1. Introduction

The scientific field of nanotechnology encompasses the manipulation and control of materials, substances, and devices on the scale of billionths of a meter (1x10

-9), as indicated by the prefix "nano," derived from the Greek word for dwarf. With regard to silver nitrate, there are documented instances of its use in the treatment of wounds due to its bactericidal and antimicrobial effects. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was employed for the treatment of ulcers [

1,

2]. In the 1920s, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved electro colloidal silver solutions as antibacterial agents, some of which were reported in the Pharmacopoeia of the United Mexican States (FEUM by its acronym in Spanish), but it was not until 1960 that it began to be used for the treatment of burns, however, with the introduction of antibiotics in 1940, the use of this type of salt decreased [

3,

4,

5].

In light of the aforementioned considerations, the pursuit of less invasive alternatives for the treatment of these conditions is a compelling avenue of research. The use of colloidal silver as an antibacterial agent represents a notable example. However, the advent of novel silver-based compounds has led to the development of a diverse range of applications, including colloidal or protein-bound solutions for food disinfection and the treatment of severe burns, such as silver sulfadiazine, which exhibits a notable bactericidal effect [

6,

7].

The synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) is typically conducted using a variety of techniques, including top-down and bottom-up approaches [

6]. The top-down technique involves mechanical grinding using specialized equipment, whereas the bottom-up approach relies on chemical reduction, electrochemical methods, and sono-decomposition [

2,

6,

8] The principal benefit of these techniques is their cost-effectiveness, as the utilization of sophisticated instrumentation is costly, and the aforementioned approach is both economical and environmentally benign. Nevertheless, there are also drawbacks. One such drawback is the toxicity of the reagents employed at elevated concentrations, including citrate, borohydride, thioglycerol, and 2-mercaptan in the synthesis of nanoparticles [

8,

9].

The aim of this paper is to present a cost-effective and environmentally friendly synthesis method to functionalize nanoparticles with the antibiotic clindamycin, as it inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit, disrupting ribosome assembly in the translation process. This method is an alternative to other reduction methods that have been shown to generate toxicity in metal nanoparticles. The choice of the synthesis method depends on several factors, including the desired material, stability, shape, quantity, equipment and budget [

9,

10,

11,

12]. These considerations are shared by new pharmaceutical research and are part of technological research related to the production of different drugs, including antibiotics [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] in the use in nanomedicine [

19].

Accordingly, the objective of this study was to synthesize AgNPs and the complex formed with the antibiotic clindamycin, with the aim of enhancing their drug-bound fungicidal and bactericidal properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reactives

Sodium hydroxide (99% pure p.a., Sigma Aldrich), silver nitrate p.a. Merck, Thermo Scientific Chemicals Brand Ultrapure Polyvinylpyrrolidone, 1-ethylene, 1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone (PVP-40) K30, Polyethylene Glycol, poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-hydroxy-omega-hydroxy, 20,000 Flake, Baker, ultrapure water, Millipore filters, BIOHIT micropipettes, PYREX glassware and Whatman filter paper. Clindamycin standard drug were used (Pfizer laboratories).

2.2. Equipment

Thermo Scientific CIMAREC magnetic stirrer, Bruker Alpha P Fourier transform infrared FTIR spectrophotometer with near-IR beam splitter sources (NIR, 400 to 4000/cm-1), GENESYS 10S Uv-vis spectrophotometer with 1 cm quartz cells path length and a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 automated particle size measurement equipment from Malvern Panalytical.

