA, Silver Spring, Md, 2010.

- William C Skamarock, Joseph B, J.D.; et al. Weather Forecast and Research Model, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C3S. ERA5, 2017.

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2008, 113, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.A.; Dudhia, J.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Montávez, J.P.; García-Bustamante, E. A Revised Scheme for the WRF Surface Layer Formulation. Monthly weather review 2012, 140, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Freitas, S.R. A scale and aerosol aware stochastic convective parameterization for weather and air quality modeling. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2014, 14, 5233–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.Y.; Lim, J.O.J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). Asia-Pacific Journal of Atmospheric Sciences 2006, 42, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, M.; Niino, H. Development of an improved turbulence closure model for the atmospheric boundary layer. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. Ser. II 2009, 87, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjić, Z.I. The step-mountain eta coordinate model: Further developments of the convection, viscous sublayer, and turbulence closure schemes. Monthly weather review 1994, 122, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesinger, F. Forecasting upper tropospheric turbulence within the framework of the Mellor-Yamada 2.5 closure. Research activities in atmospheric and oceanic modeling. Technical report, WMO/CAS/JSC WGNE Tech. Rep. 18, 1993.

- Bougeault, P.; Lacarrere, P. Parameterization of orography-induced turbulence in a mesobeta–scale model. Monthly weather review 1989, 117, 1872–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.Y.; Lim, J.O.J. The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). Asia-Pacific Journal of Atmospheric Sciences 2006, 42, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.Y.; Pan, H.L. Nonlocal boundary layer vertical diffusion in a medium-range forecast model. Monthly weather review 1996, 124, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffman, P. On the effect of the molecular diffusivity in turbulent diffusion. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1960, 8, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuki, S.M.; Mannaerts, C.M.; Su, Z. Influence of Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) Parameterizations in the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model on the retrieval of surface meteorological variables over the Kenyan Highlands. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunwani, P.; Govardhan, G.; Jena, C.; Yadav, P.; Kulkarni, S.; Debnath, S.; Pawar, P.V.; Khare, M.; Kaginalkar, A.; Kumar, R.; et al. Sensitivity of WRF/Chem simulated PM2. 5 to initial/boundary conditions and planetary boundary layer parameterization schemes over the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaylock, B.K.; Horel, J.D.; Crosman, E.T. Impact of lake breezes on summer ozone concentrations in the Salt Lake valley. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2017, 56, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimireddy, S.R.; Bhaganagar, K. Short-term passive tracer plume dispersion in convective boundary layer using a high-resolution WRF-ARW model. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2018, 9, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Gordon, M.; Chen, Y. Passive-tracer modelling at super-resolution with Weather Research and Forecasting–Advanced Research WRF (WRF-ARW) to assess mass-balance schemes. Geoscientific Model Development 2023, 16, 5069–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Easter, R.C.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Jimenez, J.L.; Fast, J.D.; Ghan, S.J.; Wang, H.; Berg, L.K.; Barth, M.C.; Liu, Y.; et al. Aerosol transport and wet scavenging in deep convective clouds: A case study and model evaluation using a multiple passive tracer analysis approach. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2015, 120, 8448–8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimireddy, S.R.; Bhaganagar, K. Performance assessment of dynamic downscaling of WRF to simulate convective conditions during sagebrush phase 1 tracer experiments. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saide, P.E.; Carmichael, G.R.; Spak, S.N.; Gallardo, L.; Osses, A.E.; Mena-Carrasco, M.A.; Pagowski, M. Forecasting urban PM10 and PM2. 5 pollution episodes in very stable nocturnal conditions and complex terrain using WRF–Chem CO tracer model. Atmospheric Environment 2011, 45, 2769–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.; Ederer, G.; Olsina, O.; Wong, M.; Cechini, M.; Boller, R. NASA’s fire information for resource management system (FIRMS): Near real-time global fire monitoring using data from MODIS and VIIRS. In Proceedings of the EARSel Forest Fires SIG Workshop, 2019, number GSFC-E-DAA-TN73770.

- Olsina, O.; Hewson, J.; Davies, D.; Radov, A.; Quayle, B.; Giglio, L.; Hall, J. NASA’s FIRMS: Enabling the Use of Earth System Science Data for Wildfire Management. Technical report, Copernicus Meetings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chauvigné, A.; Aliaga, D.; Sellegri, K.; Montoux, N.; Krejci, R.; Močnik, G.; Moreno, I.; Müller, T.; Pandolfi, M.; Velarde, F.; et al. Biomass burning and urban emission impacts in the Andes Cordillera region based on in situ measurements from the Chacaltaya observatory, Bolivia (5240 m asl). Atmospheric chemistry and physics 2019, 19, 14805–14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, M.; Miura, M.; Xiao, Y. Influence of biomass burning on local air pollution in mainland Southeast Asia from 2001 to 2016. Environmental Pollution 2019, 254, 112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.; Eck, T.; Holben, B.; Artaxo, P.; Yamasoe, M.A.; Procopio, A. Observed reductions of total solar irradiance by biomass-burning aerosols in the Brazilian Amazon and Zambian Savanna. Geophysical Research Letters 2002, 29, 4–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landulfo, E.; Papayannis, A.; Artaxo, P.; Castanho, A.; De Freitas, A.; Souza, R.; Vieira, N.; Jorge, M.; Sánchez-Ccoyllo, O.; Moreira, D. Synergetic measurements of aerosols over São Paulo, Brazil using LIDAR, sunphotometer and satellite data during the dry season. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2003, 3, 1523–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Silva, J.; Antuña Marrero, J.; Taha, G.; Landulfo, E. Synergetic Aerosol Layer Observation After the 2015 Calbuco Volcanic Eruption Event, Remote Sens., 11, 195, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Stensrud, D.J. Importance of low-level jets to climate: A review. Journal of Climate 1996, pp. 1698–1711. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/26201369.

- Vera, C.; Baez, J.; Douglas, M.; Emmanuel, C.; Marengo, J.; Meitin, J.; Nicolini, M.; Nogues-Paegle, J.; Paegle, J.; Penalba, O.; et al. The South American low-level jet experiment. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2006, 87, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abish, B.; Joseph, P.; Johannessen, O.M. Climate change in the subtropical jetstream during 1950–2009. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 2015, 32, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).