Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) remain a significant public health challenge worldwide. Traditional treatment methods, while effective, face numerous barriers such as accessibility, stigma, and cost. The advent of telemedicine and online therapy platforms presents a promising avenue for overcoming these obstacles and enhancing treatment outcomes. This paper explores the potential of telemedicine and online interventions in treating SUDs, reviewing current evidence and discussing future directions.

Substance use disorders (SUDs) remain a formidable challenge to global public health, impacting millions of individuals across diverse populations. These disorders, characterized by the problematic use of psychoactive substances such as opioids, alcohol, and stimulants, lead to significant personal, social, and economic consequences. Traditional treatment modalities for SUDs have evolved over decades and typically involve a combination of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions. Despite their demonstrated efficacy, numerous challenges such as accessibility, stigma, and treatment adherence continue to hinder their widespread application and effectiveness.

The evolution of digital technology in health care, particularly the advent of telemedicine and online treatment platforms, presents a unique opportunity to transcend many of these barriers. Telemedicine, defined broadly as the remote delivery of healthcare services using telecommunications technology, can offer treatment options that are both accessible and cost-effective for many who would otherwise not receive help. Recent research underscores the potential of telemedicine in providing effective intervention for substance use disorders, which suggests comparable outcomes to traditional in-person therapy concerning abstinence and treatment retention (Lin et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the ongoing global digital transformation has accelerated the integration of online resources into daily life, thereby increasing the feasibility of online interventions for SUDs. Online platforms can deliver therapy through various formats, including but not limited to, real-time video conferencing, asynchronous messaging, and digital learning modules. These interventions are not only pragmatic but also align well with the increasing consumer preference for digital health solutions that offer privacy, convenience, and user-centered control (Kay-Lambkin et al., 2011).

Moreover, the application of online and telemedicine interventions could play a critical role in destigmatizing substance use disorder treatment. The anonymity and privacy afforded by online platforms can help mitigate the shame and stigma that often deter individuals from seeking treatment. This is crucial because stigma is a significant barrier that affects access to care and is associated with poorer quality health outcomes (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Given the potential of telemedicine and online interventions to address these multifaceted issues, it is vital to explore their capabilities and limitations thoroughly. This exploration must consider the variety of technological, ethical, and regulatory challenges that these innovations face. By examining these aspects in depth, the current paper aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the state of telemedicine and online treatments for SUDs and their future implications for policy, practice, and research in the field.

The Landscape of Substance Use Disorders

Substance use disorders encompass a range of conditions associated with the excessive use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol, opioids, cannabis, and stimulants. These disorders are characterized by a chronic, relapsing nature and have substantial impacts on individuals' physical and mental health, social relationships, and overall quality of life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Substance use disorders (SUDs) encompass a complex array of conditions that involve the problematic use of psychoactive substances such as alcohol, opioids, stimulants, and cannabis. These disorders are characterized by an individual's intense focus on obtaining and using these substances, despite the occurrence of negative consequences. The impact of SUDs extends beyond the individual, affecting families, communities, and the overall health care system, posing a significant burden on societal resources.

The definition and classification of SUDs have evolved over the years, with the current diagnostic criteria being detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). According to DSM-5, the diagnosis of a substance use disorder is based on evidence of impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacological criteria.

Epidemiologically, the global prevalence of substance use disorders varies significantly by substance type and region. According to the World Drug Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2020), millions of people worldwide suffer from drug use disorders, with opioids accounting for a substantial portion of the disease burden associated with drug use. Alcohol use disorders also represent a significant public health issue, with the World Health Organization (2018) reporting that excessive alcohol use leads to millions of deaths and disabilities each year.

The pathophysiology of SUDs involves complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and social factors. Genetic predispositions play a significant role in the development of these disorders, influencing neurotransmitter systems that mediate reward pathways in the brain. Volkow et al. (2016) discuss how alterations in the dopamine system can predispose individuals to substance use by enhancing the reinforcing effects of drugs. Environmental factors, including exposure to drugs, stress, and trauma, interact with these genetic factors to facilitate the development of SUDs.

Treatment landscapes for SUDs are diverse and require a multifaceted approach. Historically, treatment modalities have included detoxification, pharmacotherapy, behavioral therapies, and support groups. Each treatment approach aims to address various aspects of addiction, from physiological dependence and withdrawal to psychological and social rehabilitation. The integration of behavioral health interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing (MI), has been shown to be effective in treating substance use disorders by targeting the underlying cognitive and emotional processes (McHugh et al., 2010).

Despite available treatments, SUDs often manifest as chronic, relapsing conditions, with high rates of recidivism. The chronic nature of these disorders necessitates ongoing management strategies, similar to other chronic diseases like diabetes or hypertension. This perspective aligns with the shifting paradigm in healthcare towards more sustainable, long-term management of SUDs, focusing on recovery as a lifelong journey of engagement in treatment and personal growth (McLellan et al., 2000).

Moreover, the treatment of SUDs faces several challenges, including the stigma associated with drug use and addiction, which can prevent individuals from seeking help. There is also a significant gap in the treatment provision, with a large proportion of individuals with SUDs not receiving any form of care. This treatment gap is attributed to various factors, including limited access to healthcare services, lack of trained healthcare providers, and the aforementioned stigma.

In conclusion, understanding the landscape of substance use disorders requires a comprehensive grasp of their epidemiology, pathophysiology, and the challenges associated with their treatment. Addressing these needs with effective, evidence-based strategies and policies is essential for mitigating the impact of these disorders on individuals and society.

Traditional Treatment Approaches

Traditional treatment for SUDs often involves a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Medications like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone are used to manage withdrawal symptoms and reduce cravings (Volkow et al., 2014). Psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (MI), and contingency management, play a crucial role in addressing the psychological aspects of addiction (McHugh et al., 2010).

Traditional approaches to the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) have historically centered on a blend of pharmacological interventions and psychotherapeutic techniques, aiming to address both the biological and psychological facets of addiction. These approaches are grounded in decades of research and clinical practice, providing a robust framework for the management and recovery of individuals afflicted with SUDs.

Pharmacological Treatments

Pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders (SUDs) are an essential component of comprehensive care, particularly for those struggling with moderate to severe addiction. Medications are used to manage withdrawal symptoms, reduce cravings, prevent relapse, and help restore the brain’s neurochemical balance, which is often disrupted by prolonged substance use. While psychotherapeutic interventions address the psychological and behavioral aspects of addiction, pharmacological treatments target the biological and neurochemical processes that underpin SUDs. The combination of these two approaches has proven to be more effective than either one in isolation, particularly for severe cases of addiction (Fiellin, 2002). In this section, we will explore the main categories of pharmacological treatments for SUDs, including treatments for alcohol use disorder (AUD), opioid use disorder (OUD), and nicotine addiction, among others.

Opioid use disorder is one of the most critical public health crises globally, with millions of individuals affected by misuse of both prescription opioids and illicit opioids like heroin. The pharmacological treatment of OUD primarily involves the use of opioid agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists, which help manage withdrawal symptoms and reduce cravings. These medications have been shown to improve retention in treatment, reduce illicit opioid use, and decrease mortality rates (Mattick et al., 2014).

1.1 Methadone

Methadone is a full opioid agonist that has been used for decades in the treatment of OUD. It binds to opioid receptors in the brain, reducing cravings and withdrawal symptoms without producing the same euphoric effects as heroin or other opioids. Methadone is typically administered in a highly controlled setting, such as a licensed clinic, due to its potential for abuse and overdose if not properly managed. Studies have demonstrated that methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is highly effective at reducing opioid use, increasing treatment retention, and improving overall quality of life for individuals with OUD (Mattick et al., 2009).