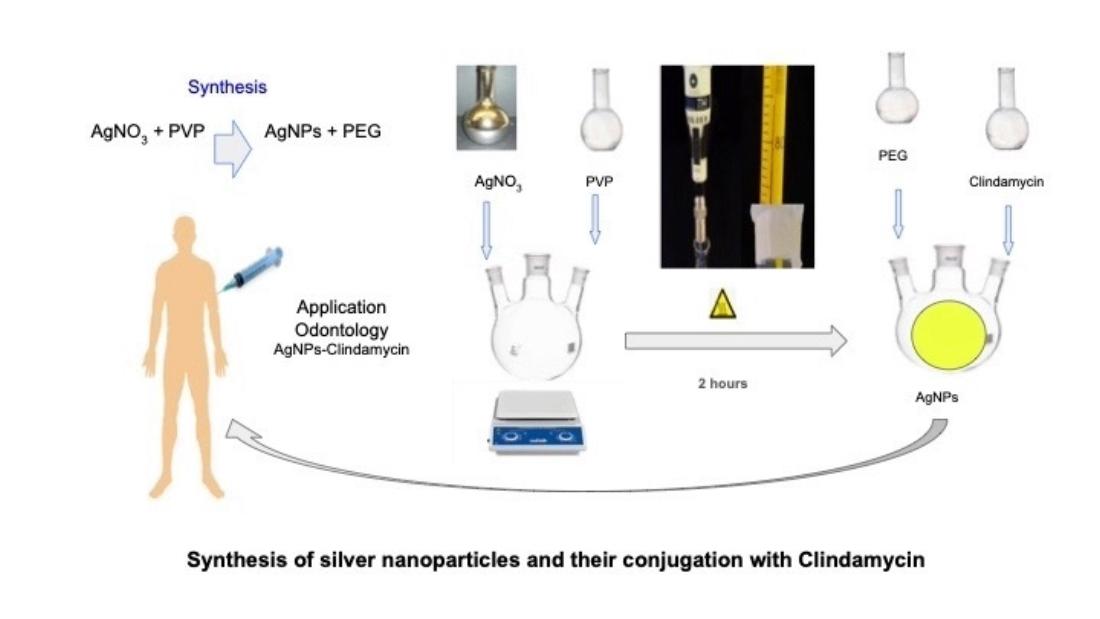

2.3. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

To carry out the synthesis of AgNPs, a stoichiometric amount of approximately 8 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) [

2,

12] was dissolved in a volume of 50 ml of deionized water, and an equivalent amount of polyethylene glycol (PEG) maintaining a 1:34 ratio with a solution of AgNO3 12 mM. The components were mixed and stirred by a magnetic stirrer for 5 minutes to obtain a homogeneous solution, based on the synthesis reported for Rigo and Saenz [

7,

9].

They were then sonicated for 30 minutes. After this, the solution was gradually heated at a rate of 2°C/minute until it reached a temperature of 85°C for 2 hours. The obtained solution was cooled to room temperature and the samples were measured in quartz cuvettes in a GENESYS 10S UV-Vis spectrophotometer in a wavelength range of 200 to 700 nm.

2.4. Formation of the Clindamycin-Silver Nanoparticle

The interaction of the drug with the silver nanoparticles was carried out by weighing 25 mg of standard clindamycin and bringing it to a volume of 100 ml using a volumetric flask. Stoichiometric quantities (2:1) were taken to make the nanoparticles react with the antibiotic and the solution was kept under stirring to allow the interaction of the substances for 3 hours. The identification of the absorption maximum of the formed AgNPs-Clindamycin complex could be appreciated by identifying the absorption spectrum of the compound.

2.5. UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

The reaction for the reduction of silver nitrate into silver ions (Ag+) that takes place in an aqueous medium was measured by taking samples of the synthesis to obtain a spectral scan to obtain the maximum absorbance of the sample of coated AgNPs and the wavelength where the characteristic resonance plasmon of the AgNPs [

9] was appreciated, in a range of 250 to 600 nm of wavelength.

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

As part of the characterization of the AgNPs, the analysis of the silver nanoparticles was performed by FT-IR to obtain spectrograms and measure wave interference in the form of vibrations at different wavelengths with an instrument that measures near-infrared radiation in the wavelength range of 400 to 4000/cm

-1 (Bruker Alpha P, source i with dividers for near IR), obtaining the corresponding spectra in the range of 800 to 4000 cm

-1 [

12].

2.7. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

To determine the particle size and zeta potential, the Zetasizer Nano ZS90 equipment from Malvern Panalytical was used. The analysis was carried out at a scattering angle of 90° and a temperature of 25 °C. Each sample was measured by triplicate, and all measurements were processed using zetasizer software. Nanoparticles were obtained in the range between 1 to 100 nm.

