Introduction

The origin of the term ’Space weather’ can be traced back to the mid-19th century when Sir John Herschel (Cade and Chan-Park, 2015) made significant contributions to understanding Solar meteorology through his work on the correlation between solar activities and their effects on Earth’s weather patterns. Later in the century, in 1859, the Carrington event (Riley et al., 2018) happened, which remains the most intense geomagnetic storm recorded to date. Consequently, global telegraph networks and communications disruption occurred; even fires were reported in telegraph stations. This event sparked the urgent necessity of understanding solar events and their science, eventually leading to the field of Space weather. Furthermore, the space between the planets and the Sun was considered empty until the 1950s when Eugene Parker theorised a model (Parker, n.d.) to predict how the Sun continuously releases streams of charged particles known as the Solar wind from its surface and how it interacts with every other planetary body in the solar system giving rise to space weather beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. This essay will explore the intricate components of space weather and its origin, the associated radiation and how it affects planetary bodies in the solar system.

The Sun and Its Structure

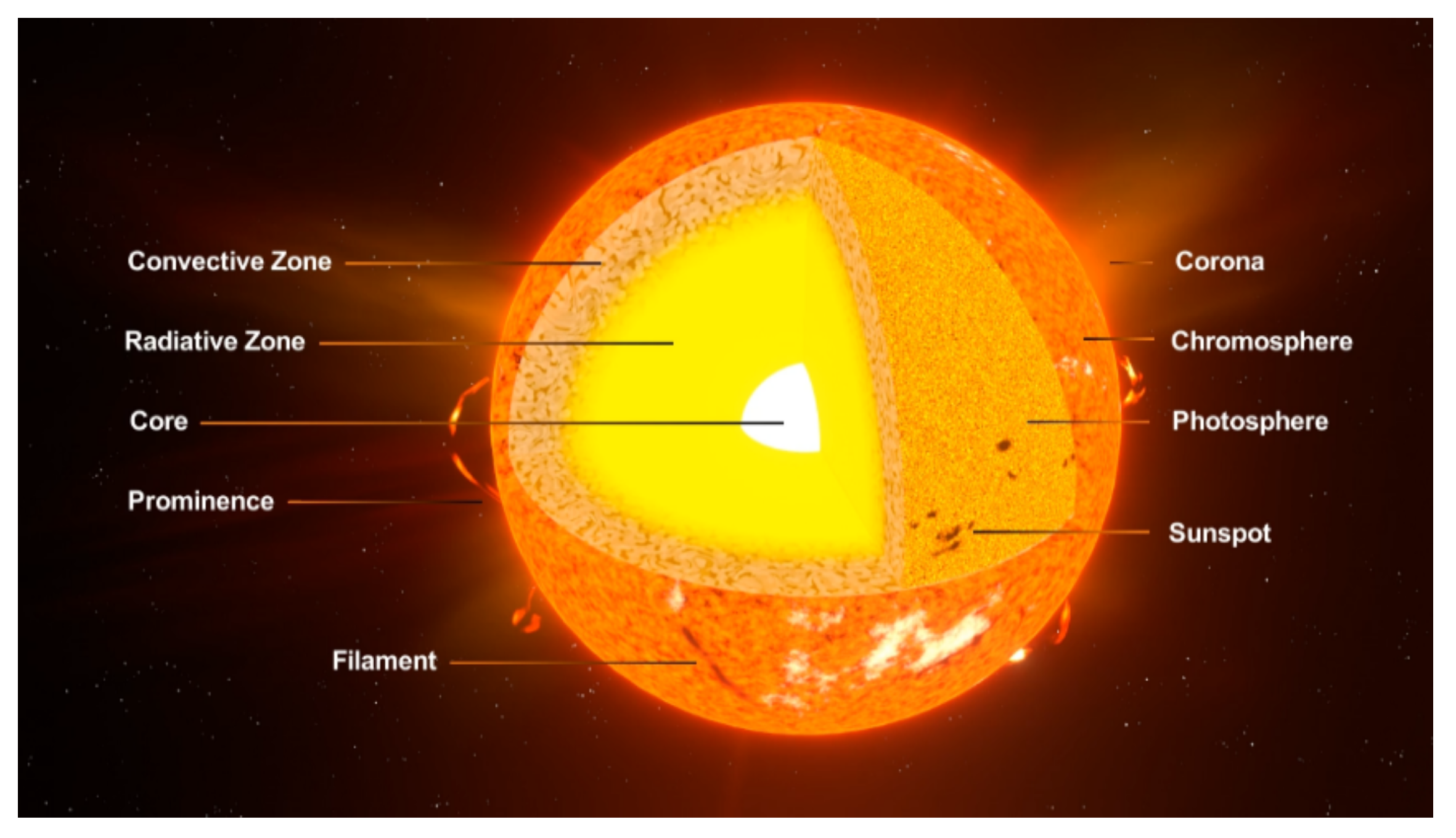

The Sun is the primary source of space weather in the solar system. Understanding the Sun’s mechanisms and solar activities provides a solid framework for understanding space weather. Like Earth or the Moon, the Sun comprises layers from core to surface. Sun’s core is the central and innermost region where hydrogen, under immense pressure and density, undergoes nuclear reactions to form helium. The core’s temperature is about 15,000,000°C, and the density is around 150 g/cm3 (NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015). Both factors gradually decrease from the core to the Sun’s Surface, and almost no nuclear burning is detected beyond the outer edge of the core, which is around 175,000 km from the centre.

A diagram of the layered structure of the sun is given below in

Figure 1. From the outer edge of the core starts the

Radiative zone, where the energy generated from the nuclear reactions from the core is transported outwards in the form of radiation

(NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015). Energy in the form of photons bounces through the dense plasma and can even take millions of years to reach the next layer, the thin interface layer. The

Interface layer, called the

tachocline, lies between the radiative and the convective zone. The

convective zone, where hot plasma rises from the interior, cools at the surface, and sinks back down, creating a cycle of heat transport

(NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015). These form Granules, cell-like structures observed on the Sun’s surface due to rapid heat transport. Depth of this zone extends up to 200,000 km right to the visible surface. Beyond this zone is the

Photosphere, the Sun’s visible surface, about 100 km thick

(NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015). Sunspots, cooler regions on the photosphere caused by magnetic activities, can be observed from this layer, which is the visible surface. Above the photosphere is the

Chromosphere, where temperature can rise from 6000°C to 20000°C, where H

2 emission lines produce a reddish colour that can be observed in Solar prominences, which are dense clouds of material suspended by loops of magnetic field on the Sun’s Surface. Other features like filaments, dark thread-like structures, and the Chromospheric network, which are web-like patterns, can be observed in this layer. After this, a transition region, a thin and irregular layer, separates the cooler Chromosphere and the hotter Corona

(NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015). Rapid temperature change from 1,000,000°C to 20,000°C is observed in this region as the heat flows down from the Corona to the Chromosphere. The Corona is the Sun’s outermost layer visible during the solar eclipse. Corona’s temperature can reach millions of degrees Celsius and has the least density. Due to its high temperature, hydrogen and helium are all stripped of their electron, and the Sun’s gravity cannot hold these particles. Corona is the source of

Solar wind that streams off in every direction from the Sun at speeds ranging from 300 km/s to 800 km/s

(NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015), forming a continuous stream of charged particles, primarily protons and electrons.

The Components of Space Weather

The Solar wind is one of the most critical components of the Space weather in the solar system. The presence of solar wind gradually diminishes as it moves further away from the sun. The boundary where the solar wind interacts with the interstellar medium is heliopause around 100 AU away, the solar system’s edge beyond which the sun’s magnetic field and solar wind influence wane, and the interstellar medium becomes dominant. However, solar wind is not the only space weather element contributing to the solar system. Other phenomena of the Sun include Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), Solar flares, Solar Energetic Particles (SEP) events, as well as the Galactic Cosmic Rays (GCRs) from interstellar medium constantly bombarding the solar system contribute significantly to the overall space weather (Schwenn, n.d.).