1.2 Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, meaning it activates opioid receptors in the brain but to a lesser degree than full agonists like methadone. This characteristic makes buprenorphine less likely to cause overdose, and it can be prescribed in an outpatient setting, making it more accessible for patients. In the United States, buprenorphine can be prescribed by qualified healthcare providers, which increases access to treatment in areas where methadone clinics may not be available. Studies have shown that buprenorphine is as effective as methadone in reducing opioid use and promoting long-term recovery, with fewer side effects and less risk of overdose (Fiellin et al., 2014).

1.3 Naltrexone

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that blocks the effects of opioids by binding to the brain’s opioid receptors without activating them. This prevents individuals from experiencing the euphoric effects of opioids, which helps deter opioid use. Unlike methadone and buprenorphine, naltrexone is not a controlled substance and can be prescribed more freely. However, it requires that the individual has fully detoxified from opioids before starting treatment, which can be a significant barrier due to the severity of opioid withdrawal symptoms. Despite this challenge, research indicates that naltrexone is effective in preventing relapse among individuals who are highly motivated and able to complete detoxification before starting treatment (Lee et al., 2018).

- 2.

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Alcohol use disorder is one of the most common SUDs, affecting millions of people worldwide. Pharmacological treatments for AUD aim to reduce cravings, diminish the rewarding effects of alcohol, and manage withdrawal symptoms. These medications are often used in conjunction with behavioral interventions to maximize effectiveness.

2.1 Disulfiram

Disulfiram is one of the oldest medications used to treat AUD. It works by inhibiting the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, which is involved in the metabolism of alcohol. When alcohol is consumed, disulfiram causes a buildup of acetaldehyde in the body, leading to highly unpleasant effects such as nausea, vomiting, flushing, and headaches. These aversive reactions discourage individuals from drinking. While disulfiram is effective in promoting abstinence, its success largely depends on patient adherence, as it only works if taken consistently (Fuller & Gordis, 2004).

2.2 Naltrexone

Naltrexone, which is also used to treat OUD, has been shown to be effective in treating AUD as well. It works by blocking opioid receptors, which are involved in the rewarding effects of alcohol. This reduces the pleasurable sensations associated with drinking, helping to curb cravings and decrease heavy drinking. Both oral and extended-release injectable forms of naltrexone are available, with the latter showing higher rates of adherence due to its once-monthly administration. Research has demonstrated that naltrexone can significantly reduce the risk of relapse and help individuals maintain abstinence from alcohol (Anton et al., 2006).

2.3 Acamprosate

Acamprosate is another medication used to treat AUD, though its mechanism of action is not fully understood. It is believed to stabilize brain chemistry by modulating glutamate and GABA neurotransmitter systems, which are disrupted by chronic alcohol use. Acamprosate is typically used to help individuals maintain abstinence after they have stopped drinking, rather than during the detoxification phase. A large clinical trial known as the COMBINE study found that acamprosate was most effective in promoting abstinence when used in combination with behavioral therapies and support systems (Gustafson et al., 2014).

- 3.

Medications for Nicotine Addiction

Nicotine addiction remains a significant public health issue, contributing to various chronic diseases, including lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory illness. Pharmacological treatments for nicotine addiction primarily aim to reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings, helping individuals quit smoking or using other nicotine products.

3.1 Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) involves the use of products that deliver nicotine to the body without the harmful chemicals found in tobacco products. These products include nicotine patches, gums, lozenges, nasal sprays, and inhalers. NRT helps reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings, making it easier for individuals to quit smoking. Studies have shown that NRT is effective in increasing quit rates, especially when combined with behavioral interventions (Stead et al., 2012).

3.2 Bupropion

Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant that has been approved for smoking cessation. It works by inhibiting the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine, which helps reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms associated with nicotine dependence. Bupropion has been shown to nearly double the chances of quitting smoking compared to placebo, and its efficacy is enhanced when combined with behavioral support (Hughes et al., 2004).

3.3 Varenicline

Varenicline is a partial agonist of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, which is involved in the addictive properties of nicotine. It works by stimulating the receptor to reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms while also blocking the effects of nicotine if a person smokes during treatment. Varenicline has been shown to be one of the most effective pharmacological treatments for nicotine addiction, significantly increasing the likelihood of quitting compared to placebo or other medications (Cahill et al., 2013).

- 4.

Medications for Stimulant Use Disorder

Currently, there are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of stimulant use disorders, such as cocaine or methamphetamine addiction. However, several pharmacological agents are being investigated for their potential efficacy in treating these disorders.

4.1 Modafinil

Modafinil, a stimulant commonly used to treat narcolepsy, has shown promise in reducing cocaine use in some studies. Its mechanism of action involves increasing levels of dopamine in the brain, which may help reduce cravings for cocaine. However, clinical trials have produced mixed results, and modafinil has not yet been approved for the treatment of stimulant use disorders (Karila et al., 2011).

4.2 Bupropion

Bupropion has also been studied for its potential to treat stimulant use disorders, particularly methamphetamine addiction. As an atypical antidepressant, bupropion’s dopaminergic activity may help reduce cravings for stimulants. Although some studies have shown positive outcomes, further research is needed to establish its efficacy in treating stimulant use disorders (Heinzerling et al., 2014).

- 5.

Combining Pharmacological and Psychotherapeutic Treatments

The integration of pharmacological treatments with psychotherapeutic interventions is considered the gold standard in the treatment of SUDs. Pharmacotherapy can address the biological aspects of addiction, such as withdrawal symptoms and cravings, while psychotherapy helps individuals develop coping mechanisms and address underlying psychological issues. Research has consistently shown that combined treatments produce better outcomes than either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy alone (McLellan et al., 1993).

Psychotherapeutic Treatments

Psychotherapeutic treatments form the cornerstone of many interventions for substance use disorders (SUDs). These treatments focus on modifying the underlying psychological, behavioral, and emotional components of addiction. While the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions in treating SUDs is well-established, these treatments have continued to evolve, integrating new approaches and techniques aimed at improving outcomes. The role of psychotherapy in SUD treatment is diverse, encompassing a range of modalities from well-established cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to emerging strategies like mindfulness-based therapies and contingency management.

- -

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is one of the most widely used and researched psychotherapeutic approaches for SUDs. CBT operates on the premise that maladaptive behaviors and thought patterns contribute to substance use, and it aims to teach individuals skills for recognizing and changing these patterns (Beck, Wright, Newman, & Liese, 1993). Techniques such as identifying triggers, developing coping strategies, and learning to challenge and reframe harmful beliefs are central to CBT’s approach in helping patients avoid relapse and maintain sobriety.

A meta-analysis by Magill and Ray (2009) found that CBT is highly effective in treating alcohol and drug use disorders. The study showed that individuals undergoing CBT were more likely to achieve abstinence and maintain long-term recovery compared to those receiving no psychotherapeutic treatment or minimal intervention. The effectiveness of CBT is largely attributed to its structured nature, allowing individuals to develop and practice new skills in a systematic way.

- -

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

Motivational interviewing (MI) is another key psychotherapeutic technique widely used in the treatment of SUDs. MI is a client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Rather than confronting individuals about their substance use directly, MI seeks to help them articulate their reasons for change and recognize the discrepancies between their current behavior and long-term goals. The efficacy of MI in SUD treatment has been well-documented in various studies. A review by Lundahl and Burke (2009) found that MI is effective in improving treatment adherence and reducing substance use across a range of populations, including adolescents and adults. The collaborative and non-judgmental nature of MI makes it particularly suitable for individuals who may initially be resistant to treatment, helping them build motivation for long-term recovery.