2.8. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

A Thermo Fisher Scientific Material Science Electron Microscope was used to determine the morphology of the silver nano spectrums. A magnification of 100,000X was used. The procedure followed voltage conditions of 200 kV using a typical Schottky field filament with an omega type column energy filter with a zirconium oxide coated tungsten filament at room temperature using a bright field digital camera. The diffraction pattern was followed in the image plane and in the focal plane in a condenser lens to obtain the image by this microscopic technique.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of the Nanoparticle

Figure 1 shows the results of the reduction reactions, the reaction that is carried out is tertiary amines such as 1-ethenyl, 1.vinyl-2-pyrrolidone (PVP) with reduced silver as the Ag

+ cation, result that is similar to that reported with the reduction reactions of polyethylene glycol and silver nitrate reported by Morales et al. [

8].

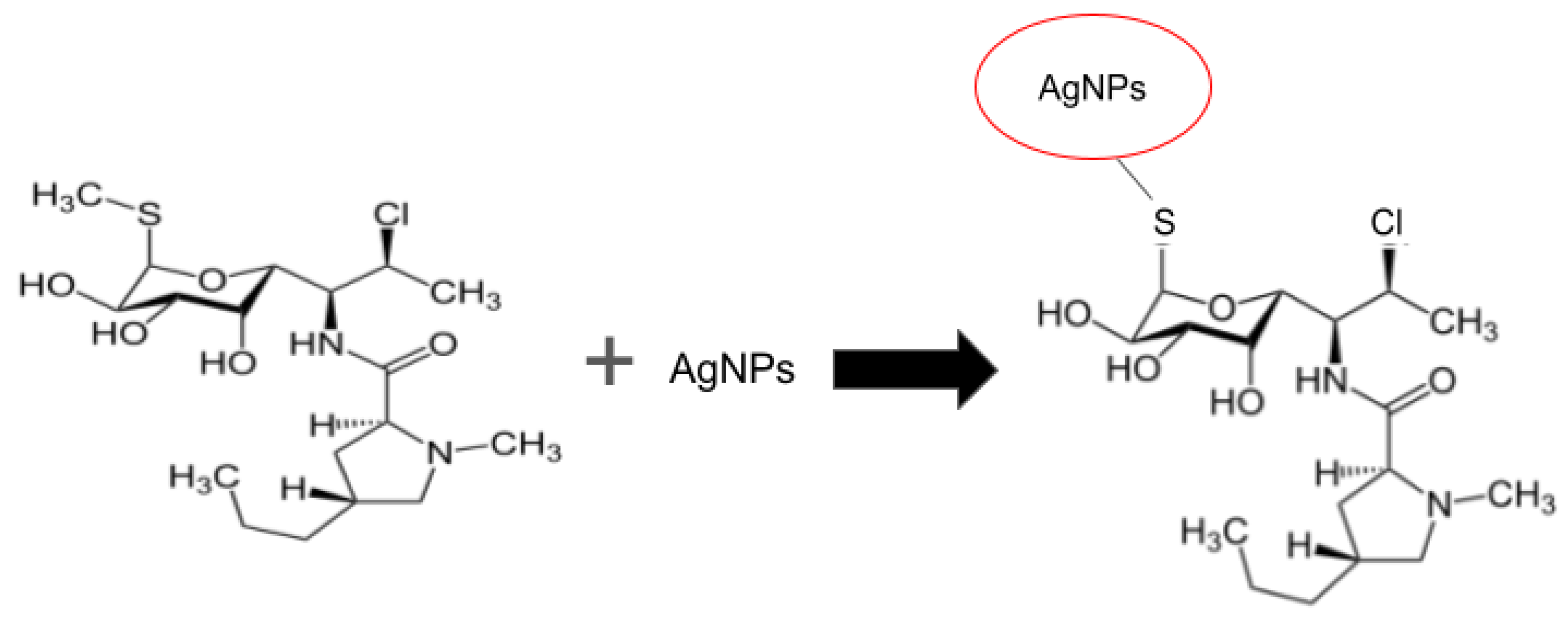

3.1.1. Formation of the Clindamycin-Silver Nanoparticle

Stoichiometric amounts were measured in the proportion 2:1 proportion to form the Clindamycin (1-methyl-4-propilpirrolidin-2-carboxamide) compound with silver nanoparticles.

