Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

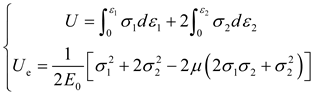

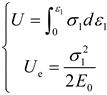

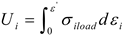

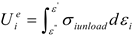

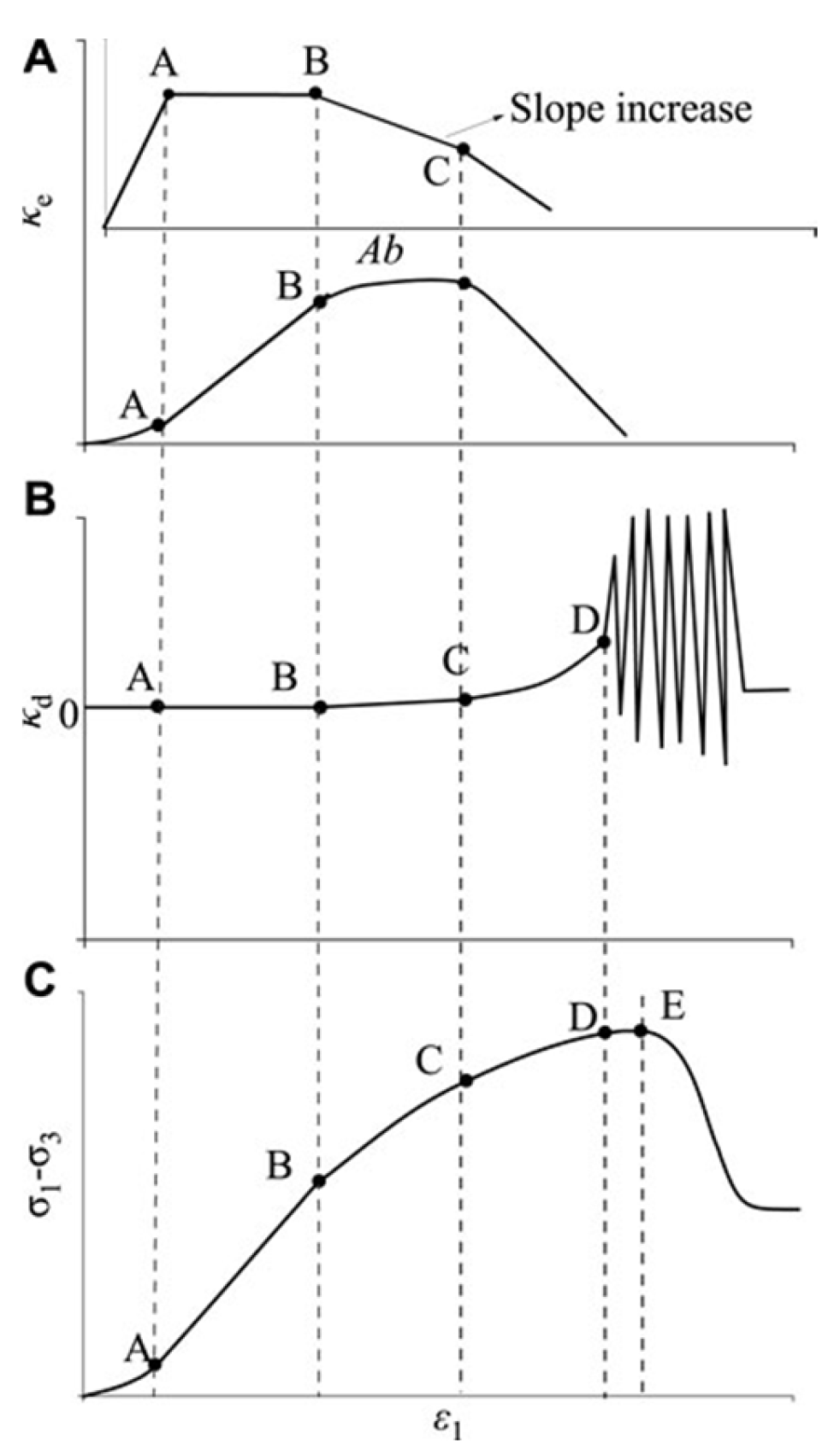

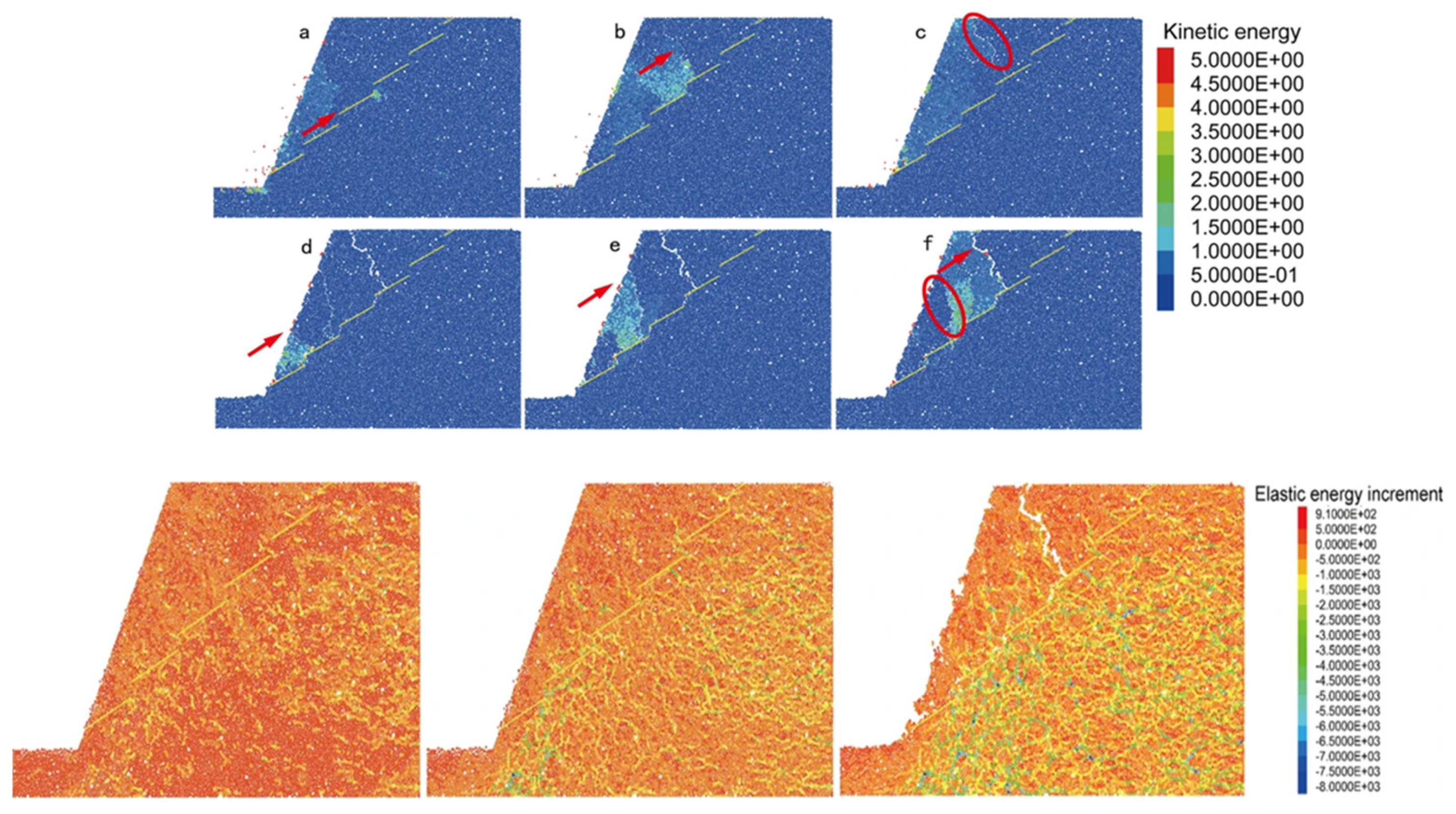

2. The Evolution of Energy and the Accumulation and Transformation of Rock Fatigue Damage

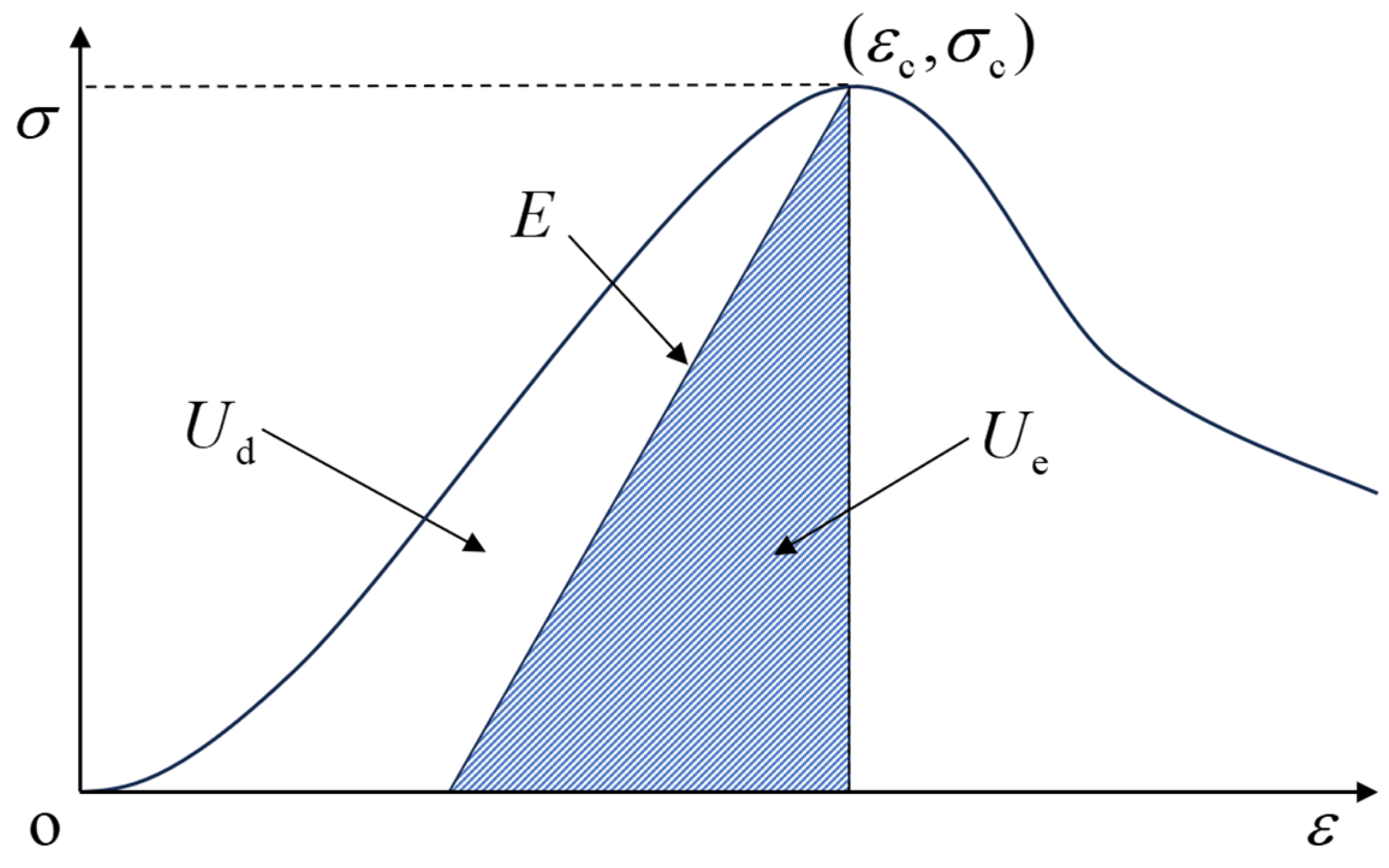

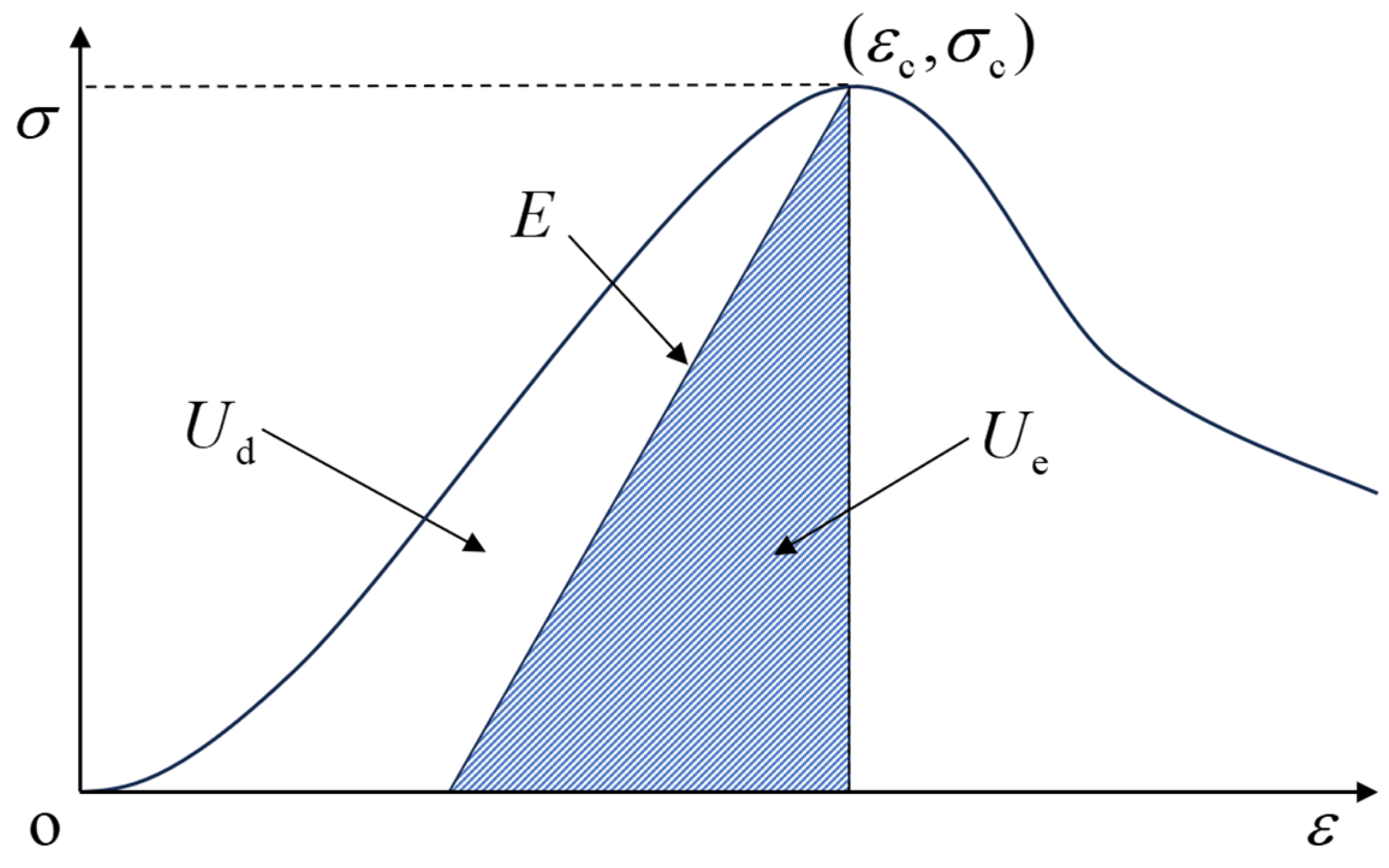

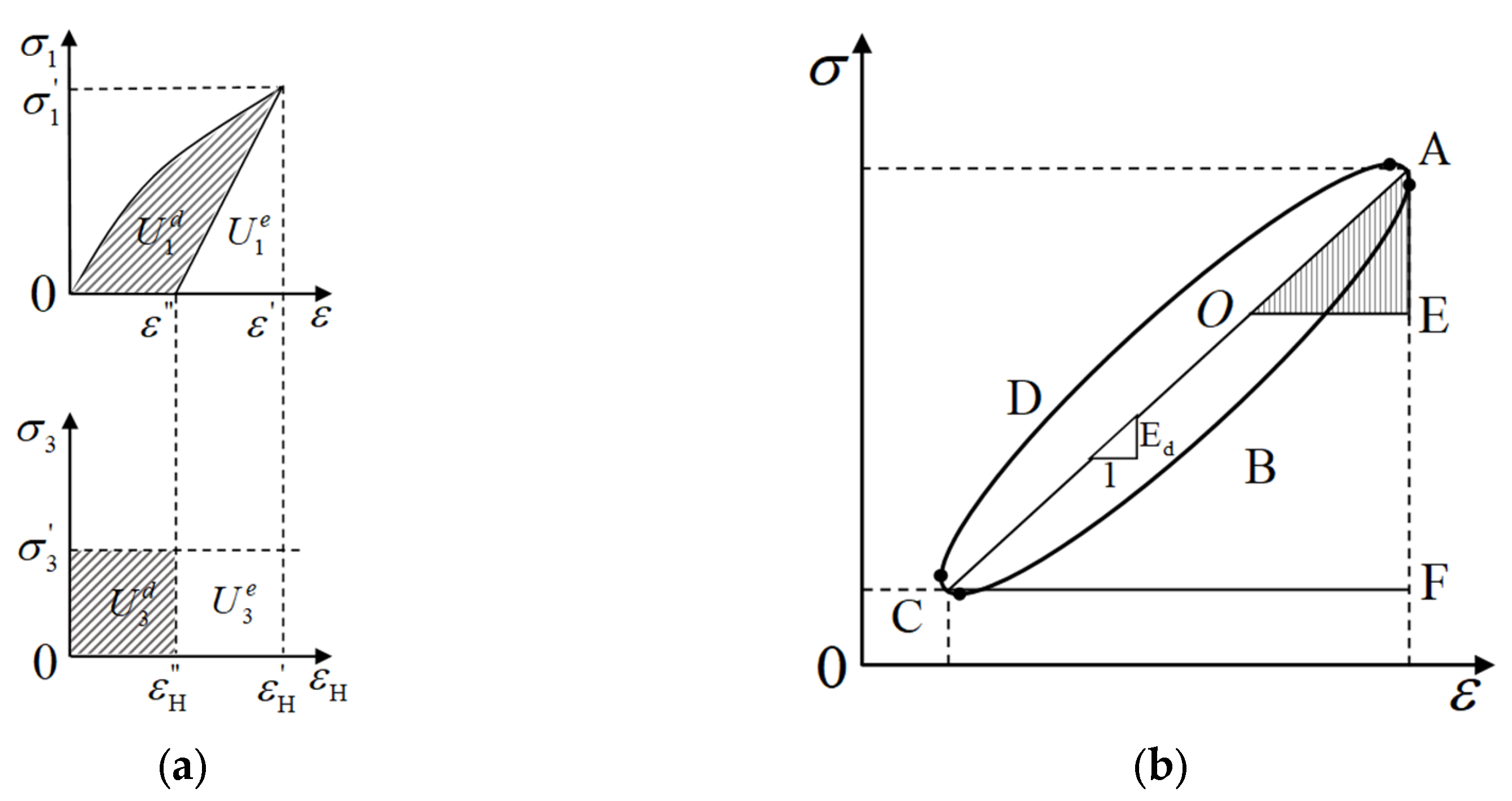

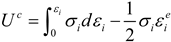

2.1. The Evolution of Energy

2.2. Factors Affecting Rock Fatigue Damage from an Energy Perspective

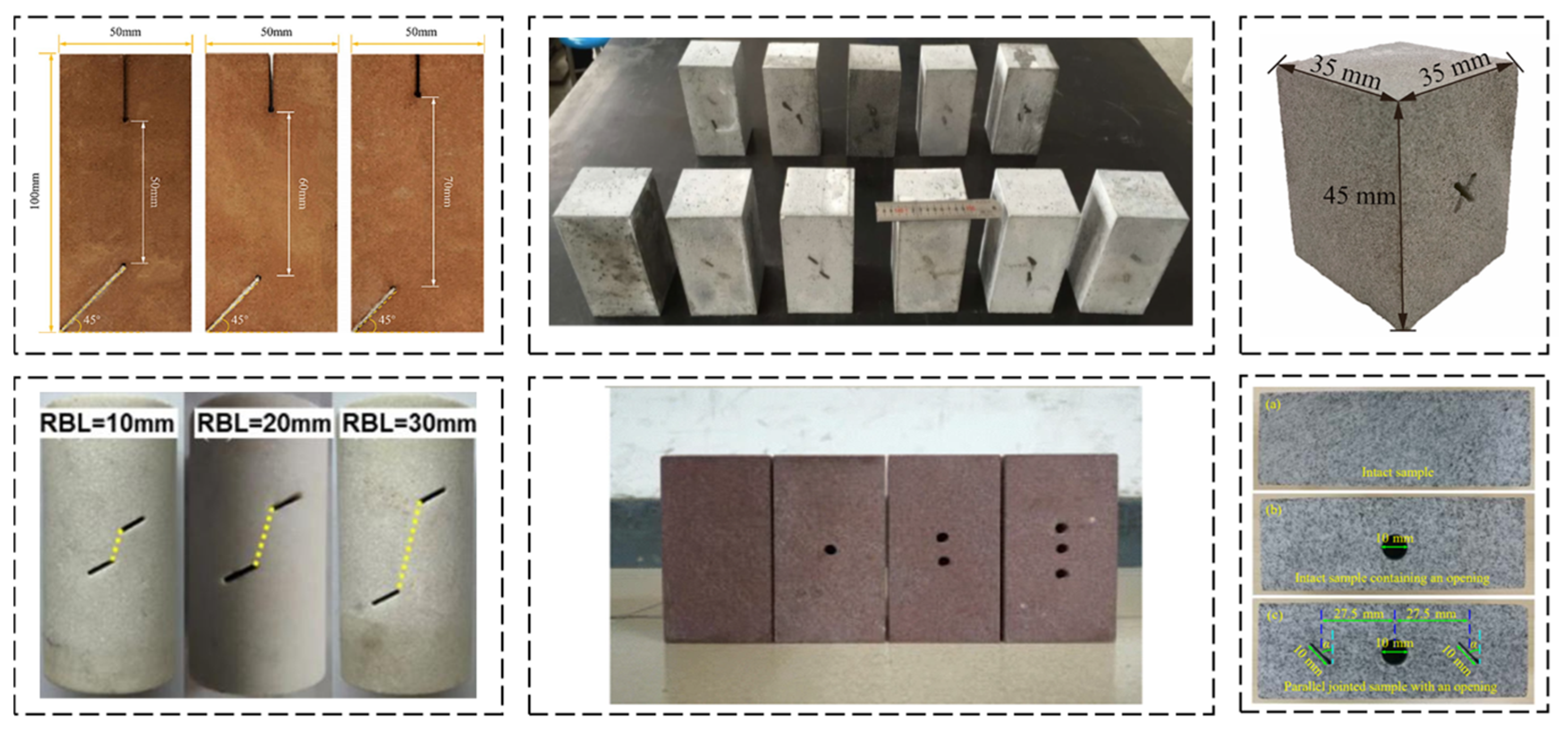

2.2.1. Intrinsic Factors of Rocks

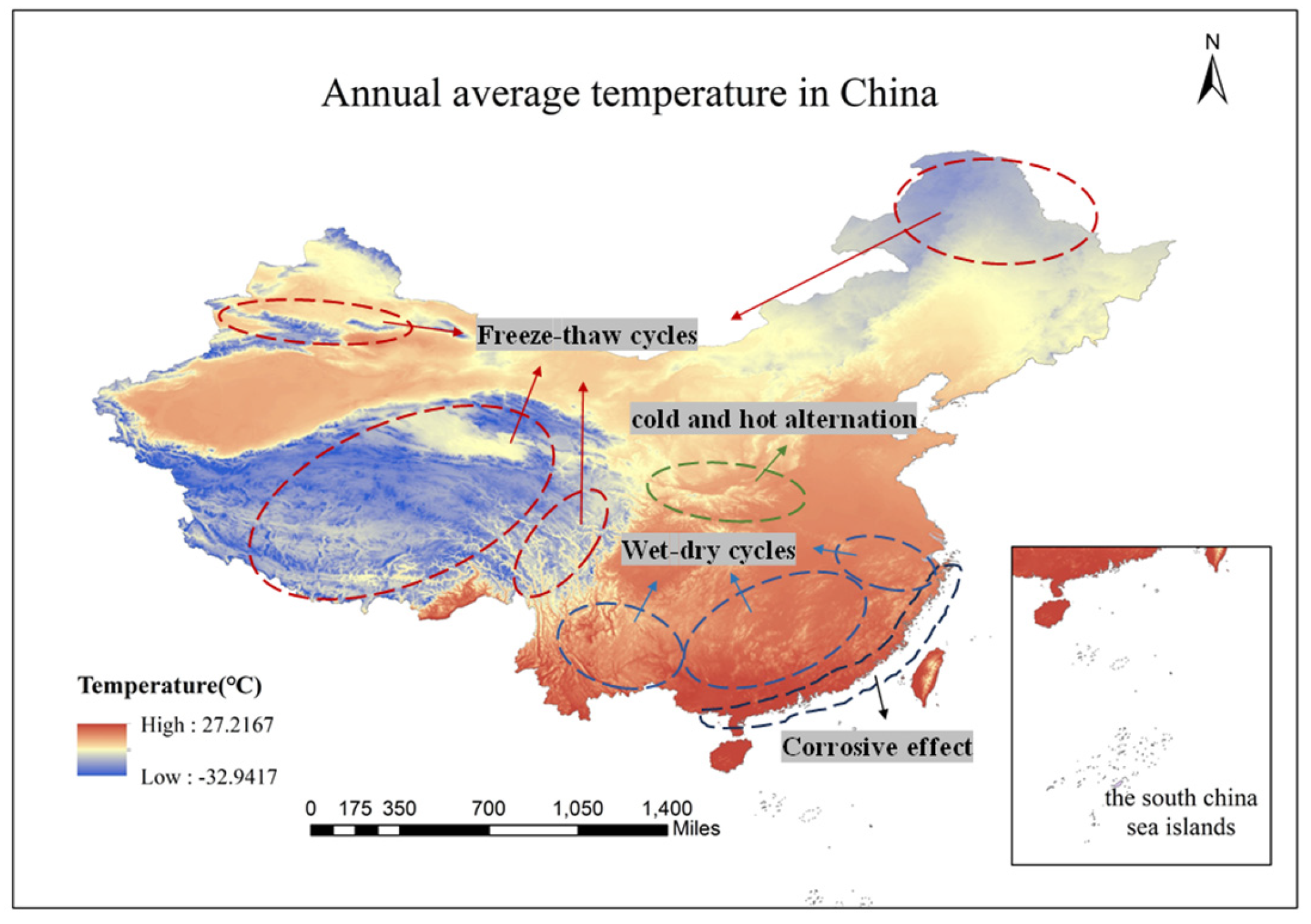

2.2.2. Extrinsic Environmental Factors

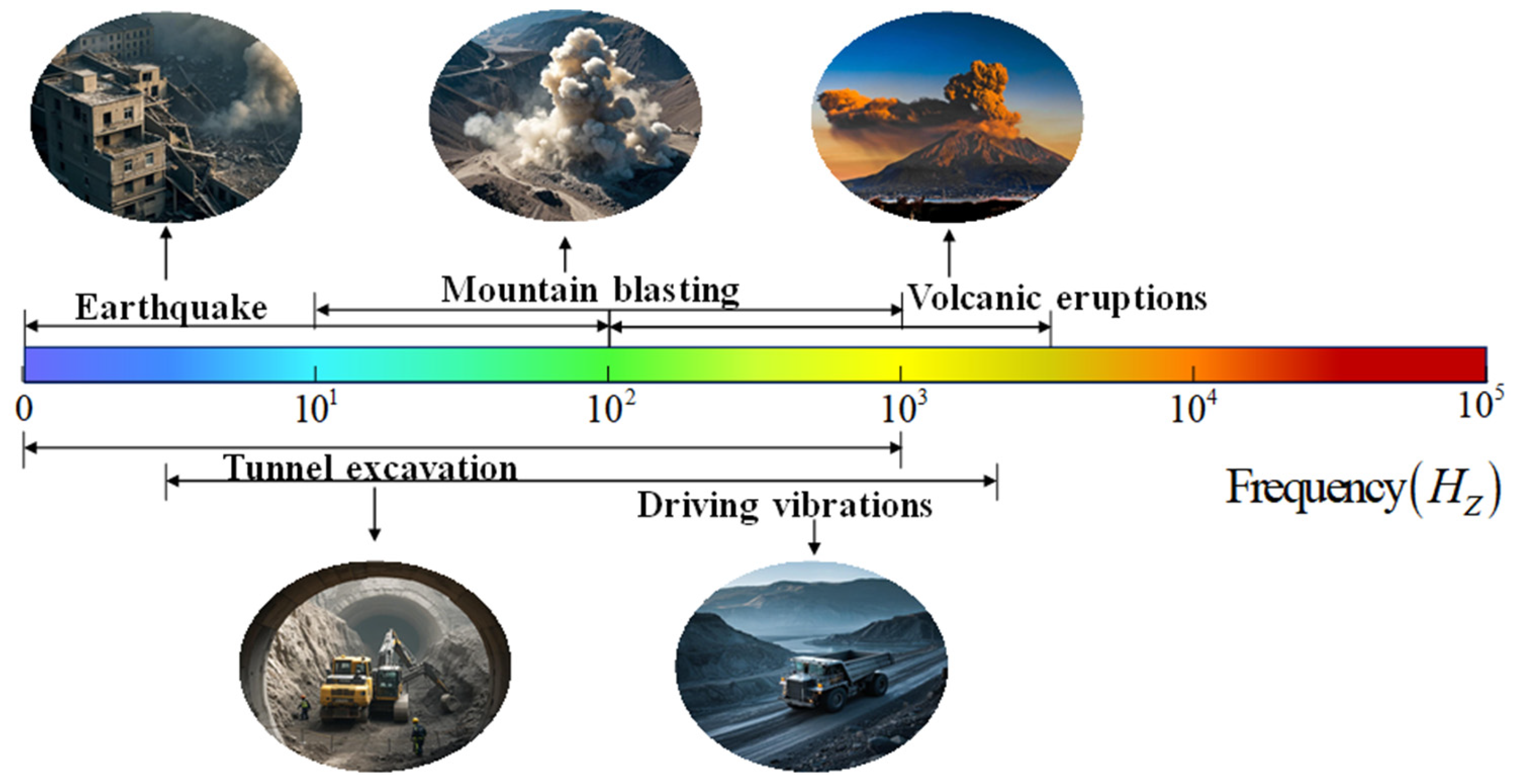