- -

Contingency Management (CM)

Contingency management is an evidence-based psychotherapeutic intervention that uses tangible rewards to reinforce abstinence from substance use. CM is based on the principles of operant conditioning, where desirable behaviors (e.g., negative drug tests) are reinforced with rewards such as vouchers or prizes (Higgins et al., 2000). The idea behind CM is that by providing immediate positive reinforcement for sobriety, individuals will be more likely to continue engaging in recovery-supportive behaviors.

Research has consistently shown that CM is effective in treating a range of substance use disorders, particularly stimulant and opioid use disorders. For instance, a study by Petry, Alessi, and Ledgerwood (2010) found that individuals receiving CM were significantly more likely to remain abstinent during treatment and to continue engaging with therapeutic services compared to those receiving standard care. While the logistics of implementing CM can be complex, especially in resource-limited settings, its efficacy has made it a critical component in many treatment programs.

- -

Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP)

In recent years, mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) has gained popularity as an adjunct to traditional psychotherapeutic treatments for SUDs. MBRP integrates mindfulness practices with cognitive-behavioral strategies to help individuals develop awareness of their thoughts and emotions without reacting impulsively to them (Bowen et al., 2009). The goal of MBRP is to reduce relapse by increasing individuals' ability to cope with cravings and high-risk situations through mindfulness techniques such as meditation and body awareness.

A randomized controlled trial by Bowen et al. (2014) demonstrated that MBRP was more effective than standard relapse prevention and treatment-as-usual in reducing relapse rates among individuals with SUDs. Participants who received MBRP reported fewer days of substance use and a greater ability to manage stress and cravings. The growing body of research supporting MBRP highlights the importance of integrating holistic approaches into SUD treatment, focusing not only on behavior but also on the underlying emotional and cognitive processes that contribute to substance use.

- -

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), originally developed for individuals with borderline personality disorder, has also been adapted for use in treating substance use disorders. DBT combines cognitive-behavioral techniques with mindfulness practices, emphasizing emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness (Linehan, 1993). DBT’s structured approach makes it particularly suitable for individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders, which are common among those with SUDs.

Research by Linehan et al. (1999) found that DBT was effective in reducing substance use and improving overall mental health outcomes in individuals with co-occurring SUDs and emotional dysregulation. The skills taught in DBT—such as tolerating distress and regulating emotions—are critical for preventing relapse, particularly in individuals who may use substances as a way to cope with overwhelming emotions.

- -

Family Therapy

Family therapy is another psychotherapeutic intervention that has shown significant promise in the treatment of SUDs. Substance use disorders often have profound effects on family dynamics, and involving the family in treatment can be crucial for long-term recovery. Family therapy helps address dysfunctional family patterns that may contribute to substance use and provides a platform for family members to work together in supporting the individual’s recovery (O'Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006).

Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) is one form of family therapy that has been particularly effective in treating alcohol use disorders. A study by O'Farrell et al. (2012) found that individuals who participated in BCT had higher rates of abstinence and better relationship satisfaction compared to those receiving individual therapy alone. The collaborative approach of BCT helps improve communication, reduce conflict, and foster a supportive environment for recovery.

- -

Emerging Psychotherapeutic Approaches

In addition to the well-established psychotherapies mentioned above, new approaches continue to emerge, reflecting the dynamic nature of the field. For example, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is gaining traction as a treatment for SUDs. ACT encourages individuals to accept their thoughts and feelings rather than attempting to avoid or change them, while committing to behavior change aligned with their values (Hayes et al., 2006).

A study by Luoma, Kohlenberg, Hayes, Bunting, and Rye (2008) demonstrated that ACT can reduce shame and stigma associated with substance use, helping individuals to engage more fully in their recovery process. This emphasis on acceptance and value-driven behavior makes ACT a promising option, particularly for individuals who struggle with self-judgment and shame around their addiction.

Recovery Coaching and Peer Recovery Coaching

Recovery coaching differs from traditional clinical interventions in that it is non-clinical and focuses on providing mentorship and guidance. Coaches work with individuals to develop personalized recovery plans, address barriers to recovery, and provide accountability for achieving recovery goals (White, 2009). Unlike therapists or counselors, recovery coaches do not focus on diagnosing or treating SUDs but rather on empowering individuals to take control of their recovery journey.

Peer recovery coaching takes this model a step further by involving coaches who have lived experience with addiction and recovery. This peer-based approach leverages the power of shared experiences to build trust and rapport, creating an environment where individuals feel understood and supported (Eddie et al., 2019). Peer coaches serve as role models and mentors, providing practical advice on overcoming challenges related to addiction, relapse prevention, and building a fulfilling life in recovery.

With the rise of telehealth platforms, both recovery coaching and peer recovery coaching have increasingly shifted to remote delivery. This shift has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated the rapid adoption of remote healthcare solutions. Remote recovery coaching offers numerous advantages, including increased accessibility for individuals who may not have access to in-person services due to geographical, financial, or logistical barriers (Tracy et al., 2016).

Through video calls, phone calls, text messaging, and online platforms, recovery coaches can provide consistent, ongoing support regardless of location. This continuous access to support is particularly valuable for individuals in recovery, as it allows them to stay connected with their coach and receive timely guidance when faced with triggers or challenges (Bassuk et al., 2016).

One of the most significant benefits of remote recovery coaching is its ability to reach individuals in underserved areas. People living in rural or remote locations often have limited access to SUD treatment services, and recovery coaching delivered remotely can bridge this gap. Research has shown that telehealth approaches, including remote coaching, can effectively engage individuals who might not otherwise seek help due to logistical constraints or the stigma associated with attending in-person treatment (McKay & Weiss, 2001).

Remote recovery coaching offers unparalleled flexibility, allowing individuals to receive support on their terms. Sessions can be scheduled at convenient times, and communication can take place through various platforms, including video conferencing, text messaging, or phone calls. This flexibility makes it easier for individuals to fit recovery coaching into their daily lives, particularly for those balancing work, family, or other responsibilities (Ashford et al., 2018).

Incorporating recovery coaching into telehealth models provides continuous care, which is crucial for individuals in recovery. Frequent check-ins with a coach can help individuals stay accountable, monitor progress, and address challenges in real time. Remote coaching also allows for immediate support during moments of crisis or vulnerability, providing a safety net that can prevent relapse (Bassuk et al., 2016).

One of the defining features of peer recovery coaching is the emphasis on shared lived experiences. Research has demonstrated that peer support can play a critical role in recovery by fostering a sense of belonging and mutual understanding. Peer coaches offer unique perspectives that clinical providers may not have, as they have personally navigated the challenges of addiction and recovery (Tracy & Wallace, 2016). This shared experience helps build trust and rapport, encouraging individuals to open up about their struggles and feel less isolated in their recovery journey.

Integrated Treatment Programs

The importance of integrated treatment programs becomes evident when considering the high rates of co-occurring mental health disorders (often referred to as dual diagnosis) among individuals with SUDs. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), about 37.9% of adults with substance use disorders also suffer from co-occurring mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (SAMHSA, 2020). Traditional models of care often treated these conditions separately, leading to fragmented care and poorer outcomes. Individuals with co-occurring disorders were typically shuffled between addiction treatment services and mental health providers, with little coordination between the two, resulting in gaps in care that frequently led to relapse or worsening symptoms of both conditions (Drake et al., 2001).

