1. Introduction

Landslides are mass movements of rock, soil, or debris driven by gravitational forces, particularly in highland areas. They can be classified on the basis of movements (fall, topple, slide, spread, flow, or slope deformation), materials involved (rock, earth, debris, or mud), and the velocity of movement [

1,

2,

3]. Some landslides occur gradually, such as solifluction, soil creep, or slumping, while others happen rapidly, including mudflows, debris flows, and rockfalls. The speed and nature of movement are influenced by factors such as water content, slope angle, and grain size distribution [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Landslides can lead to severe consequences, posing significant threats to human lives and property [

8,

9].

Landslide is normally caused by natural factors such as geological structure, moisture, rainfall or vegetation cover [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Nowadays, landslide occurs more frequent due to climate change (heavy rainfall) and human activities such as deforestation, excavation, construction, or mining [

14,

15]. These activities alter the land cover and slope equilibrium leading to instability state [

16,

17]. Geological survey, seismic ultrasonic or soil properties analysis are used to elucidate the root cause of mass movement event in specific area at a certain moment [

18,

19,

20]. Various traditional solutions have been applied and obtained a good results such as vegetation restoration, reinforcement, and land use management...[

21,

22]. Frequency and consequence of the landslide is dependent on the event location, soil composition and natural conditions [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Basaltic soil is a weatherd soil which is a weathering product of the basalt rock, a kind of fine-grained extruded rock [

27]. Basalt rock contributes approximately 5% earth’s land cover, weathering and bahaviour of them are a crucial in global biogeochemical cycle [

27,

28]. Basaltic soil, also known as “red basaltic soil or laterite”, is nutrient-rich and fertile, making it ideal for numerous crops. Red basaltic soil consits of gibbsite (45-50%), goethite, kaolinite minerals [

29]. Recent studies revealed that basaltic soil exposed to high precipitation may reduce the ferric (Fe

3+) and cation (Na

+, Ca

2+), capturing the CO

2 via siliate weathering [

27,

30,

31]. In addition the collidal properties of basaltic soil is sensitive to high rainfall that may reduce the surface charging of clay materials in the soil [

29].

This study utilizes a comprehensive methodology to elucidate mechanisms of landslide events occurring in the red basalt soil due to high precipitation. A field observation has been conducted to examine the geological structure of the soil [

10,

22,

27]. Undisturbed core sample were collected and analysed in the laboratory to examine the physical properties of the soils. In addition, numerical model has been used to analyse the stability of the slope under various rainy conditions. Findings from this study elucidate the root causes of the mass movement events which provides an in-sight of the rainfall-induced events in the red basalt soil area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Investigation

Dalat city is located on the Langbian Plateau in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, at an elevation of approximately 1,500 meters above sea level. The topography is characterized by mountainous terrain in the northeast, plains in the southwest, and intervening valleys in the central region. Dalat experiences a subtropical highland climate with year-round temperate weather, and average temperatures ranging from 14 to 23 °C (

Figure 2). The city has two distinct seasons: a rainy season from May to October and a dry season from November to April. The average annual rainfall of 2022, 2023 and 2024 were 2,165; 2,230, and 2,050 mm respectively. Dalat city has dense network of river and stream including Dong Nai mainstream river and its tributaries. There are two soil groups: red feralite soil and humus alisols, both distributed at altitudes between 1,000 and 2,000 meters [

32]. The geological structure of Dalat comprises Precambrian basement rocks, Jurassic sedimentary formations, Late Mesozoic igneous rocks, and Cenozoic basalt formations [

33,

34,

35].

Figure 1 illustrates the boundary of the survey area, where a field investigation was conducted from April 29

th to May 22

th, 2017, to study soil characteristics and geological structures. A subsequent observation was carried out in July 2019 to examine hydrological parameters and perform a pumping test. There was total 06 boreholes namely HK01 - HK06 were drilled up to 15 - 20 m to explore the geological structure. The surface layer consists of 1–2 meters of fill material, followed by a second layer dominated by lean clay with a reddish-brown to dark brown-white color. This layer is homogeneous and exhibits a hard plastic consistency. The deeper layer comprises silty clay rich in silt content, with colors varying from dark yellow to reddish brown. During the investigation period, cummulative precipitation reached 268 mm, with a peak at 65 mm. Undisturbed core samples were collected for laboratory analysis to assess the physical properties and mechanical behavior of the soils [

36].

2.2. Physical Properties Analysis

The sieve experiments were conducted in the laboratory to determine the contribution of various grain sizes contained in a core sample. The mechenical sieve was used to determine the coarse particle size (> 75 µm) and the hydrometer analysis was utilized for the finer size [

37,

38]. The whole nest of sieves is given a horizontal shaking for 10 min in sieve shaker till the soil retained on each reaches a constant value. The contribution of different grain sizes regulates the physical properties of soil and its behaviour under external loads. Meanwhile, permeability, shear strength and moisture are reported to affect the landslide susceptibility negatively or positively [

39,

40].

Figure 2.

Natural condition at the study site. The top panel indicates the rainfall (red column) and the average temperature the lower panel indicates the relationship between humidity (dash black line) and humidity in the red dash line.

Figure 2.

Natural condition at the study site. The top panel indicates the rainfall (red column) and the average temperature the lower panel indicates the relationship between humidity (dash black line) and humidity in the red dash line.

2.3. Real-Time Observations System

A tilt sensor and strain gauge system were installed to monitor the groundwater table and horizontal displacement of the soil layers [

10,

41,

42]. There total 15 sections of strain gauge were installed in a drill hole at every 1 meter to observe the deformation behavior inside the cut slope.

Figure 3 illustrates the schematic of the early warning system with the tilt sensor, pipe strain gauge and water level gauge to detect any displacement of the slope. The gauge system was installed in a 60 mm diameter borehole drill to observe the horizon displacement up to 15 m at every meter. It is defined that, positive or negative values are registered for unstable condition of the soil layer [

10]. Meanwhile, monitoring data is recorded every 10 minutes by the real-time data logger name as NetLG-301NE® (Osasi Co. Technos Inc, Japan). A wireless transmitter is used to transfer the monitoring data to the satellite orbit which could be received by the portable laptop computer or mobile devices. Signals from titl sensors reveals the horizontal displacement of the soil structure [

10].

2.4. Slope Stability Analysis

There are several factors that govern stability during rainfall including slope geometry, soil properties, rainfall intensity, soi moisture, and initial water table [

43,

44]. The objective of numerical model is to highlight the relative importance of some of these factors on the stability of predominately unsaturated slopes. In his research, Fredlund et al. (1978) proposed a linear relationship between soil shearstrength and effective cohesion, air pore-air pressure and friction angle which is:

where is the shear strength, is the effective cohesion, is the net normal stress on the failure plane, is the total normal stress, is the air pore-air pressure, is the pore-water pressure, is the matric suction, is the friction angle, is the angle linking the rate of increase in shear strength with increasing matric suction.