Figure 2 showed the structures from the formed complex (AgNPs-Clindamycin).

3.2. UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

Figure 3 shows the results of the measurements carried out in the UV-Vis spectrophotometer of the silver nanospheres derived from the synthesis mediated by silver nitrate (AgNO

3) and 1-ethenyl, 1-vinyl-2- pyrrolidinone (PVP) as a reducing agent and polyethylene glycol as a complex stabilizer.

Figure 3 shows the absorption spectra of the obtained compounds indicating the maximum absorption of AgNPs characteristic of the resonance plasmon of the nanoparticles at a wavelength of 426 nm, the absorption spectrum of the AgNPs-clindamycin complex showing the maximum absorption peak at 443 nm and the absorption spectrum of the AgNPs-clindamycin complex showing the maximum absorption peak at 457 nm, obtained in a wavelength range of 245-600 nm (GENESYS UV-Vis Spectrophotometer). In the appendix A we shown the absorption espectral of solution of AgNPS.

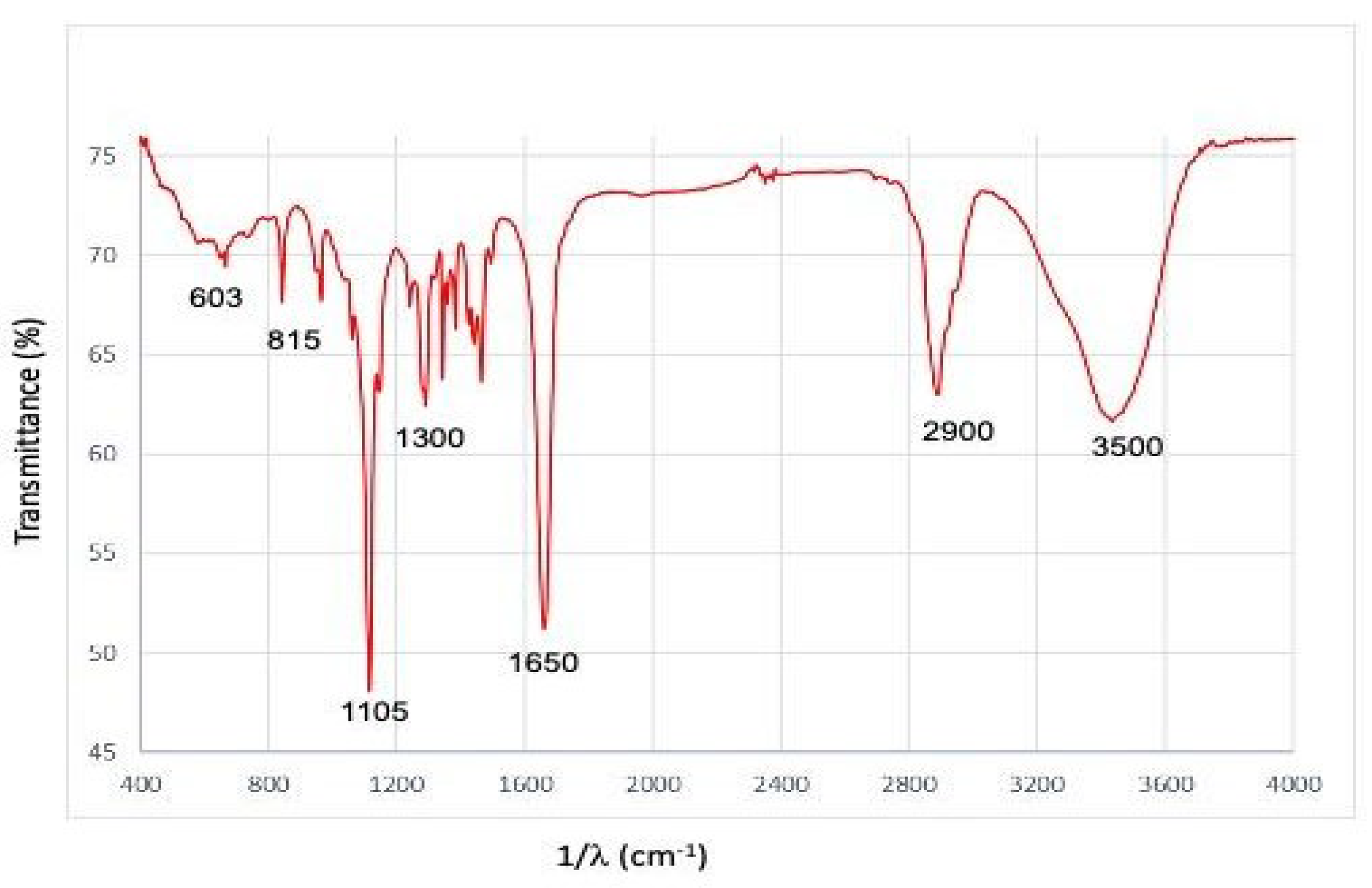

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Figure 4 shows the results of spectrograms that show the reduction process of silver infrared absorption spectra that show the reduction process of silver nitrate with polyvinylpyrrolidone.