Integrated treatment programs were developed to address these shortcomings by offering comprehensive care that simultaneously addresses SUDs and co-occurring mental health disorders. These programs recognize that both conditions interact and influence each other, necessitating a cohesive treatment plan that considers all aspects of an individual’s health.

There are several models of integrated treatment that vary in their approach to care delivery. Some programs focus primarily on integrating addiction treatment with mental health services, while others incorporate additional elements, such as primary medical care, housing support, and vocational services. Each model seeks to provide a "whole-person" approach that tailors treatment to the unique needs of each individual.

- -

Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT)

The Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT) model is one of the most established frameworks for treating individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders and SUDs. IDDT is an evidence-based practice that provides combined mental health and addiction treatment services in a single setting. The core principles of IDDT include a long-term, stage-wise approach to recovery, motivational interventions, comprehensive services, and individualized treatment plans (Mueser et al., 2003). Research has shown that IDDT significantly improves outcomes for individuals with dual diagnoses by reducing substance use, improving psychiatric symptoms, enhancing quality of life, and increasing housing stability (Brunette & Mueser, 2006).

A study by Drake et al. (2004) found that individuals receiving IDDT were more likely to achieve sobriety, maintain stable housing, and experience improved mental health outcomes compared to those receiving traditional, non-integrated treatment. The study concluded that integrated treatment was particularly effective for individuals with severe mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

- -

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT)

Another successful model for integrated treatment is Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), a team-based approach that provides intensive, individualized care for people with severe mental illness and SUDs. ACT teams typically include psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, and substance abuse counselors who collaborate to offer comprehensive services in the community, rather than in a clinical setting (Bond & Drake, 2015). ACT is often used for individuals with co-occurring disorders who have difficulty engaging with traditional outpatient care due to factors such as homelessness, legal issues, or frequent hospitalizations.

The effectiveness of ACT in reducing hospitalizations, improving housing outcomes, and reducing substance use has been well documented. A meta-analysis conducted by Coldwell and Bender (2007) found that ACT was associated with significant reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations and improvements in housing stability for individuals with co-occurring SUDs and mental illness. The study also highlighted that the flexible, community-based nature of ACT allows individuals to receive care in real-world settings, making it easier to address both substance use and mental health symptoms as they arise in daily life.

- -

Integrated Primary Care and SUD Treatment

In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the need to integrate SUD treatment with primary care services. Many individuals with SUDs suffer from chronic medical conditions such as hepatitis C, HIV, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are exacerbated by substance use (Kresina & Lubran, 2011). Integrated primary care models aim to address the physical health needs of individuals with SUDs while simultaneously providing addiction treatment and mental health services. This holistic approach helps to improve overall health outcomes and reduces the risk of medical complications related to untreated physical conditions.

The implementation of Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) within primary care settings is an example of integrated care in action. MAT combines pharmacotherapy (such as methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat opioid use disorder. Research has shown that providing MAT in primary care settings increases accessibility, reduces stigma, and leads to better treatment retention (Kampman & Jarvis, 2015). A study by Fiellin et al. (2002) demonstrated that primary care-based buprenorphine treatment was effective in reducing opioid use and promoting long-term recovery in individuals with opioid dependence.

- -

Housing First Models

For individuals with SUDs who also experience homelessness or housing instability, integrated treatment programs that incorporate housing support have proven to be highly effective. The "Housing First" model is an evidence-based approach that provides immediate access to stable housing without preconditions, such as sobriety, and then integrates comprehensive support services to address substance use, mental health, and other needs (Tsemberis et al., 2004). Housing First programs are particularly effective in reducing substance use and improving overall well-being by offering individuals a safe and stable environment in which they can focus on recovery.

Research by Padgett, Gulcur, and Tsemberis (2006) found that individuals participating in Housing First programs were more likely to achieve long-term housing stability and had better outcomes in terms of substance use reduction and mental health symptom management compared to individuals in traditional treatment programs that required sobriety as a precondition for housing. The study highlighted the importance of addressing basic needs, such as housing, as part of an integrated approach to SUD treatment.

- -

Benefits of Integrated Treatment Programs

Integrated treatment programs offer several key advantages over traditional, non-integrated care models. One of the most significant benefits is improved treatment retention and engagement. Individuals with co-occurring disorders or complex medical and social needs often face barriers to accessing care, including transportation issues, stigma, and a lack of coordinated services. By providing all necessary services in a single, coordinated program, integrated treatment makes it easier for individuals to stay engaged in care over the long term (Sterling et al., 2011).

Additionally, integrated treatment programs are more effective in addressing the full range of issues that contribute to substance use. For example, individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders may use substances as a way of self-medicating their symptoms. By addressing both the substance use and the underlying mental health condition, integrated treatment programs can help individuals develop healthier coping mechanisms and achieve sustained recovery (Drake & Wallach, 2000).

- -

Challenges and Considerations in Integrated Treatment

While integrated treatment programs offer numerous benefits, they also present challenges that must be addressed to ensure their success. One of the main challenges is the need for adequate training and support for healthcare providers. Professionals working in integrated treatment settings must be equipped to address a wide range of issues, including substance use, mental health disorders, medical conditions, and social determinants of health. This requires ongoing training and collaboration among multidisciplinary teams (Priester et al., 2016).

Another challenge is funding and reimbursement for integrated care. In many healthcare systems, funding streams for mental health, substance use treatment, and medical care are separate, which can make it difficult to provide fully integrated services. Policymakers and healthcare organizations must work together to develop funding models that support the comprehensive, coordinated care provided by integrated treatment programs (Morrissey et al., 2005).

Barriers to Traditional Treatment

Despite the efficacy of these treatments, several barriers limit their accessibility and effectiveness. These include geographic limitations, long waiting times, the stigma associated with seeking help, and high treatment costs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). These barriers highlight the need for innovative approaches to make SUD treatment more accessible and effective.

Traditional treatment methods for substance use disorders (SUDs), while effective, encounter numerous barriers that limit their accessibility and efficacy for many individuals who need help. These barriers range from logistical and structural issues to personal and societal challenges, and their impact can often discourage or prevent individuals from seeking or continuing treatment.

Logistical and Structural Barriers

One of the most significant logistical barriers to accessing SUD treatment is geographic location. Many individuals live in areas that lack adequate treatment facilities, particularly in rural or underserved urban areas. This geographic disparity forces individuals to travel long distances for care, adding travel costs and time to the already substantial burden of seeking treatment (Andrilla et al., 2019). Additionally, the availability of specialized healthcare providers, such as addiction specialists or psychiatrists, is often limited in these areas, further complicating access to appropriate care.

Financial constraints also play a critical role in limiting access to SUD treatment. Many individuals struggling with substance use disorders lack health insurance or have insurance that does not cover all necessary aspects of SUD treatment, such as certain medications or long-term psychotherapy. The high cost of treatment programs, including inpatient care and specialized therapies, can be prohibitively expensive, deterring individuals from initiating or continuing treatment (Saloner & Cook, 2013).

Stigma and Societal Attitudes

Stigma associated with substance use and addiction remains a powerful barrier to treatment. Societal views that frame addiction as a moral failing rather than a medical condition can lead to shame and self-stigma among individuals with SUDs, discouraging them from seeking treatment due to fear of judgment from others (Livingston et al., 2012). This stigma can permeate various aspects of life, affecting personal relationships, employment opportunities, and interaction with healthcare systems, where individuals with SUDs may experience bias and discrimination from healthcare providers, further deterring them from seeking help.