CMEs are massive eruptions of plasma materials and magnetic fields from the Sun’s outermost surface, the Corona. They often originate from highly twisted magnetic field structures called Flux ropes in the Sun’s lower Corona undergoing magnetic reconnection, transitioning from an unstable configuration to a less tense configuration. This sudden realignment releases electromagnetic energy concurrent with the rapid acceleration of plasma away from the Sun, forming the CMEs. A CME can eject billions of tons of coronal materials made of plasma and magnetic field (Schwenn, n.d.), propagating from 250 km/s to 3000 km/s, depending on ejection intensity, towards the rest of the solar system; the size of CMEs expands as they propagate away from the Sun and interact with every planetary body, its magnetic fields, and the atmosphere along the way, including Earth, Jupiter, and heliopause. Like CMEs, solar flares occur in active regions of strong magnetic fields, which can also be correlated with sunspots. These flares are intense bursts of radiation and energy from the Sun’s surface from the sudden release of magnetic energy from the solar atmosphere. Intense solar flares can be a significant hazard as they interact with the earth’s ionosphere and magnetosphere, causing potential radio blackouts. Alongside these two phenomena, SEP is high energy charged particles, primarily protons and electrons, that can occur suddenly and contribute to rapidly changing the radiation environment within the solar system (Schwenn, n.d.). These particles, coupled with CMEs or solar flares, are accelerated to near or relativistic speeds that can create hazardous conditions in near-Earth space and the lunar surface. Sun is the source for most of these, unlike GCRs, which are high-energy particles that originate outside the solar system and are likely to be formed by Supernova explosion events. These particles are high energy in nature, travel near light speed, and can interact and get influenced by the magnetic fields of the planetary bodies within the solar system (Montesinos et al., 2021). The roughly 11-year solar cycle also plays a vital role in modulating GCR particles entering the solar system. These particles are also influenced by and interact with solar particles and the associated magnetic fields. Observations showed more GCR particles enter the heliosphere near solar minimum due to low CME activities and weaker solar winds. Meanwhile, the opposite happens during solar maximum due to more solar activities and stronger solar winds (Paouris et al., 2012). Thus, each component contributes significantly to the weather conditions in the near-Earth space environment and every other planetary body within the solar system.

Space Radiation and Its Impact on Planetary Bodies in the Solar System

The space radiation associated with the events discussed above is electromagnetic radiation, primarily atoms being stripped away of their electrons, and only the nucleus of the atoms remains. Space radiation can be ionizing or non-ionizing, depending on the particles’ energy and capacity to remove another electron from their orbit. Ionizing radiation is high-energy radiation that falls into the spectrum from Very High Ultraviolet rays, X-rays, and Gamma rays, including Alpha particles and solar energetic particles, which can cause more significant damage, creating secondary particles in the process. Non-ionizing radiation is much lower in energy and falls in the spectrum of radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, and Ultraviolet range, and is considered much less damaging (Cucinotta, 2024).

All these radiation exposures impact the chemistry and mineralogy of planetary bodies. Space weathering is one of the phenomena that can be detected on planetary body surfaces, including asteroids and comets. It is defined as Solar and cosmic-inducted chemical alterations of surface minerals leading to new mineral phases through irradiation, thermal processes, and surface roughening. Long periods of space weathering, majorly from continuous solar wind interactions, can contribute to the formation and evolution of planetary regolith and impact its composition and particle sizes

(Bottke et al.

, 2002). Weathering can also affect the distribution and stability of volatile elements and compounds on planetary surfaces. For instance,

water ice and CO

2 release caused by solar radiation and thermal cycling on different planetary body surfaces, contributing to permanent surface morphology changes

(Bennett et al.

, 2013). Solar radiation and GCRs also interact with the magnetic fields of different planetary bodies such as Earth, Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Uranus, and its satellites in various ways, giving rise to complex magnetic field processes. These charged particles interact with the planetary magnetic field, creating the

Auroras, incredible light formations around the atmospheres observed on many planetary bodies

(Newell et al.