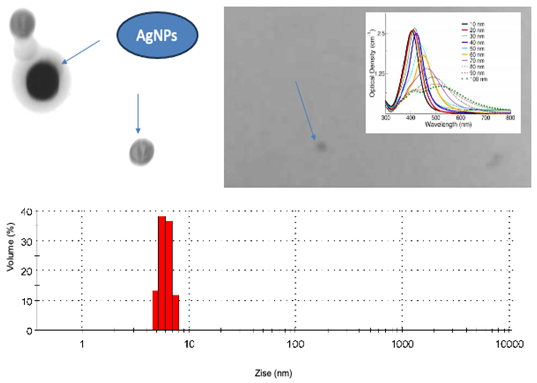

3.4. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

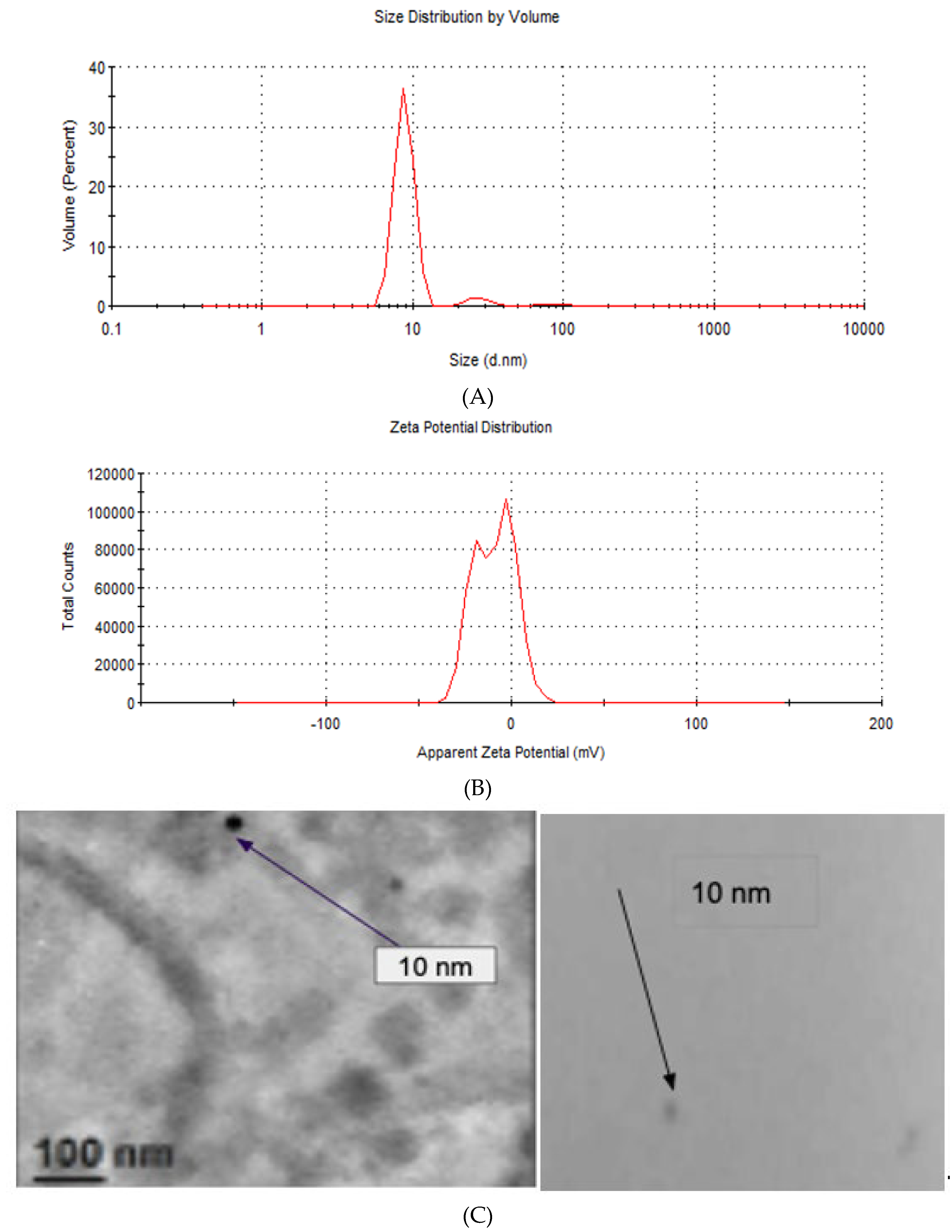

Figure 5 shows the particle size distribution of a monodisperse solution of silver nanoparticles. The particle size distribution of AgNPs shown in

Figure 5A, in

Figure 5B, the zeta potential also exhibits a bimodal distribution.

3.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM):

The

Figure 5C shows the size particle of AgNPs indicating with arrows the size (10 nm) obtained by electronic microscopy of one monodisperse solution of nanoparticles. The appendix B we shown the image the optical properties of AgNPs and the particle size.

4. Discussion

The synthesis of the nanoparticles of AgNPs was performed by silver nitrate reduction reactions at a temperature of 85 ºC, using 1-ethenyl, 1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone (PVP) as a reducing agent and poly(oxy-1, 2-ethanediyl), as an alpha-hydroxy-omega-hydroxy (PEG) stabilizing agent as shown in

Figure 1.

The Formation of the clindamycin-silver nanoparticles shown the reaction of silver nanoparticles with the antibiotic clindamycin results from the interaction of the positive charge of the silver nanoparticles and the negative charge of sulfur by displacing the CH3 methyl group and allowing the union of sulfur with the AgNPs.

For characterization with used the UV-vis spectrophotometry, the spectral compounds was identified for spectroscopy (

Figure 3), was obtained by the excitation of free electrons that gives rise to the characteristic resonance plasmon of AgNPs, although Figueroa et al. report the resonance plasmon at a wavelength of 410 nm using diaminosilver [

9,

10]. It is imperative to control the temperature in order to obtain monodisperse nanoparticles that facilitate rapid nucleation and optimal control of particle growth. In this instance, the temperature was maintained at 2°C for an initial period, before gradually increasing to 85°C for a duration of two hours. This process resulted in the formation of AgNPs with a size range of 10-40 nm. It is notable that at higher temperatures, the formation of smaller nanoparticles was observed. The peak of maximum absorption of the silver nanoparticles was identify to a wavelength of 426 nm (429nm,

Appendix A) and de complex AgNPs-clindamyicin was 443 nm y 457 nm.

The reaction of silver nanoparticles with the antibiotic clindamycin results from the interaction of the positive charge of the silver nanoparticles and the negative charge of sulfur by displacing the CH3 methyl group and allowing the union of sulfur with the AgNPs.

Silver nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) were synthesized using silver nitrate and 2-ethylene-1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone as precursors. The characterization of the AgNPs was conducted through the use of UV-visible spectrophotometry. The resonance plasmon was observed to occur at a maximum absorbance of 426 nm.