Systemic Healthcare Issues

The healthcare system itself presents additional barriers. There is often a lack of integration between mental health services and other medical care, making it difficult for patients to receive comprehensive treatment addressing both substance use and other co-occurring health issues. The fragmentation of services can lead to poor coordination of care, conflicting treatments, and a higher likelihood of treatment dropout (Drake et al., 2001).

Regulatory issues also complicate the provision of care, particularly with medications used in addiction treatment. Regulations surrounding drugs like methadone and buprenorphine can restrict their use to specialized clinics or require practitioners to have specific certifications, limiting the number of providers who can prescribe these effective treatments (Volkow et al., 2014).

Personal and Psychological Barriers

Personal barriers also play a significant role in treatment engagement. Many individuals with substance use disorders also struggle with mental health disorders such as depression or anxiety, which can complicate the treatment process and reduce motivation to seek or adhere to treatment (Conway et al., 2006). Psychological barriers, such as denial of the severity of one’s addiction or fear of confronting painful emotional issues during therapy, can also impede the treatment process.

Additionally, the relapse-prone nature of addiction leads to cyclical entries into and exits from treatment, often influenced by personal circumstances, emotional states, and external pressures, which can discourage both patients and providers by creating a sense of futility around the treatment process.

Telemedicine and Online Interventions

Telemedicine involves the use of electronic communications and software to provide clinical services to patients without an in-person visit. Online interventions can include a range of services, from virtual counseling sessions to mobile health applications designed to support recovery (World Health Organization, 2010).

Telemedicine and online interventions represent a rapidly evolving sector within the broader context of healthcare, characterized by the use of electronic communications and information technologies to provide and support healthcare services when participants are separated by distance. This field has become particularly relevant for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs), offering an alternative to traditional face-to-face therapeutic models that can be limited by geographic, temporal, and socio-economic barriers.

Definition of Telemedicine

Telemedicine involves the delivery of health services using telecommunications technology to facilitate real-time interaction between a patient and a healthcare provider. This can include consultations via video conferencing, remote monitoring of patients' symptoms and medication management, and the use of digital platforms to provide continuous support and intervention (World Health Organization, 2010). The primary goal of telemedicine is to make healthcare accessible in remote areas, reducing the need for travel and enabling timely care delivery.

Online Interventions

Online interventions for SUDs typically encompass a range of services, including but not limited to, structured therapy sessions delivered through web-based platforms, mobile health applications designed to support recovery, and automated self-help tools that provide cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing (MI) techniques. These interventions are designed to be flexible, allowing users to access support at their convenience, which can significantly enhance engagement and adherence to treatment protocols (Kay-Lambkin et al., 2011).

Scope of Telemedicine and Online Interventions

The scope of telemedicine and online interventions is broad and multifaceted. It includes:

1. Virtual Consultations: Patients can consult with addiction specialists and mental health professionals without the need to travel, thus overcoming geographical barriers that often hinder access to care.

2. Digital Therapy Sessions: These sessions can be conducted via video calls, chats, or even through asynchronous messaging platforms, providing flexibility in scheduling and maintaining patient privacy and convenience.

3. Remote Monitoring: Wearable devices and mobile applications can monitor physiological indicators such as heart rate and stress levels, which can be useful for managing withdrawal symptoms and preventing relapse.

4. Self-management Tools: Online platforms often offer educational resources and tools for self-management, helping patients to develop skills necessary for recovery maintenance outside of formal therapy sessions.

5. Support Networks: Many online programs include access to peer support groups or forums where individuals can share their experiences and challenges, fostering a sense of community and mutual support.

Efficacy and Advantages

The efficacy of telemedicine and online interventions in treating SUDs has been supported by numerous studies. A systematic review by Lin et al. (2019) concluded that telemedicine could deliver outcomes comparable to those of conventional face-to-face treatments for various conditions, including SUDs. The accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and potential to reach underserved populations are among the primary advantages of telemedicine and online interventions. Moreover, the anonymity and privacy provided by online platforms can help reduce the stigma associated with seeking treatment for SUDs, which is often a significant barrier to accessing care (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Efficacy of Telemedicine in Sud Treatment

Research indicates that telemedicine can be as effective as in-person treatment for SUDs. A meta-analysis by Lin et al. (2019) found that telehealth interventions resulted in similar outcomes to face-to-face treatments regarding abstinence rates and treatment retention. Furthermore, telemedicine offers the advantage of increased accessibility, particularly for individuals in remote or underserved areas.

Telemedicine has demonstrated promising results as an effective modality for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs). Its utilization has grown significantly, particularly as it offers an alternative to conventional in-person treatment models, which can be limited by barriers such as accessibility, stigma, and logistical challenges.

Comparative Efficacy with Traditional Treatments

Studies comparing the efficacy of telemedicine to traditional face-to-face therapy have generally found that telemedicine can produce outcomes that are equivalent to or better than those of traditional settings. For example, a meta-analysis by Lin et al. (2019) reviewed various telemedicine interventions and found that these methods were effective in treating SUDs, showing similar treatment adherence and satisfaction levels among patients compared to those receiving conventional treatment. This suggests that telemedicine is not only a viable alternative but also a potentially preferable option for certain populations.

Treatment Retention and Completion Rates

One of the critical measures of treatment efficacy in SUDs is the retention rate, which is often higher in telemedicine programs compared to traditional in-person treatment programs. This increase can be attributed to the greater accessibility and flexibility of telemedicine, which allows patients to engage in therapy sessions from the comfort of their homes, thereby reducing dropout rates associated with logistical difficulties such as transportation and scheduling conflicts (Eibl et al., 2017).

Reduction in Substance Use

Telemedicine interventions have also been shown to effectively reduce substance use among participants. Research by Chaple et al. (2018) demonstrated that telehealth services, including online counseling and digital monitoring, significantly decreased the use of substances among participants over time. These findings are supported by the convenience and continuous support offered by telemedicine, which may enhance patient engagement and adherence to treatment protocols.

Improvement in Associated Psychological Symptoms

Telemedicine has been particularly beneficial in addressing not only substance use but also the psychological comorbidities often associated with SUDs, such as depression and anxiety. A study by King et al. (2020) found that participants receiving telemedicine interventions for SUDs reported significant improvements in their overall mental health. This is likely due to the holistic approach of telemedicine programs, which often integrate various treatment modalities, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing, that address both substance use and underlying mental health issues.

Advantages Over Traditional Treatment Modalities

The primary advantage of telemedicine in the treatment of SUDs is its ability to overcome geographical and physical barriers to access. Patients in rural or underserved areas, who previously had limited access to specialized care, can now receive high-quality treatment remotely (Yellowlees et al., 2018). Furthermore, telemedicine can be more convenient for patients, as it eliminates the need for travel and allows for scheduling flexibility.

Telemedicine can also be more cost-effective than traditional treatment methods. By reducing the need for physical infrastructure and minimizing travel and administrative costs, telemedicine can lower the overall cost of care delivery. These savings can then be passed on to the patient, making treatment more affordable (Bradford et al., 2016).

Another significant benefit of telemedicine is the increased privacy and anonymity it offers, which can help reduce the stigma associated with seeking treatment for SUDs. This can encourage more individuals to seek help early, potentially leading to better long-term outcomes (Link et al., 2001).

Online Counseling and Therapy

Online counseling, including video conferencing and chat-based services, allows individuals to receive therapy in a convenient and private manner. Studies have shown that online CBT and MI can effectively reduce substance use and improve mental health outcomes (Kay-Lambkin et al., 2011). The flexibility and anonymity of online therapy can also help reduce the stigma associated with seeking help for addiction (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Online counseling and therapy have emerged as vital components in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs), leveraging technology to overcome traditional barriers to access and enhance patient engagement. This method of delivery not only broadens the reach of therapeutic services but also introduces a level of convenience and accessibility that is not typically available with conventional face-to-face therapy sessions.