, 2001). This illustrates the presence of space weather throughout the entire solar system. In extreme cases, CMEs or SEP events can contribute to sizeable atmospheric loss by accelerating particles from the solar wind and stripping away particles from the outer layers of the atmosphere in a process called

Sputtering (Williams, 1979). Planetary bodies with no or little magnetic field and atmosphere are more likely to be impacted by space weathering. Over a billion years, it can cause significant damage to the atmosphere. This effect may have been a major contributor to the loss of the

Martian atmosphere over time, even though there is no total picture of how Mars lost most of its atmosphere

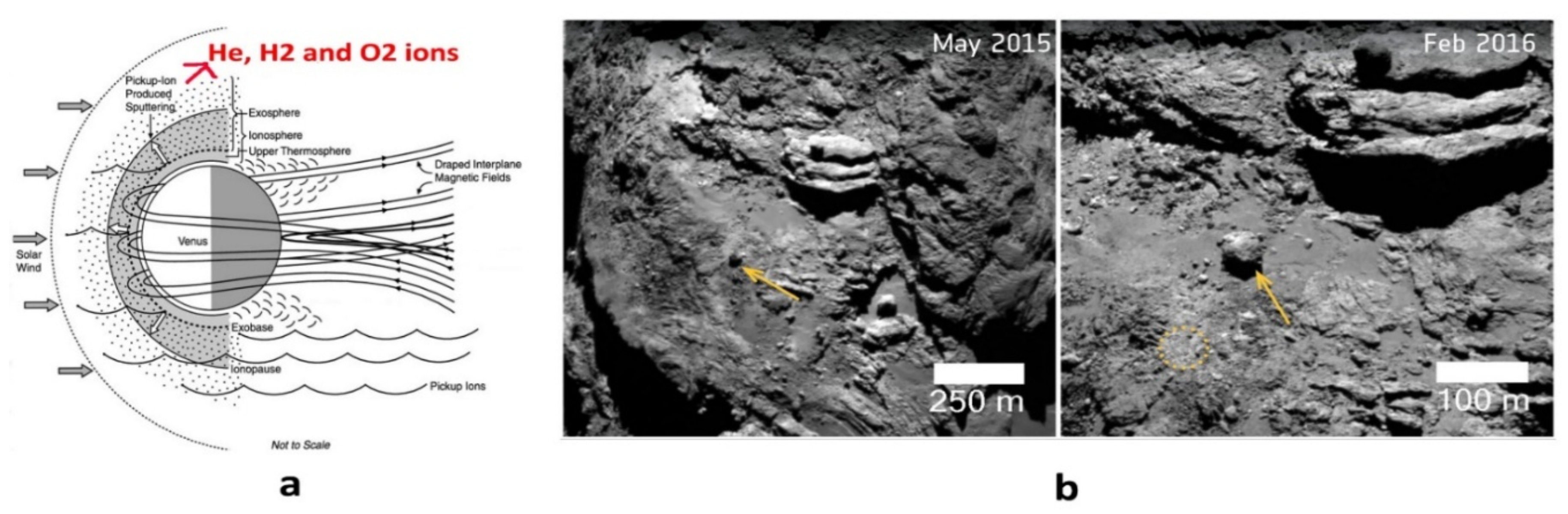

(Chassefière and Leblanc, 2004). Similarly, solar wind and the upper atmospheric layer of

Venus interact intensely, leading to the loss of volatile elements like He, H

2 and O

2 in the form of

ionized particles (

Figure 2. a), confirmed by the

Venus Express mission

(Futaana et al.