With regard to Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), we shown in the

Figure 4 the functional group characterized by infrared spectroscopy corresponding to the N-Ht atom bonds of amide groups identified at 3500 cm-1. The O-H functional group was identified with a stretch at 3400 cm-1. The peak located at a wavelength of 2900 cm-1 corresponds to a stretching of C-H bonds of sp3 hybridization, the band with a wave number of 1650 cm-1 corresponds to carbonyl groups of different functional groups.

The peak observed at wave number 1300 cm

-1 is indicative of the presence of O-H functional groups derived from carboxylates. The absorption peaks situated at 1105 cm

-1 are indicative of the stretching vibrations of primary amines C-N and sulfoxides S=O. The peak at 900 cm

-1 can be attributed to deformations of the C-H functional group. At 815 cm

-1, the N-H functional group of primary amines is identified, and the absorption peak at 603 cm

-1 can be associated with the C-H alkyne curve of sp3 hybridization, as proposed by Figueroa et al. [

10].

Measurements of Particle size and zeta potential indicated that the particle size distribution of AgNPs (

Figure 5A) exhibits a multimodal distribution, with three distinct peaks. The majority of particles exhibited a peak at 8.85 nm, a secondary peak at 27.75 nm, and a tertiary peak at 89.86 nm. The second and third peaks were notably less prevalent in the measured particle size ranges. This behavior indicates that the AgNPs are undergoing agglomeration. The observed agglomeration can be attributed to the relatively low zeta potential value of the AgNPs. As illustrated in

Figure 5B, the zeta potential also exhibits a bimodal distribution, with a peak at -19.7 mV, which is associated with the individual AgNPs, and a second peak at -3.53 mV, which is linked to the aggregates. This is because a higher absolute value of zeta potential correlates with enhanced stability against aggregation [

12,

13]. The figure 5C shows the size particle of AgNPs indicating with arrows the size (10 nm) obtained by electronic microscopy of one monodisperse solution of nanoparticles.

The hydrodynamic particle size was determined using the dynamic light scattering method, and a volume percentage of 40 was found at a temperature of 85°C, which was used for the synthesis. The particle size was found to be smaller than 100 nm, and a bimodal zeta potential pattern was found. It is therefore crucial to regulate the temperature during synthesis, as the particle size is dependent on temperature control. Furthermore, the synthesis method is straightforward, cost-effective, and environmentally benign. [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Finally with the samples obtained of nanoparticles could identify the image corresponding in the form of nanoparticles to the Transmission Electron Microscopy (

Appendix B). Silver nanoparticle solution samples were prepared as monolayers of a monodisperse solution and images were obtained as well-defined spherical shapes represented by the 10 nm diameter nanoparticles, indicated in