Overview of Online Counseling and Therapy Modalities

Online counseling for SUDs can take various forms, including synchronous video sessions, asynchronous messaging, and digital therapy modules. These services are often provided via secure platforms that ensure privacy and confidentiality, which are critical concerns for individuals seeking treatment for substance use issues.

Video Conferencing

Video conferencing is one of the most common forms of online therapy, offering real-time interaction between the therapist and the client. This format closely replicates the experience of traditional in-person therapy by allowing for visual cues and immediate feedback, which are essential for building rapport and facilitating therapeutic interventions. Research has indicated that video-based counseling can be just as effective as in-person sessions in reducing symptoms of SUDs and improving patient outcomes (Backhaus et al., 2012).

Asynchronous Communication

Asynchronous communication methods, such as email and text messaging, allow clients to communicate with their therapists at their convenience. This modality can be particularly beneficial for those who may need more time to articulate their thoughts and feelings or who have schedules that make live sessions difficult. Studies, such as those by Aguilera and Muñoz (2011), have shown that asynchronous messaging can effectively support treatment by enabling continuous communication and support, which can help maintain engagement between live sessions.

Digital Therapy Platforms

Digital therapy platforms often combine various therapeutic tools and resources, such as interactive modules based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) principles, motivational interviewing (MI) techniques, and educational content related to substance use and recovery. These platforms can provide a structured therapy experience that is accessible at any time and can be tailored to the individual’s specific needs and progress. Research by Marsch (2012) highlights the effectiveness of such platforms in improving treatment outcomes by providing consistent and personalized support.

Benefits of Online Counseling and Therapy

The benefits of online counseling and therapy for SUDs are manifold. They include increased accessibility for individuals living in remote areas or those with mobility limitations who might not otherwise have access to specialist treatment services. Online therapy also offers greater flexibility in scheduling, allowing clients to engage in treatment sessions outside of typical office hours and from any location, thus reducing disruption to daily commitments and enhancing privacy (Postel et al., 2008).

Moreover, online counseling can significantly reduce the stigma associated with seeking treatment. The private nature of digital interactions can encourage more individuals to seek help without fear of judgment or exposure. The anonymity provided by online platforms can also lower barriers to entry, particularly for those who may be hesitant to engage in traditional therapy settings (Schueller et al., 2013).

Challenges and Considerations

Despite its benefits, online counseling and therapy for SUDs also present several challenges. These include ensuring technological accessibility and digital literacy among users, maintaining privacy and security in digital communications, and building a therapeutic alliance in the absence of physical presence, which can be crucial for some therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, regulatory and licensing issues can complicate the provision of online therapy across state or national borders, requiring careful navigation and compliance with diverse legal frameworks (Luxton et al., 2012).

Mobile Health Applications

Mobile health applications offer a novel way to support individuals in their recovery journey. These apps can provide resources such as educational materials, self-monitoring tools, and access to peer support networks. A study by Gustafson et al. (2014) demonstrated that a smartphone app designed to support recovery significantly reduced relapse rates among individuals with alcohol use disorder.

Mobile health applications are increasingly recognized as powerful tools in the treatment and management of substance use disorders (SUDs). These applications offer a range of functionalities, including symptom tracking, treatment adherence, peer support, and educational resources, all of which are accessible directly from a user's smartphone or tablet. The integration of mobile health apps into SUD treatment plans can significantly enhance patient engagement and provide continuous support, critical elements for successful recovery.

Core Functionalities of Mobile Health Applications

Mobile apps often include features for monitoring symptoms related to SUDs, such as craving intensity, mood fluctuations, and potential triggers. This real-time data collection allows both patients and clinicians to track progress and identify patterns in behavior that may require intervention. For example, the study by Gustafson et al. (2014) demonstrated that an app designed to support recovery from alcoholism significantly reduced risky drinking days among its users by providing tools for self-monitoring and feedback.

Another crucial functionality is treatment adherence, where apps can send reminders for medication intake, therapy sessions, or meetings with healthcare providers. This feature is particularly useful in managing SUDs, where consistency in medication and therapy adherence can play a significant role in recovery outcomes. Apps may also include features to help manage side effects and drug interactions, providing users with timely information and advice to handle potential issues (Marsch & Dallery, 2012).

Many mobile health applications facilitate connections with peer support groups and forums where individuals can share their experiences, challenges, and successes in recovery. This sense of community can be incredibly beneficial, as social support is a well-known protective factor in the treatment of SUDs. Apps like Sober Grid offer geosocial networking features that connect users with a recovery community, providing support and fostering accountability (Ashford et al., 2019).

Education is a fundamental component of effective SUD treatment. Mobile apps can deliver tailored educational content that helps users understand the nature of addiction, the processes of recovery, and strategies for relapse prevention. This information is often presented in user-friendly formats, such as short videos, interactive quizzes, and infographics, making it easily digestible and engaging (Lord et al., 2015).

The benefits of using mobile health applications in treating SUDs include increased accessibility to treatment resources, enhanced ability to personalize care, and improved capacity for data collection and analysis. These apps not only make treatment more accessible but also allow for a more individualized approach by adapting interventions based on the user's behavior and feedback.

One of the most significant advantages of mobile health apps is the ability to deliver interventions in real-time. For instance, an app can provide coping strategies and motivational content when a user reports high levels of craving or stress, potentially averting relapse (Luxton et al., 2011).

Mobile health applications offer a cost-effective solution for both healthcare providers and patients. By reducing the need for frequent in-person visits and utilizing automated systems for routine monitoring and education, these apps can decrease the overall cost of SUD treatment (Torous & Firth, 2016).

While mobile health applications hold significant promise in the field of SUD treatment, there are challenges to consider, including issues related to privacy, data security, and user engagement. Ensuring the confidentiality and security of sensitive health data is paramount, as is designing user-friendly interfaces that can maintain user engagement over time. Additionally, the effectiveness of mobile interventions often depends on the integration with traditional healthcare services and the continuous updating of content to reflect current research and best practices (Bauer et al., 2017).