, 2017). Another instance detailing the interaction between Solar wind and a Comet,

67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from the

Rosetta mission

(El-Maarry et al., 2019), shed light on space weather processes of smaller bodies (

Figure 2. b). The Sun’s heat releases water ions in the comet’s atmosphere from the water molecules formed from its surface ice. UV rays and solar winds break these molecules into ions by stripping off their electrons. The solar wind can accelerate these water ions outwards to space, but some ions strike the comet’s surface, displacing atoms from the comet’s surface. These few examples demonstrate how intricate space weather processes are and how they impact every planetary body, from the inner solar system to the heliopause.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our understanding of space weather has grown exponentially since the Carrington Event. The Sun and its complex activities are the solar system’s primary source of space weather. Every solar phenomenon, from CMEs and solar flares to SEPs, contributes to the dynamic space environment coupled with the GCRs coming from the interstellar medium into the heliosphere. The impact of space weather extends beyond the planets, affecting comets and asteroids to the heliosphere’s edge. Space radiation associated with solar events and GCRs interacts significantly with the planetary bodies, which can effectively induce chemical and morphological alterations of planetary surfaces with time and intensity scales. The observations about solar wind interaction discussed on different bodies such as Mars, Venus, and Comet 67P/C-G show how our knowledge of space weather processes is critical to assessing space exploration and habitability of the other planetary bodies within the solar system. It will help mitigate the risks of human space missions and develop more durable spacecraft and instrumentations from radiation and solar events, eventually helping to explore and unravel more insights about space weather and radiation processes.

References

- Bennett, C.J., Pirim, C., Orlando, T.M., 2013. Space-Weathering of Solar System Bodies: A Laboratory Perspective. Chem. Rev. 113, 9086–9150. [CrossRef]

- Bottke, W.F., Cellino, A., Paolicchi, P., Binzel, R.P. (Eds.), 2002. Asteroids III. University of Arizona Press. [CrossRef]

- Cade, W.B., Chan-Park, C., 2015. The Origin of “Space Weather.” Space Weather 13, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Chassefière, E. , Leblanc, F., 2004. Mars atmospheric escape and evolution; interaction with the solar wind. Planet. Space Sci. 52, 1039–1058. [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A., 2024. Non-targeted effects and space radiation risks for astronauts on multiple International Space Station and lunar missions. Life Sci. Space Res. 40, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- El-Maarry, M.R., Groussin, O., Keller, H.U., Thomas, N., Vincent, J.-B., Mottola, S., Pajola, M., Otto, K., Herny, C., Krasilnikov, S., 2019. Surface Morphology of Comets and Associated Evolutionary Processes: A Review of Rosetta’s Observations of 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. Space Sci. Rev. 215, 36. [CrossRef]

- Futaana, Y., Stenberg Wieser, G., Barabash, S., Luhmann, J.G., 2017. Solar Wind Interaction and Impact on the Venus Atmosphere. Space Sci. Rev. 212, 1453–1509. [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, C.A., Khalid, R., Cristea, O., Greenberger, J.S., Epperly, M.W., Lemon, J.A., Boreham, D.R., Popov, D., Gorthi, G., Ramkumar, N., Jones, J.A., 2021. Space Radiation Protection Countermeasures in Microgravity and Planetary Exploration. Life 11, 829. [CrossRef]

- NASA/Marshall Solar Physics, 2015. The Solar Interior. URL https://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/interior.shtml.

- Newell, P.T., Greenwald, R.A., Ruohoniemi, J.M., 2001. The role of the ionosphere in aurora and space weather. Rev. Geophys. 39, 137–149. [CrossRef]

- Paouris, E., Mavromichalaki, H., Belov, A., Gushchina, R., Yanke, V., 2012. Galactic Cosmic Ray Modulation and the Last Solar Minimum. Sol. Phys. 280, 255–271. [CrossRef]

- Parker, E.N., n.d. Bulletin of the AAS • Vol. 54, Issue 1 (Obituaries, News & Commentaries, Community Reports) 54.

- Riley, P., Baker, D., Liu, Y.D., Verronen, P., Singer, H., Güdel, M., 2018. Extreme Space Weather Events: From Cradle to Grave. Space Sci. Rev. 214, 21. [CrossRef]

- Schwenn, R., n.d. Space Weather: The Solar Perspective.

- Williams, P., 1979. The sputtering process and sputtered ion emission. Surf. Sci. 90, 588–634. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).