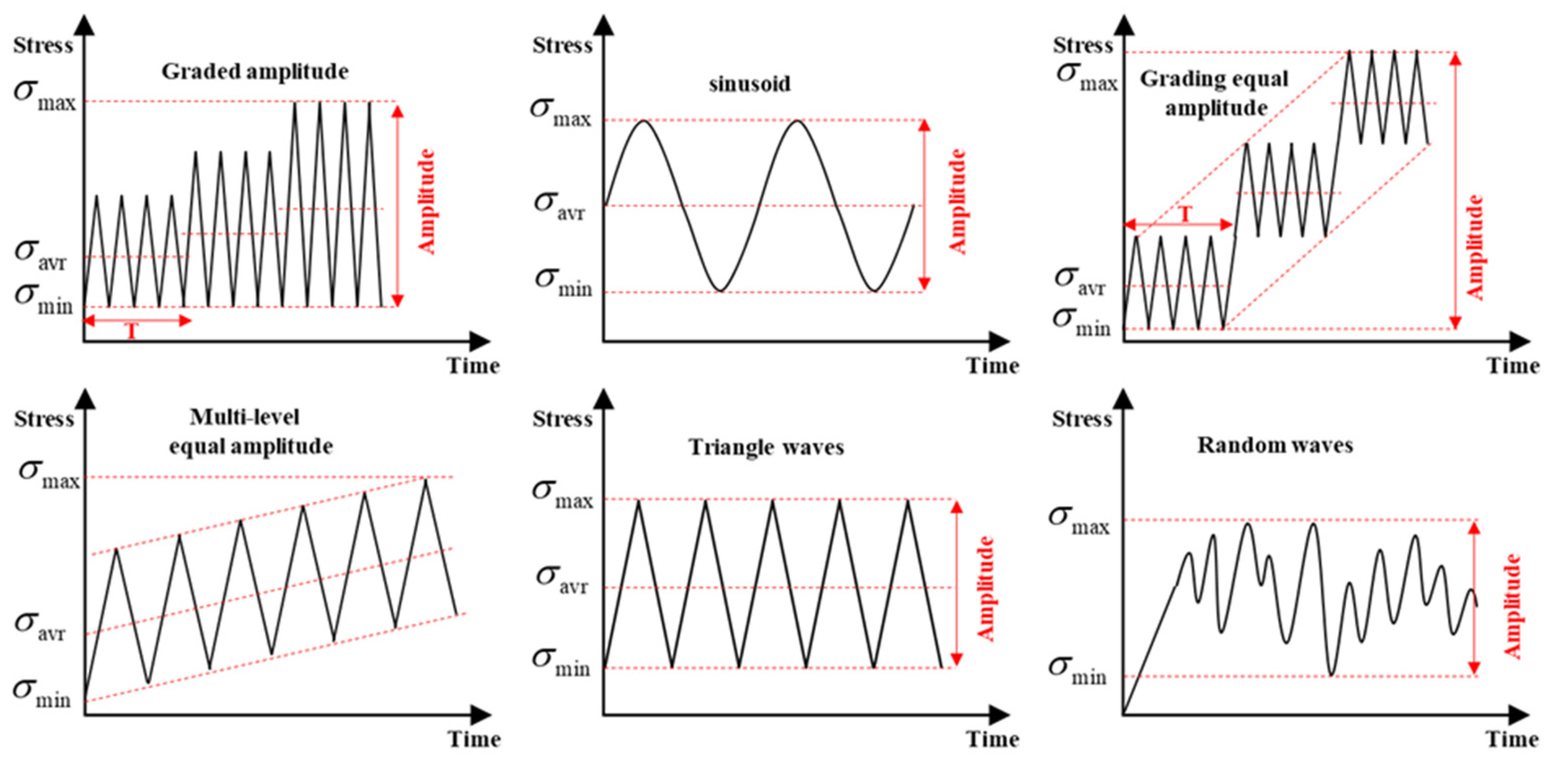

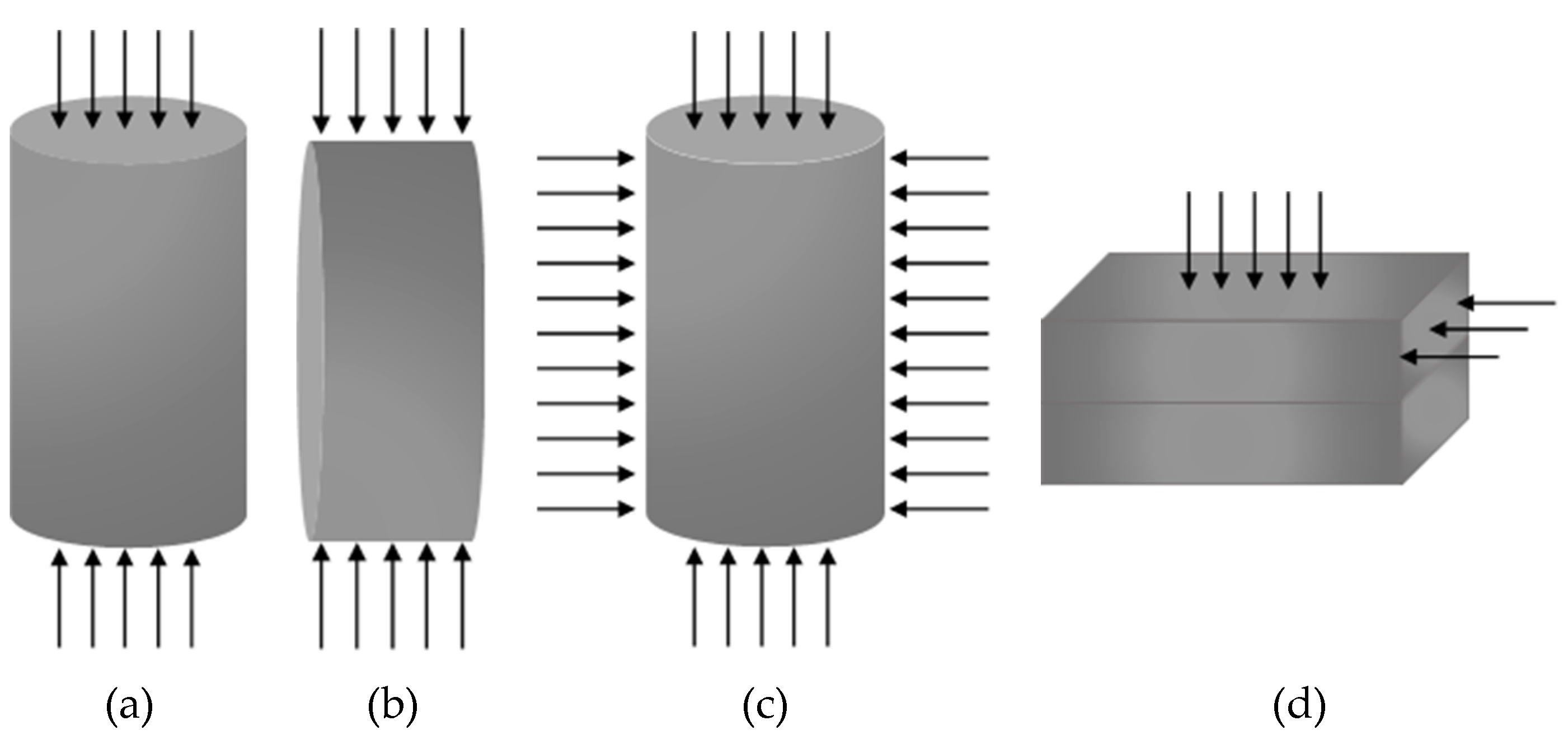

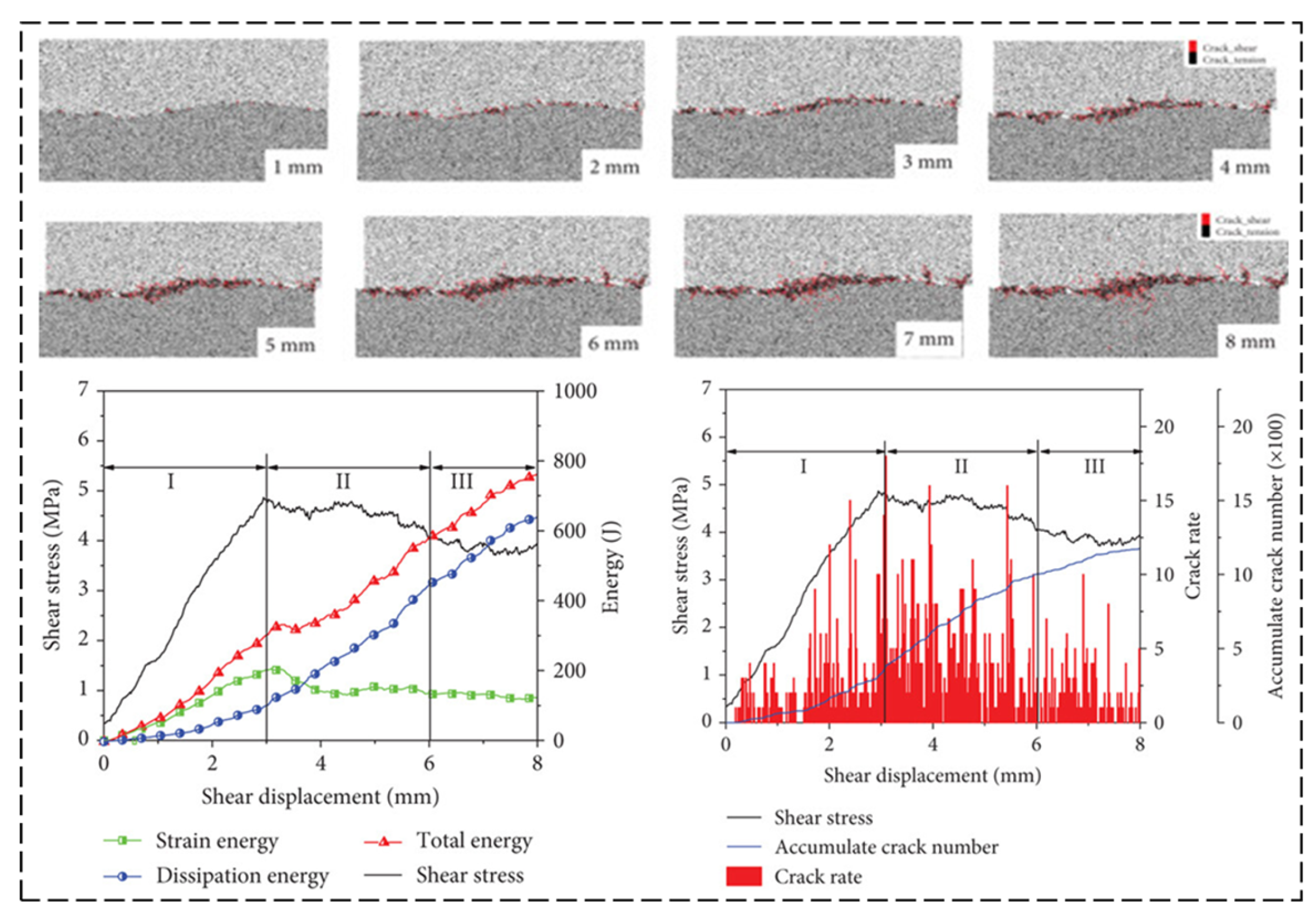

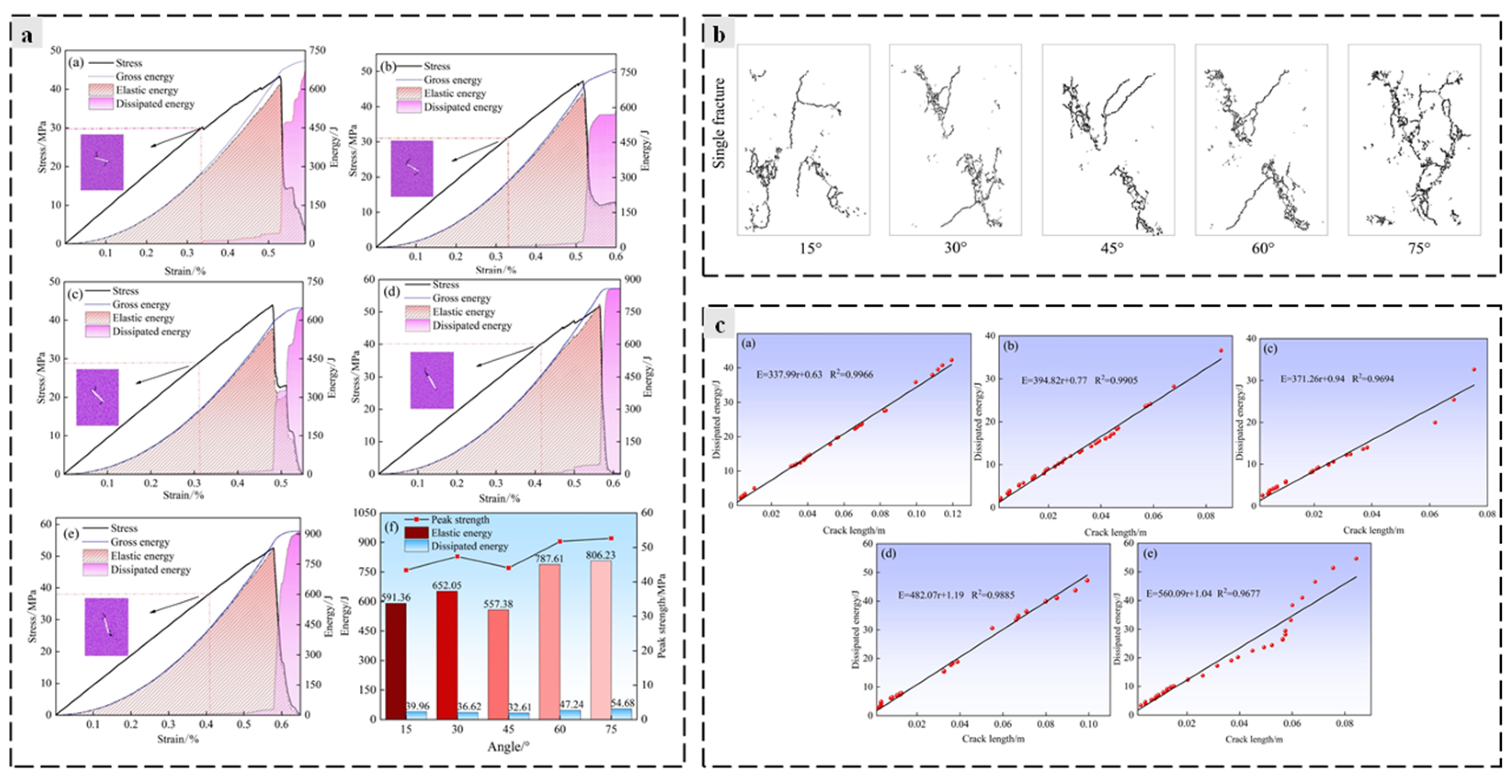

2.2.3. Experimental Loading Factors

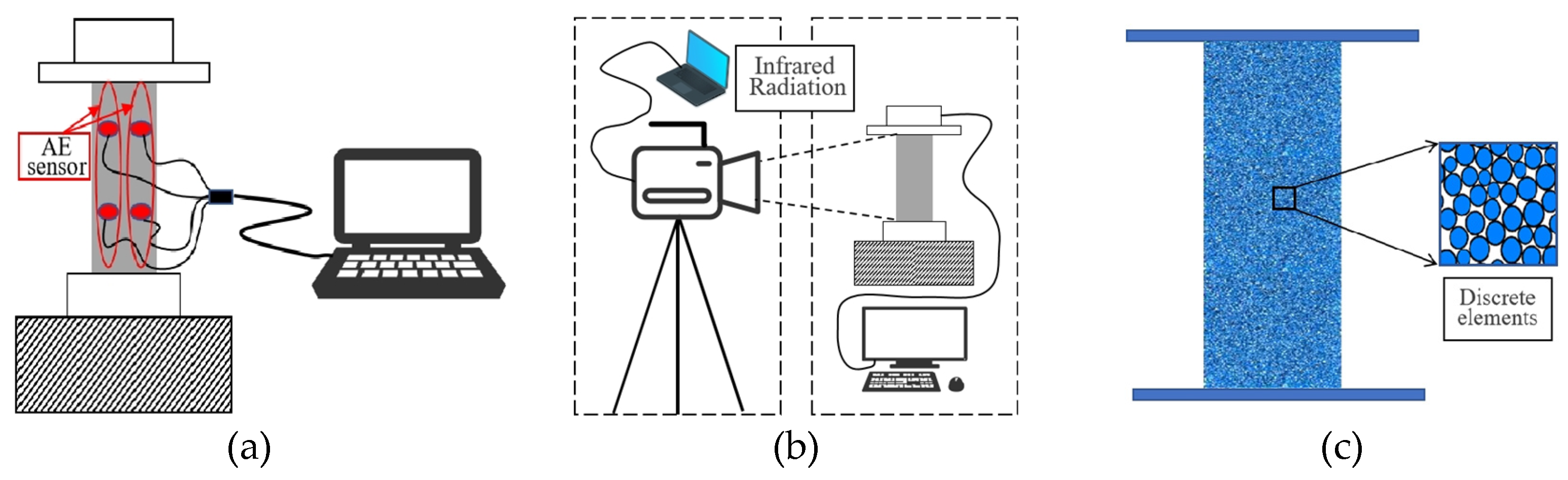

2.3. Changes in Microstructural Characteristics and Macroscopic Mechanical Behavior During the Damage Process

3. Energy-Based Strength Criteria and Constitutive Relations for Rocks

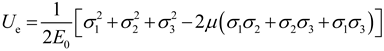

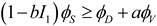

3.1. Rock Strength Criterion

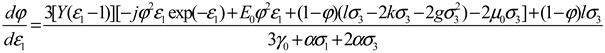

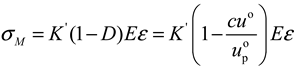

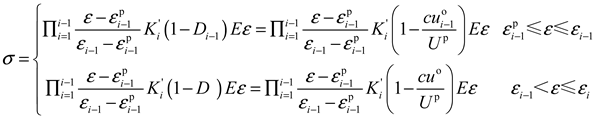

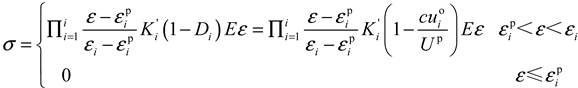

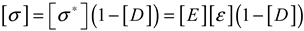

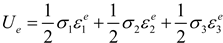

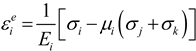