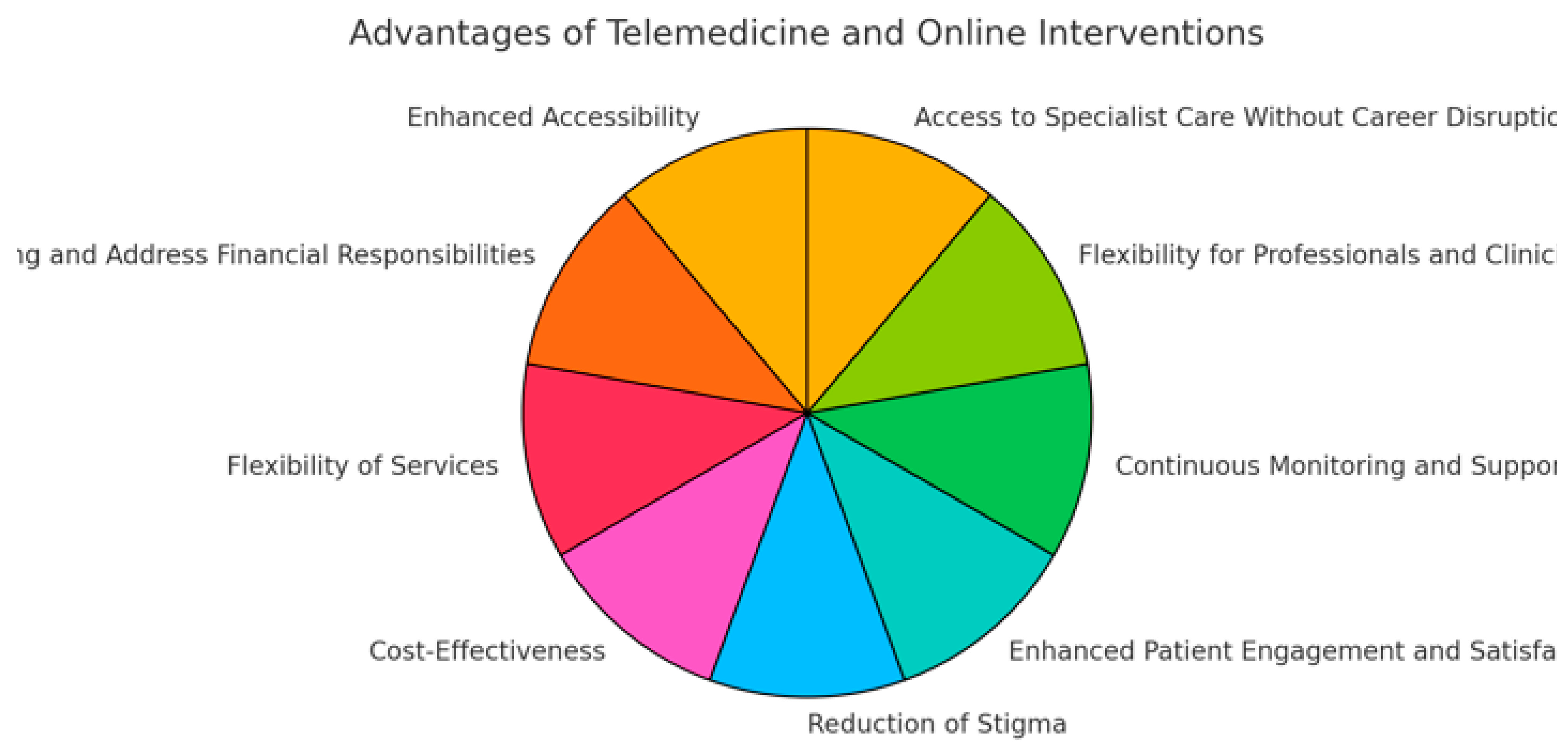

Advantages of Telemedicine and Online Interventions

Telemedicine and online interventions have revolutionized the approach to healthcare, particularly in the field of substance use disorders (SUDs). These technological advancements offer significant benefits over traditional in-person therapy by improving accessibility, reducing costs, and enhancing patient engagement, among other advantages.

One of the most significant benefits of telemedicine and online interventions is the remarkable improvement in accessibility they provide. Patients living in remote or underserved areas, where specialty care is often scarce or non-existent, can receive high-quality treatment without the need to travel. This is particularly important for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, where timely access to care can be critical for preventing relapse and maintaining recovery. Studies have shown that telemedicine can significantly increase the reach of healthcare services, ensuring that more individuals can access necessary care without geographical limitations (Yellowlees et al., 2018).

Telemedicine also mitigates other barriers to accessing care, such as financial constraints, physical disabilities, and limited transportation options. According to Hilty et al. (2013), telemedicine helps reduce the cost burden for patients by eliminating the need for long commutes to treatment centers, which is particularly beneficial for those in rural areas who may otherwise struggle to attend regular therapy sessions. This model also allows for more frequent and consistent follow-up appointments, further enhancing patient engagement and retention in treatment.

Furthermore, online interventions provide a viable solution for individuals with social anxiety, agoraphobia, or those who are uncomfortable attending in-person treatment due to stigma or privacy concerns. Shore et al. (2014) found that telemedicine significantly increased treatment adherence among populations that were reluctant to seek face-to-face help, underscoring its importance in breaking down social and psychological barriers to care. These benefits highlight how telemedicine extends beyond geographic accessibility to offer more flexible, inclusive care options that cater to the diverse needs of individuals struggling with SUDs.

As technology continues to advance, the integration of mobile health applications and remote monitoring tools into telemedicine services has further expanded accessibility. These tools allow patients to track their progress in real-time and stay connected with their healthcare providers, even in areas with limited infrastructure (Bashshur et al., 2016). This constant connectivity ensures that patients can receive timely interventions, reducing the likelihood of relapse or medical emergencies. In summary, telemedicine and online interventions not only improve physical access to care but also address the broader systemic and psychological barriers that often prevent individuals from seeking and maintaining treatment.

- 2.

Ability to Continue Working and Address Financial Responsibilities

Another significant advantage of online treatment is the opportunity for individuals to continue working while undergoing therapy. This is particularly important for those who may be facing financial difficulties, including debts incurred as a result of their substance use. Maintaining employment during treatment allows individuals to manage their financial obligations, such as mortgage payments, credit card debts, or legal fees, which can be a source of stress and a potential barrier to recovery (McLellan et al., 2007).

In traditional treatment settings, many patients are required to take time off work, which can exacerbate financial problems and lead to further stress. Online treatment, by contrast, allows individuals to receive therapy at times that fit their work schedules, whether through flexible appointment times, asynchronous communication with counselors, or self-paced online modules (Eysenbach et al., 2005). This flexibility enables patients to address both their addiction and their financial responsibilities concurrently, reducing the financial pressures that might otherwise lead to relapse.

Moreover, continuing to work while in treatment may contribute to a sense of normalcy and self-worth, both of which are critical components of recovery. For many individuals, maintaining their professional identity can bolster their motivation to stay sober and engage fully in their treatment. A study by Kay-Lambkin et al. (2011) found that individuals who were able to continue working during their recovery reported higher levels of satisfaction with their treatment and were more likely to maintain long-term sobriety compared to those who had to leave their jobs.

- 3.

Flexibility of Services

Telemedicine also offers unprecedented flexibility in scheduling and treatment modalities, a key benefit that has transformed the way patients engage with healthcare. Unlike traditional in-person visits, where patients must conform to fixed appointment times, telemedicine allows for scheduling flexibility that can accommodate the busy lives of individuals, especially those balancing work, family, or other responsibilities. Patients can often schedule appointments outside of traditional office hours and can access services from anywhere, whether they are at home, in their office, or even while traveling. This flexibility helps integrate treatment into patients' daily lives, making it less disruptive and more sustainable (Luxton et al., 2012).

In the context of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, this flexibility can play a critical role in increasing treatment adherence. Patients who would otherwise find it difficult to attend regular sessions due to geographical or time constraints can now access specialized care without compromising other commitments. A study by Mohr et al. (2012) found that the flexibility offered by telemedicine improved patient satisfaction and engagement, particularly among those in remote or underserved areas. This adaptability of services allows individuals to maintain continuity of care, which is vital for achieving and sustaining recovery.

Moreover, telemedicine's asynchronous communication options, such as email, text messaging, and app-based therapy, offer additional flexibility for patients who may not have the time or ability to participate in live video sessions. According to Andrews et al. (2018), the availability of these alternative communication methods has helped improve access to care for individuals who require more flexibility in their interactions with healthcare providers. This is particularly relevant for patients with unpredictable work schedules or those in professions where taking time off during the day is challenging.