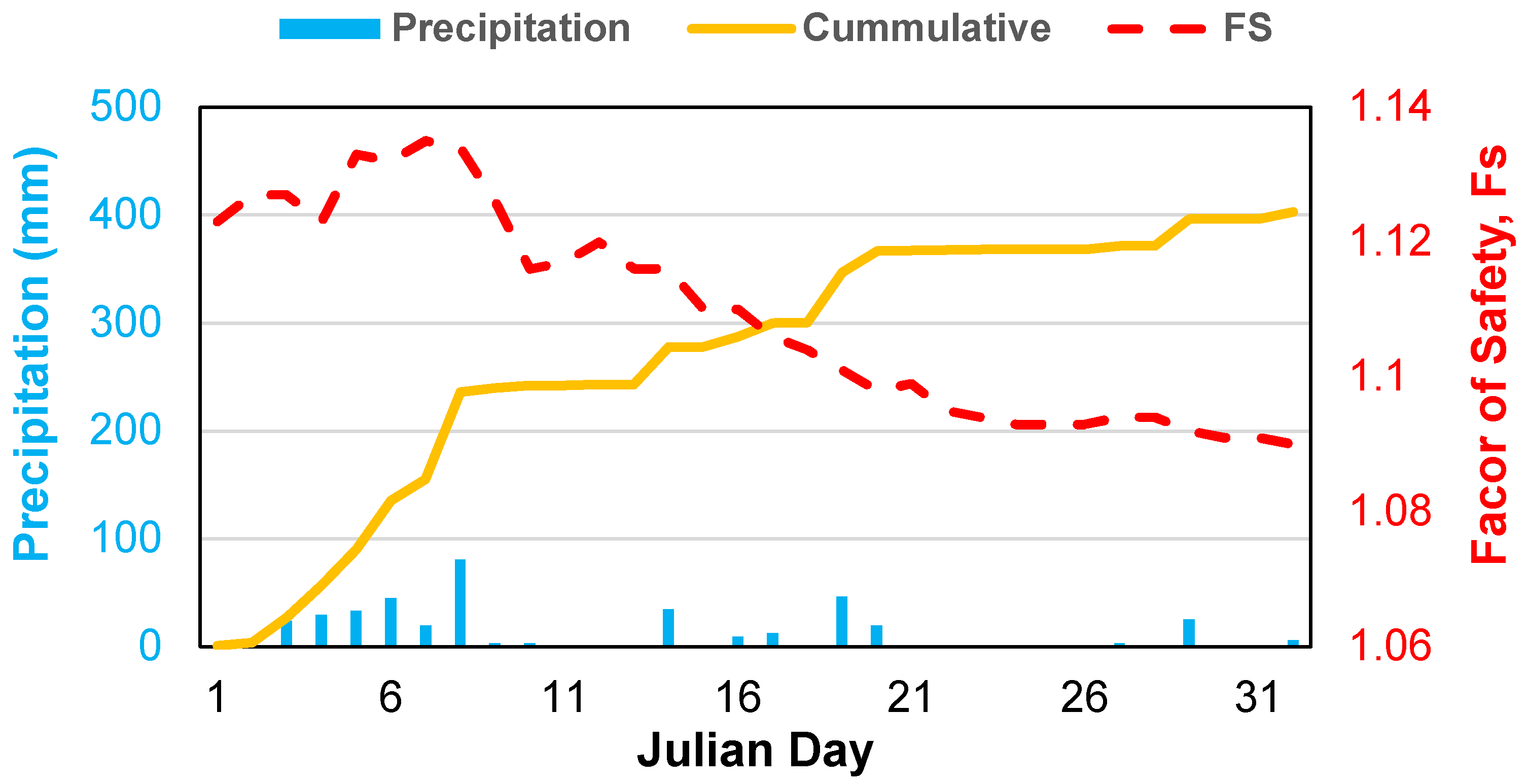

To determine the factor of safety, groundwater level, rainfall intensities, and soil properties were input to numerical model. Daily rainfall intensities in May 24

th to June 1

st 2022 was used to simulate the slope stability model. Observations groundwater level obtained from the tilt sensor system was also utilized for the model. Physical properties of the soil layers obtained from the sieve analysis was adopted for Mohr–Coulomb’s theory (

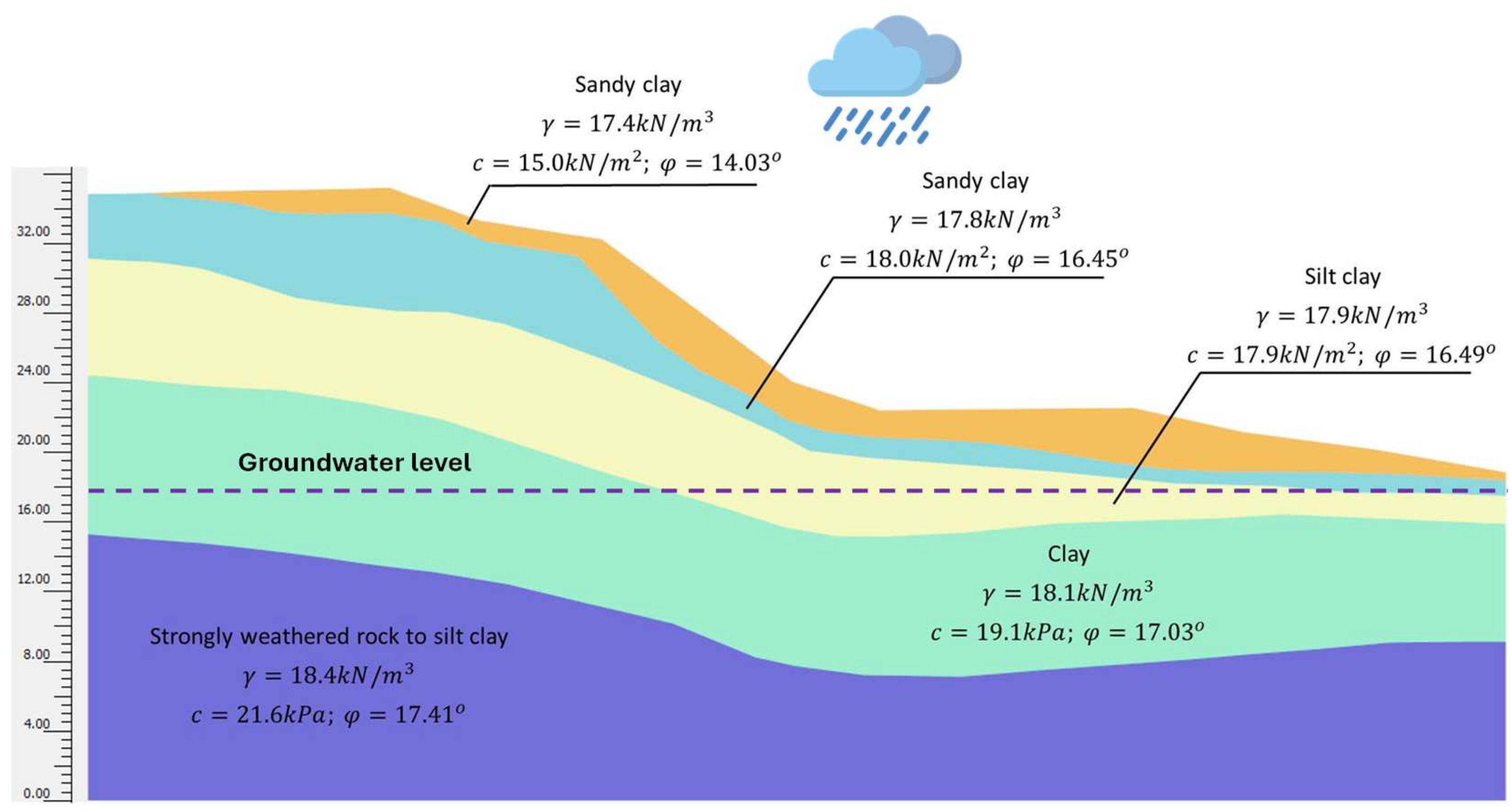

Figure 4).