3.2. Damage Variable Evolution and Constitutive Relations Based on Energy Dissipation

3.3. Energy-Based Analysis of Rock Stability

4. Discussions and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erarslan, N. Experimental and numerical investigation of plastic fatigue strain localization in brittle materials: An application of cyclic loading and fatigue on mechanical tunnel boring technologies. International Journal of Fatigue, 2021, 152: 106442. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, D.; Yuan, C.; Nie, W. An image recognition method for the deformation area of open-pit rock slopes under variable rainfall. Measurement, 2022, 188: 110544. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Jiang, L.; Qin, J.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhu, X. Comprehensive safety assessment of two-well-horizontal caverns with sediment space for compressed air energy storage in low-grade salt rocks. Journal of Energy Storage, 2024, 102: 114037. [CrossRef]

- Jelagin, D.; Saadati, M.; Jerjen, I.; Larsson, P.L. Mechanical Characterization of Granite Rock Materials: On the Influence from Pre-Existing Defects. Journal of Testing and Evaluation, 2018, 46(2): 540-548. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.; Abedi, S.; Noshadravan, A. A multiscale modeling of damage accumulation and permeability variation in shale rocks under mechanical loading. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2021, 198: 108123. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Pei, X.; Wang, D.; Huang, R.; Tang, H. Nonlinear behavior and damage model for fractured rock under cyclic loading based on energy dissipation principle. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2019, 206: 330-341. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gong, H.; Huang, J.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Wan, S. Dynamic cumulative damage characteristics of deep-buried granite from Shuangjiangkou hydropower station under true triaxial constraint. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 2022, 165: 104215. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Kang, H.; Zuo, J.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Cai, M.; Liu, J. Study on damage anisotropy and energy evolution mechanism of jointed rock mass based on energy dissipation theory. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2023, 82(8): 294. [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, D.; Helmstetter, A. Brittle creep, damage, and time to failure in rocks. Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth, 2006, 111(B11).

