Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

29 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

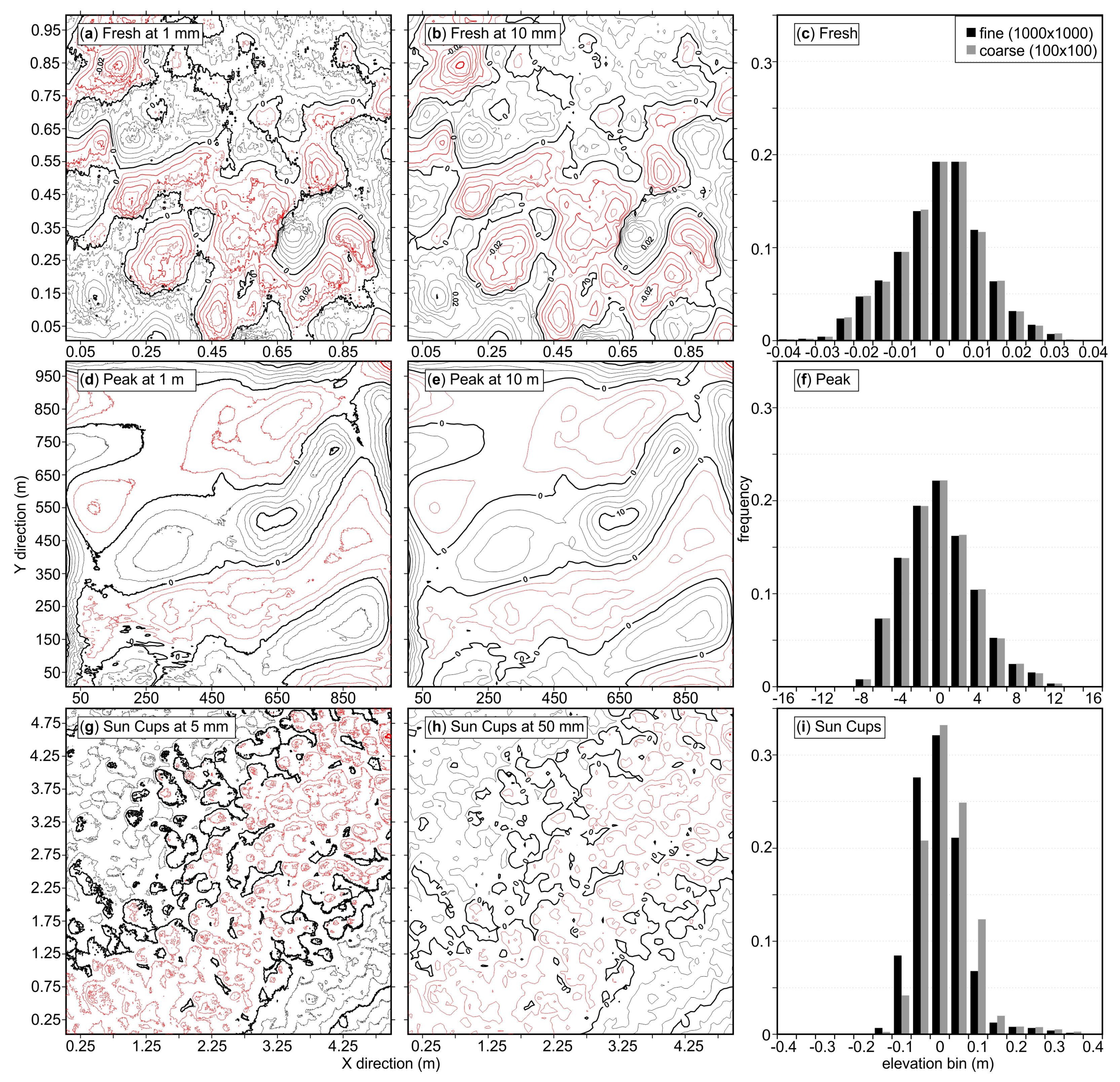

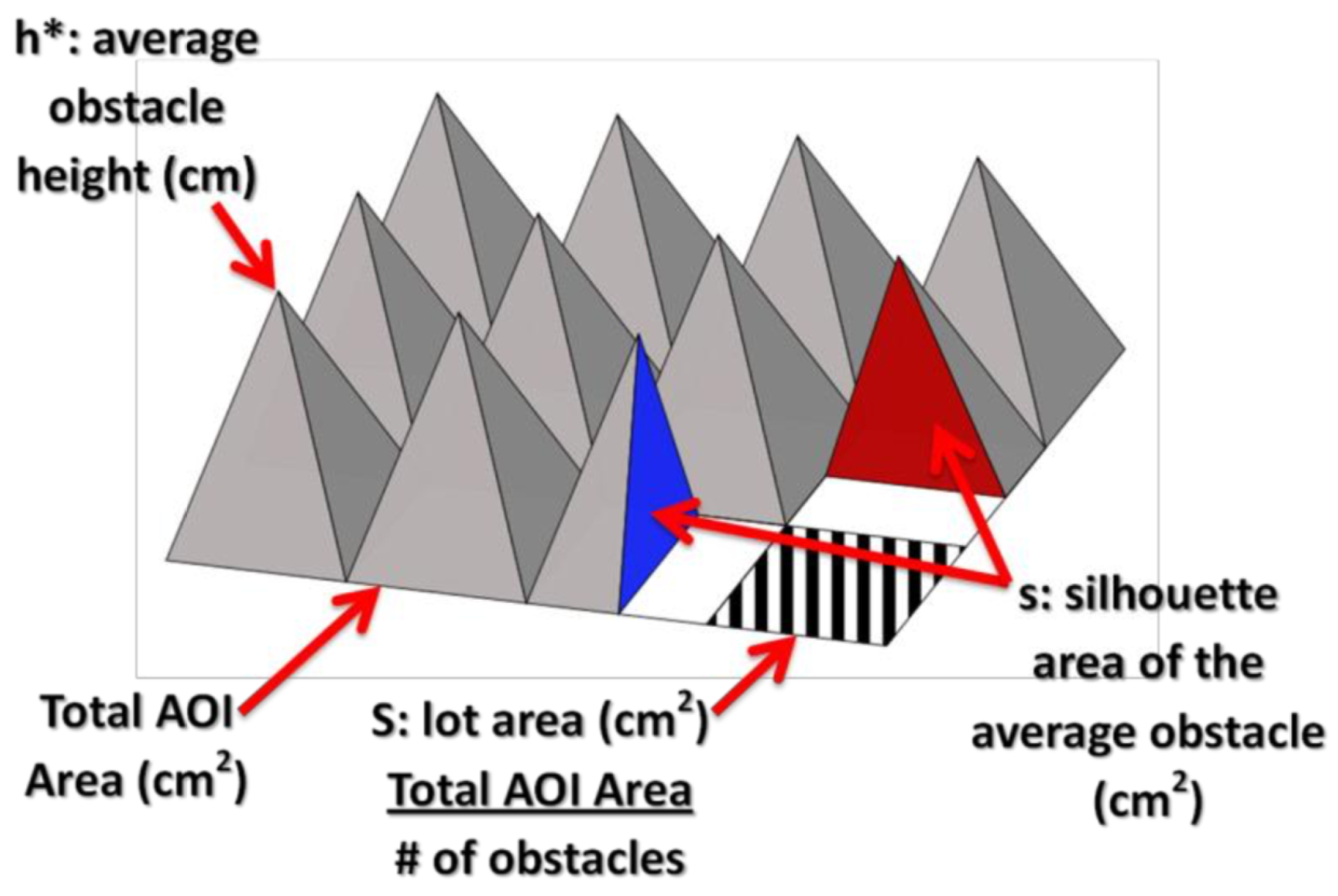

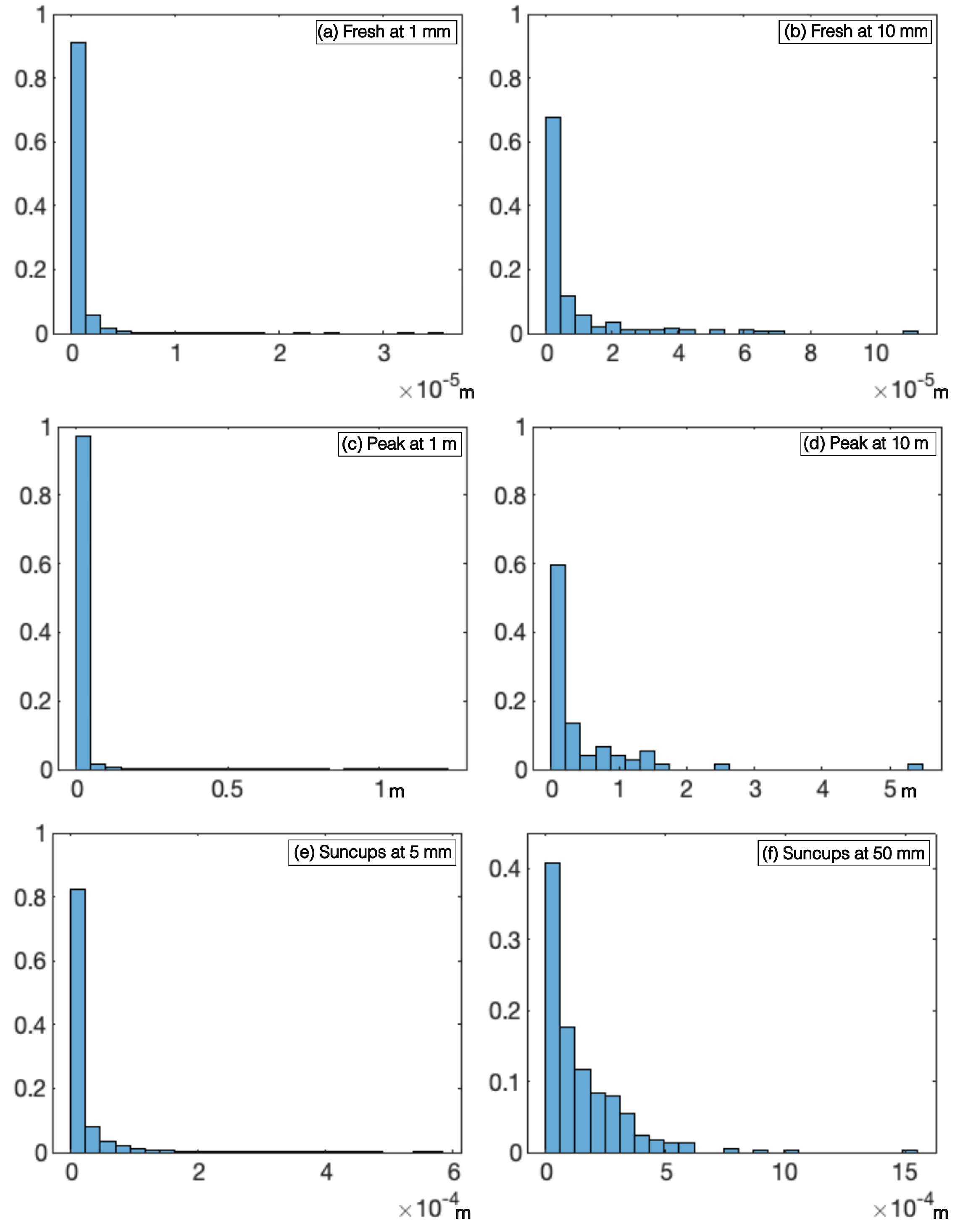

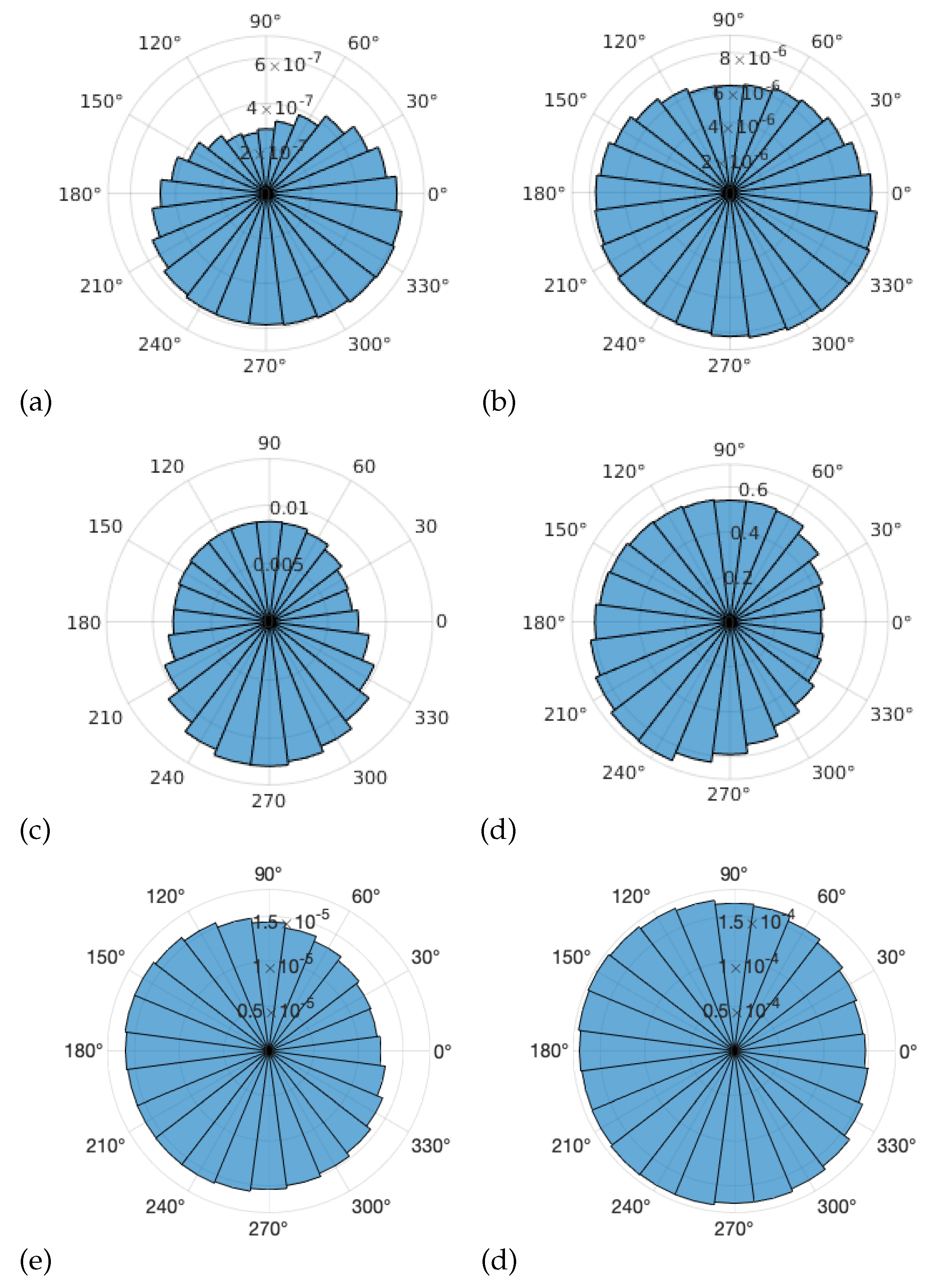

2.1. Segmentation into Roughness Elements

2.2. Computing Areas and Heights

2.3. Smoothing of the Surface

3. Datasets and Preparation

3.1. Snow Surface Datasets

3.2. Data Preparation

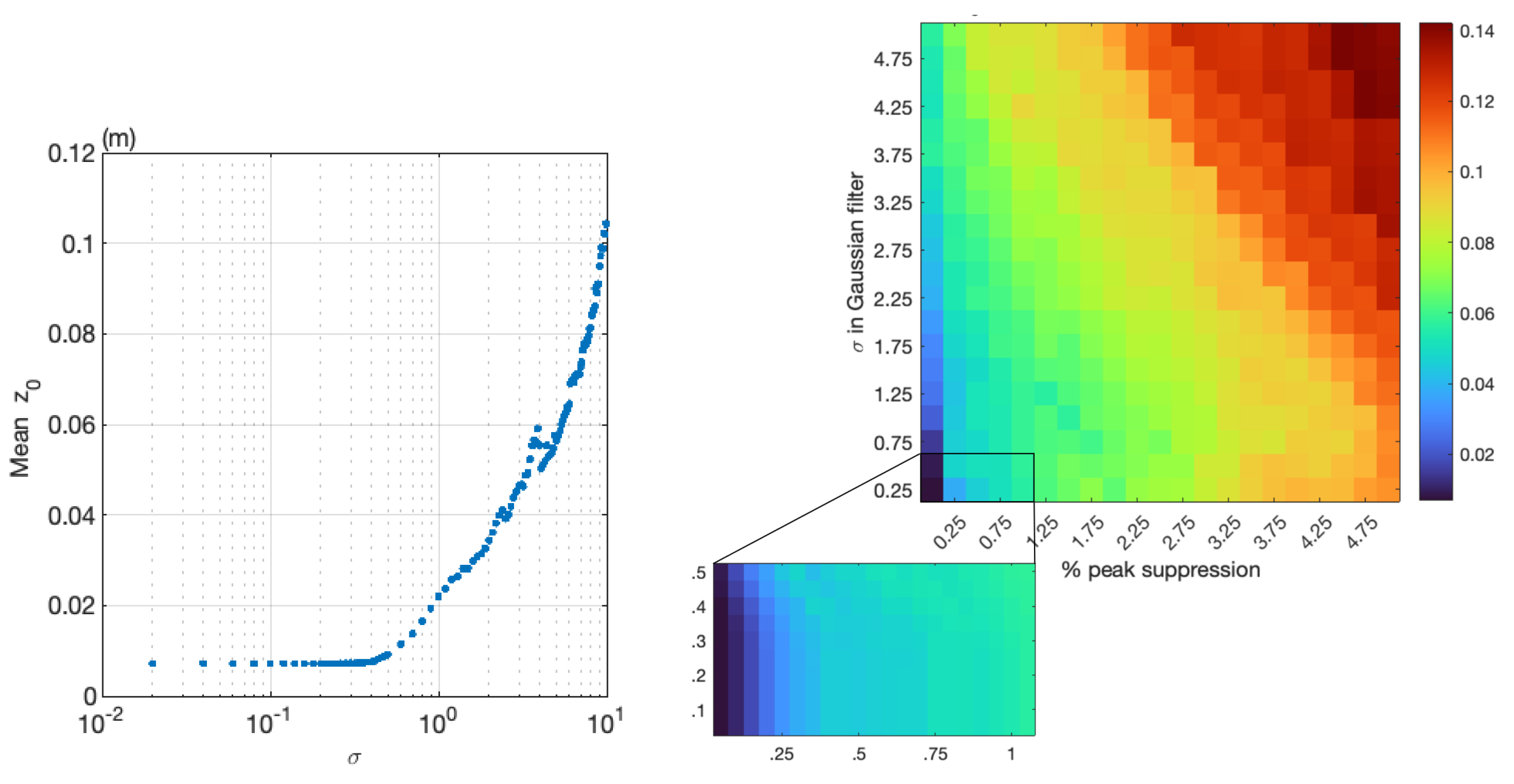

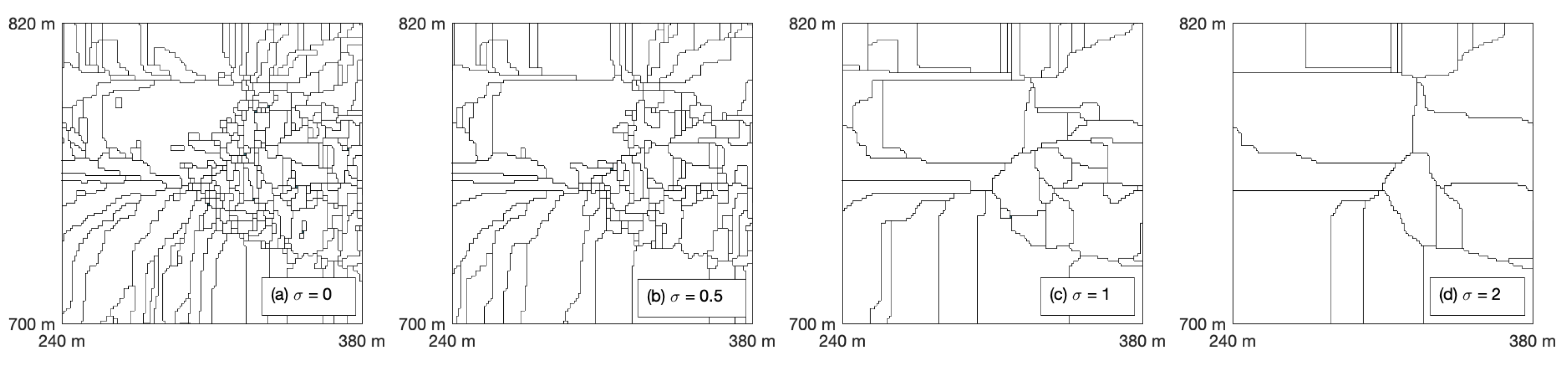