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

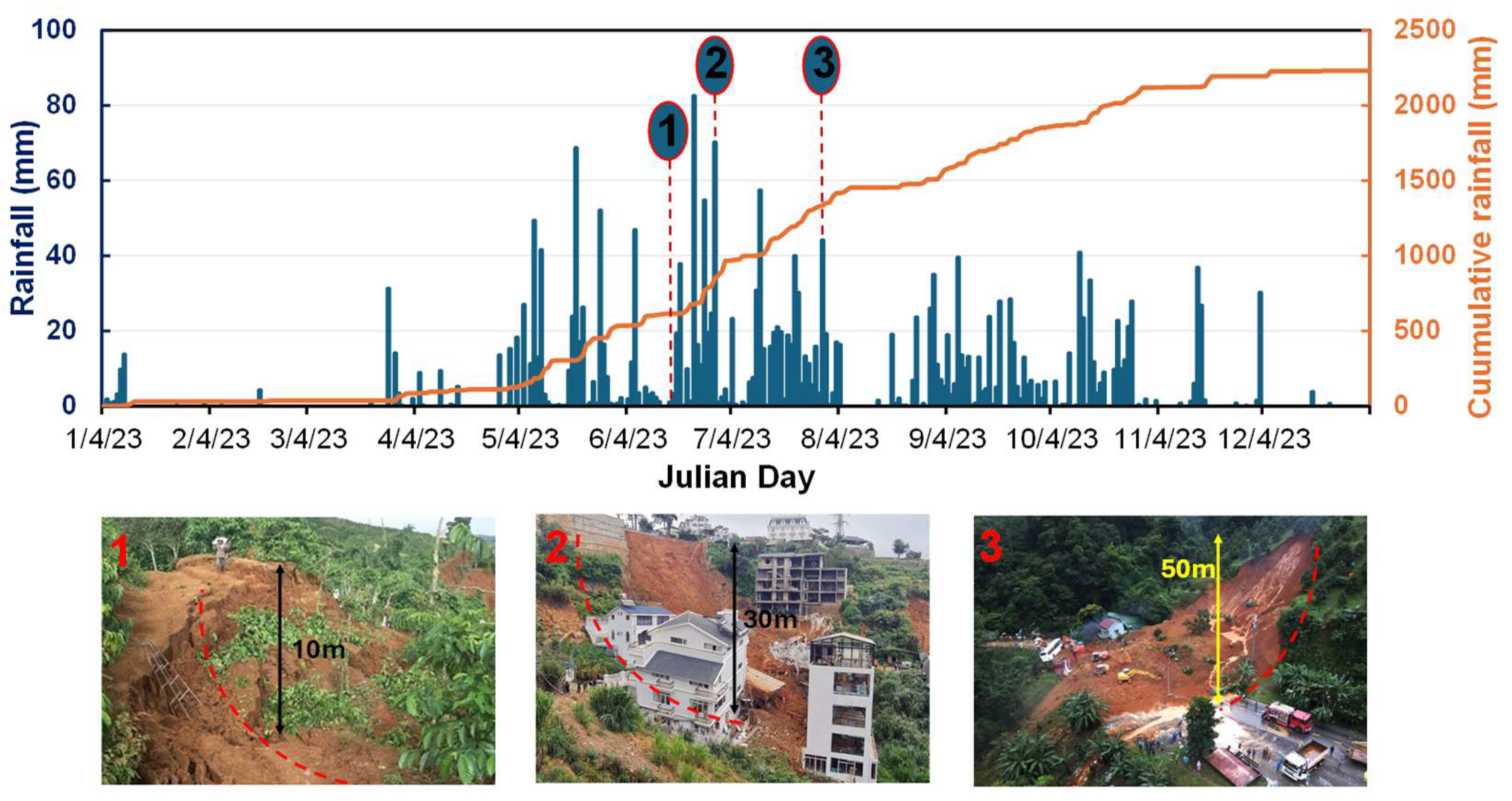

Figure 5 presents the average rainfall recorded in the calendar year of 2023, with cummulative total of 2,230 mm. In the observation period, the number of rainy day is 188 days, which are primarily between May to November, with the highest daily reaching 82.5 mm. During this period, three major mass movement events were recorded. The first event occured on June 17

th 2023 on the plantation farm, burying approximately 50,000 m

2 coffee crops. Within the following six hours, the situation escalated, resulting in the complete destruction of an additional 200,000 m² of coffee farms. On June 29

th, 2023, a 30-meter-high backfill slope failed, leading to two fatalities, three injuries, and damage to 12 houses. The most catastrophic event took place on July 30

th 2023, resulting in four fatalities and compeleted destroyed the section of National Road No. 20, a main route to Dalat City. This sudden landslide involved the failure of a 50-meter hill slope of plantation farm after two months of continuous rainfall. The high intense and frequency of rainfall altered the soil saturation condition, increased the groundwater level and elevated the risk of slope instability.