Telemedicine also allows for quicker adjustments to treatment plans. If a patient experiences a crisis or needs to modify their treatment approach, they can easily reach out to their provider and receive timely feedback or schedule an immediate consultation. This is particularly important in addiction treatment, where timely interventions can prevent relapse or worsening of symptoms. A study by King et al. (2018) found that patients who had access to flexible telehealth services were more likely to engage in long-term care and experienced better outcomes compared to those in traditional in-person treatment settings.

In addition to benefiting patients, the flexibility of telemedicine is advantageous for healthcare providers as well. It allows clinicians to manage their time more effectively, providing services outside of typical office hours or working remotely themselves. This flexibility can reduce burnout among providers, leading to improved quality of care. Studies such as those by Gleason et al. (2020) have emphasized how telemedicine can foster a better work-life balance for healthcare professionals, which in turn enhances patient outcomes.

- 4.

Cost-Effectiveness

Telemedicine has increasingly been recognized as a cost-effective alternative to traditional healthcare delivery, offering significant savings for both healthcare providers and patients. By reducing the need for physical office space and the associated overhead costs, such as rent, utilities, and administrative support, healthcare providers can offer services at a lower rate. Additionally, patients save on travel-related expenses and time, which can be a substantial financial burden, especially for those in rural or underserved areas where specialized care is limited. This reduction in both operational and logistical costs makes telemedicine a more financially sustainable model for delivering care, particularly in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) (Bradford et al., 2016).

The cost-effectiveness of telemedicine is supported by multiple studies. For instance, a report by Humer et al. (2020) found that telemedicine programs for mental health and addiction services significantly reduced costs related to transportation, time off work, and childcare. The study also highlighted how telemedicine reduces the need for emergency room visits and inpatient services by providing timely interventions that prevent crises. These savings are particularly important in public health systems, where the financial strain of traditional treatment models can be immense.

Moreover, telemedicine offers an opportunity for more efficient use of healthcare resources. A study by Dullet et al. (2017) indicated that telemedicine programs can lead to reduced hospitalization rates and shorter lengths of stay in medical facilities by providing continuous monitoring and timely intervention. This proactive approach helps prevent the escalation of conditions, such as SUDs, that would otherwise require more intensive and expensive treatments if left unmanaged. This is especially relevant for chronic conditions like addiction, where early interventions are key to preventing relapse and reducing long-term healthcare costs.

For healthcare providers, telemedicine allows for the optimization of time and resources. With the ability to conduct more frequent, shorter, and focused virtual sessions, providers can see a higher number of patients without the need for additional physical infrastructure. According to a study by Kruse et al. (2017), telemedicine platforms help streamline administrative processes, reduce missed appointments (a common issue in traditional care settings), and increase overall patient compliance. These factors collectively contribute to cost savings and improved financial viability for both solo practitioners and larger healthcare institutions.

Telemedicine also holds potential for reducing indirect costs associated with addiction treatment. For example, individuals undergoing treatment for SUDs often face substantial indirect costs, such as lost income due to time off work for in-person appointments. A study by Molfenter et al. (2015) found that patients receiving treatment via telemedicine were able to maintain higher levels of productivity and income compared to those in traditional treatment programs. This continuity of employment is crucial for individuals with SUDs who may already be struggling with financial instability as a result of their substance use.

In addition to reducing individual costs, telemedicine can also lower broader societal costs by improving public health outcomes. By making addiction treatment more accessible and affordable, telemedicine can lead to higher treatment retention rates, lower relapse rates, and fewer legal and health complications associated with untreated SUDs. Studies such as those by Thomas et al. (2021) suggest that expanding telemedicine services for addiction treatment can yield long-term cost savings for governments and healthcare systems by reducing the societal burden of addiction-related healthcare expenses, legal issues, and lost productivity.

- 5.

Reduction of Stigma

One of the less often discussed but critically important benefits of telemedicine and online interventions is their ability to reduce the stigma associated with seeking treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs). Stigma is a major barrier to treatment, often leading individuals to avoid or delay seeking help due to fear of judgment, embarrassment, or shame. By allowing patients to receive care in the privacy of their own homes, telemedicine platforms can eliminate much of the potential discomfort that comes with visiting a clinic or therapist's office. This increased privacy can make it easier for individuals to seek help early and engage with treatment more openly, without the added stress of public scrutiny (Cunningham et al., 2010).

The reduction of stigma through telemedicine is particularly beneficial for individuals in professions where admitting to substance use could have severe career consequences, such as healthcare, law, or finance. For these individuals, the discretion afforded by online interventions is crucial in overcoming the fear of professional or social repercussions. Research by Bowen et al. (2011) highlights that individuals who received treatment remotely were more likely to continue with their therapy due to the decreased fear of encountering others during treatment sessions. The anonymity of telemedicine allows individuals to maintain control over who knows about their treatment, fostering a safer and more supportive environment for recovery.

In addition to reducing public stigma, telemedicine can also mitigate self-stigma. Self-stigma occurs when individuals internalize negative societal views about substance use, leading to feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness. Telemedicine platforms provide a more comfortable space where individuals can engage in treatment without constantly being reminded of these negative labels. According to Smith et al. (2017), the anonymity of online interventions can reduce self-stigmatizing thoughts, helping individuals to view their condition more objectively and fostering a sense of empowerment in their recovery journey.

Moreover, by normalizing digital platforms as a legitimate form of healthcare delivery, telemedicine helps shift societal perceptions of addiction treatment. As online therapy becomes more mainstream, it reduces the visibility of SUD treatment as something shameful or secretive, reframing it as an accessible and normal part of managing health. A study by Eysenbach et al. (2005) found that patients engaging in online addiction treatment felt less isolated and more integrated into general healthcare systems, thus reducing the perception that they were undergoing a stigmatized or marginalized form of treatment.

Telemedicine also allows for more flexible engagement with treatment, enabling individuals to control how and when they interact with their providers. This control can further reduce the feelings of powerlessness or shame that many individuals experience when attending in-person treatment under strict schedules. According to research by Vogel et al. (2013), the flexibility and autonomy offered by telemedicine interventions led to higher levels of patient engagement and satisfaction, as individuals felt more in charge of their treatment process.

Finally, the reduction in stigma achieved through telemedicine has broader public health implications. By making it easier and more acceptable to seek treatment, telemedicine can help increase overall treatment engagement rates, thus reducing the public health burden of untreated substance use disorders. A study by Ashford et al. (2019) suggests that increasing the availability and visibility of online treatment options could play a critical role in changing societal attitudes towards addiction and recovery, making it more socially acceptable to seek help for SUDs.

- 6.

Enhanced Patient Engagement and Satisfaction

Telemedicine and online interventions have been shown to significantly increase patient engagement and satisfaction, making them increasingly popular in the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs). The convenience of accessing care remotely, the ability to personalize treatment, and the use of interactive technologies all contribute to higher levels of patient involvement in their care. By removing the barriers of travel, scheduling conflicts, and stigma, telemedicine allows patients to engage with treatment more easily, thus improving their overall experience and outcomes. Studies have consistently reported high levels of satisfaction among patients using telehealth services, highlighting the benefits of convenience, privacy, and the perception of receiving high-quality care (Kruse et al., 2017).

The integration of interactive technologies, such as mobile apps, online self-assessments, and real-time video consultations, allows for a more dynamic and engaging treatment process. Research by Mohr et al. (2012) found that these technologies enable patients to actively track their progress, set goals, and receive instant feedback from their healthcare providers, all of which enhance their sense of ownership and motivation in the recovery process. The ability to monitor their own data in real time also gives patients a clearer understanding of their progress, making the treatment more transparent and empowering. This empowerment is crucial for fostering long-term commitment to recovery.