- Preisig, G.; Eberhardt, E.; Smithyman, M.; Preh, A.; Bonzanigo, L. Hydromechanical Rock Mass Fatigue in Deep-Seated Landslides Accompanying Seasonal Variations in Pore Pressures. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2016, 49(6): 2333-2351. [CrossRef]

- Gramiger, L.M.; Moore, J.R.; Gischig, V.S.; Ivy-Ochs, S.; Loew, S. Beyond debuttressing: Mechanics of paraglacial rock slope damage during repeat glacial cycles. Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface, 2017, 122(4): 1004-1036. [CrossRef]

- Voznesenskii, A.S.; Kutkin, Y.O.; Krasilov, M.N.; Komissarov, A.A. Predicting fatigue strength of rocks by its interrelation with the acoustic quality factor. International Journal of Fatigue, 2015, 77: 194-198. [CrossRef]

- Geranmayeh Vaneghi, R.; Thoeni, K.; Dyskin, A.V.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Strength and Damage Response of Sandstone and Granodiorite under Different Loading Conditions of Multistage Uniaxial Cyclic Compression. International Journal of Geomechanics, 2020, 20(9): 04020159. [CrossRef]

- Lajtai, E.Z. Microscopic fracture processes in a granite. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 1998, 31(4): 237-250. [CrossRef]

- Lavrov, A.; Vervoort, A.; Wevers, M. Anisotropic damage formation in brittle rock: Experimental study by means of acoustic emission and Kaiser effect. J. Phys. IV, 2003, 105: 321-328. [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, D.; Gruber, S.; Girard, L. Evidence of frost-cracking inferred from acoustic emissions in a high-alpine rock-wall. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 2012, 341: 86-93.

- Momeni, A.; Karakus, M.; Khanlari, G.R.; Heidari, M. Effects of cyclic loading on the mechanical properties of a granite. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2015, 77: 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Dinc Gogus, O. 3D discrete analysis of damage evolution of hard rock under tension. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2020, 13(14): 661. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, S.; Gong, B.; Jiang, S. Evolutionary characteristics of the fracture network in rock slopes under the combined influence of rainfall and excavation. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2025, 84(1): 47. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, B.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Stress-Energy Mechanism for Rock Failure Evolution Based on Damage Mechanics in Hard Rock. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020, 53(3): 1021-1037. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cui, R.; Cao, K.; Niu, D.; Liu, C. Strain Energy Dissipation Characteristics and Neural Network Model during Uniaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading of Dry and Saturated Sandstone. Minerals, 2023, 13(2): 131. [CrossRef]

- Guy, N.; Seyedi, D.M.; Hild, F. Characterizing Fracturing of Clay-Rich Lower Watrous Rock: From Laboratory Experiments to Nonlocal Damage-Based Simulations. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2018, 51(6): 1777-1787. [CrossRef]

- Haghgouei, H.; Baghbanan, A.; Hashemolhosseini, H. Fatigue life prediction of rocks based on a new Bi-linear damage model. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2018, 106: 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Haghgouei, H.; Hashemolhosseini, H.; Baghbanan, A.; Jamali, S. The Effect of Loading Frequency on Fatigue Life of Green onyx under Fully Reversed Loading. Experimental Techniques, 2018, 42(1): 105-113. [CrossRef]

- Vaneghi, R.G.; Ferdosi, B.; Okoth, A.D.; Kuek, B. Strength degradation of sandstone and granodiorite under uniaxial cyclic loading. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2018, 10(1): 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Qin, Y.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J. A constitutive model for rock based on energy dissipation and transformation principles. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2019, 12(15): 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Saksala, T.; Jabareen, M. Numerical modeling of rock failure under dynamic loading with polygonal elements. International Journal for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 2019, 43(12): 2056-2074. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Hou, D.; Zhu, C. Effect of slope angle on fractured rock masses under combined influence of variable rainfall infiltration and excavation unloading. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2024, 16(10): 4154-4176. [CrossRef]

- Reches, Z.E.; Wetzler, N. Energy dissipation and fault dilation during intact-rock faulting. Journal of Structural Geology, 2025, 191: 105325. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Canbulat, I.; Zhang, C.; Wei, C. Energies Within Rock Mass and the Associated Dynamic Rock Failures. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2025: 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.R.; Hagan, P.; Xu, D.F.; Hu, B.W.; Li, Z.C.; Gamage, K. (2014). Fracture process and energy dissipation analysis of sandstone plates under the concentrated load. Technical Gazette, 21(6), 1345-1351.

- Zhao, Z.; Ma, W.; Fu, X.; Yuan, J. Energy theory and application of rocks. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2019, 12(15): 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Pei, X.; Guo, J.; Meng, M.; Huang, R. An Energy-Based Fatigue Damage Model for Sandstone Subjected to Cyclic Loading. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020, 53(11): 5069-5079. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q. Study on Damage Evolution Model of Sandstone under Triaxial Loading and Postpeak Unloading Considering Nonlinear Behaviors. Geofluids, 2021, 2021(1): 2395789. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Hou, D.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X. Experimental study on instability mechanism and critical intensity of rainfall of high-steep rock slopes under unsaturated conditions. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 2023, 33(10): 1243-1260. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-E.; Jeong, G.-C. Numerical analysis on micro-damage in bisphere model of granitic rock. Geosciences Journal, 2015, 19(1): 135-144. [CrossRef]

- Reches, Z.e.; Wetzler, N. An energy-based theory of rock faulting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 2022, 597: 117818. [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, M.S.; Shahriar, K.; Moarefvand, P.; Gharouninik, M. Application of the strain energy to estimate the rock load in squeezing ground condition of Eamzade Hashem tunnel in Iran. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2013, 6(4): 1241-1248. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dang, S.; Bi, J.; Wang, C.; Gan, F.; Li, J. Energy Evolution Characteristics of Sandstones During Confining Pressure Cyclic Unloading Conditions. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2023, 56(2): 953-972. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Tang, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y. Study on Characteristics of Failure and Energy Evolution of Different Moisture-Containing Soft Rocks under Cyclic Disturbance Loading. Materials, 2024, 17(8): 1770. [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, G.; Yuan, W.; Wang, X.; Meng, X. Fractal Characteristics and Energy Evolution Analysis of Rocks under True Triaxial Unloading Conditions. Fractal and Fractional, 2024, 8(7): 387. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, L.; Ju, Y.; Peng, R.; Yang, Y. Energy analysis for damage and catastrophic failure of rocks. Science China-Technological Sciences, 2011, 54: 199-209. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xue, L.; Duan, Y. Investigation into energy conversion and distribution during brittle failure of hard rock. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2022, 81(3): 114. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Xie, L.; Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Qian, J. Study on Blasting Characteristics of Shallow and Deep Soft-hard Rock Strata Based on Energy Field. Ksce Journal of Civil Engineering, 2023, 27(5): 1942-1954. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.-l.; Yang, G.-s.; Xi, J.-m.; Ni, W.-k.; Ding, X.; Wu, B.-q. Mechanical properties and energy-dissipation mechanism of frozen coarse-grained and medium-grained sandstones. Journal of Central South University, 2023, 30(6): 2018-2034. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Shi, C.; Lou, Y.; Jia, C.; Lei, M.; Yang, Y. A computational method for tunnel energy evolution in strain-softening rock mass during excavation unloading based on triaxial stress paths. Computers and Geotechnics, 2024, 169: 106212. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, T.; Li, Q.; Chen, G.; Cao, B. MECHANISM OF ROCK BURST BASED ON ENERGY DISSIPATION THEORY AND ITS APPLICATIONS IN EROSION ZONE. Acta Geodynamica Et Geomaterialia, 2019, 16(2): 119-130.

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.-T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Yang, C. A Novel Application of Strain Energy for Fracturing Process Analysis of Hard Rock Under True Triaxial Compression. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2019, 52(11): 4257-4272. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gao, F.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, Z. An Energy Preservation Index for Evaluating the Rockburst Potential Based on Energy Evolution. Energies, 2020, 13(14): 3636. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Fan, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, X. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Energy Evolution Characteristic of Granite considering the Loading Rate Effect. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2022, 2022(1): 8260107. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, W. The rock fragmentation mechanism and plastic energy dissipation analysis of rock indentation. Geomechanics and Engineering, 2018, 16(2): 195-204.