3.2. Physical Characteristic of the Soil Structure

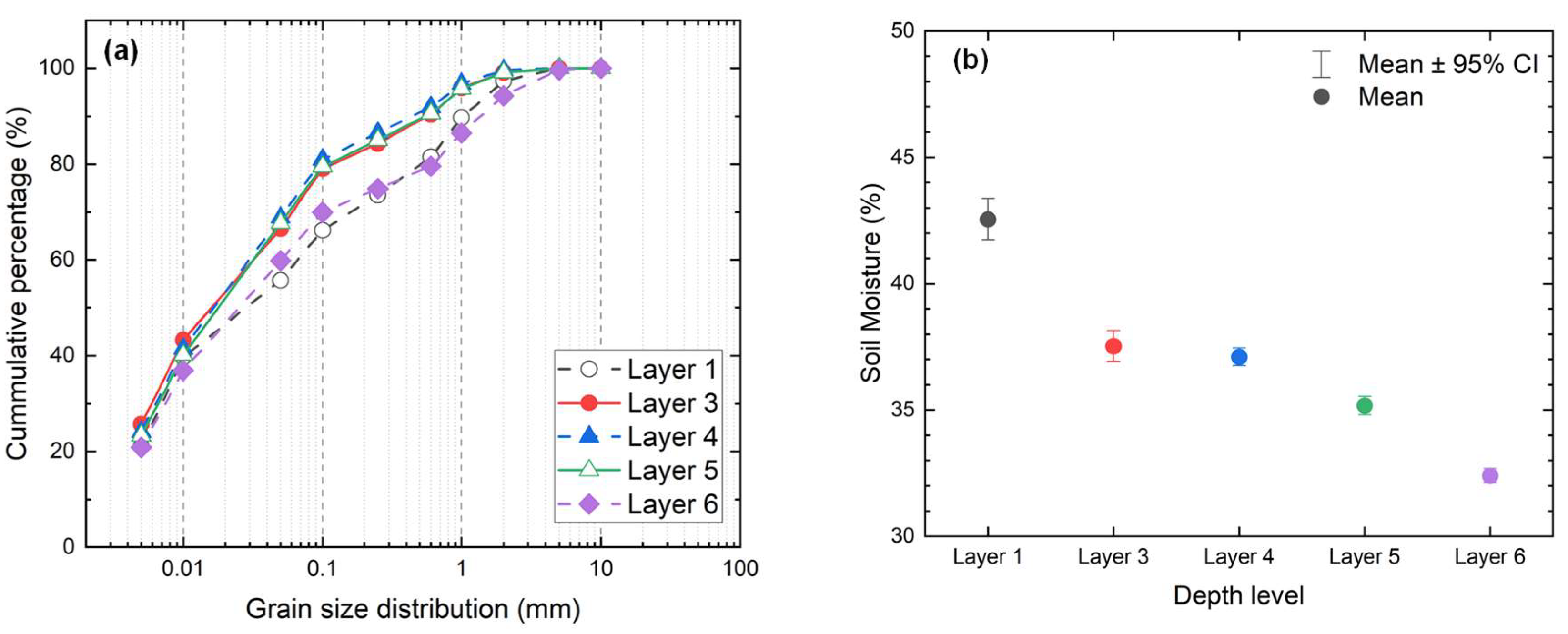

Table 1 indicates the physical characteristic in various depth layers of the soil structure obtained during the field survey. The water content in various layers dropped down in range of 41.47 to 33.01 % vertically. In addition, the void ratio were reduced 10% from the top layer whereas the cohesion increased from 14.7 to 20.7 kPa.

Figure 6a illustrates the fine grain size composition (< 75 µm) of soil structures with a contribution of > 70% in the core samples. On the other hand, the moisture is vertically dropped down in range of 45 – 30% (

Figure 6b). The fine grain component with negative charged and high water retention, facilitates the soils structure [

45]. Physical characteristic of the soil structure regulates the bahaviour of the slope to external factor.