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOI is the area of interest |

| h is the average vertical extent or effective obstacle height, measured in cm |

| s is the silhouette area of the average obstacle, measured in cm2 |

| S is the specific area or lot area, measured in cm2 |

| is the (geometric) aerodynamic roughness length, measured in m |

References

- Mialon, A.; Fily, M.; Royer, A. Seasonal snow cover extent from microwave remote sensing data: Comparison with existing ground and satellite based measurements. EARSeL eProceedings 1994, 4, 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Musselman, K.N. , Clark, M.P., Liu, C., Ikeda, C., Rasmussen, R. Slower snowmelt in a warmer world. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, E.S. , Steiner, J.F., Brun, F. Highly variable aerodynamic roughness length for a hummocky debris-covered glacier. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2017, 122, 8447–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, E. Parameterizing scalar transfer over snow and ice: a review. Journal of Hydrometeorology 2002, 3(4), 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromke, C.; Manes, C.; Walter, B.; Lehning, M.; Guala, M. Aerodynamic roughness length of fresh snow. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2011, 141 (1), 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W. Roughness in the earth sciences. Earth Science Reviews 2014, 136, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, E. L. A theory for the scalar roughness and the scalar transfer coefficients over snow and sea ice. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 1987, 38 (1–2), 159–184. [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, S. R.; Williams, M. W.; Corrao, M. V. Changes in the surface roughness of snow from millimetre to metre scales. Ecological Complexity 2009, 6(3), 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukko, A.; Anttila, K.; Manninen, T.; Kaasalainen, S.; Kaartinen, H. Snow surface roughness from mobile laser scanning data. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2013, 96, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravleva, T.B. , Kokhanovsky, A. Influence of surface roughness on the reflective properties of snow. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 2011, 112(8), 1352–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amory, C.; Naaim-Bouvet, F.; Gallee, H.; Vignon, E. Brief communication: Two well-marked cases of aerodynamic adjustment of sastrugi. The Cryosphere 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, C.W., Fletcher, C.G. Snow albedo feedback: Current knowledge, importance, outstanding issues and future directions. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2016, 40 (3). [CrossRef]