- Gong, F.; Yan, J.; Luo, S.; Li, X. Investigation on the Linear Energy Storage and Dissipation Laws of Rock Materials Under Uniaxial Compression. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2019, 52(11): 4237-4255. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Pu, H. Research on non-linear characteristics of rock energy evolution under uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading conditions. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2019, 78(23): 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, S. Experimental Study on Energy Evolution and Storage Performances of Rock Material under Uniaxial Cyclic Compression. Shock and Vibration, 2020, 2020(1): 8842863. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Li, W.; Yue, Z. Comparative Study on Dynamic Mechanical Properties and Energy Dissipation of Rocks under Impact Loads. Shock and Vibration, 2020, 2020(1): 8865099. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Ni, Y.; Jia, H. Effects of specimen size on linear energy storage and dissipation laws of red sandstone under uniaxial compression. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2022, 81(9): 386. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, S.; Khamehchiyan, M.; Taheri, A.; Nikudel, M.R.; Zalooli, A. Crack Evolution in Damage Stress Thresholds in Different Minerals of Granite Rock. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020, 53(3): 1163-1178. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, W. Energy Storage and Release of Class I and Class II Rocks. Energies, 2023, 16(14): 5516. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Heras, M.; Smith, B.J.; Fort, R. Surface temperature differences between minerals in crystalline rocks: Implications for granular disaggregation of granites through thermal fatigue. Geomorphology, 2006, 78(3-4): 236-249. [CrossRef]

- Pouya, A.; Zhu, C.; Arson, C. Micro-macro approach of salt viscous fatigue under cyclic loading. Mechanics of Materials, 2016, 93: 13-31. [CrossRef]

- Shirole, D.; Hedayat, A.; Walton, G. Damage monitoring in rock specimens with pre-existing flaws by non-linear ultrasonic waves and digital image correlation. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2021, 142: 104758. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Faradonbeh, R.S.; Munoz, H. Experimental Study on Progressive Damage Evolution in Rocks Subjected to Post-peak Cyclic Loading History. Geotechnical Testing Journal, 2022, 45(3): 606-626. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Ali, M. Numerical simulation of the morphological effect of rock joints in the processes of concentrating elastic strain energy: a direct shear study. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2020, 13(7): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Li, R.; Xing, L. Research on the Impact of Different Force Directions on the Mechanical Properties and Damage Evolution Law of Sandstone with Different Hole Diameters. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2021, 2021(1): 4247027. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; Dai, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, X. Experimental Investigation of Pre-Flawed Rocks under Dynamic Loading: Insights from Fracturing Characteristics and Energy Evolution. Materials, 2022, 15(24): 8920. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Chen, F. Effect of Bedding Angle on Energy and Failure Characteristics of Soft-Hard Interbedded Rock-like Specimen under Uniaxial Compression. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2024, 14(15): 6826. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Fu, C.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, J. Study on energy damage evolution of multi-flaw sandstone with different flaw lengths. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2024, 132: 104469. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Tang, H.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. Energy Analysis of the Deformation and Failure Process of Sandstone and Damage Constitutive Model. Ksce Journal of Civil Engineering, 2019, 23(2): 513-524. [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhao, T. Influence of two unparallel fissures on the mechanical behaviours of rock-like specimens subjected to uniaxial compression. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, 2020, 24(10): 1643-1663. [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Xu, Y.; Dai, F. Effects of dynamic strain rate on the energy dissipation and fragment characteristics of cross-fissured rocks. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2021, 138: 104600. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Gong, F.; Wu, W.; Wang, W. Experimental investigation of the mechanical behaviors and energy evolution characteristics of red sandstone specimens with holes under uniaxial compression. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2021, 80(7): 5845-5865. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Cai, M.F.; Wang, P.T.; Guo, Q.F.; Miao, S.J.; Ren, F.H. Mechanical properties and energy evolution of jointed rock specimens containing an opening under uniaxial loading. International Journal of Minerals Metallurgy and Materials, 2021, 28(12): 1875-1886. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Yi, X. Cyclic fatigue responses of double fissure-contained marble: Insights from mechanical responses, energy conversion and hysteresis characteristics. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2024, 134: 104750. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, T.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tang, O. Weakening effects of the presence of water on the brittleness of hard sandstone. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2019, 78(3): 1471-1483. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; You, S.; Ji, H.-g.; Elmo, D.; Wang, H.-t. Strength and energy exchange of deep sandstone under high hydraulic conditions. Journal of Central South University, 2020, 27(10): 3053-3062. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Study on mechanical properties and energy characteristics of carbonaceous shale with different fissure angles under dry-wet cycles. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2022, 81(8): 319. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cao, S.; Zhou, K.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, L. Damage characteristics and energy-dissipation mechanism of frozen-thawed sandstone subjected to loading. Cold Regions Science and Technology, 2020, 169: 102920. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, H.; Li, B. Research on Fracture and Energy Evolution of Rock Containing Natural Fractures under Cyclic Loading Condition. Geofluids, 2021, 2021(1): 9980378. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, B. Energy-driven damage evolution and instability in fissure-cavity-contained granite induced by freeze-thaw and multistage increasing-amplitude cyclic (F-T-MSIAC) loads. International Journal of Damage Mechanics, 2023, 32(3): 362-386. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, S.H.; Li, C.H.; Han, J.Q. Energy dissipation and damage evolution for dynamic fracture of marble subjected to freeze-thaw and multiple level compressive fatigue loading. International Journal of Fatigue, 2021, 142: 105927. [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Zhao, E. Evolution of Freeze-Thaw Damage Characteristics and Corresponding Models of Intact and Fractured Rocks Under Uniaxial Compression. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024, 57(10): 8013-8033. [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, E.V.; Kurilko, A.S. Local minimum of energy consumption in hard rock failure in negative temperature range. Journal of Mining Science, 2014, 50(2): 284-287. [CrossRef]

- Erarslan, N.; Williams, D.J. The damage mechanism of rock fatigue and its relationship to the fracture toughness of rocks. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2012, 56: 15-26. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Hao, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Deng, N. Influence of temperature on the transformation and self-control of energy during sandstone damage: Experimental and theoretical research. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 2022, 32(4): 761-777. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.B.; Liu, J.F.; Huang, B.X.; Pu, H.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z. Effects of Confining Pressure and Temperature on the Energy Evolution of Rocks Under Triaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading Conditions. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2022, 55(2): 773-798. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wu, Y.; Cao, K.; Khan, N.M.; Hussain, S.; Lee, S.; Ma, C. Analysis of Mudstone Fracture and Precursory Characteristics after Corrosion of Acidic Solution Based on Dissipative Strain Energy. Sustainability, 2021, 13(8): 4478. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Tian, A.; Luo, X.; Liao, X.; Tang, Q. Chemical Damage Constitutive Model Establishment and the Energy Analysis of Rocks under Water-Rock Interaction. Energies, 2022, 15(24): 9386. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Shen, Y.; Yang, T. Eect of acid corrosion on physico-mechanical parameters and energy dissipation of granite. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2024, 12: 1497900. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wu, Q.; Fan, B.; Tang, Z. Experimental Research on Energy Evolution of Sandstone with Different Moisture Content under Uniaxial Compression. Sustainability, 2024, 16(11): 4636. [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Li, D.; Ma, J.; Zhao, J.; Jabbar, A. Experimental study on energy and damage evolution of dry and water-saturated dolomite from a deep mine. International Journal of Damage Mechanics, 2025, 334(2): 303-325. [CrossRef]

- Bagde, M.N.; Petros, V. Fatigue properties of intact sandstone samples subjected to dynamic uniaxial cyclical loading. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2005, 42(2): 237-250. [CrossRef]

- Gischig, V.; Preisig, G.; Eberhardt, E. Numerical Investigation of Seismically Induced Rock Mass Fatigue as a Mechanism Contributing to the Progressive Failure of Deep-Seated Landslides. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2016, 49(6): 2457-2478. [CrossRef]

- Cerfontaine, B.; Collin, F. Cyclic and Fatigue Behaviour of Rock Materials: Review, Interpretation and Research Perspectives. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2018, 51(2): 391-414. [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Liu, S.; Elsworth, D. Quantifying fatigue-damage and failure-precursors using ultrasonic coda wave interferometry. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2020, 131: 104366. [CrossRef]

- Vaneghi, R.G.; Thoeni, K.; Dyskin, A.V.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Fatigue damage response of typical crystalline and granular rocks to uniaxial cyclic compression. International Journal of Fatigue, 2020, 138: 105667. [CrossRef]

- Young, J.G.; Sic, J.H.; An, J.B. Damage Characteristics of Rocks by Uniaxial Compression and Cyclic Loading-Unloading Test. The journal of Engineering Geology, 2021, 31(2): 149-163.

- Moghaddam, R.H.; Golshani, A. Fatigue behavior investigation of artificial rock under cyclic loading by using discrete element method. Engineering Failure Analysis, 2024, 160: 108105. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Hu, J.; Ding, X. Analysis of energy dissipation characteristics in granite under high confining pressure cyclic load. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2020, 59(5): 3587-3597. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Zhang, P.; Du, K. A Novel Staged Cyclic Damage Constitutive Model for Brittle Rock Based on Linear Energy Dissipation Law: Modelling and Validation. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2022, 55(10): 6249-6262. [CrossRef]

- Bagde, M.N.; Petros, V. Waveform effect on fatigue properties of intact sandstone in uniaxial cyclical loading. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2005, 38(3): 169-196.

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Experimental Investigation of Failure Mode and Energy Evolution under Uniaxial Recompression of Granite Predamaged. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2024, 2024(1): 4400608. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; He, C.; Hu, X.Y.; Ma, C.C. Effect of stress paths on failure mechanism and progressive damage of hard-brittle rock. Journal of Mountain Science, 2021, 18(9): 2486-2502. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Ma, J. Energy Evolution Law of Sandstone Material during Post-Peak Cyclic Loading and Unloading under Hydraulic Coupling. Sustainability, 2024, 16(1): 24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Xia, Y.; Long, D. New insights into the fracture evolution and instability warning predication for fissure-contained hollow-cylinder granite with different hole diameter under multi-stage cyclic loads. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2022, 119: 103363. [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Shang, X.; Wang, H.; Liang, M.; Yang, P.; Liu, C. Deformation Characteristics and Energy Evolution Rules of Siltstone under Stepwise Cyclic Loading and Unloading. Buildings, 2024, 14(6): 1500. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, Y.F.; Li, C.H.; Han, J.Q. Anisotropic fracture and energy characteristics of a Tibet marble exposed to multi-level constant-amplitude (MLCA) cyclic loads: A lab-scale testing. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2021, 244: 107550. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Bian, L. Response and energy dissipation of rock under stochastic stress waves. Journal of Central South University of Technology, 2007, 14(1): 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Zhou, Z.L.; Yin, T.B.; Liao, G.Y.; Ye, Z.Y. Energy consumption in rock fragmentation at intermediate strain rate. Journal of Central South University of Technology, 2009, 16(4): 677-682. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, M.; Jin, Y.; Zou, D. Theoretical analysis and experimental research on the energy dissipation of rock crushing based on fractal theory. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2016, 33: 231-239. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, M.; Han, L.; Pu, H.; Nie, T. Effects of Acoustic Emission and Energy Evolution of Rock Specimens Under the Uniaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading Compression. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2016, 49(10): 3873-3886. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Gong, F. Linear Energy Storage and Dissipation Laws of Rocks Under Preset Angle Shear Conditions. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020, 53(7): 3303-3323. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, Y. Dynamic Shear Failure of Freeze-Thawed Tibet Hornfels Subjected to Multilevel Cyclic Shear (MLCS) Loads: Insights into Structural Dependent Failure Characteristics. Lithosphere, 2022, 2021(Special 7): 9551299. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Gong, F. Investigation on Energy Evolution and Storage Characteristic of CSTBD Red Sandstone during Mixed-Mode Fracture. Geofluids, 2022, 2022(1): 9822469. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, G.; Kang, Z. Mechanical behavior of rock under uniaxial tension: Insights from energy storage and dissipation. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2024, 16(7): 2466-2481. [CrossRef]