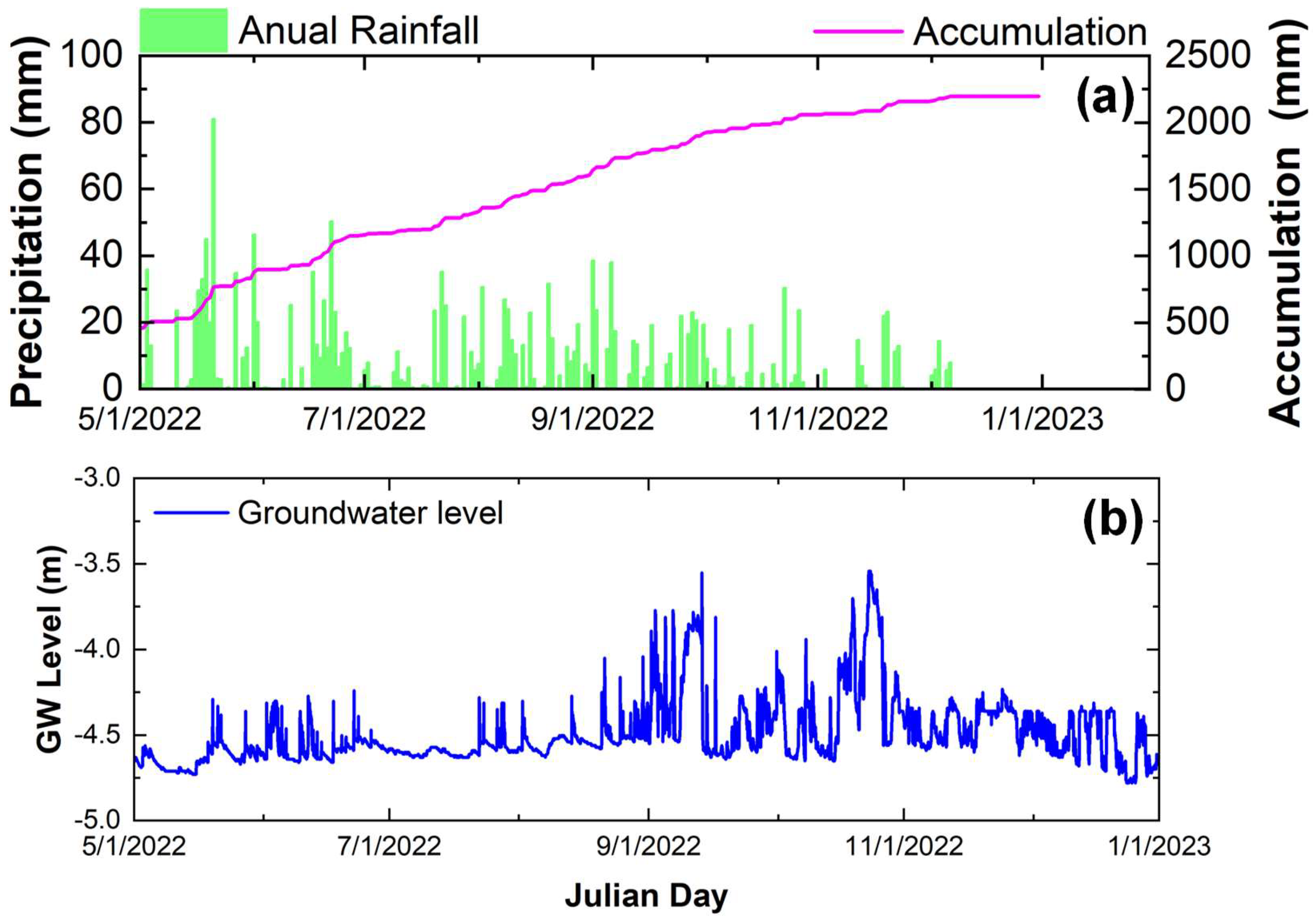

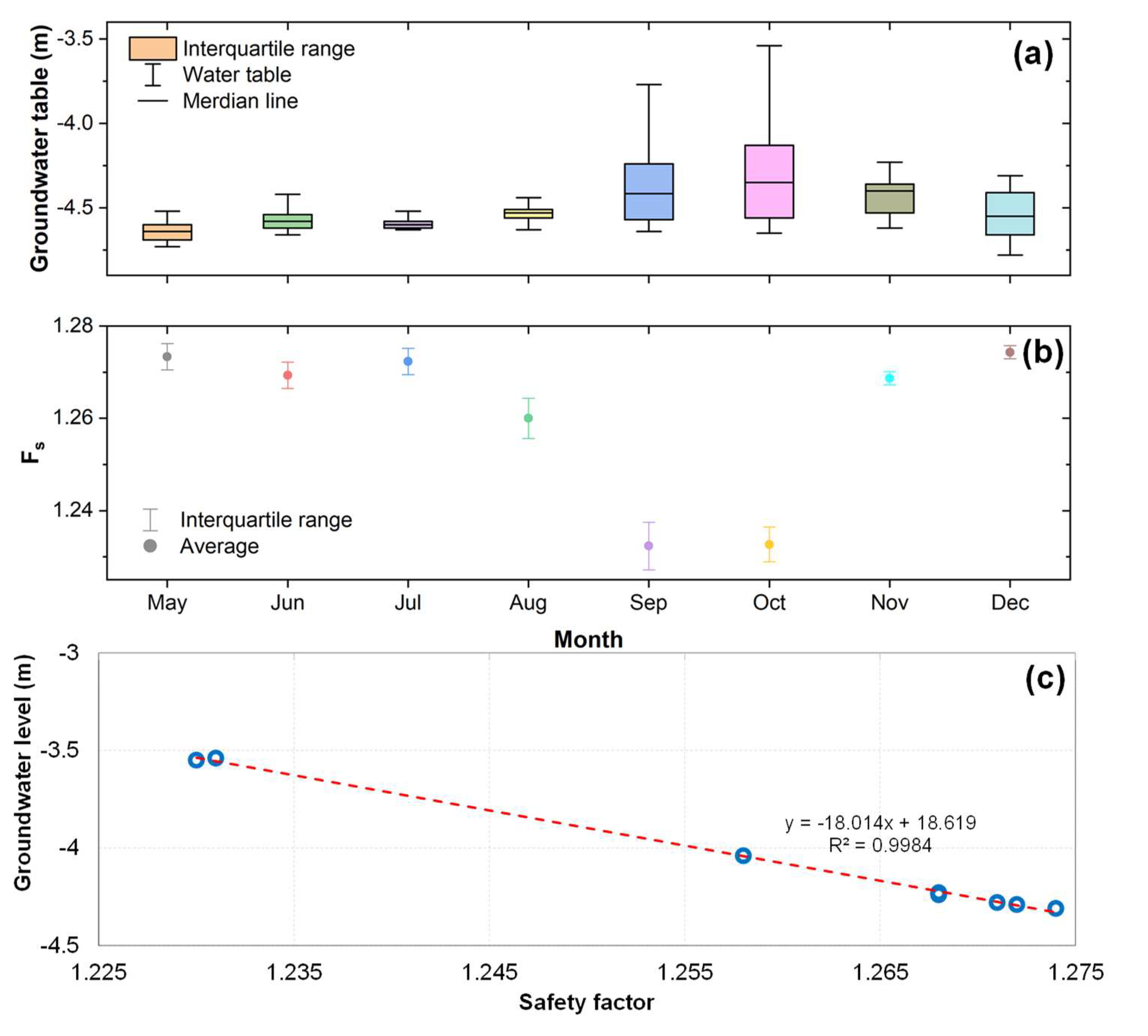

3.3. Seasonal Water Table Variations

Figure 7 indicates the time series of groundwater table observed from the May 1

st 2022 to Jan 1

st 2023. During the rainy season, the average rainfall varied from 20 – 50 mm, hit a peak at 80 mm, whereas the rainfall was below 20 mm in the dry season. The number days of rainfall was four times to sunny days in this observed period. Intense rainfall has resulted in high accumulation of the precipitation (> 2000 mm) leading to high amplitude of groundwater table fluctuation. Rainfalls mediates the groundwater level, soil moisture and slope stability such as erosion, mass flow movements [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In addition, intense precipitation facilitates the variation of groundwater and pore pressure, leading to slope stability and landslide occurrence [

44,

50,

51,

52].

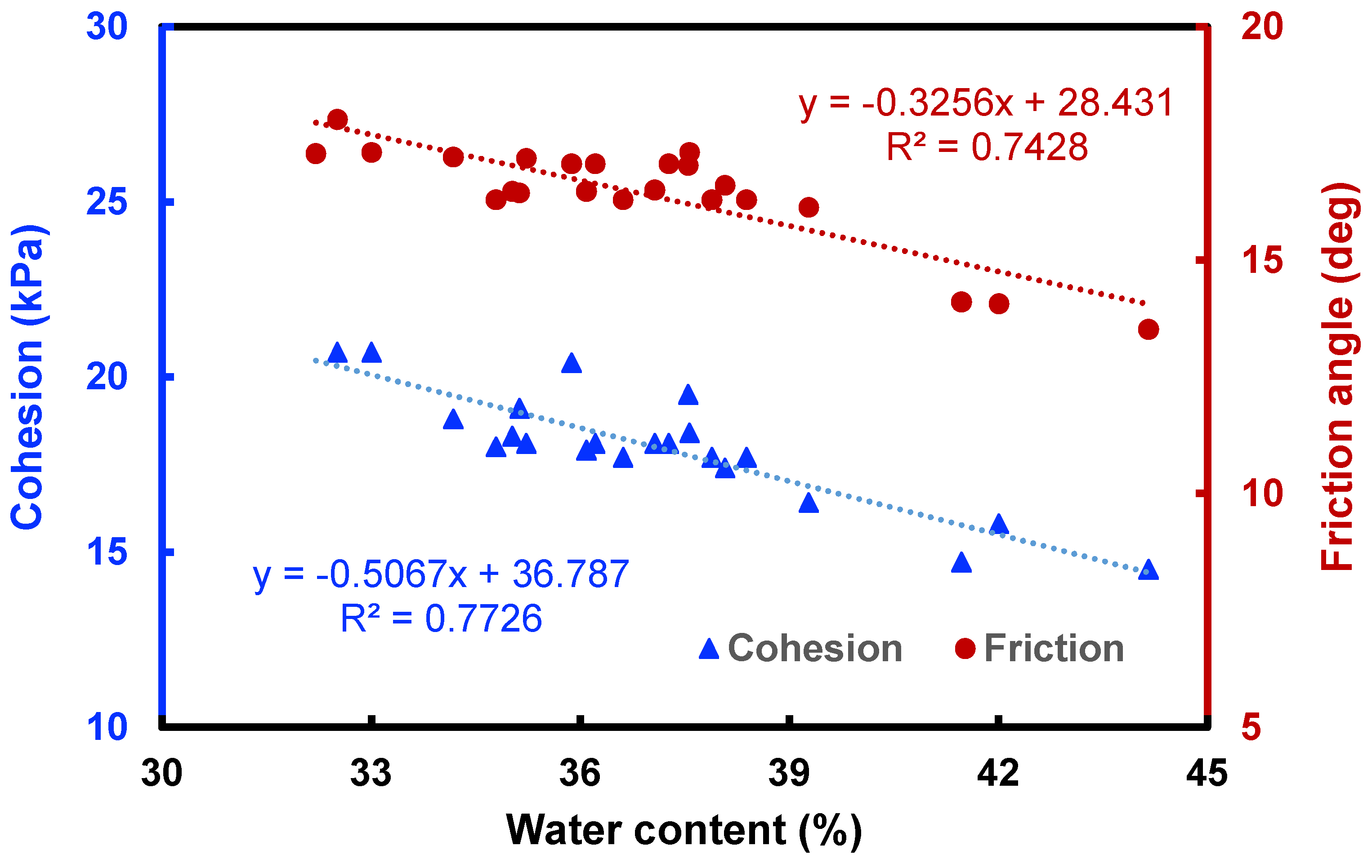

Figure 8 indicates the relationship between water content and shear strength parameters of the soil. It was seen that, the increase of water content reduced the cohesion (

c) and friction angle (

). These correlation enhances the instability of the soil structure which is in good agreement with previous studies [

53,

54].