Figure 5C.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this work was to achieve a synthesis of silver nanoparticles from ecological material used in different drugs due to the physicochemical and ecological characteristics that the use of polyvinylpyrrolidone represents, it was a modified method and reported in the last century, but it is very simple, versatile, low cost and can easily be functionalized with antibiotics such as Clindamycin in order to increase the pharmaceutical and pharmacological properties of the antibiotic which has a wide use in medicine in its different pharmacological aspects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Molina-Trinidad E.; methodology, Castro-Olvera I., Molina-Trinidad E. and Jiménez-Alvarado R.; validation Ariza-Ortega A., Molina Trinidad E., Jiménez-Alvarado R. and Salas-Casas A..; formal analysis, Molina-Trinidad E. and Jiménez-Alvarado R.; investigation, Castro-Olvera I., Molina-Trinidad E.; resources, none; data curation, Castro-Olvera I., Molina-Trinidad E.; writing—original draft preparation, Molina-Trinidad E. and Jiménez-Alvarado R. ; writing—review and editing, Molina-Trinidad E.; visualization, Ariza-Ortega A., Molina Trinidad E., Jiménez-Alvarado R., Salas-Casas A., Monjáras-Ávila A., Baltazar-Téllez R.; and Moreno-Vite I.; supervision, Molina-Trinidad E.; project administration, none.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Funding is awarded by each author or other means if the article is accepted.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo and the federal youth program building the future.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Salguero, S.M.; Pilaquinga, F.F. Síntesis y caracterización de nanopartículas de plata preparadas con extracto acuoso de cilantro (Coriandrum sativum) y recubiertas con látex de Sangre de Drago (Croton lechleri). infoANALÍtica 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Carvajal, F.; Gonzalez-Soto, T.; Armenta-Calderón, A.D.; Méndez- Ibarra, R.; Esquer-Miranda, E.; Juarez, J.; Encinas-Basurto, D. Silver nanoparticles coated with chitosan against Fusarium oxysporum causing the tomato wilt. Biotecnia 2020, 22, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Njud, S. A.; Nehad S., A. Silver Nanoparticles Biosynthesized Using Azadirachta indica Fruit and Leaf Extracts: Optimization, Characterization, and Anticancer Activity. J Nanomat 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bretado-Aragón, L.A.; Jiménez-Mejía, R.; López-Meza, J.E.; Loeza-Lara, P.D. Composites of silver-chitosan nanoparticles: a potential source for new antimicrobial therapies. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Farmacéuticas 2016, 47, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, P. Nanopartículas de plata: obtención, utilización como antimicrobiano e impacto en el área de la salud. Rev Hosp Niños 2016, 58, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Munir, S.; Zeb, N.; Ullah, A.; Khan, B.; Ali, J.; et al. Green nanotechnology: a review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles - an ecofriendly approach. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigo, C.; Ferroni, L.; Tocco, I.; Roman, M.; Munivrana, I.; Gardin, C.; Zavan, B. Active silver nanoparticles for wound healing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, J.; Morán, J.; Quintana, M.; Estrada, W. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles by Sol-gel route from silver nitrate. Indian J Pharmacol 2009, 75, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Saenz, G.; Hernández, M.C.; Martínez, L. A. Síntesis acuosa de nanopartículas de plata. Revista Latinoamericana de Metalurgia y Materiales 2011, Suppl 3. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-López, K.J.; Torres-Vargas, O.L.; Prías-Barragán, J.J.; Ariza-Calderón, H. Optical and structural characterization of Allium sativum L. nanoparticles impregnate in bovine loin. Acta Agronómica 2015, 64, 1. [Google Scholar]

- López, I.I.; Vilchis, N.A.R.; Sánchez., M.V.; Ávalos, B.M. Obtención y caracterización de nanopartículas de plata soportadas en fibra de algodón. Superficies y vacío 2013, 26, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zea, A.J.L.; Talavera, N.M.E.; Arenas, Ch.C.; Pacheco, S.D.; Osorio, A.A.M.; Vera, G.C. Obtención y caracterización del nanocomposito: nanopartículas de plata y carboximetilquitosano (NpsAg-CMQ). Rev Soc Quím Perú 2019, 85, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel-Figueredo, R. de la C.; Mas-Diego, S.M. Biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles: review of potential use of Trichoderma species. Revista Cubana de Química 2021, 33, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tiarpa, T.; Ronnakorn, C.; Khanittha, P.; Benchamaporn, T.; Patcharee, P.; Surachet, T.; et al. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Gold Nanoparticles Used as Biosensors for the Detection of Human Serum Albumin-Diagnosed Kidney Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amr, H. H.; El-Sayyad, G.S. Antimicrobial and anticancer activities of biosynthesized bimetallic silver-zinc oxide nanoparticles (Ag-ZnO NPs) using pomegranate peel extract. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Necmettin, A.; Ayşe, B.; Mehmet, N. A.; Mehmet, F. B.; Cumali, K.; Mehmet Z., D.; et al. Biosynthesis of Black Mulberry Leaf Extract and Silver NanoParticles (AgNPs): Characterization, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity Applications. Journal of Applied Sciences. 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Akintelu, S.A.; Folorunso, A.S.; Folorunso, F.A.; Oyebamiji, A.K. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for biomedical application and environmental remediation. Heliyon. 2020, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N. S.; Alsubhi, N. S.; Felimban, A. I.; Alsubhi, N. S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using medicinal plants: Characterization and application. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2022, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Kumar, G.S.; Roy, H.; et al. From nature to nanomedicine: bioengineered metallic nanoparticles bridge the gap for medical applications. Discover Nano 2024, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).