- Becks, H.; Classen, M. Mode II Behavior of High-Strength Concrete under Monotonic, Cyclic and Fatigue Loading. Materials, 2021, 14(24): 7675. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, Z.; Jia, H. Experimental research on energy release characteristics of water-bearing sandstone alongshore wharf. Polish Maritime Research, 2017, 24: 147-153. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Meng, Q.; Liu, S. Energy Evolution Characteristics and Distribution Laws of Rock Materials under Triaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading Compression. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2017, 2017(1): 5471571. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S. Failure energy evolution of coal-rock combination with different inclinations. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12(1): 19455. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Gong, F.Q.; Li, L.L.; Peng, K. Linear energy storage and dissipation laws and damage evolution characteristics of rock under triaxial cyclic compression with different confining pressures. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2023, 33(7): 2168-2182. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, H.R.; Ghazvinian, A. Brittleness Effect on Rock Fatigue Damage Evolution. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2014, 47(5): 1839-1848. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Diaz, M.B.; Kim, K.Y.; Hofmann, H.; Zimmermann, G. Fatigue Behavior of Granite Subjected to Cyclic Hydraulic Fracturing and Observations on Pressure for Fracture Growth. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2021, 54(10): 5207-5220. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Ma, L.; Wu, Y.; Khan, N.M.; Yang, J. Using the characteristics of infrared radiation during the process of strain energy evolution in saturated rock as a precursor for violent failure. Infrared Physics & Technology, 2020, 109: 103406. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, K.; Gao, F.; Gu, Z.; Yang, C. Research on the Mechanical Characteristics of Cyclic Loading and Unloading of Rock Based on Infrared Thermal Image Analysis. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, 2021(1): 5578629. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhu, H. Y.; Han, J.; Fu, C.; Chen, M.M.; Wang, K. Energy and Infrared Radiation Characteristics of the Sandstone Damage Evolution Process. Materials, 2023, 16(12): 4342. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, M.; Huang, H.; Tong, Y. Damage quantification and failure prediction of rock: A novel approach based on energy evolution obtained from infrared radiation and acoustic emission. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2024, 183: 105920. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tan, Y.L.; Liu, X.S.; Zhao, Z.H.; Fan, D.Y. Mechanical and energy characteristics of coal-rock composite sample with different height ratios: a numerical study based on particle flow code. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2021, 80(8): 309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mei, G.; Xi, N.; Liu, Z.; Lin, R. An Energy-Based Discrete Element Modeling Method Coupled with Time-Series Analysis for Investigating Deformations and Failures of Jointed Rock Slopes. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2021, 11(12): 5447. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q. PFC Simulation Study on Time-dependent Deformation Failure Properties and Energy Conversion Law of Sandstone under Different Axial Stress. Periodica Polytechnica-Civil Engineering, 2022, 66(4): 1169-1182. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, F.; Deng, J.; Chen, F.; Li, H.; Li, B. Fracture and energy evolution of rock specimens with a circular hole under multilevel cyclic loading. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, 2023, 127: 103996. [CrossRef]

- Chajed, S.; Singh, A. Acoustic Emission (AE) Based Damage Quantification and Its Relation with AE-Based Micromechanical Coupled Damage Plasticity Model for Intact Rocks. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024, 57(4): 2581-2604. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luan, H.; Shan, Q.; Li, B.; Wang, D.; Jia, C. Study on the Effect of Rock Strength on the Macro-Meso Shear Behaviors of Artificial Rock Joints. Geofluids, 2022, 2022(1): 1968938. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Wen, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; Lin, J.; Chen, B.; Rong, P.; Jin, K.; Du, S. Crack-tip propagation laws and energy evolution of fractured sandstone. Engineering Failure Analysis, 2024, 166: 108832. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gui, X.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zheng, Y. Determination method of rock characteristic stresses based on the energy growth rate. Frontiers in Earth Science, 2023, 11: 1187864. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Luo, Z.; Xia, H.; Gao, S.; Li, P.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Fatigue failure and energy evolution of double-stepped fissures contained marble subjected to multilevel cyclic loads: a lab-scale testing. Frontiers in Materials, 2023, 10: 1204264. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chang, J.; Manda, E.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Jing, Y. Rock crack initiation triggered by energy digestion. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1): 15222. [CrossRef]

- Tiraviriyaporn, P.; Aimmanee, S. Energy-based universal failure criterion and strength-Poisson’s ratio relationship for isotropic materials. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 2022, 230: 107534. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, L.; Peng, R.; Ju, Y. Energy analysis and criteria for structural failure of rocks. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, 2009, 1(1): 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Tang, C.a.; Yan, L. Rock Damage and Energy Balance of Strainbursts Induced by Low Frequency Seismic Disturbance at High Static Stress. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2020, 53(11): 4857-4872. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L. Study on Rock Failure Criterion Based on Elastic Strain Energy Density. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(14): 8435. [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.S.; Liang, W.G. A New Improved Failure Criterion for Salt Rock Based on Energy Method. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2016, 49(5): 1721-1731. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, F. Energy evolution mechanism in process of Sandstone failure and energy strength criterion. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2018, 154: 21-28. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Liang, Z.; Jia, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, J. Energy evolution analysis and related failure criterion for layered rocks. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 2023, 82(12): 439. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Zhang, P.; Luo, S.; Li, J.; Huang, D. Theoretical damage characterisation and damage evolution process of intact rocks based on linear energy dissipation law under uniaxial compression. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2021, 146: 104858. [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Gong, F.; Peng, K. Theoretical shear damage characterization of intact rock under compressive-shear stress considering energy dissipation. International Journal of Damage Mechanics, 2023, 32(7): 962-983. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Gong, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S. Characteristics of Energy Evolution and Failure Mechanisms in Sandstone Subject to Triaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading Conditions. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2024, 14(19): 8693. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Che, H.; Yuan, C.; Qin, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H. Study on multi-scale damage and failure mechanism of rock fracture penetration: experimental and numerical analysis. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, 2024, 28(10): 2385-2401. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Zhang, P.; Xu, L. Damage constitutive model of brittle rock under uniaxial compression based on linear energy dissipation law. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2022, 160: 105273. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Tan, T.; Zhao, E.C. Energy evolution model and energy response characteristics of freeze-thaw damaged sandstone under uniaxial compression. Journal of Central South University, 2024:1-21. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Sun, B. Energy Evolution of Rock under Different Stress Paths and Establishment of a Statistical Damage Model. Ksce Journal of Civil Engineering, 2019, 23(10): 4274-4287. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Fan, Z. Mechanical Characteristics and Energy Evolution Laws for Red Bed Rock of Badong Formation under Different Stress Paths. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2019, 2019(1): 8529329. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y. Research on the energy evolution characteristics and the failure intensity of rocks. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 2020, 30(5): 705-713. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, P.; Li, S.; Ho, C.-H.; Zhu, S.; Kong, X.; Barbieri, D.M. Mechanical Properties and Energy Dissipation Characteristics of Coal-Rock-Like Composite Materials Subjected to Different Rock-Coal Strength Ratios. Natural Resources Research, 2021, 30(3): 2179-2193. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, X.; Dai, S.; Chen, D. Numerical Study on Stability of Rock Slope Based on Energy Method. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2016, 2016(1): 2030238. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wang, S.; Pei, X.; Chen, W. Indices to Determine the Reliability of Rocks under Fatigue Load Based on Strain Energy Method. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2019, 9(3): 360. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dang, S.; Bi, J.; Wang, C.-L.; Gan, F. Influence of Complex Stress Path on Energy Characteristics of Sandstones under Triaxial Cyclic Unloading Conditions. International Journal of Geomechanics, 2022, 22(6): 0422076. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, P.; Cai, X.; Cao, W. Influence of Water Content on Energy Partition and Release in Rock Failure: Implications for Water-Weakening on Rock-burst Proneness. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2023, 56(9): 6189-6205. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, S. Numerical modeling of progressive damage and failure of tunnels deeply-buried in rock considering the strain-energy-density theory. Revista Internacional De Metodos Numericos Para Calculo Y Diseno En Ingenieria, 2024, 40(2): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Huang, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, N. Energy Dissipation-Based Method for Fatigue Life Prediction of Rock Salt. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2018, 51(5): 1447-1455. [CrossRef]

- He, M.M.; Li, N.; Huang, B.Q.; Zhu, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Plastic Strain Energy Model for Rock Salt Under Fatigue Loading. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica, 2018, 31(3): 322-331. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lv, W.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, Q.; Han, G.; Hao, J.; Chen, W.; Wu, F. New failure criterion for rock slopes with intermittent joints based on energy mutation. Natural Hazards, 2023, 118(1): 407-425. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Calculation formula | Content |

|---|---|---|

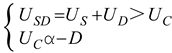

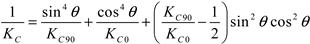

| Tiraviriyaporn, P. et al. [136] |  |

Derive the energy-based strength failure criterion for rock materials based on volumetric strain energy density and deviatoric strain energy density. |

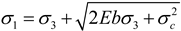

| Xie, H. et al. [137] |  |

Energy dissipation-based strength deterioration criterion for rock units |

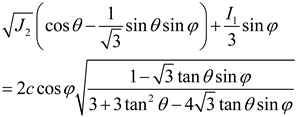

| Hu, L. et al. [138] |  |

Energy criterion for rock strength failure induced by strain burst under cyclic disturbance |

| Cheng, Y. et al. [139] |  |

Rock failure criterion based on elastic strain energy density |

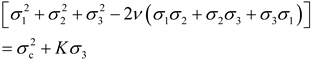

| Hao, T.S. et al. [140] |  |

Energy-based triple shear energy yield criterion for salt rock |

| Wang, Y. et al. [141] |  |

Energy-derived rock failure criterion |

| Gao, M. et al. [142] |  |

Energy mutation-derived rock failure criterion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).