3.4. Rainfall-Mediated Slope Stability Analysis

Figure 9 indicated results of nine-rainy day simulations using Plaxis

® 2D software. The accummulative precipitation is 403 mm with the highest rate of 81 mm. Results shown that, factor of safety dropped down from 1.135 to 1.09. It is noted that, groundwater level varied in -4.31 to -4.65 m in this period. The increase in groundwater table may result in soil moisture which affects the shear strength of the soil and slope stability [

44,

49].

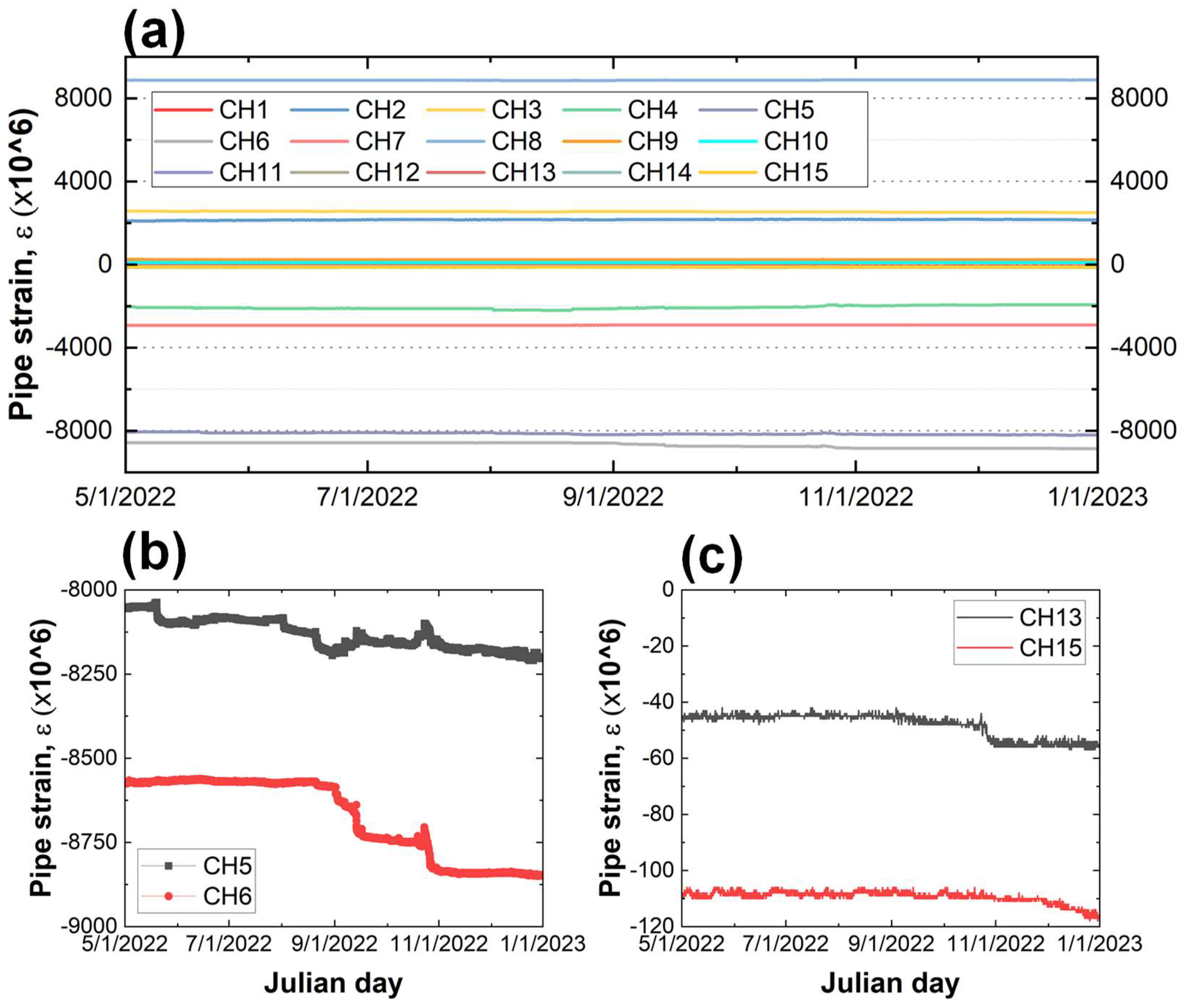

3.5. Observation of Horizontal Displacement of the Soil Structure

Figure 10 indicated horizontal displacement of the soil structure in various depth layer observed from the tilt system in the period of 00:00:00 May 1

st 2022 to 23:00:00 Dec 31

st 2022. The 3-wired strain gaue system identified a signal in channel No. of 5, 6, 13 and 15. In channels 5 and 6 (in -5 – -6 m depth), the strain sensors responded a signal of ~8,000 microstrains whereas a microstrains of 40 – 120 were recored at the channel No. 13 and 16 respectively. Other layers were identified stable during the observation period. Strains gauge signals provides a an entropy value that can be used for detection and early warning of landslide events [

55].

4. Discussion

4.1. Rainfall - Induced Weathering Reduces the Shear Strength and Slope Stability

Physicochemical properties of basalt soil is predominant with calcium, magnesium-rich silicate minerals, fenspate, and low total nitrogen, organic carbon [

30,

56]. Basaltic weathering plays a crucial role in global weathering patterns and biogeochemical cycling [

28,

57,

58]. High precipitaiton enhances the weathering of the basaltic soils through exchanges of cation. Removing of the sodium ion results in the reducing of shear strength of the soil structures [

30]. In addition, intense precipitation reduce Rainfall and rainfall frequency mediates the landslide whereas anthropogenic enhances the rate of the hazards [

59].

Previous studies reveals that, water content, porosity, and clay content are crucial in the soil stability. Red basaltic soil typically comprises with Ca

2+, Mg

2+, Na

+, Si

4+, Al

3+ and Fe

3+ [

60]. The higher cation exchange capacity (CEC), the higher Ca

2+ and OH

- ions to be consumed for C–S–H cycle, resulting in the lower of soil strength. In addition, the cation release in structure may lead to increase the void volume that are available room for water entrapment, enhancing the void pressure of soil structures.

Figure 11.

Conceivable mechanisms of slope failure due to rainfall-induced weathering process [

61].

Figure 11.

Conceivable mechanisms of slope failure due to rainfall-induced weathering process [

61].

4.2. Groundwater Level Facilitates the Slope Stability

Groundwater table is a crucial factor on the slope stability [

62,

63].

Figure 7 illustrates the close relationship of ground water and rainfall. Water table increased in companion with the accumulative precipitation which facilitates the soil moisture, resulting in the drop down of cohesion (

c) and friction angle (

) that may result in decreasing of safety factor (See

Figure 12). The higher of shear strength parameter in soil strucutre would enhance the factor of safety of the slope [

64].

Figure 12c further indicates the highly correlated relationship of the variable safety factor and seasonal water table.