- Lettau, H. Note on aerodynamic roughness-parameter estimation on the basis of roughness-element description. Journal of Applied Meteorology 1969, 8, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, D. S. Surface roughness and bulk heat transfer on a glacier: comparison with eddy correlation. Journal of Glaciology 1989, 35(121), 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, B.; Willis, I.; Sharp, M. Measurement and parameterization of aerodynamic roughness length variations at Haut Glacier d’Arolla, Switzerland. Journal of Glaciology 2006, 52(177), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, S. R. Temporal changes in small scale snowpack surface roughness length for sublimation estimates in hydrological modelling. Cuadernos De Investigación Geográfica 2010, 36 (1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Sanow, J.E.; Fassnacht, S.R.; Suzuki, K. How does a dynamic surface roughness affect snowpack modelling? Polar Science 2024, 41(1-2). [CrossRef]

- Sanow, J.E. , Fassnacht, S.R., Kamin, D.J., Sexstone, G.A., Bauerle, W.L., Oprea, I. Geometric versus anemometric surface roughness for a shallow accumulating snowpack. Geosciences 2018, 8(12), 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, J.L.; Hayashi, M. Assessing the application of a laser rangefinder for determining snow depth in inaccessible alpine terrain. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2010, 14(6), pp.901-910.

- Nolan, M.; Larsen, C.; Sturm, M. Mapping snow depth from manned aircraft on landscape scales at centimeter resolution using structure-from-motion photogrammetry. The Cryosphere 2015, 9(4), pp.1445-1463.

- Jacobson, M.Z. Fundamentals of atmospheric modeling., 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, Great Britain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, F. Topographic distance and watershed lines. Signal processing 1994, 38(1), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia of Mathematics: Rodrigues formula. Available online: https://encyclopediaofmath.org/wiki/Rodrigues formula (accessed on 30 December, 2024).

- Winstral, A.; Elder, K.; Davis, R. E. Spatial snow modeling of wind-redistributed snow using terrain-based parameters. Journal of Hydrometeorology 2002, 3(5), 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J.B. Whitebox GAT: A case study in geomorphometric analysis. Computers & Geosciences, 2016 95, 75-84. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J. B.; Francioni, A.; Cockburn, J. M. H. LiDAR DEM Smoothing and the Preservation of Drainage Features. Remote Sensing 2016, 11(16), 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, G. L., Saby, L., Band, L. E., & Goodall, J. L. Effects of LiDAR DEM smoothing and conditioning techniques on a topography-based wetland identification model. Water Resources Research,2019, 55(5), 4343-4363.

- Erdbrügger, J., van Meerveld, I., Bishop, K.,Seibert, J. Effect of DEM-smoothing and-aggregation on topographically-based flow directions and catchment boundaries. Journal of Hydrology, 2021, 602, 126717.

- Whitebox Tools. Available online: https://www.whiteboxgeo.com/.

- Conrad, O., Bechtel, B., Bock, M., Dietrich, H., Fischer, E., Gerlitz, L., Wehberg, J., Wichmann, V., and Böhner, J.: System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) v. 2.1.4, Geosci. Model Dev., 2015 8, 1991-2007. [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks, Inc. Imhin Documentation. mathworks.com. Accessed: October 5, 2024. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/images/ref/imhmin.html.

- CloudCompare. Available online: https://www.danielgm.net/cc/ (accessed on 30 December, 2024).