Fluctuation of groundwater level mediates the soil moisture which play a crucial roles in slope stability [

65]. The rise of groundwater results in requent slope failure. In addition, higher of soil moisture reduces the shear strength of the fine grain slope due to reducing of cohesion force of the silt-clay particle [

64]. Therefore, dewatering is one of the suitable solution to control the hydrological regime, reduces the slope unstability and slope mass movement problems [

52].

4.3. Strain Gauge Sensor to Provide an Early Detect the Mass Movement

Early warning system (EWS) is now become popular in landslide prevention measure. The integrated system including internet of thing (IoT) on-site sensors automatically monitor and record parameters that cause landslides such as: slope displacement, hydrological and physical properties in soil, as well as precipitation using various tools [

55]. Improvements in sensor technology and information transformation open a new horizon in multi-hazard mitigation and prevention. Signal recorded from strain auge sensor offers a valuable information to early detect the mass movement. The strain gause sensor continuously collects the data, transform to the users through wireless system and provide an alert on the susceptibility of the soil structure and slope stability.

5. Conclusions

This paper elucidates the infuence of rainfall and human activities on landslide disaster in the red basaltic soil in the highland terrain, highlight the following key findings are:

High precipitation rates accelerate the weathering of basaltic soils by leaching essential cations, such as sodium, which leads to a reduction in the shear strength of soil structures. Moreover, frequent and intense rainfall events significantly increase the likelihood of landslides;

Fluctuations in groundwater levels contribute to increased soil moisture, which, in turn, reduces shear strength parameters and destabilizes slopes;

Human-induced activities exacerbate the frequency of mass movement events. Common triggers include slope cutting for construction and cultivation on steep, vulnerable slopes. These activities increase external loading and promote water entrapment within the soil, thereby reducing slope stability;

Tilt sensor systems provide real-time data on groundwater levels and horizontal displacement at various depths. This technology forms a crucial component of early warning systems for multi-hazard risk management. In addition, integrating smart technologies and Internet of Things (IoT) solutions is highly beneficial for effective natural disaster management.

Last but not least, climate change—with increased precipitation and extreme weather events—poses an additional stressor to slope stability and hazard prevention efforts. Urbanization and agricultural activities further compound these risks. Therefore, the deployment of real-time monitoring systems is increasingly important. The early warning data they provide are vital for disaster prevention, mitigation, and safeguarding communities at risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.N. and T.T.H.; methodology, T.T.H., T.L.K. and H.S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.H. and T.L.K.; writing—review and editing, H.S.N.; visualization, H.S.N. and T.T.H.; supervision, H.S.N.; project administration, T.L.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under Grant No. “B2024-20-20”.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HCMUT), VNU-HCM for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Trung Tin Huynh was employed by the company Bach Khoa Ho Chi Minh City Science Technology Joint Stock. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Varnes, D.J. Slope movement types and processes. Special report 1978, 176, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, R.L.; Wieczorek, G.F. Landslide triggers and types. In Landslides; Routledge: 2018; pp. 59-78. [CrossRef]