- Harpold, A. A.; et al. LiDAR-derived snowpack data sets from mixed conifer forests across the Western United States. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 50, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, S.R.; Sanow, J.E. Fresh Snow and Ablation-Sun Cup Snow Surface Datasets for Evaluation of Geometry Aerodynamic Roughness Code [Dataset]. Dryad 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, S. R.; Stednick, J. D.; Deems, J. S.; Corrao, M. V. Metrics for assessing snow surface roughness from digital imagery. Water Resources Research 2009, 45, W00D31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden Software – Surfer. Available online: https://www.goldensoftware.com/products/surfer/ (accessed on 30 December, 2024).

- Sexstone, G. A.; Fassnacht, S. R.; López-Moreno, J. I.; Hiemstra, C. A. Subgrid snow depth coefficient of variation spanning alpine to sub-alpine mountainous terrain. Cuadernos de Investigación Geográfica/Geographical Research Letters 2022, 48(1), 79-96. [CrossRef]

- Winstral, A; Marks D. Simulating wind fields and snow redistribution using terrain-based parameters to model snow accumulation and melt over a semi-arid mountain catchment. Hydrological Processes 2002, 16(18), 3585-603. [CrossRef]

- Moron, V.; Robertson, A.W.; Qian, J.-H.; Ghil, M. (2015). Weather types across the Maritime Continent: from the diurnal cycle to interannual variations. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 2, 65 [. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counihan, J. Wind tunnel determination of the roughness length as a function of the fetch and the roughness density of three-dimensional roughness elements. Atmos. Environ. 1971, 5, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R.W.; Griffiths, R.F.; Hall, D.J. An improved method for the estimation of surface roughness of obstacle arrays. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nield, J.M.; King, J.; Wiggs, G.F.; Leyland, J.; Bryant, R.G.; Chiverrell, R.C.; Darby, S.E.; Eckardt, F.D.; Thomas, D.S.; Vircavs, L.H.; Washington, R. Estimating aerodynamic roughness over complex surface terrain. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2013, 118(23), pp.12-948. [CrossRef]

- Revuelto, J.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Azorín-Molina, C.; Zabalza, J.; Arguedas, G.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. Mapping the annual evolution of snow depth in a small catchment in the Pyrenees using the long-range terrestrial laser scanning. Journal of Maps 2014, 10(3), pp.379-393. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Larsen, C.; Sturm, M. Mapping snow depth from manned aircraft on landscape scales at centimeter resolution using structure-from-motion photogrammetry. The Cryosphere 2015, 9, 1445–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revuelto, J.; Alonso-Gonzalez, E.; Vidaller-Gayan, I.; Lacroix, E.; Izagirre, E.; Rodríguez-López, G.; López-Moreno, J.I. Intercomparison of UAV platforms for mapping snow depth distribution in complex alpine terrain. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2021, 190, p103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, E.L. A relationship between the aerodynamic and physical roughness of winter sea ice. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- z0 Lettau LiDAR Watershed Code. [GitHub Repository] Available online: https://github.com/rneville/Z0-Lettau-LiDAR-Watershed 2025.

| dataset | fresh snow | peak accumulation | ablation - sun cups |

|---|---|---|---|

| short name/code | FS-FC | PA-NS | SC-PH |

| location | Fort Collins | Niwot Saddle | Poudre headwaters |

| latitude, longitude | 40.6, -105.1 | 40.0547, -105.5890 | 40.4396, -105.7739 |

| date acquired | 19 April 2021 | 20 May 2010 | 13 June 2017 |

| resolution (m) | 0.001 | 1 | 0.05 |

| surface | fresh snow | - | peak accumulation | - | ablation - sun cups | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| resolution (m) | 0.001 | 0.010 | 1 | 10 | 0.005 | 0.050 |

| elements | 7366 | 195 | 21090 | 74 | 36259 | 380 |

| mean (x) | 0.00054 | 0.0075 | 9.4 | 421 | 0.012 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).