- Hungr, O.; Leroueil, S.; Picarelli, L. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides 2014, 11, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.M. Landslide triggering by rain infiltration. Water resources research 2000, 36, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohari, A. Study of rainfall-induced landslide: a review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2018, 118, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, G.D.A.; Giannecchini, R.; Puccinelli, A. The influence of the geological and geomorphological settings on shallow landslides. An example in a temperate climate environment: the June 19, 1996 event in northwestern Tuscany (Italy). Engineering geology 2004, 73, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, M.-G.; Pasuto, A.; Silvano, S. A critical review of landslide monitoring experiences. Engineering Geology 2000, 55, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, N.; Badoux, A.; Hegg, C. The Swiss flood and landslide damage database 1972–2007. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2009, 9, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranken, L.; Van Turnhout, P.; Van Den Eeckhaut, M.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Poesen, J. Economic valuation of landslide damage in hilly regions: A case study from Flanders, Belgium. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 447, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.R.; Nakata, Y.; Shitano, M.; Kaneko, M. Rainfall-induced unstable slope monitoring and early warning through tilt sensors. Soils and Foundations 2021, 61, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Zhao, B.; Liu, D.; Deng, Y.; Cheng, H.; Yan, Y.; Ding, S.; Cai, C. Effect of soil moisture on soil disintegration characteristics of different weathering profiles of collapsing gully in the hilly granitic region, South China. Plos one 2018, 13, e0209427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korup, O. Rock type leaves topographic signature in landslide-dominated mountain ranges. Geophysical Research Letters 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Nakayama, D.; Matsuyama, H. Relationship between the initiation of a shallow landslide and rainfall intensity—duration thresholds in Japan. Geomorphology 2010, 118, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, H.; Dai, Q.; Zhu, J. Ensemble Predictions of Rainfall-Induced Landslide Risk under Climate Change in China Integrating Antecedent Soil-Wetness Factors. Atmosphere 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, E.F.; Nazem, M.; Karakus, M. Numerical analysis of a large landslide induced by coal mining subsidence. Engineering Geology 2017, 217, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, M.J. Deciphering the effect of climate change on landslide activity: A review. Geomorphology 2010, 124, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. On the causes of landslides: Human activities, perception, and natural processes. Environmental Geology and Water Sciences 1992, 20, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auflič, M.J.; Herrera, G.; Mateos, R.M.; Poyiadji, E.; Quental, L.; Severine, B.; Peternel, T.; Podolszki, L.; Calcaterra, S.; Kociu, A.; et al. Landslide monitoring techniques in the Geological Surveys of Europe. Landslides 2023, 20, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G.; Mateos, R.M.; García-Davalillo, J.C.; Grandjean, G.; Poyiadji, E.; Maftei, R.; Filipciuc, T.-C.; Jemec Auflič, M.; Jež, J.; Podolszki, L.; et al. Landslide databases in the Geological Surveys of Europe. Landslides 2018, 15, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongmans, D.; Garambois, S. Geophysical investigation of landslides: a review. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France 2007, 178, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qi, W.; Zhou, J. Effects of precipitation and topography on vegetation recovery at landslide sites after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Land Degradation & Development 2018, 29, 3355–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olim, D.; Afu, S.; Ediene, V.; Uko, I.; Akpa, E. Morphological and physicochemical properties of basaltic soils on a toposequence in Ikom, South Eastern Nigeria. World News of Natural Sciences 2019, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, J.; Moya, J. A review of assessing landslide frequency for hazard zoning purposes. Engineering Geology 2008, 102, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, F.W.Y.; Lo, F.L.C. From landslide susceptibility to landslide frequency: A territory-wide study in Hong Kong. Engineering Geology 2018, 242, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyaş, H.; van Westen, C.J.; Allstadt, K.E.; Jibson, R.W. Factors controlling landslide frequency–area distributions. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2019, 44, 900–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, R.H.; Evans, S. Analysis of landslide frequencies and characteristics in a natural system, coastal British Columbia. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms: The Journal of the British Geomorphological Research Group 2004, 29, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingiani, S.; Terribile, F.; Meunier, A.; Petit, S. Weathering of basaltic pebbles in a red soil from Sardinia: A microsite approach for the identification of secondary mineral phases. CATENA 2010, 83, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessert, C.; Dupré, B.; Gaillardet, J.; François, L.M.; Allègre, C.J. Basalt weathering laws and the impact of basalt weathering on the global carbon cycle. Chemical Geology 2003, 202, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, N.A.; Nam, K.Q.; Anh, T.T. Red basaltic soils-the raw material source for production of non-calcined brick. Vietnam Journal of Earth Sciences 2014, 36, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.L.; Torres, M.A.; Kemeny, P.C. The hydrochemical signature of incongruent weathering in Iceland. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 2022, 127, e2021JF006450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, A.; Sardini, P.; Robinet, J.; Prêt, D. The petrography of weathering processes: facts and outlooks. Clay minerals 2007, 42, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, D.Q.; Nguyen, D.H.; Prakash, I.; Jaafari, A.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Van Phong, T.; Pham, B.T. GIS based frequency ratio method for landslide susceptibility mapping at Da Lat City, Lam Dong province, Vietnam. Vietnam J Earth Sci 2020, 42, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.B.; Satir, M.; Siebel, W.; Chen, F. Granitoids in the Dalat zone, southern Vietnam: age constraints on magmatism and regional geological implications. International Journal of Earth Sciences 2004, 93, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellnutt, J.G.; Lan, C.-Y.; Van Long, T.; Usuki, T.; Yang, H.-J.; Mertzman, S.A.; Iizuka, Y.; Chung, S.-L.; Wang, K.-L.; Hsu, W.-Y. Formation of Cretaceous Cordilleran and post-orogenic granites and their microgranular enclaves from the Dalat zone, southern Vietnam: Tectonic implications for the evolution of Southeast Asia. Lithos 2013, 182, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, A.; Phan, L.; Travin, A.; Mikheev, E.; Murzintsev, N.; Annikova, I.Y. The geology and thermochronology of Cretaceous magmatism of southeastern Vietnam. Russian Journal of Pacific Geology 2020, 14, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, E.; Cardina, J. Characterizing the structure of undisturbed soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1997, 61, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Shi, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yang, J.; Hanley, K.J. Effects of grain composition on the stability, breach process, and breach parameters of landslide dams. Geomorphology 2022, 413, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, A. The effects of clay on landslides: A case study. Applied Clay Science 2007, 38, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, A.J. Relations between soil development and landslides. Hydrogeology, chemical weathering, and soil formation 2021, 177-185. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeng, R.; Meng, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, H. Effects of changes in soil properties caused by progressive infiltration of rainwater on rainfall-induced landslides. Catena 2023, 233, 107475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano Jr, J.S.; Zarco, M.A.H.; Talampas, M.C.R.; Catane, S.G.; Hilario, C.G.; Zabanal, M.A.B.; Carreon, C.R.C.; Mendoza, E.A.; Kaimo, R.N.; Cordero, C.N. Real-world deployment of a locally-developed tilt and moisture sensor for landslide monitoring in the Philippines. 2011 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference. 2011, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zet, C.; Foşalău, C.; Petrişor, D. Pore water pressure sensor for landslide prediction. 2015 IEEE SENSORS 2015, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Nobahar, M.; Ivoke, J.; Amini, F. Rainfall induced shallow slope failure over Yazoo clay in Mississippi. In PanAm Unsaturated Soils 2017; 2017; pp. 153-162. [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Rana, H.; Babu, G.S. Analysis of rainfall-induced shallow slope failure. Proceedings of the Indian Geotechnical Conference 2019: IGC-2019 Volume I 2021, 679-691. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Ravi, K.; Garg, A. Influence of biochar on the soil water retention characteristics (SWRC): Potential application in geotechnical engineering structures. Soil and Tillage Research 2020, 204, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, A.; Fares, A. Influence of groundwater pumping and rainfall spatio-temporal variation on streamflow. Journal of Hydrology 2010, 393, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z. Response of Soil Moisture to Four Rainfall Regimes and Tillage Measures under Natural Rainfall in Red Soil Region, Southern China. Water 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Peng, X. Responses of deep soil moisture to direct rainfall and groundwater in the red soil critical zone: A four-stage pattern. Journal of Hydrology 2024, 632, 130864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltahir, E.A. A soil moisture–rainfall feedback mechanism: 1. Theory and observations. Water resources research 1998, 34, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Ikeda, T.; Kamei, T.; Wada, T. Field Investigations on Seasonal Variations of the Groundwater Level and Pore Water Pressure in Landslide Areas. Soils and Foundations 1987, 27, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohari, A.; Nishigaki, M.; Komatsu, M. Laboratory rainfall-induced slope failure with moisture content measurement. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2007, 133, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, S.; Şenol, A. Groundwater Level Estimation for Slope Stability Analysis of a Coal Open Pit Mine. Civil Engineering Research Journal 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, S.; Gratchev, I. Effect of Water Content on Apparent Cohesion of Soils from Landslide Sites. Geotechnics 2022, 2, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Su, M.; Zhang, S.; Lu, D. Stability Analysis of a Weathered-Basalt Soil Slope Using the Double Strength Reduction Method. Advances in Civil Engineering 2021, 2021, 6640698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, K.; Yao, Y.; Yang, J.; Zheng, G.; Li, Q. Capture and prediction of rainfall-induced landslide warning signals using an attention-based temporal convolutional neural network and entropy weight methods. Sensors 2022, 22, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.L.; Sarkar, B.; Wade, P.; Kemp, S.J.; Hodson, M.E.; Taylor, L.L.; Yeong, K.L.; Davies, K.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Effects of mineralogy, chemistry and physical properties of basalts on carbon capture potential and plant-nutrient element release via enhanced weathering. Applied Geochemistry 2021, 132, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Song, F.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Bi, F.; Xu, M. Investigating CO₂ sequestration via enhanced rock weathering: Effects of temperature and citric acid on dolomite and basalt. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 485, 144414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Southard, R.J. Basalt weathering and pedogenesis across an environmental gradient in the southern Cascade Range, California, USA. Geoderma 2010, 154, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, K.-J.; Lin, J.-F. Evaluation of the extreme rainfall predictions and their impact on landslide susceptibility in a sub-catchment scale. Engineering Geology 2020, 265, 105434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorover, J.; Amistadi, M.K.; Chadwick, O.A. Surface charge evolution of mineral-organic complexes during pedogenesis in Hawaiian basalt. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta 2004, 68, 4859–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, G.; Burkett, D.; Coventry, R. A laboratory study of application of basalt dust to highly weathered soils: effect on soil cation chemistry. Soil Research 2001, 39, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, G.; Gong, S.; Sun, H.; Chantat, K. Analysis of Rainfall-induced Landslide Using the Extended DDA by Incorporating Matric Suction. Computers and Geotechnics 2021, 135, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Mardhanie, A.; Suroso, P.; Sutarto, T.; Alfajri, R. Effect of groundwater table on slope stability and design of retaining wall. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2020; p.^pp, 012072.

- Sibala, E.; Langkoke, R. Determination of safety factor value of PIT design based on cohesion and friction angle. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 235, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, Z.; Song, M.; Arai, K. Stability analysis of slopes with ground water during earthquakes. Engineering Geology 2015, 193, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).